How did colonial urbanism shape and reshape cross-communal encounters? Scholarship on the urban history of colonial Algeria has been long preoccupied with the city as the ‘concrete manifestation, the form which colonialism takes in an urban environment’, to quote David Prochaska.Footnote 1 Historians, anthropologists and architectural scholars have shown how cities such as Algiers, Oran or Bône were subjected to penetrative policies that sought to remodel them along the needs, norms and forms of the economic and societal order that was taking shape in Algeria. Much of this scholarship has also emphasized the ethno-religious categories along which colonial officials and urbanists sought to divide the city into old and new, native and European quarters.Footnote 2 Without a doubt, the onset of colonization in Algeria and the emergence of settler society reshaped much of the Algerian urban environment along European models. Yet, for all its magnitude and power, colonial rule did not put an end to the diversity of Algerian society and its long history of encounter and exchange across religious lines. As this article demonstrates, occupying, mapping, building and reconstructing the built environment in Algeria could never fully control the ways of living, moving and interacting in the city. Demographic developments, economic needs and the permanent tension between military and civilian rule in the colony meant that urban spaces were repeatedly reclaimed by local actors and used for purposes not foreseen by colonial planning, particularly outside the epicentres of French rule.

This article explores the emergence of Jewish–Muslim cohabitation in what may, at first glance, seem a most unlikely site: the modern town of Sétif, created by French authorities in the 1830s and designed as a ‘masterplan city’ to serve as a focal point of colonization in the Algerian east.Footnote 3 At first a garrison station, Sétif was declared to be a ‘European town’ in 1847, a clear counterweight to the historic, ‘Arab’ city of Constantine.Footnote 4 By the turn of the twentieth century, however, Sétif had become a town with a clear Algerian majority, one where different groups shared public, commercial and not least residential spaces, defying key legal and ethnographic categories of the colonial order.

The most intriguing site of cross-communal cohabitation to emerge in Sétif and defy French colonial urbanism is the one known today in Algeria as the hara (plural and genitive: harat): a building with dwellings for several households, secluded from the street and arranged around a shared, interior courtyard.Footnote 5 While different ethnic and religious groups shared streets and even apartment buildings in various Algerian cities, the harat are a particularly illuminating test case.Footnote 6 Originally built for low-income European residents, the harat became inhabited predominantly by Algerian Muslim and Jewish families in the inter-war period. With small private living spaces and shared communal facilities, the harat defied the main rationales of French colonial urbanism of the time: the attempt to implement in the Maghreb European notions of ‘modern’ family living in clearly marked and separated spaces, and the attempt to separate urban populations along ethno-religious categories.Footnote 7 The case of the harat, in other words, highlights the limited power of planners and administrators in shaping social realities even at the high noon of French colonial power.

At the same time, the harat allow us to explore the strong ambivalence of being neighbours in a colonial town. While Jewish and Muslim residents shared spaces, routines and to some extent language, their historical trajectories, legal statuses and occupational possibilities varied significantly. While the Algerian Jewish minority had possessed full French citizenship since 1870, the vast majority of the Algerian Muslim population was excluded from this status throughout the colonial period.Footnote 8 The two populations were subjected to different laws, duties and institutions; they arrived in the emerging town of Sétif under different circumstances, and from the 1940s onwards, their political outlooks diverged significantly.

The harat of Sétif were made famous by anthropologist Joelle Bahloul’s study La maison de mémoire (1992), combining oral interviews and the tools of anthropology to draw a portrait of Jewish–Muslim cohabitation in late colonial Algeria and the ways in which memory of a common past was constructed around a formerly shared home.Footnote 9 Bahloul’s book is a trove of testimonies by men and women who resided in a Sétifian hara at different points during the twentieth century. Alongside interviews with current residents of different harat conducted by the authors of this article in 2021, this corpus of oral history constitutes an important empirical base for this article. A second genre of sources for this article are plans, axonometric sketches and photographs of Sétifian harat created on site as part of the research. Finally, the article draws on maps, plans, photographs, building authorizations, newspapers and archival records from the colonial period. These different sources allow the article to explore Jewish–Muslim cohabitation in three methodological steps: reconstructing the production of the colonial urban space of Sétif; tracing the different trajectories of the town’s Jewish and Muslim populations; and studying the spaces and routines of living together in the harat. By so doing, the article sheds light on the social, political and identitarian significance of urban proximity in colonial Algeria: a condition that fostered a local sense of solidarity across religious and legal lines in a political order grounded in ethno-religious and legal divisions.

By tracing the trajectories that brought Algerian Muslims and Jews to Sétif, we can situate their cohabitation within the broader history of migration and urbanism in the French colonial Maghreb – and the post-Ottoman Arab world more broadly. While Bahloul’s work aptly locates memories of Jewish–Muslim cohabitation in the passage from colonial to post-colonial times, it is by studying the urban space and the population of Sétif during the colonial period that we may identify the determining factors of this case. Unlike well-established urban hubs of the central Maghreb such as Algiers, Constantine or Tunis, Muslim and Jewish residents of Sétif did not have any shared pre-colonial history.Footnote 10 Here, the very social fact of Jews and Muslims being neighbours, not its unmaking as in the far more known case of British mandate Palestine, was a product of colonial rule.Footnote 11 The dynamics of upward legal and economic mobility translating into changing patterns of residence, which characterized ethno-religious minorities in various cities of the Ottoman and post-Ottoman Mediterranean, could not possibly be as marked in a new and small town like Sétif.

In an article from 2009, Zeynep Çelik described the ‘lingering obsession’ of French colonial discourse with penetrating the secluded, ‘traditional’ Algerian house – from Delacroix’s 1834 depiction of Algerian (Jewish) women in their dwelling through the construction of a model maison indigène designed for European visitors in Algiers in 1930 to photographs of French soldiers standing in the courtyard of historic Algerian houses during the Algerian War.Footnote 12 Çelik’s argument captures an important trope of the French colonial gaze, but it also draws our attention to the over-representation of the archetypical ‘Moorish’ house in colonial cultural production – and in research on the colonial period. The case of the Sétifian harat highlights what can be gained from engaging with more vernacular forms of claiming, designing and inhabiting the urban environment. It provides a test case that goes against the grain of official urbanism, one that allows us to recalibrate small, provincial towns in the history of being neighbours in colonial Algeria on the eve of the descent to violence which, as it were, began in Sétif in 1945. If we are to understand the ‘worlds of contact’ that had persisted between different groups during much of the colonial period and which were swiftly erased in the early 1940s, as Annie Rey-Goldzeiguer noted, the Sétifian harat are a most illuminating case.Footnote 13

Colonial Sétif: newness, smallness, remoteness

Jewish–Muslim cohabitation in modern Sétif was shaped by the town’s history of conquest and colonization in the high plateau of the Algerian east. While the location of Sétif had been the site of human settlement in the Roman and Byzantine eras, the modern town was a French creation. Thus, unlike well-established urban centres such as Oran, Algiers or Constantine, the Muslim and Jewish populations that emerged in Sétif from the 1840s onwards had no pre-colonial history of shared urban sociability on which they could draw. The spaces in which their lives and encounters took place were shaped by the interests and perceptions of French colonial generals, administrators and planners. Three main aspects of the town’s colonial character conditioned this history well into the mid-twentieth century: its newness, smallness and remoteness.

