Introduction

Bipolar disorder is characterized by manic episodes with or without depressive recurrences, resulting in heterogeneous presentations and an unpredictable course.Reference Bartoli, Nasti and Palpella1, Reference Bartoli, Malhi and Carrà2 It is associated with poor psychosocial functioning and reduced life expectancy.Reference McIntyre, Berk and Brietzke3 While several genetic and environmental risk factors for bipolar disorder have been suggested,Reference Rowland and Marwaha4 the etiopathogenetic mechanisms of this disorder remain unknown. Prodromal conditions, such as anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and behavioral disorders, often precede the development of bipolar disorder—potentially allowing anticipation of the illness, though with questionable sensitivity and specificity.Reference Bartoli, Callovini and Cavaleri5 However, the focus of research has been redirected to substance use,Reference Bach, Cardoso and Moreira6 as comorbidity with bipolar disorders is high in both hospital- and community-based samples.Reference Hunt, Malhi and Cleary7 For instance, in a recent study that examined the Norwegian Patient Registry, data revealed that the cumulative transition rate from substance-induced psychosis to bipolar disorder was 4.5% (95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 3.6%–5.5%).Reference Rognli, Heiberg and Jacobsen8

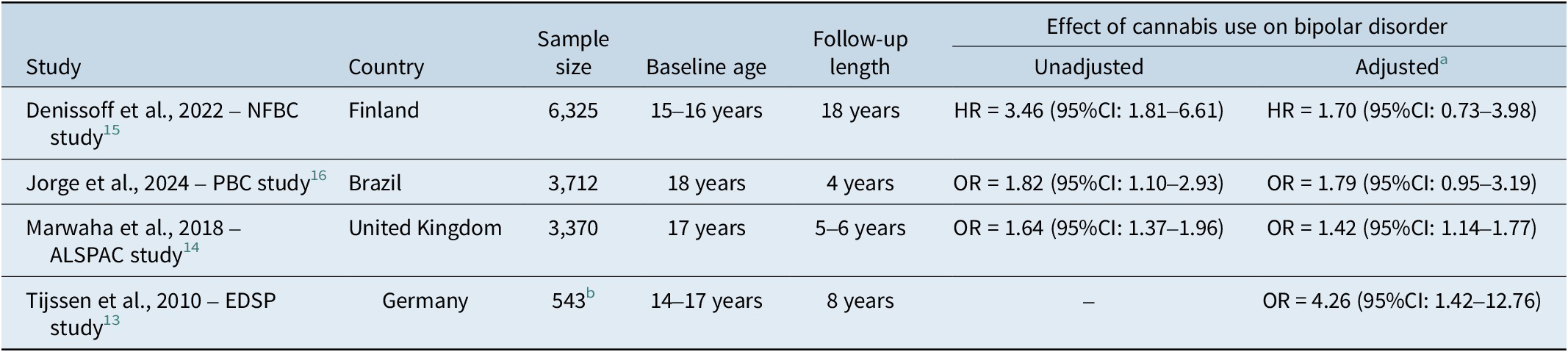

In recent years, a significant proportion of evidence aimed at clarifying the association between cannabis use and bipolar disorder has been published.Reference Gibbs, Winsper and Marwaha9, Reference Pinto, Medeiros and Santana da Rosa10 Meta-analytic data have shown that the use of cannabis is frequent in people with bipolar disorder, involving up to a quarter of patients.Reference Pinto, Medeiros and Santana da Rosa10 Cannabis use has been associated with a younger age, male gender, an earlier onset of affective symptoms, psychotic features, and suicide attempts.Reference Pinto, Medeiros and Santana da Rosa10, Reference Bartoli, Crocamo and Carrà11 Moreover, recent population-based data have shown that cannabis use disorder in both men and women might be associated with either psychotic or nonpsychotic bipolar disorders.Reference Jefsen, Erlangsen and Nordentoft12 Nonetheless, the efforts of epidemiological research have mainly focused on the investigation of early cannabis use as a risk factor for the subsequent onset of bipolar disorder. Specifically, four longitudinal studies have examined whether cannabis use during adolescence might predict the onset of bipolar disorder or manic/hypomanic symptoms: the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology (EDSP) study,Reference Tijssen, Van Os and Wittchen13 the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC),Reference Marwaha, Winsper and Bebbington14 the Northern Finland Birth Cohort (NFBC) studyReference Denissoff, Mustonen and Alakokkare15, and, more recently, the Pelotas Birth Cohort (PBC) study.Reference Jorge, Montezano and de Aguiar16 The main study characteristics of these investigations are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Longitudinal Studies Exploring the Association between Cannabis Use during Adolescence on the Onset of Bipolar Disorder

