Modernity serves as an overarching term for the social, economic, and cultural changes brought about by the scientific and technological innovations of what is commonly called ‘industrial revolution’. Undoubtedly, people in the early twentieth century, especially those living in large cities, acquired a strong sense of being part of a modern age, and this term signified more than a simple chronological distinction between past and present. Jose Harris emphasizes that a perception of modernity pervaded mental life:

the consciousness of living in a new age, a new material context, and a form of society totally different from anything that had ever occurred before was by the turn of the century so widespread as to constitute a genuine and distinctive element in the mental culture of the period.Footnote 1

The term ‘modern’ had been used previously to contrast the ‘classical’ period with more recent times, but it had now come to mean contemporary life with its many social, scientific, and technological changes. Accounts of how modernity affected the arts frequently draw connections with the aesthetics of modernism. In Vienna, that would entail references to painters such as Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, and composers such as Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg. The concept of the modern was broader than this, however, and included all new developments that had produced marked effects on social and cultural life.

Contemporary life was rarely depicted in operetta and opera of the nineteenth century, although Offenbach’s La Vie parisienne and Verdi’s La traviata were notable exceptions.Footnote 2 In the early twentieth century, operetta frequently engaged with everyday life, and related to features of modernity such as trains (The Girl in the Train, The Blue Train), planes (Little Boy Blue,Footnote 3 Love and Laughter), factories (Eva), cinemas (The Girl on the Film, The Cinema Star), and cars (The Girl in the Taxi, The Joy-Ride Lady). Contemporary settings are also found in the Zeitoper of the Weimar Republic period, which shared some features characteristic of operetta. Ernst Krenek’s Jonny spielt auf (1927), one of the best-known examples, references jazz idioms but is closer to modernism in musical style than is operetta. With the exception of Max Brand’s Maschinist Hopkins, Zeitoper tended towards comedy (though mixed with satire), but the term remained vague and in Kurt Weill’s opinion moved rapidly from concept to slogan (Schlagwort).Footnote 4

Paul Lincke’s Frau Luna of 1899 was, in its fantasy, comic characters, and high-spirited music, far closer to Offenbach’s opéra-féerie Le Voyage dans la lune (1875) than to Die lustige Witwe. However, it did engage in several ways with modernity. It envisaged a new technologically advanced era: one scene, for example, had workers making electric lights. The German officer’s desire to annex the moon for Prussia was both a satire of militarism and a foreshadowing of troubled times to come. It was the first notable operetta from Berlin, a city that embraced modernity and was soon welcoming operettas on modern life. The London version, Castles in the Air, produced at the Scala Theatre in 1911, was given a modern context by being preceded by Charles Urban’s ‘Kinemacolor’, a development in early cinema.

Die lustige Witwe staged a clash between the values of feudal Pontevedro and the capitalist metropolis Paris. Moritz Csáky remarks that, for the Viennese audience, Pontevedro (recognized as Montenegro) represented ‘a backward country’ in which quasi-absolutist, pre-modern conditions prevailed.Footnote 5 The articulation of modern values was made more explicit in Lehár’s Mitislaw der Moderne, composed in 1907 for the Hölle cabaret in the basement of the Theater an der Wien. This one-act operetta reintroduces Danilo, as well as dancers from Maxim’s. One of its numbers, ‘Sei modern’ (‘Be Modern’), asserts that modernity is exciting and fashionable.Footnote 6

| Sei modern, mein Sohn, modern, | Be modern, my son, modern, |

| Denn das hat man heute gern | For it pleases people today, |

| Sei modern vom Glockenrock | Be modern from your flared jacket |

| Bis zum dünnen Silberstock | To your thin silver cane; |

| Sei modern auch von Moral | Be modern in morals, too, |

| Liebe dreizehn auf einmal | Love thirteen at once, |

| Sei modern, sei immer jung | Be modern, be ever young, |

| Denn das hat Chique, hat Schmiss, hat Schwung! | For it’s chic, lively, and energetic! |

In Oscar Straus’s burlesque operetta Die lustigen Nibelungen (1904), Siegfried, in addition to having a proud name, lays claim to the possession of modern chic in his song, ‘So war’s bei den Germanen’. Dapper modernity certainly needs to be distinguished from the earnest artistic movement labelled ‘modernism’. Silver-age operetta was assuredly modern (like jazz and new styles of ballroom dancing), but it was not modernist. Modernism was associated with aesthetic ‘advances’ in style. In music, this meant greater complexity in harmony and rhythm, driven by the conviction that music was evolving like some kind of organism. Yet, for all its purported advances and embrace of artistic autonomy, modernism is less likely to be perceived today as progressive in a social sense. One has only to consider that three common targets of early modernists were women, Jews, and ordinary working people (disdained as the ‘masses’).Footnote 7

Die lustige Witwe was perceived as a modern operetta that broke with Viennese tradition. This was recognized by Lehár’s first biographer, Ernst Decsay.Footnote 8 Stefan Frey, however, is careful to point out that its modernity is to be understood in social rather than aesthetic terms, in its depiction of scenes from modern life.Footnote 9 Danilo and Hanna are not a typical romantic young couple, and are not contrasted with a vulgar buffo couple, but with Camille and Valencienne, both of whom have social standing (even if Valencienne treats social respectability ironically). Maxim’s restaurant, the setting of Act 3, had been founded by Maxime Gaillard in Paris just twelve years before the operetta’s premiere, and was indisputably modern with its cosmopolitan art nouveau interior (it is still standing at 3 rue Royale). In distinguishing between modern and modernist as these terms apply to the social and to the aesthetic, my intention is not to suggest that Lehár’s music was not thought modern: indeed, a critic in 1906 found the music ‘more modern than Viennese’.Footnote 10 A distinction between the social and aesthetic is necessary in order to distinguish this kind of popular modernity from the musical modernism cultivated by contemporary composers such as Richard Strauss and Arnold Schoenberg. Peter Bailey has used the phrase ‘popular modernism’ to describe theatrical entertainment that engaged with modernity but was ‘less concerned with breaking down the structures of modernity than coming to terms with them’.Footnote 11 Adorno, in January 1934 writes of ‘der veralteten Moderne der lustigen Witwe’ (‘the outdated modernity of The Merry Widow’). Although he perceives the modern of the early century as outdated, his comment acknowledges that Die lustige Witwe was once a modern, if not modernist, stage work.Footnote 12 It does not mean that, from this stage work on, all operettas embraced modernity – an immediate exception was Die Försterchristl of 1907. It does not mean, either, that critics never imagined musical modernism might make its way into an operetta score. In fact, a reviewer of Lehár’s Eva on Broadway declared: ‘Eva says “Yes” in the first act to discords that Schoenberg might have been proud to have written’.Footnote 13

Familiar objects of the modern age that members of the audience might either possess or desire feature often on stage. In the first scene of The Chocolate Soldier, set in Bulgaria, 1885–86, there is an ‘electric reading lamp’ on the bedside table. In the finale of Act 1 of The Girl in the Taxi, René enters carrying a ‘pocket electric lantern’. A more common modern functional object was the typewriter. It appears in The Dollar Princess, and the cast of The Girl on the Film includes eight ‘Typewriting Girls’. The latter, as may be guessed, also includes examples of modern work opportunities in the shape of six cinema actresses. In addition, the cast includes eight ‘rather more stylishly dressed actresses and four actors’.Footnote 14 Clearly, the low artistic status of film at this time meant that stage actors were perceived as more stylish. Films were part of the technological advance of modernity, even if they were for many years more conservative than operetta in representing women. In 1932, Siegfried Kracauer wrote that working women who appeared in popular film had previously been pretty young secretaries or typists who end up marrying the boss, but increasing tension between reality and illusion meant that women in the audience were no longer easily enchanted by this.Footnote 15 With the advent of radio, it was not long before a wireless set appeared on stage. The one used in Act 2, scene 2, of Straus’s Mother of Pearl was supplied by McMichael Radio of the Strand, who advertised in the programme that their radio equipment would be used by Mount Everist Expedition members for receiving weather reports.Footnote 16

