Introduction

The use of information and communication technology (ICT) in the workplace can have both positive and negative effects on employees’ work experience. On the positive side, ICT can be perceived as a recourse that assists employees in completing their tasks, enhances their problem-solving capabilities by increasing access to information (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Morgan and Hall2000), aids in flexible work options such as teleworking, which help to decrease work–family conflict, and improves employees’ performance by facilitating communication with other organizational members (Dewett & Jones, Reference Dewett and Jones2001). However, ICT can also be perceived as an additional job demand in the workplace due to the physical and/or psychological effort that employees face with technology. In this regard, Truța et al. (Reference Truța, Maican, Cazan, Lixandroiu, Dovleac and Maican2023) conceptualize ICT use as a specific job demand, suggesting that poor adaptation or overexposure to digital technologies may compromise employee well-being.

These technological demands include the frequent introduction of new systems or artificial intelligence tools, the constant need to update software and hardware, and increased accessibility to the workplace through digital devices. Such factors can blur work–life boundaries, intensify work–family conflict (Golden et al., Reference Golden, Veiga and Simsek2006), and increase expectations for productivity (O’Driscoll et al., Reference O’Driscoll, Brough, Timms, Sawang, Perrewé and Ganster2010). As a result, these technological demands can negatively impact employee’s work experience and lead to psychosocial consequences, such as technostrain. Salanova et al. (Reference Salanova, Llorens, Cifre and Nogareda2007) defined technostrain as a negative psychological experience comprised of high levels of anxiety, fatigue, skepticism, and inefficacy related to the use of ICT.

The experience of technostrain is particularly relevant in occupations characterized by continuous and intensive exposure to ICT. This study focuses on highly digitalized occupational contexts, where ICT is not merely a complementary tool but an essential component for the execution of daily tasks. This is especially the case in sectors such as online higher education and banking, both of which are defined by high technological demands.

For example, teaching and support staff in virtual universities rely heavily on a wide array of digital platforms and tools to plan and deliver classes, manage student interactions, conduct assessments, carry out administrative duties, and participate in institutional processes. Similarly, professionals in the banking sector operate in environments where operational processes have been fully digitalized. The use of intranets, customer relationship management systems, real-time financial platforms, and automated service interfaces has radically transformed workflow structures. Routine tasks that previously required face-to-face interaction are now managed through integrated digital systems, increasing both operational efficiency and technological demands.

Indeed, the European Working Conditions Survey (Eurofound, 2022) indicates that employees in the education and financial sectors report some of the highest levels of anxiety across professions. This underscores the psychological strain often associated with highly digitalized work environments, even though specific measures of technostrain have not yet been systematically established.

In this context, the literature suggests that in technology-intensive workplaces, employees are more likely to experience technostrain when organizational resources are insufficient to meet the demands associated with ICT use. According to the Job Demands–Resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2024), technostress emerges when technological demands exceed available resources, negatively affecting employees’ psychological well-being (Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Llorens, Cifre and Nogareda2007; Truța et al., Reference Truța, Maican, Cazan, Lixandroiu, Dovleac and Maican2023).

Previous research has shown that both personal and social resources are crucial in mitigating technostrain (Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Llorens and Cifre2013). Furthermore, effective leadership has been identified as a vital resource for coping with technological overload, as well as the quality of leader-member exchanges moderating the relationship between technological overload and work–family conflict (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Harvey, Harris and Cast2013). In this context, the relationship between self-efficacy (personal resources), leadership climate (social resources), and technostrain experience is of special interest.

At the individual level of analysis (Level 1), research has found that self-efficacy plays an important role in influencing perceptions and use of ICT (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Doll and Truong2004; Igbaria & Iivari, Reference Igbaria and Iivari1995; Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Grau, Cifre and Llorens2000; Truța et al., Reference Truța, Maican, Cazan, Lixandroiu, Dovleac and Maican2023). Bandura (Reference Bandura1997) defined self-efficacy as a “belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (p. 3). In this way, high levels of self-efficacy positively influence individuals’ motivation to use ICT (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Doll and Truong2004), and it acts as a buffer, ameliorating the negative effects of technostrain on employees’ psychological well-being (Compeau et al., Reference Compeau, Higgins and Huff1999; Levante et al., Reference Levante, Petrocchi, Bianco, Castelli and Lecciso2025; Llorens et al., Reference Llorens, Salanova and Ventura2007).

At the second level of analysis, the leadership climate plays a significant role in shaping how employees experience their work (i.e., with new technologies) and has a notable influence on employee psychological well-being (Schyns et al., Reference Schyns, Veldhoven and Wood2009; Schyns & Van Veldhoven, Reference Schyns and Van Veldhoven2010; Tuckey et al., Reference Tuckey, Bakker and Dollard2012). Furthermore, workers under transformational leaders experience less technostress compared with others (Çiçek & Kılınç, Reference Çiçek and Kılınç2021).

Leadership climate is conceptualized as the collective perceptions of employees within the same group regarding the behaviors exhibited by their leaders (Chen & Bliese, Reference Chen and Bliese2002). Therefore, leaders can play an active role in digitization by motivating and supporting their workers at a socio-emotional level as they face the ongoing challenge of learning to use new technologies (Cortellazzo et al., Reference Cortellazzo, Bruni and Zampieri2019). Moreover, leaders can increase employees’ self-efficacy levels and promote a more positive work environment (Bliese & Castro, Reference Bliese and Castro2000; Chen & Bliese, Reference Chen and Bliese2002; Yada & Savolainen, Reference Yada and Savolainen2023). Consequently, this study aims to examine the role of leadership climate as a predictor of self-efficacy, since leadership in an organizational setting is likely to be an important determinant of employee motivation in the use of ICT. Specifically, we are interested in how the leadership climate can reduce the level of technostrain by increasing levels of self-efficacy in highly digitalized job roles.

