1.1 Introduction

Language learning is usually associated with the early years of life when it gradually evolves from babbling to uttering, while parents and carers struggle to figure out the real communicative intentions of isolated and often poorly articulated stretches of sound. Known as the holophrastic stage, a word in a toddler’s speech may have multiple meanings, only revealed by insistent repetitions and requests for clarification, which usually manage to reveal the real purpose of the utterance. Thanks to the descriptions that have been made of its components, language development in infancy, from the gradual growth of vocabulary to the onset and refining of syntax, has been thoroughly researched (Ambridge and Lieven Reference Ambridge and Lieven2011; Elliot Reference Elliot1981). Be that as it may, linguistics has expanded the period of language development to include successive stages encompassing early childhood, middle childhood, early adolescence, mid-adolescence, and adulthood. In fact, this development occurs in all life stages and only declines in old age (Christie Reference Christie2012; Durrant et al. Reference Durrant, Brenchley and McCallum2021; O’Dowd Reference O’Dowd2012).

The language growth continuum starts with the variety that speakers use in their close circle, which then gives way to a ‘space–time synchronicity’. It is only in the second stage that language evolves with the newly acquired ability to refer to events transpiring earlier or later in time and further away from the speaker, namely, a ‘space–time asynchrony’. This is also known as ‘here and now’, as opposed to ‘there and then’, language.

An imperative sentence such as ‘stand closer to this ball’ displays all the features of ‘here and now’ language:

‘Here and now’ language is an interactional variety used mostly in conversations and usually involves other speakers.

It depends on the context and only makes full sense in that in which the utterance is made, implying a previous knowledge of the speaker, the object itself, and its surroundings. Simply put, information does not make sense without a context.

It relies on information sources other than language, including the visual kind in which the position of the speaker and the listener determines the actual meaning.

In parallel to the former distinction, there is the gradual transition from ‘learning to use language’ – controlling the mechanisms of the system – to ‘using language to learn’ – employing communication tools to acquire new knowledge. The latter relates to the raison d’être of academic language, namely, knowledge production and transfer in the school setting.

Academic language owes its existence to the fact that complex social activities, like teaching students, demonstrating learning, conveying ideas, and constructing knowledge, rely on language features that characterize a particular style (Hyland Reference Hyland, Hyland and Paltridge2011:174). Academic language traits have tended to be associated with a higher level of abstraction, complexity, lexical density, and grammatical intricacy (e.g. Achugar and Carpenter Reference Achugar and Carpenter2014; Schleppegrell Reference Schleppegrell2004). The existence of a set of core language mechanisms is similar across all fields, and these mechanisms occur at all sentence and discourse levels.

Prior to an adequate characterization of academic language, which will be provided in the following chapters, the following preliminaries need to be considered:

The components of academic language. Academic language affects all language levels: lexis, syntax, and discourse, while employing more uncommon words, more complex structures, and more specialized genres. Words like ‘integer’ in maths or ‘colony’ in history, structures like third conditional types in irrealis discourse, and genres like philosophical dialogue are essentially academic and thus more likely to appear in scholarly or institutional contexts (for syntax in academic language, see Bhatia Reference Bhatia and Johns2002; for vocabulary, Nation Reference Nation2006; for genres, Peters Reference Peters2008).

The acquisition of academic language. The acquisition of academic language structures is governed by the rules emerging from the analysis that learners perform on the distributional characteristics of the language input. These rules are either structurally or cognitively complex, and consequently, their acquisition is demanding and time-consuming. Advanced language structures are firmly linked to those types of academic content that are more susceptible to certain constructs. Multidimensional studies have consistently described register variation in different text types based on the occurrence of diverse structures (Biber et al. Reference Biber, Davies, Jones and Tracy-Ventura2006).

The cognitive nature of academic language. Academic language is more cognitively taxing than the instinctive language of casual conversation. Consequently, it evolves as speakers find themselves in new communicative situations requiring greater precision and denotation or when events need to be described in greater detail. The production of narratives starts as personal storytelling early in life, before evolving into an account of events that the subject has not physically experienced, namely, the ability to represent the world cognitively and symbolically (Tomasello Reference Tomasello2005). Narrative structure changes apace with cognitive development.

The disciplines of academic language. Academic language relates to disciplines, with each academic field, from maths to history, and at a more specialized level, from numismatics to zoology, shaping it in its own way. Even if there existed a grammar of a language applicable to all disciplines, not to mention a universal grammar, the core structure of all human language, it would still be possible to talk about the grammar of maths or history. The fact remains that there are certain functions that are inherent to some disciplines. For example, numbers are added, subtracted, and multiplied in maths. These are disciplinary functions that have to do with language (for maths, see Barwell et al. Reference Barwell, Clarkson, Halai, Kazima, Moschkovich, Planas, Phakeng, Valero and Villavicencio Ubillús2016; Prediger et al. Reference Prediger, Wilhelm, Büchter, Gürsoy and Benholz2018; for history, Lorenzo Reference Lorenzo2017; Van Drie et al. Reference Van Drie, Braaksma and Van Boxtel2015; and for science, Lemke Reference Lemke1993).

The designation of academic language. Different concepts are employed to refer to academic language: languages of schooling, languages of the disciplines, and the cognitive academic language learning approach (Uccelli Reference Uccelli2023). Other designations include a social element, distinguishing between vertical and horizontal discourse to represent the layered structure of society since both language and social structures show consistent patterns of variation between a person’s social position and the forms, uses, and styles of language they employ (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2000). This vision frames the acquisition of academic language in the educational tradition of progressive democratic and inclusive education (Snow and Uccelli Reference Snow, Uccelli, Olson and Torrance2009).