Abbreviations: 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; EDSP, Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology; HR, hazard ratio; NFBC, Northern Finland Birth Cohort; OR, odds ratio; PBC, Pelotas Birth Cohort.

a If more than one model was shown, the most comprehensive one was reported.

b Subset of subjects without manic symptoms at baseline.

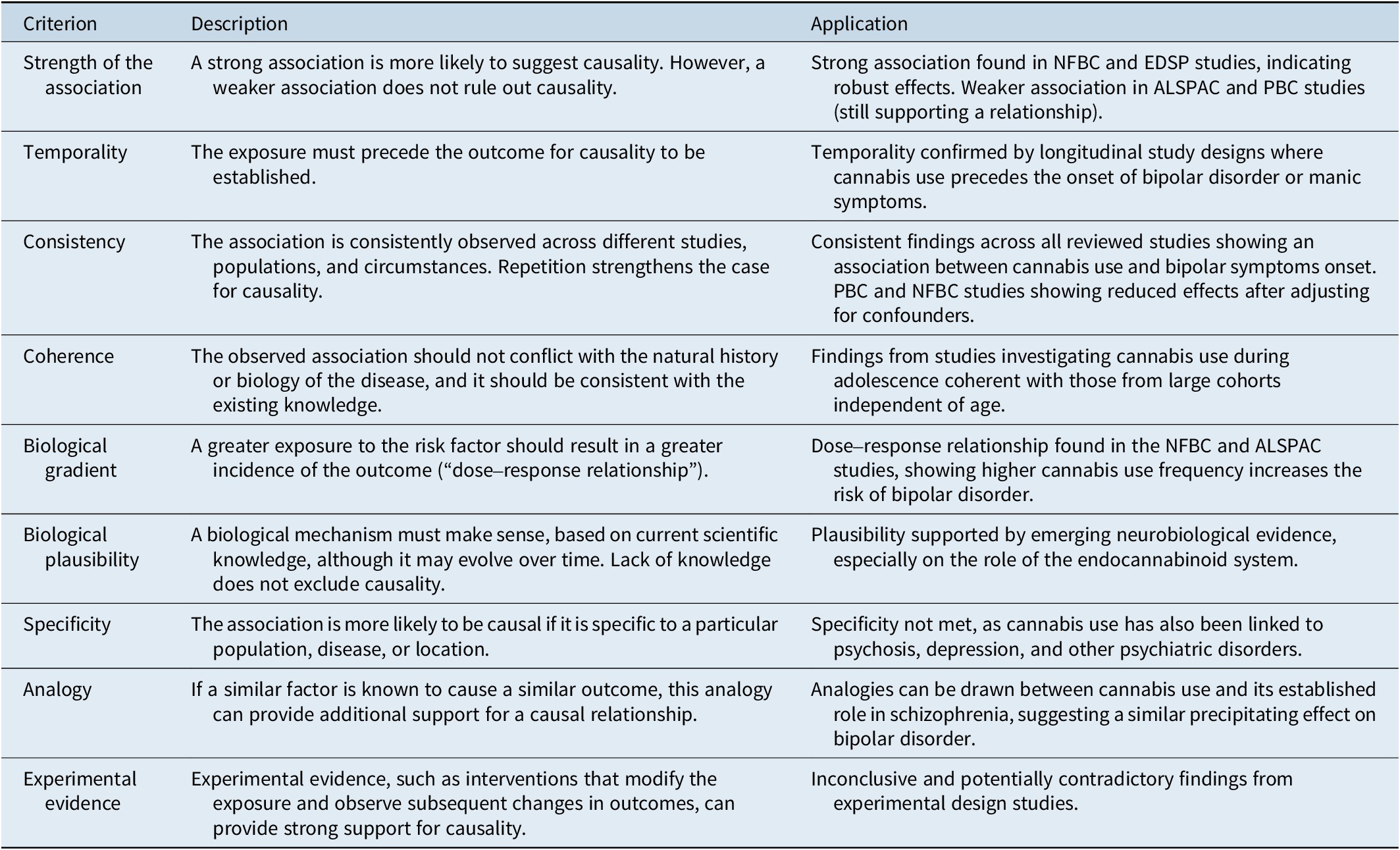

Although their methodological heterogeneity precludes any formal meta-analytic attempt, some useful insights can be drawn by considering the evidence collectively and comparing the outcomes to the requirements of the 9 Bradford Hill criteria. Reference Hill17 Upon interrogating these data to understand better whether early cannabis use is a risk factor for bipolar disorder, we surmise that the following inferences can perhaps be drawn (Table 2).

Table 2. Application of Bradford Hill Criteria to Evidence on Cannabis Use during Adolescence and Onset of Bipolar Disorder

Abbreviations: ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and ChildrenReference Marwaha, Winsper and Bebbington14; EDSP, Early Developmental Stages of PsychopathologyReference Tijssen, Van Os and Wittchen13; NFBC, Northern Finland Birth CohortReference Denissoff, Mustonen and Alakokkare15; PBC, Pelotas Birth Cohort.Reference Jorge, Montezano and de Aguiar16

Adolescent cannabis use and bipolar disorder onset: evaluating the evidence with the Bradford Hill criteria

In terms of strength of the association, large effects were found in 2 studies: the NFBC studyReference Denissoff, Mustonen and Alakokkare15 showed that adolescents who used cannabis had a hazard ratio (HR) for bipolar disorder of 3.46 (95%CI: 1.81–6.61), while the EDSP studyReference Tijssen, Van Os and Wittchen13 estimated a large effect for the onset of manic symptoms (odds ratio [OR] = 4.26; 95%CI: 1.42–12.76) among people who used cannabis at ages 14–17 years. Nonetheless, other studies showed more precise associations albeit they are weaker. The ALSPAC studyReference Marwaha, Winsper and Bebbington14 found that people who used cannabis at 17 years had an OR of 1.64 (95%CI: 1.37–1.96) for hypomania symptoms at 22–23 years. Similarly, the PBC studyReference Jorge, Montezano and de Aguiar16 showed a small association between cannabis use at 18 years and a diagnosis of bipolar disorder at 22 years (OR = 1.82; 95%CI: 1.10–2.93). Methodological differences in study design, the selected at-risk population, and potentially biased post hoc analyses, likely contribute to variations in the strength of the association. This holds true, especially considering that studies with longer follow-up duration possibly capture a broader range of developmental trajectories and transitions with varying time-dependent effects.

