Introduction

The medieval lex mercatoria typically refers to a body of customary law developed by and for merchants prior to the emergence of modern commercial law. Despite this general usage, the term and its significance are contested. Lex mercatoria has been variously used to refer to general principles and customary rules elaborated in the framework of international trade, without reference to a particular national system; a hybrid legal system finding sources in both national and international law; uniform rules serving the needs of international business and economic cooperation; and even ‘all law practitioners’ (Hatzimihail, Reference Hatzimihail2008, 170). Some, such as Benson (Reference Benson1992, Reference Benson1989) and Milgrom, North, and Weingast (Reference Milgrom, North and Weingast1990), see lex mercatoria as an example of private law autonomous from the state and hence a major challenge to the legal centralist view that the state is the only or main source of ‘law’. On the other hand, scholars such as Kadens (Reference Kadens2011) contend that lex mercatoria rested upon state services for foundational support, including enforcement and broader legal recognition. Both Kadens (Reference Kadens2011) and Hatzimihail (Reference Hatzimihail2008, Reference Hatzimihail2021) note that the most pointed criticisms of medieval customary law see it as a myth.

In this paper, we engage with ongoing debates over the historical and conceptual status of lex mercatoria by placing it in dialogue with the emerging institutional logic of blockchain networks. We argue that examining blockchain through the lens of the lex mercatoria reveals important parallels and divergences that clarify the essential nature of both. Blockchain networks perform several of the core functions attributed to lex mercatoria, including facilitating cross-border commercial exchange, generating norms outside formal legal systems, and enabling a degree of autonomy from state institutions. Yet they diverge in key respects: whereas lex mercatoria relied on merchant courts and human adjudication, blockchain systems attempt to resolve uncertainty ex ante through smart contract design. Although adjudication is not eliminated, it is reconfigured in blockchain networks through a variety of decentralized governance mechanisms. This comparison allows us to view blockchain as a form of autonomous legal ordering, echoing lex mercatoria in function while innovating in form.

A central comparative insight is that both lex mercatoria and blockchain systems confront the same foundational problem: how to resolve disputes when information encoded in customary practice or digital ledgers proves insufficient. Lex mercatoria addressed such gaps through external input from guild-based courts, judges, and arbitrators. These institutions interpreted norms and provided the physical security necessary to enforce them. Blockchain networks face analogous moments when code cannot fully specify outcomes, prompting reliance on decentralized governance mechanisms such as DAOs, protocol ‘forks’, or off-chain arbitration. These similarities reveal that autonomous legal orders cannot dispense with ‘law’, yet the systems diverge in the institutional foundations that support them: lex mercatoria was embedded in communal organizations capable of coercive enforcement, whereas blockchain governance rests on cryptographic security and digital consensus. Recognizing both these parallels and the limits of this analogy situates blockchain within a broader lineage of hybrid, polycentric legal orders while challenging simplistic narratives of either system as wholly ‘stateless’.

We anchor this comparison in specific institutional mechanisms. We show, first, how lex mercatoria functioned through merchant-led adjudication (e.g., Italian consular courts and Hanseatic League practices); second, how blockchain delivers concrete services such as decentralized storage, compute, and connectivity that rely on smart contracts for enforcement; and third, how each system reduced particular categories of transaction costs in practice. By grounding the comparison in specific cases, we clarify how both lex mercatoria and blockchain represent autonomous but polycentric legal orders that expand our understanding of institutional economics.

Our analysis sees blockchain systems not as a substitute for all forms of law, but rather as a specialized subset of governance where ambiguity is precluded through code. Blockchains enforce formalized, unambiguous rules ex ante, reducing or even eliminating certain types of disputes. In this sense, blockchains exemplify autonomous commercial governance, where rule execution is dispute resolution. To the extent that blockchain governance replicates or even enhances functions traditionally associated with stateless law, it belongs in the broader conversation about decentralized, non-state legal systems.

Fundamentally, both lex mercatoria and blockchain offer innovation in response to perceived gaps in state legal institutions by relying on voluntary arrangements embedded within nested rule systems, a structure characteristic of many forms of private ordering such as arbitration (Stringham, Reference Stringham2015) and federalism (V. Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1994). Both are polycentric systems operating across multiple levels of governance, with distinct but overlapping sources of legal authority. These ‘levels’ refer to the layered institutional environments in which each system functions: in the medieval world, merchant courts operated within fairs, guilds, and towns while interacting with national courts and later common-law systems. In blockchain networks, governance spans on-chain mechanisms, such as DAOs, member-driven groups that make collective decisions under blockchain-based rules. Blockchain governance also comprises arbitration layers that interface with off-chain institutions, including state regulators and formal arbitration bodies (Rozas et al., Reference Rozas, Tenorio-Fornés, Díaz-Molina and Hassan2021; Bodon et al., Reference Bodon, Bustamante, Gomez, Krishnamurthy, Madison, Murtazashvili, Murtazashvili, Mylovanov and Weiss2022; Murtazashvili et al., Reference Murtazashvili, Murtazashvili, Weiss and Madison2022). In both cases, multiple layers coexist with some degree of autonomy, and this contestation in the provision of law exemplifies the core logic of polycentric governance (Rayamajhee and Paniagua, Reference Rayamajhee and Paniagua2021; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2005).

We trace these polycentric features in demonstrating that both systems aim to reduce the need for formal adjudication within defined transactional domains, both by fostering shared rules and practices ex ante and by adjudicating disputes ex post. At the ex ante layer, blockchains function as self-executing ledgers, where smart contracts formalize commercial customs and automate enforcement. Similarly, merchant courts historically recorded judgements to serve informational and coordinating functions among traders. This analogy operates on two levels. Blockchains codify rules to prevent disputes, much like the customary norms of lex mercatoria.

