Introduction

The modern western, capitalist culture in particular comes with a worldview of human superiority, one that not only considers human beings as separate from, but also above the rest of nature (Moore, Reference Moore2017). This dominant and self-centred position of humanity has led to the ongoing control over and destruction of non-human nature, resulting in an unprecedented environmental crisis that is threatening the whole of nature, including humanity (Ibid). If we are to move towards a sustainable future of co-existence on Planet Earth, radical changes are needed in the way we, as human beings, relate to the world around us and most importantly, how we act upon that (Bonnett, Reference Bonnett2002; Braidotti, Reference Braidotti2017; Taylor, Reference Taylor2017).

Such radical changes require inner transformative processes that have the ability to change conceptions of who we are in relation to the world (Abson et al., Reference Abson, Fischer, Leventon, Newig, Schomerus, Vilsmaier and Jager2017; Ives et al., Reference Ives, Abson, von Wehrden, Dorninger, Klaniecki and Fischer2018; Woiwode et al. Reference Woiwode, Schäpke, Bina, Veciana, Kunze, Parodi, Schweizer-Ries and Wamsler2021). Education is one important realm where such radical process of inner transformative change can be facilitated and where, if implemented on a broad scale, a basis for societal change can be set (Wals, Reference Wals, Barnett and Jackson2019; Wamsler et al., Reference Wamsler, Osberg, Osika, Herndersson and Mundaca2021; Wamsler, Reference Wamsler2020; Woiwode et al., Reference Woiwode, Schäpke, Bina, Veciana, Kunze, Parodi, Schweizer-Ries and Wamsler2021). Several critical pedagogies are emerging that question human dominance and that offer alternatives in the form of relational, embodied and disruptive learning practices, adhering to a strand of radical pedagogy in the light of current socio-ecological crises (see for instance Fenton, Playdon & Prince Reference Fenton, Playdon and Prince2020).

Wild pedagogies (WP) are one example of such emerging pedagogies that aim to critically rethink education and learning. Central in this strand of pedagogies is not learning about the world, but learning in, with, through and for the world (Morse, Jickling & Quay Reference Morse, Jickling and Quay2018). WP explore how we can learn as relational beings with the world, embracing nature as a co-teacher in education (Ibid). Jickling, Blenkinsop, and Morse (Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse, Priest, Ritchie and Scott2024) describe eight touchstones as inspiration for working with WP.Footnote 1 They provide a theoretical exploration of WP as a living concept and practical guiding questions on how they can be implemented in education. How WP, guided by the touchstones, could actually take shape in educational practice, is being explored, but remains rather abstract (Ford & Blenkinsop, Reference Ford and Blenkinsop2018; Green & Dyment, Reference Green and Dyment2018; Jickling, Reference Jickling2015).

In this article we aim to provide more concrete understanding of WP both theoretically and practically. Firstly, an explorative literature review is presented to gain more understanding of what WP can mean for educational practice. Secondly, we evaluate three academic courses at Wageningen University (The Netherlands) that have been inspired by WP. The three courses offer relational outdoor learning, engaging with “wild(er)(ness)” in various ways. Based on evaluations of the three course designs over three years as well as participant observations and reflections thereof, we come to provide concrete inspiration for how WP theory could be brought into academic practice. Inspired by Jickling et al. (Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse, Priest, Ritchie and Scott2024)’s touchstones, we specifically highlight what can be understood by (1) Wild and caring learning spaces (2) Learning from self-will and wonder (3) Relational learning with the world and (4) Disruptive learning for the world. For each of these explorative areas we present practical drops of inspiration to come from wild pedagogies to wild education.

Methodology & positionality

Not only does the education we envision take a relational, embodied approach, so does our methodology. As Haraway (Reference Haraway1988) suggested, all knowledge is situated, embodied and partial and therefore inherently subjective. A researcher, in a way, thus, always shapes the research by bringing themselves into the research setting and seeing with these particular eyes. Embracing this notion, we aim for engaged research, where the researcher explicitly forms part of the research environment (Cunliffe & Scaratti, Reference Cunliffe and Scaratti2017). Actively engaging in the research setting, allows for closer interaction with the subject of study, creating space for relations and meaning to unfold (Finlay, Reference Finlay2009). As such, we take a hermeneutical research approach, acknowledging the inevitable influence of interpretation in a research process due to the researchers’ particular being-in-the-world that inherently brings a certain angle to the research (McCaffrey et al., Reference McCaffrey, Raffin-Bouchal and Moules2012). In our research this means we do not act as “objective” outsiders, but engage in the research setting as educators, observers, participants, scientists and designers. To a certain extent, our influence has thereby intentionally shaped the research setting.

The first author of the article has engaged as course coordinator and main teacher in the field for the first of the studied courses (Box 1). In this role, she has also acted as main designer of the course programme. For the other two courses, she has been involved as participant observer. There has been close interaction between the coordinators of the three different courses; the exchanged inspiration and experience thereof is reflected in the course designs. The second author has only been distantly involved in the courses as inspirator and adviser. There are thus multiple researcher roles and levels of engagement in our study that make a clear distinction between the first course, where the main author has been intensively involved with multiple roles and has actively shaped the research setting and the other two courses where the author had the role of participant observer and thereby much less influence on the research setting. Langley and Klag (Reference Langley and Klag2019) speak about the “involvement paradox” that might result from these multiple roles. A paradox that, as they suggest, can be navigated by being open, aware and reflexive on and about multiple entangled researcher roles, which we have tried in our study. Still, the close involvement with multiple roles should be considered while reading this article, since it will have influenced the research.

Inspired by the posthuman, feminist turn in the field of social science (Braidotti, Reference Braidotti2017; Law, Reference Law2019; Mol, Reference Mol2010; Pols, Reference Pols, Olthuis, Kohlen and Heier2014), the particular lens with which we have engaged is a post-humanist lens, approaching the classroom as a multi-species relational learning setting. Hereby we tried not only to reflect upon our own relational presence in the research setting, but also aimed to decentralise the human being as a whole, seeing the human being just as one participant in an educational setting amongst a wider network of both human and other-than-human relations.

Methods used

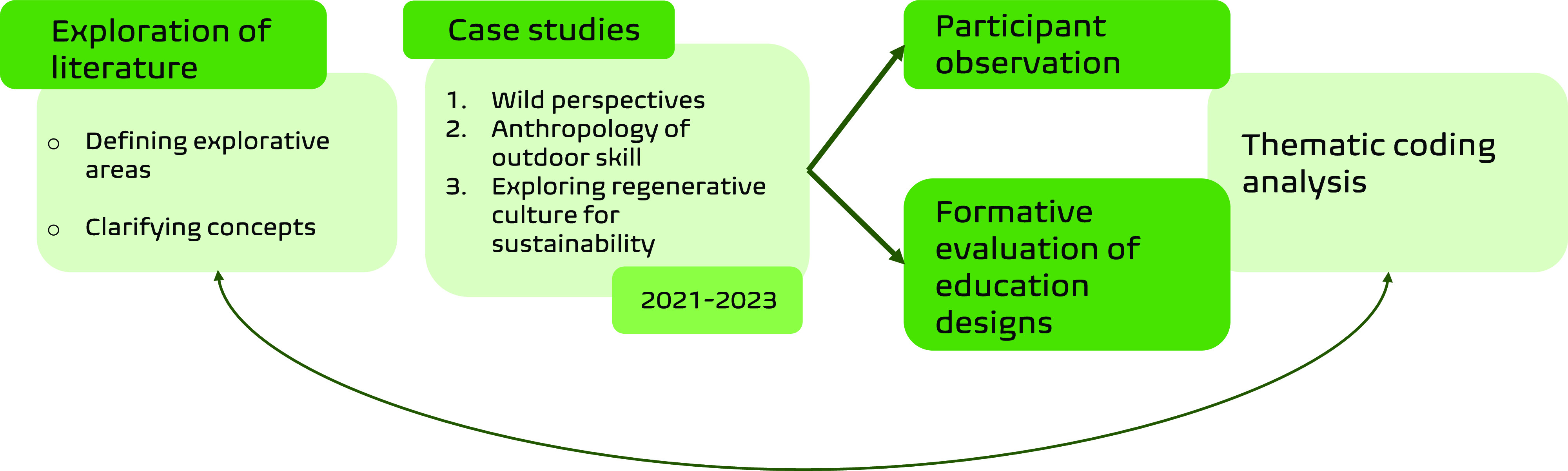

Jickling et al. (Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse, Priest, Ritchie and Scott2024)’s WP touchstones formed guiding inspiration for our research. Starting from the touchstones and an exploration of literature, we identified four explorative areas for formative evaluation of educational designs inspired by WP (Nieveen & Folmer, Reference Nieveen, Folmer, Plomp and Nieveen2013). Three academic relational outdoor learning courses at Wageningen University (The Netherlands), that closely link to WP, were studied for three consecutive years (2020–2023) by participant observation and evaluation of course designs. The resulting formative evaluation of the three courses, allowed us to draw concrete inspiration from educational practice as guiding inspiration for future WP educational design (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of methods.