At the Individual Level, Self-Efficacy as a Predictor of Technostrain Experience

Technostrain can be considered a negative psychological experience characterized by high levels of anxiety and fatigue (affective dimension), skepticism (attitudinal dimension), and inefficacy (cognitive dimension) related to the use of technology (see Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Llorens and Cifre2013).

The most extensively studied component of technostrain is anxiety, which is characterized by high physiological activation, tension, and discomfort regarding technology. Experiencing anxiety may include fears such as pressing the wrong key and losing information, doubts about using computers for fear of making mistakes, and feeling intimidated by computers (Ragu-Nathan et al., Reference Ragu-Nathan, Tarafdar and Ragu-Nathan2008). Second, users often experience reduced psychological activation, manifesting as mental fatigue. A specific type of fatigue is information fatigue syndrome (IFS), which results from the demands of the Information Society and dealing with information overload (Lewis, Reference Lewis1996). The consequences of IFS include poor decision-making, difficulties in memorizing and remembering, and a reduced attention span. The third component of technostrain is skepticism; this concept is based on research into job burnout, specifically the burnout dimension known as “cynicism.” Skepticism in technostrain is defined as exhibiting indifferent, detached, and distant attitudes toward technology use. It specifically involves a cognitive distancing that includes developing indifference or a cynical attitude when users feel exhausted and discouraged by technology use (Schaufeli & Salanova, Reference Schaufeli and Salanova2007). The final component, inefficacy, refers to beliefs about the correct use of technology (i.e., judgments of ability regarding specific tasks or domains). When individuals face excessive technological demands, lack technological resources, and have limited personal resources (i.e., low self-efficacy and mental competencies), it leads to feelings of anxiety, fatigue, and skepticism, which in turn amplify their sense of inefficacy in using technology (Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Llorens and Cifre2013).

Research has demonstrated the crucial role of self-efficacy beliefs in coping with stress, particularly technostrain (Levante et al., Reference Levante, Petrocchi, Bianco, Castelli and Lecciso2025; Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Peiró and Schaufeli2002, Reference Salanova, Llorens, Ventura, Korunka and Hoonakker2014). According to Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1997), self-efficacy beliefs are key mechanisms that govern an individual’s level of functioning and the events that affect their life. These beliefs are based on the notion that one has the power to produce desired effects through one’s actions; without such beliefs, individuals have little incentive to act or persevere through difficulties. Furthermore, self-efficacy beliefs serve as significant determinants of the effort and persistence applied in goal pursuit (Bandura, Reference Bandura1997). Recognizing the importance of measuring self-efficacy accurately (Grau et al., Reference Grau, Salanova and Peiró2001), this study utilizes a specific measure of professional efficacy, defined as the belief in one’s ability to correctly fulfill one’s professional role (Cherniss, Reference Cherniss, Schaufeli, Maslach and Marek1993). This choice is particularly relevant, given the characteristics of the sample, which comprises highly digitalized professionals whose roles demand not only technical proficiency but also the capacity to manage a broad range of complex tasks in technology-mediated environments. In such contexts, the use of ICT is not merely an ancillary activity but a central and integrated aspect of everyday work.

Previous studies have highlighted that self-efficacy, beyond its technological specificity, plays a crucial role in moderating the relationship between ICT exposure and psychological outcomes. For instance, Salanova and Schaufeli (Reference Salanova and Schaufeli2000), as well as Salanova et al. (Reference Salanova, Llorens and Cifre2013), demonstrated that professional self-efficacy can buffer the negative effects of digital demands, such as burnout and technostrain.

Additional research suggests that the impact of ICT use on well-being is influenced by self-efficacy (Shu et al., Reference Shu, Tu and Wang2011). For instance, employees with high self-efficacy perceive technology as easier to use and more useful (Chatzoglou et al., Reference Chatzoglou, Sarigiannidis, Vraimaki and Diamantidis2009; Venkatesh, Reference Venkatesh2000) and show greater motivation to engage with technology (Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Grau, Cifre and Llorens2000). Conversely, individuals with low self-efficacy often experience significant anxiety related to technology use (Downey & McMurtrey, Reference Downey and McMurtrey2007) and are more likely to perceive job demands as threats, thereby increasing technostrain (Chou & Chou, Reference Chou and Chou2021; Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Llorens, Cifre and Nogareda2007; Shu et al., Reference Shu, Tu and Wang2011). Consistent with prior research, at the individual level, we expect that employees with higher professional self-efficacy are likely to experience less technostrain. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1: Professional self-efficacy is negatively associated with technostrain experience in highly digitalized job roles.

At the Second Level, the Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Leadership Climate

Shamir et al. (Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993) were among the first to propose that positive leadership enhances followers’ perceptions of self-efficacy. The authors suggested that such leaders increase the intrinsic value of efforts and goals by aligning them with valued aspects of the follower’s self-concept, thus harnessing motivational forces such as self-consistency, self-expression, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. Similarly, Bandura (Reference Bandura1997) argued that self-efficacy is formed from four primary sources of information: enactive mastery experiences, verbal persuasion, vicarious learning, and the interpretation of physiological and affective states. Therefore, leadership can also boost followers’ self-efficacy through enactive mastery (i.e., positive performance experiences) and fostering positive emotional states. When leaders assist employees in focusing on the processes involved in their work (e.g., by providing information and social support), which helps optimize outcomes and, in this case, reduce technostrain, they enhance self-efficacy (Llorens et al., Reference Llorens, Salanova and Ventura2007).

