Introduction

Can political activism foster electoral participation? We investigate this question by examining the role of the British suffragists in promoting the electoral participation of other women. While extant research has established the role of women politicians in fostering women’s political participation (see, for example, Barnes and Burchard, Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Beaman et al., Reference Beaman, Chattopadhyay, Duflo, Pande and Topalova2009; Herrnson et al., Reference Herrnson, Lay and Stokes2003; Liu and Banaszak, Reference Liu and Banaszak2017; Reyes-Housholder, Reference Reyes-Housholder2018; Wolbrecht and Campbell, Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007, Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2017), much less is known about the role of women activists. Like politicians, activists advocate for group interests and mobilize through mass campaigns. Unlike politicians, they can be active even when women’s de jure access to formal politics is limited. Through the study of a mass-mobilization event organized by the suffragists, we uncover how women’s mass campaigning for suffrage facilitated other women’s electoral participation at a time when women politicians were virtually absent.

Building on extant theories that map the effects of women politicians and protest activism on political attitudes and participation, we argue that suffragists’ mass campaigning for the vote facilitated other women’s political socialization and thus their propensity to participate in elections later on. By mobilizing women to support the suffrage cause, campaigning for women’s political inclusion, and claiming to represent women’s collective interests, we theorize that the marching suffragists facilitated the development of women’s political resources, sense of political efficacy, and group consciousness. In doing so, the suffragists helped women to overcome the institutional, structural, and cultural barriers that largely kept women away from the polls.

The primary identification challenge is that activist networks and campaigning do not emerge randomly. In order to credibly isolate the effect of activists on electoral participation, we study a unique mass event: the 1913 Suffrage Pilgrimage. This was a nationwide march, organized by non-militant suffragists of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), in support of women’s parliamentary suffrage. It brought together local and out-of-town suffragists who reached places not previously contacted by the movement. Since women had the franchise for local elections at the time of the event, we can use a canonical difference-in-differences strategy to identify the effect of the march by comparing the change in electoral registration before and after the march between localities along the march route and others.

To measure women’s registration before and after the event, we use yearly electoral registers for the period 1911–14 in two novel ways. First, we collect individual records of the names of 20,000 individuals in the registers for a randomly selected subsample of localities. These data provide the most direct measure of women’s participation, but have limited geographic scope. We thus build a second database that lists the total number of each elector type in polling divisions across four large counties. We measure women’s registration as a relative weight of local electors – the only category where women could register – over total electors. We demonstrate the validity of this novel measure with the individual-level data and a broad range of additional tests.

We show that the march significantly increased women’s registration in both the individual and division-level samples. Next, we leverage additional data to understand who was mobilized and how. We show that the march brought new women into the movement rather than strengthened pre-existing networks. Consistent with our argument that the march mobilized through effective on-the-ground activist work, the results are only observed in the immediate vicinity of the march and are not driven by heightened media coverage. We also show that the march did not increase male registration or spur anti-suffragist societies, ruling out that its effects were driven by backlash against women.

The primary threat to inference is that the march path was strategically placed through urban, connected, and pro-suffrage places that spurred women’s registration regardless of the march. We rule out this concern by showing that the treated marched-on localities did not evolve differently before the march, thus supporting the plausibility of the identifying parallel trends assumption. Importantly, we do not find any changes in registration along non-marched-on (placebo) main routes, and show that the results hold even when restricting the sample to well-connected or rural locations. Probing key alternative explanations about why and how the march could have increased women’s participation, we refute that our results reflect activities of election campaigning and pre-existing political organizations.

Literature Review: Protest and Suffrage Activism

In this section, we review the literature on both protest and suffrage activism and outline how we contribute to both by exploring the impact of suffrage activism on women’s electoral participation.

Protest Activism

Recent scholarship shows how protests can be a powerful tool for the political empowerment of marginalized electorates. Protests have been shown to increase issue awareness, shape policy preferences, and facilitate political efficacy (Branton et al., Reference Branton, Martinez-Ebers, Carey and Matsubayashi2015; Carey Jr et al., Reference Carey, Branton and Martinez-Ebers2014; Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Zepeda-Millán and Jones-Correa2014). Civil rights protests increased the support for affirmative action among white people and decreased racial resentment against black people (Mazumder, Reference Mazumder2018). The civil rights movement largely succeeded by altering public views on race and forging collective identity among black people (Lee, Reference Lee2002, 6–7, 13; Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant1994, 98–9). However, whether protest activism also affects the electoral mobilization of marginalized electorates remains less understood.

A nascent protest scholarship suggests that protests can also shape electoral outcomes. Making protesters more sure of their case, ideologically aligned protests can further electoral polarization between groups (Pierce and Converse, Reference Pierce and Converse1990; Pop-Eleches et al., Reference Pop-Eleches, Robertson and Rosenfeld2022). Environmental protests have been shown to boost Green support (Valentim, Reference Valentim2023), black-led protests aid Democrats (Wasow, Reference Wasow2020), Tea Party rallies favor Republicans (Madestam et al., Reference Madestam, Shoag, Veuger and Yanagizawa-Drott2013), and anti-far-right protests weaken far-right backing (Ellinas and Lamprianou, Reference Ellinas and Lamprianou2024). We contribute to this research by shifting the focus from the impact of protests on how people vote to whether people engage with the electoral process in the first place. Specifically, focusing on the case of women in the early twentieth century, we examine how protest activism for suffrage helped women overcome chronic electoral disengagement.

