The marketing of high in fat, salt and/or sugar (HFSS) food has been implicated in the development of poor dietary habits, overweight and obesity, which has serious consequences for health(1). In recent years, major food brands have expanded their focus from traditional media to digital media as an outlet for food marketing(2). This focus has included new and emerging digital platforms, such as video game live streaming platforms (VGLSP)(Reference Edwards, Pollack and Pritschet3,Reference Evans, Christiansen and Masterson4) .

An influencer is an individual with a large following in one or more niches (e.g. gaming). A VGLSP is a platform where streamers or ‘gaming influencers’ can broadcast live video game content to their audience online. The top VGLSP globally is Twitch, which has 78 % of the market share in terms of hours watched(Reference Hatchet5), and averages over 2·8 million concurrent viewers(6). A large majority of UK adolescents use video-sharing platforms (98 %), play video games online (76 %) and watch live streams (73 %)(7). Streamed games on Twitch also include those popular with young people, such as Fortnite and Minecraft(Reference Hatchet5,8) .

Streamers advertise brands and products, often simultaneously, in a variety of ways on VGLSP. Common in-stream advertising placements include jersey patches (i.e. brand logos on clothing), product placements (e.g. a streamer consuming a product) and banners (i.e. digitally overlaid images that can be static or have moving effects applied)(Reference Brooks9). In-stream banners are always visible and unobstructed by gameplay(Reference Brooks9). The most frequently marketed food categories (and brands) on Twitch are energy drinks, fast food restaurants, fizzy drinks and processed snacks(Reference Edwards, Pollack and Pritschet3,Reference Evans, Christiansen and Masterson4) .

Recent meta-analyses have demonstrated that exposure to unhealthy food marketing via television and digital media (social media, advergames) is associated with significant increases in children and adolescents’ marketed and overall ad-libitum HFSS food intake, relative to no or non-food marketing(Reference Boyland, McGale and Maden10–Reference Russell, Croker and Viner12). However, the impact of food marketing via VGLSP specifically is less clear. There is cross-sectional evidence that recall of food marketing on VGLSP is associated with greater consumption of marketed HFSS foods in both 13–18-year-olds and a predominantly young adult (18–24-year-old) sample(Reference Evans, Christiansen and Masterson13,Reference Pollack, Gilbert-Diamond and Emond14) . Further, a meta-analysis exploring digital marketing techniques of particular relevance to VGLSP (digital game-based and social media influencer marketing) found that exposure was associated with significant increases in children and adolescents’ marketed and overall HFSS snack consumption, relative to no or non-food marketing(Reference Evans, Christiansen and Finlay15). However, to date, there is no experimental research exploring the impact of food marketing via VGLSP on immediate snack consumption in young people. It is crucial that we understand how food marketing in various innovative digital spaces impacts food intake to inform evidence-based policies on unhealthy food marketing.

Adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of food marketing(Reference Harris, Yokum and Fleming-Milici16). Unique age-related developmental vulnerabilities include peer-group influence and identity formation processes(Reference Harris, Yokum and Fleming-Milici16). Neurobiologically, psychological mechanisms involved in the regulation of eating behaviour, such as neural substrates of inhibitory control, are not fully developed until late adolescence, and reward sensitivity is heightened at this age(Reference Harris, Yokum and Fleming-Milici16). This means that adolescents may lack the cognitive resources and motivation to inhibit appetitive responses. Marketing of HFSS foods to adolescents is specifically designed to take advantage of these unique developmental vulnerabilities(Reference Harris, Yokum and Fleming-Milici16). For example, adolescents are targeted by digital marketing that is disguised as entertainment (e.g. via social media influencers and digital games) which is more difficult to recognise as advertising and resist(Reference Harris, Yokum and Fleming-Milici16). Despite this susceptibility, much of the literature on youth food marketing focuses on children (only 18 % of existing studies focus exclusively on teenagers)(Reference Elliott, Truman and Stephenson17).

There is also a need to better understand the psychological mechanisms underpinning food marketing effects, particularly regarding contemporary digital food marketing and young people. The dual-process model of cognition is a useful theoretical framework for the examination of these psychological mechanisms(Reference Kakoschke, Kemps and Tiggemann18). The model is made up of two separate yet related cognitive processes: attentional bias and inhibitory control. Attentional bias is defined as the extent to which a cue (e.g. a food advert) grabs and holds attention. Inhibitory control refers to the ability to suppress reward-driven behaviour (e.g. consuming appetitive food). The addiction literature demonstrates that alcohol and tobacco advertising prime automatic consumption, and that young people are less able to inhibit this drive to consume(Reference Harris and Bargh19,Reference Harris, Bargh and Brownell20) . However, research exploring this effect in relation to food marketing is limited.

