It is very bad to sell land that was left by your father to assist you. People today are selling their land, and I know those people believe it is better for them to stay fifteen tears or twenty years with luxuries than staying eighty years with poverty. You will find somebody who sold land for ten million or twenty million [KSh]. He cannot stay with this money for six months. It’s because when one sells you get company. These people make you the chairman. They must follow you until the money is finished.

‘I feel that I want to slap him’

In early 2017, during the first months of my fieldwork in the neighbourhood of Ituura, where Nairobi’s expanding sprawl meets the tea-growing highlands of central Kenya, I spent practically all my time with Mwaura. Then nineteen years old, Mwaura was the son of my hosts and an unlikely university student from one of the neighbourhood’s poorer families. Sharing a love of football, we spent hours playing an old edition of the FIFA video game series on his second-hand laptop. On weekends, we went to the local ‘Motel’ to watch Premier League football, especially Mwaura’s beloved Manchester United, a team whose then turgid, workman-like style he was always capable of looking past.

For me and Mwaura, our lives of leisure obscured his family’s hardships. Mwaura’s father, Paul Kimani, a fifty-two-year-old long-haul lorry driver, made only sporadic appearances at the family home. The inconsistency of his earnings kept the family in a near-constant state of economic uncertainty. Mwaura’s mother, Catherine, was often forced to cobble together money for Mwaura’s university fees through borrowing from wealthier friends and relatives.

Nonetheless, these months were a time of optimism, the family’s hopes pinned on Mwaura’s fortunes after graduation, the aspirations for him to find ‘kazi’, formal paid work of the sort that would pay a consistent salary and help them ‘make it’ (kuomoka) to the ‘stability’ of something like middle-class status. With Mwaura stuck on the homestead due to strike action in Kenya’s university sector through early 2017, it was through him that I came to know the neighbourhood, its characters, and pressing dilemmas.

On one of our trips to the Motel to watch a football match, talking during half-time, Mwaura pointed out to me a middle-aged man from Ituura who was making soup for the other guests. Mwaura was appalled by this man’s situation because he was known to have sold a large portion of his inherited land.

‘He sold his land for like 7 million shillings at February!’, Mwaura exclaimed. ‘And now you’re a cook? You’ve finished that 7 million already!? How!?’ I was taken aback at Mwaura’s tone of condemnation. At the time, I assumed he was echoing his father’s sentiments. Like other senior men from Ituura, Kimani regularly insisted that selling ancestral land was wrong, tantamount to parental neglect, a failure to pass inherited wealth forward to the next generation. But, as Mwaura’s words pointed out, this very same land was becoming extremely valuable in the shadow of an expanding Nairobi. I asked Mwaura why someone would have sold such a valuable asset. ‘Some people you can’t understand’, he explained. ‘They sell their land because they’re poor.’ I asked what he had spent the money on. ‘These ones with short skirts’, he said bluntly, a reference to the women who sometimes accompanied older men to the Motel and were seen to be part-time sex workers.

The speed of expenditure had been shocking. ‘He was not seen for like four months, and he came back with just 50,000 … Imagine! He was taking taxis around everywhere’, he told me, emphasising the lavish expenditure land sale had afforded this man. ‘If you’ve got money, how can you walk?’, he asked rhetorically. I asked him who had bought the land. According to Mwaura, the buyer could only be identified as ‘some outsider’.

In 2017, Mwaura’s judgement of this neighbourhood man echoed wider debate taking place across Kiambu about the existential dangers of selling inherited, ‘ancestral’ land. For its smallholder families, the vestiges of a peasantry now working for wages, land is inherited on a patrilineal basis but has been divided over successive generations into smaller and smaller chunks. With shrinking plots, it was becoming increasingly attractive for senior men to sell their family land, sometimes unilaterally, to generate ‘chunks’ of money to cover household debts, to launch small-scale businesses such as chicken rearing, but also, to access heightened lifestyles of conspicuous consumption. Local commentaries on such acts spoke of the dangers of alienating such family heirlooms, the effects of ancestral ‘curses’ (kĩrumi sing., irumi pl.) left by long-dead grandfathers who decreed that ancestral land should never pass out of family ownership. The speed at which land money was spent was often taken to be the kĩrumi at work, destroying the lives of land sellers, turning foolhardy excessive consumption into poverty and destitution. With not an ounce of sympathy, local newspapers condemned the so-called ‘poor millionaires’ of Kiambu County who sold their lands but spent the proceeds on alcohol and women, only to be left with nothing in the end (Njagi Reference Njagi2018).

What incensed Mwaura that day, however, was not simply that the man in question had made an economic error nor transgressed ancestral wisdom but rather that his act of sale constituted one of fatherly neglect, that he had sacrificed his son’s future by misappropriating the proceeds as much as selling in the first place. ‘Now he’s not sending his children to school, they’re just idling’, Mwaura continued. ‘One of his kids is working in that place and he should be in college! Sometimes I feel that I want to slap him. He should have sent his son to college first – then drink!’ His intensity trailed off, and our attention returned to the football. Mwaura never slapped the soup-seller, and our attempts to ask him about his land sale at his butchery a few weeks later were met with denial. There was no curse upon his land, and no danger, the man insisted.

What Mwaura could have not known then was in a few years he too would be put in the same unfortunate position as the soup-seller’s son. With his own grudging consent, Kimani would sell a large part of his family’s land for millions of shillings, passing on none of the proceeds. In 2022, Mwaura continued to live on his family’s shrunken plot of land, hoping that his father would someday come through with his part of the sale money, while becoming increasingly bitter towards his hypocrasy.

I mean, Kimani used to say all this shit about selling land, never sell land and then all of a sudden he’s the one selling land. What would you make of him as a man actually? Surely? It’s weird. It’s weird.

The trajectory of Mwaura, my friend and closest interlocutor, across the years between 2017 and 2022 captures a central topic in this book: the fate of Kiambu smallholders as their meagre plots of land skyrocketed in value in the shadow of an expanding Nairobi. In a region already profoundly shaped by colonial histories of land expropriation, Peasants to Paupers explores the terrain of peri-urban Kiambu as the city extends into its poorer northern hinterlands. Drawing upon my fieldwork with Mwaura’s family, his neighbours, and friends in Ituura over these years, this book illuminates the way an urban frontier encounters a stratified post-agrarian landscape, creating new categories of ‘winners and losers’ amidst the beginnings of a construction boom. While some smallholder families were building rental housing on their land and becoming landlords, for others the commodification of land created a crisis of kinship as male heads of households sold ancestral land at the expense of their children. Within this urbanising terrain, this book observes the hollowing-out of a moral economy of patrilineal kinship. Despite the insistence of senior men that their land was ‘ancestral’ and therefore inalienable, land sales took place, uprooting families, depriving children of their inheritances, and accelerating a region-wide process of downward mobility as younger generations contemplated their fate as a new class of landless and land-poor paupers.

Peasants to Paupers traces the effects of this process by exploring a wider loss of confidence among young men in the moral horizon of patrilineal kinship and its emphasis on working towards the future by returning wages to the homestead. Faith in this vision is being eroded on the one hand by the grim economic terms of the peri-urban informal economy, with low-paying jobs that operate on a piecemeal basis. But confidence in a normative vision of masculine responsibility is also undercut by land sales themselves – experienced within patrilineal families as acts of moral transgression that render young men like Mwaura doubly hopeless, contemplating his father’s betrayal of kinship’s future-orientation and the principles of passing on wealth. Such overt practices of private accumulation served to compound a sense of patrilineal kinship’s breakdown when they came at the cost of others. It was not only senior men who were seeking to escape poverty through land sale. Amidst rural destitution, young men were seeking desperate and piecemeal attempts to cope with hopelessness about their futures through drinking alcohol. Meanwhile, young women were cultivating extra-marital relationships with wealthy ‘sponsors’ precisely because their male peers were ‘wasting themselves’. Knowledge of such relationships further entrenched male distrust of women’s intentions, undermining the ideal of the harmonious patrilineal household, and fomenting a gendered self-perception of male abjection.