Second, temporality—probably the most essential criterion for causal inferenceReference Fedak, Bernal and Capshaw18—seems highly likely by the longitudinal design of the studies considered, as well as by the explicit exclusion of adolescents who may just be suffering from bipolar disorder at baseline. In particular, the EDSP study included only a subset of adolescents without manic symptoms,Reference Tijssen, Van Os and Wittchen13 while the PBC and NFBC studies explicitly excluded people with either bipolar disorderReference Jorge, Montezano and de Aguiar16 or even any mental disorderReference Denissoff, Mustonen and Alakokkare15 at baseline. Thus, the approaches used in these studies allowed the investigation of a relationship in which cannabis use clearly predated the onset of bipolar disorder/manic symptoms.

Third, the consistency criterion is supported by the evidence emerging from all these studiesReference Tijssen, Van Os and Wittchen13-Reference Jorge, Montezano and de Aguiar16 that cannabis use during adolescence was associated with the subsequent onset of manic symptoms. However, there were some variations in findings across studies when confounders were accounted for. While these factors did not influence the findings of the ALSPACReference Marwaha, Winsper and Bebbington14 and EDSP studies,Reference Tijssen, Van Os and Wittchen13 the PBC studyReference Jorge, Montezano and de Aguiar16 did not show any statistically significant effect of cannabis use on the incidence of bipolar disorder after adjusting for available variables, including lifetime cocaine use (OR = 1.79; 95%CI: 0.95–3.19). In addition, the most comprehensive model from the NFBC study,Reference Denissoff, Mustonen and Alakokkare15 similarly accounting for other illicit substance use, along with sex, family structure, parental mental disorders, and other clinical variables, did not support the association between baseline cannabis use and subsequent bipolar disorder (HR = 1.70; 95%CI: 0.73–3.98). These findings suggest that the effect of cannabis on bipolar disorder might be impacted by the use of other illicit substances, although the mechanisms of this remain obscure.