Suffrage Activism

Suffrage scholarship identifies how suffragists contributed to securing the franchise (Banaszak, Reference Banaszak1996; McCammon et al., Reference McCammon, Campbell, Granberg and Mowery2001; Teele, Reference Teele2018). In order to pressure politicians, suffragists often leverage their ability to mobilize the public. Suffragists typically carried out mass campaigning that ranged from public speeches, meetings, and petitions to demonstrations, parades, and marches (Banaszak, Reference Banaszak1996; Graham, Reference Graham1996). However, whether suffragists’ public engagement also directly shaped women’s attitudes to politics remains less understood.

The ‘New Suffrage Scholarship’ suggests that suffragists also shaped women’s political behavior. Beyond documenting the importance of institutions for women’s turnout (Corder and Wolbrecht, Reference Corder and Wolbrecht2006, Reference Corder and Wolbrecht2016; Morgan-Collins, Reference Morgan-Collins2024), this scholarship argues that politicians leveraged strong suffragist networks to mobilize women voters (Skorge Reference Skorge2023), and even suffered electoral loss at the hands of suffragists’ electoral strategies (Morgan-Collins, Reference Morgan-Collins2021). We contribute to this research by shifting the focus from suffragists’ influence on the behavior of politicians to their impact on the behavior of women. Specifically, we examine whether modern campaigning by suffragists – beyond the well-established petitioning practices of the nineteenth century (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Popp, Resch, Schneer and Topich2018) – fostered women’s political participation independently of electoral strategies of politicians and suffragists.

Theoretical Framework: How Suffragists’ Protest Activism Spurred Women’s Electoral Participation

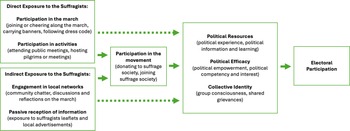

In this section, we theorize how suffragist campaigning shapes women’s electoral participation. We summarize this argument in Figure 1. We argue that the suffragists’ peaceful march for parliamentary suffrage, a prime case of suffragists’ protest activism, spurred women’s political socialization and therefore also propensity to participate in elections later on. Women at the turn of the twentieth century faced severe institutional, cultural, and structural barriers to political socialization and therefore also voting. They had limited opportunities to acquire political knowledge and experience, develop their political interest and competence, and develop group consciousness. By mobilizing women to support the suffrage cause, campaigning for women’s political inclusion, and claiming to represent their collective interests, the marching suffragists helped other women to overcome the institutional, cultural, and structural barriers that limited their propensity to engage with politics.

Figure 1. How the suffragists’ march spurred women’s electoral participation.

We outline how marching suffragists exposed women to the suffrage cause through both direct and indirect pathways (see first column in Figure 1). The march provided women with an opportunity to join the march, cheer along, or engage in political activities, such as attending or even contributing to the organization of public meetings held along the march path. In addition to providing direct opportunities for participation, the march also indirectly exposed women to the suffragists and their agenda in communities it passed through. Women who did not directly take part in the march would have still encountered the event and its message through interactions with participants in the community, suffragist leaflets, and newspaper coverage.

Regardless of whether women were exposed to suffragists’ activism directly or indirectly, the march primarily should affect women only in local, marched-on communities. Women farther from the march route had fewer opportunities to participate in the march or to receive suffragist propaganda materials. Non-local channels of influence, such as national media coverage, lacked the firsthand, personal dimension (‘happening to me or those around me’) that most powerfully shapes political behavior. Local experiences are particularly formative in shaping political attitudes (Madestam et al., Reference Madestam, Shoag, Veuger and Yanagizawa-Drott2013; Carey Jr et al., Reference Carey, Branton and Martinez-Ebers2014; Gillion and Soule, Reference Gillion and Soule2018), and face-to-face interactions, especially with those we know, are most effective in fostering political mobilization (Gerber and Green, Reference Gerber and Green2000; Huckfeldt and Sprague, Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1995).

Building on the theoretical insights from gender and protest scholarships, we identify three channels through which the direct and indirect exposure to the suffragists in local communities fostered women’s political socialization and therefore their propensity to participate in elections later on: political resources, political efficacy, and collective identity (see third column in Figure 1). Whether or not suffragists successfully mobilized women into the movement (see second column in Figure 1), the march provided opportunities to gain political experiences and knowledge, develop a sense of political empowerment, and cultivate group consciousness – ultimately boosting women’s propensity to engage in politics. In the remainder of this section, we discuss each of the three channels.

Political Resources

At the turn of the twentieth century, institutional barriers limited women’s experiences of and opportunities for political learning and knowledge (Corder and Wolbrecht, Reference Corder and Wolbrecht2016). As a result, women were less likely to vote than men, which further disincentivized politicians to mobilize the electorate ‘too costly to engage’ (Rosenstone and Hansen, Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993). We argue that the marching suffragists helped women to overcome barriers to political learning and experience. Not only suffragists had an incentive to engage this largely disengaged electorate, but, much like women politicians (Goyal, Reference Goyal2024; Reyes-Housholder, Reference Reyes-Housholder2018), the suffragists were able to lower the costs of women’s mobilization by more effectively tapping into women’s networks (Carpenter and Moore, Reference Carpenter and Moore2014).

Extant literature demonstrates that voting is a habit that people acquire over their lifetime (Dinas, Reference Dinas2012; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Green and Shachar2003). While new voters start as habitual non-voters, they can establish voting habits over time when their political resources increase (Plutzer, Reference Plutzer2002). Building on this literature, we argue that the marching suffragists facilitated the development of political resources through the expansion of suffragist organizations and support for their cause. Directly, the march provided an opportunity to gain political experience by participating in political activities or even joining a political organization. Indirectly, the march broadened opportunities for political learning through propaganda material and for political experience by participating in community-wide discussions.