Exploration of literature and grouping of touchstones

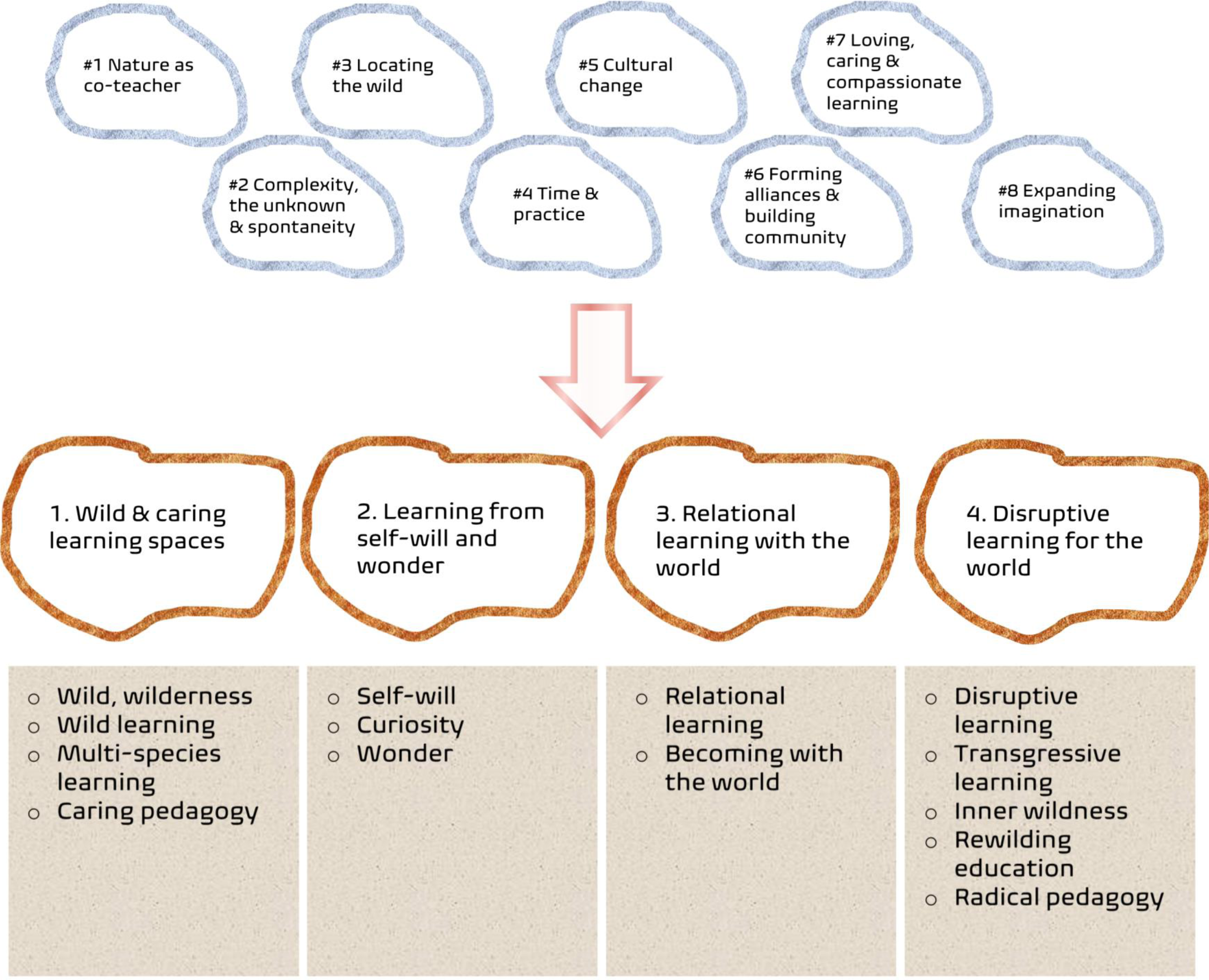

To gain deeper understanding of WP, we explored the literature by snowball sampling. The WP touchstones framework by Jickling et al. (Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse, Priest, Ritchie and Scott2024) was our starting point. The eight touchstones they define, offer inspiration, but remain rather abstract. Exploring the concepts that form these touchstones, led us to cluster the touchstones into four explorative areas that, in our opinion, called for further exploration, both theoretically and practically (Figure 2). The results section (Insights from literature and practice) shows how the existing WP literature led us to the forming of four explorative areas. They aim to clarify and deepen what is understood by (1) Wild and caring learning spaces (2) Learning from self-will and wonder (3) Relational learning with the world and (4) Disruptive learning for the world. The concepts that make up these four areas were searched in Google Scholar, where not already mentioned combined with “learning” and/or “education” as a search terms. This exploration resulted in an elaborate theoretical understanding of the four explorative areas that have formed the basis for our empirical research.

Figure 2. The eight touchstones by Jickling et al. (Reference Jickling, Blenkinsop, Morse, Priest, Ritchie and Scott2024), captured in four explorative areas, listing searched concepts per area.

Case studies

To continue the research empirically, three courses inspired by WP at Wageningen University & Research (Box 1) were studied over three consecutive years (2021–2023) through participant observation and formative evaluation of educational designs. They are all elective courses for academic students (both BSc and MSc). The courses were designed as relational outdoor learning, strongly relating to WP touchstones, though not necessarily knowingly implemented as such. Still, all courses do fit the living theoretical framework of WP.Footnote 2 All courses take place outside and use principles of relational, outdoor, embodied, transformative and/or transgressive learning. The classroom is designed as a multispecies learning setting, in which interactions with the wider natural environment (apart from other human participants in the course) are actively encouraged and embraced as part of education. All three courses aim to be responsive and emancipatory with regard to the socio-ecological crises and both the learning environment and the teaching methods are grounded in an ethic of care.

Box 1. Course descriptions of the three studied courses.

Course 1. Wild perspectives (3 ECTS): Wild perspectives is a one week* elective summer course for students of Wageningen University to explore both human and more-than-human perspectives on landscape and being and becoming in the world. The course tries to offer students ways to “see with new eyes” and to reflect on their own relationships to the more-than-human world. In order to reach such a change or diversification in/of perspectives, the whole course is based in an outdoor setting, allowing for a multi-species classroom in which the non-human is actively invited into the learning setting. Students not only learn in a cognitive way, but also through experience, relation and deep reflection. In the course, theatre exercises, storytelling and -writing and meditation practices are used as learning methods to evoke creativity and embodied, relational learning. Students present the outcomes of their learning through a storytelling performance as well as through an reflective essay that incorporates literature on the subject matter.

* The summer course consists of one week intensive training and experience in the field followed by one month time to read literature and write a reflective essay.

Course 2. Anthropology of Outdoor Skill (6 ECTS): This elective course of 4 weeks at the University of Wageningen is centered around the theory and practice of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Students learn about and through basic nature skill practices, both from an anthropological and from a practical perspective. The course is an example of embodied learning. Students learn for example about the historic use and meanings of fire both by reading and discussing anthropological literature on the topic and by learning basic skills of making fire themselves in a practical outdoor setting. The course is mostly based outside in the forest in order to create a multi-species, relational learning setting in which students can interact optimally with the environment. Besides fire making and use, topics of the course are shelter, food and water, navigation and tracking. In the course, students are invited to critically reflect on “nature” as a concept as well as the relation of human nature to the rest of nature, on the romanticizing of nature/wilderness and traditional ecological knowledge in particular and thus to learn about multiple ontologies and epistemologies relating to human-nature.

Course 3. Exploring regenerative culture for sustainability (3 ECTS): In this course students are invited to dive deeply into their inner worlds and their relations to both the human and non-human world, including difficult encounters in that relational space such as feelings towards climate change and losses of biodiversity. The course departs from a relational and embodied learning perspective and incorporates various experiential learning practices. The training builds on the work of Macy and Johnstone (Reference Macy and Johnstone2012) regarding grief and hope for the environment and works with practices of nature connection and inner sustainability. The course takes place during a one week stay in the forest near Wageningen. Students stay in the camp together the whole week, sleeping outdoors in tents and gathering around a fire that is maintained the whole week. The aim is to build a tribe like setting in order to create a safe and warm space for connection, reflection, sharing, support and personal development. By working on a reflection assignment, students can take this course as a credited course for their education, but this is not mandatory.

Formative evaluation of education design

To draw concrete inspiration from the three courses, we performed a formative evaluation of the educational designs of the three courses. Nieveen et al. (Reference Nieveen, Folmer, Plomp and Nieveen2013) describe how formative evaluation of educational design can be used to develop improved design principles. In our study, we do not aim to come with specific design principles, but we do aim to infer clear examples of educational design implementation of WP aspects to provide concrete inspiration for future WP design.

The formative evaluation of educational designs in our study consisted of the investigation of course guides and additional course materials of the three case study courses over three years. By studying the course materials over three consecutive years, we could not only study the course designs at one point in time, but also the evolution thereof, based on experience, exchange and new knowledge.

Participant observation

As an addition to the formative evaluation of course designs, participant observation made it possible to observe WP in practice and more importantly, to become part of them. Participant observation allows to study a learning setting from the inside, being able to observe, but also to relate to the subject of study (Jorgenson, 1989). Participant observation in our study made it possible to experience the educational designs in practice and thereby adding embodiment and experience as a crucial element of an engaged educational evaluation study. The embodied experience allowed us to provide concrete examples as inspiration for future WP practices. Participant observations all took place in the first year of the study (2021).

Analysis

Both the course designs and the field notes of participant observations were systematically analysed by deductive thematic coding in Atlas.ti. The four explorative areas were used as main themes in order to categorise the data. Within these themes, observations were clustered in sub-themes that led us to form practical drops of inspiration for each explorative area.

Insights from literature and practice

The following section zooms in on the four explorative areas we distilled and that ask for a deeper understanding and most importantly, hands-on inspiration that clarifies how these aspects can be translated into actual education practice. For each explorative area we first present insights from literature that aim to inspire a common understanding of concepts. Insights from literature are followed by insights from practice (our evaluation of the three case studies) that made us infer drops of inspiration for each explorative area that aim to inspire future WP educational design. The four explorative areas naturally relate to each other and may appear to overlap. In the text below we hope to clarify what we understand by the four areas, why we have composed them as such and how they relate to the existing WP theory.