1.2 A Social Description of Academic Language

Language acquisition is described as a socio-cognitive process, a mental construct that corresponds to communication needs determined by external factors, namely, their contextual determinants. The context – technical, institutional, or professional – determines the way in which academic language is constructed (Housen and Kuiken Reference Housen and Kuiken2009). A contextual approach to academic language, therefore, needs to consider the following elements to research language in society, which conform to the classical acronym ‘SPEAKING’ (Hymes Reference Hymes, Pride and Holmes1972; see also Flowerdew Reference Flowerdew2014; Hyland Reference Hyland, Hyland and Paltridge2011):

Situation. The spatio-temporal constraints of academic social interaction place particular demands on language, regardless of whether it is being used in atriums, where pre-Socratic philosophers compared views on the nature of things, or in aristocratic salons where mademoiselles received intellectuals in pre-revolutionary France during the Enlightenment (Cooper Reference Cooper1990). The usual setting for formal education is now the classroom, lecture hall, seminar room, or alternative real or virtual venues where it is possible to engage in intellectual intercourse in an orderly fashion. In other words, academic discussions are subject to a conventional time frame that is rather inflexible as to its duration.

Participants. Scholars form part of very exclusive networks at a time when clannishness is rife, for, as with many other collectives, they are fully aware of their prestige. They have an acute sense of belonging that makes their language interaction extremely conventional, predictable, and alien to outsiders. Accordingly, scholars may be standoffish, for which reason the social distance between speakers is usually maintained and tends to revolve around the recognition of experts who are held in high esteem for their pursuit, if not their possession, of the truth.

Ends. The main purposes of academic interaction are research and teaching, that is, new knowledge production and transfer. As a matter of fact, knowledge is such a core element of modern life that the term ‘knowledge society’ has been coined to describe it. The purpose of academic communication is more often than not instrumental, employed for describing a product (e.g. a vaccine) or a process (e.g. pasteurization). Knowledge production requires the existence of truth conditions according to which an event is enacted. The purpose is sometimes speculative, with the credibility of the arguments deployed relying on the logical elaboration of discourse. Whatever the purpose, academic discourse aspires to truth; even when it is subjective, it claims to be a faithful reflection of reality. This can even be said of speculative knowledge, hence its etymology, speculum, the Latin for mirror.

Acts. Acts relate to content, and the academic kind is precisely disciplinary, like, for instance, the scientific, mathematical, or musical kind. Each discipline has canonical content that forms a syllabus that has to be learned. The information load is high, and the discourse and linguistic content are extremely dense. Academic discourse requires congruent representations for it involves the detailed description of complex events and procedures, which, in turn, call for equally intricate discourses to describe them.

Key. Attitude is relevant to the composition of discourse, and the academic kind is always employed in earnest. As true actors in knowledge production, scholars reveal new knowledge. Academic discourse addresses matters of serious concern and can even make insignificant facts seem meaningful. Any trivial issue addressed in academic discourse earns respect. Academic information also prioritizes facts over authors, thus determining the use of structures, like passives, and pronoun systems.

Instrumentality. Given its broad diversity, academic language comes in all forms of written and oral communication, whether it be machine-mediated or face-to-face. In the classroom, non-verbal language is central to knowledge transfer and shapes the expectations or involvement of audiences. In the lecture hall, speakers may declaim or use rhetorical devices to cause an effect on them.

Norms. All aspects of academic interaction are conventional, information being organized systematically and leaving little room for personal inventiveness. There is a special awareness of the forms of discourse that should be respected because texts need to be autonomous, without any situational support (exophoric references) that may help to understand them. As a result, discourse is tightly constructed and fixed. Interaction rules are well thought out and include time for questions, sitting silently, or applauding.

Genres. Genres are usually classified according to disciplines and subjects. Again, their components in the form of rhetorical devices are non-negotiable. Academic genres are often sophisticated versions of other more common ones: bedtime stories and historical accounts – a highly academic category – are narratives with the same macrostructure, which of course includes peculiarities adapted to their specific communicative intent, in this case either for sending children to sleep or for composing a great national epic.

These contextual aspects allow academic language to organize information (Snow and Uccelli Reference Snow, Uccelli, Olson and Torrance2009) in a number of ways:

Conciseness. Academic information needs to be concise and to the point, for its intention is to offer a faithful reflection of the phenomenon at stake. Truthfulness requires accurate information, and accuracy depends on how faithfully the events described are reflected. In this task, the subjective intervention of scholars is secondary for they become mere observers (observer’s fallacy). Metaphorical language is often used to illustrate complex phenomena in images, like, for instance, the double helix to describe the structure of DNA or financial necrosis to portray economic strife.

Nevertheless, overusing metaphors is regarded as misleading and frowned upon as unsustainable leaps of logic. As scholars share the same mental frame, when expressing themselves, they assume that their interlocutors also do and understand the same image, definition, or description of the situation or object in question in a similar manner. Texts are consequently coherent for the mere fact that all the interlocutors’ knowledge is underpinned by the same concepts and theories, which makes their discourse concise and to the point. As much information can easily be left out, adapting that discourse to the vernacular is almost an act of translation.

Density. As the aim of academic language is to say as much as possible in the fewest possible words, information is packed into small, high-density units, with whole sentences being condensed into propositions or phrases. This concentration tends to produce nominal structures. Nominalization is a common resource for freezing information in a process similar to packaging: verbs disappear from the sentence, their meaning being taken for granted, and readers are left with the chore of interpreting all the gaps that the missing words have left. In this vein, a violent coup d’état may be evoked in history as ‘the rising’. Similarly, in a highly elliptical process in which agents are omitted as the actors or subjects of verbal actions, the procedure whereby couples hire a woman to carry and give birth to their child is called ‘surrogacy’. This obviously puts pressure on the cognitive resources of readers because they are obliged to opt between several implicit meanings. Background knowledge and sharing common ground are essential for comprehension.

Recursion. Recursion – embedding language structures in others of the same kind in a dependency relationship – is the core mechanism of human language. The fact that units can depend on others, which in turn depend on larger ones in a never-ending process makes language infinite. The multiple levels at which recursion functions in language are established by the human capacity to register information in the short-term memory, which needs to be readily available to understand the full meaning of a sentence. The extent to which humans understand subordination – propositions that depend on others to express logico-semantic relations like causality, circumstance, and contrast – is limited to a number of levels in such a way that readers must make a concerted effort not to lose the thread. Academic discourse engages in complex processes requiring recursion, and therefore, sentences as language units with a full meaning include propositions arranged in structured layers of meaning that are hard to process.

