Introduction

Pediatric patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) undergoing non-cardiac surgery have a higher perioperative morbidity and mortality risk. Reference Taylor, Habre and Arnold1,Reference Brown, Dinardo and Nasr2 Risk stratification of CHD patients has been studied; however, it is still unclear which patients should be cared for by a pediatric general anesthesiologist or a cardiac anesthesiologist. Reference Faraoni, Vo, Nasr and DiNardo3 At our quaternary care pediatric hospital, the team dynamics were strained between the cardiac and general anesthesiology teams due to practice variations in who would be assigned to provide anesthesia for CHD patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. This is a common theme amongst pediatric institutions and will likely continue to be a theme in the future, given the limited recruitment of anesthesiologists into the pediatric cardiac anesthesia subspecialty. Reference Nicolson4 The goal of this survey was to assess inter-team dynamics after the implementation of guidelines for which CHD patients require a cardiac anesthesiologist during their procedure.

Methods

Guidelines were created by the cardiac anesthesiology team (Appendix 1), based on the literature review and expert opinion, to identify the highest risk cases that would require care by a cardiac anesthesiologist. These guidelines included patients with shunt-dependent physiology (e.g., Blalock-Taussig–Thomas shunt, Sano shunt, patent ductus arteriosus stent, prostaglandin infusion), unrepaired cyanotic structural heart disease, palliated single ventricle physiology with ventricular dysfunction or requiring ionotropic support, severe pulmonary hypertension (excluding neonatal causes of pulmonary hypertension), severe left ventricular dysfunction with ejection fraction < 30%, severe valvular disease (e.g., mitral stenosis with gradient > 14 mmHg or left ventricular outflow tract obstruction with gradient > 90 mmHg), and Williams syndrome with high-risk features (e.g., Qtc > 500 ms, supravalvular aortic stenosis > 40 mmHg). Reference Taylor, Habre and Arnold1,Reference Watkins, Mcnew and Donahue5–Reference Saettele, Christensen and Chilson8

Additionally, a cardiac anesthesiologist was delegated to a daily consult role to streamline the communication and consultation between the general and cardiac anaesthesiology teams.

A survey was sent out to both teams to assess the clarity and workforce satisfaction after implementation of the guidelines. A baseline analysis of team dynamics, or pre-guideline survey, was not included because the primary focal point of this survey was post-guideline effectiveness.

An Institutional Review Board is not required for this study as it does not involve protected health information. No validated survey tool was available to address this specific scenario, so a new survey tool was created by the study team, which includes a process improvement specialist within the cardiology division.

