Introduction

Ancient coins produced by individual or institutional authorities, including Roman emperors, and distributed across their territories have substantial potential as sources of evidence for the representation and communication of their authority and economic and financial policies (Kemmers, Reference Kemmers2019). Consequently, coins are valuable prescribed sources for examined school students, such as in the Roman depth study in A-Level Ancient History and the Imperial Image paper in A-Level Classical Civilisation, alongside translated poetry and prose and other material culture sources, such as sculptured monuments and statues. Coins allow Imperial Image students to explore key questions regarding the effectiveness of Augustus’ self-presentation and public image, crucial for understanding Rome’s first emperor and the creation of the Principate in context (OCR, 2023).

During my PGCE school placement at a mainstream secondary school, I observed and taught classes of Year 12 Classical Civilisation students studying the Imperial Image paper about the first Roman emperor Augustus. I became interested in what students learned from Roman coins about the emperor Augustus’ imperial image and their perceptions of pedagogies. I observed their difficulties in recognising and interpreting Roman imperial coins, some of which are prescribed sources. Accordingly, this class formed the focus of action research about the use of the digital Online Coins of the Roman Empire (OCRE) database, to support students’ learning of and attitudes towards Roman coins.

The examination board for the Imperial Image paper, the Oxford, Cambridge, and Royal Society of Arts (OCR), requires students to study six Augustan coins, three denarii and three aureii (OCR, 2023). These coins relate to significant aspects of Augustus’ self-presentation as emperor: his relationship with his adopted father Julius Caesar, religious piety and commitment to preservation of Republican law and tradition, the importance of family and succession, Augustus’ divine ancestry, and his role in bringing peace to the Roman World through war and military victory. Other prescribed sources portray these aspects of Augustus’ image, including the Ara Pacis, the Res Gestae, and the statue of the Prima Porta. Students must ‘comment on how your sources convey aspects of Augustus’ personal brand to the people of Rome and the empire’ and evaluate the effectiveness of the communication (Hancock-Jones, Reference Hancock-Jones2024, p. 107). Students should be able to identify and describe the coins and their contexts, and explain what Augustan attributes they convey, how they convey these messages to the Romans, and what possible responses audiences had (OCR, 2023). These requirements for analysis of sources including coins relate directly to the aims of the paper, which ask students to assess the effectiveness of Augustus’ self-presentation and public image. To facilitate this and encourage students to understand the prescribed sources as evoking categories of Augustus’ rule, the class teacher produced and regularly repeated a diagram with symbols summarising common Augustan attributes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The diagram produced by the Year 12 Classical Civilisation teacher to inculcate interpretive labels for Augustus’ imperial virtues displayed by prescribed sources.

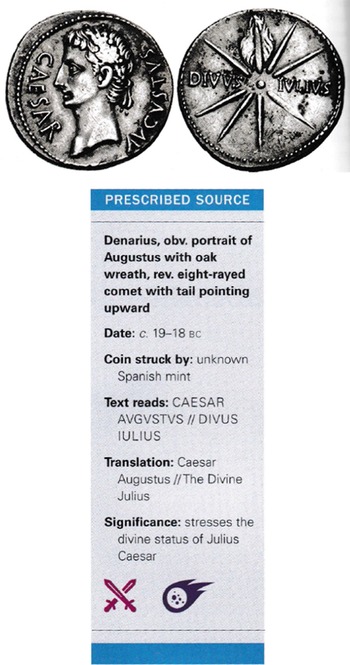

Although the students did not use the course textbook, it complements this approach. It highlights the prescribed coins and explains their historical and imperial contexts and significances for Augustus’ imperial image. The textbook features blue boxes with information about their date, authority, and significance for Augustus’ image, alongside explanatory symbols, for example, the denarius of 19–18 BC (Figure 2). The crossed swords indicate Augustus as a strong military commander and the meteor links him to the Divine Julius Caesar (Hancock-Jones, Reference Hancock-Jones2024, p. 106). The main text explains the coin’s perspective on Augustus and the political context of its production. Importantly, whilst using ‘obverse’ and ‘reverse’ and their abbreviations for the coin’s sides, the textbook describes the coin and its significance without other numismatic metalanguage, such as ‘type’, referring to the coin images, or ‘legend’ for inscriptions. This indicates that students must identify prescribed coins and understand how their imagery promotes Augustus’ imperial virtues as part of his imperial imagery without metalanguage.