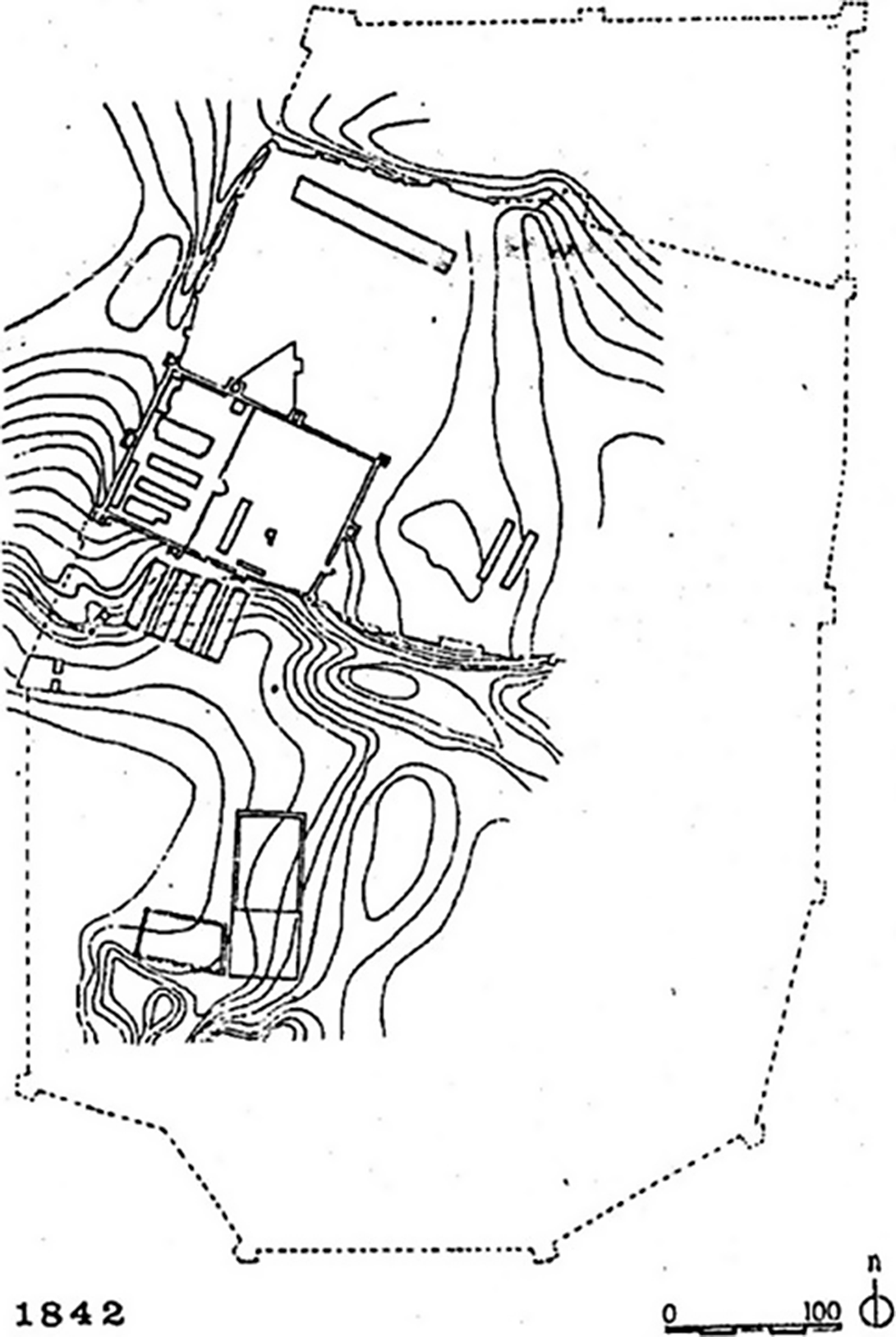

Sétif’s early development was the product of the military-archaeological complex that characterized the early phase of the French presence in Algeria – a recurring pattern in which conquests were followed by excavations.Footnote 14 The first military stronghold was founded on the Roman and Byzantine site discovered by French troops in December 1838 on their way westward from Constantine, a year after the capitulation of the Ottoman bey. Military officers described a Byzantine citadel still standing on the site, as well as a more recent granary.Footnote 15 These archaeological findings determined the perimeter of the first urban nucleus and the crossed north–south and east–west axis system of its layout (see Figures 1 and 2). The first permanent buildings were constructed in 1839. A year later, military forces began extending and solidifying the site, including, most notably, the construction of the Fort d’Orléans on top of the remains of the Byzantine fortress – a name chosen in honour of the French crown prince, the duc d’Orléans, who visited the region in October of that year.Footnote 16

Figure 1. The site of Sétif as mapped by French officers, 1842. The fortifications’ remains are marked by the dotted line.

Source: A. Picard-Malverti, ‘Lotissements et colonisation: Algérie, 1830–1870’, Villes en Parallèle, 14 (1989), 233.