Against the backdrop of an eroding belief in the achievement of patrilineal household, Peasants to Paupers explores how Kiambu’s young and poor cope with their downward mobility. It charts their challenging journeys as they ward off hopelessness, struggling not to become ‘wasted’ like their alcoholic peers. It draws out the moral debates taking place on the economic margins about whether work can materially provision a reasonable middle-class future. These debates reveal the limits of a bootstrap mentality of labour’s virtue under conditions of wage-limited precarity. While some manage to maintain their hopes for a better tomorrow, for others the grim realisation that they will never meet their aspirations prompts a deep hopelessness and a ‘giving up’ on the future.

In highlighting these themes, this book argues that Nairobi’s expansion is driven not only by the outward push of an urban frontier but by the vulnerability written into the city’s rural hinterlands by the region’s colonial and post-colonial history. The urban frontier’s ‘expansion’ can just as easily be seen as a ‘retreat’ for Kenya’s peri-urban post-peasantry, no longer able to maintain the moral economy of patrilineal kinship and keep the family tethered to land. In such a changing landscape, this book argues for the study of kinship’s moral economy as a critical field, especially as scholars of an urbanizing Africa begin to explore the way expanding cities shape their once-rural hinterlands. Across the globe, enormous numbers of people’s lives are defined by their access to land, which is in turn mediated by kinship. In such settings, kin relations themselves become central mechanisms in the creation of new class distinctions, shaping economic fates across generations. This book closes by calling for a return to studying the imbrications of class, kinship, and landed property.

Land, Class, and Kinship in the Shadow of Nairobi

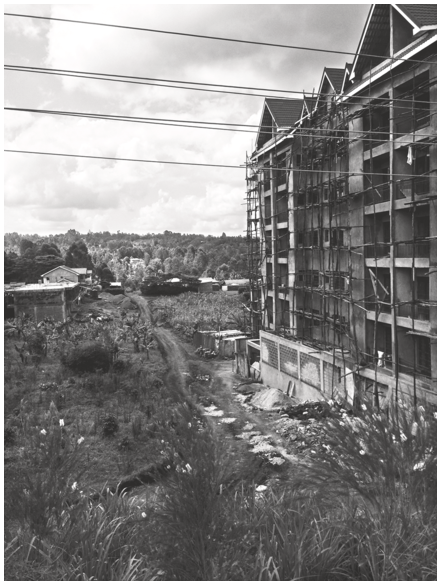

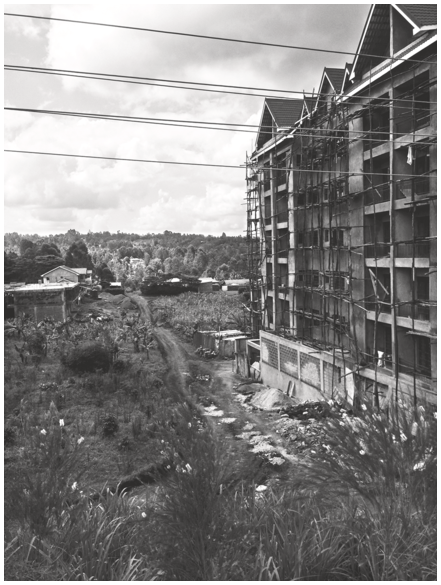

The neighbourhood of Ituura lies at the interstice of old and new central Kenya – between rural central Kenya, defined by its enormous tea farms belonging to members of the Kikuyu elite, and the new urban sprawl created by Nairobi’s approach. Ituura’s location is east of the Thika Road, a new urban corridor completed under Mwai Kibaki’s presidency in 2012, part of its Vision 2030 plan to transform Kenya into a prosperous middle-income country with Nairobi at its centre (Smith Reference Smith2019). The road’s construction led to a new forest of high-rise apartments springing up around it, shaping locations as distant as Ituura (Chapter 16; Figure I.1). Nairobi’s urban sprawl has replaced coffee farms in towns like Ruaka, some twenty kilometres south of Ituura, turning it into an enclave of aspiration, where upwardly mobile young Kenyans seek to live amongst the night clubs and sports bars (Lockwood Reference Lockwood2023a). Unlike the new neighbourhoods of ‘lower Kiambu’, such as the Thika Road, areas of ‘upper Kiambu’ like Ituura remained a hodgepodge landscape in 2017 – where farmers tilled the land next to new gated communities, where new ‘working classes’ were moving into high-rise apartments a stone’s throw from poor smallholder families deriving their incomes from work in the informal economy (Mito Reference Mito2024).

Figure I.1 New high-rises in upper Kiambu, 2018.

Figure I.1Long description

On the right side, an incomplete block of high-rise apartment towers over the surrounding countryside. The building is a concrete shell, surrounded by wooden scaffolding, conspicuously empty. Below it, a rust-red road cuts through idle land. Low-rise stone buildings lie beyond them, besides smaller apartment buildings and houses. In the distance are treelines rising upwards towards a hill. In the foreground, flowers are growing, indicating that this photo has been taken from a road-side, looking outward into peri-urbanising central Kenya’s uneven countryside.

Working across similar city outskirts across the Global South, scholars in Urban Studies and Human Geography have remarked upon the protracted, piecemeal nature of urbanisation as city sprawl expands into countryside – that it proceeds on a ‘plot-by-plot’ basis (Karaman et al. Reference Karaman, Sawyer, Schmid and Wong2020), defined by the incremental and contested commodification of land (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2020; Gillespie and Mwau Reference Gillespie and Mwau2024). As large infrastructure projects, roads especially, spread out across Africa’s urban peripheries, new rentier economies have emerged (Gillespie and Schindler Reference Gillespie and Schindler2022; cf. Christophers Reference Christophers2020). Local actors anticipate the increasing value of adjacent property. Even long before it is built, infrastructure provokes a logic of demarcation, as residents seek to delineate landholdings in anticipation of sale or construction. In northern Kenya, for instance, Hannah ElliottFootnote 1 has described how the anticipation of the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport Corridor (LAPSSET) led to the ‘propertying’ of land around the town of Isiolo as residents sought paper documents evidencing their ownership of what was now valuable land. Thomas Cowan (Reference Cowan2023) has described the ‘non-linear’ incorporation of rural working classes into the property boom in Gurgaon, who lack the capital to become wealthy rentiers. Others point to more ambiguous effects. Helga Leitner, Eric Sheppard, and Emma Colven (Reference Leitner, Sheppard and Colven2022) have described the ‘market-induced displacement’ in Jakarta’s surroundings. Residents of informal settlements are able to take advantage of land’s exchange value through sale yet find themselves isolated from the social networks that had supported their lives. The effect of such processes are settings precisely like Kiambu. Neither urban nor rural, it is part of an extended landscape of peri-urban inequality that incorporates both agglomerations and hinterlands.Footnote 2

Heightened aspirations for middle-class lifestyles are also rising in Kiambu – desires for social and economic distinction amplified by images of wealth projected by an expanding Nairobi; the newly built shopping malls; and gated communities of the ‘working class’, salaried white-collar workers. Ituura residents like Mwaura’s family knew they had not ‘made it’ to the status of economic ‘stability’ they described. Yet they aspired to its material trappings – living in a stone house, owning a car and a large flat-screen television, and educating children who would go on to prosper in their own right. ‘We are somewhere,’ was how Mwaura described his family’s economic predicament. Carola Lentz (Reference Lentz2020) has noted that the very term ‘middle class’ is often used by scholars to describe people who may not invoke the category themselves, and I retain its use as a way of describing how economic life is oriented towards ‘middleclassness’ as an aspiration towards a status not yet achieved, a recognition of its precarity (Mercer and Lemanski Reference Mercer and Lemanski2020).

Mwaura’s education, and the hopes his family attached to his future, provides a case in point. But as his story, which plays out across this book, shows, land plays a critical role in buttressing these projects of social mobility, enabling residents to live close to the city, providing a home, a base from which cash can be pursued. Families like Mwaura’s dreamed of building rental housing, known as ‘plots’, on their land in the future, turning it into a rent-producing asset. Other families in Ituura had already done so and provided examples of routes to prosperity that their neighbours sought to emulate. Patrilineal narratives about the importance of retaining land recognised and incorporated these new possibilities of earning incomes through rent. These new potential income streams only served to heighten discourses that emphasised land retention, while throwing into relief the ‘winners and losers’ of this construction boom.

This book speaks to a growing conversation in the anthropology of Africa about the obstacles and blockages faced in projects of class aspiration and the creation of good lives. It does so by centring the position of land within them. Speaking across anthropology, African studies, and urban studies, I look at the urban frontier from ‘the other side’, as it were, exploring the way poverty and destitution in city hinterlands allows the frontier to move forwards. But I am also interested in the way this process plays out within kin relations – the way kinship itself mediates transfers of land on this frontier, and their consequences within the life events of families and the economic fates of its members.