Existing evidence supports the notion that food marketing would impact an individual’s cognitive processes. A meta-analysis found considerable evidence that attentional bias towards food-related stimuli is associated with food craving and intake(Reference Hardman, Jones and Burton21). Moreover, children with a higher gaze duration (i.e. greater attention bias) for food cues in an advergame ate more advertised snacks(Reference Folkvord, Anschutz and Wiers22). In relation to Twitch users (aged 18–24), higher scores on external food cue reactivity measures were related to increased odds of craving products seen on Twitch(Reference Pollack, Emond and Masterson23). Overall, this suggests that heightened sensitivity to food-related cues (e.g. food marketing) could play a causal role in overeating.

Regarding inhibitory control, impairments in the ability to suppress reward-driven behaviour are associated with the choice and intake of HFSS foods and obesity(Reference Meng, Huang and Ao24,Reference McGreen, Kemps and Tiggemann25) . Additionally, children who participated in a go-no-go food task in which the advertised food was consistently associated with no-go cues (strengthening inhibitory control) were found to consume significantly fewer calories after playing an advergame promoting energy-dense foods, compared with those who did not participate in the task(Reference Folkvord, Veling and Hoeken26). Therefore, it would be logical to assert that inhibitory control interacts with cues from obesogenic environments (e.g. food marketing).

Together, this evidence suggests that increased attentional bias towards food-related cues and poor inhibitory control are likely to be associated with increased cue-induced food consumption, as predicted by the dual process model of cognition. The collective effect of attentional bias and inhibitory control on food marketing-induced eating is yet to be tested. Moreover, existing studies assessing their individual impacts have been restricted to food marketing via advergames. Given that recent neuroimaging evidence shows that different advertising mediums have unique effects on neural responses to food cues in children(Reference Yeum, Jimenez and Emond27), medium-specific food marketing research is warranted.

The current study used a between-subjects randomised controlled trial to primarily explore the effects of HFSS food marketing exposure via a mock Twitch stream on immediate snack consumption in a sample of UK adolescents. The potential moderating role of attentional bias and inhibitory control was also assessed using computer-based behavioural tasks. The impact of several potential covariates (e.g. gender, habitual use of VGLSP) on snack consumption was assessed using questionnaire measures.

Our primary hypothesis was that participants in the experimental condition would have greater marketed snack intake (kcal) and greater overall snack intake (kcal) than those in the control condition. We also tested exploratory hypotheses: (i) participants with longer gaze duration towards the food advert would have a greater marketed snack intake and overall snack intake, (ii) those with poorer inhibitory control scores would have a greater marketed snack intake and greater overall snack intake in response to the food advert and (iii) the interaction between attentional bias and inhibitory control would predict marketed and overall snack intake (specifically, that individuals with greater attentional bias and poorer inhibitory control would consume the most food in response to the food advert).

Methods

The study protocol was pre-registered, including design and analytic plans. The protocol, experiment materials and data can be accessed at https://osf.io/u6my3/.

Participants

Sample size was calculated using G * Power. Based on a medium-large effect size of d = 0·6 (related studies exploring the impact of exposure to HFSS food marketing via social media influencers(Reference Coates, Hardman and Halford28) and advergames(Reference Folkvord, Anschutz and Wiers22) identified a medium-large sized effect on subsequent HFSS food intake) at 80 % power, the total required sample size for a between-subjects linear model with two groups and two covariates = 90. While no previous studies have examined the impact of experimental exposure to food marketing via videogame live streaming and potential moderators, it is likely that exploratory two- and three-way interaction effects (e.g. condition*gaze duration*inhibitory control on intake will be smaller, and therefore, the study may be underpowered to detect them)(Reference Sommet, Weissman and Cheutin29). Participants were identified through direct contact with youth-focused organisations, word-of-mouth and social media. The inclusion criteria for participants were 13–18 years of age, no medical condition(s) which would have meant they could not abstain from eating for 2 h (e.g. diabetes), no food allergies or intolerances, not dieting to lose or maintain weight and no current or historical eating disorders. Data were collected January–August 2023 until the required sample size was reached.

Design

The study was a between-subjects randomised controlled trial. Participants were allocated a participant number and, using a block randomisation schedule (in blocks of 10; www.randomizer.org), were assigned to either the control (non-food marketing) or experimental (food marketing) condition. Therefore, the independent variable was the marketing condition. Dependent variables were marketed (Doritos) and overall snack consumption (kcal). Covariates included scores on attentional bias and inhibitory control measures.

Materials

Mock Twitch streams

One Twitch streamer, 31-year-old male Tyler ‘Ninja’ Blevins (https://www.twitch.tv/ninja), was selected based on his popularity with young people(8). Therefore, this content was deemed likely to be typical of what adolescents may encounter when using Twitch or other similar VGLSP.

