Introduction

Canadian citizens are divided on a wide range of questions and for a variety of reasons (Brie and Mathieu, Reference Brie and Mathieu2021). Indeed, as Conrad (Reference Conrad2022: 1) notes, Canada “is a loose-jointed construction that seems to lack the cohesion that many other nation states enjoy.” Key among these divisions is the language cleavage between anglophones and francophones. The linguistic divides between Canada’s French-speaking community, largely but not exclusively grouped in the province of Québec, and the English-speaking majority, have been an animating feature of much of Canada’s politics, with the two language groups having distinctly different views on the country itself (Laforest and Gagnon, Reference Laforest, Gagnon, Gagnon and Bickerton2020).

This article is concerned with this cleavage in Canadian politics. Specifically, we ask whether there is a way to bridge the attitudinal gap through individual bilingualism. Since the Official Languages Act was passed in 1969, federal and provincial governments have attempted to institute a variety of measures so English-speaking citizens have opportunities to learn French (McRoberts, Reference McRoberts1997). While the efficacy of these policies has been middling at best, the number of anglophones able to communicate in French is still sizable; about 9 per cent of English-speaking Canadians—or approximately 1.9 million citizens—identify as bilingual (Statistics Canada, 2023a). This is a non-negligible portion of the Canadian population, and we argue, one that has been underserved by existing research. Much of the literature on language and politics in Canada has focused on the divide in attitudes between the English and French communities on the basis of mother tongue alone. We contend that research should go beyond this. Due to the minority of anglophones who are bilingual, it seems important to examine whether the ability to communicate in French has any effects on bridging the attitudinal gap. After all, learning French, for anglophone Canadians, was very much presented as a way of reducing the linguistic divide present in the country (McRoberts, Reference McRoberts1997). In this article, we examine whether this is actually the case. Do bilingual English Canadians converge in attitudes with their francophone counterparts?

To test this question, we employ survey data probing attitudes on several key areas of difference between English- and French-speaking Canadians. In particular, we focus on whether bilingual anglophone Canadians are closer in attitudes to francophone Canadians on questions such as the protection of the French language, official bilingualism, people from Québec and secularism when compared with unilingual anglophones. Our goal is to underscore the need to move beyond simply studying Canada’s two major linguistic groups in dichotomous English–French terms, and to more appropriately consider the diversity of language use in understanding the attitudes of individual Canadians.

The “Two Solitudes”

The cultural and attitudinal differences between Canada’s two major linguistic groups have led to the anglophone majority and francophone minority earning the moniker of the “two solitudes,” a reference to Hugh MacLennan’s (Reference MacLennan1945) novel of the same name. The term refers to the fact that, despite living within the same country, the two linguistic communities are living “their separate legends” quite apart from one another (MacLennan, Reference MacLennan1945: 10). What does it mean for two linguistic communities to be living separately while under the same roof that is the Canadian federation? The literature notes that the differences can appear in the mundane. For instance, there are large differences between anglophones and francophones in media consumption for both traditional news media outlets and social media platforms (CEM, 2022). While the lack of commonality is not surprising as there are few outlets operating in both official languages, it does speak to the broader issue of the lack of shared touchstones between the two communities.

Anglophones and francophones in Canada are not exposed to the same content and can be seen as living in different realities. This is apparent within our own political science community, where there are vast differences in the content that researchers are exposed to depending on the language of instruction at their institution. Rocher (Reference Rocher2007) finds that francophone authors were seriously underrepresented in English-language books on Canadian politics. His results highlight the fact that, despite representing a quarter of all published work on Canadian politics, literature generated by French-speaking scholars only accounted for about 5 per cent of citations. This finding is underscored by studies by Daoust et al. (Reference Daoust, Gagnon and Galipeau2022) and Ouellet et al. (Reference Ouellet, Brie and Montigny2024) of course syllabi and comprehensive exams where the same lack of francophone scholars is reported at anglophone universities. As Rocher (Reference Rocher2007) aptly notes, the two solitudes in academia means that francophone and anglophone scholars present drastically different portraits of the Canadian federation. This divide between how Canada is to be seen within our own discipline reflects the broader attitudinal differences between the two language groups in society at large.

The language cleavage between French and English Canadians is central to understanding political attitudes in the country, largely due to the stark divides between the two communities. Indeed, as McRoberts (Reference McRoberts1997: 2) argues, “from the beginning, English speakers and French speakers have seen Canada in fundamentally different ways.” This is partly due to the geographic realities of Canada’s francophone population. Despite there being significant francophone communities in New Brunswick and Ontario, the vast majority of francophones reside in Québec. Many of the attitudinal differences are therefore tied to differences between Québec and other provinces. For that reason, a lot of the divide between the two solitudes is related to the extent to which the differing linguistic groups identify with Canada and how they feel Canada should be structured. Beginning with the former, Québec francophones privilege the Québécois identity over that of Canada (Brie and Mathieu, Reference Brie and Mathieu2021; McRoberts, Reference McRoberts1997). Relatedly, being a francophone is “a strong predictor of support for Québec sovereignty” (Dassonneville, Fréchet and Liang, Reference Dassonneville, Fréchet, Liang, Anderson and Turgeon2022: 287). Concurrent to these identitarian factors are divides over who should hold the power in the Canadian federation. Québec governments, and the citizens they represent, are more in favour of a decentralized federation where provincial governments hold more power than many of their fellow citizens in the majority-anglophone provinces (Brie and Mathieu, Reference Brie and Mathieu2021; Lecours, Reference Lecours2019). Quebecers are also more likely to support asymmetrical federalism than Canadians living in other provinces (Chassé et al., Reference Chassé, Jacques and Scott2025). Policy differences are also tied into these divides. Much of the modern Québec sovereigntist movement has focused on differentiating Québec from the rest of Canada through the development of a strong and robust welfare state (Béland and Lecours, Reference Béland and Lecours2005). Unsurprisingly then, francophones in Canada have been found to be more left leaning than anglophones. Another important difference is with regard to religion in society. Francophones, both in Québec and New Brunswick, are considerably more likely to favour restrictions on religious expression in the public sphere than their anglophone counterparts (Turgeon et al., Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, Gagnon and Henderson2014). Different explanations have been offered for this divergence, including the secularization process that occurred in Québec society during the Quiet Revolution (Zubrzycki, Reference Zubrzycki2016) or through different conceptualizations of liberalism (Turgeon et al., Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White and Henderson2019). Differences in attitudes between English- and French-speaking citizens have been found in other policy areas such as the environment and immigration as well (Dassonneville et al., Reference Dassonneville, Fréchet, Liang, Anderson and Turgeon2022).

