Introduction

On 10 November 2019, Bolivian President Evo Morales was forced out of office following weeks of protest over a disputed election. While criticised for flouting constitutional limits, Morales and his Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement toward Socialism, MAS) party introduced sweeping reforms that benefited marginalised groups, including Bolivia's community of coca farmers.Footnote 1 Bolivia is one of the top world producers of coca leaf, a mild herbal stimulant that also serves as primary material for making cocaine.Footnote 2 Given its traditional roots, much Bolivian coca is produced legally and sold to domestic raw-coca consumers, but there is concern over excess production being diverted to illegal cocaine markets.Footnote 3 Like many other countries, Bolivia faces the challenge of complying with the punitive global anti-drug paradigm while considering domestic pressures pushing for less harmful drug policies.Footnote 4

This article analyses the efforts of President Morales (2006–19) in implementing the world's first supply-side harm-reduction drug policy focused on supporting legal coca farmers while sanctioning illicit coca cultivation. Morales’ efforts were constrained by previous US-supported policy that divided Bolivian coca farmers, creating divergent interests with respect to reform. In line with US pressures, in 1988 Bolivia adopted the Law of Coca and Controlled Substances (Law 1008), which closely mirrored a similar US-promoted law in Peru.Footnote 5 Law 1008 distinguished traditional coca cultivation zones from non-traditional zones; targeting the latter with militarised eradication that caused violence and social unrest.Footnote 6 Responding to this social discontent, President Morales, a coca farmer, adopted the ‘Coca Yes, Cocaine No’ (CYCN) drug programme, an innovative harm-reduction approach that distinguished coca from cocaine and expanded legal production and community control. However, the new CYCN programme coexisted with Law 1008 for over a decade.

Given the legal distinction created by Law 1008, this article asks, what was the impact of CYCN in areas of traditional and non-traditional coca production? To answer this question, the analysis takes a subnational approach distinct from earlier US-centred and cross-national approaches to Latin American drug policy. The main argument finds that CYCN was more successful in non-traditional coca areas because it was supported by strong coca growers’ organisations that united behind CYCN to successfully control coca production, while reducing violence and social unrest. Conversely, in traditional areas cocalero (coca producer) organisations evoked Law 1008 to resist CYCN reforms that expanded government control and gave non-traditional cocaleros access to legal coca production. Ultimately, the repeal of Law 1008 in 2017 ended legal protections for traditional cocaleros, thus igniting an organised resistance led by traditional cocalero organisations in the months before the disputed 2019 election that resulted in Morales’ forced resignation.Footnote 7

These findings support earlier studies on CYCN that point to improved living standards for non-traditional coca zones,Footnote 8 but also break with existing work by comparing these areas to traditional zones where CYCN was more contentious. In addition, while this article is a subnational analysis of drug-policy reform, the focus on the role of cocalero organisations in national drug policy informs broader debates about MAS as a ruling party. While MAS formed from a coalition of grassroots social movements that originated with the coca farmers’ unions,Footnote 9 some argue that social organisations lost influence when MAS ascended to power.Footnote 10 Contrary to such an approach and in line with recent findings,Footnote 11 this article finds that, at least with respect to cocalero unions at the centre of the MAS coalition, grassroots organisations maintained a powerful influence over policy outcomes. Indeed, the Bolivian case shows that supply-side harm reduction can reduce illicit crops without repression, but its success largely depends on the support and organisational strength of communities where illicit crops are produced.

The article begins by reviewing the literature on Latin American drug policies and emphasising this manuscript's contribution. The second section describes the development of coca-grower organisations in the Bolivian departments of La Paz and Cochabamba, underscoring how earlier punitive policies shaped divergent political interests. The third section offers empirical support for the dual claim that the success of CYCN varied for non-traditional and traditional coca growers, and that the strength of the cocalero organisations contributed to different local outcomes. The qualitative analysis draws from published and primary sources, including first-hand interviews in Bolivia, and a newspaper archive housed at the Centro de Documentación e Información de Bolivia (Bolivian Documentation and Information Centre, CEDIB) in Cochabamba. The concluding section points to potential implications of the findings for scholarly debates about CYCN impacts and the role of social organisations in Bolivian drug policy, and also discusses practical lessons for future harm-reduction programmes.

Prevailing Research Approaches to Drug Policy in Latin America

The subnational perspective guiding this research departs from conventional approaches in drug-policy research that view coca-growing regions as homogeneous at either the national or regional level. Such approaches primarily focus on US influenceFootnote 12 and cross-national policy comparisons,Footnote 13 but pay less attention to local variation. Studies of the US influence on drug policies in Latin America tend to cluster in two groups. One group highlights how the US-led ‘War on Drugs’ harms development, while the other group uses cross-national research to underscore the novelty of Bolivia's rejection of US policies compared to Peru and Colombia, the other major coca/cocaine producers. This article draws on these perspectives to focus on how US influence shaped early drug policy in Bolivia, which later prompted distinct reactions from traditional and non-traditional cocaleros to CYCN reforms.

The US ‘War on Drugs’ spurred considerable academic interest in the impact of US policies on development in the Global South where most illicit drug crops are produced. There is consensus that the vast power asymmetry between the United States and Latin American countries led to region-wide conformity with US interests in punitive drug strategies despite high costs. For example, Beatriz Labate, Clancy Cavnar and Thiago Rodrigues find that punitive drug strategies in Latin America led to militarisation of domestic law enforcement, which weakened democratic norms and institutions and contributed to rising human-rights violations.Footnote 14 In addition, studies link US-supported forced eradication of drug crops to increased poverty, population displacement, deforestation and pollution in frontier regions with fragile ecosystems.Footnote 15

In Bolivia, US support for militarised drug policy underwrote state violence and social unrest for nearly two decades.Footnote 16 Informed by previous findings, this study acknowledges the importance of US influence in the design of Bolivia's Law 1008 and the ensuing repression that shaped coca growers’ organisations. However, this research shows that a narrow focus on US power is insufficient to explain Bolivia's rupture with US drug policies. In fact, recent research suggests that Bolivian political elites resisted US influence even before Morales was elected.Footnote 17

Indeed, CYCN defied both the United States and prevailing top-down academic theories of US−Latin American relations. Moreover, cross-national analyses highlight Bolivia as the only Latin American country to significantly depart from the punitive paradigm and thus exclude the United States from national drug-policy decisions.Footnote 18 In 2008, Morales expelled the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) from Bolivia and allowed all United States International Agency for Development (USAID) programmes to lapse from 2009 to 2013.Footnote 19 The United States penalised Bolivia for these actions by decertifying it for over a decade, but this did not derail Bolivia's reform agenda.Footnote 20

To account for CYCN as a major deviation from US interests and prevailing policy outcomes in Latin America, previous studies stress the political capacity of Bolivia's coca growers’ movement.Footnote 21 In particular, the cocalero unions in the non-traditional coca region of Chapare played a pivotal role in propelling their leader, Morales, to national power.Footnote 22 In contrast, weaker cocalero organisations in Colombia and Peru are linked to persistent punitive policies and more violent repression.Footnote 23 These studies of cocalero organisations, combined with claims that grassroots organisations largely lost influence after MAS formed a government,Footnote 24 directly inform the questions and arguments that frame this study. Given the significance of the Chapare cocalero unions to Morales’ electoral success, how did coca growers’ unions shape the implementation of CYCN while Morales was in office? Moreover, how was the experience of CYCN different for Chapare unions, criminalised under previous law, compared to organisations representing traditional growers?

In addressing these questions, this article aims to expand on studies linking CYCN to better living standards in Chapare, a non-traditional zone that experienced less repression, more economic security and less illicit coca production, by adding comparisons to CYCN outcomes in traditional coca zones.Footnote 25 Since traditional and non-traditional coca farmers fared differently under previous coca law, it is reasonable to expect distinct reactions to and experiences of CYCN in different areas. Moreover, the comparative framework provides a broader account of how CYCN impacted longstanding conflicts over access to legal markets for coca that divide coca-growing communities. Finally, the article highlights the important role of coca growers’ organisations in shaping CYCN outcomes, thereby corroborating other studies that suggest rural social organisations maintained significant influence within the MAS coalition.Footnote 26

The Coca Growers’ Organisations

Starting in the 1980s, the United States tried to curb soaring domestic cocaine consumption by influencing policies in the Andean producer countries. In Bolivia, US pressure to eradicate coca undermined the already precarious conditions of highland farmers. To balance contradictory demands between US anti-coca efforts and domestic coca-leaf consumption, the Bolivian government devised Law 1008 as a policy to reduce coca output while preserving the market for coca leaf. To do so, it distinguished between traditional and transitional/illegal coca cultivation. This strategy divided coca growers in traditional and non-traditional areas, thus creating conflicting political interests with respect to the coca policy and later causing distinct reactions to CYCN. While traditional cocaleros mostly supported Law 1008, coca growers’ organisations in non-traditional Chapare mobilised against eradication campaigns under Law 1008 and formed the MAS as an electoral route to change drug policy by winning elections.

