Political parties played a crucial role in the emergence of democracy in South America. Democracy arose first in those South American countries that developed strong parties because such parties placed democratic reform on the agenda and provided the legislative votes required to enact the reforms. Strong parties also had the organizations necessary to monitor and enforce the implementation of the reforms.

This chapter describes the evolution of parties in South America during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and analyzes what led to the development of strong parties in some countries but not in others. Political parties first emerged in South America during the nineteenth century, and by the end of the century, these parties had established permanent national organizations and enduring linkages to the electorate in some countries, such as Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay. In other countries, however, party organizations and identities would not consolidate until the twentieth century.

The theoretical literature on parties, which has predominantly focused on Europe and the United States, offers several potential explanations for the emergence of strong parties. Some studies have ascribed the rise of political parties to economic development or to the spread of elections and democracy. Other analyses have attributed the emergence of strong parties to violent struggles or to class and ethnic cleavages. Although most of these factors contributed to the rise of parties in South America, none of them can adequately explain the variance in party development in the region before 1930.

This chapter argues that two main factors shaped party development in South America during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. First, strong parties arose from intense but balanced religious and territorial cleavages. In nineteenth-century Latin America, religious and territorial cleavages often generated fierce passions, and strong parties tended to emerge where both sides of the cleavage were powerful – that is, where each side had numerous proponents and ample resources that they could devote to party building. More specifically, strong parties tended to arise where there were numerous conservative supporters of the Catholic Church as well as numerous liberal critics of the Church, and where both sides enjoyed considerable resources. Alternatively, strong parties might emerge where the capital city and the provinces had roughly similar economic, demographic, political, and military resources. Under these circumstances, neither side could easily dominate the other. Instead, they often fought to a standstill, deepening partisan identities and loyalties. By contrast, where one side of the cleavage was considerably stronger than the other, competition for power tended to take place within a cleavage rather than between different sides of the cleavage. Where this was the case, political competition often revolved around personalities, rather than ideologies or interests, and the parties that emerged typically had weak organizations and ephemeral loyalties.

Second, strong national parties were more likely to arise in countries with few geographic barriers where the bulk of the population lived in relative proximity to each other. Given the lack of communications and transportation infrastructure during the nineteenth century, it was much harder to build national parties in geographically fragmented nations where the population was widely dispersed. In the latter countries, politicians and party leaders could not easily travel to or even communicate with much of the population, which made it difficult to campaign, manage organizations, and build support throughout the nation. Geographically fragmented countries also tended to have strong regional identities, which impeded the construction of national institutions such as parties.

To be sure, these two factors were not the only variables that influenced party development before 1930. Nevertheless, they were the most important ones. It was very difficult for strong parties to emerge in the nineteenth and early twentieth century without at least one of these factors being present, and the presence of both variables significantly increased the likelihood that strong parties would arise. It is also true that religious and center–periphery cleavages overlapped to a degree in the nineteenth century since liberals tended to be stronger in urban areas and conservatives were typically stronger in rural areas.Footnote 1 And geographic fragmentation tended to increase the number of territorial cleavages and decrease the likelihood that the center–periphery cleavage was balanced. Nevertheless, the correlation between these variables should not be exaggerated. Geographic concentration was no guarantee that the center–periphery cleavage would be balanced, and conservatives as well as liberals were often strong in both urban and rural areas.

The organization of the chapter is as follows. The first section describes how I measure party strength and examines the variation in party development across South America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century using data from the V-Dem project as well as the secondary literature. The second section discusses existing theories of party development and assesses to what extent they can explain differences in parties within the region during this period. The third section examines how religious and territorial cleavages shaped the prospects for party building in South America during the nineteenth century, and the fourth section discusses the role played by geographical fragmentation. The concluding section summarizes the main findings of the chapter.

Party Strength in South America before 1930

In the broadest sense of the term, a political party is “any group, however loosely organized, seeking to elect government officeholders under a given label,” but parties vary considerably in terms of their strength and organization (Epstein Reference Epstein1980, 9).Footnote 2 Conceptualizing and measuring party strength in Latin America before 1930 is difficult because of the incipient nature of parties during this period and the paucity of data available. By current standards, none of the parties operating in Latin America during the nineteenth or early twentieth century would rank as strong because they lacked the extensive bureaucracies, mass memberships, and developed territorial organizations that characterize strong parties today. Nevertheless, as we shall see, there were important differences in party strength across Latin American countries during this period.

I define parties as strong when they have two main characteristics. First, they must have broad and lasting attachments to the electorate. Strong parties should be able to repeatedly gain the support of large swaths of the electorate, even if the electorate represents a relatively small segment of the total population, as it typically did in nineteenth-century Latin America. Second, strong parties must possess enduring national organizations with platforms, rules, and numerous branches or affiliated associations. A strong party will have a permanent organization, rather than one that only exists during election periods, and it will have a presence in various parts of the country, rather than in a single municipality, state, or province. This bipartite definition captures the important differences that existed between the parties of this era, while focusing on characteristics for which there are data.Footnote 3

Political parties first emerged in Latin America in the middle of the nineteenth century, but it was not until the late nineteenth century that some of them developed relatively strong and permanent organizations.Footnote 4 In the mid-nineteenth century, politicians and political brokers created electoral clubs or societies that promoted candidates and helped turn out the vote for them (Sabato Reference Sabato2018, 62–63). Politicians initially resisted calling these electoral organizations “parties” because the term had negative connotations. The early parties or electoral clubs tended to be ephemeral and personalistic organizations that functioned only during electoral periods. Nevertheless, some of them gradually developed loyal partisans and permanent organizational structures that reached much of the nation (Drake Reference Drake2009, 122). According to Sabato (Reference Sabato2018, 64), by the last quarter of the nineteenth century, some parties “developed into tightly organized institutions, with prescribed rules and mechanisms to join in, choose authorities, draft platforms and programs, select and put forward candidates for elective office, define and enforce party discipline, and so forth.” Even at the end of the nineteenth century, however, most parties in the region remained weak, personalistic, and underinstitutionalized.

