THE MEXICAN AND NORTHWEST MEXICAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT

In Mexico, cultural heritage belongs to all Mexicans, and the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) is the federal institution in charge of safeguarding archaeology. The idea of a Mexican Nation and the role of the state are crucial to understanding the management of Mexican cultural heritage. In contrast, in the United States, Native Americans are recognized as descendant communities and consulted on projects that are federally funded or permitted. We acknowledge that Mexico and the United States have very different colonial histories, identity discourses, notions of territorial ownership (Indian reservations in 1851 versus communal land regime ejidos in 1915), and laws. Nevertheless, it is crucial that we develop Mexican legislation for allowing Indigenous participation, practice responsible ethical research, and become effective stewards of their archaeological remains and heritage in general. Although we are all Mexicans, we cannot assume to have equal rights to our heritage in such a culturally diverse country.

Mexican anthropologists such as Manuel Gamio, Alfonso Caso, and Carlos Navarrete studied the interrelation between Indigenous people and archaeological practice. However, due to a positivist approach and arguments against the politicization of archaeological practice, clear links and procedures have not yet been established among archaeological projects with and for Indigenous communities to develop archaeological past reconstructions that are relevant for Indigenous people today (e.g., Mendiola Reference Mendiola2008; Navarrete Cáceres Reference Cáceres and Carlos1978). In consideration of North Mexican archaeology, Mendiola (Reference Mendiola2008) highlights the need to integrate Indigenous people with archaeology, not only to demonstrate respect but also to defend their identities, cultures, and territories. Consequently, archaeologists should realize their role not only in scientific documentation but also in relation to the cultural heritage practices that result from their research (especially archaeologists working at universities believing that cultural heritage is only the responsibility of INAH).

Navarrete Linares (Reference Navarrete Linares and Castro2009) rightfully describes the Museo Nacional de Antropología as one of the most important places in the Americas for the protection and exhibition of archaeological and ethnographic objects—and, therefore, a place of pride for many Mexicans. However, it is rarely recognized that many of the collected objects were part of local rituals and taken without permission from Indigenous communities. Nevertheless, since 1985, INAH has promoted the development of community museums in favor of local needs and interests. The state of Oaxaca was the pioneer, with the Santa Ana del Valle and the Shan-Dany museums. Today, this state has 18 community museums and there are more than 50 community museums in Mexico safeguarding various archaeological and historical objects, alongside their heritage, memory, and identity. (Morales Lersch and Camarena Ocampo Reference Teresa and Ocampo2005:74). Additionally, artifact collectors from non-Indigenous descendant communities who are interested in the local cultural heritage can, under the Federal Law of Monuments and Archaeological Sites of 1972, apply for a concession to keep archaeological artifacts if they know their origin and register their collections in the Dirección de Registro Público under their Sistema Único de Registro Público (SURP; Cottom Reference Cottom2008:273–274).

Many Mexican archaeologists (mostly Mesoamerican) assume that all artifact collectors are looters who destroy sites, excavate tombs, and commercialize objects. However, in the northwestern part of the country, diverse members of the community collect artifacts because they are genuinely interested in history and their heritage. Furthermore, for some Mesoamerican monumental sites, the cultural affiliation of past residents may be complex, because several Indigenous groups and communities have connections to the same place. In Northwest Mexico, relationships with the archaeological past are more straightforward (e.g., Kennedy Reference Kennedy1983; Levi Reference Levi1998; Mendiola Reference Mendiola2008). In most cases, even though they have lost much of their homeland territories, they relate to the ancestral landscape through long-term continuity. They have retained knowledge of their cultural landscape and a deep connection with the archaeological record. They also possess a rich oral tradition and complex views of the natural order expressed in stories, poetry, and songs (e.g., Martínez-Tagüeña and Torres Cubillas Reference Martínez-Tagüeña and Torres Cubillas2018).

