Introduction

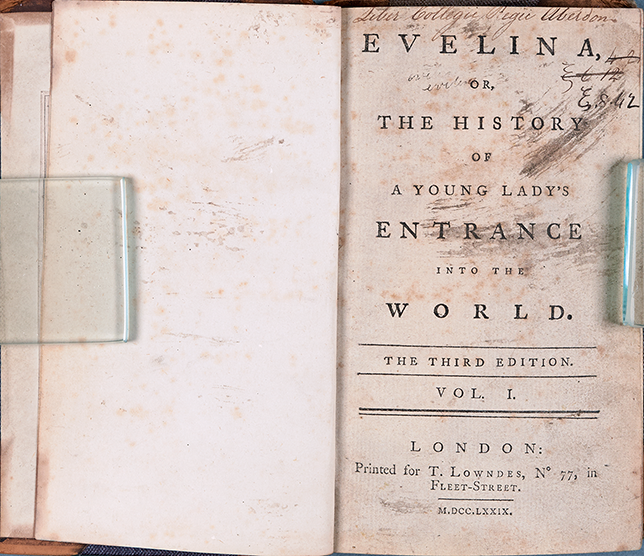

In the summer of 1779, a young theology student called Charles Burney (1757–1817) wrote from Aberdeen to his older sister Frances (1752–1840) in London. His subject was the local reception of her debut novel, Evelina: Or, a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World, first published in London by Thomas Lowndes in January 1778. Charles’s description of Evelina’s journey around Aberdeen is one of those first-hand testimonies which can, if properly contextualised, change how we think about both literary history and the history of reading.

Evelina is in Aberdeen – I have had it, from a Circulating Library, & have lent to my two angels, the Miss Willox’s – The Miss Gordon’s – & their Father & Mother – to Dr Gerard & Family – & now a Mrs Paul has it; an aunt of my Charmers as need I name them. I cannot tell you half the fine things which have been said about it – They are all in raptures with it – & all longing to see you –

Dr. Gerard, the Professor of Divinity – think of that! – has read it, & admires it of all things! He doats upon Madame Duval –

Miss Gerard is fond of Miss Mirvan – the Youths of that family have not read it yet.–

Mr Gordon, the Professor of Philosophy, read it through twice – He thinks Sir Clement the best drawn & supported Character –

Before I return it, I shall lend it all around: to all the sweet Creatures, of which this Town is full.

Miss Willox is very fond of Evelina, & she and my lovely Jessy admire the Branghton Family.

But the Captain is my adorable Jessy’s favourite – she says that she almost killed herself with laughing –

Mrs Willox is very fond of Mr Villars – Mr Willox has not read it.

Mr Gordon laments that the meeting between Sir John Belmont, & Mr Villars was not made the subject of another Letter – He says, he is sure that Miss Burney’s pen would have made a great deal of it –

Every body is surprised at the Performance, however: – I prefixed the little sonnet, which I gave you some time since, to the set which I lent about. That likewise had its admirers – I addressed it, ‘To the Female Reader!’Footnote 1

In this Element, I use the above testimony, alongside other sources, to make several claims about Charles Burney, Frances Burney, and more broadly the ways in which gender, class, and kinship could inflect eighteenth-century reading experiences. In doing so, I model a process I call ‘3D reading’, which unites methodological approaches from literary studies, biography, bibliography, and the history of the book to generate a deeper understanding of late eighteenth-century reading practices.

Critical Context

What, where, when, how, and why did eighteenth-century readers read? In recent years, the desire to reconstruct reading experiences of the past – an objective which James Raven calls ‘the most significant and challenging dimension of the history of books’ – has generated numerous methodological approaches across the field of eighteenth-century studies. Some scholars suggest that reading practices can be understood with reference to the ‘manners of reading’ outlined within instructional literature.Footnote 2 Others interrogate material traces of reader interaction with extant textual artefacts to offer clues as to how they were used.Footnote 3 Most agree that accounts of individuals’ private reading practices gleaned from diaries, letters, and other manuscript sources remain crucial.Footnote 4 Some collaborative digital projects harness the capabilities of crowdsourcing, web-crawling or text-mining to code, model, and analyse such accounts in new ways,Footnote 5 while others draw on the archives of eighteenth-century libraries or booksellers to develop data-driven visualisations of local, regional, and national reading habits.Footnote 6

The ‘transformative capacity’ of reading is notoriously difficult to gauge.Footnote 7 For the most part, scholars still endeavour to do so by examining ‘private and critical’ contemporary reader responses drawn from letters and diaries.Footnote 8 Such an approach, however, raises questions around not only representativeness but also reliability. As Katie Halsey notes, life writing is an opaque, slippery, and complex genre.Footnote 9 When self-reporting ways in which a text has transformed them or others, writers may pursue multiple agendas – flattery, spite, or self-promotion, for example – which compromise the reliability of their accounts. As I show in the coming pages, a young man attempting to promote his own intellectual gifts may well declare that he is ‘not in general fond of Novels’, but other sources – especially the poetry he composed – may tell a different story.

One way to circumvent the problem of opaque or misleading reader testimony is to combine several disciplinary methodologies and use them to hold one another to account: an approach I term ‘3D reading’. This Element attempts to model such a process. I argue that by constructing a rich multidimensional case study of one unusual reader’s relationship with one extraordinary text, we can gain an enhanced sense of the forms which readerly transformation may have taken. Deidre Shauna Lynch has recently shown how, during this period, ‘literary reading became subject to new expectations of affective obligation and dilemmas of affective entanglement’.Footnote 10 This Element follows Lynch and others in centring the affective dimensions of eighteenth-century reading experiences, but dives deeper into one case study than traditional forms of academic publication will generally permit. The space allowed by the unique form of the Element (or ‘minigraph’) allows me to tell my story from a number of archival and theoretical angles.

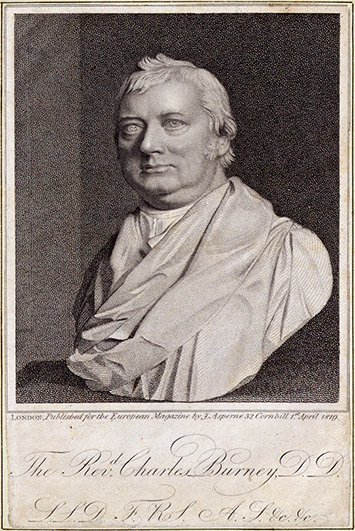

My reader of choice is the young man who would later in life be known as the Rev. Charles Burney D.D.: schoolmaster, author, critic, clergyman, bibliomaniac, and notorious thief. Throughout his sixty years, Charles Burney demonstrated an intense acquisitive relationship with material texts, both elite and ephemeral, in manuscript and in print. More accurately termed logomania than bibliomania since it was not restricted to codices, his condition found one expression in the best-known event of Charles’s life: his teenage expulsion from the University of Cambridge in 1778 for stealing ninety-two rare books from the University Library, after which he was exiled to King’s College Aberdeen to finish his studies and live down his disgrace. The second achievement for which he is commonly known is the vast personal library purchased after his death in 1817 for the British Museum, part of which, as Gale Cengage’s Burney Collection of Newspapers, now underpins an enormous amount of scholarly research into the history, literature, and culture of early modern Britain and America.

Despite his intriguing profile and important legacy, Charles Burney has largely been neglected by book historians and literary scholars alike. The only notable exceptions are two biographical articles by Ralph Walker written half a century ago, and multiple brief references scattered throughout biographies and collected correspondence of other, more famous, members of the Burney family.Footnote 11 In the last few years, however, Charles has begun to attract attention in his own right as a figure with much to contribute to various fields. In particular, his habits as a reader and collector have begun to receive sharp sideways glances, with Katie Lanning describing him as a ‘compelling figure to study in terms of popular culture theory’Footnote 12 and Gillian Russell proposing that his ‘combin[ation of] the identities of book lover and ephemerile’ does not easily fit within the categories conventionally used to understand Romantic bibliomania.Footnote 13 An account of Charles’s unusual relationship with Evelina, which I have been gradually uncovering for the last ten years, offers a timely opportunity to bring his practices as a reader and bibliophile to the forefront of literary-historical scholarship in the long eighteenth century.

The text that enables me to do so is the debut novel of Charles’s elder sister, Frances Burney. Evelina is a polyphonic epistolary fiction which combines elements of the sentimental romance, the comic picaresque, and the novel of manners. The plot follows a naïve young girl’s quest to establish her rightful parentage while navigating the pitfalls of fashionable London life. Frequently hailed as one of the most innovative and influential fictions of the long eighteenth century, it has in recent decades become a staple of university syllabi, popular with students as well as researchers. However, recent studies have mainly focused on the novel’s gender politics, authorial persona, and paratexts,Footnote 14 and its reception among contemporary readers has not been sufficiently interrogated. Scholars often characterise Evelina’s reception as a chorus of universal acclaim, either drawing unquestioningly on Burney’s own life writingFootnote 15 or repeating certain well-known compliments from other literary figures which are used as evidence of unqualified admiration.Footnote 16 Other records of reader response, which have potential to complicate and enrich this picture, remain largely unplumbed.

