Introduction

Roman coins commemorating the annexation of a newly conquered region into the empire sometimes represented the new province as a kneeling, defeated woman. Writers demonstrated Roman superiority to those in conquered or to-be-conquered lands by characterizing foreign men as effeminate. The sexual violence endemic to conquest was a powerful symbol of subjugation. Indeed, Roman imperialism parallels that of the modern colonial era in the gendered power dynamic central to the functioning of empire.

In the study of modern colonialism, early efforts to forefront the previously neglected experiences of both colonized and colonizer women (Bradford Reference Bradford1996) led to consensus that activities in the domestic sphere—traditionally considered feminine—were central to colonial relations. In what Stoler (Reference Stoler2002, 8) called the ‘intimacies of empire’, employing servants, raising children and sexual relations critically shaped how diverse peoples came together (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2009; Shire Reference Shire2016). Gender was also central to the maintenance of hierarchies of difference between colonizer and colonized: colonizers naturalized their own superiority by gendering race and class distinctions and racializing sex and gender (McClintock Reference McClintock1995). Settler colonialism is heteropatriarchal, with superiority defined through adherence to patriarchal gender roles and hierarchies of power, as well as patriarchal and heteromonogamous modes of kinship (Arvin et al. Reference Arvin, Tuck and Morrill2013; Glenn Reference Glenn2015; Lugones Reference Lugones2007; TallBear Reference TallBear, Rayter and Zisman2022).

To assess the role of archaeology in gendering colonialism, it is useful to identify two distinct veins: first, gender in the lived experience of colonialism, and second, the centrality of gendered worldviews to colonial dynamics. The archaeological record is well suited to studying the first vein (Voss & Casella Reference Voss and Casella2012). Gendered approaches to lived experience include researching colonialism’s impacts on the gendered body (Loren Reference Loren2008; Robb Reference Robb, Borić and Robb2008); gendered labour or economic opportunity (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Fritz, Lapham, Moore and Rodning2016; Voss Reference Voss2008a); and sex, marriage, and family dynamics (Voss Reference Voss2008b).

Calls to centre sex and gender in study of the Roman provinces have increased in recent years (Cornwell & Woolf Reference Cornwell and Woolf2023; Ivleva & Collins Reference Ivleva and Collins2020; Vucetic Reference Vucetic2022), and archaeological research has played a critical role. Analysis of material culture has revolutionized our understanding of the role of women in army forts (Allison Reference Allison2008; Greene Reference Greene2015; Van Driel-Murray Reference Van Driel-Murray and Rush1995). Analysis of funerary practices and skeletal remains lends insight into gendered ethnicity, mobility, and health (Eckardt & Müldner Reference Eckardt, Müldner, Millett, Revell and Moore2016; Gowland Reference Gowland2017). Men’s and women’s dress on tombstones demonstrates gendered mobilization of Roman or indigenous ethnicity to signal a family’s positioning between cultures (Carroll Reference Carroll, Stutz and Tarlow2013; Mazurek Reference Mazurek2021; Rothe Reference Rothe2012).

The second vein, the question of gendered worldviews, has proved more challenging: how do we study, through material remains, the way gender systems changed under colonialism? Cornwell and Woolf (Reference Cornwell and Woolf2023, 1–17) specifically acknowledge this challenge of moving beyond gendered behaviour to gender dynamics in the Roman provinces. Even so, scholars have certainly addressed Roman gendered understandings of civilization versus barbarism (Clavel-Lévêque Reference Clavel-Lévêque1996; Lopez Reference Lopez, Penner and Stichele2007; Ramsby & Severy-Hoven Reference Ramsby and Severy-Hoven2007). This imperial dynamic has been tied on a broad level to core Roman ideals of sexuality and gender (Alston Reference Alston2023; Joshel Reference Joshel, Hallett and Skinner1997; Mattingly Reference Mattingly2011, 94–121). However, there is a need to marshal new lines of evidence for on-the-ground impacts of such dynamics. How did individuals come to understand gender itself—gendered difference and gender ideals—in these provincial regions?

I propose to study this impact by applying a somewhat out-of-fashion symbolic approach to the archaeological record, identifying what Ortner (Reference Ortner1973, 1340) calls an ‘elaborating’ symbol centred around gender relations in Rome. This symbol shaped how people conceptualized and categorized diverse aspects of their world, both at the level of the personal and at the level of the state. I track the impact of this Roman elaborating symbol on the worldviews of those in their provinces. This symbolic approach encourages creative thinking, tracking gendered worldviews through material evidence that may, on the surface, seem unrelated to gender. My case study surrounds a highly symbolic body of evidence: a dataset of about 2500 votive offerings deposited at 10 sanctuaries in Roman Britain and northern Gaul.

After a period of prolonged violence, northern Gaul was annexed into the Roman empire around 50 bce. Britain was annexed almost a century later, in 43 ce. While the timelines of conquest differ, the long interconnectivity between these regions led to important cultural similarities in political organization, ritual practice and language (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2001). These peoples were also tied together in Roman imagination as uncivilized northerners, in no small part due to similar attitudes towards proper gendered behaviour that differed from Rome’s (Rankin Reference Rankin1996). My votive dataset spans the centuries post-conquest, including objects offered from about 50–100 years after formal annexation until the abandonment of these sanctuaries (often in the late fourth to early fifth century). Some offerings depict men, gods, or male bodies while others depict women, goddesses, or female bodies. In addition, some offerings can be linked to the gender of the offerer (for example, spindle whorls are generally associated with women’s work). As highly symbolic objects, offerings provide unique insight into challenging-to-access worldviews of offerers. Specifically, I find evidence of gendered worldviews in the material of the offerings themselves: women are more closely associated with permeable materials including clay, bone and glass, vulnerable to breakage and the influence of the environment, while men are associated with the impermeable durability of metal. This symbolic association aligns with Roman gender values. While it is challenging to assess whether this symbolic association was brought about by Roman annexation or pre-dated conquest, such an association between femininity and permeability was uniquely loaded and value-laden in these colonial spaces. This study proposes an approach to access deeply gendered worldviews archaeologically. By connecting material categories to gendered worldviews, it also contributes to ongoing discussions of material symbolism in the ancient world.

Gendered symbolism: Roman permeability

Gender structures were both personal and political in Rome. Most basically, at the level of the family, women were legally, if not always practically, under a man’s control while the ideal Roman man was a strong and true paterfamilias, responsible for making legal and economic decisions for everybody in his household (Cantarella Reference Cantarella, Du Plessis, Ando and Tuori2016; Gardner Reference Gardner1998). Power at the level of the state reflected the values of patria potestas as the emperor took on the role of patres for the Roman people (Lassen Reference Lassen and Moxnes1997). In this way, the functioning of the state relied on the maintenance of normative gender roles. This reliance is visible in other ways as well, such as in connections between women’s fertility and the health of the state. To be a good citizen as a woman meant to live up to the value of fecunditas; in fact, the fertility of women in the imperial family symbolized the stability of the state (Hug Reference Hug2023). Take also the frequent rhetorical links between non-normative gendered behaviour and dangerous foreign influence (Olson Reference Olson, Masterson, Rabinowitz and Robson2015; Swancutt Reference Swancutt, Penner and Stichele2007). Especially potent examples include suspicion and disdain for the cross-dressing, eunuch galli (priests for the Phrygian goddess Cybele) (Mowat Reference Mowat2021) and the threat posed by tribades (simplistically, women who had sex with women). Roman writers posed tribadism as a degenerate Greek practice infiltrating Rome (Swancutt Reference Swancutt, Penner and Stichele2007).

