In recent years, the field of literary studies has undergone a “translingual turn.”Footnote 1 Scholars have increasingly moved away from the concept of a normative national linguistic space to devote attention to previously neglected manifestations of multilingual creativity.Footnote 2 Research of this type has thus far mainly focused on the medieval and early modern periods or on the work of twentieth- and twenty-first-century modernist and post-modernist transnational migrants.Footnote 3 By comparison, the nineteenth century has remained a “blind spot” or “dark continent” in the exploration of multilingual literature, probably because the monolingual national paradigm with its Herderian cultural framework emerged precisely during this time.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, this period provides a fertile ground for the exploration of literary multilingualism. Russia’s most important female poet of the nineteenth century, Karolina Karlovna Pavlova, née Jaenisch (1807–1893), presents a particularly salient and thus far little explored case of an author who defies the seemingly organic link between language and national belonging posited by German romantic philosophers and their Slavophile disciples.

Pavlova’s reputation underwent several dramatic ups and downs. As a respected member of Russia’s literary establishment in the 1840s, she published her poetry in the leading journals of the day, yet she was publicly disparaged and driven out of Russia in the 1850s and spent the rest of her life in increasing obscurity and poverty. A turning point in her posthumous rehabilitation came in the early years of the twentieth century, when the Russian Symbolists championed her as a poetic innovator and Valerii Briusov published a two-volume edition of her works in 1915. Even though two more editions of her collected poetry followed in 1939 and 1964, Pavlova was treated as a marginal figure during the Soviet period and remains so in present-day Russia. A second renaissance occurred in the late twentieth century in Western academic circles, where her cause was taken up by Slavic scholars who approached her work through the lens of gender and feminist criticism.Footnote 5

Despite this renewed interest in Pavlova, a crucial aspect of her oeuvre that has received only scant scholarly attention is her multilingualism. Pavlova has been almost universally, but incorrectly, reduced to the status of a “Russian poet.” A laudable exception was the German scholar Barbara Lettmann-Sadony, who defined Pavlova in the title of her 1971 doctoral thesis as “a poet of Russian-German reciprocity.”Footnote 6 However, such a designation is still inadequate. The Russian-German binary obscures the fact that Pavlova was not a bilingual, but a trilingual poet writing in Russian, German, and French. Moreover, translations between multiple languages constituted an important component of her literary activity. Pavlova strategically deployed her multilingualism in the service of a literary career that transcended the territorial and linguistic confines of her native Russia, making her comparable to later translingual and trilingual writers like Vladimir Nabokov. At the same time, her perceived foreignness prompted her Slavophile contemporaries to question her status as a bona fide member of the Russian imagined community, leading to her eventual exile from the Russian empire.

Perhaps surprisingly, some basic facts about Pavlova’s multilingualism remain unclear or have been misrepresented. This includes the question as to which language should be considered her native tongue. The scope of her linguistic repertoire has also been reported in various and contradictory ways. A first step has to consist in separating fact from fiction. Further topics that will be explored in this article include the psychological import of Pavlova’s multilingualism on her romance with the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz, the strategic stakes of her career as a trilingual poet and translator, the perception of her as a non-Russian, and her own conflicted attitude toward her Russianness. As I will argue, Pavlova’s native command of three languages facilitated a fluid and performative ethnolinguistic identity that was increasingly at odds with the tenets of nineteenth-century monolingual nationalism.

Pavlova’s Multilingual Repertoire

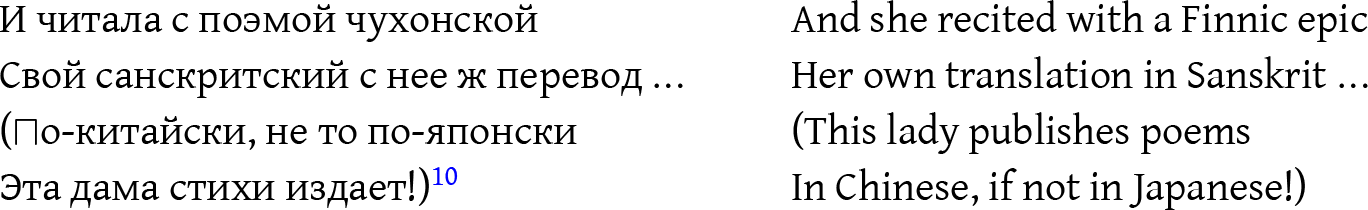

Among her contemporaries, the young Karolina Jaenisch had a reputation as a language prodigy and somewhat of a show-off. In a letter to his brothers, the poet Nikolai Iazykov wrote about her in 1832: “The above-mentioned maiden is a rare phenomenon, not only in Moscow and Russia, but under the sun. She knows an extremely large number of languages: Russian, French, German, Polish, Spanish, Italian, Swedish, and Dutch—she is constantly sticking out all these tongues, bragging of them.”Footnote 7 This list of languages allegedly mastered by Pavlova has been uncritically accepted and repeated by later scholars.Footnote 8 The ironic tone of Iazykov’s letter should put one on guard, however. Iazykov’s disparaging manner is in line with the dismissive and condescending approach taken by some memoirists toward Pavlova. Her penchant to parade her linguistic prowess is also mentioned by Avdotˊia Panaeva (A. Ia. Golovacheva), a visitor to Pavlova’s Moscow salon, who described her first encounter with the hostess of the house as follows: “During the conversation she constantly cited stanzas of poetry in German from Goethe, from Byron in English, from Dante in Italian, and in Spanish she adduced some kind of proverb.”Footnote 9 A public spat between Pavlova and Golovacheva’s husband Ivan Panaev on the pages of the journal Sovremennik inspired Evdokiia Rostopchina, Pavlova’s poetic rival, to compose a mocking epistle in seven stanzas. The third stanza takes aim at Pavlova’s multilingualism:

It is obvious that Rostopchina’s enumeration of exotic languages (chukhonskii is a derogative term for Finns and Estonians) serves to mock Pavlova, who knew neither Finnish nor Sanskrit, let alone Chinese or Japanese. By the same token, one wonders whether Iazykov’s list of languages allegedly known by Pavlova is not tongue in cheek as well. There is no indication from any other source suggesting that Pavlova knew Swedish and Dutch, as Iazykov claims. On the other hand, Pavlova did know English, which Iazykov failed to include in his list.