One video (high definition, 1280 × 720 pixels) of Ninja playing Fortnite from 27 July 2022 was obtained from Ninja’s Twitch channel using the screen-recording and video editing software Camtasia (TechSmith, MI, US). The video was cropped so that it was 7 min in duration (5 min of exposure is sufficient to prompt an intake effect in children(Reference Russell, Croker and Viner12)). Editing was also used to overlay a static banner advert designed for the study on each video for the full duration. Both versions of the video were identical but for the brand and product featured in the banner advert. In the control videos, the banner advert featured a non-food item (Adidas trainers), and in the test videos, it was an HFSS snack (Doritos Lightly Salted crisps). Processed snacks are the most frequently marketed non-perishable food category on Twitch with Doritos representing the top brand in this category(Reference Edwards, Pollack and Pritschet3). Doritos is also the second leading snack brand in the UK and was therefore likely to be a familiar brand for our sample(Reference Conway30). Similarly, Adidas is well-known by the UK public(Reference Cameron31). Lightly salted crisps were selected as they are suitable for vegetarians and vegans. No other marketing is featured in the videos. Each banner advert featured the caption ‘Ninja x [brand]’, which is often used to designate an influencer × brand collaboration. Visually, this advert is similar to in-stream banners used on Twitch (e.g. size, location)(Reference Brooks9Reference Evans, Christiansen and Finlay15). See the Appendix for the video and advertising stimuli used.

Cover story

Eating is a psychological process that can be modified by individuals if they are aware of the aims of the study(Reference Robinson, Kersbergen and Brunstrom32). Therefore, participants were informed that the study aimed to explore participant memory in relation to video game live streams and determine which streamers are the most engaging to watch. Some dummy questions were included in the questionnaire (e.g. ‘What colour hoodie was Ninja wearing?’) to make the cover story seem more authentic. The true aims of the research were not made explicit to the participants until after they completed the study.

Questionnaire

To adjust for potential effects on kcal food intake, a pre- and post-exposure questionnaire was created. Questionnaire measures were developed and delivered using the web-based survey tool Qualtrics XM.

Pre-exposure

Demographics

Participants were asked their age, gender, ethnicity and residential postcode as a proxy for socio-economic advantage. Postcode was used to calculate their index of multiple deprivation decile (https://www.fscbiodiversity.uk/imd/). A decile of 1 means the postcode is in the bottom 10 % of the deprivation index.

Time spent on video game live streaming platforms per week

Participants were first asked ‘Have you ever used a VGLSP? For example: Twitch, YouTube Gaming, Facebook Gaming’. If [yes], participants were asked how many hours they spend on VGLSP (a) on a typical weekday (e.g. a Monday) and (b) on a typical weekend day (e.g. a Saturday). Total weekly hours were calculated as (typical weekday hours × 5) + (typical weekend day hours × 2).

Test brand liking

Liking of the test food was measured using 100-mm visual analogue rating scales anchored with 0 = really dislike and 100 = really like. Questions followed the format of ‘how much do you like [brand]?’. The test brands (Doritos, Tesco, Adidas) were included alongside other brands that did not feature elsewhere in the study (Nike, Cadbury’s) to disguise study aims. The other brands were selected based on being well-known by the UK public.

Hunger

Participants were asked ‘How hungry do you feel right now?’ which was responded to on a visual analogue rating scale anchored with 0 = not at all hungry and 100 = extremely hungry.

Prior streamer and video game familiarity

Participants were asked ‘How familiar are you with… (i) the Twitch streamer ‘Ninja’? and (ii) the videogame Fortnite?’ which was responded to on a separate visual analogue rating scale anchored with 0 = very unfamiliar and 100 = very familiar.

Post-exposure

Liking of the stream

Participants were asked ‘How much do you like the Twitch stream that you just watched?’ which was responded to on a visual analogue rating scale anchored with 0 = really dislike and 100 = really like.

Awareness of marketing

Participants were asked ‘Did the Twitch stream you watched today have an advert in it?’ with a yes/no response. If [yes], participants were prompted to indicate the brand/product that was advertised. This question was embedded amongst several ‘dummy’ questions, consistent with the cover story. Marketing awareness was operationalised as whether the brand and/or product was correctly identified (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Awareness of study aims

Participants were asked ‘What do you think the aim of the study was?’ with a free-text response. A response was deemed correct if it referenced the impact of food marketing on snack consumption (or something to that effect). Awareness of study aims was operationalised as whether the true aim was correctly identified (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Behavioural tasks

Computer-based behavioural tasks were conducted on a desktop computer using Gazepoint v.5.1.0 and Inquisit v.5.0.14.0.

Attentional bias

A portable research-grade eye tracker (GP3 Eye Tracker, Gazepoint) was used to test attentional bias towards the banner advert in the test video. Data were obtained using a machine-vision camera with a 60 Hz sampling rate and 0·5–1 degree of visual angle accuracy. The two versions of the test video were uploaded to Gazepoint, and an area of interest was drawn around the banner advert. The test video was presented on a screen with a 1920 × 1080 resolution (16:9 ratio). Participants were seated 55 cm from the display screen and an adjustable chinrest was used to reduce head movement. A nine-point calibration system was used to calibrate the eye tracker prior to testing, in which an expanding–contracting circle appeared in every position on a screen-wide 3 × 3 grid of calibration points. Participants were asked to fixate on the circle. The calibration was repeated if any points did not calibrate successfully. Attentional bias was measured as the duration of fixations on the area of interest (i.e. gaze duration).

