1. Introduction

Soft deformable objects – e.g. cells and capsules – are ubiquitous in biology and biotechnology, serving as building blocks of complex interacting systems typically driven by external flows (Lac, Morel & Barthès-Biesel Reference Lac, Morel and Barthès-Biesel2007; Barthes-Biesel Reference Barthes-Biesel2016; Bah, Bilal & Wang Reference Bah, Bilal and Wang2020; Owen et al. Reference Owen2023). In computational studies, they serve as simplified analogues for more intricate biological cells – such as red blood cells and circulating tumour cells – helping researchers examine cellular behaviour and mechanics (Krüger Reference Krüger2012; Gekle Reference Gekle2016; Balogh et al. Reference Balogh, Gounley, Roychowdhury and Randles2021; Huet & Wachs Reference Huet and Wachs2023). Their widespread applications demand a comprehensive understanding of capsule properties, achieved through the combined strengths of theoretical, experimental and computational approaches (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Fischer, Farutin, Vlahovska, Harting and Misbah2018; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Singh, Schirrmann, Zhou, Chernyavsky and Juel2023). Recent advances highlight the efficacy of microfluidic systems in separating cells by size and deformability, enabling the enrichment of specific cell types and facilitating detailed characterisation (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Rorai, Mitra and Brandt2014; Häner et al. Reference Häner, Vesperini, Salsac, Le Goff and Juel2021; Lu et al. Reference Lu, Wang, Salsac, Barthès-Biesel, Wang and Sui2021; Waters Reference Waters2024).

Substantial research on capsule deformation and dynamics in non-inertial flows has arisen from their significance in microcirculation (e.g. capillary blood flow) and microfluidic applications. Early work by Barthès-Biesel and Rallison employed thin-shell theory to model elastic capsules in slow shear flows, assuming small deformations (Barthes-Biesel & Rallison Reference Barthes-Biesel and Rallison1981). Pozrikidis extended this approach using the boundary integral method to incorporate finite deformations, fluid viscosity variations and bending stresses (Pozrikidis Reference Pozrikidis1995, Reference Pozrikidis2001). More recently, Balogh and Bagchi used the front-tracking method to investigate red blood cell behaviour in complex networks resembling human microcirculation (Balogh & Bagchi Reference Balogh and Bagchi2017, Reference Balogh and Bagchi2018, Reference Balogh and Bagchi2019). Research has also addressed the mechanical and rheological properties of elastic capsule suspensions – through analytical, experimental and numerical methods – building on Batchelor’s foundational work on particle stress tensors (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1970; Barthes-Biesel & Rallison Reference Barthes-Biesel and Rallison1981; Ramanujan & Pozrikidis Reference Ramanujan and Pozrikidis1998; Walter, Rehage & Leonhard Reference Walter, Rehage and Leonhard2001). Subsequent studies explored rheological characteristics of elastic capsule suspensions in non-inertial regimes, elucidating the influence of the particle dynamics (Takeishi et al. Reference Takeishi, Rosti, Imai, Wada and Brandt2019), as well as the roles of strainhardening and membrane viscosity in the suspension rheology (Aouane, Scagliarini & Harting Reference Aouane, Scagliarini and Harting2021; Guglietta et al. Reference Guglietta, Pelusi, Sega, Aouane and Harting2023).

Deformable capsules exhibit nonlinear elastic behaviour, which gives rise to complex hydrodynamic interactions when they come into close proximity (Barthès-Biesel Reference Barthès-Biesel2009). When capsules come near each other, a thin liquid film may form between their membranes, which, under high shear forces, can result in membrane deformation or even damage (El Mertahi et al. Reference El Mertahi, Grandmaison, Dupont, Jellali, Brancherie and Salsac2024). The hydrodynamic interaction among these flowing objects can give rise to emergent non-equilibrium structures (Lushi, Wioland & Goldstein Reference Lushi, Wioland and Goldstein2014; Goto & Tanaka Reference Goto and Tanaka2015; Yeo, Lushi & Vlahovska Reference Yeo, Lushi and Vlahovska2015) such as log-rolling chains of rigid spheres aligned along the vorticity direction in shear flows (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Xu, Rice, Dinner and Cohen2012), spontaneous alignment in attractive emulsions and colloidal suspensions (Migler Reference Migler2001; Montesi, Peña & Pasquali Reference Montesi, Peña and Pasquali2004; Varga et al. Reference Varga, Grenard, Pecorario, Taberlet, Dolique, Manneville, Divoux, McKinley and Swan2019; Millett Reference Millett2024) and crystal-like arrangements in red blood cell suspensions (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Fischer, Farutin, Vlahovska, Harting and Misbah2018). Such emergent structures not only affect the short-range dynamics but also govern large-scale suspension behaviour, including aggregation, diffusion and rheology (Morris & Brady Reference Morris and Brady1996; Griffiths & Stone Reference Griffiths and Stone2012; Matsunaga et al. Reference Matsunaga, Imai, Yamaguchi and Ishikawa2016; Gai et al. Reference Gai, Huet, Gong and Wachs2025). Conversely, transition from deterministic to random behaviour when varying object deformability has already been reported in a few previous contexts such as red blood cell distributions within networks (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Plouraboué, Lintuvuori, Zhang, Abbasi and Misbah2023), or transition from a leapfrog motion (Lac & Barthès-Biesel Reference Lac and Barthès-Biesel2008) to the minuet dynamics (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Lei, Salsac and Barthès-Biesel2020) of binary capsule interactions.

Understanding binary hydrodynamic interactions is essential for studying capsule suspensions, due to their significant influence on capsule collective migration and rheological behaviours (Krüger Reference Krüger2012; Abbasi et al. Reference Abbasi, Farutin, Ez-Zahraouy, Benyoussef and Misbah2021). Lac et al. (Reference Lac, Morel and Barthès-Biesel2007) conducted the pioneering three-dimensional simulations of the binary interaction between a pair of spherical capsules in a shear flow, with their centres initially positioned on the same shear plane. It was shown that one capsule overpassed the other and shifted back to the flow axis as it moved away, which is referred to as leapfrog motion. The crossing results in an irreversible shift in the capsule trajectory along the shear gradient, which is believed to contribute to self-diffusion. The same configuration was revisited with two red blood cells (Omori et al. Reference Omori, Ishikawa, Imai and Yamaguchi2013) and vesicles (Gires et al. Reference Gires, Srivastav, Misbah, Podgorski and Coupier2014), where the leapfrog motion was also observed. Doddi & Bagchi used the front-tracking method to investigate the binary interaction of capsules in an inertial shear flow and found that, instead of crossing as in the zero Reynolds number case, inertia induces a reversed motion of capsules (Doddi & Bagchi Reference Doddi and Bagchi2008a ,Reference Doddi and Bagchi b ). This spiralling motion was attributed to the limited size of the computational domain. Pranay et al. (Reference Pranay, Anekal, Hernandez-Ortiz and Graham2010) considered the binary interaction of capsules in a polymeric fluid, showing that the trajectory shift can be decreased when the capsule deformability is low. Singh & Sarkar (Reference Singh and Sarkar2015) further elucidated that the stiffness ratio of the two capsules can affect the trajectory shift. Pair formation has been reported in inertial migration of both rigid and deformable particles in pipe flows, accompanied by a characteristic damped oscillatory dynamics during the pairing process which was attributed to inertial effects (Schaaf, Rühle & Stark Reference Schaaf, Rühle and Stark2019; Patel & Stark Reference Patel and Stark2021). Regarding capsule pair interactions, the pair stability has been shown to depend strongly on capsule softness, size, heterogeneity and initial relative position (Owen & Krüger Reference Owen and Krüger2022; Thota, Owen & Krüger Reference Thota, Owen and Krüger2023; Owen, Thota & Krüger Reference Owen, Thota and Krüger2024).

From another point of view, the binary interaction of capsules in different shear planes has been simulated and discussed by Lac & Barthès-Biesel (Reference Lac and Barthès-Biesel2008). In this case, a sideways leapfrog motion was noticed and then later confirmed for vesicles by Gires et al. (Reference Gires, Srivastav, Misbah, Podgorski and Coupier2014). Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Lei, Salsac and Barthès-Biesel2020) found a new interaction motion, the minuet motion, for the capsule pair initially closely positioned at two different shear planes. Within this interaction mode, the capsule pair can remain stable for a long time while dancing a minuet, especially for less deformable capsules. The minuet motion leads capsules to closely interact and deform significantly. When they separate, the two capsules can reverse direction. The reason for this minuet motion was attributed to the pressure evolution in the lubrication layer during the crossing and separating process.