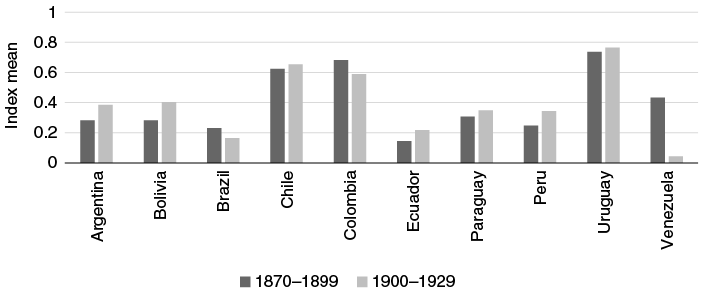

Systematic data on party strength is scarce for the nineteenth and early twentieth century. There are no sweeping cross-national analyses of parties in Latin America during this period. Fortunately, the V-Dem project does have data on several party-related variables, which are coded by country experts. V-Dem’s party institutionalization index (v2xps_party) adds the indicators for various party-related variables, including party organization (v2psorgs), party branches (v2psprbrch), party linkages (v2psprlnks), distinct party platforms (v2psplats), and legislative party cohesion (v2pscohesv), and then converts the sum to a cumulative dimension function (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2024a, 320). According to V-Dem, the regional average of party institutionalization increased relatively steadily over the course of the nineteenth century, reaching a high in the 1890s, before declining slightly in the early twentieth century. As Figure 4.1 shows, Uruguay, Chile, and Colombia stood out as having the most institutionalized parties in the region, both in the late nineteenth century as well as in the first three decades of the twentieth century. Paraguay ranked fifth and Argentina sixth, behind Venezuela, on this index between 1870 and 1899, whereas Argentina ranked fifth and Paraguay sixth, just after Bolivia, between 1900 and 1929, according to V-Dem.

Figure 4.1 Party institutionalization in South America, 1870–1929

Note: The y-axis shows the means of V-Dem’s party institutionalization index.

The historical literature on parties in these countries, which is discussed in detail in Chapters 5–8, provides relatively similar evaluations of cross-national variation in party strength during this period. As this literature shows, the first South American countries to develop robust and enduring parties were Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay (Drake Reference Drake2009, 122–124, 159–161; Fitzgibbon Reference Fitzgibbon1957, 10–11). Parties were founded in these countries in the middle of the nineteenth century and, in the decades that followed, they evolved into national institutions with broad networks of branches or affiliated organizations. In all three countries, parties developed strong and enduring ties to the electorate: Many people came to identify with parties and passed on their party loyalties over generations.

As Chapter 5 shows, in Chile four major parties – the Liberal Party, the Conservative Party, the National Party, and the Radical Party – arose and developed widespread and lasting partisan loyalties during the nineteenth century. Two of these parties – the Conservative Party and the Radical Party – also established relatively strong national organizations (Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela and Posada-Carbó1996, 249; Reference Valenzuela and Ivereigh2000; Guilisasti Tagle Reference Guilisasti Tagle1964, 22–23; Heise Reference Heise González1982, 317–318, 327; Remmer Reference Remmer1984, 15; Snow Reference Snow1963). Although the Liberal Party and the National Party had weaker organizations and suffered from frequent splits and defections, all four parties proved enduring, dominating Chilean politics throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century (Urzúa Valenzuela Reference Urzúa Valenzuela1968, 32; Scully Reference Scully1992, 49; Heise Reference Heise González1982, 291).

In Uruguay only two strong parties, the National or Blanco Party and the Colorado Party, arose during the nineteenth century, as Chapter 5 discusses. Both parties gradually built up deep partisan loyalties and powerful national organizations with branches and affiliated organizations throughout the country (Corbo Reference Corbo2016, 104–106; Hierro López Reference Hierro López2015, 168; Fernández and Machín Reference Fernández and Machín2017, 144). The Blancos and Colorados occasionally split and periodic efforts were made to unite the two parties or establish third parties, but none of these attempts prospered for long (McLaughlin Reference McLaughlin1973, 277; López-Alves Reference López-Alves2000, 57). People overwhelmingly stuck with the party of their parents, and the two parties dominated the political system throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Colombia also developed a strong two-party system during the nineteenth century, as Chapter 6 discusses. The Conservative and Liberal parties first arose in Colombia during the 1840s and gradually created relatively complex and centralized organizations (Bushnell Reference Bushnell1993, 65; Delpar Reference Delpar1981, 3–4; Safford and Palacios Reference Safford and Palacios2002, 134–143). Both parties established numerous branches and affiliated organizations, including newspapers, schools, elite clubs, and mass societies such as associations of artisans (Sowell Reference Sowell1992; Sanders Reference Sanders2004, 66–69; Posada-Carbó Reference Posada-Carbó2010). By the end of the nineteenth century, the Conservatives and Liberals had achieved an organizational presence nationwide (Delpar Reference Delpar1981, 126–127, 177, 183). Although the two parties underwent frequent splits, which sometimes resulted in the formation of third parties, these splits proved temporary. Both parties proved extraordinarily durable, and much of the population established close ties to the parties, which were passed down from generation to generation.

By contrast, strong parties did not emerge in Argentina and Paraguay until the early twentieth century, and even then, the parties remained weaker than in Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay. According to López (Reference López and López2001b, 58), for most of the nineteenth century, Argentine parties “were extremely weak, both because they consisted of local groups without practically any national articulation, and because they completely lacked organization.” As Chapter 6 discusses, the first important party in Argentina, the UCR, developed a strong organization and partisan ties in the city and province of Buenos Aires in the 1890s, but it did not have much of a presence in most other parts of the country until the early twentieth century (Alonso Reference Alonso2000, 162; Rock Reference Rock2002, 144). Moreover, the UCR was the only strong party to emerge in the country during this period. It dominated Argentine politics between 1916 and 1930.

As Chapter 8 details, two important parties, the Colorado Party and the Liberal Party, were established in Paraguay in 1887, but they did not develop into strong parties until the early twentieth century. The Colorado Party initially dominated the government, but the Liberal Party seized power in a revolt in 1904 and maintained control until the military overthrew it in a 1936 coup. The two parties did not develop strong organizations during this period, but they did establish enduring loyalties in the population, attracting both urban and rural supporters (Lewis Reference Lewis1993, 124; Caballero Aquino and Livieres Banks Reference Caballero Aquino and Banks1993, 50). Family members typically belonged to the same party and passed down their partisan attachments to their children (Nichols Reference Nichols1970, 47–48).

Parties in the other South American countries lacked strong organizations and enduring support during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. As Chapter 8 discusses, Bolivian parties were largely personalistic vehicles during this period without organizational structures or committed followers (Dunkerley Reference Dunkerley2003, 62; Klein Reference Klein1969b, 24–25; Irurozqui Reference Irurozqui2000, 399–400). In 1908, Manuel Rigoberto Paredes wrote that: “In Bolivia what we call parties are only factions, bands or tendencies of a markedly personal character” (cited in Dunkerley Reference Dunkerley2003, 136). Several parties emerged in Bolivia during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, including the Conservative Party, the Liberal Party, the Republican Party, the Socialist Republican Party, and the Nationalist Party, but only the Liberal Party survived the downfall of its founding leader. And even the Liberal Party remained on the margins of power after 1920.