Inhibitory control

A cue-specific version of a stop-signal task originally developed by Logan et al.(Reference Logan, Cowan and Davis33) was used to measure inhibitory control. The task was programmed using Inquisit (https://mili2nd.co/l5ac). Participants were required to press the ‘D’ key in response to food images, and the ‘K’ key in response to neutral images. However, in some trials, a red ‘X’ (i.e. a stop signal) appeared over the image shortly after it appeared, which indicated that the response should be withheld. Sixteen images of branded foods and sixteen images of neutral objects (musical instruments) (see Appendix for images used) were included. Images of branded foods were selected based on the most frequently advertised food brands on Twitch(Reference Edwards, Pollack and Pritschet3). This was because we were interested in inhibitory control in relation to HFSS foods that are commonly marketed on Twitch (i.e. ‘gamer’ foods) specifically. The test brand (Doritos) was not included, to minimise specific priming effects on eating(Reference Chao, Fogelman and Hart34,Reference Kay, Kemps and Prichard35) . Images of musical instruments were matched to branded food images in terms of size and colour. The task had 400 trials (200 food images, 200 neutral images), and a stop signal was presented in 25 % of the trials, consistent with recommendations to ensure reliability(Reference Kay, Kemps and Prichard35). Stop signal reaction time (SSRT) was calculated using the integration method, and the difference in task performance (SSRT) between food and neutral pictures was calculated as SSRT food cues – SSRT neutral cues, with positive values indicating worse inhibitory control towards food cues. Participant scores were excluded if specific parameters were violated(Reference Verbruggen, Aron and Band36).

Energy intake

Consistent with previous studies(Reference Coates, Hardman and Halford28), to measure energy intake, participants were told they could have a 5-minute ‘snack break’ and invited to eat ad libitum from two bowls of tortilla crisps). Each bowl contained 100 g of Doritos Lightly Salted tortilla crisps, but one was labelled ‘Doritos’ and the other was falsely labelled ‘Tesco’s’ (the largest supermarket chain in the UK). Participants were verbally informed of the purported brand difference. This approach, used in a similar study(Reference Coates, Hardman and Halford28), enabled brand-specific intake effects to be disentangled from any general consumption effects of the marketing. The quantity of crisps (100 g in each bowl) was used to avoid ceiling effects (i.e. participants consuming all the available crisps) and has been used for HFSS food provided to children in previous food intake studies(Reference Coates, Hardman and Halford28). Crisps were presented in plastic serving bowls and discreetly weighed pre- and post-intake (out of sight of the participant) to the nearest 0·1 g using a calibrated food weighing scale (Model CPA4202S; Sartorius AG, Germany). Intake was measured by calculating changes in snack vessel weight. Data were then converted into kilocalories (kcal) based on the manufacturer’s nutritional information.

BMI

Participant weight was measured to the nearest 0·1 kg with a calibrated weighing scale (Seca, model: 888, Germany), and height was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm using a stadiometer (Leicester Height Measure). BMI was calculated as kg/m2 and converted to a standardised Z score using WHO reference data(37). BMI z-score outliers (< –4 sd or > 8 sd) were excluded based on the definition from Freedman et al.(Reference Freedman, Lawman and Skinner38).

Procedure

The study took place in a Psychology laboratory at the University of Liverpool. All participants attended one 45-minute session between 09.00 and 17.00. Informed consent was gathered prior to the session via Qualtrics. Firstly, participants completed a medical history questionnaire to confirm that they did not have any food allergies or intolerances. Then, the pre-exposure questionnaire was administered. Secondly, inhibitory control was assessed using the stop-signal task. The researcher read the instructions to the participants and gave them the opportunity to ask questions if they were unsure. After the task was complete, participants were asked to use the chin rest, and the height was adjusted accordingly. The eye-tracker was then set up, and participants were told that they would be watching a short excerpt from a Twitch stream, and that they should try to pay attention as they would be asked questions about it later. The researcher then played the appropriate version of the Twitch stream.

Post-exposure, participants were told that they could have a snack break. They were presented with the bowls of crisps and informed that they could eat as much or as little as they wanted. The researcher played a neutral Twitch stream (no marketing exposure) on the desktop computer and informed participants that they would not be asked questions in relation to this stream. The researcher then left the room for 5 min. After this period, the researcher returned and collected the bowls of crisps, which were reweighed in a separate kitchen area.

Participants then completed the post-exposure questionnaire. Following this, participant height and weight (without shoes) were measured and recorded. After the session was complete, participants were debriefed and informed of the true aims of the study. Participants (and any attending parent) were given a £5 Amazon voucher as compensation for their time. Participants were also given the option to enter a prize draw to win a £100 Amazon voucher. The winner was selected using a random number generator and their voucher was emailed to them.