Likewise, leadership can provide a point of reference for employees’ vicarious learning, helping to define what kinds of behaviors it is good to develop (role modeling) (Shamir et al., Reference Shamir, House and Arthur1993; Walumbwa et al., Reference Walumbwa, Avolio and Zhu2008). Additionally, leaders can use verbal persuasion in order to convince employees that they have what it takes to succeed and help employees to become more confident in their abilities (Walumbwa et al., Reference Walumbwa, Mayer, Wang, Wang, Workman and Christensen2011).

In line with existing literature on self-efficacy and leadership, we investigate shared perceptions of leadership climate as the most immediate predictor of self-efficacy at the individual level. Previous research has consistently recognized leadership as a pivotal aspect of organizational climate, representing the collective view of employees regarding leadership behaviors (Chen & Bliese, Reference Chen and Bliese2002; Gavin & Hofmann, Reference Gavin and Hofmann2002). According to Chen and Bliese (Reference Chen and Bliese2002), leadership climate is defined as “a shared group-level climate variable that reflects group members’ perceptions of the extent to which the leaders of their group provide task-related direction as well as socio-emotional support to subordinates” (p. 549), referring to it as a facilitative and supportive environment. For instance, leadership focused on fostering interaction within groups and achieving group-related goals (James & James, Reference James and James1989), as well as promoting follower welfare through socio-emotional support and a positive working environment. Building on this, leadership can enhance employee self-efficacy by clarifying work roles and offering sufficient socio-emotional support within the group (Bliese & Castro, Reference Bliese and Castro2000; Chen & Bliese, Reference Chen and Bliese2002).

Previous research suggested that leadership play an important role in employee’s health and well-being (Skakon et al., Reference Skakon, Nielsen, Borg and Guzman2010). For instance, leadership can provide individualized support, appreciation, and consideration for their employees, positively influencing their self-efficacy regarding task achievement (Chen & Bliese, Reference Chen and Bliese2002; Munir & Nielsen, Reference Munir and Nielsen2009), thereby enhancing their sense of well-being. Furthermore, cross-level research has shown that leadership climate correlates positively with job satisfaction (Schyns et al., Reference Schyns, Veldhoven and Wood2009), organizational commitment (Schyns & Van Veldhoven, Reference Schyns and Van Veldhoven2010), work engagement (Tuckey et al., Reference Tuckey, Bakker and Dollard2012), performance (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kirkman, Kanfer, Allen and Rosen2007), and well-being (Bliese & Britt, Reference Bliese and Britt2001). However, a recent systematic review highlighted the limited representation of leadership literature in the technostress domain, underscoring the importance of investigating leadership-centric technostress experiences (Rademaker et al., Reference Rademaker, Klingenberg and Süß2023). Considering these arguments, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2: Leadership climate is positively associated with self-efficacy in highly digitalized job roles.

On the other hand, despite the growing interest in technostress and its impact on employee well-being, to the best of our knowledge, no prior research has directly examined whether leadership climate influences technostrain. Nevertheless, related studies suggest that broader organizational factors may serve as protective buffers against technology-related stressors. For instance, Khasawneh (Reference Khasawneh2018) found that a supportive organizational climate can reduce the negative effects of technophobia, highlighting the importance of contextual elements in shaping employees’ experiences with digital demands.

Although empirical studies directly addressing the relationship between leadership climate and technostrain are still scarce, an expanding body of literature highlights the central role of leadership in shaping employee adaptation and well-being in digitally mediated work environments. Li et al. (Reference Li, Seach and Yuen2025), for example, demonstrated that leadership is significantly and negatively associated with technostress, showing that leaders who offer strategic direction, emotional support, and clarity during digital transitions help employees better manage the demands of technology-intensive work. Similarly, other studies have found that effective leadership can reduce technostress by enhancing employees’ sense of control, competence, and confidence in navigating digital tools and systems (Rohwer et al., Reference Rohwer, Flöther, Harth and Mache2022). Additionally, leaders with strong digital awareness and strategic vision have been shown to play a crucial role in guiding teams through technological change while mitigating experiences of overload and anxiety (Zeike et al., Reference Zeike, Bradbury, Lindert and Pfaff2019).

These findings align with a broader stream of literature demonstrating that leadership plays a protective role in reducing occupational stress and psychological strain. For example, Skakon et al. (Reference Skakon, Nielsen, Borg and Guzman2010), in a comprehensive review, concluded that leadership behaviors, such as emotional support, recognition, and clear communication, consistently predict lower stress levels and improved well-being. Likewise, a positive leadership climate, characterized by task-oriented guidance and socio-emotional support, has been associated with reduced psychological distress in work settings (Bliese & Britt, Reference Bliese and Britt2001).

Taken together, this evidence suggests that leadership functions as a key psychosocial resource that enables employees to cope more effectively with high job demands and manage stress across various work contexts. Extending this reasoning to the digital workplace, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Leadership climate is negatively associated with technostrain experience in highly digitalized job roles.