THE SONORAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITUATION

As is the case with many federally managed resources, local realities vary and make policies difficult to comply with. In Mexico, the federal agency INAH has placed more emphasis on Mesoamerican monumental sites. For example, site registration forms and the promoted methodologies apply only to this type of sites and do not consider the types of archaeological sites formed by hunter-gatherers in the northern part of the country. Furthermore, although INAH's budget is limited, Mexican federal funding for archaeological research in Northern Mexico, for Sonora in particular, is minimal. Less than 1% of the total INAH budget is designated for Sonora, although this state encompasses 11% of the Mexican territory. Finally, this is also demonstrated in the ratio of archaeology being studied, where approximately 99% of the career archaeologists in Mexico study monumental sites, whereas only 1% of the professional archaeologists study hunter-gatherer sites (Moises Valades, personal communication 2022).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were between 15 and 20 archaeologists working full time in the dimension of the Sonoran State to 179,354.7 km2 (Figure 1). By comparison, in the neighboring state of Arizona in the United States, there are 1,500 archaeologists employed full time (Jim Watson, personal communication 2021). For reference, Sonora encompasses an area of 184,933 km2, and Arizona is about 40% larger, encompassing 295,253 km2. Therefore, in Arizona, there is one archaeologist for every 196 km2, whereas in Sonora, there is one for every 1,233 km2. Moreover, Sonora has only 3,500 registered sites (Site Catalogue Office, INAH Sonora), whereas Arizona has more than 62,000 sites (James Watson, personal communication 2021). The shortage of archaeologists and funding calls even more for an inclusive, participatory archaeology with Sonoran community members as a fundamental practice for knowledge enhancement and cultural heritage stewardship.

FIGURE 1. Location of Hermosillo City and Comcaac Territory in Sonora, Mexico. (Created by Guadalupe Sánchez.)

In Sonora, it is possible to practice community archaeology in the diverse territories where indigenous communities are the clear descendants of the archaeological past. Furthermore, for at least 70 years in the city of Hermosillo, there have been various collectors of projectile points who are well-known honorary members of the community. They see this practice of going to the desert and connecting with their history as a weekend hobby. In relation to local community museums, the Museo y Sitio Arqueológico del Cerro de Trincheras is one of the two local site museums in the state. Although the local population is not indigenous, it is part of the project and connected to its heritage. For the last 15 years, Elisa Villalpando, a researcher from Centro INAH Sonora, and her group have made the visitor center and the archaeological site more than a touristic option; they have become part of the identity of the people from the Trincheras town. Therefore, for both visitors and the local population of all ages, it is a space for meeting and reflecting on diverse topics—where activities are offered to promote the need to preserve this cultural heritage while acquiring a greater knowledge of the past—and it instills a sense of pride and enjoyment (Villalpando Reference Canchola and Elisa2014). We applaud this gigantic effort by Villalpando, and we believe this successful initiative should be replicated in other places of Northwest Mexico.

FROM ETHNOARCHAEOLOGY TO COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY

Ethnoarchaeology, understood as the ethnographic study of living cultures from archaeological perspectives with the recognition of the value for gathering traditional knowledge for archaeological interpretation and analogy (David and Kramer Reference David and Kramer2001), is a common practice in Mexico. Much less common, however, are archaeological-oriented studies that include the living communities whose ancestors we are trying to study, through partnerships in which all stages of research, dissemination, and protection are developed jointly. We have learned from ample examples of Indigenous and community archaeology to develop participatory projects that transcend mere consultation models so that the various stakeholding publics become actively involved in the planning and execution of mutually beneficial archaeology projects. The processes of inclusion and trust building, honest and respectful discussion, and cooperation between community members and archaeologists will lead to a more insightful and accurate pursuit of the past through coproduction of knowledge (Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson2008; Colwell-Chanthaphonh et al. Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Ferguson, Lippert, McGuire, Nicholas, Watkins and Zimmerman2010; Watkins Reference Watkins2000).