Despite the insights gained, significant gaps persist in our understanding of the interaction mechanisms of a pair of capsules in different shear planes. In this study, we investigate the soft hydrodynamic interactions of spherical capsules and report a previously unrecognised capturing regime in the capsule dynamics. Unlike the leapfrog and minuet motions, this novel regime features the formation of a stable doublet, where the satellite capsule remains aligned with a reference capsule along the vorticity direction. Using high-fidelity, particle-resolved numerical simulations, we address the following key questions:

![]() $(i)$

Does a stable binary doublet exist, and what is the mechanism behind its formation?

$(i)$

Does a stable binary doublet exist, and what is the mechanism behind its formation?

![]() $(\textit{ii})$

How are the leapfrog, minuet and capturing regimes connected?

$(\textit{ii})$

How are the leapfrog, minuet and capturing regimes connected?

![]() $(\textit{iii})$

What insights can binary interactions provide for our understanding of the multi-body dynamics?

$(\textit{iii})$

What insights can binary interactions provide for our understanding of the multi-body dynamics?

This manuscript is organised as follows. Section 2 introduces the governing equations and the membrane model for deformable capsules. In § 3, we define the key physical quantities and the relevant dimensionless parameters. Section 4 describes the numerical set-up used for simulating binary capsule interactions. In § 5, we present the physical validation of the numerical solver. Section 6 analyses the binary interaction of deformable capsules in shear flow, focusing on interaction regimes, trajectories and deformations. We analyse the capturing regime through kinematic signatures and parametric sensitivity, and elucidate its gentle, stable nature. The mechanisms driving satellite capture and the resulting nonlinear hydrodynamic ordering and flow perturbations are discussed. Section 7 extends the discussion to ternary interactions of elastic capsules. Finally, § 8 summarises the main findings and outlines perspectives for future work.

2. Governing equations and membrane model

The capsule membrane

![]() $\varGamma$

is modelled as an infinitely thin interface, enclosing a region filled with an incompressible Newtonian fluid of constant viscosity and density. The motion of the fluid is governed by mass and momentum conservation

$\varGamma$

is modelled as an infinitely thin interface, enclosing a region filled with an incompressible Newtonian fluid of constant viscosity and density. The motion of the fluid is governed by mass and momentum conservation

Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tilde {u}}$

and

$\boldsymbol{\tilde {u}}$

and

![]() $\tilde {p}$

denote the flow velocity and pressure, respectively, and

$\tilde {p}$

denote the flow velocity and pressure, respectively, and

![]() $\tilde {\rho }$

is the fluid density. The kinematic viscosity is defined as

$\tilde {\rho }$

is the fluid density. The kinematic viscosity is defined as

![]() $\tilde {\nu } = \tilde {\mu }/\tilde {\rho }$

, with

$\tilde {\nu } = \tilde {\mu }/\tilde {\rho }$

, with

![]() $\tilde {\mu }$

being the dynamic viscosity. Dimensional quantities are denoted by a tilde (

$\tilde {\mu }$

being the dynamic viscosity. Dimensional quantities are denoted by a tilde (

![]() $\sim$

). We consider the Stokes regime and explicitly account for the elastic force acting on the membrane. The elastic force generates a localised stress into the fluid as a body force

$\sim$

). We consider the Stokes regime and explicitly account for the elastic force acting on the membrane. The elastic force generates a localised stress into the fluid as a body force

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tilde {f}_b}$

that reads

$\boldsymbol{\tilde {f}_b}$

that reads

where

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}} = (\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z})$

is the spatial coordinate, and

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}} = (\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z})$

is the spatial coordinate, and

![]() $\tilde {\delta }(\boldsymbol{\tilde {x}} - \boldsymbol{\tilde {x}_{0}})$

the Dirac distribution centred at position

$\tilde {\delta }(\boldsymbol{\tilde {x}} - \boldsymbol{\tilde {x}_{0}})$

the Dirac distribution centred at position

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tilde {x}_{0}}$

on the membrane surface, i.e.

$\boldsymbol{\tilde {x}_{0}}$

on the membrane surface, i.e.

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tilde {x}_{0}} \in \varGamma$

.

$\boldsymbol{\tilde {x}_{0}} \in \varGamma$

.

The shear and area-dilatation stresses in the membrane are modelled using thin-shell theory, which is briefly outlined here (for a comprehensive derivation, the reader is referred to Barthes-Biesel & Rallison Reference Barthes-Biesel and Rallison1981). In this study, the elastic behaviour of the membrane is described using the Skalak constitutive law for which the associated surface strain energy

![]() $\tilde {W_s}$

is given by

$\tilde {W_s}$

is given by

where

![]() $\tilde {E_s}$

is the membrane shear modulus and the two invariants

$\tilde {E_s}$

is the membrane shear modulus and the two invariants

![]() $I_{1,2}$

$I_{1,2}$

are related to

![]() $\lambda _{1,2}$

, the principal stretches along the two tangential directions. The area-dilatation modulus is set to

$\lambda _{1,2}$

, the principal stretches along the two tangential directions. The area-dilatation modulus is set to

![]() $C = 1$

, which penalises large changes in surface area (Pozrikidis Reference Pozrikidis1995). The membrane elastic stresses

$C = 1$

, which penalises large changes in surface area (Pozrikidis Reference Pozrikidis1995). The membrane elastic stresses

![]() $\tilde {\sigma }_{i,j}$

are then derived from the strain energy function

$\tilde {\sigma }_{i,j}$

are then derived from the strain energy function

![]() $\tilde {W_s}$

as

$\tilde {W_s}$

as

Once the membrane elastic stress tensor is obtained, the resulting elastic force exerted by the membrane on the surrounding fluid is computed as

3. Physical quantities and dimensionless numbers

In this study, we consider a pair of elastic capsules suspended in a Stokes flow subjected to simple shear. The capillary number is defined as

![]() $ {\mathcal{C}a} = \tilde {\mu } \tilde {\dot {\gamma }} \tilde {r}_0/\tilde {E_s}$

, where

$ {\mathcal{C}a} = \tilde {\mu } \tilde {\dot {\gamma }} \tilde {r}_0/\tilde {E_s}$

, where

![]() $\tilde {\mu }$

is the dynamic viscosity,

$\tilde {\mu }$

is the dynamic viscosity,

![]() $\tilde {\dot {\gamma }}$

is the shear rate,

$\tilde {\dot {\gamma }}$

is the shear rate,

![]() $\tilde {r}_0$

is the characteristic length scale (radius of the initial spherical capsule) and

$\tilde {r}_0$

is the characteristic length scale (radius of the initial spherical capsule) and

![]() $\tilde {E_s}$

is the elastic modulus of the capsule membrane. In a simple shear flow, the dimensional shear rate is defined as

$\tilde {E_s}$

is the elastic modulus of the capsule membrane. In a simple shear flow, the dimensional shear rate is defined as

![]() $\tilde {\dot {\gamma }} = \tilde {U}_0/\tilde {L}$

, where

$\tilde {\dot {\gamma }} = \tilde {U}_0/\tilde {L}$

, where

![]() $\tilde {U}_0$

is the imposed velocity difference between the two moving solid boundaries and

$\tilde {U}_0$

is the imposed velocity difference between the two moving solid boundaries and

![]() $\tilde {L}$

is the normal distance between the two moving solid boundaries, here, the side length of the cubic computational domain. The Reynolds number

$\tilde {L}$

is the normal distance between the two moving solid boundaries, here, the side length of the cubic computational domain. The Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}} = \tilde {\rho } \tilde {\dot {\gamma }} \tilde {r}_0^2/\tilde {\mu }$

is set to

${\textit{Re}} = \tilde {\rho } \tilde {\dot {\gamma }} \tilde {r}_0^2/\tilde {\mu }$

is set to

![]() $0.1$

. Inertia is neglected by omitting the convective term in the Navier–Stokes equations, as appropriate for Stokes flow. We analyse several physical quantities that characterise the binary interaction of capsules. These include capsule trajectory, velocity, acceleration, interaction frequency, deformation parameter (

$0.1$

. Inertia is neglected by omitting the convective term in the Navier–Stokes equations, as appropriate for Stokes flow. We analyse several physical quantities that characterise the binary interaction of capsules. These include capsule trajectory, velocity, acceleration, interaction frequency, deformation parameter (

![]() $D$

) and particle-induced stress (

$D$

) and particle-induced stress (

![]() $\varSigma ^p$

), among others. Below, we briefly describe the methods used to compute and non-dimensionalise these quantities.

$\varSigma ^p$

), among others. Below, we briefly describe the methods used to compute and non-dimensionalise these quantities.