Ecuador also failed to develop strong parties during the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, as Chapter 8 discusses. Several parties, including the Conservative Party, the Progressive Party, and the Liberal Party, were founded in the late nineteenth century and took turns governing, but none of them developed meaningful organizations during this period. According to Rodríguez (Reference Rodríguez1985, 45), nineteenth-century “political parties were only loose collections of small groups that owed primary loyalty to an individual or region.” The Conservative and the Liberal parties made some organizational investments beginning in the 1920s and gradually gained mass followings, which enabled them to endure into the twenty-first century, but their level of party development in the early twentieth century remained quite low (Ayala Mora Reference Ayala Mora1989, 23–25; Fitch Reference Fitch1977, 18).

As Chapter 7 details, strong parties did not emerge in Peru either. The most important Peruvian party of the period, the Civil Party, first arose in the 1870s and built a network of regional alliances and a relatively disciplined contingent in the legislature, but it never developed a strong national organization (Mücke Reference Mücke2004; McEvoy Reference McEvoy1994). Throughout most of its existence, it lacked a formal membership, a clear platform, bureaucratic rules, or any permanent structures aside from an executive committee (Mücke Reference Mücke2004, 200–201). The other political parties that arose in Peru during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, such as the Constitutional Party, the Democrat Party, and the Liberal Party, were mere personalistic vehicles, lacking organizations, firm ideologies, and internal discipline, not to mention a broad membership and an experienced second generation of leaders (Pike Reference Pike1969, 218; Klarén Reference Klarén2000, 214). One prominent politician of that time observed that “the total membership of any given political party in Peru could easily fit into one railroad coach” (cited in Stein Reference Stein1980, 25). The organizational weakness of these parties made it relatively easy for Augusto Leguía, the Peruvian dictator, to co-opt, repress, and dismantle them after he came to power in 1919 (Pike Reference Pike1969, 218; Stein Reference Stein1980, 38). Leguía founded his own party, the Democratic Reformist Party (PDR), in 1920, but he stacked it with friends and family members who would blindly support him (Pike Reference Pike1969, 218; Stein Reference Stein1980, 47–48). The PDR, like the other personalistic parties, did not survive for long the death of its founding leader.

Strong parties also failed to arise in Brazil during the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, as Chapter 7 discusses. Two parties, the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party, emerged during the 1830s and alternated in power until 1889, except for a brief period between 1853 and 1868 when they jointly governed in a temporary alliance. Neither of these parties developed strong organizational structures or enduring partisan loyalties, however. They depended instead on local political bosses (coroneis) to turn out the votes in exchange for patronage (Barman Reference Barman1988, 226; Graham Reference Graham1990, 156–159). Factionalism was pervasive in both parties, and partisan loyalty was sorely lacking. According to Graham (Reference Graham1990, 181): “Party labels were put on and taken off almost as easily as a set of clothes.” The Liberal and Conservative parties dissolved after the fall of the empire in 1889, but no strong national parties emerged to replace them. A few regional parties governed the country during the First Republic (1889–1930): The Paulista Republican Party captured the presidency six times during this period, whereas the Mineiro Republican Party won it three times (Fausto Reference Fausto and Bethell1989, 272). Although some Republican parties had strong state organizations that routinely captured a large share of the state vote, they failed to build national organizations (Love Reference Love1970, 13; 1980; Wirth Reference Wirth1977). As a result, Brazil continued to suffer from party weakness.

As Chapter 7 details, Venezuelan parties were also underdeveloped in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, leading the Venezuelan novelist and politician Rómulo Gallegos to write in 1909 that political parties “have not yet existed in Venezuela” (cited in Rey Reference Rey2015, 65). The Conservative Party and the Liberal Party emerged shortly after independence, but these parties were little more than loose collections of notables that lacked permanent structures and centered power in their paramount leaders (Gilmore Reference Gilmore1964, 25, 27, 56; Pérez Reference Pérez1996, 49). Both parties split frequently along personalistic lines, and neither party established strong roots in Venezuelan society even though much of the population was eligible to vote. The Conservative Party fell apart after the 1859–1863 Federal War, although Conservative candidates still participated in elections in the years that followed (Pérez Reference Pérez1996, 61; Tarver and Frederick Reference Tarver and Frederick2005, 68). The Liberal Party, meanwhile, was repressed under the dictatorships of Cipriano Castro and Juan Vicente Gómez. Although Gómez initially brought some Liberals into his regime, he quickly turned against the party’s leaders and other traditional politicians, excluding them from his cabinet and exiling, imprisoning, and even killing those who dared oppose him (McBeth Reference McBeth2008, 24–27, 30–31, 63, 318). Gómez and his advisers believed that there was no need for political parties and he sought to “unite Venezuelans without distinction of parties” (McBeth Reference McBeth2008, 372; Rey Reference Rey2015, 63–64). Venezuelan parties were too weak to survive in this environment.

Table 4.1 presents some basic data on the main parties in South America between 1870 and 1930. I code parties as having a high level of party strength if they had a strong organization and widespread support during at least half of the years of this period. If they only had one or the other (i.e., a strong organization or widespread support), then they are coded as being of medium strength, and if they had neither, then they are coded as being of low strength. These codings are based on a thorough review of the historical literature on parties in these countries, much of which is cited in Chapters 5–8.

Table 4.1 Major political parties in South America, 1870–1930

As Table 4.1 indicates, Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay clearly had the strongest parties in the region during this period, followed by Argentina and Paraguay. The strongest parties in Argentina (the UCR), Chile (the Conservative Party, the Liberal Party, and the Radical Party), Colombia (the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party), Paraguay (the Colorado Party and the Liberal Party), and Uruguay (the Blanco Party and the Colorado Party) continued to flourished long after the transition to democracy in these countries, racking up large shares of the vote. This suggests that they had robust organizations and/or strong roots in the electorate. By contrast, parties in the other South American countries, with the exception of Ecuador, were much shorter lived, typically dissolving even before these countries democratized

Existing Explanations for Party Strength

What explains the variation in party strength in South America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century? The existing theoretical literature identifies several potential explanations for the emergence of strong parties in any context, including democratization, socioeconomic modernization, and violent conflict. Although these factors all played a role in the development of parties in the region, none of them can provide a convincing explanation for the variance in party strength during this period.