Furthermore, collaborative endeavors establish new kinds of interpretative frameworks with new ways to translate the patterns of material culture (Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson2008). Some theoretical advances focus on material objects and cultural landscapes, along with their sensory, embodied, and mnemonic properties (Hamilakis and Anagnostopoulos Reference Hamilakis and Anagnostopoulos2009:73). It is also necessary to develop adequate methodologies for knowledge production, dissemination, and safeguarding. Overall, this type of research contributes to building a discipline of anthropology that blurs subdisciplinary boundaries. In addition to ethnographic and, on a few occasions, linguistic data, archaeologists should integrate other sources of past narratives—such as oral history and tradition and documentary history—into explanatory models to interpret human behavior. In some countries, including Mexico, archaeological knowledge is a privileged form of expertise occupying a role in the governance of cultural heritage and the regulation of national identity. The objectivity discourse that frames archaeological knowledge can and does have a direct impact on people's sense of cultural identity and has been a point of contention for a range of interests. Conflict between Indigenous people and archaeology needs to be considered in a context that exposes not only the privileged position of archaeological discourse but also how this discourse has come to be privileged (Smith Reference Smith2004). The same concern has been eloquently stated for the discipline of ethnohistory (Galloway Reference Galloway2006).

Therefore, as has been suggested by the SAA code of ethics (Pitblado Reference Pitblado2014), we need to make a stronger effort to expand and strengthen such collaborations, not only with Indigenous people but also with local community members—such as artifact collectors—as a fundamental practice for an inclusive archaeology. Importantly, we note that we do not promote or work with collectors who sell artifacts, which greatly affects archaeological knowledge and destroys archaeological heritage (Pitblado et al. Reference Pitblado, Shott, Brosowske, Butler, Cox, Espenshade and Neller2018). Rodríguez Rodríguez and Almaguer Hernandez (Reference Rodríguez, Lidia and Hernández2019) promote the employment of community archaeology for the protection of archaeological heritage in Mexico. They remind us that knowledge of the past enforces cultural identity, and that it should also enhance the understanding of human development and further promote social cohesion of present-day societies. They describe how it has been necessary to understand how local community members perceive and understand their cultural heritage, and to then articulate this vision with the institutional one to develop accurate strategies for its protection. As was mentioned before, community museums in Oaxaca are established, and they developed a methodology that has served as a guide for the creation of other similar initiatives (Morales Lersch and Camarena Ocampo Reference Teresa and Ocampo2005). Following this methodology, other proposals have been designed, such as school museums that seek to bring archaeological knowledge closer to local communities through joint outdoor activities that take place in parks and other open places (for details, see Rodríguez Rodríguez and Almaguer Hernandez Reference Rodríguez, Lidia and Hernández2019).

COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY AND HERITAGE STEWARDSHIP

In Latin America during the 1970s, participatory action research emanated from social movements and processes of policy transformations related to social and education planning (Freire Reference Freire1970). Participatory research requires the fulfillment of a series of methodological procedures to acquire useful knowledge and to eventually induce change in a situation or system through development, conservation, and management plans, to mention a few (e.g., Geilfus Reference Geilfus2002; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Howitt, Cajete, Berkes, Louis and Kliskey2016). This type of research seeks to develop partnerships to coproduce knowledge, recognizing encounters with different cultures, languages, world views, identities, practices, and ethics, in a context of asymmetries of power and rights (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Howitt, Cajete, Berkes, Louis and Kliskey2016). Community archaeology with a participatory research approach promotes multiple stakeholders’ partnerships, which are essential for weaving knowledge systems to not only enhance archaeological and cultural heritage knowledge but also to open dialogue between different cultures, mental models, institutions, actors, and their practices and influences so as to inform governance schemes and policies (based on Tengö et al. Reference Tengö, Hill, Malmer, Raymond, Spierenburg, Danielsen, Elmqvist and Folke2017). Consequently, for research to have real repercussions in the decision- making and formulation of public policies for cultural heritage protection, emphasis should be placed on the importance of the role of institutions and social organizations in each context where individual and social diversity must be considered.

