After twenty years of war in Afghanistan, the United States and its coalition partners fully withdrew military troops from the country in August 2021. International observers expected the withdrawal, announced after an agreement was reached between the Taliban and the Trump administration in February 2020. However, as US forces exited, the Taliban seized control of the country with a remarkable speed that was unanticipated by the Biden administration (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Lemire and Boak2021). On 15 August 2021, the capital city of Kabul fell to Taliban insurgents. Distressing images from evacuations at Hamid Karzai International Airport, reminiscent of images from US withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973, prompted widespread criticism of US leadership.

In the aftermath of these events, questions arose about whether a poorly executed withdrawal from Afghanistan harmed America’s image abroad.Footnote 1 Policy makers and commentators posited the events that transpired could have a wide range of potential effects: jeopardizing the credibility of US leadership (Collins Reference Collins2021), damaging the country’s reliability as an alliance partner (Pompeo Reference Pompeo2021), making adversaries of the United States appear more attractive (Kynge et al. Reference Kynge, Astrasheuskaya and Yu2021), or even ‘serv[ing] as a bookend for the era of US global power’ (Wright Reference Wright2021).

Yet others argued that the fall of Kabul would not diminish America’s standing in the world because the United States had recovered from many past foreign policy disasters (Ross Reference Ross2021). Similar arguments emphasized that allies were unlikely to doubt the broader credibility of US security commitments because the situation in Afghanistan was unique (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2021; Walt Reference Walt2021). In fact, some argued that the withdrawal would further reassure American allies by demonstrating that the United States would prioritize support for other regions beyond the Middle East (Casler Reference Casler2021; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Byun and Ko2024).

Debates about the consequences of US withdrawal from Afghanistan connect to theoretical questions about how foreign policy failures impact a country’s image and attractiveness in international politics. This paper uses newly compiled data from 17,258 survey respondents in 24 countries in the Gallup World Poll (Gallup 2023) to explore the effects of the Afghanistan withdrawal on assessments of US leadership and that of rival powers. We focus on this outcome because how the global public perceives a country’s leadership is a reflection of that country’s soft power – or the ability to attract and influence international actors through non-coercive means (Nye Reference Nye1990).

Our research asks and answers two questions. First, to what extent do perceived failures in international politics impact assessments of a country’s leadership? We find that the US withdrawal from Afghanistan had a substantive negative impact – a decrease of 4 to 5 percentage points – on public approval of US leadership. To benchmark the size of the effect, we demonstrate that it corresponds to roughly one-third of the size of the effect of the January 2021 presidential transition from Donald Trump to Joe Biden on global public approval of US leadership. Relative to comparable studies, our estimates are larger in magnitude than the estimated effects of militarized interstate disputes (Seo and Horiuchi Reference Seo and Horiuchi2024) and high-level diplomatic visits (Goldsmith et al. Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Matush2022) on assessments of a country’s leadership.

Second, in the context of great power rivalry, is soft power ‘zero-sum’? That is, do damages to one great power’s image abroad increase the attractiveness of its adversaries? In an era of renewed great power competition, influence and soft power are frequently framed as a zero-sum competition between the United States and its foreign rivals. Many speculated that the Afghanistan withdrawal signaled American decline, enhancing the international standing of its adversaries. Our analysis shows, however, that the US withdrawal from Afghanistan did not increase global support for US rivals like Russia and China. Our findings suggest that while perceived foreign policy failures can destabilize confidence in a country’s leadership, they do not inherently bolster support for alternatives.

Global Public Opinion and the US Withdrawal from Afghanistan

This paper examines two claims about the impacts of foreign policy failures. The first claim is that foreign policy failures negatively impact evaluations of a country’s leadership in the eyes of international observers. Major decisions in foreign affairs affect a country’s image, reputation, or standing in international politics. One reason why countries are concerned with global public opinion is because it is a reflection of soft power.Footnote 2 Shaping global public opinion is a strategic priority for great powers, who view soft power as an important tool of international influence. Leaders within the United States, China, and Russia, for example, have historically invested considerable resources in crafting their country’s image abroad in various ways through both rhetoric and action.Footnote 3 Countries care about global public opinion both as an end in itself and because it can shape and constrain the actions of foreign governments. For instance, in a study of global reactions to the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, Goldsmith and Horiuchi (Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2012) show how decisions made by the United States impacted foreign public opinion in third-party countries beyond Iraq, in turn affecting the foreign policies of those countries towards the United States.