Perhaps the largest divides, however, are the ones that are explicitly focused on the perception of the role of the two language groups within Canadian society. One element to this is how the two groups perceive each other. Anglophones have been found to be more positive with themselves and more negative with francophones, and vice versa for francophones though negativity toward anglophones is less severe (Brie and Mathieu, Reference Brie and Mathieu2021: 40). More notable, however, is the divide over the fragility of the French language. As Brie and Mathieu (Reference Brie and Mathieu2021) find, on this issue, Canadians are seemingly in direct opposition to each other depending on the language group; almost three-quarters of anglophones do not believe the French language is threatened in Québec, while two-thirds of francophones do. This divide between language groups only gets sharper if the analysis is focused on Québec residents only. Importantly, this divide on the survival of French within Canada is one that divides the linguistic groups even beyond the Québec–Canada cleavage. Medeiros (Reference Medeiros2017) finds that the perception of French as in decline negatively impacts the sentiments of francophones outside of Québec toward Canada. An additional key attitudinal divide is the role of Canada’s official bilingualism policy. French-speaking citizens are considerably more supportive of maintaining these policies when compared with English-speaking citizens, even if official bilingualism is supported by a majority of both language groups (Medeiros, Reference Medeiros2017; Medeiros et al., Reference Medeiros, von Schoultz and Wass2020; Turgeon et al., Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, Gagnon and Henderson2014). Additionally, while anglophones are supportive of the maintenance of the two official languages, they are less supportive of the actual policy requirements this entails (Turgeon et al., Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, Gagnon and Henderson2014). Notably, however, Turgeon et al. (Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White, Henderson and Gagnon2021) find that bilingual anglophones are significantly more positive toward both the policy and the substantive requirements of official bilingualism than unilingual anglophones.

While not a complete picture, the above discussion highlights the fact that on many issues Canadians are divided on linguistic lines. The question emerges of whether there is a way of bridging this gap. A possible avenue is through bilingual Canadians themselves.

Bilingual Canadians

Bilingual people are those who can communicate in two languages. For the purpose of this article, we are specifically interested in bilingual Canadians who can communicate in the two official languages, English and French. Importantly, as the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism noted in its report, “All bilingual persons are not bilingual in the same way” (Canada Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, 1967). The Royal Commission was referring to the extent to which bilingual persons may have varying degrees of command over the two languages they communicate in, but in Canada there is another important element to take into consideration: mother tongue. According to the 2021 census, outside of Québec, roughly 85 per cent of francophones identified as bilingual compared with only about 7 per cent of anglophones (Statistics Canada, 2021). In Québec, by contrast, more than 87 per cent of anglophones are bilingual, while the same is true for about 42 per cent of francophones. The point here is that individual bilingualism in Canada is more common among francophones than among anglophones. The reasons for this are rather simple. As Statistics Canada (2021) notes, minority language groups, which is French in the vast majority of the country, are “more likely to come into contact with the other official language community and learn its language.” This fact skews the geographic distribution of bilingual citizens. While 46 per cent of Québec residents are bilingual, the same is true for only about 10 per cent of residents in the rest of the country (Statistics Canada, 2021).

We are interested solely in the attitudes of anglophone bilinguals. This is largely because of the context of Canada’s official bilingualism policy. Adopted in 1969, official bilingualism, or the Official Languages Act, was very much focused on the idea of increasing individual bilingualism in Canada (McRoberts, Reference McRoberts1997). While the data demonstrate that this policy has not been a success, especially when coupled with the fact that increases in individual bilingualism are largely occurring in Québec while declining in the rest of the country, it is important to note the symbolic role of the policy (Statistics Canada, 2023a). This is particularly true for the anglophone community, where official bilingualism became tied to national identity. As McRoberts (Reference McRoberts1997: 107) mentions, the promotion of official bilingualism was marketed to anglophones as a way of healing the rifts between Québec and the rest of the country. Indeed, as he writes:

National unity would come by increasing the capacity of Canadians to deal with each other in both official languages. The lowering of language barriers would bring them together. This was a message that greatly appealed to many English Canadians: by becoming bilingual they could take action to unite the Canadian nation.

The points raised here are critical for understanding why anglophone Canadians who are bilingual should be closer in attitudes to their francophone co-citizens. Becoming bilingual for anglophones was perceived as a way to bridge the gap to francophones and to heal the national unity crisis. This process was mainly carried out through education. As McRoberts (Reference McRoberts1997: 108) again notes, the federal government invested heavily in promoting French immersion and other forms of French education for anglophone students across Canada. For the 2021–2022 school year, this has meant that roughly 2.5 million Canadian students were enrolled in some form of French-language program (Statistics Canada, 2023b). As mentioned above, while the actual level of bilingualism reported by anglophone Canadians is rather low, there is still a considerable number of Canadian citizens who are learning at least some French during their lives. Problematically, however, little research has been conducted on this group of citizens. If anglophones perceive learning French as a way of bridging the attitudinal gap, the question of whether this actually occurs must be asked.

Previous research into the effects of language and attitudes in Québec has found that knowledge of French does affect political attitudes. Bilodeau (Reference Bilodeau2016), for instance, finds that the more a newcomer to Québec uses the French language, the more likely they are to share political attitudes with francophones. Similar findings are reported by Chassé (Reference Chassé2021), who again finds that use of the French language correlates with closer proximity to the political attitudes of the francophone community. This article undertakes a similar approach to see whether anglophones with knowledge of French similarly see their attitudes become closer to their francophone co-citizens. A question that emerges, however, is why knowledge of a language, or more specifically the ability to communicate in a second language, has an effect on a person’s attitudes. Several main mechanisms are proposed. First, there is the Columbia approach based on personal networks (Bilodeau, Reference Bilodeau2016; Chassé, Reference Chassé2021). If an anglophone knows how to communicate in French, they are more likely to find themselves with francophones in their personal network. It is possible, as Bilodeau (Reference Bilodeau2016) theorizes for immigrants to Québec, that this presence and communication with francophones lead attitudes to converge.