During the 1980s, US-led coca-eradication campaigns threatened the cultural identity and economic wellbeing of Andean peoples who have cultivated and consumed coca for centuries. In contemporary Bolivia, 30 per cent of people consume coca leaf, and nearly 80,000 farmers depend on the legal coca market for their livelihood.Footnote 27 Yet, as a signatory state of the 1961 United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, Bolivia committed to categorise coca leaf as a Schedule 1 dangerous substance, and called for an end to traditional coca consumption within 25 years, or by 1986.Footnote 28 Increasing global cocaine demand boosted coca production in the Andes beyond traditional zones, motivating peasants and unemployed miners to migrate en masse to establish coca farms in remote areas.Footnote 29 The production of illicit coca and cocaine skyrocketed, and the United States responded with military interventions and aid programmes designed to strengthen government capacity to repress coca production and trafficking. In reaction, coca growers’ organisations in Bolivia resisted US anti-coca pressures.

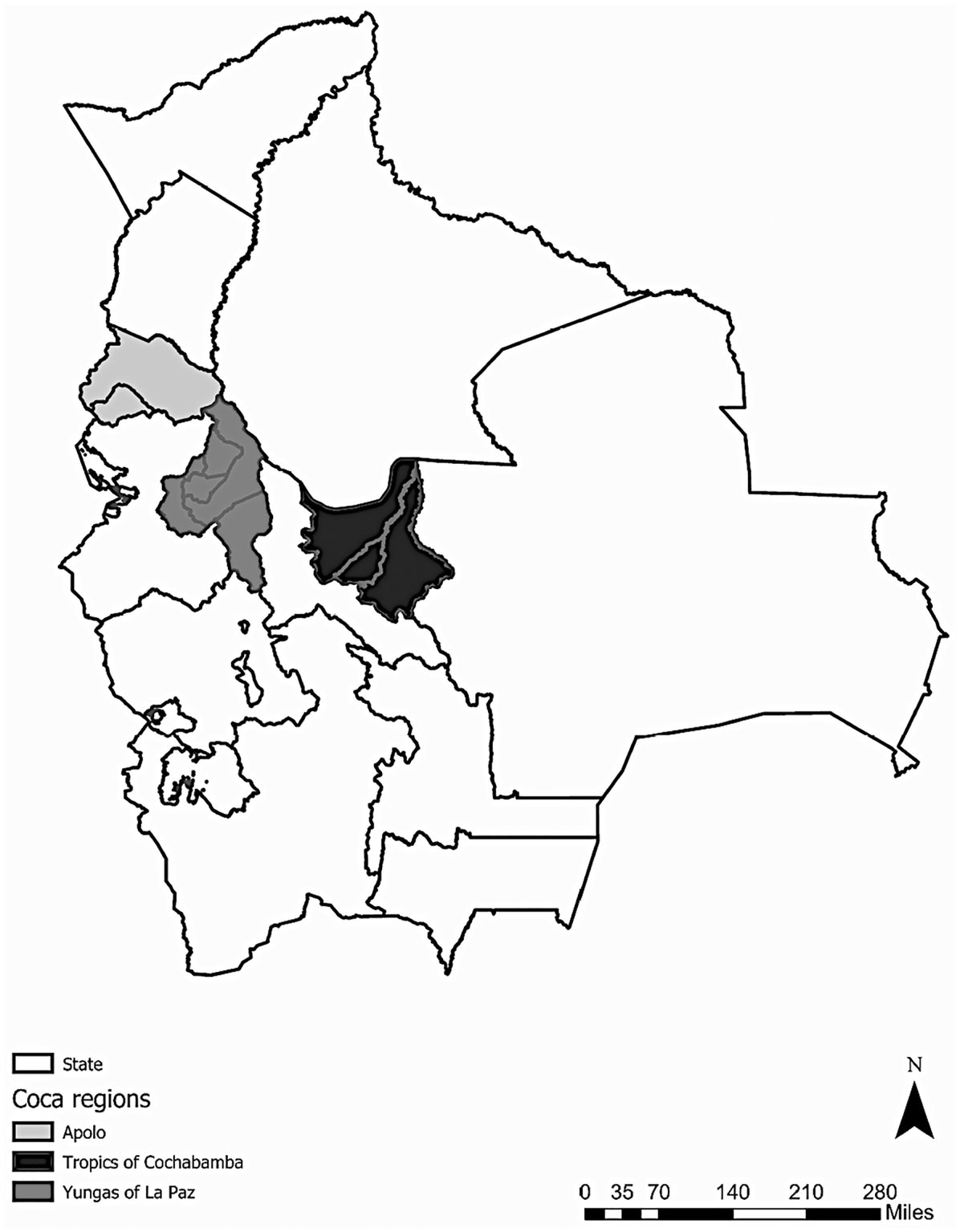

Figure 1 shows the three main coca-producing areas of Bolivia: the Yungas and Apolo in the department of La Paz, and Chapare in the department of Cochabamba. In the Yungas of La Paz, the first area of interest, powerful peasant unions representing traditional cocaleros resisted the implementation of CYCN reforms after 2006. The coca cultivation in the Yungas pre-dates Bolivia's 1952 Revolution and subsequent agrarian reform. From the colonial period until 1952, the Yungas coca trade was dominated by politically powerful hacendados (hacienda owners) that successfully lobbied against early international efforts to limit coca production.Footnote 30 Currently, the nearly 28,000 authorised coca farmers in the Yungas include established families that have cultivated coca for generations in ‘traditional’ areas formerly occupied by the haciendas, and new settlements that are considered non-traditional coca areas.Footnote 31 After 1988, Law 1008 created a legal distinction between the traditional and non-traditional areas in the Yungas, shielding coca cultivation in the former while leaving the latter vulnerable to eradication. In this way, Law 1008 divided the Yungas community over coca production, and tied the interests of traditional Yungas cocaleros to the conservation of Law 1008.

Figure 1. Main Bolivian Coca Regions

Source: Author's elaboration based on data from UNODC, ‘Bolivia Coca Cultivation Survey’ (2016).

Cocalero organisations formed in the Yungas of La Paz in the aftermath of the 1952 Revolution that brought to power the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (Nationalist Revolutionary Movement, MNR), a political party led by middle-class professionals and supported by organised labour that overthrew Bolivia's governing oligarchy.Footnote 32 In 1953, the MNR implemented agrarian reform to dismantle large landholdings and incorporate the peasantry into the revolutionary project.Footnote 33 In the Yungas, MNR promoted agrarian unions at each hacienda to decide the allocation of plots and petition for titles. With the undoing of the agrarian elite, peasant unions quickly usurped political authority from hacendados and their role as defenders of coca leaf against government efforts to limit production.Footnote 34

During the Morales presidency, the Yungas unions coordinated at the regional and provincial level to negotiate with the national government over CYCN implementation. In the 1950s, clusters of unions in the Yungas formed regional centrales (congresses of unions) which united into provincial federations.Footnote 35 By 1960, there were six independent federations in the Yungas incorporated under the departmental peasant federation and the national peasant confederation.Footnote 36 The local unions provided dispute resolution and managed communal infrastructure but did not intervene in productive activity.Footnote 37 However, unions expanded their role during the 1980s in response to government threats to restrict coca production, as well as a desire to protect producers against powerful market intermediaries.