Results

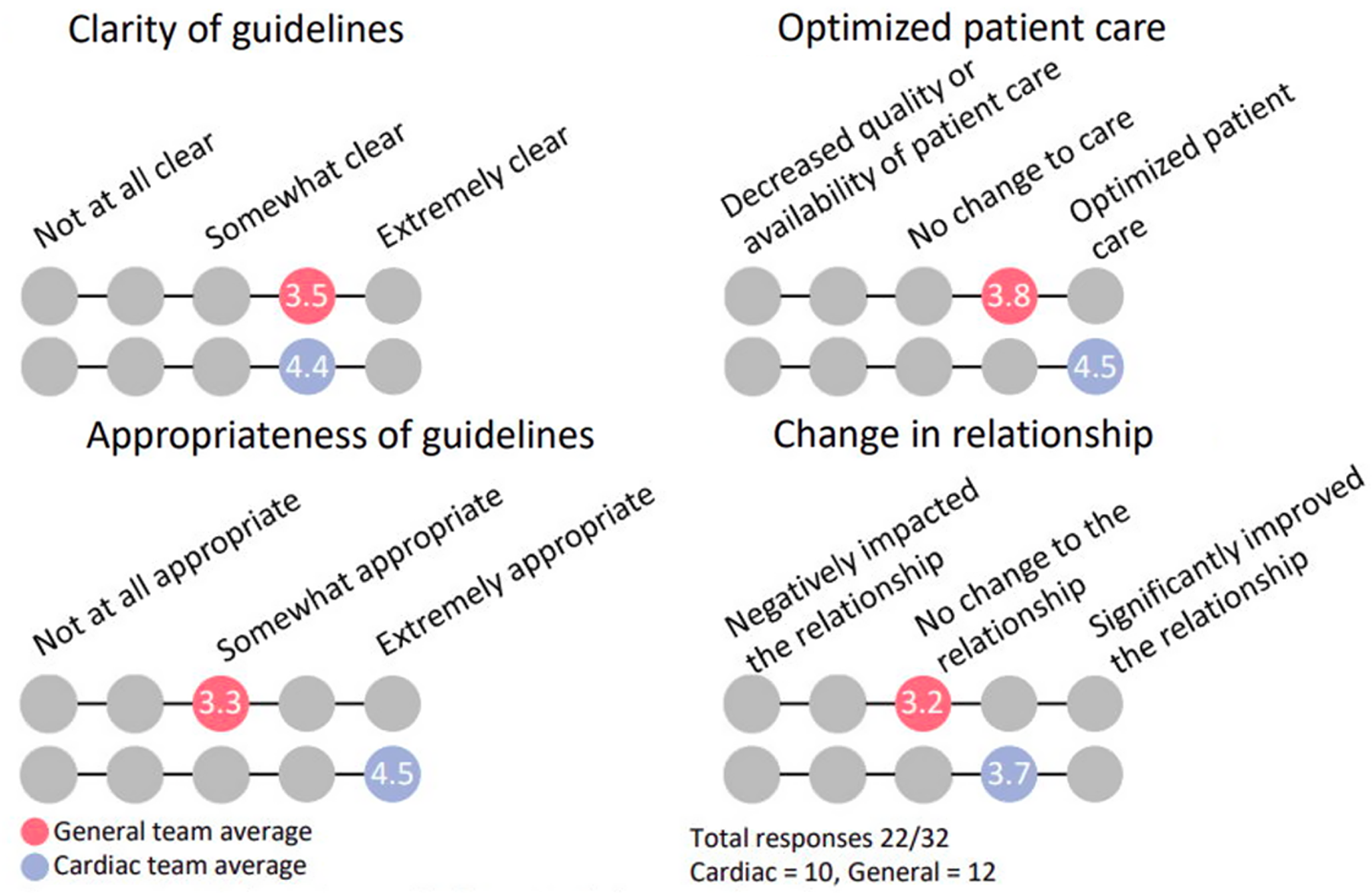

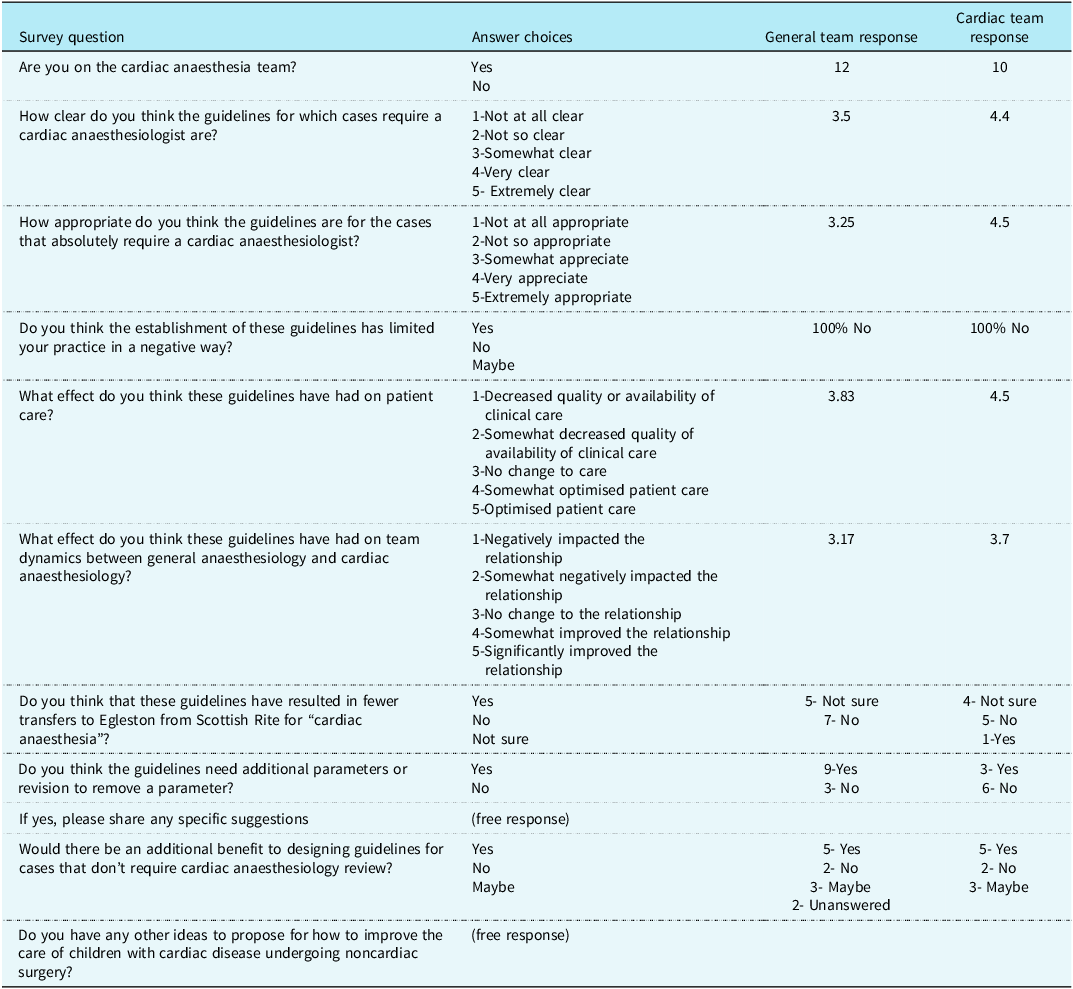

The survey consisted of 11 questions to address the impact and effectiveness of the guidelines. As illustrated in Table 1, four of the questions were multiple choice on a 5-point scale (not at all clear to extremely clear), five yes or no questions (e.g. whether the respondent is on the cardiac team, whether the guidelines need revision), and two free writing prompts. Out of the 12 cardiac anesthesiologists and 27 general anesthesiologists, 10 cardiac and 12 general anesthesiologists completed the survey. Prior to the guideline implementation, 66.6% of patients who met the criteria were cared for by the cardiac team and after the guidelines were instituted 100% of patients who met the criteria were cared for by the cardiac team. No respondents indicated a negative impact on the scope of their practice as a result of the guideline implementation. As shown in Figure 1, the cardiac team viewed the appropriateness of the guidelines more positively, 4.5 by cardiac versus 3.3 by general, and optimization of patient care more positively, 4.5 by cardiac versus 3.8 by general. The cardiac team also reported a more positive change in relationship between the teams, rated 3.7 by cardiac versus 3.2 by general. These results demonstrate a small mean difference which is not statistically significant, given the small sample size, but does have practical implications.

Figure 1. Survey outcomes.

Table 1. Survey and results

Discussion

The most important finding of this survey was that guidelines can quickly change the practice behaviour but a change in culture and team dynamics takes time. The complete adherence to the guidelines confirms the clarity of the guidelines and ease of use. This survey shows the implementation of guidelines was successful in improving consistency in assignment of cases to a cardiac anesthesiologist, although there was a discrepancy in acceptance of the guidelines between teams. Another important finding in this survey is that after guideline implementation, 33.3% of patients who would have been cared for by the general team were exclusively cared for by the cardiac team post-implementation. Although this fundamental change limited the scope of practice of a general pediatric anesthesiologist in our group by assigning a subset of cases to cardiac anesthesiologists, this limitation was not viewed as a negative impact on the overall scope of practice of general pediatric anesthesiology by survey respondents.

Inclusive guideline generation solutions involved faculty meetings and group-based discussions between both teams to create the guidelines; however, these guidelines were largely designed by the cardiac team. The discrepancy in team satisfaction is evident from a higher response rate from the cardiac anesthesiologists, with only 44% of general attendings responding versus 83% of cardiac attendings. We suggest that the response bias could be at least partially explained by engagement in the process of guideline creation. While the overall number of responses is small, particularly considering the lower response rate among general anaesthesiologists, our overall staffing numbers and structure are similar to other comprehensive congenital cardiac care centrers. Given the challenge in recruitment of pediatric cardiac anesthesiologists and improved survival among patients driving increased volumes of non-cardiac procedures in this population, we considered it equally important to improve consistency among cardiac anesthesiologists triaging cases as well as establishing a scope of practice that is maintainable for the general anesthesiology group.