Data analysis plans

All analyses were conducted using R. Statistical tests’ level of significance was set at P < 0·05 for main analyses and P < 0·01 for sensitivity analyses.

We used two linear models to assess the impact of the condition (food marketing v. non-food marketing) on Doritos intake (model 1) and overall intake (model 2). We also assessed the impact of condition*gaze duration, condition*SSRT and condition*gaze duration*SSRT interactions in both models. To assess the assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity and identify influential cases, Residuals v Fitted, Q–Q Residuals, Scale-Location and Residuals v. Leverage (Cook’s distance) plots were consulted. To assess the normality of residuals, residual histograms and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests (P > 0·05) were inspected. Finally, multicollinearity between predictors was examined using VIF (Variance Inflation Factor; VIF > 5 is slightly problematic, VIF > 10 is very problematic(Reference James39)). For both models, sensitivity analyses were performed by replicating the main analyses (i) after excluding participants aged 19 years and over and (ii) after excluding aim guessers.

Results

Final sample

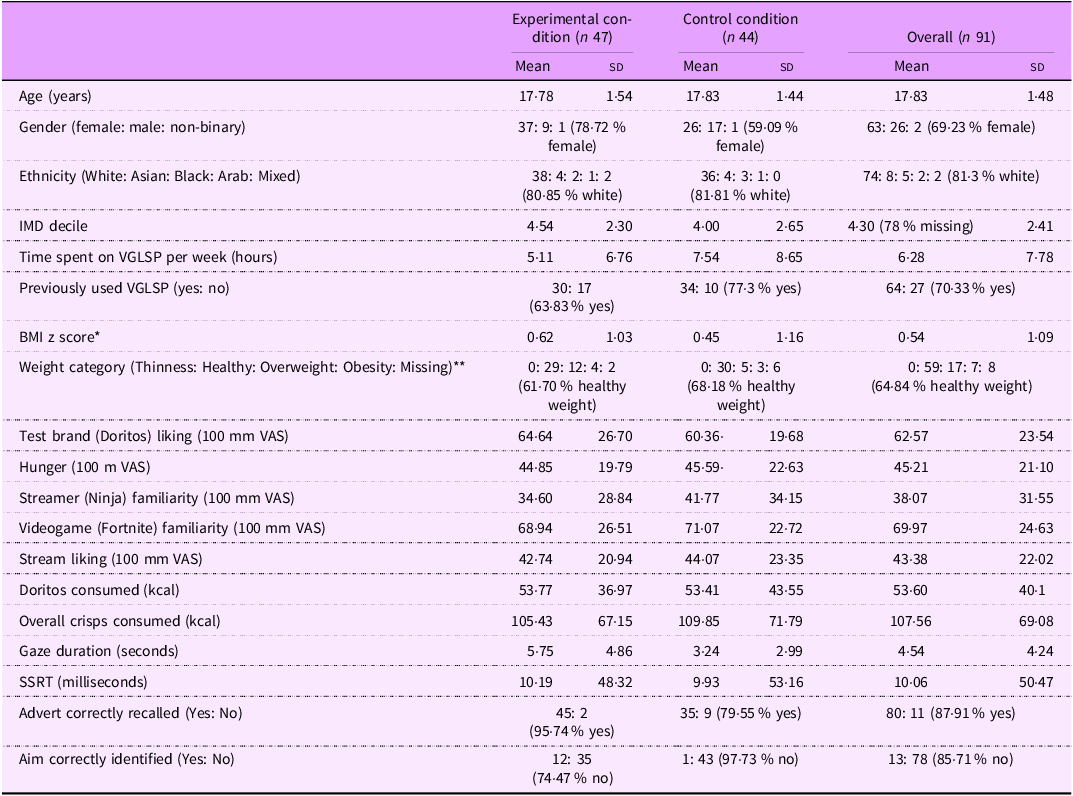

Ninety-five participants took part in the study (see Table 1 for sample characteristics). Eighteen participants indicated that they were 13–18 years old when answering the age screening question (pre-session) but reported a higher age when asked for their specific age in years and months during the lab session. Four participants were excluded due to not being adolescents (i.e. ≥ 20 years). Although one of our specified inclusion criteria was to be 13–18 years, we decided to retain the fourteen 19-year-old participants, due to them still being classed as adolescents and to maintain statistical power. This resulted in a final sample size of ninety-one participants. Eight participants elected to not be weighed and/or measured; therefore, BMI z-score and weight category data are missing for these participants. Six participants violated parameters on the Stop Signal task(Reference Verbruggen, Aron and Band36), and therefore, their data were entered as missing for the SSRT variable. The sample was largely representative of the UK youth population in terms of ethnicity and weight status but not gender(40–Reference Stiebahl42).

Table 1. Sample characteristics, split by condition

IMD, index of multiple deprivation; VGLSP, video game live streaming platform; VAS, visual analogue rating scale; SSRT, stop signal reaction time.