Wild and caring learning spaces

Insights from literature

Morse et al. (Reference Morse, Jickling and Quay2018) describe how WP are situated in wild learning spaces. Such wild learning spaces are understood as self-willed spaces; self-willed, relatively uncontrolled natural places, ranging from urban wilderness to wilderness further from human culture. However, wild in this context does not only refer to wild spaces in which learning takes place, but also to inner wildness, referring to learning from self-will, wonder and intrinsic motivation. It refers to less controlled learning, allowing for curiosity and spontaneity inspired by the landscape and students’ interests. It opens up space for uncertainty and unforeseen directions (Morse et al., Reference Morse, Jickling and Quay2018). A wild classroom as such allows for a more-than-human, relational space for learning, in which relations to the self, to other human participants and the wider natural environment can be explored and where these interactions form the basis for learning. The other-than-human world is seen as a co-teacher, by whom we can be taught by deep listening, attentive receptivity as well as relational and reflective experience (Blenkinsop & Beeman, Reference Blenkinsop and Beeman2010). Learning then, becomes a relational act in itself. From teachers and students this asks humility and an open, receptive attitude towards the natural space in which learning takes place. It asks a deep listening and understanding of the history of a place and its relations (Stewart, Reference Stewart2004). Only from such a state of humble openness can we be taught by the natural world as a co-teacher (Blenkinsop & Beeman, Reference Blenkinsop and Beeman2010). Moreover, wild learning is understood as disruptive education, breaking with current unsustainable, human-centred learning practices and moving towards more sustainable, relational alternatives (Morse et al., Reference Morse, Jickling and Quay2018; Snaza, Reference Snaza2013).

A wild learning space thus offers a multi-species relational learning setting, inviting both inner human and other-than-human wilderness into the classroom. Such a multi-species classroom links to the common worldsFootnote 3 approach in early childhood education, which describes how children and their natural learning environment are co-creators of a shared experience as members of a shared community (a common world), where “the learning emerges from the relations taking place between all the actors—human and more-than-human alike” (Taylor & Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Taylor and Pacini-Ketchabaw2015, p. 508). This is how a multi-species relational learning setting could be understood, as a collective human and other-than-human learning setting, where learning emerges from both intra- and interspecies interactions and experienced relations.Footnote 4

Wild learning asks for a radical reconsideration of how learning is understood. It becomes a radically relational experience. And at the core of such experiences lie existential questions of how we relate to the world around us—questions on who we are as relational beings in a complex, interconnected and rapidly changing world (Blenkinsop & Ford, Reference Blenkinsop and Ford2018). Facing such existential questions requires a safe space, for sharing, for emotions, for deep learning to take place. As hooks (Reference hooks1994, p. 13) states ‘“to teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin”. Such a caring pedagogy requires from both students and teachers a willingness to engage, to challenge and be challenged and an open and respectful attitude towards all that comes forward (Newstead, Reference Newstead2009). A caring pedagogy extends beyond the transmission of knowledge to include nurturing relations towards the self, the other (being human or other-than-human) and the wider world, including all that is happening to it (Macy & Johnstone, Reference Macy and Johnstone2012; Newstead, Reference Newstead2009). It asks for introspection, deep listening, relating, inviting emotions into the classroom and opening space for grief towards the world (Macy & Johnstone, Reference Macy and Johnstone2012).

Insights from practice

The three studied courses first of all embrace the notion of wild spaces, by teaching and learning outdoors, situating the classroom in relation to the wider natural world. Two of the courses have their home base in the forest, one in a community garden. These places form the basis for the wild learning that the courses offer. From that home base, all the courses explore the nearby environment by activities that stimulate experiential learning with and through nature. Not necessarily does all the education have to take place outside. Depending on the context and set-up of the course, partly online or campus-based activities for theoretical elements can work well, in combination with outdoor activities and/or a multiple day outdoor stay in nature. Such a mixed set-up allows for better alignment with the academic calendar, for larger groups of students participating as well as for efficient engagement with theory and literature and individual (reflective) time for assignments, without compromising on experiences in and with nature.Footnote 5

All the courses engage in a relational way with the environment, thereby creating a multi-species relational classroom, where learning does not only take place in, but also with, through and for wider nature. The forming of such a classroom asks more than just being in nature—it invites interspecies interactions and the building of relationships towards the other-than-human part of the classroom as well as reflections on these relational experiences. In the studied courses, we see how this starts with relational grounding—with getting to know the place where learning takes place by diving into its history, by observation, deep listening, exploring and interacting with the whole body, using all the senses. In the course designs, we see how this relational grounding forms the most important part of the first day in the field. Besides getting to know the other students, activities are focused on relating to the learning environment itself, starting with getting to know the stories and related histories of the place, followed by individual exploration using embodied mindfulness techniques. Observations of course 1 and 3 provide clear examples of relational grounding:

Box 2. Examples of relational grounding

Intention totem: In course 1, on the first morning, students are invited to walk slowly through the area, observing all there is in a way as if they never saw grass, trees, flowers, leaves and whatsoever before. If something catches their attention, they can stay with that being or element for a while and attach an intention for the course to it. If it is something they can take with them, they can bring it back to where the students come together in silence. One by one they step forward and share who or what they encountered and if they want, what intention they connected to that. They place all they bring into a dedicated place that becomes the intention totem for the whole course, where they can always come back to, to be reminded of their intentions and to connect to the place and all its other-than-human elements (Participation course 1, 2021–2023).

Sit spot: Next to other relational grounding exercises (getting to know the history & stories of the place, formulating and sharing intentions inspired by the environment), course 3 works with a sit-spot exercise, where students choose a spot in the nearby forest that attracts them. They sit in that place for 15-30 minutes every day, building a relationship to it by observing and experiencing that specific place, using all the senses (Observation notes course 3, 2021)

The multi-species relational learning approach takes further shape during the rest of the courses by various experiences in and with nature. To facilitate a multi-species learning environment, course 1 and 3 engage with (reflective) mindfulness, visualisation, theatre and body expression exercises, where students practice with embodying other-than human perspectives. An example of where these techniques come together is the council of all beings,Footnote 6 that is used in both courses as a way of deep engagement with other-than-human inner worlds:

Box 3. Embodying other-than-human perspectives: the council of all beings

Council of all beings: Students are introduced to the idea of the council of all beings and are then sent out into the fields/forest to let themselves be inspired by the environment in choosing an other-than-human being they want to represent in the council. They have some time to empathize with that being. What would it need? What is it effected by in today’s world? The students return then in silence to the common place where the facilitator has spread out craft materials which the students can use to make masks. In utter concentration students work on their masks and slowly they become the being they represent. When all students have finished their mask, they are invited to wear it and join the council of all beings. And there we are, a council of the soil, the ocean, the stones, the coral reefs, the mosses, the oak, the woodpecker, the humus layer, the penguins, the bees, the water, the fire and the ferns, with all our wisdom and worries. All beings get the opportunity to introduce themselves and share why they are here today in this council. The introduction round already becomes emotionally heavy, when beings share how they are affected by human induced climate change and ecosystem deterioration and how worried they are. For all that is shared, the other beings mumble “we hear you” to express empathy and a sense of togetherness in worrisome times. At a certain point those who want are invited to take of their masks and find a spot in the middle to listen to the council as human-beings. With a group of three other human beings I sit in the middle for a while and the experience changes radically. As human beings we can now really feel and hear the concerns of the soil, the worries of the coral reefs, the call of the mosses. A feeling of collective shame emerges from the inner circle (of human beings). Shame for not respecting the beings that support us in so many ways. But also thankfulness, for the soil carrying us and providing us with nutrients, for the water fulfilling so many basic needs, for all beings to keep the system balanced. I see how touched all students are by this experience, being it as the being they represent, as a human being or as themselves. To end the council on a more positive note and create a sense of active hope (which is definitely needed I feel), the facilitator asks all beings to share their wisdom that can help humanity to navigate the crises they have created for all, to rebuild connections and respect all other-than-human beings. (Observation notes course 3, 2021)

Box 4. Multi-species relational learning: learning with the forest by attentive observation

Tracking: The teacher explains how tracking (following animal tracks to locate animals and understand their behaviour) is mainly a way of looking at the environment. He gives a further explanation of tracking while walking through the forest and observing it closely. When he notices something that may be a track, he explains what he is seeing and what it might mean. It is a way of observing the forest that requires to step out of the human perspective, into the perspective of forest animals. How do they use the forest? What do they need? Students are then sent out into the forest in small groups to observe and explore the forest as deer, squirrels, badgers, foxes and what more to see whether they can find their tracks and make meaning of it. Afterwards they share their observations and interpretations during a round where the potential tracks are visited. (Observation notes course 2, 2021)

Fire making: Already on the first day the students are introduced to importance of fire. Fire is a central element in the course, where several aspects come together. They learn about the history of fire making and its crucial role in human evolution as well as traditions around and meanings, threats and uses of fire both in the past and the present. Apart from the anthropological knowledge, the students experience all these aspects of fire during the course. Students learn what is needed to make fire—fuel, heat and oxygen. During the course it is their own responsibility to look for tinder and wood, which asks again attentive observation of the environment. What could be respectfully used to start a fire? What materials can be used and in what condition? Where can they be found? And how can they be stored? Once they have collected the tinder and wood, they are introduced into traditional ways of starting fire—by friction using the fire bow and by flint and steel. The students practice these techniques and experience how hard it is to start a fire from in such a basic way. It is fascinating to see how students help and encourage each other and how they cheer when somebody succeeds. Once they have started the fire together, it creates a warm place which naturally serves as a central point where students come together. Throughout the course, fire warms the students and warms the space for storytelling, connecting and sharing experiences. The students become fire keepers. And that comes with responsibility regarding the dangers of fire. They learn how to start the fire safely in the forest, how to keep it safe and how to leave it safely (which comes with attentive observation of the environmental conditions—if the forest is too dry or the wind too strong, there may be no safe option to start a fire). (Observation notes course 2, 2021)