We might pause here for a moment to wonder why Pavlova’s contemporaries reacted to her multilingual prowess with such irony and vitriol. One reason certainly had to do with misogynistic condescension: for a woman to publicly display her learnedness was deemed unseemly and presumptuous. An excess of education risked making her “unfeminine” and unattractive in the eyes of men. Pavlova herself made this point explicitly in her tale “Za chainym stolom” (At the Tea Table), published in 1859, where the heroine notes that an intelligent woman is considered by society as “some kind of monster.”Footnote 11 In addition, Russian chauvinism also played a part. By presenting her rival as a sort of multilingual freak, Rostopchina implies that Pavlova does not qualify as a true Russian.Footnote 12 The array of exotic languages veils and simultaneously exposes Pavlova’s alleged ethnolinguistic identity—Rostopchina’s unspoken point is that her rival, née Karoline Jaenisch, is really a German. This Germanness makes her a figure of ridicule. Pavlova certainly was aware of being a target of anti-German prejudice and felt defensive about it. The negative attitude toward Germans transpires on the very first page of her novel Dvoinaia zhiznˊ (A Double Life), where one of the main characters exclaims “I can’t stand all these Germans and half-Germans.”Footnote 13

We are still left with the question of which languages were known to Pavlova. Boris Rapgof, in his 1916 biography, claims that, in addition to Russian, she knew German, French, English, and Italian as well as some Polish and Spanish. He references Panaeva’s testimony as a source, as well as the evidence of Pavlova’s translations.Footnote 14 Aside from German, French and Russian, which served as both source and target languages of her translations, Pavlova also translated from English, Polish, Ukrainian, Italian, and occasionally Danish (Oehlenschläger) and Ancient Greek (Aeschylus). This does not necessarily mean that she “knew” all these languages, of course.Footnote 15 She may have used French or German as a relay language when translating from Danish or Greek into Russian, for example. Some of her poems are introduced by epigraphs in English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, or Latin. But, again, this does not necessarily indicate an active command of these languages.

In sum, all we can say with certitude is that, like many polyglots, Pavlova had a knowledge of several languages with various levels of passive and active competence that are difficult to determine in detail. What remains without doubt is her “native” command of three languages—Russian, German, and French—in which she was able not only to converse fluently, but also to write compelling poetry.

Pavlova’s Balanced Trilingualism

Pavlova benefitted from a multilingual upbringing. In his biographical introduction to the 1915 edition of her works, Valerii Briusov claims that by age five she already expressed herself fluently in four languages.Footnote 16 He does not name them, and neither does he provide any source to support this assertion. While Pavlova’s childhood languages undoubtedly included Russian, German, and French, it is less clear what the fourth language would have been. English seems the most likely candidate, but there is no confirmation that Pavlova grew up speaking English. In the memoirs that she left about her childhood Pavlova addresses the language question only very sparingly and indirectly. We learn that when the family was fleeing from the French invaders in 1812, her mother admonished her five-year-old daughter not to speak French in public. The fact that Karolina addresses her mother as “Maman” suggests that the primary language of communication between mother and daughter (and thus Pavlova’s “mother tongue”) was likely French.Footnote 17

The ethnic background of Pavlova’s mother is not entirely clear. Pavel Gromov, in his introduction to the 1964 edition of Pavlova’s poetry, asserts that her mother’s family was French and English.Footnote 18 This information seems to derive from the unfinished memoirs of Pavlova’s son Ippolit, who presents his maternal great-grandfather as the son of a French woman and an Englishman who eloped together to Holland. After the premature death of his parents, he was raised in France by his French grandmother and later ended up in Russia, where he became the “father of a poor family.” One of his daughters was Pavlova’s mother Elizaveta.Footnote 19 If this story is true, Elizaveta would have been French and English on her father’s side (we know nothing of her mother). Even if she did have an English grandfather, however, it is unlikely that English was spoken in the family. The grandfather died long before Elizaveta’s birth, and her father’s dominant language must have been French. There is no indication that Elizaveta either knew English or spoke it to her children. To make matters more confusing, some sources describe Pavlova’s mother as a typical German. In his obituary of Pavlova, Petr Bartenev, the editor of the journal Russkii arkhiv, who had been a visitor of Pavlova’s salon in the 1840s, claimed that both of her parents were German.Footnote 20 Briusov, in his introduction to Pavlova’s collected works, calls Pavlova’s mother a “good German woman” (dobraia nemka).Footnote 21 Ivan Panaev, another guest at Pavlova’s salon, presents the mother as a caricature of a prim German Hausfrau who was “dressed with German neatness and punctiliousness” (nemetskoiu akkuratnostˊiu i shchepetlivostˊiu).Footnote 22

Perhaps the ostentatious “German” demeanor of Pavlova’s mother was a form of assimilation to her husband. Doctor Karl Jaenisch, a professor of physics and chemistry at the Moscow Medical Academy and graduate of the University of Leipzig, was of German descent. His family had lived in Russia for several generations, however, and as a Russian German, he was of course bilingual in both languages. One has to assume that Karolina acquired her command of German from her father, who homeschooled his daughter. The German language is never mentioned in Pavlova’s childhood memoirs aside from a jocular reference to tea “an und für sich.”Footnote 23 Rapgof argues that Pavlova’s “native language, was, in all likelihood, German,” but it seems more apt to call German her “father tongue,” with French serving as the “mother tongue.”Footnote 24

We can only speculate about the linguistic situation in the Jaenisch household. Most likely, the commonly spoken language between parents and children was French (as appropriate for an elite comme il faut milieu at that time). The private language between father and daughter must have been German. If Pavlova’s mother knew German as well, the family may have code-switched between French and German, or between French, German, and Russian. Russian was the language spoken with servants and nannies. In her memoirs, Pavlova relates how her nanny exclaimed Gospodi! Gospodi! (Oh my God!) when she saw the burnt city of Moscow.Footnote 25 Like Aleksandr Pushkin—but unlike Vladimir Nabokov, who also grew up, in his own words, as a “perfectly normal trilingual child”Footnote 26 —young Karolina Jaenisch was cared for by a Russian rather than a foreign nanny.

Pavlova’s knowledge of French, German, and Russian since her earliest childhood raises the question whether she mastered all three languages to the same degree, or whether one of them was more dominant. While there was probably little difference in oral proficiency, it is possible that she became literate in Russian later than in French and German. In an autobiographical sketch that Pavlova wrote in October 1864 for the German phrenologist Gustav Scheve in Dresden, she states that she did not receive any formal education in Russian in her youth, since at that time “in the upper ranks of society knowing Russian was considered highly unnecessary.”Footnote 27 She claims that she began to study Russian grammar autodidactically three years after her marriage, when she appropriated the language as a tool for poetic writing in a laborious eight-year process.Footnote 28 Pavlova’s first publications were in German and French rather than in Russian, but the delayed acquisition of Russian literacy does not seem to have affected her competence in that language. Her poetry and translations give the impression of an entirely native command of all the three languages she wrote in.