One strand in the literature suggests that parties were a natural outgrowth of democratization. According to Duverger (Reference Duverger1972, xxiii), “the development of parties seems bound up with that of democracy, that is to say with the extension of popular suffrage and parliamentary prerogatives.”Footnote 5 Similarly, LaPalombara and Weiner (Reference LaPalombara, Weiner, LaPalombara and Weiner1966, 8) note that “it is customary in the West to associate the development of parties with the rise of parliaments and with the gradual extension of the suffrage.” They and others have argued that once the right to vote was extended to a large share of the population, it became necessary to organize parties in order to publicize the candidates’ platforms and mobilize citizens to vote (Boix Reference Boix, Boix and Stokes2007, 500; Aldrich Reference Aldrich1995; Epstein Reference Epstein1980, 19–20; Duverger Reference Duverger1972, xxiv). They also suggest that as legislatures became increasingly autonomous and important, like-minded representatives saw a need to coordinate their activities. In addition, a large literature has shown that partisan attachments develop over time through repeated participation in elections (Lupu and Stokes Reference Lupu and Stokes2010; Converse Reference Converse1969; Dinas Reference Dinas2014).Footnote 6 From this perspective, parties did not produce democracy, but rather democracy created parties. Conversely, repressive authoritarian regimes impeded the emergence of strong parties.

Certainly, the existence of elections, legislatures, and a degree of civil and political liberties were crucial to the emergence and growth of parties in South America. Parties could not arise or survive for long in exclusionary dictatorships where the rulers harshly repressed the opposition, as in Paraguay before 1870. Nevertheless, democratic institutions cannot explain the considerable variance in the strength of parties within the region since, as Chapter 2 discussed, all South American countries had elections and legislatures and a degree of civil and political liberties for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Nor can the expansion of the suffrage or other democratizing measures readily explain the emergence of strong parties. Robust parties emerged during the nineteenth century in some South American countries, such as Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay, before these countries expanded the suffrage or took important steps toward democracy.Footnote 7 Moreover, in most countries, parties emerged not just to compete in elections and coordinate legislative activities but also to engage in armed struggles for power. Thus, democratic institutions provide at best a partial explanation for the rise of strong parties in the region.

Another explanation for the emergence of parties in Latin America might attribute it to socioeconomic modernization. Modernization theorists have long argued that socioeconomic development contributes to the growth of intermediary associations, including parties. Lipset (Reference Lipset1983, 52), for example, maintains that “the propensity to form such groups seems to be a function of level of income and opportunities for leisure within given nations.” LaPalombara and Weiner (Reference LaPalombara, Weiner, LaPalombara and Weiner1966, 21) go so far as to say that “parties will not in fact materialize unless a measure of modernization has already occurred.” They argue that the spread of mass education, urbanization, and the development of communication and transportation networks all facilitate the rise of parties by making political organization easier (LaPalombara and Weiner Reference LaPalombara, Weiner, LaPalombara and Weiner1966, 19–21). They also suggest that economic development contributes to the growth of the state and that, as the state grows in importance, individuals will form parties to try to gain control of it.

Socioeconomic modernization certainly did foster the development of parties in South America. As we shall see, urbanization, increases in literacy, and the expansion of the media and transportation networks helped strengthen parties by making it easier for party organizers to communicate with and mobilize supporters nationwide. Nevertheless, socioeconomic development cannot readily explain why strong parties emerged in some countries and not others. Although some countries that developed strong parties, such as Chile and Uruguay, were among the wealthier countries in the region in the nineteenth century, others, such as Colombia and Paraguay, were not. Moreover, as noted earlier, Argentina, the wealthiest Latin American country at that time, lagged behind Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay in the development of parties. Thus, although socioeconomic modernization played a role in the emergence of strong parties in the region, it was clearly not a determining factor.

A third approach to understanding the emergence of strong parties focuses on violent conflict. As various scholars have argued, conflict and repression can contribute to party building by mobilizing activists, generating intense partisan attachments, and encouraging an “us versus them” mentality (LeBas Reference LeBas2011; Levitsky, Loxton, and Van Dyck Reference Levitsky, Loxton, Van Dyck, Levitsky, Loxton, Van Dyck and Domínguez2016, 14–21; Wood Reference Wood2003). People who participate in violent struggles not only bear intense antipathies toward the side that they fight, they also frequently develop strong bonds with the people on their own side. Where the conflicts involve the loss of lives, family members of the deceased will frequently come to share these intense attachments and antipathies even though they may not have participated directly in the conflicts themselves. These intense feelings, moreover, are often passed down over generations, thereby leading to the endurance of partisan loyalties over time.

Clearly, interparty civil wars during the nineteenth century played an important role in generating strong partisan ties in some South American countries, such as Colombia and Uruguay (López-Alves Reference López-Alves2000; Zeitlin Reference Zeitlin1984; Somma Reference Somma2011). Where opposition parties engaged in repeated uprisings that were violently repressed, they gradually developed committed local leaders and strong partisan ties to the population. Moreover, in an era of suffrage restrictions and limited voter turnout, civil wars often engaged more people than elections did, which enabled parties to become mass vehicles (Safford Reference Safford, Graham and Smith1974, 74). Nevertheless, violent conflict cannot readily explain the variance in party strength since interparty wars were common throughout the region. Indeed, as Chapters 7 and 8 discuss, some countries that did not develop strong parties during the nineteenth century, such as Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela, suffered as much internal political violence as the countries that did have strong parties. In addition, Chile developed strong parties in the late nineteenth century even though it suffered less violent conflict during this period than most South American countries.

As we shall see, religious and territorial cleavages and the degree of geographic fragmentation provide a more compelling explanation for variation in party strength in the region than do democratization, development, or violent conflict. Strong parties tended to arise in countries with intense yet balanced religious or territorial cleavages and low levels of geographic fragmentation.

Social Cleavages and Parties

Scholars have long argued that social cleavages, including class, ethnic, religious, and territorial divisions, have driven party formation in Europe and elsewhere (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967; Caramani Reference Caramani2004; Bartolini and Mair Reference Bartolini and Mair1990; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1970). In South America, however, class and ethnic cleavages played virtually no role in the initial emergence of parties in the region, in part because they divided the population into haves and have nots. By contrast, religious and territorial cleavages generated numerous parties in the region during the nineteenth century, in part because wealthy and powerful people and institutions tended to be located on both sides of these cleavages and they could use their resources for party building. Religious and territorial cleavages only led to the emergence of strong parties, however, where they divided the population into two similarly powerful groups, which prevented one side from dominating the other and fostered long-term competition for power.

Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967, 14) contend that the process of building nation-states created two central cleavages in Europe: the division between the center and periphery (or what they call the dominant culture and the subject cultures); and the conflict between secular forces and the Church. The Industrial Revolution, meanwhile, produced two other important cleavages: the divide between industry and agriculture; and the class cleavage, which pitted employers against workers. In Europe, parties arose to represent people on both sides of these cleavages: workers as well as employers; rural as well as urban interests; conservative Catholics as well as anti-clerical liberals; and ethnolinguistic minorities as well as majorities. Moreover, the party systems that emerged often froze in place – that is, the parties that had arisen from the cleavages continued to dominate even after the cleavages waned in importance (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967).Footnote 8

In any society, however, there are numerous cleavages that never become politicized or reflected in the partisan arena and, even if they do, they often fail to translate into strong parties. Cleavages are more likely to give birth to strong parties if they embody issues central to the identity of much of the population or involve strongly held beliefs or important interests. Cleavages that divide the population into large groups that have an important presence throughout a nation’s territory are also more likely to produce strong national parties than cleavages that only hive off very small segments of the population or are relevant in only a few areas of a country. As Caramani (Reference Caramani2004) has shown, the class cleavage and the church–state cleavage played an important role in nationalizing European party systems because these cleavages were relevant throughout much of the territory of most European countries.

The mere existence of social cleavages, even profound ones that resonate throughout a country’s territory, does not guarantee the emergence of parties based on these cleavages, however. Parties do not spring naturally from cleavages; they must be created by individuals or organizations. The most successful and enduring parties are typically established by political entrepreneurs with ample networks and resources. In many instances, societal organizations have played a key role in forming and supporting parties that represented a particular cleavage. Unions, for example, helped create many socialist parties in Europe and provided them with activists, leaders, and supporters as well as financing (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2000). Similarly, priests and various associations and individuals affiliated with the Catholic Church provided the base for conservative parties during the nineteenth century and Christian democratic parties in the twentieth century (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas1996; Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring, Scully, Mainwaring and Scully2003).

Neither ethnic cleavages nor class cleavages produced important political parties in Latin America during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, in large part because members of subordinate classes and ethnic groups lacked the political networks and organizational and financial resources necessary to create parties. Latin American countries had significant ethnic diversity during the nineteenth century, with large populations of indigenous people and Afro-Latinos, but only the European-origin population had the networks and resources to create political parties. Moreover, in many countries, most indigenous and Afro-Latino people were not even eligible to vote during the nineteenth and early twentieth century because they were poor, illiterate, or in relations of dependency.

The development of class-based parties in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century was also stymied by voting restrictions and the unequal distribution of financial and organizational resources. The rural peasantry represented a huge share of the population during this period, but in many countries the majority of peasants could not vote because of income and literacy restrictions. Moreover, peasants were often in the thrall of landowners and lacked the resources to form parties. Voting restrictions and a dearth of financial and organizational resources similarly obstructed party formation among the urban working classes, which were still relatively small during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Industrialization came much later in Latin America than in Europe and the United States. Labor unions first emerged in Latin America during the late nineteenth century, but these unions initially had tiny memberships and little influence. In addition, many unions had anarcho-syndicalist tendencies during this period and eschewed involvement in political parties and electoral politics. In some countries, leaders founded socialist parties or other parties that sought to represent the workers, but only in Argentina did a socialist party gain a significant following by the early twentieth century, and even there, its support remained confined mostly to the capital (Walter Reference Walter1977).

The middle classes had greater financial and educational resources and participated in many of the important political parties that emerged during this period. Some major parties of this era, such as the Radical parties of Argentina and Chile, gradually embraced the interests of the middle classes and became middle-class dominated, but this did not typically occur until well into the twentieth century. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Latin American middle classes were still relatively small, and they did not have significant class consciousness, which impeded the development of parties based in the middle classes.

During the nineteenth century, many parties sprang from territorial cleavages in South America, but in most cases these parties did not develop into strong parties. The first parties in South America typically arose in cities because they had the densest concentration of elites, organizations, and resources, and spatial proximity made it easier for parties to organize and mobilize voters. Capital cities, in particular, fostered parties because of the size and density of their populations and their proximity to the government. These parties, however, generally represented urban interests, which made it difficult for them to win support in rural areas. In addition, as we shall see, geographical barriers impeded travel and communication, making it difficult for urban-based parties to extend their reach into the provinces. Provincial parties faced even more daunting obstacles to party building, given the difficulty of campaigning and building bases of support among dispersed populations in far-flung regions. Moreover, territorial identities and rivalries often made it difficult for a party founded in one province or city to win support in others. As a result, while many parties emerged that represented a single city or province, few of these organizations developed into strong national parties. Some politicians managed to stitch together networks of supporters in various regions, but these alliances tended to be temporary and the parties that emerged from them were typically highly decentralized, weakly institutionalized, and prone to splits (Gibson Reference Gibson1996, 34–36).

Only in Uruguay did territorial cleavages give birth to strong parties.Footnote 9 As we shall see, Uruguay’s small size and absence of geographical barriers facilitated the construction of strong national parties. Moreover, the relative balance in resources and population between the capital city, Montevideo, and the countryside facilitated the development of a party system along center–periphery lines. Prolonged warfare between the two regions, including a siege of Montevideo that lasted years, helped strengthen partisan identities in Uruguay and laid the groundwork for the emergence of these parties. As discussed later in this chapter, balanced cleavages contribute to the construction of strong party systems by encouraging enduring political competition along cleavage lines and preventing one side from dominating the other.

Most important parties in South America during the nineteenth century arose from a religious cleavage, namely the cleavage between secular liberals and religious conservatives. Although this cleavage waned in importance in the twentieth century, in some cases the party systems that had emerged based on this cleavage endured. Throughout the nineteenth century, conservative and liberal politicians formed parties to promote their programmatic aims as well as their political ambitions. Conservative parties defended the prerogatives of the Catholic Church, whereas liberal parties favored freedom of religion and the separation of church and state. The liberal critics of the Church drew inspiration in part from Europe and the United States where liberal ideas were increasingly dominant in the wake of the Enlightenment. Although many Latin American liberals were practicing Catholics, they viewed the Church as an obstacle to progress and they resented its wealth and power.Footnote 10 Not only was the Church the largest landowner in Latin America, but it controlled numerous institutions, from schools and hospitals to cemeteries and civil registries.