In addition, the coherence criterion can be considered sufficiently satisfied, as current knowledge in the field does not provide any elements to hypothesize that the causative role of early cannabis use might seriously “conflict with the generally known facts on the natural history and biology”Reference Hill17 of bipolar disorder. Indeed, findings from studies investigating cannabis use during adolescence consistently converge with those from large cohorts, testing the effects of cannabis use on the risk of bipolar disorder in the general population, independent of age. For instance, recent data from the Danish nationwide registers, accounting for a total of 6,651,765 individuals and 119,526,786 person-years, found that cannabis use disorder was associated with bipolar disorder in both men and women.Reference Jefsen, Erlangsen and Nordentoft12 Moreover, previous studies, based on the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study, showed that baseline cannabis use predicted both bipolar disorder and manic symptoms at follow-up, regardless of relevant confounders.Reference Henquet, Krabbendam and de Graaf19, Reference Van Laar, Van Dorsselaer and Monshouwer20 Moreover, coherence is supported by the theoretical framework of developmental models for bipolar disorder.Reference Colic, Sankar and Goldman21 Cannabis exposure during adolescence may induce long-lasting changes to the structure and function of brain areas, such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus,Reference Rodrigues, Marques and Cannabis22 which may be involved in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder.Reference Colic, Sankar and Goldman21

Another important criterion involves the biological gradient. Both the ALSPAC studyReference Marwaha, Winsper and Bebbington14 and the NFBC studyReference Denissoff, Mustonen and Alakokkare15 investigated the dose–response relationship between cannabis use and bipolar disorder. The ALSPAC studyReference Marwaha, Winsper and Bebbington14 found that the risk of hypomania symptoms was significantly higher in adolescents who used cannabis 2–3 times weekly, compared with those with less frequent or no cannabis use (OR = 2.80; 95%CI: 2.02–3.88). In addition, and more specifically, the NFBC studyReference Denissoff, Mustonen and Alakokkare15 found a dose–response relationship between the frequency of cannabis use and the onset of bipolar disorder, with an increasing risk from an HR of 3.03 (95%CI: 1.44–6.36) among adolescents using cannabis 1–4 times to an HR of 5.55 (95%CI: 1.74–17.73) in those who had used it 5 times or more in their lifetime.

On top of this, there appears to be sufficient biological plausibility to support the association between cannabis use and bipolar disorder, given that “what is biologically plausible depends upon the biological knowledge of the day.”Reference Hill17 Indeed, although the relevant neurobiological mechanisms are not entirely understood, it has been recently shown that several potential mechanisms—involving, among others, brain development, mitochondrial activity, inflammatory-related pathways, and the endocannabinoid system—may underlie this relationship.Reference Delgado-Sequera, Garcia-Mompo and Gonzalez-Pinto23 Among them, the putative role of the endocannabinoid system in bipolar disorder has been recently explored. Indeed, this system and its signaling pathways have emerged to be crucial in the regulation of mood and emotions.Reference Arjmand, Behzadi and Kohlmeier24 In particular, it has been suggested that the cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2) might play a key role in the mood dysregulations associated with bipolar disorder.Reference Arjmand, Behzadi and Kohlmeier24

However, the specificity criterion for the relationship between early cannabis use and bipolar disorder is not satisfied, as cannabis use is well known to induce or exacerbate psychotic disorders, with a dose–response relationship.Reference Marconi, Di Forti and Lewis25 In addition, it may correlate with depression, according to findings from both large population studiesReference Carrà, Bartoli and Crocamo26 and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies.Reference Lev-Ran, Roerecke and Le Foll27 Moreover, community-based data showed that not only cannabis but also tobacco, cocaine/crack, and other illicit substances may play a role in the incidence of bipolar disorder.Reference Bach, Cardoso and Moreira6 Nonetheless, the specificity criterion generally has poor validity and is more useful for supporting causation, rather than ruling it out.Reference Van Reekum, Streiner and Conn28

Although it is often ignored or wrongly equated to biological plausibility or coherence,Reference Weed29 analogy represents an additional criterion to test causation. The analogy criterion supports the concept that the likelihood of a causal relationship may be strengthened if comparable associations are observed between a similar outcome and a similar exposure.Reference Shimonovich, Pearce and Thomson30 For instance, even if bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are different and separate clinical entities, these disorders may share some environmental risk factorsReference Robinson, Ploner and Leone31 in a complex multicausal model of vulnerability.Reference Hamilton32 Considering older, paradigmatic cohort studies investigating cannabis use as a risk factor for schizophrenia,Reference Andréasson, Engström and Allebeck33-Reference Van Os35 we can perhaps speculate that something analogous might occur regarding the interplay between cannabis use (as a precipitating/facilitating agent) and the development of bipolar disorder.

Finally, the experimental evidence criterion is hard to meet, as it is unavailable in most epidemiologic circumstances.Reference Rothman, Greenland, Armitage and Colton36 Further, studies on human brain dysfunctions are complex, and those in nonhuman species may be misleading, making it a useful but not necessarily mandatory criterion in the mental health field.Reference Van Reekum, Streiner and Conn28 Neuroimaging studies on adolescents with bipolar disorder revealed possible effects of cannabis use in frontal and parietal regions,Reference Sultan, Kennedy and Fiksenbaum37 as well as in brain regions involved in emotional processing.Reference Bitter, Adler and Eliassen38 However, these findings are inconclusive to date, considering that other studies showed limited brain structural changes associated with cannabis use in people with severe mental illness, including bipolar disorder.Reference Hartberg, Lange and Lagerberg39 Moreover, when testing the possible bidirectional relationship between bipolar disorder and cannabis use, data from experimental studies seem to contradict findings from large epidemiological data. For instance, a 2-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study supported a causal effect of bipolar disorder on the risk of using cannabis at least once, but no causal effect per se regarding the liability of cannabis use to cause bipolar disorder.Reference Jefsen, Speed and Speed40

Conclusion

Although the Bradford Hill criteria are not intended as a rigid checklist for testing causation, but rather as a flexible guideline that may favor the interpretation of evidence,Reference Fedak, Bernal and Capshaw18 it seems there are sufficient, appropriate elements to support the hypothesis that cannabis use during adolescence may play a causal role on the subsequent risk of developing bipolar disorder. Following this approach, given that detailed, time-varying information is incorporated, the causal relationship between early cannabis use and bipolar disorder is likely to be strong, coherent, plausible, and based on a clear temporality. However, it seems to be only partially consistent and nonspecific. This may be due to residual confounding, particularly related to polysubstance use, family history, or sociodemographic factors. Although the reviewed studies accounted for several relevant covariates, the influence of unmeasured confounders cannot be ruled out and may explain some of the inconsistencies. While the experimental evidence is far from being conclusive, the biological gradient is supported by the dose–response relationship between the exposure severity and outcome. In addition, some analogies with the more robust body of evidence on schizophrenia suggest a role for cannabis also in the onset of bipolar disorder, likely to be based on a multicausal theory of the disease.Reference Broadbent41

Additional, adequately powered, longitudinal evidence is needed to explicitly model the causes (early cannabis use) of change (later onset of bipolar disorder) over time.Reference Kenny, Everitt and Howell42 Finally, research in this field may take advantage of “natural experiments” resulting from changes in cannabis policies, by comparing pre- and post-legalization cannabis use patterns and related outcomes in the general population.Reference Doggett, Belisario and McDonald43 In particular, our understanding could benefit from investigating the potential impact of medical or recreational cannabis legalization on bipolar disorder rates,Reference Hammond, Chaney and Hendrickson44, Reference Ladegard and Bhatia45 as is the case for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.Reference Myran, Pugliese and Harrison46

Data availability statement

This article does not include any original data. All data referenced in this article are available in the cited published sources.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: all authors; Data curation: F.B., D.C., C.B., M.B., C.C.; Investigation: F.B., D.C., C.B., M.B.; Methodology: all authors; Project administration: F.B., G.S.M., G.C.; Supervision: G.S.M., G.C.; Writing—original draft: F.B., D.C.; Writing—review and editing: C.B., M.B., C.C., G.S.M., G.C.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosures

No author has financial or other competing interests relevant to the subject of this article.