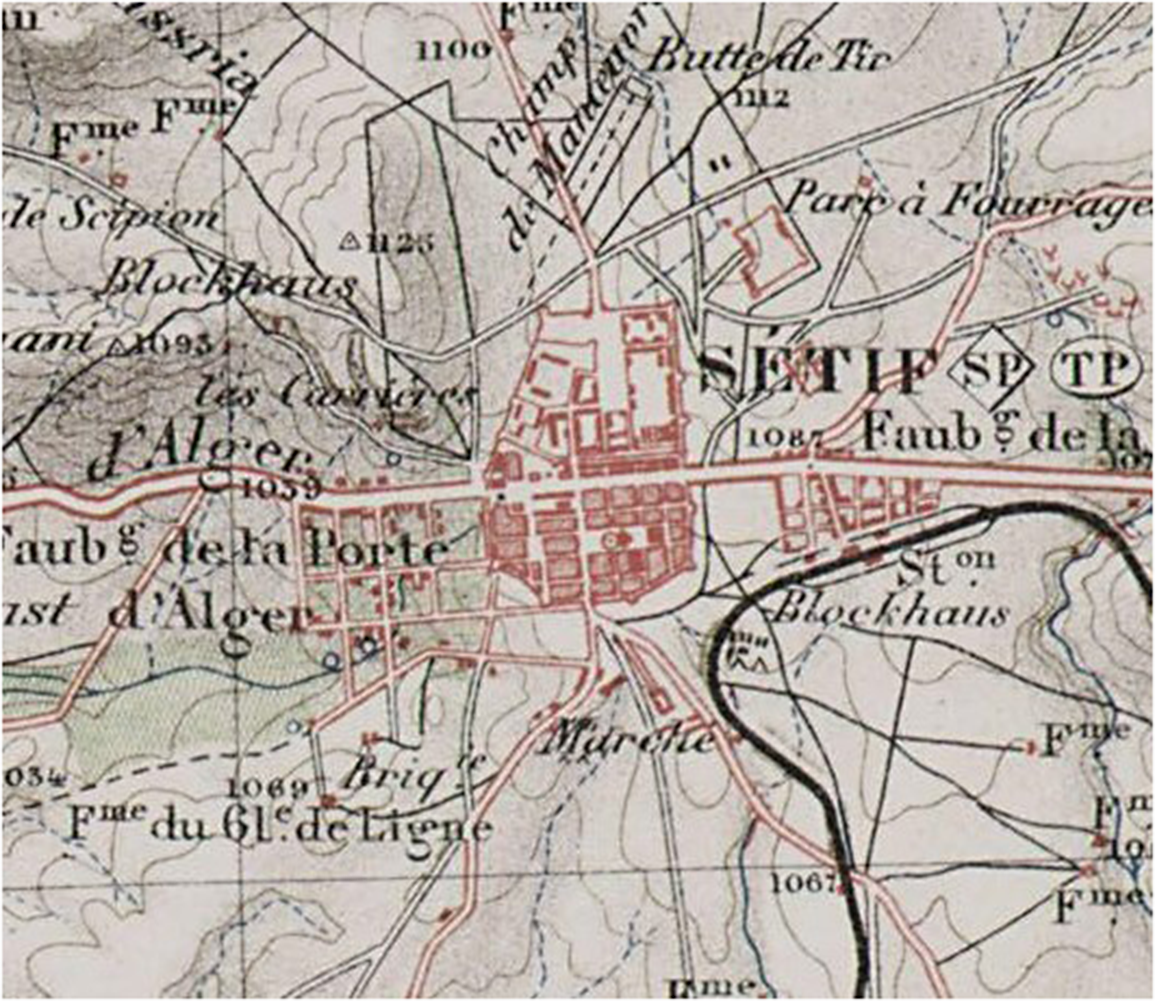

Figure 2. Sétif, 1893.

Source: ANOM, CP F80 2037/176: Département de Constantine, Sétif par le Service géographique de l’armée, 1893.

As elsewhere in the Algerian east, the emergence of Sétif as a civilian settlement went hand in hand with colonial warfare and the repression of insurrection. While some civilian dwellings and public works were recorded in 1842–43, urban development was hampered by persisting armed resistance. In late 1845, French generals feared that the troops of the charismatic rebel Bou Mazza, also known as Muhammad bin Abdallah, were reaching the environs of Sétif.Footnote 17 It was only after the repression of the insurrectionists and through the collective punishment means that followed that civilian Sétif emerged. The military camp was officially transformed into a town by a royal ordinance in 1847.Footnote 18 In 1849, various Algerian populations (tribus in French colonial jargon) between Sétif and the Mediterranean port town of Bejaia (Bougie) to its north were required to pay the French authorities war indemnities, which the Algerian governor sought to use for public works in the region, not least the road connecting Sétif and Bejaia, a goal that was highlighted as key to Sétif’s development by military engineers.Footnote 19

Once armed resistance was quelled, Sétif’s civilian population increased quickly. In 1850, its population was reported to include 606 Europeans, out of whom 440 were French, and 413 natives, out of whom 307 were Muslims, 8 enslaved black people and 98 Jews.Footnote 20 However, early estimations of the numbers of Jews and Muslims must be treated with caution, since French explorers were prone to mixing the two religious communities.Footnote 21 The non-French European population in the 1850s and 1860s included most probably Italians and Maltese, who outnumbered French nationals in the Constantine region in the first decades of colonization and whose percentage remained high throughout the nineteenth century.Footnote 22 By 1852, Sétif appears to have become somewhat known amongst the colons of the region, with requests to settle there submitted to military authorities.Footnote 23 From 1853 onwards, a significant number of settlers arrived from Switzerland, recruited and sponsored by a Geneva-based company. By the end of 1869, it had managed the settlement of 428 individuals.Footnote 24

The royal ordinance that established Sétif as a town in 1847 explicitly designated it as a ‘European town’, and the urban planning and public works in the following years did much to shape its character accordingly.Footnote 25 Together with other towns in the Algerian east – most notably Bône and Philippville – Sétif can be seen as a colonial endeavour to counter the ancient centre of Constantine, whose ‘type and character’ as an ‘Arab city’ Governor Bugeaud strove to preserve.Footnote 26 The construction and public works conducted in the 1840s to 1860s included some projects for the Algerian Muslim population – most notably a mosque and an ‘Arab market’ – but enhanced the overall character of a town planned along contemporary European ideas of the public sphere and the circulation of people, goods and information with civil facilities such as public clocks, telegraph communication and several municipal buildings.Footnote 27 A French traveller by the name of Anaïs du Tertre who arrived there in 1854 described Sétif with the following words:

Sétif isn’t an Arab town at all. It is situated in an area where the tribes live in tents and not in stone houses. It is a French town, hence completely new, but built on top of the Roman city of Sétifis…All the houses have or will have arcades like those in the rue de Rivoli [in Paris]…A public garden…has several abundant sources and is a pleasure for the residents of Sétif…At the heart of the town, most streets have houses built on both sides, but further away there are entire quarters where [only] lines of granite mark the future sidewalks on the grass. It is here that we find the marks for the future church of Sétif.Footnote 28

Like other towns and cities established or reshaped in the first two decades of French rule, Sétif was divided into a military and a civilian sector and was surrounded by walls.Footnote 29 It was later identified by French military engineers as one of the settlements fulfilling the conditions as a centre of the permanent colonization of Algeria: accessibility, security, availability of water supply and agricultural potential of the surroundings.Footnote 30 These ‘masterplan towns’ were planned along a recurring pattern: the crossed axes system of north–south and east–west, streets and roads following a clear pattern intended to allow for regular, uninterrupted movement and public buildings scattered throughout the town.Footnote 31 It was on the margins of this small, fortified urban nucleus (Figure 3) that the harat would emerge as sites of fragile Jewish–Muslim cohabitation in the early twentieth century.