Conservative and liberal parties often differed on a range of other issues as well, including federalism, free trade, and civil and political rights, but these issues did not generate the same degree of passion as religious differences. Moreover, their positions on these other issues tended to vary over time and across countries (Bushnell and Macaulay Reference Bushnell and Macaulay1994, 33–35; Safford Reference Safford, Graham and Smith1974, 72). For example, liberals often supported and conservatives frequently opposed federalism, free trade, and individual rights, but at times their positions were reversed.

Political parties arose from the religious cleavage in large part because it involved strongly held beliefs. Conservatives believed themselves to be the true defenders of the faith, and liberals viewed themselves as voices of reason, science, and progress. Religious fervor was often widespread among the population, and religious beliefs tended to provoke considerable passion, which politicians used to mobilize their supporters. According to Bushnell and Macaulay (Reference Bushnell and Macaulay1994, 35), conservatives “quickly discovered that religion was the most effective single cause with which to stir the popular masses into action on their side.”

Conservative supporters of the Church largely dominated Latin American governments during the first decades after independence, but liberals gradually gained control of the governments of many countries in the latter half of the nineteenth century and began to enact secularizing reforms that separated church and state, established freedom of religion, and stripped the Church of some of its property and institutions (Lynch Reference Lynch2012; Mecham Reference Mecham1966). Conservatives objected strenuously to these measures, creating parties and sometimes taking up arms to resist the liberal reforms.

Conservative and liberal parties, like those based in the center and the periphery, typically only evolved into strong parties where the religious cleavage was important and relatively balanced – that is, where both sides had numerous supporters and ample resources, as in Colombia and Chile. Unlike class and ethnic cleavages, powerful figures and organizations with substantial resources were often found on both sides of the religious divide.Footnote 11 The founders of successful parties used their networks, constituencies, and resources to form and sustain the parties. Conservatives drew on the resources and networks of the Catholic Church, which was the most powerful national organization in nineteenth-century Latin America. The Church provided manpower as well as ideological support to conservative parties, “with the parish priest often serving as conservative ward boss in elections and even as recruiting officer in times of revolution” (Bushnell and Macaulay Reference Bushnell and Macaulay1994, 35). The Church also controlled numerous charitable organizations, hospitals, and schools, all of which could be put at the service of conservative parties. Liberals, meanwhile, typically enjoyed the support of universities and schools, Masonic lodges, associations of firefighters, and literary societies. These institutions provided them with candidates, activists, and platforms for their campaigns.

Only where both sides of the cleavage were relatively strong did political entrepreneurs on each side typically have the incentives and the resources to build powerful parties. Where neither side dominated, each side of a cleavage felt pressure to invest in parties to keep up with or surpass the other. Party building in these countries often had a mutually reinforcing dynamic, with each side copying the other’s organizational investments and innovations. Elections were also more likely to be closely contested where the two sides were evenly matched, which contributed to party building since participating regularly in contested elections obliged the parties to engage in frequent organizing and campaigning. Where a cleavage divided the population relatively equally, parties typically made extensive ideological appeals since there were ample members on each side who would be receptive to such appeals. The appeals galvanized their supporters and antagonized members of the other side, thus helping to build partisan loyalties.

By contrast, elections tended to be contested less frequently where only one side of a cleavage was strong, since parties representing the weaker side typically had little chance of winning. As a result, both sides campaigned less frequently, established weaker ties to the electorate, and made fewer investments in parties. Even when contested elections did occur, the fact that the results were largely preordained discouraged both sides from campaigning extensively or building parties. The stronger side often eschewed making significant investments in party building because it did not need a strong party to dominate, whereas the weaker side often viewed party building as futile. The weaker side might run candidates in areas where it was strong, but not throughout the entire country, which prevented it from developing into a national party. In some cases, the weaker side also eschewed party building because it lacked the necessary leaders and resources.

Where cleavages were unbalanced, the leading candidates for national offices tended to come from the dominant side of the cleavage, often representing different factions of the same political party. Under these circumstances, competition tended to take a personalistic form, rather than an ideological one, since the different factions usually represented the same general ideology. These factions typically eschewed investments in organization and frequently did not survive the death or decline of their founding leaders. In some countries where cleavages were unbalanced, parties representing the weaker side failed to emerge or become serious competitors for political power. In other countries with unbalanced cleavages, parties representing the weaker side initially had some influence but became increasingly marginalized over time or disappeared altogether. In both cases, the failure of the weaker side to develop or maintain a strong party discouraged the stronger side from making investments in party building as well.

Where both sides of a cleavage were weak, strong parties also typically failed to emerge. Under these circumstances, neither side typically had the personnel or organizational resources to invest in party building. Moreover, prospects for party building were dim if neither side had many potential supporters to recruit.

Unfortunately, there are no time-series data on the strength of liberals and conservatives in nineteenth-century Latin America, but Mahoney (Reference Mahoney2003, 78) provides estimates of their strength between 1700 and 1850. Mahoney’s estimates have the advantage that they predate the emergence of liberal and conservative parties and thus are presumably exogenous from them. The disadvantage of his estimates is that they do not reflect the changes in the relative power of conservatives and liberals that took place during this period. As Table 4.2 indicates, only three South American countries – Argentina, Chile, and Colombia – had strong conservatives as well as strong liberals. Moreover, according to Mahoney, only Colombia had very strong liberals and very strong conservatives. The remaining countries had either strong liberals (Brazil, Uruguay, and Venezuela) or strong conservatives (Bolivia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru) but not both.Footnote 12

Table 4.2 Liberal and conservative strength in South America, 1700–1850

| Strength of liberals | Strength of conservatives | Degree of balance between liberals and conservatives | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Very high | Medium | Balanced |

| Bolivia | Very low | High | Unbalanced |

| Brazil | High | Low | Unbalanced |

| Chile | Very high | Medium | Balanced |

| Colombia | Very high | Very high | Balanced |

| Ecuador | Low | High | Unbalanced |

| Paraguay | Low | High | Unbalanced |

| Peru | Low | Very high | Unbalanced |

| Uruguay | Very high | Very low | Unbalanced |

| Venezuela | Very high | Low | Unbalanced |

Note: I used the following scale in converting Mahoney’s (Reference Mahoney2003, 78) scores. Countries receiving scores of 1.00 and 0.83 were coded as very high; 0.67 as high; 0.50 as medium; 0.33 as low; and 0.17 and 0.00 as very low. I scored Brazil because Mahoney only coded Spanish-American nations.

