Introduction

Internationalisation has become reality for higher education institutions worldwide (Mittelmeier et al. 2022). Yet, some universities, and particularly their teaching staff, across Europe remain largely unprepared for accommodating their curricula and teaching methods to the needs of international and also home students. The two-year academic development programme Effective teaching for internationalisation (ETI) has been designed to address this gap at two Central European institutions, Masaryk University, Brno, Czechia and Comenius University Bratislava, Slovakia. This programme has offered participant teachers an opportunity to experience and pilot in their courses a range of innovative educational approaches that respond to the needs of international students. Mixing teachers from two universities and from five countries (Czechia, Iran, Israel, Poland and Slovakia) provided unique opportunities for learning by doing through engaging participants in peer learning and peer assessment.

The impact of such academic development programmes tends to be assessed on the individual level (Pleschová and Simon Reference Pleschová, Simon, Simon and Pleschová2013). Similarly to such studies, in this course, when comparing participants’ views before enrolling in it and after graduating, we found evidence for a positive change in programme participants’ perceptions of internationalisation and commitment to student-centred learning (Simon and Pleschová 2022). Furthermore, scholarship of teaching and learning (SOTL) research on student learning published by ETI programme graduates shows that participant teachers markedly changed their teaching practices through internationalising their students’ learning (Pleschová and Simon 2022; Chovančík’s study in this symposium).

However, studying only the individual level impact in the context of an organisation-wide challenge has left gaps in the literature. The few studies that successfully address the impact of academic development programmes on institutional teaching culture take a bottom-up approach and investigate how individual programme participants influence their immediate environment (e.g. Amundsen and D’Amico Reference Amundsen and D’Amico2019; Wheeler and Bach Reference Wheeler and Bach2021). We take a similar approach in exploring how the ETI programme fosters internationalised and student-centred learning at the meso level. We conduct a case study of two programme graduates, mapping the initiatives of these faculty members, the ways they work and the influence they have on the teaching and learning environment at their institution. We explore their activities through the notion of grassroots leadership, which should be familiar to political scientists who study social movements. This concept was adapted by Kezar et al. (Reference Kezar, Gallant and Lester2011) to investigate tactics used both by faculty and administrative staff members in the USA. We find this framework is equally applicable to analysing the activities of higher education teachers in the European context and the most appropriate to capture the range of their methods of activism, one semester after the end of the ETI programme.

Based on the data analysed in this research, we claim that an academic development programme can serve as a catalyst for experienced faculty members to widen, intensify and refocus their earlier initiatives. We show how individual level impact spills over into the institutional sphere through two different styles of activism. We begin the study by providing background information about the ETI programme and its participants. Then we describe the analytical framework of grassroots leadership and the data on which this study is based. In the first part of our analysis, we construct individual narratives for the activism of both programme participants, followed by a reflection on the potential of grassroots level engagement for propagating the individual level change to the institutional level. We also contextualise the meaning and the nature of grassroots leadership in Central Europe. The article concludes with the implications for studying the outcomes of educational development programmes and for analysing non-radical change at higher education institutions.

Supporting internationalisation through peer learning

The Effective teaching for internationalisation programme was designed to prepare university teachers to enhance their teaching skills, sensitise them to the demands of and opportunities in an internationalised higher education environment, and help them to introduce a new course or adapt an existing one for teaching international students, including mixed groups of local and international students. It has been accredited on both the national—by the Faculty of Arts at Comenius University Bratislava in Slovakia—and international—under the Supporting Learning Award scheme of the British Staff and Educational Development Association (SEDA)—levels. Because it aims to support teaching of international students, the programme was offered in English. It was first delivered between September 2020 and June 2022, mostly remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic at the time.

The two-year programme was built around the pillars of peer learning and good practices of teaching and learning because high quality internationalised education can only be realised if the teaching methods meet the current standards for higher education teaching and learning. However, frontal lecturing is still prevalent at Central European Universities, which is at odds with the experience of most incoming international students from the West. Furthermore, the most effective way of realising the benefits of internationalising the classroom is through having international and home students sharing their learning experience through peer learning, which is a specific type of active learning. Thus, the programme centres around both internationalisation and student-centred learning methods, and more specifically peer learning.

The programme in 2020–2022 comprised seven half-day workshops offered in the first semester, which encouraged participants to use active learning methods and peer learning as ways to attend to the needs of international students. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the workshops were offered online. In the workshops, a team of international facilitators demonstrated ways of catering to the needs of the international student body by using a variety of activities, with a special stress on those encouraging peer learning. The workshops covered issues and concepts such as internationalisation abroad and at home, curricular design for international classrooms, the benefits and challenges of student-centred course design in an international classroom, challenges of internationalisation, assessment practices with international students and teaching and learning in an international classroom remotely. During the last workshop, each participant facilitated a fifteen-minute micro-teaching session demonstrating how they would teach a concept in their discipline to a classroom of international students. In establishing the needs of international students, participants relied not only on what they learnt during the workshops but also on practices they were familiar with in their department, and if available, on their prior experience teaching international students, studying abroad or learning with foreign peers.

In the other three semesters, each programme participant worked under the tutelage of a coach, who helped them integrate what they learnt in the workshops into their teaching practice. This included revising or developing their syllabi and session plans based on the principles of student-centred education and internationalisation. Innovated class designs typically engaged students in peer learning and/or peer assessment, and thus built upon the diverse knowledge, skills and experiences of international and home students. In the final assignment, participant teachers evaluated the outcomes of new approaches to student learning in a scholarship of teaching and learning (SOTL) study (for more about the programme design, see Pleschová Reference Pleschová2020).

Of the thirty-one faculty members and doctoral candidates who enrolled in the programme, twenty-two graduated: nineteen from Comenius University Bratislava and three from Masaryk University. As we have showed elsewhere (Simon and Pleschová 2022), programme graduates met the course objectives of actively recognising and reflecting on the needs and expectations of home and international students using a variety of student-centred methods and in their teaching, evidenced in their compulsory classroom observations, self-reflective SOTL studies and the assessment of their coaches. Programme graduates also evidenced positive changes in how they think about teaching and how they teach: they became more conscious in their choices of internationalising the education of their—home and international—students and more confident to teach international students, than before the programme. As a result of the programme, participants enriched the curriculum at both universities across a wide variety of study programmes including economics, journalism, linguistics, medicine, law, political science, psychology and museology. Overall, twenty-four new or redesigned English-language courses were added to the curriculum—nineteen at Comenius University Bratislava and five at Masaryk University—increasing the number of courses designed with the specific learning needs of incoming international students in mind. In and of itself, such changes to the curriculum demonstrate the impact at the institutional, rather than the individual level. Nonetheless, we show below that, as grassroots leaders, individual programme graduates can influence the teaching and learning culture of the institution in other meaningful ways.

Grassroots leaders in academia

The concept of grassroots leadership originates from social movement theory, where it is used to analyse the activities and impact of those agents of change who do not wield formal institutional power (Meyerson and Scully Reference Meyerson and Scully1995). Their leadership role comes from their position within and service to their communities rather than from holding an elected office or being appointed to a position in the organisation. As a result, these individuals take a bottom-up approach and work through a non-hierarchical and collective process, building relations and seeking alternative sources to spread their vision. Grassroots activism is the typical strategy of underprivileged and underrepresented groups fighting for their rights (e.g. Bernal Reference Bernal1998; Irons Reference Irons1998). Drawing parallels between the leaders of political and social change at the grassroots level and faculty members and administrators at universities, Kezar et al. (Reference Kezar, Gallant and Lester2011) show the applicability of the grassroots leadership framework to academia.

Grassroots leaders in academia are most widely conceptualised as tempered radicals who operate within an organisation, as opposed to social and political grassroots leaders who are active outside organisational settings (Meyerson Reference Meyerson2003). Regardless of whether they work in grassroots leadership teams or as individual grassroots leaders, they are loyal to the overall norms, values and mission of their institution but at the same time challenge established practices because their ideas are fundamentally different from the dominant culture of their organisation (Meyerson and Scully Reference Meyerson and Scully1995; Lester and Kezar Reference Lester and Kezar2012; Kezar Reference Kezar2010b). They are in “leadership roles because of a passion for a cause or an issue” (Davidson and Hughes Reference Davidson, Hughes and English2022: 336).

Since their employment depends on people whose values they are challenging and since losing their job also means losing their influence, organisational grassroots leaders typically use subtle, underground or invisible tactics, as opposed to societal grassroots leaders who primarily rely upon confrontational and high-visibility actions like rallies, sit-ins and other forms of high-profile protest. Tempered radicals are often opportunistic in their efforts and build “on the cumulative effect of incremental actions” (Kezar Reference Kezar2010b). Therefore, “it takes longer, requires unique skills and strategies […] and involves more personal resiliency and commitment” for them to effect change than for formal leaders who work top-down (Kezar Reference Kezar2010a: 85). Often, they pursue their activism in connection with their educational role, which has been found particularly effective in bringing about curricular changes (Kezar Reference Kezar2010b; Goldfien and Badway Reference Goldfien and Badway2015).

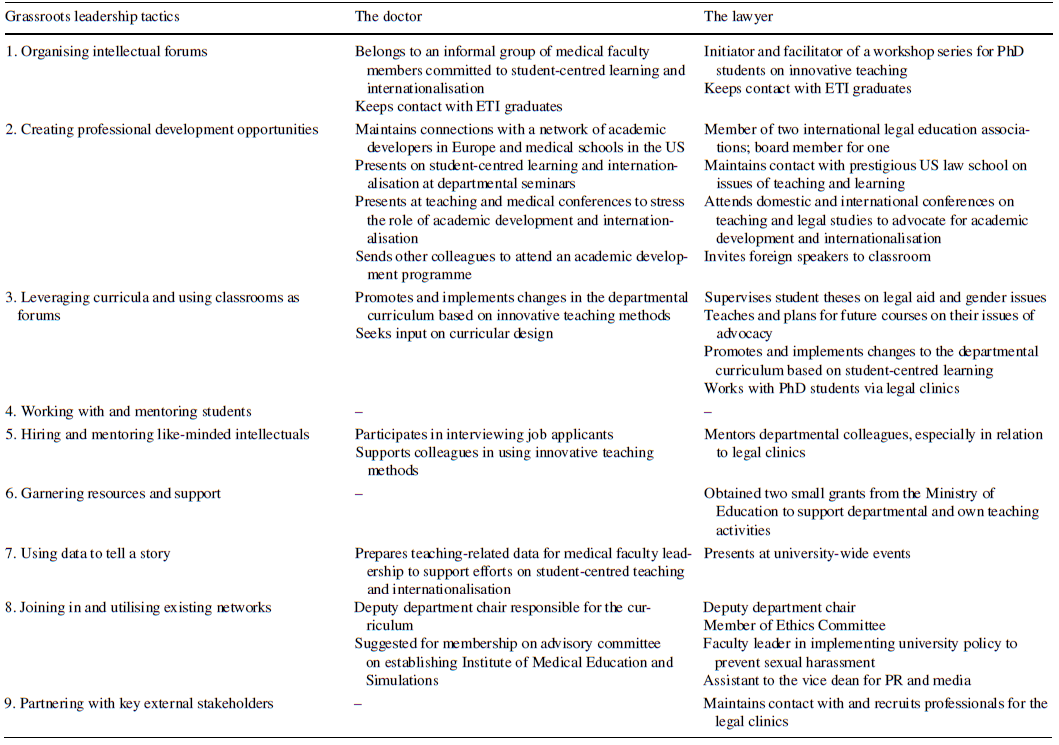

Kezar et al. (Reference Kezar, Gallant and Lester2011) identifies nine tactics by which individuals inside an institution quietly and persistently work within academic culture. (1) Organising intellectual forums is a tactic that requires continued and repeated efforts—e.g. lecture series, discussion forums, luncheon groups—to inform and connect faculty interested in the same goals. (2) Creating professional development opportunities implies connecting with and obtaining support from like-minded individuals on and off campus to help grassroots leaders educate themselves and maintain their commitment (see also Kezar and Lester Reference Kezar and Lester2009). As an outgrowth of their educational activities, grassroots leaders in a university setting (3) leverage the curriculum and use their classrooms as advocacy forums by influencing students and changing the curriculum and/or (4) work with and mentor students outside the classroom, including advising student clubs and initiatives (Kezar Reference Kezar2010b). Some grassroots leaders exercise their informal power by (5) advocating for hiring and mentoring like-minded social activists. Since grassroots initiatives are expected to succeed in the long run and practical support within the organisation is unlikely, to fund the activities grassroots leaders (6) garner resources and support via external grants (Kezar and Lester Reference Kezar and Lester2009). As researchers, faculty members (7) use data to tell a story in order to educate and recruit support on campus. Once recognition on campus is gained and the more subtle approaches are exhausted, a meaningful tactic is (8) joining in and utilising existing networks on campus through, for instance, committee membership. Finally, (9) partnering with key external stakeholders—such as alumni, local politicians or the local community—allows grassroots leaders to exert influence on university leadership with the help of these actors.

Faculty grassroots leaders need not employ all the above tactics. They may use certain tactics and do so with varying emphasis to best match their goals, institutional context and personal disposition (Kezar Reference Kezar2010a). This leads to variations in how tempered their activities are, and thus, in their overall strategies.

Research methods

We used the case study method to investigate how participants transferred the individual level impact of an academic development programme to the meso level by acting as grassroots leaders. Because the focus of the academic grassroots leadership framework is at the institutional (university) level—rather than at the level of the educational system—we define the meso level as the academic department of the grassroots leaders (cf. Roxå and Mårtensson Reference Roxå, Mårtensson, Simon and Pleschová2013). Our case study concentrates on two graduates of the ETI programme. We selected them from among the programme participants by reviewing their CVs for teaching experience and activism and by monitoring the activities of all the programme graduates during the two-year run of the programme and the first six months after its completion. To limit the variations in the larger institutional context, we selected individuals who both work at Comenius University Bratislava, which is the largest and most highly ranked university in Slovakia, known for its focus on research (Times Higher Education 2023). While certain quality assurance policies have been introduced related to teaching and internationalisation, the university lacks a long-term strategy and systematic efforts in these areas. In contrast, both programme graduates work in micro-environments supportive of the enhancement of teaching and learning. Furthermore, both are highly motivated and experienced teachers and committed to exploring new ways of teaching and learning. They are responsible for the organisation and quality of teaching in foundational and/or team-taught courses considered central to their departments’ activities. Finally, both accumulated significant learning and teaching experience abroad—in the UK and USA—at leading institutions in their disciplines, as well as through attending numerous international conferences. Hence, the selected candidates not only fit the characteristics of grassroots leaders but also have a vision of international(ised) education.

Despite these similarities between the two academics, notable differences in their work environments signal that their influence as grassroots leaders in internationalisation and active learning is not merely the result of a unique departmental culture. They work in different fields—one teaches medicine and the other law. While the programme graduate affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine—hereafter, referred to as the doctor—works in a relatively large department of more than twenty academics, the graduate affiliated with the Faculty of Law—whom we henceforth refer to as the lawyer—works in a small department that includes less than five academic and administrative staff members. They also belong to different generations and differ in the length of their teaching career: the doctor is a senior faculty member having taught for about twenty years while the lawyer is junior faculty with less than ten years of teaching.

We conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with the above two ETI programme graduate faculty members in February 2023, i.e. seven months after their graduation. We augmented these with similar interviews with the superiors of the programme graduates, who are in unique positions to provide insights about the doctor’s and the lawyer’s work and activism, having known them for about fifteen and ten years, respectively, in a professional capacity. Both serve as the heads of the departments in which the programme graduates have been employed.

We developed and followed interview protocols, which focused on the programme graduates’ roles within their respective departments. The protocols addressed the nine grassroots leadership tactics identified by Kezar et al. (Reference Kezar, Gallant and Lester2011) when inquiring about the activities through which the doctor and the lawyer influence their teaching and learning environment. To minimise the chance of socially desired responses, the interviews with the programme graduates were conducted by a scholar not involved in this research but familiar with both the programme and the grassroots leadership framework. These interviews lasted, on average, for seventy-five minutes. The interviews with the superiors took about half an hour each and were done by the authors. The language of communication was English, which all interviewees spoke fluently. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by the automatic feature of MS Teams software. After the transcripts were checked for accuracy, we independently read all four transcripts to identify any activities falling within the grassroots leadership framework and aimed at influencing teaching and learning in general and internationalisation in particular. Where information was incomplete or unclear, the interviewees were contacted for clarification via email. All quotations in the analysis below come from the interviews.

Two grassroots leaders, two leadership styles

Single-issue grassroots leadership

The doctor is singularly passionate about the betterment of the education of medical students. Their activism has long been pursued by being involved with colleagues’ initiatives, joining together with colleagues in order to achieve mutually shared goals, and pursing initiatives in various areas to advocate for what they call “modernising medical education” in their department to meet the standards of internationally reputed Universities. Since the department committed to innovating medical education about ten years ago at the initiative of a colleague, the doctor has been an enthusiastic supporter of and participant in seeking new active learning methods. These efforts were based on importing and adapting medicine-specific teaching methods—e.g. artificial labs, medical simulation exercises—and more general teaching techniques—like team-based learning—and teaching materials from the USA. Visiting Fulbright scholars added to the education of the faculty by training them how to implement student-centred methods. The doctor has been cooperating with American institutions in bringing innovative methods to teaching medicine at Comenius University Bratislava ever since.

Once the doctor became the deputy department chair, they took a more visible grassroots leadership role. They “have quite a lot of opportunities to introduce innovations” in teaching, especially since the department chair is open to and supportive of their recommendations. Although the doctor has some power to change what and how is taught in the department, they seek to achieve buy-in by their colleagues through educating and mentoring fellow faculty members. They have contributed to the regular departmental seminars by presenting on student-centred learning methods, prepared educational material for colleagues about team-based learning, and guided new colleagues unfamiliar with the teaching methods used in the department. For many years, they supported—although did not initiate—attempts to establish the Institute of Medical Education and Simulations, which started its work in 2023.

Participating in the ETI programme helped the doctor find their own niche within the modernisation of the department’s teaching and learning. Indeed, the doctor feels that “there was an era before the [ETI] programme and now we have an era after the programme”. They have not only presented to their colleagues about the merits of internationalising medical education and peer learning, but have remained a fierce advocate ever since: as their superior noted, they “mention internationalisation at every single seminar we have”. They have become sensitised to the needs of international students, arguing that dismantling the strict separation of local and international students would be advantageous for learning. Indeed, they began to draw students in to curricular design by systematically seeking the students’ perspective about the effectiveness of new methods of teaching. They also temper student activism; when students “are pushing for changes, [the doctor acts] as a mediator because some changes cannot be implemented as quickly and in the way the students think” is best. In addition to internationalisation, the doctor has increased their efforts to advocate for a more systematic and evidence-based approach to education, even turning to new tactics. Thanks to their encouragement and support, three other colleagues in the department have participated in academic development programmes at the university.

As the pioneering department in modernising education at the Faculty of Medicine, the doctor and their colleagues strived to share their knowledge with faculty members from other departments but their efforts were curtailed mainly for financial reasons. Most recently, the doctor was named a member of the Working group of theoretical institutes of the Faculty of Medicine for innovations in teaching, which indicates institutional willingness to support good teaching. Additionally, the doctor thinks that “there are plenty of good things I can do here at our [department] and I did not have the courage to go out and to speak […] to a broader audience of other colleagues here at the university”. They say that “if I talk to my direct superior it results in some activity. But talking to the vice dean […] did not have an outcome in change”. Nonetheless, the doctor has prepared and presented data to the vice dean on a few occasions—e.g. about team-based learning, online education during the COVID-19 pandemic and most recently internationalisation—with the expectation that the vice dean shares it with the rest of the faculty leadership. It is unclear, however, whether or not the latter actually happened. The higher-level leadership tend to offer moral support—for example, the vice dean acknowledged the merit of the doctor’s suggestion to standardise syllabi across the faculty—but rarely monetary or other assistance.

The doctor has become more visibly active in seeking a supportive environment externally. At the university, they joined the ENLIGHT project, which puts them in contact with fellow education enthusiasts through a network of ten European Universities. Furthermore, since being involved with the ETI programme they have given presentations about their internationalising efforts at two academic development conferences and at a medical conference. On the other hand—and despite financial difficulties that limit transitioning to a modern, student-centred medical education within both the doctor’s department and the Faculty of Medicine—the doctor has not sought out funding externally. Although they did acknowledge the benefits of grant projects such as ENLIGHT and the Going Global initiative—which has funded their effort to put together a brochure for colleagues on team-based learning—they feel they personally lack capacity to attract external money.

Overall, we see the doctor as a grassroots leader with a very strong focus on the singular issue of promoting quality teaching and internationalisation in medical education. Their efforts have often been pursued in unison with departmental colleagues to achieve their shared goals with considerable success. The doctor has established their own initiatives in support of and in harmony with these efforts through, for example, departmental seminar presentations focusing on teaching rather than research as most of their colleagues do, as well as data collection, preparing educational material for colleagues and students and cooperation with like-minded individuals in the USA. They have emerged as a prominent proponent of student-centred learning, influencing and implementing significant changes in the curriculum. More importantly for this study, as a result of the ETI programme, the doctor identified internationalisation as a novel area for their activism and immediately took initiative in it.

Multifaceted grassroots leadership

The lawyer is involved with three different issues: legal aid, gender equality and student-centred learning. Their activism is intertwined in these areas and it is difficult to speak about one without the others. Hence, despite the focus of our research on matters of teaching and learning, the lawyer’s activism in this area cannot be discussed in isolation.

Indeed, the lawyer’s interest in moving away from frontal lecturing towards active learning methods originated in their involvement with legal aid provision through legal clinics. Legal clinics provide law students with hands-on experience, which is rare in legal education in this region of Europe, where frontal lecturing remains the prevalent method of instruction. The lawyer participated in the clinics as an undergraduate student and later, as a doctoral candidate, contributed to running them. Today, the lawyer is responsible for managing the legal clinics, including coordinating PhD candidates, and maintaining and building relations with lawyers who contribute to the clinics’ operations. Their experience with the legal clinics, and the methods of education pursued in them, made a strong impression on the lawyer from the beginning. With encouragement from their current department chair they introduced active learning across the curriculum, as this small, tight-knit department has become committed to student-centred methods of teaching and learning.

The lawyer also works as a mentor for students and supervises student theses in gender equality and legal aid. With a colleague, they organise workshops on teaching methods for PhD candidates, whose contribution to the educational activities in the department is essential. The workshops focus on diverse approaches to student-centred learning including the recent addition of peer learning and internationalisation. Furthermore, the lawyer invites international academics to talk to their classes—often online—which are open to other legal studies students, too.

The dean of the Faculty of Law has acknowledged the pioneering role of the department in active learning and encouraged them to share their knowledge and initiate a teaching methods course for colleagues at the faculty. However, the lawyer is also involved with another department as a teacher, which discouraged them: “it is very difficult because younger teachers or teachers who are already interested in it, they already […] teach in this […] student-centred way and then we have all their colleagues who would never change the way they are teaching”. As of now, the lawyer does not “feel that I’m already in a position that I could try to influence the way how my […] colleagues are teaching” but thinks that “we will do something in the future”.

Nonetheless, the lawyer and their like-minded colleagues receive from the university only moral support and encouragement for their endeavours to better the learning of their students. They secured two small grants from the Slovak Ministry of Education: one to support the legal clinics and the other to finance their teaching activism, including visiting partner universities abroad and attending conferences. They plan to attract money through larger European and international grants in the future.

Similarly to the doctor, internationalisation prior to attending the ETI programme had been understood by the lawyer and their departmental colleagues as importing ideas that worked abroad to Comenius University Bratislava (Engwall and Kipping Reference Engwall, Kipping, Tsang, Kazeroony and Ellis2013). Lacking opportunities for training or access to local resources left them with no other option than to turn to scholarship and external experts on legal education. The lawyer sought out professional opportunities to improve their teaching and, thus, expanded their networks by joining two European associations for legal education. In one of them, the lawyer’s ongoing activism resulted in them being selected as a board member. Furthermore, the lawyer seeks out contacts at and maintains a network with prestigious law schools in the USA in order to learn innovative teaching methods from them. They spent a semester in the USA, which they found a transformative experience.

It was the visit to the USA that raised the lawyer’s interest in gender equality. On their return, they took the opportunity to speak at the faculty-wide lecture series about the importance of gender equality and sexual harassment. It started an avalanche of events including people contacting the lawyer to share their experience of sexual harassment and demanding continued discussions on gender equality. The lawyer is an active member of the faculty’s Ethics Committee, which has become much more active in these issues, and was entrusted with a leadership role in the implementation of the university’s newly adopted Gender Equality Plan.

The lawyer also regularly attends and presents at conferences on legal education and seeks out other opportunities on campus or elsewhere to speak about the issues they are passionate about. This includes presenting their scholarship on teaching and learning study, which investigates the impact of internationalisation and peer learning in the course that they newly designed as part of the ETI programme.

Attending the ETI programme helped the lawyer acknowledge the needs of international students and identify areas, where future activism is needed. On the one hand, the newly designed course successfully integrated the needs of international students, which resulted in an increased interest among these students after its first successful run: the number of students in the course increased from five to twenty-six from the first year to the second. Encouraged by these outcomes, the lawyer is considering designing and offering another course in English. Furthermore, they discovered that while tuition-paying international students are actively recruited, there are no sufficient mechanisms to create a supportive environment for them. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the lack of (sufficient) communication with international students: for example, international students were clueless when their courses switched from face-to-face to online delivery. The course evaluation form used by the university leadership is not available in any language other than Slovak, which the lawyer remedies by administering the form provided by the ETI programme when teaching a class of international students.

All in all, the multifaceted nature of the lawyer’s grassroots leadership creates an intriguing linkage of issues. They can use an opening in one issue area to advocate for another. The ETI programme not only helped them think more holistically about teaching methods but also added internationalisation to their already multifaceted agenda.

Grassroots leadership in a non-American context

Grassroots leaders at Central European public universities—like Comenius University Bratislava—are somewhat differently positioned than faculty members in the USA, whose activities were used to develop the grassroots leadership framework in higher education. The institutional context in Central Europe tends to be more hierarchical, and relationships between colleagues especially between faculty and students being more formal. Universities are embedded in their local community differently—they are less focused on the community and more vulnerable to political influence due to being almost exclusively state funded. The European Union offers many opportunities—e.g. faculty and student exchanges, grant schemes—but its efforts to standardise education across Europe also serves as a limit on curricular flexibility. Yet, faculty members enjoy substantial academic freedom, which has allowed both the doctor and the lawyer to employ the wide variety of grassroots leadership tactics summarised in Table 1. However, what is important is not only which tactics they use, but also how and to what extent they rely on each of these tactics.

Table 1 The activism of the two programme graduates, organised according to the categories of grassroots leadership tactics in the academia

Given the major themes of their efforts—internationalisation and academic development—it is natural that both ETI programme graduates employ tactics well suited to effect changes in the curriculum and pedagogical methods. In this, intellectual forums, but especially creating professional development opportunities for themselves and for their departmental colleagues, play a prominent role. Networking with like-minded colleagues in Europe and the USA serves as a major source of information and inspiration for pursing their goals. Their activism has elevated them to positions that allow them not only to change but also to leverage the curriculum to promote their initiatives. Indeed, becoming deputy chairs of their respective departments indicates that they successfully communicated their visions to their departmental colleagues and chairs to gain their recognition and endorsement.

Our primary interest in the meso level and the clear boundaries of departmental work mean that within this space the practice of utilising existing networks by joining university committees is not relevant, but the idea of joining formal power structures at lower levels is. The precondition of joining in is not rooted in gaining recognition and respect through informal networks, as Kezar et al. (Reference Kezar, Gallant and Lester2011) suggest, but in the work ethic and effectiveness of the two ETI programme graduates. Their superiors talked about them in the highest regard during the interviews. For example, the doctor was praised for “always looking for the new ways how to do things better” and being “able to influence the others from the department by motivating them, convincing them step-by-step instead of pressuring them”, whereas the lawyer was commended because they “can do so much and still be very good and responsible in the details; [they…] really use these methods that [they…] have gotten familiar with” during the ETI programme.

Students also notice the impact on their learning. The doctor’s superior noted how “The new methods […] are appreciated by the students. […] It makes the classes more lively. The students can share their opinions, their ideas and they would say that […] they learned a lot”. Meanwhile the lawyer’s superior emphasised that the lawyer’s “teaching methods are more interactive” and “the majority of the students react very positively towards this method because it’s something different”. An “important part of the way [the lawyer] teaches is that [they] really use these methods […] but [… they are also a] very positive person [and] if the teaching itself is positive and the students have a good experience, they are likely to remember more”. As a result, both the doctor and the lawyer have gained respect in their departments, and thus garnered sufficient levels of trust—which is an important vehicle of influence for grassroots leaders—among immediate supervisors and colleagues to integrate internationalisation and a more evidence-based approach seamlessly to student-centred learning into their grassroots initiatives (Davidson and Hughes Reference Davidson, Hughes and English2022).

While the activism of the doctor and the lawyer within their departments has been rather vocal and visible from the beginning, their efforts have extended beyond the meso level only subtly and cautiously. On occasion, they do gain visibility by speaking at university-wide events—which proved especially effective for the lawyer in promoting gender equality—but they prefer a more tempered approach, working in the background. For example, the doctor regularly funnels data to the vice dean to demonstrate the benefits of student-centred learning, peer learning and internationalisation. Both ETI programme graduates, however, resist becoming high-profile advocates at the faculty level not because, as the tempered radicals approach would suggest, they fear for their jobs. After all, they were both encouraged by their respective vice deans to hold teaching methods training for colleagues at their faculties. Rather, it is the perceived futility of such training due to resistant colleagues or financial unsustainability, as well as gaining notoriety among their colleagues for their commitment to innovative teaching, that make them hold back on their activism.

Even though not all tactics need to be used by grassroots leaders, it is not a coincidence that there are tactics that neither the doctor nor the lawyer employed. First, despite most of their grassroots activities being rooted in their roles as teachers and researchers, it is particularly notable that neither the doctor nor the lawyer reported on their advising of individual students, student initiatives or clubs. However, it is not for lack of interest in working with students, but lack of opportunity. Student organisations at Central European Universities are much rarer and weaker than those in the USA. The organisations that exist have limited relevance for teaching and do not often work with faculty advisors. In fact, they tend to be disconnected from the faculty as they are rarely of educational value—unlike the Model UN, debate clubs or moot courts in the USA—and the demarcation lines between students and faculty are culturally stronger. While protests by university students in response to some educational directive or government policy are not unheard of, they are also rare. As a result, teachers’ work with students is done within the classroom, in relation to curriculum development, or is targeted towards PhD candidates, who are typically seen as students—and not as colleagues—in this region.

Second, contributing to decision making on hiring faculty members is not common. The lawyer only learnt about the hiring of a new colleague after the colleague showed up. The doctor does participate in interviewing job candidates, however, they acknowledged that “the teaching and learning methods are only one factor when we hire a person” and that the department is seeking candidates who are both good researchers and willing to be good teachers. Decisions about hiring are less transparent, more centralised and nepotistic at public universities in Central Europe than in the USA. Therefore, grassroots activism concentrates on mentoring colleagues who are often at the beginning of their teaching career.

Third, turning to external stakeholders with the intent to influence university leadership is also futile. Neither at the departmental nor at other levels are universities effective in maintaining a relationship with their alumni, and alumni are much less emotionally attached to their alma mater than in the US. As a result, alumni typically do not make notable financial contributions to support the university and generally stay away from the university. Academics also closely guard the intellectual independence of their university, and thus, seeking out support among politicians is not favoured. Only the lawyer has contacted external stakeholders, and these legal experts are most interested in supporting the quality of education by making their own contributions to the legal clinics, and are not involved with influencing university policy.

Fourth, looking for external funding is a relatively new phenomenon. Public Universities are state-owned and funded. Senior scholars have learnt to accept and navigate around the limitations imposed by insufficient state funding. Younger academics are more inclined to seek grant money, but they often lack the experience and achievements that could bring larger sums to the university. The lawyer has obtained or was part of a team receiving small funds but is yet to establish the reputation and make achievements that attract bigger grants. More importantly, grants require the capacity and willingness to administer them, which is time-consuming with limited support from the university. The lack of funds also influences the grassroots tactics employed; while ad hoc professional development or intellectual forums can be organised and informal networks of faculty members can be maintained by volunteering, regular events are difficult to sustain. Even though both the lawyer and the doctor emphasised the importance of being enthusiastic in order to be effective grassroots leaders, few initiatives that have required sustained effort or funding came to fruition, e.g. the establishment of the Institute of Medical Education and Simulations, faculty level advocacy or training.

Nonetheless, it is notable how both grassroots leaders have concentrated their efforts at the meso level. In spite of their differing grassroots leadership tactics and strategies, each of them has been successful within their department in furthering their individual agenda(s). They do attempt to reach out to and influence higher institutional levels, but their efforts have brought only mixed results. The lawyer is somewhat more successful in exerting influence at higher levels, but in the matter of gender equality rather than teaching and learning. Difficulties in reaching higher institutional levels may also reflect the more hierarchical nature of academia in this region.

Attending the ETI programme influenced not only their conceptualisation of internationalisation, their approach to teaching and learning, but also their activism. Both programme graduates moved away from seeing internationalisation as introducing new teaching methods to either legal or medical education because they are successfully used abroad to a more comprehensive view of student-centred learning, a more conscious adaptation of teaching methods, and consideration of the needs of international (and home) students. They both added internationalisation and peer learning to their agendas.

Conclusion

In this article, we showed how two grassroots leaders who participated in an academic development programme channelled the programme’s objectives—in this case, internationalisation and student-centred learning—into their own commitments and initiatives within their departments. Participants meeting the programme objectives of Effective teaching for internationalisation at the individual level (Simon and Pleschová 2022) was a necessary condition for grassroots leadership. As we demonstrated, the two grassroots leader participants of the ETI programme did not simply incorporate internationalisation into their thinking and practice but also included it among their grassroots leadership objectives. With this, they helped the programme impact extend beyond the individual level. We identified two distinct meso level strategies—the single-issue and the multifaceted—of grassroots leadership based on the focus of their activities and how they use the grassroots leadership tactics synthesised by Kezar et al. (Reference Kezar, Gallant and Lester2011). Both strategies are effective in exerting influence at the meso level in the short run and making some inroads beyond the meso level. Grassroots leadership at this Central European research university closely resemble those used in a conservative, hierarchical research university in the USA, where working with students also “focused narrowly around curricular and co-curricular events” and where faculty activism was closer to the most tempered end of the scale, confirming the importance of the institutional context (Kezar Reference Kezar2010b).

Our findings also demonstrate that the common conceptualisation that participants in academic development programmes are blank slates needs to be reconsidered. It is likely that there are important differences in the levels of interest in and commitment to teaching and learning and achievements in this area between those who enrol and those who decide not to take advantage of these opportunities. The ETI programme expanded the knowledge of its graduates about internationalisation and student-centred learning, but the doctor and the lawyer had already been active in advocating for student-centred teaching methods prior to participating in the programme. They were grassroots leaders before they enrolled in the programme; what the programme achieved was refocusing, extending and strengthening their grassroots activities. The lawyer expanded their already multifaceted activism with internationalisation, while internationalisation offered a niche for the doctor and an impetus to take individual initiative. Both were able to integrate their new knowledge about issues of teaching and learning and internationalisation with their activism, even before graduating from the programme. This suggests that to make an impact on the meso level in the short run, programmes that aim to influence internationalisation need to recruit experienced and activist faculty members. Even if they enrol in small numbers, their immediate potential to influence departmental practices is much higher than that of PhD candidates. Doctoral candidates, on the other hand, are more receptive to new ideas, and thus more likely to sign up for the programme, but their influence will likely only reach the institutional level in the long run, if at all. After all, there are no guarantees that they will become grassroots leaders.

Nonetheless, the limitations of these findings should be acknowledged. Using two individuals for our case study does not allow for either understanding how common these strategies are or if there are other strategies used by grassroots leaders at Central European Universities. Moreover, this article focused on the specific case of how grassroots leader participants of an educational development programme spread the influence of the programme to the meso level rather than seeking a general understanding of regional grassroots leadership activities and strategies in the academia or looking at the wider institutional level. Therefore, in addition to working with a larger number of cases, future research should further explore how grassroots leadership fosters change in academia in the region, including the variety of strategies used, their effectiveness, and long-term outcomes, to learn if, with time, their strategies have achieved wider institutional influence.

Acknowledgements

The professional development programme ‘Effective Teaching for Internationalisation’ was offered in the framework of the international collaborative Erasmus+ project IMPACT, No. 2019-1-SK01-KA203-060671, co-funded by the European Commission.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic in cooperation with Centre for Scientific and Technical Information of the Slovak Republic.