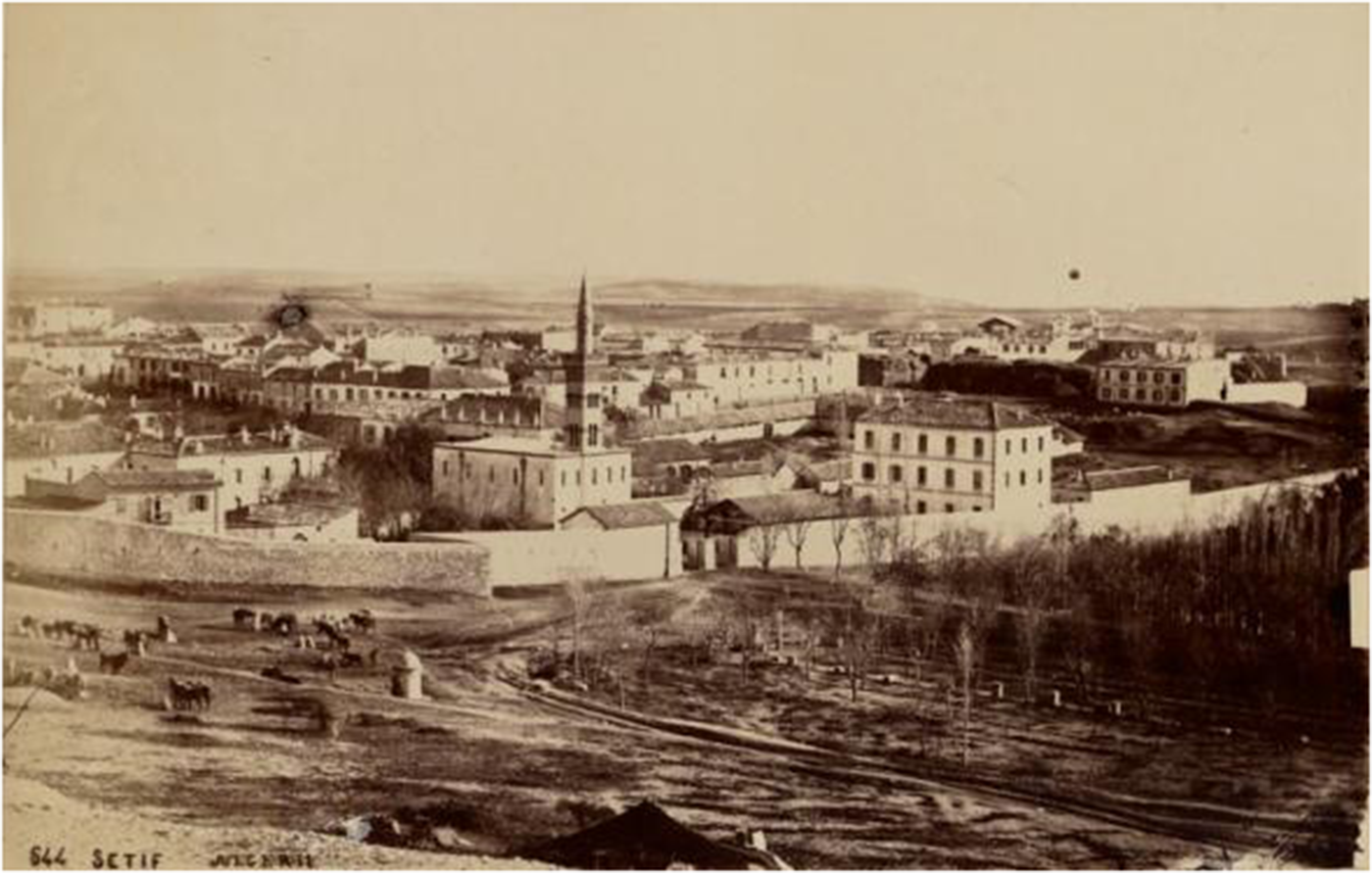

Figure 3. Sétif, 1860, view from south-east.

Source: ANOM, base ulysse.

As a newly built town, Sétif did not have a distinct Jewish or Muslim quarter. Individuals of different backgrounds and legal statuses encountered one another regularly in the small area of the town’s early nucleus. This was particularly marked in commercial areas such as the one near the covered market, where Jewish and Muslim merchants worked side by side.Footnote 32 Suburban neighbourhoods began to emerge only in the 1880s, after Sétif had been connected by train to Constantine and Algiers.Footnote 33 A map from 1893 shows this early phase of expansion, with small neighbourhoods to the east and west of the city centre (see Figure 2; the black line in the lower right-hand corner marks the railroad). Walls surrounded the city centre well into to twentieth century; it was only in 1931 that the way was paved for their demolition.Footnote 34

By the early twentieth century, Sétif featured three main housing types. The commercial thoroughfares in the early nucleus, especially the rue Constantine and rue Valée, were increasingly dominated by immeubles de rapport: multiple-storey buildings combining commerce on the ground floor and apartments for French families on the upper levels, built in the neo-classicist fashion of the time. Further towards the outskirts, one could find the maison coloniale: a house of no more than two storeys, intended for a single European family. The third type was what came to be known as the hara. These were two-storey buildings which were designed to house several households of low-income Europeans. They were built in the inner nucleus of the town, and still dominate it today. In a study from 2000, Messaoud Abbaoui and Nourredine Azizi counted 48 harat. Footnote 35 As Figures 4–5 show, the different housing types existed in immediate proximity to each other within the town’s early nucleus. It was in the harat that the most important demographic development in twentieth-century Sétif – the decline of the European population and the rise of a much intertwined Muslim and Jewish life – took its most interesting shape.

Figure 4. One-, two- and multiple-storey buildings on the rue Tarjan, photographed in the late nineteenth century.

Source: authors’ private postcard collection.

Figure 5. One-, two- and multiple-storey buildings on the rue Tarjan, photographed in the early twentieth century.

Source: authors’ private postcard collection.

Jews and Muslims in Sétif: proximity and difference

While Jews and Muslims shared the small urban space of Sétif, their histories in the town and their relations with it had been very different from early on – a divergence that reflected the different ways in which Jews and Muslims experienced French colonization and interacted with it. This constantly present tension between proximity and difference, between shared spaces and diverging socio-political conditions was a crucial element of being neighbours in Algeria; it was particularly marked in the small and new space of Sétif.

The origins of the Jewish population in modern Sétif (there had been some Jewish presence in the Roman site of Stifis) harked back to the French expedition in the Algerian east, when some Jews acted as auxiliaries and interpreters to the French forces – a relation that characterized certain segments of the Jewish minority and the French military from early on.Footnote 36 At least three cases of Jewish interpreters for the French military asking for permission to purchase land in Sétif in 1855–56 are recorded in the archives.Footnote 37 In her aforementioned travelogue from 1854, Anaïs du Tertre stated that Jews in the town were ‘very numerous and rich’, a statement which does seem to reflect a strong Jewish presence, even if we factor in European prejudices regarding Jews.Footnote 38 By 1867, there was already a synagogue and a Jewish school (école israélite) in Sétif.Footnote 39

In the very same years, a considerable emigration movement of Algerian Muslims from the Sétif region was recorded. On 5 March 1855, more than 300 families from the Riras Dahara and Guebala tribes asked the Algerian colonial administration for permission to leave the colony and settle in the Ottoman regency of Tunis, some 250 km to the east. Historian Kamel Kateb estimates the number of emigrants at 1,500.Footnote 40 According to Anaïs du Tertre, a small mosque had been built by the administration, but was avoided by Muslims in the town.Footnote 41 As late as 1868, there was no Muslim cemetery (a ‘European’ and a Jewish cemetery were in planning in 1861).Footnote 42

Of course, we should neither oversimplify nor overemphasize the contrasting trajectories of Jews and Muslims in Sétif. Urban Jewish elites were not the only ones to engage with French forces in the early years of colonization; similar cases were recorded amongst Muslim elites.Footnote 43 Sources from the early years of Sétif are overall fragmentary and early censuses are prone to inaccuracies, as mentioned above. Moreover, the very different means of domination deployed by the French state to govern Jews and Muslims resulted in an asymmetry in the written records on Jewish and Muslim life, with French-styled Jewish community institutions producing much of the sources on which contemporary research draws, including this study.Footnote 44

