Introduction

Generational turnout decline – the growing proportion of successive cohorts developing lasting habits of non‐voting – poses a risk to the health of many Western democracies. Since the 1970s, young people throughout Europe and America have become increasingly unlikely to vote upon reaching adulthood, and the habitual nature of electoral participation means they are likely to remain lifelong non‐voters (Franklin, Reference Franklin2004; Garcia‐Albacete, Reference Garcia‐Albacete2014; Grasso, Reference Grasso2016; Plutzer, Reference Plutzer2002; Wattenberg, Reference Wattenberg2012). Not only are a growing number of young people under‐represented in public debate and decision‐making, therefore, but policymaking has become less responsive to public needs (Whiteley, Reference Whiteley2012), and if the trend continues, questions about the legitimacy of democratic decisions may arise. This decline, moreover, is driven primarily by those from poorer backgrounds and who are unlikely to enter higher education (Flanagan et al., Reference Flanagan, Bowes, Jonsson, Csapo and Sheblanova1998; Garcia‐Albacete, Reference Garcia‐Albacete2014; Sloam et al., Reference Sloam, Kisby, Henn and Oldfield2021), meaning that elections are also increasingly decided by smaller and socio‐economically better‐off sections of society (Garcia‐Albacete, Reference Garcia‐Albacete2014).

Concern about this trend has spurred interest in measures that could increase the turnout of newly eligible voters (attainers) and help instill lasting voting habits, such as lowering the voting age or political education (McAllister et al., Reference McAllister, Campbell, Childs, Clements, Farrell, Renwick and Silk2017; Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016). While concern about young people's community participation (beyond elections) has renewed interest in policies promoting volunteering (Kim & Morgul, Reference Kim and Morgul2017), such policies have been largely absent from debates about falling turnout. Nonetheless, an extensive literature suggests that promoting childhood volunteering can increase adult turnout because of its positive impact on social capital, civic skills and political engagement (e.g., Hanks, Reference Hanks1981; MacFarland & Thomas Reference MacFarland and Thomas2006; Roker et al., Reference Roker, Player and Coleman1999; Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2008).

Such conclusions are questioned, however, by the tendency of (particularly older) studies to operationalise ‘volunteering’ as membership of community associations and the limited use of panel data (Kim & Morgul, Reference Kim and Morgul2017; Marta & Pozzi, Reference Marta and Pozzi2008; Wilson & Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick2000). Moreover, previous research has routinely failed to control for confounding characteristics that could explain both the tendency to volunteer in childhood and vote in adulthood and selection effects in which those who vote are likely to have volunteered (Kim & Morgul, Reference Kim and Morgul2017; MacFarland & Thomas, Reference MacFarland and Thomas2006; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Mantovan and Sauer2020). Finally, no previous research has studied the influence of political socialisation on the relationship between childhood volunteering (as opposed to membership of voluntary associations) and voting. While the potential for such influence has long been known (Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968; MacFarland & Thomas, Reference MacFarland and Thomas2006), compelling empirical evidence for it to apply to measures to increase youth turnout comes primarily from studies of political education. These increasingly show that the effects of political education are greater among children not socialised into being politically engaged by their parents (Campbell, Reference Campbell2008; Hooghe & Dassonneville, Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2011; Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016). The correlation between political engagement and socio‐economic status also means that such children are frequently from poorer households and at the forefront of generational turnout decline (Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). While on average the effects of childhood volunteering on voting may be limited, therefore, there is a possibility that it has a greater effect on children from politically disengaged households.

The objective of this study is to analyse the impact of childhood volunteering on attainer turnout while accounting for confounders and selection effects more effectively than previous research, and the potential for that impact to vary depending on previous political socialisation. Using the United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Study, it first examines how volunteering in childhood is related to the turnout of attainers in the 2015, 2017 and 2019 U.K. general elections, removing the potential for selection effects by focusing on respondents who could not possibly have voted before. Second, it controls for childhood political engagement as a proxy for confounding traits that could predispose respondents to both volunteer in childhood and vote in adulthood. Third, it examines how the volunteer effect is moderated by respondents’ parents’ political engagement.

The study shows that, on average, childhood volunteering has little impact on attainer turnout, because most children who volunteer are likely to vote in adulthood regardless: that they volunteer as children and vote as adults reflect their being socialised into being politically and civically active and their possession of resources that facilitate civic and political participation. There is a significant benefit, however, for the children of politically disengaged parents, who would otherwise be unlikely to vote because they are unlikely to become politically engaged through primary socialisation. Volunteering exposes them to political issues and institutions in their community, as well as other more politically engaged individuals, and increases their attachment to that community and social norms that encourage political participation. This leads to increased interest in politics and a greater propensity to view voting as a civic duty, both of which result in a higher likelihood of voting.

The article proceeds by first outlining the impressionable years theory of political socialisation, which not only justifies the focus of this research on young people but explains why childhood volunteering has the potential to affect adult voting, and then details theories on how volunteering affects political participation. The limitations of existing research and the theoretical case for childhood volunteering to have a greater effect on children from politically disengaged households are then outlined before the research design and results are presented. The conclusion argues that childhood volunteering has the potential to help reverse generational turnout decline, discusses limitations and identifies avenues for further research.

Literature review

Political socialisation and the formative years

Many forms of political and civic engagement – including voting and volunteering – are habitual: those who develop habits of doing so (or not) while young are likely to continue throughout adulthood (Franklin, Reference Franklin2004; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968; Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009). Key for the development of such habits is the ‘formative years’: the period during childhood and early adolescence in which people start to independently engage with politics and are exposed to stimuli that encourage them to develop opinions, attitudes, values and behavioural responses (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009). When young people first encounter a political issue – such as seeing information about a war on the news or an election taking place – they seek information and cues from external sources (socialising agents) to guide their response, and such cues form the bedrock of the political attitudes and values they develop (Hyman, Reference Hyman1959; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968). The most influential socialising agents are parents, whose influence can stem from the cues given in family life (e.g., discussing politics at home) or the association between parents’ access to socio‐economic resources that facilitate political participation and the likely access of their children (Dinas, Reference Dinas2013; Hyman, Reference Hyman1959; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968). So strong can the influence of parents be that congruence (or at least strong similarity) in political traits between parents and children is common in terms of political partisanship, engagement, behaviour and ideology (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Hampton, Muddiman and Taylor2019; Hyman, Reference Hyman1959; Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968; Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009). Through consistent exposure to cues and repeated expression, the attitudes, values and behaviours people start to develop during the formative years ‘crystallise’ and become lasting characteristics (Dinas, Reference Dinas2013).