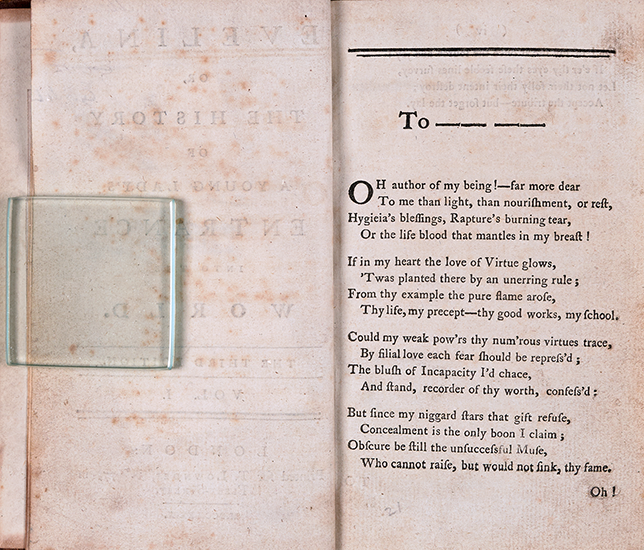

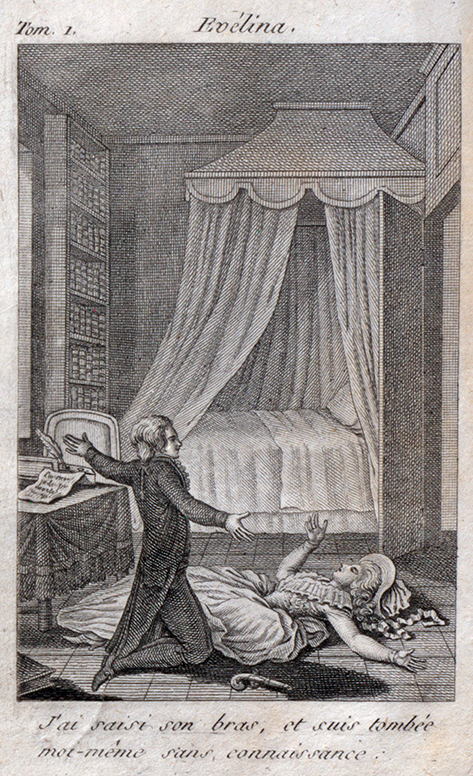

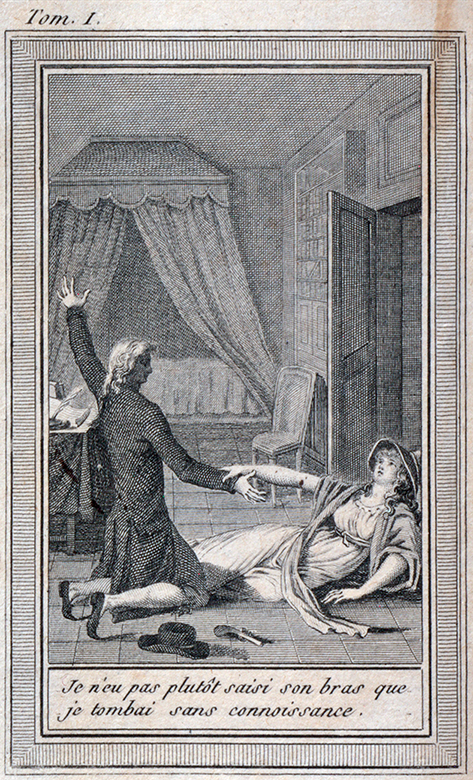

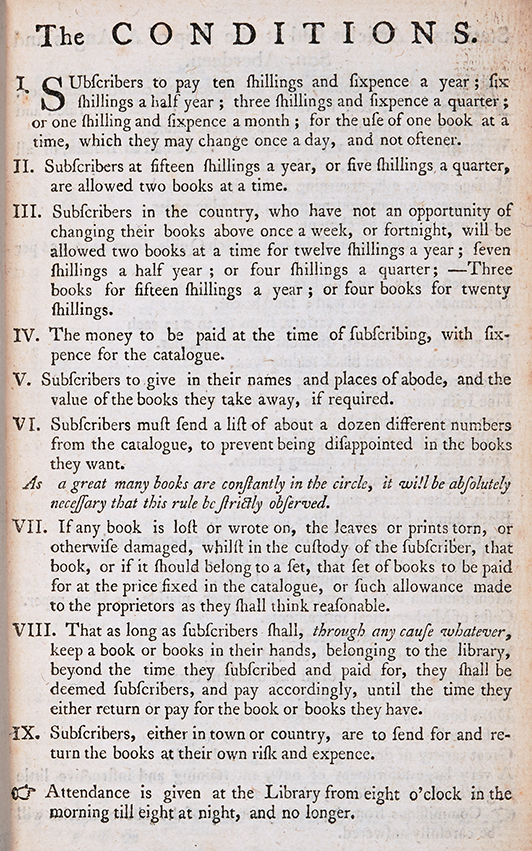

This Element aims to nuance our understanding of Evelina’s reception by describing Charles Burney’s relationship to Frances’s novel during the three years he spent in North East Scotland and positioning it within a broader range of reader responses within his Scottish circles and beyond. Charles’s numerous manuscript letters and poems from this period provide my starting point, since they provide an unusually full account of his treatment of Evelina, both in the extract already quoted and elsewhere. I also draw on the sonnet he ‘prefixed’ to his sister’s novel, which survives in two different versions, and on his other poems composed during this time. Furthermore, internal evidence from a 1779 third edition of Evelina held in the University of Aberdeen’s Special Collections – which I argue is actually one of the sets circulated by Charles – demonstrates how his tactile approach to the text fostered sociable relationships across genteel Scottish society. Finally, a unique copy of Conditions attached to the Catalogue of an Aberdeen circulating library provides vital information within which to contextualise Charles’s treatment of the set, while illustrative prints and frontispieces depicting a popular scene in Evelina offer a sense of the context within which he identified with the character of Mr Macartney.

The singular value of Charles Burney’s testimony is that, across all these sources, he stands in several distinct yet fluid relations to Evelina: prefixer, reader, and loaner. By synthesising such roles, we can mutually improve our understanding of Charles Burney’s reader profile, of Frances Burney’s authorial reception, and of the complexity of reading practices in late eighteenth-century Britain. The case of Evelina in Aberdeen helps us to rethink how books might be used as objects of circulation, inscription, and exchange; how they might disseminate knowledge and pleasure, generate affective attachment, and foster social networks. In offering these insights, this Element connects the fields of literary studies, biography, bibliography, and the history of the book.

Core Claims

The Element makes three claims about Frances and Charles Burney. First, I argue that, in an attempt to rebuild his own social standing in the wake of his Cambridge disgrace, Charles offered privileged access to his sister’s imaginative interiority and attempted to control how her novel was received within a reading community of his own creation. This claim extends Eve Tavor Bannet’s recent illustration of how ‘learned critics [might] give the character of an Author [through oral performance]’Footnote 17 to encompass textual self-creation. My approach also has significant implications for the topic of ‘family authorship,’ as addressed by Michelle Levy, Scott Krawczyk, and Hilary Havens, calling into question the terms under which such collaborations took place post-publication and positioning the Burney family as a crucial case study in this respect.Footnote 18

Second, I show that Charles’s project was facilitated by a tendency of Frances’s fiction to provoke a certain response, which I define as ‘identified performance’, in contemporaneous readers. Frances Burney’s novels have often been used to investigate how early readers conducted acts of ‘poaching’ (to use Michel de Certeau’s useful metaphor), especially in terms of staged and sociable readings aloud.Footnote 19 I argue, however, that her characters provoke identified performances which are not confined to closed reading sessions, but rather shape everyday textual and verbal behaviours, enabling the performer to blur the boundary between fiction and reality. While I showcase a range of case studies to demonstrate the fluidity of identified performance, my central focus is on Charles’s performance of Frances’s character Mr Macartney, and on his general eagerness to highlight the novel’s sentimental themes to press his own amatory and material advantage.

Third, I suggest that Charles’s reading practices were emphatically shaped by his status as a precarious agent within a loan economy. Despite the valuable cognate scholarship of David Allan, Mark Towsey, Jan Fergus, and Stephen Colclough,Footnote 20 little evidence currently exists about how readers considered the circulating library book as property, what rights they considered themselves to have over such an item, and the affective significance of the loan text as a mechanism for the circulation of knowledge, entertainment, and advantage. My reconstruction of Charles’s practice suggests a lack of clarity on the part of both proprietor and borrower about the circulating library book’s status during the loan period. Such libraries, therefore, could offer the impecunious borrower opportunities to use prestigious or in-demand books to strengthen affective ties within patronage networks and amatory relationships. However, ultimately the loan’s liminal proprietorial status could also hamper their ability to use the book to its full potential effect. Charles’s documented circulation of Evelina invites us to reconsider both the role of libraries in expanding the reading nation, and the ways in which they shaped readers’ affective relations with texts.

Structure of the Element

This Element consists of five sections and an Afterword. Section 1 provides information about Charles’s early life, which helps the reader to understand the nuances of his usage of Evelina. Drawing on his unpublished manuscript letters and poems, I highlight his interest in theatrical culture and the tension between his scholarly and creative ambitions. I also examine his adolescent relationship with Frances, emphasising an embryonic literary rivalry, which I locate within the well-documented desire among Burney siblings to please the family patriarch, Dr Charles Burney (1726–1814). Following his arrival in Aberdeen, I sketch the contours of Charles’s social circles and activities over the three years he spent in Scotland. I draw particular attention to Charles’s self-presentation as a young man of letters and his attempts to position himself as a suppliant for patronage, to women as well as men. Particularly important is his habit of circulating his own original manuscript poetry alongside (or within) printed texts selected to bear witness to his literary taste.

Section 2 reconstructs Charles’s documented encounters with his sister’s novel between 1777 and 1781. Noting his crucial role in helping Frances to preserve her anonymity with Lowndes in 1777, I build up a picture of his interactions with three separate sets of the published novel, which I call the Shinfield Evelina, the Aberdeen Evelina, and the Banff Evelina. Charles’s engagement with the text is marked by three key features. First, he is an energetic participant in prescribed and informal loan economies. He draws on both the resources of local circulating libraries and personal favours to obtain sets of Evelina, before sub-lending them to other parties. Second, he displays an interactive style of engagement with the text in ‘prefixing’ a poem of his own composition and using marginalia to reference personal jokes. Finally, he shows a tendency to inhabit, perform, and project characters from the diegesis created by Frances, and to encourage similar responses in fellow readers.