Following the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, two main narratives emerged that emphasized that the events damaged America’s image and attractiveness as an ally. One narrative was that the execution of the withdrawal was disastrous; it would decrease approval of US leadership by indicating that America was weak, incompetent, or in decline (Bhurtel Reference Bhurtel2021; LaFranchi Reference LaFranchi2021). Some commentators suggested that the withdrawal marked the end of an era of US hegemony (Wright Reference Wright2021). Others emphasized that US adversaries would opportunistically take advantage of America’s decline to advance their own interests. For instance, Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS) wrote about the Afghanistan withdrawal: ‘Our enemies certainly noticed. Chinese media quickly claimed the United States would not come to Taiwan’s aid in the event of a Chinese invasion. Russian President Vladimir Putin decided the American star was fading, and he felt confident to attack Ukraine’ (Wicker Reference Wicker2023).

A second, related narrative that emerged was that the rapid fall of Kabul to the Taliban harmed US credibility; it would decrease approval of US leadership by demonstrating that America was not a trustworthy or reliable ally. In international relations, this argument connects to the concept of reputation for reliability, or perceptions of a country’s ability to maintain commitments to allies and partners (Crescenzi et al. Reference Crescenzi, Kathman, Kleinberg and Wood2012; Crescenzi Reference Crescenzi2018). Both policy makers and publics care about how international observers perceive their country’s reliability and are concerned about the reputational consequences of reneging on commitments (Levin and Kobayashi Reference Levin and Kobayashi2022; Tomz and Weeks Reference Tomz and Weeks2021; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Quek and Souva2023). Former US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo argued that withdrawal from Afghanistan would ‘harm America’s credibility with its friends and allies’ (Pompeo Reference Pompeo2021). Other commentators claimed that the withdrawal ‘puts [American] security cooperation relationships at risk’ (Cooper Reference Cooper2021) and left allies with ‘nagging doubts about whether the US has the patience for long fights’ (Khalid Reference Khalid2022).

Interestingly, many scholarly analyses of the Afghanistan withdrawal concluded that its consequences for America’s image abroad were more limited than suggested in popular commentary (Casler Reference Casler2021; Kertzer Reference Kertzer2021; Lee Reference Lee2023). These analyses are consistent with findings that actors who are otherwise viewed favorably in international politics can ‘weather the storm’ when their reliability is called into question (Donahue and Crescenzi Reference Donahue and Crescenzi2023). In fact, some studies find that the Afghanistan withdrawal did not harm US standing in the world and may have increased perceptions of America’s reliability in the eyes of international audiences. The most direct evidence to this effect comes from Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Byun and Ko2024), who, in a series of novel survey experiments, show that respondents in South Korea primed to think about the Afghanistan withdrawal are more confident about US security commitments when they recognize that it might allow the United States to prioritize resources for East Asia over the Middle East.

The second claim this study examines is that foreign policy failures of one country increase the attractiveness of the leadership of its adversaries. This argument is linked to the idea that soft power in international politics is ‘zero-sum’: countries benefit from the foreign policy failures of their rivals. This topic has gained particular interest in an era of intensifying great power competition, which is increasingly framed as an ideological contest between Western democracies and their authoritarian rivals (Brands Reference Brands2018; Kroenig Reference Kroenig2020). The ability to attract and influence others is an important aspect of contemporary great power competition (Nye Reference Nye2023). It is well-documented that great powers such as China and Russia employ a variety of strategies to balance against American soft power (Owen Reference Owen and Ohnesorge2023).