Building upon previous theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence, we propose that the relationship between leadership climate and technostrain is not purely direct but is explained by the mediating role of employees’ professional self-efficacy. Grounded in the Job Demands–Resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2024), this proposition considers leadership climate as a key job resource that influences employee well-being through two complementary mechanisms. First, it contributes to the development of personal resources, such as self-efficacy, which act as protective factors against the negative effects of job demands, including technostrain. Second, leadership climate may exert a direct effect by reducing technostrain and mitigating its consequences (Rohwer et al., Reference Rohwer, Flöther, Harth and Mache2022).

This dual mechanism is supported by extensive research. Bakker and Demerouti (Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007) contend that personal resources mediate the relationship between job resources (e.g., leadership) and outcomes related to psychological well-being or strain, such as technostrain. Tummers and Bakker (Reference Tummers and Bakker2021) further reinforce this view by emphasizing that leadership simultaneously shapes both personal resources and levels of occupational stress.

In addition, recent findings suggest that both technological self-efficacy and social support from supervisors may act as stress suppressors in the relationship between employees and ICT use (Tuckey et al., Reference Tuckey, Bakker and Dollard2012). Even in highly digitalized work environments, social support continues to play a crucial role in the management of technostrain (Cazan et al., Reference Cazan, David, Truța, Maican, Henter, Năstasă, Nummela, Vesterinen, Rosnes, Tungland, Gudevold, Digernes, Unz, Witter and Pavalache-Ilie2024).

Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of leadership climate not only as a facilitator of personal resource development, such as self-efficacy, (Chen & Bliese, Reference Chen and Bliese2002), but also as a key factor in promoting psychologically healthy work environments amid increasing technological demand.

Considering these theoretical and empirical insights, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 4: Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between leadership climate and technostrain in highly digitalized job roles.

Method

Sample and Procedure

This study employed two convenience samples comprising a total of 877 workers from technology-intensive environments, organized into 76 work teams. These participants can be considered highly digitalized users, as ICT is not merely a set of support tools but rather a core component of their daily professional activities. It is important to note that the primary aim of this study lies in examining employees working in digital-intensive sectors, rather than to conduct cross-cultural comparisons. Although the two samples originate from different countries, they represent distinct professional domains, higher education and banking, selected due to their high reliance on ICT in everyday tasks.

The first sample comprised 387 employees (54% women) from an online university in Spain, with 23% being academic staff and 77% administrative workers, distributed across 44 work units. Notably, these employees work in an educational institution where all student services are exclusively provided online, and 53% of them are telecommuters. In terms of employment conditions, 57% of the employees had full-time contracts, with an average tenure of 5.8 years in the company (SD = 3.63). Age data for this sample were not collected, as the participating organization expressed concerns that including this information could compromise participant anonymity. In line with ethical research standards and respecting the conditions established by the institution for its involvement in the study, the research team agreed to exclude this variable.

The second sample comprised 490 bank employees (51% men) in Uruguay, distributed across 32 work units. The mean age of this sample was 46 years (SD = 9.09), ranging from 24 to 62 years. The vast majority (94%) of these employees had full-time contracts, with an average tenure of 22.2 years in the company (SD = 11.8).

In both cases, data collection was conducted online. The research team emailed participants with instructions on how to complete the self-report questionnaire used in the study. Subsequently, to ensure data protection and anonymity, random passwords were assigned to each participant.

Measures

All employees from both samples were invited to complete the online version of the RED-ICT questionnaire (Resources, Emotions/Experiences, and Demands related to Information and Communication Technologies; Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Llorens and Cifre2013), which consists of a comprehensive battery of psychometric scales. For the purposes of this study, three validated scales from the instrument were specifically selected and applied to assess the constructs of interest in both organizational contexts.

Self-efficacy was assessed using the professional self-efficacy scale by Schwarzer (Reference Schwarzer1999), adapted to the work-setting domain. The scale comprised seven items for the clerical and bank samples and nine items for the academic staff sample. All items refer to self-efficacy related to a specific task (e.g., “I will be capable of efficiently handling unexpected events in my work”). The Cronbach’s alphas are .89.

Technostrain was evaluated using four previously validated scales (Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Llorens, Cifre and Nogareda2007): anxiety with four items, fatigue with four items, skepticism with four items, and inefficacy with four items. Examples of items include: “I feel tense and anxious when I work with ICT” (anxiety), “It is difficult for me to relax after a day’s work using ICT” (fatigue), “As time goes by, ICT interest me less and less” (skepticism), and “In my opinion, I am inefficacious when using ICT” (inefficacy). The Cronbach’s alpha is .87.

Leadership climate was assessed using a four-item scale developed by Salanova et al. (Reference Salanova, Llorens, Cifre and Martínez2012). A sample item is “The person who supervises me directly organizes and distributes responsibilities.” The Cronbach’s alpha is .94.

Respondents answered items about self-efficacy, technostrain, and leadership climate using a seven-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always/every day).

Control variable: At the team level, we controlled for team size, given its substantial variation across teams.

Analysis Strategy

Descriptive analyses (mean, standard deviation, and correlations) and internal consistency tests (Cronbach’s alpha) were conducted for the study variables.

In addition, the data in this study had a hierarchical structure, with individual-level variables (N = 877 employees; Level 1) nested within teams (N = 76 teams; Level 2) (e.g., Hofmann, Reference Hofmann1997). Following Bliese (Reference Bliese, Drasgow and Schmitt2002), we analyzed the data using a random coefficient model (RCM), also known as hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Gavin & Hofmann, Reference Gavin and Hofmann2002), with the HLM software (Raudenbush et al., Reference Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon and du Toit2011). We used RCM to test the cross-level effect of leadership climate on technostrain experience and the mediating effects of self-efficacy on the relationship between leadership climate and technostrain experience.