Course 2 mostly works with embodiment through skills trainingFootnote 7 and attentive observation of the environment, thereby learning how to read an ecosystem and how to respectfully use it relationally. Observation notes on two activities in course 2, illustrate how students learn with the forest through attentive observation and interpretation:

In all courses, students are offered a deeper relational experience with the natural environment by at least one overnight stay and by some sort of solo exploration of the area. Course 1 offers small bits of solo exploration by forest bathing, a walk in silence and meditation exercises with the natural environment. Course 2 and 3 take it deeper by working with sit spots (Box 2) and a vision quest in nature.Footnote 8 The vision quest offers a deep reflective and relational personal experience with the natural environment by spending a considerable amount of time with nature by oneself. A vision quest traditionally stretches over multiple days (Foster, Reference Foster1998). The courses offer in that sense a “light” version of two hours in course 2 to seven hours in course 3. The overnight stay in the forest allows the students to be with the forest the whole night, which offers a completely different experience than meeting the forest during daylight. In course 1 and 2, students learn how to pitch tarps in the forest and sleep under the half open tarps. For most students, this is a new experience, which makes them experience the forest in a much more intimate way during the night. Also, spending the late evening and the early morning together in the forest, seems to connect the group in a way that is not possible during day activities. Participant observations in course 1 and 3 made it possible to experience the relational effect of being with each other and with the forest during the night.Footnote 9 All students were assigned responsibilities to take care of the “tribe” by making fire, keeping it going, preparing meals, waking each other up in the morning, preparing breakfast, cleaning the camp and supporting each other where needed. The overnight stay in the forest thus both offers a deep experience with the forest, but also facilitates a basis for bonding and caring within the group of students. More elements in the courses do however contribute to the classroom of care that is needed as a basis for deep relational experiences.

Box 5. Deep relational experience with nature by solo exploration

Solo vision quest in nature: In course 3, the program builds up towards the vision quest, that is seen as the ultimate nature experience on day 4 of the forest stay. Students are prepared in the days before by smaller experiences in and with nature, by mindfulness exercises and moments of deep reflection. On the evening before the quest, they eat a sober meal and go to bed early to be ready for the vision quest, starting at 6 o’clock in the morning. One by one, student are sent out into a nature area they will explore for the next 7 hours by themselves, with nothing more than themselves and the environment. To focus the experience entirely on the being with the nature, students do not eat nor drink from the evening before till the festive meal after the quest. In the evening, students share their experiences around the fire while the others listen carefully and supportively. (Observation notes course 3, 2021)

In all courses we see how care forms a crucial element in the creation of a suitable environment for relational learning experiences. Apart from the interspecies relational grounding that was highlighted before (Box 2), social relational grounding at the start of a course, can nurture senses of care, support and respect within the group of students and teachers. The social relational grounding is especially visible in course 1 and 3, where the first day of being together, mainly focuses on sharing intentions and personal motivations to take part in the course. The introduction exercises that are used, ask for an attitude of respect and vulnerability, which, when adopted by all students, create a safe and supportive learning space. This supportive and caring space is central and crucial in the experiences that students go into together. From participation in the courses, elements could be distilled of how such a classroom of care can be created and maintained throughout the course and how it serves as a crucial basis for deep relational experiences with the self and others, being human or other-than-human. The first element seems to be a warm and cozy home base for learning, where students can start from and come back to, where they can come together to set intentions and share experiences and where there is time for tea and informal conversations. All the studied courses have such a home base that facilitates the coming together of the students and where a fire can be made or is always present in the middle.

To make the cozy space also a safe space, not only at the home base, but extending towards all the experiences the students go through together, the classroom of care needs an attitude of support and encouragement that is carried by the whole group. From participation and observation in all the courses, it becomes clear that the sharing of experiences, emotions and intentions is a crucial element that makes students feel safe and welcome. The few students that dare to share difficult feelings such as shame, fear or resistance, generally induce a shared feeling of relief for others that feel similar, which allows all students to share safely and to feel carried by the group. Students support and encourage each other. From my observation notes (course 3, 2021) I read:

“It is so wonderful to see how supporting and caring our ‘tribe’ is. There are so many tears every day, but even more hugs. People are seen and heard, carried by the group.”

“Key was the simple sentence ‘I hear you’.”

And from course 2 (2021):

“The students learn how to make fire using firesticks, the fire bow, firestones and steel together with the forest materials they collected earlier and dried overnight. It is wonderful to see how they all help and encourage each other. When somebody succeeds in creating a flame, the whole group cheers and claps.”

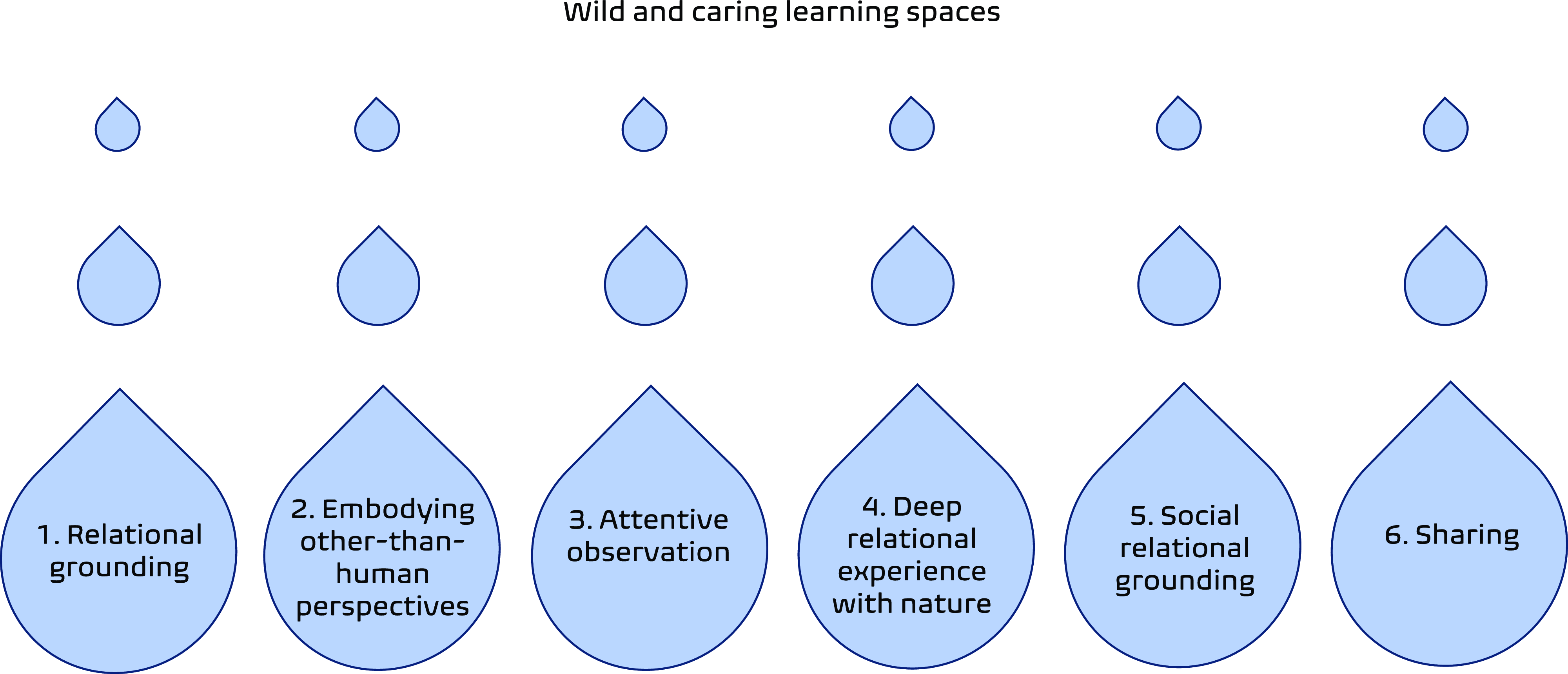

The insights from practice allow to distil some elements, or drops of inspiration, for how wild and caring learning spaces could be realised (Figure 3). These are the first drops to form a stream of inspiration for the practice of WP. More drops of inspiration are drawn from the next paragraphs.

Figure 3. Drops of inspiration for realising wild and caring learning spaces.

Learning from self-will and wonder

Insights from literature

WP aim for a learning from curiosity, self-will and wonder, moving towards inner transformative changes. Self-will in this context relates to many aspects of WP, such as the self-will of wider nature, learning in self-willed (i.e. wild) places, to intrinsic motivation and to learning that embraces uncertainty and unforeseen directions (Morse et al., Reference Morse, Jickling and Quay2018). Based on an experiment with self-willed learning in the context of wild pedagogies, Jickling (Reference Jickling2015, p. 158) describes how “self-willed learning is unaccountable in the language of learning outcomes and measurable achievements. It just announces itself. And, that is the joy.” Self-willed learning refers to experiences of awe and inherently to a learning from curiosity and unexpected encounters. The next paragraph discusses how these notions of self-will, curiosity, awe, spontaneity and inner transformation are all touched upon in looking closer into the educational understanding of wonder.

While curiosity is related to wonder, the two are fundamentally different. Curiosity refers to a search of new knowledge, an eagerness to learn something new, to discover. Curiosity has a restless character, a constant search for excitement. When something new is discovered, one moves to the next to keep learning and discovering. Curiosity moves too fast to actually wonder, to be struck by awe, to be touched, to care (Di Paolantonio, Reference Di Paolantonio2019). Schinkel (Reference Schinkel2017) links curiosity to a form of wonder he calls active wonder, which indeed relates to curiosity, an eagerness to inquire, a desire to understand and openness to novel experiences. It could be referred to as the intrinsic motivation to learn, which is expected from all students, but may not always be present in the traditional classroom. Besides active wonder, Schinkel describes deep wonder, as a fundamentally different form of wonder that is rarely seen in education. Deep wonder refers to awe, to an experience of mystery, a whole body existential experience that tends to transform something in ourselves in relation to what was just experienced. It is a form of wonder that acts slow, that requires space, time, imagination, reflection and an openness to the world to be touched by it. It embraces not-knowing and does not have a certain direction. Deep wonder thus goes beyond curiosity, as illustrated by a quote from Schinkel (Reference Schinkel2017, p. 543) “wonder [as compared to curiosity] does not seek new ground, it changes the ground under one’s feet.” And it is precisely deep wonder that is rarely part of education, but what could significantly contribute to its meaningfulness and transformative potential (Ibid). Deep wonder seems exactly what WP are aiming for to inspire fundamental changes towards a caring relationship with the world.

“wonder implies a longing for meaning; but in many cases especially deep wonder borders on and may lead to a love of the world”—Schinkel (Reference Schinkel2017, p. 549)

We could thus say that active wonder includes WP’s aim for learning from curiosity and self-will, while deep wonder goes beyond this and relates to its aim for inner transformation through deep experiences with nature and the overarching aim of taking care of the world. Deep wonder also complies to WP’s embracement of uncertainty and unforeseen directions. The two-layered definition of wonder, referring to active wonder and deep wonder, as described by Schinkel (Reference Schinkel2017) is used as a guideline to explore learning from such wonder in the practice of WP.

Insights from practice

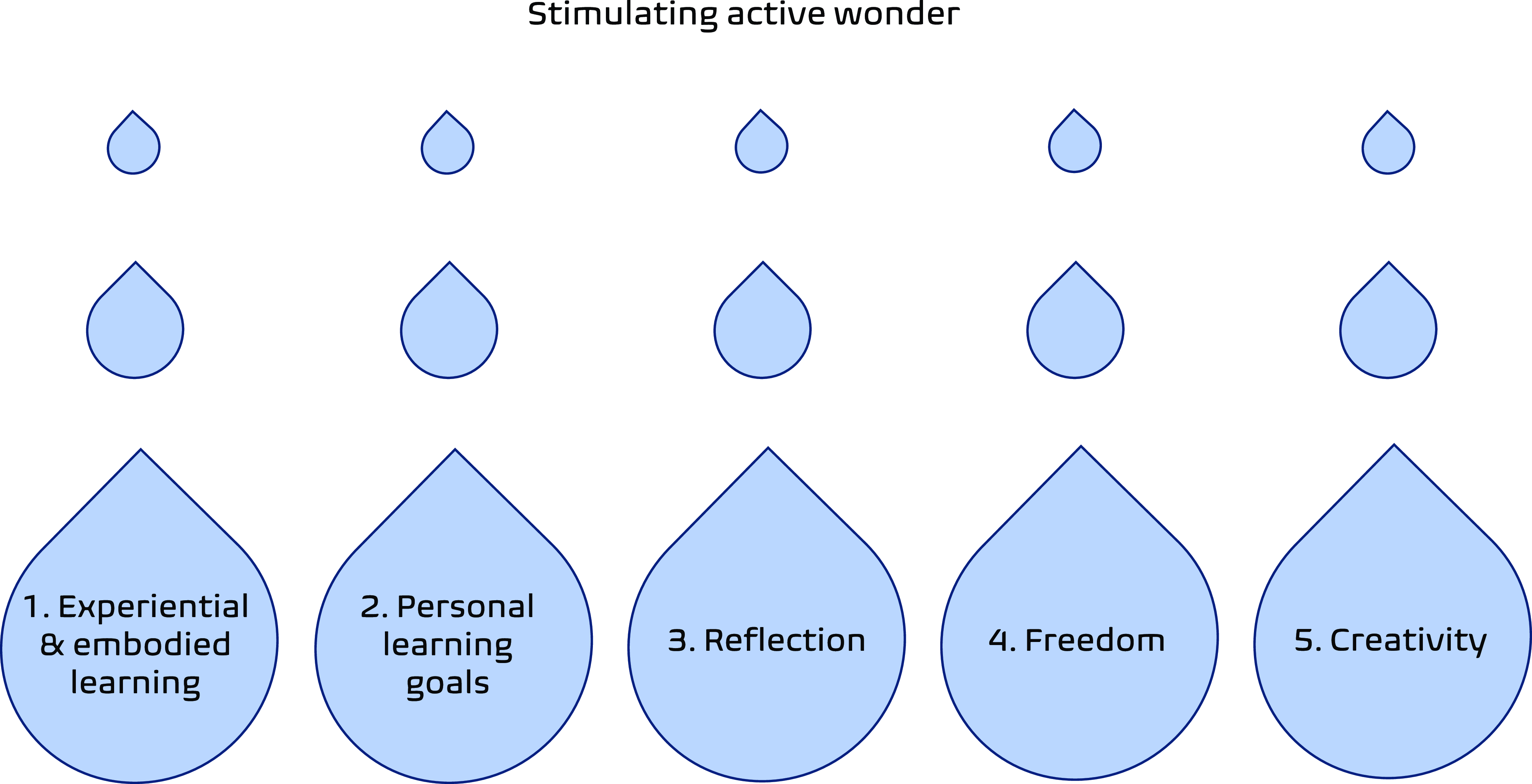

The design of all the three courses is such that active wonder is stimulated (Figure 4). The courses are all built on experiential and embodied learning, which stimulates the students to discover, to explore, to use their senses and to learn from curiosity. At the start of each course, students are stimulated to formulate and share personal learning goals. During the courses, students are encouraged to reflect on their own learning journey. Within the programmes, students are offered certain exercises or activities, but within that, they have the freedom to create their own experiences and to follow their own interests. This can be seen for example in the assignments for all the courses. There are certain guidelines, but students are free to choose their own topic, allowing them to dive deeper into something they are inspired by. Students are also free to use their creativity in choosing a form in which they present their thoughts and experiences; they can use for example art, poetry, storytelling or music to express themselves in a way they want.

Whereas active wonder can be relatively concretely stimulated by certain aspects of course design and ways of teaching and learning, facilitating experiences of deep wonder is a whole different story. The word facilitating is key here, since it comes to facilitating time, space and certain deep experiences that stimulate an openness to the world, the opportunity to be touched, to see with new eyes and ultimately to experience awe, mystery or what one could call wonder. Creating optimal circumstances to allow experiences of deep wonder is the only thing a teacher can influence in this case. Whether it then “announces itself,” as Jickling (Reference Jickling2015, p. 158) promptly phrased it, is out of reach of the teacher, and that is indeed exactly the joy of it.

In all the studied courses, both smaller and more prominent moments of such space and time for intimate experiences with nature are indeed created and sometimes they do indeed result in experiences of deep wonder, being it small or existential. In all courses mindfulness practices in and with nature are offered that allow the students to observe the environment closely, to relate to it and to reflect upon oneself in the wider relational space, mostly inspired by Jon Young’s work and adapted from there (Young et al., Reference Young, McGown and Haas2010). The sit-spots (Box 2) practiced in courses 2 and 3 are very concrete examples of such personal time and space to relate, to observe with an open mind, they are moments to let curiosity make its way towards wonder. The solo explorations offered in these courses (Box 5) take such experiences further, by creating more time and space for unexpected encounters and experiences to occur and allowing space for students to experience and encounter with their whole being. And when they do, indeed moments of wonder do occur and students are deeply touched by them. After the experience of the short solo vision quest offered in course 2, a student shares:

“I ended up at a completely different spot than I was aiming for. It was like watching tv; so much life to see around me. I had this pressure that I wanted to meditate, but I just sat down with closed eyes and experienced the wisdom and connection of the tree I was sitting next to. (Observation notes course 2, 2021)”

The experience illustrates how an open attentiveness and letting go of beliefs on how things should be, can give rise to unexpected encounters and experiences to occur.

When sharing experiences of the longer solo quest in course 3 (2021), several students describe it as “approaching the world as a child,” referring to experiencing the world as if it was the first time they saw it and approaching everything with endless curiosity and deep attention. Observation notes read:

“They approached the natural world like children, with endless curiosity and wonder. They started to notice so many things they never paid attention to. The softness of moss while sleeping on it naked, the beauty of dead trees, the daily life of ants and other insects.”

