Introduction

Becoming a parent dramatically affects the lives of men and women – introducing salient new social roles and identities, altered social networks, tighter finances and greater stress, as well as the joy of having a child (Bianchi et al. Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milkie2006; Gallager & Gerstel Reference Gallagher and Gerstel2001; Munch et al. Reference Munch, McPherson and Smith‐Lovin1997; Nomaguchi & Milkie Reference Nomaguchi and Milkie2003; Senior Reference Senior2014). Even though modern family life has evolved in many important respects, parenthood continues to shape the lives of men and women in very different ways, typically reinforcing traditional gender roles and behaviours (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter2014; Bianchi et al. Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milkie2006; Katz‐Wise et al. Reference Katz‐Wise, Priess and Hyde2010). Scholars in a range of disciplines have explored the effects of parenthood and find that becoming a parent has important impacts on broad life orientations such as happiness and psychological well‐being, and that these effects significantly vary by gender (Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Glass and Simon2014; Huijts et al. Reference Huijts, Kraaykamp and Subramanian2011; McLanahan & Adams Reference McLanahan and Adams1987). Given that parenthood changes the lives of men and women in profoundly different ways it seems likely that raising a child would bring about changes in the way women and men think about politics and policy issues. Yet, until recently, parenthood, and the distinctions of motherhood and fatherhood, have been overlooked in most studies of public opinion.

Recent studies, employing data from the United States, demonstrate that parenthood shapes attitudes on a range of policy issues and that these parenthood effects are mediated by gender (Elder & Greene forthcoming, Reference Elder and Greene2012, Reference Elder and Greene2006; Howell & Day Reference Howell and Day2000). The most consistent finding is that mothers are more supportive of government social welfare programmes than non‐mothers. In contrast, parenthood effects are less pronounced and less consistent for men; but in many cases fatherhood is associated with more conservative views. A key implication is that parenthood contributes to and reinforces the gender gap in policy preference and vote choice.

To expand our understanding of parenthood as an adult political socialisation experience, we need to move beyond the single case of the United States. This research does just that, extending and testing the findings from the American political context into the contemporary democracies of Europe. Scholars of European politics have begun looking at the ways personal experiences, such as marriage, divorce and gendered divisions of housework, shape political attitudes and vote choice (e.g., Edlund et al. Reference Edlund, Haider and Pande2005; Finseraas et al. Reference Finseraas, Jakobsson and Kotsadam2012; Iversen & Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006), yet there has not been comparable research on the effects of parenthood – arguably the most powerful personal life experience.

This research explores how parenthood is related to attitudes about gender roles as well as the appropriate role of government in providing social welfare programmes, across Europe, with explicit attention to how the effects of parenthood and gender vary across different parental policy contexts. We employ 2008 European Social Survey (ESS) data to address the following questions: Do parents in European democracies have distinctive policy preferences in comparison to their non‐parent counterparts? And, if so, are the effects of parenthood significantly different for mothers and fathers? Additionally, by exploring the effects of parenthood across many countries, rather than just one country, we are able to explore the extent to which country‐level factors such as a nation's family leave and child benefit policies condition parenthood effects, as would be predicted by the policy feedback literature (Kumlin & Stadelmann‐Steffen Reference Kumlin and Stadelmann‐Steffen2014; Pierson Reference Pierson1993; Soss & Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007; Svallfors Reference Svallfors2010). This research provides a more universal and contextual understanding of how deeply personal experiences, such as being a parent, are related to political attitudes across the life cycle. Additionally, by looking at how parenthood differentially influences the attitudes of men and women, our findings provide important insights into the possible causes and pervasiveness of the gender gap across contemporary democracies.

Parenthood and the gender gap in Europe

While there are a few studies that touch briefly on the way parenthood shapes political attitudes in European nations, they are part of broader efforts to explain the emergence of the modern gender gap in Europe, with women endorsing more leftist policies and parties than men (Corbetta & Cavazza Reference Corbetta and Cavazza2008; Edlund & Pande Reference Edlund and Pande2002; Giger Reference Giger2009; Inglehart & Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2000; Studlar et al. Reference Studlar, McAllister and Hayes1998). Similar to the United States, the most pronounced gender gap in public opinion in European countries appears on role of government issues, with women supporting a more robust social welfare state than men (Howell & Day Reference Howell and Day2000; Iversen & Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006; Kaufmann & Petrocik Reference Kaufmann and Petrocik1999). Seeking to understand the modern gender gap, scholars of European politics have looked primarily at three factors: women's increasing labour force participation, marital status and divorce, and the division of labour within the home – and some of these studies allude to parenthood or include parenthood as a control variable in their analyses.

European democracies, much like the United States, have all seen a dramatic increase in women moving into the paid labour force (EU Commission 2013), which has been a significant force behind the modern gender gap, especially because women continue to engage in a greater share of household work than men despite their paid employment (Corbetta & Cavazza Reference Corbetta and Cavazza2008; Giger Reference Giger2009). Iversen and Rosenbluth (Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006: 13) argue that working women see the government and government programmes that socialise women's work as an ally in their efforts to take on the dual responsibilities of working outside and inside the home, whereas men ‘may prefer to spare the public purse and hence their tax bill if their wives are default childcare givers’. Similarly, Cobetta and Cavazza (2006) find that women's movement into the labour force helps explain the leftward trend in women's voting in Italy from 1968 to 2006. They argue that being in the workforce leads women to demand greater social services, such as day care, and in turn to vote more for left parties that are more responsive to such demands. It is important to note, however, that while the argument advanced in these studies is premised on the idea that working women need child care, the empirical analyses do not include any actual measurements of parenthood.