The principal cause of falling turnout in Western democracies is new cohorts of citizens increasingly developing habits of non‐voting during their formative years (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil, Nevitte and Nadeau2004; Franklin, Reference Franklin2004; Wattenberg, Reference Wattenberg2012). Numerous factors contribute to this, including the protraction of the ‘youth’ stage of the life cycle, increasing economic precarity, changing patterns of media consumption and weakening attachments to political and social institutions (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil, Nevitte and Nadeau2004; Grasso, Reference Grasso2016; Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Smets, Reference Smets2016; Wattenberg, Reference Wattenberg2012). These have led to falling political interest, a lower likelihood of being mobilised to participate in politics and a declining belief that voting is a civic duty, all of which make young people less likely to vote and frustrate the development of voting habits. Moreover, the processes underpinning turnout decline have either affected those from the poorest backgrounds most or compounded pre‐existing obstacles to political participation they already faced (Flanagan et al., Reference Flanagan, Bowes, Jonsson, Csapo and Sheblanova1998; Martin, Reference Martin2012; Sloam et al., Reference Sloam, Kisby, Henn and Oldfield2021), meaning the growing propensity of attainers not to vote is concentrated amongst those of lower socio‐economic status (Garcia‐Albacete, Reference Garcia‐Albacete2014).

Civic voluntarism and the limitations of current research

The case for childhood volunteering being able to increase attainer turnout is summarised in Verba et al's (Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995) civic voluntarism theory. This views volunteering as one of numerous civic activities that help foster resources, values and behavioural habits that facilitate political participation. These include social capital: the consequence of social networks that can be utilised to achieve individual or collective goals and reduce the costs of collective action (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Van Oorschot et al., Reference Van Oorschot, Arts and Gelissen2006). More extensive social networks and closer bonds between people facilitate political participation by making it easier to access political information, gather support for political campaigns and feel more able to influence political outcomes, that is, they increase political awareness, knowledge and efficacy. They also make people more likely to be exposed and receptive to social norms, such as the belief that voting is a civic duty, which also encourages turnout (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Whiteley, Reference Whiteley2012).

Skills developed through volunteering that can be transferred to the political arena – such as leadership, teamwork, personal organisation, fund‐raising, research or communication – are also important (Flanagan et al., Reference Flanagan, Bowes, Jonsson, Csapo and Sheblanova1998; Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2008; Roker et al., Reference Roker, Player and Coleman1999; Wilson, Reference Wilson2000). These can be applied to help people participate in a range of political activities, such as lobbying, campaigning, protesting or voting. Volunteering is also argued to increase the motivation to participate in politics because it brings individuals into contact with social and political issues that could spur them to action (Roker et al., Reference Roker, Player and Coleman1999; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Someone who helps run a food bank, for example, may become more aware of poverty and motivated to do something about it, which could lead them to (among other things) vote. Finally, greater knowledge of community issues can lead to greater knowledge of local politics, which in turn improves confidence in the understanding of the political process and how to influence it (i.e., political efficacy), thereby increasing participation (Flanagan et al., Reference Flanagan, Bowes, Jonsson, Csapo and Sheblanova1998; Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2008).

There is a clear theoretical potential, therefore, for volunteering during the formative years to foster the development of skills, resources, knowledge, awareness and values that promote political participation in adulthood. Data limitations, however, have thus far undermined convincing demonstrations of this potential. Few surveys collect data on both childhood/adolescent volunteering and voting in adulthood (an obvious prerequisite to studying the relationship between them), and fewer still collect panel data with such information. The limited use of panel data has frustrated attempts to control for confounding characteristics related to both childhood volunteering and voting in adulthood, which is particularly problematic considering the numerous potential confounders, including political interest, socio‐economic status or familial characteristics (Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010; Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009; Kim & Morgul, Reference Kim and Morgul2017; Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016; Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Feiring and Lewis1998). The lack of panel data also makes accounting for selection effects – in which those likely to vote in adulthood are also likely to volunteer in childhood – more difficult. Kim and Morgul (Reference Kim and Morgul2017), for example, used US‐based panel data to examine the link between childhood volunteering and voting and found that once family context (such as socio‐economic status) was accounted for, there was no substantial link. Similarly, Van der Meer and Van Ingen (Reference Van der Meer and Van Ingen2009) argued that the theorised link between civic and political participation reflects the tendency of those who are politically active to be civically active as well (i.e., a selection effect). While some United States–focused studies have used panel data to argue that childhood volunteering increases turnout (Hanks, Reference Hanks1981; MacFarland & Thomas 2006), they employed measures of volunteering based on associational membership: an increasingly rare civic activity, particularly among young people, and one that would not capture instances of volunteering beyond institutional settings (Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Fox, Evans and Rees2019).

Parental socialisation and the potential for variable volunteer effects

No previous study of childhood volunteering has considered the potential for any effect to vary depending on prior political socialisation. The potential for such an effect is rooted in the impressionable years theory outlined above: a child's response to a political stimulus will be conditioned by previous experiences and the cues provided by socialising agents (principally parents). A child with lots of cues and experience will already have a foundation of political characteristics through which the stimulus is interpreted and responded to; a child who has received few cues will have no such foundation and so may respond differently (or not at all) (Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968; Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009; Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016). Studies of political education provide evidence of this potential in showing that the effects are greater for those raised by politically disengaged parents, and so who are likely to have received few cues or experienced few political events thus far in their political socialisation (Campbell, Reference Campbell2008; Hooghe & Dassonneville, Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2011; Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016; Weinschenk & Dawes, Reference Weinschenk and Dawes2021). For such children, political education can be the first source of cues and information that encourage the formation of political attitudes and values, as well as shape behavioural responses, that can underpin the development of habits of political participation in adulthood (Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016). The correlation between limited political engagement and socio‐economic status means that the beneficiaries of political education are also likely to be those from poorer backgrounds (Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995).