Political Efficacy

At the turn of the twentieth century, cultural prejudice and expectations limited women’s sense of political empowerment, competency, and interest (Kim, Reference Kim2019). Politics was primarily perceived as a men’s game: anti-suffragists and politicians commonly referred to historic ideals of domesticity, and women as incompetent, uninterested voters (Pugh, Reference Pugh2000). We argue that the marching suffragists helped women to overcome the motivational barriers to political engagement. Much like women politicians (Beaman et al., Reference Beaman, Chattopadhyay, Duflo, Pande and Topalova2009; Liu and Banaszak, Reference Liu and Banaszak2017; Wolbrecht and Campbell, Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007; Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2017), suffragists stood as role models to other women, a proof that women were competent to engage with politics and had the power to shape it.

Extant literature demonstrates that protests can foster political efficacy (Castro and Retamal, Reference Castro and Retamal2024; Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Zepeda-Millán and Jones-Correa2014) and shape attitudinal changes (Mazumder, Reference Mazumder2018). Building on this literature, we argue that the marching suffragists facilitated the development of women’s political efficacy by campaigning for women’s political inclusion and demonstrating that women had political skills and influence. Directly, the march offered political experiences that fostered women’s sense of political empowerment and influence. Indirectly, the march sparked women’s exposure to suffragist messages challenging their portrayal as apolitical and powerless, whether through leaflets or community discussions.

Collective Identity

At the turn of the twentieth century, structural barriers impeded women’s ability to develop distinct political preferences. Women’s primary roles in the private sphere, combined with informal and formal marriage bars on women’s employment (Costa, Reference Costa2000) and politicians’ lack of attention to women’s perspectives, disincentivized women from engaging in politics (Iversen and Rosenbluth, Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006; Morgan-Collins, Reference Morgan-Collins2024). We argue that the marching suffragists helped women to overcome barriers to independent political mobilization. Much like women politicians (Atkeson, Reference Atkeson2003; Barnes and Burchard, Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Wolbrecht and Campbell, Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2017), the suffragists brought different issues to the fore, defined women’s collective grievances, improved advocacy for women, and ignited better feelings of representation.

Extant literature demonstrates that social movements can define the group as well as its interests (Morgan-Collins, Reference Morgan-Collins2021; Weldon, Reference Weldon2002), while protests can shape one’s self-reported identity (Silber Mohamed, Reference Silber Mohamed2013). Building on this literature, we argue that the marching suffragists facilitated the development of women’s collective identity by defining women’s grievances, positioning themselves as better representatives of women, and advocating for women’s political inclusion. Directly, the march provided women with an opportunity to take part in a movement that fostered narratives of women as a distinct group of voters deserving representation. Indirectly, women who did not partake in the march were exposed to women’s shared agendas through local discussion and propaganda materials.

The Great Pilgrimage

The Pilgrimage was a nationwide march organized by the NUWSS. The NUWSS was a law-abiding, and the largest, suffrage organization, reaching 496 affiliated societies and more than 50,000 paying women and men members by 1914 (Pugh, Reference Pugh2000, p. 254). The NUWSS’s peaceful tactics contrasted with the militant campaign of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) (Hume, Reference Hume2016). The Pilgrimage was to be a ‘giant advertisement’ for law-abiding suffragists, a live demonstration of widespread solidarity with the women’s suffrage cause (Crawford, Reference Crawford2001, p. 549). A great deal of attention was devoted to projecting a united and confident ‘brand’. The Common Cause (13 and 20 June 1913) asked the Pilgrims to wear the colors of the society in their hat and sash ribbons, and recommended shades of dress (black, white, gray, or navy blue) that increased the contrast with the colors of the society. A special badge for the event was also designed, and a specific song was distributed in advance.

The suffragists marched along six routes joining the ‘corners’ of England and Wales to London. The march routes were selected to maximize outreach by running along main roads that connected urban centers from the north-east, north-west, south-east, and south-west to London (see Common Cause, 16 May 1913). The march lasted six weeks in June and July 1913, culminating in a demonstration in Hyde Park with 70,000 spectators (Pugh, Reference Pugh2000, p. 279). The pilgrims, who were a mix of suffragists from far and near locations, traveled up to ten or twenty miles a day in any weather, most joining for part of the journey mostly on foot, but caravans, horses, and bicycles were also used (Robinson, Reference Robinson2018). Along the way, they carried banners, sold suffragist newspapers, distributed leaflets, placed adverts in local newspapers, held open-air and indoor meetings, and attended teas organized by local sympathizers (Crawford, Reference Crawford2001, pp. 550–3; Cartwright, Reference Cartwright2013, pp. 180–1).

The success of the Pilgrimage ignited Prime Minister Asquith to meet with a suffragist delegation (Pugh, Reference Pugh2000, p. 279). It was immensely successful in raising funds, with collections totaling £8,325, corresponding to £3.4 million in 2021 GBP using a standard historical conversion in terms of labor value, which is based on the number of hours of an average worker required to purchase each good (The Common Cause, 18 August 1913; Officer and Williamson, Reference Officer and Williamson2006). The Pilgrimage marked the beginning of a stark shift of the NUWSS away from parliamentary lobbying and petitioning to modern public tactics aimed at mobilizing women into the movement. This also brought the NUWSS closer to working-class women, engaging more with working-class issues, and ultimately helping to forge an electoral alliance with Labour (Van Wingerden, Reference Van Wingerden1999, pp. 145–8).