Given the competitive – and sometimes adversarial – nature of US–China and US–Russia relations, it has become commonplace to talk about the relative attractiveness of these countries abroad. Recent reports ask which great power is ‘winning hearts and minds’ globally (Ritter and Ray Reference Ritter and Ray2024) and measure the relative influence of great powers in different regions of the world (McNerney et al. Reference McNerney, Sotubo and Egel2024). Yet there remain open questions about the extent to which great power rivalry has actually been internalized by global publics as ‘zero-sum’.Footnote 4 Perhaps the most convincing empirical evidence on this question comes from Blair et al. (Reference Blair, Marty and Roessler2022), who use global public opinion data to evaluate whether foreign aid affects US and Chinese soft power in Africa. The researchers find that aid programmes have mixed effects on perceptions of US and Chinese leadership that are not necessarily zero-sum. Aid from China, for instance, does not reduce favorability towards the United States or towards US values. Our paper takes a similar approach but uses global public reactions to foreign policy disasters – as opposed to aid projects – to investigate whether the attractiveness of great powers is zero-sum in the eyes of foreign publics.

In popular commentary, the US withdrawal from Afghanistan is often perceived as having zero-sum consequences for great power competition. Specifically, a prominent argument was that the disastrous US withdrawal would increase the perceived standing of Russia and China globally. Some argued that America’s failures in Afghanistan emboldened Russian and Chinese leaders, who might seek greater geopolitical influence, especially in the Middle East (Kynge et al. Reference Kynge, Astrasheuskaya and Yu2021). Others, however, questioned the prevailing ‘zero-sum interpretation’ (Scobell Reference Scobell2021) of the withdrawal.

Subsequent narratives from Moscow and Beijing heavily emphasized that the US withdrawal from Afghanistan was disastrous and indicative of broader Western decline. Reports noted that Russian officials ‘openly reveled in critiquing the U.S. withdrawal’ (Chesnut and Waller Reference Chesnut and Waller2021). Zhou Bo, a former Senior Colonel of the People’s Liberation Army, wrote in The New York Times that Beijing was ‘ready to assert itself as the most influential outside player in an Afghanistan now all but abandoned by the United States’ (Bo Reference Bo2021). In both Russia and China, official statements and state media reinforced narratives of an America in decline, indicating that adversaries of the United States saw its foreign policy failures as beneficial to their own international standing (Fischer and Stanzel Reference Fischer and Stanzel2021). Once again, however, whether these narratives were subsequently internalized by global publics is an open empirical question.

Research Design

To investigate claims about the impacts of foreign policy failures on global public opinion, we leverage surveys conducted worldwide by the Gallup World Poll (Gallup 2023) during the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. Our primary outcome measure asks respondents to evaluate US leadership (‘Do you approve or disapprove of the job performance of the leadership of the United States?’). Our secondary outcome measures assess whether the attractiveness of great powers is zero-sum by capturing evaluations of Chinese and Russian leadership (‘Do you approve or disapprove of the job performance of the leadership of Russia / China?’).

Our main sample consists of 17,258 respondents from 24 countries across 5 continents who answered our primary outcome question in the 30 days before or after 15 August 2021, the day that Kabul fell to the Taliban.Footnote 5 Our focus on this time window means that we capture global reactions to how the withdrawal was executed by US leadership and portrayed in the media. We emphasize that this differs from public opinion about the US decision to exit Afghanistan in general, which public opinion polls suggest was largely supported by international audiences (Clancy Reference Clancy2022). Appendix C shows that global search interest in Afghanistan peaked on 16 August and describes how international media outlets characterized the US withdrawal.

To estimate the effect of the withdrawal, we compare responses just before and just after 15 August. This ‘unexpected event during survey’ design mirrors quasi-experimental approaches that draw on large-scale surveys to study how public opinion is affected by events such as close elections (Bateson and Weintraub Reference Bateson and Weintraub2022), high-profile court decisions (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Gandhi and Grasse2025), terror attacks (Epifanio et al. Reference Epifanio, Giani and Ivandic2023), and natural disasters (Cao and Su Reference Cao and Su2025).

There are two key assumptions required for causal inference: excludability and ignorability (Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020). Excludability requires that the timing of the interview affects the outcome only through exposure to the Afghanistan withdrawal – and not another simultaneous event. The ignorability assumption requires that the timing of interviews be as good as random – specifically, that timing is uncorrelated with respondents’ potential outcomes of support for US leadership. In the appendix, we present a detailed discussion of the assumptions required for inference (Appendix B) and present several analyses showing the plausibility of these assumptions. First, we conduct balance tests which show that the samples before and after the withdrawal are relatively similar in terms of key demographic variables (Appendix B). Second, we conduct a quantitative text analysis of news stories, which shows that there is a sharp increase in the salience of the conflict in Afghanistan on the date of the withdrawal and that there are no other major events happening concurrently that could threaten inference (Appendix D). Finally, throughout all of our analyses, we focus on within-country comparisons, via inclusion of country fixed effects, to ensure that our results are not driven by shifting composition of the sample.