In 1985, Yungas peasants created the Asociación Departamental de Productores de Coca (Departmental Association of Coca Producers, ADEPCOCA) as the economic wing of the agrarian unions. In addition to organising protests against coca production limits, ADEPCOCA issued producer licences allowing holders to cultivate and trade coca directly in La Paz without securing the expensive commercial licence required for coca traders, thus undercutting market intermediaries.Footnote 38 As Alison L. Spedding explains, ‘[by] showing this card, it is possible to take coca to the city and sell it without paying duty or risking arrest’.Footnote 39 To join ADEPCOCA, producers must have the endorsement of their local union, pay a membership fee and register the quantity of land used to cultivate coca.Footnote 40

The second area of interest, Apolo, is a much smaller area of traditional coca cultivation found in northern La Paz, far enough away from the Yungas to constitute a separate region, but close enough to coordinate with Yungas cocalero organisations to shape CYCN outcomes. In 2004, the United Nations recorded a mere 289 hectares of visible, traditional coca in Apolo, concentrated in the southern province of Bautista Saavedra where coca cultivation pre-dates the 1953 Agrarian Reform.Footnote 41 In this area, ADEPCOCA works with five centrales comprising local agrarian unions. While historically small, the number of coca farmers in Apolo expanded rapidly during Morales’ presidency from 2,500 in 2008 to more than 7,000 by 2015, causing increased cultivation outside the traditional zone.Footnote 42

Finally, in Chapare, an area of mostly non-traditional coca cultivation and the third area of interest, peasant unions played a pivotal role in supporting the implementation of CYCN reforms. These powerful agrarian unions formed after the 1953 Agrarian Reform in response to frontier colonisation. Following the Agrarian Reform, land plots became smaller in the highlands and the MNR government encouraged peasants to colonise Chapare, a semi-tropical lowland area east and north-east of the city of Cochabamba, and other frontier regions. As colonos (settlers) arrived in the 1960s, agrarian unions, fashioned from both highland Indigenous and peasant organisational structures, emerged as the governing authority in the absence of state presence. Colonos registered with their neighbourhood union and received a parcel of land in exchange for monthly dues and communal labour.Footnote 43

Early Chapare settlers cultivated other crops alongside coca, which took off with the booming US demand for cocaine in the 1980s.Footnote 44 By the mid-1990s, there were nearly 700 cocalero unions in Chapare.Footnote 45 As occurred in La Paz, the male-dominated Chapare unions organised hierarchically so that several unions formed a central, and several centrales united into a federation. Eventually, the regional federations of Chapare formed the Seis Federaciones del Trópico de Cochabamba (Six Federations of the Tropics of Cochabamba, hereafter Six Federations) representing over 900 unions with 46,240 registered growers by 2015.Footnote 46 After 2006, the Six Federations worked closely with the Morales government to ensure the effective implementation of CYCN. However, initially, with no government presence, the Six Federations functioned like the coca growers’ federations in La Paz, supporting communal infrastructure and settling disputes but not managing production. A key difference between the two regions, however, is that in Chapare there is no organisation like ADEPCOCA, thus leaving the commercialisation of coca in the hands of intermediaries who purchase coca from producers in Chapare without opposition from the unions.Footnote 47

Despite some important differences, coca growers’ unions in La Paz and Cochabamba were powerful organisations with similar structures and functions prior to the government crackdown on coca in the 1980s. In response to US pressure, Bolivia passed Law 1008 in 1988, which created three types of coca cultivation zones: traditional, transitional and illegal, and considered varying levels of protection and repression. Traditional areas were zones in which coca cultivation pre-dates the 1952 Revolution, including most of the Yungas of La Paz, and much smaller areas in Apolo and the Yungas of Vandiola, south of Chapare, in Cochabamba.Footnote 48 Traditional areas were limited to 12,000 hectares of planted coca that could be sold through legal markets in La Paz and in Cochabamba. Transitional zones, including most of Chapare, faced mandatory eradication with the potential for alternative development or compensation from the government. Coca in illegal areas, or most new settlements, could be eradicated without compensation. The government carried out eradication campaigns using a new US-financed militarised police force called the Unidad Móvil Policial para Áreas Rurales (Mobile Police Unit for Rural Areas, UMOPAR).Footnote 49

Law 1008 fundamentally reshaped the political interests and organisational capacities of the coca growers’ unions in La Paz and Chapare with consequences for CYCN implementation later on. The law protected traditional Yungas growers from eradication,Footnote 50 but also expanded state control of legal markets and increased pressures on traditional growers to participate in paid voluntary eradication.Footnote 51 Most importantly, Law 1008's limit on legal production exacerbated a growing divide between the traditional growers and non-traditional coca farmers that colonised the outskirts of the Yungas. Traditional growers sought to exclude new settlements from cultivating within the 12,000-hectare limit established under Law 1008 to protect their legal production monopoly.Footnote 52

During the 1990s, conflicts between traditional and non-traditional coca growers in the Yungas of La Paz formed the basis of a conflict between ADEPCOCA, representing traditional zones, and the Consejo de Federaciones Campesinas de los Yungas de La Paz (Council of Rural Farmers’ Federations of the Yungas of La Paz, COFECAY), an umbrella organisation created in 1994 incorporating all Yungas federations and serving as their representative in negotiations with the government. However, COFECAY had limited authority and regional federations with dissimilar interests continued to negotiate independently with the government on voluntary reduction agreements.Footnote 53 While COFECAY struggled to represent all Yungas growers, ADEPCOCA emerged as the more powerful organisation. In defence of the economic interests of cocaleros in traditional areas, ADEPCOCA denied licences to many colonos and later welcomed government efforts to demarcate the fuzzy boundaries of the traditional regions so that they could exclude new coca settlements.Footnote 54 Finally, from the 1980s, ADEPCOCA obstructed government plans to control coca production and commercialisation, sanctioning affiliates who voluntarily eradicated their plots or received alternative development aid.Footnote 55

In contrast to the Yungas of La Paz, most coca grown in the Chapare region of Cochabamba was dubbed transitional and subject to mandatory eradication.Footnote 56 The only exception was the traditional Yungas of Vandiola, with just 736 registered coca growers in 2015.Footnote 57 Chapare included primarily Quechua-speaking peasants from distinct regions and some ex-miners.Footnote 58 In 1978, a young Morales and his family moved from the Oruro department to Chapare and eventually joined the cocaleros. At that time, there was no government regulation of the number of producers or the size of coca plots. However, Law 1008 initiated a period of government repression in Chapare using sustained military presence and forced eradication, which faced fierce resistance under the command of Morales, who emerged as the principal leader.

In the absence of democracy, state repression is associated with weak social movements.Footnote 59 However, state repression during political liberalisation can ignite and strengthen sustained protest.Footnote 60 In Bolivia, Law 1008 came into effect after Bolivia's 1982 transition to democracy and numerous studies document how government repression derived from Law 1008 forged the politicisation and mobilisation of Chapare unions.Footnote 61 A key catalyser of these developments was the influx of tin miners in Chapare who brought their experience in political militancy. However, punitive drug policies provided the main incentive for unifying the Six Federations.Footnote 62 In 1992, in response to state repression, the Six Federations united under one structure, the Coordinadora de las Seis Federaciones del Trópico de Cochabamba (Coordinator of the Six Federations of the Tropics of Cochabamba, hereafter the Coordinadora), affiliated with the national peasant organisation Confederación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia (Single Trade Union Confederation of Peasant Workers of Bolivia, CSUTCB). The Coordinadora provided outward unity and internal discipline to mobilise the base in resistance efforts, including marches, protests and hunger strikes.Footnote 63

Existing research finds that electorally secure governments in new democracies are more likely to escalate repression in response to social resistance.Footnote 64 Following the crisis-plagued presidency of leftist Hernán Siles Zuazo (1982–5), the Bolivian Left was in electoral decline, leaving the Right to dominate national politics throughout the 1990s and escalate repression against Chapare growers.Footnote 65 The Chapare coca struggles peaked in 1998 with the initiation of Plan Dignidad (Dignity Plan), a militarised eradication campaign that reduced Chapare coca from 31,500 to 6,000 hectares, and caused the death of 25 cocaleros and left hundreds more injured or detained.Footnote 66 During this period, Morales, president of the Six Federations, led a successful grassroots resistance against repressive drug policies. In 1994, the Six Federations allied with other sectors that led to the creation of the MAS in 1998 as a mass movement and party.Footnote 67

After a decade of confrontation, the Chapare cocaleros won a major victory with the 2004 Cato Accord during the Carlos Mesa presidency (2003–5). The accord provisionally permitted Six Federations affiliates to cultivate a cato of coca (1,600 square metres), immediately adding 3,200 hectares of coca for Chapare on top of the 200 hectares already permitted to traditional growers in Vandiola.Footnote 68 President Mesa backed the accord under pressure of extreme political instability and public outcry over violence against coca farmers.Footnote 69 In exchange for cato rights, or the legal right to cultivate up to a cato of coca, the government required Six Federations affiliates to register and measure their coca fields to monitor production in Chapare, something not required of traditional producers.Footnote 70 In addition, cato rights were exclusive to union members, a provision that empowered the Six Federations to extend or revoke affiliates’ cato rights, within the regional production limit set by the national government.