Communications technology was improving and speeding up booking processes for theatre patrons. Guglielmo Marconi’s wireless telegraphy transmissions (begun in 1897) led to a regular transatlantic radio-telegraph service in 1907. Daly’s Theatre was the first to receive a seat booking via ‘Marconigram’.Footnote 17 The telephone enabled efficient booking of tickets. Private telephone lines in the 1920s meant that the Keith Prowse ticket agency could promise their customers that they would be able to book the seats they wanted at any of their many branches. Several of the firm’s branches had 5 telephone lines, and the branch in New Bond Street had 12 lines.Footnote 18 For those choosing to listen to the music of operetta at home, technology was changing that experience, too. With the development of microphone technology, location recordings became possible that could then be played on the gramophone. The Columbia records of The Blue Train were advertised as being ‘actually recorded in the Prince of Wales Theatre’.Footnote 19 Other developments in communications media were discussed in the Chapter 6.

American Capitalism and Dollar Princesses

The modernity of Die Dollarprinzessin was most striking in its American orientation; the transatlantic gaze was characteristic of a modern sensibility. Yet the dramatic situations were not altogether new: the jibe that dollar princesses never know if men want them for themselves or for their gold might be thrown at the ‘merry widow’ herself.Footnote 20 Moreover, she, too, had status because of money and not aristocratic lineage. Even so, Fall’s operetta engages more directly with modernity than Die lustige Witwe by pitting the power of American capitalist enterprise against the declining economic fortunes of the landed gentry. The Dollar Princess records the emergence of a new era when financial capital conquers all, turning the landed aristocracy into what Antonio Gramsci called ‘pensioners of economic history’.Footnote 21 In Act 1, the following exchange takes place between the American, Conder, and his head groom, the former Earl of Quorn.

Quorn: I understand it amuses you to recruit your servants from the ranks of the British aristocracy.

Conder: That’s it. It amuses me, and I can afford it. Besides, I’m doing the Mother country a good turn by reducing the number of her unemployed.

The chorus in the opening scene of the London production recognizes the social change brought about by capitalist enterprise:

In the UK, the political tide was ebbing away from the aristocracy. In 1909, the year of the London premiere of The Dollar Princess, new land taxes were introduced by the Liberal government. Implementation was delayed until 1910 by the House of Lords, but that served only to pave the way to a reform of the Lords’ veto in the Parliamentary Act of 1911. The clash between businessmen and landed gentry was a social reality, but the operetta treads a fine line, neither celebrating nor bemoaning social change.

The expansion of the railroads in the later nineteenth century, and the electrification of factories in the early years of the twentieth, gave a huge boost to the American economy, enabling the USA to ride out the depression of 1893–97 and become more productive in manufacturing than the UK.Footnote 22 The Edwardian era was a time when ‘all-conquering “dollar princesses” married their way into a third of the titles represented in the House of Lords’.Footnote 23 An early precedent was Lord Randolph Churchill’s marriage in 1874 to Jennie Jerome, the daughter of a Wall Street financier (she was to be Winston Churchill’s mother). The operetta does not, however, reference the sneering that wealthy American women had to face from those who placed status and value on ‘breeding’ and the distant date in history that their family acquired the charismatic capital of an aristocratic title. Despite pride in heritage, noble families were now showing that, in certain circumstances, they were willing to come to an arrangement with the right kind of moneyed person.

Sometimes, stage glamour rather than wealth drew the attention of eligible male aristocrats. It is remarkable how many women, especially in the years 1906–13, abandoned theatrical careers to marry peers of the realm. The legal constraints of morganatic marriage, which prohibits the passage of a husband’s title to a commoner and disallows its descent to children born from that marriage, did not exist in the United Kingdom. Nevertheless, in going strongly against tradition, these marriages were symptomatic of modernity, even if defended frequently by the argument that they strengthened a weakened blood line. Among those who married into the aristocracy after performing on the West End stage were Connie Gilchrist (Countess of Orkney, 1892), Rosie Boote (Marchioness of Headfort, 1901), Silvia Storey (Countess Poulett, 1908), Eleanor Souray (Countess of Torrington, 1910), Zena Dare (Lady Esher, 1911), May Etheridge (Duchess of Leinster, 1913), Olive May (Lady Paget, 1913), Irene Richards (Marchioness of Queensberry, 1917), José Collins (Lady Innes, 1920), and Gertie Millar (Countess of Dudley, 1924).Footnote 24 The jaded story of the beautiful young woman that improves her social status by marrying someone with wealth and, preferably, aristocratic connections gained a new resonance with the number of female stage performers who found themselves in this position. Yet it worked against the interests of the New Woman, who was bent upon making her own distinctive mark on the world through intellect and ambition.

The Modern Woman and Issues of Gender

Department stores, restaurants, railway stations, and theatres were modern spaces that men and women could occupy without moral suspicion of their motives. Department stores strove to attract women and encourage frequent visits. Many middle-class women took trains into town for a shopping trip and a visit to a matinée performance at the theatre. Matinées had been introduced in the 1870s and proved popular with women. George Edwardes told a Parliamentary Select Committee in 1892 that ‘suburban ladies’ were his most important clientele.Footnote 25 Department stores and theatres had more in common than their urban proximity; they were, as Erika Rapport observes, ‘partners dedicated to igniting consumer appetites’.Footnote 26 The stage functioned like a shop window for costumes, furniture, and other desirable items.

The female glamour on display raises questions. To what extent can it be regarded as encouraging an erotic gaze and to what extent did it incite consumerist desire? Does operetta glamour address a feminine gaze as much as a masculine one? Rita Detmold’s column ‘Frocks and Frills’ in the Play Pictorial comments that A Waltz Dream ‘might easily be re-christened “The Ladies’ Dream,” for the gowns worn throughout this charming production are alone worthy of a visit to Daly’s’.Footnote 27 Other columns of this magazine readily assume that its women readers embrace the modern. Jennie Pickworth’s column ‘What-Not’, in 1927, contains advice on perfume, hair styles, and shampoo, and she asserts: ‘Modern woman has certainly become educated in the subtle niceties of scent.’Footnote 28 The ‘modern woman’, we are told, prefers floral fragrances to obtrusive exotic scents.

With regard to fashionable and personal items of dress, men are targeted less and less in Play Pictorial advertisements after 1910. In the Merry Widow issue of 1907, for example, Morris Angel & Son announce that they made the ‘Gentlemen’s costumes’ in the first and third act, and the makers of the Velvet Grip stocking supports advertise their ‘Boston Garters’ for men’s socks, whereas in December 1909 their advertisements target women consumers only.Footnote 29 In 1912, there is an advertisement for Southalls’ sanitary towels, which possess ‘health advantages that are a boon to womankind’, and will be sent post free under plain cover.Footnote 30 In the 1920s, there is another sign of progress, this time in the technology for managing and controlling hair, and there are many advertisements about ‘permanent wave’ products, and ‘bobbed’ and ‘shingled’ coiffures.