*A standardised BMI z score based on age was calculated using WHO reference data(37). **Weight category cut-offs were defined as thinness: < –2 sd, healthy weight: > –2 sd < +1 sd, overweight: > +1 sd, obesity: > +2 sd(37).

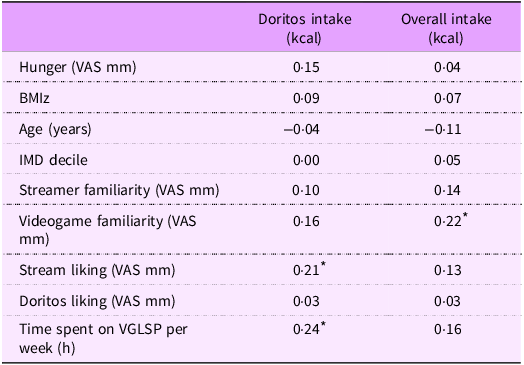

To examine which variables should be included as covariates in the main analyses, Pearson’s correlations were calculated. As shown in Table 2, stream liking and weekly time spent on VGLSP were positively correlated with Doritos intake. Familiarity with the video game Fortnite was positively correlated with overall intake. Welch’s two sample t tests were calculated for categorical variables (gender [m/f ], advert recall [y/n] and aim guess [y/n]). There was a significant difference in overall intake based on gender, with males consuming significantly more than females (P < 0·05). There were no other significant differences in Doritos or overall intake (all P > 0·05).

Table 2. Pearson’s correlations between dependent variables and covariates

IMD, index of multiple deprivation; VGLSP, video game live streaming platform; VAS, visual analogue rating scale.

* P < 0·05.

Model 1: Predictors of Doritos intake

Examination of the relevant plots revealed one problematic (influential) case. This case was removed, resulting in the assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity being met. Assumptions of normality were also met. Multicollinearity (some VIF > 5) was resolved by mean-centering the gaze duration and SSRT variables (all VIF < 3). The first linear model included Doritos intake as the dependent variable. VGLSP weekly use and stream liking were included as covariates due to their significant correlation with Doritos intake. The inclusion of two additional covariates did not impact the required sample size (n 90, G * Power).

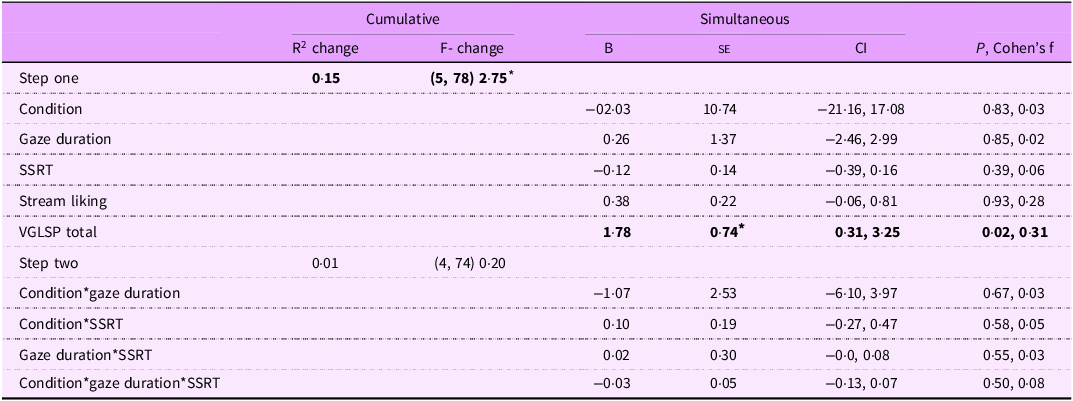

The overall model was non-significant (R2 = 0·16, F(9, 74) = 1·55, P = 0·15). As shown in Table 3, step one of the hierarchical model significantly predicted approximately 15 % of variance in Doritos intake. The only significant predictor was weekly VGLSP use, with greater time spent using VGLSP per week being associated with increased Doritos intake. The size of this effect was medium-large(Reference Cohen43).

Table 3. Model 1, predictors of Doritos intake

VGLSP, video game live streaming platform; SSRT, stop signal reaction time.

* P < 0·05 (also highlighted in bold).