Most children who volunteer are from wealthier backgrounds and are likely to be raised by politically engaged parents (Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010; Kim & Morgul, Reference Kim and Morgul2017; Wilson, Reference Wilson2000). If the relationship between socialisation and political education is replicated for volunteering, there is a potentially substantial benefit for volunteering – through the mechanisms outlined above – to increase the turnout of those raised by politically disengaged parents. Like political education, volunteering could be a rare opportunity for such children to be exposed to political issues and stimuli in their community, to meet others who are politically engaged, and to develop civic skills and values that will facilitate their participation in politics.

Hypotheses

The objectives of this study are first to determine whether attainers become more likely to vote if they volunteered during childhood after confounding variables and selection effects have been controlled for. The first hypothesis, therefore, is:

H1: Childhood volunteering makes attainers more likely to vote.

Several sub‐hypotheses can also be tested that represent the mechanisms through which childhood volunteering is expected to affect turnout (see above): increased interest in politics and political issues; greater confidence in one's understanding of politics and the political process; and a greater likelihood of believing one has a civic obligation to vote. This gives us three sub‐hypotheses:

H1a: Volunteering increases attainers’ interest in politics.

H1b: Volunteering increases attainers’ feelings of political efficacy.

H1c: Volunteering increases attainers’ belief that voting is a duty.

The second hypothesis relates to the potential for childhood volunteering to have a different impact depending on socialisation experience. There are many influences that could affect the development of political characteristics during the formative years; however, an effective proxy for how likely political socialisation is to encourage the development of habits of political participation is parents’ political interest, since it directly measures their psychological interaction with politics and is closely correlated with political participation (Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968; Reference Jennings and Niemi1981; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Parents are primary socialising agents, having the greatest influence over the development of their child's political characteristics and often present when they encounter their first political stimuli (Jennings & Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1968; Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009). Children of politically active and engaged parents are more likely to be exposed to political stimuli and cues that promote political engagement than those of politically disengaged parents. The second hypothesis, therefore, is:

H2: Childhood volunteering will have a stronger effect on the interest/efficacy/duty of children of politically disengaged parents.

Research design

Data

This study uses data from the U.K. Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS)Footnote 1: a large, representative panel survey of U.K. households. There are no cross‐national panel studies including data on volunteering and political participation, forcing reliance on single‐country studies. UK‐based findings are at least suggestive of likely relationships in other Western democracies, however, because trends in youth political participation, including turnout and characteristics related to it (such as political interest) are similar throughout Europe and North America (Fieldhouse et al Reference Fieldhouse, Green, Evans, Mellon, Prosser, Schmitt and van der Ejik2020; Dalton, Reference Dalton2013; Garcia‐Albacete, Reference Garcia‐Albacete2014; Martin, Reference Martin2012; Wattenberg, Reference Wattenberg2012), as are trends in volunteering and its relationships with political participation (Wilson, Reference Wilson2000; Wilson & Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick2000). The United Kingdom is a somewhat extreme case when it comes to low youth participation: youth turnout is particularly low, and young people in the United Kingdom are less likely than many European counterparts to view voting as a civic duty, report being interested in politics or follow political news (Grasso, Reference Grasso2016; Martin, Reference Martin2012; Wattenberg, Reference Wattenberg2012). The cause of this distinction is unclear, though some have pointed to the U.K. party system or greater socio‐economic inequality (Grasso, Reference Grasso2016; Sloam, Reference Sloam2014). Whatever the cause, the United Kingdom is a severe example of a national context in which youth political participation (particularly among those from poorer backgrounds) is low, making it a good case in which to identify and test theories relating to that trend. In addition, previous research gives no grounds to suggest that either the unusually low levels of youth participation in the United Kingdom, or potential explanations for it, should affect the relationship between volunteering and political engagement or turnout; indeed, much of the literature studying these relationships cited above draws on data from the United Kingdom.

Method and sample

The analyses were conducted using structural equation modelling (SEM): a statistical technique allowing complex causal theories to be tested based on adherence of a theorised model to observed relationships in a dataset, as well as complex constructs (such as civic duty) to be operationalised through measurement models that provide greater reliability and statistical variance than single variables (Carmichael & Brulle, Reference Carmichael and Brulle2016; Kelloway, Reference Kelloway1995). The key advantage of SEM is that, in contrast with regression analysis which “assumes that all independent variables have a direct influence on the explanatory variable” (Carmichael & Brulle Reference Carmichael and Brulle2016, p. 7), it can simultaneously estimate multiple direct and indirect effects in a causal relationship (Kelloway, Reference Kelloway1995). Moreover, most software packages allow ‘grouping’ in which separate models are estimated for sub‐samples that can be directly compared and the significance of differences calculated (Hooper et al., Reference Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen2008). While both SEM‐ and regression‐based analyses could test the hypotheses above, therefore, SEM allows for the numerous direct and indirect effects in those hypotheses to be modelled and tested more parsimoniously than regression techniques.

The UKHLS sample was limited to attainers in the 2015, 2017 and 2019 general elections for whom there were no missing observations on all variables (described below). This covers all the general elections available within the UKHLS dataset for which data on volunteering from preceding waves is also available and focusing on attainers accounts for potential selection effects arising from reverse causation (in which voting may encourage volunteering) or the self‐sustaining nature of voting. This produced a sample of 693 newly eligible voters in the 2015, 2017 or 2019 elections. Biases in survey non‐response meant that the sample was not representative of attainers in those elections; however, its characteristics were similar to those of all newly eligible voters for those elections in UKHLS (see online Appendix A).