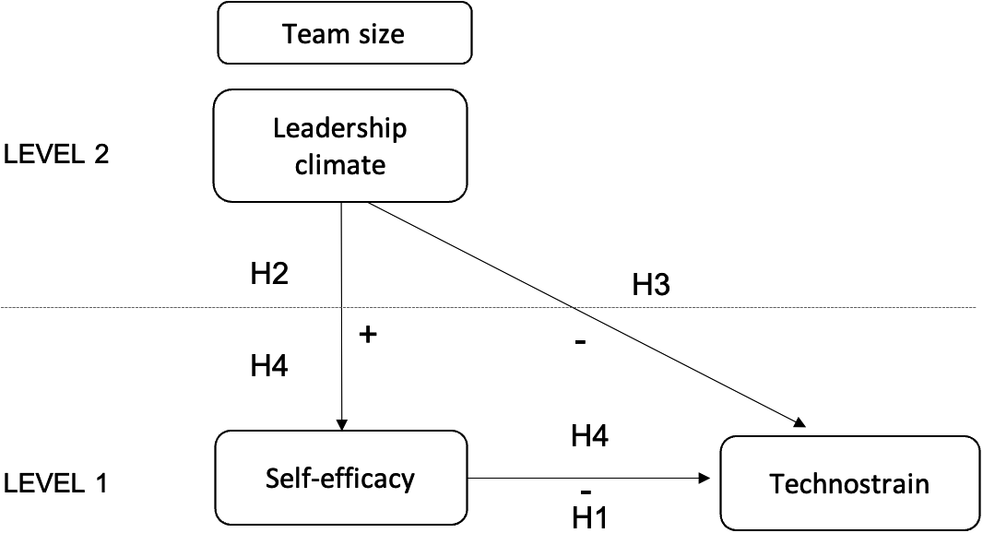

Additionally, cross-level mediation analyses were conducted following Baron and Kenny’s (Reference Baron and Kenny1986) approach, involving four steps: (a) examining the relationship between the dependent variable (technostrain) and the mediator variable (self-efficacy) (Hypothesis 1); (b) assessing the relationship between the independent variable (leadership climate) and the mediator variable (Hypothesis 2); (c) examining the relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variable (Hypothesis 3); and (d) determining the change in magnitude of this relationship once the mediator was added (Hypothesis 4). These steps are represented as Models A–D (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Multilevel model of technostrain in teams: expected hypotheses (H).

Finally, to estimate 95% confidence intervals for the average indirect effects, we employed the Monte Carlo method (MCM), a form of parametric bootstrapping. This method involved generating 20,000 random draws from the estimated sampling distribution of the estimates. The MCM is suitable for multilevel models where lower-level mediation (i.e., mediation by Level 1 variables) is predicted, as in our theoretical model (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Preacher and Gil2006).

Results

Aggregation Tests

To support the aggregation of leadership climate, we used two complementary approach (Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski, Klein, Klein and Kozlowski2000): a consistency-based approach (computation of the intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]) and a consensus-based approach (computation of average deviation index (ADM(j)) and rwg(j)).

We calculated intraclass correlation (ICC1 and ICC2; Bliese, Reference Bliese, Klein and Kozlowski2000) and tested whether average scores differed significantly across teams (indicated by an F-test from a one-way analysis of variance contrasting team means on leadership climate). ICC1 indicates the proportion of variance in ratings due to team membership, whereas ICC2 indicates the reliability of team membership. For leadership climate, we obtained good support for aggregation (ICC1 = .09; ICC2 = .68) because the ICC1 values are above the .12 recommended level (James, Reference James1982) and the ICC2 values are above the .47 recommended cutoff (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, White and Paul1998). The results obtained, F(75, 801) = 16.54, p < .01, show that there was a significant degree of between-units differentiation and support the validity of the aggregate leadership climate measure. Moreover, average rwg(j) value for leadership climate (rwg(j) = .69) was near the .70 recommendation (James et al., Reference James, Demaree and Wolf1993; Klein & Kozlowski, Reference Klein and Kozlowski2000) and the mean AD value for leadership climate (AD = 1.08) was less than 1.2 (Burke & Dunlap, Reference Burke and Dunlap2002). Considering these results, we concluded that there was good within-group agreement, further justifying the aggregation of collective responses to the second level of analysis.