Model 2: predictors of overall snack intake

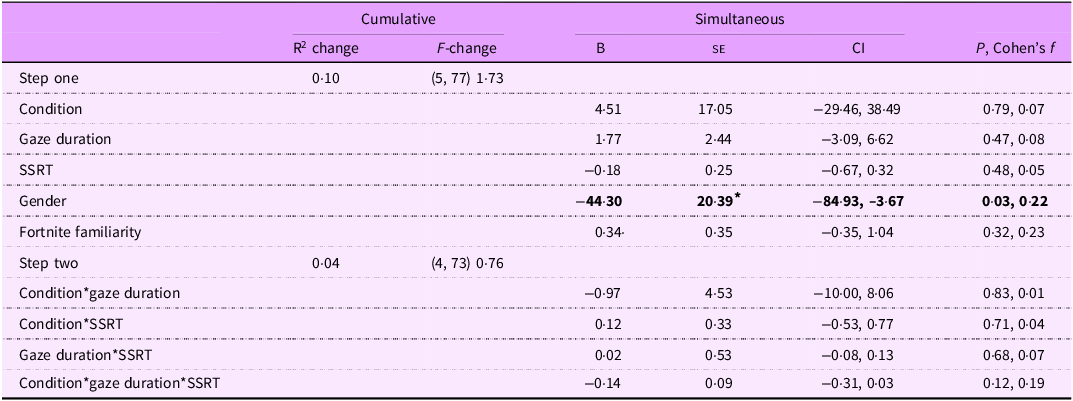

Examination of the relevant plots and tests revealed that assumptions of normality, linearity and homoscedasticity were met. Again, multicollinearity (some VIF > 5) was resolved by mean-centring the gaze duration and SSRT variables (all VIF < 3). The second linear model included overall snack intake as the dependent variable. Fortnite familiarity was included as a covariate due to its significant correlation with overall snack intake, and gender was included as males had significantly greater overall snack intake than females.

The overall model was non-significant (R2 = 0·14, F(9, 73) = 1·29, P = 0·26. As shown in Table 4, both steps in the model were also non-significant. The only significant predictor was gender, with being male associated with greater overall intake. The size of this effect was medium-large(Reference Cohen43).

Table 4. Model 2, predictors of overall snack intake

SSRT, stop signal reaction time.

* P < 0·05 (also highlighted in bold).

Sensitivity analyses

Neither the removal of participants aged 19 years and older nor the removal of aim guessers notably impacted any models or individual predictors. See Appendix for full sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

This between-subjects randomised controlled trial assessed the effect of HFSS food marketing exposure (compared to non-food marketing exposure) in a mock Twitch stream on immediate marketed and overall snack intake. It was firstly hypothesised that participants in the food marketing condition would have greater marketed and overall snack intake than those in the non-food marketing condition. No significant association between the condition and either marketed or overall snack intake was found, and therefore, this hypothesis is rejected. However, although the overall model was non-significant, it was found that greater weekly use of VGLSP was associated with increased marketed snack intake. It was secondly hypothesised that participants who showed greater attentional bias towards the food advert would have greater marketed and overall snack intake, and those with poorer inhibitory control would also have greater marketed and overall snack intake in response to the food advert. No significant interaction between the condition and either gaze duration or inhibitory control in terms of predicting marketed or overall snack intake was found. Therefore, both hypotheses are unsupported. Finally, it was hypothesised that participants with the highest rates of attentional bias and the poorest inhibitory control would have greater marketed and overall snack intake in response to food marketing. No significant interaction effect of gaze duration and inhibitory control in response to food marketing was found, and therefore, this hypothesis is also unsupported.

The finding that acute exposure to Twitch/VGLSP-based food marketing was not significantly associated with immediate snack intake is largely inconsistent with existing research. Several reviews have identified an association between food marketing exposure via both traditional media (e.g. TV) and digital media (advergames, social media [including influencers]) and greater HFSS food intake(Reference Boyland, McGale and Maden10,Reference Packer, Russell and Siovolgyi11,Reference Evans, Christiansen and Finlay15) . One meta-analysis found that experimental exposure to key marketing techniques used on VGLSP (influencer or digital game-based marketing) led to the consumption of an additional 37 kcal in HFSS food(Reference Evans, Christiansen and Finlay15). In comparison, a negligible difference in HFSS snack consumption between the experimental and control conditions (< 5 kcal) was found in this study. While we sought to examine the impact of an in-stream static banner advert specifically, it is important to note that food marketing on Twitch is often synergistic and includes a range of different in-stream advert types, such as jersey patches, product placements, banners and video adverts(Reference Brooks9). Therefore, the behavioural impact of exposure to food marketing on Twitch may be underestimated in this study.

In addition to this, while experimentally impractical to simulate, a core Twitch viewer spends nearly 5 h every day on the platform(Reference Hatchet44). This greater duration of, and more sustained, exposure is likely to have more of an impact on eating behaviours (i.e. a dose-response relationship(Reference Norman, Kelly and Boyland45)). Indeed, in the current study, it was found that, although the overall model was non-significant, higher weekly use of VGLSP was associated with greater marketed snack intake. This complements findings that higher recall of food marketing on VGLSP is associated with greater HFSS food consumption in both adolescents and adults(Reference Evans, Christiansen and Masterson13,Reference Pollack, Gilbert-Diamond and Emond14) . The test brand used in the current study (Doritos) has strong ties with streaming and gaming, and therefore, it is likely that a more frequent Twitch (or VGLSP in general) user would have greater habitual exposure to Doritos marketing. Doritos is the most frequently marketed and mentioned (i.e. in the chatroom) snack food brand on Twitch, and the brand has its own ‘chip’ emote which can be used in the chatroom(Reference Edwards, Pollack and Pritschet3,Reference Brooks9) . However, further experimental research is needed to isolate this effect and determine whether it can be replicated.