Of course, this raises the question of whether bilingual anglophones will actually be in contact with francophones. McRoberts (Reference McRoberts1997: 108) is doubtful that this is occurring. As he notes, since there are so few francophones in Canada outside of Québec and parts of New Brunswick, “the opportunities to use French are small and in rapid decline.” A secondary possibility is with regard to media consumption. It is possible that a bilingual anglophone may consume news or other forms of media in French. Media consumption has been shown to have an effect in contexts where the media differs in content depending on the language utilized. Kerevel (Reference Kerevel2011) finds that, for Latinos in the United States, attitudes differ when an individual listens to Spanish or English language media on salient political questions such as immigration. As media coverage in Canada differs considerably between French and English, particularly on questions related to the status of both languages (Vessey, Reference Vessey2013), it is possible that bilingual anglophones consuming francophone media has effects on their political attitudes.

A final possibility is that anglophone bilinguals may see their attitudes converge with francophones due to their own biases caused by learning French in the first place. Many of the key attitudes that we examine in this article are particularly concerned with the status of the French language in Canada, and additionally, what should be done to both protect it from declining and promote it further, including through increased funding or requiring key positions in the civil service to be bilingual. Since bilingual anglophones have put at least some effort into learning the French language, it seems likely that they will be more positively predisposed to policies that will protect the language. Regardless, due to data limitations, we do not currently have the ability to test the question of what mechanism may play a role in effecting a bilingual individual’s political attitudes. Rather, we are interested purely in the question of whether bilingual anglophone Canadians are closer in attitudes to francophones than other unilingual Canadians.

Hypotheses

On the basis of our review of the literature above, we have generated the following two hypotheses. First is the “two solitudes” hypothesis. Largely, this follows the conventional literature we cite above that finds that language is a key attitudinal cleavage that divides Canadian citizens on questions such as the place of the French language in Canada, attitudes toward state secularism and attitudes toward Québec residents themselves.

Hypothesis 1: The attitudes of English-speaking Canadians toward the status of the French language in Canada, secularism and Quebecers will differ in a statistically significant way from those of French-speaking Canadians. Specifically, when compared with francophones, anglophones will be less likely to be concerned about the status of the French language, less likely to be in favour of measures to protect the French language, less favourable toward secularism and less positive toward Quebecers.

The second hypothesis is concerned with whether knowledge of both languages can bridge the gap in attitudes. If individual bilingualism, or at least some knowledge of French, plays a role in making anglophones more amenable to the viewpoint of their francophone co-citizens, then the attitude difference should be smaller than it is for unilingual anglophones. Our second hypothesis is, therefore, as follows:

Hypothesis 2: The attitudes of English-speaking Canadians who know French will be more similar to those of French-speaking Canadians than the attitudes of English-speaking Canadians who do not know French. Specifically, when compared with non-French speaking anglophones, bilingual anglophones will be more concerned about the status of the French language, more in favour of measures to protect the French language, more favourable toward secularism and more positive toward Quebecers.

Data and Methods

Our study is based on data from an online survey fielded in the summer of 2023 among a representative sample of 1,596 Canadian citizens using Dynata’s web panel (see Appendix A for more information). A total of 1,183 participants reported that their mother tongue is English and 287 that their mother tongue is French. The sociodemographic characteristics of the anglophone and francophone subsamples are similar, although French-speaking participants are, on average, slightly older, less likely to have attended university and less likely to come from an immigrant background than English-speaking participants (see Appendix B). It should be noted that this mirrors the demographic profile of these two groups of citizens (Statistics Canada, 2021). We measured the level of bilingualism of participants by using an item that asked them to self-assess their ability to hold a conversation in the official language of Canada that is not their mother tongue on a scale from 0 (cannot speak the language at all) to 10 (can speak the language perfectly). We consider that a person’s ability to hold a conversation is a good indicator of their general skills. It is precisely because an individual has the ability to interact with members of another language community that we expect them to have attitudes that are closer to those of that community.