Attempts by twentieth-century scholars to pose Russian as Pavlova’s dominant language or, conversely, to ascribe to her Russian a somehow deficient and “foreign” quality fail to convince. Barbara Lettman-Sadony has argued that Pavlova’s German was weaker than her Russian because her German rhymes, compared to those in Russian, tend to be too unconventional.Footnote 29 But innovative rhyming was precisely one of Pavlova’s characteristic features as a poet both in Russian and German. It can hardly be interpreted as a sign of deficient linguistic competence. A few infelicitous expressions in German noted by Lettman-Sadony are not sufficient to declare that her German was inferior to her Russian. Lettman-Sadony also mentions that in some cases Pavlova improved a mediocre German poem, for example Ferdinand Freiligrath’s “Der Biwak,” by translating it into superb Russian.Footnote 30 However, this does not constitute proof that her Russian was better than her German. Munir Sendich, in his 1968 PhD thesis, took the opposite tack from Lettmann-Sadony by claiming that Pavlova’s Russian, possibly because of her “origin” and “her constant translating activity from and into many different languages” has at times a foreign tinge and “cannot be considered unimpeachably Russian.”Footnote 31 The one example he provides, while indeed somewhat clumsy, hardly allows the generalization that Pavlova’s command of Russian was less than native. The “clash” of different lexical elements in her Russian style noted by Sendich could also be attributed to the formal innovation and experimentation that later endeared Pavlova to the early twentieth-century Russian modernists.

While Pavlova’s command of German, French, and Russian was equally native, the question nevertheless arises whether these languages fulfilled functionally equivalent purposes for her. Did a particular language have emotional or psychological connotations that would have prompted its preferred use in a given situation? It stands to reason that specific languages would have been chosen for specific interlocutors. For example, as stated before, French served in all likelihood as the “mother tongue” and German as the “father tongue.” In some cases, Pavlova had a choice between several options when communicating with a particular individual. Her selection of a specific language could therefore take on a meaningful metacommunicative significance. This can be demonstrated by looking at her romance with the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz, to which we now turn.

The Multilingual Affair with Adam Mickiewicz

Perhaps significantly, Pavlova’s love affair with Mickiewicz grew out of a language teaching situation. The Polish poet, who was at that time exiled to Moscow, was engaged as the Polish tutor of young Karolina Jaenisch at her own request. The two soon developed deeper feelings for each other, but Mickiewicz’s marriage proposal supposedly foundered on the resistance of a rich childless uncle, who threatened to disinherit Karolina if she married a penniless and politically “dangerous” poet.Footnote 32 Mickiewicz, like Pavlova, was a polyglot.Footnote 33 Between them, Pavlova and Mickiewicz shared multiple languages, including French, German, Russian, English, Italian, and Polish (with Pavlova’s active command of the latter probably remaining limited). Two letters of Pavlova to Mickiewicz have survived. The first one, written on February 19, 1829, after Mickiewicz had departed to St. Petersburg and remained silent for ten months, demanded clarity from him about his intentions and asked for an urgent meeting. The second letter, written on April 5, 1829, after their final encounter and break up, is a farewell message.Footnote 34 Interestingly, the first letter is written in French, the second in German. Why?

French was the language that Pavlova and Mickiewicz conversed in when they were together in polite society, and it is therefore not surprising that she would use it for her correspondence. The first letter also contains a reference to Polish, though, suggesting that this language served as a sort of private code between the two lovers. Pavlova writes:

Je ne me sens bien que lorsque je suis seule avec vous; alors je vous parle dans cette

langue chérie, qui est pour moi une musique touchante et délicieuse; dans ces instants je connais la joie mais cette joie a presque toujours les larmes aux yeux” (I only feel well when I am alone with you; then I talk to you in this beloved language, which is for me a touching and delicious music; in these moments I know joy, but this joy has almost always tears in its eyes”).Footnote 35

Significantly, she signs the letter off in Polish: “Bądź zdrów, kochany!” (Be well, beloved!).Footnote 36

Pavlova’s letter is written in a highly rhetorical and clichéd literary style. She begins and ends by addressing Mickiewicz with the polite and formal “vous.” However, in the middle, where she declares her passionate and undying love for the Polish poet, she unexpectedly transitions to the intimate “tu.”Footnote 37 This switch from the formal to the informal register back to the formal imitates a famous fictional model, which was also allegedly written in French: Tatiana’s letter to Onegin in Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. The third chapter of the novel with Tatiana’s letter appeared in October of 1827, sixteen months before Pavlova composed her own letter to Mickiewicz. Like Pushkin’s Tatiana, Pavlova’s letter-writing persona ascribes existential significance to her projection of an idealized beloved. The parallel with Pushkin’s novel signals perhaps a secret doubt, since Onegin hardly turns out to be a man worthy of Tatiana’s exalted affection. In any event, Pavlova’s letter illustrates how she self-consciously placed her linguistic choices into a context of literary fiction.Footnote 38

The second letter was written after Mickiewicz met with Pavlova in Moscow to tell her he wanted to be “just friends” (which, incidentally, is also how Onegin responds to Tatiana’s letter). Pavlova’s claim to remain calm and stoic over the inevitable separation clashes with the highly emotional content of the letter. This time, Mickiewicz is addressed with the intimate “du” throughout. Pavlova asserts her eternal love for him and proclaims once again that her happiness will be assured by the fact of having met and loved him. However, her seeming equanimity is punctured by passionate feelings that, as Pavlova recognizes, cannot be adequately expressed in (any) language. Her letter ends with the words “Es muss doch sein—lebe wohl, mein Freund!—ich weiß ja, dass du mich liebst …—Lebe wohl …” (Yet it has to be—fare well, my friend!—I know, after all, that you love me …—Fare well …).Footnote 39

Why did Pavlova choose German as the language of her farewell letter to Mickiewicz? Most likely, she felt that it provided a more intimate means of communication than French, the public language of polite society. Polish, the language that brought the two lovers together, would have been an even more meaningful choice, but Pavlova’s command of the language was probably not up to the task (Mickiewicz’s own farewell message to Pavlova consisted of a poem written in Polish). Significantly, the repeated words “lebe wohl” at the end of Pavlova’s German letter translate the Polish formula at the end of the French letter. Another of Pavlova’s native languages known to Mickiewicz would have been Russian, of course, but Pavlova seems to be going out of her way to avoid using it with him. She is no doubt aware of Mickiewicz’s Polish patriotism and resentment of Russian imperialist oppression. While Pavlova ended up translating several of Mickiewicz’s works into German and French, she never translated him into Russian. This, then, left German as the language of Pavlova’s final message to the Polish poet, even though it seems unlikely that they had used it much in their previous communication. An additional psychological factor in favor of choosing German may have been that, as Pavlova’s “father tongue,” it was connoted with another powerful male presence in her life.