At the ex post layer, while traditional systems escalate unresolved disputes to state courts, blockchain systems often resolve them internally through mechanisms like DAOs, but when on-chain governance fails, they appeal to external courts much in the way that merchants did under the historical lex mercatoria. The frequent outsourcing of disputes to off-chain mechanisms mirrors the polycentric character of the medieval lex mercatoria, as described by Kadens (Reference Kadens2011), where autonomous norms coexisted with and relied upon state-backed enforcement when necessary. Blockchain governance similarly blends internal and external adjudication, as emphasized by scholars such as Werbach (Reference Werbach2018), Frolov (Reference Frolov2021), Alston et al. (Reference Alston, Law, Murtazashvili and Weiss2022), and Grimmelmann and Windawi (Reference Grimmelmann and Windawi2023). This literature emphasizes that both on-chain and off-chain forms of governance are essential to understanding how blockchain systems function.

Our paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 situates the argument within debates about the origins of law, contrasting state-centric accounts with perspectives emphasizing private ordering. Section 3 examines lex mercatoria as a governance system, focusing on economic and legal-historical debates about its character and its relationship to public authority. Section 4 outlines the core features of blockchain governance, including smart contracts, DAOs, and related mechanisms. Section 5 offers a comparative institutional analysis of the two systems, highlighting how each reduces transaction costs, manages adjudication, and interacts with state law. Section 6 concludes by considering the broader implications for polycentric legal orders and how historical experience with medieval commercial practice may inform the evolution of blockchain governance.

What is law and where does it come from?

There is widespread agreement that legal institutions shape prospects for prosperity. Still up for debate is whether that institutional order must necessarily come from the state.

A rich literature offers a strong case for what could be called a state-centric view of legal order. Legal institutionalists and the so-called ‘old institutionalists’ argue that state-backed laws are necessary for capitalism (Deakin et al., Reference Deakin, Gindis, Hodgson, Huang and Pistor2017; Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2015, Reference Hodgson1998; Bromley, Reference Bromley2006; Commons, Reference Commons1924). The ‘new institutionalists’ emphasize legal rights as well (North, Reference North1991), though ‘economic’ or de facto rights and informal institutions are also considered important (Barzel, Reference Barzel2002, Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990). Relatedly, a substantial literature highlights the positive role of state capacity in shaping prospects for economic prosperity, including the state’s capacity to establish a legal framework for capitalism (Piano, Reference Piano2019). Even constitutional political economy traditions emphasize the necessity of state-provided order (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan1975; Brennan and Buchanan, Reference Brennan and Buchanan1985).

Viewed in its totality, that perspective sees law as essential to prosperity and the state as the primary, or even exclusive, source of it. A contrasting view highlights the scope for order when the state is unwilling or unable to enforce rules, as seen in studies of anarchy and communal self-governance. Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) work on natural resource governance and Ellickson’s (Reference Ellickson1991) study of cattle ranchers both show that communities can rely on social norms rather than formal legal rules to manage disputes.

This literature raises a central puzzle: can such norm-based systems scale to interactions among strangers? Kandori’s (Reference Kandori1992) model of gossip demonstrates how shared information can sustain cooperation in large, anonymous groups, offering a theoretical basis for coordination beyond close-knit communities. Choi and Storr (Reference Choi and Storr2022) emphasize that modern commerce routinely involves heterogeneous actors transacting across substantial distances yet still achieves reliable exchange through institutional intermediaries and reputational systems. For example, consider how many people today use Amazon. A notable aspect of this modern marketplace is that buyers can make purchases without knowing who the seller is. Instead, they rely on the system of intermediaries that operates under the name ‘Amazon’, which is to say that they rely on Amazon’s reputation as an institutionalized form of trust.

Legal institutions, whether state sponsored or spontaneously arising, may complement or substitute for reputational systems. A wide range of ‘integrationist’ perspectives emphasizes complementarity: Posner (Reference Posner2009) argues that legal rules provide formal mechanisms for enforcing norms and resolving disputes, while social norms exert informal influence through approval, disapproval, and peer pressure; likewise, the literature on relational contracting shows how informal incentives depend on default outcomes implied by formal rules and contractual obligations (Baker, Gibbons, and Murphy, Reference Baker, Gibbons and Murphy1994). Vincent Ostrom’s theory of federalism similarly highlights how self-governance and spontaneous order can coexist within broader legal frameworks. Rather than viewing spontaneous and governmental order as opposites, this work shows that formal institutions can structure, reinforce, or channel decentralized processes of innovation.

Even in the absence of formal legal enforcement mechanisms, should the rules that govern commerce be thought of as ‘law’? Weber’s classic insight in Economy and Society (Reference Weber1978 [1922]) was that commercialization drives the rationalization of rules, even without direct state power. This broader conception of law situates legal order within social processes rather than exclusively within governmental institutions. Hadfield (Reference Hadfield2016) and Hadfield and Weingast (Reference Hadfield and Weingast2012) develop this idea by arguing that lawful societies are characterized not merely by state-backed rules but by institutions that supply normative classification schemes, such as those that identify certain actions as ‘wrong’ or ‘unlawful’, and by actors who voluntarily refrain from such actions. Their definition does not presume a benevolent third-party enforcer but instead emphasizes law’s role in providing credible commitments, resolving disputes, and facilitating cooperation among strangers, functions that can be supplied by either government or society at large. Commons (Reference Commons1924), likewise, understood law as an evolving construct shaped through the decisions of judges and other adjudicators, reflecting institutional development rather than simply state command. Taken together, these perspectives challenge the view that law is solely a governmental domain and highlight that what makes rules ‘law’ is their capacity to coordinate behaviour and structure economic activity, regardless of whether they originate inside or outside the state.

In what follows, we argue that lex mercatoria and blockchain governance offer insight into the debates above. In general, both lex mercatoria and blockchain validate the view that private ordering is a significant source of institutional innovation. And yet each of these institutions demonstrates that the idea of a ‘stateless’ order is inaccurate insofar as each of the institutions under consideration is part of a multilayered institutional system.