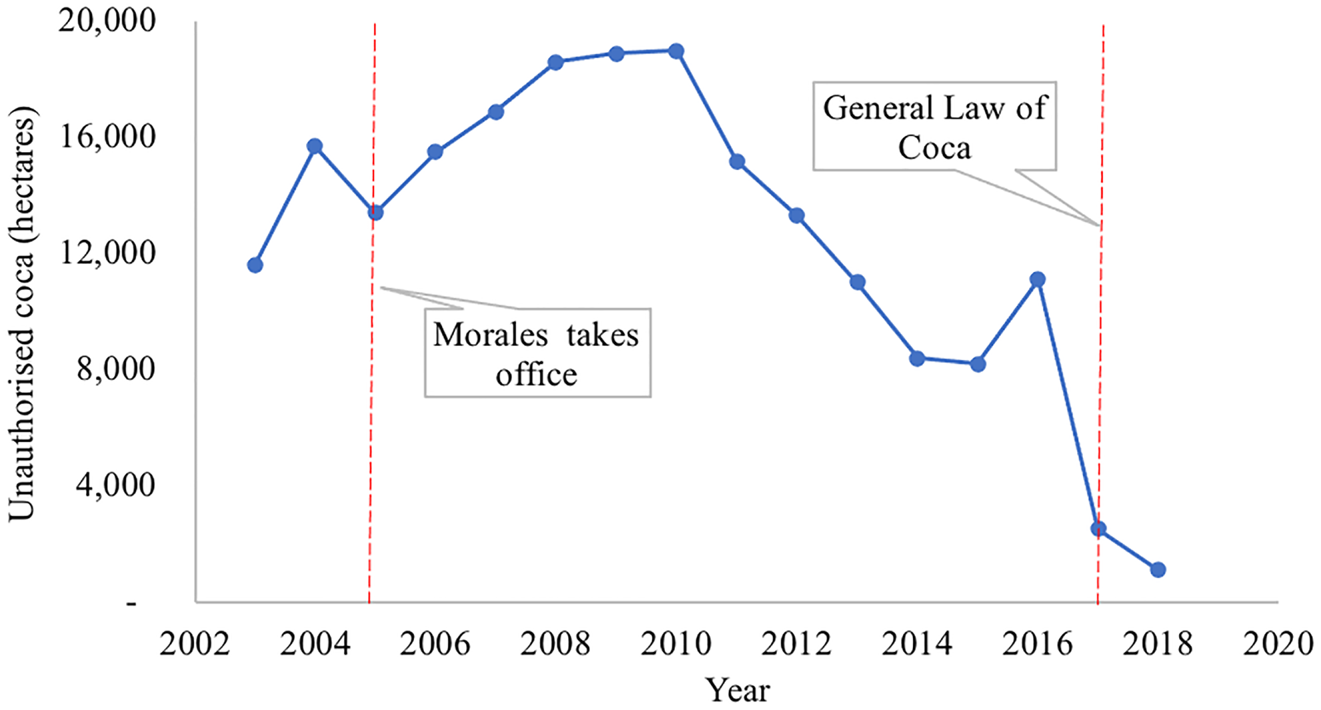

In Bolivia, resistance to punitive drug policies between 1988 and 2004 coincided with broader struggles against neoliberal reforms that forced the resignation of two presidents and led to the election of Morales in December 2005.Footnote 71 When Morales took office, he upheld the Cato Accord and initiated CYCN, a four-pronged coca-control strategy making a sharp distinction between coca and cocaine, expanding legal coca production, enabling community-based policing of the cato limit, and promoting exports of industrial coca products.Footnote 72 The data presented in Figure 2 suggests that these policies reduced unauthorised coca cultivation in Bolivia.Footnote 73 However, for most of his presidency, Morales worked within the parameters of Law 1008, which contradicted basic tenets of CYCN, thus creating ambiguities and deepening conflicts amongst coca growers, and in some cases between cocalero organisations and the MAS government.

Figure 2. Unauthorised Coca Cultivation in Bolivia (in Hectares), 2003–18

Source: UNODC, ‘Bolivia Coca Cultivation Survey’ (all years 2004–19); unauthorised cultivation calculated by subtracting authorised hectares from total hectares produced per year. For 2004–16, Law 1008 authorised 12,000 hectares; for 2017 and 2018, the General Law of Coca authorised 22,000 hectares.

CYCN in the Regions

This section analyses the CYCN implementation from three angles. The first two subsections describe CYCN implementation in Cochabamba and in La Paz, respectively. The third subsection describes the replacement of Law 1008 with the General Law of Coca (Law 906) in 2017 as a contentious process that ignited an organised opposition against MAS in the Yungas of La Paz. The analysis supports two main analytical points that frame this article. First, CYCN was more successful in Chapare than in La Paz. Second, these different CYCN outcomes are linked to strong cocalero organisation that emerged from agrarian reform in La Paz, and from frontier colonisation in Chapare. Organisations representing traditional cocaleros, predominantly in La Paz, resisted CYCN because the reforms threatened the special status of traditional coca zones under Law 1008 by expanding access to legal coca markets. Conversely, ‘non-traditional’ cocalero organisations, predominantly in Chapare, embraced CYCN because it legalised coca cultivation for their sector. The success of CYCN in Chapare indicates that harm reduction works to control illicit cultivation, but effectiveness may be contingent on strong local organisations.

Coca Control in Cochabamba

The success of CYCN in Chapare is linked to strong cocalero organisations that enforced compliance among affiliates and secured government support for alternative development. As the previous section discusses, the Six Federations derived legitimate authority from the unions’ historic role as a source of local governance in frontier regions. Moreover, union authority and organisational capacity expanded during decades of resisting forced eradication under Law 1008. The Six Federations were at the centre of the social coalition that elected Morales, and primarily demanded ending forced coca eradication. As such, federation leaders supported and successfully implemented CYCN reforms, overcoming some reluctance from local farmers as well as a more organised resistance from traditional cocaleros in the Yungas of Vandiola.

The Six Federations’ support for CYCN and local enforcement capacity was vital to the success of CYCN precisely because farmers in transitional zones faced strong incentives to defy the cato limit. Indeed, the Cato Accord ended the wholesale criminalisation of the area's coca farmers but a cato alone did not yield sufficient income for many households.Footnote 74 While recognising coca control as a public good that benefited the community, individual coca farmers preferred for others to bear the economic risk of reduced production.Footnote 75 Hence, between 2006 and 2009, widespread violations of the cato limit threatened to delegitimise CYCN as a coca-control strategy, and Morales’ early efforts to eradicate excess coca in Chapare spurred resistance.Footnote 76 For Morales, the dilemma in Chapare was compelling compliance without repression, thereby appeasing both the international community and his core constituency. To accomplish this, Morales harnessed the Chapare unions’ authority and political unity behind the MAS to implement a policy of ‘social control’, a community-based plan for enforcing the limit in the Cato Accord with minimal repression, in exchange for government-supported development projects.

The social control element of CYCN provided an innovative system of social and economic incentives for coca growers to self-regulate and self-govern, achieving coca control as a collectively beneficial outcome in the absence of force.Footnote 77 The federations and local unions worked with the Unidad de Desarrollo Económico y Social del Trópico de Cochabamba (Economic and Social Development Unit of the Tropics of Cochabamba, UDESTRO), a state agency managed by coca growers. Each federation and union had a social control representative, who was also the local affiliate in charge of enforcing compliance with the cato limit.Footnote 78 Periodically, union representatives visited farms and marked excess coca for eradication.