In Kiambu, land is ostensibly held within family patrilines, though owned in legal terms through freehold title deeds, often in the names of male heads of households. Access to it is mediated by what Maxim Bolt (Reference Bolt2021) has called a ‘fluctuating formality’. While ‘customary’ or ‘patrilineal’ notions regarding inheritance emphasise the passing on of ancestral land, in practical terms, male landowners with freehold title deeds often possess the power to sell land independently, regardless of their family’s consent.Footnote 3 This puts dependent kin in a vulnerable position, a topic to which this book draws substantial attention. Yet it also draws attention to the failure of normative ideas that stress the inter-generational transfer of land. Sons expect to inherit ancestral land, and senior men wax lyrically about the dangers of selling it, of failing to pass it on. When fathers do sell land, the result for those concerned is not only market-based displacement in practical terms but in subjective ones, a desperate rupture in the heart of the family and the very idea of inter-generational obligation. Children face the prospect of losing out on their future inheritance, the security of land, and the downward spiral into landlessness and the poverty that entails – all at the hands of senior kin.

In this regard, the city’s expansion provokes deeper questions about the way urbanisation is mediated by kin-based attachments to land and the extent to which a moral economy of patrilineal kinship creates a bulwark against its alienation on the market. By the ‘moral economy of patrilineal kinship’, I refer to both an idea and ideal of the family that stresses the obligations of male breadwinners to generate domestic wealth and create the social future in kin. This concept builds on historian John Lonsdale’s landmark essay ‘The moral economy of the Mau Mau’ (Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992), which delves deep into the history of moral thought in central Kenya to reveal the powerful relationship between wealth and upstanding masculine personhood, underpinned by labour.

Throughout the book, words in Gĩkũyũ are underlined, while Kiswahili and related Sheng (Nairobi slang) terms are italicised. The frequency of both speaks to the setting of the fieldwork, where cosmopolitan Nairobi blends into ‘Kikuyuland’ beyond. To recount the foundations of Lonsdale’s argument, the Kikuyu people of central Kenya emerged as an amalgamation of successive waves of migrants, earning their name after the mũkũyũ tree that grew throughout the central highlands. Over the three centuries before 1900, Bantu-speakers arriving at the foothills of Mount Kenya began the difficult task of clearing the dense forest wilderness to create space for sedentary agriculture. The arduous work of hewing down trees with axes and iron bars gave rise to what Lonsdale has called a ‘labour theory of value’ (Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 333), not a Marxian one, but a moral one glimpsed in other peasant societies across Africa and Europe (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1987; Hann Reference Hann2018). Kikuyu were morally and materially invested in reproduction. Material success afforded moral personhood (cf. Guyer Reference Guyer1993). Labour became the guarantor of public status. Kikuyu proverbs exhorted men and women to ‘kuuga na gwĩka’, to ‘say and do’ (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 340), to deliver on one’s promises. Derek Peterson expanded this inquiry into the central Kenya’s moral thought, illustrating how it valorised the ‘prosperity’ and ‘flourishing’ (kũgita) of the homestead and its thick hedges that kept the forest wilderness at bay (Reference Peterson2004: 11). Male household heads were athuuri (literally, ‘those who choose’, still the word for married adult men today). Successful patriarchal figures ‘led opinion because their homes were far from going to ruin’ (Peterson Reference Peterson2004: 337). Their wealth was in land and people – migrant clients received from elsewhere (ahoi), wives (atumia), children (ciana), and land (ithaka). Labour was a critical source of personal virtue, of upstanding masculine respectability.

For Kikuyu, Lonsdale tells us, it was the wealth that labour produced which measured its worth. Kikuyu migrants journeyed further southwards towards contemporary Nairobi, seeking remembrance as ‘founders’ of new family lineages that they would create alongside their relatives and friends when acquiring and clearing land on the frontier (Droz Reference Droz1999). Economic success was thought of as enabling, purposed towards social continuity, and providing property to be divided amongst sons endowed with the ‘upbringing’ (irĩĩri) to make best use of what had been left behind by ancestors – ‘those who left wealth’ (atiga-irĩ) (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 334; cf. Kinoti Reference Kinoti2010: 34–6). Family life, its reproduction and material advancement, was a marker of what Lonsdale calls ‘civic virtue’ – the reputation earned in social relations with others whereby one’s success signalled the longevity of one’s lineage, agreed upon as the ultimate end (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale and Falola2005: 564). ‘Wealth in people’ was a stake in the future.

As this book goes on to show, responsibility for the family remains a powerful future-orientation in contemporary central Kenya, a moral horizon through which upstanding masculine personhood is achieved. We will see numerous examples of senior men extolling their own virtue by representing themselves as workers who diligently support and supported their families and their future flourishing. These notions resemble other male ‘provider’ identities across Africa that have emerged from the experience of labour migration in the colonial period (see, e.g., Silberschmidt Reference Silberschmidt and Arnfred2004; Mavungu Reference Mavungu2013; Wyrod Reference Wyrod2016; Smith Reference Smith2017; Baral Reference Baral2021; van Stapele Reference van Stapele2021). Amongst Kiambu’s smallholders and their male heads of households, notions of masculine personhood have been tethered to the generation of ‘off-farm income’ (Kitching Reference Kitching1980: 3) since the colonial period, when the alienation of land to European settlers and the imposition of taxes forced men out of the house and into the labour market. In that context, notions of moral masculinity have been reframed as the return of wealth to the homestead (Chapter 1), a site of reproduction, of care and obligation to the future, the duty to produce it in the first place. Such provider identities turn upon what Mark Hunter (Reference Hunter2014) has called ‘the bond of education’, the investment of wages and hope in the future social mobility and flourishing of one’s children. These obligations evince the ongoing character of what Lonsdale characterised as the ‘dynastic’, patrilineal aspect of Kikuyu moral economy.

These masculine identities are tethered not only to the provisioning of wages, however, but also to the retention of land as a home to raise one’s family and where one is eventually to be buried (Shipton Reference Shipton2009; Droz Reference Droz, Jindra and Noret2011). In principle, Nairobi’s land frontier is kept in check by powerful ideas of patrilineal obligation that coalesce around land’s status as an ancestral home – that it should never be sold, that its purpose is to undergird the reproduction and flourishing of future generations. At this juncture of city and countryside, the notion that inherited land is ancestral remains something of a precarious bulwark against urban expansion. It is categorised as a type of inalienable wealth (Weiner Reference Weiner1992) that provides the basis for the family’s social reproduction, ‘limited goods’ (Gregory Reference Gregory1997: 79) entrusted to senior kin as guardians of it passing on through the generations.

However, in Kiambu’s proletarianising landscape, these moral horizons of domestic prosperity are fading. Once a prosperous coffee-growing region of smallholder farmers, Kiambu today is a place where peasant livelihoods have been eroded by limited access to land, caused in no small part by its subdivision within families to multiple heirs. Shrinking smallholdings is combined with the extremely high cost of land, which rarely allows junior kin to purchase new holdings elsewhere unless endowed with capital by their elders (who often have to sell land to buy elsewhere in the first place). Having reached what Tania Murray Li (Reference Li2014a) called ‘the end of the land’, we can observe the consequences of what Deborah Bryceson (Reference Bryceson2019) has called a process of ‘de-peasantisation’ marked by the end of viable smallholder farming, a generational shift towards wageless life and outright pauperisation in a world of cash dependence and job scarcity (Denning Reference Denning2010). During the famous ‘Kenya Debate’, political economists argued about whether a prosperous ‘middle peasantry’ could emerge on the margins of capitalism, producing commodities and flourishing through their sale (Orvis Reference Orvis1993). This book affirms the view of Apollo Njonjo (Reference Njonjo1981), who described central Kenya’s peasantry as ‘workers with patches of land’, reliant upon wages to provision their households. Kiambu smallholders today correspond to Njonjo’s description of ‘a highly weakened peasantry’ struggling to maintain its status as a property-owning class (Njonjo Reference Njonjo1981: 31). Amiel Bize (Reference Bize2020) has used the term ‘post-agrarian’ to describe this type of setting, where rural livelihoods are no longer viable, prompting a turn away from farming and towards income-generating strategies based upon the proximity of towns and cities. In contrast to the new urban agglomerations of ‘lower’ Kiambu, its ‘upper’ western highlands remain rather more rural, and its political economy resembles these characterisations of a destitute countryside, a context deeply shaped by colonial histories of land expropriation (Chapter 1). To that end, this book characterises Kiambu’s economy at the grassroots as one of ‘peri-urban poverty’, evoking this history and this wider process typical of rural settings undergoing ‘de-peasantisation’.