The labelling of young women as ‘girls’, which became frequent in the titles of musical comedies of the 1890s and in reference to the Gaiety Theatre’s women performers, has been described by Peter Bailey as a strategy to frame them as ‘naughty but nice’.Footnote 31 There was a new decorum in the presentation of women on stage, and the burlesque days of short skirts had largely disappeared by the 1890s. The Gaiety Girl was not prim or over-zealous in religion and politics, nor intellectually ambitious in the manner of the New Woman.Footnote 32 James Jupp, for many years the stage door-keeper at the Gaiety, sets out the qualities that were sought when young women were auditioned:

They are chosen not only on account of their figures, height, and beauty – necessary attributes, it is true – but chiefly on account of their drawing power. Brains are not asked for so long as the show girl knows how to wear the beautiful gowns provided for her; but the most important question is: how many stalls and boxes can she fill, with whom is she well acquainted? If she is a woman of great personal attraction and boasts a lover or two of the aristocracy, she is certain of a position. She is then the means of attracting to the theatre nightly thrice or four times her weekly salary.Footnote 33

Jupp is perfectly aware that some of those selected are highly intelligent women, but his point is that brains were not an essential requirement; what really counted was the woman’s ability to draw into the theatre those who purchased expensive seats.

The ‘merry widow’ is not a girl, even if played in London by the young Lily Elsie. She has a confidence and self-drive that is unusual among opera heroines, and must be categorically distinguished from the typically doomed characters discussed by Catherine Clément.Footnote 34 She was lowly born but became the wife of a wealthy banker after Danilo’s father forbade his son’s marriage to her. The novelty of her character was noted by theatre historian MacQueen-Pope: ‘Here was no ordinary heroine, shrinking in maidenly modesty before the man she loved; here was a rich woman of the world, coming face to face with a man whom she considered had slighted her.’Footnote 35 Alice, the ‘dollar princess’ is a similar force to be reckoned with, and, as a ‘self-made Mädel’, knows about the world of business. The American ‘duchess’ in Kálmán’s Die Herzogin von Chicago is also headstrong. Her money comes from the profits of her father’s sausage factory (no doubt intended as satire of American mass production). In this operetta, the impecunious Prince of Sylvaria finds himself in a similar position to Alice’s lover Freddy: both of those wealthy women see them as commodities to be purchased.

Many operettas stage a form of duel between the sexes. It was not uncommon for the woman to have a more dominant role in the drama than the man. The modern woman in operetta differed from what Frey describes as ‘the legendary pig-tailed, sweet and innocent Viennese girl’.Footnote 36 Ironically, the latter returned when Viennese operetta had passed its heyday in London, in Novello’s The Dancing Years. The modern young woman rode a bike, played tennis, and rebelled against ‘wasp waists’ and tight corsets. Evelyn Laye, as Alice in the revival of The Dollar Princess at Daly’s, was featured in a publicity photograph holding a tennis racket.Footnote 37

Fall’s operetta Jung-England (libretto by Rudolf Bernauer and Ernst Welisch), first performed in Berlin in 1914, focuses on the British ‘Votes for Women’ campaign, but the outbreak of war later that year meant it had no chance of being seen in London. A suffragette rally had taken place in Hyde Park in 1908, and women soon resorted to direct action. Much attention was given to the death of Emily Davison, who ran onto the racetrack at the Epsom Derby in 1913 and died after falling between the hooves of the King’s horse. These events stimulated wider interest, and, in this operetta, a police chief has a daughter who sympathizes with the suffragettes and warns them about his plans. This being an operetta, the suffragette leader settles down as a contented wife before the final curtain falls. At the time of its premiere, the only European countries to have granted full voting rights to women were Finland (1906) and Norway (1913). Austria and Germany granted these rights in 1918, and that same year the UK allowed women to vote who were over 30 and met certain property requirements (equal voting rights with men had to wait until 1928). Women’s suffrage campaigns were becoming more radical in the USA from 1906 on, with the efforts of Harriet Stanton Blatch and Emma Smith DeVoe. Gradually, voting rights were won in more and more States, but violent incidents were also occurring, such as the attack on a suffrage parade in New York in 1913 that left hundreds of women injured. In 1920, universal suffrage was endorsed in the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution.

Suffragettes feature elsewhere in operetta: The Girl on the Film (1913) begins with a scene involving a women’s rights agitator, although she turns out to be acting a role. The Girl in the Taxi (1914) has a duet in which a couple claim, with considerable irony, that their marriage is perfect – the man remarking that his wife is not a suffragette. Department stores usually had restaurants in which women felt comfortable ordering a table and, when it became known that Gordon Selfridge sympathized with the suffragette cause, the store he founded in 1909 on Oxford Street became a favourite meeting place. A Selfridge executive, Percy Nash, wrote a play, The Suffrage Girl, which was performed by the store’s employees at the Court Theatre in 1911.Footnote 38

Another issue for women was equal opportunities and fair treatment in the workplace. During the war, women took on a lot of what had formerly been men’s work; yet, in 1921, they constituted the same 29 per cent of the workforce as before the war.Footnote 39 A young working-class woman in a Belgian glass factory is the leading character of Lehár’s Eva (1911). Belgium did have a large glass factory, Val-St-Lambert, located in Liège, which traded internationally in everything from car headlamps to vases. The factory in Eva is in Brussels, which may have been a strategic decision, given the political dimension of this operetta. Eva was seen by many in Vienna as fuel for the cause of social democracy, and the press seized the opportunity to label it as such. Wilhelm Karczag, the Intendant of the Theatre an der Wien in 1911, felt compelled to reject publicly the claims made ‘over and over again’ that it was socialist propaganda, asking irritably, ‘because workers revolt, is that Socialism?’Footnote 40 He preferred to interpret the men’s action in protecting Eva from her sexually predatory employer as chivalry rather than socialism. Ideas of social change were very much in the air after the death of the right-wing mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger in 1910, and helped to prepare the ground for the dominance of the Social Democrats during 1918–34, when the city became known as Rotes Wien (Red Vienna). Willner and Bodanzky manage to be politically evasive in their libretto, because the leader of the workers’ revolt is in love with Eva. Without that compromise – and its implication that Eros was as much a stimulus to action as socialism – it might have seemed too rebellious. Another toning-down feature is found in its reference to fairy tale, and Eva’s Cinderella-like aspirations.

Socialism was a fiery topic at this time in the UK, and that may explain why Eva did not receive a production in the West End (it did so on Broadway). Trade Unionism had strengthened after the London dock strikes and the Liverpool general transport strike of 1911, and there was a succession of labour disputes the following year. In Act 1 of the West End production of The Cinema Star in 1914, the cooks have gone on strike at the Ritzroy Hotel, London, where the housemaids and waiters have been on strike previously. It soon transpires that the telephone operators and taxi men are on strike, too.

The ‘factory girl’ was not completely new as a stage heroine. Paul Rubens’s musical comedy The Sunshine Girl (1912) had a plot revolving around Delia Dale who works in a soap factory inherited by a man who has fallen in love with her. It was clearly meant to call up associations with the Lever Brothers’ soap factory and their ‘Sunlight’ cleaning agent, but it was primarily a comedy of mistaken identity and lacks the political edge of Eva. Other urban working women appear in The Blue House, produced at the London Hippodrome in 1912. It was Kálmán’s setting of an English libretto by Austen Hurgon. Regrettably, the score has been lost, but the short operetta was set in a launderette. Publicity described its women workers as ‘40 examples of female loveliness’, which suggests that this was not, perhaps, a gritty social drama.Footnote 41

A new professional class of women also finds a place in operetta: the achievements of modern women are celebrated in a quintet in The Lilac Domino (1914) titled ‘Ladies’ Day’ (with lyrics by Robert B. Smith):