Variable information

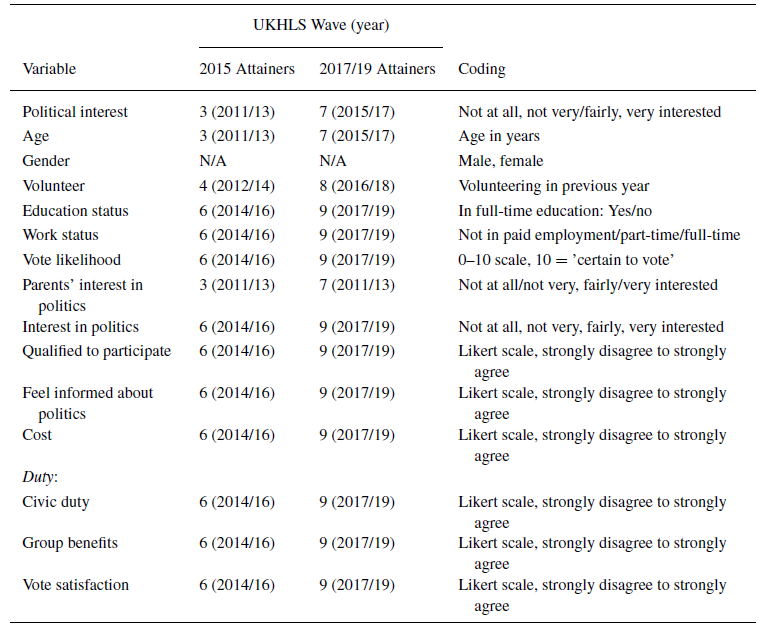

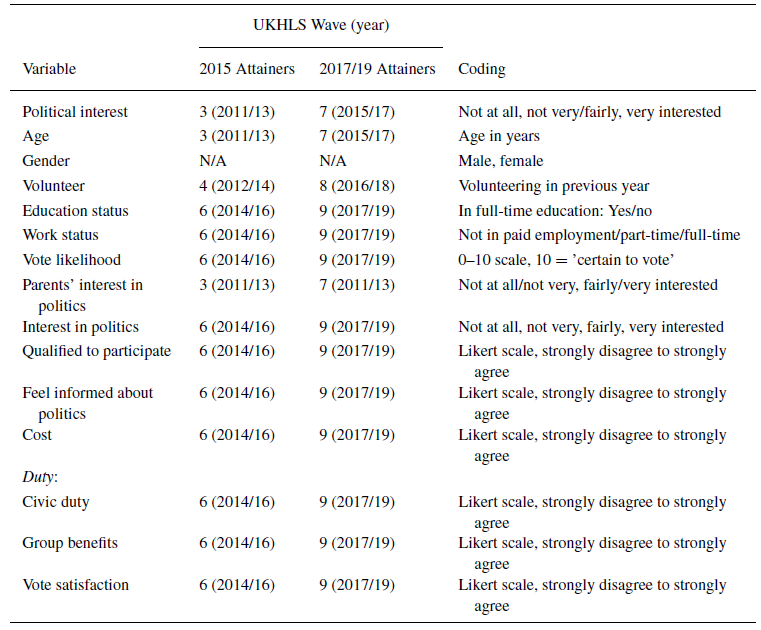

Table 1 lists the variables used, as well as their coding and the UKHLS wave in which they were measured.Footnote 2 While the variables were measured in different waves depending on whether the respondent was a 2015, 2017 or 2019 attainer, the data were recoded into a pooled variable covering all three groups of attainers.Footnote 3 For the 2015 attainers, data were used from Wave 3 (when respondents were aged 15–19), Wave 4 (16–20) and Wave 6 (18–22). For the 2017 and 2019 attainers, the data came from Wave 7 (when they were 16–18 and 16–17, respectively), Wave 8 (17–19 and 17–18) and Wave 9 (18–20 and 17–19). Data limitations meant that for the 2015 attainers, volunteering was measured 2 years before their vote likelihood was measured, while the gap was only one year for the 2017/19 attainers. This should not have a substantial impact on the validity of the analyses: any volunteer effect may ‘wane’ the longer the wait before an election, but this would simply result in the effect estimated in this research being weaker, meaning that the analysis below may produce a conservative estimate of the volunteer effect for the 2015 attainers.

Table 1. Variable information

Note: The table shows that the variables representing the mediators were measured in the same UKHLS wave as the dependent variable. It would have been preferable to use data from waves in between the measure of volunteering and vote likelihood, but this was not available. The theory that political interest, efficacy and civic duty are causally prior to voting, however, is extensively supported elsewhere (Blais and Achen 2019; Smets and van Ham 2013).

The dependent variable was respondents’ self‐reported vote likelihood in the 2015/17/19 general elections. Survey respondents’ tendency to exaggerate their expected likelihood of voting (Pattie et al., Reference Pattie, Seyd and Whiteley2004) makes this a less reliable measure of turnout than recalled vote; however, existing software packages for SEM cannot accommodate binary dependent variables without a substantial loss of functionality, including the capacity to produce model fit statistics. As no previous research has developed an SEM for studying the relationship between childhood volunteering and adult voting, being able to assess the fit of proposed models is vital. The tendency to exaggerate turnout is concentrated among those expected to be more likely to vote (i.e., those from wealthier households, with more education etc.), meaning this bias is likely to be more prevalent in analyses of respondents from politically engaged (and more likely to be wealthy and educated etc.) parents (Belli et al., Reference Belli, Traugott and Beckmann2001; Karp & Brockington, Reference Karp and Brockington2005). This may affect estimates of the volunteer effect for this group, as well as comparisons between the groups, but should have less of an impact on those estimates for respondents from disengaged households. There is no way of detecting or compensating for this bias; however, it is possible to assess the robustness of the results by analysing the effect of volunteering on the recalled vote (without accounting for the mediator or indirect effects) in a logistic regression analysis. The results of this are presented in online Appendix E.

Volunteering was measured on an ordinal scale, indicating whether in the previous year respondents had ‘never/almost never volunteered’, ‘infrequently volunteered’, ‘volunteered at least several times a year’ or ‘volunteered at least once a week’. The key control variable was respondents’ interest in politics in childhood prior to the measure of volunteering. This controls for confounding effects stemming from a pre‐existing civic and political engagement that predisposes people to volunteer in childhood and vote in adulthood. While there are many sources of pre‐existing civic and political engagement, they are expected to result in a higher level of childhood political interest, making this a suitable control ( Blais & Achen, Reference Blais and Achen2019; Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil, Nevitte and Nadeau2004; Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995).