Figure 2. The blue box in the OCR textbook featuring the prescribed source, the Augustan denarius, 19–18 BC. (Hancock-Jones, Reference Hancock-Jones2024, p. 160).

Despite teacher and textbook support, the students struggled to identify and use the prescribed Augustan coins, necessitating action research. For example, in a lesson when asked to name coins which showed Augustus with virtues from the pre-defined list, of the six students, three students stated they could not remember the coins’ names, dates, and details for Augustus’ attributes. Meanwhile, three students could name the dates and details of coins depicting Augustus as a Bringer of Peace and Restorer of the Republic. This indicates students’ knowledge and recall varied and required improvement. Since the course represents coins individually without the context of the Roman monetary system and coin imagery, I considered students’ ability to recognise and understand coins’ images and roles in imperial image creation would improve after using a digital tool which provides full details about imperial coins in their production series across denominations and their distribution patterns.

This tool is the Online Coins of the Roman Empire (OCRE) database which I used at university. This is an open-source linked database formed from the Roman Imperial Coins (RIC), the standard Roman imperial coins catalogues, with images, descriptions, and measurements of coins in museum collections alongside data of findspots and hoards, groups of coins often buried in times of crisis, indicating how coins were distributed in the Ancient World (ANS, 2025; Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Duyrat, Meadows, Glenn, Duyrat and Meadows2018; Gruber, Reference Gruber, Glenn, Duyrat and Meadows2018). This database, which has increased public access to numismatic collections, allowed me to explore the use of Roman imperial images on coins across and within coin denominations to establish the nature and extent of imperial images’ distribution in the Ancient World (Heath, Reference Heath, Glenn, Duyrat and Meadows2018). I researched the impact of using OCRE database on student learning of and attitudes towards ancient coins, including their motivation and engagement. The names of the school and pupils have been anonymised with abbreviations.

Context setting

I undertook action research in two lessons with a mixed-ability Year 12 Classical Civilisation class, with varying levels of experience with this subject and classical languages, at CCC, a comprehensive co-educational school in suburban Cambridge. Classical Civilisation is an optional subject from Year 7 and students are not divided by ability. CCC offers it at GCSE and A-Level and does not require students to have prior knowledge or experience. Concurrently, Latin, the language of the coin legends, is optional for higher-ability students from Year 7. Of the six regular members of the Year 12 class, two students, PD and RM, had prior experience of Classical Civilisation at GCSE, and four students, LC, EM, AM, and EG, were novices to Classical Civilisation. Meanwhile, three students had varying experience of Latin with RM, studying A-Level Latin, and LC and EM studying beginner’s Latin in extracurricular classes. Three students, PD, AM, and EG, did not study Latin. The students had varied prior attainment at GCSE, from grades 6 to 9. This means the students had mixed ability and prior experience of Classical Civilisation.

Literature review

Coins and classics classroom

Since coins are not widely taught in school classrooms, I studied how universities teach coins to students and surveyed teachers’ views about their experiences of coins.

Kemmers (Reference Kemmers2019) has demonstrated that numismatics is a specialised field with an ill-defined place in academia. There are no separate qualifications in ancient numismatics at university level. Universities do not consider it a separate discipline (Kemmers, Reference Kemmers2019, p. 4). Instead, it is part of historical and archaeological curricula in some Classics departments at postgraduate level. Undergraduates often study numismatics in broader archaeological modules, sometimes in a single lecture. Numismatists have struggled to address broader historical questions with numismatic evidence whilst communicating their work in specialist journals, such as the Numismatic Chronicle, and using methods such as die-link studies unique to the discipline (Kemmers, Reference Kemmers2019). This makes numismatics an ‘arcane discipline’, ill-defined within Classics, and not studied by most Classicists (Kemmers, Reference Kemmers2019, p. 3; Wolters and Ziegert, Reference Wolters, Ziegert, Wolters and Ziegert2017, pp. 7–8).