The trajectory, velocity, acceleration and frequency are non-dimensionalised using the characteristic length scale

![]() $\tilde {r}_0$

, characteristic velocity scale

$\tilde {r}_0$

, characteristic velocity scale

![]() $\tilde {\dot {\gamma }}\tilde {r}_0$

and characteristic time scale

$\tilde {\dot {\gamma }}\tilde {r}_0$

and characteristic time scale

![]() $1/\tilde {\dot {\gamma }}$

. Capsule deformation is quantified using its moment of inertia tensor. Specifically, we consider an equivalent ellipsoid that shares the same inertia tensor,

$1/\tilde {\dot {\gamma }}$

. Capsule deformation is quantified using its moment of inertia tensor. Specifically, we consider an equivalent ellipsoid that shares the same inertia tensor,

![]() $\tilde {\mathcal{I}}$

, as the capsule. With the three eigenvalues (

$\tilde {\mathcal{I}}$

, as the capsule. With the three eigenvalues (

![]() $\tilde {\zeta }_1 \lt \tilde {\zeta }_2 \lt \tilde {\zeta }_3$

) of

$\tilde {\zeta }_1 \lt \tilde {\zeta }_2 \lt \tilde {\zeta }_3$

) of

![]() $\tilde {\mathcal{I}}$

, we can compute the semi-axis lengths:

$\tilde {\mathcal{I}}$

, we can compute the semi-axis lengths:

![]() $\tilde {r}_1, \tilde {r}_2$

and

$\tilde {r}_1, \tilde {r}_2$

and

![]() $\tilde {r}_3$

(Ramanujan & Pozrikidis Reference Ramanujan and Pozrikidis1998; Guglietta et al. Reference Guglietta, Pelusi, Sega, Aouane and Harting2023). Here,

$\tilde {r}_3$

(Ramanujan & Pozrikidis Reference Ramanujan and Pozrikidis1998; Guglietta et al. Reference Guglietta, Pelusi, Sega, Aouane and Harting2023). Here,

![]() $\tilde {r}_1$

and

$\tilde {r}_1$

and

![]() $\tilde {r}_3$

are the longest and shortest semi-axis lengths in the shear plane (

$\tilde {r}_3$

are the longest and shortest semi-axis lengths in the shear plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane), and

$y$

plane), and

![]() $\tilde {r}_2$

denotes the radius along the vorticity direction, along the axis normal to the shear plane (i.e.

$\tilde {r}_2$

denotes the radius along the vorticity direction, along the axis normal to the shear plane (i.e.

![]() $z$

-axis in our convention choice). The Taylor deformation factor is then defined as

$z$

-axis in our convention choice). The Taylor deformation factor is then defined as

The bulk excess stress of the capsule,

![]() $\varSigma ^p$

, is calculated following Batchelor’s formulation for Stokes flow (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1970). The particle stress tensor

$\varSigma ^p$

, is calculated following Batchelor’s formulation for Stokes flow (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1970). The particle stress tensor

![]() $\varSigma ^p$

, which accounts for capsule–capsule interactions, is computed using the Lagrangian nodal forces acting on the capsule surface, as described by Krüger (Reference Krüger2012) and Gross, Krüger & Varnik (Reference Gross, Krüger and Varnik2014)

$\varSigma ^p$

, which accounts for capsule–capsule interactions, is computed using the Lagrangian nodal forces acting on the capsule surface, as described by Krüger (Reference Krüger2012) and Gross, Krüger & Varnik (Reference Gross, Krüger and Varnik2014)

\begin{align} \tilde {\varSigma }_{\alpha \beta }^p = -\frac {1}{\tilde {V}} \sum _{i = 1}^{N}\sum _{j}^{N_{\textit{ele}}}\frac {1}{2} \big(\tilde {F}_\alpha ^{i,j}\tilde {r}_\beta ^{i,j} + \tilde {F}_\beta ^{i,j}\tilde {r}_\alpha ^{i,j} \big), \end{align}

\begin{align} \tilde {\varSigma }_{\alpha \beta }^p = -\frac {1}{\tilde {V}} \sum _{i = 1}^{N}\sum _{j}^{N_{\textit{ele}}}\frac {1}{2} \big(\tilde {F}_\alpha ^{i,j}\tilde {r}_\beta ^{i,j} + \tilde {F}_\beta ^{i,j}\tilde {r}_\alpha ^{i,j} \big), \end{align}

where

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $\beta$

denote Cartesian directions (

$\beta$

denote Cartesian directions (

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

or

$y$

or

![]() $z$

),

$z$

),

![]() $N$

is the number of capsules within the control volume

$N$

is the number of capsules within the control volume

![]() $\tilde {V}$

and

$\tilde {V}$

and

![]() $N_{\textit{ele}}$

is the number of triangular elements on each capsule surface. Here,

$N_{\textit{ele}}$

is the number of triangular elements on each capsule surface. Here,

![]() $\tilde {F}^{i,j}$

corresponds to the Lagrangian force acting on the node located at position vector

$\tilde {F}^{i,j}$

corresponds to the Lagrangian force acting on the node located at position vector

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{r}}^{i,j}$

. Specifically, the dimensionless particle shear stress, as well as the first and second normal stress differences, are defined as follows:

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{r}}^{i,j}$

. Specifically, the dimensionless particle shear stress, as well as the first and second normal stress differences, are defined as follows:

where

![]() $\phi _t$

denotes the total volume fraction of the capsules.

$\phi _t$

denotes the total volume fraction of the capsules.

4. Numerical method and set-up

The numerical set-up for the binary capsule interaction is depicted in figure 1. A simple shear flow is imposed along the

![]() $x$

-axis, characterised by a constant shear rate

$x$

-axis, characterised by a constant shear rate

![]() $\tilde {\dot {\gamma }} = \tilde {U}_0/\tilde {L} =1\, \textrm{s}^{-1}$

. The simulation is conducted within a cubic domain

$\tilde {\dot {\gamma }} = \tilde {U}_0/\tilde {L} =1\, \textrm{s}^{-1}$

. The simulation is conducted within a cubic domain

![]() $\mathcal{D}$

of edge length

$\mathcal{D}$

of edge length

![]() $\tilde {L} = 77\tilde {r}_0$

, where

$\tilde {L} = 77\tilde {r}_0$

, where

![]() $\tilde {r}_0$

is the radius of the reference (i.e. largest) capsule. The domain boundaries are aligned with the coordinate axes: left/right (

$\tilde {r}_0$

is the radius of the reference (i.e. largest) capsule. The domain boundaries are aligned with the coordinate axes: left/right (

![]() $x$

), top/bottom (

$x$

), top/bottom (

![]() $y$

) and front/back (

$y$

) and front/back (

![]() $z$

). Dirichlet conditions are imposed on the top and bottom boundaries to enforce a linear shear profile (topleft in figure 1), while periodic conditions are applied in the

$z$

). Dirichlet conditions are imposed on the top and bottom boundaries to enforce a linear shear profile (topleft in figure 1), while periodic conditions are applied in the

![]() $x$

- and

$x$

- and

![]() $z$

-directions. The complete set of boundary and initial conditions is detailed as follows:

$z$

-directions. The complete set of boundary and initial conditions is detailed as follows:

Figure 1. Schematic of a pair of capsules in simple shear flow within a cubic computational domain. A reference capsule (

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

) and a satellite capsule (

$\mathcal{C}_0$

) and a satellite capsule (

![]() $\mathcal{C}_2$

) are initially placed on the centre horizontal plane

$\mathcal{C}_2$

) are initially placed on the centre horizontal plane

![]() $y=0$

. (a) two-dimensional perspective of the numerical set-up, (b) mesh within the pink-marked region.

$y=0$

. (a) two-dimensional perspective of the numerical set-up, (b) mesh within the pink-marked region.

Two capsules of different radii are initially positioned on the same horizontal plane (but in distinct shear planes), centred at

![]() $y = 0$

within the computational domain. Figure 1 illustrates the octree mesh of the cubic computational domain (obtained using Basilisk (Popinet Reference Popinet2015)), and highlights the location of the capsule pair using a pink rectangular box. The initial dimensionless surface–surface distance between the two spherical capsules,

$y = 0$

within the computational domain. Figure 1 illustrates the octree mesh of the cubic computational domain (obtained using Basilisk (Popinet Reference Popinet2015)), and highlights the location of the capsule pair using a pink rectangular box. The initial dimensionless surface–surface distance between the two spherical capsules,

![]() $\mathcal{C}_i$

and

$\mathcal{C}_i$

and

![]() $\mathcal{C}_j$

, is denoted by

$\mathcal{C}_j$

, is denoted by

![]() $\varXi$

and defined as

$\varXi$

and defined as

where

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{X}}_i$

and

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{X}}_i$

and

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{X}}_{\kern-1.5pt j}$

are the position vectors of the capsule centres and

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{X}}_{\kern-1.5pt j}$

are the position vectors of the capsule centres and

![]() $\tilde {r}_i$

and

$\tilde {r}_i$

and

![]() $\tilde {r}_j$

are their respective radii. The initial alignment angle,

$\tilde {r}_j$

are their respective radii. The initial alignment angle,

![]() $\varPsi$

, is defined as the angle between the line connecting the capsule centres and the streamwise (

$\varPsi$

, is defined as the angle between the line connecting the capsule centres and the streamwise (

![]() $x$

) direction. Two-dimensional views are included in figure 1 to depict the

$x$

) direction. Two-dimensional views are included in figure 1 to depict the

![]() $(\varXi , \varPsi )$

coordinate system and clarify the orientation of the shear gradient. Within the pink box, the Eulerian fluid mesh is locally refined around the capsules to enhance resolution while maintaining computational efficiency. The capsule surface is discretised using Lagrangian points connected into triangular elements, offering an accurate representation of the membrane through the adaptive front-tracking method.