As H1a, H1b and H1c outline, the effect of volunteering is expected to be mediated by political interest, efficacy and the belief that voting is a duty. Political interest was measured by self‐reported interest in politics, while efficacy was measured using three variables capturing whether respondents felt qualified to participate in politics, informed about politics or that political engagement was too costly. The belief that voting is a duty was represented by a measurement model: three variables in UKHLS were identified as potential indicators and the theory that they represented a common latent trait was tested using Mokken Scale Analysis (MSA). Variables representing civic duty, respondents’ satisfaction from voting and perception that voting could bring benefits to groups in need, were shown as representing a common trait: the scale H‐coefficient was 0.47, well above the threshold value of 0.3 (full output is provided in online Appendix C).Footnote 4

Several further controls were included to account for characteristics related to childhood volunteering, voting or both:

Gender, as boys tend to be more politically interested than girls, while girls are more likely to volunteer (Fraile & Sanchez‐Vitores, Reference Fraile and Sanchez‐Vitores2019; Gaby, Reference Gaby2017).

Age, because the positive effect of age on political engagement is identifiable even among young children (Van Deth et al., Reference Van Deth, Abendschon and Vollmar2011) and because of differences in opportunities to volunteer based on age (e.g., under‐16s are ineligible for National Citizen Service in the United Kingdom).

Education and work status, reflecting the influence of being in full‐time education and/or a workplace on political engagement and participation (Sloam et al., Reference Sloam, Kisby, Henn and Oldfield2021; Smets, Reference Smets2016).

Finally, to test H2, data on respondents’ parents’ political interest in the UKHLS wave prior to that in which their volunteering was measured (i.e., Wave 3 for 2015 attainers and 7 for 2017/19 attainers) was used to group respondents depending on whether they came from a politically disengaged or engaged household. A politically disengaged household was defined as one in which both parents reported being ‘not at all’ or ‘not very’ interested in politics. Children raised in such households were expected to have received few stimuli to engage with politics during primary socialisation. An engaged household included at least one parent who reported being ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ interested in politics. Of the 693 respondents in the sample, most (475, 69 per cent) had at least one parent who reported being ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ interested in politics.Footnote 5

Theoretical model

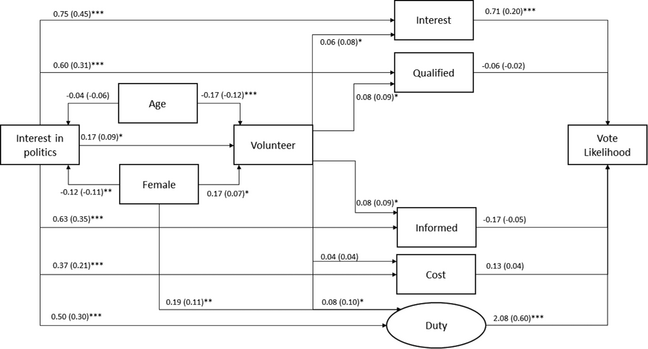

Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical model summarising how these variables were expected to be related, upon which the development of the SEM was based. Rectangles represent observed variables (e.g., Volunteer) and circles represent latent variables operationalised by measurement models (e.g., Duty). One‐headed arrows (‘directional effects’) indicate a theorised causal relationship in which a change in the variable at the beginning of the arrow is theorised to produce a change in the variable on the end of it.

Figure 1. Theoretical Model.

As set out in H1, childhood volunteering was expected to affect vote likelihood through its impact on interest in politics (Interest), political efficacy (Qualified, Informed, Cost) and perception that voting is a duty (Duty). No direct effect from volunteering to vote likelihood was anticipated, as the effect of volunteering was expected to be fully captured through its impact on the moderators (this was tested and confirmed during model development – see below). The key control of childhood political interest was expected to affect respondents’ likelihood of volunteering directly, as well as their vote likelihood in adulthood through its impact on the moderators (the potential for a direct effect to vote likelihood in addition to these indirect effects was also tested). Both volunteering and childhood political interest were also expected to be affected by age and gender (see above). The SEM did not control for election year as it assumes that the relationships will be similar for all three groups of attainers and not affected by the context of a specific election (this assumption was tested and confirmed during model development, see below).

For the sake of parsimony and presentation, Figure 1 does not include the following which were included in the SEM:

The education status and work status variables, from which directional effects were modelled to Interest, Qualified, Informed, Cost and Duty.

Non‐directional effects (covariances between variables not expected to be causally related) between Interest, Qualified, Informed, Cost and Duty, as well as education and work status.

The effects in the Duty measurement model.

The data relating to these variables and effects are available in the tabular outputs from the SEM, which is reported in online Appendix D.

Finally, to test H2, the sample was divided into two sub‐groups depending on respondents’ parents’ interest in politics – those from a disengaged household and those from an engaged household – and the SEM run for each so that the effects of volunteering could be compared. The significance of those differences was assessed using Wald tests, and likelihood ratio tests were used to determine whether allowing the volunteer effects to vary between the two groups produced any significant improvement in model fit (Van der Eijk et al., Reference Van der Eijk, Franklin, Demant and van der Brug2007; Hooper et al., Reference Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen2008).