This paucity of knowledge can leave Classics teachers disadvantaged when teaching coins in the Classics classroom. A small anonymous survey I conducted of four Classics teachers regarding their preparation corroborates this assertion (Giles Penman unpublished Teacher Questionnaire Data). Whilst one respondent was confident in their abilities and available resources, three respondents disagreed with a statement that they were well prepared to teach Roman imperial coins. Other respondents felt underprepared and under-resourced. One indicated the specialised nature of the field at university level and scarcity of teaching materials as reasons:

I do not feel like Roman coins are widely known beyond small and enthusiastic circles of numismatists…They do not feature widely on university modules and so, I feel, are probably not something that most teachers feel confident in using…I find that most resources for Classics are patchy’.

Another respondent agreed, adding that examination specifications omitted adequate introductions to ancient coins. Some teachers feel unprepared and under-resourced to teach ancient coins due to lack of experience, corroborating Bandura’s (Reference Bandura2012) theory that self-efficacy stems from factors including successful prior experiences.

Nevertheless, coins are prescribed sources on Classical Civilisation and Ancient History examination specifications. For example, A-Level Ancient History students interpret multiple coins, including 8 denarii types in the ‘Breakdown of the Roman Republic’ paper and 28 coins of different denominations in the ‘Julio-Claudian emperors’ period study paper (OCR, 2024). The OCR specifications require learners to analyse and evaluate this and other sources, using them to create arguments about the significance of events.

Whilst teachers may have little experience of ancient numismatics, they must facilitate students in identifying and interpreting ancient coins as evidence for historical and cultural arguments.

Coins and digital technology

Two aims of my research were to explore what the practicalities of using OCRE were for students and the impact of OCRE on their perceptions of Roman imperial coins. Since no previous studies have focussed on OCRE, I explored the work of other scholars who had investigated how digital technology enhanced student learning about coins, including McIntyre et al. (Reference McIntyre, Dunn and Richardson2020) and Orchard and McIntyre (Reference Orchard and McIntyre2020).

McIntyre et al. (Reference McIntyre, Dunn and Richardson2020) studied undergraduate teaching about coins with digital technology at the University of Otago. They redeveloped an undergraduate module on Julio-Claudian emperors to include digital learning and group work to explore strategies to support student engagement with material culture in the classroom. Concurrently, they wished to increase access to and student engagement with Roman imperial coins at the Otago Museum. They tasked 35 students in 7 groups to build a digital exhibition of these coins. In two tutorials, students worked independently to identify and describe Roman imperial coins. They then worked collaboratively to identify coins and write museum catalogue labels on the Omeka platform for the online exhibition. The students divided up tasks, following Tuckman’s model of group work with alternating roles. The researchers tested the impact of group working with technology on the students’ work by comparing individual and collaborative outputs. The researchers collected student feedback at the course’s beginning and end.

Through this feedback the authors found that students learned from each other in peer-taught tutorials and gained digital and team building skills. The project changed participant perspectives about group work, who had mostly negative prior experiences, and improved student accountability. Also, students learnt to communicate their research about ancient coins to the public through a digital medium and increased public access to a local museum collection. The authors concluded that the project had improved students’ capacities to work collaboratively (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Dunn and Richardson2020).

Orchard and McIntyre (Reference Orchard and McIntyre2020) also studied a university-student-led project at the University of British Columbia teaching and learning ancient coins with digital technology called ‘From Stone to Screen’ (FSTS). After instruction about ancient coins and numismatic catalogues, students digitised the artefact collection of Classical, Near Eastern, and Religious Studies Department (CNERS), including Roman coins, using Omeka. Students taught their undergraduate peers about these coins with faculty members as mentors. The authors argued that student-led projects allowing students to conduct independent research and teach modules about ancient coins as Students-as-Partners enhanced their learning through teaching peers. This improved learning because students had to research a topic and communicate it with language and resources they themselves understood. The authors also stated that these projects enhanced student and public knowledge of and access to a local Roman coin collection.

Orchard and McIntyre’s (Reference Orchard and McIntyre2020) study corroborates McIntyre et al.’s (Reference McIntyre, Dunn and Richardson2020) findings, since both argued that digital technology increases accessibility to local coin collections and engages students in learning about coins through collaboration. These findings were important for my research using OCRE, because this suggested that my students may also engage well with coins when working together with the digital database.