Descriptive Analysis

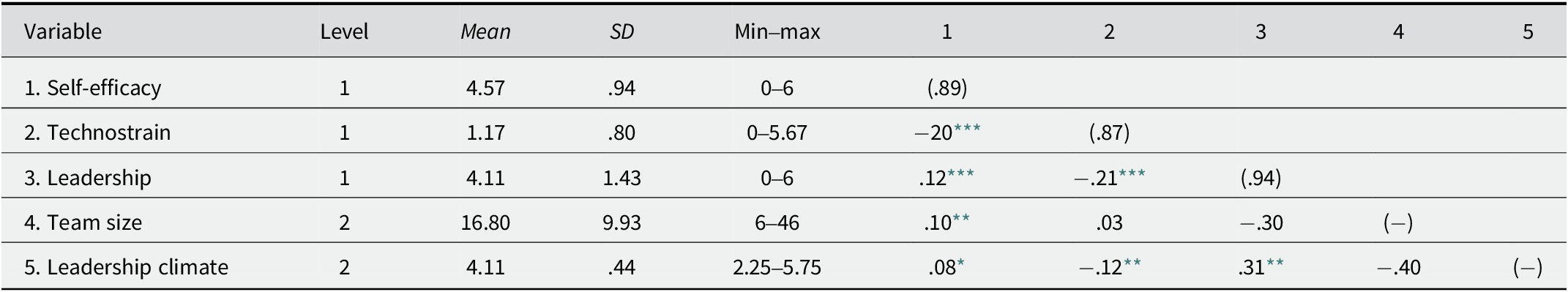

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and intercorrelation for the variables in the study at Level 1 (individual) and Level 2 (leadership climate). The reliability analyses revealed excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding the recommended threshold of .70 (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1951), thereby supporting the methodological robustness and precision of the scales used to assess the constructs examined in this study. Additionally, the table includes the minimum and maximum observed values for each scale, allowing for a clearer interpretation of the mean scores across variables. The correlation table indicates that self-efficacy is negatively correlated with technostrain and positively correlated with leadership climate and team size. Moreover, leadership climate is negatively correlated with technostrain experience, as expected. In contrast, team size is not correlated with the unit’s shared perception of leadership and technostrain.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the study variables at Level 1 (individual; N = 877 individuals) and Level 2 (teams; k = 76 teams)

Note: Reliability estimated with Cronbach’s alpha is presented in the diagonal between parentheses.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

Hypothesis Testing

Table 2 shows the results of direct and mediating effects in the prediction of technostrain experiences. Concretely, Model A reveals a significant negative relationship between individual self-efficacy and technostrain (γ = −.48, SE = .01, t = −10.93, p < .01), providing strong support for Hypothesis 1. This indicates that employees with higher self-efficacy experience lower levels of technostrain.

Table 2. Analyses of direct and mediating effects in the prediction of technostrain experience

Note: DV = dependent variable (all measured at the individual level).

a Level 1 (individual level) predictor.

b Level 2 (leadership climate) predictor.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

In Model B, the cross-level effect of leadership climate (Level 2) on individual self-efficacy (Level 1) is positive and significant (γ = .13, SE = .05, t = 2.53, p < .01), supporting Hypothesis 2. This result suggests that employees perceive greater self-efficacy in environments characterized by supportive leadership climates. Team size, used as a control variable, did not show a significant relationship with self-efficacy (γ = .01, SE = .00, t = 1.72, ns).

Model C demonstrates that leadership climate (Level 2) negatively predicts individual technostrain (γ = −.22, SE = .08, t = −2.71, p < .001), thus supporting Hypothesis 3. Employees who work in contexts with positive leadership climates report lower technostrain. Team size, used as a control variable, did not show a significant relationship with leadership climate and technostrain (γ = .01, SE = .00, t = 1.72, ns).

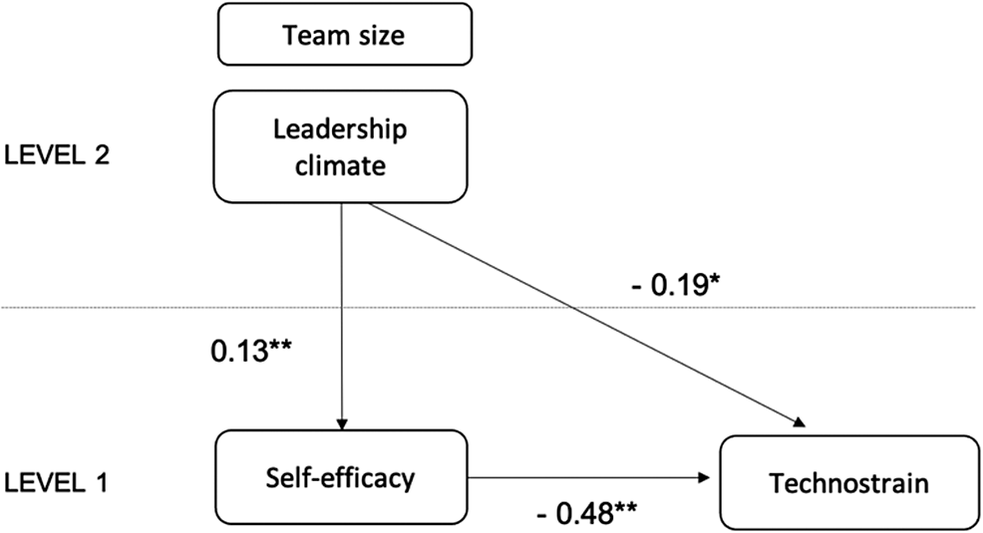

Following the procedure outlined by Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986), the necessary conditions for testing mediation were met. Model D, which includes individual self-efficacy as a mediator, confirms a mediation effect. When self-efficacy was added to the model, the coefficient for leadership climate remained significant but decreased in magnitude (γ = −.19, SE = .08, t = −2.58, p < .05). Meanwhile, self-efficacy maintained a strong negative association with technostrain (γ = −.48, SE = .04, t = −10.93, p < .001). The control variable, team size, was nonsignificant in this model (γ = −.00, SE = .00, t = −1.96, ns).