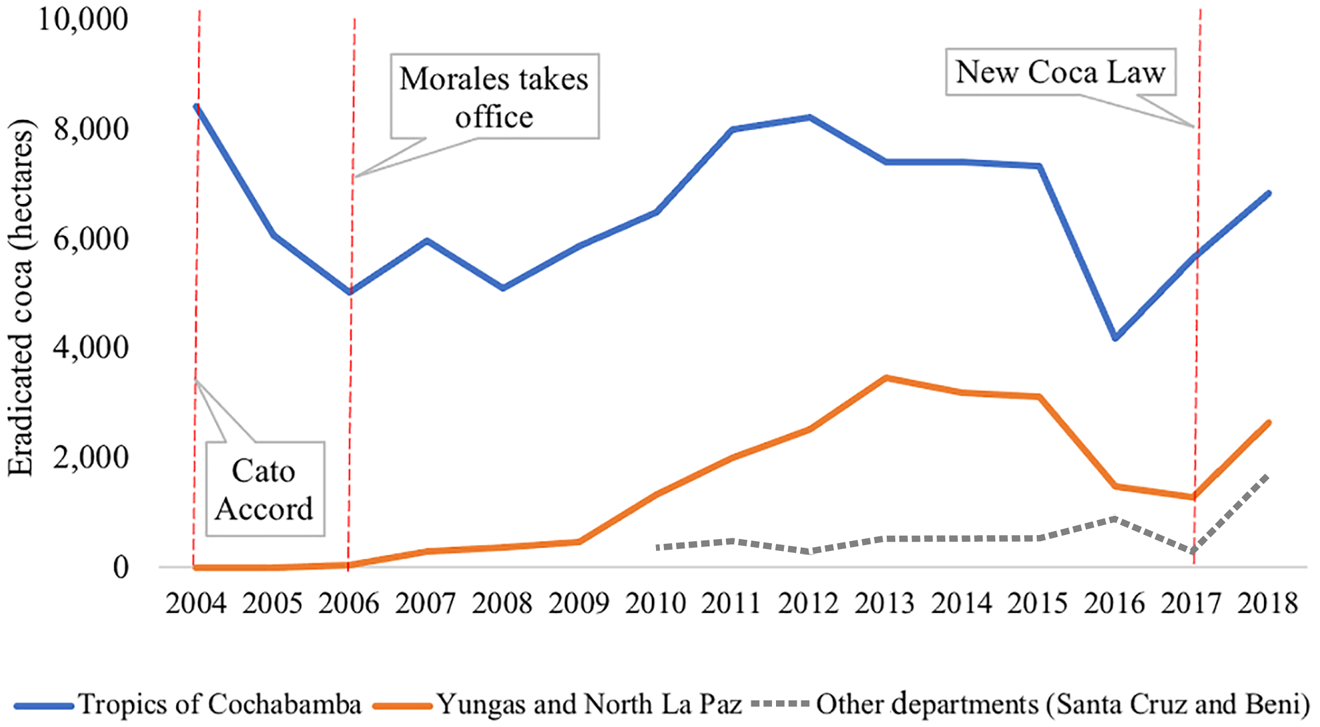

Typically, union leaders permitted violators to eradicate the surplus themselves prior to initiating a process with UDESTRO. However, when UDESTRO enforced compliance, it revoked a grower's cultivation rights for one year and the military-police Fuerza de Tarea Conjunta (Joint Task Force, FTC) eradicated the entire coca field. UDESTRO enforcement was infrequent because affiliates generally responded to union demands, making social control remarkably successful at reducing illegal coca.Footnote 79 Indeed, under CYCN the important change for Chapare was not how much coca was destroyed, but that eradication was done voluntarily. As Figure 3 demonstrates, while eradication increased in La Paz, more coca was destroyed voluntarily in Cochabamba.

Figure 3. Coca Eradication in Bolivia by Region, 2004–18

Source: UNODC, ‘Bolivia Coca Cultivation Survey’ (all years 2005–19).

Six Federations leaders interviewed by the author in 2016 enthusiastically supported social control and CYCN more broadly even though it meant limiting regional coca production. They considered social control protective of the Cato Accord and necessary to avoid repressive policies. One union leader who resisted alongside Morales in the 1990s explained, ‘We have to demonstrate that we are cooperating … to defend what we fought so hard to win.’Footnote 80 Nonetheless, not all farmers agreed with union leaders on coca control.Footnote 81 Indeed, many Chapare residents begrudged strict cato enforcement. To account for widespread compliance with the cato limit despite some dissent, previous studies point to the authority of cocalero organisations.Footnote 82 As explained in the previous section, the coca growers’ unions derived authority from their historic role as sources of local governance in an otherwise stateless frontier. Moreover, affiliates directly elected union leaders, instilling their authority with even greater legitimacy. Hence, union-imposed sanctions for violations of the Cato Accord were respected albeit sometimes unpopular. Sanctions for violating the cato limit might include relinquishing coca cultivation rights, land confiscation and expulsion from the community.Footnote 83 Within the first five years of social control, the Six Federations sanctioned about 800 affiliates for violating the Cato Accord.Footnote 84

Union leaders sometimes abused their authority for political purposes by silencing opposition to MAS and President Morales, who remained president of the Six Federations after taking office. For example, some cocaleros, including an ex-cocalera interviewed by the author, report that they were fined or expelled from Chapare for openly criticising MAS.Footnote 85 Censoring anti-MAS critics could be interpreted as an indication of MAS government ‘co-optation’ over union leaders. However, a closer analysis reveals that allegiance to MAS largely depended on government accountability to local cocalero organisations. For example, Morales ignited a small defection in 2015 when he rejected the union's mayoral candidate in Shinahota, a municipality in Chapare. While Morales and some union affiliates settled on another candidate, a group of disgruntled cocaleros, who were later expelled, reacted by registering their own party called Unidos por Cochabamba (United for Cochabamba, UNICO), which won a significant 28 per cent of votes compared to 66 per cent for MAS.Footnote 86 While Chapare unions stifled political dissent to MAS, the union base ultimately controlled MAS candidate lists, so that local MAS officials answered to the union.Footnote 87

Another indicator of cocalero organisations’ strength in Chapare is that, in contrast to previous government administrations that defaulted on promised compensation for coca eradication, the unions conditioned political support for MAS on receiving government aid for development. The Morales government allocated US$350 million to support alternative development projects including two processing plants for exporting locally grown produce and a highway facilitating transport to regional and international markets.Footnote 88 These programmes supported diversified production in Chapare, even as a broader initiative to industrialise coca-based products, a major goal of CYCN, was unsuccessful. In 2006, Morales created Empresa Boliviana Comunitaria de la Hoja de Coca (Bolivian Community Company of the Coca Leaf, EBOCOCA) and built a plant in Chapare to produce coca-based commodities (e.g. coca cookies and toothpaste). EBOCOCA initiated production in 2008 under the management of the Six Federations. However, national demand was not enough for generating profits and plans to export coca-based products failed despite Morales’ efforts to decriminalise coca leaf at the international level.Footnote 89