While we cannot conclusively state that the results are generalizable to other institutions, the clear discrepancy between change in practice behaviour and workplace culture is a fundamental challenge encountered in all clinical practices. Creating a sustained change in organizational culture and dynamics requires staff engagement, promoting collaborative interpersonal relationships, visible leadership, and making small incremental changes which are continually assessed. Reference Willis, Saul and Bevan9,Reference Buck, Kurth and Varughese10 All of these goals require considerable time, which is often difficult to afford with current healthcare economic realities. The issue of how to triage cases to pediatric cardiac anesthesiologists and general pediatric anesthesiologists is currently challenging most centrers.

Future directions should assess if there is an association between patient outcomes, including incidence of intraoperative adverse events, and improvement in team dynamics. Iterations of the guidelines may benefit from input from the general anaesthesiology team such that engagement will be perceptibly increased and, therefore, acceptance may also increase. The limitations of this survey are the response rate and single institution results. Overall, positive long-term social dynamic change in anaesthesiology departments is complex and requires strong leadership and engagement of all personnel.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Peggy Vogt: This author helped conceptualize the report, draft the initial manuscript, review and revise the manuscript and approved of the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the study

Justin Long: This author helped conceptualize the report, collect data, review and revise the manuscript and approved of the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the study.

Julie Libby: This author helped collect the data and approved of the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the study.

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

None.

Appendix 1. Guidelines for Patients Requiring a Cardiac Anaesthesiologist for Noncardiac Procedures

CHF congestive heart failure, ACE inhibitors angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, PS pulmonic stenosis, RVOT right ventricular outflow tract, AS aortic stenosis, LVOT left ventricular outflow tract, MS mitral stenosis, mmHg millimetrs of mercury, PDA patent ductus arteriosus, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, CICU cardiac intensive care unit, ECMO extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, VAD ventricular assist device, LVH left ventricular hypertrophy, ECG electrocardiogram, LV left ventricle, RV right ventricle, QTc corrected QT interval.