Results

Descriptive statistics

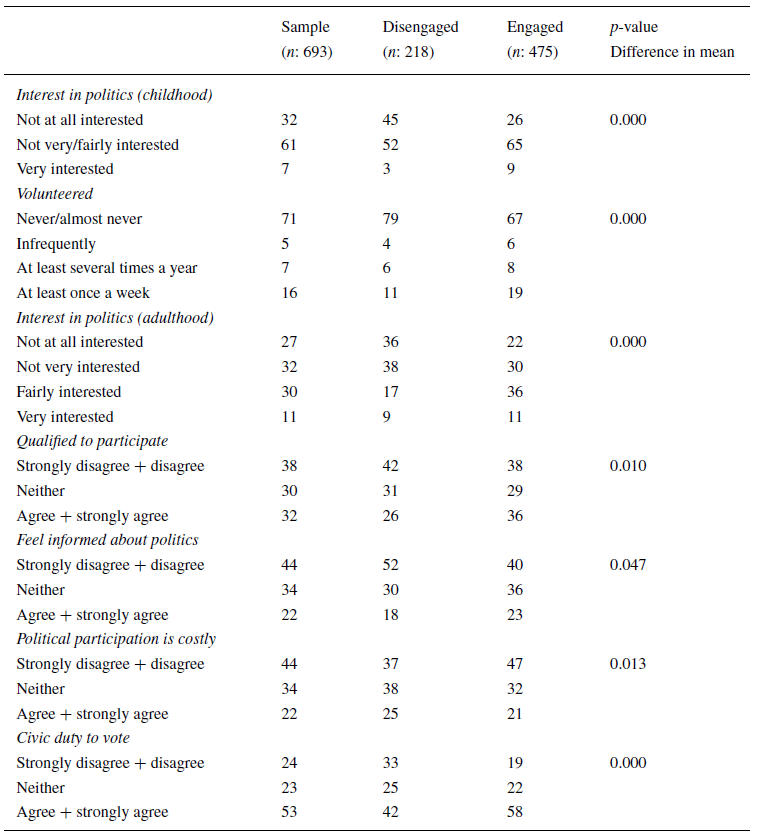

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics about the volunteering and political engagement of the sample and shows how they were related to the engagement of respondents’ parents. During their teen years, most had at least some interest in politics and only a third had none. Almost three‐quarters had never or almost never volunteered a year later, while 16 per cent did so at least once a week. By the time of their first election overall political engagement had increased, with the proportion of attainers saying they had no interest in politics falling to a quarter and a similar proportion rejecting the view that voting was a duty.

Table 2. Sample information (%)

Source: UKHLS.

There were clear differences (confirmed as significant using t‐tests) depending on respondents’ parents’ political engagement, with those from disengaged households less engaged and less likely to volunteer: 45 per cent had no political interest in childhood, and by the time of their first election this was still the case for 36 per cent while 33 per cent did not feel that voting was a duty; almost four fifths did not volunteer. Among the children of engaged parents, only 26 per cent had no interest in politics in childhood, and by the time of their first election this was 22 per cent, with 19 per cent not seeing voting as a duty. Almost a third reported volunteering.

Finally, the descriptive data also show evidence of a positive, though weak, effect from volunteering on turnout and political engagement. Of those who did not volunteer, 10 per cent were ‘certain not to vote’ in their first election and 46 per cent were ‘certain to vote’; of those who volunteered at least once a week, the figures were 5 per cent and 61 per cent respectively. Similarly, of those who did not volunteer, 28 per cent had no interest in politics by their first election, and 28 per cent disagreed voting was a duty. Among those who volunteered at least once a week, the figures were 20 and 24 per cent respectively (the differences were statistically significant).

SEM results 1: Model development

Before H1 and H2 could be tested using SEM, an appropriate model must be developed. Unless a SEM is defined in previous research (which is not the case here), this involves a process of testing, modifying and re‐testing until a suitable model is identified. This is a difficult process as there are often several SEMs that fit data equally well, and a risk of capitalisation on chance when analysts use a model they developed to test their hypotheses (Chin, Reference Chin1998; Hooper et al., Reference Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen2008). To mitigate these issues, model fit was assessed by theory, parsimony and effect interpretation alongside fit statistics (Chin, Reference Chin1998). In addition, a ‘cross‐validation approach’ was used, in which the sample was randomly divided in half and the model developed and refined on the ‘development sample’, then tested on the ‘test sample’ (Jöreskog & Sörbom, Reference Jöreskog and Sörbom1996).Footnote 6 The hypotheses were then tested on the developed model using the full sample.

The development process is detailed in online Appendix C, whereby the model illustrated in Figure 1 was fitted to the UKHLS sample and refined. The model was very similar to theoretical expectations, with the only modification being the addition of a directional effect from Gender to Duty indicating that females were more likely to feel voting is a duty than males. That this was significant alongside the effect of Gender on childhood interest is evidence of gender gaps in political engagement being driven by processes in adolescence that are independent of, and in addition to, those in early childhood (Fraile & Sanchez‐Vitores, Reference Fraile and Sanchez‐Vitores2019). The tests of whether directional effects should be added between volunteering and vote likelihood, and childhood political interest and vote likelihood, showed that neither was significant. In addition, during the model development stage, additional (unreported but available on request) analyses were run to confirm that there were no substantial differences in volunteer effect across the three elections (and that, therefore, the decision to pool variables did not obscure heterogeneity in relationships between variables).

SEM results 2: Hypothesis testing

Figure 2 summarises the results of the SEM (full output is provided in online Appendix D). The numbers next to the directional effects are unstandardised coefficients, which are interpreted in the same way as those for ordinary least squares regression. The figures in brackets are standardised coefficients, which range from 0 to 1 and can be used to compare effect sizes where variable scales vary. Standardised coefficients below 0.1 indicate negligible effects; between 0.1 and 0.2 indicate weak effects, between 0.2 and 0.4 moderate effects, and above 0.5 strong effects (Chin, Reference Chin1998). The model shows that for a one unit increase in the scale measuring Duty, for example, average vote likelihood increased 2.08 points; the standardised coefficient of 0.60 shows that this is a strong effect compared with others in the model, three times as strong as the effect of political interest.

Figure 2. SEM of volunteering and turnout in U.K. attainers.

Source: UKHLS. Obs: 693. *effect statistically significant at 95% confidence level; **99% confidence; ***99.9% confidence. Model fit statistics: Root Mean Squared Error of Estimation (RMSEA) = 0.043 [0.032–0.055]; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.97; Standard Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR): 0.038. The interpretation of fit statistics is discussed in online Appendix C.

The analysis offers only weak support to H1. While political interest and Duty both had strong and significant effects on vote likelihood, volunteering had a very weak, positive effect on Duty (standardised coefficient of 0.1) and a negligible effect on political interest (0.08). It also had a negligible effect on feeling qualified and informed enough to participate in politics, neither of which was significantly related to vote likelihood. Far more important as a determinant of turnout was childhood political interest: this was moderately and significantly related to Interest (0.45), Qualified (0.31), Informed (0.35), Cost (0.21) and Duty (0.30). It also had a significant, though weak, effect on whether respondents volunteered (0.09). Once the confounding influence of pre‐existing political engagement is accounted for, therefore, there is little to suggest that children who volunteer become more likely to vote.

The effects of the other control variables were mostly as expected: older children were shown to be slightly less likely to volunteer, though there was no significant effect on childhood political interest. Females were (marginally) more likely to volunteer than males and less likely to be politically interested in childhood, while in adulthood they were more likely to see voting as a duty. Being in full‐time education (see online Appendix D) was positively associated with political interest and seeing voting as a duty but had no effect on political efficacy. Respondents in paid employment, on the other hand, were marginally less likely to be interested in politics or feel politically informed. While the mobilising effect of the workplace is expected to increase political engagement, this could reflect the limited time young people have spent in such an environment, as well as the more precarious work conditions they are likely to face.