Recently, the University of Warwick has released a digital database of annotated three-dimensional (3D) images of coins on Sketchfab, a 3D models website (University of Warwick Classics and Ancient History Department, 2025). This increases access to ancient coins, since users worldwide can rotate the coins to see both sides and read captions explaining their legends and images. By allowing them to manipulate the physical object in virtual space, the interactive digital environment could engage students in numismatics and improve their understanding of Roman coins.

Digital technology in the classroom and student engagement

Another important aim of my study was student engagement with OCRE, leading me to study how students engaged with digital technology more widely. Technology has now become heavily embedded in schools. Indeed, all students in both my placement schools use iPads, digital texts, and software as integral tools for learning. Teachers and education researchers have worried about their use, including in the Classics classroom. Natoli and Hunt (Reference Natoli, Hunt, Natoli and Hunt2019) raised concerns that teachers were using technology simply to use digital tools rather than to enhance their pedagogy or student learning. Similarly, other educators, such as Gibson (Reference Gibson2001), asserted that digital technologies did not improve student learning but well-planned lessons did. Accordingly, teachers should use digital technology responsibly to improve student knowledge and attainment.

Nevertheless, studies and literature reviews corroborate these findings that using digital technology in classrooms increases student engagement in learning and attainment. For example, reviewing more than 350 studies, Condie and Munro (Reference Condie and Munro2007) argued that where Information and Communication Technology (ICT) has been ‘successfully embedded in the classroom experience, a positive impact on attainment is more likely’ (Reference Condie and Munro2007, p. 4). Citing Cox et al.’s (Reference Davies, Hayward and Lukman2003) study of ICT’s impact on attainment, they asserted that using ICT had a positive effect in almost all curriculum subjects where teachers deployed practices such as planning, effective technology selection, and use. Referring to Passey et al. (Reference Passey, Rogers, Machel and McHugh2004), Condie and Munro (Reference Condie and Munro2007) emphasised ICT’s role in improving student motivation and engagement: ‘One of the most frequently cited findings is that of increased motivation and improved engagement exhibited by pupils when ICT is used’ (Reference Condie and Munro2007, p. 25). Passey et al. (Reference Passey, Rogers, Machel and McHugh2004) conducted qualitative case studies of 17 geographically disparate schools, interviews with professionals working with children, and quantitative surveys of pupils about motivational characteristics. The authors found ‘Pupils and teachers…widely reported that using ICT has positive motivational impacts upon learning…supporting positive pupil commitment to a desire to learn and to undertake learning activities’ (2004, p. 16). Teachers reported that students’ motivation improved using ICT because they could improve work quality and presentation. Indeed, most secondary students felt that using ICT made lessons more interesting, enhanced learning, and helped with homework. They also felt that ICT helped their concentration in lessons. Most parents and teaching assistants agreed that children concentrated more using ICT. Clearly, students, parents, and teachers perceive students as being more engaged in lessons and producing better work when using digital technology.

Nevertheless, important caveats remain to using digital technology. Similar to Natoli and Hunt (Reference Natoli, Hunt, Natoli and Hunt2019), Passey et al. (Reference Passey, Rogers, Machel and McHugh2004) state that ICT must be used responsibly to enhance learning. Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Hayward and Lukman2005), reviewing ICT’s impact on secondary pupils, also highlighted that motivation itself does not lead to improved attainment. Instead, students must develop cognitive skills and discipline to create learning strategies and engagement, which produces attainment. ICT must be embedded within ‘strong learning environments’ to foster improved attainment (Reference Davies, Hayward and Lukman2005, p. 11). Consequently, whilst studies show improved attainment and engagement when using ICT to teach numismatics, teachers must first create disciplined environments with expectations for ICT use and explain to pupils how using it will enhance their learning to generate engagement and attainment.