An alternative explanation for Pavlova’s use of German would be that, in a moment of extreme emotional stress, she resorted to the language that came most naturally to her for expressing her feelings. In an article published in 1891, the Polish scholar Józef Tretiak argued that Pavlova’s choice of German was “one more piece of evidence that the letter came from the depths of her heart.”Footnote 40 According to this theory, when faced with the “ineffable” and the danger of complete verbal breakdown, the language of last resort was the one lodged most deeply in Pavlova’s psyche. This would indicate that German was her dominant language, at least when it came to verbalizing her emotions. Personally, I do not find this thesis particularly convincing. Had Pavlova’s wayward lover been a Russian rather than a Polish poet, there is no reason to assume that she could not have expressed her feelings in Russian. Aside from the political problem of addressing Mickiewicz in Russian, another factor was the literary quality that Pavlova strove to impart to her letters. In 1829, she was probably more literate in French and German than she was in Russian, which would have made the composition of a polished literary text in that language more challenging. Pavlova’s linguistic choices need to be considered in their situational contexts rather than by ascribing essentialist qualities to particular languages.

Multilingualism itself was certainly an important and crucial ingredient of Pavlova’s relationship with Mickiewicz. Her involvement with the Polish poet not only enabled her to acquire a new language, but also to showcase her already existing linguistic repertoire. Interestingly, this also included the use of English. Mickiewicz’s son reports that, in addition to the two letters, he found among his father’s possessions Pavlova’s portrait and a curl of her hair accompanied by these lines:

Though many a gifted mind I meet,

Though many a friend I see,

To live with them is far less sweet,

Than to remember thee.Footnote 41

Pavlova is citing here, in a slightly altered form (replacing “we” with “I”) the final four lines of the poem “I Saw Thy Form in Youthful Prime” by Thomas Moore, a poet whom she later translated into French and Russian.Footnote 42 The keepsake suggests that Pavlova wanted Mickiewicz to remember her not as a Russian or a Russian German, but as a cosmopolitan speaker of multiple European languages.

Pavlova’s Trilingual Poetic Career

Multilingualism and code-switching between different languages turned out to be a fundamental factor in the unfolding of Pavlova’s own poetic career, which began in German and French. Her biographer Boris Rapgof explains this choice with the fact that German was, after all, her native tongue, and French, the language of high society in which she aimed to make an impression.Footnote 43 This argument rests on the romantic assumption that poetic writing is indelibly and naturally embedded in the native language and milieu. But, as we have seen, even if this were the case, it seems problematic to posit German as Pavlova’s primary tongue. Rather, she grew up with three languages simultaneously. Furthermore, even though French was widely spoken in elite Russian society, the “Golden Age” poets with whom the young Karolina Jaenisch hobnobbed in Moscow’s salons wrote their poems in Russian, not in French. If Pavlova wanted to be taken seriously as a poet in Moscow’s literary circles, why did she not do the same?

One reason that hindered Pavlova from writing in Russian, at least initially, may have been her lack of formal schooling in that language. In addition, though, Pavlova’s choice of German and French could also be interpreted as a strategic decision based on her ethnicity and gender. As Catriona Kelly has argued, Pavlova tried to use her outsider status to her advantage. As she puts it: “It is tempting to attribute [Pavlova’s] remarkable, even unique, achievement in creating herself as a romantic woman poet to her mixed origins, and to speculate that her status as an étrangère, a woman outside the society in which she moved, may to some extent have insulated her, at a subjective level, from the general belief that the composition of poetry was anomalous for women.”Footnote 44 However, simply writing in German and French rather than Russian would hardly have been sufficient. Aside from capitalizing on her outsider status, something else was needed to attract the attention of the Russian literary milieu and its gatekeepers. As Diana Greene has perceptively noted: “I suggest that at the start of her career Pavlova attempted to create an additional form of social literary capital by translating the poetry of her male contemporaries into European languages.”Footnote 45

Resorting to translation was not unusual for a Russian woman of her time. As Wendy Rosslyn has shown, “[t]ranslation was considered less prestigious than original writing and therefore less presumptuous, and it minimized the grounds for accusations of vanity and self-display” (which, as we have seen, was a persistent reproach levelled against Pavlova).Footnote 46 While a familiarity with foreign languages was quite common for an upper-class Russian woman of her time, what distinguished Pavlova from other translators was her ability to translate bidirectionally into and from Russian. In that sense, she proved to be genuinely useful to her male colleagues by helping to spread their fame beyond the confines of Russia, as she did in her first two book publications, Das Nordlicht (Dresden and Leipzig, 1833) and Les préludes (Paris, 1839). The high quality of her translations helped to establish Pavlova’s reputation as a serious literary figure even among those who were unable to read her work. We can see this in a letter that Evgenii Baratynskii wrote to Ivan Kireevskii in 1832: “Please thank dear Karolina in my name for her translation of my ‘Transmigration of Souls.’ I have never been that annoyed that I do not know German. I am convinced that she has translated me beautifully, and I would more happily read myself in her translation than in my original.”Footnote 47 As Baratynskii and Pavlova developed a close friendship, Baratynskii began to pay attention to Pavlova not only as a translator, but also as an original poet. Pavlova later credited Baratynskii with having recognized her poetic talent early on and providing her with much needed encouragement.Footnote 48

Pavlova’s translations prepared the ground for her own recognition as a poet. Das Nordlicht and Les préludes also contained samples of Pavlova’s original poetry written in German and French. By publishing translations and original work side by side, Pavlova signaled that both should be taken seriously as a form of verbal creativity. Interestingly, by including her own original German poems in a volume subtitled Proben der neueren russischen Literatur (samples of newer Russian literature), she also seemed to suggest that it was possible to write “Russian literature” in languages other than Russian.

As Pavlova’s fame as a translator grew, her Russian literary peers began to regard it as a regrettable anomaly that she published nothing in Russian.Footnote 49 Ivan Kireevskii wrote in 1833: “It is a pity that the Russian girl masters the German verse so well. It is even a greater pity to know that she also masters French verse even better. Only in her native tongue (na svoem otechestvennom iazyke) does she refuse to test her ability.”Footnote 50 The German étrangère had morphed into a “Russian girl” who neglected or betrayed her national identity by writing in foreign tongues. It looks like Pavlova’s ploy to become a recognized Russian poet via the detour of German and French had succeeded brilliantly, if indeed this was her plan. Pavlova was now literally being implored to use Russian as her language of poetic creativity. After 1839, this is mainly what she did. Aside from a few German poems and a German comedy later in life as well as substantial translations into German, especially of Aleksei Tolstoi’s dramas and poetry, the bulk of her subsequent original work as a poet and prose writer was done in Russian.