Incongruence. The representation of technicalities and abstraction often makes language take atypical forms, that is, the way that academic language chooses to map onto real-life processes. This makes processes (actions represented by verbs) take the shape of things (entities represented by nouns). The conventional word order is also altered to facilitate reading processes and advanced cohesion mechanisms. The fact that themes and rhemes change place seems bizarre to readers, who often need to reread sentences to gain a clear understanding of their meaning, unless they are proficient in understanding different forms of information organization. Therefore, representational congruence – ‘first things first’ – is not always followed by scholars. Even though the concept of incongruent grammar sounds like a contradiction for the intrinsic logic of any grammar, the academic kind can defy the natural cognitive order.

All considered, no wonder that academic language is complex. Complexity affects readability for the simple reason that the more convoluted sentences are, the more cognitive resources will be required to interpret them correctly, and the same can be said of less frequent words. It is essential to understand that language competence depends on being accurate (error-free), fluent (spoken at the right pace), and complex (capable of expressing complex thoughts). Notwithstanding the fact that conversational language is also convoluted in its own right, academic language expresses its complexity in the intricate organization of structures.

1.3 Academic Language in an L2

The aim of academic language is to offer a faithful reflection of reality, including that of the outside world, the imagined world, the inside world, or whatever information representation resulting from the inner workings of the human brain responsible for linguistic creation (Eagleman Reference Eagleman2012; Pinker Reference Pinker2007). To achieve this, advanced language functions are needed. In academic language, a simple function like storytelling evolves into a metanarrative; joking, into educated sarcasm; and ranting, into impersonal dissent. The cognitive discourse functions (CDFs) appearing in these advanced communicative situations can be narrowed down to seven main ones that illustrate the cognitive organization of experience in language. Academic language needs to categorize, define, describe, evaluate, explain, explore, and report (Dalton-Puffer Reference Dalton-Puffer2007, Reference Dalton-Puffer2013). These functions require a firm grasp of language competence, the lack of which seriously affects expression, not an unusual circumstance when the language in use is an L2.

L2 acquisition studies have found that in all the processes involved in L2 production – conceptualizing, formulating, and parsing – cognitive resources are placed under greater pressure than in a mother tongue (Levelt Reference Levelt1993). Academic situations in an L2 may be stressful for students owing to the likelihood of communication breakdown caused by insufficient language resources, message abandonment on the part of the speaker who fails to construct a meaningful discourse, or content reduction, with the ensuing simplification of ideas and layers of meaning. The composition mechanisms used for the construction of content are affected by the fact that an L2 is being used instead (Dörnyei and Kormos Reference Dörnyei and Kormos1998; Poulisse and Bongaerts Reference Poulisse and Bongaerts1994).

Processing. Conceptual processes seem to be inhibited in an L2, with less attention being devoted to shaping ideas. As a result, L2 texts can be rhetorically less well developed. Indeed, less rhetorical content is produced in an L2, and less attention is devoted to global interpretations of texts. Moreover, there is a more localized rereading of sentences and a more frequent use of communication strategies.

Formulating. Smaller chunks and fewer words per minute are produced in an L2. Words are less easily accessible, and searching for them and considering their alternative placements and forms in the context requires more memory resources. This signifies that less attention is paid to the execution of the message, which often results in deficient production, with more errors than in an L1.

Revising. More revisions are necessary when sentences are composed in an L2, which leads, in turn, to more substitutions and deletions of original formulations. Revisions can affect conceptual, linguistic, and typographic aspects, while also operating above or below the word or clause with the subsequent additions, revisions, or substitutions to which this can lead in texts.

All in all, more cognitive resources are devoted to language processing when academic communication takes place in an L2. Even though a full grasp of the mother tongue is always unrealistic, an L2 requires higher attention levels and the optimization of the limited resources available for self-expression when language competence levels are low.

The extent to which content learning is affected by insufficient language competence is certainly a fundamental cause of school failure. Academic language is, in fact, a decisive factor in content acquisition. Proficiency in the language of schooling has a greater impact on achievement goals than general reading competence and other variables that have been addressed in the general debate on L2 acquisition, such as the age of first contact with the L2 and immigrant or socioeconomic status (Moschkovich Reference Moschkovich2015; O’Halloran Reference O’Halloran2015).

In relation to the lack of competence in the vehicular language, educational linguistics has formulated the concept of ‘L2 instruction competence’, which precisely establishes the level of expertise that facilitates learning in the less dominant tongue (Rolstad et al. Reference Rolstad, Mahoney and Glass2005). This construct has two factors: the language level and command of advanced CDFs. An important finding in this regard is that higher-order cognitive factors that contribute to proficiency in an L2 are closely related to L1 proficiency. The high correlations between proficiency scores for an L1 and an L2 show that the former is a very fertile breeding ground for the latter (Feinauer et al. Reference Feinauer, Hall-Kenyon and Everson2017; Granados et al. Reference Granados, López-Jiménez and Lorenzo2022).

It was in this context that a core distinction for understanding biliteracy was formulated. Two aspects of language use are considered in this regard: basic interpersonal communication skills (BICS) and cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP) (Cummins Reference Cummins and Hornberger2008, Reference Cummins2021).

Basic interpersonal communication skills are used to describe events occurring close to the speaker in the present, also referred to earlier as ‘here and now language’. In this respect, language as a system does not need to be self-sufficient since the information that it provides also arrives through other channels like body language and other visual stimuli that help to understand words. Bilingual research has offered a description of this communication construct. Basic interpersonal communication skills develop during the first five years of life in the innermost circle of socialization, usually in a close-knit network of family members, and are by no means negligible: an adequate control of the phonological system as a whole to convey messages, several thousand words for production which double in number as passive vocabulary, several hundred grammar rules, and the macrostructure of the major discourse categories (narration, exposition, and argumentation) in its basic form. This enables individuals to tell anecdotes and to engage in casual conversation (Ambridge and Lieven Reference Ambridge and Lieven2011; Elliot Reference Elliot1981). Basic interpersonal communication skills are the gateway to natural language, but this conversational fluency has serious limitations for major functions of individual expression, like knowledge storage and transfer.