$(\varXi , \varPsi )$

coordinate system and clarify the orientation of the shear gradient. Within the pink box, the Eulerian fluid mesh is locally refined around the capsules to enhance resolution while maintaining computational efficiency. The capsule surface is discretised using Lagrangian points connected into triangular elements, offering an accurate representation of the membrane through the adaptive front-tracking method.

To accurately capture capsule deformation, we employ an octree-based adaptive mesh refinement strategy. The mass and momentum conservation equations, (2.1) and (2.2), are discretised in space using the finite volume method on an adaptive octree grid. This method, implemented within the open-source Basilisk platform (Popinet Reference Popinet2015), recursively subdivides cubic cells into eight smaller sub-cells in regions requiring higher resolution (Huet & Wachs Reference Huet and Wachs2023). The Cartesian octree grid dynamically adapts at each time step: it refines in areas with sharp changes in velocity gradients and coarsens where gradient variations are weak. In addition, to ensure accurate interaction between the fluid and the capsule membrane, the region surrounding each capsule is always enforced at the finest grid resolution. This high-resolution layer guarantees accurate force interpolation and velocity spreading between the Eulerian and Lagrangian grids in the immersed boundary method (see Appendix A). The grid hierarchy follows a binary refinement pattern, where the cell size decreases by a factor of two between successive refinement levels. As a result, the smallest cell size is given by

![]() $\Delta x = L / 2^{n_E}$

, with

$\Delta x = L / 2^{n_E}$

, with

![]() $n_E$

denoting the maximum Eulerian refinement level.

$n_E$

denoting the maximum Eulerian refinement level.

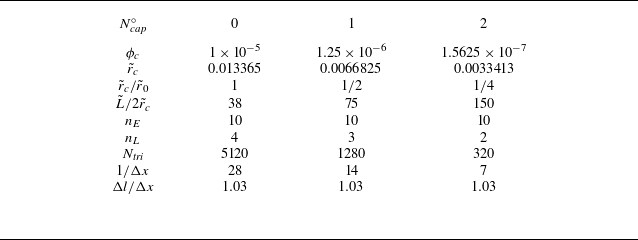

The detailed parameters employed in setting up the capsules and the corresponding mesh discretisation are summarised in table 1. We consider three capsule sizes: a large reference capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

with radius

$\mathcal{C}_0$

with radius

![]() $\tilde {r}_0 = 0.013$

and volume fraction

$\tilde {r}_0 = 0.013$

and volume fraction

![]() $\phi _0 = 1 \times 10^{-5}$

, a medium capsule

$\phi _0 = 1 \times 10^{-5}$

, a medium capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

with size ratio

$\mathcal{C}_1$

with size ratio

![]() $r_1 / r_0 = 1/2$

and a small capsule

$r_1 / r_0 = 1/2$

and a small capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_2$

with

$\mathcal{C}_2$

with

![]() $r_2 / r_0 = 1/4$

. To maintain consistent resolution across capsule sizes, the mesh refinement level

$r_2 / r_0 = 1/4$

. To maintain consistent resolution across capsule sizes, the mesh refinement level

![]() $n_L$

for capsules is selected such that the ratio of the surface element edge length to the smallest Eulerian grid size,

$n_L$

for capsules is selected such that the ratio of the surface element edge length to the smallest Eulerian grid size,

![]() $\Delta l / \Delta x$

, remains approximately unity. The spatial resolution for the large capsule

$\Delta l / \Delta x$

, remains approximately unity. The spatial resolution for the large capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

is set to

$\mathcal{C}_0$

is set to

![]() $1/\Delta x = 28$

(cells per initial capsule diameter), while the smallest capsule

$1/\Delta x = 28$

(cells per initial capsule diameter), while the smallest capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_2$

is resolved with

$\mathcal{C}_2$

is resolved with

![]() $1/\Delta x = 7$

. To resolve the lubrication layer during close binary interactions, a minimum of

$1/\Delta x = 7$

. To resolve the lubrication layer during close binary interactions, a minimum of

![]() $10$

Eulerian grid cells is maintained between the capsule surfaces at

$10$

Eulerian grid cells is maintained between the capsule surfaces at

![]() $\varXi \geqslant 2$

. These resolutions are demonstrated to be sufficient to capture the capsule dynamics, elastic deformation and hydrodynamic interactions (see Appendix B for more details).

$\varXi \geqslant 2$

. These resolutions are demonstrated to be sufficient to capture the capsule dynamics, elastic deformation and hydrodynamic interactions (see Appendix B for more details).

Table 1. Numerical set-ups for the capsule pair:

![]() $n_E$

and

$n_E$

and

![]() $n_L$

represent the refinement levels for the Eulerian and Lagrangian meshes;

$n_L$

represent the refinement levels for the Eulerian and Lagrangian meshes;

![]() $N_{\textit{tri}}$

, the number of triangles on the capsule surface;

$N_{\textit{tri}}$

, the number of triangles on the capsule surface;

![]() $\phi _c$

, the capsule volume fraction;

$\phi _c$

, the capsule volume fraction;

![]() $\tilde {r}_c$

, the capsule radius;

$\tilde {r}_c$

, the capsule radius;

![]() $\Delta x$

, the size of the smallest grid cell in the fluid domain; and

$\Delta x$

, the size of the smallest grid cell in the fluid domain; and

![]() $\Delta l$

, the average size of the surface triangles.

$\Delta l$

, the average size of the surface triangles.

Over 650 numerical simulations were performed for binary capsule interactions in shear flow. A large parameter space is investigated, including the capillary number

![]() $\mathcal{C}a$

, the initial surface–surface distance

$\mathcal{C}a$

, the initial surface–surface distance

![]() $\varXi$

, the alignment angle

$\varXi$

, the alignment angle

![]() $\varPsi$

and the capsule size ratios. Each simulation is performed over a sufficiently long time interval, until the dynamical behaviour of the capsules either ceases or reaches a steady state.

$\varPsi$

and the capsule size ratios. Each simulation is performed over a sufficiently long time interval, until the dynamical behaviour of the capsules either ceases or reaches a steady state.

5. Physical validation

Figure 2 presents a physical validation of our numerical solver for binary capsule interactions in a simple shear flow. We replicate the numerical set-up of Lac & Barthès-Biesel (Reference Lac and Barthès-Biesel2008) and adopt their notation in this section for the inter-capsule distances in the three coordinate directions:

![]() $\Delta x_1$

(streamwise,

$\Delta x_1$

(streamwise,

![]() $x$

),

$x$

),

![]() $\Delta x_2$

(sheargradient,

$\Delta x_2$

(sheargradient,

![]() $y$

) and

$y$

) and

![]() $\Delta x_3$

(vorticity,

$\Delta x_3$

(vorticity,

![]() $z$

), as illustrated in figure 2(a). Figure 2(b) shows the evolution of

$z$

), as illustrated in figure 2(a). Figure 2(b) shows the evolution of

![]() $\Delta x_2$

between two capsules initially positioned in different shear planes, with offsets ranging from

$\Delta x_2$

between two capsules initially positioned in different shear planes, with offsets ranging from

![]() $\Delta x^0_3 = 0.25$

to

$\Delta x^0_3 = 0.25$

to

![]() $1.25$

. The trajectories predicted by our simulations exhibit excellent agreement with the reference results of Lac & Barthès-Biesel (Reference Lac and Barthès-Biesel2008), accurately capturing both the transient dynamics and the asymptotic vertical separation. Key features such as the trajectory shape, the peak displacement and the final equilibrium spacing are all closely reproduced, demonstrating the accuracy and robustness of our solver. Further assessments of the numerical method – including deformation and dynamic behaviours of single capsules and capsule suspensions under both inertial and non-inertial shear flows – can be found in our previous work (Gai et al. Reference Gai, Huet, Gong and Wachs2025).

$1.25$

. The trajectories predicted by our simulations exhibit excellent agreement with the reference results of Lac & Barthès-Biesel (Reference Lac and Barthès-Biesel2008), accurately capturing both the transient dynamics and the asymptotic vertical separation. Key features such as the trajectory shape, the peak displacement and the final equilibrium spacing are all closely reproduced, demonstrating the accuracy and robustness of our solver. Further assessments of the numerical method – including deformation and dynamic behaviours of single capsules and capsule suspensions under both inertial and non-inertial shear flows – can be found in our previous work (Gai et al. Reference Gai, Huet, Gong and Wachs2025).