However, the dominance of Russian in Pavlova’s oeuvre is less overwhelming than one could think by looking only at the “canonical” 1964 Soviet edition, which omits most of her non-Russian work. A collection of Pavlova’s German works published in Germany in 1994 fills three entire volumes (and is far from complete).Footnote 51 While no edition of Pavlova’s collected French works has ever come out, her 1839 volume Les préludes contains not only translations from English, Polish, German, Russian, and Italian into French, but also some significant original French-language poems, among them the programmatic “Jeanne d’Arc.”Footnote 52 Pavlova’s French translation of Schiller’s drama Die Jungfrau von Orleans (The Maid of Orleans), which renders Schiller’s German blank verse in rhymed alexandrines, is a stunning accomplishment of poetic virtuosity.Footnote 53 Her translations of Pushkin into German and French from the 1830s have been called unsurpassed by several twentieth-century scholars, who at the same time expressed regret that these translations were unfairly forgotten by posterity.Footnote 54 If we look at translation as a valid and creative form of literary expression (which Pavlova certainly did), her non-Russian writings constitute a no less significant part of her legacy than her Russophone work.

Pavlova’s Contested Russianness: “Razgovor v Kremle” vs. “Mein Vaterland”

Pavlova’s success as a Russian-language poet and novelist did not mean that her Moscow contemporaries accepted her as a fellow Russian. References to her German background, often with pejorative connotations, remained a persistent practice among her Slavophile “friends.” Even though Pavlova’s French was as good as her German and she published two books in that language, nobody labelled her a Frenchwoman, probably because mastery of the French language was expected and accepted from a member of the Russian upper class. Having native command of German, however, was enough to turn Pavlova into a denigrated ethnic “Other.”

In a letter to Iazykov, Aleksei Khomiakov wrote about Pavlova in the early 1840s: “We are pleased by her work. It is only unpleasant that, however one may look at it, she always turns out to be a German.”Footnote 55 From such a perspective, Pavlova’s later emigration to Germany, where she permanently resided after 1858, looked like a “natural” outcome. Ivan Aksakov, a regular at Pavlova’s salon in the 1840s who visited her in Dresden in 1860, claimed in a letter to his mother and sisters that “in Karolina Karlovna there has never been a single Russian feature, she is a complete German (even a German cook), and now she has returned home for good, so well is she suited to Germany and Germany to her…. She is fully satisfied by the Germans and German life, feeling neither their pettiness nor their narrowness and small-mindedness.”Footnote 56 Aksakov accompanied this assessment with such a scathing denunciation of Pavlova’s personality that it borders on character assassination. He denies her any kind of depth, spirituality, or genuine human feelings, presumably because of her lack of a “Russian soul.”

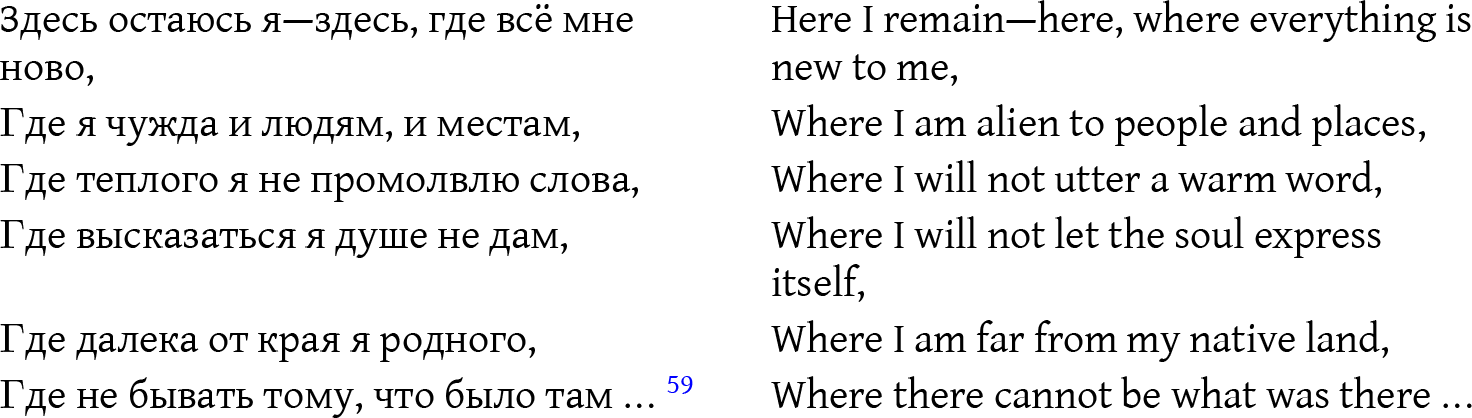

Aksakov was mistaken is his supposition that Pavlova’s move to Dresden should be seen as a homecoming, however. Rather, it was a flight from Russia, where she was treated as a pariah after the scandalous breakup of her marriage.Footnote 57 It is obvious that Pavlova regarded her life in Germany as a form of exile. In a letter from Dresden, also written in 1860, she referred to herself as “alone, helpless, in a foreign land.”Footnote 58 Similar feelings are expressed in her poem “Dresden,” written in the same year, where we find the stanza:

“Home,” for Pavlova, was Moscow, not Dresden. This situation did not change after decades of living in Germany in increasing destitution and obscurity. A year after her death, Pavlova’s grandson published an article in which he attempted to rescue his grandmother from oblivion and to rehabilitate her as a bona fide Russian by claiming that she never stopped loving her native land with “all the strength of her Russian soul.”Footnote 60

Can this alleged Russian patriotism be documented in Pavlova’s work? I propose to investigate this question by analyzing two relevant texts, one written in Russian during the 1850s in Estonia after the breakup of her marriage and the other one written in German towards the end of Pavlova’s long life. The most officially patriotic poem that Pavlova ever composed is the lengthy “Razgovor v Kremle” (Conversation in the Kremlin).Footnote 61 Published as a separate brochure in 1854 during the Crimean War, this poem of forty-three octaves features a conversation between an Englishman, a Frenchman, and a Russian. The two westerners, echoing Petr Chaadaev’s well-known thesis, argue that Russia, although an empire of considerable military strength, has contributed nothing to the civilized world. The Russian, while not directly challenging this opinion, presents Russian history as a centuries-old tale of suffering and martyrdom consumed by the struggle against foreign invaders.Footnote 62 The qualities he ascribes to the Russian people have a distinctly Slavophile tinge: he mentions the absence of class barriers in a harmonious family of co-religionists (edinovernoiu semˊei) where, to the astonishment of the foreign aristocrats, the “illustrious potentate joyously kisses a beggar on the lips” (radostno velˊmozha znatnyi/Tseluet nishchego v usta). In this society, tradition is handed down from generation to generation, or, as Pavlova puts it, “to the heart of the grandson remains sacred/what was sacred to the fathers” (Ostalosˊ sviato serdtsu vnuka/Chto bylo sviato dlia ottsov). Somewhat strangely in view of this Slavophilism, the speech of the Russian ends with a glorification of the arch-Europeanizer Peter the Great.