Under these conditions, land’s rising value makes sale extremely tempting, worth far more than anyone in Ituura could earn in the informal economy. In 2016, an acre plot in Ruaka, a town close to Ituura, cost 59,600,000 KSh (HassConsult Limited 2016).Footnote 4 In 2022, it had risen to 92,000,000 (HassConsult Limited 2022). Commentators in Kenya’s public sphere have argued that ‘we need to look at ancestral land with less sentimental attachment so that we can realise its capital value’ (Kiereini Reference Kiereini2020). Ancestral land, idle and unproductive, so the logic goes, ought to offer more than just ‘dead capital’. It is hardly surprising that part-time proletarians might need to sell their land to cover shortfalls in their household budgets. Such are the new accommodations kinship theory is making for the market that Kenya’s Nation Television broadcast a report about a man exhuming his wife’s body to sell his ancestral plot (NTV Kenya 2020).

In Kiambu, moral arguments for land’s inalienability, though powerfully made, were therefore floundering in the face of a combination of peri-urban poverty and market opportunity. In practical terms, this book explores the way an approaching land market enters people’s lives at the site of kinship through an event-based ethnographic approach (Kuper Reference Kuper2018; cf. Moore Reference Moore1987) that draws attention to consequences – towards the changing life fortunes of those who live this complex scenario. I focus especially on patterns of socio-economic differentiation emerging from this terrain, as sons find their future inheritance sold by their fathers, turning them into a new landless poor.

In addition, this book explores the way underlying ideas and ideals of kinship’s social contract are undermined by these events, breaking moral and existential principles of passing on land within the family. Under such conditions, it is not only land’s status as inalienable that ‘melts into air’, but the moral principles that are believed to underwrite kinship, producing deep new uncertainties. Cases of land sale like the soup-seller’s son and Mwaura, as we shall see in this book, illuminate the extent to which the possibilities of individual accumulation from land sales not only disappoint expectations of distribution within the family but are seen to constitute the total subversion of this unwritten patrilineal contract. Younger kin lose faith in their elders, elaborating upon their hypocrisy, their ‘desires for money’ (tamaa ya pesa). They observe the hollowing out of patrilineal kinship’s underlying moral principles by market conditions, resulting in a corrosive short-termism and a dissolution of the social bonds between generations. Those like Mwaura whose fathers have sold land lament precisely kinship’s failure to be anything other than a discourse, a failure of word to bind deed.

This book’s argument therefore concerns not only the objective unmaking of corporate lineages on an urban frontier but a loss of confidence in the idea of patrilineal kinship, its own moral economy of landholding and inheritance that tethers families to their land. In one sense, this process of dislocation is brought about by changing property values and the opportunities for a new ‘binge economy’ (Wilk Reference Wilk2014) in land that undermines the moral principles underpinning long-term social reproduction. But in another, the urban frontier’s arrival is taking place because faith has already been lost in the vision of patrilineal futures and the place of land and domestic prosperity within them. Kiambu’s colonial history, its slow-burn process of turning peasants into proletarians and now, landless paupers, has already done much to erode belief that a freestanding house next to a farm, underpinned by stable cash earnings, can ever be materially achieved. This loss of faith - or, indeed, confidence - in kinship’s moral economy encourages members of Kiambu’s poor underclass to ‘cash out’ of the peri-urban struggle and seek to accumulate for themselves as individuals while shedding obligations to kin.

Eroding the Moral Economy of Kinship

If patrilineal kinship’s relationship with land is dissolving amidst an approaching urban frontier, how should this process be understood? As we have seen, scholars of the Global South’s expanding urban peripheries are describing the tensions brought about by the rapid commodification of land. These findings prompt a renewed interest in literature concerned with the ‘land question’ in rural Africa – the effect of colonial-era dispossession on patterns of landholding, the introduction of land tenure systems by colonial governments, and their consequences. Across Africa, an abundance of land in the pre-colonial period has given way to scarcity and population pressure in the colonial era and after (Iliffe Reference Iliffe1987), with the effect of increasing competition over land, often strait-jacketed within the family unit (Berry Reference Berry1993; Peters Reference Peters2002, Reference Peters2004; Amanor Reference Amanor2010; Boone Reference Boone2014). In southeastern Ghana, for instance, Kojo Sebastian Amanor (Reference Amanor2010) has shown how the commercialisation of agriculture has gone hand-in-hand with the emergence of ‘individual’ farms. Practices of sharecropping have led to growing contestation over land within family lineages and the exclusion of youth. In Malawi, Pauline Peters (Reference Peters2002) has examined the effects of land’s commodification, noticing an intensifying struggle between family members over scarce land. In central Kenya, Fiona MacKenzie (Reference Mackenzie1989) has shown the gendered conflicts over land produced by land scarcity and the insistence of men upon patrilineal inheritance. In a recent survey of these works, Catherine Boone (Reference Boone2014) has highlighted the effect of land tenure reform in adding further complexity to these processes of commodification and exclusion (see also Shipton Reference Shipton2009). Drawing upon the research of Edward OntitaFootnote 5 and Samuel Orvis (Reference Orvis1997) in Kisii County, Boone shows how land conflicts may appear ‘apolitical’ insofar as they take place within the family, but these conflicts often have roots in state processes of land tenure reform which enshrine land in the possession of household heads through freehold title deeds, fomenting tensions about whose claims are recognised. While some scholars have idealised the resilience of ‘customary’ notions of land tenure – the idea that access to land is fluid and negotiable (see, e.g., Shipton Reference Shipton2009) – the grain of these empirical studies goes in the opposite direction, elucidating the way competition over scarce plots is narrowed to the sphere of the family, and how land conflicts create new ‘winners and losers’, new classes of land rich and land poor ever more reliant upon cash wages (Peters Reference Peters2004).

To the degree that land tenure reform, population pressure, and commodification across rural Africa have fuelled conflict over land within the family whilst sharpening inequalities and undermining social reproduction, it is not only kinship relations that are undermined in an objective sense but the very ideas in which these relationships are embedded – the way kinship is understood in local terms as a moral bond that promote resource pooling and, especially, the generational transfer of wealth from parents to children, particularly from fathers to sons. I frame these visions of economic life, defined by paternal obligation, as ideas and ideals of patrilineal kinship’s moral economy.

My understanding of ‘moral economy’ is informed primarily by E. P. Thompson (Reference Thompson1971). To reprise Thompson’s original argument, it requires stating that ‘the moral economy’ itself was a claim. His work concerned grain riots in eighteenth-century Britain, taking place in the wake of new rapacious dynamics characteristic of a mechanising agriculture as farmers, millers, and merchants sought to inflate prices with no regard for the fortunes of buyers. Workers in these grain riots made appeals to ‘the commonweal’, the ‘old’ norms of fair prices in times of hardship. In a moment where new logics of profit came to the fore, England’s workers, peasants, artisans, and paupers used imaginations of the ‘old’ paternalist model to question the price of commodities. Thompson’s suggestion was not that such moral economies ever necessarily existed but rather that in the context of unfair food prices, grain rioters were appealing to a ‘traditional view of social norms and obligations’ that were already in the process of being undermined (Reference Thompson1971: 132, 79). The ‘moral economy of the poor’ was a set of invented traditions of the popular imagination – ideas about just custom rather than custom itself; the obligations not met by England’s profiteers.