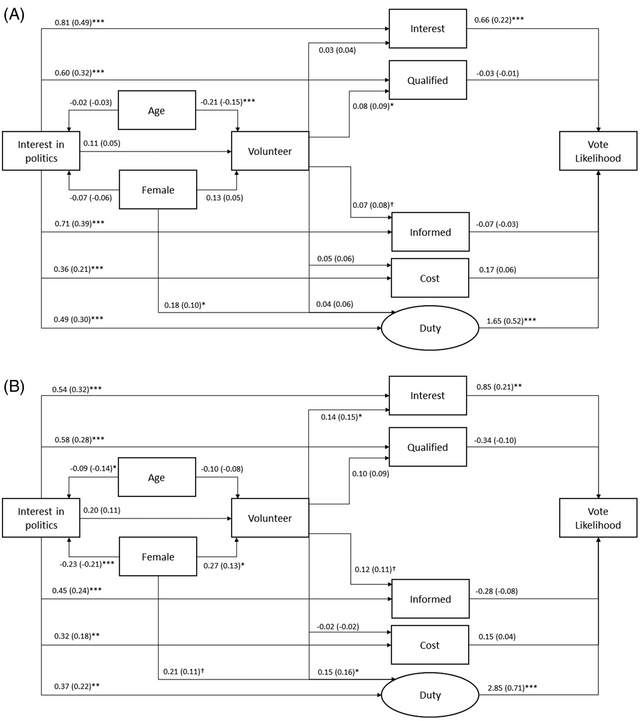

Turning to H2, Figures 3A and 3B summarise the SEM for the groups distinguished by whether respondents’ were raised in politically disengaged or engaged households. The results show considerable heterogeneity in the way volunteering affects adult political engagement depending on prior political socialisation: there are positive effects from volunteering on turnout, but only for children raised in politically disengaged households.Footnote 7 Figure 3A reports the results for respondents from engaged households, for whom the effects of volunteering on Interest, Cost and Duty were close to 0 and non‐significant. There were negligible effects for Qualified (0.09) and Informed (0.08), showing that volunteering can increase feelings of political efficacy by a small amount, but neither of these were significantly related to vote likelihood. In contrast, Figure 3B shows that volunteering had weak but significant effects on Interest (0.15) and Duty (0.16) for children raised by politically disengaged parents, both of which had significant effects on vote likelihood (0.21 and 0.71, respectively). Volunteering also had a weak, positive effect on Informed (0.11), but as with the offspring of engaged parents, this was not significantly related to vote likelihood.

Figure 3. (A) SEM of volunteering and turnout for respondents with engaged parents. (B) SEM of volunteering and turnout for respondents with disengaged parents.

Source: UKHLS. Obs: 693 (475 for A, 218 for B). †, effect statistically significant at 90% confidence; *, 95% confidence; **, 99% confidence; ***, 99.9% confidence. Model fit statistics: RMSEA = 0.045 [0.032–0.058]; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.045.

This means that H2 is supported; therefore, and H1 is partially supported: volunteering does increase attainer turnout by increasing interest in politics (H1a) and the belief that voting is a duty (H1c), but only for people raised by parents with no interest in politics who are unlikely to socialise their children into being politically active (H2). H1b is technically supported for both groups of respondents – volunteering does increase feelings of political efficacy by a small amount – but this was not significantly related to their likelihood of voting and so is not a means through which volunteering affects attainer turnout.

The magnitude of the total volunteer effect can be calculated by summing the direct and indirect effects in the relationship of interest, with the indirect effects the product of the coefficients of each directional effect (e.g., volunteering → Interest × Interest → vote likelihood) (Boomgaarden & Freire, Reference Boomgaarden and Freire2009).Footnote 8 For children from disengaged households, the total effect of volunteering on vote likelihood was 0.48 (p = 0.023): for every increase in the frequency of volunteering, the likelihood of voting increased by 0.48 points. For children from engaged households, the total effect was 0.09 and non‐significant (p = 0.215). While less likely to volunteer than those from politically engaged households, therefore (see Table 2), the benefits of volunteering are greater for children raised in politically disengaged households: they become more interested in politics and likely to see voting as a duty, which makes them more likely to vote in their first election. The effect is, however, of limited magnitude compared with being interested in politics as a child – with a one unit increase in interest leading to a 1.34 increase (p = 0.001) in vote likelihood (regardless of parents’ political interest) – or of being in full‐time education (1.82, p = 0.003), showing that volunteering can only make a limited contribution to reducing inequalities in turnout that have their roots in early socialisation and the socio‐economic circumstances associated with attending higher education.

Wald tests were used to test the significance of the difference in volunteer effects between the groups. They showed that – while close at 90 per cent confidence – neither the difference in the effect of volunteering on political interest or on Duty was significant (p = 0.011 and p = 0.157, respectively). A likelihood ratio test confirmed that the fit of a model for two groups in which all coefficients differed (i.e., Figure 3) was superior to that in which all coefficients were the same (χ2 48.07, p > χ2 0.026), but if only the coefficients for volunteering on Interest and Duty were allowed to vary, the difference was not significant (χ2 3.24, p > χ2 0.198). This means that while we can be confident volunteering affects political interest and civic duty (and, therefore, turnout) for those from disengaged households, we cannot be confident that it is significantly different from that for those from engaged households.

When considering the results of the SEM and these tests, the potential for the small sample (particularly for respondents from disengaged households) to reduce statistical power and increase the likelihood of a Type II error cannot be ignored. This is an unavoidable result of requiring no missing observations in the data, particularly relating to parents’ political interests and cannot be resolved without more data (which is currently impossible to obtain).Footnote 9 This does not mean the SEM lacks sufficient power to identify a significant effect (see online Appendix F), nor does it cast doubt on the validity of the significance tests or effect estimates (i.e., it does not increase the probability of a Type I error). A power analysis (see online Appendix F) also confirms that the rejection of other effects as non‐significant (such as that of Qualified on vote likelihood) is unlikely to constitute a Type II error. Without more data, it is nonetheless impossible to confirm that the differences in volunteer effect are meaningful, meaning that the analyses lend only limited support to H2.