“Razgovor v Kremle” received a mixed reception. The reactionary critic Faddei Bulgarin and others of his ilk praised the poem for its patriotic spirit.Footnote 63 The liberal journal Sovremennik reacted more critically—not because of the poem’s content (about which the critic had nothing to say)—but because of its use of “exotic” rhymes. Pavlova found it necessary to defend herself in a letter to the editor Ivan Panaev, in which she not only defended her rhyming, but also her patriotic credentials.Footnote 64 She explains that she wrote the poem gripped by a “Russian feeling in a semi-foreign town” (Dorpat in Estonia, now Tartu), carried along by the wave of solidarity that had seized the nation at this time of war. To illustrate her point, she cites her lines “May Russia be exalted, and our names perish!” (Da vozvelichitsia Rossiia/I gibnut nashi imena!).Footnote 65 In his diary, the censor and literary historian Aleksandr Nikitenko took a dim view of this call for collective self-annihilation in the name of glorifying the Fatherland, calling it “hyperbolic and fake” (giperbola i falˊsh).Footnote 66 Pavlova’s slogan later took on a life of its own as a battle cry of Russian nationalists. Russian Communist Party leader Gennadii Ziuganov invoked it approvingly in a December 2023 statement of support for the war against Ukraine, referring to Pavlova as a “talented, but unfortunately forgotten poetess.”Footnote 67

It is questionable, though, whether the jingoistic call for self-immolation in the name of Russia’s glory really expressed Pavlova’s true opinion. She makes other statements in her letter to Panaev that are hard to take at face value. For example, she writes that the critique of her poem piqued most of all her feminine vanity, because a “woman poet is always more woman than poet” and that, as a woman, she “never wished and never strove to become an author.”Footnote 68 One wonders whether Pavlova is not engaging in a parodic mimicry of Panaev’s own misogyny here. By the same token, the declarative patriotism of “Razgovor v Kremle” was perhaps a performative and tactical move (in that respect, Nikitenko’s assessment of Pavlova’s words as “hyperbolic and fake” seems rather on the mark). The fact that Pavlova dedicated “Razgovor v Kremle” to her son, who was at that time fifteen years old, provides a clue about her motivation. After the breakup of her marriage with Nikolai Pavlov, she became emmeshed in an ugly custody battle over her only child. Pavlov did not hesitate to play the xenophobic card by accusing his wife of alienating their son from the Russian people and culture and trying to turn him into a German.Footnote 69 More generally, as Olga Hasty has noted, Pavlova found herself at that time “under attack for allegedly failing in her responsibilities as wife, daughter, mother, and loyal Russian subject.”Footnote 70 She may thus have found it necessary to prove her Russian bona fides with an ultra-patriotic poem. It is interesting to note that she chose not to include “Razgovor v Kremle” in the 1863 edition of her poetry (the only one to appear during her lifetime), which indicates that, at least by that time, she did not hold the poem in particularly high esteem.

A text that probably provides a more accurate testimony of Pavlova’s Russian “patriotism” (although thus far it has never been analyzed as such) is her German adaptation of Mikhail Lermontov’s poem “Rodina” (Homeland). Titled “Mein Vaterland” (My Fatherland), it appeared in the early 1890s in a German anthology of Russian poetry that came out shortly before the end of Pavlova’s life.Footnote 71 Significantly, Pavlova chose to articulate her feelings of Russian national belonging (or non-belonging) in the interstices of two languages. While echoing the musings of her fellow Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov, her German rewriting substantially alters the Russian source text.

Pavlova had been personally acquainted with Lermontov. The poet visited her Moscow salon in May 1840 before his departure for the Caucasus, leaving an autograph of his poem “Posredi nebesnykh tel” (Amidst Heavenly Bodies) in her album.Footnote 72 “Rodina,” written in early 1841, came out in the journal Otechestvennye zapiski in the same year. Pavlova’s translation reproduces and amplifies a typographical error in this publication, which misprinted “nochuiushchii oboz” (a wagon-train resting at night) as “kochuiushchii oboz” (a nomadic wagon-train). Pavlova seems to have taken a particular liking to this “nomadic” image, which she expands to “Die Karawanenzüge aus der Ferne/Der wandernden Nomadenhorden” (the trains of caravans from afar/of the migrating hordes of nomads).

Pavlova’s translation of “Rodina” has received low to mixed marks from the few scholars who took note of it. Barbara Lettmann-Sadony berated it in 1970 for “rolling out” (auswalzen) the twenty-six lines of the original text to a length of thirty-four and thereby “watering down” the poem with “superfluous insertions.”Footnote 73 The Russian scholar Olˊga Rodikova, in a 2012 PhD thesis, while also critiquing Pavlova’s formal deviations from the source text, came to a somewhat more positive conclusion, arguing that “overall Pavlova succeeded in preserving the national coloring of the original.”Footnote 74

In the context of Pavlova’s work as a translator, “Mein Vaterland” constitutes a strange anomaly. Usually, Pavlova prided herself on her “faithfulness.” Adding multiple lines of her own in translation is extremely unusual for her.Footnote 75 A closer look reveals that the supplemental lines are not randomly distributed over the entire text—they all occur at the beginning of the poem. This does not mean, though, that the rest of the translation is completely “faithful” either. “Rodina” ends with a drunken peasant revelry, which Lermontov connects to a holiday celebration. By contrast, Pavlova evokes a regular Sunday when the peasants strive “with merrymaking and noise to forget the week’s torment” (in Lust und Lärm der Woche Qual vergessen). This indication of the hard life of the Russian muzhik is added in Pavlova’s translation and not present in Lermontov’s original.

