Introduction

On 18 May 1843, a schism, or ‘Disruption’, of the Church of Scotland took place, when ministers supporting the long-running campaign against the intrusion of the state in matters relating to ecclesiastical governance dramatically walked out of the annual meeting of the church’s General Assembly, held that year in St Andrew’s Church, Edinburgh. Led by the charismatic Rev. Dr Thomas Chalmers, they convened at the nearby Tanfield Hall to sign an Act of Separation and Deed of Demission, by which they signalled their intention to quit the established church, voluntarily renouncing their rights to salary (stipend) and accommodation (church and manse). Of the 1,195 clergymen in the Church of Scotland, 454 or 38.1% joined the newly constituted Free Church of Scotland.Footnote 1

From the outset, Chalmers maintained that the Disruption was not merely another denominational secession, but a severing of the historic relationship between church and state in Scotland. At the Free Church’s first General Assembly meeting he declared: ‘though we quit the Establishment, we go out on the Establishment principle; we quit a vitiated Establishment, but would rejoice in returning to a pure one. To express it otherwise – we are the advocates for a national recognition and national support of religion – and we are not Voluntaries.’Footnote 2

The Free Church was thereby committed, from its inception, to offering the ordinances of religion nationally. That meant not only the rapid recruitment of a ministerial labour force sufficient to cover every parish in Scotland, but also the equally onerous task of duplicating the established church’s physical infrastructure, its national network of church buildings and manses, to accommodate its new members and adherents. The immediate and most pressing challenge facing the newly created church was therefore financial.Footnote 3

The economic context within which the nascent church met this challenge was extraordinarily difficult, with Highland Scotland in the mid-1840s suffering the disastrous effects of potato blight, poor harvests and famine. Yet by May 1847, the progress of the Free Church, measured in terms of money raised, stipends paid and buildings erected, had greatly exceeded the expectations of the sceptics. In total, over £312,000 had been contributed to the centrally managed Sustentation Fund for the support of the ministry. Through it, 590 ministers were in receipt of a minimum stipend (known as the ‘Equal Dividend’) of £120, with another 83 enjoying a lesser level of financial support (Table 1). In addition, the church claimed to have built or taken possession of a total of 730 churches,Footnote 4 and had a leadership which included amongst its number ‘the most prominent, able and zealous members of the established church’.Footnote 5 Taken together, the Free Church of Scotland could fairly be judged to have met its core objective of establishing an organization supporting a territorial ministry across the whole of Scotland within just four years of the Disruption.

Yet, despite this early success, the Free Church’s financial progress thereafter lost momentum, and, with it, faded the hope of dislodging the Church of Scotland from its position as the numerically largest national church. Indeed, over the following three decades, the latter not only survived, but enjoyed a remarkable recovery,Footnote 6 with a successful fundraising campaign enabling it to extend its reach amongst the general population, whilst embracing progressive theological debate and innovative liturgical practice.

In contrast, the Free Church found itself increasingly driven to rein in its church extension ambitions, as the perennial need to raise funds for its entire range of activities through voluntary giving weighed on it more and more heavily.Footnote 7 This was the enduring general financial challenge that it faced. Equally important, however, was the very specific need to develop and sustain a system for redistributing the funds it raised to support ministers and ministries in the poorest and most sparsely populated parts of Scotland – the peripheral rural areas – without which it would have been unable to fulfil its mission as a national church.

This article describes and analyses how the Free Church met the challenge of redistributing its funds for the support of its national ministry, from urban centres of population to the rural periphery, through the development and operation of its most important financial system, the Sustentation Fund. Throughout the nineteenth century, this was the primary means by which the church financed, and thereby maintained, its presence throughout Scotland, through the ingathering and redistribution of money raised by its local associations and congregations. Characterizing the Sustentation Fund as an archetypal cross-subsidy scheme, this article draws on published financial information to analyse, for the first time, the direction, and calibrate the scale, of the extensive urban-rural cross subsidies, from the 1843 Disruption to the union of the Free and United Presbyterian churches in 1900.

To date, studies describing the development of the Free Church during this period, whilst rich in insights relating to politics, society and culture, have generally paid relatively little attention to the detail of the organization’s finance and economics;Footnote 8 ironic in light of the prominence given to these matters by Chalmers and other early Free Church leaders.Footnote 9 This article’s contribution to the existing literature rests therefore on its deployment of financial data to enrich and extend current narratives of the church’s financial development, particularly in relation to the financial sustainability of its national mission. In particular, it throws new light on the question of why the Free Church took so long to secure the modest ministerial stipend payment of £150 agreed at its inception. This, it is argued, resulted from the church’s inability to resolve incentive problems typical of cross-subsidy schemes and intrinsic to the design and operation of the Sustentation Fund.

The findings also have wider relevance to the study of the mid-nineteenth-century recovery of the established Church of Scotland,Footnote 10 in that the challenges posed by the Sustentation Fund framed, and ultimately constrained, the Free Church’s ability to respond energetically to the established church’s revival.

Anticipating and Realizing a Disruption

The Disruption of 1843 was the culmination of a decade-long struggle between established church and state over the right of local patrons, typically wealthy landowners, to present a minister of their choice to vacant parish charges. It was played out, however, against a background of political, ecclesiastical and economic events, which were reshaping Scottish society in a quite fundamental way.Footnote 11

Politically, the British parliament had, between 1828 and 1832, enacted three landmark reforms: first, in 1828, the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, granting Protestant Dissenters full civil and political rights; second, in 1829, the Catholic Emancipation Act, granting Roman Catholics the right to sit in Parliament and to hold most public offices; and third, in 1832, the Reform Act, which swept away old parliamentary boundaries, broadening the franchise and increasing parliamentary representation in the rapidly growing urban areas. Within this new political context, the existing ecclesiastical settlement, in particular the pecuniary privileges of the established churches across Britain and Ireland, came under pressure.

In Scotland, Protestant Dissenters, led by Andrew Marshall, a leading minister of the United Secession Church, launched a ‘Voluntary’ campaign to disestablish and disendow the established Church of Scotland. By the early 1830s, voluntary church associations had sprung up in all of Scotland’s major towns and cities, challenging and disrupting established church activities in the name of ‘Voluntaryism’.Footnote 12 Within the Church of Scotland, the evangelical party, committed to the parish ministry, overseas mission and a concern for Christian discipline and formation, took control of the church’s General Assembly from the moderate party in 1834, adopting a more robust approach to church defence and extension, whilst campaigning for the abolition of patronage.

Economically, the forces unleashed by the Industrial Revolution continued to incentivize agricultural labourers in rural areas to migrate to urban areas to work in rapidly growing industries, from those supporting the production of iron, to the spinning and weaving of cotton. Improving transport networks were, at the same time, creating national markets for goods, while overseas markets were gradually being opened up by entrepreneurial merchants commissioning shipping to export the products of industry. The benefits of economic growth were, however, unevenly spread; and a new wealthy mercantile middle class emerged, soon to deploy its power in the political arena. As the 1840s began, the country’s political and ecclesiastical leaders could not foresee the extent of suffering soon to be visited on the country through the repeated failure of the potato crop.

Against this background, in the anticipatory planning for a break with the established church, the leaders of the Free Church were clear that substantial sources of finance had to be identified and exploited rapidly lest the entire project be stillborn. Denied access to the Church of Scotland’s primary sources of income – parish teinds, government and church endowments – they also recognized the criticality of building an organizational structure to support fundraising mechanisms that would secure the ongoing sustainability of financing arrangements, thereby guaranteeing the church’s survival.Footnote 13 Chalmers and the other church leaders reluctantly but pragmatically concluded, therefore, that voluntary giving would, perforce, be the financial bedrock on which the church was built.