Finally, there are several additional noteworthy observations from the comparison of the grouped SEMs. First, while the effects of political interest and efficacy were the same, the effect of Duty on vote likelihood was stronger for those raised by disengaged parents, at 2.85 compared with 1.65 (the Wald test confirmed this was significant, p = 0.003). This may be related to the second observation: being in full‐time education had a much stronger effect on Duty for respondents from disengaged households, at 0.66 versus 0.23 (difference significant, p = 0.08). Both differences may reflect young people from disengaged households being less likely to be socialised into being politically engaged during childhood, meaning they are less likely to have started to develop habits of participation that may result in them voting regardless of civic duty or education context (Marta & Pozzi, Reference Marta and Pozzi2008). As a result, differences in characteristics or context that affect political behaviour may be more powerful determinants of whether they vote in their first election. If so, this further highlights the importance of early childhood socialisation not only as a determinant of adult political participation but also the influence of contextual factors (such as attending university) that are frequently identified as drivers of political participation in cross‐sectional analyses (e.g., Sloam et al., Reference Sloam, Kisby, Henn and Oldfield2021).

Conclusion

Generational turnout decline is leading to young people – particularly from poorer backgrounds – being under‐represented in public debate and means that electoral decisions are increasingly based on the preferences of older and socio‐economically better off voters. This research has contributed to the study of measures that could help reverse this trend by analysing the effect of childhood volunteering on the turnout of first‐time voters in the United Kingdom. While an extensive literature argues that encouraging children to volunteer could increase turnout, much of that research (e.g., Flanagan et al., Reference Flanagan, Bowes, Jonsson, Csapo and Sheblanova1998; Gaby, Reference Gaby2017; Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2008; Roker et al., Reference Roker, Player and Coleman1999) fails to control for causally antecedent political engagement. This research has shown that this leads to exaggerated estimates of the effects of volunteering for most young volunteers. This study has also considered how the volunteer effect may vary depending on prior political socialisation and showed that there is a significant benefit to volunteering – even with prior political engagement accounted for – for young people raised by politically disengaged parents. For them, volunteering is an opportunity to be exposed to political issues, build networks with other politically active people, and develop attachments to social norms that encourage political participation that they are unlikely to have experienced during early political socialisation. In other words, volunteering can help compensate for the lack of encouragement to engage with politics during their socialisation, which makes them more likely to vote when they become eligible to do so. The children of politically engaged parents, on the other hand, are already likely to have been socialised into being politically engaged during childhood; indeed, this is partly why they are far more likely to volunteer and vote, and why there is a ‘ceiling effect’ to the benefits of volunteering for political participation.

There are several caveats to this conclusion. First, the analyses above showed that the volunteer effect, while significant for those from disengaged households, was not significantly different from that for those from engaged households. This may, as noted above, be a result of limited sample size but it may also be a substantive result that this study cannot confirm. Further research using a larger sample is required, therefore, to verify whether H2 can be accepted. Second, the magnitude of the volunteer effect on turnout was small: as highlighted above, the effects of being in full‐time education or being interested in politics as a child were more important. Even if a concerted effort to utilise volunteering schemes as a way of increasing youth turnout was made, its impact would be far less than that of encouraging more young people from poorer backgrounds to attend higher education or addressing inequalities in access to resources that facilitate political engagement among their parents. Third, the results of this study do not necessarily mean that measures to increase volunteering would affect generational turnout decline because most young people who volunteer come from politically engaged and wealthier households and so are likely to vote anyway. In the sample used for this research, for example, more than four‐fifths of attainers who volunteered were raised by engaged parents. The nature of those who typically volunteer would have to change to include far more young people from disengaged backgrounds before any substantial impact on generational turnout decline was likely to be apparent.

Finally, a limitation of this study is its reliance on a single measure of volunteering available in UKHLS, which makes it unable to determine the effect of different types of volunteering on turnout. The effect of volunteering has been argued to vary depending on the nature of the activity, which dictates how likely the experience is to foster the development of political awareness or civic skills (MacFarland & Thomas, Reference MacFarland and Thomas2006; Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2008; Roker et al., Reference Roker, Player and Coleman1999). A study with access to a more nuanced independent variable may show that some forms of volunteering have a greater impact than others on turnout, and these may also be conditional on political socialisation. Furthermore, while (as discussed above) the findings of this study are suggestive of likely relationships in comparable European, American and Australasian contexts, there is a clear need both to confirm this assumption and exploit the opportunities a cross‐national research design would afford. This includes the capacity to study the impact of party and electoral systems, electoral law or volunteer culture and policies on the effects of volunteering, all of which would greatly enhance the conclusions of this research. Finally, this study looked only at first‐time voters; it did not consider the effect of volunteering on young adults over successive elections. While volunteering increases first‐time voter turnout among those from poorer backgrounds, changes in the life circumstances of young adults (such as leaving the parental home or full‐time education) are frequently detrimental to political engagement and are more likely to be so for those with the fewest socio‐economic resources to support them (such as family wealth). Just as it is possible that the increased turnout stemming from volunteering underpins a habit of voting that persists beyond one's first election, this habit could be ‘wiped out’ by the difficulties associated with early adulthood that those who benefit from volunteering are more likely to face. A further task for future research, therefore, is to analyse the sustainability of the volunteer effect through life events in early adulthood.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Ekaterina Kolpinskaya, Dr. Martin Hansen, Dr Victoria Harkness, Prof. Cees Van der Eijk, Step up to Serve and participants at the Political Studies Association and Elections, Public Opinion and Parties Specialist Group annual conferences for providing invaluable feedback, insight and advice with this research. The author would also like to thank Understanding Society and Wales Institute for Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods – particularly Prof. Sally Power and Prof. Chris Taylor – for supporting the study as well as the anonymous reviewers for their feedback and helpful suggestions. All errors are the responsibility of the author alone.

Data availability statement

The complete code for replicating this analysis can be found on the journal website or is available from the author on request in the form of a Stata .do file. The file requires the user to download the necessary Understanding Society datasets (which are specified in the file) from the UK Data Archive.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: