Introduction

Career politicians are a prevalent and frequently disdained feature of contemporary democratic politics (Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Cairney, Reference Cairney2007; Cowley, Reference Cowley2012; King, Reference King1981, Reference Goplerud2015; Koop & Bittner, Reference Koop and Bittner2011; Riddell, Reference Riddell1996; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Müller and Saalfeld1997; Shabad & Slomczynski, Reference Shabad and Slomczynski2002; Squire, Reference Squire1993). While researchers of parliamentary professionalization welcome their activism and effectiveness as legislators and representatives (Best & Cotta, Reference Best, Cotta, Best and Cotta2000; Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003; King, Reference King2000; Polsby, Reference Polsby1968; Shabad & Slomczynski, Reference Shabad and Slomczynski2002), other political scientists, as well as many journalists and members of the public, reproach them for a disproportionate pursuit of career protection and progression (Abbott, Reference Abbott2015; Allen, Reference Allen2018; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018; Hardman, Reference Hardman2018; Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018; O'Grady, Reference O'Grady2019; Oborne, Reference Oborne2007; Savoie, Reference Savoie2014; Wright, Reference Wright2013). In this latter vein, career politicians have become a recurring trope in the populist appeals of individuals and parties who, like former US President Donald Trump, France's Marine Le Pen, and Germany's Alternative für Deutschland, claim to be the antidote to a detached and corrupted establishment elite.

Some criticisms of career politicians focus on who they are. As the UK's Nigel Farage put it when attacking Westminster's ‘career political class’:

They all go to the same schools. They all go to Oxford. They all study PPE. They leave at 22 and get a job as a researcher for one of the parties and then become MPs at age 27 or 28… We are run by a bunch of college kids who've never done a day of work in their lives! (Quoted in Goodwin & Milazzo, Reference Goodwin and Milazzo2015, p. 7)

But the most significant criticisms of career politicians – which underpin the disparaging caricatures – focus on their alleged behaviours. Career politicians are said to be active and assertive mainly when it suits their electoral or political prospects, strategic and often successful in the pursuit of high office and liable to make decisions that serve their career goals rather than the long‐term interests of the public or their political parties (see Allen, Reference Allen2018; Allen & Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018; Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015; Hardman, Reference Hardman2018; King, Reference King2015). If career politicians contribute to more effective representation, scrutiny and law‐making, such outcomes are often depreciated as the benign consequences of career‐serving motivations (Allen, Reference Allen2018; Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Cotta & Best, Reference Cotta, Best, Best and Cotta2000; Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003).

While claims about career politicians’ behaviour abound, empirical investigations are few, with patchy and mixed findings. For example, O'Grady (Reference O'Grady2019) finds that career politicians are less likely to rebel in parliamentary votes, Heuwieser (Reference Heuwieser2018) finds them more likely to do so, while Kam (Reference Kam2006) concludes that there is no significant difference in MPs' cross‐voting behaviour. Moreover, existing research has tended to treat career politicians as unidimensional and to rely on single measures to identify them, typically age at entry to parliament (Kam, Reference Kam2006; Kam, Reference Kam2009) or pre‐parliamentary career (Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015; Henn, Reference Henn2018; Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018; Mattozzi & Merlo, Reference Mattozzi and Merlo2008; O'Grady, Reference O'Grady2019). Yet, the concept of ‘the career politician’ has been multi‐dimensional since its inception, embracing a strong commitment to politics as a career, an outsized ambition for office, and limited work and/or life experience of the world beyond politics (King, Reference King1981, Reference King2015; Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, Reference Riddell2011). Being a career politician is also a matter of degree. The use of different and/or narrow measures elides important features of the concept and may explain the incomplete and sometimes contradictory findings in the academic literature.

In this article, we undertake a comprehensive empirical investigation into claims about career politicians’ behaviour, using data from the United Kingdom to test several hypotheses consistent with these claims. We go further than previous research by employing a continuous, multi‐dimensional measure of career politicians, and by examining the separate effects of its four constituent dimensions across multiple areas of parliamentary activity (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020). We accept the need for caution when inferring self‐interested motivations from behaviour, since it is difficult to measure politicians’ motivations directly. Most empirical studies of politicians posit self‐interested motivations like career‐progression (promotion) and career‐protection (re‐election) and then investigate behaviours that would be consistent with them (see, e.g., Fenno, Reference Fenno1978; Mayhew, Reference Mayhew2004; Schlesinger, Reference Schlesinger1966; Shepsle & Weingast, Reference Shepsle and Weingast1994; Strøm, Reference Strøm, Blomgren and Rozenberg2012). We follow the same approach, in our case investigating behaviours consistent with common complaints about self‐interested career politicians. When behaviours are consistent with the posited motivations, that does not mean they are the only motivations involved, but it does make it plausible that they are part of the mix, particularly when other behavioural and qualitative data support this inference.

Our data include full career histories and both behavioural and psychological measures for 521 British MPs, who were first interviewed during the 1970−1974 parliament. This cohort has particular theoretical significance for the career‐politician concept. The 1970 general election was widely reckoned to have introduced the first large generational wave of career politicians in the United kingdom (Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Rush & Cromwell, Reference Rush, Cromwell, Best and Cotta2000), and it was afterwards that King (Reference King1981) first investigated ‘the rise of the career politician in Britain’. Thereafter, commentators investigated their rise, roles and behaviours in other systems (Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Müller and Saalfeld1997; Savoie, Reference Savoie2014; Shabad & Slomczynski, Reference Shabad and Slomczynski2002). Subsequent work attests to the continuing rise of career politicians (Cowley, Reference Cowley2012; Henn, Reference Henn2018). In Britain, the focus of our study, the House of Commons today has more strong career politicians in front‐bench positions in government and opposition (Allen, Reference Allen2013) and more assertive policy advocates on the backbenches (Norton, Reference Norton1997). Recent extraordinary examples of high‐profile politicians furthering their careers rather than the public interest have been attributed to an intensified individualism and diminished respect for norms and rules in the present generation. Whether by selection or by socialization, or both, self‐promoting and self‐protecting dispositions may be inherent in the career politician's role. If they are, then they should be found in the attitudes and behaviours of the first large career‐politician generation which came of age during a less individualistic era.

We report evidence that members of this vanguard, more than their non‐career colleagues: (a) concentrated strategically on activities that served their careers, (b) voted strategically in patterns that safeguarded their careers, (c) attained and retained successfully the high offices they sought and (d) prioritized their personal goals over duties to the parties that supported them. On the methodological side, we show that different unidimensional indicators used by researchers to identify career politicians can produce contradictory results. These findings have important implications for future comparative research.

Theory

Professional politicians were discovered by Reference Weber, Garth and MillsWeber (1919/1946) and re‐named ‘career politicians’ by King (Reference King1981), who identified them on the basis of their commitment to political life as a vocation, their previous occupational backgrounds and their age at entry to parliament. Allen et al.’s (Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020) systematic review of subsequent academic research and public discourse confirms the concept's multi‐dimensional structure. Career politicians are now commonly recognized by one or more of the following four attributes: a strong commitment to politics as a career, a lack of significant occupational experience in the world beyond politics, a lack of significant life experience in the world beyond politics and an outsized ambition for political office. Following Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020), we treat ‘the career politician’ as a family‐resemblance concept (Wittgenstein, Reference Wittgenstein1953) and define a career politician as someone who scores highly on at least one of four dimensions – Strong Commitment, Narrow Occupational Background, Narrow Life Experience and Strong Ambition – which we discuss in more detail below. The strength of the career politician's role orientation is measured by his or her scores across all four.

Underlying the many criticisms career politicians face are assumptions captured in Schlesinger's (Reference Schlesinger1966) theory of political ambition, and in groundwork laid by political scientists like Mayhew (Reference Mayhew2004) and Alt and Shepsle (Reference Alt and Shepsle1990): it is alleged that many, or even most, behaviours they pursue are calculated to advance their electoral success and career progression (see also Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018; Hardman, Reference Hardman2018; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2015; O'Grady, Reference O'Grady2019; Wright, Reference Wright2013). The stronger the career politician, the more likely they are to behave consistent with these theoretical expectations. We investigate such behaviours across four areas and several decades of parliamentary life in the United Kingdom.

Active: Parliamentary questions

In many parliaments, MPs put oral and written questions to the executive. The purpose is to hold governments and ministers accountable and make them aware of constituents’ concerns (Rozenberg & Martin, Reference Rozenberg, Martin, Martin and Rozenberg2012; Müller & Sieberer, Reference Müller, Sieberer, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014). Although the effectiveness of these efforts is not well understood and may be exaggerated (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Martin and Rozenberg2012; Radice et al., Reference Radice, Vallance and Willis1990), individualistic, assertive career politicians who want to be involved in policymaking should nevertheless be eager to participate (King, Reference King1981, pp. 279–280).

In the UK House of Commons, where so much activity is organized around the government–opposition divide, the incentives for career politicians to ask both oral and written questions pull more clearly in one direction on the opposition benches than on the government side. For example, oral questions put directly to ministers on the floor of the Commons provide opportunities for all MPs to attract attention and ‘make a mark’ (Searing, Reference Searing1994). Reported in their local press, oral questions can alert constituents to their MP's activities and please local party activists when they are depicted as ‘harassing the beasts’ opposite (Bailer, Reference Bailer, Martin and Rozenberg2012; King & Sloman, Reference King and Sloman1973; Radice et al.,Reference Radice, Vallance and Willis1990). But because questions are put to ministers, they have limited value for government MPs seeking to advance their careers: harassing your own side is likely to upset local activists, colleagues and the party leadership. In contrast, ambitious career politicians on the opposition benches have stronger incentives to ask oral questions. Doing so will get them attention. It may also win them the approval of colleagues, whips and frontbenchers whose positive judgements will enhance their promotion prospects for opposition front‐bench positions and eventually for ministerial office when their party returns to power (Cowley, Reference Cowley2005).

Career politicians on the opposition benches also have stronger incentives to table written questions. Compared to oral questions, written questions provide opportunities for MPs to extract strategic information from the government, which can then be applied to highlight executive incompetence or improbity. There is obviously little value for government backbenchers in pursuing such activity. Indeed, tabling written questions may distract ministers and impede government business (Hardman, Reference Hardman2018; Rush, Reference Rush2001). Not surprisingly, opposition parties and their backbenchers are more likely to ask written questions than are government MPs (Rozenberg & Martin, Reference Rozenberg, Martin, Martin and Rozenberg2012).

For these reasons, our expectation about the relative activeness of career politicians in asking parliamentary questions focuses on the distinctive and clearer incentive structure associated with being in opposition. Hence:

H1: In opposition, career politicians will ask more parliamentary questions than will non‐career politicians.

Assertive: Cross‐voting

In the House of Commons, cross‐voting, voting against your party's policy, has steadily increased since 1970 when the first large wave of career politicians entered parliament (Cowley, Reference Cowley2005). But are career politicians more likely to be assertive backbenchers? Two opposing hypotheses address this question.

The first of these hypotheses, that career politicians will cross‐vote less when their party is in government, is based on the assumptions that they are exceptionally ambitious for ministerial office, and that embarrassing and potentially endangering their government by cross‐voting will also endanger their careers (O'Grady, Reference O'Grady2019). A few rebellions are acceptable, but a few too many impede promotion prospects (Cowley, Reference Cowley2005). Thus, the stereotype is that career politicians are self‐interested yes‐men and ‐women who will not stick their necks out in the division lobbies (Hardman, Reference Hardman2018). Furthermore, their lack of pre‐parliamentary occupational experience shrinks their prospects for exiting into alternative careers with comparable status and salaries. Gaines and Garrett's (Reference Gaines and Garrett1993) analyses support this prediction as do those of Benedetto and Hix (Reference Benedetto and Hix2007).

The second hypothesis relating to cross‐voting arises from King's (Reference King1981) and Riddell's (Reference Riddell1996) well‐informed observations that career politicians are more assertive because they are more interested in influencing policy, particularly when their party is in government. They cannot themselves make policy but they can prod and constrain ministers’ policymaking. Their principal weapon is the threat of rebellion (Cowley, Reference Cowley2005). Fortified with subject specializations and an element of individualism, they are not prepared to accept passive backbench careers (Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Rush & Cromwell, Reference Rush, Cromwell, Best and Cotta2000). They did not come to the House to be ‘lobby fodder’ but rather to influence events. Finding less opportunity to influence events than they would like, they develop an ‘itch to rebel’. Heuweiser's (Reference Heuwieser2018) findings support this prediction, while Franklin et al.’s (Reference Franklin, Baxter and Jordan1986) and Kam's (Reference Kam2006) do not.

What is consistent across these two inconsistent theoretical streams of research is the expectation that career politicians vote differently from non‐career politicians. But because authoritative observations, quantitative findings and measures of key variables are so mixed, we keep both hypotheses in play:

H2a: In government, career politicians will cross‐vote less than will non‐career politicians.

H2b: In government, career politicians will cross‐vote more than will non‐career politicians.

Anointed: Attaining and retaining office

Career politicians are criticized for craving power and status, for outsized ambition, and for political hyperactivism at the expense of diligent governance and the common good (Allen, Reference Allen2018; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018; Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy1995; King, Reference King2015). But are they any more likely than non‐career politicians to attain and retain positions of power?Footnote 1

In the United Kingdom, the opportunities for career politicians wanting ministerial office appear promising because there are many government posts and many MPs are not serious competitors for them (Allen, Reference Allen2013). Yet, the strength of desire for office is clearly not the only factor involved. For a start, whether a party is in government or opposition will determine when its MPs are eligible for ministerial office. Moreover, ministerial selection criteria are often opaque. Much depends on the preferences and calculations of prime ministers who generally enjoy considerable discretion (King & Allen, Reference King and Allen2010). A new prime minister can commence or curtail an MP's spell on the front benches. Nevertheless, there is considerable evidence that ambition matters. Career politicians, particularly those who worked in politics before entering parliament, are more likely than non‐career politicians to attain both government and opposition front‐bench positions (Allen, Reference Allen2013; Allen & Cairney, Reference Allen and Cairney2017; Cowley, Reference Cowley2012; Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015).

We investigate, first, whether career politicians in the House of Commons are more likely to be promoted to government front‐bench positions. We assume that success in attaining such positions is evidence of a strong desire for office, in most cases a necessary though not sufficient factor for promotion (Schlesinger, Reference Schlesinger1966).

We then investigate the proportion of time that MPs retain government positions. Many of the criticisms of career politicians focus on their governing performance. As ministers, they supposedly innovate when no innovation is needed, push for ill‐advised, quick results, either to make their mark and build their careers (Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy1995) or because of an ideological desire to change the world (King, Reference King2015). They tend to take short‐term perspectives and neglect underlying problems because such problems take longer to resolve than the time ministers are likely to remain in their present posts, and hence are unlikely to enhance their current reputations (Hardman, Reference Hardman2018; King & Crewe, Reference King and Crewe2014). Moreover, a number of politicians and commentators have suggested that broader professional and life experience can help develop the skills necessary to lead a government department. In the words of one former minister, ‘What trains you to be a minister is having done something outside politics first’ (cited in Riddell, Reference Riddell2019, p. 44).

In short, from this viewpoint, some career politicians make worse ministers. We assume that the total length of service measures ministerial success, so long as it takes account of the time that MPs are eligible for office (Berlinski et al., Reference Berlinski, Dewan and Dowding2007). Ministers’ performances are engrossing topics of discussion at Westminster. They are keenly watched and constantly judged by superiors and colleagues, and failing performers are usually shuffled out. We expect that even if career politicians are more successful at attaining government front‐bench positions, they should not last as long in them.

H3a: Career politicians will be more successful than non‐career politicians in attaining government front‐bench positions.

H3b: Career politicians will be less successful in retaining government front‐bench positions.

Absconded: Party defection

In the United Kingdom's well‐established party system, changing parties can be risky because even if defectors win re‐election once, in the long run defections usually destroy political careers (Leach, Reference Leach1995; Thompson, Reference Thompson2020). When MPs defect, it is typically for strategic reasons and only after very careful consideration (Mershon, Reference Mershon, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014). Few actually do so. What career‐oriented considerations might persuade MPs to risk their careers? Most explanations identify three self‐focused motivations: re‐election, promotion and ideology (Leach, Reference Leach1995; Mershon, Reference Mershon, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014; O'Brien & Shomer, Reference O'Brien and Shomer2013).

Compared to non‐career politicians, career politicians are allegedly more ideological, ambitious, individualistic, assertive, proud and wilful (Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018; Kam, Reference Kam2006; King, Reference King1981; Reference King2015; Riddell, Reference Riddell1996, Reference Riddell2011). Working in an ideologically congenial party is especially important for career politicians because individualism predisposes such MPs to value their personal integrity more than their role integrity (Cowley, Reference Cowley2005). The desire to stick to their principles trumps their sense of duty to support their party. At the same time, their desire for office is also very strong: they are in politics to attain and exercise power. Hence, career politicians would be less likely to stick with their party when it rejects their deeply held political values, less prepared to wait to see whether their party's ideological pendulum will swing back, more likely to worry that if and when it swings back it may be too late for their leadership aspirations.Footnote 2

Our data set enables us to investigate these claims by focusing on the 1981 defections from the Labour Party to the short‐lived Social Democratic Party (SDP), the largest breakaway from a major party in British politics since 1886. Most typical about this mass defection was its very strong ideological motivation (Leach, Reference Leach1995; Mershon, Reference Mershon, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014). The SDP was formed primarily by those on the right of the Labour Party who had become discomfited by its leftwards move (Crewe & King, Reference Crewe and King1995, p. 121). Most unusual about the mass defection was that the defectors were creating a new political party that, at the time, was genuinely seen as having the potential to break the mould of British politics. The SDP aspired to supplant Labour on the centre‐left and, perhaps in coalition with the Liberals, form a government where the defectors might fulfil both their political values and their ambitions for office (Leach, Reference Leach1995). This conjunction of ideology and ambition leads to a final hypothesis:

H4: Career politicians will be more likely than non‐career politicians to defect from Labour to the SDP.

Data and analysis

For the present analysis, we follow King (Reference King1981, pp. 269–276) in treating the career‐politician concept as a matter of degree rather than kind. We also follow Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020) in treating its multi‐dimensional structure in line with Wittgenstein's (Reference Wittgenstein1953) account of family‐resemblance concepts. A focus on single dimensions or on different combinations of dimensions may be sufficient to recognize whether politician A is a member of the career‐politician conceptual family. Mere classification, however, is not enough for causal claims and correlational analyses, for here it is necessary to measure how much of a career politician A is along each dimension and overall.

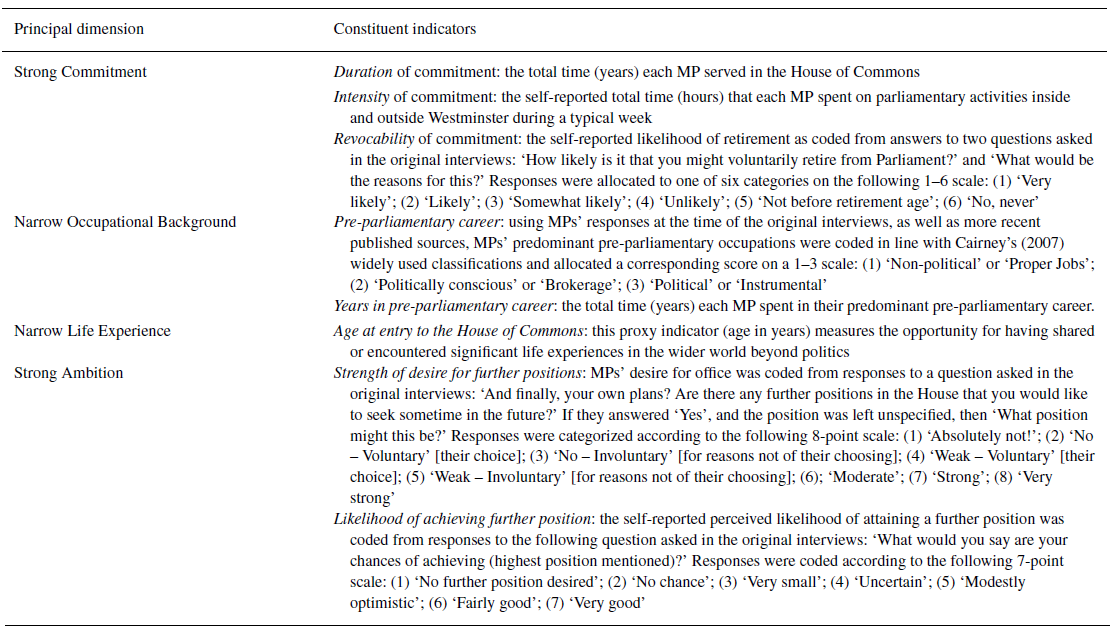

We approach this task by utilizing Allen et al.’s (Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020) measures of the four dimensions of the career‐politician concept: Strong Commitment, Narrow Occupational Background, Narrow Life Experience and Strong Ambition. Each dimension was operationalized with data derived from transcribed interviews conducted by Searing (Reference Searing1994) and his associates with 521 MPs during the 1970−1974 parliament, supplemented with additional information about their pre‐parliamentary and parliamentary careers.Footnote 3 A key strength of these data, as noted, is that they cover the 1970 intake to the House of Commons, which is regarded as having introduced the first large wave of career politicians to Westminster. It also includes many ‘amateurs’, ‘part‐timers’ and other non‐career politicians, thereby facilitating comparisons with the newly arrived generation of career politicians.

The first dimension, Strong Commitment, reflects the idea that career politicians are committed to politics as a full‐time, life‐time vocation (King, Reference King1981; Riddell, Reference Riddell1996). The second dimension, Narrow Occupational Background, corresponds to claims that career politicians lack practical, common‐sense, experiential knowledge about ‘real jobs’ because they have worked mostly in political occupations (Riddell, Reference Riddell1996). The third dimension, Narrow Life Experience, reflects claims that career politicians are out of touch with the real world and lack familiarity with many citizens’ social and personal life experiences (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018; King, Reference King2015; Wright, Reference Wright2013). Strong Ambition, the fourth dimension, accords with career politicians’ purported strength of desire for power and fame (Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015; King, Reference King1981).

Each of the dimensions is measured by standardizing and adding together a number of constituent indicators as summarized in Table 1.Footnote 4 The rationale and frequency distribution for each indicator are discussed at length in Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020, pp. 203–209). Once the standardized indicators have been added together, the resulting score is itself then standardized to create a measure of each politician's deviation from the mean for each dimension. Validity tests indicated that any one of the dimensional measures is sufficient to identify members of the career‐politician conceptual family (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020, pp. 212–214). Descriptive statistics for the dimensions are reported in Online Appendix B.

Table 1. The dimensions of the career‐politician concept and their constituent indicators.

Note: A higher score for each indicator is generally associated with being more of a ‘career politician’ on the relevant dimension. The exception is age at entry to the House of Commons, where being a young first‐time MP is associated with being a career politician.

Our principal independent variable is a composite ‘Career Politician index' that enables us to investigate which empirical claims about career politicians might be generalizable to the role (see Online Appendix A for more details about how we construct the index). This composite index is constructed from the individual maximum values among the measures of all four dimensions, a special scoring procedure that departs from Allen et al.’s (Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020) operationalization but better captures component substitutability, the key characteristic of family‐resemblance concepts (Goertz, Reference Goertz2006, p. 45; see also Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen2020). In composite measures of family‐resemblance concepts, cases should be recognized as valid examples of the construct based on high scores on one dimension, even when they may score little or nothing on other dimensions. Examples of recent career politicians who might be recognized by this procedure include the strongly ambitious David Cameron and George Osborne who, nevertheless, demonstrated weak commitment to politics as a life‐long vocation by voluntarily leaving parliament in mid‐life after losing government office in order to pursue alternative careers. Our composite index is treated as a formative latent variable (Coltman et al., Reference Coltman, Devinney, Midgley and Venaik2008) that is jointly constituted and caused by the confluence of its four dimensions, all of which are necessary to the summary variable they comprise.Footnote 5

Since it is possible that the four different dimensions of the career‐politician concept may have different relationships with dependent variables – a potential problem when researchers rely on single variables – we also use the dimensional measures as independent variables in separate analyses. Doing so could create problems of multi‐collinearity, however, because some overlap among the four measures is difficult to avoid, just as the career‐politician concept's dimensions overlap in academic and political discourses. Cross‐correlations among the dimensional indicators and variance‐inflation‐factor (VIF) statistics for each of our multi‐variate regression models, however, indicate our results are unaffected by collinearity issues (see Online Appendices B and D, respectively).Footnote 6

For the present analyses, we added to Allen et al.’s (Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020) data set, longitudinal dependent variables measuring various parliamentary activities, cross‐voting, promotions to front‐bench positions, time in these positions, retirements, the circumstances of those retirements and party defections. We describe these measures in greater detail in the Results section below, while descriptive statistics are reported in Online Appendix B. Because of potential confounding factors, we introduce a number of control variables that are often deployed in analyses of career politicians or otherwise noted as important factors in their behaviour: margin of victory (the difference between an MP's share of their total constituency vote and that of their closest rival); length of tenure at the time of the interview (years of service in the House of Commons)Footnote 7; ideology (left‐right reputation within each party); rank (member of government or opposition front‐bench spokesman, including whips, vs. backbencher) as well as the size of the governing majority in our cross‐voting models.

Results

The different properties of our dependent variables require us to employ several types of regression analysis to test our hypotheses. We use negative binomial regressions to accommodate the count‐data nature of parliamentary questions and cross‐voting, binomial and quasi‐binomial regressions for our analysis of attaining and retaining front‐bench positions, and binomial regressions to suit the binary nature of party defections. As a robustness check, we re‐ran all our negative binomial models using ordinary least squares (OLS) and quasi‐Poisson regressions, obtaining very similar results.

Since it makes little sense to interpret coefficient sizes in non‐linear regression models, we present a set of predicted count, fraction and probability plots. Our plotted estimates reflect observed covariate values across the range of the career‐politician index and dimensions. We overlay these predictions with simulated 95 per cent confidence intervals (simulation n = 10,000) to visualize the uncertainty surrounding our estimates. Detailed regression results are reported in Online Appendix C.

Active: Parliamentary questions

H1: In opposition, career politicians will ask more parliamentary questions than will non‐career politicians.

The data we use to test this hypothesis come from the 1970−1974 parliament when Labour was in opposition. To control for party‐ and parliament‐specific effects, we include a dummy coded 1 for Conservative MPs. The numbers of oral and written questions asked by MPs were obtained from The Political Companion, a quarterly compendium of parliamentary and political data edited by F. W. S. Craig. As noted, we focus on opposition MPs because those on the government benches were typically less active to avoid impeding government business. More generally, oral questions are particularly attractive to career politicians when in opposition for they offer opportunities to gain attention and showcase rhetorical skills, thereby enhancing MPs’ promotion prospects. Written questions can also advance their career interests by extracting information from ministers that can be used for the same purposes.Footnote 8

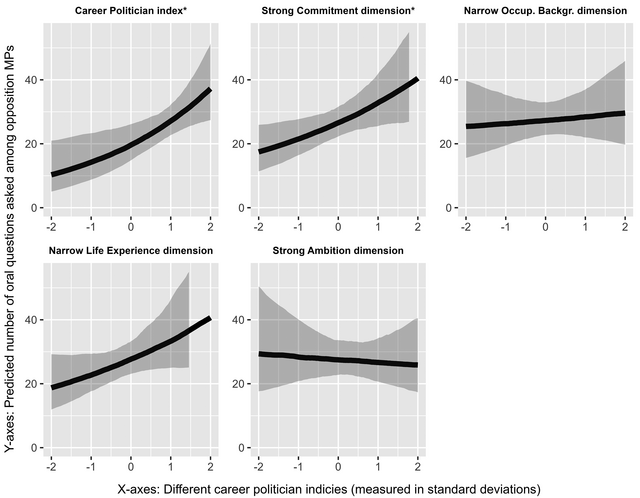

Figure 1 visualizes our findings for oral questions (the corresponding regression output is reported in Online Appendix Table C.1). In support of hypothesis H1 we find a consistent, statistically significant effect for the composite index (the top‐left panel in Figure 1). Opposition career politicians are far more active than their non‐career politician colleagues in putting oral questions to ministers. The MP achieving the lowest score on the composite index posed approximately ten questions, which climbed to almost 40 for the Labour MP in our sample who scored highest on the index. Since parliamentary questions serve so many different goals and interests (Rozenberg et al., Reference Rozenberg, Chopin, Hoeffler, Irondell, Joana, Martin and Rozenberg2012), differences between career politicians and others in their propensity to table them might be small. However, even for our first‐generation UK career politicians, the differences are very substantial.

Figure 1. Predicted count of oral questions posed by Labour MPs, 1970–1974.

Note: Predictions based on negative binomial regression models. Panels marked * feature a statistically significant effect, p < 0.05.

Figure 1 also shows the statistically significant relationship between Strong Commitment and MPs’ propensity to ask oral questions.Footnote 9 However, the isolated effect of commitment is far less pronounced compared with the composite index. The other three dimensions suggest null results. Substantially, these findings draw attention to emergent properties inherent in family‐resemblance concepts: effects may be driven not by a career politician's strength of commitment, occupational background, life experience or strength of ambition by themselves, but rather by qualities that emerge at the intersection of these characteristics. As a family‐resemblance measure, the composite index can reveal empirical regularities that would be missed by analyses based on individual dimensions alone.

Our results for written parliamentary questions, reported in Online Appendix Table C.2, reveal markedly similar effects to those obtained for oral questions. The composite index again shows a statistically significant and substantially important impact on the total number of written questions that opposition MPs posed. Given these results, we investigate if career politicians strategically prioritize their visibility by asking more oral questions than would be expected by the number of written questions they tabled. Written questions involve more research and preparation but provide fewer benefits in terms of immediate visibility. Results reported in Online Appendix Table C.3 confirm that career politicians prefer preforming in the House of Commons Chamber.

A further obvious follow‐up question is whether career politicians’ greater activity in the field of asking questions is reflected in other areas of parliamentary life. Positive views of career politicians claim they work harder and devote more time than non‐career politicians to constituency representation and to scrutinizing legislation and policy (King, Reference King1981; Riddell, Reference Riddell1996). We found no significant relationships between the composite index and the time MPs spent in their constituencies or their attendance of select committees.Footnote 10 The contrast between these results for diligent work in the trenches and those for the public drama of asking oral questions is consistent with claims that career politicians are most energetic in activities that can directly benefit progression in their careers.

Assertive: Cross‐voting

H2a: In government, career politicians will cross‐vote less than will non‐career politicians.

H2b: In government, career politicians will cross‐vote more than will non‐career politicians.

The first of our hypotheses relating to cross‐voting, consistent with O'Grady's (Reference O'Grady2019) analysis, is the allegation that career politicians cross‐vote less because they are more ambitious for ministerial office and, having little pre‐parliamentary occupational experience, are poorly qualified for alternative careers. Both considerations are said to motivate them to get along by going along. The second hypothesis, supported by Heuwieser's (Reference Heuwieser2018) research, predicts that career politicians cross‐vote more because they are more assertive and want to be involved in the policy process. Moreover, many of them may not be so ambitious for ministerial office: some may have given up hope; others will have been sacked (Benedetto & Hix, Reference Benedetto and Hix2007).

We examine cross‐voting in four consecutive parliaments: the 1970−1974 Conservative government, the 1974 and 1974−1979 Labour governments and the Conservative government of 1979−1983. The data come from Norton (Reference Norton1975, Reference Norton1980, Reference Norton1998).Footnote 11 Since cross‐voting can be more consequential and therefore more dangerous for the careers of MPs whose party is in government, we focus on government MPs and pool our observations across all four parliaments, including only those members who were actually elected to the respective parliaments during our period of observation (1970–1983).Footnote 12 Our models are specified mixed‐effects negative binomial regressions with MP's cross‐vote count as the dependent variable.

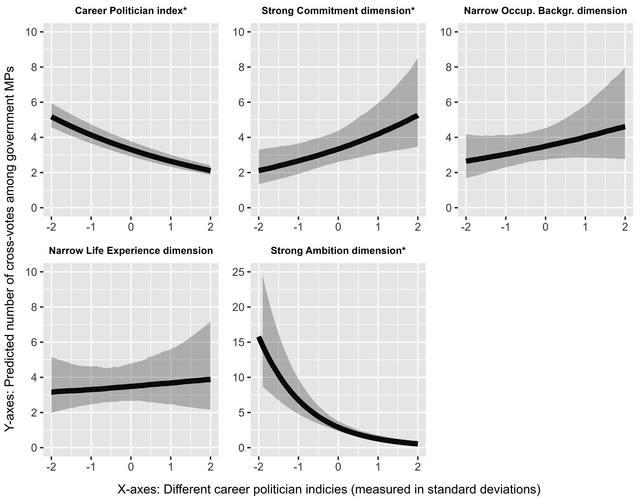

As shown in the top‐left panel of Figure 2, we find a statistically significant, negative relationship between our composite index and cross‐voting behaviour, lending support to hypothesis H2a (the full results are reported in Online Appendix Table C.6). Our model predicts the least typical career politician in our sample to have cross‐voted on more than 12 occasions. The most typical career politician, by contrast, broke ranks little more than twice during the same period of observation.

Figure 2. Predicted total count of cross‐votes by government MPs, 1970–1983.

Note: Predictions based on hierarchical negative binomial regressions. Panels marked * feature a statistically significant effect, p < 0.05.

Our key finding here, however, concerns the relationships between different dimensions and MPs’ propensity to rebel. Strong Ambition has an even more powerful negative effect on cross‐voting than the composite index. Career politicians who are keen to achieve ministerial positions are far less likely to cross‐vote than are their less ambitious colleagues. The most ambitious career politicians cross‐voted no more than once during the entire time that their parties were in government, whereas their least ambitious colleagues cross‐voted more than 15 times during the same period.Footnote 13

Strong Commitment, by contrast, is positively associated with cross‐voting when the career politician's party is in government, which is consistent with the expectation underpinning hypothesis H2b. Strongly committed career politicians are more assertive and politically involved in the policy process, and they cross‐vote, or implicitly threaten to do so, in order to influence legislation. Being a very active policy advocate is one parliamentary career track for career politicians, suggesting that there may be different types of career politicians. The most committed MPs in our sample cross‐voted about five times compared to the least committed individuals who cross‐voted no more than twice.

Both political ambition and commitment are central to the concept of a career politician. But if we had focused on only one of these dimensions, our choice of focus would have altered our conclusions. For instance, if we had measured career politicians by the strength of their ambition, we would have concluded that, in government, career politicians cross‐vote much less than non‐career politicians. If we had measured career politicians by the strength of their commitment, we would have concluded the opposite: that, in government, career politicians cross‐vote more than non‐career politicians. There appears to be some truth in both hypotheses, but perhaps different truths for different types of career politicians. Those who are relatively less ambitious but strongly committed to the career for the long haul may indeed fit the assertive, policy‐oriented, executive‐checking characterizations behind King's (Reference King1981), Riddell's (Reference Riddell1996) and Heuwieser's (Reference Heuwieser2018) expectations for strategic dissent. Jeremy Corbyn, the former Labour leader, is a recent example of such a politician: a serial rebel until 2015, he stood as the ‘token leftie’ in that year's leadership contest and unexpectedly won. But career politicians with much stronger ambitions for office may subdue their ‘itch to rebel’ and follow their career prospects into the division lobbies. Any model that includes only one dimension may miss what is really going on.

Anointed: Attaining and retaining office

H3a: Career politicians will be more successful than non‐career politicians in attaining government front‐bench positions.

H3b: Career politicians will be less successful in retaining government front‐bench positions.

The first of our hypotheses, which focuses on the attainment of government front‐bench positions, is based on findings from studies using a variety of different measures of career politicians (Allen, Reference Allen2013; Cowley, Reference Cowley2012; Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015; King, Reference King1981; Riddell, Reference Riddell2011). Many appointees who are career politicians will have had what Schlesinger (Reference Schlesinger1966) characterized as ‘progressive ambition’ – they wanted higher office and worked hard at getting it. The second hypothesis, which focuses on the retention of government positions, assumes further that strong career politicians may also be poor at governing, partly because their ambition encourages short‐termism and partly because they entered parliament too soon and with too little wider experience (King & Crewe, Reference King and Crewe2014).

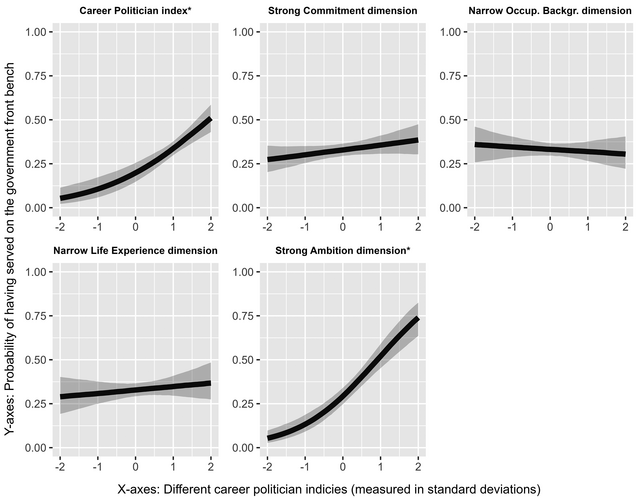

To test H3a, we ran a set of binary outcome regression models that predict if individual MPs were promoted to the government front bench (coded 1) or not (coded 0) after they were interviewed that is, from 1970.Footnote 14 To test H3b, we ran a set of quasi‐binomial regression models using as our outcome measure the cumulative time MPs held government front‐bench positions as a proportion of the time they were theoretically eligible for such positions.Footnote 15 Our outcome variable for the latter is hence a simple ratio of the time (in days) that an MP served in such positions from 1970 and the total time (in days) they were members of the House of Commons when their party was in government after the same date.Footnote 16 The data are drawn from a wide variety of published sources, including Stenton and Lees (Reference Stenton and Lees1981), Butler and Butler (Reference Butler and Butler2000), various editions of Dod's Parliamentary Companion and the UK Parliament website. Along with our set of control variables, we included a party membership dummy to account for cross‐party differences in the total time MPs were eligible for leadership posts.Footnote 17 Figure 3 shows the predicted outcome plots for attaining office, while Figure 4 visualizes the results for retaining office.Footnote 18 Point estimates for each regression can be found in Online Appendix Tables C.7 and C.8.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of being promoted to the government front bench.

Note: Predictions based on logistic regression models. Panels marked * feature a statistically significant effect, p < 0.05.

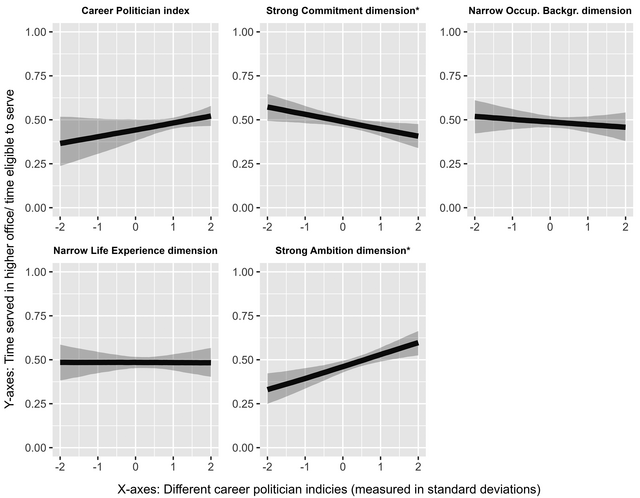

Figure 4. Predicted share of eligible time spent on government front bench.

Note: Predictions based on quasi‐binomial regression models. Panels marked * feature a statistically significant effect, p < 0.05.

Figure 3 demonstrates the exceptionally strong association between the composite index and chances for promotion to the government front bench. This finding supports hypothesis H3a. Our model predicts it to be almost impossible for MPs with the lowest scores on this index to be promoted (below a 5 per cent chance), whereas promotion becomes far more likely at the top end of the scale (a higher than 50 per cent probability). While evidence about career politicians being exceptionally successful at securing promotion is familiar, we were surprised by how strong this relationship appears in our data. The composite result seems driven mainly by the Strong Ambition dimension, our single most powerful predictor. The remaining dimensions do not explain any additional variance. The limited importance of Narrow Occupational Background is particularly surprising given the significance of pre‐parliamentary occupation in other studies of MPs’ promotion prospects (Allen, Reference Allen2013; Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015). More importantly, and mirroring our analysis of cross‐voting behaviour, these results draw attention to the risk of misattributing relationships between one‐dimensional measures of career politicians and ministerial promotion.

Figure 4 depicts results for the position‐retention models.Footnote 19 Contrary to hypothesis H3b, the career politician index has no effect on the proportion of time spent on the government front benches. There are, however, two important effects among the dimensional measures. Whereas Strong Commitment is negatively associated with retaining an office, Strong Ambition is positively related to retaining it. Prime ministers apparently do not find these highly ambitious career politicians to be as disappointing as full‐blooded critics suggest. Effect sizes are noteworthy in both cases: our model predicts that a one standard‐deviation increase in the ambition dimension produces a 10 per cent increase in the proportion of time spent on the government front bench during an MP's career, whereas the commitment dimension has the opposite effect.

As with our analysis of cross‐voting, the divergent effects of these two dimensions on front‐bench retention hint at the existence of different types of career politicians. Just as the most ambitious MPs seem reluctant to vote against their party line when it is in government, so they appear to prosper in office, perhaps because, when necessary, they continue to trim their ideological sails to the wind. Similarly, just as the greater assertiveness and ideological resolve of the most strongly committed career politicians may make them more likely to rebel, as seen, so it may also shorten their tenure on the front benches. They may find it more difficult to get along by going along.

Further insight into the possibility that prime ministers find it harder to accommodate the most committed career politicians can be gleaned from the circumstances of their final departure from ministerial office. We coded a dummy variable as one when ministers were dismissed by the prime minister and zero for any other circumstances (for instance, death, loss of election, voluntary retirement and resignation on policy grounds). Following King and Allen (Reference King and Allen2010), these data were drawn from memoirs, biographies, other secondary accounts, entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (n.d.) and contemporary press reports. The results, summarized in Online Appendix Table C.10, show that strongly committed career‐politician ministers are in fact far more likely than their strongly ambitious career‐politician colleagues to be sacked by the prime minister, a probability that rises from a mere 10 per cent for the least committed to an impressive 50 per cent for the most strongly committed.

Absconded: Party defection

H4: Career politicians will be more likely than non‐career politicians to defect from Labour to the SDP.

Changing parties in the United Kingdom is rare because it usually destroys political careers. In most situations when MPs find themselves in principled disagreement with their party, defection is not a practical option. The pull of wanting to secure re‐election and/or attain leadership positions will generally exceed any ideological push. Yet, circumstances may greatly alter the balance of such considerations, as occurred when the SDP was launched in 1981. The SDP seemed at the time a viable political vehicle and created a rare opportunity for many Labour MPs unhappy with their party's direction of travel to consider defection. It offered a chance for them to fulfil both their ideological and career ambitions.

To test hypothesis H4, that career politicians on the Labour benches were more likely to defect to the SDP than non‐career politicians, we first distinguished between Labour MPs who defected to the SDP (coded 1) and Labour MPs who did not (coded 0).Footnote 20 The codes were based on information drawn from Crewe and King (Reference Crewe and King1995). We then used logistic regression models to analyse the resulting binary variable (see Online Appendix Table C.11).Footnote 21

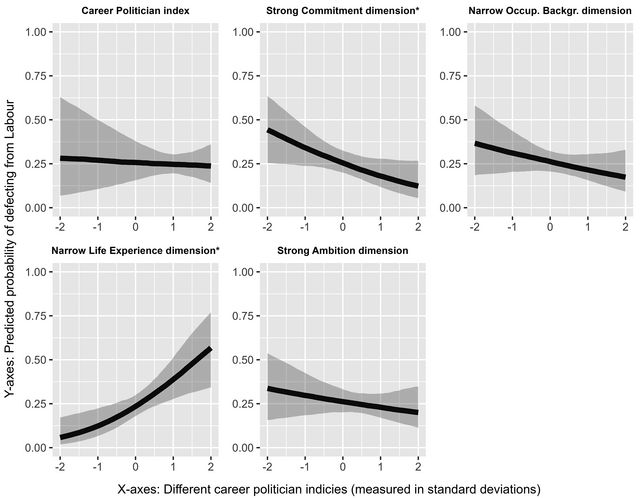

Figure 5 reports the predicted outcome plots based on our model estimates. Contrary to H4, the career politician index does not predict defections, nor does Strong Ambition, the dimension most theoretically relevant to the hypothesis. Some of the more ambitious MPs chose to defect but others chose to remain. Most ambitious remainers probably reckoned their prospects were best served by staying put, but it is also possible that some ideologically sympathetic and personally ambitious Labour MPs rejected the SDP precisely because they feared being overshadowed by its high‐profile leaders.

Figure 5. Predicted probability of defection from Labour to the SDP, 1981−1983.

Note: Predictions based on logistic regression models. Panels marked * feature a statistically significant effect, p < 0.05. Career Politician and Strong Commitment were modelled without the ‘number of years served in the House of Commons’ component (see endnote 18 for details).

Two of the other dimensions do predict the defections, albeit in different directions. Narrow Life Experience has a strong positive relationship with the decision to defect. This dimension captures the politicians who started their careers early, often motivated by strong principles, determined to attain office and put their social democratic principles into policies. Yet now their party was adopting policies they could not and would not defend. They resolved this conflict by joining a new social democratic vehicle consistent with their career ambitions.

The most interesting finding from our analysis is the negative effect of Strong Commitment. This finding is consistent with the claim that many defectors’ roots in the Parliamentary Labour Party were not as deep as those of colleagues who remained behind. Despite several notable high‐profile exceptions, such as Shirley Williams and Bill Rogers, those who left for the SDP were less committed to life‐long careers as Labour MPs. These relationships are particularly impressive because they stand out even after we have controlled for ideology (see Online Appendix Table C.11), the most powerful factor driving the defections (Crewe & King, Reference Crewe and King1995). The defecting career politicians were individualists moved more by personal integrity than party identity.

Discussion

Advocates of parliamentary professionalization believe career politicians are remarkably active and effective in representing constituents and designing and scrutinizing legislation. Critics believe they are self‐serving and so eager to advance their own careers that they short‐change the interests of their constituents and the wider public. Using continuous measures that reflect the role's multi‐dimensional character, and drawing on rich historical data covering parliamentary careers and behaviour in the British House of Commons, we investigated four hypotheses expressing such claims.

Across four important modes of parliamentary behaviour, we find evidence consistent with claims that, compared to non‐career politicians, this first generation of career politicians, especially the highly ambitious career politicians, were more likely to act strategically to advance their own careers. Like political value systems, identities as career politicians may crystallize early on in political careers and become quite enduring (Cobb‐Clark & Schurer, Reference Cobb‐Clark and Schurer2012; Costa & McCrae, Reference Costa and McCrae1988; Searing et al., Reference Searing, Jacoby and Tyner2019). Our measures of the career‐politician concept and its dimensions successfully predict behaviours across decades.

We find that career politicians, as measured by our composite index, spend more time than non‐career politicians tabling oral and written parliamentary questions, activities that can showcase their talents and advance their careers, but they do not spend any more time on constituency work or attending select committees, activities with less obvious career benefits. In the same vein, we also show that career politicians prioritize performing in the Chamber over tabling written questions. We find that career politicians vote strategically in patterns that safeguard their career progression by following the party line more often when their party is in government, and that they are more successful than non‐career politicians in attaining government office.

In addition, our analyses of the four dimensions that define career politicians show what attributes of the role lead to criticized behaviours and further demonstrate that different attributes have sometimes divergent effects on behaviour. Strength of commitment causes politicians to spend more time tabling questions, whereas ambition greatly increases MPs’ likelihood of being made ministers. Moreover, commitment and ambition pull in different directions when it comes to cross‐voting and retaining ministerial office: the strongly committed seem more likely to try to influence policy by being more rebellious and somewhat less ready to get along in government by going along; the highly ambitious seem less likely to jeopardize their careers by signalling dissent and better prepared to succeed or adapt in office. Finally, we find that early‐entry career politicians, and those least committed to life‐long careers in their present parliamentary parties, are more likely to abandon them when they believe there are viable alternatives that better suit their career interests.

Taken together, our findings not only test common claims about career politicians but also have broader implications for our understanding of the role and for future research. Firstly, our analysis highlights the pitfalls in focusing exclusively on single attributes of the career‐politician concept. A strong commitment to politics as a career, a narrowly political occupational background, a lack of significant life experience beyond politics and strong ambition for office are all central to it (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020). Yet, due to the paucity of readily available data, researchers have tended to focus on one of these dimensions in isolation and to operationalize it using single measures, usually either MPs’ pre‐parliamentary occupation or their age at entry to the House of Commons. The comparative robustness of these two common single measures is investigated in the last two columns of the tables in Online Appendix C. Age at entry displays the ‘correct solution’ in terms of what the career politician index suggests everywhere but for prioritizing oral questions over written questions, cross‐voting and party defections. The occupation variable behaves more randomly. In the case of cross‐voting, age at entry and pre‐parliamentary occupation produce contradictory findings, which might explain why the empirical literature contains such opposite predictions (Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018; O'Grady, Reference O'Grady2019). Thus, age of entry is perhaps a better proxy for being a career politician than occupational background, at least among the first generation of British career politicians. Of course, pre‐parliamentary career structures have evolved since, with increasing numbers of MPs now hailing from political backgrounds, which might make occupational background a better indicator today.

Secondly, while we have focused primarily on claims made about career politicians tout court, our analysis suggests that there may in fact be different types of career politician, a point made in King's (Reference King1981, p. 283) seminal study. We treat the career politician as a single conceptual family, but as in any real‐life family, different members of it may well tend to pursue different behaviours.Footnote 22 The findings we report show that the sharpest differences in behaviour among career politicians often lie at the intersection of two dimensions: commitment to politics as a career and ambition for high office. Both motivations are central to the concept, and further research into career politicians needs to engage both. Such research might also shed further light on the different types of career politicians and usefully challenge some of the blanket criticisms made about them.

It is perhaps not so surprising that different dimensions sometimes pull in different directions on the same dependent variables, as they do with cross‐voting, retaining positions and party defections. Nor, upon reflection, is it so surprising that when single dimensions are used to operationalize multi‐dimensional family‐resemblance concepts, they can produce conflicting findings (Barrenechea & Castillo, Reference Barrenechea and Castillo2019). The great advantage of employing a family‐resemblance framework to analyse multi‐dimensional concepts like ‘career politician’ is that it protects their political relevance by keeping them close to their usage in political life. The disadvantage is that the approach can build heterogeneous concepts and measures, which can complicate consistent prediction and theoretical interpretation. The appropriate balance between political relevance and precision is debated by political scientists and philosophers of social science (Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2005; Stoker et al., Reference Stoker, Peters and Pierre2015). In practical terms, one might draw different conclusions in different cases. Obviously, in the present case, we give political relevance substantial weight.

A third and more general implication is the need for caution when assuming career politicians’ motivations. In legislative studies, motivations are often introduced as unmeasured assumptions about prioritizing self‐interest because of the difficulties in measuring them directly (Blomgren & Rozenberg, Reference Blomgren, Rozenberg, Blomgren and Rozenberg2012). However overemphasizing naked self‐interest and ignoring the complexity of motives feed negative stereotypes of politicians and can fuel unwarranted contempt (Borchert, Reference Borchert, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Wright, Reference Wright2013). Behaviours motivated by self‐focused career strategies can simultaneously be motivated by public‐service orientations. For example, energetic participation in parliamentary questions can advance an MP's career prospects but can also advance the constitutional function of checking the executive. Party defection can be motivated by self‐protecting re‐election or promotion goals but can also be motivated by desires to advance policies that an MP believes will best serve the nation. Institutional design can help channel self‐interested motives into intended or unintended constitutionally desirable conduct. Strong career politicians may be motivated by yearnings for influence, fame or power, but most are also motivated by wishes to improve policies or institutions. Nonetheless, compared to non‐career politicians, they seem inclined to place relatively more weight on the former.

A final implication is that political scientists should try, where possible, to range beyond unidimensional measures when analysing this multi‐dimensional concept. Across the dimensional dependent variables examined here, Narrow Life Experience, Strong Commitment and Strong Ambition are the most emphatic and wide‐ranging predictors of behaviour. Narrow Occupational Background, which corresponds to the most frequently used measure of career politicians, performs less well. Strength of commitment, the concept's primary characteristic for Reference Weber, Garth and MillsWeber (1919/1946) and King (Reference King1981), is a much stronger link in the chain. The relative availability of data may well have played a role in shifting the concept's centre of gravity from politicians' strength of commitment to occupational and life experience, and it will continue to play a role in how the concept is analysed. Although there are obvious challenges in collecting relevant data, especially for the commitment and ambition dimensions, Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Magni, Searing and Warncke2020, p. 214) suggest several potential indicators suitable for comparative research. On that note, we might expect that future research will be more likely to replicate our overall finding, that career politicians are more self‐serving than non‐career politicians, than the relationships we observe between the individual dimensions and our dependent variables.

In this article, we have analysed data covering the first large wave of career politicians in the United Kingdom that entered parliament in 1970. Even here we find evidence consistent with contemporary critiques, suggesting that strong self‐focused dispositions may indeed be embedded in the career politician's role. During subsequent decades, the number of career politicians in advanced industrial democracies have grown, albeit not as much as some critical commentators and many citizens suppose (Cotta & Best, Reference Cotta, Best, Best and Cotta2000; Henn, Reference Henn2018; Heuwieser, Reference Heuwieser2018; Lamprinakou et al., Reference Lamprinakou, Morucci, Campbell and van Heerde‐Hudson2017). Career politicians have also grown more homogeneous in their life experiences and occupational backgrounds and become less descriptively representative of the general public (Allen, Reference Allen2013; Cowley, Reference Cowley2012; Jun, Reference Jun, Borchert and Zeiss2003; Lamprinakou et al., Reference Lamprinakou, Morucci, Campbell and van Heerde‐Hudson2017). Of particular concern in the United Kingdom is the numbers of MPs who have served as special advisers (Spads) or in some political capacity (Abbott, Reference Abbott2015; Goplerud, Reference Goplerud2015).Footnote 23 This increasing homogeneity might have generated more consistent and concerning behaviour across the four dimensions. Certainly, early twenty‐first‐century British citizens criticize career politicians much more and praise them much less than they did 50 years ago (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jennings, Moss and Stoker2018). Our analysis does not preclude the likelihood that strong career politicians themselves have indeed become more self‐focused, eager and strategic in constructing and protecting their careers.

Acknowledgements

This paper draws on research that was supported by the University of Chicago Center for Cognitive and Neuroscience and by the Arete, Templeton and Leverhulme Foundations. We would also like to thank the four reviewers for their constructive feedback on earlier versions of the article.

Ethics statement

The article draws on interviews conducted with 521 MPs between 1971 and 1974. These interviews were part of a study that fully met contemporary institutional ethical requirements. All participants were given written guarantees of anonymity. The University of North Carolina IRB/Ethics Board ruled that the research project did not need IRB approval and was exempted from further review.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

APPENDIX A: SUMMARY INDEX CONSTRUCTION

APPENDIX B: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF ALL INDEPENDENT, DEPENDENT, AND CONTROL VARIABLES

APPENDIX C: REGRESSION TABLES

APPENDIX D: VIF STATISTICS