Introduction

Livestock are of vital importance to communities globally and are the primary income for approximately 70% of the 1.4 billion extremely poor. Of these it is estimated 600 million subsistence livestock farmers globally and approximately two thirds of these are women (MacVicar, Reference MacVicar2020). It has been estimated that women contribute 40% of the agricultural labour force in Africa, though this is much higher in some countries, such as in Tanzania where women are thought to contribute 53% of the agricultural labour force (Palacios-Lopez et al., Reference Palacios-Lopez, Christiaensen and Kilic2017). Gender inequality within the wider food system is estimated to be responsible for a loss of 11% of Africa’s total wealth, and livestock plays a crucial role in rural women’s lives (Breisinger et al., Reference Breisinger, Keenan, Mbuthia and Njuki2023). For subsistence farmers livestock are critical for their survival because livestock generate income, a store of wealth and provide nutritional security. Women in particular face many challenges, including lack of access to agricultural extension services, aid, markets, and smallholder-focused policies (Gannaway et al., Reference Gannaway, Majyambere, Kabarungi, Mukamana, Niyitanga, Schurer, Miller and Amuguni2022; E. Mutua et al., Reference Mutua, De Haan, Tumusiime, Jost and Bett2019). These gendered disparities in access and support also mean that women are more vulnerable to shocks that affect livestock health and productivity.

Despite the economic importance of livestock, many rural subsistence farmers do not reach maximum productivity due to high mortality and morbidity rates due to infectious disease epidemics (Mukamana et al., Reference Mukamana, Rosenbaum, Schurer, Miller, Niyitanga, Majyambere, Kabarungi and Amuguni2022), such as Rift Valley Fever. Rift Valley fever (RVF) is a zoonotic vector-borne disease that has severe economic impacts, affects livestock productivity and survival and is a threat to human health (Nanyingi et al., Reference Nanyingi, Munyua, Kiama, Muchemi, Thumbi, Bitek, Bett, Muriithi and Njenga2015; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Warimwe, Di Nardo, Lyons and Gubbins2018). RVF can cause abortion storms and high mortality rates in livestock (Himeidan, Reference Himeidan2016; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Warimwe, Di Nardo, Lyons and Gubbins2018; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Kortekaas, Bowden and Warimwe2019; McMillen and Hartman, Reference McMillen and Hartman2021), leading to major economic impacts felt by farmers. Abortion storms refer to the sudden increase of abortions within a herd due to disease. Spillover to humans can occur via mosquito bites or close contact with infected materials, such as aerosol spray of blood or ingestion of unpasteurised milk (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Warimwe, Di Nardo, Lyons and Gubbins2018; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Kortekaas, Bowden and Warimwe2019). In human’s symptoms are often non-specific and can lead to misdiagnosis. A small proportion of cases progress onto the haemorrhagic phase of the disease, which has a significantly higher fatality rate (Javelle et al., Reference Javelle, Lesueur, Pommier De Santi, De Laval, Lefebvre, Holweck, Durand, Leparc-Goffart, Texier and Simon2020; Bron et al., Reference Bron, Strimbu, Cecilia, Lerch, Moore, Tran, Perkins and Ten Bosch2021; Chambaro et al., Reference Chambaro, Hirose, Sasaki, Libanda, Sinkala, Fandamu, Muleya, Banda, Chizimu, Squarre, Shawa, Qiu, Harima, Eshita, Simulundu, Sawa and Orba2022).

Given women’s vital but often under-recognised roles in livestock production, they are disproportionately affected by disease outbreaks (Mukamana et al., Reference Mukamana, Rosenbaum, Schurer, Miller, Niyitanga, Majyambere, Kabarungi and Amuguni2022; Byers et al., Reference Byers, Robinson, Hollmann, Ezeocha, Smith and Bukachi2025). Yet the gendered impacts of livestock diseases remain understudied. This is especially concerning for diseases like RVF, which, impacts livestock productivity but also threatens human health, livelihoods, and food security. Understanding how these impacts differ by gender is critical to designing equitable and effective public health and veterinary responses.

The aim of this perspective paper is to use Rift Valley fever as a case study to explore how gender inequality in relation to infectious diseases poses obstacles to the safety and wellbeing of women. It extends discussion of the results on gender identified as part of a rapid review of the literature on the socioeconomic impacts of RVF (O’Neill et al., Reference O’Neill, Gubbins, Reynolds, Limon and Giorgakoudi2024). To complement this previous academic literature review we searched the Overton policy database (https://overton.io/) and the Lens database to identify additional grey literature and policy reports. Neither search identified any relevant policy or civil society documents that explicitly mentioned these issues.

Gender disparity of exposure in occupational health

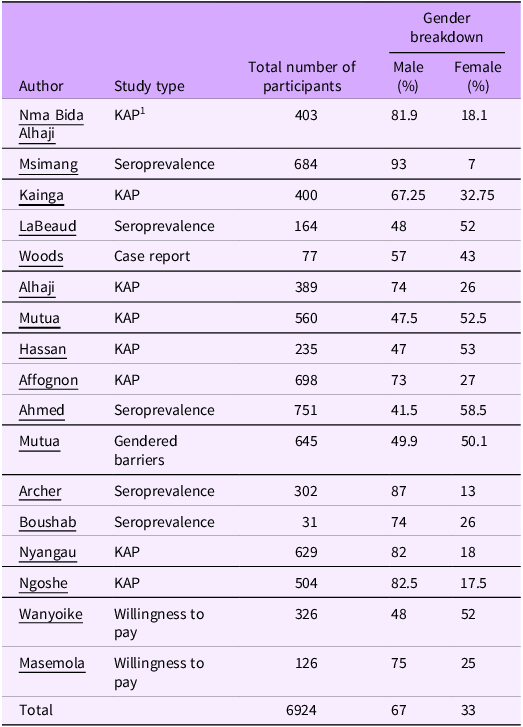

Epidemiological studies of RVF generally focus on animal infections and individuals in close contact with animals. Our previous work found no study which directly investigated the risks or impacts associated to RVF and women (O’Neill et al., Reference O’Neill, Gubbins, Reynolds, Limon and Giorgakoudi2024). Of the 17 epidemiological studies (out of 93 studies identified in our previous work) (Table 1), 11 studies had a bias towards male participants with an average of 67% male participants (range 57%–93% male). Women are grouped together under the occupation of housewife. As women have varied responsibilities, beyond household duties, including preparation of food/ animal products, tending to the young and sick livestock, and milking responsibilities (E. Mutua et al., Reference Mutua, De Haan, Tumusiime, Jost and Bett2019; Nyangau et al., Reference Nyangau, Nzuma, Irungu and Kassie2021), this classification makes it difficult to assess their risk of exposure to RVF.

Table 1. Presents the participatory studies included in the socio-economic impact of Rift Valley fever: a rapid review and discussed in this perspective paper

1 KAP – knowledge, attitudes and practices.

Previous studies have suggested that men, especially in pastoralist communities, are at a greater risk of RVFV exposure due to the extended periods of time they spend moving their livestock (cattle) between pasture, compared to women and other occupations (Affognon et al., Reference Affognon, Mburu, Hassan, Kingori, Ahlm, Sang and Evander2017; A. Heinrich et al., Reference Heinrich, Saathoff, Weller, Clowes, Kroidl, Ntinginya, Machibya, Maboko, Löscher, Dobler and Hoelscher2012; Archer et al., Reference Archer, Thomas, Weyer, Cengimbo, Landoh, Jacobs, Ntuli, Modise, Mathonsi, Mashishi, Leman, le Roux, Jansen van Vuren, Kemp, Paweska and Blumberg2013; LaBeaud et al., Reference LaBeaud, Pfeil, Muiruri, Dahir, Sutherland, Traylor, Gildengorin, Muchiri, Morrill, Peters, Hise, Kazura and King2015; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Makame, Robert, Julius and Mecky2018; Bron et al., Reference Bron, Strimbu, Cecilia, Lerch, Moore, Tran, Perkins and Ten Bosch2021; E. N. Mutua et al., Reference Mutua, Bukachi, Bett, Estambale and Nyamongo2017). Other occupations, which are generally male dominated, such as butchers and abattoir workers, are at increased risk of RVFV exposure through close contact with animal blood and bodily fluids (Heinrich et al., Reference Heinrich, Saathoff, Weller, Clowes, Kroidl, Ntinginya, Machibya, Maboko, Löscher, Dobler and Hoelscher2012; Archer et al., Reference Archer, Thomas, Weyer, Cengimbo, Landoh, Jacobs, Ntuli, Modise, Mathonsi, Mashishi, Leman, le Roux, Jansen van Vuren, Kemp, Paweska and Blumberg2013; Nanyingi et al., Reference Nanyingi, Munyua, Kiama, Muchemi, Thumbi, Bitek, Bett, Muriithi and Njenga2015; Van Vuren et al., Reference Van Vuren, Kgaladi, Patharoo, Ohaebosim, Msimang, Nyokong and Paweska2018; Msimang et al., Reference Msimang, Thompson, van Vuren, Tempia, Cordel, Kgaladi, Khosa, Burt, Liang, Rostal, Karesh and Paweska2019; Bron et al., Reference Bron, Strimbu, Cecilia, Lerch, Moore, Tran, Perkins and Ten Bosch2021).

However, this assumed increased risk of exposure is not necessarily supported by seroprevalence studies, Of the six seroprevalence studies identified in our earlier research (Table 1), half (3/6) did not provide sex aggregated data for occupation. Two found no statistically significant difference in seropositivity rates between males and females and only one found males are more likely to be RVF seropositive. If studies are demonstrating no statistically significant difference in seropositivity levels between men and women, are we as researchers inadvertently reinforcing gender inequality within epidemiology studies by maintaining the narrative of men are at greater risk of RVF exposure? It is critical that gender is incorporated into epidemiological research to ensure both men and women are actively included in the planning and design of interventions. Only then can we achieve a truly One Health approach – one that develops balanced, gender-responsive strategies integrating human, animal and environmental health in RVF control and prevention.

Gender disparities in ownership, prevention, and treatment of livestock

In many societies women face limited control over their income, ownership of higher value livestock, access to and control of productive resources, and ownership and access to land (Fischer and Qaim, Reference Fischer and Qaim2012; Tavenner and Crane, Reference Tavenner and Crane2018; Acosta et al., Reference Acosta, Ludgate, McKune and Russo2022; Gannaway et al., Reference Gannaway, Majyambere, Kabarungi, Mukamana, Niyitanga, Schurer, Miller and Amuguni2022; Mukamana et al., Reference Mukamana, Rosenbaum, Schurer, Miller, Niyitanga, Majyambere, Kabarungi and Amuguni2022; Byers et al., Reference Byers, Robinson, Hollmann, Ezeocha, Smith and Bukachi2025). This is because of sociocultural, religious and institutional norms in RVF endemic countries. It must be noted that norms differ between communities and countries. A study in Rwanda reported the main barriers to women entering the livestock RVF vaccine value chain were laws and regulations, access to resources including credit, vaccines and infrastructure, cultural norms and gender stereotyping, and lastly weakness with vaccine distribution and training opportunities (Gannaway et al., Reference Gannaway, Majyambere, Kabarungi, Mukamana, Niyitanga, Schurer, Miller and Amuguni2022). These structural barriers restrict women’s autonomy of choice to protect themselves by vaccinating their livestock and highlights the clear disadvantage to women of sociocultural norms and the male-dominated design of the vaccine chain.

Women tend to own lower-value livestock, such as poultry and goats. In the context of RVF the main susceptible livestock species are cattle, sheep and goats, with sheep being the most susceptible. However, national vaccination programmes tend to focus on cattle, even though in the case of RVF sheep and goats are more susceptible compared to cattle (Acosta et al., Reference Acosta, Ludgate, McKune and Russo2022; Gannaway et al., Reference Gannaway, Majyambere, Kabarungi, Mukamana, Niyitanga, Schurer, Miller and Amuguni2022; Mukamana et al., Reference Mukamana, Rosenbaum, Schurer, Miller, Niyitanga, Majyambere, Kabarungi and Amuguni2022; Tukahirwa et al., Reference Tukahirwa, Mugisha, Kyewalabye, Nsibirano, Kabahango, Kusiimakwe, Mugabi, Bikaako, Miller, Bagnol, Yawe, Stanley and Amuguni2023; Byers et al., Reference Byers, Robinson, Hollmann, Ezeocha, Smith and Bukachi2025). Larger herd sizes are also prioritised for vaccination, excluding small herds often owned by women and other smallholders (Acosta et al., Reference Acosta, Ludgate, McKune and Russo2022; Tukahirwa et al., Reference Tukahirwa, Mugisha, Kyewalabye, Nsibirano, Kabahango, Kusiimakwe, Mugabi, Bikaako, Miller, Bagnol, Yawe, Stanley and Amuguni2023). Consequently, in an RVF outbreak, sheep and goats owned by women are at risk and so is their income and access to food especially animal source protein.

As part of the invisible work women and children do in livestock rearing, women are more likely to take care of sick livestock, increasing their risk of RVF exposure (Miller, Reference Miller2011; Breisinger et al., Reference Breisinger, Keenan, Mbuthia and Njuki2023). A study in Uganda reported women have excessive workloads completing more daily tasks in livestock production as compared to men, resulting in less time to tend to their own animals or attend educational programmes (Tukahirwa et al., Reference Tukahirwa, Mugisha, Kyewalabye, Nsibirano, Kabahango, Kusiimakwe, Mugabi, Bikaako, Miller, Bagnol, Yawe, Stanley and Amuguni2023). Although women spend more time compared to men with animals, women are restricted in their autonomy on treating sick animals and vaccination of livestock. For example, a study in Kenya and Uganda has reported that even when women are head of households, they are still required to consult male family members regarding treatment of sick livestock (E. Mutua et al., Reference Mutua, Namatovu, Campbell, Tumusiime, Ouma and Bett2024). These cultural and institutional norms not only limit women’s autonomy in livestock care but also influence their ability to engage in critical health interventions, such as vaccination.

In an attempt to address gendered barriers and increase vaccine uptake, a research team from ILRI, ran RVF vaccination campaigns in Kenya using a gender-based approach (Campbell, Reference Campbell2023). The modifications to the vaccination campaign included hiring women champions, working with community disease reporters and local leaders to ensure the correct messaging of the campaign was conveyed and providing facilities to make it easier for women to control their herds and prevent animal injury. Although preliminary data suggest that the intervention (with gender modifications) performed no better than the control group (without gender modifications), the impact indicators used were purely quantitative, limiting the ability to capture the full scope of the intervention’s effects. Logistical challenges were identified as potential reasons for the lack of positive differences in the intervention group, which included delays in vaccine delivery affecting only the intervention group, and the vaccination campaign occurred at the same time than most animals were pregnant, Nonetheless, lessons learned can inform future vaccination campaigns. Indeed, other studies have shown that reducing gendered barriers in the livestock sector increases women’s access to vaccines (McKune et al., Reference McKune, Serra and Touré2021; Serra et al., Reference Serra, Ludgate, Fiorillo Dowhaniuk, McKune and Russo2022; Njiru et al., Reference Njiru, Galiè, Omondi, Omia, Loriba and Awin2024).

Although this has not yet been translated into formal policy, the Kenyan Government has held workshops in how to consider gendered barriers to vaccine uptake for their RVF contingency plan (Bett, Reference Bett2022; Campbell, Reference Campbell2023; Tramsen, Reference Tramsen2023). At the time of writing (April 2025) the contingency plan is being finalised and has not been published. Other endemic countries, such as Tanzania, are also developing One Health preparedness plans for RVF. Now is the perfect time to acknowledge gender inequality and incorporate gender responsive interventions that will better target animal, environmental and the health of men, women and children in an equitable and sustainable fashion.

Gender disparity in knowledge of RVF

Knowledge of disease is of significant importance to reducing exposure and transmission, as a lack of knowledge can increase unsafe farming practices (Alemayehu et al., Reference Alemayehu, Mamo, Desta, Alemu and Wieland2021). However, it has been reported increased knowledge does not always lead to good farming practices (Alhaji et al., Reference Alhaji, Babalobi and Isola2018; Etter et al., Reference Etter, Gomez-Vazquez and Thompson2022; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Bhuiyan, Chalise, Mamun, Bhandari, Islam, Jami, Ali and Sabrin2025). Eight Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) studies were identified in our previous research (Table 1). Six (out of eight) KAP studies were biased towards male participants (range 67%–83%). However, it is difficult to draw direct comparisons between the studies as they collected different information regarding knowledge of RVF. Moreover, KAP scores were not sex disaggregated in any of the studies, so it is not possible to distinguish if there was a knowledge-gap between men and women.

Female farmers are disadvantaged due to lack of relatable information (prevention and control) regarding RVF, and lack of access to this information (Gannaway et al., Reference Gannaway, Majyambere, Kabarungi, Mukamana, Niyitanga, Schurer, Miller and Amuguni2022). This is partly because women are not permitted to attend educational programmes if they are led by men for sociocultural and sometimes religious reasons. As a result, women have restricted access to vital information and education programmes regarding transmission, control and prevention of RVF (Njuki and Sanginga, Reference Njuki and Sanginga2013). Other examples of dissemination of information to the public, for example posters in public places (Mutua et al., Reference Mutua, De Haan, Tumusiime, Jost and Bett2019), are restrictive for women because of their domestic roles (Namatovu et al., Reference Namatovu, Campbell and Ouma2021). Many individuals in rural pastoral communities have limited or no education, with a high rate of illiteracy. For example, it has been reported the Maasai have the highest illiteracy rates (75%) (Pesambili, Reference Pesambili2020). This is a stark comparison to the estimated illiteracy rates of the continent of Africa which is estimated to be 33% (Statista, 2022; Mutua et al., Reference Mutua, De Haan, Tumusiime, Jost and Bett2019; Namatovu et al., Reference Namatovu, Campbell and Ouma2021). Access to this information is therefore limited to men who can read and are attending public spaces (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2019). Radios are also often used to disseminate information (Mutua et al., Reference Mutua, De Haan, Tumusiime, Jost and Bett2019), however these are more typically used by men, and so again leaves women to rely on their male counterparts to relay the information (Namatovu et al., Reference Namatovu, Campbell and Ouma2021).

Male dominated research teams are a further barrier for women to enter the livestock value chain, this further compounds the barriers discussed above. A greater inclusion of female researchers would enable more women to attend KAP studies and educational campaigns. Greater attendance of women at these events will enable them to have a greater influence on research agendas, put across their point of view and challenges faced, all of which may not be considered at a male dominated event. Empowering women through female led educational programmes will result in women gaining a greater understanding of RVF and reducing their risk of exposure (Namatovu et al., Reference Namatovu, Campbell and Ouma2021).

Maternal care

The risks posed by RVF to pregnant women are poorly understood, however, existing evidence suggests that urgent research is required to fill this knowledge gap and support the design of targeted policies to protect pregnant women during RVF outbreaks (Arishi et al., Reference Arishi, Aqeel and Al Hazmi2006; Adam and Karsany, Reference Adam and Karsany2008; Baudin et al., Reference Baudin, Jumaa, Jomma, Karsany, Bucht, Näslund, Ahlm, Evander and Mohamed2016; McMillen and Hartman, Reference McMillen and Hartman2021). To our knowledge, there is no specific national policies that address RVF and maternal health services. Our previous research (O’Neill et al., Reference O’Neill, Gubbins, Reynolds, Limon and Giorgakoudi2024) and the searches of grey literature and policy documents (Overton and Lens databases) did not find any national or global level policy documents of RVF and pregnant women.

In livestock, RVF is known to cause abortion storms during outbreaks. In fact, abortion storms in livestock are often considered the first indicators of RVF outbreaks in endemic countries (McMillen and Hartman, Reference McMillen and Hartman2021). Despite this well documented phenomenon, the potential for RVF to lead to miscarriages and other complications in pregnant women is not well understood.

Only a few studies have attempted to explore RVF related pregnancy outcomes in women. One study sampled the seroprevalence of three groups (45 women who aborted pre-outbreak; 51 women who aborted during the outbreak; and 115 randomly selected male and females from local villages) as a proxy for RVF abortions. No significant difference was seen between the three groups, with seroprevalences of 31%, 28% and 33%, respectively (Abdel-Aziz et al., Reference Abdel-Aziz, Meegan and Laughlin1980). Another study found a significantly higher rate of still births for RVF positive mothers (15%; 10/65) as compared to RVF negative mothers (6%; 209/3124) (Niklasson et al., Reference Niklasson, Liljestrand, Bergström and Peters1987). Both studies called for larger studies to be conducted to gain a greater understanding of RVF and pregnant women, but this call has largely been unanswered.

More recent evidence of vertical transmission (transmission of RVF from mother to foetus) of RVF in pregnant women has been reported in Saudi Arabia in 2000 (Arishi et al., Reference Arishi, Aqeel and Al Hazmi2006) and in Sudan in 2007 and 2011 (Adam and Karsany, Reference Adam and Karsany2008; Baudin et al., Reference Baudin, Jumaa, Jomma, Karsany, Bucht, Näslund, Ahlm, Evander and Mohamed2016). The first report was in Saudi Arabia during the outbreak in 2000, where a five-day old infant was admitted to hospital with respiratory issues and died two days later. It was later found that four days prior to the delivery, the mother developed RVF-like symptoms after being in contact with sick or aborting animals during the RVF outbreak (Arishi et al., Reference Arishi, Aqeel and Al Hazmi2006). The first report in Sudan included a pregnant woman who was hospitalised with RVF symptoms and was later diagnosed with RVF. The child was born with an enlarged spleen, liver and was clinically diagnosed with jaundice (Adam and Karsany, Reference Adam and Karsany2008). The second report in Sudan arose from a study conducted in 2011, where 28 out of 130 pregnant women (18%) were positive for RVF infection. Of these 28 women, 54% had a miscarriage compared to 12% of women who were RVF negative. Patients positive for RVF also had higher rates of bleeding, joint pain and malaise. The same Sundanese study reported vertical transmission in women (Baudin et al., Reference Baudin, Jumaa, Jomma, Karsany, Bucht, Näslund, Ahlm, Evander and Mohamed2016). Therefore, urgent research is required to gain a greater understanding of the risks related to RVF and pregnant women.

Despite these findings, the relationship between RVF and pregnancy complications in women remains severely underexplored. More robust data and research is urgently required to understand the full extent of the risks of RVF poses to pregnant women and to aide in the development of policies that ensure maternal health protected in future RVF outbreaks.

Conclusion

Gender inequality in RVF disease surveillance and control poses a significant threat to women’s wellbeing and livelihoods. This paper uses RVF as a case study but has also highlighted inequality using examples from other diseases. It is imperative that we acknowledge and tackle gender inequalities so that communities, public health, and veterinary systems are better prepared to respond to outbreaks in the future.

Despite an increasing frequency of RVF outbreaks, current surveillance efforts often overlook gender-specific interventions. It is evident that there is a clear knowledge gap in our understanding of transmission and impact on women. Women are also disadvantaged regarding access to knowledge and practices to prevent RVF because they do not have access to the relevant information.

Women’s participation in the agricultural sector has been widely documented, but it is critical for more gendered data on the roles of women in different contexts agricultural, livestock and vaccine value chains. This will ensure we build a greater understanding the transmission dynamics of both men and women. By incorporating gender-sensitive approaches in study design, data collection and analysis, we can target interventions and improve the effectiveness of RVF prevention and control measures for all populations.

Data availability statement

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials – “The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.”

Author contributions

Luke O’Neill, Georgina Limon, Simon Gubbins, Christian Reynolds and Kyriaki Giorgakoudi

Conceptualisation CR, GL, KG, LO’N and SG

Data Curation LO’N

Formal Analysis LO’N

Funding Acquisition GL, KG and SG

Investigation LO’N

Methodology CR, GL, KG, LO’N and SG

Project Administration CR, GL, KG, LO’N and SG

Supervision CR, GL, KG and SG

Validation GL and KG

Visualisation CR, GL, KG, LO’N and SG

Writing – original draft LO’N

Writing – review and editing CR, GL, KG, LO’N and SG

Financial support

This work is part of a PhD project that is jointly funded by the School of Health and Psychological Sciences, City, University of London and The Pirbright institute. In addition, G.L. and S.G. acknowledge funding from the UKRI Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant codes BBS/E/I/00007036, BBS/E/I/00007037, BBS/E/PI/230002C and BBS/E/PI/23NB0004). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. None of the authors receive a salary from the funders.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The data used in this perspective paper is publicly available and public health data is based on anonymous data. Therefore, the study does not meet the criteria for “research involving human beings” and so does not require ethical approval.

Comments

No accompanying comment.