Still, the overall picture that arises from sources from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries is that of developments amongst the Muslim and the Jewish population that were often markedly different. By the time of Sétif’s establishment as a civilian town in 1847, some of the key institutions with which the French state and army sought to categorize and govern Algeria’s native population as distinct ethno-religious groups had already taken shape. Thus, once the military site had been declared a civilian town, a local bureau arabe was established – part of a network of military institutions staffed by French ethnographers and orientalists that were responsible for the administration of the Algerian Muslim population.Footnote 45 The emerging Jewish community, for its part, was subjected to the authority of the consistory of Constantine, one of three councils (the other two being in Algiers and Oran) that were created in 1845 to administer the Jewish communities in Algeria and oversee a process of thorough reshaping along the French model of schooling and community organization.Footnote 46

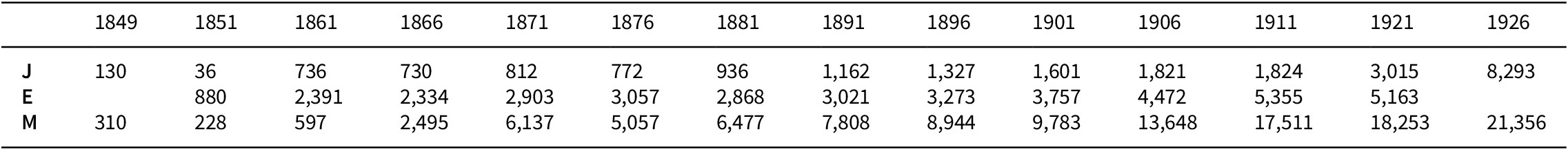

After the shocks of the first three decades of colonization, which resulted in Sétif being a ‘European city’ both officially and demographically, from 1866 onward the Algerian population grew more constantly and rapidly than the European one. If early figures are to be trusted, the Jewish population grew eightfold between 1849 and 1871, the Muslim population almost twentyfold (see Table 1). In this case, too, the figures reflect very different social and political developments. While many European residents were military officers and settlers, the quick growth of the Muslim population was to a great extent the result of cantonment policies in the region, which forced entire tribes to vacate their land and internally migrate. The increase in the Jewish population was most likely the result of both natural growth and internal migration from neighbouring communities. Another factor of population growth was Sétif’s status as the seat of a sous-prefecture from 1858. This administrative status, one level below that of the département, carried a variety of public posts with it, which were open only to full French citizens – a legal status possessed until 1870 only by French settlers, from 1870 by Algerian Jews and from 1889 by non-French Europeans. The vast majority of Algerian Muslims were excluded from full French citizenship and thus from public office until the final days of French colonial rule.Footnote 47

Table 1. Population development in Sétif, 1849–1926 (J = Jewish, E = European, M = Muslim)

Source: Eisenbeth, Le Judaïsme nord-africain, 165–78.

By the eve of World War I, ‘European’ Sétif was stagnating. A clear majority of the population was Muslim, even after an emigration wave of Algerian Muslims from Sétif and the neighbouring Bordj-Bou-Arréridj in 1909–10.Footnote 48 The local Jewish community, by now deeply affected by French ‘assimilation’ policies, prospered. In 1900, it was strong enough to demand having its own selected representation in the consistory of Constantine, and from 1904 it formed its own consistory.Footnote 49 Despite a wave of Jewish emigration from Algeria to Tunisia and France after 1918, the Jewish community of Sétif once again grew more rapidly than the European population in 1921–29, and by 1931 made a third of the town’s overall population.Footnote 50 The growth of the local Jewish population in the inter-war period may also have been the result of a considerable movement of Jews from the historical centre of Constantine to its outskirts and periphery.Footnote 51 For instance, one of Sétif’s most important and venerated rabbis, Itshak Drai, was born in Constantine in 1873 but moved to Sétif when nominated as the city’s rabbi in his early twenties.Footnote 52 It was out of this demographic development – the growth of the Muslim and Jewish population and the stagnation of the European – that Muslims and Jews moved into housing complexes originally built for Europeans of lower classes.

Overall, Sétifian Jews lived in larger families than the Algerian-wide Jewish average, earned their living from low-income professions and lived in very humble housing conditions. Almost half of the Jewish families in Sétif had four or five children (297 out of 614 families), compared with less than a third in Constantine (604 out of 2,119) and less than a fifth in Algiers (853 out of 4,773).Footnote 53 The most important professions amongst Sétifian Jews were jewellers (72), maids and domestic servants (107), traders (128), cobblers (180) and employees in the commercial sector (210).Footnote 54 The majority of Jewish households in Sétif lived in dwellings of just one room, including families of 4–7 people.Footnote 55 The dwelling of the hara, with single-room units and shared facilities, was an important agglomeration of these lower echelons of Jewish society.

However, as elsewhere in Algeria, the early twentieth century also witnessed the emergence of a new, well-organized Jewish middle class. By the 1930s, Sétifian Jews confidently referred to their city and their collective existence in it as Sétif la fervente (‘fervent Sétif’).Footnote 56 This development resulted in new ethno-class tensions. In 1935, the Sétifian politician Ferhat Abbas published a scathing article on the new, ‘Westernized’ Jewish bourgeoisie, accusing the ‘Jewish bourgeois’ of oppressing his ‘companion of yesterday, the Muslim of Algeria’.Footnote 57 These harsh words reflected new dynamics of Jewish upward mobility and emerging ethno-class hierarchizations and tensions.Footnote 58 Thus, while Jewish maids usually worked in European households, Muslim maids were often employed by Jewish families – a fact that caused grievance and was picked up by a Constantine-based newspaper in 1926.Footnote 59 This emerging stratification was to become a key factor of living together in the Sétifian harat.

Living in the harat: intimacy and inequality

The spaces of shared Muslim–Jewish living that began to emerge in Sétif in the inter-war period and would come to be known as harat were atypical in their time and place. Spatial separation and new neighbourhoods were the name of the game in the colonized Maghreb of the early twentieth century. French planners and architects sought to contrast historic city centres with new, ‘modern’, ‘salubrious’ quarters, to separate Europeans from ‘natives’ and to attain a ‘zoning’ of cities according to different functions such as housing, industry, commerce or administration.Footnote 60 In Sétif, this was driven by various local actors – Europeans, Jews and Muslims alike – who constructed affordable dwellings designated for the Muslim population on the outskirts of the city in the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 61 While Muslims, Jews and Europeans of lower classes shared residential and commercial spaces in many Algerian towns and cities, few sites defied the very demarcations of private and public, ‘modern’ and ‘backward’, centre and periphery like the harat. They developed as sites of common, even intimate cross-communal cohabitation; they emerged within the old nucleus of Sétif; and they combined private family spaces, shared communal facilities and commerce.