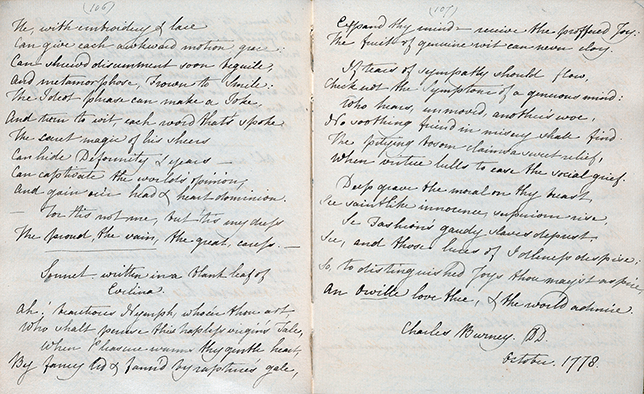

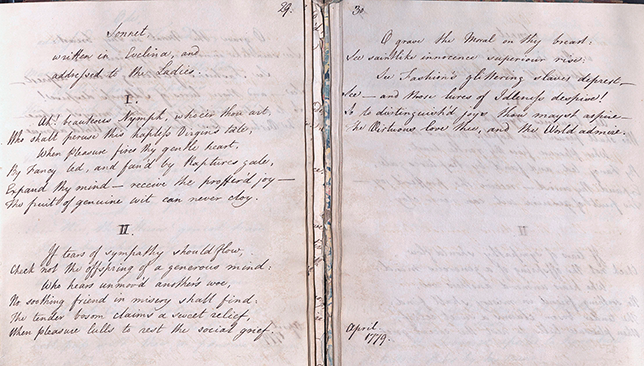

Section 3 analyses the sonnet addressed to ‘the Female Reader’, which Charles reports ‘prefix[ing]’ to the Aberdeen Evelina. I evaluate Charles’s sonnet as verse inscription, showing that it establishes a set of belletristic parameters within which ‘the female reader’ might respond to the novel and promotes the poet’s own literary gifts alongside the novelist’s.Footnote 21 I then consider it as a prefatory piece of paratext, which enables Charles to join his sister (the author) and his father (the dedicatee of the prefatory Ode) on the page.Footnote 22 This section, then, adds a further characteristic to Charles’s reader profile: the tendency to superimpose his desired identity as belletrist over Frances’s own as novelist.

Section 4 argues that Charles identified strongly with the character of the poor Scottish poet Mr Macartney, and that he ‘performed’ Macartney through his poetic and sociable practice. Here, I read Charles’s manuscript poetry alongside the verses attributed to Macartney within Evelina. Charles’s ‘Verse Letter to FJHW’, composed as he read Evelina for the first time, replicates the core tropes of Macartney’s ‘unfinished verses, beginning ‘O LIFE!’. Similarly, his odes to Nancy Gordon, Rachel Willox, and Jessy Willox, composed just as he was lending Evelina to these young women, bear marked similarities to Macartney’s verses dropped in the pump room. Charles’s correspondence suggests that he positioned himself as a gallant suppliant to the Willox sisters just as Macartney does to Evelina, and that he placed his relationship towards them along similar axes of brother/lover. Briefly, I also contextualise Charles’s identified performances by considering other contemporary reader responses to Frances Burney’s fiction from readers, including Queen Charlotte (1744–1818), Hannah More (1745–1833), Maria Edgeworth (1768–1849), and Jane Austen (1775–1817). Across this set of responses, I highlight consistent anxiety about the prospect of young female readers taking Frances Burney’s characters as models and developing unrealistic aspirations or undesirable behaviours as a result. Ironically, Charles’s identified performance of Macartney suggests that young men might have been more vulnerable to such a danger.

In the final section, Section 5, I consider Charles as a precarious agent within a loan economy centred around mass-produced print texts. I first examine him as a borrower, comparing his documented uses of the book to the prescriptive ‘Conditions’ of the library which may have lent it to him. I argue that the scale of Charles’s subletting practice should provoke us to reconsider how one loan may have spawned many readers, with significant implications for the scale of readership during this period and the impact of libraries on the reading nation.Footnote 23 Moreover, I compare his tactile engagement with the Aberdeen and Banff Evelinas to his mutilation of the stolen Cambridge books a few years earlier, asking what such acts of defacement might suggest about how different libraries exerted various forms of proprietorship over their holdings.Footnote 24 I then consider him as a lender of the text, who uses it to solicit patronage and express amatory aspiration. In a case study tracking the affective character of Charles’s sub-loans to the sisters Rachel and Jessy Willox, I evaluate his attempt to create a reading community in which demonstrations of his literary prowess alongside his sister’s would be repaid by amatory and material advantage. More broadly, I suggest that, within scholarship around gift exchange, material culture, and the history of emotions, the loan as concept and practice deserves greater attention. In Charles Burney’s cycle of lending and reclaiming his sister’s novel, one can access a sense of his insecurity in sociable, literary, and economic spheres, and see how he attempted to exploit opportunities offered by print and manuscript cultures to bolster his own footing.Footnote 25

The Afterword synthesises my findings, concludes the narrative of Charles’s time in Scotland, and provides a brief overview of the rest of his life. I highlight his ambivalent role in his famous sister’s literary career; he promoted and embellished her fictional and dramatic productions to the extent that, from the 1790s, she consistently referred to him as ‘her dear Agent’.Footnote 26 I draw attention to the many surviving sources which might shed light on his life and works, including his approximately 2,500 unpublished letters and poems, and his vast collections in the British Library. I frame him as a fascinating figure for whom textuality and sociability were paradigmatically linked, whose singular ‘Mad Rage for Possessing a Library’ (as Frances termed it) has the potential to help us rewrite the history of Romantic bibliomania.Footnote 27 Finally, I reflect on the methodologies used to piece together the story of Evelina in Scotland, highlighting the thriving interdisciplinary field of Burney Studies as a site where such methodologies can work together to great effect.

1 Introducing Charles Burney

Charles Burney was born in King’s Lynn, Norfolk, on 4 December 1757.Footnote 28 He was the fifth living child of Charles Burney (1726–1814), organist and music teacher, and Esther Burney (née Sleepe, 1725–62), proprietor of a fan shop in Cheapside.Footnote 29 When Charles was four, the Burneys moved from Norfolk to London, taking a house in Poland Street.Footnote 30 During Charles’s childhood and adolescence, this household was lively and cultured, despite the family being far from wealthy. During the 1760s and 1770s, the senior Charles Burney was networking furiously and travelling extensively – alongside a busy teaching schedule – in an attempt to consolidate his reputation as Britain’s foremost historian of music.Footnote 31 As a result, his children frequently received visits from celebrities of the day, most notably David Garrick, who would visit with his spaniel Phil and stage impromptu performances for the children.Footnote 32

Frances records that Charles was a great admirer of Garrick, who nicknamed his young fan ‘Cherry-Nose … on account of his nose being rather of the brightest,’ and that the little boy would ‘smirk and simper’ when favoured with his idol’s attention.Footnote 33 Charles’s own writings also testify that these visits made a considerable impression. When Garrick died, the twenty-two-year-old Charles penned passionate elegies mourning his genius.Footnote 34 And shortly before his own death at the age of sixty, as the proud owner of a ‘collection of Prints and Drawings of [Garrick] … not to be matched’, Charles would write: ‘scarcely a [day] passes in which the memory of Mr Garrick does not recur to my recollection’.Footnote 35

1.1 Charterhouse

Charles entered Charterhouse School on 15 February 1768 at the age of ten and departed on 10 April 1777 aged nineteen.Footnote 36 He boarded during term time but returned home to London during the holidays. In September 1768, Frances notes in her journal, ‘My sweet [baby] Charles is come home – he is well, hearty, & full of spirits, mirth & good-humour. My Aunt Nanny who went lately to see him at the Charter House, was assured there that he was the sweetest temper’d Boy in the school.’Footnote 37

It is around this time that Charles’s own archive begins. A handful of letters and poems survive from his time at Charterhouse – mostly addressed to Frances, to whom he was apparently close. Some of these describe Charles’s studies and academic progress, foreshadowing the scholarly application that would eventually make him one of the leading classicists of the early Romantic period. Aged eleven, he informs Frances that ‘all our Form are fagging at turner very hard’.Footnote 38Aged twelve, he copies out a Greek alphabet for her – ‘I am sure you will be Charmed with it … there is a great number of odd letter’s but you are so well aquainted with the Language that I need not tell you that’ [sic] – and spells her name in Greek characters, apologising for the lack of a letter corresponding to ‘F’.Footnote 39 But elsewhere he hints that such application might not come entirely naturally. He does ‘fag hard in search of further knowledge’ but there is a good reason for such diligent application: ‘Berdmore is really very strict, / And will sharp punishment inflict, / Of idleness – & therefore I / Wholly to Greek my mind apply.’Footnote 40

In fact, the teenage Charles evidently had a range of interests, the most apparent of which is his poetic inclination. He often composes light verse to entertain – or tease – friends and family. In a poem dated 3 May 1774, Frances is accused of ‘flirting about town’, while a braggart school friend is advised:

Frances Burney could evidently give as good as she got, since one of Charles’s letters indicates that his nose had recently been a subject of ribaldry: ‘Indeed Madam I don’t like your severe Sarcasm upon my Poor Nose [… which] to be sure has little of the Redish Cast.’Footnote 42 Despite such badinage, he clearly missed his family immensely when at school. He eagerly enquires after various members, declares that he ‘long[s] to … come home’, and on one occasion remarks plaintively, ‘I thought you had almost forgot Carlo Dolci.’Footnote 43 When he did return for the holidays he deployed his poetic knack for the amusement of his siblings, as in an ‘Occasional Prologue’ to Goldsmith’s The Good Natur’d Man, intended to be delivered following a domestic performance by the Burney children.Footnote 44 His passion for theatre is evident in several of these items – for example, a long verse-letter in which he enviously imagines Frances visiting theatres and concerts in London and enjoying performances by Garrick and Jane Barsanti.Footnote 45

1.2 Cambridge

Charles departed Charterhouse on 10 April 1777, bound for Caius College at the University of Cambridge.Footnote 46 He had been studying there for only a few months when his theft was discovered in late October, and he was promptly expelled.Footnote 47 The principal contemporary account of the crime, written by the antiquary William Cole, describes Charles as a ‘very studious & industrious’ student. ‘Insomuch, that he was admitted into the Public [University] Library, tho’ an Undergraduate’ and ‘regularly came every Day & stayed till the Doors were closed’. A certain ‘Marshall the Schole Keeper’ began to observe that ‘a great Number [of books] had been taken away, chiefly classical Books of Elzevir Editions’.

[H]e began to suspect Mr Berney, & complained to Mr. Whisson, the Under Librarian, who advised him to be quiet, & contrive to get into his Chambers, & see if he could discover any of the lost Books: the Bedmaker said, it would be difficult, as her Master was very studious, & hardly ever 20 Minutes out of his Room at a time except at Dinner Time: he got in at that Time & found about 35 Classical Books in a dark Corner, which he had taken the University Arms out of, & put his own in their place; & the Tutor being spoken to, he went into Hall the Day it was first discovered to him & then disappeared: & this Week a Box of Books belonging to the Library was sent from London, whither he had sent them. What further will be done is unknown. I pity his Father, who must sensibly feel the Stroke; as the young Man can never appear again in the University & so his views in this way utterly overturned.Footnote 48

Dr Burney did indeed ‘sensibly feel the Stroke’. As Walker notes, he was incensed at his son’s crime and considered disowning him. For the present, there was no possibility of Charles returning to the family home. He was sent to the village of Shinfield in Berkshire, where he would remain until gossip died down and a decision could be made about his future.