Lex mercatoria as a governance system

What was lex mercatoria?

Lex mercatoria is generally understood as customary law for merchants that operated primarily in medieval times. Though it is sometimes referred to as ‘the law merchant’, that term suggests it is an individual, or someone providing law privately for a fee. Rather, it was a body of customary law, and while there were judges present to interpret this law, its essential feature is that it is considered by some to be a coherent body of law.

The lex mercatoria narrative centres on the merchants and associations that sustained long-distance, cross-border trade across medieval Europe. In Northern Europe and the Baltics, merchants from German-speaking towns formed the Hanseatic League (13th–17th centuries) to facilitate trade in timber, grains, furs, fish, and textiles. Italian merchants from Genoa, Venice, and Florence engaged in commerce involving spices, silk, wool, olive oil, and a range of financial services, including maritime finance and commercial partnerships. English, French, and Dutch traders dealt in textiles, wine, sugar, tobacco, tea, and emerging insurance contracts. Market and fair merchants across England and Continental Europe exchanged cloth, leather, spices, tools, jewelry, and livestock at regional and international fairs such as England’s major trade fairs and the Champagne Fairs in France (Greif Reference Greif2006a, Reference Greif2006b; North and Thomas, Reference North and Thomas1973).

This complex ecosystem inevitably generated disagreements over payment defaults, delivery disputes, and ambiguity of contract provisions, especially as there was no uniform international commercial law and as traders were often from different jurisdictions. These were customary, to begin with, but they were eventually codified, either through common law or through decrees in code-based systems of law.

Merchant courts operated locally, primarily in the emergent markets. In modern terms, merchant courts resembled private arbitrators applying widely accepted commercial practices, rather than formal law, to resolve disputes, much as modern private arbitrators are not necessarily bound simply to follow formal law.

Despite the emphasis on voluntariness, some aspects of merchant law were not entirely voluntary. This is illustrated by the piepowder courts. These were temporary tribunals that were known to administer swift justice and adjudication of disputes among merchants and market-goers. These courts were presided over by the mayor and operated under a lord’s authority, with broad jurisdiction over merchant contract disputes and other violations, including theft and acts of violence. Sir William Blackstone, in Commentaries on the Laws of England (1768), described them as expeditious courts of justice, supplemental to the common law of England.

While piepowder courts are often invoked in discussions of lex mercatoria, mayors or borough officials presided over them. They blended local governmental oversight with merchant dispute resolution and therefore functioned as hybrid tribunals rather than autonomous commercial courts. Clearer illustrations of merchant-driven adjudication come from the Italian consular courts where senior merchants elected by their peers judged disputes according to commercial custom. Another example is the Hanseatic League, which developed merchant courts and guild-based enforcement mechanisms recognized across northern Europe.

The rationale for developing and applying customary law was that the merchants themselves wanted to apply laws they found best for themselves. Issues might include broken contracts, non-payment, or delayed shipments. Merchant courts also handled payment and credit issues, including enforcing early forms of credit. No established commercial law was already in place. Common law courts did not have a specialized law for merchants, as much of the existing common law of property was developed to promote more efficient agricultural production. Insurance markets were just beginning to emerge during the time in which lex mercatoria operated. As North and Thomas (Reference North and Thomas1973) emphasize in their economic history of Western Europe, each of these developments constituted a foundation for the Industrial Revolution, but development of the rules occurred in piecemeal fashion and often originated in emergent commercial practice.

An important question is the extent to which lex mercatoria was explicit versus customary. Initially, the ‘law’ was largely customary, arising from the practices merchants regarded as appropriate to their occupations. Over time, however, elements of these practices became formalized. This occurred through merchant court records, statutory interventions such as the Statute of Staple (1353), and eventual incorporation into common law. Holdsworth (Reference Holdsworth1907) accordingly treated the ‘Law Merchant’ as a body of formal rules established by towns and codified through measures like the Statute of Staple, suggesting that much of what later came to be called lex mercatoria was anchored in public authority rather than an autonomous merchant code. Kadens (Reference Kadens2011, 2015) similarly argues that predictability in commercial adjudication was uneven, varying across regions and periods, and that the idea of a coherent, stateless customary law is overstated. Yet the routine submission of disputes to merchant courts indicates that, despite this unevenness, merchants found the outcomes sufficiently reliable to sustain cross-border exchange. By the 17th and 18th centuries, English courts began to develop a more explicit common law of commerce, integrating these practices and completing the transition from a patchwork of local norms to a more formal commercial legal order.

Economists and lex mercatoria

Economists have leaned towards a ‘purist’ view of lex mercatoria, seeing it as a spontaneous, voluntary, and private source of law. Benson (Reference Benson1989) and Milgrom, North and Weingast (Reference Milgrom, North and Weingast1990) each developed a theory of customary commercial law. The perspectives are different, though the implications are similar.

Benson (Reference Benson1989) sees lex mercatoria as a body of customs that the merchants themselves believed were appropriate to their occupations and that the body of law exemplifies a Hayekian spontaneous order. A spontaneous order is one in which the order arises from the intentional behaviour of individuals, without conscious design from the government (Hayek, Reference Hayek1948). Benson contends that merchants, through their repeated interactions and reliance on predictable norms, established a decentralized legal system that adapted to changing circumstances.

Benson draws a line from the law merchant to modern international commercial law, emphasizing the role of private ordering and dispute resolution mechanisms, such as arbitration, in maintaining order and resolving conflicts within the commercial community. Benson argues for the effectiveness of the law merchant as a decentralized legal system evolving through the interactions of merchants, thereby fostering predictability and adaptability in international trade. This viewpoint underscores the role of informal norms and practices alongside formal legal institutions, a key aspect of new institutional economics’ approach to analysing economic phenomena.