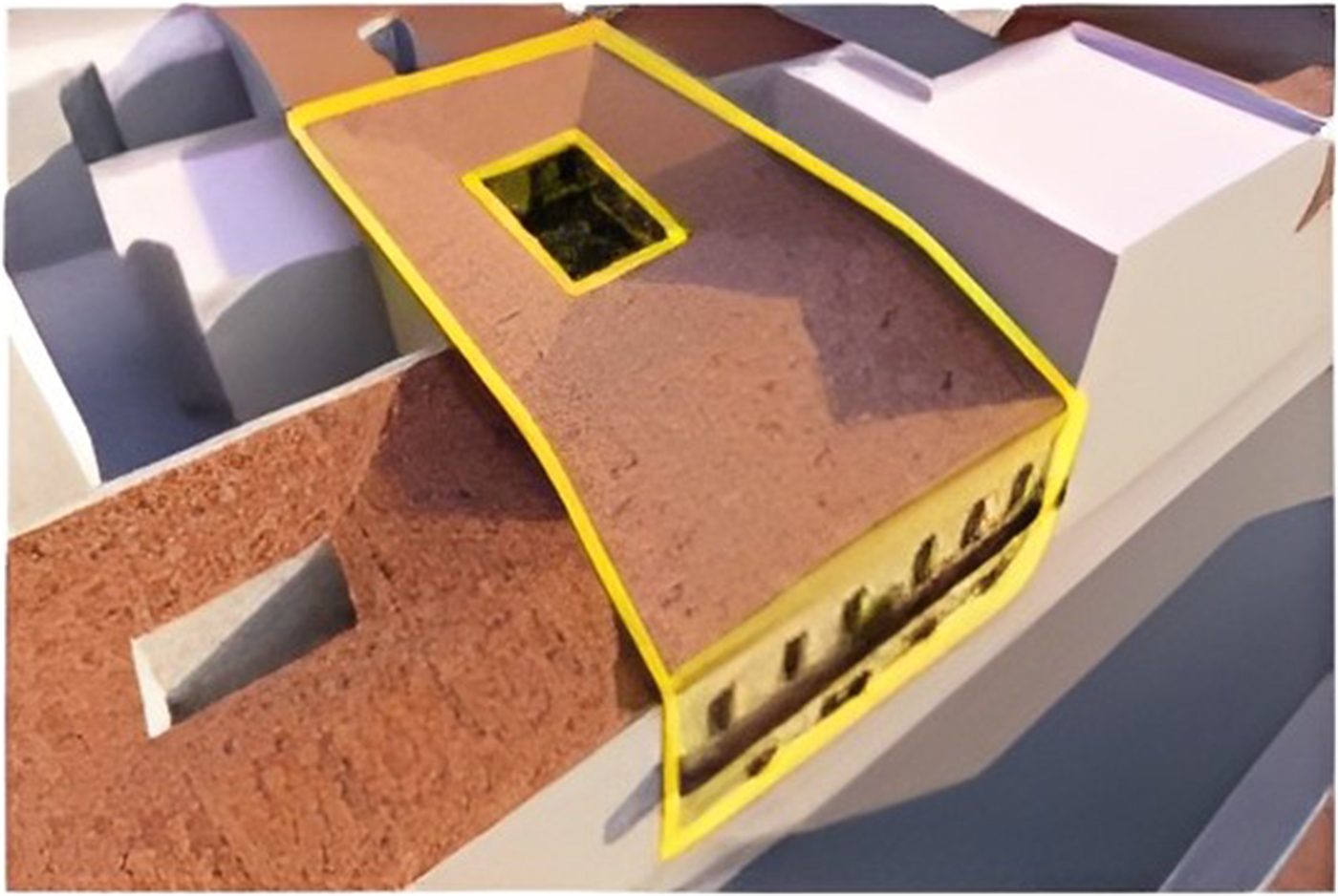

The Jewish–Muslim harat emerged in housing complexes originally built for lower-class Europeans in the late nineteenth century. We know of at least four such cases, all of which were located within the town’s early nucleus.Footnote 62 Most harat were built on lots of approximately 15x30 square metres and were designed to house between 15 and 30 households. A typical hara had only one entrance from the street, leading through a passage to the interior, shared courtyard, around which small dwellings were arranged on two floors. Each dwelling consisted of a kitchen and a single room that served the multiple functions of everyday life. On the first floor, the dwellings were connected by an open gangway or gallery (Figures 6–8). Interviews with residents from the mid-twentieth to the early twenty-first century reveal a process by which Algerian residents claimed these complexes not only spatially, but also linguistically, referring to spaces built along European models with local Arabic terms. The courtyard was referred to as haouch, the dwelling units as buyut (singular: bayt), the gallery on the first floor as stiha. Footnote 63 Finally, the term hara was itself Arabic, designating an amalgamation of houses or a neighbourhood (hara could also imply an area with a large Jewish population in Tunisia and parts of Algeria).

Figure 6. Digitally generated models of the Harat Denfendini: façade.

Source: Dalli Ouassim Zaidi, ‘Réhabilitation, reconversion d’une harat au centre ville de Sétif. Cas d’étude: Harat Defendini’ (Université Ferhat Abbas – Sétif 1 Master’s thesis, 2021) (courtesy of the author).

Figure 7. Digitally generated models of the Harat Denfendini: 3D view from above.

Source: Zaidi, ‘Réhabilitation, reconversion d’une harat au centre ville de Sétif’ (courtesy of the author).

Figure 8. Digitally generated models of the Harat Denfendini: view with neighbouring houses.

Source: Zaidi, ‘Réhabilitation, reconversion d’une harat au centre ville de Sétif’ (courtesy of the author).