1.3 Shinfield

Although Charles lived in Shinfield for almost a year, Walker provides little information about his life there, blaming the paltry archive. He remarks only that Charles ‘felt decidedly superior to the rustic circle in which he found himself’, citing his poetical satire on ‘such features of Shinfield life as the preaching of the little Welsh curate, the jangling of the Church bell, and the inharmonious singing of the village choir’.Footnote 49 This summary does not do full justice to Charles’s carefully curated archive of verse dating from 1778. Numerous affectionate poems dedicated to members of Shinfield society survive, which cumulatively show him flexing his sociable and literary muscles during this period, using verse to cement and commemorate key relationships.Footnote 50

This verse also provides valuable biographical information. For example, it has long been a mystery to Burney scholars why Shinfield was chosen as the place for Charles’s exile, or who cared for him while he lived there.Footnote 51 The poetry suggests a probable answer. Upon his departure from Shinfield in 1778, Charles writes parting verses for four members of the Francis family: ‘Mr Francis’, ‘Master William Francis’, ‘Miss Polly Francis’, and ‘Master James Francis’.Footnote 52 It seems that the Master of Shinfield School around 1780 was one William Francis, a mathematician who appears as a correspondent in the pages of several literary and scientific periodicals.Footnote 53 The Pedigree Register confirms his occupation and location in 1778, and the name of his eldest son.Footnote 54 Given Francis’s pedagogical qualifications, Charles’s familiar relationship with his children, and a reference to Mrs Francis in one of his letters (see Section 2), I think it probable that following his Cambridge disgrace Charles was entrusted to the care of the Francis family.Footnote 55 In any event, by the time he left Shinfield, he was reminiscing over happy days spent there swimming in the river and playing card games, sentimentally characterising the village as the home of ‘peace’, ‘endless loves’, and ‘social mirth’.Footnote 56

During the Shinfield period, Charles’s poems and letters also record intensive engagement with news and periodical print culture, both local and metropolitan. Possibly imitating or encouraged by William Francis, he pens poetic answers to enigmas in the Gentleman’s Diary and Ladies’ Diary.Footnote 57 He participates in a topical debate raging within the pages of the Reading Mercury (to which Francis also contributed poetry), versifying in defence of a surgeon called Cundall who promoted the controversial practice of inoculation.Footnote 58 He also composes verses on recent London scandals, indicating that he had access to such gossip either via correspondence or the newspapers.Footnote 59 Some of these poems, like those written at Charterhouse, are doggerel or light verse clearly designed to amuse. But Charles also begins to attempt, during the year 1779, a neoclassical poetic diction. His poetry starts to address topics such as friendship, virtue, and the callousness of fate, using a register characterised by archaism, epithet, abstraction, and periphrasis. These shifts in form and tone may demonstrate the growing influence of Charles’s classical knowledge on his poetic development, or a more serious outlook on life following the consequences of his theft. In Section 4, I argue that they are also influenced by the signature style(s) of Frances Burney’s poet Macartney in Evelina.

During the Shinfield period, Frances Burney is Charles’s only known correspondent. In a journal entry for 30 March 1778, she remarks, ‘I have just received a Letter from poor Charles, in which he informs me that he has subscribed to a Circulating Library at Reading – & then he adds, “I am to have Evelina to Day; the man told me that it was spoken very highly of.”’Footnote 60 Unfortunately, none of Frances’s own correspondence to Charles from the period survives. However, two fragmentary letters from him to her, of which Walker was apparently unaware, do.Footnote 61 Although undated, they must have been written after Frances’s mention of the Reading circulating library at the end of March 1778, but before Charles left Shinfield in October. These two fragments are notable first because they contain Charles’s first recorded response to Evelina (see Section 2), and second because one of them suggests that during his time in Shinfield Charles was helping Frances to improve her Latin. He corrects her translation of a passage of Seneca, which she had apparently sent him in a previous letter.Footnote 62 It is tempting to read this letter, alongside Charles’s 1769 reference to Frances’s interest in Greek, as two points in a long-standing adolescent exchange about classical languages and literatures.

The implications of this possibility are twofold. The first concerns Frances Burney’s access to stereotypically masculine forms of knowledge. It is well-known that she briefly studied Latin in her late twenties – an accomplishment often deemed risky for a woman, since it might indicate a desire to transgress gendered spheres of learning and aspire to ‘bluestocking’ fame. However, this has usually been presented as an honour thrust upon her by Dr Johnson, which was only pursued for a short period before her father persuaded her to return to more traditionally feminine literary activities. Burney herself has been understood – based on her own letters to her sister Susan – as a reluctant scholar who feared the implications of being known to study the classics and lamented ‘devot[ing] so much Time to acquire something I shall always dread to have known’.Footnote 63 But these previously unremarked letters between Charles and Frances suggest that she was willingly studying Latin a full year before Johnson offered to teach her, indicating that she was more eager than she would admit to acquire classical learning. The second implication concerns the routes by which Frances Burney accessed specialist knowledge and intellectual fulfilment during the early years of her literary career. The Streatham environment dominated by Johnson is often pinpointed as crucial in this respect. But it may be that in focusing so heavily on his influence, and that of Hester Thrale, we have neglected to see what was available to Frances within her family unit. Despite his disgrace and exile, her ‘sweet [baby] Charles’ – who of course had benefited from the first-class education she could never have had – was supporting her intellectual development just as actively as, and long before, Johnson.

However, it is important not to overstate Charles’s generosity in assuming a pedagogical relationship towards his celebrated sister, since it probably conveyed a form of gratification that was far from selfless. In the 1778 letter discussing Evelina and Seneca, it is striking how little space Charles devotes to celebrating Frances’s recent literary achievement (two lines) in comparison to correcting her faulty Latin (more than forty). In doing so, his tone is in places rather patronising, offering backhanded compliments such as ‘your emendations in general please me’ and scolding her for contracting verbs: ‘It cannot be confin’d: for fin does not spell fine – & so in the other Verbs of this sort.’ Overall, the tone and content of the letter subordinates Frances’s creative achievement to Charles’s own critical expertise. This was not the last time he would attempt to assert himself in such a manner.

By autumn of 1778, the next step in Charles’s career was determined: Dr Burney and his friends decided that the black sheep of the family should finish his education at King’s College, Aberdeen.Footnote 64 ‘Let me shake off the rustic’, Charles declares in his final Shinfield poem, ‘& once more / The gayer joys of College life explore’.Footnote 65 He made the long journey northward between October and the end of that year, and was settled in Aberdeen by the beginning of 1779.Footnote 66

1.4 Aberdeen and Banff

Charles’s archive contains no material describing the journey from Shinfield to Aberdeen. Neither does it address his arrival in the city or his living quarters. However, plenty of information exists in the published memoirs of two of his contemporaries: the playwright George Colman (1762–1836), who attended King’s College between 1781 and 1783, and the abolitionist James Stephen (1758–1832), who attended Marischal College between 1775 and 1778.Footnote 67 Both, like Charles, had previously been Londoners, and they offer scathing accounts of their new home: a town resembling ‘a long dreary village’ which was ‘very unsightly and mean to an eye accustomed to London’.Footnote 68 Colman, who lived in the same building as Burney, is contemptuous about his ‘small sitting-room’ and second-hand furniture, but mollified by the fact that at least his quarters are the envy of his Scottish peers at King’s, ‘young barbarians, migrating from their mountains, to be half-civilised’.Footnote 69 He is also dismissive of the College’s attempt to impose academic rigour, noting that during the short five-month term there was ‘no discipline at all’. Although he did not apparently dislike his tutors, he makes it clear that they did not exercise any authority over the students,Footnote 70 and recalls learning by solitary study, borrowing books from the college library and poring over them in his rooms. He reports hearing from mutual friends that Charles Burney, during his time at King’s, had done likewise, shut away in his chambers ‘unaided by Scottish professors [and] secluding himself like a hermit’.Footnote 71

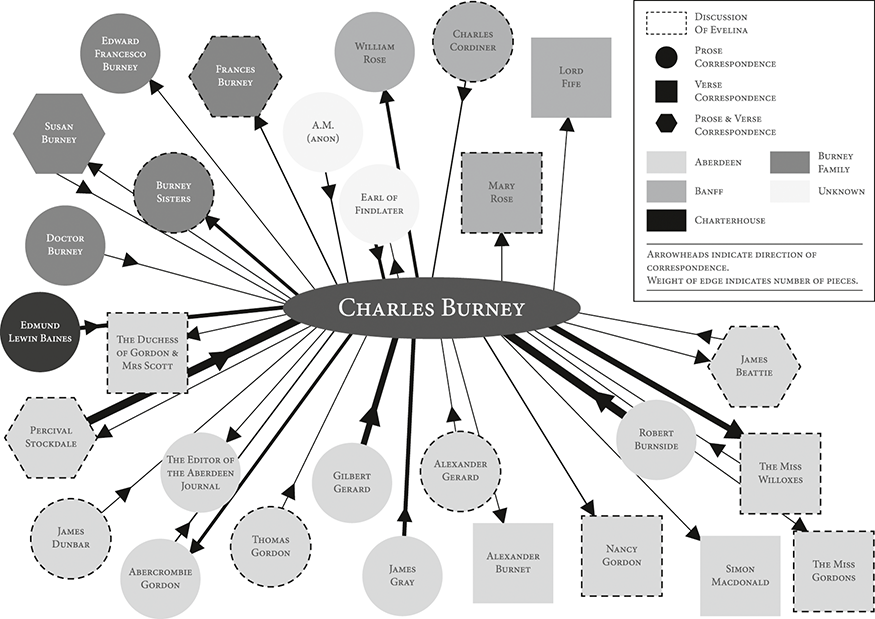

However, as Colman’s editor Richard Brinsley Peake notes, this characterisation of Charles as a studious ‘hermit’ should be taken with a pinch of salt.Footnote 72 In fact, if we turn to his extant letters and verses, which recommence from February 1779, it is clear that he enjoyed a lively social life in Aberdeen. Though he writes to Frances, in a vein of snobbery similar to Colman’s, that ‘in aspect, appearance, & dress, [his fellow students] look marvelously like plough boys’ [sic], he takes care to note ‘a few exceptions’ where ‘a natural good breeding, acquired by narrow observation, guided by a solid understanding, has been able to shake off highland rust’.Footnote 73 As I show in Figure 1, such Aberdeen friends as James Gray (1761–94), Robert Burnside (1759–1826), Abercrombie Gordon (1758–1821), and Gilbert Gerard (1760–1815) provide some of the most extensive, vivid, and informative letters in Charles’s Scottish archive.Footnote 74

Figure 1 Visualisation of Charles Burney’s correspondence network from January 1779 to August 1781.