The treatment effect we estimate inevitably depends on the baseline expectations. Analysis of media coverage and public interest in the withdrawal, presented in Appendices C and D, suggests that the chaotic reality of the withdrawal differed dramatically from baseline expectations. So the treatment effect is defined relative to expectations in a baseline status quo counterfactual in which the United States had not withdrawn from Afghanistan, but was planning on it. Alternatively, we could also consider a counterfactual in which the withdrawal occurred just as it did, but in which it received little news coverage and public visibility. Unfortunately, we cannot disentangle the effect of the withdrawal and that of news coverage or public salience of the withdrawal because, in reality, they occurred simultaneously. Difficulty with decomposing the treatment effect into expectations, salience, information, and other factors is not unique to this study, but is an inherent limitation of any study that estimates the effect of specific events.

Results

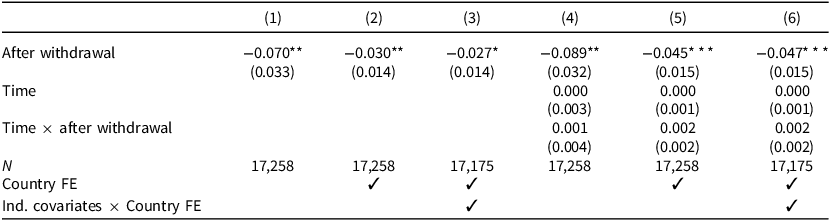

We first look at the trend in approval of US leadership during the Biden administration between April 2021 and January 2023. Figure 1 shows the share of survey respondents who approve of US leadership, residualized by country fixed effects.Footnote 6 Visually, the figure suggests a substantial decrease in global approval of US leadership directly after 15 August 2021. To investigate this relationship, we turn to a series of regression estimates in Table 1. The outcome variable in these models is an indicator for whether the respondent approves of US leadership. We model approval in the thirty days before and after 15 August 2021, as a function of time, the respondents’ country, and individual-level covariates.Footnote 7 The coefficient on After Withdrawal estimates the change in approval of US leadership after 15 August.

Figure 1. Trends in US leadership approval during Biden administration.

Table 1. Regression estimates of change in approval of US leadership after fall of Kabul

Note: Individual covariates include age, gender, and education. All regressions include survey weights. Standard errors are clustered by country. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The first three columns of Table 1 compare responses collected before and after 15 August, without adjusting for time trends. Column 1 shows that respondents interviewed in the month following 15 August 2021 were around 7 percentage points less likely to say they approve of US leadership than those interviewed the month before. Column 2 adds country fixed effects, allowing for within-country comparisons between respondents interviewed before and after withdrawal.Footnote 8 Here, the point estimate is smaller – indicating a decline in approval of US leadership by about 3 percentage points – but remains statistically significant. Column 3 adds individual-level controls for age, gender, and education, all interacted with country indicators, and the result is nearly identical. Columns 4–6 allow for differential time trends before and after 15 August. In these specifications, the coefficient on the After Withdrawal indicator represents the modeled difference in opinion of respondents interviewed on 15 August, relative to what we would expect based on the prior trend. These results are broadly similar, showing a statistically significant decrease in approval of US leadership. Our preferred specification, in Column 6, adjusts for time trends, country fixed effects, and individual-level covariates. This specification suggests a 4.7 percentage point decline in approval of US leadership after the fall of Kabul.

We can benchmark the effect size of our estimates against studies that use similar data and methods. Seo and Horiuchi (Reference Seo and Horiuchi2024) use Gallup World Poll data to show that militarized interstate disputes decrease popular support for a country’s leader by 1–2 percentage points. Goldsmith et al. (Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Matush2022) find that high-level diplomatic visits increase approval of the visiting country’s leader by an average of 2.3 percentage points. Although these are not directly comparable samples given the timing of our study, it is notable that we find larger effect sizes.