Research questions

These research papers encouraged me to focus on questions for my research. Scholarly assertions, including those of Gibson (Reference Gibson2001) and Condie and Munro (Reference Condie and Munro2007), that ICT should be responsibly embedded in well-planned lessons caused me to study how students and teachers may use ICT to improve teaching and learning and ICT’s effect on student engagement. Research suggesting that ICT can aid in teaching coins, including that of Orchard and McIntyre (Reference Orchard and McIntyre2020); Davies, Hayward and Lukman (Reference Davies, Hayward and Lukman2005), caused me to investigate the effects of using ICT on students’ understanding of and engagement with numismatics. Accordingly, my research questions are:

RQ1. What are the practicalities of using OCRE coin database as a teacher and with students and what do both learn from using it?

RQ2. What is the impact of using OCRE on the students’ perceptions of Roman imperial coins?

RQ3. What is the impact of using OCRE database on student engagement with Roman imperial coins?

Teaching sequence

I taught the Year 12 Classical Civilisation class, a sequence of two 100-minute lessons about Roman imperial coins, in their regular timetabled sessions dedicated to the ‘Imperial Image’ paper. To test the impact of using OCRE database on student knowledge of and engagement with Roman imperial coins, I taught the first lesson about imperial coins as a control with videos, and introduced OCRE in the second lesson. Whilst many teachers will not have this long to introduce and teach with OCRE, they could adapt the activities to suit the time available.

In the first lesson, I described what I would teach, and students signed consent forms agreeing to participate in the research. I explained the coin denominations in the Augustan era using images on the interactive whiteboard (IW). I then tested students’ understanding by asking them to write the denomination of the coin displayed on the IW on mini-whiteboards. I described coin parts with metalanguage using a diagram on the IW, and asked students to label the parts they could remember on a Coin Parts Sheet (CPS). I played two YouTube videos from the ‘Classical Numismatics’ channel featuring Augustan coins (Classical Numismatics, 2021; Classical Numismatics, 2025). I asked pupils to watch the videos and complete two Coin Note Sheets (CNS) with the coins’ dates, denomination, description, legends, and aspects of Augustus the coins were promoting. After questioning pupils about these details, I set them an in-class timed examination style essay question concerning the denarius depicting Augustus and Venus on CNS 1: ‘By issuing this coin, explain how Octavian (Augustus) used the benefits of divine ancestry of Julius Caesar?’ Students planned answers together and wrote answers individually. I designed lesson activities to test their knowledge acquisition and analytical skills gained from the lesson. I set the questionnaire as homework, which asked them to state to what extent they perceived they were more confident, knew more about Augustan imperial coins, and felt engaged in activities.

In the second lesson, I reminded students of the interpretive categories the class teacher had devised to interpret aspects of Augustus’ imperial image. I defined subject-specific words such as ‘denomination’ and described the main denominations – aureus, denarius, and as; their Roman audiences; and related their buying power to items students understood in the ancient and modern worlds. I introduced students to OCRE database with a printed walkthrough guide. Students used laptops and smartphones to find the website. I described how to search for a coin and what each coin’s webpage contained and defined other key terms such as ‘findspot’ and ‘hoard’.

I devised three worksheets as lesson tasks. I focussed each on a category of information about imperial coins for students to find in OCRE related to their distribution to audiences. They focussed on coin findspots and hoards (CNS 3), on coins minted in 19 BC of different denominations with different types (CNS 4), and on coins of different denominations with the same type (CNS 5). I intended these activities to facilitate students’ familiarity with OCRE and to show them how Augustus’ coins displayed different messages about him and his reign to different socio-economic classes across the Roman Empire. The students worked collaboratively and individually to find these details in OCRE and completed their CNSs. After the worksheets, I asked the students summative questions about what these details can tell Classicists about the distribution of Augustus’ image and the messages about Augustus transmitted to different audiences. I then introduced another in-class timed exam-style essay question, ‘By issuing this coin, explain how Octavian (Augustus) displayed himself as a benefactor of Rome’, related to an Augustan denarius depicting Augustus and a triumphal arch on a viaduct which students searched for and described in CNS 3. For students finishing early, I offered them the first version of CNS 3, known as ‘CNS 3.2’ in the thematic analysis. Finally, I displayed a QR code for another questionnaire asking the same questions about this lesson as the first.