Data, Variables, and Empirical Strategy

In this section, we discuss case selection and data sets, explain our dependent and independent variables, and present our empirical strategy.

Case Selection and Data Sets

In order to recover women’s electoral participation in local elections, we collect three consecutive years of electoral register information finalized before the march (1911, 1912, and 1913) and one year finalized after the march (1914).Footnote 1 From these registers, we construct two complementary datasets: one at the individual and another at the division level. The individual-level data contain individual names in the register, providing a direct measure of women’s registration. However, the data must be collected by hand,Footnote 2 which increases data collection costs. The inevitably limited number of locations gathered then restricts generalizability and internal validity, limiting the examination of location-specific inference threats such as urbanization. The division-level data expand the geographical scope but only provide division-level aggregate data. In these aggregates, gender is not directly observed, so we rely on a proxy to capture the change in women’s registration. We outline the case selection procedures below. Additional information is given in Appendix Section C. Appendix Figure C.3 compares the coverage, level, and variables in these databases.

Selecting individual-level datasets

This dataset gathers individual-level records that name each registered elector. We randomly select 20 parishes in the West Riding of Yorkshire (WRY) for the years 1911 and 1914, totaling 20,000 individual records, 4,000 of which are local electors only. We select the WRY because it is a large county with a significant coverage of the march, and because it presents smaller geographical units (parishes), which improves the cost-efficiency of collecting more localities. We randomly select treated locations along the march path and control ones along main (Roman) roads linking York to Manchester in order to improve comparability between treatment and control, as both sets of locations are connected to urban centers.

Selecting division-level datasets

This dataset gathers the summary pages in the electoral records for four consecutive years (1911–14) in four counties. While electoral registers are available for all counties, only four counties include the summary pages necessary to collect division-level aggregates. The four counties are Gloucestershire, Norfolk, Surrey, and the West Riding of Yorkshire, and altogether total about fourteen per cent of the English population, total nineteen per cent of the eligible electorate in 1910, and represent distinct electoral and occupational contexts. Compared to England, the four counties lean slightly more Liberal, have a slightly lower turnout, have a higher population density, and are less agricultural (see Appendix Table B.1 for further description).Footnote 3

Variables

We now turn to explaining our dependent and independent variables. Appendix section C provides further details on sources and collection procedures.

Electoral registration

We study the electoral registration of women who were already eligible to vote in local elections.Footnote 4 , Footnote 5 In the individual-level data set, we measure women’s registration with a binary indicator of a local elector being a woman. In the division-level data set, we proxy women’s registration as the share of local electors – the only category of electors where women could register – over total electors (local only, parliamentary only, local and parliamentary) at the polling division level.Footnote 6 That is, we use a proportion measure of women’s registration that captures the weight of the only category that allowed women compared to the overall mass of registered electors.Footnote 7

March path

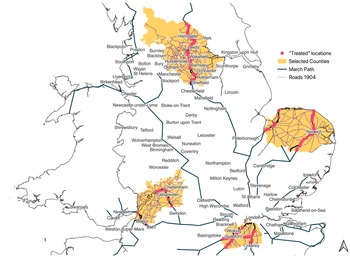

Our independent variable measures proximity to the march. To construct it, we recover the names of all cities and towns scheduled for visit by the NUWSS from an original map (Appendix Figure C.1). We establish the path between those cities using the main historical roads connecting these locations. Our preferred definition of treated divisions intersected by the march is within one kilometer of Euclidean distance from the centroid of the division to the closest point of the march.Footnote 8 This range captures localities where people most certainly experienced the march in person. In total, our individual-level sample identifies ten divisions intersected by the march and ten control divisions outside the path’s one kilometer range. Our division-level sample contains sixty-two divisions intersected by the march and 968 divisions that were not intersected within one kilometer. Figure 2 and Appendix Figure C.1 present the path of the march and mark the four selected counties and treated divisions. Appendix Figure C.2 then zooms on the parishes that were randomly selected for the individual-level analysis.

Figure 2. Map of the march and data availability at the division level.

Note: March path in sampled counties is along main roads connecting stopping points and along straight lines outside the sample (see Appendix Figure C.1 for stopping points).

Control variables

We include a battery of division-level control variables in both individual and division-level analyses. We use data from the 1911 census to indicate demographic characteristics of polling divisions, including population and age by gender, and indicators on fertility, marriage, and child mortality. We also account for the socio-economic structure of the population, namely the share of the male population belonging to five out of six social class categories defined by the standard historical international social class scheme (HISCLASS). Finally, we account for distance to the nearest city and distance to the nearest main road.

Summary statistics

Table 1 compares treated and control divisions. In the individual-level data, the share of local electors (the only category allowing women) before the march was twenty-three per cent in the control group and thirteen per cent in the treated group. The average electorate size is roughly twice as large in the control group than in the marched-on divisions, reflecting the fact that the control group in the individual-level data set was drawn from along main roads orthogonal to the march path. The share of women among local electors is high (sixty per cent), as expected, in the treatment group.

Table 1. Summary statistics: individual and division-level analysis

In the division-level data, the share of local electors before the march is nearly identical to the one observed in the individual-level sample in the treatment group, and roughly one standard deviation lower than in the individual-level data set in the control group. The marched-on divisions’ electorate size is on average twice as large as that of others, reflecting a higher concentration of men eligible to vote in urban locations along the march path.