Milgrom, North, and Weingast (Reference Milgrom, North and Weingast1990) emphasize that a key feature of merchant law was voluntary cooperation: merchants submitted disputes to judges whose decisions became binding. In their model, lex mercatoria judges (who were often themselves merchants) served as repositories of information, enabling long-distance trade in the absence of centralized legal authority. To manage the risks of cross-jurisdictional exchange, merchants developed informal governance mechanisms such as merchant courts, guilds, and other reputation-based systems (Greif, Reference Greif2002). These institutions facilitated trade by enforcing agreements, resolving conflicts, and sustaining trust. Traders had incentives to petition judges, and judges had incentives to reveal traders’ ‘true’ histories, making lex mercatoria effectively a form of institutionalized gossip in which past judgements circulated as shared information.

Legal scholars and lex mercatoria

Legal scholars (as well as some economic historians besides the ones mentioned above) have long challenged the idea that medieval customary law existed as a coherent, stateless order. Baker (Reference Baker1979) concludes that what was called the lex mercatoria was neither an import from a common law of nations nor the product of specialized mercantile courts. Instead, it was a refinement of common law itself, crystallized by Renaissance courts from the customs and common sense of juries. Volckart and Mangels (Reference Volckart and Mangels1999) likewise deny the existence of a uniform medieval lex mercatoria but emphasize that urban autonomy and local law, not transnational codes, structured commercial interaction. Guilds offered merchants physical security, while courts varied by region, tied closely to local political authority and coercive power. Whereas Baker sees commercial law as an indigenous development within the English common law, Volckart and Mangels (Reference Volckart and Mangels1999) highlight the fragmented, politically contingent character of mercantile regulation across medieval Europe. Sachs (Reference Sachs2006) reinforces this revisionist view by showing that merchants in medieval England operated largely under local public authority and that commercial customs varied significantly across fairs and towns rather than forming a coherent, transnational legal order. Sachs’ account underscores that the standard story of an autonomous medieval law merchant is as much an ideological construct as a historical description.

Building on these earlier legal-historical critiques, Emily Kadens provides a forceful challenge to the view that custom was an autonomous source of commercial law. According to Kadens (Reference Kadens2015a, Reference Kadens2015b, Reference Kadens2011), there was already law in place by the time lex mercatoria supposedly emerged. Customary law, while influential in shaping commercial practices, is often incomplete, inconsistent, and unable to address complex legal issues arising in modern international trade. Kadens highlights the importance of state law and international treaties in providing a legal framework for regulating cross-border transactions and protecting the interests of parties with unequal bargaining power. Relying solely on customary law risks leaving gaps in legal protection and undermines the rule of law in international commerce.

Kadens’s critique of the very concept of an autonomous body of customary law in the medieval period leads to an alternative view that accords a more significant role for formal legal frameworks. This legalistic perspective recognizes that customary law left significant gaps in protection of legal rights. Kadens’ argument is that establishing clear rules and regulations to govern economic interactions and ensure stability and fairness is critical to modern commerce – an idea that resonates with the core ideas of legal institutionalists and the old institutional economics.

There are even more critical views of lex mercatoria studies. Kadens has variously considered whether lex mercatoria is a ‘myth’ and has gone so far as to suggest the ‘tyranny’ of the concept of medieval customary law. These are significant criticisms that require us to consider more carefully the economic perspective, which tends to downplay the backstop role provided by governments. The piepowder courts are a good example to return to; these were basically expedient courts, not private law. Section 5 will return to these issues. First, however, we introduce blockchain governance and its corresponding debates, some of which are analogous to the tremendous contestation over the nature and significance of lex mercatoria.

Blockchains as a governance system

From blockchain to blockchain governance

Blockchain, like lex mercatoria, is the subject of significant debate. As far as a definition, the key feature of a blockchain is that it is a distributed append-only digital ledger and a novel institutional and organizational technology (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, De Filippi and Potts2018). This append-only feature makes blockchains more challenging to manipulate and is what creates confidence in information and processes on blockchains (De Filippi et al., Reference De Filippi, Mannan and Reijers2020, De Filippi and Wright, Reference De Filippi and Wright2018). Participating in a blockchain-based organization and transaction requires ownership of encrypted tokens, or digital assets, that exist, by design, only on the blockchain itself. Tokens may offer value in themselves, as in the case of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, or may refer to or signify ‘real’ assets that exist off-chain. The blockchain itself is simultaneously a ledger and a platform for transactions in tokens. To maintain parallel structure with our discussion of lex mercatoria, this section highlights only the most essential features of blockchain governance that set up the comparison in Section 5.

Conceptual contestation arises once we consider that there is not a single ‘blockchain’. There are public or permissionless blockchains (where token ownership is open to essentially anyone), private or permissioned ones that operate much more like conventional firms, and hybrid systems. Applications are in the public, private, and voluntary sectors.

Regardless, what is inescapable in discussing blockchain is the role of smart contracts and DAOs as novel contractual mechanisms. The technical definition of a smart contract is a self-executing computer program stored on a blockchain that automates enforcement of contracts when predefined contributions by blockchain participants are met, eliminating the need for intermediaries by enforcing rules transparently and securely. Beyond that technical definition, the significance of smart contracts is that they connect, and are a sort of glue, between the real and digital realms (Lehr, Reference Lehr2021, Reference Lehr2022).

A decentralized autonomous organization is governed by smart contracts on blockchains where decisions regarding transactions are made collectively through voting, rather than by a central authority. Both internal DAO governance decision-making (such as the decision to accept further investment in a DAO and thus enable participation by additional token holders in DAO decisions) and transactions between a DAO and other token holders (such as smart contracts that document supply chain transactions) are undertaken electronically, on-chain. DAOs operate transparently, with rules and processes encoded in their smart contracts. They can be thought of as a reimagining of the corporate form in the digital realm (Davidson Reference Davidson and G.forthcoming, Madison and Murtazashvili Reference Madison, Murtazashvili and Gindisforthcoming).