To embrace a definition of ‘moral economy’ as a set of ideas and ideals through which economic and social relationships are made meaningful, rather than to solely describe those relationships themselves, avoids familiar dangers of reification. Chris Hann (Reference Hann2018) has called it a ‘clumpish term’, and James Carrier (Reference Carrier2018) has gone to the lengths of setting out how moral economies congeal through repeated economic transfers to evoke a sense of Polanyian embeddedness.Footnote 6 My intention is to examine moral economy in Thompson’s terms, as a fading notion of the moral underpinnings of material relationships, already being undone by the commodification and expropriation of patrilineal land. As in Thompson, the moral economy of patrilineal kinship has both an ‘ideal existence’ and a ‘fragmentary real’ one at this moment of urban transformation and deepening proletarianisation (Reference Thompson1971: 88). To study ideas of moral economy in this way entails a flexible, looser approach to the relationship between economic arrangements and moral sentiment that is changeable, the subject of moral reflection, evaluation, critique, and debate. That is not to retreat into pure idealism and obscure the material significance of patrilineal kinship, its patterns of landholding and wealth transfer. Far from it, I use this approach to explore the notions my interlocutors hold of patrilineal kinship’s material economy – the tangible relations of distribution forged through family relationships, especially when it comes to inheritance relations, and the ideas and expectations that surround them. I therefore use the notion of ‘moral economy’ to examine the ways economic relationships within the patrilineal household are conceived of in contested moral understanding, to describe a vision of kinship, its ideal workings, the forms of wealth transfer that it enables, and the moral principles seen to underpin them. Furthermore, I seek to situate these ideas and domestic economic arrangements within the wider political economy of central Kenya across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Critically, that ‘moral economy’ can be framed as both an ‘idea’ and an ‘ideal’ means that it can be undermined as such through contradictory practice and changing dynamics in the political economy. These terms have use when it comes to the growing sense Kiambu residents have of its erosion – that it is becoming hollowed-out as a meaningful way of understanding economic life as family-based obligations give way to individualist projects of self-realisation and fulfilment such as the land sales this book discusses. In previous writing (Lockwood Reference Lockwood2020a), I had thought to frame such ideas of patrilineal kinship as a ‘hegemonic’ moral norm stressing the achievement of male breadwinners in sustaining their families. But as we shall see, those like Mwaura – who lost out in land sales conducted by their fathers – realised for themselves the extent to which the patrilineal moral economy held no hegemony. In fact, it was a fragile moral narrative promulgated by patriarchal figures but possessed no normative capacity to police action towards the meeting of family obligations, even if it could be leveraged for critique.

We have already seen the premises of this vision of moral economy, an imagination of household prosperity underpinned by male effort and agency. In the first place, this book shows the persistence of such conservative narratives by illuminating the perspectives of senior men on land, labour, and obligation (Chapter 1). Like Jomo Kenyatta, whose Facing Mount Kenya (Reference Kenyatta1965 [1938]) envisioned an arcadian republic of elders, celebrating men for their ‘good management’ of the homestead, Kiambu men today enunciate a labour theory of patrilineal virtue won through meeting obligations to kinship’s future, a vision of moral economy premised upon the capacity of male heads-of-household to generate wages and retain their ancestral land. Theirs is a ‘dynastic’ theory of kinship (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992), intimately intertwined with landholding identity. They articulate the virtue of economising, a suspicion of liquid wealth, and a desire to invest in the sources of social reproduction. This vision of a lineal moral economy recalls classic anthropological attention to themes of lineage such as Meyer Fortes’ fieldwork amongst Tallensi people in present-day Ghana. Fortes took a strong interest in the ideas that underwrote kinship structures, arguing that ‘the fundamental axiom of parenthood’ buttressed the domestic economy amongst the Tallensi (Reference Fortes1967 [1949]: 162–3). Tallensi ideas about the ‘moral bond’ between parents and children was the origin and concern of a wider political economy premised upon the reproduction and continuity of lineage. Ideas about the morality of retaining land specifically recall Parker Shipton’s classic Bitter Money (Reference Shipton1989) thesis, which described how Luo patriarchal figures viewed the channelling of wealth towards self-interested ends as the antithesis of proper investment in social relationships (cf. Schmidt Reference Schmidt2020). Land sale in particular was seen as an anti-social transaction, tantamount to selling the ancestors who had been buried in it (cf. Shipton Reference Shipton2009). As I go on to show, the basis of such ideas of moral economisation lies in patrilineal kinship’s self-expressed principles, an emphasis on reproducing the future as a vital existential impulse, as much as a moral one (Chapter 3).

Along precisely these lines, Kiambu men emphasised the dangers of selling land, and ‘eating’ the money it generates, decrying the failure to pass land onwards into the future, to pave the way for future generations to flourish. They valorised the virtue of working for low wages rather than selling land and indulging in the ‘fun’ (raha) of alcohol. These discourses spoke to the challenge of holding on to land and kinship through working for money under conditions of peri-urban poverty, celebrating the achievement of ‘hanging on’ and working for a better life. Yet, they also threw into relief the ways in which people might seek to ‘exit’ the struggle for reproducing the patrilineal household, relieving themselves of the burden of working for low wages by trading-up their moral commitments for the short-term ‘fun’ of drinking. This book observes a growing tendency – and local anxieties about this tendency – to seek these exits from rural destitution, and their consequences for kinship’s moral economy and faith in its purchase upon meaning.

I emphasise that the urban frontier arrived in Ituura at a critical moment in time, when significant numbers of local men had only limited landholdings and low-paying jobs, and thus felt unable to endure peri-urban poverty any longer, seeking instead relief from its vagaries. In Chapter 3, we encounter members of Kiambu’s rural underclass who insist kinship futures are not worth working towards. In part, this feeling was shaped by the struggles of working for low pay. But such men argued it was better to sell land and enjoy the proceeds than support ‘ungrateful’ wives and children who would erase one’s legacy by selling land themselves. This gendered fear of betrayal has its roots in male anxieties about the unknown desires of women who are seen to prefer wealthy ‘sponsors’ rather than poor working husbands (Chapter 5). Against the backdrop of low pay and strained gender relations, working for kin and the future no longer made meaningful sense to such men. Land sale constituted a powerful source of temptation – to escape a life of labour and become ‘rich’. As this book goes on to show, other forms of ‘escape’ appear too. Young women aim to find wealthy husbands that would enable them to transcend their economic status and leave peri-urban neighbourhoods altogether (Chapter 5). We will observe the plight of so-called ‘wasted men’, Kiambu youth who had scorched their futures in favour of heavy drinking (Chapter 2).

In turn, these ‘exits’ served to create a deepening sense of crisis surrounding patrilineal kinship and its vision of the good life – a successful smallholder household provisioned through male-won wages and supported through harmonious gender relations, creating the future in kin. The tensions borne of rural poverty fuelled a sense that patrilineal kinship’s ideal was deeply precarious, liable to destruction by specific transgressions that would ruin the lives of immediate family (Chapter 7). Land sale was the apotheosis of this. To borrow the terms of Nancy Munn (Reference Munn1986), it was recognised amongst Kiambu residents as constituting a radical form of ‘value subversion’. Sales not only undermined patrilineal kinship’s core principles by alienating land from the family. They imagined a completely different relationship between senior men and value, replacing dogged obligation towards future generations with a desire to consume wealth and enjoy the present at the direct expense of the former. It is therefore hardly surprising that stories of land sale presented in this book evoke to the actors themselves a runaway world where social relations have gone awry. Kiambu residents have witnessed for themselves moments in which their neighbours, friends, and possibly their own family have chosen to accumulate and appropriate wealth privately, undermining normative expectation for its distribution.

Readers of Kenya’s history may observe that this description of a failing moral economy of patrilineal kinship recalls aspects of Lonsdale’s (Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992) classic account of the central highlands in the first half of the twentieth century. Under British colonial rule, land expropriation and rural capitalism transformed a political economy of land abundance into one of land scarcity, the introduction of taxes turning younger men out of the house and towards growing towns and cities for wages. These processes fractured what Lonsdale called ‘moral ethnicity’ – the patron–client relations that were integral to inter-generational relations – turning land-poor youth against the elders, out into the forest, and towards the ranks of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, also known as the Mau Mau. ‘Has the moral economy of kinship not already been thoroughly destabilised?’, some readers might therefore wonder. Since describing a notion of ‘moral economy’ that is in a state of distress implies a historical ‘before and after’, further qualification is required.