Methodology and ethics

In my research, I followed Wilson’s (Reference Wilson2009) definition of action research. He considers action research as a cyclical and continual process of reflection, planning, and action, whereby the teacher reflects on the evidence of the problem, ‘tries a new approach’ (Reference Wilson2009, p. 190), and then collects data on the intervention, before reflecting on the approach’s effectiveness. I followed this by observing how the class perceived, interpreted, and remembered imperial coins as evidence of the problem. Then I taught both with OCRE as the intervention and without as the control measure, and collected data through classwork and observations as evidence of the control and intervention to allow me to reflect on the intervention’s effectiveness.

Since I wished to investigate student perceptions of imperial coins with OCRE, I chose to collect qualitative data and form quantitative data from thematic analysis of the qualitative data. As Wilson remarks, qualitative data are ‘mainly in the form of words’ (Reference Wilson2009, p. 12), which describes student worksheets and essays. Analysing these data, I employed Braun and Clarke’s six-step approach to thematic analysis because this allowed me to develop themes flexibly ‘on the basis of what is in the data’ (Reference Braun and Clarke2013, p. 178). This process involves: reading the data; coding themes; searching for themes; reviewing themes; and defining and naming themes before writing. Accordingly, I read and marked the student essays and worksheets and coded terms referring to coin parts, Augustan history, and analysis, such as ‘Legend’ and ‘Restorer of the Republic’. I sought, defined, and named themes together. Since the Classical Civilisation examination mark scheme grades students’ knowledge under the heading ‘AO1’ and analysis and interpretation under ‘AO2’, I decided to use these as my overarching themes through which to study specific themes.

I followed the ethics guidelines recommended by the British Education Research Association (BERA) and the Faculty of Education’s ethics guidelines (BERA, 2011). I discussed the research with the class teacher. All student participants read and signed consent forms before the first lesson. This form outlined the lesson sequence and asserted that participants’ work would be stored securely and kept confidential, any responses used would be anonymised, and students could withdraw from participation. Completing and submitting all questionnaires was optional.

Research methods

I collected data through my lesson observations journal and lesson evaluation sheets, written respectively during the class teacher’s lessons and after my lessons; the class teacher’s evaluations of my lesson with observations of class behaviour; student worksheets and essays; and student and teacher questionnaires.

Data and findings

For my first research question, I explored the practicalities of using OCRE coin database as a teacher and with students and what both learnt from using it. I became familiar with OCRE as a postgraduate student. The process was relatively straightforward as the search tool allows one to search coin details with a single search entry. One can either further define the results with additional search terms or begin a new search. Indeed, the use of numismatic metalanguage is consistent across all the coin entries, despite the multiplicity of RIC volumes used as source material. However, since different authors described coin types in different ways, all relevant results do not appear with every search term. This lack of standardisation can make searching the database challenging. For example, whilst the search term ‘comet’ would produce all coins depicting comets, this does not occur with the search term ‘rays’ as a descriptor, since the description styles vary between describing the numbers of rays adverbially ‘four-rayed’ and the comets ‘with four rays’. This lack of intuitive standardisation creates obstacles to finding coin types and data by producing incomplete datasets.

Students also struggled with the lack of standardisation when searching for the Augustan As on CNS 3 (Figure 3). They searched for it by its legends, ‘AAAFF’ and ‘CASINIVS’, given its common types yielded too many results. But these yielded no results, since OCRE separated these letters. This frustrated the students and hampered their completion of classwork.

Figure 3. Augustus, Rome, As, 16 BC, RIC I2, no. 373.

Despite this, three out of five respondents to the post-lesson questionnaire agreed they were more confident about imperial coins after the lesson. The same number agreed with the statement that they knew more about imperial coins after the lesson, whilst one strongly agreed. Indeed, the students did not appear to struggle finding other coins. This suggests that whilst vexing, difficulties did not prevent students learning from OCRE.

Student perceptions

For my second research question, I considered what impact using OCRE had on the students’ perceptions of Roman imperial coins. To a statement indicating increased confidence after the lesson, two students agreed and one was neutral after the first lesson, whilst three agreed and two disagreed after the second lesson. Meanwhile, regarding knowing more about coins, one agreed strongly, one agreed, and one was neutral after the first lesson, and one agreed strongly, three agreed, and one was neutral after the second lesson. Although incomplete, these data indicate tentatively that more students felt they knew more about imperial coins after the second lesson than the first but were less confident about them after using OCRE. Lack of familiarity with OCRE may have caused this lack of confidence. More time using OCRE may increase student confidence.