Next, we hear of ‘lady teachers’, lecturers, aeronauts and ‘girl chauffeurs’, and, later, lawyers, poets, barbers, and doctors. Women musicians are not mentioned, but there was a ten-strong ‘Ladies’ Orchestra’ on stage in the Hicks’s Theatre production of A Waltz Dream in 1908. The principal character in Gilbert’s Moderne Eva (1911), given on Broadway in 1915 as A Modern Eve, is a woman doctor, and her mother is a lawyer. In Abraham’s Roxy und ihr Wunderteam (Budapest, 1936; Vienna, 1937) the heroine is an English woman who becomes the coach of the Hungarian national football team. Given growing political tension in Europe, this operetta arrived too late to be considered for a Broadway or West End production.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the power structures controlling theatrical production were largely in the hands of men.Footnote 42 However, a number of women were involved in the writing of operetta. Rida Johnson Young, the librettist of Herbert’s Naughty Marietta, was responsible for Her Soldier Boy, the Broadway version of Kálmán’s Gold gab ich für Eisen, in 1916. She worked with Romberg on Maytime the following year and made the tactful decision to shift the action of its German source Wie einst im Mai to New York (the USA having now become embroiled in the war). Dorothy Donnelly collaborated with Romberg, too, writing the book and lyrics for Blossom Time (1921), the Broadway version of Das Dreimäderlhaus.Footnote 43 Fanny Todd Mitchell took charge of Emil Berté’s Musik im Mai in 1929, and, in the same year, reworked Die Fledermaus as A Wonderful Night for production by the Shuberts at the Majestic. Other women involved with German operetta for Broadway were: Catherine Cushing (Kálmán’s Sári 1914), Anne Caldwell (Winterberg’s The Lady in Red, 1919), Marie Armstrong Hecht and Gertrude Purcell (Kollo’s Three Little Girls, 1930), and Clare Kummer (Heuberger’s The Opera Ball, 1912, and Straus’s Three Waltzes, 1937). In London, Mrs Caley Robinson (Winifred Lucy Dalley) worked with Adrian Ross on the West End version of Lincke’s Castles in the Air in 1911. Findon informs us that Gladys Unger, an American who lived in England from the 1890s to the 1920s, translated Victor Jacobi’s The Marriage Market from the original Hungarian libretto by Max Brody and Ferenc Martos.Footnote 44 The English lyrics were written by Arthur Anderson and Adrian Ross, so must have been based on the German version by E. Motz & Eugen Spero.

In the fictional world of Paul Abraham’s Ball im Savoy, the jazz composer Daisy Darlington enters and sings her latest dance hit ‘Kanguruh’ (Kangaroo), composed under her pseudonym José Pasadoble. The song claims that the fox trot has been passé for a long time, nobody knows if people dance the rumba, and you don’t see the tango much anymore. The new, fashionable dance in Europe in the Kangaroo. Paris is bewitched by it, and London is crazy for it; soon, Berlin will be delighted with it. In reality, very few women were involved in the theatre as composers. Elsa Maxwell was responsible for an interpolated number ‘A Tango Dream’ for Eysler’s The Girl Who Didn’t (1913), which was a hit for American singer Grace La Rue, who appeared in the West End production. Ivy St Helier was a composer, lyricist, and actor, and responsible for interpolated numbers in Stolz’s The Blue Train (1927). Kay Swift was the first woman to compose a successful Broadway musical, Fine and Dandy (1930), to a book by Donald Ogden Stewart and lyrics by Paul James. Her music was orchestrated by Hans Spialek.

Tobias Becker remarks on how often a woman occupied the central role in an operetta and how common it was for a woman to feature in its title, but he points out that, rather than depict the emancipated and political ‘new woman’, operetta preferred self-confident but ultimately harmless young women who did not threaten traditional social order.Footnote 45 There are, however, plenty of exceptions. Self-assured women who threaten social order include Hanna/Sonia (Die lustige Witwe), Olga (Die Dollarprinzessin), Gonda (Die geschiedene Frau), Jeanne (Madame Pompadour), Anna Elisa (Paganini), Amy (Lady Hamilton), Manon (Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will!), Daisy (Ball im Savoy), and Marie Jeanne (Die Dubarry). Heike Quissek, in her study of German operetta librettos, describes Amy Hamilton as having an unusual degree of ‘impertinence bordering on self-assurance’.Footnote 46 Many of these women are confident in their sexuality. Of the London production of Straus’s Cleopatra, Findon remarks:

It was a somewhat daring experiment to make ‘Cleopatra’ the heroine of a musical play. … The authors in the present instance, however, deal lightly with the lady whose charm and infinite variety made her the beauty-witch of her generation, and the type for succeeding ages of erotic womanhood.Footnote 47

Evelyn Laye, who took the role of Cleopatra, had previously played Madame Pompadour, to whom, a critic commented, Laye brought charm as well as naughtiness.Footnote 48 Manon Cavallini, in Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will!, asks defiantly why a women should not have a relationship. The operetta includes in its cast ‘former partners or friends from whom she is partly separated’. The very title of the operetta seems to fly in the face of Freud’s famous question ‘was will das Weib?’Footnote 49 Here is a woman who knows what she wants. Operetta, observes Marion Linhardt, placed women on stage in two differing ways: she is either in a group that functions in a non-individualistic and mechanistic manner, or, she is the ‘extraordinary’ woman (played by the diva), whose characteristics are moodiness, eccentricity, obstinacy, self-confidence, and seductiveness.Footnote 50 Such is often the case, but those qualities apply only selectively to the characters mentioned in this paragraph.

Modernity and Sexuality

In the UK, concerns about morality became more relaxed in the early twentieth century than the 1890s. In 1892, the Lord Chamberlain had refused a licence for Oscar Wilde’s French play Salomé, and Aubrey Beardsley’s erotic illustrations that accompanied the English translation of the play in 1894 were considered an affront to bourgeois respectability. In 1908, none of that prevented the first prize at a Fancy Dress Carnival held at the Crystal Palace, Sydenham, being awarded to theatrical costumier Mary Fisher dressed as SaloméFootnote 51 or, in 1910, the performance of Richard Strauss’s opera Salome, based on Wilde’s play, at Covent Garden. The phrase ‘dance of the seven veils’ had been invented by Wilde for Salome’s dance, and, in the early 1900s, it became associated with pseudo-Oriental striptease shows.

The more open attitude to sexuality, that is a feature of modernism, is found in Die geschiedene Frau (1908), the operetta Fall composed immediately after Die Dollarprinzessin to a libretto by Victor Léon. It was based on Sardou’s play Divorçons!, which was popular in continental Europe. In Austria, at the time of the production of this operetta, civil marriages did not exist and divorce was difficult. Rumours, however, had circulated about a divorce that had taken place within Viennese high society.Footnote 52 Ironically, a little over five years after this operetta’s premiere, Leo Fall’s wife Bertha filed for divorce.

The first scene is set in the divorce court of the Palace of Justice, Amsterdam. The defendant, Karel, alleges he was trying to assist Gonda van der Loo, while travelling on the Nice express: ‘She had omitted to book a sleeping compartment’ and was ‘in great distress’. He shared his lunchbox with her in a compartment reserved for himself, and it included – to the consternation of those in court – a bottle of Cliquot champagne. There was nothing else to drink. Finding a dirty collar on the seat, he complained to an attendant about the untidiness of the compartment. The attendant became angry and departed slamming the door, causing the lock to break and leaving them trapped inside. The attendant is called to give evidence and is asked if he works for the Trans-European Sleeping Car Company. In the German version, he is an unemployed academic, but in the West End version he is a socialist, who assures the court that the word ‘work’ has been ‘expunged from the vocabulary of the Labour Party of which I am a prominent member’. The Labour Party had been formed in 1900 but had adopted this name only four years before the West End production of 1910, and its political agenda was becoming a target for satire. The attendant claims he gently closed the door after Karel had been rude to him, but later found the door locked and could hear a woman laughing. The plot is resolved when it turns out that there was a third person in the sleeping car, who, having failed to purchase a ticket, had hidden under the seat all night. He had previously taken off his collar, and this was the dirty collar Karel found.