As opposed to BICS, CALP takes longer to achieve. Up to twelve years are needed to learn to perform very advanced academic functions, like, for example, describing and understanding critical information in a history essay or debunking scientific hypotheses. To this end, it is necessary to generate an active and passive vocabulary of around 40,000 words, many of them arranged in specialized semantic fields relating to precise disciplines or professions, and the control of intricate grammatical structures with long-term dependencies, which give the impression of a very tight textual fabric in the form of a well-structured but fragile house of cards (Laufer Reference Laufer1998).

Of course, the existence of a sharp divide between BICS and CALP has been the target of some criticism, for a clear-cut boundary between the two terms is not supported by L2 acquisition theory (for a full presentation of the theory, see Cummins Reference Cummins2021; for critiques, Rolstad Reference Rolstad2017). Critiques aside, BICS/CALP bring to light a major oversight in multilingual education: the appropriate use of conversational language (playground language) is wrongly interpreted as proficiency in aspects essential to knowledge acquisition, storage, and transfer. This renders diagnosis and assessment of language proficiency imprecise. In Cummin’s own words, ‘[…] the conflation of second language (L2) conversational fluency with L2 academic proficiency contributed directly to the inappropriate placement of bilingual students’ (Cummins Reference Cummins and Hornberger2008:73).

The fact that high levels of academic proficiency are only reached after an average of seven years after the first contact with the medium of instruction, as opposed to only two years for conversational language, calls for a proper approach to advanced language in the classroom in contact with the content used for learning. Indeed, a lack of understanding of disciplinary language demands is at the root of serious educational, cultural, and social deficits, an issue addressed in the following chapters, especially Chapter 7. When conversational skills are measured with multilingual parameters in tests like the Bilingual Syntax Measure and the Basic Inventory of Natural Language, educational success is not anticipated.

The sociology of language has always pursued a formulation of language that adequately represents the extent to which individuals master the ability to reflect reality in its complexity through speech. In fact, the BICS/CALP distinction has been present in the disciplines with dyads like social versus ideational language, primary versus secondary discourse, and restricted versus elaborate code (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2000; Halliday and Hasan Reference Halliday and Hasan1976).

1.3.1 Contextual Determinants of Academic Language in an L2

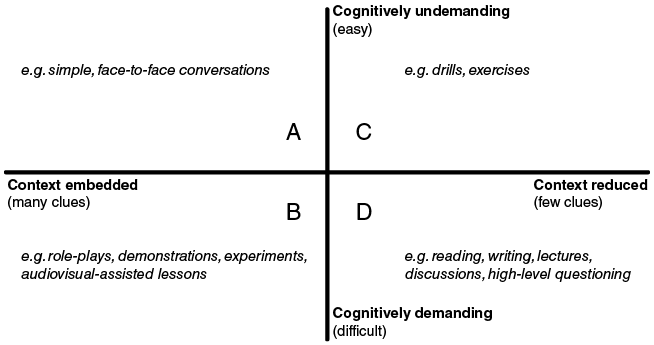

The effects of language competence on formal learning in multilingual classrooms were first represented by a quadrant diagram (see Figure 1.1). In the four quadrants formed by two axes, classroom tasks can be represented according to their language demands (Cummins and Swain Reference Cummins and Swain2014). The horizontal axis corresponds to contextualization, which conveys the idea that the existence of an ample and solid context (verbal and visual) helps to process new language information. Tasks can be ‘context-embedded’ or ‘context-reduced’. For instance, building a puzzle in pairs is a more tangible, hands-on, concrete, and therefore contextualized task than writing an op-ed piece for an international newspaper on a matter of conventional interest or making a classroom presentation on a topic included in the history curriculum. Notwithstanding curricular content, when contexts are less well defined and referents are more abstract and occur further away in time and space, background knowledge is less solid. This clearly relates to the amount of new information that needs processing and the extent to which it matches prior knowledge.

Figure 1.1 Cummins’ quadrant (Cummins Reference Cummins2000)

Figure 1.1Long description

The vertical axis ranges from “cognitively undemanding, easy” at the top to “cognitively demanding, difficult” at the bottom, while the horizontal axis moves from “context embedded, many clues” on the left to “context reduced, few clues” on the right. Quadrant A (upper-left) includes simple, face-to-face conversations (easy, context-rich). Quadrant B (lower-left) features role-plays, demonstrations, and experiments (challenging but context-supported). Quadrant C (upper-right) represents tasks like drills and exercises, which are straightforward but lack contextual clues. Finally, Quadrant D (lower-right) involves activities such as reading, writing, lectures, and high-level discussions, which are both cognitively demanding and context-reduced.

On the other hand, the vertical axis corresponds to the language demands of formal tasks. Language processing places demands on mental resources and calls for the implementation of cognitive and metacognitive strategies. Copying out a text – focusing on a sequence of words – requires less language elaboration than summarizing it – storing information in the working memory, decision-making on information relevance, or readjusting all types of composition parameters. Language interaction in a playground game of hide and seek is less demanding than note-taking in a conference room. As shown in Figure 1.1, the crossing of the two axes results in four quadrants, each with its own linguistic peculiarities.

The quadrant diagram currently relates to the BICS/CALP distinction as tasks in Quadrants A and B tend to be more balanced for posing an optimal challenge that facilitates engagement and language-level matching. The tasks in Quadrant D are more communicatively demanding, thus requiring a higher level of academic expertise, whereas those in Quadrant C correspond to exercises and drills in which the lack of a meaningful context and the deployment of the same cognitive strategies lead to a certain degree of mechanical performance. Large amounts of type-C tasks discourage engagement and active participation (Coyle Reference Coyle and Figueras2006).