The scale of the voluntary fundraising task, unprecedented in Scotland’s ecclesiastical history, had been outlined by Chalmers at a convocation of evangelical ministers held in Edinburgh in November 1842. Here, he promised not only to raise funds sufficient to build a national network of churches and manses, but also to provide at least £100,000 per annum for the support of clergy quitting the establishment. This was an extraordinarily ambitious objective and claim, greeted by some of those attending with incredulity.Footnote 14

To achieve the ultimate goal of a national church funded sustainably through voluntary contributions, Chalmers drew on the experience from two key periods of his ministry. First, the period 1819 to 1823, when, as minister of St John’s parish, Glasgow, he had sought to reinvigorate the traditional parochial system within the context of an impoverished urban area.Footnote 15 Second, the period 1834 to 1841, when he led the Church of Scotland’s church extension campaign, adding over 200 churches to its stock in the face of a well-organized and increasingly vocal Voluntary campaign.Footnote 16

Chalmers presented to the convocation the key features of a centralized arrangement for the ingathering and distribution of money: the Central or Sustentation Fund scheme. The scheme required local congregational associations to organize in order to collect and remit funds they had raised, on a quarterly basis, to the church’s headquarters in Edinburgh. The pooled funds were then to be redistributed through an ‘equal dividend’ paid annually to every minister of the church, regardless of the contribution of his local congregation. In this way, ministers serving remote and economically poor rural areas – particularly the Highlands and Islands – would be guaranteed a basic minimum stipend. Chalmers was clear, however, that money remitted to the Fund should not be directed exclusively towards the stipends of existing clergy. Importantly, it was to fund church extension through the employment of new territorial missionaries and to organize congregations in districts lacking a Free Church presence. Nevertheless, having met their obligations under the scheme, local congregations would be permitted to supplement their own minister’s stipend, raising it above the level of the equal dividend.

At the close of the convocation, Chalmers energetically initiated the formation of local societies or associations, whose primary purposes were the organization of congregations and the collection of funds. The first of these, established in December 1842, was formed near his home in the parish of Morningside, Edinburgh. Under the auspices of a new Provisional Committee created in February 1843, travelling agents were sent around the country to organize new associations, often through the revival of dormant local societies of his church extension movement.Footnote 17 By the day of the Disruption, 687 local associations committed to financially supporting the Free Church were in existence throughout Scotland.Footnote 18 Within four years, just under 700 ministers had been employed to serve a network of 730 churches stretching across the entire country.Footnote 19

Emerging Financial Challenges

Despite such rapid progress, there were early signs that support for the Sustentation Fund was waning, and a view emerged that failure to meet its ambitious financial targets posed an existential risk to the entire Free Church project. In presenting the annual report on the Sustentation Fund to the Free Church’s 1848 General Assembly, Dr Robert BuchananFootnote 20 noted that, because of inadequate fundraising, the equal dividend – i.e. base ministerial stipend – had fallen back from £122 in 1846, to £120 in 1847,Footnote 21 well short of the £150 target set at the Disruption. Several reasons for this were offered: the church’s rapid expansion, whereby the number of new ministers admitted to the equal dividend ‘platform’ outstripped increases in funds raised to support their stipends; the energy diverted towards fundraising efforts for church, school and manse building projects; and the extraordinarily challenging external economic environment. In addition, Buchanan advanced the view that responsibility for the success or failure of the Sustentation Fund lay not with the church’s Sustentation Committee, but with local churches, their ministers, elders and deacons, without whose active advocacy, he argued, any actions by the church’s central bureaucracy, based in the capital, would be ineffective:

In efforts of this kind we have no system of electric wires, to propagate from a single centre the influence that will reach in undiminished force the remotest extremities. A touch in Edinburgh, whether in the shape of a speech or a circular, tells very feebly by the time it reaches the Pentland or Solway First, and in truth is not felt at all in many places much nearer to hand. (Hear, and a laugh.)Footnote 22

Furthermore, he argued, if the local courts of the church failed to take up their responsibilities to support the Fund the consequences would be catastrophic for the church:

the Deacons’ Courts that neglect this Fund are thereby doing what in them lies to destroy the Free Church of Scotland … let Synods, Presbyteries, and Deacons’ Courts undervalue and trifle with this fundamental interest, and there is no power or agency which the [Sustentation Fund] Committee can employ that will long avert the decline and fall of the Sustentation Fund, and with it our national Free Church.Footnote 23

Aware of the growing precariousness of the church’s financial position, Buchanan, on his appointment as convener of the Sustentation Fund Committee in 1847, led a programme of presbytery visits or ‘conferences’ to explore the reasons for shortfalls in financial contributions to the Sustentation Fund, and to encourage greater efforts in its promotion. From June 1847, accompanied by the superintendent of associations, Mr Handyside, he travelled to sixty presbyteries within a year, meeting with two office-bearers and the presbytery elder for every congregation within each presbytery’s bounds. The purpose of these meetings was to establish and agree an amount of money which individual congregations would be ‘recommended and urged to raise’.Footnote 24 Through this work, Buchanan became aware of an underlying problem, which simple exhortation was incapable of addressing. That problem was financial free-riding, or the propensity of some congregations to limit their contributions to the Fund, relying instead on the generosity of others to maintain the level of the equal dividend.

Cross Subsidy

As originally conceived by Chalmers and Candlish, the Sustentation Fund was to be the mechanism by which contributions from individual church congregations for the support of the ministry would be pooled and reallocated on a common basis. Regardless of the level of contribution by any individual congregation, every minister was to receive the same equal dividend stipendiary payment. Thus, in design and operation, the Sustentation Fund was, in essence, a vast cross-subsidy scheme in which the link between the amount paid into the Fund by a congregation, and the amount paid out to that congregation’s minister was severed.

The need for cross subsidy emerged from the conjunction of the Free Church’s desire to offer the ordinances of religion nationally, and the vast difference in prosperity between the wealthy urban areas, such as the cities of Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen, and the poorer, peripheral rural areas, particularly the Highlands and Islands.Footnote 25 Without some means of transferring resources between these areas, the church would be unable to provide sustainable staffing for sparsely populated rural parishes and would thereby fail to fulfil its national mission. Instead, it would be obliged to focus its work in the relatively affluent cities and provincial towns.

Cross-subsidy schemes in which participants are not, or cannot be, excluded from some or all of the benefits enjoyed by its members, are open to exploitation through self-interested strategic behaviour. Without exclusion, free-riding behaviours are incentivized.Footnote 26 If not arrested, these individual behaviours undermine the collective arrangement, risking the collapse of any cross-subsidy scheme.Footnote 27 This risk, and the necessary mitigations, was fully understood and clearly articulated by Chalmers in his 1846 cri de coeur, An Earnest Appeal to the Free Church of Scotland on the Subjects of its Economics. Footnote 28

On the question of exclusion, which meant limiting the number of minsters admitted to the scheme, Chalmers took the view that the benefits of the equal dividend should be strictly restricted to those who had ‘come out’ of the Church of Scotland in 1843.Footnote 29 He further noted the problem of free-riding, with ‘many congregations in certain parts of the Church, who, trusting to the more generous or wealthy congregations in other parts of it, fall miserably short in their contributions to the Central Fund.’Footnote 30 Furthermore, this brought the associated problems of cross-subsidy ‘addiction’ on the part of net beneficiaries, and ‘aid fatigue’ on the part of net contributors.Footnote 31

Nevertheless, Chalmers was pragmatic enough to understand that permanent cross subsidy would be required for the poorest congregations of a national church. In characteristic style, he urged those in the most adverse situations to do all they could to reduce their dependence on financial subsidies.Footnote 32

By 1848, Buchanan was able to offer the Free Church General Assembly a compelling narrative based on information gathered from presbytery ‘conferences’ which corroborated Chalmers’ earlier analysis. On the problem of free-riding he observed:

It is to be feared there are congregations not a few that are taking their ease in this matter somewhat selfishly, and without much concerning themselves as to the burden they may be thereby imposing upon others. Nothing, indeed, can be more delightful than to see the abundance of one congregation supplying the want of another, where that want is real. But, on the other hand, nothing can be more offensive than to find the apathy, or indolence, or niggardliness of one congregation pillowing itself on the self-denying labours and sacrifices of another perhaps poorer than itself. (Applause.)Footnote 33

Buchanan went on to calibrate the extent of the problem at that date:

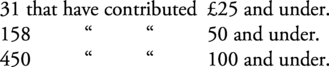

It is necessary, Sir, at this point, that I should present some statistics, from which it will sufficiently appear how very limited are the contributions which many of our congregations make to this Fund, and how reasonable it is both to ask and expect that increase which the Assembly has proposed.