Superficially, then, all appears to be light-hearted innocence and unrelated to modern notions of sexual audaciousness. Bernard Grun writes that the first act is filled with an amusing trial scene ‘à la Gilbert und Sullivan’.Footnote 53 Indeed, the difficulties are all resolved by the judge, as in Trial by Jury, although, in this case, the judge pairs off with a woman accused of improper behaviour. An ‘innocent’ reading, however, faces complications from the fact that, in the German version, Gonda is the editor of the journal Freie Liebe (Free Love). She makes clear her views on this subject, claiming that love does not need, and usually does not long survive, the shackles of marriage: ‘frei sei Weib und frei sei Mann, Liebe sei nicht Pflicht!’ (‘let women be free and men be free, love shouldn’t be a duty!’) Those sentiments accorded with the views of the Verband Fortschrittlicher Frauenvereine (League of Progressive Women’s Associations), who were active in Germany from 1891 to 1919, and called for a boycott of marriage and for the enjoyment of sexuality. The league was founded by Lily Braun and Minna Cauer, and had among its aims the unionization of prostitution, the teaching of contraceptive methods, abortion rights, and the abolition of laws prohibiting same-sex relationships. In 1895 and 1897, Berlin school teacher Emma Trosse published pamphlets on homosexuality and free love.Footnote 54 Advancing these thoughts could attract penalties: Adelheid Popp, editor of the Arbeiterinnen-Zeitung, was prosecuted in Austria in 1895 for publishing a free love article that was deemed to degrade marriage.Footnote 55 Nevertheless, the debate continued after the war. Hugo Bettauer, in his article ‘Die erotische Revolution’ (1924), states that men created the ‘fundamental principle, that the erotic belongs to marriage’, and argues that ‘the man has access to free love through secret means whereas for the woman there is only subjection’.Footnote 56 Such ideas were also promulgated in the UK and USA. Victoria Woodhull, leader of the American suffrage movement, defended free love in a speech in Steinway Hall, New York, in 1871.Footnote 57 In the UK, Edward Carpenter, one of the founders of the Fellowship of the New Life in 1883 and of the Fabian Society the following year, was a champion of sexual freedom and what would now be called gay rights.

The West End version ignores completely Gonda’s first verse in the Act 2 duet ‘Gonda liebe, kleine, Gonda’, in which she declares that she is unconcerned about fidelity and the rights of wives. She claims that marriage is demanded only because of conventional ideas of social duty and good reputation.

After the first performance in Berlin at the Theater des Westens, 6 Sep. 1910, the Berliner Zeitung commented that Die geschiedene Frau had all the necessary ingredients for a modern operetta.Footnote 58 Nevertheless, as mentioned in Chapter 2, it was found necessary to tone down this operetta in both its West End and Broadway versions as The Girl in the Train (1910), although the unconventional Gonda replaced the wife as the title character.

Sexuality was being explored more broadly and openly in the early twentieth century. The visual arts spring first to mind. One of the themes of ‘The Women of Klimt, Schiele and Kokoschka’, an exhibition held at the Belvedere, Vienna, in 2015 was an exploration of gender politics in Vienna at the beginning of the twentieth century, ‘when both women and men’s sexuality were undergoing a revolution’.Footnote 59 There was cross-dressing from female to male in Filmzauber and from male to female in Die Rose von Stambul. There was also erotic dressing in the Viennese version of Die Dollarprinzessin: Olga’s arrival with her women Cossacks was striking because of her costume, which, she admits knowingly, is so close and tight that it ‘gets many guessing’.Footnote 60 This entrance scene was omitted in the London and New York versions.

Sigmund Freud published three essays on sexual theory, Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie, in 1905.Footnote 61 The following year, Austrian author Robert Musil offered a study of transgressive sexuality in his novel Die Verwirrungen des Zöglings Törless. Sexuality was also a topic in the air in the UK, where, Mica Niva informs us, ‘Free love and the idea of sexual pleasure as an entitlement for women as well as men were gradually put on the agenda, albeit in mainly urban Bohemian and intellectual circles’.Footnote 62 Telling questions are posed in operetta songs: for example, ‘Was hat eine Frau von der treue?’ (‘What does a woman gain from fidelity?’) from Ball im Savoy and ‘Warum soll eine Frau kein Verhältnis haben’ (‘Why shouldn’t a woman have a relationship?’) from Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will! The question of an age of consent is raised in Friederike, in the title character’s poignant song, ‘Warum hast Du mich Wach geküsst?’ (‘Why did you kiss me awake?’). Friederike asserts, ‘Ich war kein Weib, ich war ein Kind’ (‘I wasn’t a woman, I was a child’). Her love involved more than kissing, as the line ‘Mit jeder Faser war ich Dein’ (‘With every fibre I was yours’) makes plain.

When the focus shifts to queering the production and consumption of operetta, much light is shed by the arguments compiled and edited by Kevin Clarke in Glitter and Be Gay (2007).Footnote 63 It requires little effort to queer certain operatic characters, such as Fränze, who passes incognito as a drummer boy in Filmzauber, the Zarewitsch in Lehár’s operetta of that name, Schubert (Das Dreimäderlhaus), and Josepha Vogelhuber (Im weißen Rössl). Camp representation was part of operetta from its early days, but is perhaps most associated with the productions of Erik Charell. Charell had been far from discreet about his sexuality in the 1920s, when he found a gay partner in African-American Louis Douglas, a star of La Revue nègre (Hopkins). Regarding the various male groups in Charell’s production of Im weißen Rössl, Clarke writes that no gay cliché was left out, although it could all be viewed ‘innocently’ as local colour.Footnote 64 Charell was also aware of the erotic spectacle of his boys in lederhosen and girls in short dirndls. Today, it is possible to regain a sense of how camp functioned in the silver age of operetta by watching certain operetta films of the period. The consciously ‘tacked on’ operetta finale to Die Drei von der Tankstelle (1930) with its high-kicking chorus line is a good place to begin.

Modern ‘Enlightenment’ and Spectacle

New York began to move from gas to electric street lighting in the 1880s, and, by 1895, electric signs were common. Electric lighting had become familiar in theatres in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Hollingshead had been the first to use electric lights in a London theatre (the Gaiety, 1878) using the Lontin light.Footnote 65 At the turn of the twentieth century, New York had more electric illumination than either London or Berlin. Broadway was already known as the ‘Great White Way’ in the 1890s, mainly because of its electric advertising.Footnote 66 Charles Dillingham introduced the first electrically illuminated advertising sign on Broadway the season before the Merry Widow premiere.Footnote 67 Striking modern poster design was developing, too: a widely used poster for The Chocolate Soldier showed Captain Massakoff’s finger pointing directly at the viewer, and carried the accusation: ‘You haven’t seen the Chocolate Soldier yet!’ It was a forerunner of Alfred Leete’s famous Kitchener recruitment poster for the First World War.

New York was even better served by electric trams in the early 1900s than Berlin, which possessed the best tram network in Europe. New York’s first underground line opened in 1904, three years before The Merry Widow.Footnote 68 The world’s first underground railway line (the Metropolitan) opened in London in 1863 and had 40 million passenger journeys a year by the 1870s.Footnote 69 With increased transport available, the urban consumer’s attitude to country life and its villages changed. If a city dweller moves to the country, he or she soon desires city features (reliable telecommunications, street lighting, and roads free of mud). The countryside that lacks these attributes is consumed as scenery – a green field, a tranquil lake, a misty mountain – or as rural heritage (a national park). Onstage, such scenery became spectacle enhanced by modern technology.

Revolving stages were speeding up scene changes. A complicated revolving stage mechanism had been installed at the Coliseum in 1904 and was used to great effect in the production of White Horse Inn.

It is much more than merely a ‘mammoth’ show. It is like nothing that has yet been presented. It surrounds and wraps one up in jollity, colour, and music, attacking from both sides as well as in front. The three revolving stages bring the scenes on and off with a rhythm that is an inspiration in itself.Footnote 70

The revolving stage was especially effective for showing the trip round the lake.