While there is no single blockchain, several architectural elements together constitute ‘blockchain governance’. The automation layer includes smart contracts and DAOs that encode and enforce rules transparently and reduce reliance on trusted intermediaries. An incentive and security layer encourages honest participation through voting rights, token-based rules, and identity-verification systems that deter manipulation. The trust and adaptability layer consists of consensus mechanisms (such as Proof of Work or Proof of Stake) that ensure agreement on the blockchain’s state and protect against attacks. A legitimacy layer verifies unique, sometimes anonymous identities, while a broader adaptability layer encompasses governance structures and human oversight. This includes protocols for updating smart contracts, resolving unforeseen disputes, and interfacing with external information through oracles that link blockchain code to real-world data on goods and services.

The novelty of blockchain

At its technical core, blockchain operates as a decentralized, cryptographically secure ledger in which transactional data is distributed across multiple nodes rather than managed by a central authority, ensuring tamper resistance and offering an alternative to centralized control. This structure prompts new questions about how governance and trust can be organized outside traditional state frameworks. Much like medieval customary law, blockchain networks can be understood as polycentric systems with overlapping jurisdictions. Yet blockchain also introduces features that distinguish it from historical forms of private law. Although often portrayed as an alternative to government, institutionalists emphasize that blockchain itself requires governance; as Alston et al. (Reference Alston, Law, Murtazashvili and Weiss2022) note, it even resembles a hierarchical organization in important respects. Blockchain governance operates on two levels: an internal layer involving modifications to the network’s structure by programmers and developers, and an external layer concerning the human specification of the blockchain’s ‘constitutional’ design, all of which are ultimately represented in code (Alston, Reference Alston2020).

Blockchain governance also relies heavily on human-controlled intermediaries – developers, miners, and oracles – who shape how networks function. These actors introduce points of influence and potential vulnerability within the architecture. They are confronted by social dilemmas much in the same way as any large organization might be, with human-influenced splits or forks as routine ways that disputes are resolved in blockchain networks (Berg and Berg, Reference Berg and Berg2020).

The external perspective embraces the idea that blockchain networks coexist with conventional institutions, including governments and legal systems. Additional institutions operate in the space between internal and external governance. Oracles, for example, serve as necessary intermediaries between blockchain data and the outside world, providing real-world information necessary for smart contract execution. But these oracles also raise issues that intertwine or entangle blockchains with conventional structures of governance. Reliance on oracles introduces new risks, as inaccurate or manipulated data can undermine transaction integrity, complicating blockchains’ capacity to serve as self-regulating systems (Allen, Lane and Poblet, Reference Allen, Lane and Poblet2020). State-supplied law is useful to maintain order and create trust in blockchain, especially in cases involving disputes, fraud, or complex contract breaches.

Ultimately, the relationship between blockchain networks and law is analogous to that between law and medieval customary law, which relied on overlapping layers of governance from guilds and city-states. Though blockchain lacks inherent alignment with traditional state-backed legal frameworks, creating uncertainties in enforcement and regulatory recognition, it also benefits from a supportive legal apparatus. This aligns with legal scholars contending that blockchain networks benefit from formal legal support to ensure compliance and resolve conflicts (Werbach, Reference Werbach2018; Grimmelmann and Windawi, Reference Grimmelmann and Windawi2023). While smart contracts can enable automated, self-enforcing transactions within the blockchain, they ultimately depend on traditional legal systems for enforcement in real-world scenarios. Judicial recognition and enforceability of blockchain transactions are thus critical to the system’s functionality, especially when participants seek external adjudication of disputes (Werbach, Reference Werbach2018).

For example, courts in the United States have applied contract law to disputes over failed token sales and securities law in cases such as the US Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) litigation against Ripple Labs discussed below (Ripple sold its cryptocurrency without registering it as a security, leading to the SEC’s involvement). Property law and consumer protection statutes are also invoked when questions arise over ownership of digital assets or fraud in initial coin offerings. Consider a common scenario: a smart contract automatically transfers tokens for a service, but the off-chain service (e.g., delivery of cloud storage through Filecoin) fails to materialize. Here, blockchain code cannot compel real-world performance. Parties may seek remedies under traditional contract or consumer protection law, and courts provide enforceability or restitution. In this way, ordinary doctrines of contract, property, and securities law continue to shape blockchain’s viability, complementing the automated enforcement that occurs on-chain.

The discussion above highlights key similarities between lex mercatoria and blockchain: both possess some autonomy and generate distinct forms of institutional innovation. Although blockchain enables autonomous contracting, it also relies on systems of on-chain and off-chain adjudication where human decision-making remains significant. It is therefore neither a fully decentralized substitute for modern commercial law nor a completely autonomous source of law, but rather a law-like system with autonomous features that performs functions akin to the medieval law merchant. In this sense, blockchain can be viewed as a technologically driven descendant of merchant law. We expand upon this comparative analysis in the following section.

Comparing and contrasting lex mercatoria and blockchain networks

Transaction costs, private ordering, and interoperability

A useful way to understand the similarities between lex mercatoria and blockchain governance is through standard institutionalist framework of transaction costs, which include the costs of identifying trading partners, negotiating agreements, enforcing contracts (Coase, Reference Coase1937), the broader search, information, bargaining, decision, policing, and enforcement costs highlighted by Williamson (Reference Williamson1996), and the costs of shaping and sustaining institutions more generally (North, Reference North1990). Traditionally, hierarchical organizations such as firms or governments were viewed as solutions to negotiation and enforcement costs, as well as a means to record information and measure economic activity (Allen, Reference Allen2011).