Of the 698 ministerial charges of the Free Church, there are

It thus appears that considerably more than two-thirds of our whole income are contributed by one-third of our congregations; and these 450 congregations cost the Fund this year, beyond their own contributions, £30,728:5:3. (Hear). I just ask, without going into details, whether any man can credit the supposition that there are not among these 450 congregations many which ought to be independent of such assistance.Footnote 34

Buchanan’s presbytery ‘conversations’ were just one of several initiatives taken which, throughout the life of the scheme, sought to address its shortcomings as a means of supporting a national ministry. Modifications to the Sustentation Fund’s rules and associated advocacy occurred repeatedly, as the church sought to increase the equal dividend and to extend it to a growing number of ministers.

Sustentation Fund: Initiatives and Innovations

Although committing itself, at the 1843 Disruption, to achieving a £150 equal dividend, the church first met this target a full quarter of a century later, in 1868. The failure to achieve this objective and suggestions as to how persistent financial shortfalls might be made good were, throughout this period, the leitmotif of annual reports of the Sustentation Fund Committee to the church’s General Assembly.

Two general types of approach to the deficiency were taken by the Committee during this period. First, changes to the rules of the scheme itself. Second, centrally coordinated campaigns of visitation by Sustentation Committee representatives to presbyteries for exhortation and encouragement. The fortunes of each approach were mixed as the following examples illustrate.

In 1844, under the leadership of Chalmers, the ‘Half-More System’ was introduced.Footnote 35 The purpose was to limit the number of ministers being admitted as full beneficiaries of the equal dividend, and to incentivize the giving of congregations to the Fund. A rule change determined ‘[t]hat every minister admitted to a new charge shall receive from the Sustentation Fund the contribution of his Association, if up to or less than £100, and the half more.’Footnote 36 Thus, for example, the minister of a congregation contributing £80 to the Fund was entitled to receive back £120. Importantly, ministers ordained before Whitsunday 1844 were excluded from the change and continued to receive the full equal dividend.

The arrangement proved unpopular amongst the clergy from the beginning, with opposition amongst the recently ordained being particularly marked.Footnote 37 Therefore, at the May 1848 General Assembly, after the death of Chalmers in May 1847, the scheme was ended with the equal dividend principle offered as the justification:

That the principle of an equal dividend in distributing the Central Fund, ordained by the General Assembly which met at Glasgow in 1843, ought to be maintained; and that the deviation from that principle introduced by the Resolutions of the Assembly of 1844, has been found inexpedient, and should be gradually terminated … .Footnote 38

The process of transferring ministers from the half-more scheme to the full equal dividend began in 1848; it continued until 1852, thereby placing further pressure on the Sustentation Fund, leading to falls in stipend. Buchanan’s extensive national programme of visitations, entitled presbytery ‘conferences’, in 1847–8 mitigated the effect of this somewhat by giving a boost to Fund donations. However, the marked step up in the level of donations to the Fund did not endure the removal of the temporary stimulus of the presbytery conferences, and the equal dividend thereafter fell back as ministerial numbers continued to rise at a rate faster than the donations would support.Footnote 39

In 1853, the Sustentation Fund Committee sought to arrest continuing falls in the equal dividend by introducing a new rating system. This had two elements. First:

the particular sum which each congregation is to be expected to contribute to that fund shall henceforth be arranged by the Deacons’ Courts, with the concurrence of the Committee on the Sustentation Fund … That in every case in which the Deacons’ Court and the Sustentation Fund Committee shall agree as to the amount of the stipulated contribution, the congregation shall take its place in the present scheme, and be entitled to participate in all its provisions.Footnote 40

Second, a ‘Supplementary Sustentation Fund’ was established. This was a capital fund, designed to receive the amounts raised excess to that agreed, and entitling contributing congregations to draw a pound for every pound deposited to supplement their minister’s stipend up to a limit of £150.

This rating system was regarded as highly interventionist, and quickly became deeply unpopular.Footnote 41 The May 1855 General Assembly brought it to an end,Footnote 42 again citing the equal dividend principle in rationalizing this action:

that the plan of an Equal Dividend is better fitted than any other yet proposed to secure the ends for which the Sustentation fund was instituted and is maintained; and, while it is desirable to adopt measures for preventing the decline of the Equal Dividend, through the failure of congregations to discharge their duty, these measures ought to be such as tend to preserve the general principle of the plan.Footnote 43

In ending this initiative, the same 1855 General Assembly praised another devised by Buchanan a year earlier, the ‘One-Fourth-More movement’.

In August 1854, Buchanan presented to a meeting of the Commission of the General Assembly a visitation plan for the purpose of promoting giving to the Sustentation Fund. Modelled on his successful 1847–8 presbytery ‘conferences’, a series of deputies, appointed by the Sustentation Fund Committee, were delegated to visit congregations and deacons’ courts throughout the country. This time they were tasked with conveying a specific request in order:

not merely to press upon them the necessity of vigorous and united action to obtain an increase in the fund, but to lay before each of them the definite proposal of endeavouring to realise an increase of one-fourth upon their previous rate of contribution. This proved to be the most successful appeal that had yet been made. It set before each congregation a specific thing to do – a thing that, unless in very exceptional cases, could without difficulty be done.Footnote 44

This initiative proved extremely effective, and with a large uplift in income to the Fund, the equal dividend rose from £119 in 1854, to £132 in 1855.

For the next decade, only minor modifications to the operation of the Fund were adopted and the equal dividend remained stubbornly below the target of £150, despite Scotland’s growing wealth and the rise in salaries paid in other professions. At the 1867 General Assembly, the inadequacy of the minimum stipend was again noted, and a resolution passed raising the target minimum from £150 to £200.Footnote 45 More significant in terms of the operation of the Fund was the creation of a Surplus Fund.

The Surplus Fund was to receive the surplus of the annual revenue of the Sustentation Fund once it had paid the £150 equal dividend to all entitled. However, the critical innovation was that distributions from this fund were to be made according to congregational giving per head, with thresholds set at 10s. and 7s. 6d. No congregation giving less than £60 per year was to be entitled to participate in the fund. Those congregations giving 10s. or more per head would receive a distribution from the Surplus Fund, and those giving between 7s. 6d. and 10s. would receive an amount half as large as that offered to the 10s. or more congregations. No minister was to receive more than £50 from the Surplus Fund; however, should support be forthcoming, the church would thereby secure stipends of £200 for all its ministers: £150 through the equal dividend, and £50 from the Surplus Fund.

Incentivized by this new initiative, the equal dividend finally achieved the £150 target the following year, advancing to £157 in 1875, and £160 in 1879. The arrangements were reviewed again in 1874, and two further targets were formally adopted by the church. These were the attainment of a £200 stipend for all ministers, and a minimum contribution rate of ten shillings per member per year. Further minor amendments to the Sustentation Fund’s operations occurred in 1877, 1889 and 1895.

Although the various innovations did modify the way in which the Sustentation Fund operated, its essential character, as a means by which the ministerial stipends of those serving poorer congregations were cross subsidized by those serving richer congregations, remained intact from the time of the Disruption to the Free Church’s union with the United Presbyterian Church in 1900. The Free Church ministry as a whole proved reluctant, throughout the whole of this period, to surrender the principle of the equal dividend, or to restrict admission to the equal dividend platform as of right to all inducted to serve a congregation. The warnings of Chalmers and the ‘Half-More Scheme’ designed to incentivize giving did not, through accident or design, fundamentally shape the operation of the scheme after his death.Footnote 46

Calibrating Cross Subsidy

In order to assess and calibrate the quantum and direction of cross subsidy across time, data extracted from the Free Church’s financial records – primarily the church’s annual accounts and Sustentation Fund reports to the General Assembly – are deployed and analysed.

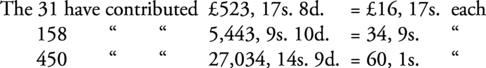

Table 1 records the annual amounts contributed to the Sustentation Fund; the number of ministers participating in the Fund; the equal dividend agreed at annual meetings of the Free Church General Assembly; and the number of full equal dividend payments made. The positive impact on overall giving of the One-Fourth-More movement (1854) and the creation of the Surplus Fund (1867) are clearly evident. It may be further observed that relatively large rises in the number of ministers participating in the Fund, for example in 1849 and 1857, coincide with moderations in the progress of the equal dividend. However, this is generally only one of a number of causal factors in play at these points in time.