Finally, the 95% confidence intervals for the simultaneous indirect effects via self-efficacy (lower = 0.03; upper = 0.08) indicate that the effect of leadership climate on follower technostrain was mediated through the personal resources of the employees (self-efficacy). Hypothesis 4 was thus supported (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Final model including the results of the cross-level effects for leadership climate, self-efficacy, and technostrain.

Note: *p < .05; **p < .01.

Discussion

The aim of this research was to examine the antecedents of technostrain experience, specifically examining the role of leadership climate as a predictor of self-efficacy and technostrain experience. The data supported all our hypotheses, and the results offer several extensions to research on technostrain, self-efficacy, leadership climate, and multilevel processes, with significant implications for organizational and managerial practices.

Firstly, as predicted in Hypothesis 1, the powerful motivational process of self-efficacy (Bandura, Reference Bandura2001) was confirmed. Therefore, self-efficacy has been demonstrated to motivate ongoing technology use (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Doll and Truong2004) and reduce the negative impact of ICT use, leading to technostrain (Shu et al., Reference Shu, Tu and Wang2011). Our findings align with recent research indicating that teachers with high levels of perceived self-efficacy for delivering interactive online instruction report lower levels of technostress (Cazan et al., Reference Cazan, David, Truța, Maican, Henter, Năstasă, Nummela, Vesterinen, Rosnes, Tungland, Gudevold, Digernes, Unz, Witter and Pavalache-Ilie2024; Chou & Chou, Reference Chou and Chou2021). This relationship may be explained by the confidence these professionals have in facing technological challenges while maintaining pedagogical quality, which reduces the perception of digital demands as threats.

Similarly, highly digitalized workers, such as employees in the banking sector, who possess personal resources or skills that allow them to adapt to technologically changing environments, are also less likely to experience technostress (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang and Lin2024). These findings reinforce the critical role of professional self-efficacy as a key psychological resource for effectively coping with highly digitalized and demanding work environments.

Second, this study clearly demonstrates that leadership climate is a crucial source of self-efficacy, confirming Hypothesis 2. This finding aligns with previous research (Chen & Bliese, Reference Chen and Bliese2002; Walumbwa et al., Reference Walumbwa, Hartnell and Oke2010, Reference Walumbwa, Mayer, Wang, Wang, Workman and Christensen2011), which has found that a shared perception of leadership climate is positively related to individual self-efficacy through various mechanisms. Thus, leadership can enhance followers’ perceptions of self-efficacy by clarifying tasks and providing socio-emotional support (Chen & Bliese, Reference Chen and Bliese2002; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Ng, Ng and Salleh2022).

Third, we also identified an indirect cross-level relationship between leadership climate and follower technostrain (i.e., confirming Hypothesis 3), where the impact of leadership climate on technostrain was mediated by individual perceptions of self-efficacy (i.e., confirming Hypothesis 4). Therefore, our results align with Salanova et al. (Reference Salanova, Llorens and Cifre2013), who suggested that leadership has the potential to increase levels of self-efficacy and reduce levels of technostrain in followers. In addition, leaders who promote autonomy, provide clarity, and support the development of digital competencies act as reducers of technostrain (Bauwens et al., Reference Bauwens, Denissen, Van Beurden and Coun2021; Rohwer et al., Reference Rohwer, Flöther, Harth and Mache2022).

Furthermore, our study contributes to research on leadership climate (multilevel research) and teams working with technology, highlighting its role in reducing technostrain experience. Leaders can enhance employees’ self-efficacy by providing sufficient socio-emotional support in the use of technology.

Finally, these findings have important implications for managerial practice. Organizations should actively promote leadership development initiatives that emphasize emotional intelligence, communication, and digital competence, which have been shown to be critical in managing technostress (Ertiö et al., Reference Ertiö, Eriksson, Rowan and McCarthy2024). Developing professional self-efficacy among employees, especially in technologically intense roles, can help them view digital demands as manageable rather than threatening.

Leadership can enhance employees’ self-efficacy through multiple mechanisms: (1) promoting successful task experiences through role-playing and simulations (i.e., enactive mastery experiences); (2) providing positive feedback and setting high performance expectations (i.e., verbal persuasion); (3) helping employees manage negative emotional responses associated with ICT use through relaxation techniques, mindfulness, and similar practices (i.e., emotional regulation); and (4) modeling ethical and effective behavior (i.e., vicarious learning). This leadership approach contributes to the development of “positive” technology-related jobs and the promotion of “positive” employees, in alignment with the principles of Positive Occupational Health Psychology (Salanova et al., Reference Salanova, Llorens, Cifre and Martínez2012).

Limitations and Further Research

The present study has several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings. First, we collected data from only one source, which increases the potential for biases resulting from common method variance (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Second, despite our adequate sample size (877 employees across 76 teams), the use of convenience samples from only two highly digitalized sectors (online higher education and banking) limits the generalizability of our findings. Although these sectors represent environments with significant technological demands, results may not necessarily extend to other industries with different technological landscapes or working conditions. Future research should explore other sectors and occupational groups to enhance the robustness and applicability of these findings across various contexts and industries.

Third, although the study included participants from two different countries, Spain and Uruguay, the cultural dimension was not the main focus of analysis. The samples were selected based on their involvement in highly digitalized sectors, rather than to represent intercultural variability. This methodological decision was driven by the study’s aim to investigate technology-intensive environments; however, it limits the extent to which observed differences can be interpreted through a cultural lens. Since participants belonged to distinct occupational contexts (i.e., online higher education vs. banking), it is not possible to determine with certainty whether differences in technostrain stem from cultural or sector-specific factors. This sectoral divergence complicates the isolation of purely cultural effects, as they are intertwined with professional role characteristics. Future studies should aim to include more culturally and occupationally diverse samples, ideally employing matched cross-cultural designs that control for sectoral differences. Such approaches would enable a more accurate assessment of how cultural values shape technostrain experiences and influence the effectiveness of leadership and personal resources in varied organizational contexts.

