Introduction

Care home residents were especially vulnerable to severe effects from COVID-19 infection and experienced high levels of mortality, particularly in the early stages of the pandemic (Bone et al., Reference Bone, Finucane, Leniz, Higginson and Sleeman2020; Schultze et al., Reference Schultze, Nightingale, Evans, Hulme, Rosello, Bates, Cockburn, MacKenna, Curtis, Morton, Croker, Bacon, McDonald, Rentsch, Bhaskaran, Mathur, Tomlinson, Williamson, Forbes, Tazare, Grint, Walker, Inglesby, DeVito, Mehrkar, Hickman, Davy, Ward, Fisher, Green, Wing, Wong, McManus, Parry, Hester, Harper, Evans, Douglas, Smeeth, Eggo, Goldacre and Leon2022). Reflecting this, many countries introduced care home visiting restrictions to limit transmission. While arrangements varied between countries, restrictions were often extensive and prolonged (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Brown and Fergeson2022). The extent of these restrictions, relative to those in wider society, has drawn fresh attention to rights-based approaches to care, in which care home residents are viewed not just as passive recipients of care but as active rights-holders (Emmer De Albuquerque Green et al., Reference Emmer De Albuquerque Green, Tinker and Manthorpe2022) with the concept of autonomy fundamental to such approaches.

We conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with 27 family carers of people, predominantly with dementia, living in a care home in England during the pandemic with a view to understanding how residents’ autonomy was impacted by restrictions and how it could be supported in such challenging circumstances. We focused on the idea of ‘relational autonomy’, which understands autonomy to be realised and supported, or limited, by relationships and social arrangements. Following Mackenzie (Reference Mackenzie, Veltman and Piper2014), we conceptualised relational autonomy using the capability approach (Sen, Reference Sen1974, Reference Sen1979a, Reference Sen1979b).

Our findings contribute to a small international literature about family carers’ experiences of care home restrictions (Hartigan et al., Reference Hartigan, Kelleher, McCarthy and Cornally2021; Nash et al., Reference Nash, Harris, Heller and Mitchell2021; Chu et al., Reference Chu, Yee and Stamatopoulos2022, Reference Chu, Yee and Stamatopoulos2023; Cornally et al., Reference Cornally, Kilty, Buckley, O'Caoimh, O'Donovan, Monahan, O'Connor, Fitzgerald and Hartigan2022; Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, de Boer, Gabbay, Marlow, Stoop, Gerritsen and Verbeek2022; Hanna et al., Reference Hanna, Cannon, Gabbay, Marlow, Mason, Rajagopal, Shenton, Tetlow and Giebel2022; Chirico et al., Reference Chirico, Pappadà, Giebel, Ottoboni, Valente, Gabbay and Chattat2023; Dolberg et al., Reference Dolberg, Lev and Even-Zahav2023; Herron et al., Reference Herron, Runacres, Danton and Beardmore2023). To meet policy needs during the pandemic, these were commonly rapidly conducted and descriptive, and four papers drew upon two datasets, in the United Kingdom (UK) and Canada. Uniquely, our study examines family carers’ experiences within a conceptual framework that draws upon human rights concepts and, specifically, that of relational autonomy. This concept is increasingly seen as key for long-term care research and policy but remains significantly under-developed (Gómez-Vírseda et al., Reference Gómez-Vírseda, de Maeseneer and Gastmans2019). Our study is also one of few in long-term care employing the capability approach (Pirhonen, Reference Pirhonen2015; Melander et al., Reference Melander, Sävenstedt, Wälivaara and Olsson2018; van Loon et al., Reference van Loon, van Leeuwen, Ostelo, Bosmans and Widdershoven2018), addressing calls for wider application of this approach within ageing research (World Health Organization, 2015; Archard et al., Reference Archard, Afolabi, Baxi, Brayne, Burall, Butler-Cole, Challenger, Chambers, Coggon, Flinter, Gadd, Kerr, Reiss, Starling, Stellman, Suleman and Tansey2023).

Background

Care home visiting restrictions in England during the COVID-19 pandemic

During the initial months of the pandemic, care home visiting in England was limited to online or window ‘visits’, with few potential exceptions, e.g. visiting at end of life. In-person visits, when permitted, involved restrictions such as Perspex screens, physical distancing, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), named visitors and appointment systems. These visits were sometimes confusing and distressing for care home residents with dementia (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023), who account for around 80 per cent of residents (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2022). Residents also had to self-isolate following outside visits, including hospital appointments. From March 2021, care homes could designate family carers, ‘essential care-givers’, enabling them to visit regularly subject to observing staff protocols (Rights for Residents, 2022). However, not all care homes did so and restrictive policies or so-called ‘blanket bans’ were common (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023). In January 2022, national guidance recommended unrestricted visiting, although reports continued of care homes excluding or limiting visitors (UK Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, 2022). Concerns were expressed, including in a prospective legal challenge and a UK Parliamentary Joint Committee report, that visiting restrictions were disproportionate and inadequately respected human rights (Rimmer, Reference Rimmer2020; Liddell et al., Reference Liddell, Ruck Keene, Holland, Huppert, Underwood, Clark and Barclay2021; Low et al., Reference Low, Hinsliff-Smith, Sinha, Stall, Verbeek, Siette, Dow, Backhaus, Devi, Spilsbury, Brown, Griffiths, Bergman and Comas-Herrera2021; UK Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, 2021).