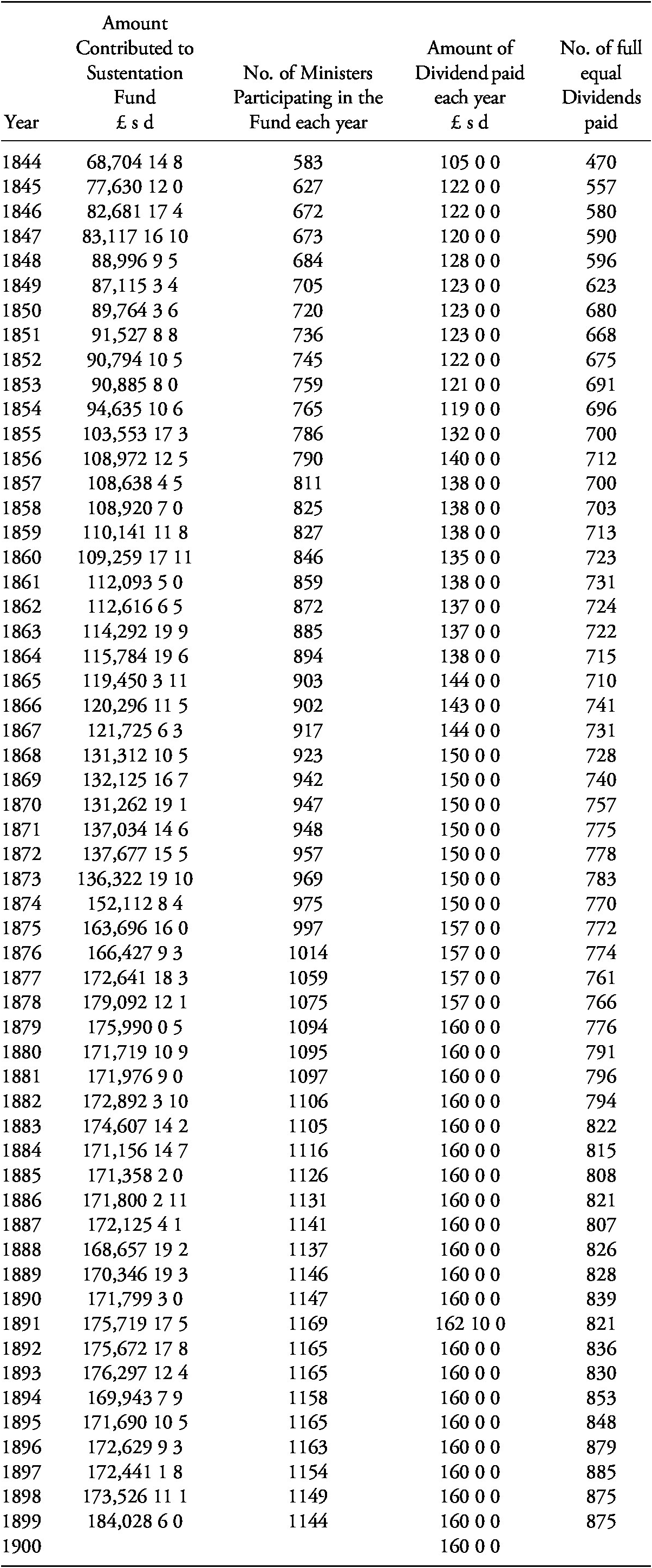

In Table 2, the national position with respect to financially self-sustaining congregations is set out. Using the church’s own definition of a self-sustaining congregation – one in which contributions to the Sustentation Fund exceed the equal dividend in any one year – it is clear that, throughout the period, fewer than a third of congregations exceeded this threshold. For years in which data on the number of congregations were published, the proportion contributing more than the equal dividend ranged from 19.6% to 34.0%. For each advance in the equal dividend, it was generally the case that the number and percentage of congregations recorded as being self-sustaining temporarily fell back. It should further be noted that the overall position is flattered by the use of the equal dividend as the benchmark throughout, rather than the target stipend, which, from 1867 onwards, was £200.

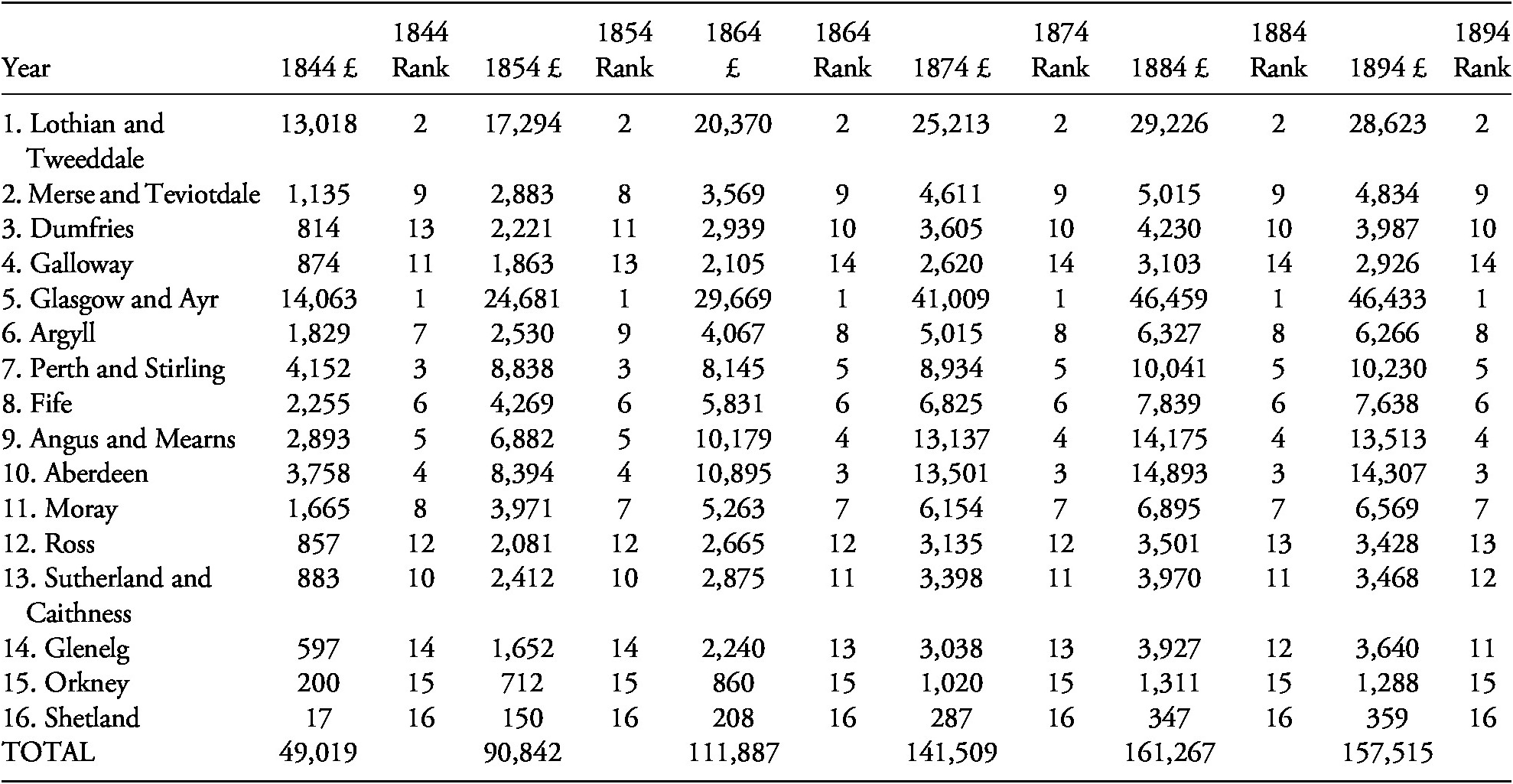

In Table 3, a more detailed geographical analysis is offered with decennial observations of congregational contributions to the Sustentation Fund aggregated by synod. This clearly reveals the regional disparities in absolute and relative terms. Two synods – Glasgow and Ayr, and Lothian and Tweeddale – dominate all others in terms of total financial contributions, in contrast to Shetland and Orkney, whose funds raised were extremely modest throughout the period. More generally, the synods containing the largest urban conurbations made the largest absolute and relative contributions throughout the period of study, with those located at the greatest distance from the towns and cities, the geographical periphery, making the lowest contributions.