Furthermore, scholarly advances in understanding the relationships between science and society, which describe the importance of crafting knowledge to support action, remark on the importance of “boundary work” through which research communities organize their relations with new science, other sources of knowledge, and action and policymaking (Cash et al. Reference David W., Clark, Alcock and Mitchell2003). Effective boundary work can be achieved through meaningful participation in agenda setting and knowledge production by all involved stakeholders; governance arrangements that assure accountability of the resulting boundary work to relevant stakeholders; and the production of “boundary objects” defined as collaborative products such as concepts, tools, models, maps, or standards that are adaptable to different viewpoints and robust enough to maintain identity across them (in Clark et al. Reference Clark, Tomich, van Noordwijk and McNie2011, based on Star and Griesemer Reference Star and Griesemer1989). Stewardship, defined as a boundary object, is a conceptual tool that enables multiple stakeholders’ collaboration and dialogue bridging research, policy, and practice through three dimensions: care, knowledge, and agency (Enqvist et al. Reference Enqvist, West, Masterson, Jamila, Svedin and Tengö2018). These dimensions are useful for finding pathways for future research and practice. Care refers to values, aesthetic ideals, identity, sense of place, morality, and ideology, among other individual and societal notions. The knowledge dimension refers to the weaving of diverse knowledge systems for deeper understanding of complex systems that interrelate environmental, political, social, economic, and cultural components. Finally, agency refers to the ability of actors (individuals, groups, states) to achieve desired changes through proposed activities. Therefore, many studies are needed to understand how stewardship can be incentivized to achieve multiple stakeholders’ desired outcomes (Enqvist et al. Reference Enqvist, West, Masterson, Jamila, Svedin and Tengö2018; Huber-Sannwald et al. Reference Huber-Sannwald, Martínez-Tagüeña, Espejel, Lucatello, Coppock, Reyes-Gómez, Lucatello, Huber-Sannwald, Espejel and Martínez-Tagüeña2019).

Following these concepts, it is important to use and further develop operational methods and tools to recognize plurality thinking through different perspectives, motivations, and interests to improve stewardship interventions at all phases—from planning to implementation and evaluation (Enqvist et al. Reference Enqvist, West, Masterson, Jamila, Svedin and Tengö2018). Initiatives to promote heritage stewardship are based on reimagining how communities can be more directly involved by being able to map, model, and monitor key buildings and archaeological sites. When communities connect with their heritage, it is more likely to be preserved, and it can also have an economic advantage through tourism revenues, thereby promoting community resilience and social cohesion (e.g., https://www.elrha.org/project-blog/heritage-stewardship-its-place-in-the-humanitarian-landscape/).

The Community Management of Protected Areas for Conser vation (COMPACT) and the UNESCO World Heritage Center have established the engagement of local communities in the Stewardship of World Heritage as one of the five strategic objectives. To accomplish this objective, an innovative model has been proposed and tested at the site level in eight different geographic regions, which is based on a participatory methodology that follows diverse stages. Each project or endeavor begins with defining the team based on gender inclusion and the identification of key stakeholders. Then, the methodology is selected to interweave traditional and scientific knowledge to conduct management and governance problems assessments, along with participatory planning and monitoring of identified key activities and variables. After each stage, an evaluation takes place, and if necessary, adjustments are made accordingly to begin each phase in an iterative manner (Brown and Hay-Edie Reference Brown and Hay-Edie2014).