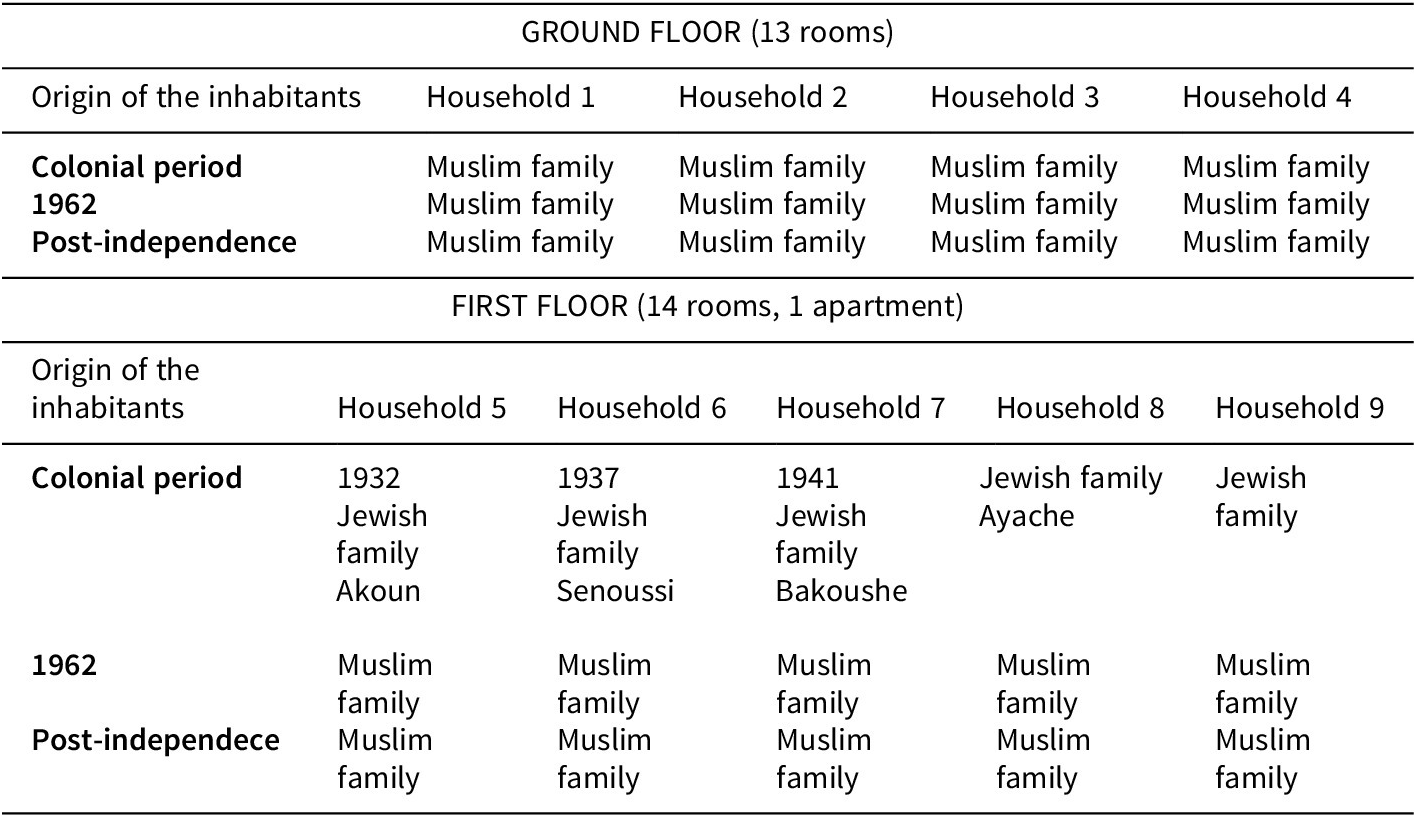

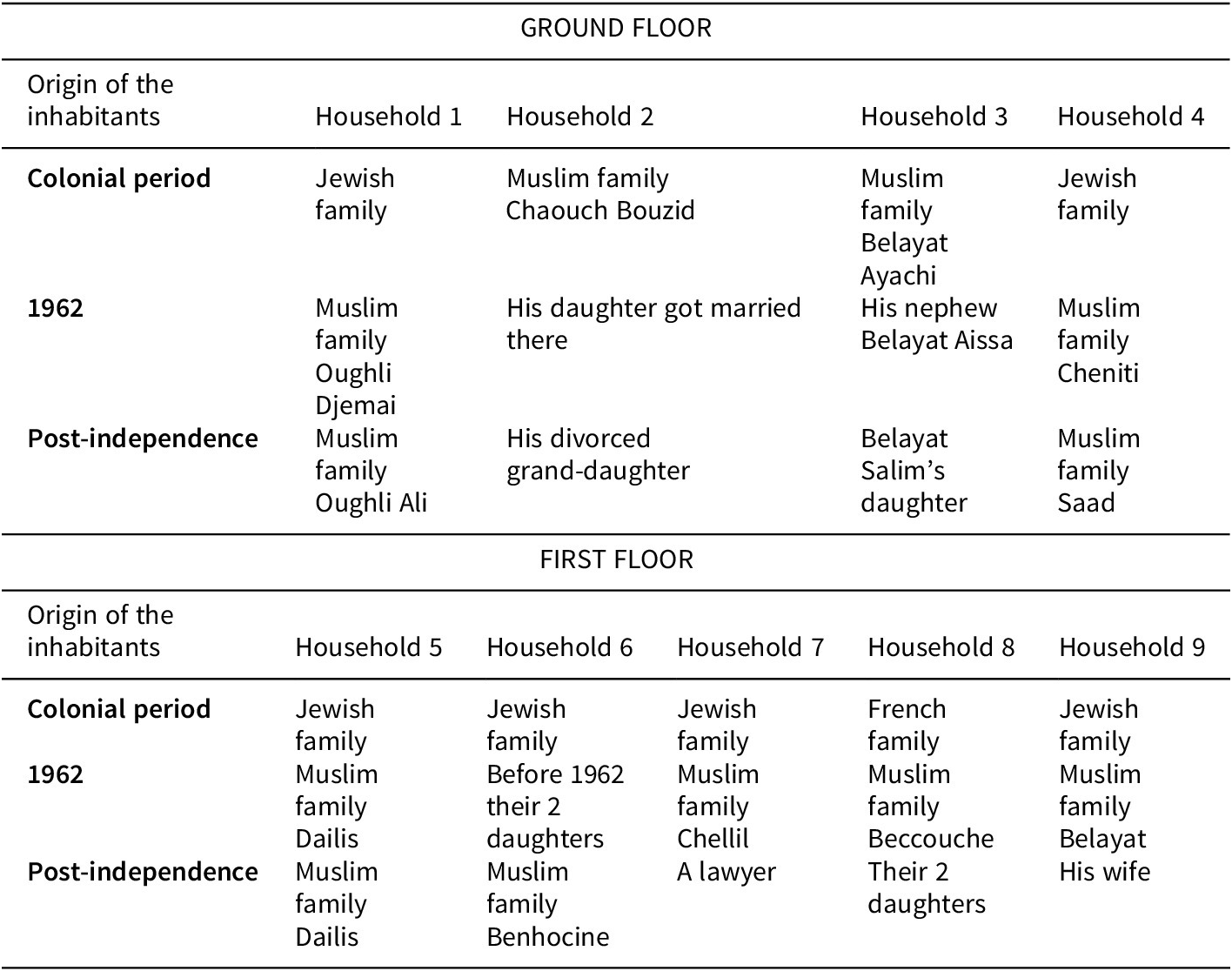

While the harat brought together residents of different communities and classes, they were also spaces where socio-economic and legal hierarchies were markedly present. The ground floor was the one exposed to the outer world. It was poorly lit and with poor circulation of air and at times outrightly insalubrious. It had no windows opening to the street and was mostly where the toilets were. It was inhabited almost exclusively by Muslim families, and at times by Jewish lodgers. The first floor, by contrast, was only accessible through a staircase within the harat, was better lit and with better air circulation. It featured windows overlooking the street but was less exposed to the outer world (see Tables 2–3).Footnote 64

Table 2. Residents of the Harat Hmammou in the colonial and post-colonial period

Source: authors’ interviews with current residents, 2021–23; Bahloul, La maison de mémoire, 38–21.

Table 3. Residents of the Harat Fiata during the colonial and post-colonial period

Source: author’s interviews with current residents, 2021.