Figure 2. (a) Schematic of two capsules in a simple shear flow, as in the configuration studied by Lac & Barthès-Biesel (Reference Lac and Barthès-Biesel2008). (b) Evolution of

![]() $\Delta x_2$

against

$\Delta x_2$

against

![]() $\Delta x_1$

during the capsule interaction (

$\Delta x_1$

during the capsule interaction (

![]() $\Delta x^0_2 = 0.25$

). Present numerical results (solid lines) are compared with the reference data of Lac & Barthès-Biesel (Reference Lac and Barthès-Biesel2008) labelled LBB2008.

$\Delta x^0_2 = 0.25$

). Present numerical results (solid lines) are compared with the reference data of Lac & Barthès-Biesel (Reference Lac and Barthès-Biesel2008) labelled LBB2008.

6. Binary interaction

6.1. Binary interaction trajectories

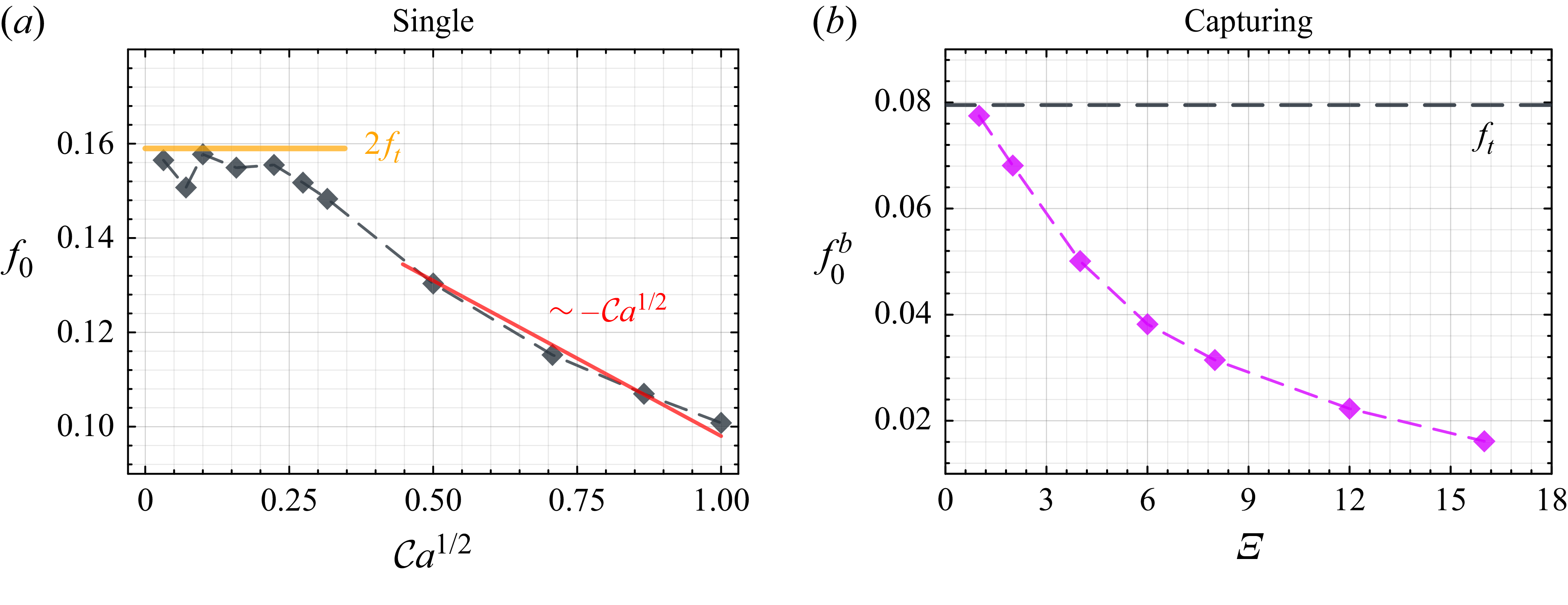

We begin by presenting the characteristic trajectories of capsules observed across the different binary interaction regimes examined in this study. Two capsules are initially positioned at the same horizontal plane

![]() $y=0$

, as indicated in figure 1. The regimes are defined based on the trajectory of the satellite capsule in a frame originating at the centroid of the reference capsule

$y=0$

, as indicated in figure 1. The regimes are defined based on the trajectory of the satellite capsule in a frame originating at the centroid of the reference capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

. Three types of capsule interaction are considered in this study: leapfrog (simple crossing), minuet motion and the newly identified stable capturing motion, as illustrated in figure 3.

$\mathcal{C}_0$

. Three types of capsule interaction are considered in this study: leapfrog (simple crossing), minuet motion and the newly identified stable capturing motion, as illustrated in figure 3.

-

(i) Leapfrog motion (

): satellite capsule approaches

): satellite capsule approaches

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, interacts and then separates. This is a typical and the most frequently observed motion in binary capsule systems and suspensions.

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, interacts and then separates. This is a typical and the most frequently observed motion in binary capsule systems and suspensions. -

(ii) Minuet motion (

): satellite capsule approaches

): satellite capsule approaches

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, engages in a dynamic interaction where it overpasses

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, engages in a dynamic interaction where it overpasses

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, reverses its direction to re-engage and repeats this interaction multiple times before eventually moving away.

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, reverses its direction to re-engage and repeats this interaction multiple times before eventually moving away. -

(iii) Capturing motion (

): satellite capsule accelerates to catch up with

): satellite capsule accelerates to catch up with

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, engaging in a periodic interaction with decreasing magnitude, drifting away from

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, engaging in a periodic interaction with decreasing magnitude, drifting away from

$\mathcal{C}_0$

until reaching a stable doublet with steady separation distance.

$\mathcal{C}_0$

until reaching a stable doublet with steady separation distance.

Figure 3. Trajectories of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

relative to

$\mathcal{C}_1$

relative to

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

in the (a,d) leapfrog, (b,e) minuet and (c, f) capturing regimes (

$\mathcal{C}_0$

in the (a,d) leapfrog, (b,e) minuet and (c, f) capturing regimes (

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

and

${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

and

![]() $\varXi = 2$

); with the contour of

$\varXi = 2$

); with the contour of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

(

$\mathcal{C}_0$

(

![]() $\bigcirc$

), the capsule trajectory (

$\bigcirc$

), the capsule trajectory (![]() ), the starting point at

), the starting point at

![]() $t_0$

(

$t_0$

(![]() ) and the simulation endpoint (

) and the simulation endpoint (![]() ). Panels show (a)

). Panels show (a)

![]() $\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

, (b)

$\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

, (b)

![]() $\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

, (c)

$\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

, (c)

![]() $\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

, (d)

$\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

, (d)

![]() $\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

, (e)

$\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

, (e)

![]() $\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

, (f)

$\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

, (f)

![]() $\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

.

$\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

.

Figure 3 illustrates representative relative trajectories of the medium satellite capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

interacting with the large reference capsule

$\mathcal{C}_1$

interacting with the large reference capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

at

$\mathcal{C}_0$

at

![]() $\varXi = 2$

and

$\varXi = 2$

and

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

, observed in both the

${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

, observed in both the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

planes. At

$z$

planes. At

![]() $\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

, where the capsules are aligned along the

$\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

, where the capsules are aligned along the

![]() $x$

-axis, the interaction follows a leapfrog pattern:

$x$

-axis, the interaction follows a leapfrog pattern:

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

passes over

$\mathcal{C}_1$

passes over

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

and quickly escapes downstream on a different horizontal plane (

$\mathcal{C}_0$

and quickly escapes downstream on a different horizontal plane (

![]() $y\lt 0$

) (figures 3

a, 3

d). As the alignment angle increases to

$y\lt 0$

) (figures 3

a, 3

d). As the alignment angle increases to

![]() $\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

, the interaction transitions to a minuet regime (figures 3

b, 3

e), where

$\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

, the interaction transitions to a minuet regime (figures 3

b, 3

e), where

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

performs multiple revolutions around

$\mathcal{C}_1$

performs multiple revolutions around

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

before eventually escaping with a modest deviation from the initial horizontal plane. Strikingly, at

$\mathcal{C}_0$

before eventually escaping with a modest deviation from the initial horizontal plane. Strikingly, at

![]() $\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

, we identify a previously unreported regime of capturing. As shown in figures 3(c) and 3(f), the satellite capsule exhibits an inward spiralling trajectory around

$\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

, we identify a previously unreported regime of capturing. As shown in figures 3(c) and 3(f), the satellite capsule exhibits an inward spiralling trajectory around

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

, with decreasing amplitude until it settles into a stable orbit. Different from the transient leapfrog and minuet regimes, this capturing motion persists indefinitely, with the satellite and central capsule remaining bounded in a stable configuration. The capturing mechanism relies on two distinct hydrodynamic interactions: one induces a quasi-planar oscillation that entrains the satellite capsule

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, with decreasing amplitude until it settles into a stable orbit. Different from the transient leapfrog and minuet regimes, this capturing motion persists indefinitely, with the satellite and central capsule remaining bounded in a stable configuration. The capturing mechanism relies on two distinct hydrodynamic interactions: one induces a quasi-planar oscillation that entrains the satellite capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

, while a weak net flow gradually shifts it along the

$\mathcal{C}_1$

, while a weak net flow gradually shifts it along the

![]() $z$

-axis, eventually moving it beyond the influence of

$z$

-axis, eventually moving it beyond the influence of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

. Ultimately, the satellite capsule re-enters the original horizontal plane (

$\mathcal{C}_0$

. Ultimately, the satellite capsule re-enters the original horizontal plane (

![]() $y = 0$

). The leapfrog interaction is rapid and dispersive, characterised by brief close interaction and immediate separation. Capturing is a stable, long-lived and gentle interaction, with distinct dynamic and kinematic signatures. Between them, the minuet regime exhibits a softly chaotic dynamics, where the satellite performs several revolutions around the reference capsule before escaping in an unpredictable direction.