From this standpoint, the significance of lex mercatoria lies in its capacity to economize on transaction costs by providing a private, decentralized solution to policing and enforcement. Merchants selected their own judges, whom they trusted to resolve disputes impartially, and the resulting decisions were self-enforcing. This adjudicatory structure reduced negotiation and enforcement costs without requiring a centralized authority, illustrating how private ordering can perform many of the institutional functions typically associated with hierarchical governance.

Smart contracts and DAOs reimagine contracting, relying not on firm-based (or state-based) hierarchy but on code to develop enforceable contracts and agreements. It broadens the scope of contracting to enable reliance not on third parties but on individuals who can agree. In a more technical sense, blockchain moves from an environment in which the uncertainty and boundedness of language gives rise to contracting costs (solved by the invention of the firm) to a world of incomplete contracting (solved by specifying transactions in code). In each case, what is significant is that the solutions are not conventional hierarchies but are in some ways private and autonomous solutions to transaction costs.

Beyond cryptocurrency, blockchain networks already deliver specific goods and services. For instance, the Livepeer protocol supplies decentralized video transcoding services, rewarding participants through smart contracts verified by proof of delivery.Footnote 1 Filecoin offers decentralized data storage, where contracts specify storage commitments and automated payments.Footnote 2 The Helium network provides wireless hotspot coverage through blockchain-mediated incentives.Footnote 3 Each example demonstrates blockchain’s potential as an institutional technology that organizes the provision of services through rules enforced on-chain. These services illustrate concretely how blockchain governance reduces enforcement and policing costs, much as merchant law once facilitated long-distance trade in goods such as wool, wine, and spices.

What emerges with blockchain is a different kind of private solution to contracting problems than the Coasean firm. In Coase’s framework, firms internalize transactions through hierarchy, but the enforcement of firm contracts ultimately depends on state law. By contrast, blockchain enables private ordering through code: agreements are enforced automatically on-chain without recourse to courts unless something goes wrong. In this sense, blockchain reduces reliance on corporate hierarchy and state-backed enforcement. Although blockchains are often described as public ledgers, they differ from traditional public ledgers maintained by states or firms because they are decentralized and secured collectively by network participants rather than a central authority. For example, a decentralized exchange (DEX) like Uniswap executes token swaps entirely through code, without a corporate structure or state intermediary, whereas a traditional financial firm such as a bank relies on internal hierarchy and state-enforced contracts to manage similar transactions.

The above clarifies which kinds of costs are reduced by each of these institutions. Medieval customary law reduced transaction costs by creating forums where merchants could rapidly resolve disputes across jurisdictions, lowering search and enforcement costs. Judges’ reputations provided information about traders’ reliability, reducing information asymmetries. In blockchain systems, coding contract contingencies ex ante reduces bargaining and policing costs by limiting scope for opportunism. Consensus mechanisms lower search costs for verifying counterparties, while automated execution reduces enforcement costs. Both systems thus economize on Williamson’s categories of transaction costs (search, bargaining, and policing) but through different institutional logics.

In the blockchain context, interoperability refers to the ability of distinct digital systems or platforms to exchange data, assets, and services through a shared technical framework. Understood through a transaction-cost lens, interoperability addresses the costs of coordination across heterogeneous systems. Lex mercatoria emerged in response to a similar challenge: fragmented local customs and jurisdictional boundaries often impeded consistent commercial practices, and medieval customary law functioned as a protocol that facilitated cross-regional coordination. Blockchain aspires to play a comparable role in digital environments, offering structured mechanisms for communication and information exchange across decentralized networks. Yet achieving full interoperability remains difficult. This challenge is particularly visible in attempts to record real property on blockchains, where critics emphasize that meaningful interoperability is still far off (Arruñada, Reference Arruñada2020). Even so, blockchain ecosystems show promise in enabling platforms to interact with reduced friction. As Davidson et al., (Reference Davidson, De Filippi and Potts2018) note, interoperability can lower transaction costs and improve information sharing in polycentric systems with overlapping governance structures. Blockchain thus provides a common language for coordination through its flexible ledger-linking protocols.

Legal scholars have long recognized the importance of such coordination problems. Some argue that blockchain, unlike lex mercatoria, constitutes a foundational institutional innovation capable of rivaling firms and states, a perspective reminiscent of Joel Reidenberg’s (Reference Reidenberg1998) characterization of computer code as a modern lex informatica. Interoperability also helps illuminate a persistent question about lex mercatoria: if medieval customary law was efficient, why did formal commercial law supplant it? The legal scholar Lisa Bernstein (Reference Bernstein1996) argues that modern commercial law displaced, rather than merely incorporated, trade custom because customary law lacked the clarity, consistency, and mutual discoverability needed for a modern economy. More broadly, customary law cannot standardize relations among trading partners the way governments can via formal legal regimes. In this regard, blockchain’s potential to generate standardized, interoperable frameworks may offer advantages over customary systems such as lex mercatoria.

This contrast also highlights why blockchain may play a more foundational role in the modern economy than historical customary commercial law. Unlike medieval systems, blockchain networks can interoperate and support exchange among strangers at unprecedented scale. They also perform functions that states cannot fully replicate, and they are difficult for governments to eliminate or fully replace with centralized alternatives. At the same time, governments can adopt blockchain technologies to improve record-keeping and administrative processes. In this sense, blockchain could become an enduring layer of governance rather than a transitional system eventually absorbed by the state.

Institutional layering and polycentricity

We can take the comparative analysis a step beyond transaction costs by considering institutional layering and polycentricity. Reducing transaction costs is one way to consider blockchains. But the way that they did so was not because they were fully autonomous but because they were nested in higher levels of government.

Williamson (Reference Williamson2000) considers institutions at several levels: social embeddedness (informal institutions include tradition, culture, and religion that evolve slowly), institutional environment (formal rules, including political and legal institutions, including constitutions, laws, and property rights), governance (the structures that define how firms, markets, and organizations operate in the institutional environment), and operational resource allocation and employment rules. Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) referred to these operational and employment rules as ‘working rules’ and organized them via a three-layer framework of constitutional rules, collective choice rules, and working or operational rules, with recognition that collective choice rules can come from government or from society, as in self-governing arrangements.