The most famous and well-studied hara is the Harat Hmammou, better known as Dar Refayil, the name by which it was referred to in Joelle Bahloul’s seminal study of Jewish–Muslim cohabitation in colonial Sétif. Bahloul interviewed residents and former residents of the hara in the 1980s, first in France, where the majority of Algerian Jews settled down after Algerian independence in 1962, and later in Sétif. But Harat Hmammou was not a singular case. Another documented site of Jewish–Muslim cohabitation is that of the Harat Fiata. Constructed in 1923 at a site on the south-western edge of the city centre (currently the rue Fellahi Laid), this complex contained nine households on a site of 486 square metres. Until 1962, the majority of households were Jewish, with two Muslim families living on the ground floor and one French family living on the first floor. Interviews with current residents suggest a significant pattern of continuity from 1962 to the present, with some dwellings still inhabited by the descendants of those who moved in following the emigration of the Jews of Sétif (see Table 3).Footnote 65

Testimonies by former and current residents help to reconstruct the day-to-day reality of cross-communal encounter and its significance within the context of colonial society. Interview partners recalled the significance of one’s dwelling in the social fabric of Sétif, with individuals often identified according to the housing complex in which they lived: ‘Rachel of Dar-Zmemra’, ‘David of Dar-Warda’ or ‘the child of Dar-Braydjiyin’. This way of situating oneself in history and geography persisted after the Jewish emigration from Algeria to France.Footnote 66

Despite fond memories evoked by harat residents in retrospect, the social reality of living together was wrought with tensions and had a clear impact on one’s social standing. The Jewish family at the centre of Bahloul’s study – her own ancestors – moved to the hara as the result of economic hardship in 1937, and the very fact of living with Algerian Muslims decreased their social standing within the local Jewish community. Socio-economic stratifications were very marked in the space of the hara. In the case of Harat Hmammou, the owner was Jewish and lived on the first floor. Other Jewish families lived on the first floor as well, while Muslim families lived on the ground floor, which was more exposed to the street and included the toilets and communal spaces.Footnote 67 Moreover, proximity to the owner was also socially significant, and there was more mingling between the owners and Jewish residents than with Muslim residents.Footnote 68 Even the Arabic language itself – or better said, the different dialects and registers of Arabic – functioned as a marker of difference, since living with Algerian Muslims required Jewish residents to speak Arabic at a time when considerable segments of the Jewish population were invested in political and to some extent cultural French assimilation. A former resident of the Harat Hmammou recalled: ‘I spoke Judeo-Arabic with my children, it’s not the same Arabic. The Arab did not speak like us… Judeo-Arabic resembled more the literary Arabic!’Footnote 69

Crucially, the inter-war period also brought some serious challenges to the various modes of Jewish–Muslim interactions. Shockwaves from the escalating conflict in Palestine and the rise of Nazi Germany, coupled with the agitation of the far right and struggles over participation and rights in Algeria, led to clashes on several occasions in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In the summer of 1929, authorities throughout Algeria were alarmed by the echoes of recent cross-communal violence in Palestine. In Sétif, the mayor recorded a tense atmosphere between Jews and Muslims and asked the colonial authorities to monitor and limit the circulation of news from Palestine to maintain public order.Footnote 70 The gravest violence erupted in August 1934 in Constantine when a minor dispute between a drunk Jewish soldier and a group of passersby near the Sidi Lakhdar mosque escalated into four days of violence in the city and nearby localities that left 25 Jews and 3 Muslims dead, dozens injured and dozens of houses and shops owned by Jews pillaged.Footnote 71 Tensions remained high for months, and in February 1935, during tense elections to local councils, violence broke out between Jews and Muslims in Sétif – though it was quickly contained.Footnote 72

Secluded from the street and the outside world, the harat defied or at least counterweighted such tensions. Former residents recalled that the doors of the different dwelling units would usually be left unlocked or even open. As Bahloul quotes one of her interviewees:

We would leave the doors open, we never closed them. And it’s for that reason that we lived like a family. If a [female] neighbour needed something, she would come, she didn’t need to knock on the door. Here [in France] the doors are closed. But there [in Sétif], all the doors were open. When we woke up in the morning, we opened the door and left it open until the evening when we went to bed and closed it. So we lived like a family, not like neighbours.Footnote 73

Another former resident expressed this notion of common life as related mainly to day-to-day life even more vividly: ‘We lived from one day to another, without considering the time. The Arabs and the Jews, they’re the same! The Jews are like us.’Footnote 74 However, this sense of harmony was interrupted on a few occasions. On Jewish holidays, for instance, a curtain would be put up around the owner’s balcony, where the Jewish families gathered – with the explanation that they did not wish to ‘disturb’ their Muslim neighbours with the sight of a Jewish ritual.Footnote 75

As Bahloul argues, ‘the relational proximity between these two groups was mainly motivated by the need to carry out specific domestic tasks of day-to-day life’.Footnote 76 It was in retrospect, when reflecting on the events that brought an end to Jewish life in Algeria, that residents of the harat began to construe this space as a site not only of everyday routines, but of memories of co-existence, leaving aside the tensions, inequalities and diverging trajectories of colonial society. The ‘nostos’ (house) of ‘nostalgia’ (home-longing, homesickness) was in this case a very concrete one.

Conclusion

The cohabitation that emerged in the housing complexes that came to be known as harat was fragile. It was defined by spatial proximity, but also by the institutionalized inequalities of the Algerian colonial order. The Muslim and Jewish families living in these housing complexes shared their daily routines, their facilities and much of each other’s experiences, but their political status and the overall trajectory of their communities differed significantly. Sharing an urban space with no pre-colonial history, their relations and interactions were at once shaped by the colonial order and defied some of its key elements.

What, then, was the social and political significance of being neighbours in colonial Sétif? The harat emerged as shared living spaces in the least likely moment of Algerian history. The 1930s and 1940s saw the Algerian struggle for political participation and a reform of the colonial order in 1936–38, the abrogation and reinstation of Jewish citizenship between 1940 and 1943, the escalation of the Palestine conflict and its global shockwaves and the beginning of civilian violence in Sétif in 1945. Yet, though such developments are certainly present in the memoires of local Jews, they do not seem to have rendered the intimate neighbour relations of the harat impossible, even during the most violent years of the Algerian War, as tensions between the Front de libération nationale (National Liberation Front) and the Jewish community ran high in Sétif and Constantine, including attacks on Jewish personalities.Footnote 77

Clearly, the mere fact of being neighbours could not constitute a counterweight to the major political developments of the mid-twentieth century: the rise of Algerian nationalism, the radicalization of colonial domination, the descent to violence and Algerian War, or independence. Yet, the seclusion that characterized the harat does seem to have been more than purely spatial. The recollections of former and current residents of the harat suggest a parallel way of situating oneself in the city and the world: a view that, while neither confirming nor contradicting the divisions of the colonial and post-colonial age, nevertheless implies a certain distance from abstract forms of belonging, emphasizing instead the significance of concrete, everyday encounters in one’s worldview and memory.