The finding that attentional bias towards the food advert was not associated with intake is also inconsistent with existing research. Previous studies found that children with a higher gaze duration for food cues in an advergame ate more of the marketed HFSS snacks(Reference Folkvord, Anschutz and Wiers22). It is possible that differences were driven by variation in (i) the prominence of the advert (i.e. size, positioning) and/or (ii) the involvement of the media (i.e. a pairs advergame v. a Fortnite stream). Indeed, more prominent adverts tend to be remembered better, and prominence and involvement are known to interact in in-game advertising (IGA; i.e. at moderate involvement prominent brands are recognised better than peripheral brands)(Reference Terlutter and Capella46). It may be that more prominent and dynamic adverts (e.g. looping banner adverts, interactive product placement) are required to capture attention when watching an involved Twitch stream.

Similarly, the finding that inhibitory control was not associated with intake is largely in disagreement with previous research. In one study, children whose inhibitory control was strengthened (in relation to the advertised food, using a go-no-go food task) were found to consume significantly fewer calories after playing an advergame promoting energy-dense foods, relative to those who did not complete the task(Reference Folkvord, Veling and Hoeken26). In contrast, in this study, having poorer inhibitory control for commonly advertised branded foods on Twitch was not significantly associated with greater branded or overall snack consumption in response to the food advert. It may be that because our sample was predominantly made up of older adolescents, psychological mechanisms behind inhibitory control were more developed, leading to a diminished effect(Reference Harris, Yokum and Fleming-Milici16). Indeed, a meta-analysis of the effects of exposure to food-related cues on inhibitory control in adults found no effect, suggesting that age is important(Reference Jones, Robinson and Duckworth47).

Overall, our findings are not consistent with the dual process model of cognition, which predicts that both increased attentional bias towards food-related cues and poor food-related inhibitory control are likely to be associated with increased cue-induced food consumption. It is possible that our sample, in general, did not have an attentional bias toward food cues and/or poor food-related inhibitory control. It may also be that this model is not applicable to food marketing effects in the context of videogame livestreaming. VGLSP use a unique range of marketing integration strategies (e.g. saturation, congruency, social influence) which may interact differently with measures of attentional bias and inhibitory control(Reference Maksi, Keller and Dardis48). However, further research examining responses to various advert formats in VGLSP is required to test this assertion.

The current study has some limitations. Lightly Salted Doritos were served to participants without an accompanying dip. This may not be representative of the typical eating experience and therefore could have resulted in lower intake. Owing to difficulties recruiting the target age group, opportunity sampling was used, which meant that the sample was predominantly female, which is likely not representative of the typical Twitch user (approximately 70 % are male(49)), and there were more females in the experimental condition. Similarly, the mean time spent on VGLSP per week was approximately 2 hours less in the experimental condition, relative to the control condition. It was found that being male and spending more time on VGLSP were significantly associated with greater overall snack and Doritos intake, respectively, so this may have biased results towards the null. Future studies may wish to use quota sampling to ensure balanced assignment to conditions based on gender and VGLSP use.

It is recommended that future studies assess the effect of other commonly used advertising placements on Twitch and other VGLSP both in isolation and together (i.e. their combined effect on eating behaviour). In addition, it would be beneficial to replicate the study in different samples, such as younger adolescents, males and those who use VGLSP regularly (i.e. weekly), as these subgroups are likely to be most impacted by advertising on VGLSP. Future research should also endeavour to investigate the impact of exposure to food marketing via VGLSP on food intake over time (e.g. using screen recording software to monitor exposure) and on other food-related outcomes such as norms, attitudes and intended purchase.

Conclusion

Overall, findings suggest that exposure to a static food banner advert in a mock Twitch stream was not significantly associated with immediate marketed or overall snack intake in adolescents. Moreover, attentional bias and inhibitory control did not appear to have any significant impact on consumption in response to food marketing. However, although the overall model was non-significant, we did find that higher weekly use of VGLSP was associated with greater marketed snack intake. The findings are largely inconsistent with existing research exploring the impacts of food marketing exposure via digital media on food intake. Future research is recommended to explore the impacts of different advertising placements on VGLSP (and their combined effect), replication in specific samples and assessment of the impact of longer-term exposure to this marketing.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980025100487

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Lee Cunningham and Zoe Mapp who assisted with the running of study sessions.

Authorship

R.E., E.B., P.C. and A.J. participated in developing the research questions and designing the study. R.E. and J.F. were responsible for data collection. R.E., P.C. and A.J. were responsible for data analysis. R.E. wrote the original draft and all authors were involved in reviewing and editing the paper.

Financial support

The study was conducted as part of R.E.‘s PhD work, which was funded by the University of Liverpool. No external funding was provided.

Competing interests

P.C. reports grants from the American Beverage Association, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics of humans subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Liverpool Central Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 6228).