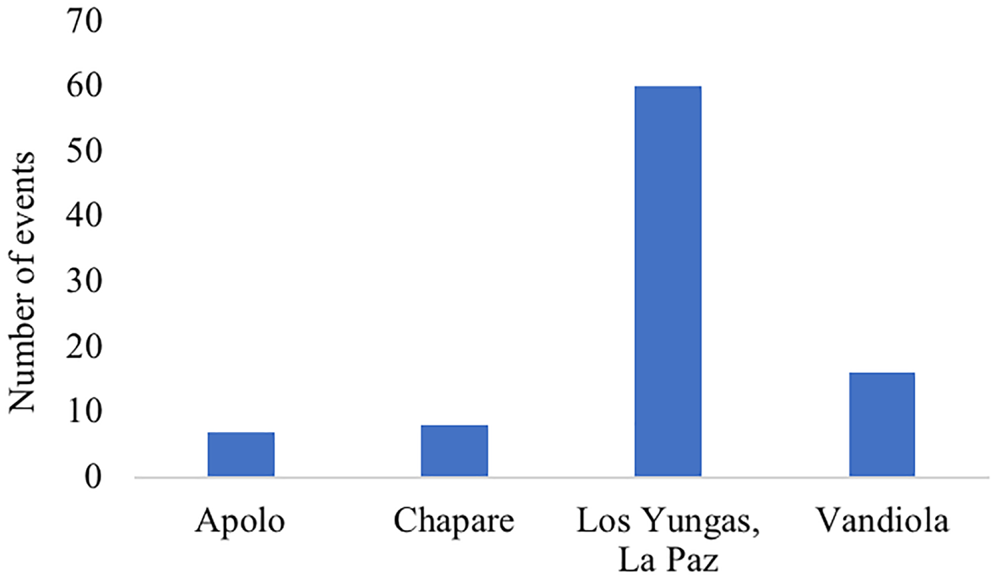

Despite its shortcomings, pundits celebrated the combination of social control and alternative development for having successfully reduced coca output and repression in Chapare. Linda Farthing and Kathryn Ledebur claim that 88 per cent of coca eradication in Bolivia between 2006 and 2013 was cooperative.Footnote 90 However, social control did not end forced eradication for traditional cocaleros in the Yungas of Vandiola.Footnote 91 As Figure 4 shows, Bolivian newspapers reported 16 forced eradication events in Vandiola between 2006 and 2016. The government claimed the eradication in Vandiola protected a nearby nature reserve but also admitted to destroying coca fields that exceeded one cato.Footnote 92 Vandiola leaders maintained that as a traditional zone, they were not subject to the cato limit. They viewed eradications as a politically motivated attack on traditional cocaleros, and they resisted eradication teams.Footnote 93 For example, in 2006, about 200 cocaleros confronted eradicators in Totora, a historical coca market, threatening them with dynamite, machetes and sticks.Footnote 94 Months later, two coca farmers were killed during a similar clash in a nearby village.Footnote 95 In June 2012, the FTC eradicated 400 catos of coca in the Vandiola community of Machu Yungas, causing 100 cocaleros to block the road to Santa Cruz and threaten to close the gas valve that supplied the city of Cochabamba.Footnote 96

Figure 4. Reports of Forced Eradication Events by Region in Bolivia, 2006–16

Source: Author's elaboration based on data compiled from national Bolivian newspapers between 2006 and 2016 archived at CEDIB.

The forced eradication in Vandiola was carried out with the support of the Six Federations, whose leaders were from non-traditional zones. Animosity between traditional Vandiola and the larger community of Chapare cocaleros began with the Cato Accord, which caused bitter disputes over the distribution of legal coca.Footnote 97 The main Vandiola organisation leading the resistance to CYCN was the Coordinadora de los Cocaleros de los Yungas de Vandiola (Coordinator of the Coca Producers of the Yungas of Vandiola), a dissident cocalero organisation within the Six Federations representing four centrales that together claimed 785 affiliates compared to 46,000 affiliates within the Six Federations.Footnote 98 Vandiola unions lacked capacity to avoid cato-isation of their fields and most Vandiola cocaleros eventually conceded to the cato limit, thereby giving up Law 1008 protections.Footnote 99

Coca Control in La Paz

Compared to Chapare, there is less research on CYCN in La Paz. This is problematic because La Paz includes the largest number of coca growers overall and the highest quantity of traditional growers, who were positioned differently under Law 1008. CYCN was less successful in La Paz precisely because traditional cocaleros in control of ADEPCOCA constrained government efforts to implement a uniform coca-control policy across the national territory. In particular, ADEPCOCA leaders claimed Law 1008 protections to resist the cato limit and social control in their areas, and also opposed state efforts to extend legal coca cultivation in non-traditional zones. However, ADEPCOCA supported government enforcement of a larger cato of 2,500 square metres for the majority of Yungas cocaleros settled in transitional zones.Footnote 100

Cocalero unions in La Paz were powerful organisations that emerged out of the 1953 Agrarian Reform and later organised ADEPCOCA to resist government efforts to regulate coca production and commercialisation in the region. While ADEPCOCA opposed Law 1008 provisions that expanded state control in the domestic coca market, its affiliates benefited from protection for traditional coca zones. Hence, in the 2005 election many Yungas traditional cocaleros favoured presidential candidate Jorge Quiroga of the party Acción Democrática Nacionalista (National Democratic Action, ADN) over Morales based on Quiroga's defence of Law 1008 against Morales’ promised reform.Footnote 101 However, after Morales took office in 2006, Yungas federation leaders met with the president to consider a government plan to reduce coca cultivation in the region. After all, at that point coca production in the Yungas far exceeded the 12,000 hectares permitted under Law 1008.Footnote 102 Rather than impose government control, thereby stoking resistance, President Morales proposed a ‘concerted voluntary reduction’ of coca in the Yungas, but his strategy had limited success.Footnote 103

In the first place, ADEPCOCA outright rejected the cato limit in traditional zones, and the government conceded.Footnote 104 Yungas leaders argued that imposing the cato limit would de facto eliminate the legal distinction between traditional and non-traditional areas established under Law 1008. Moreover, efforts to implement social control were less successful in La Paz because the Yungas federations lacked the capacity, and the will, to monitor their affiliates’ coca fields.Footnote 105 As described in section two, historically the Yungas federations did not intervene in the affiliates’ productive activities and, while ADEPCOCA required affiliates to self-report their coca production, there was no policing of their fields.Footnote 106 Indeed, the Yungas federations’ reluctance to self-police coca production during the early years of the MAS government is evidenced by the uncontrolled expansion of Yungas coca to nearly 19,000 hectares by 2008.Footnote 107

In addition, Morales faced obstacles to controlling coca production in the Yungas related to conflicts between and within the region's cocalero organisations that were in turn directly linked to divisions between traditional and non-traditional cocaleros caused by Law 1008. In contrast to Chapare, where the unity of the Six Federations facilitated negotiations and helped ensure compliance, the Yungas federations were more loosely united under COFECAY, which included 30,000 affiliates from both traditional (ex-hacienda) and non-traditional areas that diverged with respect to support for CYCN and MAS.Footnote 108 The internal division at times debilitated COFECAY leaders’ ability to identify a cohesive regional interest, and local unions in the Yungas sometimes bypassed COFECAY altogether to negotiate directly with the government. For example, in 2007, leaders from Río Antofagasta in traditional Arapata separately conceded to the cato limit for their affiliates in exchange for remuneration, even though the deal was later abandoned.Footnote 109

The presence of ADEPCOCA further exacerbated regional disunity among cocaleros in the Yungas. With only about 15,000 members, predominantly from traditional zones, ADEPCOCA had a narrower mandate than COFECAY.Footnote 110 Representing broader regional interests, COFECAY was more open to compromise with government representatives and sometimes entered into coca-reduction agreements or other negotiations that ADEPCOCA opposed.Footnote 111 ADEPCOCA at times dismissed COFECAY leaders as too loyal to MAS and considered them ‘… controlled by the government’.Footnote 112 At other times, ADEPCOCA supported involuntary eradication of non-traditional coca not authorised by COFECAY.Footnote 113 While COFECAY was generally an ally, Morales could not overcome ADEPCOCA opposition to implement the cato limit and social control in all of the Yungas of La Paz. Further, ADEPCOCA stonewalled government plans to regulate and open up the coca market with reforms such as Resolution 89 that required coca retailers to obtain a monthly quota of leaf from Chapare producers, and Resolution 427 that reduced the legal limit on individual coca sales in the Yungas (but was later annulled).Footnote 114 In other areas, ADEPCOCA protested what it considered a lack of government support for infrastructure, education, health, economic projects and especially an industrial plant for coca-based products in the Yungas.Footnote 115

Indeed, ADEPCOCA undercut government initiatives that threatened traditional cocaleros’ interests but it was also instrumental for successfully implementing government policies that benefited its social base. In August 2008, the Morales government and ADEPCOCA agreed that areas outside the traditional ex-hacienda municipalities were subject to a cato limit of 2,500 square metres, more extensive than the 1,600 metres permitted in Chapare because, ADEPCOCA argued, coca fields have a lower yield in the Yungas.Footnote 116 A month later, the government began collecting biometric information for a registry of coca growers in the Yungas and strictly delimited the traditional coca area to impose the cato limit (2,500 square metres) in outlying zones.Footnote 117 In 2014, ADEPCOCA authorised a similar registry of legal growers in Apolo, but government representatives faced resistance from protestors. ADEPCOCA denounced the demonstrations, reaffirming that the ‘legitimate traditional producers’ were in agreement with eliminating new farms.Footnote 118

The biometric registry increased forced eradication and social unrest in La Paz. In fact, the Yungas experienced the highest number of reported resistance events related to coca eradication between 2006 and 2016 (see Figure 4). Supported by ADEPCOCA, most eradication occurred outside the traditional ‘coca belt’.Footnote 119 Some of the most intense eradication took place in the municipality of La Asunta, a non-traditional coca community impacted by eradication and related social unrest as early as 2008. One MAS deputy in Congress, echoing a bygone era, proclaimed that La Asunta growers were ‘obligated by international treaty’ to eradicate.Footnote 120 In response, La Asunta growers initiated a march to La Paz in April of 2008 and threatened other forms of resistance. They argued that their coca supplied the legal market (in contrast to Chapare) and criticised the Morales government for favouring Chapare farmers who have the same legal status under Law 1008 as non-traditional cocaleros of the Yungas.Footnote 121