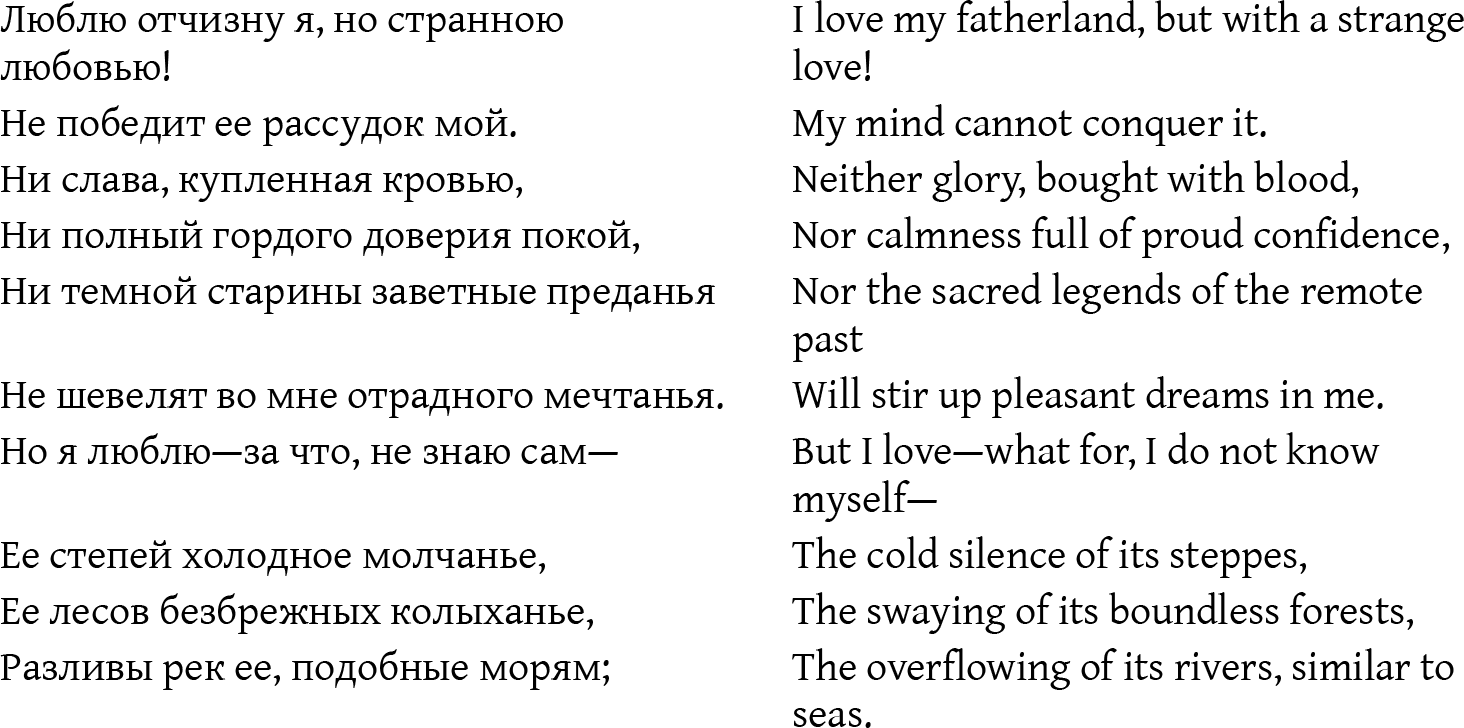

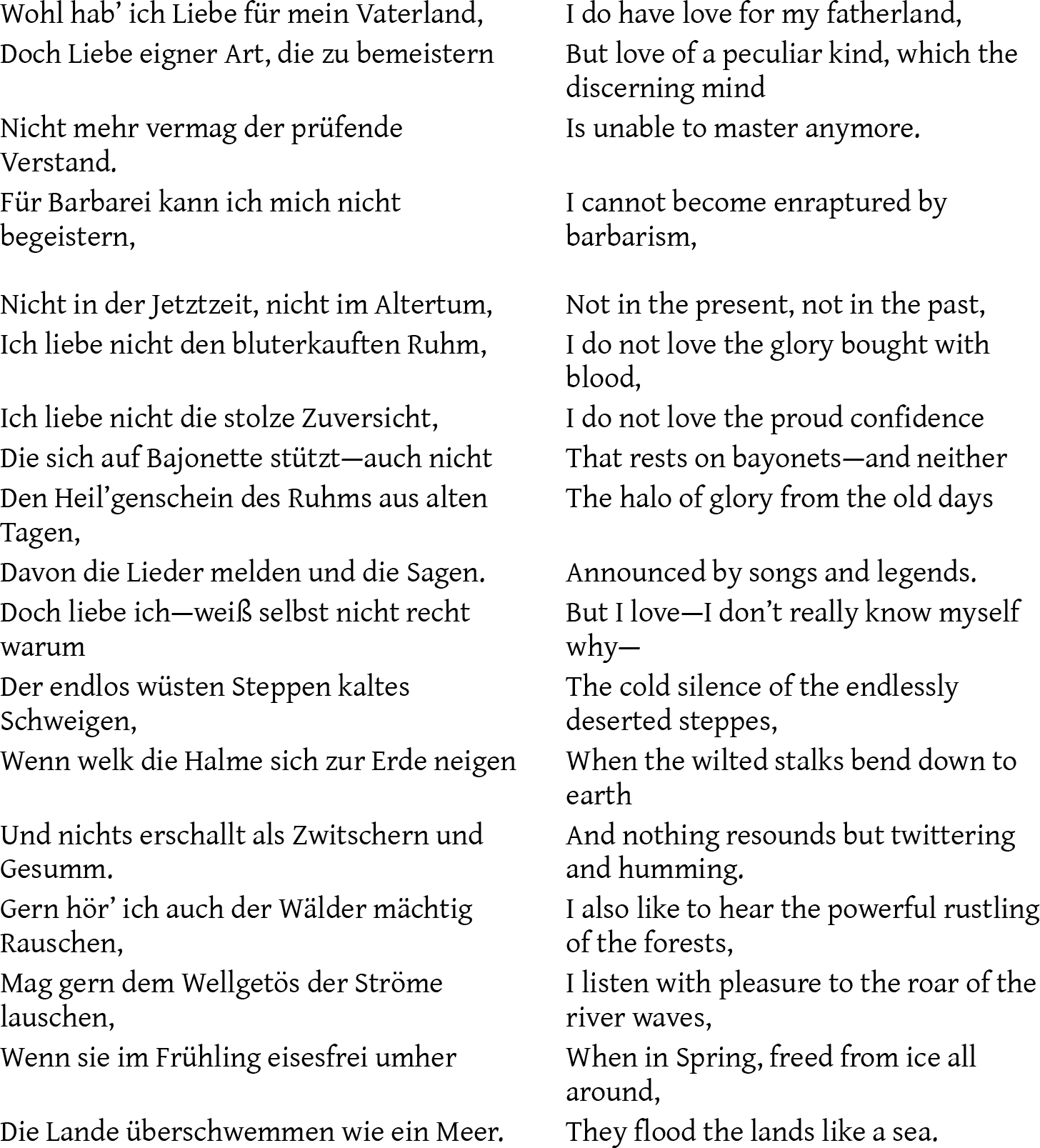

Pavlova’s most significant alterations of Lermontov’s poem occur within the first ten lines. “Rodina” begins as follows:

Pavlova’s translation expands Lermontov’s ten opening lines to eighteen:

What causes this expansion? One could argue, perhaps, that Pavlova found it necessary to provide the German reader with explanations that would be self-evident to a Russian, such as connecting the overflowing of the rivers with the melting of the ice in Spring. But this pedagogical impulse provides at best a partial motivation. Pavlova counters Lermontov’s silent steppe with an abundance of acoustic impressions. None of the twittering and humming, rustling and roaring evoked by Pavlova occurs in Lermontov’s original text. In fact, there are so many “invented” lines in Pavlova’s translation that one wonders whether her version was not perhaps based on an unknown variant of the poem. According to the Russian scholar Rostislav Danilevskii, Lermontov may have left some of his unpublished manuscripts with Pavlova.Footnote 76 However, it is unlikely that “Rodina” was among them, since Lermontov wrote the poem after he saw Pavlova in Moscow. Moreover, as we have seen, Pavlova’s translation reproduces the typo in the poem’s first publication, which suggests that she used the version published in Otechestvennye zapiski as her source.

We are left with the conclusion, then, that Pavlova’s willful alterations were prompted by a desire to make Lermontov’s poem her own. This impulse is already reflected in the title “Mein Vaterland,” which adds the possessive pronoun “my.” The choice of Vaterland rather than the feminine Heimat, which would have been the more obvious German equivalent of rodina, indicates Pavlova’s focus on Russia’s patriarchal and oppressive features. One wonders whether, aside from the fact that Pavlova’s personal view of Russian nature included not only its visual qualities but also its soundscape, the image of the river breaking free from ice, which is absent from Lermontov’s original text, could not be read as a political metaphor.

This brings us to Pavlova’s rendition of the first stanza. Both Lermontov and Pavlova provide in these lines a qualified statement of their “strange” love for Russia. They make clear that it does not include any admiration for Russian military conquests, the strength of the Russian state, or tales of Russia’s heroic past. In her amplification of the original text, Pavlova makes Lermontov’s rejection of official Russian state patriotism more explicit and forceful. In doing so, she also repudiates the Slavophilism and wartime sloganeering of her own “Razgovor v Kremle.” The expression “not anymore” in the third line indicates a change in her attitude toward her homeland. Lermontov’s “Rodina” itself has been interpreted as a repudiation of Slavophile views.Footnote 77 However, Russian critics, when discussing the poem, tend to stress its positive patriotic content.Footnote 78 Not much of this alleged optimism survives in Pavlova’s rewriting. What we are left with, at the end, is the “barbarism” of a regime relying on military conquests and jingoistic tales of past glory, the wild beauty and soundscape of Russian nature, and a downtrodden rural population drowning in drunken oblivion.

In a multiethnic and multilingual empire like Russia, whose elite had become Francophone through an act of self-colonization, Pavlova’s command of multiple languages was not in itself unusual. What made her unique was her ability to compose poetry in three languages, especially in an age that, under the influence of German romanticism, had begun to link poetic expression with the manifestation of the national soul.Footnote 79 There is little evidence that Pavlova was concerned about the link between language and collective identity. Did she define herself as a Russian, or did her mixed origin and native command of multiple languages turn her into a transnational cosmopolitan? The problem lies in the binary nature of such a choice, which presupposes that one can only be one or the other. In reality, the matter allows of course for significant fluidity, with the choice of a given identity dependent on situational or strategic considerations. Barbara Lettmann-Sadony makes the interesting observation that Pavlova tended to present herself as a Russian in her German and French writings and as a German in her Russian writings to elicit admiration for her ability to write in a “foreign” tongue.Footnote 80 The trick seems to have worked—the memoirist Elena Shtakenshneider wrote in 1856 about Pavlova’s Russian poems: “The most remarkable thing about her is that she is not Russian at all and only learned Russian very recently (!), and yet she has an excellent mastery of the Russian language and Russian verse.”Footnote 81 While having its benefits, this assumed foreignness also carried risks, as we saw with the dismissive treatment that Pavlova received from her Slavophile contemporaries.

When talking about Pavlova’s national identity and place in the canon, we need to disassociate ethnicity, place of belonging, and language. While her ethnic self-identification was fluid and situational, there can be no doubt that her geographic sense of belonging was rooted in her Russian homeland, even though she was hardly a supporter of tsarist autocracy or a Slavophile, and, in later years, came to reject outright the imperialist Russian state and Russian militarism, as we saw in her German translation of Lermontov. Linguistically, Pavlova was at home in multiple languages (including the language of a country, France, that she hardly ever visited).Footnote 82 Although she ended up living in Germany for the final decades of her life, this country never became Pavlova’s home either. She was, however, completely at home in the German language. This paradox illustrates the tenuousness of the modern concept of the nation state as a unified amalgam of territory, ethnicity, and language. Pavlova simply does not fit into such a paradigm.

Unlike later twentieth-century Russian émigré authors like Vladimir Nabokov or Marina Tsvetaeva, who were also trilingual since childhood, Pavlova did not even have a distinguishable “L1,” “L2” and “L3.”Footnote 83 In that respect, she resembles the literary scholar and polymath George Steiner, who reported having “no recollection whatever of a first language,” for he always possessed “equal currency in English, French, and German.”Footnote 84 Writing poetry in multiple languages is something that seems to have been completely natural for Pavlova. Rather unusually for a translingual writer, she did not engage much in linguistic self-reflection, let alone in handwringing over the unbridgeable gap between languages. Nabokov’s lament of having been forced to abandon his “untrammeled, rich, and infinitely docile Russian tongue for a second-rate brand of English” would have made little sense to Pavlova.Footnote 85 Her seemingly effortless linguistic border crossings went against the grain of the nineteenth-century romantic zeitgeist of nationalist consolidation, but they anticipate more recent tendencies to question the nativist privileging of Vaterland and Muttersprache. Pavlova was ahead of her time not only as a woman poet in a man’s world, but also as a linguistic shapeshifter in a century that championed patriotic monolingualism.

Adrian Wanner, born and raised in Switzerland, is Distinguished Professor of Slavic Languages and Comparative Literature at Pennsylvania State University. His research interests include literary relations between Russia and the west, modernist poetry, translingual fiction, and (self-)translation studies. His most recent monograph is The Bilingual Muse: Self-Translation among Russian Poets (2020). In addition to four scholarly monographs, he has published seven editions of Russian, Romanian, and Ukrainian poetry of his own translations into German verse.