Recalling Colman’s observation that King’s tutors did not stand on ceremony with their students, it seems that Charles was also friendly with his tutors: James Dunbar (1742–98, Professor of Moral Philosophy), Thomas Gordon (1714–97, Professor of Philosophy), and Alexander Gerard (1728–95, Professor of Divinity). In summary, Charles was taking his place in a small community, where academic, social, and domestic spheres frequently overlapped. Charles befriended the sons of his tutors and flirted with their daughters. He was invited to their town houses during the term and stayed at their estates during the vacation. Through them he also met other members of Aberdeen gentry such as the Burnet and Willox families.

Rachel and Jessy Willox, whom I address in Section 5, merit a special mention. As well as in Charles’s own letters and poetry, we can find biographical information about them in the family memoir of the Dingwall Fordyce family (into which Rachel eventually married) and James Stephen’s Memoirs.Footnote 75 Stephen, who knew the sisters personally, describes the Miss Willoxes as ‘the most celebrated beauties of the place … in whose education [their father, the Baillie of Aberdeen George Willox] had spared no cost, so that they were as much distinguished by their accomplishments as by their beauty’. He also notes their mother’s eagerness to ‘assist them in finding advantageous settlements in marriage … Every young man of fortune or good expectations in life found easy access to them under the parental roof’. Stephen characterises Rachel as ‘the finest and most graceful figure I ever saw’, with ‘the best complexion’, ‘a profusion of flaxen hair’, ‘large blue eyes [with] great expression and power’, and features expressing ‘dignity’. He describes Jessy as ‘also very handsome… [some] thought her more so than her Sister, tho’ much inferior to her in understanding’.Footnote 76 Stephen’s descriptions accord closely with Charles’s own account of the sisters, which we find in a letter to Frances, highlighting the ‘agreeable … liveliness’ of ‘the lovely’ Jessy’s temper, while praising the ‘milder graces’ and ‘conscious dignity’ of Rachel’s. Interestingly, he uses Samuel Richardson’s novel Sir Charles Grandison (1754) to gloss them further: ‘Jessy is a Charlotte G, and Rachel, what Lady L, might have been before marriage – You remember Sir Cha. Grandison. Love would be the food of Rachel’s life, & the seasoning of Jessy’s!’Footnote 77 Charlotte Grandison, of course, is presented in Richardson’s novel as ‘frank, easy and good-humoured’ with ‘a vein of raillery, that were she not polite, would give one too much apprehension for one’s ease’, whereas Lady L has ‘true female softness and delicacy’, with ‘so much sweetness and complacency, that you are not so much afraid of her as you are of her sister’.Footnote 78

Throughout the early spring of 1779, Charles doles out his poetic compliments equally to several young ladies, but by May he had clearly become infatuated with ‘my adorable Jessy’. In the letter to Frances containing his account of Evelina’s reception, he praises Jessy’s ‘liveliness, sweetness & goodness’, making much of his ‘affection’ for her even though he considered his ‘unsettled state’ a prohibition to ‘speaking out’.Footnote 79 He also writes a poem praising her ‘beauties’ and swearing that time will only ‘improve’ his passion.Footnote 80 It is not clear whether his affection was returned. During 1779, his friends seem to have considered him ‘a settled man’, but he also laments Jessy’s occasional ‘coldness’ and expresses anxiety that she does not ‘burn with the same flame’ as he does.Footnote 81 Charles was also clearly friendly with Rachel, since he writes her a long poem to celebrate her ‘recovery from a dangerous illness’, and four of his poems address the two young women collectively. His intense interest in the sisters is evident until the late summer of 1780, when Jessy abruptly (and, for Charles, unexpectedly) married another suitor.Footnote 82

Charles was not in Aberdeen when Jessy’s engagement took place, because – like many of his peers – he spent his long vacations travelling the north-east of Scotland. The trip he took in the summer of 1780 – upon which he took a set of Evelina with him – is particularly well-evidenced, since he kept a detailed travel journal, intended for his sisters.Footnote 83 He spent significant time in Banffshire, for part of which he was the guest of James Duff, 2nd Earl of Fife (1729–1809), and became acquainted with Fife’s factor William Rose (1740–1807), Rose’s wife Mary (1757–1838), and the Banff minister Charles Cordiner (1746–94). As mentioned in Section 3, he developed a passionate crush on Mary Rose and left Evelina in her custody when he returned from Banff to Aberdeen in the autumn of 1780.

During Charles’s final year of study, his archive becomes sparser. A rare letter remarks, ‘the College is very full this year but it might as well be empty for me – as there is not one whom I ever speak to, or see in my rooms’. However, he was not bereft of entertainment: ‘the Players are in town’ and ‘I go every night; except when I am otherwise particularly engaged’.Footnote 84 It is likely – though Charles does not mention it – that he was gambling heavily during this time, given the parlous state of his finances which emerged later in the year. His impending graduation, and the question mark remaining over his future, seem to have been weighing on his mind, since he asks several friends whether they can help him obtain a curacy, without any success.Footnote 85

Between September 1780 and January 1781, Charles became acquainted with James Ogilvy, Earl of Seafield and Findlater (1750–1811), an important figure in queer history. Though married, Findlater was well known to prefer men to women; he lived the last two decades of his life, and eventually shared a grave, with his partner Johann Fischer.Footnote 86 The nature of the relationship between Findlater and Charles during the early 1780s is unclear, but surviving correspondence between them suggests a certain intimacy. In January 1781, in a letter which he warns Charles is ‘not meant for publication’, Findlater praises Charles’s ‘Attractions’ and describes the ‘Friendship’ between them as ‘founded by Reason & … fostered by Passion … When will you leave your Doctors & Diplomas to come to me?’ He also jokes about his wife’s dislike of Charles: she ‘hates whoever I am attached to, with a Uniformity that does Honour to her Perseverance, if not her Heart’.Footnote 87 The correspondence indicates that Findlater offered Charles significant financial support during his final months in Aberdeen. In April 1781, he agrees to send Charles thirty guineas, which he hopes will ‘be sufficient for the Expense of the Menus Plaisirs of last Winter’.Footnote 88

Findlater also seems to have offered to take Charles on an imminent trip to London, and en route to introduce him to the Archbishop of York with a view to easing his path to ordination. Charles apparently reported this prospect to his father with some excitement, but Dr Burney’s response sounds a note of caution and suggests that he was pretty alert to the nature of Findlater’s attachment to his son:

None are treated in such a Manner as you have been, by several great Personages in Scotland, but for something wch they are pleased to admit as an equivalent – Pure Friendship is imagined to be the most disinterested of all affections; but I fear when accurately examined it will turn out to be as selfish as many other Passions of a grosser Name … as to Ld Fin–ter’s affection for you it seems like that of David for Jonathan, so ‘wonderful as to suggest the Love of Woman’ … You have never yet mentioned Ly F--------ter – is my Ld a Married Man? Has he Children?Footnote 89

In the end, the trip never took place since Findlater withdrew his offer, citing his wife’s objections to Charles as a travelling companion.Footnote 90 In April, the Findlaters set out for York and London, while Charles graduated in Aberdeen.Footnote 91

Immediately after graduation, Charles was supposed to return to his family, but instead he lingered in Scotland for almost three months. In letters to his sisters written over the early summer, he declares that he cannot tear himself away from a new love interest called Jane Abernethie, a cousin of Lord Fife’s: ‘The Abernethie has so engrossed my affections, of late, that I lived, breathed, saw, heard, for her alone.’Footnote 92 This rather abrupt attachment is not evidenced by any amatory poetry like that produced for Jessy Willox or Mary Rose. Neither does Jane Abernethie appear to have been keen on Charles, since, by his own admission, she had forbidden him from writing to her. Nonetheless, when the Abernethie family moved from Aberdeen to Banff for the summer, Charles apparently followed them. Betty Rizzo suggests, very credibly, that the attachment was pragmatic rather than heartfelt, and that Charles hoped to persuade the well-born Abernethie to elope with him so he could secure a settlement to pay off his debts.Footnote 93 But such a plan, if it existed, appears to have come to nothing. The object of his intentions eventually took refuge with a remote aunt, and Charles finally began his overdue journey back to London. He arrived at St Martin’s Street in the last week of July 1781. Bizarrely, he had brought with him a dog called Chloe, which he claimed that Jane Abernethie had given him, and which promptly gave birth to puppies.Footnote 94

1.5 A Common Theme: Prospects, Poetry, and Patronage

Despite his Cambridge disgrace, and its implication that Charles took a somewhat cavalier approach to the Commandments, Dr Burney had nonetheless afterwards decided that he should complete his expensive education and pursue a career in the Anglican Church. As William Jacob notes, the office of clergyman was one of the three main professions pursued by intellectually gifted young men of the ‘middling sort’: it had a well-established practical framework for career advancement which could, if combined with a talent for generating patronage, take one to significant career heights.Footnote 95 Impeccably respectable, and with significant opportunities for academic honours and learned publication, it segued nicely with Dr Burney’s aspirations for his most academically precocious child. Practically speaking, ordination candidates were expected to be fluent in Latin and Greek as well as to have sound theological understanding. Although there is evidence of regional variation, it is safe to say that most were university graduates.Footnote 96