A number of studies argue that rising levels of divorce and births to unmarried parents are another driver of the gender gap in Europe, as well as variations in the size of the gender gap across European democracies (e.g., Edlund & Pande Reference Edlund and Pande2002; Edlund et al. Reference Edlund, Haider and Pande2005; Iversen & Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006). These studies argue that non‐marriage decreases the amount of resources women receive from men, which in turn causes women to want more generous redistributive policies and support leftist parties. In other words, in a world in which marriage is less common, ‘state‐led redistribution benefits unmarried women more than men’ (Edlund et al. Reference Edlund, Haider and Pande2005: 97). In one of their models using 1992 Eurobarometer data, Edlund et al. (Reference Edlund, Haider and Pande2005) include parenthood as a control variable and find it is a significant predictor of greater support for government provision of a wide range of social welfare programmes. In contrast, a study focused exclusively on explaining the gender gap in Norway found no evidence that individual‐level perceptions about the likelihood of divorce drive women's more left‐leaning attitudes on social welfare issues or vote choice (Finseraas et al. Reference Finseraas, Jakobsson and Kotsadam2012). Interestingly though, one of their analyses included parenting young children as a control variable and finds that being a parent is a predictor of a gender gap on the issue of government provided child care, but not government provided elder care (Finseraas et al. Reference Finseraas, Jakobsson and Kotsadam2012: 232).

The contrasting findings across different countries may be due to the different levels of support provided to parents, which, according to policy feedback theory, may in turn shape attitudes on social welfare issues (Kumlin & Stadelmann‐Steffen Reference Kumlin and Stadelmann‐Steffen2014; Pierson Reference Pierson1993; Soss & Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007; Svallfors Reference Svallfors2010). The types of policies enacted by European countries to support parents include leave (parental and maternity), maternal and infant health as well as economic support. In general, these policies discourage exit from the labour force among women (Pronzato Reference Pronzato2009); however, there are reasons to differentiate between the types of policies as some promote women's increased participation in the labour force (parental leave) whereas others, such as direct payments to parents (child benefits), reduce women's employment (Apps & Rees Reference Apps and Rees2004). In other words, there is an important distinction between parental policies that support the traditional male breadwinner model of families and those that either seek to promote gender equality in the ‘breadwinner’ role (i.e., promote equality in labour force participation) or even transform gender roles by encouraging fathers to take on the primary caregiver role (Ciccia & Verloo Reference Ciccia and Verloo2012). Direct payments, such as a universal child benefit, would be associated with the traditional male breadwinner model as they might replace a mother's contribution to the family income and discourage her labour force participation. In contrast, generous parental leave policies would allow greater participation of women in the labour force and signal less traditional roles for women. Differences in the uptake of these policies are likely to condition the effect of parenthood on political attitudes in the same way they are found to condition the relationship between women's earnings and support for traditional women's roles (Budig et al. Reference Budig, Misra and Boeckmann2012).

Our current study builds on the European gender gap studies, discussed previously, in several important ways. First, using more recent cross‐national data, we look explicitly at the relationship between parenthood and political attitudes separately for women and men. In previous studies, parenthood, undifferentiated by gender, was used as a control variable (Edlund et al. Reference Edlund, Haider and Pande2005; Finseraas et al. Reference Finseraas, Jakobsson and Kotsadam2012) or parenthood was simply assumed to be a factor behind the differing policy preferences of women and men (e.g., Corbetta & Cavazza Reference Corbetta and Cavazza2008; Iversen & Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006). Given the profoundly different ways parenthood affects women and men, the lack of attention to the gendered nature of parenthood is a problematic omission. In this study, our central focus is on exploring the way parenthood is associated with traditional gender role attitudes and social welfare attitudes, with explicit attention on the way that parenthood affects women and men differently. Second, taking advantage of the cross‐national data, this study adds to our existing understanding of parenthood as a political socialisation experience by exploring the interaction between country‐level parental support policies, parental attitudes and the gender gap.

The gendered nature and effects of parenthood: Hypotheses

Explanations for why and how parenthood shifts political attitudes draw on two different lines of reasoning. First, parenthood alters gender role perceptions, and second, parenthood changes one's relationship to the welfare state. First, research from a broad array of fields illustrates that contemporary parenthood is a highly gendered experience. Despite significant changes in the roles of mothers and fathers in contemporary family life, traditional roles and expectations for men and women parents remain alive and well in modern societies (Bianchi et al. Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milkie2006) and actually grow stronger after the birth of a child (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter2014; Katz‐Wise et al. Reference Katz‐Wise, Priess and Hyde2010; Miller Reference Miller2011a, Reference Miller2010). Over the last several decades, in both the United States and Europe, women have moved into the workforce in large numbers; yet society, especially mothers themselves, continues to believe that mothers should be the primary caregivers and nurturers for their children. Contemporary mothers are now balancing as much or more quality time with their children than mothers of past generations, while also working more hours outside the home, and they do so by prioritising their roles and identities as mothers above all else (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter2014; Katz‐Wise et al. Reference Katz‐Wise, Priess and Hyde2010; St. George Reference George2007). In contrast, men respond to fatherhood by engaging in less household work and working more hours outside the home (Bianchi et al. Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milkie2006; Burns et al. Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001: 311; Lundberg & Rose Reference Lundberg and Rose2002, Reference Lundberg and Rose2000).

Studies conducted in both Australia and the United States find that the more traditional roles assumed by men and women after becoming parents leads them to embrace more traditional gender role values (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter2014; Katz‐Wise et al. Reference Katz‐Wise, Priess and Hyde2010). In the Australian case, for example, the transition to parenthood was associated ‘with both men and women becoming more likely to support mothering as women's most important role in life’ (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter2014: 989). While we should be concerned about selection effects when studying parenthood as an agent of political socialisation, it is important to note that both the studies just discussed were based on panel data tracking individuals before and after the transition to parenthood and thus are able to control for selection effects. Based on this research it seems plausible that parenthood, and perhaps motherhood in particular, may alter political attitudes in European countries by reinforcing traditional gender roles, leading to our initial hypothesis:

H1: Parents are more likely to hold traditional gender role values than non‐parents.

The intense juggling act of contemporary motherhood appears to be an experience with considerable potential to politicise mothers and, in particular, to foster greater appreciation for an active government in providing social welfare programmes or the ‘partial socialization of family work’ (Iversen & Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006: 12). In the American context, Elder and Greene (forthcoming, Reference Elder and Greene2012, Reference Elder and Greene2006) have found women who are mothers are significantly more left‐leaning than women without children in their households, not only on policies directly related to children, but also on broader social welfare issues.Footnote 1 These results are consistent with the ‘maternal thinking’ theories offered by some feminist scholars that the nurturing work engaged in by mothers fosters a political world view characterised by more compassion for others and more support for government support for those in need (Elshtain Reference Elshtain1983, Reference Elshtain1985; Ruddick Reference Ruddick1989; Sapiro Reference Sapiro1983). This line of reasoning suggests our second hypothesis:

H2: Mothers are more supportive than men as well as women without children of government provision of social welfare policies/benefits.

The experience of fatherhood in Europe is in flux. Even more so than American dads, fathers in European nations are spending more time with their children and engaging in more of the day‐to‐day caregiving and nurturing activities previously seen as the work of mothers, in part because of more generous fatherhood leave policies (Bennhold Reference Bennhold2010; Miller Reference Miller2011a, Reference Miller2010; Wall & Arnold Reference Wall and Arnold2007). Yet the cultural expectations that ‘good fathers’ are first and foremost supposed to be economic providers for their family persist (Miller Reference Miller2011b, Reference Miller2010; Townsend Reference Townsend2002). The government in Sweden, for example, has struggled to persuade men to take advantage of paternity leave policies (Bennhold Reference Bennhold2010). Similarly a sociological study in England showed that while men expressed intentions to be more involved fathers before having children, they reverted to more traditional roles once they actually became parents (Miller Reference Miller2011a, Reference Miller2010). As mentioned above, men actually engage in less household work and work more hours outside the home once they become parents (Bianchi et al. Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milkie2006; Burns et al. Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001: 311; Lundberg & Rose Reference Lundberg and Rose2002, Reference Lundberg and Rose2000). Similarly, studies have shown that parenthood is a salient identity for men, but not as much as it is for women, and that for men, their identity as workers is stronger than their identity as parents (Katz‐Wise et al. Reference Katz‐Wise, Priess and Hyde2010; Simon Reference Simon1992). In the American context, Elder and Greene (Reference Elder and Greene2012, Reference Elder and Greene2006) have found that the social welfare attitudes of men are less consistently influenced by parenthood than women, but when there are fatherhood effects they are in a conservative direction. Such findings are consistent with the idea articulated by Iversen and Rosenbluth (Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006) that while generous social welfare programmes may help their working wives, men perceive a more robust social welfare state as a threat to their pay checks and therefore their ability to be good providers for their families. This leads to our third hypothesis:

H3: Fathers are more conservative than mothers as well as women and men without children when it comes to government provision of social welfare policy.

Because the structure of the welfare state in regard to parental support differs considerably across Europe, we also expect to find that the relationship between parenthood and policy attitudes are conditioned on the level of benefits provided by a country as implied by the policy feedback literature (Kumlin & Stadelmann‐Steffen Reference Kumlin and Stadelmann‐Steffen2014; Pierson Reference Pierson1993; Soss & Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007; Svallfors Reference Svallfors2010). In some countries where there is a great deal of support for parents, the event of having a child may not increase support for greater government intervention in provision of services for mothers in the same way that parenthood would shift opinions where the state was failing to provide adequate support. In other words, we expect that mothers will be the most politicised in nations with minimal family leave policies, since they will face the largest struggles balancing work and family responsibilities in those nations and be particularly primed to want the government to do more. Meanwhile, the more generous social supports offered by some European governments will take some of the pressure off contemporary parents, especially mothers, and would make parenthood a less politicising and polarising experience. Finally, where the traditional model of the family with the father as the breadwinner is prioritised, as indicated by the presence of a direct child benefit payment, mothers are more likely to demand greater support from the state. This leads to a fourth and a fifth hypothesis on how the policy context shapes the impact of parenthood on political attitudes:

H4: The differences between parents and non‐parents, as well as the difference between mothers and fathers, will be minimised where states adopt policies that support parents’ continued involvement in the labour force (e.g., generous parental leave policies).

H5: The parenthood gap, differences between mothers and fathers, will increase where the traditional ‘male breadwinner’ family model is supported (i.e., universal child benefits).

Our hypotheses examine the relationship of parenthood with gender role values and support for government provision of services. Our argument regarding government provision of services is that mothers will be more supportive as they are more likely to benefit from these services. However, the adoption of more traditional values may also lead parents in general to become more conservative overall. We take this possibility into account when testing the above hypotheses by controlling for traditional values in the model estimating responses to the government responsibility items.

Methods

To examine the relationship between parenthood and political attitudes in the European context we rely on data from Round 4 of the ESS, which began fieldwork in 2008. There are now six rounds of the ESS that have included 31 different countries, 16 of which have been featured in every round, with typical sample sizes in each country and between 1,500 and 2,500 respondents.Footnote 2 We focus exclusively on Round 4 because it has the most countries available in a single round and because it is the only wave containing a module of questions focusing on the social welfare issues central to our hypotheses (ESS 2008).Footnote 3

We employ three dependent variables to assess the relationship between parenthood, gender and attitudes. In order to examine the first hypothesis regarding traditional gender role values, we create an index of two questions tapping attitudes that measure dis/agreement with the statements ‘Women should be prepared to cut down on paid work for the sake of the family’ and ‘Men should have more right to a job than women when jobs are scarce’. The scale has been ordered so that higher values indicate agreement and, hence, more traditional values. Second, we choose an explicitly parenthood‐related variable – support for a government role in providing child care – where higher values indicate strong preferences that government does not provide this service. Our final dependent variable is a government responsibility index, which captures the extent to which respondents believe it is the government's responsibility to provide key social welfare services including health care, unemployment, standard of living, support for the elderly and paid sick leave. We combine these five items into a single measure, again coded on a 0–10 scale, with higher values again indicating that respondents feel it is not the responsibility of the government to provide, which loaded on a single factor and had an alpha of 0.82. This index is very similar to the social welfare policy index used in analyses of American data (Elder & Greene Reference Elder and Greene2012: Chapter 6, Reference Elder and Greene2006; Howell & Day Reference Howell and Day2000) and allows us to explore the relationship between parenthood and social welfare attitudes on a set of issues that are not focused specifically on helping parents.Footnote 4

Our primary independent variables of interest are parenthood and gender. In order to capture and distinguish the relationship between gender and attitudes, from the relationship between parenthood and attitudes, as well as the interaction of gender and parenthood, we use two dummy variables – one for female respondents and one for whether the respondent has children at home – as well as the interaction between those two variables. The comparison category, therefore, is men without children, and the interaction term captures the effect for mothers. To measure parenthood we use a dummy variable coded 1 for children in the home, and 0 otherwise. This is a less than ideal measure of parental status as it does not actually include whether or not the respondents’ own children are in the home, but rather, only if any children are in the home.Footnote 5 Thus, in a small number of cases a respondent coded as a parent might be an older adult sibling, grandparent and so on. While not perfect, this is the best measure of parenthood provided in the ESS dataset (similar to most American datasets). Moreover, as a small percentage of those coded as parents are not, this should actually attenuate any significant results, thereby strengthening the significant results we do find.

Individual‐level control variables

We include a number of individual‐level variables in our models to serve as important controls in order to isolate the relationship between parenthood and attitudes. Because individuals with certain backgrounds and attitudes may choose to become parents, they may be distinct from non‐parents in ways that may also be related to our outcome variables of interest. We attempt to control for this insofar as we are able in a cross‐sectional dataset by including political, demographic and religious information about the respondents. Our basic demographic controls include employment status, union membership, age, education (dummy variable for tertiary education completed), marital status (dummy variable for married or living together) and race (dummy variable for member of a racial/ethnic minority in country).Footnote 6 For religion, we include a self‐assessment of personal religiosity.

Contextual variables

In addition to these individual level factors, we also take advantage of the large number of nations included in the ESS to explore country‐level effects on social welfare attitudes. We use two indicators of parental support policies: months of guaranteed paid or unpaid parental leave, and the provision of a universal child benefit (a direct payment to parents).Footnote 7H4 and H5 examine how the provision of these benefits condition the relationship between parenthood and attitudes, as well as help to explain variation across countries. We also control for the overall level of gender inequality in society, which may confound the relationship between parental policy, parenthood and political attitudes.Footnote 8

We use multilevel data with individual respondents nested within countries. Our approach is to first examine the variation in effects across countries and then to use a mixed effects model with the pooled sample. There are several considerations for the multilevel analysis. First, individual countries that are outliers in terms of the relationships we are interested in may affect our results. Therefore we perform an analysis for influential countries (see Supplementary Analysis in the online appendix). We also ran a series of Hausman tests for random effects. These tests for random effects will suggest where the effects of predictor variables of interest, such as parenthood, might significantly vary across countries or whether a fixed effects approach with dummy variables controls for the countries can be used. In general, these preliminary analyses suggest we can proceed with the full sample of countries and that we should account for random effects at the intercept.Footnote 9

Findings

Multilevel analysis

We estimate a series of multilevel mixed effects models to examine first how parenthood influences variation in attitudes and then we estimate a series of models with cross‐level interactions to examine how the policy context interacts with parenthood to shape attitudes. For the first set of models, we proceed in the analysis by first estimating a baseline model with only individual‐level variables and then estimate a second model with the contextual variables controlling for traditional values, which may act as a mediator between parenthood and political attitudes. For the second set of models, we take into account the part of our theoretical framework that examines how the relationship between parenthood and political attitudes varies by country – that is, in some countries we expect larger effects than in others. In a supplementary analysis (see the online appendix), we demonstrate this variation in effects in a country‐by‐country analysis.