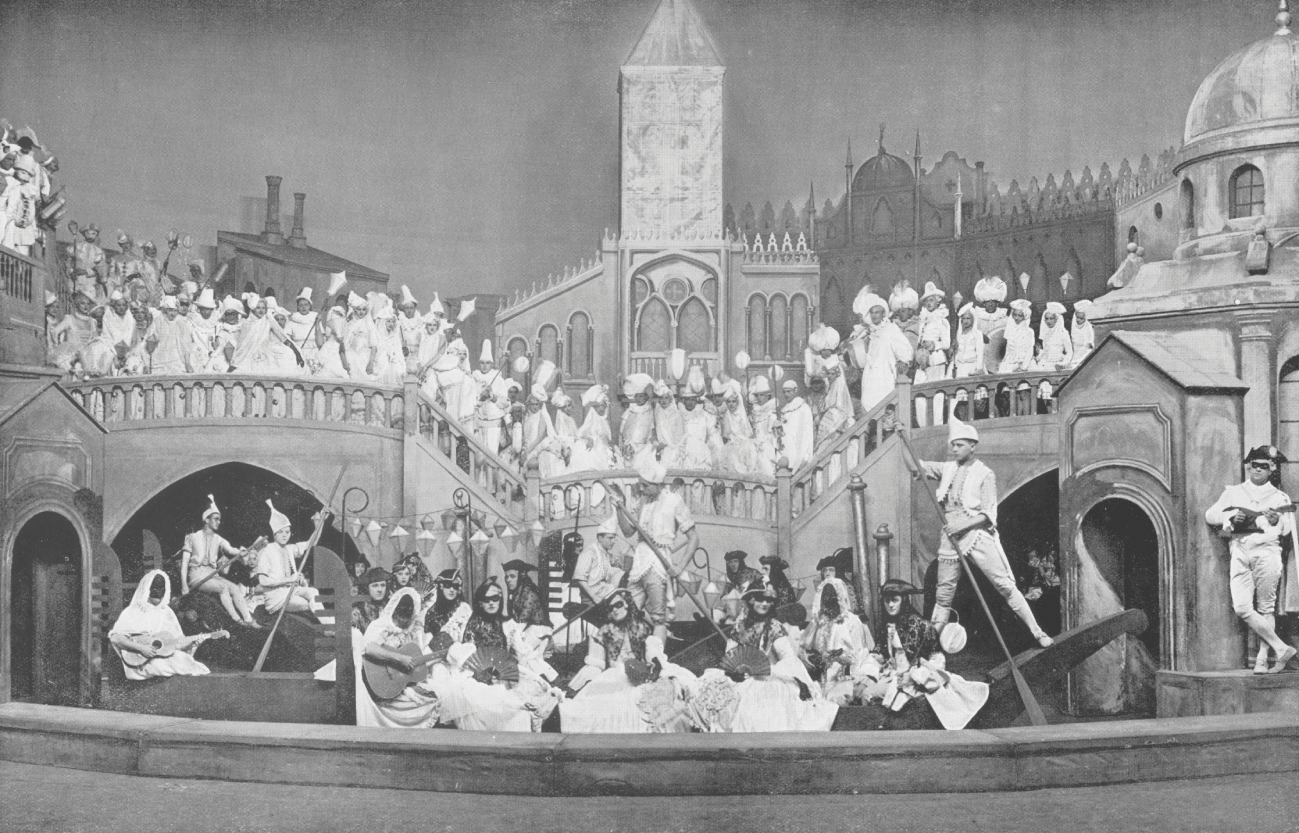

Stoll re-engaged Charell for the next Coliseum production, Casanova, which was proclaimed ‘the ultimate limit in stage spectacle’.Footnote 71 The revolving stage was in action again, enabling ‘scenes of loveliness’ to succeed one another in ‘marvellous sequence’.Footnote 72 After ‘an extraordinary pageant of scenery’, the performance culminated in a revolving panorama of the carnival in Venice, ‘with hundreds of gaily clad revelers, gondolas, canals and palazzos paying tribute to the producer’s genius’Footnote 73 (Figure 7.1). Not everyone was bowled over by it all: Charles Morgan, reporting from London for the New York Times, complained that it created ‘an impression of unselective excess’.Footnote 74

Figure 7.1 Venetian Scene in Casanova (Coliseum, 1932). The Play Pictorial, vol. 61, no. 364 (Dec. 1932), 20.

Technological developments in stage lighting also played an important role, making possible realistic effects of thunder, lightning, and rain. The Morning Post praised the cyclorama (the background scenery) of the Coliseum production of White Horse Inn in April 1931.

[T]here is the ‘cyclorama’ of the Alps standing out just as if they were real, with a quite marvelous moment of storm; a lake with a steamer from which the Emperor arrives; mountain-top scenes with goats and comic cows and reveling yodelers, and above all, an inexhaustible wealth of design, richness, and variety in Ernst Stein’s costumes.Footnote 75

