Introduction

Tell Abraq is a stratified site located along the western coast of the United Arab Emirates, which uniquely showcases elements of all the main chrono-cultural phases of south-east Arabian protohistory from c. 2500 BC to possibly the fourth century AD (Potts Reference Potts2000) (Figure 1 & Table 1). Throughout this period, distinctive cultures developed in south-east Arabia. Despite evidence of socioeconomic complexity, the state-level organisation of neighbouring polities was never established, yet these cultures were involved in intricate commercial networks.

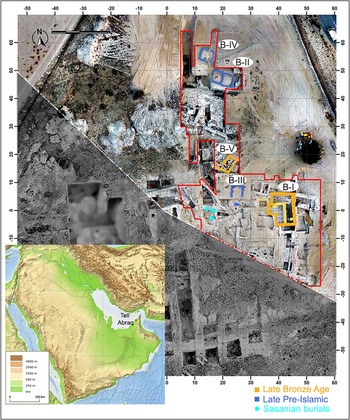

Figure 1. Tell Abraq at the end of the 2024 season, and a chronology for the region and site. The red line delimits the area investigated by the IAMUQ (figure by author).

Table 1. Main periods in south-east Arabian archaeology and corresponding main structures at Tell Abraq.

NB: items in italics not discussed in text.

Investigations by the Italian Archaeological Mission in Umm al-Quwain (IAMUQ) in the eastern part of the site, ongoing since 2019, aim to re-evaluate the site’s evolution and regional and supra-regional trade connections (Degli Esposti et al. Reference Degli Esposti, Borgi, Pellegrino, Hussein Kannouma, El Fadi, Gannon, Al Shohof and Al Ghoul2023). To date, findings have filled gaps in the diachronic sequence established by earlier investigations, highlighting remarkable continuity (Degli Esposti et al. Reference Degli Esposti, Pellegrino, Borgi, Barchiesi and Hussein Kannouma2025). Recent discoveries illustrate two main phases of cross-cultural contacts in the second half of the second millennium BC and the first–third centuries AD. Additional data on the arrival of exotic goods are being collected at the nearby necropolis of Abraq 2, dated to the Late Bronze Age (1600–1300 BC) and Iron Age (1300–300 BC).

The Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age

The magnitude and nature of human activity at the site varied over time (Degli Esposti et al. Reference Degli Esposti, Pellegrino, Borgi, Barchiesi and Hussein Kannouma2025). The Late Bronze Age and the initial phase of the Early Iron Age, c. 1500–1100 BC, witnessed conspicuous activity (Magee et al. Reference Magee, Händel, Karacic, Uerpmann and Uerpmann2017; Barker Reference Barker2018), including construction of B-I (Figure 2) and B-V, a complete L-shaped room made of mudbricks and stones (probably a workshop).

Figure 2. B-I and adjacent structures, looking west (figure by F. Borgi).

B-I is a large stone building erected in the late fourteenth to early thirteenth centuries BC (Degli Esposti & Pellegrino in press). The extensive use of hard mortar as a structural binder and for rendering horizontal and vertical surfaces is unparalleled in the region. The associated ceramic assemblage includes a high proportion of pottery likely imported from south-east Iran, together with a coarseware typical of the local Late Bronze Age. The repertoire of imported pottery is dominated by medium-size storage jars made in a dense, sandy fabric (Figure 3a & c), macroscopically similar to the ‘FIG’ class defined by Priestman (Reference Priestman2005). The exogenous provenance of two such jars is attested by the cylinder seal impressions on their bodies, iconographically linked to South Mesopotamian and Elamite repertoires (Majchrzak & Degli Esposti Reference Majchrzak and Degli Esposti2022) (Figure 3a & b); the presence of jar holes of corresponding size in the original floor of B-I strengthens the association. The uniqueness of the building implies external influences, probably from the wider Gulf area. Despite the storage jars, the prominence of B-I suggests it was more than a simple warehouse; a potential role in the control and redistribution of foreign goods is supported by the rarity of imported sherds in other areas of the site.

Figure 3. a) Seal-impressed jar from B-I and detail of the Elamite-inspired seal impression; b) South Mesopotamian iconography impression on another jar from B-I; c) detail of the fabric from a cross-section of a similar jar (drawings by S. Spano, figure by author).

The excavations also provided evidence for a limited occupation during the Early Iron Age II period, c. 800–500 BC, comprising a domestic space and kilns/ovens sometimes reused as waste pits. The absence of imported goods suggests a period of decreased external connections.

The late pre-Islamic period

B-II and B-IV are dated between the fourth and second centuries BC, around the start of the late pre-Islamic period. During the first–third centuries AD, residential use of the site ceased, and it hosted only a small shrine with an open-air altar (B-III, Figure 4). Occasional graves date to the Sasanian period, between the fourth and seventh centuries AD (Degli Esposti et al. Reference Degli Esposti, Borgi, Pellegrino, Hussein Kannouma, El Fadi, Gannon, Al Shohof and Al Ghoul2023).

Figure 4. B-III with inset detail of the collapsed altar (figure by F. Borgi & M. Degli Esposti).

Flourishing trade connections are associated with the use of B-III. Several clay and bronze figurines (Pavan & Degli Esposti Reference Pavan and Degli Esposti2023), local bronze coins, imitations of Roman aurei (gold coins), stone statues and an inscription in Aramaic (Degli Esposti et al. Reference Degli Esposti, Pellegrino, Borgi, Barchiesi and Hussein Kannouma2025), indicate links with South Arabia, the larger Arabian Peninsula, India, the Roman Levant and southern Mesopotamia (Figures 5 & 6), and hint at an active overland network alongside the maritime one. The finds and context suggest the cultic use of the building and the votive nature of the objects as offerings, as at the Shamash temple at nearby Ed Dur (Haerinck Reference Haerinck2011). B-III might represent a waypoint where traders sought the favour of deities or offered thanks for successful voyages.

Figure 5. Finds from B-III: a & b) copper-alloy figurines; c) moulded terracotta figurine; d) stone statue; e) stone with Aramaic inscription; f, g & h) terracotta animal figurines; i & j) terracotta human heads (photographs by F. Borgi & M. Degli Esposti).

Figure 6. Local bronze coins, imitation aurei and a silver bracelet offered together inside a pottery bowl (not visible); right) detail of the three aurei (photographs by author). The scale for the coins is 10 mm.

Conclusions

Tell Abraq offers valuable insights into the long-term evolution of maritime and overland connections in south-east Arabia. After the Early Bronze Age, there were two periods of significant inflow of exotic goods, coinciding with external political influence in the Gulf: the Kassites and Elamites in the second millennium BC (Potts Reference Potts2006); and the Characene kingdom in the first two centuries AD (Gregoratti Reference Gregoratti2011). While the latter connection, attested by the stone statues and Aramaic inscription, was likely only commercial, B-I might reflect a tighter external control of trade, possibly exerted by representatives at the site.

Acknowledgements

The Tourism and Archaeology Department of Umm al Quwain and its chairman, Shaykh Majid b. Saud Al Mu‘alla, provided invaluable support for this project.

Funding statement

The Abraq Research Project is supported by the Tourism and Archaeology Department of Umm al Quwain. The 2020, 2021 and 2022 field seasons were funded by a De Cardi Award granted to the author by the Society of Antiquaries of London. The 2025 activities were funded by the Zayed National Museum Research Fund.