The ultimate aim of the BICS/CALP distinction is to understand school success and educational promotion or their absence owing to a lack of language competence. The underlying governing principle is that language deficits give rise to the educational kind and, in a knock-on effect, further cultural deficits. This often implies that education systems ignore the linguistic causes of learning deficits while creating low academic expectations for multilingual students, which are often self-fulfilling prophecies. Whereas education attaches great importance to the early diagnosis of deficits, insufficient academic language competence often goes unnoticed.

1.3.2 The Effects of Interdependence on an L2

As a logical follow-up to the study of context, bilingual research has attempted to determine the actual level indicating the feasibility of content acquisition in an L2 in bilingual settings, which involves the formulation of two hypotheses: the interdependence hypothesis and the threshold hypothesis. The interdependence hypothesis claims that the progress made in one language – usually the mother tongue – is reflected in the full language repertoire of an individual (Liew Reference Liew1996). This was once formulated as follows: ‘To the extent that instruction in Lx is effective in promoting proficiency in Lx, transfer of this proficiency to Ly will occur provided there is adequate exposure to Ly (either in school or environment) and adequate motivation to learn Ly’ (Cummins Reference Cummins1981:29).

Research has shown that there are similarities in development across languages, which proves that academic language evolves concurrently irrespective of its actual instantiation in individual tongues, at least during mid-adolescence and for some language dimensions. For instance, language units like phrases and sentences grow longer at the same pace in an L1 and an L2 and syntax becomes more complex in all the languages spoken, as with aspects of lexical performance which are considered further on (Lorenzo et al. Reference Lorenzo2017; Granados et al. Reference Granados, López-Jiménez and Lorenzo2022).

The simultaneous evolution of an L1 and an L2 is illustrated by a two-tipped iceberg, presenting itself as distinct entities on the surface but forming a singular, interconnected mass of ice upon closer examination from underneath. This appropriate metaphor highlights the fact that the cognitive network sustaining language competence is common across the board to the point that individual languages are mere derivations of the same language acquisition process. The generative inspiration of these hypotheses is clear: all interlingual differences – phonological systems, lexicogrammatical features, and so forth – are grounded in cognitive commonalities that make individuals more receptive to the acquisition of additional languages.

The educational implications of this theory support the inclusion of the mother tongue for all learners with an eye to facilitating the subsequent acquisition of CALP in the socially dominant language at higher levels of schooling. The sudden immersion of learners in an L2 environment has been described rather dramatically, such as the claim that it can create a ‘sink or swim’ situation in which students are likely to drown in words. This is also the case with the expression ‘bilingualism with tears’, which exemplifies the anguish that a lack of understanding can cause students (Cummins and Swain Reference Cummins and Swain2014).

Alternatively, bilingual models aspire to achieve a balanced biliteracy with all the benefits that this entails (the so-called ‘bilingual edge’), which includes both linguistic (an enhanced awareness of form-function matching in words, a greater tolerance to ambiguity, and a greater ability to ignore irrelevant or redundant language input) and cognitive bonuses, like better management of higher-order cognitive strategies (Bialystok and Martin Reference Bialystok and Martin2004, Bialystok Reference Bialystok2017).

On another note, the threshold hypothesis addresses the need for a solid language baseline for the purpose of enabling learners to deal with new content in an L2. That baseline is represented as a cognitive and linguistic threshold, beyond which transfer from an L1 to an L2 accelerates and learning is enhanced (Feinauer et al. Reference Feinauer, Hall-Kenyon and Everson2017; Hulstijn Reference Hulstijn2011; Yamashita and Chang Reference Yamashita and Chang2001).

The representation of the language baseline as a threshold suggests, therefore, that a low baseline hinders literacy development, content learning, and educational success. Over the years, the original proposal has been the target of criticism on account of its description of minority individuals as deficit-laden and, moreover, for being mostly theory-based. It is true that current research has not provided a complete linguistic description of the threshold, namely, the forms and functions that need to be present for learning content in an L2. A full description of the correspondences between the knowledge structures of disciplines and their respective language forms, or in other words a full account of disciplinary literacy in maths, history, and other subjects, is needed for a proper understanding of thresholds (some steps have been taken at a pan-European level in Lorenzo et al. Reference Lorenzo, Cvikić, Llinares, de Boer, Adadan, Arias-Hermoso, Bagalová, Ćaleta, Demirkol Orak, Evnitskaya, Glasnović Gracin, Granados, Guzmán-Alcón, Kasprzak, Lehesvuori, Miloshevska, Özdemir, Piacentini, del Pozo and Ting2024). The intention of notions like scaffolding and sheltering appearing in the literature on bilingualism is to accept that the presentation of academic content needs to be language sensitive so as to encourage students to focus on the lexicogrammar beyond their grasp in class, which would gradually enable them to access new knowledge, while easing the cognitive load characterizing learning.

The threshold notion is also crucial for the simple fact that threshold matching establishes the future distinction between subtractive and additive bilingualism. The full acquisition of the advanced language of subtractive bilinguals in any tongue is limited because they lack the formal education necessary for the gradual development of advanced language and content. In contrast, additive bilinguals reap the benefits of a well-balanced control of the two languages fully developed for all uses. If L2 immersion needs to be threshold sensitive, this implies that it is necessary to explore the ways in which language is expressed in the classroom, that is, bilingual classroom discourse.

1.4 Bilingual Classroom Discourse

An L2 classroom can be a hostile environment unless the language employed in it converges with the interlanguage of students. A fundamental principle in L2 studies is that comprehension only occurs a notch above the actual language level of an individual (the classical comprehensible input hypothesis). According to the interaction hypothesis, the second fundamental law governing bilingual research, acquisition is mediated by the selective attention that learners pay to discourse and this happens more often during negotiation for meaning, when one party attempts to interpret the actual message with communication strategies like requests for clarification or for reformulation of the original content (Long Reference Long1996:414).