The primary purpose of the theology degree Charles was undertaking at Aberdeen was, therefore, to complete the education that had been cut short at Cambridge. The second, but hardly less important, objective was to establish and maintain an excellent character in the eyes of his tutors and other influential people. Dr Burney was explicit on this point when he wrote to his son in February 1781. Charles’s priorities should be to ‘pursue your Studies with diligence’ and to ‘quit the place with credit & propriety’. These two objectives would feed towards the next steps of obtaining a curacy (a training post, also sometimes called a ‘title’), securing strong character references, and preparing for the ‘important business’ of ordination.Footnote 97

Charles himself, however, was ambivalent about the path his father had prescribed for him. Correspondence from his friend Robert Burnside, already ordained, indicates that Charles had expressed ‘tremors’ about ordination, occasioning some gentle reproval: “If you remember, I asked you the last time I enjoyed the pleasure of your conversation what was your opinion concerning … the ends which a man of sense, of honesty, & worth ought to have in view in entering upon the ministerial function, &c. You replied you had not thought about these matters. Excuse me, if I think that the present time seems to me to be a very proper one for you to investigate these points”.Footnote 98 Percival Stockdale, also ordained, writes a little more stiffly: ‘I hope you will now employ yourself strenuously on this study, and look on your Profession as the noblest of all human professions, not-withstanding the superficial Ridicule; XXX and the despicable contempt of your most despicable contemporaries.’Footnote 99

With such ambivalence about Charles’s own prospects in mind, I want to consider the relationship between form and purpose in his poetic output during his Scottish years. I noted in my discussion of the Charterhouse and Shinfield poetry that Charles often dedicates his verses to individuals, either to mark a particular occasion or to praise the dedicatee. His Scottish poetry continues this tendency, but combines it with a tendency to lament the poet’s hard lot in life and promote his own literary gifts. His ‘Ode Addressed to Alexander Burnet of Seaton House’, for example, implores the fourth Laird of Kemnay and recently retired diplomat (1735–1802) to ‘extend [his] fond esteem’ to ‘cheer the Bard’, who contemplates an uncertain future. At risk of having his ‘Bark … tost’ by ‘storms’, Charles is positioned as a humble suppliant for Burnet’s favour, with only poetic gifts to offer in return. If they were only equal to the excellence of their subject, he grovels, they might ‘with a fire immortal glow’, and ‘flourish … with deathless garlands drest’. Similarly, in Charles’s fragmentary ode addressed to Fife, he positions himself as the ‘Bard’ and ‘laurel’d Poet’ offering his patron a ‘deathless song’.Footnote 100 His poetic address to James Beattie (1735–1803) unfolds along similar lines, declaring a desire to ‘court thy smile’ by ‘sing[ing Beattie’s] praise’.Footnote 101

The recurrent suppliant poetic positioning suggests that these verses can be read as emphatic, if indistinct, solicitations for patronage. Scholars of eighteenth-century patronage have long recognised the crucial role performed by poetry in soliciting and securing support from patrons. Moreover, in recent decades, they have broadened their understanding of the forms that literary patronage might take beyond the relatively narrow confines of hard cash or lucrative posts.Footnote 102 A more expansive set of categories – hospitality, material gifts, approbation, endorsements, advice, and introductions (to spaces or individuals) – is now recognised as crucial to the ways in which authors burnished their reputations and built earning power.Footnote 103 Charles might have been soliciting any of these forms of patronage when he set out using his poetry to ‘widen the circle of his acquaintance’.Footnote 104 We have seen one example, in his correspondence with Findlater, of the tangible benefits that he hoped to obtain from friendships with eminent men. Such endeavours stood upon the foundation of flattery and self-promotion evidenced by his verse.

Crucially, however, the dedicatees are oddly placed to help Charles further the aims that Dr Burney had instructed him to pursue. Of the twelve people for whom epistolary poetry survives, five are marriageable young ladies and two are older women (see Figure 1). Of the remaining five, Fife is a politician (who only had Episcopalian livings in his gift, and whom Dr Burney did not consider likely to offer meaningful patronage);Footnote 105 Alexander Burnet is a former diplomat, James Beattie is a poet and an essayist, and Simon Macdonald is an ensign in the navy.Footnote 106 The only clergyman to whom Charles dedicates poetry, Percival Stockdale, was notoriously bad at the job, and poorly placed to help Charles develop a career in the Church.Footnote 107 There is no evidence that Charles dedicated poetry to any of his tutors, or to senior clergy who might be able to help him find a title. The poems are just as poorly targeted in terms of composition as circulation, since they are overwhelmingly occasional, secular, and vernacular. The odd Latin epigraph aside, they make little attempt to showcase Charles’s classical or theological learning.

Charles’s verses dedicated to women require separate consideration, since they reproduce the suppliant positioning of those addressed to Beattie, Fife, and Burnet, but with a gendered twist. He begs the Willox sisters, for example, to treat him as a pet, who might ‘[a]ttend your toilets – set your caps – / Or rest, thrice happy, in your laps. / Make me your monkey, squirrel, cat – Your dog or bird – no matter what; Only your favourite let me be’.Footnote 108 They also centre the poet’s literary gifts, but with the addition of a striking material dimension. When writing to women, Charles often sends his verses as an accompaniment to a gift – usually a book or poem, though he also occasionally sends edibles – which is referenced in the poem’s title. In the verses, he reflects on the transformative effect that consuming the gift might have on the recipient’s moral and emotional development, and offers guidance as to the form it should take. Such a stance significantly complicates the dynamic of solicitation.

Take, for example, the ‘Ode, sent to the Miss Gordons, with The Goodnatur’d Man, A Comedy, by Dr Goldsmith’. Charles uses these verses to raise the topic of critical taste:

While this poem is ostensibly deferential to the young ladies’ critical opinions, Charles also uses it to draw attention to his own literary gifts. His mention of himself, the ‘Poet’, is linked metrically with Goldsmith’s ‘Bard’, thereby establishing a connection with the famous playwright which is also reflected in the double gift of the published play and the manuscript poem. The verses also imply that both ‘Bard’ and ‘Poet’ have had experience of ‘Critics impotent and vain’ – the poet’s frustration is exercised not only on Goldsmith’s behalf but also, it seems, on his own.

Then there is ‘Sonnet Addressed to Miss Rachel and Miss Jessy Willox, Prefaced to the Epistles from Euphrasia to Castalio; and from Edwin to Angelina’.Footnote 110 In this poem, Charles declares his certainty that if they peruse his own poetic portrayals of ‘A Lovers’ sorrows, and a Lady’s sighs’, Rachel and Jessy’s ‘gentle hearts’ cannot remain ‘unmoved’. ‘Then fear not’, he instructs them, ‘if a rising sigh displays / Your worth of mind, and tenderness of heart’. The reader then experiences an abrupt transition to the poet’s contemplation of his own prospective literary fame:

Again, in ‘Ode sent with the Memoirs of Miss Sidney Biddulph to the Miss Willoxes’, there is similar certainty that Frances Sheridan’s narrative cannot fail to ‘impart’ the protagonist’s sufferings to ‘the generous heart’. But even as this poem is initially framed as addressing Rachel and Jessy’s responses to the text, it is really Charles’s own literary sensibility that he wants to display. ‘For heavenly transports bless his mind, Who lives – the friend of human kind: Whose soul Compassion’s law has taught, And with the noblest feelings fraught’Footnote 111 [italics mine].

In a sensitive study of Elizabeth Montagu’s reading networks, Markman Ellis contends that disseminating books as gifts is ‘an important signal in the economy of patronage and sycophancy’.Footnote 112 These brief examples demonstrate how Charles sent decidedly mixed signals, uneasily blending the position of bardic sycophancy with a tone of authoritative critical instruction. Having established Charles’s general circulatory practice in this respect, in the next section I turn to the specific printed text that he embellished with manuscript poetry most frequently – and strikingly – to burnish his social standing. This, of course, is Evelina. Such practice emerged from a specific set of circumstances in which alienation, insecurity, and ambition all met in Charles Burney’s poetic output. To understand why this was, we need to turn to his sister’s novel.

2 Charles and Evelina

Evelina was published in January 1778, and Frances Burney’s identity as the author was revealed in June. Her subsequent celebrity has been extensively documented.Footnote 113 It is worth noting that the teenage Charles could claim a minuscule share of the credit for bringing Evelina to publication, since in 1776–77, he had helped Frances to preserve her anonymity with Lowndes by acting as a disguised go-between under the assumed name of ‘Mr King’.Footnote 114 While many scholars have noted this fact, they have not contextualised Charles’s early performance as part of a broader picture of ambivalent promotional practice. Charles would continue, following Evelina’s publication, to facilitate its circulation and bolster its reputation. Simultaneously, he would attempt to superimpose his own performed identity over that of his author-sister.

This section of the Element reconstructs Charles’s engagements with three different sets of Evelina between 1777 and 1781. For convenience, I call these texts the Shinfield Evelina, the Aberdeen Evelina, and the Banff Evelina, and structure my narrative accordingly. I then turn to examine a 1779 third edition of the novel held in Special Collections at the University of Aberdeen (hereafter called the SC set), arguing that idiosyncratic marginalia identify it as the very copy that Charles lent around Banff. This provides necessary context for Sections 3–6, in which Charles is more closely considered as prefixer, reader, and loaner.

2.1 The Shinfield Evelina

Charles read Evelina for the first time during the spring of 1778.Footnote 115 His correspondence with Frances indicates that he tried to borrow a set from a circulating library in Reading, but ultimately ended up reading one that she sent to him from London.Footnote 116 As briefly noted in Section 1, two different fragments from Charles to Frances dating from this period survive, both of which mention his early response to Evelina. In the first, he notes at the head of the page, ‘I have read Evelina, & like it vastely [sic] much’, before proceeding to correct her translation of Seneca. At the foot, he adds a postscript: ‘This [the letter] shall accompany Evelina, which the Parson is reading.’Footnote 117 The second fragment is more detailed:

I think the Letter which describes the Meeting of Evelina, & Sir John Belmont is the best written in the Book; & the horror & remorse, which must almost necessarily attend such a meeting, is very admirably described. Mrs Francis cried when she read it – She admires it much I can promise you – & launched out in the praise of the unknown Writer. I, as you know, am not at all smoaky – So it went off very well: She cd not eat any dinner, while she was engaged in reading it – In the Ode, I believe that glows would after, of, have been more elegant, had it been glow, but the Verse, or rather Rhime, wd not allow it.