Thus, as a percentage of all giving, the proportions of the church’s total contributions made by the synods covering Scotland’s leading cities – Lothian and Tweeddale (including Edinburgh), Glasgow and Ayr (including Glasgow), Aberdeen (including Aberdeen), and Angus and Mearns (including Dundee) – were 68.8% in 1844, 63.0% in 1854, 63.6% in 1864, 65.6% in 1874, 64.9% in 1884 and 65.3% in 1894.

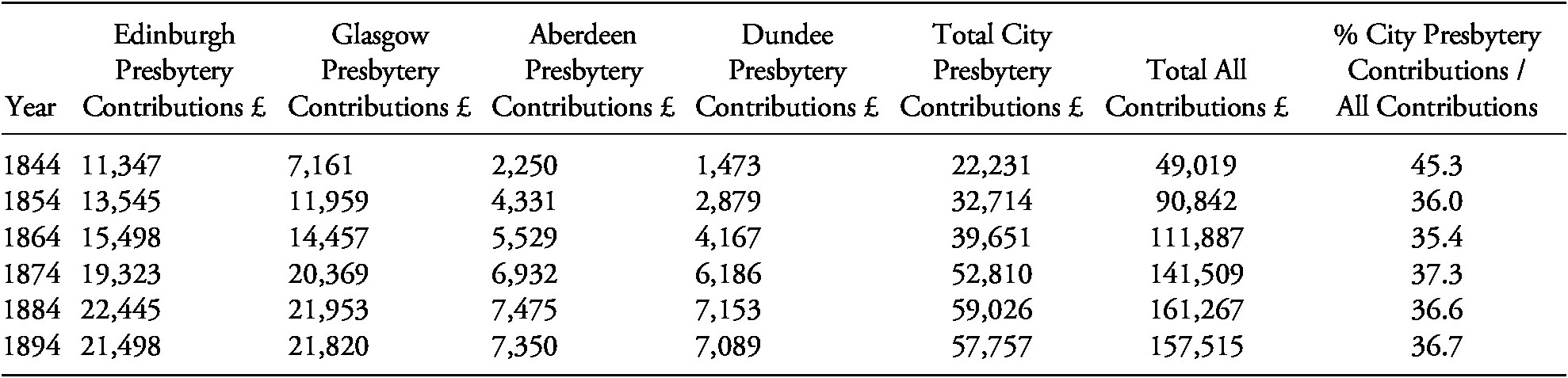

Analysing the data at the sub-synod, presbytery level, Table 4 presents the amounts given by the four city presbyteries alone. Despite the reduction in the range and number of congregations covered by this narrower definition, the percentage of contributions by city presbyteries to the Fund was substantial, ranging between 45.3% in 1844 and 35.4 in 1864, generally accounting for just under two-fifths of the total.

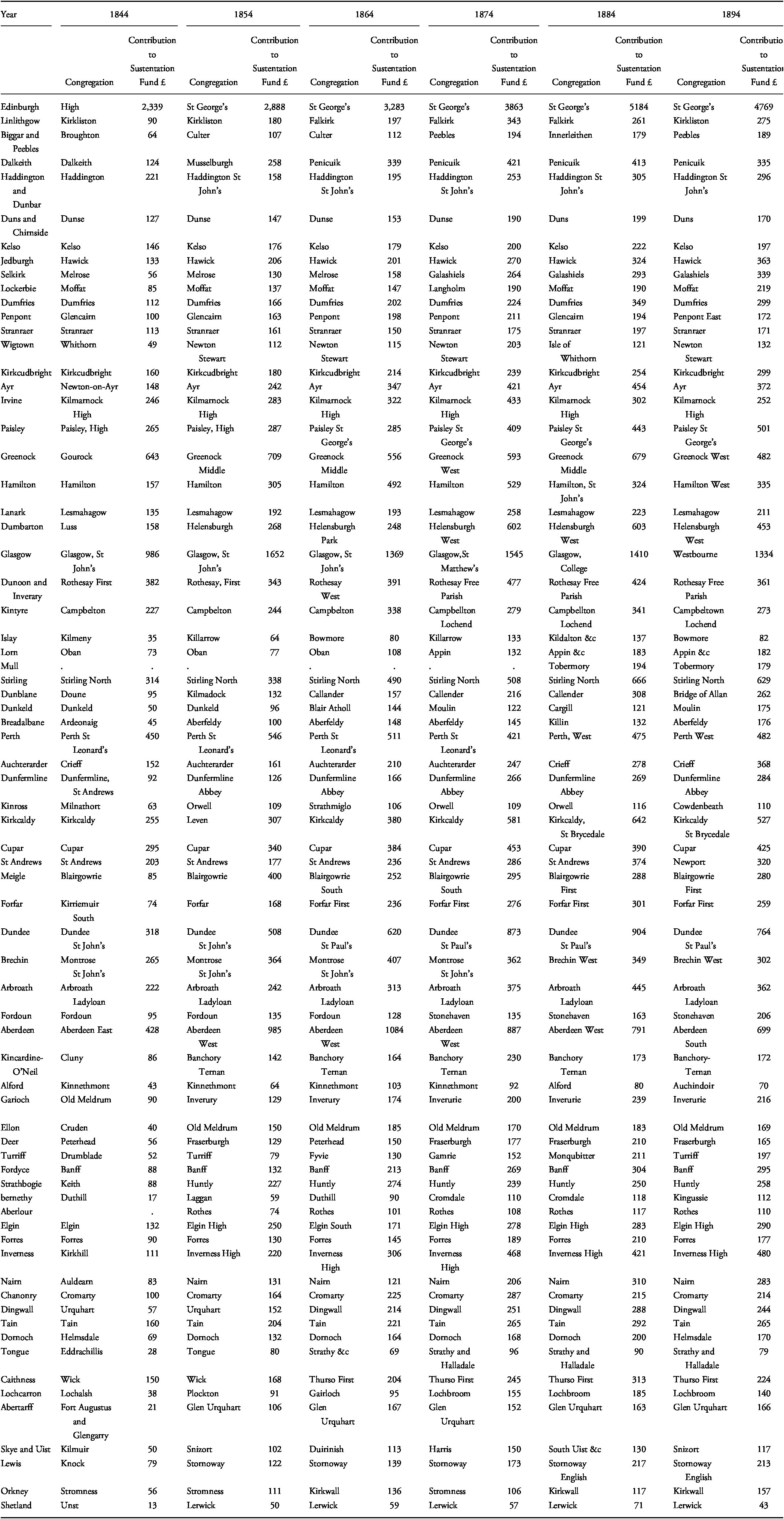

In Table 5, the largest contributions to the Sustentation Fund by congregation for every presbytery at decennial frequency are presented. Two results stand out. First, the consistency of the identity of the most generous congregations (in absolute terms) throughout the period. In just under four-fifths of the presbyteries, one or two congregations are listed as being the largest contributors. Second, evidence of a decrease in giving by the highest contributing congregations towards the end of the period, with fifty-one of the seventy-two most generous congregations by presbytery recording a reduction between 1884 and 1894; a result consistent with the hypothesis of aid fatigue.

Within this subset of congregations, the position of St George’s Free, Edinburgh, is notable for the relative and absolute size of its contributions. To put this into context, in terms of total synod contributions (Table 3), St George’s Free, by itself, would have ranked twelfth by contribution level in 1854, and tenth by contribution level in 1894. This represented 21.3% and 22.2% of the total contributions of the presbytery of Edinburgh in the respective years; indicative of the critical importance of, and increasing reliance on, the fundraising efforts of this leading urban congregation.