Language adjustments that facilitate negotiation for meaning have received many labels in different bilingual traditions, including sheltering, scaffolding, and integrating. These three concepts revolve around the precarious situation of emergent bilinguals in a foreign discourse setting. In natural language, exchanges in which there is an imbalance in language competence, as in mother–child discourse (‘motherese’), some discourse adaptation is provided in the form of adjustments. Language adjustments have foregrounded the cognitive basis of very influential theories of L2 teaching skills; that language input needs to be understood and that language output should meet the demands of the communicative act (MacSwan and Rolstad Reference MacSwan, Rolstad, Paulston and Tucker2003).

There is a consensus that classroom discourse, which has been studied from many different angles, constitutes a form of communication that differs somewhat from real-world discourse (Dalton-Puffer and Smit Reference Dalton-Puffer and Smit2012; Hatch Reference Hatch1992). Although the bilingual classroom discourse is an extension of that of the general classroom, its peculiarities stem from the crucial fact that it is content-centred, namely, that the presentation of information is related to a discipline. Consequently, bilingual classroom discourse differs in the following aspects (Jakonen and Morton Reference Jakonen and Morton2015; Llinares et al. Reference Llinares, Morton and Whittaker2012):

Distribution of talking time. In a teacher-centred approach to classroom talk, most of the talking time is taken up by the teacher, which may seem only natural but which gives rise to several asymmetries. Likewise, most of the teacher’s talking time is devoted to the formal presentation of content in the form of traditional lecturing or encouraging students to respond. The teacher-fronted technique may predominate as content ultimately needs to be presented and the teacher remains the expert. While active participation is ingrained in the very culture of L2 learning because of the impact of communicative approaches on teachers, in ordinary bilingual education, their central role as presenters of curricular content is hardly ever disputed. The role of grammar in the L2 classroom may be questioned but that of the Renaissance in art history teaching, even in an L2, is incontestable.

Distribution of turn-taking. Decisions on classroom discourse and its distribution are up to the teacher. Teachers may switch from the instructional register, in which content is presented in the canonical order of the discipline (e.g. equations come before integers in maths and the pre-Socratics before Plato in philosophy), to the regulative register which establishes the order, orientation, and organization of the classroom as part of its management. As a rule, classroom discourse tends to be of the transactional kind dominated by the teacher and interspersed with interactional episodes that structure relationships between the participants (Dalton-Puffer Reference Dalton-Puffer2007).

Structure of turn-taking. In bilingual academic discourse, turn-taking has a traditional structure of initiation, response, and evaluation, with the teacher starting the process and the students responding, which in turn prompts a reaction from the former. As students are constrained by some form of intervention in which aspects like length or topic are determined by the teacher, it is an artificial model of dialogic interaction. For instance, although students can manage turn-taking, they can only choose between continuing to speak and selecting the teacher as the next speaker. Other authors see this discourse pattern in a more positive light (e.g. Nassaji and Wells Reference Nassaji and Wells2000).

Therefore, bilingual classroom interaction is a highly hierarchical ‘two-party speech exchange system’ (Schegloff Reference Schegloff1987). When two languages coexist in the classroom, the structure of interaction may vary a great deal. The presence of a stable L2 differing from the medium of instruction encourages alternation between languages (aka. translanguaging), which gives rise to new roles and reduces the overload of information which otherwise would not be understood (Hatch Reference Hatch1992; Nikula and Moore Reference Nikula and Moore2019).

Seedhouse (Reference Seedhouse2004) referred to four different L2 classroom contexts that may well epitomize most, if not all, classroom conditions: form and accuracy, meaning and fluency, task-oriented, and procedural contexts. Based on these, the following bilingual discourse classroom situations are singled out:

Teacher’s monologue. As already noted, this is the act of teaching par excellence. As the teacher’s input operates at a fixed level of complexity, it can range from the moderately acceptable in terms of incomprehension to being way above the comprehension level of students. As their comprehension normally varies, teachers may focus on some students, while leaving many others out of the classroom dynamics. The extent to which content is shaped so language is comprehensible to the majority is, after all, the cornerstone of a quality bilingual classroom. To this should be added that students must be fluent not only in producing and understanding language but also in communicating the knowledge structures of the subject matter. This conceptual fluency increases the demands on their resources.

Teacher–student interaction. In bilingual classrooms, teachers must always be aware of the necessary linguistic adjustments. The amount of scaffolded discourse determines what can be learned when receiving new academic information. This process, which in a way epitomizes the act of learning, is at continuous risk when the language competence of students is below par. To facilitate sheltering, teachers may choose to adapt their discourse flow with strategic cues that give the floor to their students with the aim of checking their comprehension levels. Comprehension-checking devices increase the chances of identifying difficulties and can employ different discursive frames: teachers sometimes give students a ‘programmed’ opportunity to self-select; they may occasionally elicit a choral response to a deliberately incomplete utterance; or teacher–student interaction is at times relaxed to encourage the individual participation of learners (Koshik Reference Koshik2002; Margutti Reference Margutti2010; Myhill Reference Myhill2006).

Student–student interaction. Student–student interaction is a very effective knowledge-production technique. As this more intimate context can make students feel more secure and sheltered, it can be a very face-saving setting in which students feel freer to experiment with language and double-check interpretations (see Johnson Reference Johnson1981). Bilingual academic learning relies on the proper matching of content and language structures. Students need to realize how disciplinary notions take shape in language, like, for instance, how the study of ecosystems prompts the use of comparatives: some being colder, more humid, or more habitable than others.

When divided into small groups, students can be more language-focused than in teacher-fronted classroom settings. Evidently, a class split into small groups multiplies the chances of language production with a greater amount of verbal interaction. This is not without its risks, however. Students may choose to abandon their message, to give in, or simply not to use the vehicular language. Notwithstanding this, bilingual academic interaction can possess the ordinary characteristics of natural conversation without being a parasitic form of speech: simultaneous start-ups, overlaps, interpolations, or even discursive struggles for talking time may occur (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2000).