At least some of the literature on lex mercatoria and blockchain suggests that changes in the governance layer may emerge in somewhat autonomous fashion. Still, the autonomy exists in what is a polycentric system. Lex mercatoria may have existed as custom, but it derived its significance in large measure because of state-appointed judges (including when merchants were appointed by governments). Blockchain governance reduces the need for adjudication in certain realms where contracts can be hard-wired into code.

We also see a virtue of describing each as examples of polycentric institutions, rather than stateless institutions. Lex mercatoria was operating within some system of government, whether a city or nation-state; governments at multiple levels issued and enforced legal rules that determined, to a significant degree, the identity and character of the subjects of trade in the first place. Production, in other words, was often a matter of state or guild permission. It was not pure anarchy, as sometimes is suggested in the economics of anarchy. In such situations, what is necessary is to see the ways in which law is nested within higher levels of government.

The great medieval fairs had important roles for mayors, for example, in providing benedictions to the fairs and to the judges. Still, the judges were selected by merchants and used the laws that the merchants thought were appropriate, at least to some extent. Similarly, blockchain depends on a favourable institutional environment that recognizes the legitimacy and enforceability of a smart contract or the convertibility of a cryptocurrency token into ‘real-world’ currency.

Just as merchant law had to engage with the formal legal system so too does blockchain. Within a few years after cryptocurrency became popular, several US states banned Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies (Hendrickson and Luther, Reference Hendrickson and Luther2017). Though the bans generally gave way to acceptance, the legal wrangling remains. Returning to a dispute introduced earlier, the SEC sued Ripple Labs over whether offering crypto tokens for sale constitutes the offering of an unregistered security. The question is what is defined as a ‘security’ and hence what authority does the SEC have to regulate blockchain transactions. The relevant contention is that the decision of courts will either allow the SEC that regulatory power or deny it, which demonstrates how blockchain is very much contingent on regulation. In May 2025, the SEC settled the Ripple litigation by imposing a $125 million fine but further enabled offerings of crypto tokens without SEC oversight (Stempel, Reference Stempel2025).

What the above suggests is that merchant participation in governance shaped institutional structures. De Long and Shleifer (Reference De Long and Shleifer1993) tied European city growth to merchant institutions, while Weingast (Reference Weingast, Lamoreaux and Wallis2017) showed how medieval towns integrated merchants into political decision-making, improving property rights, lowering taxation, and increasing commercial security. Blockchain-based smart contracts and DAOs continue this tradition, offering private legal systems that fill gaps left by state law.

Even during the decline of medieval merchant law, private governance persisted in illicit markets and industry arbitration associations such as the London Maritime Arbitration Association and the Grain and Feed Trade Association. These examples underscore that non-state ordering never disappeared but was absorbed or overshadowed until blockchain revived scholarly interest in autonomous systems.

Both lex mercatoria and the merchant republics of the Middle Ages demonstrate how decentralized, merchant-controlled governance emerged to facilitate commerce when state enforcement was weak. Similarly, blockchain-based smart contracts and DAOs fill gaps where formal law is underdeveloped or less effective. Yet neither historical merchant law nor blockchain governance is truly stateless: merchant institutions operated alongside city and state authorities, and production often required guild or governmental permission, just as blockchain systems remain nested within contemporary legal frameworks.

Adjudication and enforcement

Adjudication and enforcement are central to any governance system, making them a useful point of comparison between lex mercatoria and blockchain. Critics often argue that blockchain lacks adjudication because it has no analogue to merchant court judges, suggesting a sharp break from the law merchant. Yet blockchain does not eliminate adjudication so much as reconfigure it. A related critique claims that by automating enforcement through code, blockchain displaces the human judgement integral to traditional legal processes, thereby departing more fundamentally from the logic of lex mercatoria.

The logic of smart contracts shows why this critique is only partly persuasive. Smart contracts are designed to eliminate ambiguity in advance by encoding every possible state of execution into code. By doing so, they reduce the scope for interpretation that would ordinarily require adjudication in customary or case-based systems. When disputes arise that fall outside the scope of the contract’s code, they do not disappear; instead, resolution is shifted to external mechanisms such as state courts, DAOs, or governance processes like blockchain forks. In this way, blockchain governance does not abolish adjudication but relocates it, reproducing dispute resolution functions in different institutional forms.

Concrete examples make this clearer. On a DEX, for instance, a smart contract can be written to execute a token swap automatically once both parties deposit the specified assets. Under traditional contracting, disputes could arise over delivery timing or allegations of breach. In the DEX context, however, the contract executes only if both deposits occur, thereby eliminating the possibility of one-sided failure. This design removes ambiguity ex ante, minimizing the need for interpretive adjudication. Still, boundary disputes remain possible, such as hacking incidents or errors introduced through oracles, that reveal the limits of automation.

Rather than eliminating human judgement, blockchain merely attempts to minimize reliance on it through ex ante specification in code. Whereas medieval commercial practice depended on human adjudicators to fill gaps and resolve disputes, blockchain seeks to preempt ambiguity through smart contracts. Yet this effort is never fully successful. When contingencies arise that code cannot address, governance mechanisms such as DAO votes or hard forks perform roles analogous to merchant adjudication. The 2016 Ethereum ‘DAO hack’ makes this clear: a vulnerability allowed an attacker to siphon funds, and pre-programmed rules offered no remedy. Developers and token holders had to deliberate collectively and ultimately vote for a hard fork to reverse the transactions. Such actions constitute an institutional response resembling the convening of merchant courts when customary practices failed. These episodes show that blockchain enables a form of collective adjudication, where human judgement reenters through consensus rather than through a single magistrate.