OUR PILOT PROJECTS

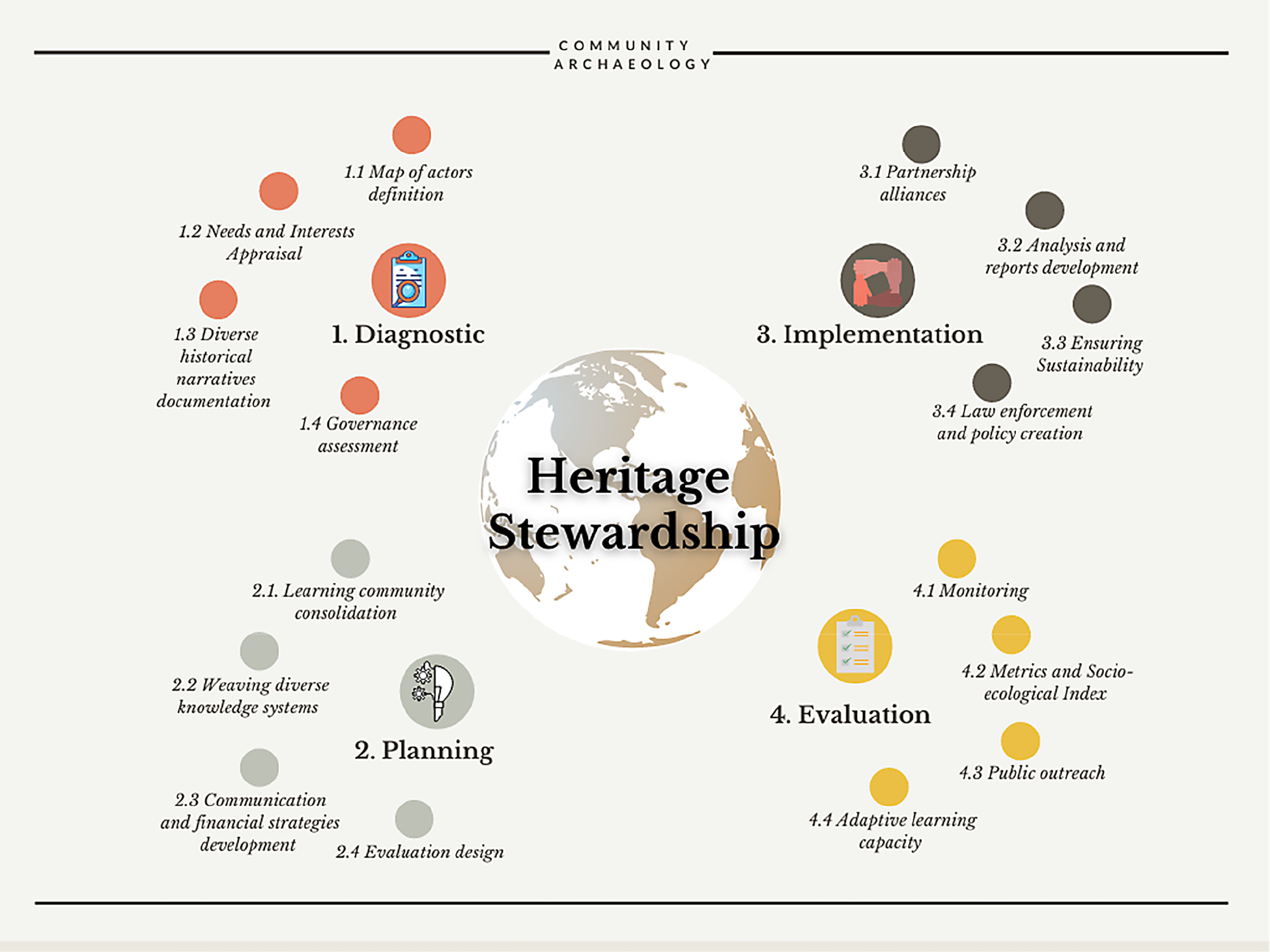

We propose the following operational framework following a participatory methodology that consists of four consecutive phases (diagnostic, planning, implementation, and evaluation) with iterative evaluation after each phase to always verify, adapt, and continue (based on Geilfus Reference Geilfus2002). In each phase, it is important to begin setting specific objectives. Figure 2 is a mental map to explain our proposed objectives for each phase. Then, for each objective, it is important to choose the appropriate participatory tools to successfully accomplish them. There are many published manuals with detailed guidelines on how to choose the appropriate method, and on how to develop them. For us, the main participatory tools employed are participatory workshops, SWOT analysis, participatory cartography, mental models, and rivers of life, among others (see, as examples, Brouwer et al. Reference Brouwer, Woodhill, Hemmati, Verhoosel and van Vugt2015; Chapin et al. Reference Chapin, Lamb and Threlkeld2005; Geilfus Reference Geilfus2002). Although some projects have a short phase for diagnostics, we consider it crucial to take the time to fully understand the socio-environmental context and actors in both the past and the present, as well as to include all the diverse historical narratives. This will set the bases for the consolidation of multiple stakeholders’ teams, called “placed-based learning communities,” that share diverse knowledge and values through horizontal dialogue (Davidson-Hunt and O'Flaherty Reference Davidson-Hunt and Michael O'Flaherty2007).