Another method of benchmarking estimates is to consider how global public approval of US leadership changed as control of the White House shifted from Donald Trump to Joe Biden in 2021. In Appendix H, we show that there was a very large (12 percentage point) increase in global approval of US leadership after Biden assumed the presidency in January 2021. In comparison to this benchmark, the effect of the Afghanistan withdrawal is still moderately large: roughly one-quarter to one-third as large as the effect of a major US presidential transition.

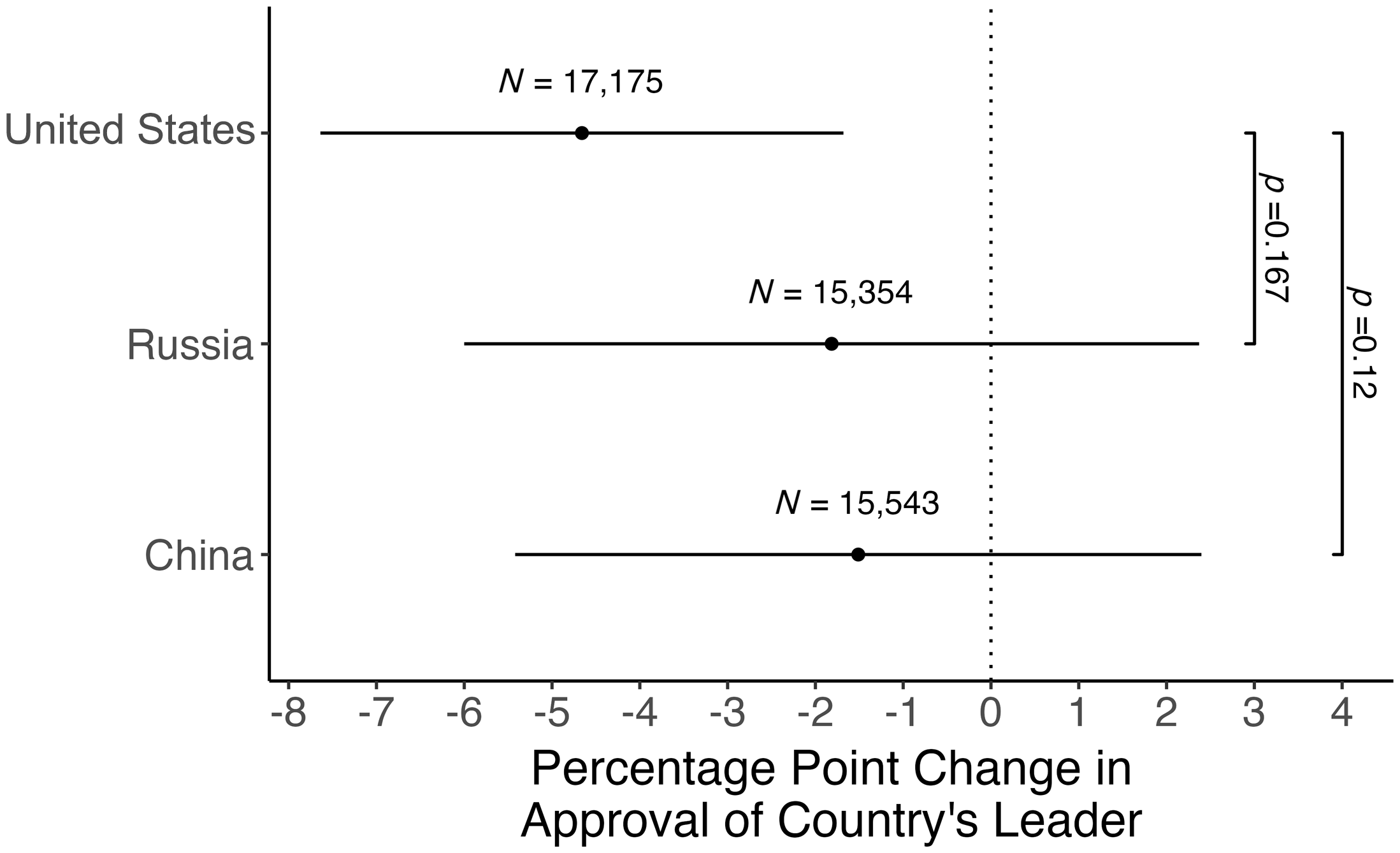

Having some evidence that the Afghanistan withdrawal negatively impacted global perceptions of US leadership, we next explore claims about whether soft power is ‘zero-sum’. This claim anticipates that global approval of US adversaries like Russia and China would increase as approval of US leadership decreases. We use the same strategy to look at the corresponding effects of the withdrawal on assessments of Russian and Chinese leadership, which use the same wording as our primary outcome measure. However, as Figure 2 shows, we do not see a corresponding change in approval for US adversaries.Footnote 9 The null results suggest we do not have any evidence to support the claim that the relative attractiveness of great powers is zero-sum.

