Ensuring the quality of services lies at the heart of clinical governance. Benchmarking is an activity that can inform the process of clinical governance (Reference BAYNEYBayney, 2005). The emphasis on community-based services in policy documents such as the National Service Framework for Mental Health (Department of Health, 1999) has led to a relative neglect of setting out standards for evaluation of liaison psychiatry services, with the exception of emergency services. The joint document of the Royal Colleges The Psychological Care of Medical Patients: A Practical Guide (Royal College of Physicians & Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2003) makes recommendations for the structure of services, but stops short of recommending quality indicators.

External benchmarking involves, but is not confined to, comparing standards in a service with other good services anywhere in the world. After a review of the literature we identified two recent studies that have explicitly set quality indicators and evaluated their services against these standards, one from Australia (Reference HOLMES, JUDD and YEATMANHolmes et al, 2001) and the other from Switzerland (Reference ARCHINARD, DUMONT and DE TONNACArchinard et al, 2005). The indicators were in the areas of timeliness of response, communication with referrers and follow-up agencies, and supervision of trainees. Holmes et al (Reference HOLMES, JUDD and YEATMAN2001) found that more than 70% of patients were seen within 48 h in specialist liaison psychiatry but services just failed to attain 90% targets for patients seen within 24 h in general liaison. Archinard et al (Reference ARCHINARD, DUMONT and DE TONNAC2005) reported that 93% of patients were seen within 36 h, 95.7% of emergencies were seen on the same day and 97.5% of patients were reported to supervising psychiatrists. The aim of our project was to adapt the quality indicators to a British setting, a priori set the targets for their attainment and to measure our achievement of these targets.

Method

Study setting

St Thomas’ Hospital is a 600-bed teaching hospital in south London. Liaison psychiatry services are provided across the age range and in specialist areas such as perinatal and neuropsychiatry liaison services. The team that is the subject of this report provides a consultation–liaison service to the in-patient wards at the hospital for patients aged 18-65 years. All referrals are accepted through a dedicated bleep from 09.00 to 17.00 h Monday to Friday; referrals made out of hours are seen by duty psychiatrists who are provided group supervision weekly by a consultant liaison psychiatrist. The members of staff include a consultant psychiatrist, a specialist registrar, two senior house officers and a liaison psychiatry nurse.

Development of benchmarks

We adapted timeliness of response and communication indicators from Holmes et al (Reference HOLMES, JUDD and YEATMAN2001), and supervision indicators from Archinard et al (Reference ARCHINARD, DUMONT and DE TONNAC2005). Holmes et al (Reference HOLMES, JUDD and YEATMAN2001) had two categories dealing with timeliness of response to referrals from areas other than the emergency department: general referrals being seen within 24 h and specialist referrals being seen within 48 h, with targets of 90% for the former and 70% for the latter. We adapted this into the following two standards:

-

• indicator 1, all referrals to be seen by the end of next working day

-

• indicator 2, all referrals following self-harm to be seen by the end of same day.

The indicators dealing with communication related to communicating with the referrer both pre- and post-assessment and with the follow-up agency. We felt that since our style of work involved acceptance of telephone referral through a dedicated bleep, monitoring of the indicators relating to communicating with referrers was superfluous. Our indicator 3 was:

-

• all discharges to be followed by communication with follow-up agency where follow-up was recommended.

Archinard et al (Reference ARCHINARD, DUMONT and DE TONNAC2005) set 95% targets for discussion with a senior psychiatrist following assessment and joint assessment with a senior psychiatrist where indicated. We adapted this to our indicator 4:

-

• all consultations to be discussed with supervising psychiatrist by the end of next working day.

Assessment of benchmarks

All evaluations were logged on a structured pro forma that recorded socio-demographic information and clinical details, including diagnosis, interventions and outcome. Our assessment tool contained questions designed to assess the four indicators. We set a target of 90% for the attainment of these standards. The study received approval from the Lambeth Clinical Governance Committee of the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust.

Results

There were 145 evaluations carried out by the service during the 6-month study period from February to July 2006. Out of the referred patients 60% were male. Of 109 referrals where a clear reason for referral was specified, 49 (45%) were for assessment of depression, 33 (30%) for assessment following an episode of self-harm, 10 (9%) for psychosis, 6 (5.5%) each for alcohol-related problems and confusion, and 5 (4.6%) for assessment of capacity to refuse treatment.

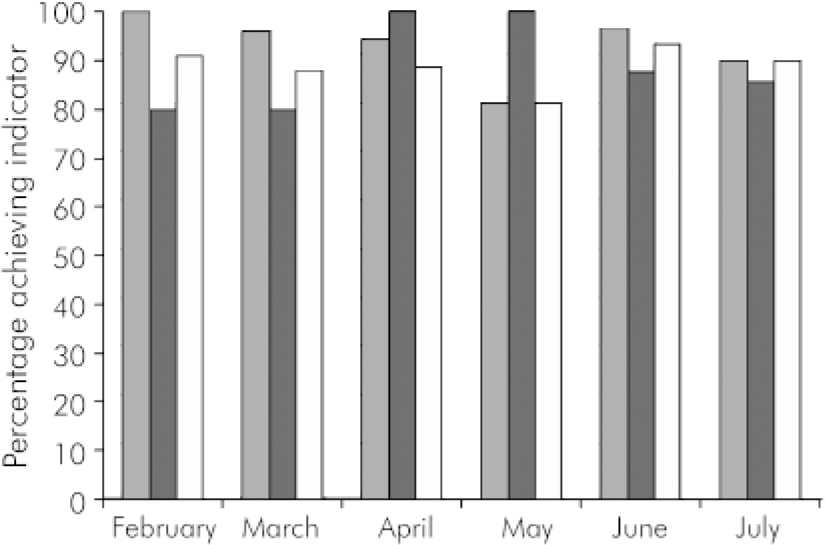

As the assessment sheet did not have enough information to meaningfully assess indicator 3, our analysis refers to the other three indicators. We chose to interpret missing information conservatively, classifying it as failure to comply with the standard. In the same spirit we classified referrals made on Friday and seen on Monday as having failed to comply with the standard. Overall, indicators 1, 2 and 4 were achieved in 93.8, 87.5 and 89.6% of cases respectively. Figure 1 shows the percentage of cases where the indicators were achieved in each month during the study.

Discussion

This is the first report that has explicitly assessed the service delivery and supervision standards in a British liaison psychiatry service against internationally comparable services. We achieved well above the target on the general timeliness to respond indicator, almost achieved the target on the supervision indicator and narrowly missed the target on the emergency indicator in spite of analysing our data conservatively. Our performance is broadly comparable to the services we were bench-marking ourselves against, although it is not possible to directly compare the results as some of our standards were slightly different and in some cases more stringent than the others. An example is our supervision standard which specified that the assessment should be discussed with a clinical supervisor by the end of the next working day; this time limit was absent in the Swiss study.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of patients for which the indicators were achieved in each of the 6 months of the study period.

![]() , indicator 1; ▪, indicator 2; □, indicator 4.

, indicator 1; ▪, indicator 2; □, indicator 4.

We have shown that it is possible to provide a responsive consultation–liaison service that maintains a high standard of supervision of junior medical staff. It is important to point out that our service, although better staffed than the average London general hospital liaison service (Reference KEWLEY and BOLTONKewley & Bolton, 2006), is by no means a ‘Rolls Royce’ service and largely conforms to the staffing recommendations of the Royal Colleges. The provision of liaison psychiatry services remains patchy in most parts of the UK, including in cities such as London (Reference RUDDY and HOUSERuddy & House, 2003; Reference KEWLEY and BOLTONKewley & Bolton, 2006), and recently some liaison services have been threatened with closure. This may be because liaison psychiatry is often equated with work in emergency departments and is seen as replaceable with crisis resolution services. In-patient liaison psychiatry requires the ability to respond quickly, to collect and integrate information from disparate sources in a short amount of time and implement a management plan in an environment not always conducive to psychosocial issues. Such a labour-intensive process is impossible to achieve without a dedicated service with input from experienced and senior specialists.

A limitation of our study is that the data collection was in the course of routine clinical work, and hence some information is missing. This is particularly relevant to indicator 3, which was related to outcome, as opposed to the other quality indicators that dealt with process. Liaison psychiatrists need to prioritise outcome measurement and develop better and simple outcome measures, as outcome is of utmost importance to commissioners and policy makers. Although we measured the speed of response and the adequacy of supervision, we did not specifically evaluate the quality of the interventions either in terms of referrer or patient satisfaction, or the evidence-based nature of the interventions. It would have been impossible to measure satisfaction in our study and we are carrying out an independent qualitative study of referrer perceptions of our service. It is also relevant that a qualitative study of service users and hospital staff in east London found that speed of response and experience of the professional were considered important by both groups (Reference EALES, CALLAGHAN and JOHNSONEales et al, 2006). As for the nature of the interventions, the evidence base for interventions in liaison psychiatry is rather weak and needs to be strengthened (Reference RUDDY and HOUSERuddy & House, 2005).

When trying to ‘prove’ its utility to commissioners, in-patient consultation–liaison psychiatry faces a unique problem, that is, the rapid turnover of patients on medical wards and the brief, intensive and often systemic nature of the interventions which makes it difficult to demonstrate symptomatic improvement or cost-effectiveness (Reference BORUS, BARSKY and CARBONEBorus et al, 2000). The introduction of policies such as payment by results (Reference FAIRBAIRNFairbairn, 2007) complicates the issue further for liaison psychiatry. On the positive side, there is an opportunity to establish psychiatric care as an integral part of the care package for medical inpatients; the risk is that general hospital managers might fear that the input of a high-quality liaison service would inflate the tariff for a treatment episode and primary care managers that the unmet psychosocial needs identified by the liaison service might prolong hospital stay. The acknowledgement of the importance of psychiatric care will only happen if national bodies such as the Faculty of Liaison Psychiatry lobby policy makers and quality assurance agencies such as the Healthcare Commission. Good data collected locally and benchmarked against national standards would go a long way in making this case. Such a benchmarking exercise will also help drive up the standard of care generally and allow learning from best practice, which is the essence of benchmarking (Reference BAYNEYBayney, 2005).

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.