FIGURE 2. Mental map with our project objectives for heritage stewardship in Northwest Mexican archaeology. (Created by Natalia Martínez-Tagüeña.)

During planning, it is imperative to promote collaborative leadership while establishing communication and financial strategies that can secure the project's longevity. Although INAH is short of funding, archaeologists working there apply for other sources of national and international funding interested in community-based projects. For example, we received an Agnese Nelms Haury Charity Trust Grant, part of which is used for excavation and analysis of artifacts, and another part is used for participatory research activities. Furthermore, we highlight a crucial successful strategy with ample examples in Sonoran archaeology that consists of consolidating collaborative endeavors between INAH members and academics working at universities or other research institutions (national and international) to jointly develop projects to secure diverse sources of funding.

It is also important to include stewardship incentives for the different stakeholders and mechanisms for protection, surveillance, and legal compliance. Once the plan of action is established during the implementation phase, projects such as research, outreach, museums, or tourism can be conducted with formal alliances. All the initiatives must include the registration of archaeological sites and objects in the Dirección de Registro Público, and they need to comply with the federal constitution laws. Finally, during the final evaluation phase, it is important to jointly develop efficient monitoring activities with selected sustainability indicators that include environmental, economic, social, cultural, and political components (e.g., Azar et al. Reference Azar, Holmberg and Lindgren1996). Among the various metrics, the team should consider identity, social cohesion, social entrepreneurism, outreach, and individual and social learning documentation. Effective partnerships require flexibility in perspectives, values, and processes, along with a continuous disposition for adapting and learning.

Engaging with Indigenous Communities

Martínez-Tagüeña (Reference Martínez-Tagüeña2015) developed a collaborative endeavor with the Comcaac community that employs oral tradition (alongside linguistic information), documentary history, and archaeological and ethnographic data to reconstruct a past that is relevant for their present. The Comcaac speak an isolate language called Cmiique Iitom and live in the central part of the Sonoran coast. The Comcaac project meets the community's needs and requests, with the collaboration of various members throughout all stages of research. It employs a materiality framework and a cultural landscape approach, and it specifically contributes to improving theory-based ethnography and our interpretative frameworks to better understand other peoples’ concepts of time and space. Additionally, it promotes the creation of improved methodologies to not only gather and integrate multitemporal data but also to build substantial theory to better understand relationships between people and objects in both the past and the present. Furthermore, these methodologies meet community members’ heritage stewardship preferences for the protection of their objects, places, knowledge, memory, and values, among other crucial Comcaac social practices. It is important to remark that several Comcaac have ample experience with environmental monitoring and have navigated various governance and stewardship challenges, responding in innovative and resilient ways (for more details, see Martínez-Tagüeña and Rentería-Valencia Reference Martínez-Tagüeña, Rentería-Valencia, Lucatello, Huber-Sannwald, Espejel and Martínez-Tagüeña2019).

This community-based project grew from a respectful dialogue among the participants (Figure 3), which built mutual, or “horizontal,” relationships between all involved actors. This effort took several visits over three months to develop common goals and build initial trust. The establishment of a shared vision with mutual self-interests was key to then designing the project in a collaborative manner. The partnership was effective because the collaborative advantage was clear, and diverse knowledge systems with different narratives about the past were seen as a complement to overall knowledge rather than as the establishment of archaeology as “the” source of knowledge over others. Since the beginning, we defined what oral traditional knowledge was private or public, and we developed archaeological methodologies for archaeological survey registration without the need for artifact collection, in accordance with community members’ needs. Trust building took more than two years of collaboration, allowing better negotiation of responsibilities during knowledge coproduction (Figures 4 and 5). Also, the achievement of good communication across barriers of language, culture, and worldviews was crucial. The language of the Comcaac was always prioritized, and their cultural norms and value system were always respected throughout research activities. We are currently working on the challenging endeavor of sharing the project results with the community in a secure and digital way, and we have yet to develop and implement evaluation schemes to demonstrate our accountability.