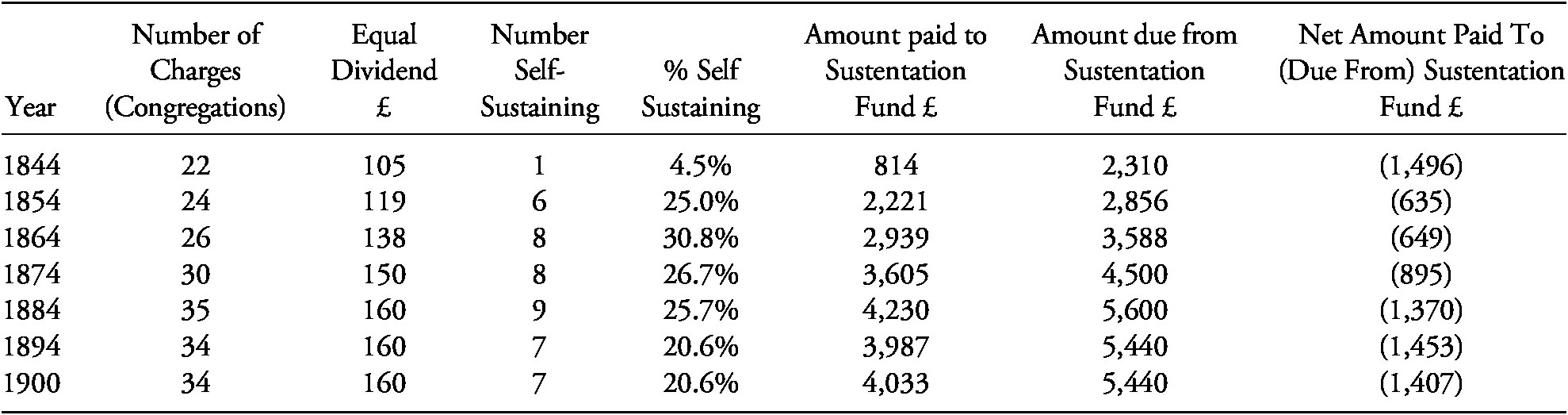

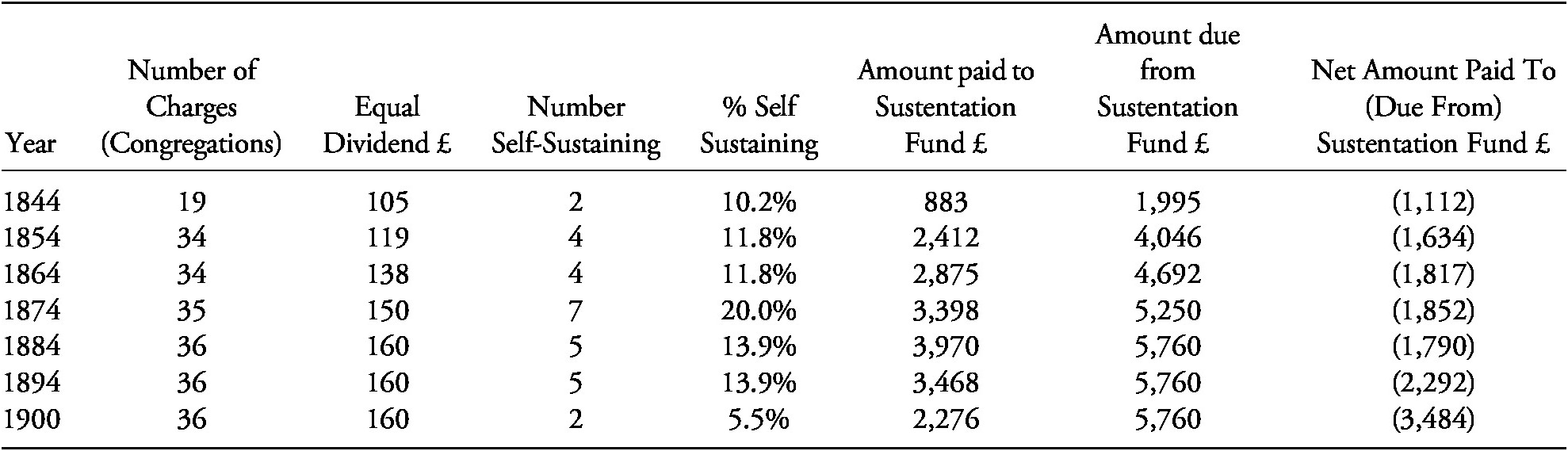

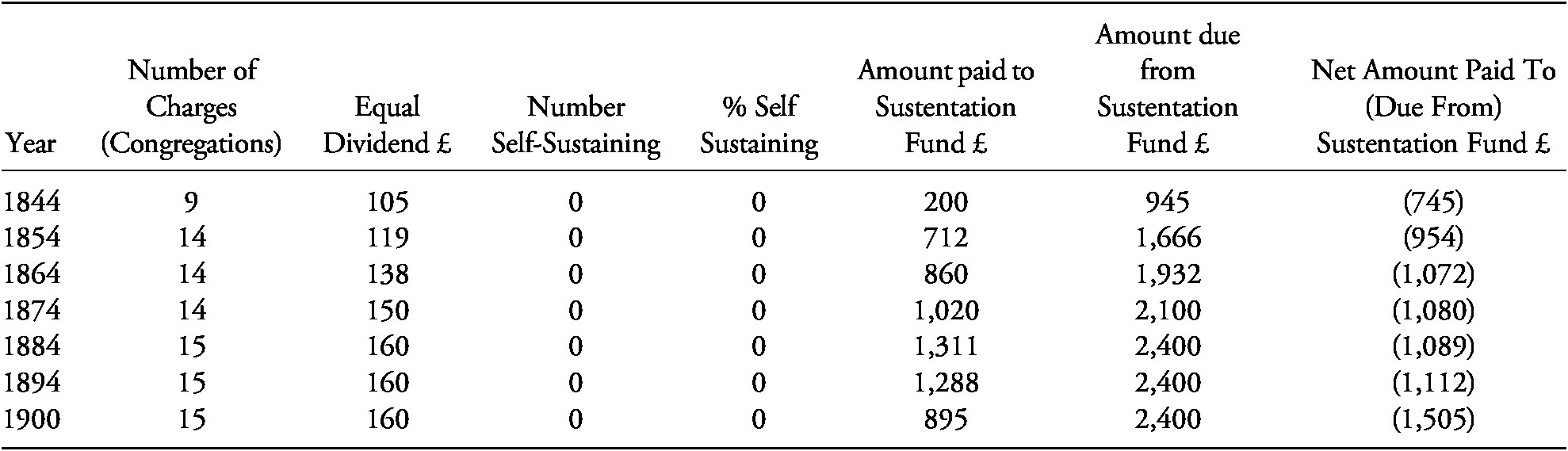

Focusing more closely on the question of the quantum of cross subsidy flowing to peripheral rural areas, Tables 6, 7 and 8 analyse the number and percentage of self-sustaining congregations on a decennial basis for rural synods in Lowland (Dumfries), Highland (Sutherland and Caithness) and Islands (Orkney) areas, recording the amounts paid to, and due from, the Sustentation Fund for the ministers employed within these areas.

For Dumfries, the pattern is of a decline in drawings from the Sustentation Fund, and greater financial self-sufficiency, in the first half of the century; followed by an increase in drawings, a reduction in financial self-sufficiency, and a growing reliance on the Fund during the final quarter century. For Sutherland and Caithness, with a similar number of congregations, the percentage self-sustaining is substantially lower, ranging from 20.0% in 1874 to just 5.5% in 1900. The net amount drawn down from the Sustentation Fund rises markedly in the later years reaching nearly £3,500 in 1900. In the case of Orkney, no congregation is recorded as self-sustaining in the sampled years. Whilst the number of churches in this synod is small, the net amount drawn from the Sustentation Fund rises across time to £1,505 in 1900, representing a doubling in the level of financial support between 1844 and 1900.

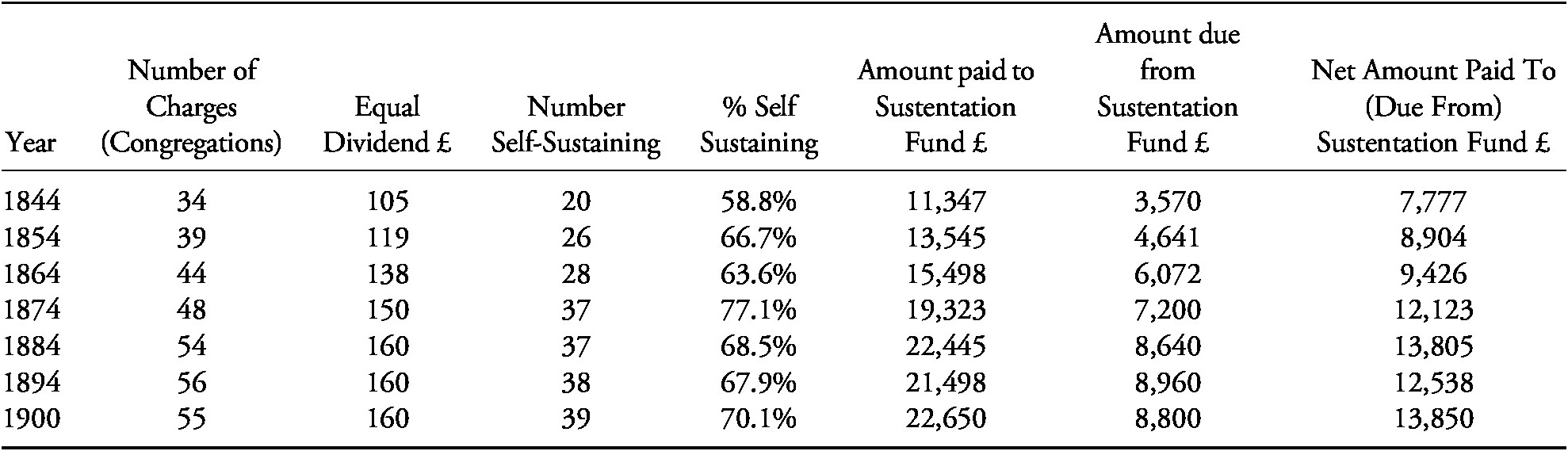

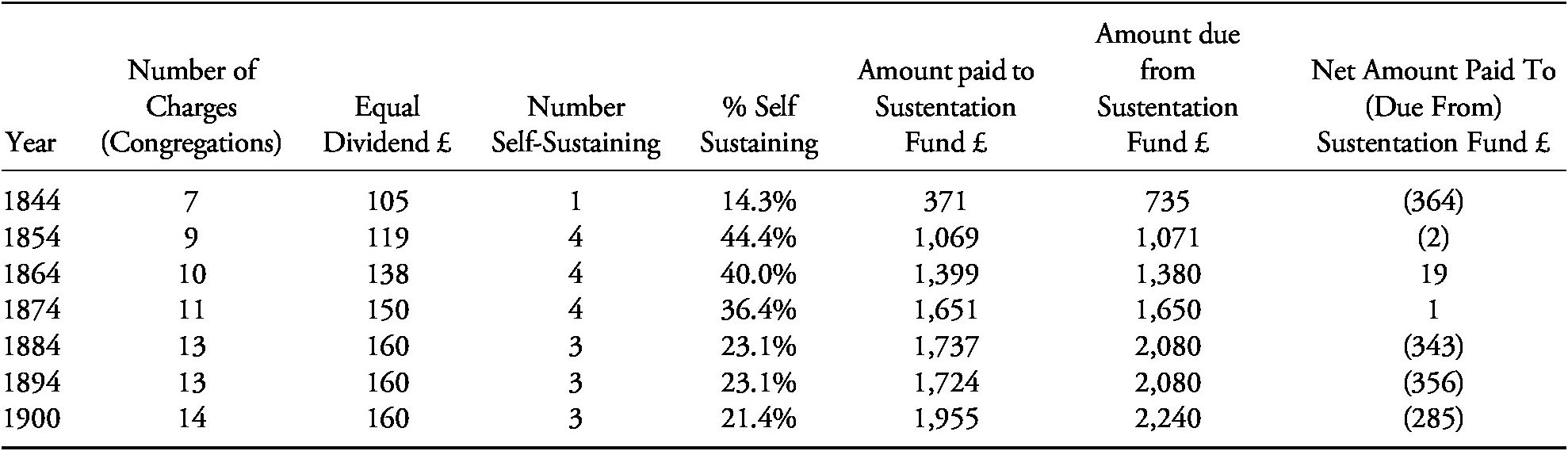

Looking at the quantum of cross subsidy flowing from urban areas, illustrative data relating to two urban presbyteries, one Lowland (Edinburgh) and one Highland (Inverness) are presented in Tables 9 and 10. For Edinburgh, the proportion of self-sustaining congregations is consistently between three-fifths and three-quarters, with net contributions to the Fund rising across time to reach £13,850 in 1900. In contrast, Inverness, a smaller and less prosperous urban area with a smaller number of congregations, has just one self-sustaining congregation (out of seven) in 1844, and three (out of fourteen) in 1900. In terms of the Sustentation Fund, the presbytery drew a modest amount in the early years, moving to a break-even position in 1864 and 1874, before falling back into modest deficit from 1884 onwards. The pre-eminence of the presbytery of Edinburgh in supporting the Sustentation Fund is clear.

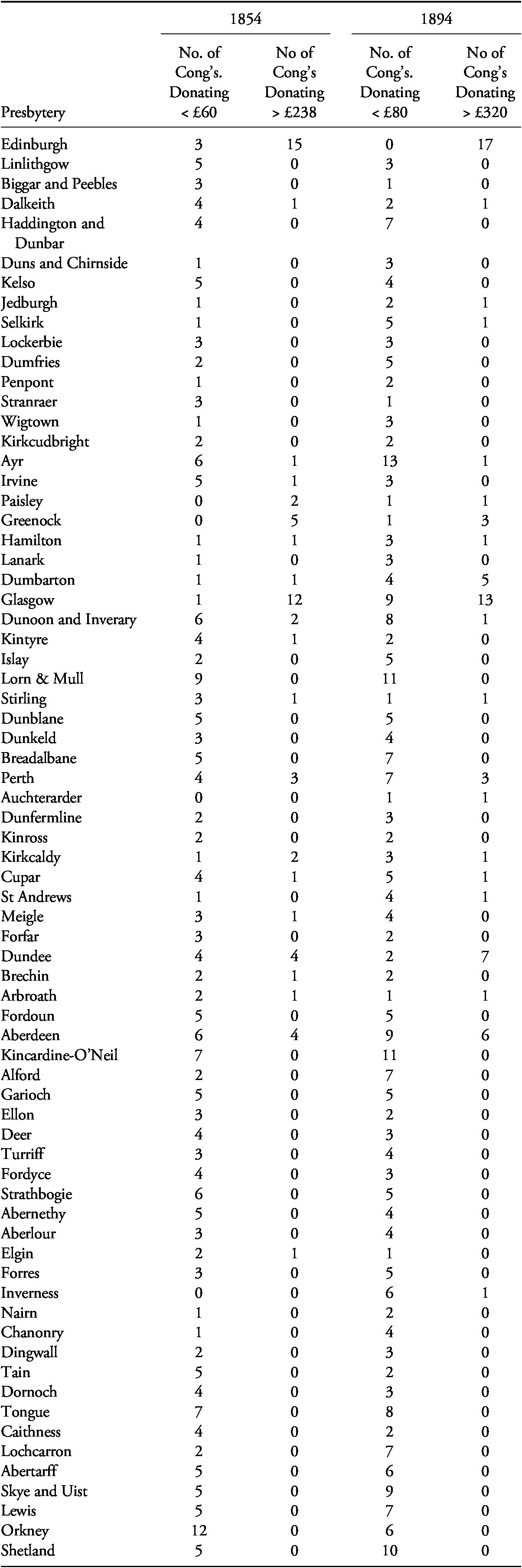

A final piece of analysis, illustrating the relative contributions of urban and rural areas, and the geographical location of the church’s leading net contributor congregations, is presented in Table 11. This summarizes the number of congregations in each presbytery contributing less than half, and more than double, the equal dividend set in the years 1854 and 1894. The data illustrate the geographical contours of cross subsidy, with the number of congregations donating less than half the equal dividend in both years being higher, in relative and absolute terms, in the rural areas; whilst those donating more than double the equal dividend being confined almost exclusively to those presbyteries within which was located a large urban conurbation or county town.Footnote 47 The table also illustrates the impact of urbanization and rising prosperity on giving in the case of the presbytery of Dumbarton, where rapid industrial growth across the period led to a sharp rise in the number of congregations contributing generously to the Fund.Footnote 48