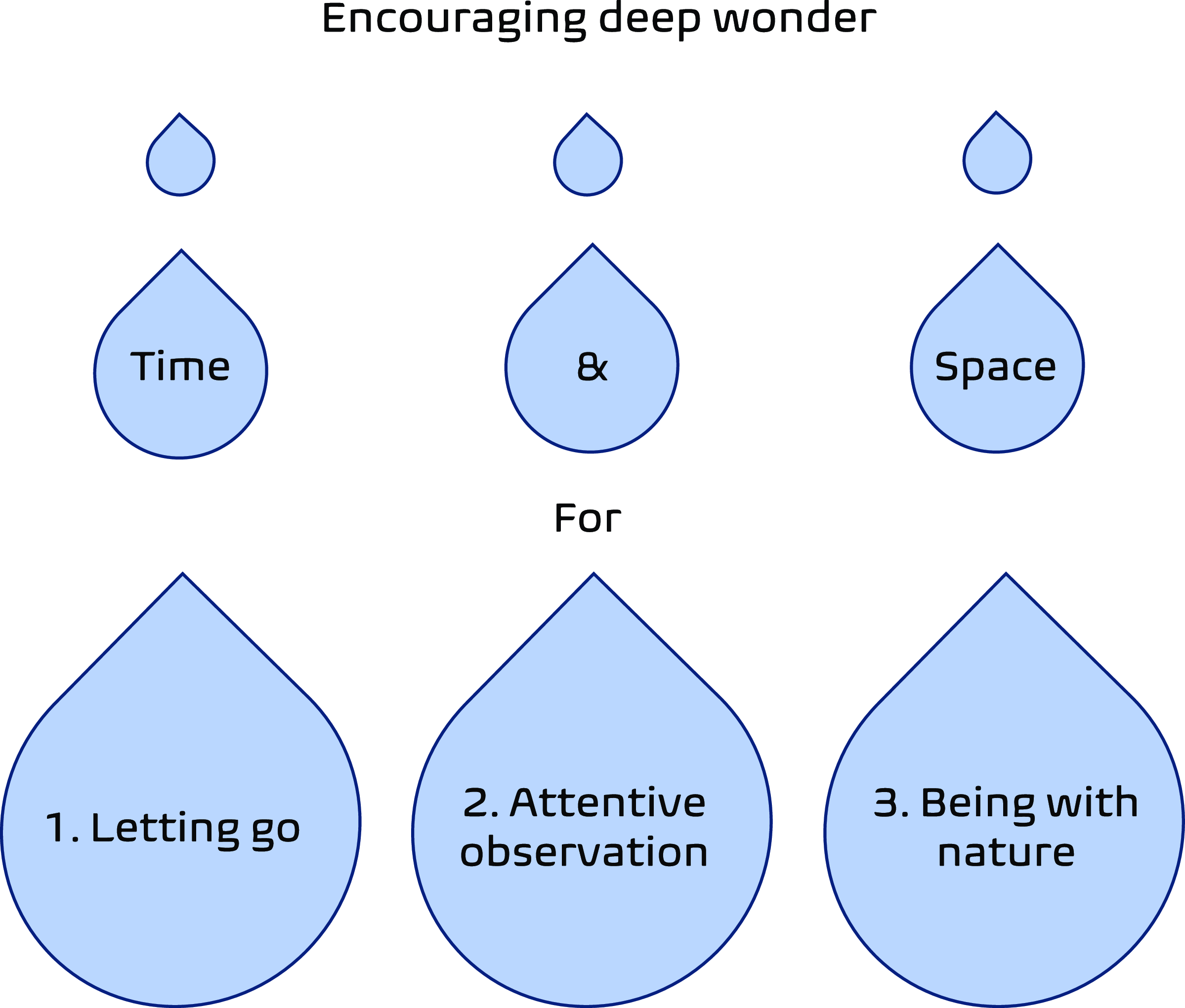

Deep wonder tends to occur just there where all instructions are let go off and students can just be with nature for a while to explore their relational selves, to observe deeply with and open mind and to experience the world without any preconceptions. Allowing space and time for such letting go, for attentive observation and for just being with nature seem to be key elements in the encouragement of deep wonder in education (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Drops of inspiration for stimulating active wonder in education.

Figure 5. Drops of inspiration for encouraging deep wonder in education.

Relational learning with the world: nature as a co-teacher

Insights from literature

At the basis of wild pedagogies lies the multi-species relational learning environment, as an attempt to learn not only in but truly with and from nature (Morse et al., Reference Morse, Jickling and Quay2018). It comes to more than learning about nature, with nature as a surrounding, but moves towards learning about the self in relation to nature through experiences with nature, towards learning as a relational being (Ford & Blenkinsop, Reference Ford and Blenkinsop2018). Or as Taylor (Reference Taylor2017) describes it, a “becoming with” approach to learning, stressing the relationality that lies at the centre of our being and becoming (Braidotti, Reference Braidotti2017; Haraway, Reference Haraway2008; Mol, Reference Mol2010). And it is something we only have to remember, since as young children, this is exactly how we have learned. As already stated two centuries ago by Pestalozzi (Reference Pestalozzi1898), “from the moment in which our minds receive impressions from nature, nature teaches us.” Footnote 10 The moment we go to school though, this way of learning isn’t recognised as learning anymore. Blenkinsop and Beeman (Reference Blenkinsop and Beeman2010) explore how a remembering of such early learning in, with and through nature could be remembered and whether and how it could serve institutional education. They describe how learning in relation asks for a deep listening to the world, for attentive receptivity, a “being in the world such that the world is listened to” (p.32). It asks an attitude of vulnerability to a place in order to move towards intimacy with it (Ford & Blenkinsop, Reference Ford and Blenkinsop2018). The classroom then becomes an ecosystem, where self and place co-create meaning (Blenkinsop & Beeman, Reference Blenkinsop and Beeman2010).

For multi species relational learning to take place, learning would thus need to take place in a multi-species, more-than-human environment, a self-willed (i.e. “wild”) place we could call “nature.” But as has become clear, only having nature as a surrounding is not enough, multispecies relational learning requires interaction with the other-than-human environment through an openness, a receptivity towards the world so that nature can be a teacher in a way no human teacher could be.

Insights from practice

In all the studied courses, nature is actively embraced as a co-teacher. Learning from nature starts with attentive observation (see paragraph 1.2, 2.2 and Box 4), with approaching nature with an open mind, with eyes as if they were never used before, and most importantly, with curiosity to learn from nature. Meditation and mindfulness techniques in and with nature are used to embrace an attentive receptivity towards the world, which is key in learning from nature. Course 1 for example uses the practice of forest bathing (Box 6)Footnote 11 :

Box 6. Practising attentive receptivity by forest bathing

Forest bathing: In course 1, on the first day, students dive into the practice of forest bathing in order to slow down and tune in with the natural world. Through a series of mindfulness exercises in and with the forest, students learn to closely observe, to listen deeply, to feel the pace of the forest, to smell it and to relate to it. (Course guide course 1, 2023)

Examples given before, such as the council of all beings (Box 3) and tracking animals (Box 4) show how embodying other-than-human perspectives (paragraph 1.2) makes it possible to detach from the human perspective (to a certain extent) and embrace an other-than-human perspective (again, to a certain extent) in order to see with new eyes and to discover new ways of learning by observing the environment in a different way. Course 3 thoroughly explores the embodiment of other-than-human perspectives to learn in new ways. Observations from this course show examples of how students almost become other-than-human nature and experience the world through that lens:

“We started the day running and playing like a tribe in the forest. Barefoot we ran and played in and with the forest. Using the fox walk we sensed the environment with our toes. We seemed to become really part of the forest. Not only seeing it, but smelling, feeling, hearing and tasting it as well. Blindfolded we tried to pass each other silently. We hid for people in the forest, since as other-than-human animals that was our instinct.” (Observation notes course 3, 2021)

Also after the vision quest (mentioned earlier in Box 5 and in paragraph 2.2), students of course 3 describe experiences of coming so close to nature that they really feel part of it. These experiences go beyond embodying other-than-human perspectives, they are experiences of becoming one with nature.

“Students share experiences of slowing down, of carefully listening, of sensing, of hearing, of connection, of being part of nature. Most students went barefoot and off the tracks with a slow fox walk pace. Some even felt the urge to go naked (and did so). In almost all the stories I could hear how slowing down, being all alone and having nothing else to think about than just being in nature for 7 hours, allowed participants to come very close to nature. For most closer than they’d ever been.” (Observation notes course 3, 2021)

“Many stories [of students sharing their experiences of the solo vision quest in nature] show how being so close to nature makes the students feel accompanied by so many other beings and thus not alone at all. Stories show how by surrendering to nature, the natural world accepted them as being part of it. They noticed the birds coming closer and the deer and wild boar not being scared by their presence.” (Observation notes course 3, 2021)