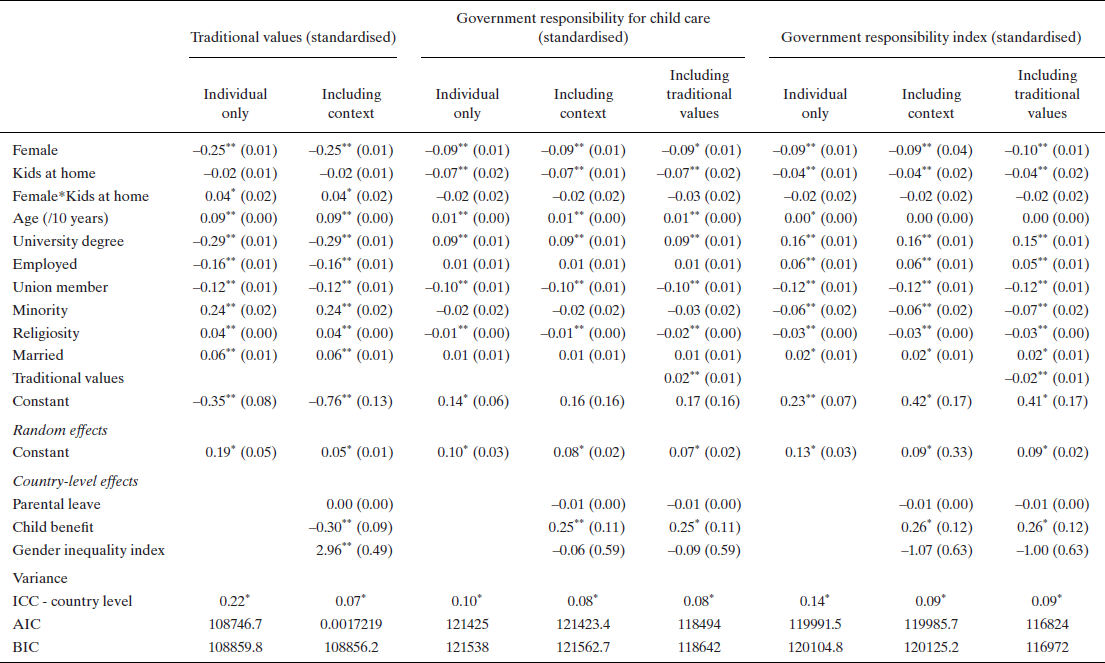

The results estimating baseline models (with and without contextual effects) of the impact of parenthood on traditional gender role values and attitudes about government responsibility are in Table 1. As mentioned, in order to capture and distinguish the relationship of gender and parenthood with attitudes we employ a dummy variable for female, a dummy variable for parent, and the interaction between female and parenthood in our models. The omitted, comparison category is men without children. In other words, a significant result for female would indicate that women without children have distinctive views from men without children, a significant coefficient for ‘kids at home’ would indicate that fathers hold distinctive views compared to non‐fathers (the residual category) and the interaction term of female‐kids at home would indicate that mothers hold distinctive views as compared to non‐fathers. We provide marginal and predicted values to indicate where mothers, fathers and non‐parents report different attitudes. The inter‐class correlation, the ratio of the between country variance to the total variance, is also reported.

Table 1. Multilevel models: Mothers, fathers and attitudes about government responsibility for policy areas

Note: Higher values indicate more conservative views. There are 28 countries represented in the analysis with a pooled sample size of 45,253. Estonia has been dropped as marital status is not available. Coefficient estimates are based on a mixed model with a random intercept. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

In the first set of models in Table 1, we see that women without children are significantly more likely to hold less traditional gender role values than men or parents once controlling for a range of other individual‐level factors. Using a standardised scale (z‐scores centred at the grand mean for the entire sample), women without children are, on average, over a quarter of a standard deviation lower on the traditional values scale. Women with children have slightly higher values on the traditional values scale than women without children. However, there are no significant differences between fathers and men without children. Overall, the biggest differences on values, therefore, are between women and men rather than between parents and non‐parents.

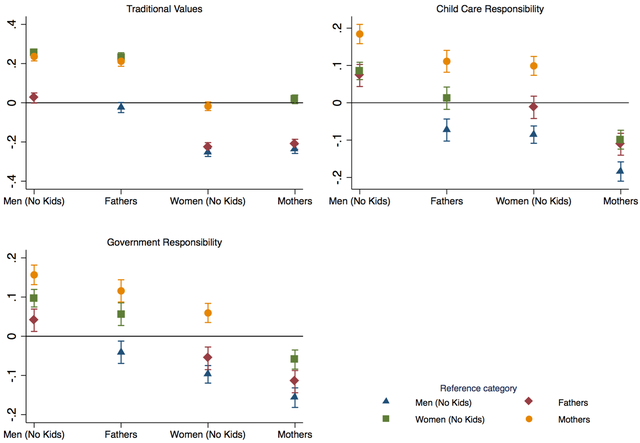

These effects are illustrated in Figure 1, where the differences between the predicted values for each reference category of parent and non‐parent is calculated with confidence intervals for these contrasts indicated by the capped lines. For example, the first figure and point estimates show the predicted traditional values score for the reference categories of women with no children, fathers and then mothers, subtracted from the predicted value for men with no children. Values above the reference line (positive) indicate where predicted values of the reference categories are to the left (or less traditional) of the reference categories. For the traditional values scale, these contrasts show that mothers and women without children are further to the left, while fathers and men without children are on the traditional side of the scale. The 95 per cent confidence intervals indicate that the differences between women and men are significant (confidence intervals do not include 0), whereas the differences between parents and non‐parents (i.e., the contrasts between fathers and men without children and between mothers and women without children) are not statistically significant (confidence intervals includes the reference line of 0).

Figure 1. Effect of parenthood on traditional values and government responsibility.

Notes: Point estimates are the differences in the predicted values between a category of parenthood/non‐parenthood against each other category. The 95 per cent confidence intervals for these contrasts are indicated by the capped lines. These contrasts in predicted values are based on estimates of the mixed effects model presented in Table 1 baseline models with contextual variables and including traditional values for the government responsibility scale and child care item. Predicted scores are based on holding all other values aside from parenthood and gender at their means.

Given the above results, our first hypothesis is not supported in that the largest difference in traditional values is between women overall who have less traditional gender role values in comparison to men, rather than a difference between parents and non‐parents. Mothers do hold slightly more traditional values than women without children, which is consistent with the results of other studies exploring the transition to parenthood in the United States and Australia using panel data and, therefore, controlling for selection effects (Baxter et al. Reference Baxter2014; Katz‐Wise et al. Reference Katz‐Wise, Priess and Hyde2010). However, the predicted values for mothers on the traditional values scale are not statistically different from predicted values for women without children. Once the contextual factors are introduced, the individual‐level effects for parenthood do not change, although there is a significant reduction in the interclass correlation.

We next turn to the relationship between parenthood and attitudes about government provision of child care and the government responsibility index (the second and third set of models in Table 1). Across both sets of models, we see that women without children are less conservative – that is, they are more likely to advocate government responsibility for providing services and, in particular, for providing child care services than men without children. These effects are statistically significant across all of the models and underscore the important role of gender in shaping social welfare attitudes in Europe even when parenthood, as well as a range of other demographic, attitudinal and contextual factors are controlled, just as is the case in the American context (Elder & Greene forthcoming).

However, unlike the results for traditional gender values, the coefficient for motherhood (female*kids at home) is significant and negative on government responsibility for child care when controlling for traditional values. Thus, and as illustrated in Figure 1, mothers are significantly more in favour of government responsibility for child care (less conservative). This is consistent with the idea that while women overall are more leftist on the issue of day care, that motherhood acts as an additional liberalising influence, pushing women even further to the left on this issue. As with traditional values, it is easier to illustrate the estimated effects by plotting the predicted scores for both the child care and government responsibility measures for the different groups of men and women. These predicted values are illustrated in Figure 1 along with the 95 per cent confidence intervals. The upper bound of the confidence interval for the predicted score for mothers falls below the predicted values for men without children and is aligned with the predicted values for fathers and women without children. These differences illustrate the additional impact of motherhood on attitudes about child care, and they suggest that parenthood can influence men and women differently.

The pattern of results is similar for the government responsibility index, though the coefficient for mothers does not reach traditional levels of statistical significance. However, as demonstrated in Figure 1, once all linear effects of gender and parenthood are combined to calculate predicted values, in general, fathers are less conservative than men without children and mothers are less conservative than women without children. However, mothers overall tend to be least conservative when it comes to government responsibility for social welfare policies in general and there are significant differences between mothers and men without children. Thus, parenthood is clearly an important factor behind the gender gap on social welfare issues in Europe as the largest effects are evident for mothers who are more likely to be on the left. Taken together, these results support our second hypothesis that motherhood is associated with more left‐leaning social welfare attitudes, and offers partial support for our third hypothesis concerning the relationship between fatherhood and social welfare attitudes. While fathers are not more conservative than non‐fathers, they are more conservative than mothers and women without children.

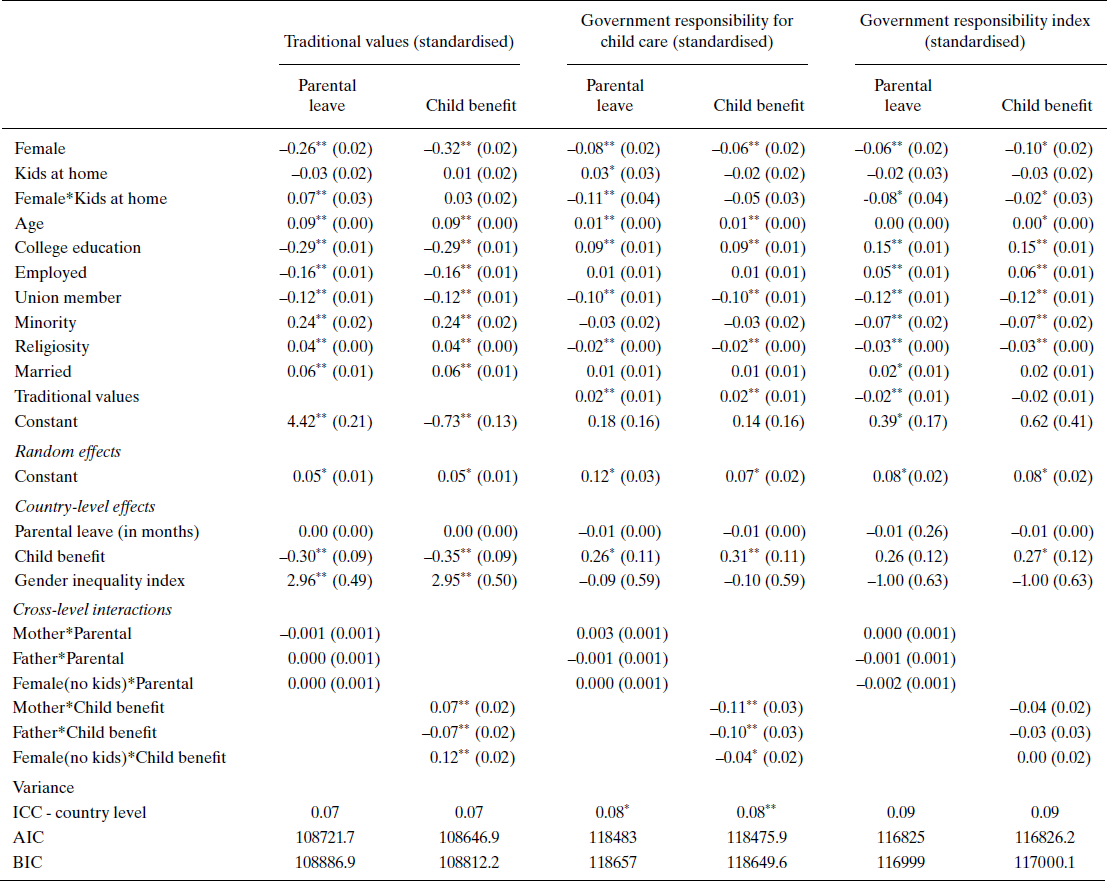

As for contextual effects on traditional values and social welfare policy attitudes, the results in Table 2 show that child care policy regimes and gender inequality do explain variation across countries. Specifically, we note that once contextual‐level variables have been added, the amount of variation at the country level, as indicated by the ICC, is dramatically reduced. This signifies that these policy‐ and country‐level differences can help explain the between‐country variation in attitudes, particularly for traditional values where the ICC is reduced from 0.22 to 0.07 once contextual factors are added. In general, where there is a universal child benefit, individual‐level attitudes tend to be less traditional, but higher levels of inequality are related to more traditional values. Consistent with our argument that a universal child benefit indicates societal support for a more traditional family structure, where there is a universal child benefit there is greater support for the position that the government should not be involved with providing child care specifically, and more generally, providing social services.

Table 2. Multilevel models: Mothers, fathers and attitudes about government responsibility for policy areas

Notes: Higher values indicate more conservative views. There are 28 countries represented in the analysis with a pooled sample size of 45,253. Estonia has been dropped as marital status is not available. Coefficient estimates are based on a mixed model with a random intercept. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

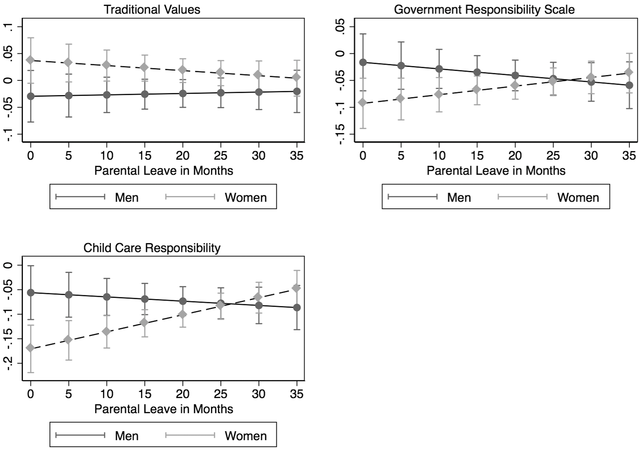

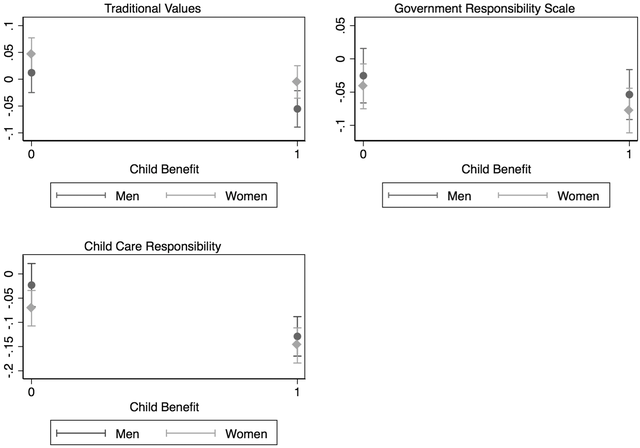

We next turn to our fourth and fifth hypotheses regarding how these contextual factors and policy regimes condition the impact of parenthood. In order to test the cross‐level interactions we include an interaction between categories of parenthood and each of our two policy indicators, months of parental leave and universal child benefit.Footnote 10 As the total effects for parenthood and the policy variable are the combination of linear effects across several variables, in order to better illustrate the cross‐level interactions we have generated a series of graphs plotting the marginal effects of parenthood for men in one line compared to the effects of parenthood for women at different levels of parental leave and child benefit policy. Figure 2 illustrates how the effect of parenthood across our three outcome variables is conditioned by parental leave. As per the earlier discussion of traditional gender values, the figure illustrates that the marginal effect of parenthood for men and women is not significantly different from a null effect and this does not significantly change at different levels of parental leave.

Figure 2. Effect of parenthood for men and women by parental leave policy.

Notes: Figures are marginal effects based on the mixed effects model presented in Table 2. The lines compare the effects on attitudes of being a parent for men and women at different levels of government provided parental leave with 95 per cent confidence intervals indicated by capped lines.

A different pattern is evident in the questions measuring government responsibility. Parenthood is associated with more polarised views for women and men in countries that offer less generous parental leave policies, where parental support is more consistent with the traditional male‐breadwinner model. This is consistent with our expectations in H4 and H5. Parenthood has a more conservative (positive) effect for men, while for women it is further to the left (negative) where there are fewer months of parental leave. There are particularly striking differences for the child care question. Parenthood does not polarise men and women where there is a generous leave policy, likely reflecting, in part. government responsiveness to public demands. This result supports the idea that mothers are most strongly politicised in situations where they do not have adequate support to help them balance their dual roles as workers and nurturers.

In the second set of graphs plotting marginal effects for parenthood by universal child benefit (Figure 3), we see that where there is a universal child benefit, indicative of a more conservative country‐level stance on parental support, the effect of parenthood is more to the left than where there is no such benefit. The effect for both mothers and fathers is leftist in these countries, and this left effect is statistically significant from no effect when compared to the parenthood effect in countries without a child benefit. Therefore, parenthood does not polarise men and women where direct child benefits are paid to families as we predicted in H5. Rather than the presence of a universal child benefit being a sign of a society that supports the traditional breadwinner model, which may in turn politicise mothers to demand more from government, it appears that both mothers and fathers, in countries that offer universal child benefits, demand more responsibility from their governments in terms of providing child care and social welfare programmes more broadly, and that, in turn, their governments are responsive to this. The strikingly different marginal effects for parenthood shown in Figure 2, focusing on parental leave policy, and Figure 3, focusing on child benefit policy, is most likely driven by the reality that both mothers and fathers benefit financially from child benefit policies, whereas women are more likely to take advantage of parental leave policies. Thus it is on policies that primarily benefit mothers where we see a polarising effect of parenthood, whereas the child benefit policy helps both mothers and fathers with direct payments and, as a result, it is not polarising.

Figure 3. Effect of parenthood for men and women by child benefit policy.

Notes: Figures are marginal effects based on the mixed effects model presented in Table 2. The lines compare the effects on attitudes of being a parent for men and women where the government provides an unrestricted child benefit versus countries that do not provide a child benefit with 95 per cent confidence intervals indicated by capped lines.

Conclusions

This study sought to extend parenthood research, conducted in the American context (e.g., Elder & Greene Reference Elder and Greene2012) into the contemporary democracies of Europe. We find parallels that are striking. Our results reveal that in Europe, parenthood is associated with distinctive attitudes on social welfare issues and is a significant contributor to the gender gap, much as is the case in the United States. Moreover, we find that country‐level factors such as a nation's family leave and child benefit policies condition the relationship between parenthood and attitudes in important ways consistent with the findings in the United States.

What citizens believe and why they believe it are crucial questions in democratic governments, and this research provides a number of key insights into the broader public opinion literature. First, this study contributes to our understanding of political attitudes across the life cycle. In contrast to earlier thinking that political attitudes harden in young adulthood, political scientists now agree that attitudes can and often do change throughout the life cycle. While studies have documented that there are attitudinal changes associated with key adult experiences such as joining the workforce, getting married, growing older and retiring (e.g., Andersen & Cook Reference Andersen and Cook1985; Pedersen Reference Pedersen1976), there has been much less research on parenthood, which rivals these other adult socialisation experiences in the way it changes the day‐to‐day lives of adults. This research dramatically extends the evidence that parenthood is associated with distinctive attitudes on social welfare issues, not just in the United States, but in a much broader cross‐national context. Research on public opinion in European democracies, therefore, should include parenthood alongside other key adult demographics such as marriage, age and workforce participation in explorations of political attitudes.

Moreover, this study shows that parenthood is associated with distinctive attitudes on social welfare issues in ways consistent with the gendered nature of contemporary parenthood. The fact that mothers are significantly more supportive of government's role in providing day care is likely driven by the reality that mothers, overall, continue to take primary responsibility for managing their children's child care experiences, and as a result, mothers have much more day‐to‐day contact with this particular government‐funded programme than fathers and therefore come to appreciate it more. Along similar lines, since women are the primary caregivers, they may benefit more from government programmes such as day care that ‘socialise’ mothers’ work (Iversen & Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006).

Motherhood is not only associated with greater support for government provision of child care, but with greater support for government provision of social welfare programmes not directly geared at helping parents. These differences tend to be larger than the differences between fathers and non‐fathers on this issue. Thus, there is something about contemporary motherhood in Europe, or the way that becoming a mother changes the social identity and political worldview of women, that seems to make them appreciate a more robust social welfare state. These results are consistent with the idea advanced by some feminist theorists that the nurturing work engaged in by mothers fosters a political world view characterised by more compassion for others and more support for government support for those in need (Elshtain Reference Elshtain1983, Reference Elshtain1985; Ruddick Reference Ruddick1989; Sapiro Reference Sapiro1983).

We observe that the largest difference in attitudes is between mothers and all other categories which may reflect the reality that despite a trend towards fathers spending more time with their children, as well as government policies incentivising men to get more involved, parenting is still largely ‘women's work’. As a result, parenthood appears to be a more intense and politicising experience for mothers than for fathers. Thus this research provides a more universal and contextual understanding of how deeply personal experiences, such as being a parent, shape political attitudes across Europe. Recognition that ‘the personal is political’ is not new. Nevertheless, until now, political scientists have failed to systematically examine the relationship between parenthood – one of the most life‐changing personal experiences – and political attitudes in Europe.

The results presented here support the growing subset of public opinion literature focused on policy feedback: the idea that not only does public opinion affect policy, but that policy affects attitudes (Kumlin & Stadelmann‐Steffen Reference Kumlin and Stadelmann‐Steffen2014: 4). This cross‐sectional study suggests that not only do state‐level variations in parental policy shape attitudes, but they condition the relationship of parenthood and political attitudes in important ways. Looking at how the relationship between parenthood and political attitudes varies across nations that provide generous parental leave policies and those that do not adds further support to the idea that women with children desire greater government services, particularly in countries that do not already provide robust services. Our results show that where governments fail to implement policies that help women balance work and family, such as family leave policies, mothers and fathers are significantly polarised with mothers more likely to desire greater government responsibility for providing day care and other social welfare services and fathers less so. The conditional effects suggest that in countries without strong parental leave policies, mothers appreciate policies that help them combine work and family, whereas fathers may be more concerned with the impact of an expanding welfare state on their paychecks and ability to provide for a family. This result may help explain the polarising effects of parenthood in the United States, given its distinctive lack of paid parental leave.

The results on our government responsibility items also show that parenthood affects men and women, in some contexts, in polarising ways. This means that studies that talk about parenthood or include a parent variable in their models, not differentiated by gender, are missing and/or distorting a big part of the story. Also, this indicates that parenthood is one of the drivers behind the gender gap on social welfare issues in European countries. While the gender gap on social welfare policy remains even among women and men without children, the role of parenthood in further polarising women and men is important to acknowledge. Scholars interested in understanding the dynamics behind the contemporary gender gap in public opinion and vote choice in European democracies may gain additional insights by considering parenthood, broken down by gender, in their analyses.

Finally it is important to underscore, once again, the limitations of the data employed here. While the ESS contains comprehensive cross‐national data, it only includes data from one point in time. Therefore, while the results presented here show compelling relationships between parenthood and important policy attitudes, we are not able to control for selection into parenthood or demonstrate individual‐level change over time. It is our hope to utilise panel data in future studies to subject the intriguing findings discussed here to more direct empirical tests.

Acknowledgement

The work of Banducci and Stevens was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/H030883/1).

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Online Appendix: Variables and measurement