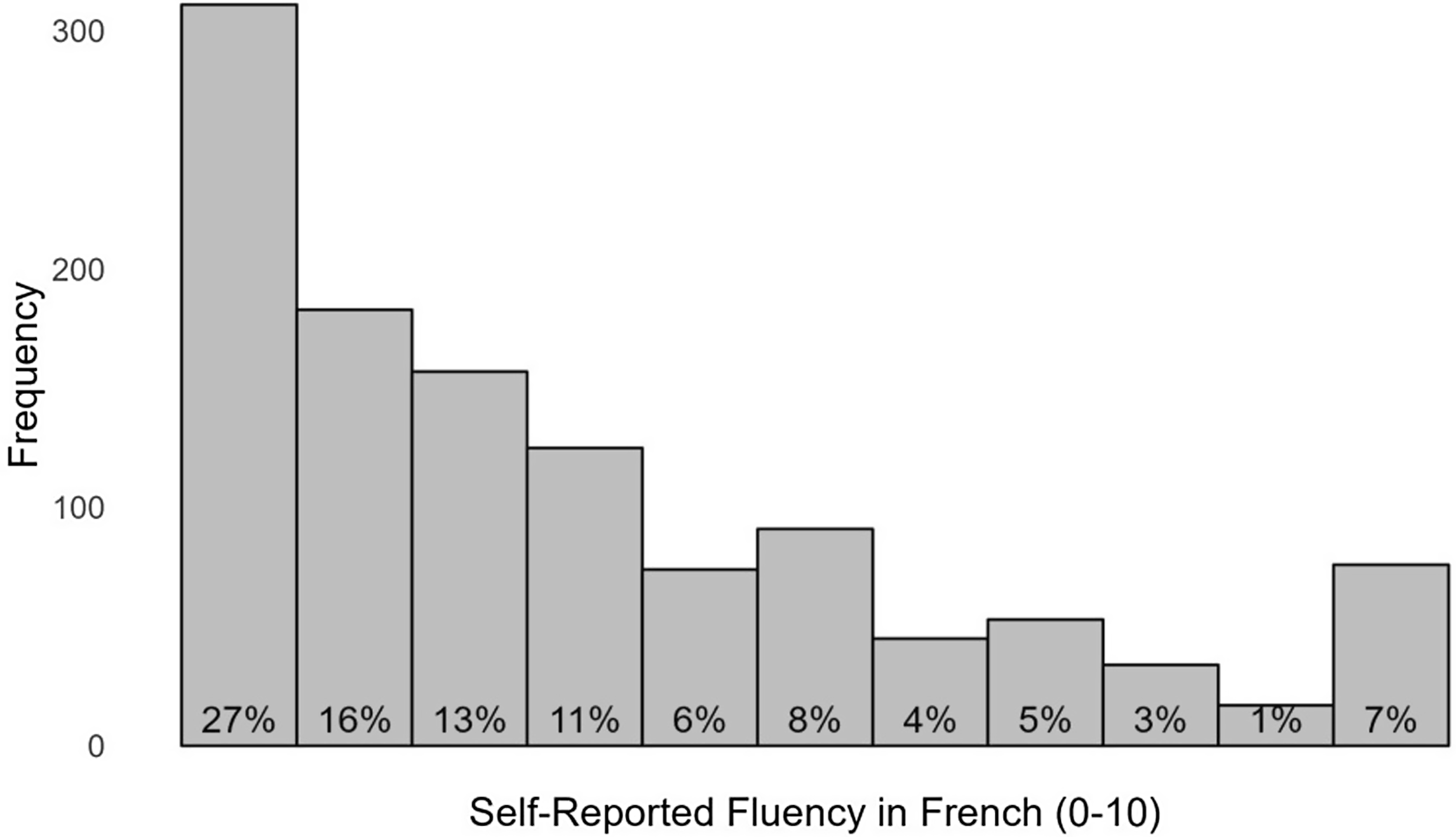

As Figure 1 shows, a plurality of anglophone respondents consider that they cannot speak French at all. This is not surprising given that, according to the 2021 census, only 9 per cent of English-speaking Canadians self-identify as bilingual. Participants who chose a value between five and ten still make up 28 per cent of the Anglophone sample. Francophone participants tend to rate their skills in the other official language much more positively: while the median answer of anglophone participants is three, the median answer of Francophone participants is eight.

Figure 1. Distribution of Bilingualism.

We examine the attitudes of English-speaking participants toward six different issues. The first four relate to the status of French in Canada and official bilingualism. We study participants’ (1) level of concern about the survival of the French language (1 = not at all worried; 5 = very worried); (2) willingness to do more to protect French outside Québec (1 = very unfavourable; 5 = very favourable); (3) willingness to provide more funding to support public services in French in Canada (1 = very unfavourable; 5 = very favourable) and (4) willingness to require public servants occupying executive positions to be bilingual (1 = very unfavourable; 5 = very favourable). As mentioned above, research indicates that francophones tend to be more concerned about the future of the French language than anglophones (Medeiros Reference Medeiros2017). Typically, francophone citizens also want to do more to ensure that their mother tongue thrives in Canada. The fifth issue on which we focus is secularism. Although various surveys show that a significant proportion of English-speaking Canadians want the government to restrict the wearing of religious symbols by public officials (Dib Reference Dib2019), francophones tend to be more in favour of such policies when compared with anglophones. For instance, the French-speaking province of Québec was the scene of a major debate on “reasonable accommodations” in the late 2000s, which ultimately led to the adoption of the Loi sur la laïcité, also known as Bill 21, in 2019 (Gagnon et al., Reference Gagnon, Xhardez, Bilodeau, Birch, Dufresne, Duval and Tremblay-Antoine2022). Finally, we look at how participants generally feel about Quebecers, the most populous group of francophones in Canada (0 = generally dislike them; 10 = generally like them).

We proceed in three steps. First, we verify whether the attitudes of anglophone participants differ from those of francophone participants. To do so, we compare the average responses of the former with the average responses of the latter. We use Welch’s t-tests to determine whether the differences between the attitudes of the two subsamples are statistically significant. As the question on the funding of French-language services outside Québec was not asked to French-speaking participants (and to English-speaking Quebecers), we are unable to compare the attitudes of anglophones and francophones on this issue. Second, we use statistical models to study the relationship between participants’ level of bilingualism and their attitudes. We first run bivariate models and then control for a set of variables that tend to be associated to political attitudes in Canada, such as age (years), gender (women respondents coded as 1), immigrant status (born outside Canada coded 1), postsecondary education (attended university coded 1), income (from 1 to 8), political interest (from 1 to 10) and province of residence. Controlling for participants’ province of residence allows us to determine whether living in a province that borders Québec (Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick and Ontario) is associated with a greater propensity to having attitudes similar to those of francophones. This is critical as the proximity of a person to these borders has been shown by Brie and Mathieu (Reference Brie and Mathieu2024) to increase the number of contacts between Québec residents and those in Ontario and New Brunswick. In the same vein, Dufresne and Ruderman (Reference Dufresne and Ruderman2018) find that the anglophones who live in regions with more francophones are likely to be more favourable toward official bilingualism than regions where there are fewer French speakers. Finally, we plot the predicted values of the dependent variables as a function of English-speaking participants’ level of proficiency in French and compare them with the average responses of French-speaking participants. We only do so when the relationship between participants’ level of bilingualism and attitudes is statistically significant in the model that includes control variables.

Since our study is based on survey data, we are only able to determine whether there is a link between the individual bilingualism of English-speaking Canadians and their attitudes toward issues on which the preferences of anglophones generally differ from those of francophones. We cannot establish the causal mechanism between the variables. For this reason, we avoid using causal language throughout this article. If, as we mentioned earlier, we have good reasons to believe that it is the knowledge of a second language that has an impact on political attitudes, and not the other way around, we cannot reject the hypothesis that some citizens have learned French because they care about the status of this language in Canada. A reverse causal relationship, however, seems implausible in the case of support for secularism since one’s opinion about religious symbols is not a reason for learning a new language. To account for respondents’ motivations for learning French, we also reproduce our models that focus on attitudes toward French and bilingualism by controlling for participants’ feelings toward Quebecers (which we use as a proxy for sympathy toward francophones) in Appendix D. These analyses also include controls for respondents’ support for the Liberal Party of Canada (LPC). If we consider that individual bilingualism is prior to voting intentions, some might still argue that adherence to the values promoted by Pierre Trudeau and the LPC more generally can lead citizens to care about issues affecting francophones, and perhaps to learn French.