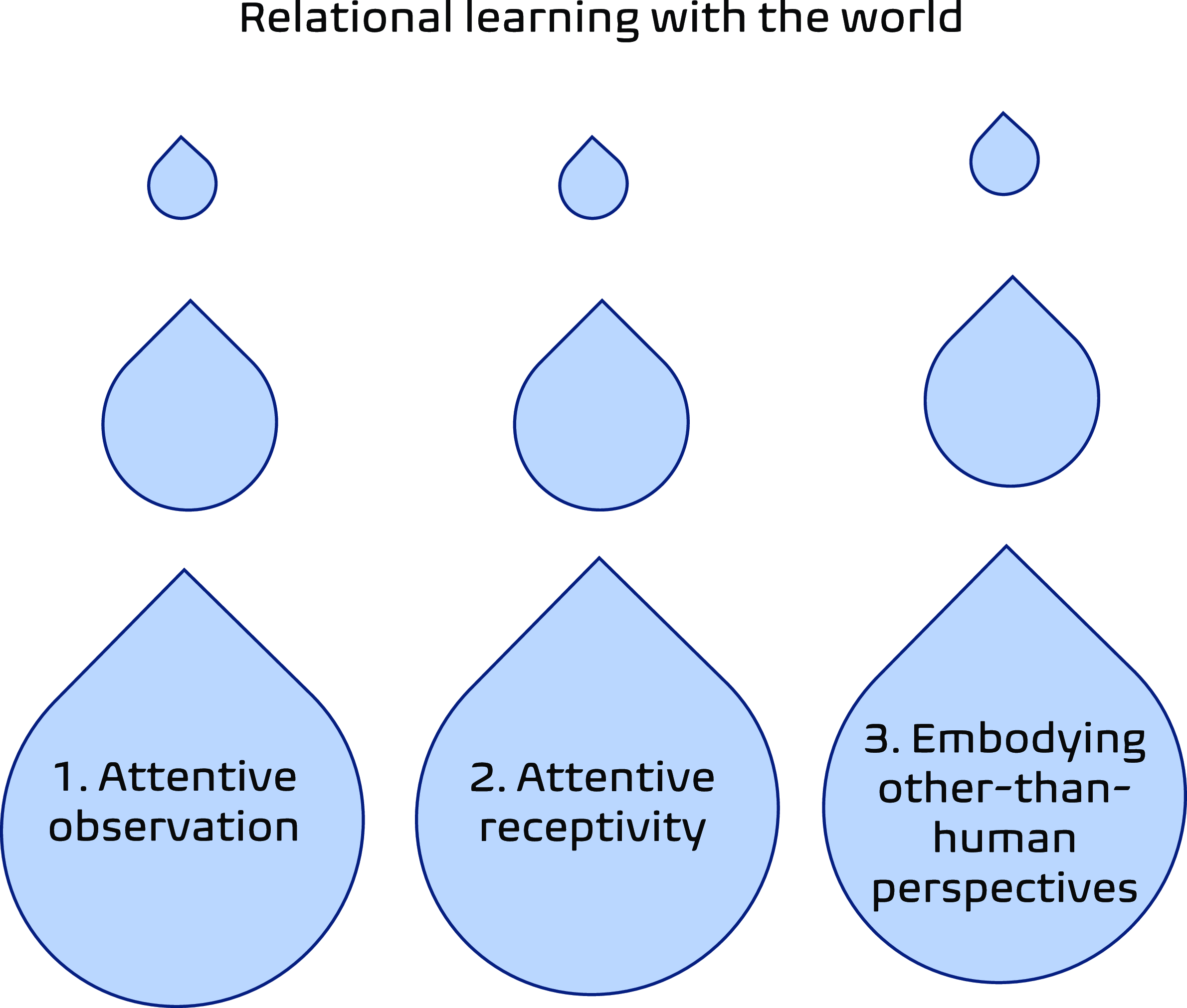

Just like deep wonder, the element of nature as a co-teacher is abstract and hard to grasp. Teachers can create opportunities for students to listen and connect to the natural world, to tune in and to embody other-than-human perspectives and eventually to experience being part of nature, but it cannot be forced upon them. And also what exactly is taught by nature as a teacher is completely dependent on the personal experiences of students. From observations of the three courses it does seem though that when these opportunities are created and embraced by students, learning experiences arise that indeed no human teacher could have taught them. Attentive observation and the practice of receptivity as well as embodying other-than-human perspectives seem to be key elements in this that can be practiced and implemented in an educational setting (the aspect of becoming one with nature is left out here since it is an outcome that can be experienced, but not an educational tool or approach to learning) (Figure 6).

Disruptive learning for the world

Insights from literature

“times like these […] require thinking-doings that are abundantly wild” (Halberstam, Reference Halberstam2019)

Morse et al. (Reference Morse, Jickling and Quay2018) describe how wild pedagogies aim to be disruptive practices, critically rethinking education, breaking with current assumptions of authority and control in education and as Geerts and Carstens (Reference Geerts and Carstens2021) add, a breaking free of the capitalist mindset that has entrapped us. The aim of disruptive learning fits in what Wals (Reference Wals, Barnett and Jackson2019) describes as transgressive learning, aiming to disrupt structures of unsustainability that have become normalised. Apart from a disruptive aim on an institutional and/or political level, disruptive education refers to personal disruptive experiences in relation to the world, that may be uncomfortable, challenging students out of their comfort zones and thereby sparking a reconsidering of who we are as relational beings. When these experiences are uncomfortable within acceptable boundaries, they can fundamentally change one’s understanding of and relation to the world. Learning then becomes an existentially transformative practice (Wals, Reference Wals, Barnett and Jackson2019).

WP do offer such radical, disruptive alternatives to current, often unsustainable learning practices, resisting the human-dominant modern thinking (Fenton et al., Reference Fenton, Playdon and Prince2020). They make us rethink how we go about education, reconsidering relationships and roles and revisiting the core values of education, aiming at more (nature) inclusive education practices that aim for care towards the world. This is one way of how the “wild” in wild pedagogies can be explained, as the aim to do things radically different to come to better alternatives—to rewild education practices with relational, care-full alternatives (Geerts & Carstens, Reference Geerts and Carstens2021). Such a rewilding would involve an embracement of uncertainty, of spontaneity—a letting go of controlling the outcomes of education. It opens up space for wonder and unexpected outcomes as well as other-than-human perspectives into the classroom (Morse et al., Reference Morse, Jickling and Quay2018). Moreover, WP aim to disrupt conceptions of ourselves as human beings in relation to the world, finding the wildness in ourselves and reconnecting in a way we feel part of and take care of the world around us (Ibid).

Insights from practice

The three courses can be seen as disruptive already in how they approach learning and education. All three courses choose for a radically different approach to learning than what has become normalised in universities. They take students outside the classroom, let them intimately relate to the natural world and deeply reflect who they are in relation to that world. They aim not to learn about, but in, with and through nature by embodiment and engaged interaction. Such approaches go against what is assumed as to be “academic education,” they challenge what has become normalised. The courses also aim to be “disruptive” on a personal level in that that they aim to offer transformative learning experiences, which change how students perceive (themselves in relation to) the world. This becomes clear from the formulated learning outcomes in each of the course guides:

We aim to provide students with new perspectives on nature and on themselves in the world, and reflect together on the role of humans in nature. (Course guide course 1, 2023)

The relational learning approach in which theory and practice are combined, may lead to a suite of theoretical and practical gains for participating students in their further studies and careers, including: […] a “wholesome”, more holistic and de-romanticized understanding of nature; a deconstruction of the basic human-nature divide that often underpins the destruction of nature; an increased ability to accommodate multiple ontologies; […] (Course guide course 2, 2023)

The course takes an experiential, place-based, relational approach to learning, where students are invited to explore their own place in nature as part of a community of life and how this embodied experience may benefit sustainability and personal leadership. Students will develop their own perspective on what relationality can mean in the light of environmental and societal challenges. The course also explores cultural practices that help to sustain a felt emphatic connection in the face of insecurities and losses related to unsustainability. (Course guide course 3, 2022)

The courses approach these transformative aims in different ways, but many commonalities are found in the ways of learning that aim for inner transformation. The courses build on theoretical knowledge on discomfort as crucial ingredient for change. Many of the practices in the courses are slightly uncomfortable and challenging for most students, they take them out of their comfort zones, stimulating them to embrace discomfort, to reflect upon what is considered normal and why and to challenge their own beliefs and perceptions of the world and themselves in (relation to) it. The solo vision quest mentioned earlier (Box 5; paragraph 2.2) is a good example of how initial discomfort is needed to come to transformative experiences. The students didn’t have food and water for the whole day, they were alone in an unknown place, some were initially scared and restless, but eventually the discomfort of hunger, thirst, loneliness, fear, made it possible to be with themselves, to let go of daily worries, to just be with nature, since nothing else was possible. It made them surrender to the natural world, to find comfort in that and see the world with a completely open mind and to be struck by that. Observation notes of the sharing circle after the vision quest in course 3 (2021) read:

“.. stories showed how slowing down and having true attention for the surroundings, letting the senses do the work and not worry about time, food or anything else, allowed them to truly connect to the natural world”

Many of the offered activities in the courses are intentionally designed as reflective experiences. A good example is the deep time walk,Footnote 12 practiced both in course 1 and 3 (Box 7). During the walk, students experience the evolution of the earth and are stimulated to reflect upon how human beings dominated the earth so quickly and irreversibly, while they only have existed for a split second compared to the evolution.

Box 7. The deep time walk as reflective experience

Deep time walk: […] we went on a deep time walk. 4,7 km through 4,7 billion years of time the Earth’s existence. Every step traveling a million years through time. Only about half way, the first life forms started emerging. Only in the last centimeters of the last step, human beings came into existence. We sat down next to a tree branch of about a meter we laid down on the path, representing the time that all our human history happened. It made us reflect on the insignificance of human beings in the world, though their persuasive presence. We talked about the arrogance we have as human beings to think we can own and rule this world that is carrying us and that has been here so much longer than we do. That we dare to destroy so much of its being and all life that it is carrying in just that split second of our existence. It made us feel small, humble, but also angry, sad and desperate. (Observation notes course 3, 2021)

As already became clear from previous paragraphs, all courses use methods of deep personal reflection using amongst others meditation, mindfulness and writing techniques as well as overnight stay and solo exploration in nature. Also, for all courses, students write a reflective paper in which they are invited to reflect upon their own relation to nature and how course activities have influenced that relationship.