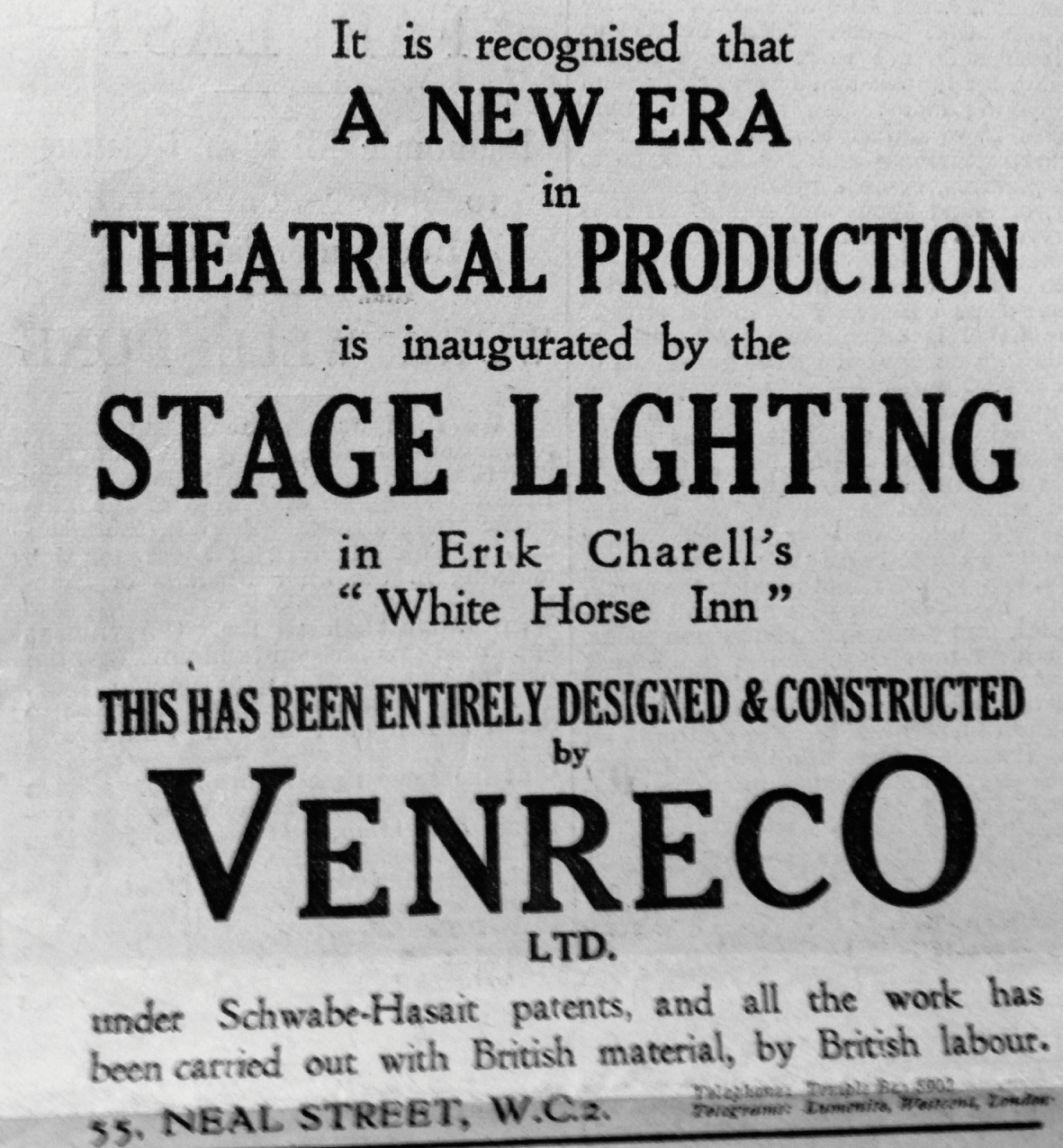

Lehár expressed surprise at the stage lighting employed at Daly’s and the costs it must entail,Footnote 76 but great strides were being made in stage lighting in Germany in the 1920s, and they soon crossed the English Channel. The London firm Ventreco claimed that a new era had begun with the lighting of White Horse Inn, and although they admit to having achieved it under Schwabe-Hasait patents, they stress that it was with the employment of British material and labour (Figure 7.2).Footnote 77

Figure 7.2 Advertisement in the Sunday Referee, 5 Apr. 1931.

Hans Schwabe had been active in Berlin before the First World War. He had developed a battery of 1000-watt lanterns that replaced the large central lanterns at the Deutches Theater and gave an even spread of light. Schwabe’s assistant Reiche developed a machine that projected clouds onto the cyclorama (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Reiche’s 3000-watt cloud machine, containing two tiers of lenses and mirrors.

Max Hasait was stage manager of the Residenz Theater, Munich, and developed a cyclorama that could be set very quickly from either side of the stage, allowing realistic effects of storm, lighting and rain. The Schwabe-Hasait system had already been tried out in St Martin’s Theatre and Drury Lane in the mid-1920s.Footnote 78

It took several years for White Horse Inn to reach New York, but on 1 October 1936 it opened at the Center Theatre, where ‘the genii of American spectacle making [had] done one of their handsomest jobs on this international holiday to music’.Footnote 79 It involved:

mountain scenery and hotel architecture, costumes beautiful and varied enough to bankrupt a designer’s imagination, choruses that can do anything from the hornpipe to a resounding slapdance, grand processionals with royalty loitering before the commoners, a steamboat, a yacht, a char-à-banc, four real cows and a great deal more of the same.Footnote 80

The cows had been distinctly and purposefully unreal in the London production. The songs, by Benatzky and others were characterized without condescension as, ‘for the most part, simple things which are well-bred and daintily imposing’. The director Erik Charell, who was also partly responsible for the libretto, was praised for ‘the general spirit of good humor that keeps “White Horse Inn” a congenial tavern’.Footnote 81 A report three days later claimed that the second night’s gross taking at the Center Theatre was $7,240, ‘a sum which smacks of success’.Footnote 82

Spectacle was a way of engaging with modernity, with the new means of representation that technology made possible. Even operettas that were set in Ruritanian principalities related to modernism: first, because they offered spectacle, but also because they depicted a type of social formation that was failing in the modern age. Not every theatre critic was bowled over by spectacle. After describing the London production of Abraham’s Ball at the Savoy as ‘a spectacle’, the reviewer elucidates as follows: ‘Bits of the stage and bits of the chorus keep on going up and down.’ The costumes are treated to equally sardonic comment: ‘its dresses are, not beautiful, but an entertainment in themselves’.Footnote 83

Stoll brought spectacle to another of his theatres, the Alhambra. After having this theatre reconstructed, he invited Hassard Short to produce Waltzes from Vienna there in 1931. Findon writes of a ‘slight plot which bears so valiantly the mighty framework of scenic design and elaborate stagecraft’, but extols the production for having ‘amazed the world of amusement seekers’.Footnote 84 Besides the beautiful costumes and scenery, there were the modern stage lighting effects of the Strand Electrical Company. Hassard Short was English, but ‘discovered’ in America. He was a lighting expert, and one of his innovations at the Alhambra was to move the footlights to the dress circle, from where they threw a stream of light onto the stage.Footnote 85 He illuminated the stage further by using the latest lighting towers and a granulated reflector with a 1000-watt lamp that diffused and amplified the light at the same time.Footnote 86

The Strand Electric Company was again manufacturing and installing special lighting for Hassard Short’s production of Wild Violets (1933), this time at Drury Lane rather than the Alhambra. There was a cast of over 160 actors and 120 stage hands, and the production involved 16 scene changes and 260 costumes. The revolving stage allowed scenes to be built up invisibly, behind the scene the audience was currently viewing. The lighting system included a new bridge on the stage side of the proscenium arch employing 120 spotlights, many with telescopic lenses of three or four colours. There were 900 small electric lamps used to create a star-spangled background in the elopement scene, and 500 of them were used for the skating scene.Footnote 87 Findon remarks that the revolving stage and Short’s ‘bewildering, lighting effects’ made the strongest impressions – in spite of the ‘many tuneful melodies’. The scene of the ice-skating rink (with real ice) in the snowy Swiss Alps was ‘a joy to the eye’.Footnote 88 Another scene had the chorus on bicycles, but the precariousness of modern mobilities was also on display when a car was shown failing to climb a steep hill. In a comment that underlines some of the observations on intermediality presented in Chapter 6, the News Chronicle remarked that the revolving stage took the audience from scene to scene ‘with almost the rapidity of a film’.Footnote 89

Modernity and Mobility

Act 3 of the German-language version of Die Dollarprinzessin opened with an ‘Automobil-Terzett’ in praise of the motor car (omitted in the Broadway and West End versions).

Ja das Auto ihr Leute bewundert’s, ist die Krone des Jahrhunderts, ein Geschenk, das vom Himmel gesendet auf die Erd’, wenn man vorsichtig fährt! All Heil! All Heil!

Yes, the car you people admire is the crown of the century, a gift sent from heaven to earth, if you drive carefully! All hail! All hail!

Shortly after the Vienna premiere of Die Dollarprinzessin in November 1907, the American economy was further boosted by car manufacturing using ‘mass production’ techniques. The Ford Model T motor car was first produced in 1908, the year before Broadway premiere of The Chocolate Soldier. The fact that The Chocolate Soldier is set in Bulgaria during 1885–86 does not prevent Bumerli informing Colonel Popoff towards the end of Act 3 that he can supply ‘every make and style of motor car’.Footnote 90 One of Jean Gilbert’s operettas, Das Autoliebchen (1912), takes the love of cars as its theme – it was produced in the West End as The Joy-Ride Lady (1914).