Lonsdale described central Kenya at a moment when gender and generational relations were being transformed by the privatisation of land for intensive agriculture and the intensification of a cash economy. As farming became profitable after the Second World War (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 405–7), notions of property were strengthened, narrowed around the family ‘clan’ (mbarĩ) as wealthy Kikuyu turned their landless dependents (ahoi) off the land. Meanwhile, inter-generational disputes turned upon the control of labour. Senior men struggled to control younger men who could work for wages in growing towns and cities. Lonsdale’s essay tracked the emergence of a private property ideology, showing how it attacked customary notions of obligation (Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 361). To the extent that Lonsdale described inter-generational tensions focusing on labour, this book comes to a different conclusion through its focus upon land’s status as a family-held good in the aftermath of the land-titling that took place in the 1950s and 1960s (Chapter 1). This has produced an anxious rootedness amongst Kiambu families – where land’s retention constitutes a vital principle, both moral and economic.

What is different about central Kenya today, something Lonsdale’s account does not evoke, is the dire degree of male destitution and the hollowing-out of rural economies that have made land an even more precious an asset, if only to be sold out of distress or the known opportunities of a massive cash injection. If Lonsdale showed how the patron–client relations of moral ethnicity were broken by rural capitalism, this book shows how land’s commodification and the slow-burn legacies of colonial-era expropriation have frayed and fragmented the even narrower moral economy of patrilineal kinship. In a terrain where land sizes have been reduced by such an extreme, where work no longer pays, it shows how fathers are in an advantageous position to appropriate what was thought to be family-held landed wealth on a purely private basis.

The aim of this work is not to inscribe crisis as a feature of such a context, but rather to understand the economic constraints that people face in their attempt to live good lives and the way new opportunities for accumulation tangibly fracture social relations. From a wider perspective, these findings may have consequences for how anthropologists have framed modes of kinship and relationality in Africanist anthropology, often emphasising the efficacy and robustness of ideas and practices of dependence (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2013), mutuality (Haynes Reference Haynes2017), and entrustment (Shipton Reference Shipton2007), which are seen to protect social relations from market logics of possessive individualism and individual accumulation. Such positions have already been critiqued by scholars who have sought to temper such impressions of Africa as a site of alternative economies in light of processes of social and economic stratification which have narrowed interests at the site of the nuclear family, and undermined reciprocity within it (see, e.g., Madulu Reference Madulu1998; Mung’ong’o Reference Mung’ong’o1998; Bryceson Reference Bryceson2002; Seekings Reference Seekings2019; Danielsen Reference Danielsen2021; Lockwood Reference Lockwood2023a). I would argue that the aim of these works has not been to reify or exoticise the ‘dark side of kinship’ (Geschiere Reference Geschiere2003) in a miserablist or pessimistic tonic, but rather to understand the nature of social and economic transformations that undermine these relationalities.

In a similar way, this work does not argue that ideals of kinship have disappeared, nor have their social relations entirely dissolved (Cooper Reference Cooper2012). However, for smallholder families at the sharp end of economic privation, the land market’s effects are lived through a powerful sense of patrilineal kinship’s crisis. The experience of the urban frontier’s approach and the dissolution of kin relations are thus intertwined. Land sale is experienced at the heart of the family as a transgression that undermines not only relationships but the very ideal of a family based upon patrilineal labour and inter-generational distribution. There is therefore a causal aspect to the argument I present. The expansion of the urban frontier is enabled not only by the vulnerabilities of rural poverty – that land sale is triggered by economic distress – but that the very experience of kinship’s collapse further encourages land sale. Land sale is not only producing a deep despondency about patrilineal kinship’s moral economy but is produced by a profound feeling in Kiambu that its future is already deeply uncertain. The consequence of this loss of confidence is a downward spiral towards the complete dislocation of patrilines from the land, evoking the phenomenon of ‘disembedding’ described by Polanyi (Reference Polanyi2001 [1944]) in a quite literal sense. When land is held within patrilines, it is entirely logical that acts of land sale and a loss of faith in kinship could mutually accelerate one another.

Under these conditions, patrilineal kinship’s moral economy is revealed as a fading idea that no longer makes meaningful sense as a way of reading social relations and practice. Witnessing land sale as a violation, young men like Mwaura questioned their fathers’ self-described commitments to kinship’s future. Patrilineal kinship’s moral principles began to look ‘hollow’ in their eyes, an unconvincing narrative rather than a lived commitment, evoking Robert Blunt’s (Reference Blunt2019) description of the way Kenyan conservatives and youth alike have, throughout the country’s political history and in varying ways, ‘lamented’ the erosion of customary norms and moral arrangements. In the context of deepening pauperisation and a loss of faith in patrilineal kinship, the further question this book seeks to answer is how these young men maintained their hopes for a better future, if at all?

A Labour Theory of Virtue

The lowest sediment of the relative surplus population dwells in the sphere of pauperism.

In Kiambu, access to land remains a way of staving off outright proletarianisation, a means of hanging on to the dream of becoming middle class by exploiting it, of somehow staving-off downward mobility and accessing new futures as a rentier. As Mwaura would explain to me in 2022, after his father had sold land: ‘Rental buildings are the real deal. I just hope Kimani doesn’t sell more land.’ As John Lonsdale (Reference Lonsdale2001: 214) once observed, Africa’s history of proletarianization did not play out on the ‘factory floor’ but ‘on ancestral land, within lineages’. It was within the family ‘that people were first separated from their means of production’ (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale2001). By putting kinship and kin-based access to land at the centre of broader conversations about ‘wageless life’, Peasants to Paupers illuminates the emergence of pauperised ‘surplus populations’ from the homesteads of the hinterlands. However, alongside the hollowing-out of kinship’s moral economy, it also explores how young men struggle with their changing economic status and future aspirations amidst Kiambu’s terrain of rural poverty and land sale. It does so by stressing the significance of land for a contemporary literature on ‘wageless life’ (Denning Reference Denning2010) and ‘surplus people’ (Li Reference Li2010) in Africa. Lacking the manufacturing industry that has soaked-up employment across Asia, the African continent finds itself in a particular relation to global capitalism, its liberalised economies growing without any concomitant job creation. Like other African countries, Kenya’s much vaunted ‘youth dividend’ has turned into a crisis of mass unemployment. Kiambu is no exception, but the position of many of my young male interlocutors as landowners or prospective inheritors complicates conventions in the literature that have emphasised urban forms of economic precarity that assume a generalised exposure to economic uncertainty – the need to ‘hustle’ and ‘survive’ (see, e.g., Di Nunzio Reference di Nunzio2019; Thieme et al. Reference Thieme, Ference and Stapele2021; cf. Guma et al. Reference Guma, Mwaura, Njagi and Akallah2023). Neither are they privileged enough to afford to ‘wait’ for better jobs (Mains Reference Mains2012; Masquelier Reference Masquelier2019). That young men in Kiambu are tethered to the land – sometimes precariously so – raises a different set of questions that require the centering of land in discussions about upward and downward social mobility, so too the moral experience of class formation.

In my usage, the concept of class evokes not hard-and-fast categories (e.g., ‘the working class’) but a dynamic process of differentiation, ‘the simultaneous creation of privilege and penury, wealth and poverty, political power and powerlessness’ (Peters Reference Peters2004: 285). My use of the terms ‘proletarianisation’ and ‘pauperisation’ point towards deeper, subterranean political-economic processes that are playing out in Kiambu – that of the subdivision of land that is slowly reducing the capacity to rely on farming as a livelihood or for subsistence. This process has its roots in central Kenya’s history and the expropriation of land to European farmers, which created a land-poor class of ‘workers with patches of land’ (Njonjo Reference Njonjo1981: 37; Chapter 1). By focusing on these ‘deeper’ political-economic processes, I illustrate how the economic ‘ground’, as it were, is shifting right beneath the feet of Kiambu’s young men. While they may possess land in these peri-urban fringes, theirs is a problem of confronting the gradual process of land reduction, and a concomitant forced reliance on cash. Attempts to accumulate savings from work presents its own distinct challenges too – of matching aspirations for middle-class lifestyles with their limited means (Chapter 2). Caught between joblessness and landlessness, the life projects of young men are shown to be afflicted by a palpable sense that the ‘good life’ of middle-class living, that associated with Nairobi and its nouveaux riches, is too distant to seize, prompting a crisis of hopelessness.