$y = 0$

). The leapfrog interaction is rapid and dispersive, characterised by brief close interaction and immediate separation. Capturing is a stable, long-lived and gentle interaction, with distinct dynamic and kinematic signatures. Between them, the minuet regime exhibits a softly chaotic dynamics, where the satellite performs several revolutions around the reference capsule before escaping in an unpredictable direction.

6.2. Binary interaction regimes

Based on the interaction trajectories, we construct comprehensive regime maps for the three binary systems investigated:

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

–

$\mathcal{C}_0$

–

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

,

$\mathcal{C}_0$

,

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

–

$\mathcal{C}_0$

–

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

and

$\mathcal{C}_1$

and

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

–

$\mathcal{C}_0$

–

![]() $\mathcal{C}_2$

, at three capillary numbers,

$\mathcal{C}_2$

, at three capillary numbers,

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

,

${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

,

![]() $0.1$

and

$0.1$

and

![]() $1.0$

. Figure 4 illustrates the resulting binary interaction regimes as a function of alignment angle in the

$1.0$

. Figure 4 illustrates the resulting binary interaction regimes as a function of alignment angle in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

plane

$z$

plane

![]() $0^{\circ } \leqslant \varPsi \leqslant 180^{\circ }$

and the surface–surface distance

$0^{\circ } \leqslant \varPsi \leqslant 180^{\circ }$

and the surface–surface distance

![]() $1 \leqslant \varXi \leqslant 16$

. We investigate how the three binary interaction regimes–leapfrog, minuet and capturing–emerge, evolve and transition across the parameter space. Please note that both capsules have the same capillary number unless otherwise specifically mentioned. A symmetry is observed about

$1 \leqslant \varXi \leqslant 16$

. We investigate how the three binary interaction regimes–leapfrog, minuet and capturing–emerge, evolve and transition across the parameter space. Please note that both capsules have the same capillary number unless otherwise specifically mentioned. A symmetry is observed about

![]() $\varPsi = 90^{\circ }$

in all panels, indicating that the interaction motion is insensitive to whether the satellite capsule is initially positioned upstream of or downstream of the central capsule. The regimes are bounded by two extreme alignment angles: leapfrog motion consistently occurs at

$\varPsi = 90^{\circ }$

in all panels, indicating that the interaction motion is insensitive to whether the satellite capsule is initially positioned upstream of or downstream of the central capsule. The regimes are bounded by two extreme alignment angles: leapfrog motion consistently occurs at

![]() $\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

, while capturing emerges near

$\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

, while capturing emerges near

![]() $\varPsi = 90^{\circ }$

across all configurations. This localisation of capturing near

$\varPsi = 90^{\circ }$

across all configurations. This localisation of capturing near

![]() $\varPsi = 90^{\circ }$

highlights the strong directional dependence of the hydrodynamic capturing mechanism.

$\varPsi = 90^{\circ }$

highlights the strong directional dependence of the hydrodynamic capturing mechanism.

Figure 4. Binary interaction regime map as a function of

![]() $0^{\circ } \leqslant \varPsi \leqslant 180^{\circ }$

and

$0^{\circ } \leqslant \varPsi \leqslant 180^{\circ }$

and

![]() $1 \leqslant \varXi \leqslant 16$

; leapfrog regime (

$1 \leqslant \varXi \leqslant 16$

; leapfrog regime (![]() ), minuet regime (

), minuet regime (![]() ), capturing regime (

), capturing regime (![]() ). The numerical data points are given by yellow crosses (

). The numerical data points are given by yellow crosses (![]() ). Binary system (a)–(c)

). Binary system (a)–(c)

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

-

$\mathcal{C}_0$

-

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

, (d)–(f)

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, (d)–(f)

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

-

$\mathcal{C}_0$

-

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

, (g)–(i)

$\mathcal{C}_1$

, (g)–(i)

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

-

$\mathcal{C}_0$

-

![]() $\mathcal{C}_2$

. Panels show (a)

$\mathcal{C}_2$

. Panels show (a)

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

, (b)

${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

, (b)

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=0.1$

, (c)

${\mathcal{C}a}=0.1$

, (c)

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=1.0$

, (d)

${\mathcal{C}a}=1.0$

, (d)

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

, (e)

${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

, (e)

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=0.1$

, (f)

${\mathcal{C}a}=0.1$

, (f)

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=1.0$

, (g)

${\mathcal{C}a}=1.0$

, (g)

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

, (h)

${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

, (h)

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=0.1$

, (i)

${\mathcal{C}a}=0.1$

, (i)

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=1.0$

.

${\mathcal{C}a}=1.0$

.

In the size-symmetric system (

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

–

$\mathcal{C}_0$

–

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

), capturing appears prominently at

$\mathcal{C}_0$

), capturing appears prominently at

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

for large initial separations (

${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

for large initial separations (

![]() $\varXi \geqslant 6$

) and high alignment angles (

$\varXi \geqslant 6$

) and high alignment angles (

![]() $\varPsi \geqslant 75^{\circ }$

), while leapfrog dominates at low angles (

$\varPsi \geqslant 75^{\circ }$

), while leapfrog dominates at low angles (

![]() $\varPsi \leqslant 15^{\circ }$

). Minuet interactions emerge at intermediate angles (e.g.

$\varPsi \leqslant 15^{\circ }$

). Minuet interactions emerge at intermediate angles (e.g.

![]() $\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

) for close separations. As

$\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

) for close separations. As

![]() $\mathcal{C}a$

increases, deformability weakens the capturing regime: at

$\mathcal{C}a$

increases, deformability weakens the capturing regime: at

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.1$

, the capturing region contracts and the minuet regime expands significantly, especially at

${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.1$

, the capturing region contracts and the minuet regime expands significantly, especially at

![]() $\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

. At high deformability (

$\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

. At high deformability (

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a} = 1.0$

), leapfrog and minuet regimes dominate the map. Introducing sizeasymmetry in the

${\mathcal{C}a} = 1.0$

), leapfrog and minuet regimes dominate the map. Introducing sizeasymmetry in the

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

–

$\mathcal{C}_0$

–

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

system preserves most qualitative features observed in the size-symmetric case (

$\mathcal{C}_1$

system preserves most qualitative features observed in the size-symmetric case (

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

–

$\mathcal{C}_0$

–

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

). However, the smaller satellite capsule promotes more extensive minuet motions at intermediate

$\mathcal{C}_0$

). However, the smaller satellite capsule promotes more extensive minuet motions at intermediate

![]() $\varPsi$

under moderate deformability. This trend becomes more pronounced in the

$\varPsi$

under moderate deformability. This trend becomes more pronounced in the

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

–

$\mathcal{C}_0$

–

![]() $\mathcal{C}_2$

system, where the smallest capsule enhances minuet interactions even at smaller alignment angles (

$\mathcal{C}_2$

system, where the smallest capsule enhances minuet interactions even at smaller alignment angles (

![]() $\varPsi = 15^{\circ }$

to

$\varPsi = 15^{\circ }$

to

![]() $30^{\circ }$

) and expands this regime to a wider

$30^{\circ }$

) and expands this regime to a wider

![]() $\varPsi$

range as

$\varPsi$

range as

![]() $\mathcal{C}a$

increases. Across all configurations at

$\mathcal{C}a$

increases. Across all configurations at

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a} = 1.0$

, capturing becomes increasingly rare, occurring only near

${\mathcal{C}a} = 1.0$

, capturing becomes increasingly rare, occurring only near

![]() $\varPsi \approx 90^{\circ }$

. The emergence of this sustained capturing state reveals a novel mechanism for spontaneous pairing and even chain formation in deformable capsule suspensions.

$\varPsi \approx 90^{\circ }$

. The emergence of this sustained capturing state reveals a novel mechanism for spontaneous pairing and even chain formation in deformable capsule suspensions.

6.3. Flow topology in binary interactions

In order to further illustrate binary interactions, the flow streamlines and capsule deformation for the unsteady leapfrog and minuet motions are depicted in figure 5. Figure 5(a) depicts the leapfrog interaction, where a medium satellite capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

is initially positioned at

$\mathcal{C}_1$

is initially positioned at

![]() $\varXi = 1$

and

$\varXi = 1$

and

![]() $\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

relative to a large reference capsule

$\varPsi = 0^{\circ }$

relative to a large reference capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

. The flow field surrounding

$\mathcal{C}_0$

. The flow field surrounding

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

displays a symmetric quadrupolar structure in the out-of-plane velocity component

$\mathcal{C}_0$

displays a symmetric quadrupolar structure in the out-of-plane velocity component

![]() $v_z$

, characteristic of a stresslet disturbance in shear flow. As

$v_z$

, characteristic of a stresslet disturbance in shear flow. As

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

approaches

$\mathcal{C}_1$

approaches

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

, the streamlines near the two capsules markedly deform. A lubrication region forms in the narrowing gap, and the flow becomes strongly asymmetric. The intense hydrodynamic interaction leads to significant deformation of both capsules. As the interaction culminates, the satellite

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, the streamlines near the two capsules markedly deform. A lubrication region forms in the narrowing gap, and the flow becomes strongly asymmetric. The intense hydrodynamic interaction leads to significant deformation of both capsules. As the interaction culminates, the satellite

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

abruptly escapes from the vicinity of

$\mathcal{C}_1$

abruptly escapes from the vicinity of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

, heading towards the

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, heading towards the

![]() $-x$

direction – defining the hallmark leapfrog motion. After separation, a closed streamline loop emerges above

$-x$

direction – defining the hallmark leapfrog motion. After separation, a closed streamline loop emerges above

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

. This recirculation zone arises from the asymmetric stress distribution induced by capsule deformation, with residual influence of

$\mathcal{C}_1$

. This recirculation zone arises from the asymmetric stress distribution induced by capsule deformation, with residual influence of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

.

$\mathcal{C}_0$

.

Figure 5. Visualisation of the binary capsule interaction at

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

and flow streamline evolution during interaction in the horizontal plane at

${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

and flow streamline evolution during interaction in the horizontal plane at

![]() $z=0$

. The flow field is coloured by

$z=0$

. The flow field is coloured by

![]() $v_z$

; red for

$v_z$

; red for

![]() $v_z\gt 0$

and blue for

$v_z\gt 0$

and blue for

![]() $v_z \lt 0$

. (a) Leapfrog motion at

$v_z \lt 0$

. (a) Leapfrog motion at

![]() $\varXi =1$

and

$\varXi =1$

and

![]() $\varPsi =0^{\circ }$

. (b) Minuet motion at

$\varPsi =0^{\circ }$

. (b) Minuet motion at

![]() $\varXi =1$

and

$\varXi =1$

and

![]() $\varPsi =30^{\circ }$

.

$\varPsi =30^{\circ }$

.

Figure 5(b) illustrates the minuet interaction, where the satellite capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

is initially positioned at

$\mathcal{C}_1$

is initially positioned at

![]() $\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

relative to

$\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

relative to

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

. The initial flow field displays a quadrupolar structure around

$\mathcal{C}_0$

. The initial flow field displays a quadrupolar structure around

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

similar to that observed in the leapfrog regime (figure 5

a), although the interaction here is weaker, resulting in reduced deformation of both capsules. After the first encounter, the satellite capsule lacks sufficient velocity to escape. It is drawn back toward

$\mathcal{C}_0$

similar to that observed in the leapfrog regime (figure 5

a), although the interaction here is weaker, resulting in reduced deformation of both capsules. After the first encounter, the satellite capsule lacks sufficient velocity to escape. It is drawn back toward

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

by the perturbed flow field, clearly exhibiting the hallmark of a minuet motion. This is followed by a second encounter before

$\mathcal{C}_0$

by the perturbed flow field, clearly exhibiting the hallmark of a minuet motion. This is followed by a second encounter before

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

ultimately escapes along the

$\mathcal{C}_1$

ultimately escapes along the

![]() $x$

-direction. A defining feature of the minuet regime is the repeated reversals of the satellite capsule trajectory, often occurring multiple times before separation along an unpredictable direction. The number of reversals and the final escape direction are sensitive to initial conditions, rendering the soft–chaotic interaction dynamics. After separation, a closed streamline loop is observed just below

$x$

-direction. A defining feature of the minuet regime is the repeated reversals of the satellite capsule trajectory, often occurring multiple times before separation along an unpredictable direction. The number of reversals and the final escape direction are sensitive to initial conditions, rendering the soft–chaotic interaction dynamics. After separation, a closed streamline loop is observed just below

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

, slightly offset from its centre.

$\mathcal{C}_1$

, slightly offset from its centre.

Figure 6. Visualisation of capturing motion for binary capsules at

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

,

${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

,

![]() $\varXi = 1$

and

$\varXi = 1$

and

![]() $\varPsi = 60^\circ$

, with illustration of flow streamlines. The flow field is coloured by

$\varPsi = 60^\circ$

, with illustration of flow streamlines. The flow field is coloured by

![]() $v_z$

; red for

$v_z$

; red for

![]() $v_z\gt 0$

and blue for

$v_z\gt 0$

and blue for

![]() $v_z \lt 0$

. (a) Interaction dynamics in the

$v_z \lt 0$

. (a) Interaction dynamics in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

plane. (b) Motion of the satellite

$z$

plane. (b) Motion of the satellite

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

in the

$\mathcal{C}_1$

in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane passing through its centroid.

$y$

plane passing through its centroid.

By further increasing the alignment angle to

![]() $\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

, the binary system enters a long-lived capturing regime. The satellite capsule

$\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

, the binary system enters a long-lived capturing regime. The satellite capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

exhibits repeated reversals in its trajectory, orbiting around

$\mathcal{C}_1$

exhibits repeated reversals in its trajectory, orbiting around

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

in a closed loop. Figure 6(a) illustrates one full cycle of this interaction in the

$\mathcal{C}_0$

in a closed loop. Figure 6(a) illustrates one full cycle of this interaction in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

plane. At the beginning of the cycle (top left panel), the flow field around

$z$

plane. At the beginning of the cycle (top left panel), the flow field around

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

displays a characteristic quadrupolar structure. As

$\mathcal{C}_1$

displays a characteristic quadrupolar structure. As

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

moves forward, it accelerates and then slows down, reaching a deceleration phase during which a striking sign reversal of

$\mathcal{C}_1$

moves forward, it accelerates and then slows down, reaching a deceleration phase during which a striking sign reversal of

![]() $v_z$

is observed. This change in flow topology (green box) manifests as a switch in the sign of

$v_z$

is observed. This change in flow topology (green box) manifests as a switch in the sign of

![]() $v_z$

near the top left and bottom right quadrants of

$v_z$

near the top left and bottom right quadrants of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

proximity (from blue to red). The capsule is then pulled back and redirected toward

$\mathcal{C}_1$

proximity (from blue to red). The capsule is then pulled back and redirected toward

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

, completing the first reversal. A second reversal occurs shortly afterward, again marked by a reverse sign change in

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, completing the first reversal. A second reversal occurs shortly afterward, again marked by a reverse sign change in

![]() $v_z$

(red box), initiating another oscillation cycle. This closed-loop behaviour then repeats periodically. Compared with the leapfrog and minuet regimes, the capsule deformation here is even smaller. To complement this view, figure 6(b) shows the motion of

$v_z$

(red box), initiating another oscillation cycle. This closed-loop behaviour then repeats periodically. Compared with the leapfrog and minuet regimes, the capsule deformation here is even smaller. To complement this view, figure 6(b) shows the motion of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

in the

$\mathcal{C}_1$

in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane crossing its centroid, which traces the periphery of a localised recirculation zone, with a slight offset from the recirculation centre. This recirculation stems from the hydrodynamic disturbance induced by

$y$

plane crossing its centroid, which traces the periphery of a localised recirculation zone, with a slight offset from the recirculation centre. This recirculation stems from the hydrodynamic disturbance induced by

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

and plays a central role in sustaining the orbital motion. Although

$\mathcal{C}_0$

and plays a central role in sustaining the orbital motion. Although

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

maintains a periodic trajectory around

$\mathcal{C}_1$

maintains a periodic trajectory around

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

, its oscillation amplitude slowly decays over time as the pair gradually drifts along the vorticity direction. Together, they constitute a self-sustained, stable configuration.

$\mathcal{C}_0$

, its oscillation amplitude slowly decays over time as the pair gradually drifts along the vorticity direction. Together, they constitute a self-sustained, stable configuration.

6.4. Kinematic signatures of the capturing motion

To further elucidate the kinematic signatures of the capturing regime, we examine the velocity and acceleration profiles of the satellite capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

relative to

$\mathcal{C}_1$

relative to

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

. In the

$\mathcal{C}_0$

. In the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane, the velocity trajectory of

$y$

plane, the velocity trajectory of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

(figure 7

a) initially exhibits a transient phase, followed by a converging spiral with decreasing amplitude. This motion is approximately symmetric with respect to both the

$\mathcal{C}_1$

(figure 7

a) initially exhibits a transient phase, followed by a converging spiral with decreasing amplitude. This motion is approximately symmetric with respect to both the

![]() $v_x = 0$

and

$v_x = 0$

and

![]() $v_y = 0$

axes. As the initial surface distance

$v_y = 0$

axes. As the initial surface distance

![]() $\varXi$

increases from

$\varXi$

increases from

![]() $1$

to

$1$

to

![]() $8$

and

$8$

and

![]() $16$

(figures 7

b–7

c), the velocity magnitude of

$16$

(figures 7

b–7

c), the velocity magnitude of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

decreases significantly, and fewer cycles are required to reach the steady state. The acceleration evolution at

$\mathcal{C}_1$

decreases significantly, and fewer cycles are required to reach the steady state. The acceleration evolution at

![]() $\varXi = 1$

, shown in figure 7(d), follows a similar inward spiral, with gradually diminishing oscillations that eventually converge to an equilibrium point. The final velocity is marked by a blue square at the origin of the

$\varXi = 1$

, shown in figure 7(d), follows a similar inward spiral, with gradually diminishing oscillations that eventually converge to an equilibrium point. The final velocity is marked by a blue square at the origin of the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane. Along the vorticity direction (

$y$

plane. Along the vorticity direction (

![]() $z$

-axis), the velocity profile of

$z$

-axis), the velocity profile of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

in the

$\mathcal{C}_1$

in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

plane (figure 7

e) exhibits an oscillatory path resembling a distorted figureeight, slightly skewed toward the positive

$z$

plane (figure 7

e) exhibits an oscillatory path resembling a distorted figureeight, slightly skewed toward the positive

![]() $v_z$

direction, reflecting a slow net drift along the

$v_z$

direction, reflecting a slow net drift along the

![]() $z$

-axis. This trend is mirrored in the corresponding acceleration phase portrait (figure 7

f), which exhibits asymmetric oscillations along

$z$

-axis. This trend is mirrored in the corresponding acceleration phase portrait (figure 7

f), which exhibits asymmetric oscillations along

![]() $z$

-axis and ultimately relaxes to

$z$

-axis and ultimately relaxes to

![]() $a_z = 0$

. Together, these kinematic signatures confirm that the capturing regime is governed by a damped, quasi-periodic evolution toward a stable configuration, accompanied by a slow axial drift away from the reference capsule.

$a_z = 0$

. Together, these kinematic signatures confirm that the capturing regime is governed by a damped, quasi-periodic evolution toward a stable configuration, accompanied by a slow axial drift away from the reference capsule.

Figure 7. Velocity and acceleration evolution of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

relative to

$\mathcal{C}_1$

relative to

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

in the capturing regime (

$\mathcal{C}_0$

in the capturing regime (

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

and

${\mathcal{C}a} = 0.01$

and

![]() $\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

); with the starting point at

$\varPsi = 60^{\circ }$

); with the starting point at

![]() $t_0$

(

$t_0$

(![]() ) and the simulation endpoint (

) and the simulation endpoint (![]() ). Panels show (a)

). Panels show (a)

![]() $\varXi = 1$

, (b)

$\varXi = 1$

, (b)

![]() $\varXi = 8$

, (c)

$\varXi = 8$

, (c)

![]() $\varXi = 16$

, (d)

$\varXi = 16$

, (d)

![]() $\varXi = 1$

, (e)

$\varXi = 1$

, (e)

![]() $\varXi = 1$

, (f)

$\varXi = 1$

, (f)

![]() $\varXi = 1$

.

$\varXi = 1$

.

6.5. Parametric influence on capsule capturing

6.5.1. Effects of initial spacing

What drives the transition from minuet motion to the capturing regime? An important controlling factor is the initial spacing

![]() $\varXi$

. We examine the trajectories of the satellite capsule

$\varXi$

. We examine the trajectories of the satellite capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

at a fixed inclination angle

$\mathcal{C}_1$

at a fixed inclination angle

![]() $\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

while varying the initial inter-capsule spacing

$\varPsi = 30^{\circ }$

while varying the initial inter-capsule spacing

![]() $\varXi$

(figure 8). At small spacing

$\varXi$

(figure 8). At small spacing

![]() $\varXi =1$

, the satellite exhibits a minuet motion characterised by a single reversal around

$\varXi =1$

, the satellite exhibits a minuet motion characterised by a single reversal around

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

before escaping downstream, as seen in the

$\mathcal{C}_0$

before escaping downstream, as seen in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

planes (figures 8

a–

8

b). As the distance increases to

$z$

planes (figures 8

a–

8

b). As the distance increases to

![]() $\varXi = 6$

, the trajectory becomes more tightly confined in the

$\varXi = 6$

, the trajectory becomes more tightly confined in the

![]() $y$

-direction, and

$y$

-direction, and

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

now completes up to three revolutions before detaching. The reduced

$\mathcal{C}_1$

now completes up to three revolutions before detaching. The reduced

![]() $y$

-excursion corresponds to lower velocities of

$y$

-excursion corresponds to lower velocities of

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

, allowing more sustained interaction with

$\mathcal{C}_1$

, allowing more sustained interaction with

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

. A further increase to

$\mathcal{C}_0$

. A further increase to

![]() $\varXi = 8$

marks a critical transition: the minuet behaviour gives way to a stable capturing regime. As shown by the orange trajectory in figure 8(a), the path remains enveloped within the previous blue trajectory at

$\varXi = 8$

marks a critical transition: the minuet behaviour gives way to a stable capturing regime. As shown by the orange trajectory in figure 8(a), the path remains enveloped within the previous blue trajectory at

![]() $\varXi =6$

, indicating a tighter, more bounded interaction. In the

$\varXi =6$

, indicating a tighter, more bounded interaction. In the

![]() $y$

–

$y$

–

![]() $z$

plane (figure 8

c), a characteristic feature of the minuet motion (at

$z$

plane (figure 8

c), a characteristic feature of the minuet motion (at

![]() $\varXi = 1$

and

$\varXi = 1$

and

![]() $6$

) is that the satellite capsule approaches the shear plane of the reference

$6$

) is that the satellite capsule approaches the shear plane of the reference

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

(

$\mathcal{C}_0$

(

![]() $z=0$

) during interaction. In contrast, in the capturing regime at

$z=0$

) during interaction. In contrast, in the capturing regime at

![]() $\varXi = 8$

, the satellite capsule

$\varXi = 8$

, the satellite capsule

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

steadily drifts away from the

$\mathcal{C}_1$

steadily drifts away from the

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

while undergoing damped oscillations, thereby reducing the risk of destabilising contact. We see that the emergence of the capturing regime requires sufficient initial spacing between the two capsules. Too close, and the interaction becomes excessively strong and potentially unstable; too far, and the interaction weakens and capturing cannot be sustained. For instance, in a

$\mathcal{C}_0$

while undergoing damped oscillations, thereby reducing the risk of destabilising contact. We see that the emergence of the capturing regime requires sufficient initial spacing between the two capsules. Too close, and the interaction becomes excessively strong and potentially unstable; too far, and the interaction weakens and capturing cannot be sustained. For instance, in a

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

–

$\mathcal{C}_0$

–

![]() $\mathcal{C}_2$

system at

$\mathcal{C}_2$

system at

![]() ${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

,

${\mathcal{C}a}=0.01$

,

![]() $\varXi = 60$

and

$\varXi = 60$

and

![]() $\varPsi = 60^\circ$

, we observe a direct separation. A moderate spacing enables sustained hydrodynamic entrainment without premature separation.

$\varPsi = 60^\circ$

, we observe a direct separation. A moderate spacing enables sustained hydrodynamic entrainment without premature separation.

Figure 8. Regime transition from the minuet to the capturing regime for the

![]() $\mathcal{C}_0$

–

$\mathcal{C}_0$

–

![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$

system with increasing surface distance

$\mathcal{C}_1$

system with increasing surface distance

![]() $\varXi = 1\sim 8$

. Binary system at

$\varXi = 1\sim 8$

. Binary system at

![]() $\varPsi =30^{\circ }$

and

$\varPsi =30^{\circ }$

and