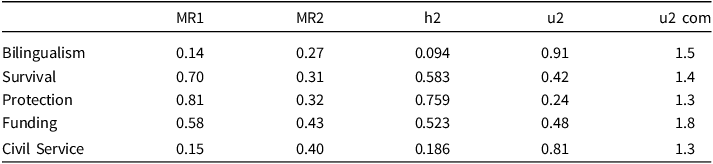

Another possibility is that the desire to become bilingual reflects a broader positive predisposition toward the French language. To ensure that respondents’ level of proficiency in French does not form an underlying factor alongside their attitudes toward our four dependent variables related to the French language—potentially introducing endogeneity in our models—we conduct a factor analysis, detailed in Appendix E. This analysis demonstrates that bilingualism does not load on the same factor as the other variables. Furthermore, when we construct an index using our variables, Cronbach’s alpha decreases significantly when bilingualism is included (from 0.68 to 0.55).

Results

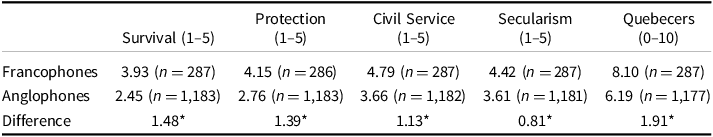

As expected, results presented in Table 1 show that the attitudes of English-speaking participants are significantly different from those of French-speaking participants (hypothesis 1). The attitudinal difference between anglophones and francophones is particularly striking with regard to the level of concern about the survival of French (1.48 points on a five-point scale) and the willingness to do more to protect this language outside Québec (1.39 points on a five-point scale). While francophones have a good opinion of Quebecers, anglophones seem to have a somewhat more negative view of this group of citizens (6.19 out of 10). It is interesting to note that francophones do not harbour such animosity toward English-speaking Canadians: their average response is 7.80 out of 10, a rating only 0.30 point lower than the average score they give to Quebecers (8.10 out of 10). This result echoes the findings of Brie and Mathieu (Reference Brie and Mathieu2021), who found an asymmetry between English speakers and French speakers in their feelings about the other language group.

Table 1. Mean Values of Attitudes Per Language Group

*p < .05 (Welch two-sample t-test)