Conclusion

The Free Church’s Sustentation Fund, throughout the period of its operation, displayed all the characteristics of an archetypal cross-subsidy scheme. Designed as a means by which financial resources could be transferred across the church in order to support payment of a basic stipend (the ‘Equal Dividend’) for all ministers, it achieved its overall aim of redistributing money raised by congregations located in wealthier urban areas to the poorer congregations located in peripheral mainland rural and island locations, on a scale hitherto unmatched amongst ecclesiastical institutions. It thereby enabled the Free Church to sustain its ministry across the whole country. In its operation, however, it displayed an openness to ‘free-riding’ by less generous congregations, and, latterly, aid fatigue on the part of the largest net contributors, creating difficulty for those maintaining the system of transfer between churches located in prosperous urban centres and those in the poorer rural periphery.

Evidence from the church’s financial records establishes that around two-thirds of congregations located in peripheral rural areas were cross subsidized by the Fund throughout the period of study; a proportion little changed by occasional adaptations to its rules of operation. Clerical support for the equal dividend principle thwarted both the early attempt by Chalmers to sharpen the economic incentives faced by the congregations of ministers newly admitted to the Fund, and successive attempts by the Sustentation Fund Committee to set binding fundraising targets for individual congregations.

Analyses of financial information relating to typical urban, rural and islands synods and presbyteries offer a preliminary calibration of the extent to which congregations in the peripheral rural areas remained dependent on the annual stipendiary cross subsidy received from the Sustentation Fund, with the poorer islands areas making the smallest contributions and securing the highest levels of support. However, disaggregating the results down to presbytery and congregational level reveals the extent which, within the overall aggregate flows, important counter-narratives are observed. Thus, whilst there was a general flow of funds from south to north, and urban to rural, there were large areas of rural Lowland Scotland, and large numbers of urban parishes in every city and town benefitting from the Sustentation Fund.

Had Chalmers not established the Sustentation Fund apparatus as a means of redirecting the surpluses generated in a relatively small number of its urban congregations, the national aspirations of the emergent Free Church would have been thwarted. This therefore offers a lens through which to observe the Free Church wrestling with its heritage and conscience throughout the nineteenth century. On the one hand, the church, committed by its founder to the establishment principle, set out to offer the ordinances of religion to the entire Scottish population, making good on this pledge by funding ministers and buildings across the country in short order. On the other hand, it found itself forced by circumstances to operate as a de facto voluntary, continuing to devote time, financial and human resources, into raising money sufficient to fund its activities from its wealthier members,Footnote 49 never raising enough to fully endow its activities in order to liberate it from the annual fundraising round.

The Sustentation Fund itself was an important part of the Free Church’s financial legacy which it took into the United Free Church following merger with the United Presbyterian Church in 1900. It was, however, a legacy which left unresolved the incentive problems typical of cross-subsidy schemes. These problems, intrinsic to the design and operation of the Sustentation Fund, would first undermine, and ultimately inhibit, the attempts of the new church to increase the number and proportion of financially self-sustaining congregations,Footnote 50 with implications for its own development in the early twentieth century. The findings therefore give new insight into the financial development of both the Free and United Free churches, against which narratives relating to the established church’s revival may be set.

With hindsight, the predictions of Chalmers on the dire consequences to the church of extending the benefits of the equal dividend beyond ministers who left the Church of Scotland in 1843 look overstated. However, his predictions relating to the long-run behaviour of aid-giving and aid-receiving congregations under a cross-subsidy arrangement were surely validated: ‘The equal divided, carried out and persisted in, will not only operate, which it has already done, to a fearful extent, as a sedative on the efforts of the aid-receiving, but as a sedative too, and that right soon, on the liberalities of the aid-giving congregations.’Footnote 51

APPENDIX

Table 1. Sustentation Fund: Contributions, Ministers Participating and Equal Dividend: 1843/4 to 1898/9

Source: Free Church of Scotland, Financial Report of the Sustentation Fund Committee for the Year Ending 15th May 1900 (Edinburgh, 1900).

Notes: Year convention: 1844 relates to year May 1843 – May 1844 etc.

Census month May.

Table 2. Self-Sustaining Congregations: Scotland

Sources: Free Church of Scotland, Abstract Shewing the State of the Associations for The Year Ending 15th May 1846 as Compared with The Year Ending 15th May 1845 (Edinburgh, 1846); Free Church of Scotland, (Supplement to) The Home and Foreign Record, Extract from Public Accounts (Annual); Free Church of Scotland, Report on the Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland (Annual); Free Church of Scotland, (Financial) Report of the Sustentation Fund Committee (Annual; 1867–1900).

Notes: Year convention: 1844 relates to year ending May 1844 etc.

‘Self-Sustaining’ is defined as remitting to the Sustentation Fund an amount greater than, or equal to, the equal dividend.

Number of charges excludes preaching stations.

Data reported annually on a consistent basis from 1867 to 1900.

Table 3. Ranked Contributions to the Sustentation Fund by Synod

Source: Free Church of Scotland, Abstract (Report) of (on) the Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland (Annual).

Notes: 1844 – year to 31st March 1844.

Census month March.

Expressed in full pounds (£).

Table 4. City Contributions

Source: As Table 3.

Note: Four city presbyteries – Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dundee, Aberdeen.

Expressed in full pounds (£).

Table 5. Largest Congregational Contribution to the Sustentation Fund by Presbytery

Sources: Free Church of Scotland, Abstract of the Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland for the Period from May 18, 1843 to March 30, 1844 (Edinburgh, 1844); Free Church of Scotland, Eleventh Report on the Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland for the Year Ended 30th March 1854 (Edinburgh, 1854); Free Church of Scotland, Twenty-First Report on the Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland for the Year Ended 30th March 1864 (Edinburgh, 1864); Free Church of Scotland, Thirty-First Report on The Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland for the Year Ended 31st March 1874 (Edinburgh, 1874); Free Church of Scotland, Forty-First Report on the Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland for the Year Ended 31st March 1884 (Edinburgh, 1884); Free Church of Scotland, Fifty-First Report on The Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland for the Year Ended 31st March 1894 (Edinburgh, 1894).

Note: Census month March.

Table 6. Self Sustaining Congregations: Lowland Rural Synod of Dumfries

Sources: Free Church of Scotland, Report on the Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland (Annual).

Notes: The southern synod of Dumfries comprised three presbyteries: Dumfries, Lockerbie and Penpont.

Preaching stations excluded from total number of charges.

Expressed in full pounds (£).

Figures for 1844 exclude those congregations which made no contribution to the Sustentation Fund.

Amount due from Sustentation Fund calculated as (number of congregations) x (equal dividend).

Table 7. Self-Sustaining Congregations: Highland Rural Synod of Sutherland and Caithness

Table 8. Self-Sustaining Congregations: Islands Rural Synod of Orkney

Table 9. Self-Sustaining Congregations: Lowland Urban Presbytery of Edinburgh

Table 10. Self-Sustaining Congregations: Highland Urban Presbytery of Inverness

Table 11. Number of Congregations by Presbytery Contributing Less Than Half, and More Than Double the Equal Dividend in 1854

Sources: Free Church of Scotland, Eleventh Report on the Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland for the Year Ended 30th March 1854 (Edinburgh, 1854); Free Church of Scotland, Fifty-First Report on The Public Accounts of the Free Church of Scotland for the Year Ended 31st March 1894 (Edinburgh, 1894).

Notes: Excludes Preaching Stations

1854 Equal Dividend = £119

Thresholds: Half <£60 : Double > £238

1894 Equal Dividend = £160

Thresholds: Half <£80 : Double > £320.