Mimi Sheller and John Urry complain that early sociologists of urban life ‘failed to consider the overwhelming impact of the automobile in transforming the time–space “scapes” of the modern urban/suburban dweller’.Footnote 91 It might be added that the train had already had a similar effect. Transport was a subject taken up by scholars developing the ‘mobilities paradigm’ of early twenty-first-century sociology, which emphasizes that ‘all places are tied into at least thin networks of connections that stretch beyond each such place’.Footnote 92 Much of the focus of mobilities research is on later developments (for instance, airports and mobile technologies, and the distinction between mobility and migration), but in the first decade of the twentieth century, cars, motorbikes, trains, ocean liners, and airships were transforming connections between people and cultures. In the second decade, horses were disappearing from the roads to be replaced by cars and motor buses. In the mid-1920s, regular articles appeared in the Play Pictorial under the title ‘Players, Playgoers and the Car’. An advertisement in a 1924 issue gives the price of a basic Morris four-seater as £225.Footnote 93 In 2017, the relative cost would have been around £12,200 or $15,600; so this mode of transport was within the reach of some middle-class theatre goers.Footnote 94 Furthermore, second-hand models were appearing on the market.Footnote 95

The growth of tram networks and the asphalting of roads and streets enhanced mobility in cities. For travel further afield, transport by steamship and rail was improving. The synchronizing of clocks throughout a country was a consequence of the latter. The travel bureau was part of modernity: Lehár’s Der Mann mit den drei Frauen of 1908 (given on Broadway as The Man with Three Wives, 1913) features a travel guide as the leading male character, and the desire for tourism adds appeal to Benatzky’s Im weißen Rössl (1930) and Künneke’s Glückliche Reise (Bon Voyage) of 1932. Stolz’s Mädi (1923) concerns the Calais-Mediterranée Express, which ran between Calais and the French Riviera. The tile of the West End version was The Blue Train, a reference to the train’s alternative name, which it owed to the colour of its sleeping cars.

Dennis Kennedy remarks on the commonalities between tourists and theatre spectators:

As travelers approach a touristic site, so spectators encounter a performance through the gaze, which implies a distance of subject to object. Both spectators and tourists are temporary visitors to another realm who expect to return to the quotidian.Footnote 96

He adds: ‘Modernity and tourism are intertwined: as the technology of travel increased so more and more of the world became objectified as sights to wonder over or visit for private refreshment.’Footnote 97

The appeal of the Austrian alps as a tourist destination offers an explanation for the appeal of White Horse Inn, as it was to do later in the case of The Sound of Music. The Observer referred to White Horse Inn at the Coliseum as ‘Baedecker gone mad’.Footnote 98 Indeed, an updated edition of Baedecker drew on the operetta in describing the actual Weißes Rössl hotel in St Wolfgang, its lakeside setting and the availability of steamboat trips on the Wolfgangsee, before awarding it a Baedecker star.Footnote 99 Charell had envisaged a revue operetta that would appeal to ‘summer-resort addicted Berlin’.Footnote 100 Economic depression in Germany meant that a lakeside holiday was out of the question for many people. However, the idea of a visit to the real White Horse Inn was an attractive proposition for London’s more affluent theatre-goers. The programme for the Coliseum production carried an advertisement recommending this establishment to ‘discriminating people’ (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4 Advertisement from the Coliseum White Horse Inn programme (1931).

Staging the Modern World

The period 1880–1900 witnessed the growth of theatre quarters in Berlin, London, and New York. Len Platt argues that one of the most important struggles among competing theatrical centres was over the concept of modernity: ‘This was the real domain that musical theatres fought over, because, even in the sphere of light entertainment – then as now – whoever authorised the modern authorized the world.’Footnote 101 Kerston Lange offers the comment: ‘Musical theatre was where “the world” in the city was staged.’Footnote 102

The twentieth century witnessed changes in the representation of other cultures. Fall’s Die Rose von Stambul of 1916 (given on Broadway as The Rose of Stamboul, 1922) is full of historical references, but makes constant reference to westernizing reforms.Footnote 103 Its topicality and connection to events in Turkey at the time of its 1916 premiere in Vienna were evident when Hubert Marischka, playing the lead role Achmed Bey,Footnote 104 wanted his costume to be a khaki uniform with black fur hat and high black boots. This outfit was familiar from images of the Turkish general Mustafa Kemal, who had driven the British from the Dardanelles in the previous year.Footnote 105 Kemal had been born in what is today the Greek city of Thessaloniki, which, in Ottoman days, was known as Selanik. Although he had many years of active service in the Ottoman Army, he regarded his struggle for an independent Turkey during 1919–22 as a fight against Ottoman oppression.

The operetta is set in the early twentieth century, when the Ottoman Empire had declined and its receptiveness to western European influence had increased. In 1908, ideas of liberal reform and democracy were very much in the air, and the Young Turk Revolution began. Reform is an important issue in Die Rose von Stambul. Kondja Güll, the daughter of Kemal Pasha, rebels against her father’s plans for her marriage because she is corresponding with the poet André Lery, who believes in fighting for the emancipation of women. She has read his novels, but they have never actually met. With typical operetta felicity, he turns out to be Achmed Bey, the very man her father wishes her to marry, who writes under a pen name. Kondja’s girlfriend is named Midilli, the Turkish name for Mytilini, the capital of Lesbos. Both Thessaloniki and Mytilini were taken by Greek forces in the First Balkan War, which ended three years before Die Rose von Stambul was premiered. The women in the operetta look forward with eager anticipation to ‘reforms on the Bosphorus’ and the abolition of the veil.

The idea that there was an appetite for westernizing reform in Turkey received a jolt after the horrific destruction of the cosmopolitan city of Smyrna in 1922, but Mustafa Kemal began driving reforms through once he became the first president of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. In 1925, his wife witnessed a performance of Friml’s Rose-Marie at Drury Lane, and believed she had found a useful aid to her campaign to persuade Muslim women to drop the old policy of seclusion and advance ‘their education in the lighter phases of life’; and so she made arrangements for it to be presented as soon as possible in the new Republic of Turkey.Footnote 106 The issue of Turkish reform proved topical again, when the Die Rose von Stambul was performed at the Lehár Festival, Bad Ischl, in 2016, a hundred years after its premiere. The critic of the Salzburger Nachrichten found it ironic how times had changed, that the current Turkish leader wanted to ‘turn back history’, and that Istanbul had acquired notoriety as the scene of terrorist atrocities.Footnote 107

Orientalist devices in this operetta are infrequent, and often serve merely to frame a scene (as in the opening and close of the operetta). Elsewhere, they are applied unevenly (see Chapter 1). When the subject turns to fashionable pleasure (‘das Glück nach der Mode’), a waltz rhythm is heard. It is also significant that Achmed Bey tries to seduce Kondja with the song ‘Ein Walzer muß es sein’. That not as fanciful as it may seem; the Ottoman interest in the waltz was longstanding, and the nineteenth-century sultans Abdülaziz and Murad V both composed waltzes.

Modernity was no longer so exciting or chic after the outbreak of the First World War. It could feel threatening, and revues sometimes viewed it cynically. America was an exception to this mood, perhaps because of its new international power after the war: for one thing, the UK was left owing the USA $4.6 billion.Footnote 108 Berlin operetta had been more taken with modernity than Viennese operetta because Berlin was very much a modern city, whereas Vienna retained a certain nostalgia for the days of ‘alt Wien’ and its residents spoke fondly of times past. Yet, after the war, Platt and Becker suggest that Berlin operetta became conservative and indifferent to modernity: ‘the once-characteristic mix of localism and cosmopolitanism firmly positioned in terms of a confident negotiation of the modern gave way to spectaculars of a different kind – historical romances’.Footnote 109

There was usually more to a historically themed operetta, however, than mere sentimental romance. Indeed, Volker Klotz sees a lively return to the spirit of Offenbach in the ‘cheeky exuberance’ of Fall’s Madame Pompadour, and Christoph Dompke finds a camp element from the beginning.Footnote 110 It may be true that modernity lost its attraction to a certain extent, but there were exceptions: for instance, Kálmán’s Die Herzogin von Chicago, Abraham’ s Ball im Savoy, Straus’s Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will!, and Dostal’s Clivia. Finally, it may also be argued that the presence of African-American elements in operettas by Künneke, Granichstaedten, Kálmán, Abraham, and Benatzky was a continuing assertion of the modern, even when an operetta was set in the past (like Lady Hamilton and Im weißen Rössl).