Self-talk. As a form of individual work, self-talk is a very productive technique in bilingual learning for the simple reason that it allows for private language experiments. It warrants noting that texts play a key role in bilingual settings. Students need to allow themselves the time to explore the intricacies of academic language in an L2. Solid bilingual systems include well-thought-out strategies for ordering texts in class employing tools like whole-school language plans or genre maps, in which students are required to produce or understand progressively more complex texts. Whether individually or in group discussions, these strategies can enhance text comprehension and lead to improved individual reasoning skills (Mercer Reference Mercer2000).

Student’s monologue. Delivering a monologue in an L2 requires a firm grasp of the language, as well as the individual traits essential for L2 acquisition: high motivation levels, anxiety control, and an in-depth sense of self-efficacy. When students become engaged in a monologue, they may incur some sort of discourse babbling. This is the case when they have framed the content in a speech act, forming a mental representation of the content and even a rhetorical plan to give it the proper shape. As they are lacking in L2 competence, however, words fail them and they become engaged in an incomprehensible discourse that can be a previous stage of proper communication and is therefore success-oriented. Hence, this kind of monologue benefits from a long planning phase during which students work on the rhetorical design of their interventions and establish the major milestones of their production. As in any planned output, it has an important impact on the restructuring of their interlanguage system.

1.5 Language Adjustments in the Bilingual Classroom

In bilingual discourse, teachers should not take language for granted or neglect content transmission. Questions such as how the social strata of feudal society can be understood in a less stratified contemporary world or how atomic division can be formulated in the absence of a sensory experience are content matters. Besides attention to content, in bilingual classrooms – in fact, in any classroom with just one student learning in an L2 – there is a need to be fully aware of language as a vehicle of communication, that is, the counterintuitive impression that language – not content – needs to be moulded (Tedick and Lyster Reference Tedick and Lyster2020).

As already observed, a great deal of bilingual research has addressed this very fact under different labels: sheltering (more in vogue in the United States for minority students); scaffolding (an L2 acquisition concept originally deriving from the psychology of learning), which emphasizes the fact that learning needs to be gradual and to evolve stepwise; and integrating (a core element in European Content and Language Integrated Learning [CLIL]), which again fosters the adequate matching of language and content. One way or another, they all address language adjustments.

Teachers display a wide repertoire of linguistic adjustments. Grading or finetuning, as it is also known, involves adapting normal discourse to interlanguage levels. This requires continuous self-monitoring of their verbal output (i.e. noticing and double-checking that the discourse has been properly taken in). L2 text adjustment is a central issue in language acquisition research. One of the approaches to the issue is grounded in the assumption that for input to become intake (i.e. for language flow to be assimilated and understood), correct language adjustments are needed. Another aspect that has made linguistic adjustments worthy of attention is that the correct integration of content and language in bilingual scenarios should preserve the original rhetorical macrostructures of academic language so as to prevent the language adaptation process from interfering with the actual development of the cognitive academic skills of students.

The language adjustments involved in the grading process also have a bearing on the wider debate on how language education in content areas should involve teaching the genres and discursive patterns of the discipline: the discourse of the social or experimental sciences, among others (see Fang Reference Fang2006; Gillham Reference Gillham1986; Hyland Reference Hyland, Hyland and Bondi2006; Mohan and Slater Reference Mohan and Slater2005; Musumeci Reference Musumeci1996). Briefly put, the proper integration of language and content ultimately has a bearing on whether or not students can learn, produce texts according to the dictates of the disciplinary language, and be ready to perform linguistically as actors in content areas.

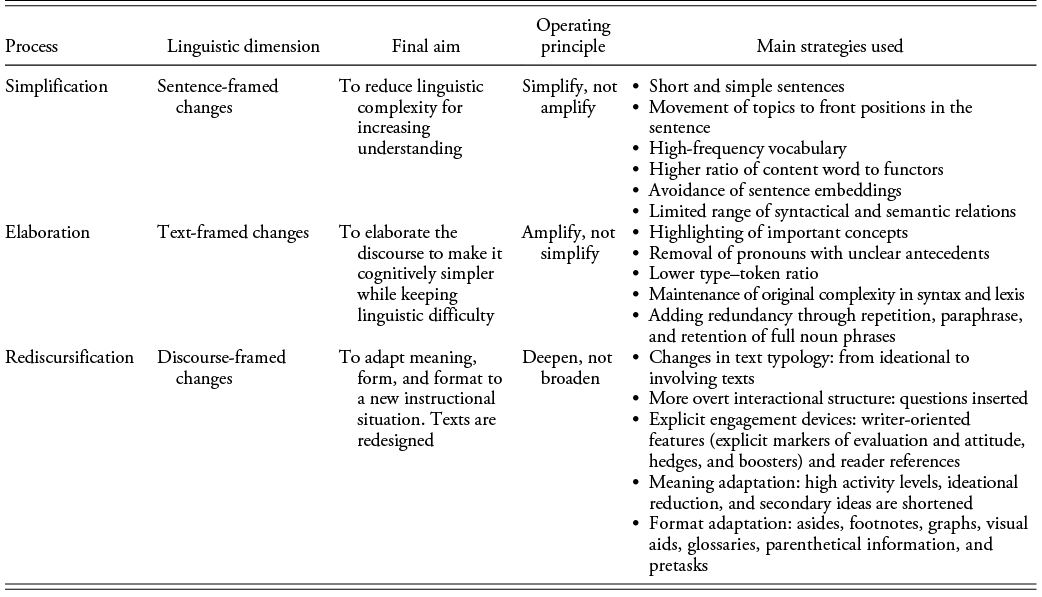

The belief that language adaptation is a process that all teachers use naturally is far from being the case. As language is often simplified so much that it could be too poor for any content to be learned at all, teachers should beware of adopting reduction strategies that make language unnecessarily and unrealistically simple, for this often results in texts containing short, choppy sentences (Adger et al. Reference Adger, Snow and Christian2018:37). Simplification can be a useful strategy, especially when it involves reducing the mean length of an utterance ([MLU]), that is, the number of words per sentence, or in texts with high lexical density, namely, with a higher ratio of content words to function words. Nevertheless, this strategy cannot be totally implemented in content-based settings where subject area vocabulary must appear (for a more comprehensive list of strategies, see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Language adjustments in bilingual discourse (Lorenzo Reference Lorenzo2008)