Fourth, the absence of age data for the Spanish sample constitutes a notable limitation. Due to confidentiality agreements established by the participating organization, age-related information was not collected. As a result, we were unable to examine potential age-related patterns in leadership climate, professional self-efficacy, or technostrain. This constraint is particularly relevant in light of growing interest in understanding how age influences the way employees experience and adapt to digital work environments. Indeed, age has been shown to exert a complex influence on technostrain, with findings varying depending on psychological factors, the nature of the work environment, the specific dimension of technostress assessed, and individual coping strategies. Some studies conducted in organizational contexts report a negative relationship between age and technostrain (Hauk et al., Reference Hauk, Göritz and Krumm2019; Ragu-Nathan et al., Reference Ragu-Nathan, Tarafdar and Ragu-Nathan2008), potentially due to greater emotional resilience, more effective emotional regulation, and accumulated experience with organizational change (Diehl & Hay, Reference Diehl and Hay2010; Scheibe & Carstensen, Reference Scheibe and Carstensen2010). However, a growing body of research also points to a positive correlation in certain contexts, suggesting that older adults may experience higher levels of technostrain, particularly in the form of anxiety, information fatigue, skepticism, or perceived inefficacy in using digital tools (Sánchez-Gómez et al., Reference Sánchez-Gómez, Cebrián, Ferré, Navarro and Plazuelo2020). These findings are often attributed to lower levels of digital familiarity (Tams, Reference Tams2017; Tams et al., Reference Tams, Thatcher and Grover2018), as well as to the fact that older users, unlike digital natives, feel the pressure to engage in a continuous process of cognitive and social adaptation to keep up with technological demands (Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2018).

In this regard, age should not be seen solely as a biological or demographic factor, but rather as a proxy for differentiated technological trajectories, with distinct cognitive, emotional, and experiential implications. Therefore, future studies should include age as a key moderating variable to gain a more nuanced understanding of how different generational cohorts perceive and respond to technostrain, and to help design organizational strategies that are more inclusive and age sensitive.

Fifth, our measure of self-efficacy was not specifically focused on technology-related tasks but rather assessed general professional self-efficacy. This choice was based on the inherently technological nature of the roles studied, in which digital tools are embedded within broader professional functions. However, we acknowledge that this approach may limit the precision with which the underlying psychological mechanisms are understood, particularly those directly related to specific technological competencies. The use of a general measure may reflect broader beliefs about professional competence, coping ability, or adaptability, potentially obscuring the specific role of technological confidence in mitigating technostrain (Zhang, Reference Zhang2023).

According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1997), domain-specific self-efficacy develops through mastery experiences and contextual cues. A measure focused on technological self-efficacy would have allowed for a more direct connection between digital demands and psychological responses such as technostrain. The absence of a domain-specific measure may therefore constrain the ability to fully isolate the mechanisms through which individuals assess their capacity to cope with technology-related stressors. Future research should thus consider including both general and domain-specific self-efficacy scales to enable a more nuanced understanding of their respective roles as moderators or mediators in the impact of technostrain.

Finally, the study was based on cross-sectional research. This implies that the relationships observed among leadership climate, professional self-efficacy, and technostrain processes need to be carefully interpreted, and no causal inferences can be made.

Therefore, as a starting point for future research, causal inferences could be drawn if future studies replicate our findings using experimental or longitudinal designs. In addition, other occupational samples should be tested with the theoretical model proposed in the present study (e.g., teleworking), in order to evaluate the generalizability of the results across diverse work settings and temporal frameworks.

Moreover, it would be beneficial for future studies to expand the range of personal resources specific to technology at both the individual level (e.g., mental competencies) and the collective level (e.g., collective efficacy).

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated the pivotal role of leadership climate in shaping employee self-efficacy and managing technostrain within organizational settings. Our findings confirm that a supportive leadership climate not only enhances self-efficacy among team members but also significantly reduces the technostrain experienced by them. These results underscore the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between leadership climate and technostrain, highlighting how effective leadership can mitigate the adverse effects of technological demands.

The practical implications of our research suggest that leaders can mitigate technostrain by providing consistent socio-emotional support, promoting positive interactions with technology, and modeling ethical behavior in ICT usage. Furthermore, training that enhances self-efficacy and fosters the perception of technological and social facilitators in the workplace can cultivate an environment conducive to positive technology experiences.

This study contributes to the existing literature by illustrating the multilevel impacts of leadership on employee well-being and technology engagement, offering valuable insights for organizational practice, and guiding future research on leadership in the digital era.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request due to privacy and ethical considerations.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: all authors; Data curation: M.V., S.L.; Formal analysis: M.V., S.L.; Funding acquisition: M.S.; Investigation: M.V.; Methodology: M.V., S.L.; Project administration: M.S., S.L.; Resources: M.S.; Software: M.V.; Supervision: M.S., S.L.; Validation: M.V.; Writing—original draft: M.V.; Writing—review and editing: all authors.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain (Grant No. PID2023-151776NB-C21) and by Universitat Jaume I (UJI-2024-23).

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.