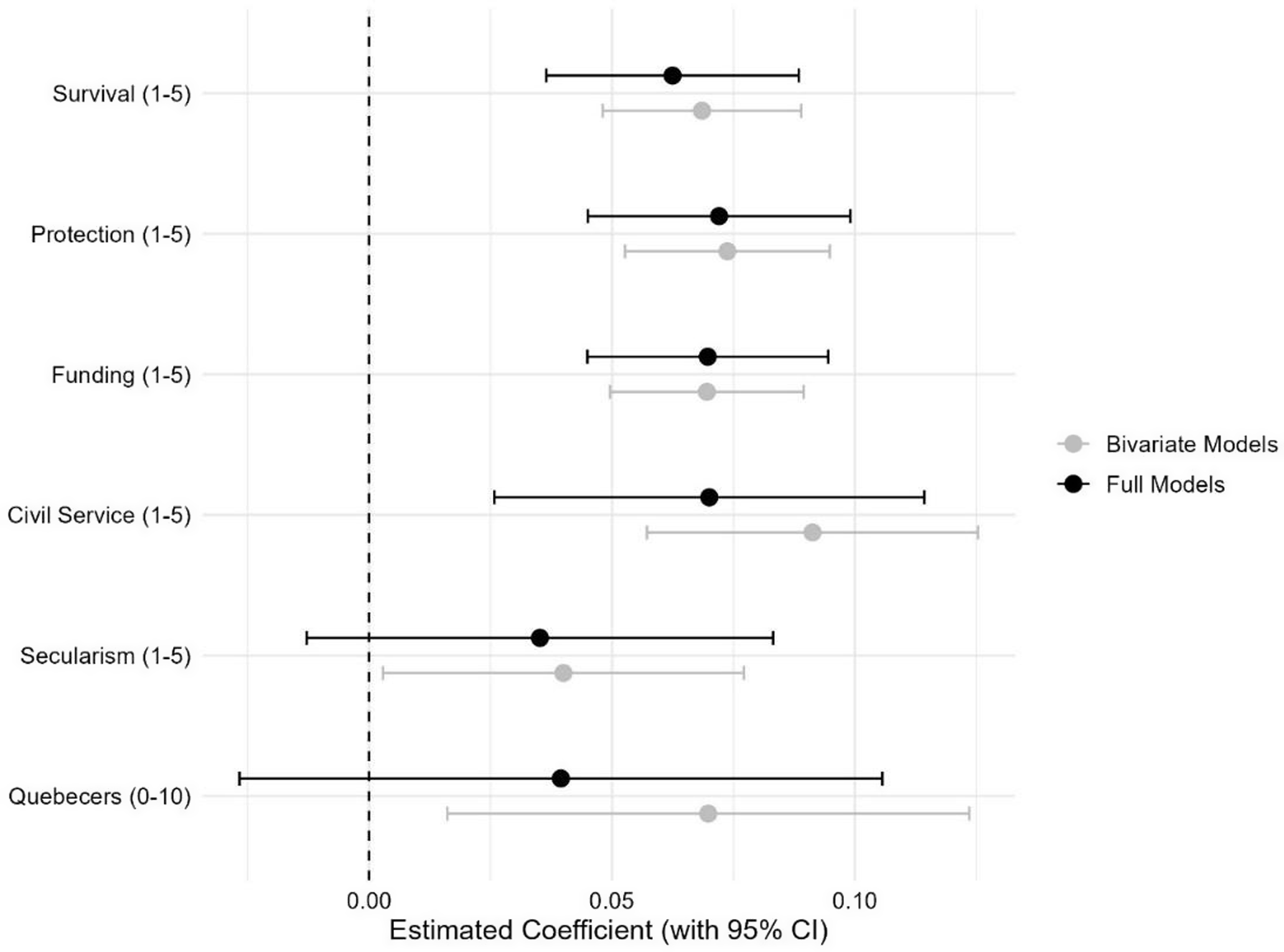

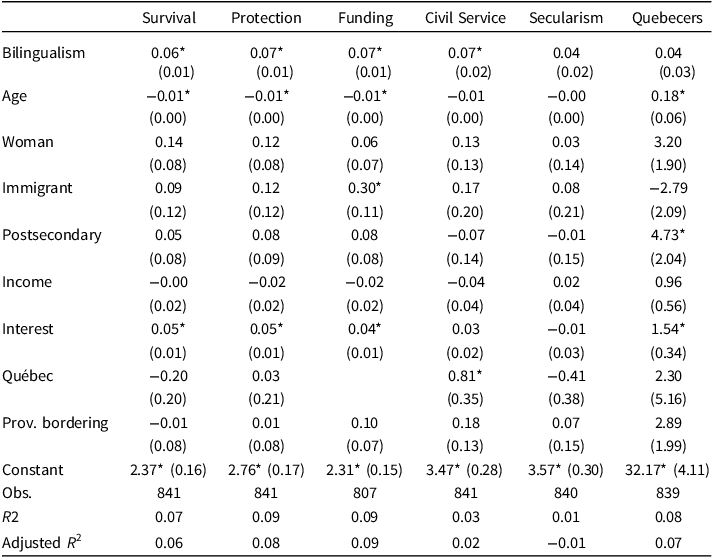

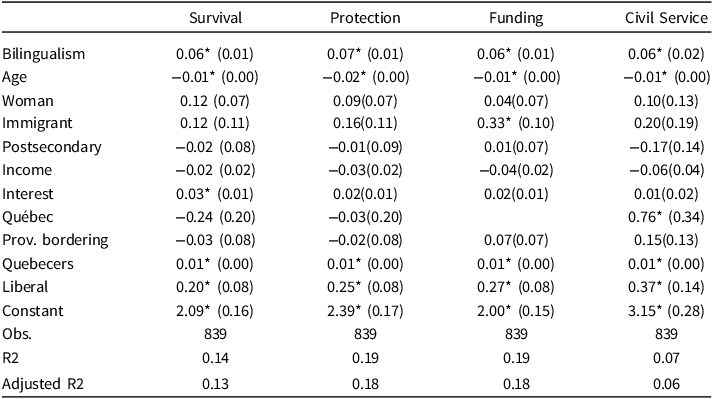

Does individual bilingualism help reduce these differences? Figure 2 shows the coefficients for the relationships between participants’ level of proficiency in French and their attitudes toward the six issues under study (full model results are presented in Appendix C). In all bivariate models, the coefficient of bilingualism is positive and statistically significant. It is particularly high in models in which the dependent variables are the willingness to require public servants occupying executive positions to be bilingual (0.09).

Figure 2. Unstandardized Coefficients for Bilingualism (OLS Models, 95% Confidence Intervals).

Note: In full models, controls include age, sex, immigration status, education, income, political interest, living in Québec and living in a province bordering Québec.

The results presented in Figure 2 nonetheless reveal that when we take into account other factors, the coefficient of individual bilingualism is no longer statistically significant in models with support for the ban on religious symbols and feelings about Quebecers as dependent variables. In both cases, the coefficient on bilingualism remains positive, but the addition of control variables reduces the size of the coefficient (which was already rather small) and increases the standard error. While the addition of control variables does not help to better predict support for secularism, several individual characteristics, such as one’s age, level of education and interest in politics, do seem to be positively related to a favourable evaluation of Quebecers (see Appendix C). It seems, then, that proficiency in French as a second language is most closely linked to attitudes toward the status of French in Canada and official bilingualism. It may be that knowledge of French is insufficient to have a substantial impact on preferences that are not directly related to language, and that it must necessarily be combined with sustained contact with francophones to lead to attitudinal convergence. It may also be a product of a particularly Canadian conundrum of national identity. While Official Bilingualism has come to be a key part of the Canadian national identity (McRoberts Reference McRoberts1997, Turgeon et al. Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White, Henderson and Gagnon2021), so has multiculturalism with its focus on the right of individuals to maintain their own cultural identities (Citrin et al. Reference Citrin, Johnston and Wright2012). The interplay of these factors might mean that bilingual anglophones are those who are most likely to have “bought” into both parts of Canada’s national identity and therefore be unwilling or unable to accept Québec’s state secularism policies as they clash with the Canadian national identity. Unfortunately, our data do not allow us to know what drives these particular findings.

The results presented in Appendix C suggest that living in a province bordering Québec is not related to the attitudes under study. It is interesting to note, however, that English-speaking Quebecers are more inclined to be in favour of public servants in executive positions being bilingual. This probably reflects their expectation that French-speaking public servants should also be proficient in English. The additional analyses we carry out in Appendix E to get a better idea of the direction of causality paint a similar picture than our main models. Even when we control for respondents’ feeling about Quebecers and support for the LPC, the coefficient of individual bilingualism remains positive and statistically significant.