Figure 2. Change in approval of US and rivals’ leadership after fall of Kabul.

Note: RD estimates that include individual-level covariates (age, gender, education), country fixed effects, and standard errors clustered by country of respondent. Data are trimmed to a bandwidth of 30 days. Models estimated with survey weights. Brackets indicate p-values for tests of equality between estimates.

Our overarching finding is that favorability towards US leadership decreased globally after the Afghanistan withdrawal, but approval of US adversaries did not increase. We consider a few threats to inference based on these conclusions. The first is the possibility of pretreatment bias: since US withdrawal from Afghanistan was an expected event, perhaps this was reflected in respondents’ assessments of US leadership. In February 2020, the Trump administration signed the Doha Agreement with the Taliban, committing the United States to withdraw its troops the following year. Yet, while the withdrawal was expected, the abrupt Taliban takeover was unanticipated. This means that our analysis captures reactions to the rapid fall of Kabul rather than the announcement of impending US withdrawal. However, it is possible that some respondents were paying closer attention to advances made by the Taliban in August 2021. In Appendix F, we conduct a ‘donut’ regression discontinuity model that excludes surveys conducted 13–17 August 2021 to account for the possibility that respondents just before 15 August were ‘pretreated’. In these analyses, our key results are unchanged. Importantly, this potential pitfall biases against finding an effect of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, so the fact that we still find a sizeable effect is notable.

Another potential concern is that the negative effects are driven by a small number of countries. Figure 3 displays the change in US approval after 15 August 2021 within each country. The figure shows that in a large majority of countries in the sample, approval of US leadership decreased following the fall of Kabul. This suggests the effects are neither driven by a handful of countries, nor are there heterogeneous effects by baseline approval of US leadership. Appendix G shows that our results are robust to the exclusion of different countries.

Figure 3. Change in US approval before and after 15 August 2021.

Note: The start (end) of each arrow is the average approval of US leadership 30 days before (after) 15 August 2021. Asterisks in country names indicate significance of weighted two-sample t-test; sample sizes in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Conclusion

This paper conducts a real-world test of how foreign policy failures impact the image of the United States and rival great powers in the eyes of international observers. We leverage global public opinion surveys in the field during the fall of Kabul in August 2021. Drawing on data from over 17,000 survey respondents in 24 countries, we find a sizeable decline in support for US leadership in the aftermath of the withdrawal from Afghanistan – a decrease in global public approval of US leadership by roughly 4 to 5 percentage points. We then consider whether the withdrawal enhanced the attractiveness of US adversaries like Russia and China. However, we find no evidence that the attractiveness of great powers is ‘zero-sum’: damage to perceptions of US leadership did not result in a corresponding increase in public approval of Russian or Chinese leadership globally.

Our findings emphasize the need for more nuanced investigations of the consequences of foreign policy failures on global public opinion and soft power. With respect to the case of US withdrawal from Afghanistan, future work might unbundle why and how different dimensions of US image and reputation were impacted and the extent to which those effects persisted across time. Extensions beyond the Afghanistan case might consider whether other foreign policy (or even domestic policy) failures led to similar changes in perceptions of US leadership. Finally, our null findings for claims about the ‘zero-sum’ nature of soft power suggest a need for more research about whether and how narratives of great power competition are internalized by foreign publics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101233.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/89H7PS. We are unable to redistribute the Gallup World Poll data due to the data licensing agreement. However, the Dataverse files list the variables needed for replication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kyle Beardsley, Peter Feaver, Connor Huff, Andrew Kenealy, and Soyoung Lee for feedback on this project.

Financial support

This research was supported by Duke University and University of Pennsylvania.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.