The summary statistics on control variables in the four sampled counties are also consistent with the expectation that the suffragists marched through urban and connected places (Appendix Table C.1). Divisions intersected by the march were on average larger and closer to main roads; had lower fertility rates; and higher female celibacy rates, age at marriage, women’s share of population, and share of married women working. In the next section, we outline how our causal empirical strategy, along with several additional tests, overcomes concerns stemming from these differences.

Empirical Strategy

Our goal is to estimate the effect of suffragists’ campaigning activities on other women’s mobilization. The common estimation challenge is that campaigning is not randomly assigned. Women’s mobilization typically enabled suffragists’ networks, and suffragists targeted campaigns in urban and connected places where women were more likely to be already mobilized. Therefore, any correlation between campaigning activities and women’s mobilization may capture confounders such as urbanization or socio-economic characteristics. We overcome this challenge in two ways. First, by focusing on one large-scale campaigning event in combination with the use of yearly electoral registers, we can run a differences-in-differences estimation. That is, we can compare the change in trends in women’s registrations before and after the event, between marched-on and control localities. The identifying assumption is that trends in these two groups would have been parallel in the absence of the Pilgrimage, conditional on controls. As standard, we probe the validity of the parallel trends assumption by testing pre-trends and with a battery of additional tests. Second, the march was unique in that, by connecting urban centers, it brought suffragists into less-connected localities along the way that were not typically within the reach of suffrage campaigning. This allows us to assess the impact of the march outside of urban and pro-suffrage locations.

We run the following difference-in-differences specification. The treatment group encompasses all polling divisions within one kilometer of the march. The control group consists of all other divisions. Equation (1) describes our baseline specification, which we estimate using ordinary least squares (OLS):

$${y_{ktp(k)}} = \beta {\rm{Marc}}{{\rm{h}}_{p(k)}}{\rm{Pos}}{{\rm{t}}_t} + \gamma {\rm{Marc}}{{\rm{h}}_{p(k)}} + \delta {\rm{Pos}}{{\rm{t}}_t} + {{\bf{X}}^\prime }_p{\gamma }{\;_t} + {\eta _{c(p)}} + {\varepsilon _{pt}};\quad k \in \{ i,p\} .$$

$${y_{ktp(k)}} = \beta {\rm{Marc}}{{\rm{h}}_{p(k)}}{\rm{Pos}}{{\rm{t}}_t} + \gamma {\rm{Marc}}{{\rm{h}}_{p(k)}} + \delta {\rm{Pos}}{{\rm{t}}_t} + {{\bf{X}}^\prime }_p{\gamma }{\;_t} + {\eta _{c(p)}} + {\varepsilon _{pt}};\quad k \in \{ i,p\} .$$

The unit of observation k is either the individual i (individual-level analysis) or the polling division p (division-level analysis), for every year t ∈ {1911 − 14}. Marchp(k) is a binary variable equal to 1 if division p is in the treatment group. Postt is a binary variable equal to one for year t after the march, and Marchp × Postt is the interaction between the two terms. The parameter of interest is β; it captures how the march changed the trends of the outcome after 1913, in marched-on divisions compared to the control group. In the individual level analysis (k = i), the outcome y itp(i) is a binary variable flagging if individual i in division p(i) at time t is a woman. In the division-level analysis (k = p), the outcome y pt is the share of local electors over the total number of registered electors in division p in year t.

In all our models, we include a vector of socio-economic, demographic, and distance controls

![]() ${\bf X}_{p}^{'}$

from 1911 census, as presented in Appendix Table C.1. For more flexible specification, we interact all controls with the Postt

variable, accounting for time-varying effects of the controls. In the division-level data set, we also include fixed effects η

c(p) for all counties c and cluster standard errors at the parliamentary division level.

${\bf X}_{p}^{'}$

from 1911 census, as presented in Appendix Table C.1. For more flexible specification, we interact all controls with the Postt

variable, accounting for time-varying effects of the controls. In the division-level data set, we also include fixed effects η

c(p) for all counties c and cluster standard errors at the parliamentary division level.

Results

In this section, we first present our baseline estimates using the individual-level dataset and the validation exercise for our proxy of women’s registration used in the division-level dataset. We then present results from the division-level analysis to show how the march shaped the share of local electors (the only category that allowed women) and parliamentary electors (a category only allowing men). We conclude by probing the mechanisms that drive the main effects.

Individual-Level Analysis

Table 2 (Models 2 and 3) presents the baseline estimates from our individual-level analysis. Consistent with our expectations, the march narrowed the difference between women’s and men’s registration between treated and control divisions. Model (3) presents the estimate of interest (β̂) with a full battery of controls, revealing that the probability that a registered local elector is a woman significantly rose by 3.7 percentage points in marched-on divisions relative to others. This is sizable (6.7 per cent of the outcome mean), despite only reflecting reactions a few months after the march and the likelihood of attenuation bias from measurement error due to using historical records.

Table 2. Baseline effects of the march on the probability of a female registered elector

Note: *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01; OLS estimates; unit of observation is polling division in column (1) and the individual in columns (2) and (3); standard errors clustered at the parliamentary division level.

The estimates presented in Table 2 cover a geographically narrow area, thereby limiting options for sensitivity analysis. We therefore expand the data coverage using division-level data and develop a novel proxy of woman’s registration: the share of local electors, the only category where women could register, over the total electorate. To validate this proxy, we check the correlation between the growth in the share of local electors and that of women among local electors in the individual-level data. The results, presented in Table 2 (Model (1), show a correlation coefficient close to, but less than, one, suggesting that the division-level analysis is likely to provide a conservative (lower bound) estimate in the change of women’s registration.

Division-Level Analysis

We present our baseline results in Table 3. Consistent with the descriptive patterns from Table 1, the march narrowed the difference between divisions on and outside of its path. Divisions exposed by the march saw a significant increase in the share of local voters by about 1.3–1.5 percentage points compared to those not intersected by the march (Models 1–5). This represents approximately eight to nine per cent of the average outcome. The estimates are stable after including the full battery of controls (Models 1 and 2), excluding the year of the treatment (Model 3), focusing on the year before and after the 1913 march (Model 4), or excluding divisions with a population above 15,000 and close to roadsFootnote 9 (Model 5).

Table 3. Baseline effects of the march on the share of local electors

Note: *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01; OLS estimates; unit of observation is polling division; standard errors clustered at the parliamentary division level; outcome is share of local electors over total electors registered; Appendix Table D.1 shows the estimates for all the control variables.

The baseline estimates are comparable in sizes to the individual-level estimates and to those from similar research. They are of the same order of magnitude as those estimated by Larreboure and Gonzales (Reference Larreboure and Gonzales2021), who study the Women’s March of 2017 in the United States using a similar empirical strategy. Further, our baseline estimates of eight to nine per cent of outcome mean are within the typical range for Get-Out-To-Vote (GOTV) experiments. For example, Gerber and Green (Reference Gerber and Green2000) estimate a roughly eighteen per cent of the mean outcome for direct canvasing and 1.3 per cent for mail-only canvasing, while Braconnier et al. (Reference Braconnier, Dormagen and Pons2017) estimates that canvasing increases registration by approximately fourteen per cent of the mean.

We run our baseline regression with a different outcome that captures men’s propensity to register, defined as the share of parliamentary electors (a category only allowing men) over the total population of men. The estimates, presented in Table 4, do not show any significant treatment effect on this share of parliamentary electors, suggesting that men did not react to the event. Men exposed to the march did not counter-mobilize as a form of backlash to women’s mobilization, nor were they were spurred to political action alongside women. This provides further evidence aligned with our theory that the march primarily boosted women’s political socialization, and therefore also narrowed the percentage point gap between women’s and men’s registration.

Table 4. The effect of the march on men

Note: *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01; OLS estimates; unit of observation is polling division; standard errors clustered the parliamentary division level; outcome is share of parliamentary (men only) electors over total population of men.

We run our baseline regression with different treatments using buffers of varying Euclidean distances from the centroid of the division to the closest point of the march. The effects are meaningful in magnitude only for divisions very close to the march, up to about two kilometers from the march (see Figure 3). In other words, the march enhanced women’s political socialization in places where reaching the march was relatively effortless (less than half an hour’s walk). In these locations, women arguably got a first-hand experience of the campaigns either directly or indirectly through community chatter. Media coverage of the march, such as through local newspapers, would have traveled longer distances.Footnote 10

Figure 3. The effects of the march using different treatment definitions.

Note: Plots the coefficient of interest β, defined using different distance buffers; ninety per cent and ninety-five per cent CIs; standard errors clustered at the parliamentary division level, using Model 2 in Table 3.

Mechanisms: who was mobilized by the march?

The theoretical framework above outlines the channels through which the march fostered women’s political socialization, which may or may not have included recruitment of women into suffrage societies. The march may have primarily mobilized women by bringing new women into the movement, or the exposure to suffragists along the march path may have reinvigorated existing suffragists networks (see second column in Figure 1). In this section, we leverage rich data on NUWSS societies and meetings to assess which women were most likely mobilized by the march. We find evidence consistent with the march primarily mobilizing new women into the suffrage movement rather than reinvigorating women already in the movement.

First, we probe whether the march mobilized new women into the suffrage movement. To do so, we trace the establishment of NUWSS suffrage societies for all divisions across the nation for the period just prior the Pilgrimage and right after it for an entire country (373 societies in the first quarter of 1913 and 451 in that of 1914; see map in Appendix Figure D.1). The results suggest that marched-on localities have seen a 2.3 percentage point increase in the probability that a new suffrage society opened in 1914 compared to 1913 (Models 1 and 2, Appendix Table D.3).Footnote 11

Second, we probe whether the march reinvigorated the activity of pre-existing local suffrage societies. To do so, we collect and geocode data on weekly meetings organized by suffrage societies that were in operation prior to the march across the nation (432 meetings organized in January and February 1913 and 1914, a period that excludes meetings too close to the march organized to prepare and debrief the march). The results suggest that marched-on localities did not see more meetings organized by pre-existing suffrage societies after the march (Appendix Figure D.2).

Threats to Inference

We identify two key threats to inference of our baseline empirical strategy. The first threat is that our results are driven by unobserved confounders rather than the march itself. Another threat to inference is that our results are driven by the march, but reflect mobilization spurred by politicians’ campaigns or the campaigns of other political organizations who exploited the march. In this section, we address these two concerns and conclude the probing robustness of our baseline results to alternative variable definitions, specifications, and standard errors.

Threat 1: Unobserved Confounders

In this section, we address the concern that our results are driven by unobserved confounders compromising the assumption of parallel trends. The main issue is that local electors may have increased in the marched-on divisions for reasons unrelated to the march, in particular because suffragists selected the march path to maximize outreach by connecting urban centers along main roads. We rule out this concern with multiple tests. First, we show that the outcome did not evolve differently in marched-on and control localities before the march (absence of pre-trends), which supports the identifying assumption. Second, we show that the results are, if anything, larger in rural localities and robust to placebo control group with high connectivity (along main roads not on the march path), providing reassurance that urbanization and connectivity do not explain away our findings.