Quantitative results from thematic analysis reveal what the students learned from using OCRE (Figure 4). These data reveal that, whilst their interpretation of coins varied using OCRE, the digital tool increased students’ knowledge of imperial coins and use of numismatic metalanguage, as shown in increased AO1 thematic category. Students used more words such as ‘obverse’, ‘reverse’, ‘portrait’, and ‘inscription’ after using OCRE. Students wrote more detailed descriptions using coin entries on OCRE, including Latin inscriptions even without studying Latin. This complements the questionnaire’s results that most students felt they knew more about imperial coins after using OCRE. The students’ increased use of detail also indicates their focussed attention on OCRE during the second lesson. This substantiates Cox et al.’s (2003) study indicating positive effect on attainment of using ICT.

Figure 4. A table collating the results of thematic analysis of student work.

Student engagement

My third research question investigated the impact of using OCRE database on student engagement with Roman imperial coins. Whilst student engagement varied during both lessons, using OCRE created sustained focus absent from the previous lesson, corroborating research on ICT’s effect on engagement.

RM and PD, with previous experience of Classics, concentrated throughout both lessons and all activities, reflected in their consistent use of knowledge and detail. Those with no previous experience lost concentration. For example, during the videos in the first lesson, LC talked off-task to RM, looked around, and sighed. Nevertheless, the questionnaire results indicate student engagement, since two out of three respondents agreed they felt engaged in the lesson.

In the second lesson, all students were engaged using OCRE. They worked in pairs to search the database and find coins. They talked excitedly together whilst remaining on-task. Indeed, this engagement showed in the details which they noted on worksheets. Students, even those without Latin, included coin legends, types, descriptions, and dates from OCRE. The student questionnaire results corroborate my observations, since three out of four respondents stated they felt engaged during the lesson, with the fourth neutral. These observations of increased engagement and eagerness to learn whilst using OCRE accord with studies (Passey et al., Reference Passey, Rogers, Machel and McHugh2004) showing ICT increased student engagement and motivation to learn.

However, some students, including AM, lost concentration towards the end of the second lesson. They groaned audibly when asked to search for additional coins on CNS 3.2, indicating they and others became disengaged with repetitive activities. The observing teacher’s feedback also reported student engagement dropped. This corroborates research about student engagement and ICT, since Condie and Munro (Reference Condie and Munro2007) highlighted that students’ engagement may not last after the novelty fades. Lack of engagement possibly stemmed from the detailed research-orientated nature of OCRE, which may have been beyond the capacity of Sixth Form students to enjoy and understand.

On reflection, varied activities might be utilised to retain student engagement. For example, possible alternative activities include asking students to find coins depicting various animals in the quickest time. Indeed, students could also have found coins on OCRE and presented coins or curated a display. I am aware that many teachers will not have the generous allocation of time I had to teach my lesson sequences. Accordingly, I would suggest that teachers with a 40-minute lesson, for instance, may wish to allow students 15–20 minutes to familiarise themselves with OCRE and the information it contains before undertaking these activities in the latter half of the lesson.

Conclusions

Although there is no scholarship on OCRE and few studies investigate the teaching of coins and ICT, my findings corroborate existing literature. Using OCRE, students learned to look more closely at coins, their images, and legends and considered how these contributed to Augustus’ imperial image. They also used more numismatic metalanguage in their writing. Indeed, using OCRE led to a sustained period of effort and concentration, even from those previously disinterested in coins.

The challenges students experienced initially using OCRE indicate that they would need an extended period to become familiar with the software before formal learning, which was not possible at my placement. Teachers could vary the length of time spent on this familiarisation according to the length of their lessons. Additionally, to retain student interest in coins, a niche subject, teachers need to deploy various activities alongside OCRE.

However, prudent teaching with OCRE could increase students’ knowledge of ancient coins, including how distribution and denominations effected the images and messages socio-economic groups received concerning emperors. This would improve their knowledge of the use and purposes of coinage in the Ancient World. It would be useful to explore this learning potential with longer studies, due to the limits of my research with just one class.