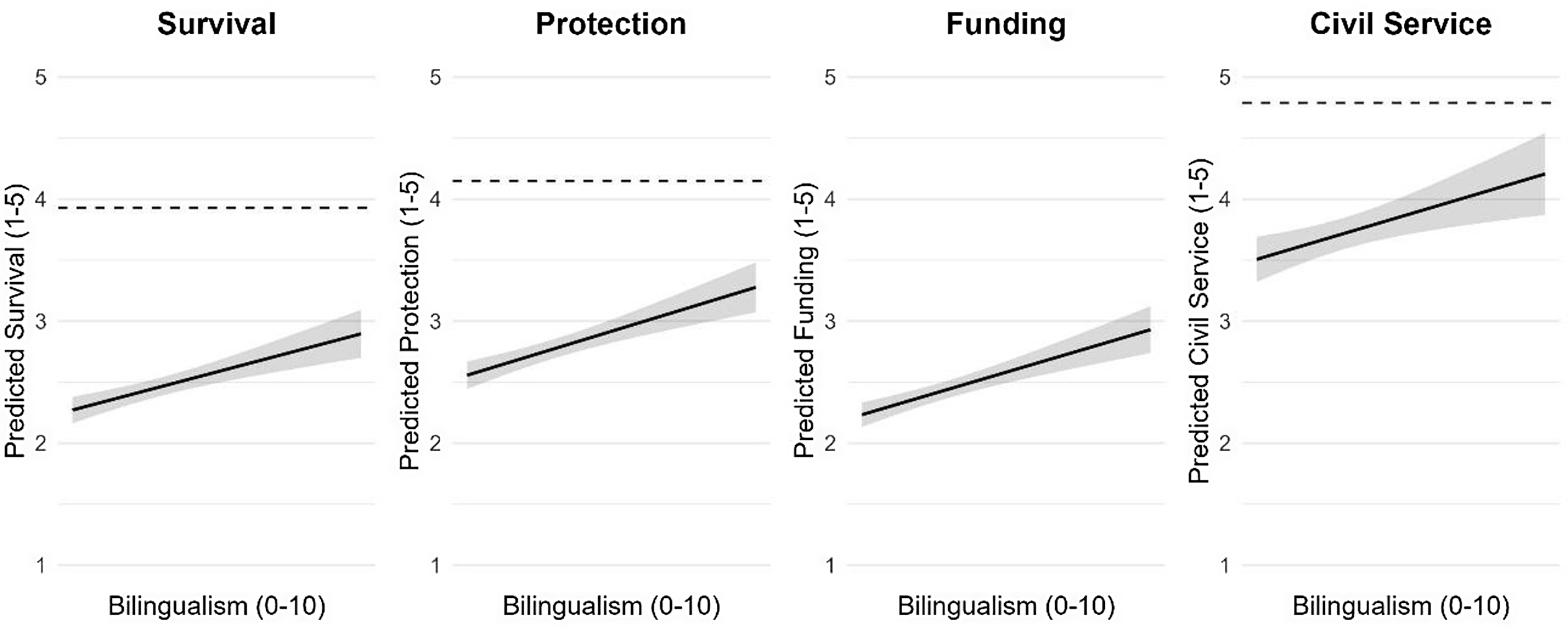

Figure 3 shows the relationship between anglophone respondents’ level of proficiency in French and their attitudes toward the status of French in Canada and official bilingualism. The dotted line represents the average response of the francophone subsample. As a reminder, we cannot compare the attitudes of anglophones and francophones with regard to the funding of French-language services outside Québec, as this question was not asked to French-speaking participants (and English-speaking Quebecers). Interestingly, the attitudes of anglophones who report being perfectly bilingual are more similar to those of francophones than those of anglophones who report not being able to hold a conversation in French (hypothesis 2). While the attitudinal difference between bilinguals and nonbilinguals is quite marked, it should nevertheless be emphasized that the predicted values of the attitudes of Anglophone participants who speak French perfectly remain lower than the mean values of Francophone participants. In fact, they correspond to “neutral” opinions on two out of four issues. On average, anglophones who are fully bilingual are neither confident nor worried about the future of the French language in Canada, and neither disagree nor agree with the idea that more funding should be provided to support public services in French in Canada. Yet they are in favour of further protecting French and requiring public servants occupying executive positions to be bilingual. While these results suggest that bilingualism does not completely bridge the attitudinal gap between anglophones and francophones in Canada, they highlight the relevance of considering the different languages that people speak—and not just their mother tongue—to understand their political attitudes.

Figure 3. Predicted Values (Full OLS Models, 95% Confidence Intervals).

Conclusion

This article is focused on the question of whether individual bilingualism can be one way of bridging the attitudinal gap between francophone and anglophone Canadians. Our findings clearly demonstrate that political attitudes are shaped by knowledge of a second language; individual bilingualism reduces the attitudinal divide on certain key issues related to the status of the French language in Canada. This result is, in and of itself, important, demonstrating the role that second languages can play in informing political attitudes. A reduction in the attitudinal divide does not mean that the two solitudes simply disappear. As our results underscore, the language cleavage is perhaps a bridge too far; even perfect bilingualism among anglophones does not completely erase the gap to francophones. This further underscores the extent to which mother tongue in Canada remains a strong predictor of political attitudes, even among those who subsequently learn the other official language.

Additionally, our findings serve to indicate just how little we still know about the role of languages in the Canadian context. Despite the rather developed literature on the subject of the divide itself, considerably less has been written on the subject of bilingual Canadians. This article has provided a first attempt at understanding how knowledge of the French language impacts the attitudes of anglophone Canadians. Although our findings are correlational, we believe that this article provides a necessary first look at how individual bilingualism can impact a person’s attitudes. Future studies should seek to examine whether this relationship is causal by examining the motivations behind why certain anglophones seek to become bilingual. Further, our research only examines anglophone bilinguals, leaving francophone bilinguals, and indeed allophones, largely unexplored.

While our results again point to the continued existence of this gap, even when individual bilingualism is taken into account, we believe that they also serve as proof that understanding the effect of language on political attitudes needs to go beyond the simple focus on mother tongue alone. Future research on both Canadian and other contexts would be well served by taking this into account.

Data availability statement

Data and replication files are available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to Colin Scott (Concordia University) for allowing them to add questions to the survey he conducted during the summer of 2023. This article would not have been possible without his generosity. They would also like to thank the editor, the two anonymous reviewers, and the participants of the seminar organized by the Canada Research Chair in Electoral Democracy, as well as attendees of the annual conferences of the Midwest Political Science Association (MPSA) and the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA), for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this article. The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Centre for the Study of Democratic Citizenship (CSDC) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix A. Survey Information (AAPOR Transparency Initiative)

Data Collection Strategy:

The data were collected using a web-based survey.

Sponsor:

The survey was funded by the Centre for the Study of Democratic Citizenship (CSDC). The principal investigator is Colin Scott (Concordia University).

Measurement Tools:

The survey questionnaire included five separate blocks and required approximately 15 minutes to complete. Participants were invited to answer questions about their sociodemographic characteristics (Block 1 and Block 5), their political attitudes (Block 2 and Block 3) and their opinion on diversity issues (Block 4). See the wording of all the questions used in this study below.

Population Under Study:

Canadian citizens over the age of 18.

Method Used to Generate and Recruit the Sample:

Study participants were recruited from Dynata’s proprietary panel. This firm uses opt-in panels and not online advertisements to recruit participants. Quotas by province of residence, age group (15–24, 25–44, 45–64, 65+), sex, education level and mother tongue (in Québec only) were used to match the figures of the 2021 Canadian census of the population.

Method and Mode of Data Collection:

Self-administered web survey in English or French.

Dates of Data Collection:

August 16 through September 2, 2023.

Sample Size:

1,596 Canadian citizens (18 and over).

How the Data Were Weighted:

The data were not weighted.