What led to the development of strong conservatives and/or strong liberals in some countries and not others? The strength of conservatives was closely tied to the influence of the Catholic Church (Middlebrook Reference Middlebrook and Middlebrook2000a), which in turn was shaped by ethno-racial demographics and human geography. The Catholic Church and conservatives tended to be stronger in inland and rural regions where tradition prevailed and rates of religiosity were high. Areas with large indigenous populations also tended to be a stronghold of conservatives and the Catholic Church. Indeed, the countries where conservatives were strongest – Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru – all had sizable indigenous populations in the nineteenth century. During the colonial era, the Church proselytized extensively in indigenous communities and grew wealthy in part owing to its ability to extract indigenous tribute and exploit indigenous labor. A strong and wealthy Church helped promote conservative ideology.

By contrast, liberals tended to be stronger in cities and coastal areas. These areas tended to be more open to international influences and to depend on and support free trade, which liberals often espoused. Liberals also tended to be stronger in countries with large European-origin populations. To a significant extent, liberal ideas originated in Europe and were diffused throughout Latin America by European immigrants (Gerring et al. Reference Gerring, Apfeld, Wig and Tollefsen2022). Countries with large Afro-Latino populations also tended to be a stronghold of liberals, as Table 4.2 shows. During the colonial era, the Church proselytized less in Afro-Latino communities, barred Afro-Latinos from the priesthood, and tolerated and even practiced slavery, all of which undermined the standing of the Church and conservatives among Afro-Latinos. Liberals, by contrast, often opposed slavery and made efforts to win support among the Afro-Latino population. Thus, liberal strength was correlated with the density of the Afro-Latino and European population as well as the percentage of the population that lived on or near the coast.

Nevertheless, we must be careful not to overstate the impact of human geography on the varying strength of conservatives and liberals. Nor should we exaggerate the impact that balanced social cleavages had on party development in the region. Although these variables were important, other factors also helped shape the fate of parties in the region.

Geographic Fragmentation

The prospects for party building in South America during the nineteenth century were also shaped by the level of geographic fragmentation of the countries. I define geographic fragmentation as the degree to which a country’s population is dispersed into different geographic zones. Geographic fragmentation matters for party building because it determines the ease with which parties can build national organizations and broad networks of supporters. During the nineteenth century, politicians in geographically fragmented countries had difficulty building national parties because they could not easily travel to or communicate with voters in many areas of their countries; nor could they establish or manage branches or affiliated organizations in these areas. Moreover, national identities tended to be weaker in geographically fragmented countries, and regional voters and politicians often distrusted national party leaders. By contrast, politicians had an easier time developing national organizations and followings in the smaller countries where the population was geographically concentrated.Footnote 13

There are a variety of ways to measure geographic fragmentation. One recent study by the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) measured geographical fragmentation as the probability that two people taken at random lived in different ecozones (Gallup, Gaviria, and Lora Reference Gallup, Gaviria and Lora2003, 11–12). This study found that Latin America was the most geographically fragmented region in the world (Gallup, Gaviria, and Lora Reference Gallup, Gaviria and Lora2003, 11). Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil had the highest level of geographic fragmentation within South America, whereas Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay had the lowest level of geographic fragmentation (listed in order from the most fragmented to the least).Footnote 14 The IADB study measured geographic fragmentation in the late twentieth century, but the level of fragmentation in Latin America was almost certainly worse during the nineteenth century when urbanization rates were quite low.

Unfortunately, given data limitations, it is not possible to produce a similar index for South American countries in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, but it is clear from the data that do exist that geographically concentrated countries produced much stronger parties than geographically fragmented nations. Of the countries that produced medium or strong parties in the nineteenth or early twentieth century, only Colombia had a high level of geographic fragmentation. Table 4.3 provides several indicators of geographical fragmentation circa 1900. The table shows that countries with fewer geographical barriers, smaller territories, denser populations, and larger cities had stronger parties on average. Railroad track and telegraph lines also covered a greater percentage of the territory in countries with strong parties than in countries with weak parties. In spite of the small number of observations, the differences in means are statistically significant at the 0.5 level (two-tailed t-tests) for all of the variables except territorial size and population per square kilometer. The last two variables are statistically insignificant because both Argentina and Colombia had relatively large territories and low population density in 1900.

Table 4.3 Geographic fragmentation in South America circa 1900

| Country | Internal geographic barriers | Largest city/total population (%) | Territory in km2 | Population per km2 | Railroad track/territory (%) | Telegraph lines/territory (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries with medium to strong parties | ||||||

| Argentina | Low | 17.1 | 2,806,400 | 1.6 | 0.590 | 2.48 |

| Chile | Low | 10.2 | 757,366 | 4.3 | 0.575 | 3.66 |

| Colombia | High | 2.4 | 1,135,550 | 4.0 | 0.056 | 1.55 |

| Paraguay | Low | 9.8 | 253,100 | 2.5 | 0.099 | 0.96 |

| Uruguay | Low | 29.7 | 186,926 | 5.2 | 0.925 | 6.61 |

| Average | Low | 13.8Footnote * | 1,027,868 | 3.5 | 0.449Footnote * | 3.05Footnote * |

| Countries with weak parties | ||||||

| Bolivia | High | 3.7 | 1,226,600 | 1.4 | 0.043 | 0.40 |

| Brazil | High | 4.0 | 8,528,218 | 1.7 | 0.179 | 0.40 |

| Ecuador | High | 3.9 | 307,243 | 4.1 | 0.163 | 1.72 |

| Peru | High | 4.4 | 1,769,804 | 2.6 | 0.101 | 0.47 |

| Venezuela | Medium | 3.1 | 942,300 | 2.7 | 0.090 | 1.13 |

| Average | High | 3.8Footnote * | 2,554,833 | 2.5 | 0.115Footnote * | 0.82Footnote * |

Note:

* A t-test comparing means between countries with strong and weak parties is significant at the 0.05 level for these variables.

Political entrepreneurs in the geographically fragmented South American countries faced daunting obstacles to the creation of national parties during the nineteenth century. As Table 4.3 indicates, most of the countries with weak parties had immense territories.Footnote 15 Brazil alone covered 8.5 million square kilometers at the outset of the twentieth century (República de Chile 1907, xiii).Footnote 16 All of these countries also had significant internal geographic barriers, such as enormous mountain ranges, swamps, forests, and jungles. The Andes, for example, separated the lowlands and the highlands of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru, and made journeys long and often treacherous. Moreover, during the nineteenth century, the population of these countries was typically spread throughout their territories, rather than being concentrated in one region or city. In Peru, for example, the population was relatively evenly divided among the northern, central, and southern departments, according to the 1876 census (Gootenberg Reference Gootenberg1991, 112–115). In the geographically fragmented countries, the largest city typically accounted for less than 5 percent of the country’s population.