FIGURE 3. Participatory tool for socio-environmental histories reconstruction during workshop. (Photograph by Natalia Martínez-Tagüeña.)

FIGURE 4. Intergenerational exchange workshop for traditional mussel processing. (Photograph by Natalia Martínez-Tagüeña.)

FIGURE 5. Survey registration of lithic remains. (Photograph by Natalia Martínez-Tagüeña.)

Engaging with Local Collectors

Guadalupe Sánchez and John Carpenter have a long-term relationship with diverse private collectors in the city of Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico. Their friends are primarily professionals from other disciplines, who include medical doctors and architects who are fascinated with ancient history and who would have studied archaeology if they had had the opportunity. However, it was only two years ago that the University of Sonora started offering a degree in anthropology. For these individuals, collecting artifacts is a hobby and a treasure hunt for history. They do not sell these artifacts, and they care for them as if there were part of their family heritage. In general, the collectors focus on projectile points obtained on the surface of their own and neighboring ranches. They are very knowledgeable about where to find projectile points on the landscape, understanding past mobility and subsistence behaviors. In addition, they have many acquaintances who own land, facilitating their contact information. Therefore, the collaborations with private collectors in Sonora have been very enriching for the study of Clovis and Archaic projectile points and sites.

From 2005 to 2007, collectors and archaeologists visited several Paleoindian sites together. Leopoldo Vélez, coauthor of this article, is a key player in establishing successful relationships between private collectors and archaeologists. In addition, due to his friendship with two ranch owners with archaeological evidence on their land, we were able to conduct archaeological research and photo-document private collections. These partnerships have been very beneficial because, together, we enhanced the knowledge about the past in shorter periods of time and with a broader understanding. Furthermore, these collections support students’ thesis work. One student from the Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia is anticipating conducting his research topic with Sonoran private collections.

To have a successful partnership between INAH and private collectors, it is crucial to promote collaborative leadership during planning. In addition, during the next implementation phase, collectors must be involved with the legal registration of cultural remains and other conservation activities. In our efforts, authorities, researchers, and collectors are equally involved. We are working on developing a strategy that begins with the invitation from INAH Sonora to private collectors to participate at a cultural heritage workshop as part of the diagnostic phase. Then several joint activities will be planned with the participant collectors, which include the registration of their archaeological evidence (objects and sites) in the Dirección de Registro Público system. Other activities such as archaeological site surveillance by community members, the preparation of brochures, and temporary exhibits in the Museo Regional de Sonora are good ways to connect with the community.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Undoubtedly, INAH Sonora is overwhelmed with work and facing insufficient monetary resources. The support of the local community is necessary to learn and protect archaeological heritage and achieve more knowledge about the past, which is relevant for the present. Only through multiple stakeholders’ partnership alliances will it be possible to sustain cultural heritage stewardship that emanates from caring, interweaving knowledge systems, and promoting resilient and adaptive individuals, groups, and institutions. Therefore, we consider it of utmost importance to implement an institutional program for collaboration between INAH Sonora and the local community members in compliance with the law but with horizontal dialogue and flexibility in perspectives, values, and interests. Our case studies have been effective not only in enhancing archaeological discipline and practice but also in establishing heritage stewardship as a means of promoting a sense of place, memory, identity, and social cohesion among community members. Although we are still testing our pilot proposals, we believe that we will be able to develop an operational approach for community archaeology and heritage stewardship that could be implemented in Mexico and used in other regions worldwide. The world is facing increasing socio-environmental problems, and culture—with an understanding and respect for its plurality—is essential for much-needed well-being, social cohesion, economic development, and good governance. People caring and collaborating for common goals will define the future for our Earth Stewardship.

Acknowledgments

We thank Centro INAH Sonora and project PN 2017-01-5035 (Convocatoria Problemas Nacionales-CONACYT) for funding, and the Comcaac community members who collaborated in this important endeavor and who are examples of true earth stewards.

Data Availability Statement

No original data are presented in this article.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.