I like Evelina excessively: I am not fond of Novels in general; &, those of Richardson, Fielding, & Smollett being excepted, there is scarcely one I wd ever wish to read again – to those Authors’ works, I must now add Miss B–’s productions – Pray whose set is this, which you have sent me? It is not the one you mentioned: pray answer me this question – I hope you will not be offended at my criticisms, I did not look for faults …Footnote 118

In Section 1, I noted that the form of the Seneca letter works to subordinate Frances’s creative achievement to Charles’s critical expertise. This second fragment, I think, effectively does the same thing. While his overall tone is complimentary, Charles also offers ‘criticisms’ of the ‘faults’ he detects, particularly in the prefatory Ode. His airy aside that he is ‘not fond of novels in general’ also serves as a backhanded compliment, reminding Frances of the lowbrow form she has chosen even as he condescends to place her with its acknowledged masters.

It is easy to imagine that Charles may have had mixed feelings about his sister’s literary success, and that he might have found it galling to compare their situations. Drawing on Hester Thrale’s sharp observation about the Burney siblings – ‘their Esteem & fondness for the Dr. seems to inspire them all with a Desire not to disgrace him; & so every individual of [the family] must write and read & be literary’ – Margaret Doody has argued convincingly that throughout their lives the Burney children remained desperate to please their father through literary achievements and honours.Footnote 119 Other biographers have speculated that Dr Burney’s enthusiasm for promoting Frances’s celebrity at this time stemmed partly from embarrassment at the spectacular fall from grace of his budding scholar.Footnote 120 Charles’s own career prospects looked extremely uncertain during 1778, when, as he wrote to his school friend Francis Wollaston, he was ‘Forced to relinquish every fondest hope / My time in vile obscurity to waste’.Footnote 121 The brevity of his recognition of Frances’s achievement, and the high-handed tone he takes to ‘correct’ her prose, might therefore credibly be attributed to envy, stemming from a feeling of comparative inferiority. If so, it indicates an early propensity in Charles to see his sister’s literary success as related, or at least relatable, to his own intellectual prowess, and to deploy a gendered belletristic persona in an attempt to reassert himself.

Tellingly, Charles also declares in this fragment, after describing Mrs Francis ‘launching out in the praise of the unknown Writer’, that he is ‘not at all smoaky – so it went off very well’. At this time, the slang word ‘smoaky’ could signify bad temper, shrewdness, suspicion, ridicule, or jealousy.Footnote 122 Charles probably means that he did not act suspiciously when lending the book to Mrs Francis, thus preserving the secret of Frances’s authorship. But the multiple valences of the word, coupled with his assiduous corrections, suggest that he may have felt envy or chagrin alongside other, more positive fraternal emotions.

I want to draw three more observations out of these fragments as evidence of Charles’s readerly practice. First, his usage of the term ‘vastely much’ indicates a casual yet striking mimicry. Where words are underlined and deliberately misspelled in Burney family correspondence, there is always the possibility that the misspelling is an in-joke, part of the elaborate family dialect (a mixture of slang, pet names, mimicry, and code) that makes their letters such a challenge to edit.Footnote 123 On this occasion, ‘vastely’ is an echo of the distinctive lexicon of the indefatigable Madame Duval, a character in Evelina who makes liberal use of that term: possibly with the spelling altered to imply a strong French accent.Footnote 124 Duval was one of the characters most loved and imitated by the novel’s early readers, and Charles’s letter hints that, like other readers, he couldn’t resist the temptation to ‘perform’ his sister’s memorable antagonist.

Second, we find a hint of identification (rather than performance) in Charles’s remark that ‘the horror & remorse, which must almost necessarily attend such a meeting is very admirably described’. In singling out the confrontation scene between Sir John Belmont and Evelina, Charles largely focuses on Mrs Francis’s sentimental response, but also adds his own assessment of its veracity. Usage of the emphatic ‘must’, immediately qualified by the self-conscious ‘almost necessarily’, hints at first-hand knowledge of such strong emotions, raising the possibility that he may have been thinking of a confrontation with his own father following his disgrace. Although reversing the generational positions, Charles appears to be reading his life, affectively speaking, into Frances’s work.

Other striking aspects of Charles’s treatment of the Shinfield Evelina are his interest in who else is reading the book and his commitment to extending its readership. In the first fragment, Charles refers to ‘the Parson’ (perhaps the Rev. Mr. Jane, who Charles satirised in his poetry as ‘the little Welsh curate’) reading Evelina, while in the second, he describes Mrs Francis’s response. This indicates that Charles was alert to the novel’s readership within Shinfield and suggests that he was actively subletting his own borrowed copy before returning it to his sister (‘This shall accompany Evelina’). This would be consonant with his later documented practice in Scotland.

Finally – though Charles does not mention it in these fragments – we should note that his first reading of Evelina acted as a stimulant to poetic composition. As I show in Section 3, the all-important sonnet that he reports ‘prefixing’ to Evelina and lending around Aberdeen was first composed in Shinfield. Its first title was not ‘The Female Reader’ but ‘Sonnet Written in a Blank Leaf of Evelina’, and its likely first recipient was Frances Burney herself.

2.2 The Aberdeen Evelina

In the spring of 1779, Charles announced to Frances that ‘Evelina is in Aberdeen’.Footnote 125 Having returned the Shinfield Evelina to its author, once settled in Aberdeen, he again turned to ‘a Circulating Library’ to obtain his own set – this time successfully. Charles does not name the library, but there were two in operation in Aberdeen at this time: John Boyle’s and Alexander Angus’s.Footnote 126 While to my knowledge no catalogue survives for Boyle’s, there are several for Angus’s, the ‘showiest shop in town’ and ‘favourite rendezvous of many of the respectable citizens of Aberdeen’, which was based at the Narrow Wynd.Footnote 127 One catalogue is dated 1779 and features an entry for Evelina: Or, the History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World, priced at nine shillings.Footnote 128

Charles’s account of his lending practice is quoted in my Introduction and will be interrogated in Section 5, but we are now in a better position to extract a few key features. In Aberdeen, he establishes a lending network on a broader scale than his Shinfield circle, and when gathering responses, he is particularly interested in which characters draw readers’ admiration. Advertising his sister’s authorship is a key component of his promotional practice: ‘They are all in raptures with it – & all longing to see you … [Gordon] says, he is sure that Miss Burney’s pen would have made a great deal of it.’Footnote 129 Consonant with the fact that Frances Burney’s authorship was now common knowledge, this differs from his practice in Shinfield, where he kept the authorship a secret from Mrs Francis. Finally, one of his compliments – ‘Every body is surprised at the Performance’ – is, like his comment about not being fond of novels, decidedly backhanded, especially when followed by a boast about his own ‘prefixed’ poem, which ‘likewise had its admirers’. These concluding lines recall the interplay of various dynamics in Charles’s response to the Shinfield Evelina, and hint at a feature of his circulatory practice addressed in the next section: his desire to not only share space with his sister on the page but also superimpose his literary identity alongside or over hers.

The Willoxes, Gordons, and Gerards are not the only members of Charles’s Aberdeen circle to whom he promotes the novel and its author. Letters from his tutor James Dunbar and friend Percival Stockdale also indicate that they had read or discussed the novel with Charles. Both men write from London, where he has encouraged them to pay a visit to his family, and both refer to the flesh-and-blood Frances Burney herself, when they encounter her, as ‘Evelina’.Footnote 130 This conflation of the author with the heroine indicates that Charles not only promoted his sister’s novel but also encouraged prospective readers to identify her with her protagonist.

2.3 The Banff Evelina

When Charles went on a walking tour around North East Scotland in the summer of 1780, he took a set of Evelina with him. Staying at the home of his friend James Likly, he notes, ‘read[ing] Evelina to the Misses [Likly’s sisters], neither of whom have charms to promote flirtation’.Footnote 131 He left his set in Banff, in the custody of the more desirable Mary Rose, when he returned to Aberdeen in the autumn of 1780, and did not recover it until spring 1781 (if at all).Footnote 132 The novel was clearly on his mind as he travelled, since he uses it to characterise the people he meets along the way. A Mrs Admiral Gordon is ‘a little in the Mrs Beaumont style, all for the nobility’; this is a reference to the ‘Court Calendar bigot’ Mrs Beaumont in Evelina.Footnote 133

It is unlikely that the set Charles took to Banff in the summer of 1780 was the same one circulated in Aberdeen in the spring of 1779.Footnote 134 Instead, I think it likely that it was a third copy, which Charles again obtained directly from Frances Burney in London. My evidence for this is contained in two separate letters. As already mentioned, when Charles’s tutor James Dunbar travelled to London in the spring of 1779, Charles arranged for him to pay the Burney family a visit. ‘You have long ere this, I take it for granted, seen Mr Dunbar,’ he writes to Frances. ‘… Pray will you give into his care the set of Evelina’.Footnote 135 Furthermore, in a letter of 24 May 1779, Dunbar reports back to Charles, ‘I am just come from dining at Dr. Burney’s, where I have met wh the utmost Civility – I shall remember your commission about Evelina, more interesting surely from having seen the Original’.Footnote 136 The implication is clear: in 1779 Charles had asked Dunbar to bring him a set of Evelina that was currently in the possession of his family, and so it was probably this family set that he took to Banff in 1780.

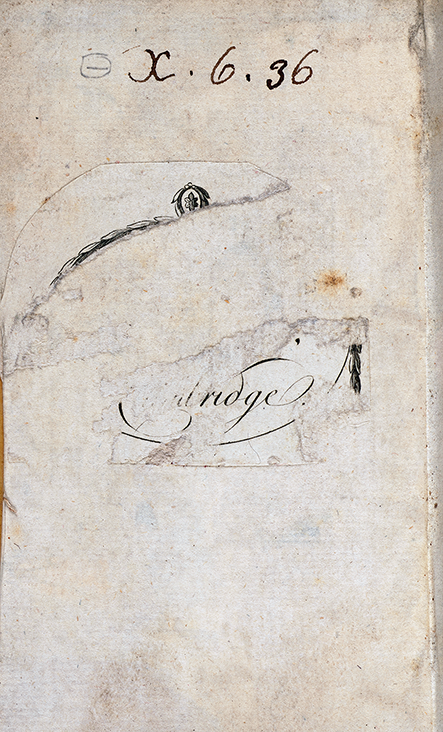

2.4 The SC Set: Markings and ‘Moor Fowls’

In the University of Aberdeen’s Special Collections, there is a battered three-volume set of the 1779 third edition of Evelina.Footnote 137 Its early provenance, bibliographically speaking, is a mystery. Supralibros, pressmarks, and bookplates indicate only the ownership of King’s College and of the University of Aberdeen (formed after King’s and Marischal combined in 1860).Footnote 138 The Library’s manuscript catalogues provide only the barest information, indicating that the set entered the King’s collection before 1848.Footnote 139 In short, there is no concrete bibliographical evidence that this is not one of Charles Burney’s Evelinas: but there is also no evidence that it is. However, idiosyncratic marginal annotation within the first and third volumes suggest strongly that this is the very set which Charles took with him to Banff.