Especially in course 3, students are invited to dive into their own emotions in relation to all that is happening in the world and to reflect upon those. Building upon the work of Joanna Macy (The work that reconnects),Footnote 13 students learn to feel gratitude for the earth that carries us, to feel supported, but also to honour the pain for the world, to feel with the world. From that, the work helps to turn feelings of fear and despair for all that is happening to the world, into a collective feeling of readiness to face challenges, to see things differently and find hope and courage to fight for all there is. This nurturing of active hope is a crucial part of all the courses, not to let students sink into hopelessness, but to feel empowered, strengthened, ready to move forward. These deep emotional reflections as well as the feeling with the world and nurturing active hope come together in one of the observations in course 3 (2021) where we went through all these emotions to collectively turn towards hope:

“We had a very emotional, moving but beautiful session today on “honoring the pain”. […] we expressed and embodied all the despair, the fear, the sadness and the anger towards all that is happening in the world. All the tears that came were acknowledged and carried by the group. It became so clear how much all that is going on in the world touches us, how it makes us feel so angry, desperate, scared and deeply sad and how that is affecting our lives. And that this is so clearly a shared feeling, a shared experience that we feel so lonely in nonetheless. A loneliness that feeds hopelessness. The sharing circle helped us not to reason from fear, despair, anger and sadness, but to turn it around into courage, longing, passion and love. It was amazing to experience how empowering and connecting it can be to turn despair into active hope.”

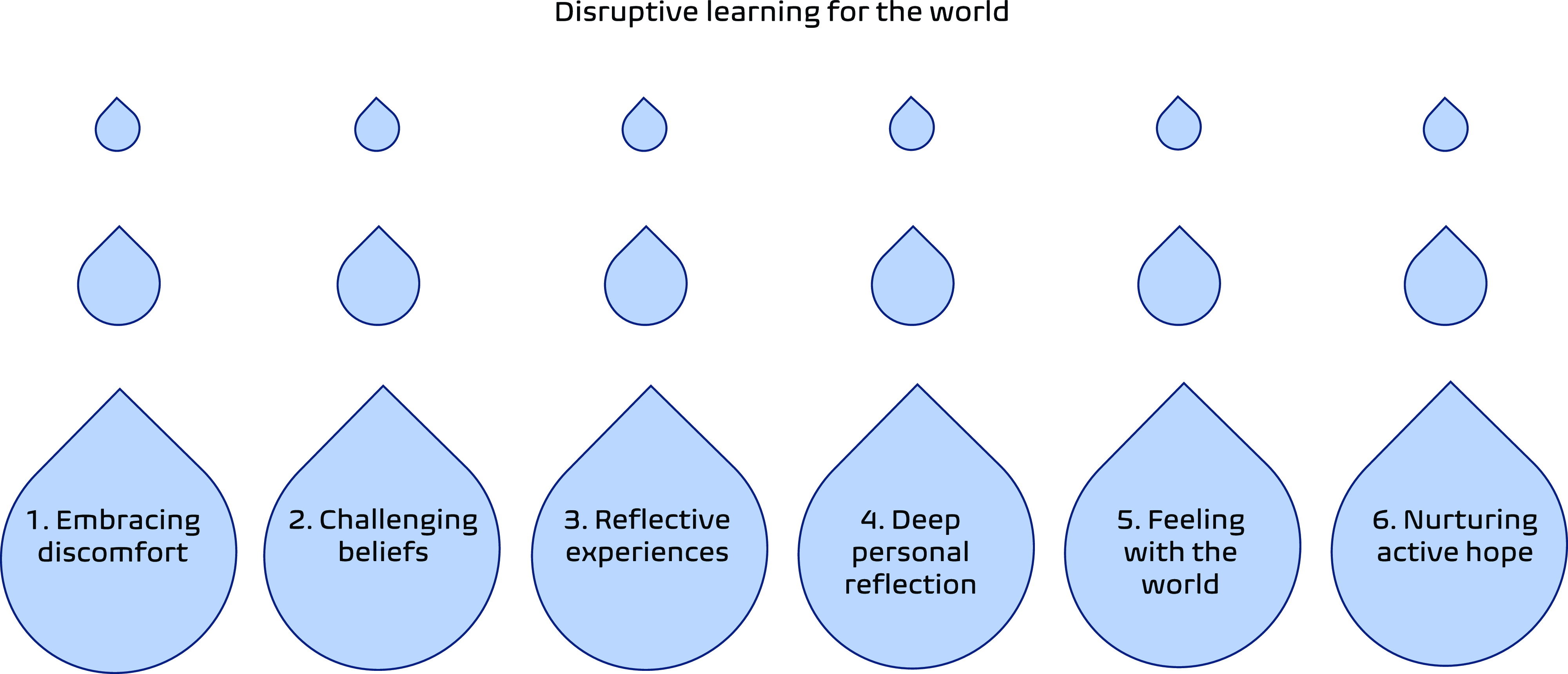

Disruptive learning for the world could be seen as an act of courage to do things radically different, but most of all as a personal journey of disrupting and rebuilding one’s own beliefs of and relations to the world, to feel the pain of the world and to turn that into a shared feeling of active hope for the future (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Drops of inspiration for relational learning with the world: embracing nature as a co-teacher.

Figure 7. Drops of inspiration for disruptive learning for the world.

Discussion

Analysis of literature and observations of practice have yielded many drops of inspiration for bringing WP from theory to practice. These drops gather in different but inevitably interconnected streams that, combined, cover four explorative areas: seeking wild and caring learning spaces; fostering learning from self-will and wonder; inviting relational learning with the world; and encouraging disruptive learning for the world. They are not meant to be criteria, prescriptions or even guidelines, but rather sensitising concepts and conversation starters that can expand or re-orient education and inspire educators. Put differently, these drops of inspiration, drawn from real life examples, provide a more concrete imagery of how theory on WP might unfold within educational practice. “Might,”, because besides nature as a co-teacher, there is the other teacher still. Creating wild, caring and disruptive learning spaces, where students can learn from self-will and wonder and where nature can truly be a co-teacher, requires specific eco-pedagogical qualities and capacities that have typically not been featured or strengthened in their professional development as teachers or educators. Getting a better sense of what these qualities and capacities are, but also the extent to which and how they can be “trained” or nurtured, are questions that would need attention in future research.

Also the understanding of wild learning spaces is a question to look into further. In this article we explored how wild learning spaces could look like. So far they are described as outdoor places. It would be interesting however to look further into whether and how WP could also be practiced in indoor environments, making them more accessible and easier to implement in mainstream education. This relates to how the concept of “wilderness” is often misconceived in the context of WP, as some far away pristine nature, only accessible to privileged students (Rose & Paisley, Reference Rose and Paisley2012). This shouldn’t have to be the case though. The notion of “wild” in WP does merely refer to spontaneous, inspiring, creative places with natural elements and to letting go of control, embracing the unexpected. If understood as such, wild pedagogies could potentially just as good be implemented in “wild” indoor environments, as was previously suggested by Weston (Reference Weston2004).

Our research serves as an exploration, an inspiration to move forward. There are many other ways of working with WP to bring about change in education and eventually in how we as humans relate to and take care of the Earth and there should be. WP are an inspiration to approach education and learning in a radically different way, they are a call for action to rethink unsustainable education practices. We have to navigate the challenges that come with a world in crisis and WP are one of many ways to work towards change, towards a more loving and caring world.

Conclusion

Exploration of both theory and practice of (1) Wild and caring learning spaces (2) Learning from self-will and wonder (3) Relational learning with the world and (4) Disruptive learning for the world as four explorative areas of wild pedagogies, has provided many drops of inspiration that together form an inspirational stream of thought for applying WP in higher education. Many drops relate to reflective practices aiming to deeply reflect upon one’s own relation to the natural world. Such deep reflections come with uneasiness, resistance and vulnerability, that are all inevitable ingredients of inner transformative change, of the ability to start seeing things radically different, to truly connect to the other-than-human world and to navigate one’s relation to that world. Attentive observation and receptivity seem to be key ingredients to make such deep transformative experiences with the world possible. It seems that deep personal experiences in and with nature, where students let go of their beliefs, slow down and open up for unexpected encounters, can bring them to experiences of deep wonder and eventually inner transformation in their relation towards the world. A safe and caring learning environment is crucial for such deep processes of personal change. Implementing the given drops of inspiration asks for teacher trainings and further exploration of what wild places for education could look like. Wild pedagogies can inspire education by their critical and radically different approach, they are a call for change that is urgently needed for a world in crisis.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all teachers who’ve been involved in the three courses, first of all for their courage and effort to go against what is considered ordinary academic education, daring to embrace nature as a co-teacher and to approach learning in a radically different way. We also thank both the teachers and the students for letting us participate in and observe and analyse the courses.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical standards

This research was performed in accordance with the Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity.

Author Biographies

Reineke Susan van Tol is PhD candidate at Wageningen University. In her work she studies the concept of Wild pedagogies, a relational outdoor learning philosophy and practice that attempts to address the complex issues related to the socio-ecological crises the Anthropocene brings us. Her work departs from a post-humanist, feminist ontological perspective, questioning the position of the human being in relation to the world and therewith offering a critical alternative for education in times of global crises. As a university lecturer she brings this work into practice, inviting students to go outside, to learn in, with, through and for nature and to reflect critically on their own being in relation to the world.

Arjen Wals is a Professor of Transformative Learning for Socio-Ecological Sustainability at the Education and Learning Sciences Group of Wageningen University in The Netherlands. He also holds the UNESCO Chair of Social Learning and Sustainable Development. He is a Visiting Professor at the Norwegian Life Sciences University and a Honorary Doctor at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. His teaching and research focus on designing learning processes and learning spaces that enable people to contribute meaningfully to sustainability. He writes a regular research blog (www.transformativelearning.nl) that signals developments in the emerging field of education, learning and capacity building for sustainability.