Parallel trends assumption

To provide evidence on the plausibility of the parallel trends assumption, we analyze the raw evolution of the average share of local electors (see Appendix Figure E.1), and run pre-trends tests accounting for the full battery of controls and fixed effects (see Appendix Figure E.2). Control locations had on average higher shares prior to 1913, but with minimal fluctuations in the gap. The gap, however, significantly shrinks between 1913 and 1914. The pre-trends tests confirm that, referencing 1913, treated locations are not significantly different in 1911 and 1913, whereas a positive significant difference appears in 1914. These two tests together provide support for the plausibility of the parallel trends assumption.

Urbanization

We interact our treatment with a binary variable flagging urban centers. We define urban centers as divisions with a population of about 15,000 inhabitants, which represents roughly the twenty per cent largest treated divisions and the five per cent largest overall. We show that this interaction does not establish a significant pattern (Appendix Table E.1). Although statistically insignificant, if anything, the impact of the march was stronger in more rural, remote localities where the suffragists were a novelty. These results cast doubts on the possibility that unobserved confounders linked to urbanization explain away our estimates (for example, urban places experiencing other triggers of mobilization at the time of the march).

Connectivity

We run two tests that use main roads connecting main urban centers through a different axis than the suffragists’ path to London (predominantly Roman roads).Footnote 12 First, we use these alternative roads as a placebo treatment. We show that localities along these alternative roads that were connected but did not experience the march did not exhibit meaningful or significant effects on the share of local voters (Appendix Table E.2). Second, we use these alternative roads as an alternative control group. We show robustness of our results to an alternative control group drawn only from divisions along the alternative roads (Appendix Table E.3, Model 6). Despite the sample size being smaller (n = 387), the precision increases and the estimates are also roughly doubled in magnitude, suggesting that the baseline results could be conservative estimates. Taken together, these results cast doubts on the possibility that our results are driven by unobserved confounders linked to connectivity (for example, connected places experiencing other triggers of mobilization at the time of the march).

Threat 2: Alternative Explanations

In this section, we probe whether our results were driven by the march, but not necessarily by the suffragists. In particular, if registration had increased because other political organizations, politicians, or journalists exploited the march for their goals, the march would be driving the effects for reasons other than those theorized. Below, we rule out the main alternative explanations that our baseline results reflect mobilization of anti-suffragist organizations, workers’ organizations, election-seeking politicians, or newspaper activity.

Counter-mobilization of anti-suffragists

A potential concern is that the march spurred women’s registration because of counter-activities of anti-suffragists along the march path. Women may have just been reacting – positively or negatively – to anti-suffragist protests. To rule out this possibility, we conduct a horserace exercise comparing two treatments in the same model: proximity to march and proximity to an anti-suffragists society (Appendix Table F.1). We find no significant effect of proximity to an anti-suffrage society, leaving the baseline treatment effects of the march unchanged. Second, the interaction term between the treatment effect of the march and proximity to anti-suffragists is negative and significant at conventional levels, showing that the mobilizing effects of the march are negated (not accounted for) by the anti-suffragists. Altogether, these two tests provide reassurance that the baseline results are not driven by counter-mobilization of anti-suffragists.

Activation of workers’ organizations

Another potential concern is that the march spurred women’s registration because it reinvigorated other political organizations along the march path. The most common organizations joining the march were workers’ associations. To rule out this possibility, we digitize data on the location of strike events in 1913 prior to the marchFootnote 13 and conduct another horserace exercise (Appendix Table F.2). We find no significant effect of proximity to strike events, leaving the baseline treatment effects of the march unchanged. If anything, strikes are negatively associated with the share of local electors over total electors – the opposite of what we would expect if workers’ mobilization accounted for our results. Second, the effect of the march does not depend on the proximity to a strike event: the interaction term between the treatment effect of the march and proximity to a strike activity is not significant. The direction and magnitude of the triple interaction term suggests that, if anything, strike events negate the mobilizing effects of the march. Altogether, these two tests provide reassurance that our results are not driven by a reinvigoration of workers’ organizations.

Election campaigns of politicians

Yet another potential concern is that politicians may have exploited the march to campaign for upcoming election, potentially driving the increase in women’s registration. This seems unlikely as local elections at the turn of the twentieth century were mainly non-partisan and unopposed (see, for example, Ottewill (Reference Ottewill2004) on Guilford; Jones (Reference Jones1969), ch.2 on Wolverhampton). Moreover, there were no parliamentary elections taking place during the period of study (1911–14). We nonetheless probe this concern by examining the calendar for local elections and verify it with election mentions in local newspapers. Out of five local elections (county, parish, rural districts, urban districts, and municipal borough councils), only one (rural districts) could potentially contaminate our results because they took place after the march. However, these elections only elected a third of councilors, would have been often uncontested, and took place in an off-election year. As such, this election produced relatively few newspaper mentions (see Appendix Figure F.1). For a full discussion of the election calendar and newspaper mentions, see Appendix F.3.