| Process | Linguistic dimension | Final aim | Operating principle | Main strategies used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplification | Sentence-framed changes | To reduce linguistic complexity for increasing understanding | Simplify, not amplify |

|

| Elaboration | Text-framed changes | To elaborate the discourse to make it cognitively simpler while keeping linguistic difficulty | Amplify, not simplify |

|

| Rediscursification | Discourse-framed changes | To adapt meaning, form, and format to a new instructional situation. Texts are redesigned | Deepen, not broaden |

|

Instead of simplifying the discourse, teachers may decide to reduce cognitive complexity, without having to make any major alterations to the original linguistic texture. The overall purpose of applying this strategy, as opposed to simplification, is to make meanings clear but not through language reduction. Rather, the strategies employed tend to lengthen original sentences further with paraphrasing, repetition, and appositions, among other devices. As a matter of fact, since they provide further information for contextualizing the difficult bits, elaborated texts tend to be longer and to have more words and nodes per sentence than the original (Chaudron Reference Chaudron1983; Yano et al. Reference Yano, Long and Ross1994).

A third approach is rediscursification, an adaptation strategy that does not operate on sentences or texts but only at a much higher level. Although sentences and texts are modified, changes are brought about by a discursive interpretation of the setting in which the text will be read, an educational context that is more than a mere offshoot of the original discursive situation. The new discursive reality prevails over original text retention, and only the naked macrostructure of the text is retained. Adjustments tend to be bolder, with a broader scope, for the ultimate purpose of this process is to use texts as a means of socially constructing a learning experience (Christie Reference Christie2002; Halliday and Hasan Reference Halliday and Hasan1976).

Consequently, changes may involve altering the meaning and the discourse type. As far as changes in meaning are concerned, it can entail the direct removal of ideational material (secondary ideas in paragraphs are usually lost), and the construction of new meanings that are close to, but not the same as, those in the original text. As to the second aspect, when adaptors feel that some aspects of the original text do not fit well with the new learning situation, they can employ engagement strategies for retaining the attention of readers. Among other discursive changes, adaptors can always try, for example, to turn an abstract text into a more tangible and concrete one, reshaping expository prose into narrative sequences, including, for example, high activity levels or making the author more present through explicit markers of evaluation and attitude.

By these and other means, the original text is reshaped, its purpose changing from informational (a text written simply to convey facts) to involved production (a text for introducing a new topic in class). From the foregoing, it follows that the processes described differ not only in the nature of the linguistic adjustments but also in the language level at which they are made, as well as in the effect that the adaptation is meant to have on students.

Teachers, material developers, and evaluators resort to strategies of one or the other type or a convenient combination of both to make language noticeable in the bilingual classroom. Language cannot pass unnoticed. Historical discourse, with all its twists, breaks, and clefts, can be toned down to a level that allows learning to take place.

The three strategies described earlier – simplification, elaboration, and rediscursification – whose mechanisms may overlap at times, are illustrated by the adaptations of the initial sentence of the following passage on the origin of the word ‘cathedral’ from an English original on Medieval religious architecture.

Source text: One of the earliest instances of the term ecclesia cathedral is said to occur in the acts of the council of Tarragona in 516. Another name for a cathedral church is ecclesia mater, indicating that it is the mother church of a diocese.

Simplified text: The term ecclesia cathedral was first used in the acts of the council of Tarragona in 516. Another name is ecclesia mater. It indicates that it is the mother church of a diocese.

Elaborated text: It is said that one of the earliest examples of the term ecclesia cathedral occurred in the acts of the council of Tarragona in 516. Another name for a cathedral church is ecclesia mater, which means that is the mother church of a diocese.

Rediscursified text: The term ecclesia cathedral was used for the first time in the acts of the council of Tarragona in 516. There are other names for a cathedral church, like Ecclesia Mater, Domus Dei, and the Italian Duomo.

1.6 Conclusion

Conversational, here-and-now language is different from academic, there-and-then language. They vary in their components, acquisition processes, cognitive constraints, and designations. Academic language can be described both in terms of context (based on the situation, participants, ends, acts, key, instrumentality, norms, and genres of communication) and how it organizes information – often favouring conciseness, density, recursion, and incongruence.

The use of academic language in a second language (L2) places additional strain on students’ cognitive resources, making it more challenging for them to process and produce complex messages. To learn effectively in an L2, students may need to achieve a certain level of proficiency (‘L2 instructional competence’), which involves not only a strong grasp of the language itself but also the ability to use advanced CDFs. While this idea suggests the existence of a language threshold (threshold hypothesis), research increasingly highlights the interconnectedness of all languages in a learner’s repertoire (interdependence hypothesis).

The complexity of task organization for the transmission of content via an L2 is often illustrated through a quadrant model, where tasks are categorized based on cognitive demand and the degree of explicitness of the information. Globally, however, speaking time and turn-taking patterns in bilingual classrooms tend to follow fixed, predictable structures. Also, for students to effectively engage and understand academic content, input must undertake language adjustments through a process known as rediscursification.

Certain socially relevant communicative situations require academic language. Writing essays, understanding precepts, and drafting petitions, among other things, are cultural and professional skills that facilitate integration and promotion in society. Academic language is more than style. A descriptive linguistic insight into academic language shows an increase in variation of all language indexes at all levels. Now more than ever, students should be academically proficient in more than one language. This increases the challenges that schools are expected to meet and provides further benchmarks for measuring the efficiency and quality of institutions and education systems.

Biliteracy is, however, just one single process; students do not become literate in one language and then start from scratch in an L2, until having a full command of academic skills. There is a continuous transfer of skills and strategies between languages. Bilingual programmes undertake this mission under different labels: immersion, CLIL, EMI, or content-based language instruction. A conceptualization of academic language that incorporates cognitive insights is a necessary foundation for the development of multilingual programmes so necessary in current society. This is the first step towards quality bilingual education, an old ambition of societal multilingualism.