How the Data Were Processed and Procedures to Ensure Data Quality:

Dynata has removed observations that completed the study in under 4.7 minutes, as part of their quality assurance protocol.

Limitations of the Design and Data Collection:

All surveys inherently have errors that cannot be measured. These errors can occur due to response rates being below 100%, quotas not adequately addressing potential discrepancies between the sample and the population under study or participants misunderstanding or being unable to answer all survey questions. In this particular survey, there was an error where participants were allowed to skip the question on their province of residence without a reminder prompt, leading to a large number of non-responses.

Wording of the Questions:

AGE What is your year of birth?

-

Dropdown menu (1900–2025, Prefer not to respond: -98)

CITIZEN Are you a Canadian citizen, Permanent Resident, or something else?

-

Canadian citizen (1)

-

Permanent resident (2)

-

Other (3)

GENDER What is your gender?

-

Male (1)

-

Female (2)

-

I identify differently (3)

-

I prefer not to respond (−98)

PROV What is your province or territory of residence?

-

Alberta (1)

-

British Columbia (2)

-

Manitoba (3)

-

New Brunswick (4)

-

Newfoundland & Labrador (5)

-

Northwest Territories (6)

-

Nova Scotia (7)

-

Nunavut (8)

-

Ontario (9)

-

Prince Edward Island (10)

-

Quebec (11)

-

Saskatchewan (12)

-

Yukon (13)

EDUC What is the highest level of education you have completed?

-

No schooling (1)

-

Some elementary school (2)

-

Completed elementary school (3)

-

Some secondary/high school (4)

-

Completed secondary/high school (5)

-

Some technical, community college, CEGEP, College Classique (6)

-

Completed technical, community college, CEGEP, College Classique (7)

-

Some university (8)

-

Bachelor’s degree (9)

-

Master’s degree (10)

-

Professional degree or doctorate (11)

-

Don’t know/Prefer not to answer (−98)

LANG What is the language that you first learned at home in childhood and still understand?

-

English (1)

-

French (2)

-

Other (specify) (3)

LANG_SKILL_FR How well can you hold a conversation in Canada’s two official languages, English and French? Use the scale below to indicate your ability to speak and converse in English and French, where 0 means you cannot speak the language at all, and 10 means you can speak the language perfectly. French.

-

0–10scale

FT_QUEBECOIS How do you generally feel about the following groups of people? Set the slider to a number from 0 to 100, where 0 means you generally tend to dislike members of the group and 100 means you generally tend to like members of that group. Quebeckers

-

0–100 scale

SPEND_FR_ROC Please indicate whether you would like to see more or less government spending in each area. Keep in mind that “more” or “much more” spending might require a tax increase. Funding to support French-language services in Canada,

-

Strongly disagree (1)

-

Disagree (2)

-

Neither agree nor disagree (3)

-

Agree (4)

-

Strongly agree (5)

POLICY_BILINGUAL Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each of the following policy issues: Requiring public servants occupying executive positions to be bilingual in both of Canada’s official languages, English and French.

-

Strongly disagree (1)

-

Disagree (2)

-

Neither agree nor disagree (3)

-

Agree (4)

-

Strongly agree (5)

POLICY_RELSYM Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each of the following policy issues: Banning public servants from wearing religious symbols while on the job.

-

Strongly disagree (1)

-

Disagree (2)

-

Neither agree nor disagree (3)

-

Agree (4)

-

Strongly agree (5)

POL_INT How interested are you in politics? Use the scale below to indicate your interest in politics where 0 means “no interest at all” and 10 means “a great deal of interest.”

-

0–10 scale

INCOME Which of the following best describes your annual household income?

-

No income (1)

-

Under $30,000 (2)

-

Between $30,000 and $59,999 (3)

-

Between $60,000 and $89,000 (4)

-

Between $90,000 and $109,000 (5)

-

Between $110,000 and $149,999 (6)

-

Between $150,000 and $199,999 (7)

-

$200,000 or more (8)

-

Prefer not to answer (−98)

VOTE If a Canadian federal election were held today, which one of the following parties would you vote for?

-

The Liberal Party of Canada (1)

-

The Conservative Party of Canada (2)

-

The New Democratic Party of Canada (3)

-

The Bloc Québécois If PROV = Quebec (4)

-

The Green Party of Canada (5)

-

The Peoples’ Party of Canada (6)

-

Another Party (7)

-

None/Undecided/Too early to tell (8)

VOTE_LEAN Perhaps you have not yet made up your mind. Is there, nonetheless, a political party you might be more inclined to support? If VOTE = None/Undecided/Too early to tell

-

The Liberal Party of Canada (1)

-

The Conservative Party of Canada (2)

-

The New Democratic Party of Canada (3)

-

The Bloc Québécois If PROV = Quebec (4)

-

The Green Party of Canada (5)

-

The Peoples’ Party of Canada (6)

-

Another Party (7)

-

None/Undecided/Too early to tell (8)

BORN Were you born in Canada?

-

Yes (1)

-

No (0)

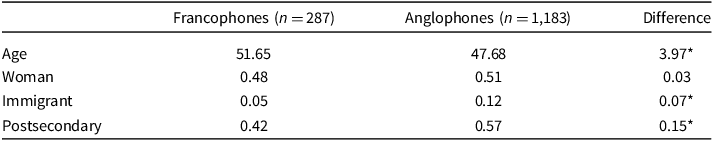

Appendix B. Sample Descriptive Statistics

Table B1. Mean Values per Language Group

p < .05 (Welch two-sample t-test)

Appendix C. Model Results

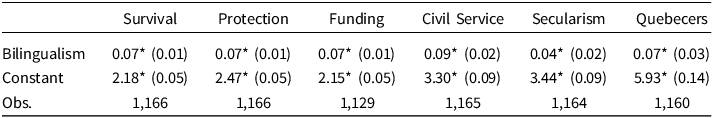

Table C1. Bivariate Models (OLS Models, Unstandardized Coefficients, Standard Errors in Parentheses)

p < .05

Table C2. Full Models (OLS Models, Unstandardized Coefficients, Standard Errors in Parentheses)

p < 0.05

Appendix D. Supplementary Analyses

Table D1. Alternative Models (OLS Models, Unstandardized Coefficients, Standard Errors in Parentheses)

p < 0.05

Appendix E. Factor Analysis

Table E1. Standardized loadings