2.4.1 Markings

The most notable thing about the volumes is how roughly they have been treated. On the title page of the first volume, we find heavy ink smudges in two separate places, while on the facing verso there is light pitted residue, roughly positioned in a mirror image to the heaviest smudging (see Figure 2). More smudges and blots, both brown and black, occur frequently throughout the three volumes. There are numerous grease stains, probably often deposits left by human fingers. Pages are occasionally rumpled or folded over, while one leaf (pages 71–72 in the first volume) is badly mutilated, with three-quarters of the page ripped away on a diagonal. On page 46 of the second volume, there is an abrasion in the paper, the edges of which appear to be singed; perhaps a burn from a hastily extinguished cinder. A hole in the page occurs on page 85 of the second volume.

Figure 2 Title page and preceding verso.

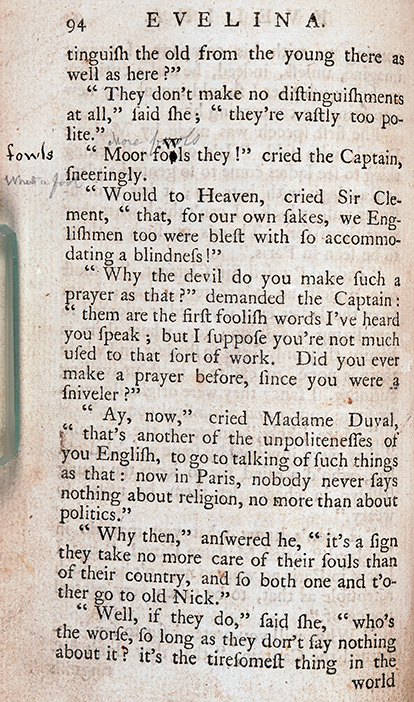

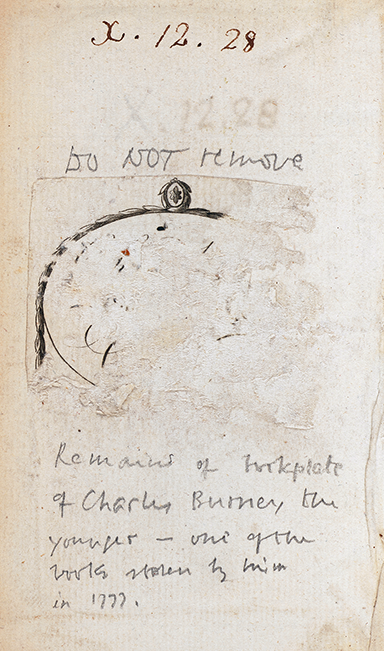

Not all markings are accidental. Doodles and underlines abound. There are also several annotations, made in both black ink and faded pencil. On page 94 of the first volume, alongside a debate between Madame Duval and Captain Mirvan about age and beauty, a brief marginal dialogue seems to have taken place between two readers (see Figure 3). The text under annotation is the Captain’s exclamation, rendered in this edition as ‘Moor fools they!’ ‘Moor’ is a printer’s error; in subsequent editions, the phrase would read, ‘More fools they!’ [Italics mine].

Figure 3 Marginalia concerning moor fowl.

It would not be unusual to find a reader hand-correcting such a typo; a tendency elegantly described by the Multigraph Collective as ‘testimony to an editorial mind-set fostered by print culture’.Footnote 140 Indeed, there are incidences of such corrections in this very set – for example, in the third volume, someone has corrected the antiquated usage ‘you was’ to the more modern ‘you were’. However, in the case of 1:94, a marginal annotator, writing in black ink, has responded chaotically rather than correctively. Instead of correcting the misspelling ‘moor’ to ‘more’, they have deliberately amended ‘fools’ to read ‘fowls’. The word ‘fowls’ is then written a second time in the margin, perhaps to avoid any misunderstanding. ‘More fools’ has become ‘Moor fowls’, in an intriguing instance of what the Multigraph Collective terms ‘disruption’, whereby a satirical reader ‘turn[s] the fallible, error-prone nature of printing to their advantage’.Footnote 141 A faint pencil hand, presumably later, has tried to correct the disruption, replacing ‘Moor fowls’ with ‘More fools’ and writing in the margin, ‘What a fool’. It is unclear whether this remark refers to the Captain, the subject of his utterance, or the disruptive annotator.

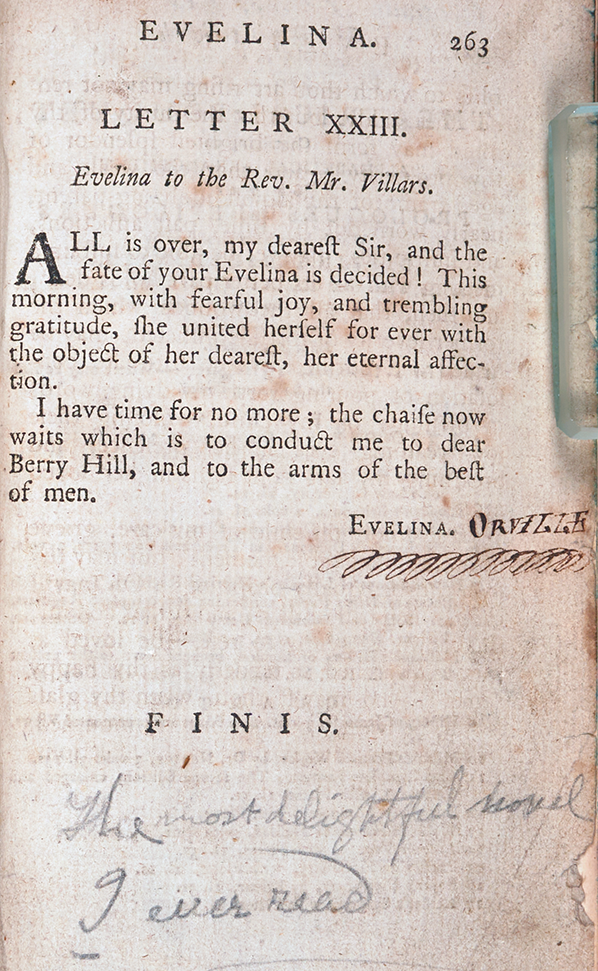

A black ink hand and a pencil hand – possibly, though not certainly, the same ones – meet once again on the final page of volume 3. If indeed the same annotators as those on 1:94, they are in closer accord with their satisfied responses to Evelina’s happy ending (see Figure 4). Beneath the printed ‘FINIS’, the pencil hand provides an approving verdict: ‘The most delightful novel I ever read.’ Meanwhile, the black ink hand attempts to provide the last word on the question of Evelina’s ambiguous surname (possibilities raised throughout the narrative include Anville, Villars, and Belmont). When the protagonist signs her final letter to Mr Villars ‘EVELINA’, the annotator takes advantage of the space afforded by the margin to add, ‘ORVILLE’. A decorative underlining flourish unites the print given name with the manuscript surname. The annotator, clearly just as alert as modern critics to the significance of naming within the plot, thereby uses the annotation to elevate Evelina’s conjugal identity as wife to Lord Orville above the other roles she has played throughout the narrative (daughter to Mr Villars or Sir John Belmont, brother to Macartney, granddaughter to Madame Duval, etc.). In doing so, they stake a claim to ‘insider knowledge … that qualifie[s] them as collaborators in the finalization of the book’.Footnote 142

Figure 4 Marginalia concerning Evelina’s name.

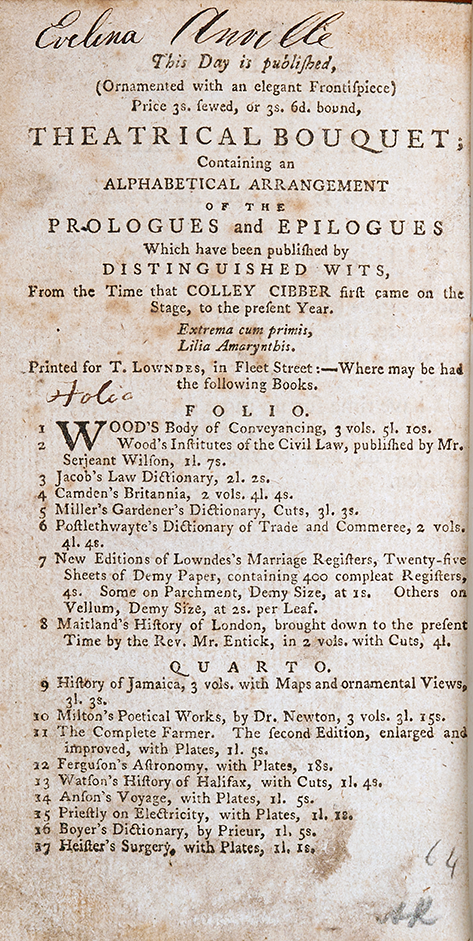

There is one more annotation of significance. In my bibliographical assessment of the SC Evelina, I suggested that the set contains no ownership inscription – but there is one possible, peculiar exception. At the end of the third volume, on an advertisement for a miscellany called the ‘Theatrical Bouquet’ also published by Lowndes, a black ink hand has written at the top of the page, ‘Evelina Anville’ (See Figure 5).

The nature of this annotation is far from clear. However, given its positioning on the paratextual fringe of the volume – alongside an advertisement specifically raising the topic of theatrical performance – it is possibly intended as a joke ownership inscription. Katharina Rennhak has noted how paratexts can ‘swing wide open the door on the threshold between the extratextual and the textual … between authentic prefatorial figures on the one hand and fictive characters on the other’.Footnote 143 In a similar metatextual act of play, the black ink annotator may be indicating that this set of the novel belongs, in some way, to the fictional heroine.Footnote 144