1. Introduction and motivation

Do events irrelevant to politics, such as the results of sporting events, influence citizens' assessments of government performance and voting behavior? The effective functioning of democracy fundamentally relies upon the ability of citizens to be considered in the development of their political opinions and in making voting decisions at election time. Many classic models of political behavior assume that citizens are rational in evaluating governments' performance. According to this view, voters reward or punish incumbent governments and individual candidates based on relevant performance indicators and policy responses (e.g., Key, Reference Key1966; Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1981). For example, citizens reward governments for effective management of the economy and punish governments for negative economic performance (e.g., Lewis-Beck, Reference Lewis-Beck1988; Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). In this account, citizens can effectively update their views of governments based on relevant events.

However, an influential strand of literature sharply questions these assumptions. Recent studies seek to illustrate that voters are significantly influenced in their evaluations by “irrelevant events” for which governments and individual politicians cannot credibly be held responsible. Examples include natural disasters and shark attacks, weather events, lotteries, and irrelevant tax referenda at the local level (Achen and Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2002, Reference Achen and Bartels2016; Huber et al., Reference Huber, Hill and Lenz2012; Bagues and Esteve-Volart, Reference Bagues and Esteve-Volart2016; Heersink et al., Reference Heersink, Peterson and Jenkins2017; Sances, Reference Sances2017). In addition, Healy et al. (Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010) find that the results of college football games in the run-up to election day had a significant impact on state-wide and national election results by altering the personal sense of well-being and emotional state of voters depending on whether their team won or lost (see also Miller, Reference Miller2013). These findings raise particular concerns for those who argue that voter competence is ultimately a core requirement for effective democratic accountability. For instance, Lenz (Reference Lenz2012: 7) concludes that Healy et al.'s study on sports games and incumbency support “could describe the reality of democracies as being closer to the worst-case view.”

Recent research instead takes the view that concerns about the rationality and competence of voters may be overstated and that the mechanisms of electoral accountability are too nuanced to infer that voters are insufficiently rational (e.g., Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita, Reference Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita2014; Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, de Mesquita E and Friedenberg2018; Gailmard and Patty, Reference Gailmard and Patty2019). In turn, a series of dissenting studies contend that the original findings on the impact of irrelevant events themselves constitute false positives, despite employing well-constructed research designs and best social science practice (Fowler and Montagnes, Reference Fowler and Montagnes2015a, Reference Fowler and Montagnes2015b; Fowler and Hall, Reference Fowler and Hall2018). To effectively interrogate the findings on irrelevant events and voting behavior, we require more robust evidence on the effects of such events in different contexts, particularly those with a distinct electoral system, as well as a different political and sporting culture.

Which countries, cases, and methods are appropriate to identify the effects of irrelevant events? Busby et al. (Reference Busby, Druckman and Fredendall2017: 349) note that “[t]he study of irrelevant event effects in politics is an emerging area of inquiry, and going forward, we urge scholars to systematize it so as to avoid haphazardly choosing events.” Besides the importance of case selection strategies, Busby and Druckman (Reference Busby and Druckman2018) advise researchers to replicate findings from irrelevant event studies on different samples. Following these recommendations, we identify a case that constitutes a likely environment to observe effects of “irrelevant events.” In doing so, we test existing theoretical assumptions by moving beyond the United States to focus on a country with a different political and institutional system.

More precisely, we examine whether inter-county senior men's Gaelic football and hurling matches in Ireland affect political opinions and voting behavior. Based on the standards proposed in previous literature, Ireland constitutes a “best case” setting to test for the effects of sports matches on political outcomes, as it has particularly high rates of sporting attendance and reported interest in sports. Even though Gaelic football and hurling might not be very well known internationally, these sports are extremely popular in the country and deeply embedded in Irish social and cultural life (Reilly and Collins, Reference Reilly and Collins2008; Liston, Reference Liston and Inglis2015; Rouse, Reference Rouse2015). Besides, hurling and Gaelic football are amateur sports associated with tight links between supporters and their county team. The close affiliation between players and the community, and the deeply embedded geographic nature of Gaelic games strongly enhance Irish citizens' identification with their local team. These ties between supporters and their local team are therefore at least as strong as those between fans and both professional and NCAA football and basketball teams in the United States that the literature has previously examined (SI Section A).

We combine all available constituency-level data on the performance of candidates across general elections between 1922 and 2020 and all local elections between 1942 and 2019 with sports results of Gaelic football and hurling teams. Given that the regional teams correspond closely to electoral districts, we can assign games to constituencies. Almost all of these games were single-game knock-out matches, meaning that these games are important sporting events likely to induce strong emotional reactions among their large audiences (Healy et al., Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010). Overall, we fail to find an effect of irrelevant events on voting behavior. Wins or losses by the local county team do not systematically influence vote shares for incumbents or politicians from government parties.

We then shift the focus from macro-level election results to the level of individual voters using an “unexpected event during survey design” approach (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020).Footnote 1 A total of 135 games in the national hurling and Gaelic football championships took place during the field periods of the 2002 and 2007 Irish National Election Studies. Leveraging information on the interview completion date and the respondents' counties of residence, we compare political opinions of respondents who answered the questionnaire shortly before and after important championship matches of their regional teams. Results of the local team do not affect respondents' attitudes toward the Irish Prime Minister or opinions regarding the individual's preferred political party.

Our findings illustrate that concerns about the incompetence of citizens and their capacity to evaluate political performance and make rational voting decisions effectively may be overstated (see also Fowler and Montagnes, Reference Fowler and Montagnes2015a; Wuttke, Reference Wuttke2019; Baccini and Leemann, Reference Baccini and Leemann2021). Irish citizens’ opinions' and voting behavior appear unaffected by irrelevant events such as the outcome of sports matches. We contend that this could be due to strong levels of political knowledge, and close relationships between voters and local politicians that help voters make their choices without relying on mood. Alternatively, the regularity and importance of sports matches in Ireland may, counter to expectations, make it easier for citizens to identify games' influence on their mood and thus restrict spill-over into other domains like politics. Our findings indicate the need to further consider how the salience of sports conditions the impact of irrelevant events on political opinions, even where the existing literature would predict a strong likelihood of such effects. The results also underline the importance of employing designs best suited to approximating causal effects to test for the generalizability and robustness of surprising findings in other contexts.

2. Argument and expectations

Why would sporting outcomes affect citizens' evaluations of elected politicians, candidates from government parties, or the incumbent government as a whole? Prior research emphasizes three—partially overlapping—mechanisms underlying the impact of irrelevant events.Footnote 2

First, some authors emphasize that in elections, voters engage in “blind retrospection.” Individuals who experience painful, negative experiences “punish” incumbents for these events despite the fact they are clearly beyond the control of elected officials. Rather than rationally assessing governmental effects on their welfare, voters engage in a form of ignorant “rough justice” punishing incumbents when experiencing pain, whether this is attributable to the government or not (Achen and Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2016: 144). Achen and Bartels argue that disengaged and uninformed citizens are especially likely to “kick the government” because of such painful experiences. This “blind retrospection” mechanism fits closely with the impact of droughts, floods, or shark attacks and the punishment apportioned to incumbents following such disasters.

Second, irrelevant events may be framed as fundamentally concerned with the cognitive shortcuts voters employ in the attribution of blame or credit. In some cases, voters are “rationally” seeking to minimize cognitive costs by relying on information readily available to them. For example, material well-being could influence vote choice, but the citizen may not consider whether the personal circumstances can be accurately attributed to government performance or decisions. This logic clearly overlaps with the concept of blind retrospection. However, the particular emphasis here is on the struggle voters encounter in identifying whether and which political leaders are to be held responsible for changes in their personal circumstances (e.g., Sances, Reference Sances2017). This difficulty in attributing responsibility is most clearly illustrated through the impact of changes in individuals' finances through lottery wins or irrelevant tax referendums on voting patterns (Bagues and Esteve-Volart, Reference Bagues and Esteve-Volart2016; Sances, Reference Sances2017).

Third, in line with previous psychological findings, prominent political science literature emphasizes that individuals' mood and emotions influence their attitudes in entirely distinct domains (Healy et al., Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010; Busby et al., Reference Busby, Druckman and Fredendall2017; Goerres et al., Reference Goerres, Arens and Rabuza2019). When an individual's mood is good and sense of well-being is high, individuals tend to evaluate events and actors more positively than when their mood is low (Isen et al., Reference Isen, Shalker, Clark and Karp1978; Forgas, Reference Forgas1995). The above mechanisms similarly identify a crucial role for emotional and cognitive biases. Yet, from this logic, contemporaneous affect filters through from a variety of different potential sources into voting considerations. Mood “spills over” and alters political evaluations: when mood is high, voters fixate on positive feelings and reward incumbents, but “kick” incumbents when mood is low (Miller, Reference Miller2013).

Sports results are particularly useful to examine the effect of irrelevant events on mood and thus on voting behavior and attitudes. First, sporting wins and losses influence individuals' moods directly and through social network effects, as individuals “bask in reflected glory” from their teams' victories (e.g., Cialdini et al., Reference Cialdini, Borden, Thorne, Walker, Freeman and Sloan1976; Knoll et al., Reference Knoll, Schramm and Schallhorn2014). Second, one cannot reasonably expect that the decisions of politicians have any plausible impact on the outcome of a match. Third, voters have no reason to weigh the government's response to a sporting event when deciding how to vote as distinct from certain other types of quasi-random events. Following a natural disaster, for example, a government's emergency management or lack of planning may be subject to criticism. Voters may factor in their evaluation of the governmental preparation for the disaster when formulating their views. For a sporting win or defeat, the government's response will not be subject to any such scrutiny, especially in the immediate aftermath of the event.

Any effect of sports results on political opinions, evaluations, and voting behavior will only operate through the mechanism by which the game's outcome influences voters' mood and well-being. For this reason, prior research on the impact of irrelevant events has devoted significant attention to sports results. Most of this research has focused on the United States. Healy et al. (Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010) find significant effects of wins or losses of local US college football and basketball teams on senate, gubernatorial, and presidential election results using county-level data. They conclude that the “findings underscore the subtle power of irrelevant events in shaping important real-world decisions” (Healy et al., Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010: 12804). Similarly, Miller (Reference Miller2013) connects results of baseball, basketball, and American football franchise teams to mayoral elections and finds that “winning sports records boost incumbents’ vote totals and likelihoods of re-election, exceeding in magnitude the effect of variation in unemployment” (Miller, Reference Miller2013: 59). In a meta-analysis of key findings in the irrelevant events scholarship, Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Huber and Mo2020) identify the effects of sports results as the clearest example of “genuine” irrelevant events and the set of findings that prove most robust to this point.

The conflicting findings on irrelevant events suggest that two conditions may need to hold for an effect to follow. First, the event must be capable of altering voters' moods sufficiently for a potential effect to follow while remaining demonstrably “irrelevant” to political outcomes and performance. In other words, individuals must have clear links to and investment in the irrelevant events of interest. Second, voters are unmotivated to access information beyond mood to guide their behavior and attitudes (Busby and Druckman, Reference Busby and Druckman2018).

Our hypotheses follow existing studies on the influence of sports games on political opinions and voting behavior. The first hypothesis focuses on differences between candidates who won a seat at the previous election and challengers not currently represented in parliament. Incumbency thus relates to holding or not holding a seat in a parliamentary assembly. The literature would assume that the outcomes of irrelevant events result in a reward or punishment of incumbents. Voters are expected to respond to the stimulus that follows from their team winning or losing, which could affect their mood and—in turn—influence their vote.

Hypothesis 1: Incumbents whose local sports team has won (lost), experience an increase (decrease) in vote shares.

Incumbency status might not only depend on whether or not a candidate represents the constituency, but also whether a candidate's party is holding government office at the time of an election. This differentiation is crucial in multi-member districts. Several candidates from the governing party could run in the same district, but not all of these candidates were elected to parliament in the previous election. Yet, candidates of current government parties may still benefit or suffer from irrelevant events due to their links to the government's performance.

Hypothesis 2: Candidates from the incumbent government party whose local sports team has won (lost), experience an increase (decrease) in vote shares.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 relate to aggregated voting behavior (see e.g., Healy et al., Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010). We also expect differences in political opinions for survey respondents depending on the outcome of irrelevant events if the logic holds. More precisely, following Busby et al. (Reference Busby, Druckman and Fredendall2017), we posit that citizens whose local team won a match would express more positive views of the Prime Minister and their preferred party shortly after the match.

Hypothesis 3: Citizens whose local team has won (lost) express more positive (negative) opinions toward political actors after the match.

3. Sports results in the Irish context: the case of Gaelic games

Based on the theoretical assumptions above and the existing criteria from research on irrelevant events, Ireland should constitute a case with strong effects of sporting events on political opinions. Engagement with and interest in sport is very high in Ireland, and we would expect that sports results will have a particularly strong influence on individuals' mood and well-being. For example, a cross-national representative survey shows that over 95 percent of Irish respondents are somewhat or very proud when the national team is successful in a sports competition (ISSP Research Group, 2009 and SI Section A). In the same survey, approximately half of the Irish respondents disagreed that there is too much sport on television. In comparison, only 35 percent of US respondents expressed disagreement. If sporting results do in fact influence voters' evaluations of candidates for election and government performance, this is most plausible when citizens feel emotionally invested in their teams. The Irish context presents such a case.

The impact of sports results as irrelevant events on political outcomes in Ireland is best tested by focusing on wins and losses in Gaelic games (Gaelic football and hurling) competitions. These sports are unique to Ireland and are administered by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), which is Ireland's largest voluntary organization (Liston, Reference Liston and Inglis2015). They are amateur sports and have the highest participation rates in the country (Reilly and Collins, Reference Reilly and Collins2008). The All-Ireland football and hurling championships, contested every summer (April–September), are the most prestigious competitions. The GAA sells around 1.5 million tickets for the All-Ireland championships every year. As a point of comparison, approximately 4.9 million people live in the Republic of Ireland. Attendances at many individual matches exceed 50,000, and the finals of these tournaments have long been the central feature of the Irish sporting calendar (Kneafsey and Müller, Reference Kneafsey and Müller2018). The matches also attract television audiences that are similar or higher than audiences of American football in the United States or soccer in the United Kingdom and Germany (TAM Ireland, 2019 and SI Section A).

The All-Ireland Championships are contested on an inter-county basis by the 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland and the six counties of Northern Ireland and date back to before partition of the island.Footnote 3 All Irish citizens have a local representative inter-county team, and these county teams have corresponded in the vast majority of cases with constituency lines in elections going back to the 1920s. Until 1997, the GAA ran all All-Ireland matches on a single-elimination basis in which a defeat knocked a county out of the competition.

Turning to the institutional structure in Ireland, the country employs proportional representation using a single transferable vote (PR-STV) in general and local elections. Voters rank some or all of the candidates (including multiple candidates from the same party in some cases) in order of preference. PR-STV produces a candidate-centered system in which voters express preferences as much (if not more) for individual candidates as for parties (Farrell, Reference Farrell2011). Ireland has a multi-party system traditionally dominated by two broadly center-right parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, but also has a substantial number of left-of-center smaller parties. Ireland also has a long tradition of independent candidates with a significant number winning election to the national parliament (Dáil Éireann) and local councils. Ireland's electoral context offers additional advantages for examining the impact of irrelevant events on voting outcomes. Specifically, voters have various options if seeking to switch away from candidates they wish to punish. They can either vote for one of the other candidates or select away from candidates from the same (governing) party even if those candidates are not current officeholders.

4. Data and methods

We rely on two distinct methodological approaches to test whether sports games change political opinions in Ireland. First, we assemble a dataset of the available constituency-level election outcomes in all Irish general elections between 1922 and 2020 and all local elections between 1942 and 2019.Footnote 4 Data from general and local elections allow us to test the incumbency hypothesis at two levels of governance. The datasets consist of 5997 valid election-candidate observations from 30 general elections and 8655 observations from 14 local elections.

We measure our dependent variable of support for candidates as the percentage point difference in first-preference vote shares between election t and election t − 1. For example, if a candidate increased her first-preference vote share from 10 to 13 percent, the dependent variable equals 3. First-preference vote share under the Irish STV can be regarded as a sincere proxy of voter choice (Benoit and Marsh, Reference Benoit and Marsh2008: 878). This approach follows Healy et al. (Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010) and Fowler and Montagnes (Reference Fowler and Montagnes2015a), who also used officially reported vote shares as the dependent variable. In the next step, we collect all match results that occurred in the week before an election. We merge these datasets and checked whether the team located in the constituency played in the six days before a general or local election. Fifty-five championship games could be merged with candidate-level results in general elections. An additional 56 games could be assigned to local election results. The resulting dataset consists of three groups of candidates: those whose local team won, those whose local team lost, and those whose local team did not play, because the team was already out of the competition, did not have a fixture scheduled for the week before the election, or when the election did not take place during the All-Ireland championship. A total of 838 candidates in general elections (14 percent) and 2277 candidates (26 percent) in local elections are “treated” by a match of their regional team taking place in the week before the election. Figures A3–A5 show the number and distribution of candidate-observations in each group and election.

To test hypothesis 1, we create a variable indicating whether a candidate held a seat in parliament or a local council in the previous legislative cycle, i.e., whether or not the candidate was elected in t − 1. To test hypothesis 2, we code whether a candidate's party held government office in the previous cycle.Footnote 5 To be clear, the first hypothesis focuses on individual incumbency effects. The second hypothesis shifts the focus to party-level incumbency effects by distinguishing between government and opposition parties.

We test whether match results change vote shares for incumbents and non-incumbents compared to their previous election result. Recall that the dependent variable measures the percentage point difference between a candidate's first-preference vote-share in election t and election t − 1. The interaction terms between Match Treatment (Win; Defeat; Untreated) and Candidate elected in t − 1 (hypothesis 1) or Party: Government (hypothesis 2) capture whether previously elected politicians or candidates from government parties benefit from a win or defeat of the local team. Candidates whose regional team did not play in the week before an election or whose local team drew a match with the opponent serve as a baseline of “untreated” candidates.

Second, we combine the Irish National Election Studies from 2002 and 2007 and Gaelic football and hurling games during the fieldwork of these surveys. This set-up allows us to test whether the results of these matches influence survey responses about political opinions. Our “unexpected event during survey design” exploits the occurrence of “surprising” events during the survey period (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020). This design separates the survey into respondents who answered a survey shortly after experiencing a “shock” (i.e., the match of a local team) and a control group who answered the same questions before the surprising/unexpected event. The representative election studies were fielded after the election date, allowing us to cancel out short-term effects based on campaign events.Footnote 6 Over 85 percent of respondents were interviewed face-to-face, which reduces the chance that respondents answered the questionnaire strategically after a match. We test the hypotheses using two dependent variables: the rating of Bertie Ahern, the Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister), and the rating of a party (if any) with which respondents affiliate. All rankings can range from 0 (strongly dislike) to 10 (strongly like).

Table A2 lists summary statistics for the central variables measuring political opinions in the survey. The dataset consists of 3737 observations. Each observation is a survey respondent who completed the face-to-face interview within a window of ±6 days around a match of the local team, and who expressed her satisfaction with the Taoiseach (Prime Minister).Footnote 7 The number of respondents who ranked their preferred party is lower (2672) because a considerable share of respondents did not express any party affiliation. Figure A6 displays the number of interviews conditional on the difference in days to the match. 1138 respondents completed the survey within a narrow window of ±2 days from their county's match and have expressed their evaluation of the Prime Minister. In total, 134 Gaelic football and hurling matches took place during the field periods of the surveys.

We analyze the influence of the surprising event during the survey period in three ways. First, we run smoothed loess regressions and compare the development of approval for parties and the government in the week before and after a win or defeat. Second, after testing for the balance of individual-level characteristics of respondents answering the survey before and after a win or defeat, we assess the difference in means in the evaluation of the Prime Minister before and after matches, using windows ranging from ±2 to ±6 days. Third, we reweight the dataset using entropy balancing (Hainmueller, Reference Hainmueller2012) and run regressions with the “treatment” of answering before or after wins or defeats, separately for respondents in counties that experienced a win or defeat.

5. Results

The description of the results proceeds in three steps. First, we present the findings from our linear regression models using constituency-level election data. Second, we summarize the results from the “unexpected event during survey design” analysis. At the end of both sections, we report the results of several robustness tests and alternative model specifications.

5.1 Support for previously elected candidates

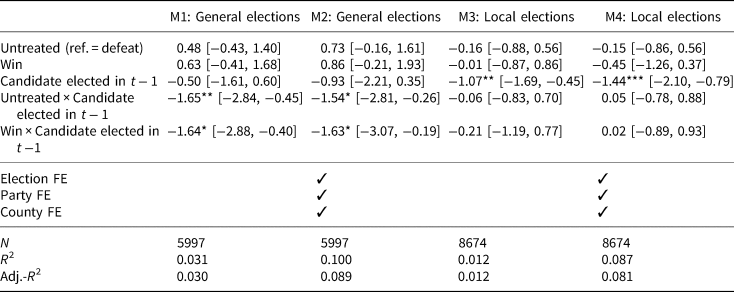

We begin with investigating whether candidates who were elected at election t − 1 benefit from defeats or wins of the local county team at the subsequent election. Table 1 reports the regression coefficients predicting percentage points changes in first-preference vote shares of a candidate. Positive values imply that a candidate received more votes in election t compared to election t − 1. We run two model specifications for each election type. First, we only include the match outcome, incumbency status of a candidate, and the interaction between the two variables (models 1 and 3). Additionally, we report a linear regression that includes fixed effects for the election and the candidate's party (models 2 and 4). Standard errors in all models are clustered by county team (Blair et al., Reference Blair, Cooper, Coppock, Humphreys and Sonnet2021).

Table 1. Predicting changes in shares of first-preference votes in general and local elections

Note: Robust standard errors clustered at the county level. 95 percent confidence intervals in parentheses.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

To make the results more easily interpretable, we report the fitted/expected values of the interaction effect between the candidate's incumbency status and the match outcome, along with 90 percent (thick vertical bars) and 95 percent (thin vertical bars) confidence intervals. Turning to the left-hand panel of Figure 1, we do not observe a greater change in first-preference vote shares for candidates in general elections whose local team won a match, compared to candidates whose team lost. We also do not find the expected pattern that candidates who were not represented in the previous parliament increase their vote shares if the local team lost. If anything, these findings suggest the opposite effect: defeats of the local team—counterintuitively—increase support for incumbent candidates.

Figure 1. Predicting changes in vote shares of rerunning candidates in Irish general elections (based on model 1 in Table 1).

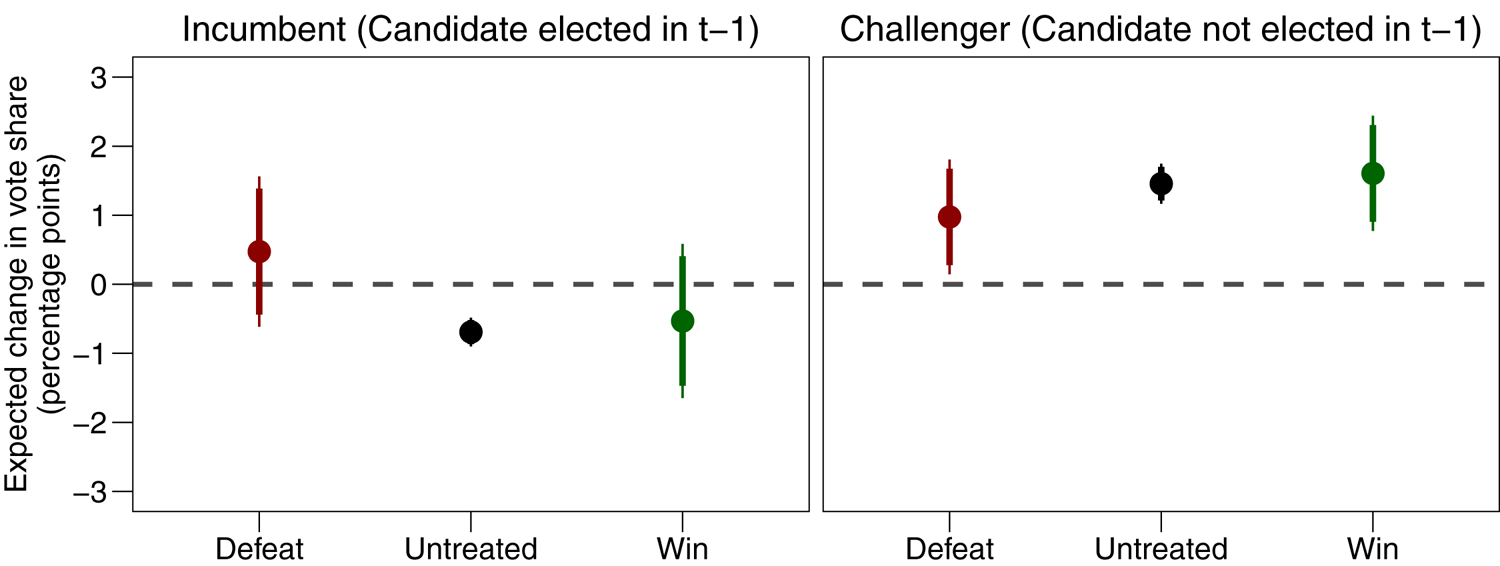

Turning to local elections (Figure 2) the patterns again do not support our hypothesis. The expected values for each treatment condition are virtually identical across the three conditions. Local councilors elected in the previous election tend to lose votes, whereas challenger candidates tend to increase their electoral support. Overall, the analyses of general and local elections do not offer any support for hypothesis 1.

Figure 2. Predicting changes in vote shares of rerunning candidates in Irish local elections (based on model 3 in Table 1).

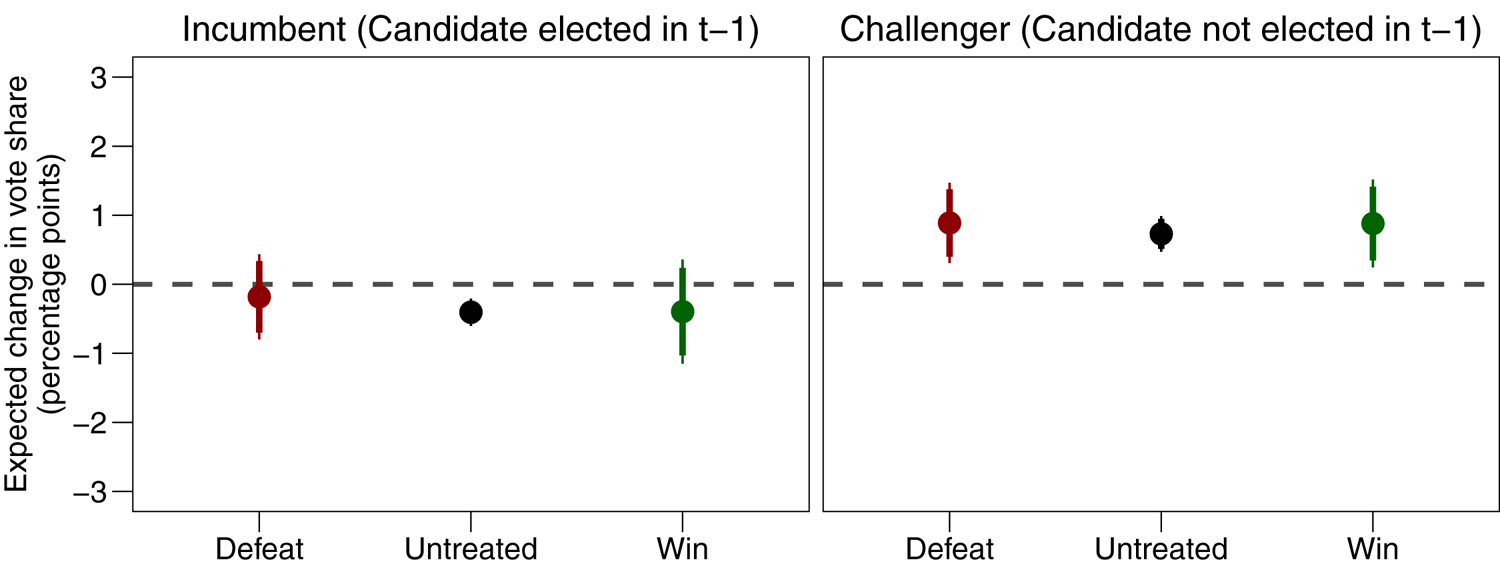

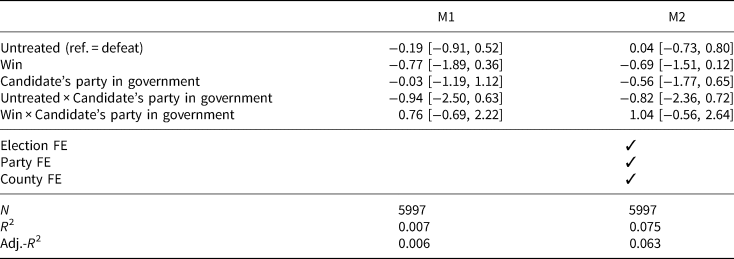

Hypothesis 2 posits that candidates from government parties increase their vote shares after a win of their local team. Figure 3 plots the expected values of changes in vote shares conditional on the interaction between match outcomes and party incumbency status (based on model 1 of Table 2). We do not observe any substantive differences for candidates from government parties if their local team lost or won. Candidates from opposition parties seem to lose votes if the local team wins. Yet, the coefficients of the interaction effect are small and do not reach statistical significance. These initial results do not suggest that sports games systematically influence support for candidates from government parties.

Figure 3. Predicting changes in vote shares of rerunning candidates from incumbent government parties and opposition parties in Irish general elections (based on model 1 in Table 2).

Table 2. Predicting changes in shares of first-preference votes for candidates from incumbent and opposition parties in Irish general elections

Note: Robust standard errors clustered at the county level. 95 percent confidence intervals in parentheses.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

We conducted various robustness tests for the analysis of constituency-level election results. First, measuring the change in support as the absolute difference in first-preference votes does not change our conclusions (Table A3; Figures A8 and A9). Second, we perform a specification curve analysis which reports the coefficient of interest for a variety of models with different sets of control variables (SI Section E). We limit the samples to previously elected candidates (hypothesis 1) or candidates from government parties (hypothesis 2) who experienced either a win or a defeat. Afterward, we run 128 models which correspond to all possible combinations between additional covariates. The three sensitivity curves underscore that the results do not systematically depend on the inclusion or exclusion of covariates, and that the coefficients are rarely statistically significant.

Third, we estimate changes in vote shares in general elections for the subsets of “stronghold” counties and “non-stronghold” counties. It is reasonable to expect that respondents with successful hurling or football county teams or from counties with a tradition of strong support will be more likely to be influenced by results. A county is coded as a stronghold if (1) the county team has experienced recent sporting success, such as winning a provincial final, and/or has recently reached the latter stages of the All-Ireland series in the previous decade, and/or (2) if the county has a significant traditional support base even if there has not been recent tournament success (SI Section I). Either of these elements, we believe, increases the likelihood that a win or loss of the county team will affect the mood of respondents living in a stronghold. If we observe the mechanisms from previous studies, we should observe them in strongholds. Yet, substantive results remain unchanged: incumbents in strongholds neither profit nor lose votes when the county team has won or lost a match, both in general and local elections (Table A4 and Figures A10–A12). Given that voters in strongholds are even more passionate about their county's success, these findings strengthen our conclusion that match outcomes in Gaelic games do not influence incumbency support.

Fourth, results persist when limiting the samples to candidates who could be matched unambiguously to only a single county (Table A5; Figures A13 and A14). Fifth, we conduct equivalence tests to assess whether our observed effects are substantively meaningful (Lakens et al., Reference Lakens, Scheel and Isager2018; Lüdecke et al., Reference Lüdecke, Ben-Shachar, Patil and Makowski2020). The null hypothesis tested is that the effect size and its confidence intervals are larger than a given value (lack of equivalence); the alternative hypothesis implies the effect is lower than this given value (equivalence). We assess the effect size of the interaction between a win of the local team and support for incumbents (SI Section F).Footnote 8 We choose symmetric equivalency boundaries of 0.3 standard deviations of the dependent variable. In our data, 0.3 standard deviations correspond to a change in vote shares of 1.6 percentage points in general and 1.4 percentage points in local elections. Healy et al. (Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010) report that a win for the local football team increases incumbent vote shares, on average, by 1.6 percentage points which mirrors our equivalence boundaries. The largest effect size reported in Busby and Druckman (Reference Busby and Druckman2018) also corresponds to approximately 0.3 standard deviations. For local elections, we reject H0 of no equivalence since the point estimate and confidence intervals fall entirely within the boundaries. In general elections, we observe a negative, statistically non-significant interaction effect, and the confidence intervals do not cross the upper boundary. Therefore, we again conclude that the effect is practically equivalent and not substantively meaningful. Our decision as to whether we can reject H0 of lack of equivalence for the impact of match results on support for candidates from government parties is undecided because the confidence intervals cross the upper equivalence bound, while the point estimate falls within the boundaries. However, the confidence intervals are very wide, and the point estimates could depend on the model specification (SI Section E).

To further assess whether our results are substantively meaningful, we conduct a placebo-permutation exercise (see e.g., Foos and Bischof, Reference Foos and Bischof2021). We hold the number of wins, defeats, and draws in each election constant, but randomly allocate these match results across constituencies in each election (SI Section G). We then re-estimate the model using the allocated match result as the independent variable and interact it with the incumbency status of a politician (hypothesis 1) or the government status of a candidate's party (hypothesis 2). For each scenario, we generate 1000 of such simulations and store the coefficient of the interaction between the permutated match result and incumbency status. The coefficients based on the observed treatments fall within the distribution of randomly simulated treatments. These robustness tests allow for the same conclusion: wins or defeats of the local team do not systematically affect support for previously elected candidates and politicians from the incumbent government.

5.2 Changes in political opinions: unexpected events during survey design

The section above reported results based on aggregate-level vote shares for candidates. However, we may need to turn to the level of individual voters to measure whether sports results influence political opinions. The “unexpected events during survey design approach” using the Irish National Election Studies from 2002 and 2007 allows for such an analysis.

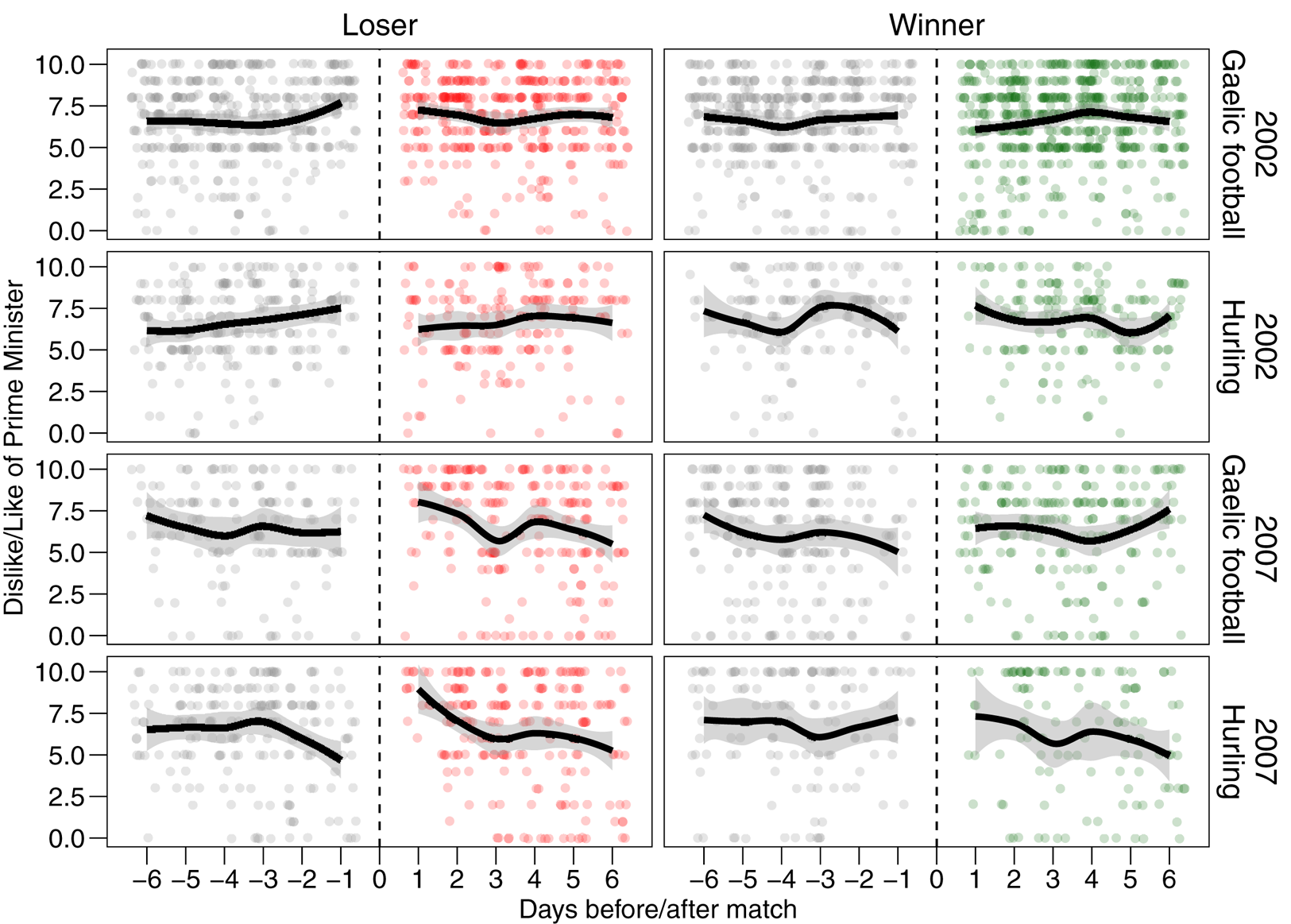

Figure 4 plots smoothed loess regression lines for the approval of the Prime Minister, separately for the week before and after matches. The x-axis shows the difference (in days) to a match of a respondent's county team. Each dot marks one respondent. The left-hand part of the plot displays the development for respondents that have lost a game. The right-hand part only considers respondents who live in a county that has won. Comparing the loess lines before and after the “treatment” of matches does not reveal any consistent trends. Satisfaction with the prime minister does not increase in any of the four scenarios in which a respondent's county wins. At the same time, we do not observe any negative shift for respondents whose county suffered a defeat.

Figure 4. Comparing rating of Irish Prime Minister before and after wins/defeats.

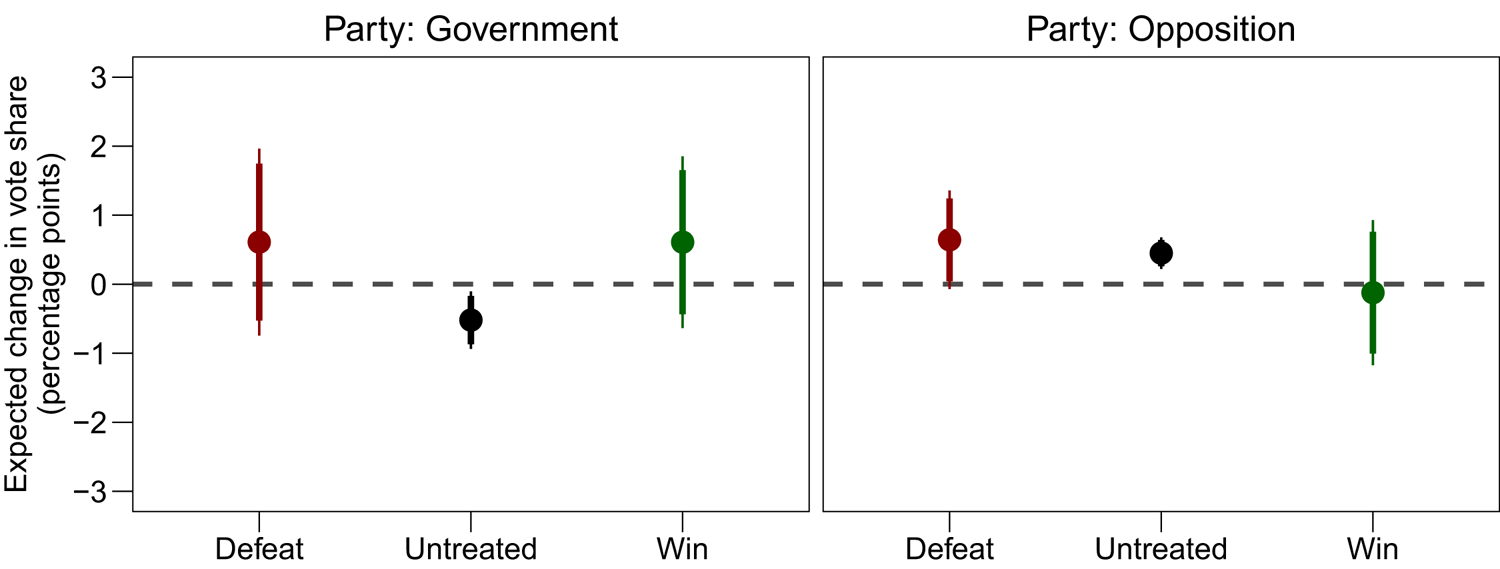

We extend the visual evidence by running t-tests for these scenarios using cut-off points ranging from ±2 to ±6 days. The samples of respondents who replied before and after matches are almost perfectly balanced, with no relevant individual-level variable being significantly different from 0. Figure 5 shows the differences in means for the ranking of the Prime Minister, based on different windows of days. Again, the analysis does not reveal any statistically significant differences for winners and only a positive change (against our expectations) for losers in the 2007 competition when selecting a window of ±2 days. This positive difference, however, diminishes when choosing a larger window.

Figure 5. Testing the difference in means of the rating of the Prime Minister for winners and losers, based on an increasing window of days.

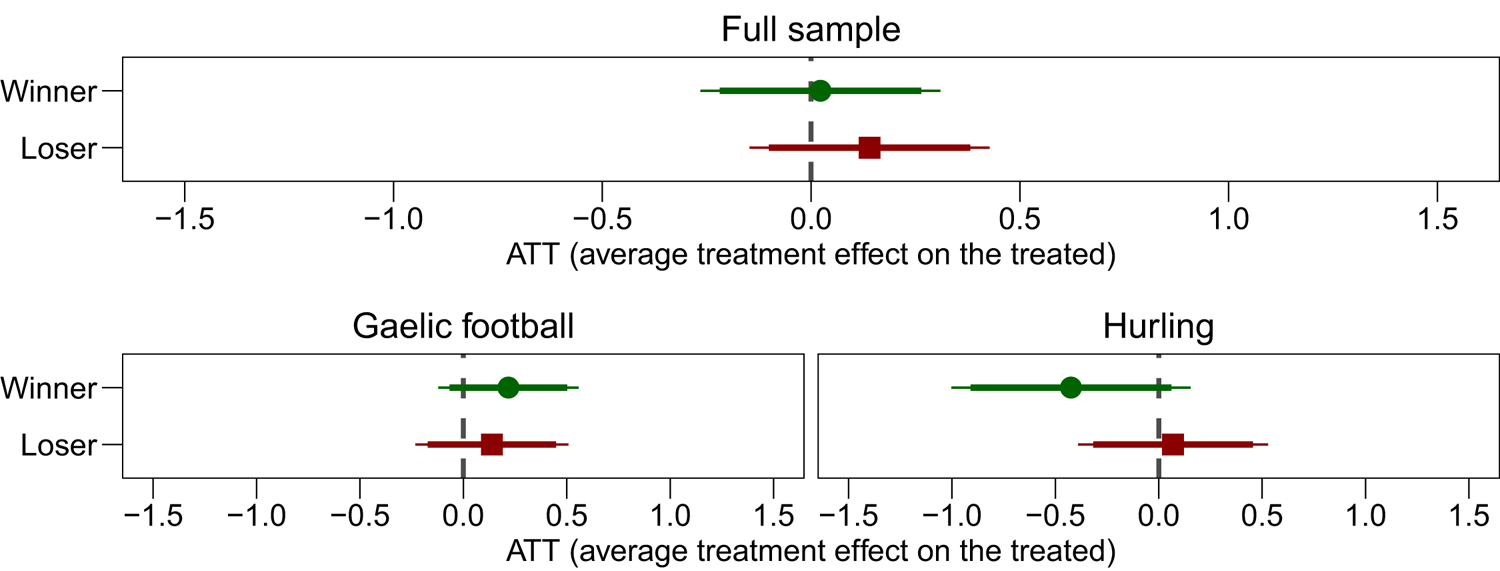

Third, we run general linear models after applying entropy balancing (Hainmueller, Reference Hainmueller2012).Footnote 9 The groups of winners and losers are reweighted so that the individual-level characteristics between treated and untreated respondents are as similar as possible. Figure 6 shows the estimated average treatment effects on the treated (ATT) for the four main scenarios (winning and losing in hurling and Gaelic football). Positive values indicate higher rankings of the Prime Minister. Horizontal bars indicate 90 percent (thick line) and 95 percent (thin line) confidence intervals. We would expect to observe negative treatment effects for losers and positive effects for winners. Yet, the treatments in all cases are not distinguishable from 0, and effect sizes are negligible (usually below 0.25 on a scale from 0 to 10). The estimates are not only statistically, but also substantively non-significant. To sum up, we do not find meaningful support for hypothesis 3.

Figure 6. Treatment effects of unexpected events (win/defeat) on the rating of the Prime Minister.

To assess the validity of the conclusions derived from the survey data, we follow Muñoz et al.'s (Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020) best practices. In particular, we focus on five main aspects (SI Section H). First, we check the balance between respondents who replied before or after matches and do not find any significant differences (Figure A24).Footnote 10 Second, we test whether respondents who experienced only a single game during the period of six days before and after their survey completion date react differently to match results. Some of the respondents either completed the survey between two matches of their county team or in a week in which both the regional hurling and Gaelic football teams played. For these respondents, it is hard to determine an unambiguous match treatment. We do not find any differences between the two samples (Figure A25).

Third, we use the approval ranking of the party a respondent feels affiliated to as an alternative proxy of political support. Again, we do not find any statistically significant treatment effect, and the effect sizes remain small (Figures A26 and A27). Losing does not result in worse evaluations of the preferred party while winning does not consistently increase approval.

Fourth, the survey from 2002 allows us to test whether active GAA members, who should be even more passionate about their county, express different opinions when they answered the survey after a match. Members of the sporting association do not show any differences in political views following a win or defeat of their local teams (Figure A28). Finally, we test whether results are stronger for respondents answering the surveys in July or August 2002 and 2007—the latter stages of the championship. Figure A29 does not show any notable patterns for this subset of respondents. The conclusions derived from the voter surveys do not depend on certain seasons, sports, subsamples, and even hold when only focusing on members of the sporting organization.

6. Discussion

In this paper, we assessed whether irrelevant events change political opinions and voting behavior. Following Busby et al.'s (Reference Busby, Druckman and Fredendall2017) recommendations and the standards proposed in prior research, we focus on a “most likely case” to observe such a pattern. As suggested by Busby and Druckman (Reference Busby and Druckman2018), we move beyond the case of the United States and try to replicate existing findings on a different sample. Prior research identified sports results as the clearest example of a truly “irrelevant” event with the capacity to affect mood and thus voting behavior (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Huber and Mo2020). We argue that sports in Ireland represent an ideal case to test the relevance of irrelevant events: sports in Irish life are very important, many Irish voters have close ties with their hurling and football teams, sports could indeed affect personal mood and well-being, and the electoral system offers opportunities to punish incumbent candidates and parties. We find little reason to believe that such results hold in the case of Gaelic games in Ireland, where such an effect would seem most likely. Instead, Irish citizens tend to demonstrate competence in distinguishing events for which governments and elected officials can be held responsible from those that they cannot.

Our results conflict with influential findings from the United States (Healy et al., Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010; Miller, Reference Miller2013) and suggest that these results are not necessarily generalizable to other political and sporting environments. Instead, our results indicate further evidence is needed to support the contention that “irrelevant events” are, in fact, politically relevant. Our systematic analysis suggests that factors conditioning effects through mood on voting behavior and political attitudes may vary depending on the cultural and political contexts.

One explanation for our null result could be the possibility that Gaelic games are not of interest for most Irish people. However, as we have shown above, Gaelic football and hurling attract a lot of supporters to stadiums, rank among the most popular sports in Ireland, create a strong sense of identity within counties, and voters can be clearly matched to their regional teams in a manner that is far clearer than for other sports and in other countries. A large share of the Irish population is actively or passively involved in Gaelic games. For instance, Ireland has over 2200 GAA clubs, and almost one in five respondents in the 2002 election study was a member of the association.

The chain between sports results, mood, and political opinions is a plausible explanation for the effect of irrelevant events, but with little evidence that the effects hold in Ireland. Similarly, in “stronghold” regions where one would expect people to care more about their team and their mood to be more heavily influenced by game outcomes, we find no support for the theory's expectations. An alternative explanation may relate to the high salience and regularity of sports matches in Ireland. The regular schedule could enable voters to better identify and attribute the source of their mood compared to contexts where games are more infrequent or considered less important. Counter to typical theoretical expectations, an interpretation of these findings may be that the higher the salience of sports, the more citizens are able to compartmentalize them from other domains of life. Further comparative study is needed to better understand the impact of regularly occurring and important matches on political opinions.

In line with Busby and Druckman (Reference Busby and Druckman2018), an effect of irrelevant events like sports games may only hold when certain conditions are present and, in particular, when voters are not motivated to seek out information beyond mood. In the Irish case, we believe that voters can access relevant political information that provides an alternative guide when casting their ballot or forming political opinions. SI Section J illustrates that Irish voters correctly answer a higher number of factual political questions than respondents from many other countries and are then some of the most politically knowledgeable voters in Europe (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Hobolt, Popa and Teperoglou2016). Given this level of political information at hand, Irish voters may be less likely to rely upon emotional affect and mood when making voting decisions and evaluating political leaders. This explanation is tentative at this point since our design does not enable us to test it directly. We believe that further comparative exploration of the contexts and conditions wherein mood versus substantive knowledge guides political behavior may help unpack the conflicting findings in the irrelevant events literature.

Beyond differential political knowledge, the nature of political campaigning and the relationship between voters and politicians in Ireland may also be important. Due to the small size of the political market and the close links between voters and local politicians linked to the PR-STV system, voters in Ireland often have contact with their local politicians. For example, in 2002, one-fifth of election study respondents contacted their local national representative, and one in ten contacted their local councilor. Contact during campaigns is also critical in Ireland. In the 2002 and 2007 general elections, over 50 percent of respondents reported that a candidate had called to their home to canvass them during the campaign (SI Section K). These levels of door-to-door canvassing are substantially higher than in many other comparable industrialized democracies (Marsh, Reference Marsh2004). The strong linkages and direct contacts between voters and their politicians potentially reduce the impact of mood on their voting decisions. This suggests that the political culture in Ireland and political knowledge may condition the effect of irrelevant events. More precisely, on the one hand, Ireland may be considered a “most likely” case for an impact of irrelevant events as defined by the standards of previous research in this field. On the other hand, Irish voters' higher levels of political information and contact with elected officials may require a change to this “most likely” label. These alternative sources of influence beyond mood are factors not typically discussed in the literature. Yet, political knowledge and the salience of games may affect the impact of irrelevant events, even though prior research would predict such effects would hold in this environment.

Finally, the study underscores the importance of replicating and extending previous findings. The initial positive findings that shark attacks and sports events affect incumbents' vote shares were striking and have been cited widely and received considerable news coverage. One of the best ways to conduct independent tests for potential false positives in observational studies is to extend the analysis to alternative contexts and test whether the same theoretical expectations and estimated effects hold. Our systematic study relying on elections from over nine decades and data from representative surveys do not confirm previous findings. In Ireland, a country with a huge interest in sports, match results do not affect political opinions. Examining the robustness of high-profile findings across different case contexts is key to determining the factors that may condition the impact of irrelevant events.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.52

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan Duggan, Mirya Holman, Martijn Schoonvelde, workshop participants at the University of Zurich, three anonymous reviewers, and the Associate Editor, Rocío Titiunik, for their excellent comments and improvement suggestions. We would also like to thank Gareth Deegan for collecting and publishing results of Irish general and local elections.