Predictably, ADEPCOCA did not support La Asunta growers in their struggles against forced eradication. La Asunta leaders told the press that ADEPCOCA had ‘… sold out to the government’.Footnote 122 Meanwhile, more than a thousand La Asunta growers descended on the capital city of La Paz, forming a ‘human carpet’ at the doorstep of the Ministerio de Desarrollo Rural (Ministry of Rural Development), demanding that their coca be protected and encouraging government eradication in other non-traditional zones such as Caranavi and Palos Blancos, and areas of expanding coca production in Apolo.Footnote 123 Eventually, forced eradication extended to all of these zones, thus galvanising broader resistance which sometimes turned violent. For example, Caranavi cocaleros planted crude explosives called cazabobos in their coca fields to deter eradication teams.Footnote 124 In Palos Blancos, protestors ambushed eradication teams, causing injuries and the arrest of 13 coca farmers in 2010.Footnote 125

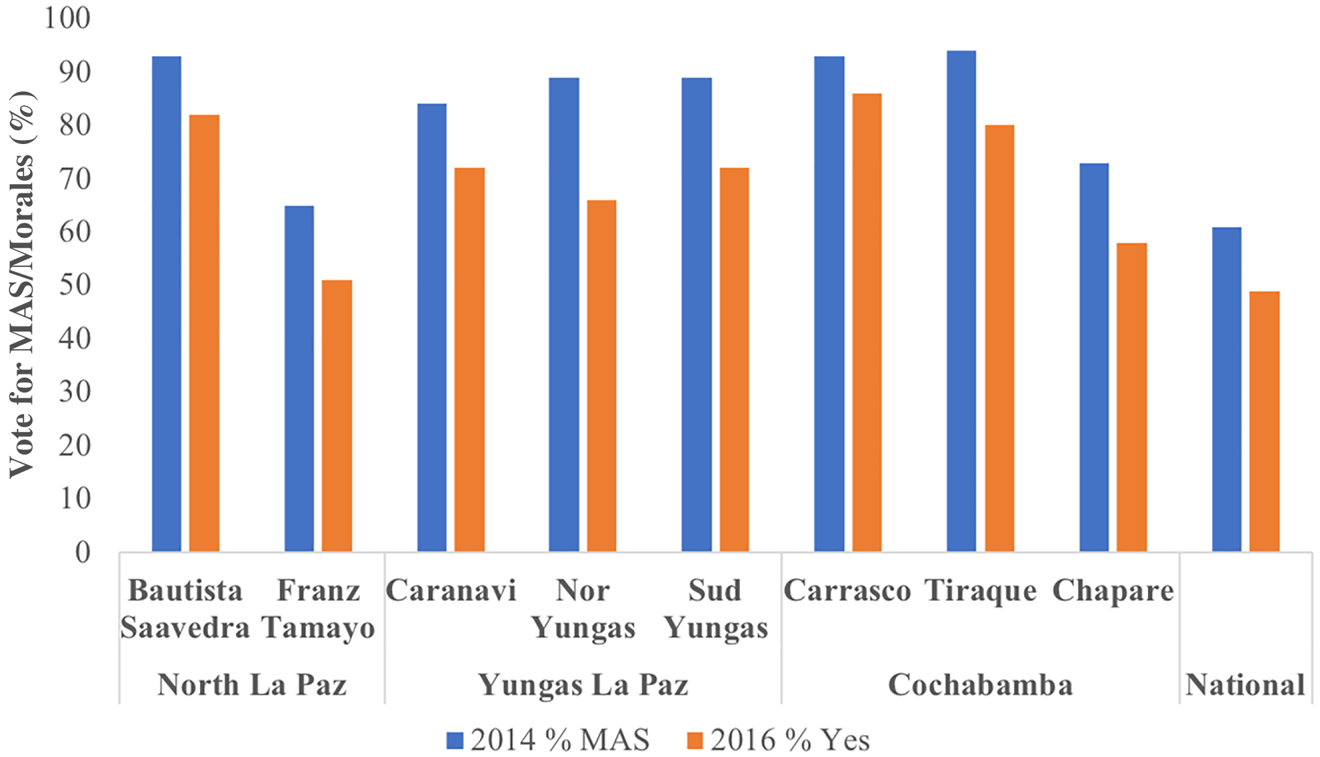

Local struggles over CYCN implementation in the Yungas contributed to eroding electoral support for the MAS, with implications for the 2019 political crisis that led to Morales’ forced resignation. As Figure 5 shows, the Yungas of La Paz supported MAS in the 2014 national elections with strong majorities, but support for Morales declined in the 2016 referendum to vote on a constitutional amendment that would allow Morales to run for a third term. Some of the decline between 2014 and 2016 reflects concern for conserving constitutional term limits and not a decline in support for MAS. However, it is notable that national support for the incumbent MAS declined by 12 points between 2014 and 2016 compared to higher losses of 23 and 17 points in the Nor and Sud Yungas, respectively.

Figure 5. Support for MAS and Morales in Coca Regions, 2014–16

Notes: 2014 data captures support for MAS in the presidential election; 2016 data captures support for Morales running for a fourth term in 2019. Chapare is skewed downward by Sacaba, an outlier municipality located near Cochabamba city.

Source: OEP, Atlas Electoral de Bolivia, Tomo IV, pp. 14, 35−8, 41−2, 376, 379−82.

In addition, in the 2015 subnational elections, several new parties contested MAS dominance in the region. For example, the centre-left party Soberanía y Libertad para Bolivia (Sovereignty and Liberty for Bolivia, SOL.bo) won the gubernatorial race for La Paz with competitive vote shares in Yungas provinces.Footnote 126 Likewise, the leftist Movimiento por la Soberanía (Movement for Sovereignty, MPS) party, formed by MAS dissidents, won the mayoral election in the Caranavi municipality of Alto Beni.Footnote 127 In the run-up to national elections planned for May 2020 (but later postponed until October), the MPS allied with the MNR to back Quiroga for president. Quiroga was vice-president during Plan Dignidad (1998–2001), and the 2005 presidential candidate who appealed to traditional cocaleros in La Paz by defending Law 1008.Footnote 128

The strongest signal of declining support for MAS among Yungas traditional cocaleros in 2015 was ADEPCOCA's registration as a political party and presentation of candidates in traditional municipalities. Indeed, ADEPCOCA leaders aspired to form a Yungas-based party, thus resembling MAS’ trajectory that emerged out of the resistance movement.Footnote 129 ADEPCOCA did not claim electoral victories in 2015. This may be because, despite conflicts, traditional cocaleros had not yet experienced significant losses linked to CYCN. ADEPCOCA had, up to that point, successfully evoked Law 1008 to oppose the cato limit in its communities, sometimes by taking direct actions to challenge the law. However, the 2017 General Law of Coca (Law 906) solidified a more visible opposition in the Yungas.

The General Law of Coca

The 2017 General Law of Coca (Law 906) exacerbated the divide between traditional and non-traditional cocalero communities with respect to CYCN while also revealing the power of cocalero organisations in national drug policy. While widely unpopular, Law 1008 was politically difficult to overturn because the contents of a new law were bitterly contested between cocalero communities. The process sparked protests and a new ADEPCOCA leadership that excluded MAS loyalists.Footnote 130 Indeed, while the traditional far-right opposition in Santa Cruz and Sucre was the main force behind Morales’ ousting in 2019, there were opposition pockets in some former MAS strongholds, including the Yungas of La Paz. ADEPCOCA organised anti-government protests that sparked violent confrontations between demonstrators and state forces and caused widespread unrest in the Yungas within months of the contentious 2019 election.Footnote 131

For traditional Yungas cocaleros represented by ADEPCOCA, the 2017 General Law of Coca that replaced Law 1008 directly threatened their privileged position among Bolivian coca growers, which was a direct consequence of divisions created under the US-imposed Law 1008.Footnote 132 Law 906 resulted from a lengthy and combative, but also robust and democratic, public discussion with direct participation of cocalero organisations that pitted traditional farmers from La Paz against the Chapare sector. The debate revolved around key issues including the expansion of legal coca and the extent of government regulation of coca production and commercialisation. Each group, represented by its regional organisation, attempted to shape the law to conform to its sectoral interests.Footnote 133 La Paz cocaleros represented by ADEPCOCA envisioned a law restoring the privileged status of traditional areas. While rejecting government regulation of their coca, ADEPCOCA members supported a strong state role outside traditional zones, including harsh criminal penalties for coca in ‘unauthorised zones’.Footnote 134