I observed this first hand in July 2015, whilst I was a graduate attaché at the British Institute in Eastern Africa. Throughout the month, conservative voices in central Kenya were narrating a crisis of alcoholism that prompted then-President Uhuru Kenyatta to launch his ‘war on killer brews’. Police raided unlicensed breweries and television stations showed servicemen in fatigues pouring alcohol away into the sewers. Newspaper front pages depicted young men lying prostrate in road-side ditches across the region’s towns. In their opinion columns, paternalistic voices described how male youth had been rendered ‘zombie-like’ by ‘illicit liquor’ (Ngwiri Reference Ngwiri2015). Married women complained that men no longer provided money for their children’s school fees, nor food. Others accused their husbands of being unable to fulfil their conjugal duties, publicly emasculating them with stories of impotence. Commentators speculated that the average lifespan in the region had fallen to around forty years of age, driven down by alcohol-related deaths and suicides. In an early foray into the themes that would recur in this book, I spoke to Kikuyu elders gathered in the shade of Jevanjee Gardens in downtown Nairobi, debating their concern. ‘We are talking about alcohol, and how it is ruining the youth’, one explained. ‘They drink so their stomachs are gone, and they cannot have children.’ The words were followed by knowing laughter.

The same month, Gĩkũyũ-language gospel artist Maina wa Njoroge had released a song decrying the effects of such ‘spirits of the wilderness’ (njohi cia ibango), a term that highlighted the uncertain origin of ‘third generation’ drinks, painting a miserable picture of central Kenya’s towns and villages in that dire moment:Footnote 7

In idiomatic Gĩkũyũ, Wa Njoroge’s song told how young men’s once traditional status as proud warriors (anake) had been ruined by alcohol (njohi), while attacking those – the brewers in particular - who had ‘spoiled our tomorrow’ (magĩtũthũkĩria nake rũciũ rwitũ), undermining the vision of a patriarchal household, and the future of the Kikuyu people writ large. Conservative columnists, on the other hand, took it upon themselves to attack the changing moral orientations of the young. ‘Young men are no longer doing any productive work; nor are they siring offspring, for they can rarely rise to the occasion, and even if they did, they have no means of looking after their families’ (Ngwiri Reference Ngwiri2015). The new generation was not conforming to the righteous labour ethic that had won their fathers and grandfathers wealth and public standing.

Wa Njoroge’s was a song of sympathy, and he sang of the lost hopes (mwana witũ akĩaga mwĩhoko wa maica, lit. ‘our child lost the hope of life’) of young men who lacked job opportunities, driven into despair by a cruel existence of working for piecemeal wages in central Kenya’s informal economy as mechanics, tea-pickers, and construction workers. Unable to attain the wealth that would pave the way for their adult success, Wa Njoroge described how they ‘washed their hands of the need for the future’ (akĩyoga moko na akĩaga bata wa rũciũ). Incapable of walking normative pathways towards adulthood, they became hopeless, and the easy availability of alcohol provided a palpable balm for such broken dreams of stable lives in an economy of lack. ‘Not everyone is wicked’, he sang. ‘Some lost hope after being educated but remained jobless.’

Njohi cia ibango evokes the lives of many young male interlocutors in Kiambu, struggling to maintain hope for the future, and trying to avoid the fate of their peers who, they say, have ‘wasted themselves’ through drink. In a broader sense, we can see the lives of these men as having been shaped by the slow process of proletarianisation described earlier. However, to grasp the subjective aspects of their predicament, I frame their struggles as an ethics of endurance, of trying to avoid becoming outright paupers by hanging on to land, middle-class reputation, and hope itself.

Throughout its history, central Kenya’s poor have struggled for reputation. Since before the colonial period, Kikuyu have had a dim view of its ranks. They objectified the proper moral qualities a man ought to possess as wĩathi, a word commonly now translated as ‘freedom’, but at the time connoted ‘self-reliance’ or ‘self-mastery’ – qualities of determination and self-restraint that were cultivated amidst the harsh character of pioneering society (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale, Muoria-Sal, Folke Frederiksen, Lonsdale and Peterson2009). Wealthy men (athamaki) preached the virtue of hard work. The poor, meanwhile, were condemned as lazy in a range of epithets, and belittled as ‘beggars’ (atereki), a word that evoked their silence – a sign of their low standing (Peterson Reference Peterson2004: 11). ‘Poverty shut men’s mouths, making them socially forgettable’ (Peterson Reference Peterson2001: 473; cf. Stephens Reference Stephens2018).

While the effects of colonialism transformed central Kenya into a society of part-time proletarians (Peterson Reference Peterson2001), their working lives were rehabilitated by Christian converts, ‘readers’ (athomi) who had benefited from mission education. Henry Muoria, one such convert and later a speechwriter for Kenyatta, the soon-to-be prime minister of independent Kenya, had done so in his pamphlets penned in the 1940s while he worked as a railway guard. When he condemned poverty amidst the mid-twentieth century’s tumults, he did so not only as a Christian but as a patriot and a paternalist, a man moralising about the values other men ought to have. He did not stress obligation to God nearly as much as obligation to kin, and the moral value of kinship itself.

If you fail to work hard and diligently, you will find nothing but misery, and ignorance and poverty will walk by your side. These are enemies to the people, who [then] become ignorant, poor and useless. What can we do? We must work hard, with much love, to find the resources to educate our children. They will then be in good company, become good, and benefit our country.

Muoria’s words evoked longstanding paternalist discourse about the delinquency of young wage workers. As early as 1912, elders in Kiambu District complained that men returning from work in towns were ‘spoilt’, ‘different men’ who would not ‘bring money to their fathers as before … and think only of themselves’.Footnote 8 According to Chief Wambugu based in Nyeri, ‘The young labourers mostly spent their money before getting home, the older ones brought it back. The younger men spent it on women, beer, and food in Nairobi, they also gambled with the women and houseboys.’Footnote 9 Adult men from Kikuyuland wrote to the vernacular newspaper Muigwithania,Footnote 10 ‘The Reconciler’, edited by Johnstone Kenyatta, exhorting young men and women, labour migrants, to ‘think of tomorrow’, not to fall prey to the ‘delights of Nairobi’.Footnote 11 These were people who appeared to put their desires ahead of their responsibilities and obligations, and conservatives chastised them as such.

Readers like Muoria’s reframed the labour theory of virtue forged on the forest frontier as a more concerted labour ethic for an era of piecemeal cash incomes. Responsible patriarchy was the new barometer of moral personhood. Muoria warned against alcohol, and its effects for a youth who appeared to abandon their responsibilities. ‘They will learn there is a danger in remaining irresponsible – but too late’ (Muoria Reference Muoria, Muoria-Sal, Frederiksen, Lonsdale and Peterson2009 [1945]: 217). Years after independence, Kenyatta would echo Muoria’s paternalism when he asked Bildad Kaggia, the Mau Mau veteran, ‘What have you done for yourself?’ Kaggia was upbraided by Kenyatta because he continued to advocate for land distribution in the aftermath of independence, particularly for former Mau Mau (Maloba Reference Maloba2018: 261). Kenyatta’s rhetoric cast Kaggia’s pursuit of justice as one of dependence, relying on others rather than one’s own efforts. Kenya’s independence and Kenyatta’s leadership marked the victory of a gerontocratic ideal – that wealth was the product of labour. On the forest frontier, the relation between wealth and labour had been visible, but now the labour ethic masked deeper inequalities, moralising structural inequality and poverty as the consequence of indiscipline, of irresponsibility. Kenyatta’s Kenya became an ‘elder state’, one that paternalistically disciplined youth, preaching hard graft as the route towards becoming an upstanding man (Ocobock Reference Ocobock2017: 244, 253; cf. Angelo Reference Angelo2019). The labour ethic of the forest frontier was turned into a labour ideology writ large (Haugerud Reference Haugerud1995: 147), one that displaced questions of redistribution after colonial expropriation with notions of personal responsibility.