How did the Roman state’s reliance on normative gendered behaviour impact the lives and worldviews of those in the provinces? To pursue this question, I characterize the gendered symbolic system linking state ideology to the lived experience and worldviews of individuals. Tracing a symbolic system is a means to access a culture’s internally coherent means of organizing the world and understanding their position in that world (Douglas Reference Douglas1966; Leach Reference Leach and Lenneberg1964; Robb Reference Robb1998; Turner Reference Turner and Helm1964). A symbolic system, argues Geertz (Reference Geertz and Geertz1973), lends structure to chaos, allowing meaning to emerge.

Several now-classic works in anthropology and feminist philosophy identify ways in which the body and sexual relations undergird understandings of the wider world. Broader metaphors for society can be found, for example, in the body’s symmetry and balance (MacRae Reference MacRae, Benthall and Polhemus1975), the stark divisions between inside and outside (Tilley Reference Tilley1999), the power of bodily fluids (Turner Reference Turner and Helm1964) and the danger in not being able to control bodily boundaries (Douglas Reference Douglas1970). Sexuality as metaphor can organize understandings of penetrability, boundedness, and controllability in terms of an individual’s relation to society (Grosz Reference Grosz1994; MacRae Reference MacRae, Benthall and Polhemus1975). Societal rules around acceptable sexual partners can organize rules in other aspects of life that seem to have little to do with sex—like, for example, which animals are pets and which may be eaten (Tambiah Reference Tambiah1969). While neither sexuality nor the body should be uncritically conflated with gender, gender systems are undeniably interlinked with both sexual relations and social understandings of the body. My symbolic focus lies in Roman gender norms and hierarchies, which were inseparable from sexuality and the body in Roman thought (Masterson et al. Reference Masterson, Rabinowitz and Robson2015; Surtees & Dyer Reference Surtees and Dyer2020).

Ortner (Reference Ortner1973) develops a typology of ‘key symbols’, basic in their centrality but complex in their meaning, at the heart of a society’s worldview. Her typology separates ‘summarizing’ symbols from ‘elaborating’ ones. A symbol is elaborating when it acts as a font from which other symbolic connections flow: it is ‘a source of categories for conceptualizing the order of the world’ (Ortner Reference Ortner1973, 1340). This sort of elaboration usefully describes the role of hierarchical gender dynamics in Roman life. The concept of men and women in binary opposition—and the interaction between them—provided an elaborating metaphor for diverse aspects of society.

I take a binary approach to gender here, but certainly not to deny gender complexity and fluidity in Rome. An ever-growing body of excellent scholarship on sexual and gender diversity in antiquity often engages explicitly with queer epistemologies that, by definition, plumb the tension between the normative and that which refuses to conform (Haselswerdt et al. Reference Haselswerdt, Lindheim and Ormand2023; Masterson et al. Reference Masterson, Rabinowitz and Robson2015; Surtees & Dyer Reference Surtees and Dyer2020). As Surtees and Dyer (Reference Surtees and Dyer2020, 13) argue with respect to the classical world, if hierarchical sex and gender binaries were as stable and natural as stated ideals would have one believe, ‘they would not require such constant upkeep’. My focus is the way normative Roman gender ideals, binary by definition, were maintained symbolically—and the impact of such gendered symbolic structures on far-reaching and sometimes unexpected areas of life. The lived reality of diversity beyond binaries enriches study of normative symbolic systems.

This study examines the way a binary gender dynamic was elaborated into a metaphor for the physical state of permeability versus impermeability. I label this physical state ‘permeability’ to apply the metaphor to physical materials. However, in research on gender, sex and the body in Rome, this state is more often referred to as ‘penetrability’. Research on Roman sexuality (and its intersection with gender norms) often implicates the so-called penetration model, which categorized acceptable sexual behaviour not simply by the sex or gender of a person’s partner but rather by whether one took the penetrating or penetrated role (Ormand & Blondell Reference Ormand, Blondell, Blondell and Ormand2015). The penetrated role was distinctly feminine and the penetrating role masculine—so while a man could acceptably penetrate another man, being penetrated as a man was a mark of femininity (Richlin Reference Richlin1993; Walters Reference Walters, Hallett and Skinner1997). Concepts of penetrability (permeability, in my terms) were therefore fundamental to Roman gender constructions, but the metaphor stretched beyond sexual activity. For example, this penetration metaphor explains the shame of battle loss, incarceration, or corporal punishment for Roman men as they lost the ability to control what happened to their bodies (Taylor Reference Taylor, Cornwell and Woolf2023; Walters Reference Walters, Hallett and Skinner1997). Kamen and Levin-Richardson’s (Reference Kamen, Levin-Richardson, Masterson, Rabinowitz and Robson2015) well-regarded reassessment of the penetration model fits with this broader metaphor as well: they argue that men who actively facilitated their own penetration (thus controlling what happened to their own bodies) were seen differently from men who seemed merely passively to accept penetration.

Unsurprisingly, this Roman construction of sexuality was closely linked to an ethic of conquering. Postcolonial and indigenous feminist theory, while developed for the modern colonial era, can be applied to conceptualize the implications of the Roman relationship between gender and permeability in the colonial context. This symbolic relationship reinforced boundaries between Roman (colonizer) and non-Roman (colonized). The most fundamental necessity of maintaining colonial control is to make those who are or will be conquered inherently other and transforming this othering into a natural dynamic such that the superiority of the colonizer is inevitable (Quijano Reference Quijano2000; Said Reference Said1978). Gender binaries usefully naturalize inferiority as they are mapped onto the colonizer–colonized distinction.

Through this process, indigeneity itself is feminized or treated as queer (Lugones Reference Lugones2007). The very state of having been conquered becomes feminine, subject to the rule of another. Through artistic and narrative depictions, vanquished indigenous men—and indeed entire conquered regions—are imagined as feminine (Nielson Reference Nielson2015; Slater Reference Slater, Slater and Yarbrough2011). This dynamic is evident in Roman ideology. Understanding the barbarian other as feminized allowed Rome to imagine its own well-reasoned, civilized masculinity as a positive influence on the overly emotive, irrational, and uncontrolled femininity of those they wished to conquer (Joshel Reference Joshel, Hallett and Skinner1997).

Such metaphorical relations certainly have practically felt implications, such as the sexual violence endemic to all modern colonial encounters—a devastating consequence of colonial logic linking conquest to sexual penetration (De Vos & Willman Reference De Vos and Willman2021; Simpson Reference Simpson2016). In the Roman era, such logic is visible in imagery of sexual violence in conquest iconography (Madden Reference Madden2023), including imagery of Rome (in the guise of a soldier or the emperor) dominating feminine personifications of conquered regions (Lopez Reference Lopez, Penner and Stichele2007; Ramsby & Severy-Hoven Reference Ramsby and Severy-Hoven2007) (Fig. 1). Sexual violence also played a role in Roman narratives of conquest, such as the story of the Boudican revolt in Britain, ostensibly spurred by Roman soldiers’ rape of Boudica’s daughters (Tac., Ann. 14.31).

Figure 1. Imagery depicting the provinces as conquered women. (Left) Reverse of a Judea Capta coin. Titus towers over a seated Judea (right). Illustration by author, after RIC 2.1 (167, p. 71); (Right) Gallia as a seated woman (with sheath empty showing her pacification) on the breastplate of the Augustus of Prima Porta, Italy. (Photograph of plaster replica taken by author at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK.)