Enforcement reveals an additional divergence. As Volckart and Mangels (Reference Volckart and Mangels1999) emphasize, medieval commercial order was embedded in guild structures that not only adjudicated disputes but also provided merchants with physical protection and coercive means to ensure compliance. Blockchain networks lack any comparable capacity for physical enforcement. Instead, they generate confidence through cryptography, consensus mechanisms, and institutional recognition. Where guilds complemented custom with force, blockchains complement code with decentralized trust and external validation. Although the absence of coercive enforcement may appear to be a limitation, it also underscores blockchain’s significance: it demonstrates how law-like order can emerge even without physical sanctioning power, sustained through code, consensus, and reputation.

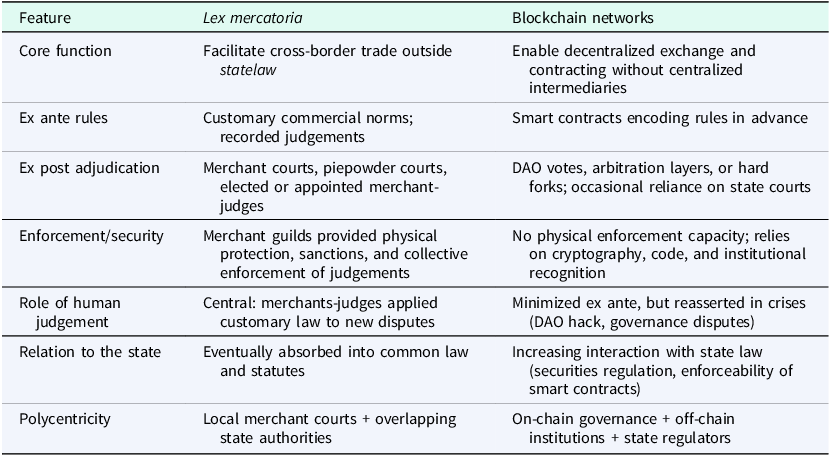

Table 1 synthesizes the discussion of how blockchain extends, mirrors, or departs from the institutional logic of the medieval law merchant across the dimensions of core function, rules, adjudication, enforcement, human judgement, relationship to the state, and polycentricity.

Table 1. Comparative institutional features of lex mercatoria and blockchain networks

Conclusion

Both medieval merchant law and contemporary blockchain systems arose to support commerce where existing legal institutions were inadequate. Lex mercatoria developed when common law was slow and ill-suited to the needs of long-distance trade, leading merchants to rely on customary rules and tribunals, while blockchain networks and DAOs provide technological infrastructures that reduce transaction costs through automated, self-executing agreements. What unites these otherwise different systems is their polycentric character: each operated within a broader legal environment and gained significance through its interaction with state institutions, even as it enabled private ordering. Yet blockchain governance departs from its historical counterpart by substituting ex ante, code-based rule specification for the ex post judicial discretion of merchant courts. The comparison thus highlights a shift from judge-centred processes to code- and community-centred forms of autonomous legal ordering.

There is also reason to see blockchain networks as a technological version of medieval customary law. Several of the features of lex mercatoria, such as its ex post dispute resolution by merchant courts, may be less of an issue or challenge with blockchain networks. Blockchains substitute ex ante specification of rules for judicial discretion, yet when crises arise, governance mechanisms such as DAOs, arbitration, or hard forks play an adjudicative role. The comparison therefore illuminates not a perfect symmetry, but the evolution of autonomous law from judge-centred to code- and community-centred forms of adjudication.

Yet even with the above contrasts in mind, the fact is that blockchain does not (and perhaps cannot) eliminate ex post adjudication and enforcement needs through off-chain entities. One reason why a polycentric frame is useful is because it does not require us to choose between autonomous law and the state. A core feature of a polycentric system is that there is autonomy for bottom-up experimentation. Lex mercatoria and blockchain networks are each significant examples where autonomous law matters and innovation occurs from the ground up, but that depend for their effectiveness on the formal legal system. With a polycentric framework, we can have both autonomous legal order and government because polycentrism balances local and bottom-up autonomy within a broader and nested governance system.

The polycentric framing also has implications for the future of blockchain, much as the historical evolution of merchant law shaped the emergence of modern commercial order. Merchant law became foundational because public authorities ultimately accepted and incorporated it, and something similar may be necessary for blockchain. Advocates of ‘trustless’ and ‘permissionless’ design sometimes overstate blockchain’s maturity, and it remains uncertain how much impact these systems will have on commerce or governance. Although blockchain has existed since Nakamoto’s Reference Nakamoto2008 white paper and smart contracts since Buterin’s Reference Buterin2014 proposal, these technologies have had little time to stabilize relative to historical commercial institutions. For this reason, it is premature to treat blockchain as a fully developed successor to private customary law, though the historical assimilation of commercial custom into common and code law provides a useful lens for thinking about blockchain’s future governance.

Just as medieval merchant practice eventually influenced modern commercial law, blockchain networks may likewise shape contemporary legal frameworks as courts and regulators confront questions of smart contracts, digital assets, and decentralized organizational forms. Judges recognizing the enforceability of smart contracts echo earlier moments when common-law courts incorporated commercial custom, illustrating how new practices generated outside the state become part of a broader legal order. The central institutional frontier now concerns how blockchain will be situated within international and domestic legal systems, particularly as these technologies become intertwined with rapidly advancing artificial intelligence. Understanding how emerging digital institutions interact with established structures of law and government is therefore essential for scholars and policymakers interested in the future of polycentric governance in the modern world.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editors, guest editors, coeditors, and the referees for constructive and extensive comments. They used generative AI tools for language editing and stylistic refinement. All intellectual content, including the historical analysis of lex mercatoria, the conceptual framework for blockchain governance, and the comparative institutional analysis, was produced by the authors.