To make matters worse, transportation infrastructure was extremely poor during the nineteenth century (Summerhill Reference Summerhill, Bulmer-Thomas, Coatsworth and Conde2006). Roads were often little more than bridle paths, bridges were scarce, and railroads were absent in most of the region. The weather could also be a major obstacle. During the 1800s, the road from Guayaquil to Quito was often impassible during the six-month rainy season and the trip took 14–21 days in the dry season, involving travel on foot as well as by mule (Henderson Reference Henderson2008, 7; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez1985, 16). The capitals of some of these countries, such as Bogotá, La Paz, and Quito, were located far inland, which precluded oceangoing transport, and South America had few navigable rivers connecting major cities. Even where it was possible to use ships to travel from one city to another, the trip was not necessarily an easy one. Indeed, during the nineteenth century, it took more time to travel by boat from some states in northeastern Brazil to Rio de Janeiro than it took to sail from these states to Portugal (Graham Reference Graham1990, 45).

The infrastructure gradually improved over the course of the nineteenth century. Many South American countries invested in roads. The government of Antonio Guzmán Blanco in Venezuela, for example, built 720 miles of roads during his first administration (1870–1877), more than double the number that had been built during the previous thirty years (Floyd Reference Floyd1982, 103). Governments also invested in telegraph and railroad lines. In 1870, Latin America had only 4,065 kilometers of railroad track, but this rose to 54,151 kilometers in 1900 and 115,786 kilometers in 1930 (Summerhill Reference Summerhill, Bulmer-Thomas, Coatsworth and Conde2006, 302). The growth in telegraph lines was even more dramatic: South America had only 4,000 miles of telegraph lines in 1870, but by 1900 it had 73,000 miles and by 1930 it had 183,000 miles (Banks and Wilson Reference Banks and Wilson2014). Nevertheless, the region still had relatively limited and unreliable communications and transportation networks at the beginning of the twentieth century. The telegraph lines frequently broke down, and the railroads typically only linked together a few major cities – often only those in close proximity to each other. Moreover, the vast majority of the population in South America lived in rural areas during the nineteenth century, and thus had limited access to the telegraph and railroad lines.

Geographical fragmentation impeded the development of national parties in several ways. The obstacles to communication and travel made it difficult for politicians and party leaders to campaign throughout the country, which meant it was hard for them to build up a national following. The barriers to communication and transportation also obstructed the creation of national organizations. Party leaders could not easily establish or manage regional branches or affiliated organizations. Nor could they ensure that regional leaders and affiliates hewed to the party line. In addition, geographical fragmentation strengthened local identities. During the nineteenth century, people in different regions typically identified with their region more than their country. Voters and politicians often distrusted candidates and parties from the capital or other regions, which made it difficult for them to establish a national base of support. Geographical fragmentation did not make it impossible to establish strong parties. Strong parties arose in Colombia even though it was extremely geographically fragmented. Nevertheless, geographical fragmentation represented a significant obstacle to party building.

By contrast, the geographically compact South American countries had significant advantages when it came to party building. In Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and to a lesser extent Argentina, the bulk of the population was concentrated in a small area, in or near the capital city. The concentration of the population, along with the lack of internal geographical obstacles and the development of railroad and telegraph lines, made travel and communication between different parts of these nations easier. This, in turn, enabled politicians and parties to develop countrywide followings and to manage national organizations. The geographical concentration of the population also facilitated the construction of party organizations and followings by strengthening national identities. Thus, it is not surprising that these four countries were among the first in South America to establish strong, national parties.Footnote 17

In sum, the level of geographic fragmentation combined with the nature of religious and territorial cleavages to shape party building in South America during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. To be sure, the level of geographic fragmentation and the nature of religious and territorial cleavages were not the only factors to influence party building in South America during this period, but they were the most important ones. The countries that had both balanced religious/territorial cleavages and geographically compact populations, namely Chile and Uruguay, developed parties that ranked among the strongest in the region by the late nineteenth century. Those countries that were geographically compact but lacked balanced cleavages (or vice versa), such as Argentina and Paraguay, were typically slower to develop strong parties, but by the early twentieth century, these countries had developed one or more parties of at least medium strength. The exception was Colombia, which developed two strong parties by the end of the nineteenth century even though it was not geographically compact. Colombia managed to develop strong parties not just because it had a balanced religious cleavage but also because this cleavage generated particularly intense and widely felt passions. Indeed, Colombia was the only country that Mahoney coded as having very high concentrations of both conservatives and liberals. Finally, the countries that had neither balanced cleavages, nor geographically compact populations, had only weak parties during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This includes Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela.

Conclusion

As we have seen, parties first emerged in South America in the middle of the nineteenth century, but only in some countries did they grow strong before 1930. Religious and territorial cleavages significantly shaped the development of political parties in South America. Strong parties arose in countries, such as Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay, where religious or center–periphery cleavages were intense and relatively balanced. Where both sides of a religious or territorial cleavage were strong, neither could dominate the other and each side had incentives to invest in party building in order to prevail in elections. By contrast, where only one side of the cleavage was strong, there were few incentives to invest in party building, and parties tended to be ephemeral, personalistic, and weak.

The fate of parties in nineteenth-century South America was also shaped by human geography. Strong parties arose in countries, such as Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay, where the bulk of the population was concentrated in a relatively small area with minimal geographical barriers. In these countries, politicians and party leaders could more easily campaign throughout the country, establish and manage regional branches, and develop a national organization and base of support. By contrast, geographically fragmented countries typically gave birth to weak parties. These countries usually had strong regional identities and significant barriers to internal travel and communication, which made it difficult to develop national organizations and ties to a large share of the electorate.

Chapters 5–8 show how the emergence of strong political parties in South America during the nineteenth and early twentieth century facilitated democratization in the region. Strong parties not only helped increase voter turnout and political competition but also played a key role in the enactment of democratic reforms that expanded the suffrage and established free and fair elections. In addition, strong parties facilitated the implementation and enforcement of these democratic reforms and reduced the likelihood of military coups. These positive effects tended to occur where at least one of the strong parties was in the opposition. Moreover, these parties had to be committed to taking power via elections, which typically only occurred once the emergence of a professional military impeded them from taking power via armed revolt.