I wish to catch sight archaeologically of this Roman gendered symbolic system. Because of the centrality of penetrability, a logical place to start is the literal permeability of physical materials. Did people’s understanding and use of different physical materials reflect the elaboration of this gendered metaphor?

This question aligns with other archaeological work tracing gender symbolism, such as associations of masculinity (or else fertility) with standing stones (Insoll Reference Insoll2015, 174–83); sex and gender symbolism in the material dimensions of African iron smelting (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2009); and the symbolic formulation of ceramic pots as gendered people (Bray Reference Bray and Fogelin2008; Insoll Reference Insoll2015, 225–9). Here, I pursue a hypothesis related to material categories: metal, clay, stone, glass and bone. The symbolic nature of material categories is indeed a topic with which archaeologists have engaged (Boivin & Owoc Reference Boivin and Owoc2004; Cousins Reference Cousins2014; Insoll Reference Insoll2015; Isaakidou Reference Isaakidou2017). One potent example from the classical world is the use of lead for curse tablets, related to lead’s ‘weight, colour, and chill’ (Lamont Reference Lamont2021, 38) that linked it to death and binding. Indeed, there is limited evidence for gendered symbolic connections to materials in the Roman world—most notably amber’s and jet’s links to women (Eckardt Reference Eckardt2014, 105–16).

If the Roman gendered symbolic system provided a path to categorize materials like it did people, what material properties might be associated with masculinity versus femininity? I study this question through the material categories of votive offerings in Britain and Gaul. My results indicate that by the Roman period, women were associated with permeable or breakable materials and men with durable, impermeable metal.

Votive offerings as symbolic expression

While my focus is Roman-period offerings, people certainly offered objects to the gods in Iron Age Britain and Gaul as well. Late Iron Age offerings are found in built sanctuaries; in rivers, springs and lakes; and in structured deposits across the landscape (Bataille & Guillaumet Reference Bataille and Guillaumet2006; Crease Reference Crease2015; Demierre et al. Reference Demierre, Bataille, Perruche, Barral and Matthieu2019). Assemblages exhibit more diversity in the centuries immediately before conquest than in the earlier Iron Age, which has been posited to be associated with a greater diversity of offerers (Demierre et al. Reference Demierre, Bataille, Perruche, Barral and Matthieu2019; Goussard Reference Goussard2022, 857–65). Assemblages included weaponry, tools, jewellery, coins and metal vessels as well as ceramics, organic materials like nuts, and faunal remains (Arcelin & Brunaux Reference Arcelin and Brunaux2003; Wait Reference Wait1986). Post-conquest, more Roman forms of offering are evident at sanctuary sites, including purpose-made ex-votos: statues, altars, plaques, figurines and miniatures (Goussard Reference Goussard2022; Kiernan Reference Kiernan2009). The range of personal objects offered also widened during the Roman period to include a diversity of jewellery types; toiletry items like combs, palettes and tweezers; dice and gaming counters; and other miscellaneous objects (Rey-Vodoz Reference Rey-Vodoz and Brunaux1991; Woodward 1992, 66–80).