Heightened media coverage

Finally, a potential concern is that the march may have mobilized women through heightened media attention (both positive and negative) to the suffragists’ agenda, rather than the localized suffragists’ activities along the march path. To probe this concern, we collect and geocode data on newspaper coverage of the march (23,331 articles identified in the British Newspaper Archive with keywords ‘Women’ AND ‘March’ between January 1913 and January 1914). While marched-on locations experienced increased media coverage at the time of the march (Appendix Figure F.4), we find no evidence that media exposure drives our results (Appendix Table F.3).Footnote 14 This provides reassurance that our results do not reflect information dissemination via heightened media coverage of the march.

Robustness Checks

Dependent variable

We validate the share of local electors as a division-level proxy capturing changes in women’s registration using the individual-level data (see section ‘Individual Level Analysis’). To further support this proxy, we demonstrate that the division-level results depend on the expected size of the potential women electorate. Given that married and poor women faced more restrictions to registration, we proxy the potential pool of eligible women with three indicators flagging above median shares of: (i) never-married women, (ii) single-person households (this category is preferred to the former one since it also includes widowed women), and the interaction of these two variables with a higher share of upper-class individuals. In line with our expectation, we find that the march-on-registration effects are substantially higher in those flagged locations (see Appendix Tables G.1, G.2, G.3, and G.4).

Specification

We show robustness of the baseline results to alternative specifications. First, the inclusion of polling division fixed effects. Although these absorb all division-level time-invarying confounders, this specification is prone to attenuation bias (Appendix Table G.5; estimates are attenuated as expected, see Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009, pp. 225–6). Second, we verify that the results hold after we individually drop counties, eliminating the concern that our results are driven by a single county (see Appendix Table G.6).

Standard errors

Our control group is substantially larger than the treatment group, potentially lowering standard errors. Reassuringly, restricting the size of the control group to divisions along main roads (see Appendix section E.3) actually yields larger and more precise estimates (see Appendix Figure G.1). As a further check on the standard errors, we verify robustness to alternative clusterings. Our baseline results are unaffected if we: cluster using arbitrary clustering units of varying sizes, addressing concerns of spatial correlation (Appendix Figure G.1); use wild cluster bootstrapping (Appendix Table G.7); or cluster at the level of the treatment and the county (Appendix Table G.8).

Discussion

Through the study of the first English women voters, this paper expands our understanding of how women were incorporated into the electoral process. Previous research documents that suffragists fostered women’s participation by disseminating information during elections and enabled politicians to better mobilize women voters (Morgan-Collins, Reference Morgan-Collins2021; Skorge Reference Skorge2023). In this paper, we uncover how the act of enlarging suffragists’ support networks in the fight for suffrage – not a direct suffragists’ or politicians’ electoral strategy – facilitated the political socialization of the first enfranchised women. Our finding, which ultimately uncovers how the the first, mostly privileged, women voters were mobilized, is likely to bear significance for our understanding of how all women, including working class women, secured better representation. The history of Western suffrage movements suggests that middle-class women, once enfranchised, often supported suffrage for all women, legislation to protect women workers, and even mobilized working-class women into politics (Evans, Reference Evans2012).

One question that remains open is the generalizability of our findings in time, in space, and across groups. While the lack of electoral registers after 1914 prevents us from examining the long-term effects of the march, it seems very plausible that the experience of voting once would have facilitated women’s participating in the future by establishing participatory habits. A quick glance on suffrage movements in other countries suggests that our findings are generalizable beyond the UK and beyond women’s movements. Suffragists in other countries typically employed a vast array of similar campaigning strategies, such as peaceful parades, protests, and petitions (Banaszak, Reference Banaszak1996). This is also typically the case for other organized demands for suffrage, including the Civil Rights movement in the United States or the working-class movement for men’s suffrage in Europe.

Finally, our study has important implications for modern women’s representation. Our findings imply that women’s protest activism has the potential to improve women’s substantive representation not only by enhancing women’s electability (Larreboure and Gonzales, Reference Larreboure and Gonzales2021) but also by enhancing women’s electoral participation. This voter-level pathway to representation seems especially important for today’s women’s representation. Beyond the fact that women continue to face barriers to electability across the globe, the collective nature of women’s organizations provides an opportunity to mobilize and represent a wider population of women (Weldon, Reference Weldon2002). An effective mobilization into women’s organizations can thus have the potential to empower women across the globe even today.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425100653.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this paper can be found in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TUH3IB

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people for the valuable comments they provided to our paper: Julia Cagé, Matthias Dilling, James Fenske, Diana O’Brien, Jennifer Piscopo, Anna Gwiazda, Barbara Piotrowska, Raluca Pahontu, Daniel Seidmann, Cecilia Testa, Dario Tortarolo, Ekatherina Zhuravskaya; participants at the Cage 2022 Economic History Workshop, PolEconUK 2023 workshop, the Sciences-Po Liepp 2023 ‘Women in Politics’ Workshop, and the 2024 Birmingham Economic History Workshop; seminar participants at City University London, Carlos III Madrid, KCL, and the Universities of Essex, Oxford and York; and participants at APSA, CES, EHS, and NICEP conferences. We would like to thank Anita Braga, Erin Brady, Florencia Buccari, Yifei Chen, Sarah Crowe, Alejandro Pérez-Portocarrero, Ridwan Prasetyo, Emma Rogers, Ahan Thakur, and Marcelo Woo for excellent research assistance; Joseph Day and CAMPOP for sharing data with us; and the team at the West Yorkshire Archive service in Wakefield for their outstanding support during the pandemic.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council, grant number ES/T01394X/1, ‘From Suffrage to Representation’ and British Academy/Leverhulme Small Research Grant, grant number SRG20\200729.

Competing interests

None to declare.