Indeed, the highest priority for traditional growers in La Paz was to ensure the new law did not permit further expansion of legal production. ADEPCOCA leaders considered CYCN a ‘pro-Chapare system’ that, among other things, increased legal production to benefit Chapare.Footnote 135 Alessandra Pellegrini Calderón describes the Yungas position on the new law: ‘Yungueños want to be those who cultivate coca, those who trade it, and those who industrialise it, those who do research on it, and … those who give licences and permits.’Footnote 136 ADEPCOCA's proposed law distinguished two zones, those that are originario (originary; a term meaning Indigenous) to include only areas of La Paz and Vandiola where coca was produced before 1953, and no originario (non-originary) to include Chapare and expansion areas of La Paz. ADEPCOCA proposed that government regulation, including social control, be limited to no originario communities.Footnote 137

In contrast, the Chapare federations’ proposed law called for a legal limit of 20,000 hectares of coca, which included 7,000 hectares gained under the Cato Accord for Chapare and 13,000 hectares of legal coca for the Yungas of La Paz and Vandiola.Footnote 138 Additionally, the Chapare law proposition recognised all cocaleros as originarios with the same legal status.Footnote 139 Importantly, the Six Federations conditioned their electoral support for MAS on the expansion of legal coca, a strategy that assured the approval of additional hectares, while also providing further evidence of the power cocalero organisations had to shape national policy.Footnote 140

The final promulgation of Law 906, enacted in March 2017, strongly conformed to the Chapare version, thereby illustrating the Six Federations’ strong political influence on the Morales government. The promulgated General Law equalised the status of all coca growers and initially granted Chapare's proposed expansion to 20,000 hectares. However, that limit was later increased to 22,000 hectares, distributing 14,300 to La Paz regions and 7,700 to Chapare. The latter was in response to protests by non-traditional Yungas growers, represented by COFECAY, who argued that the new law disproportionately favoured Chapare.Footnote 141 The expansion accounted for the number of registered growers, but it was controversial because earlier studies estimated domestic demand for coca leaf in Bolivia at 14,700 hectares, considerably less than the 22,000 hectares permitted under the new law.Footnote 142

In addition to expanding legal production, Law 906 also expanded government authority to eradicate illegal coca exceeding the limit in any authorised zone, traditional or non-traditional, and to destroy all coca in ‘unauthorised’ areas. In this way, Law 906 increased state authority to provide access to legal coca markets for more farmers, a collective good that was previously thwarted by traditional cocalero organisations. However, the new law broke the already tenuous relationship between ADEPCOCA and MAS. In May 2018, ADEPCOCA registered its executive leader, Franklin Gutiérrez, as a candidate for president in the 2019 election to challenge President Morales. Gutiérrez promised to eradicate all surplus coca in Chapare.Footnote 143 However, in August 2018, Gutiérrez was arrested after a group of ADEPCOCA affiliates ambushed coca eradicators in La Asunta, resulting in the death of a drug-enforcement officer. Several ADEPCOCA leaders were detained, and Gutiérrez was later charged with the officer's murder, although he and his supporters insisted on his innocence and maintained that he was a political prisoner.Footnote 144

Gutiérrez's imprisonment fuelled more protest in the Yungas of La Paz in the months prior to the contested 2019 election. MAS won the election by a slim margin, leading to allegations of electoral fraud and widespread social unrest resulting in Morales’ forced resignation on 11 November 2019. Two days after proclaiming herself interim president, Jeanine Áñez, an opposition leader and former senator of the rightist party Movimiento Demócrata Social (Social Democratic Movement), released Gutiérrez from prison on 14 November 2019.Footnote 145 In December 2019, as the Áñez government brutally repressed anti-government protests in Chapare, killing ten people,Footnote 146 Gutiérrez and other ADEPCOCA leaders met with President Áñez, signalling potential support for the new government in exchange for the repeal of the General Law of Coca.Footnote 147

Conclusion and Implications

Bolivia's CYCN drug-policy programme was remarkably successful at controlling coca production in certain regions and benefitting historically marginalised communities, yet its effect was not homogeneous for other regions. This study finds that the strength of local coca organisations was instrumental in shaping different policy outcomes at the local level. CYCN was successful in areas where cocalero organisations were unified and committed to reform, and less successful in areas where cocalero organisations resisted reforms that threatened the interests of coca farmers. These findings have implications for two research programmes on social movements in the MAS government and CYCN impacts on living standards in coca regions, while also contributing policy lessons for drug-producing countries.

First, the main finding that cocalero organisations influenced matters of national coca policy contradicts a prevailing view that MAS abandoned its social-movement roots after taking power.Footnote 148 Indeed, demonstrating the power of social organisations, ADEPCOCA, a small regional organisation with only 15,000 members, successfully blocked a cato limit in traditional areas of La Paz, and resisted President Morales’ ambition to overturn Law 1008 for over a decade. When, after years of consultation with cocalero organisations, Law 1008 was finally overturned, ADEPCOCA led an organised resistance against the MAS government.

Second, this article's analysis supports earlier studies that link CYCN to improved living standards for non-traditional cocaleros in Chapare.Footnote 149 However, by taking a more comparative approach that includes traditional zones, the study uncovers important negative political and social impacts. Above all, the empirical sections show how CYCN triggered a contentious zero-sum game that pitted cocaleros against cocaleros. This happened because the reforms expanded access to a small domestic market for legal coca in a context of continued international pressure to control total coca production. The resulting distributional conflict exacerbated divisions between traditional and non-traditional cocaleros created by Law 1008. In addition, CYCN increased pressure to enforce production limits in traditional zones thereby igniting social unrest.

Finally, this article's central findings contribute policy lessons for drug-producing countries. While punitive drug policies prevail internationally, the Bolivian experience shows that illicit cultivation can be controlled without repression. However, policy success was contingent on the distinctive organisational strength and political capacity of Bolivian coca farmers. In contrast to Bolivia, in Peru and Colombia local support for voluntary eradication of illicit coca is often undercut by the political marginalisation of coca farmers. For example, in 2019, Peruvian cocaleros proposed a coca-reduction plan mirroring the ‘Bolivian model’ that would limit production to one and a half hectares per affiliate with self-policing, but the Peruvian government disregarded the plan and expanded forced eradication anyway.Footnote 150 Likewise, nearly 100,000 Colombian cocaleros eagerly signed on to a 2016 voluntary coca-eradication programme that promised direct compensation and technical assistance to farmers who eradicated their fields, but the Colombian government failed to follow through with the support in some regions, contributing to a steep rise in coca cultivation in Colombia after 2016.Footnote 151

In closing, Bolivia's experimental CYCN mollified the most pernicious domestic effects of the drug war derived from punitive approaches. In a context of unrelenting international pressure to crack down, CYCN presented a promising alternative to repressive national drug policies. Nonetheless, the 2019 political crisis permitted opponents of MAS to rapidly dismantle the CYCN framework, revealing the programme's vulnerability to counter-reform. During a short term in power, President Áñez closed legal coca markets, usurped control over producer licences and used military force to subdue cocalero protests.Footnote 152 In new elections held in October 2020, MAS presidential candidate Luis Arce won with strong support, ushering in hope of a revived CYCN. However, President Arce took office amid a rapid expansion of drug trafficking in Bolivia that renewed international pressure to reduce coca cultivation.Footnote 153 Moreover, Arce's urban middle-class background contrasts with Morales’ roots in the Chapare cocalero unions, signalling a change in MAS leadership that could diminish cocalero influence in national drug policy. Hence, while President Arce campaigned on a promise to protect Bolivia's coca farmers, the future of supply-side harm reduction remains uncertain.Footnote 154

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr Huáscar Salazar Lohman, Lee Cridland and the Centro de Documentación e Información Bolivia (CEDIB) for support during fieldwork in Bolivia. An earlier version of this manuscript, entitled ‘Turning Over a New Leaf? Drug Policy as Clientelism in Plurinational Bolivia’, was presented on 19 June 2019 at the Development Studies Association Conference in Milton Keynes, UK. The current manuscript was submitted to the Journal of Latin American Studies for review on 9 October 2019.