In contemporary central Kenya, young men struggle to live up to this ideology of labour’s virtue at the very moment they are rendered surplus to the requirements of capital. With limited land and low-paying jobs, they confront the condition of their own pauperhood, struggling not to become ‘demoralised and ragged’ (Marx Reference Marx1995: 360) and to maintain hope in the future. After all, a prosperous household through which one can hand down one’s names continues to be a barometer of success in contemporary Kenya – and by no means just in Kikuyuland. Its association with ‘middle-’ or ‘working-class’ standards of living and conspicuous consumption make it a dream for the majority of Kenyans. ‘Lazima nipate!’ (Surely I’ll get it!), sings Jaguar, the Kenyan RnB artist on his hit track ‘Huu Mwaka’ (This Year). Set to a music video depicting his rags to riches tale, spanning his youth in the village to his modern, urban lifestyle in a Nairobi apartment alongside his wife and child, Jaguar names all of those things he will ‘get’, or achieve, ‘this year’: ‘Bibi mzuri’ (a good wife), ‘nyumba nzuri’ (a beautiful house), ‘kazi nzuri’ (a good job). Broadcast constantly across the airwaves since its release in 2012, it encapsulates contemporary Kenyan discourses of aspiration that address the home as the ideal site for self-realisation, the creation of abundance, sentiment, and the good life. These successes are not simply individual aspirations as they portrayed to be in the songs. In fact, Jaguar’s use of ‘lazima’ (i.e., ‘it’s a must’) is telling. There is a normative pressure to aspire, pressure to project success.

In Kikuyuland, such desires have a similar inflection in Gĩkũyũ-language gospel songs, but with an even greater focus on the challenges of provision in an economy of cash scarcity. Muigai wa Njoroge, a popular Kikuyu gospel singer whose songs regularly captured hotly debated topics of public morality across central Kenya, famously promised listeners that through economic struggle they would ‘find themselves in the place you’ve always wanted to be’ (wĩkore harĩa wendaga). Railing against the ‘god of poverty’ (thĩina), which man was ‘forced to worship’ against his will, he contrasted such constraint with the wish to ‘live the way I desire’ (nyeturire ũrĩa niĩ nyendaga). Morality was to be found in persistence: in treading the difficult path of making a better future for their children, not least through educating them. These are men singing about the lives they want to give their children, reflecting the historical sedimentation of provider identities that themselves are not simply limited to provision but to self-accomplishment, the satisfaction of provisioning the future.

The recent turn towards ethics in anthropology has made ample theoretical and ethnographic space for describing precisely these types of discourses and life narratives – the extent to which young men in Kiambu see themselves as struggling and striving towards better lives (see, e.g., Zigon Reference Zigon2007; Lambek Reference Lambek2010; Laidlaw Reference Laidlaw2014). Yet, as Ivan Rajković (Reference Rajković2018) has stressed, relatively little attention has been given to the extent to which people acknowledge the material limits on their capacity to achieve. What is more, such material constraints can easily shift across generations as economic circumstances change. Hadas Weiss (Reference Weiss2022) has shown that in rural Spain, narratives of ‘desire’ amongst successful older generations that framed economic life as a self-made endeavour in the 1980s have given way to ones of ‘endurance’ amongst young millennials who struggle to maintain middle-class living standards in the 2010s. The causes of such transformed circumstances were the imposition of austerity policies after the 2008 financial crisis, the growing prevalence of temporary work contracts, and the difficulty of being able to afford housing, created by a booming real-estate market. The effect has been to force mutual reliance within households, as young adults continue to live with their parents, unable to create meaningful economic independence.

In Kiambu, senior men from the generation of part-time proletarians vaunt a theory of free moral agency, arguing for the merits of effort as a means to success. They claim that ethical judgement determines the use of money and resources – an attempt to privilege the value of the future over that of short-term consumption, even when the future (and, I mean here, future prosperity) appears impossible. Theirs is a discourse of free choice, a valorisation of commitment to the future in a world of temptation. Such ideas have been forged in the decades after Kenya’s independence, when working for wages enabled a degree of social mobility. Some of these men found pensionable jobs as teachers or employees. Others benefited from school education. Practically all of them benefited from their access to larger landholdings than their sons.

However, when we turn towards the travails of working men born in the 1980s and 1990s, what we observe is the exhaustion of effort as a viable framework for framing economic life amidst conditions of land poverty and unemployment. These men struggle not to ‘give up’ and revert to frivolous consumption when their wages barely allow them to get by week-upon-week. Such men point towards the unreasonable expectations of women – that their work of breadwinning goes underappreciated – fuelling a feeling of shame and failure (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2024; Chapter 6). Some of these men reproduce their elders’ ‘labour theory of virtue’ – the idea that work can not only lead to success – that effort to accumulate itself constitutes the basic barometer of masculine personhood. They struggle on, under pressing conditions through scrimping and saving – a ‘sacrificing’ of short-term pleasure to purpose low wages towards future projects of housebuilding and marriage. But others openly debate the extent to which striving for low wages in the informal economy cannot forge a meaningful future. As a result, many embrace knowing lives of short-termist consumption, spending what little money they earn on alcohol, becoming what their critics call ‘wasted men’. However, as I intend to show, theirs is not simply an economistic response to poverty, but a reflexive and a knowing one. Their voices explore the limits of the labour ethic as an idea – the limits of striving as a moral possibility, and the conscious acknowledgement of structural constraint. They have, in Rajković’s terms, become thoroughly and, indeed, self-consciously ‘demoralised’. In Kiambu, people spoke of such men as having become ‘frustrated’ or possessing ‘frustrations’ in English, terms that evoke disappointed expectations – of wanting a better standard of living, but being unable to achieve it on low, piecemeal pay.

For younger men, especially millennials in their early to late 20s, creating the future is not framed as a matter of choice but as a capacity to endure the vagaries of the informal economy so as not to ‘give up’. As Weiss (Reference Weiss2022) notes, narratives of endurance become narratives of morality within contexts of economic constraint, redeeming struggles and allowing actors to claim virtue despite curtailed agency. Likewise, young men in central Kenya are less likely to frame their lives in terms of choice, but in terms of struggle and resilience – that they are capable of enduring economic uncertainty, that they are ‘bold’ in the face of destitution, that they deliberately avoid peers who have become ‘wasted’ by alcohol. These are discursive claims about their moral personhood, but the language of constraint recognises the genuine material limitations placed on their economic lives in an ethics of endurance that belongs to their status as youth on the margin of landlessness. Pointing towards their peers who have ‘wasted themselves’, young Kiambu men recognise that moral tropes of working for success are being exhausted by the immense challenges of pursuing middle-class ‘stability’ in the informal economy, enforcing not only ‘hanging on’ but also ‘giving up’. Within this context, avoiding this loss of hope becomes a critical pursuit in its own right, a triumph against poverty and the slippery slope towards destitution.

By the end of my fieldwork in 2022, and the close of this book, I show how my interlocutors increasingly questioned and fell afoul of the labour theory of virtue, struggling to find work and a reason to purpose wages towards living costs rather than alcohol. From this perspective, what Kiambu elders sometimes refer to as moral dysfunction amongst their youth – a lack of effort and perseverance – begins to look like a rational response to a world of few options. As Pierre Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu2000: 221) once argued, this apparent ‘dysfunction’ conservatives identify in the lives of the poor is itself a calculated response to a world of limited life chances. If ‘capital in its various forms is a set of pre-emptive rights over the future’ (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2000: 225), what looks like delinquency – especially to those in situ – is a logical response to crushed aspirations. The question arises quite explicitly for these men – at what point will their hopes ‘run out of road’, as it were? To what degree can they maintain their belief in work as a means to a better future? By this book’s conclusion we will see that while some of my interlocutors were able to hold firm to hope, others had practically ‘given up’ on the future, with varying degrees of consequence.

A Neighbourhood Ethnography: Methodological and Conceptual Notes on Gender, Aspiration, Secrecy, and Distinction

Though Mwaura’s fortunes over these years of fieldwork bookend this work, they are hardly the sole focus of what has been a long and sometimes painful experience of research. The deaths of friends due to alcohol and suicide marked the end of my fieldwork, and being closely aware of the deepening destitution of Mwaura’s family and his own depression left me struggling to find in this fieldwork the basis for a scholarly work. What is written here has been a struggle of writing, a search for coherence, and an unfinished attempt to find a way between analysis and witnessing, a desire to understand the broader social and economic context in which these diminished horizons for futures play out. When analysing one’s data, multiple options are open, options that some might suggest reflect the politics and morality of authors over and above the evidence of fieldwork. I found little solace in trying to argue for Mwaura’s resilience to his looming poverty on a purely ethnographic footing. As time has passed, I found greater value in seeking to understand the broader terms of the political economy and how Mwaura and his peers live within that setting. I became interested in the regional history of gradual proletarianisation and trying to situate struggles for good lives within that history. The transformations of my analytical approach reflect shifts in my data (contrast with Lockwood Reference Lockwood2020a), focusing upon the fortunes of my friends and interlocutors as they shifted over the years since 2019.