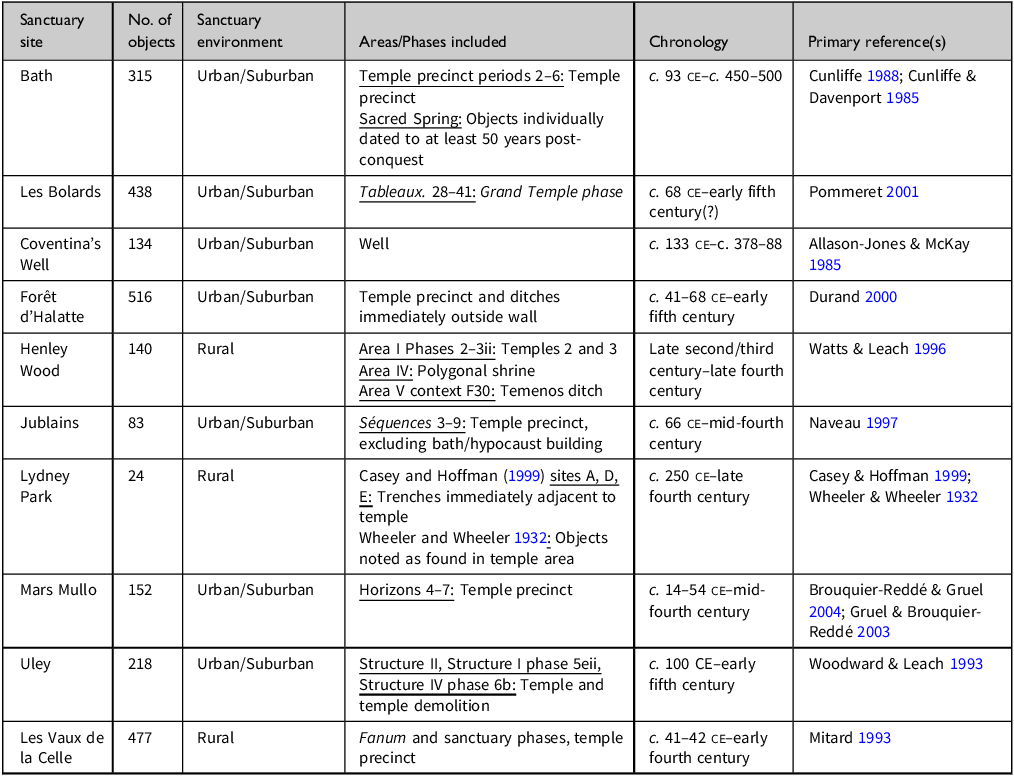

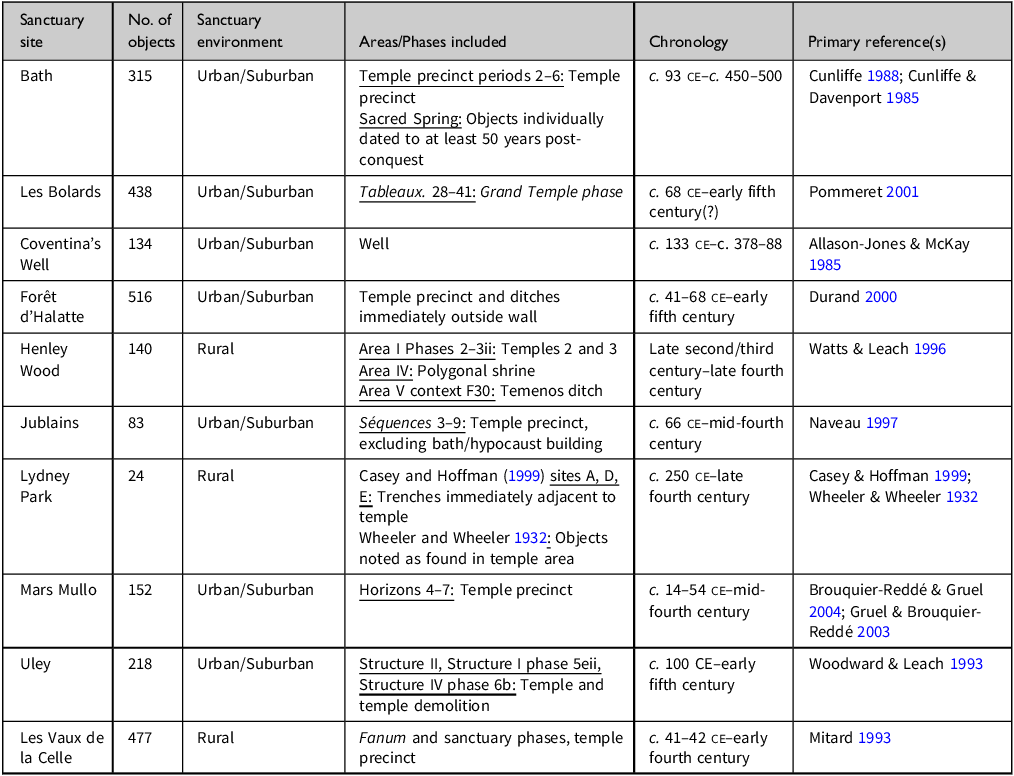

This diversity of offering types in the Roman period proves that sanctuary visitors generally had the freedom to choose the type of object they would offer. Economic status was not a barrier to participation; at the same sanctuaries where some offered expensive statuary or inscribed stelae, most left cheap trinkets, broken tools, or even manufacturing waste (Wigodner Reference Wigodner2022, 360–65). Because both men and women participated, offering assemblages lend insight into gendered decision-making as well as the way gendered worldviews changed post-conquest. My assemblage numbers about 2500 objects (excluding coins and most vessels) offered during the Roman period at 10 sanctuaries: five in Britain and five in Gaul (Fig. 2; Table 1).

Figure 2. Locations of sanctuary sites.

Table 1. List of sites. For more detailed information about chronology and areas/phases included, see Wigodner (Reference Wigodner2022, 111–40).

Sanctuaries were partially chosen for inclusion based on chronology. In the decades immediately after Roman annexation, most offerers would have been born before the onset of Roman control. This initial generation’s worldviews would necessarily have been shaped by memories of conquest, and those in immediately subsequent generations would be affected by familial memory of pre-conquest life. In addition, in the first decades post-annexation, instability caused by recovery from war and the establishment of Roman administration make patterns more challenging to identify. For this reason, I include only offerings associated with sanctuary contexts beginning 50–100 years after Roman annexation (with annexation marked at c. 50 bce in Gaul and 43 ce in Britain). This length of time ensures that Roman influence had a chance to reach all areas of the provinces, even if the form and intensity of that influence varied (Woolf Reference Woolf1998), and that sanctuary visitors had no (or limited) memory of a time before conquest. This chronological filtering limits included sanctuaries to those with excavation records linking finds to dated phases, or else to those first constructed in the appropriate period.

Because individuals offered their own possessions alongside purpose-made ex-votos, it is not necessarily the case that every personal object found within or around a sanctuary was purposefully offered: objects like earrings may have been lost accidentally, especially at sites where hostels, baths, or theatres were built alongside temples. Bathing or attending the theatre may well have had a ritual component, but it can be reasonably assumed that a far larger proportion of objects were lost rather than purposefully offered in contexts outside temples, shrines, and temple courtyards. I therefore include only objects known to have been found in temple precincts, or else objects from sites where all excavation occurred within a temple or enclosed temple courtyard. I also include objects confidently identified by excavators as having been found in offering caches: generally at courtyard entrances (as at Jublains: Naveau Reference Naveau1997, 190) or deposited in trenches abutting courtyard walls (as at Forêt d’Halatte: Durand Reference Durand2000, 103–4). The dataset includes every object catalogued from each of these appropriate contexts (see Table 1).

The 10 sanctuaries include both urban (or suburban) and rural sanctuaries of different sizes—from the monumental sanctuary complexes of Bath, Lydney Park and Les Vaux de la Celle to smaller shrines like Coventina’s Well and Forêt d’Halatte. Some also have more direct connections to the Roman state than others. Coventina’s Well, for example, is located at Carrawburgh Roman fort, and the Mars Mullo sanctuary is directly connected to the imperial cult. This diversity in site types and locations ensures study of the behaviour of more diverse offerers.

Representations of men and women across materials

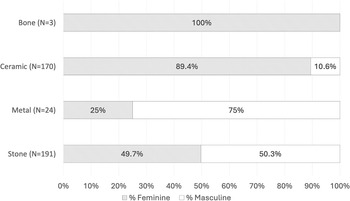

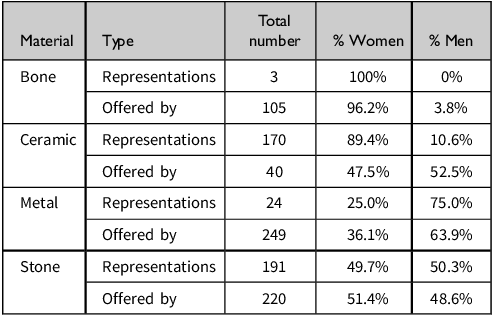

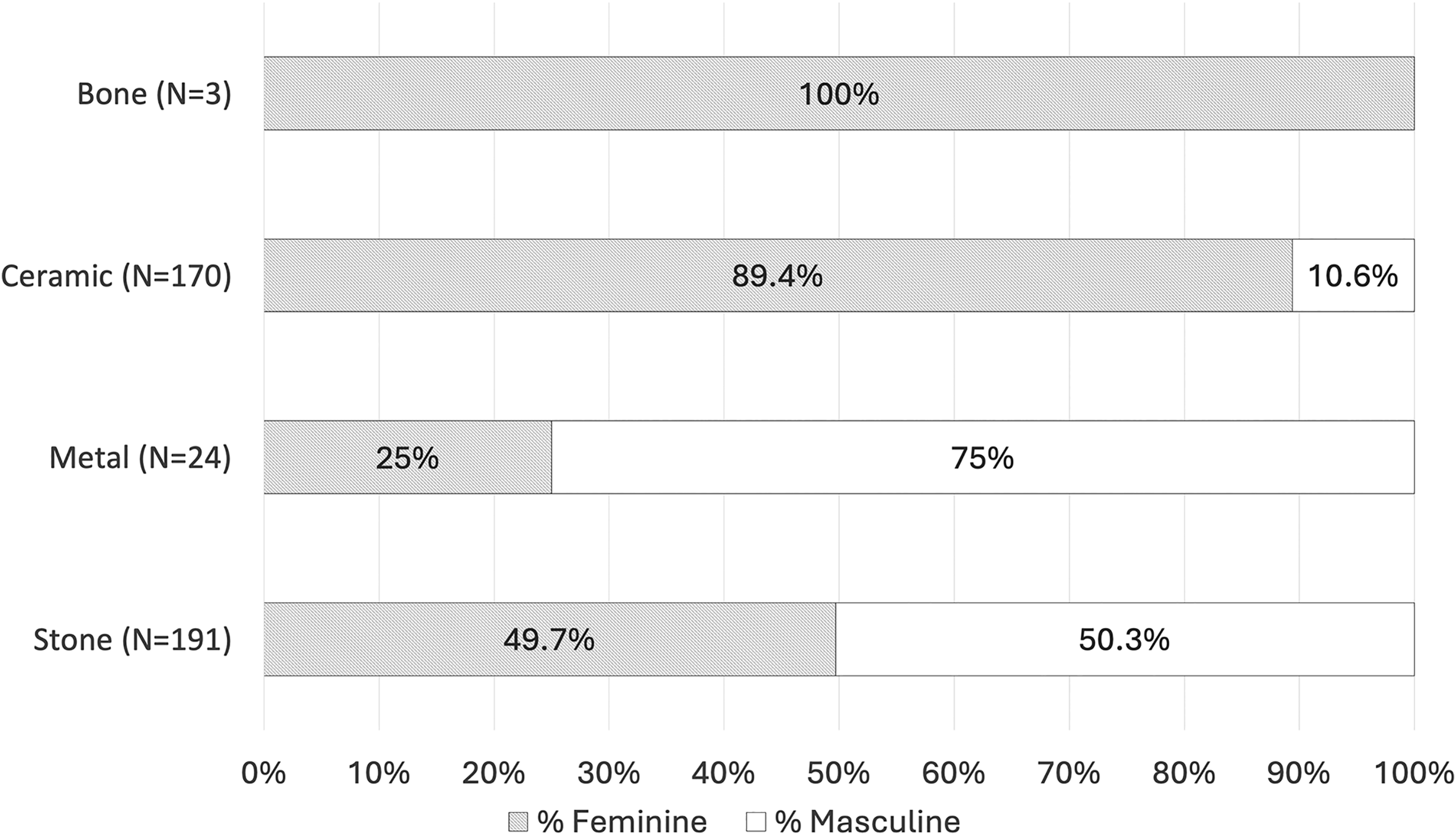

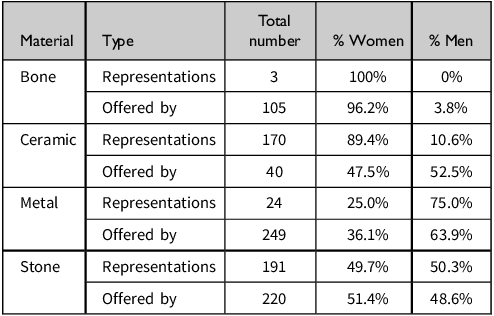

I first examine whether feminine or masculine figures (both humans and deities) were visually represented at different rates in different materials: which were understood as appropriate to depict whom? Most of these representations are purpose-made ex-votos: figurines, plaques, altars, stelae and statues (Fig. 3). However, 4 per cent of these 388 representations take the form of men or women decorating adornment items, or decorative elements on boxes, vessels and the like. Bone and ceramic representations clearly favour women—100 per cent (N=3) and 89 per cent (N=170) women respectively—though the very limited number of bone representations makes this finding tentative. Most ceramic representations take the form of mould-made figurines, the majority of which depict goddesses. While the sample size of metal representations is not large (N=24), these clearly favour men and gods (75 per cent). Stone representations are quite evenly split between masculine and feminine (Fig. 4). Footnote 1

Figure 3. Clay Mother Goddess (left) and Venus (centre) figurines. (Photographs: author, Musée de Jublains, France.) Bronze Mercury figurine (right). (Photograph: Caroline Léna Becker, Musée Saint-Raymond, France.)

Figure 4. Proportions of masculine and feminine representations by material.

Men’s and women’s offerings across materials

These findings suggest that women and goddesses were more appropriate to be represented in clay (and possibly bone as well), while metal was more appropriate for men and gods. However, gendered representations comprise only a small proportion of the overall offering assemblage. Individuals also offered personal objects and ex-votos like tablets and plaques which can sometimes be linked to the offerer’s gender. Studying material patterns in objects offered by men and women can supplement the ‘gendered representation’ evidence by speaking to how these symbolic connections were translated into other parts of an individual’s life or decision-making.

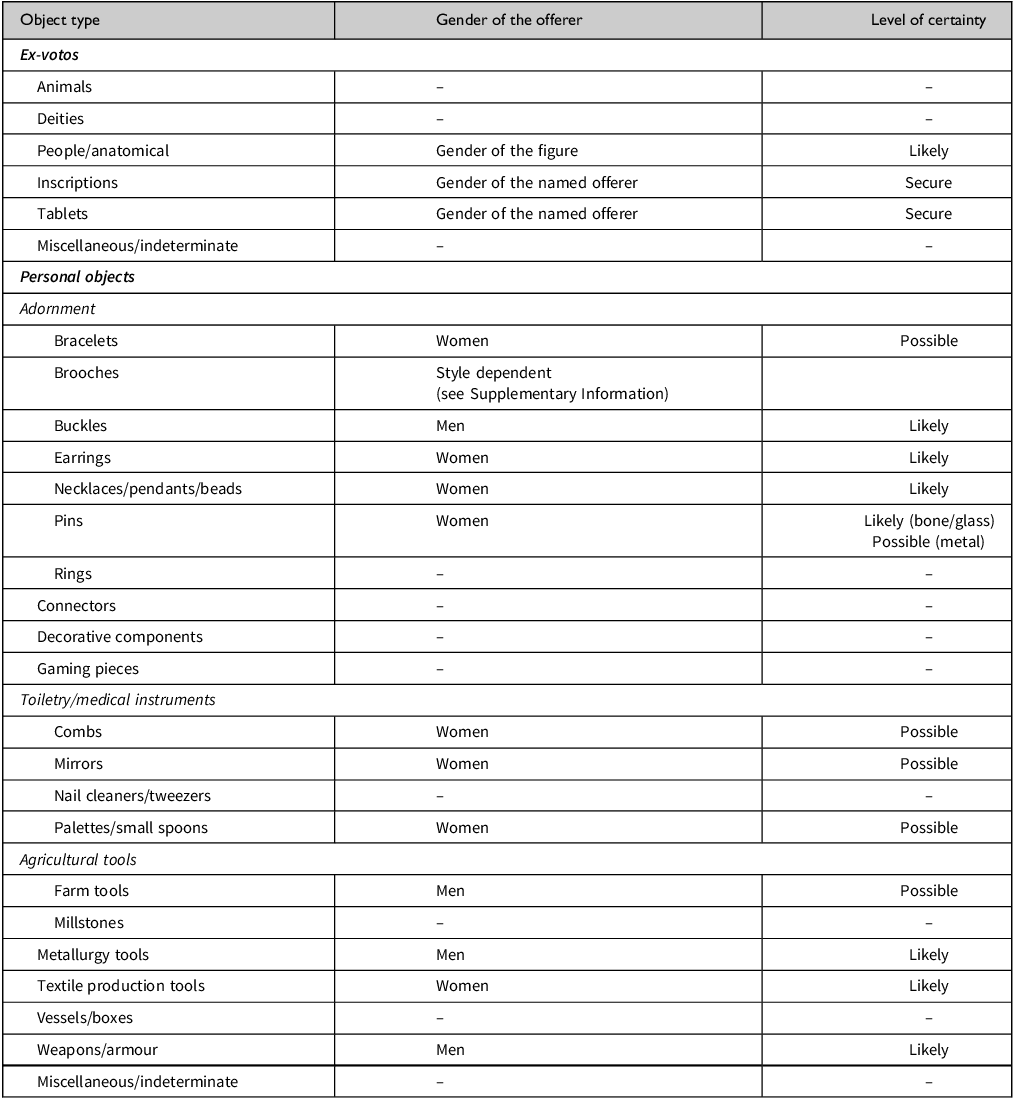

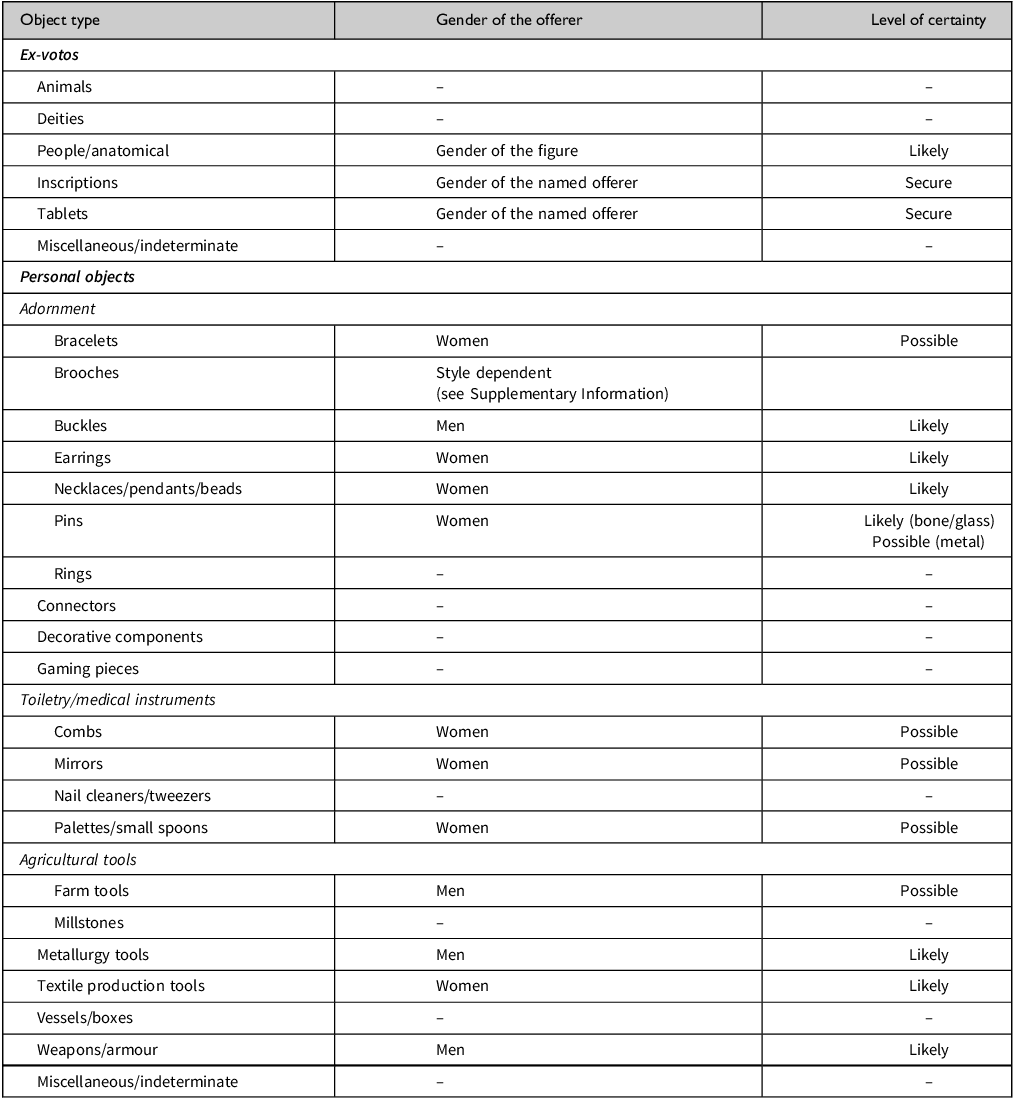

Determining whether a man or woman was more likely to have offered a certain type of object is not straightforward. Objects inscribed with the offerer’s name can be securely gendered, but no other objects can be gendered with absolute certainty. Even when evidence points to a certain object type as generally associated with men’s or women’s behaviour, such associations are rarely absolute (Allason-Jones Reference Allason-Jones and Rush1995; Allison Reference Allison2008). I utilize a combination of textual evidence, imagery and archaeological evidence (often from sexed burials) to determine which object types can be gendered. Allison (Reference Allison2008) advocates for ascribing levels of certainty to artifact–gender attributions to take such complexities into account. I do so by describing attributions as secure, likely, or possible based on the preponderance of evidence. Table 2 summarizes gender attributions for all offering types; see Supplementary Information for detailed justifications.

Table 2. Summary of gender attributions for offering types. See Supplementary Information for detailed justifications.

The simplest explanation for the offering of a gendered personal object is its owner was the offerer: a woman brought her spindle whorl to give to the deity, for example, and a man brought his axe. Even when, as likely sometimes occurred, a family member or acquaintance offered an object on behalf of another, that object would still have been symbolically associated with the original owner. One might posit that individuals sometimes made offerings associated with the deity’s identity even when the objects were not associated with their own gender (such as offering weapons to a martial deity). However, this seems most likely in the case of votive miniatures. If miniature spears, for example, were on sale at a sanctuary because they appealed to the deity, a woman may certainly have chosen to offer one even if she was unlikely to use a spear in life. I therefore exclude these votive miniatures from analysis. With respect to objects used in daily life, though, it is unlikely that a woman would have purchased a full-sized axe, or a man a spindle whorl, solely to make an offering.

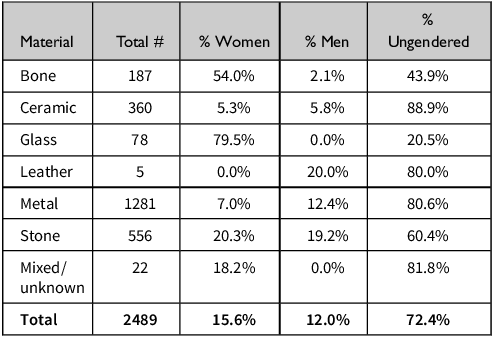

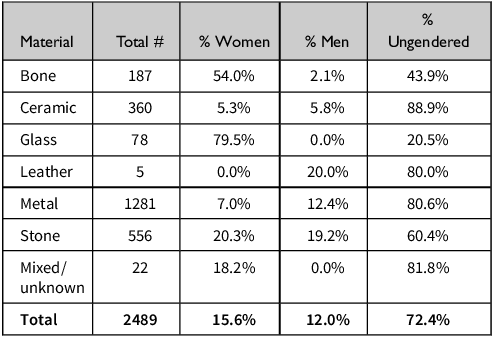

Table 3 reflects objects gendered at all levels of certainty (possible, likely, and secure). Excluding the possibly gendered offerings shifts proportions slightly but does not change the patterns discussed. The proportions of materials offered by men and women are contextualized by including the proportions of ungendered offerings as well (total N=2489). While fully 72 per cent of all offerings are ungendered, over half of bone offerings (N=187) can be gendered. Most of these are hairpins, with a smaller number of needles, combs, and other objects more associated with women. The majority of all glass offerings (N=78) were women’s as well (mostly beads), even with ungendered objects included. Men and women offered relatively similar proportions of ceramic (n=360) and stone (N=556) offerings, and ungendered offerings in these materials outnumber gendered ones in any case. While men’s metal offerings outnumber women’s, ungendered metal offerings are far more common.

Table 3. Gendered and ungendered proportions of offerings by material.

Summary of results: gendered representations and offering decisions

Considering gendered representations and gendered offerings together (Table 4) provides the strongest means to analyse gendered symbolism linked to material.

Table 4. Material types for gendered representations and gendered offerings.

Glass is excluded from Table 4 because the dataset includes no gendered representations in glass. In the case of bone, metal and stone, the proportions of masculine and feminine representations follow relatively closely the proportions of men’s and women’s offerings. While the small number of bone representations limits the weight of that particular accord, it is certainly interesting that all three are feminine, given that gendered bone offerings were almost entirely women’s. The skew towards men in metal representations lends significance to the skew towards men in gendered offerings despite the large number of ungendered metal offerings—and men’s overrepresentation is even more meaningful given a dataset-wide skew towards women in both representations and offerings: women’s offerings make up about 57 per cent of the gendered assemblage (N=681), and 66 per cent of the gendered representations (N=388) are feminine.

Stone objects are evenly split in both gendered representations and gendered offerings. In fact, this even split could be interpreted as a slight skew towards men, given the dataset-wide skew towards women. The difference between the proportion of stone objects offered by women (51 per cent, N=220) and the proportion of all objects offered by women (57 per cent) is not statistically significant (p=0.1389), but the proportion of masculine representations is significantly higher in stone offerings (50 per cent) than in the overall assemblage (34 per cent) (p=0.0002). While this overrepresentation of men in stone should not be overlooked, this gender–material relationship is the weakest of those examined here.

In sum: while ceramic objects were not offered more often by men or women, ceramic representations significantly favour women. Adding to these material–gender connections is the preponderance of women’s offerings in bone and glass, suggesting that these materials were more linked with women than men. Metal, on the other hand, skews towards men in both representations and gendered offerings.

For the most part, these patterns hold across different types of sites. Categorizing sites by location (urban/suburban versus rural) does cause a distinction with respect to ceramic gendered offerings that does not exist across the entire dataset: they skew towards women in rural sanctuaries and men in urban/suburban sanctuaries (though the sample size is small—10 in rural sanctuaries and 30 in urban/suburban). However, the general pattern holds for gendered offerings across urban and rural with respect to bone, glass and metal and for gendered representations in bone, metal and stone (though ceramic representations cannot be compared because none are catalogued at rural sanctuaries). The three sanctuaries most closely associated with the Roman state are Coventina’s Well (at an army fort), Mars Mullo (an imperial cult site) and Jublains (a civitas capital). Women’s participation in offering ritual did tend to be lower at these sanctuaries than those less associated with the state (Wigodner Reference Wigodner2022, 335, 377), but the material patterns are relatively stable. With respect to the ‘offered by’ data: bone, glass and metal follow the overall patterns at state-associated sites, while ceramic and stone favour men despite being split relatively evenly overall. The ‘representations’ patterns hold entirely.

Permeable and impermeable offerings

My hypothesis regarding gender-material associations was informed by figurine studies. Ceramic figurines produced in Gallic workshops favour goddesses over gods, with Venuses and Mother Goddesses especially common (Bémont et al. Reference Bémont, Rouvier-Jeanlin and Lahanier1993). In a study of figurines in Roman Britain, Fittock (Reference Fittock2017) finds that while ceramic figurines more often represent goddesses, women, and children, bronze figurines more often represent gods and men. In fact, Fittock (Reference Fittock2017, 192) turns to material symbolism to explain this result, positing that men and gods were represented in metal due to its strength and durability (especially given the martial aspects of Mars and Mercury, two of the most frequently depicted gods), while women, children, and goddesses were formed from more breakable clay in symbolic association with the fragility of life and dangers of childbirth (especially given the preponderance of Venuses, Mother Goddesses and children).

My results with respect to metal and clay gendered representations parallel these findings, even with a wider range of object types—beyond figurines—considered. Bringing in materials besides clay and metal encourages a consideration of symbolism regarding material properties beyond fragility. As discussed above, Roman masculinity was marked by impenetrability or impermeability, both physically and with respect to agency or power: the strongest men gave orders and did not receive them. This masculine impermeability was defined in contrast to the penetrability or permeability of femininity, which could be associated with sex itself, the dangers of childbirth, and the ideal that their behaviour be controlled by men. Within such a symbolic system, it is easy to see how a breakable ceramic object could become associated with femininity or the female body.

Breakability is one form of permeability, but other material qualities can align with permeability as well. Glass is certainly breakable, but it is also permeable in its translucence: light can sometimes shine through glass. While bone is not particularly fragile, bone and clay are permeable in their porousness: unlike metal, they take on moisture when submerged. The gendered patterning in offering materials seems to suggest that the individuals making the offerings possessed worldviews that incorporated this aspect of the Roman symbolic system.

These patterns cannot be explained by some sort of differential gendered access to wealth. Both men and women offered the most expensive materials like gold and silver, and men and women both commissioned expensive monumental offerings like altars and statues (Wigodner Reference Wigodner2022, 361–5). Metal figurines may have been more expensive than clay ones, but 53 per cent of men’s metal offerings (N=159) were tools or manufacturing waste: working men clearly had access to metal to offer. In fact, this is the second dataset for which I have found this to be the case: in a study of Gallo-Roman healing votives, I similarly found that men were overrepresented in metal. Most metal healing votives took the form of small and thin (and therefore likely inexpensive) cut bronze sheets (Wigodner Reference Wigodner2019, 632).

My findings are suggestive and serve to illustrate the potential of symbolic analysis in this vein. However, definitively proving ascription in Britain and Gaul to a Roman gendered symbolic system focused on permeability would require more data, including data outside of sanctuary contexts. This study’s small sample sizes hamper analysis, including with respect to chronological patterns: while understandings of gender symbolism may have changed over the course of my study period, most objects cannot be dated narrowly enough to study this question. Preservation provides another barrier: offerings made of wood (a permeable material) cannot be studied because they rarely preserve. Stone presents a challenge as well: while I find little correlation between stone and gender, it is possible that symbolism was specific to different stone types (Dasen Reference Dasen, Dasen and Spieser2014). Some stone is porous or breakable, and some minerals allow light to pass through. However, most records of excavated objects do not provide detailed enough information to explore more specific patterns.

While the data on gendered representations is convincing on its own, the materials of gendered offerings were undoubtedly shaped by practical factors outside the symbolic. There are some convincing data points that material was a deciding factor in which objects men and women offered. For example, copper-alloy beads were not uncommon in the Roman world, but only glass, stone and bone beads are present at these sanctuaries. However, for the most part the ‘offered by’ patterns may be explained by the types of objects men and women used in their daily lives. For example, the most common bone objects across sanctuaries were hair pins (N=73) and gaming counters (N=55), which are also some of the most common bone objects found in the Roman period in general. Footnote 2 That said, I would argue that practicality and symbolism can reinforce each other: did the common-ness of glass beads for women contribute to the maintenance of women’s association with fragility and translucence? Did the masculinity of metal mean more tools were produced in metal than strictly necessary? Awls and styli, for example, could easily be made of bone rather than metal, and yet metal ones are more common in the region. Footnote 3

Permeability and the impact of colonialism

My analysis suggests that the worldviews of those making these offerings reflect a Roman gendered symbolic system in which masculinity was symbolically associated with the strength and impermeability of metal while femininity was associated with the permeability of glass (fragile and translucent), bone (porous), and clay (breakable). This finding must be contextualized with respect to the colonial environment in which offerings were made.

The most obvious question is whether these material-gender associations were new in the Roman period or whether they already existed in the Late Iron Age (LIA) (pre-conquest). Direct comparison with LIA offering assemblages is not an option because LIA personal objects found in offering contexts (excluding the vessels and coins I exclude from my Roman-era study) are almost always metal (Bataille Reference Bataille, Reddé, Barral and Favory2011)—the same diversity of materials does not exist. However, it is likely that both men and women offered these metal objects in the LIA because both weapons and jewellery were commonly offered (Demierre et al. Reference Demierre, Bataille, Perruche, Barral and Matthieu2019). While plenty of exceptions exist, weapons and some types of jewellery are the only types of objects consistently correlated with male and female burials, respectively, across the region in this era (Belard Reference Belard2014; Harding Reference Harding2016, 220–2). A similar challenge plagues evidence of gendered representations in the Iron Age because they are almost exclusively preserved in metal and stone (making comparison with materials like clay and bone impossible) (Allen Reference Allen2021). The association of males with weapons (which could puncture or penetrate) could also be evidence of an Iron Age gender-permeability connection. However, more males were buried without weapons than with them, suggesting weapons were associated not with masculinity in general but with a particular type of (high-status?) masculinity (Belard Reference Belard2014).

What of the materials of grave goods buried with men versus women? Of course, there are serious challenges with assuming gender identity based on skeletal remains—both because sex determination is not an exact science and because sex and gender do not always correlate (Arnold Reference Arnold2016). In addition, most LIA graves either lack any grave goods or cannot be sexed (Belard Reference Belard2014; Lamb Reference Lamb2016). Despite these problems, grave goods are the best option to systematically examine LIA gender-material connections.

Across northern Europe, glass and amber beads are much more commonly found in female than male graves (Harding Reference Harding2016, 229–30; Pope & Ralston Reference Pope, Ralston, Armada and Moore2011, 403). In addition, some regional material associations with sex can be identified. In Auvergne, while iron bracelets were found almost exclusively in male graves, copper-alloy bracelets as well as jewellery made of glass and organic materials were more frequent in female graves (Mennessier-Jouannet et al. Reference Mennessier-Jouannet, Blaizot, Deberge, Nectoux, Barral, Dedet and Delrieu2010, 248). A study largely focused on northeastern Gaul found a similar pattern in brooches: males were more associated with iron brooches and females with copper-alloy ones (Charignon Reference Charignon, Augereau and Trémaud2024). In Middle Iron Age eastern Britain, a small sample size of sexed graves (N=10) suggests a possible association of males with shale armlets and animal bones (Legge Reference Legge2021, 117). In a regional comparison, Jump (Reference Jump2023) suggests that in Yorkshire, pottery was more common in female graves and bone in male graves (187), while in Dorset pottery appears more in male graves (290).

In sum, while there are some overlaps between Iron Age sex–material relationships and my findings in the Roman era (such as females being associated with glass beads), the limited evidence does not reflect the broader gender-permeability system I suggest for the Roman era. Given the limitations of the physical evidence, it becomes attractive to seek out written evidence for the existence of gender-permeability symbolism in the LIA. There are no specific mentions of gendered associations with materials in historical sources; the closest available are mentions that Gallic men wore more (metal) adornment than classical writers found acceptable (Diod. Sic. V 27.3). The next step is to examine historical sources for worldviews around gendered permeability more generally. For example, Diodorus Siculus observes that Gallic men commonly had sex with other men—and that it was so accepted as to be an act of respect or hospitality (Diod. Sic. V 32.7). With this observation he certainly implies that masculinity was not as connected with impenetrability in LIA Gaul as it was in Rome.

Discussion of Celtic women leaders may also shed light on the relationship between gender and permeability. By depicting Celts as willing to be led by women, classical writers suggested a dangerous reversal of the Roman gendered flow of power. For example, Tacitus discusses Boudica, who inspired Britons to rebel in response to Roman cruelty: ‘with Boudica, a woman of royal descent, as their leader (for they do not make distinctions based on sex in their right to rule), all together they took up arms … In their rage and victory, this savage race spared no manner of barbarity’ (Tac., Agr. 16). Such passages directly relate British barbarity to the leadership of women: it was dangerously foreign that women’s orders could permeate the men they ruled.

None of the available evidence, either archaeological or historical, suggests the presence of a strong gender-permeability connection in Britain or Gaul in the centuries leading up to Roman conquest—which could mean this symbolic system was introduced to the region by Rome. However, it is completely unsurprising from a postcolonial perspective that classical writers would describe men they wished to conquer (or had already conquered) as unacceptably permeable: describing men in this way served to justify conquest and colonial rule. Regardless of whether this symbolic system existed pre-conquest or was introduced by Rome, it is certain that this question of gendered permeability was loaded with meaning specific to the colonial environment. Discussion of masculine permeability went beyond the political (taking orders from women) to the personal (habitual penetration by other men). This means that my results, while limited, are suggestive of a deep, perhaps unconscious ascription in this colonized region to a worldview that kept women in their place with respect to men and kept locals in their place with respect to Rome.

This should not be read as evidence for passive capitulation, though. Adoption of a Roman worldview certainly did not end active resistance to Roman rule, and it does not necessitate that people understood themselves as Roman. Rather, it means that a Roman symbolic system shaped how they understood the world and their place in it. The way individuals behaved within such a worldview would have continued to be diverse, dependent on individual identity and personal experiences. Many may have felt the connection between Roman-ness and masculinity very personally, for example, but while some men may have aligned with Roman values to shore up their masculinity, others may have sought alternative definitions of masculinity through indigeneity (or even understood displays of such masculinity as resistance).

Conclusion

Symbolic comparison across the colonial divide is unavoidably difficult. In the Roman period, we possess a large body of written work to support our identification of a symbolic system; such evidence is unavailable (at least from an emic perspective) for the Iron Age. In this case, it is also impossible to develop a direct material comparison between Iron Age and Roman: it was not typical to offer images of people or deities in the Iron Age, and the challenges of gendering object types are even more pronounced in this earlier period. I find evidence post-conquest for a gendered symbolic system of permeability and control reflected in offering materials. This worldview permeated a range of decision-making processes, from the production of figurines of different materials to their purchase and subsequent offering to the types of personal objects that men versus women considered suitable for offering. Regardless of whether this symbolic system was introduced by Rome or existed in the region pre-conquest, the implications of a gender-permeability metaphor with respect to conquest and colonialism mean that ascription to such a worldview was uniquely fraught in colonial environments. The evidence points to the insidious power of colonizing worldviews, but I am not arguing for some passive response to a top-down imposition of Roman values. This gendered worldview informed—but certainly did not dictate—decisions and self-identity.

Questions of gender are central to colonial power, and not only because men and women experienced and negotiated colonial contexts differently. Gender takes on a critical role in naturalizing the inferiority of the conquered as gender dynamics fuse with racialized power dynamics. There is value in understanding how such dynamics impacted how those in colonized spaces understood their place in the world. We can study day-to-day actions under colonialism archaeologically—and we do—but without studying the symbolic systems underpinning these actions we are only accessing part of the picture. Here, I develop a methodological approach to address these challenging questions by bringing to bear symbolic thinking: using elaborating metaphor (which organizes how people categorize their world) as a source of hypotheses for archaeologically visible material correlates. The physical traits of materials have—for obvious reasons—been an especially popular path for archaeologists pursuing symbolic approaches. By connecting material symbolism to a more systems-level approach, we can go further, linking material remains to fundamental worldviews in these complex colonial environments.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material may be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774325100309.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the School of Anthropology and the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Arizona. I would like to thank Lars Fogelin, Alison Futrell, and Steve Kuhn for their advice and insights, Emma Blake and Catherine Young for reading and discussing earlier versions of this article, and two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive comments.