The importance of autonomy in frameworks of human rights and bioethics

Autonomy involves being able to live one's life without undue imposition and in accord with one's beliefs, values and preferences (Christman, Reference Christman, Zalta and Nodelman2020). It underpins multiple rights in the Human Rights Act (1998) including to life (Article 2), liberty and security (Article 5) and a private and family life (Article 8) (Samanta and Samanta, Reference Samanta and Samanta2005), and is one of the FREDA principles (alongside fairness, respect, equality and dignity) that summarise key values from the Act for UK-based health and care practitioners (Curtice and Exworthy, Reference Curtice and Exworthy2010). Autonomy is also the foremost principle, alongside beneficence, non-maleficence and justice, in the main framework of bioethics used within Western health and care systems (Beauchamp and Childress, Reference Beauchamp and Childress2001). Restrictions to usual autonomy may be justified in the context of a public health or other emergency but should be proportionate, subject to regular review and undertaken in consultation with those whose rights are affected (Hepple et al., Reference Hepple, Smith, Brownsword, Calman, Harding, Harper, Harries, Hill, Holm, Kaletsky, Knight, Krebs, Lipton, Murdoch, Parry, Perry, Plant and Rose2007; Chetty et al., Reference Chetty, Dalrymple and Simmons2012; Spadaro, Reference Spadaro2020). Respect for autonomy is especially important in long-term care settings given residents’ high levels of dependence and potential vulnerability (Collopy, Reference Collopy1988; McCormick, Reference McCormick2011; Birtha et al., Reference Birtha, Rodrigues, Zólyomi, Sandu and Schulmann2019; Care Quality Commission, 2019a; Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Cyhlarova, Comas-Herrera and Lorenz-Dant2021; van Loon et al., Reference van Loon, Luijkx, Janssen, Rooij and Janssen2021; UK Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, 2022).

The limitations of traditional autonomy concepts

Traditionally, respect for autonomy is a liberal concept, emphasising individual freedom and non-interference. While the concept has been useful for protecting people from coercion or unwarranted paternalism, it has also been criticised for being under-socialised (i.e. taking insufficient account of social context), excluding or marginalising people who are dependent or lack decisional capacity, and focusing on episodic decision-making rather than the overall circumstances of people's lives (Agich, Reference Agich1990; Nuffield Council on Bioethics, 2009; Cahil, Reference Cahil2018; Davy, Reference Davy2019; Moilanen et al., Reference Moilanen, Kangasniemi, Papinaho, Mynttinen, Siipi, Suominen and Suhonen2021; Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Greenhill, Butchard and Day2021; Stoljar, Reference Stoljar, Zalta and Nodelman2022). It has also been deemed ‘ill-suited’ to navigating situations of infection risk during the COVID-19 pandemic, where individual choices and preferences have necessarily been subordinated to public interests (Jeffrey, Reference Jeffrey2020; Gómez-Vírseda and Usanos, Reference Gómez-Vírseda and Usanos2021).

The development of relational autonomy concepts in theory and practice

There is wide agreement that more relational models of autonomy are needed, in which autonomy is understood as realised and supported, and sometimes limited, through relationships and social arrangements. Practically, support for autonomy can include emotional or practical support, advocacy, personalised care, constitutive personal relationships and supportive social arrangements (Mackenzie, Reference Mackenzie, Veltman and Piper2014). The concept of relational autonomy, however, remains under-developed, theoretically diverse and non-unified, with systemisation or clarification of the concept's main characteristics lacking (Delgado, Reference Delgado2019; Gómez-Vírseda and Usanos, Reference Gómez-Vírseda and Usanos2021). A focus on relational and social contexts also means that relational autonomy needs to be conceived in a way that is flexible and adaptable to different contexts and settings (Gómez-Vírseda et al., Reference Gómez-Vírseda, de Maeseneer and Gastmans2019; Moilanen et al., Reference Moilanen, Kangasniemi, Papinaho, Mynttinen, Siipi, Suominen and Suhonen2021).

Relational autonomy is also under-developed in law and practice, although aspects of the concept are increasingly reflected in guidelines and regulatory standards for long-term care. For example, in the UK, the Care Quality Commission (2019b), the independent regulator of health and social care in England, states that residents’ family and personal relationships, and privacy, should be respected and that family members should be able to help plan care for, and support, their relative. However, some have questioned the force of these standards. Framed largely in terms of ‘person-centred care’ (Care Quality Commission, 2022) and ‘dignity’ (Care Quality Commission, 2023), they have been criticised for being contingent on ‘the enlightenment of policy makers’ and ‘the goodwill of practitioners’ rather than grounded in ideas of rights and citizenship (McCormick, Reference McCormick2011; Butchard and Kinderman, Reference Butchard and Kinderman2019). Similar challenges are observed internationally (European Network of National Human Rights Institutions, 2017; Birtha et al, Reference Birtha, Rodrigues, Zólyomi, Sandu and Schulmann2019). Arguably, this lack of force was evidenced by how readily these standards fell away during the pandemic. For example, in the UK, the Care Quality Commission paused its regulatory activities in care homes early on and was considered by a UK Parliamentary Joint Committee insufficiently responsive to families’ concerns about visiting policies (UK Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, 2021). Similar limitations were seen internationally. In the United States of America, for example, processes for responding to complaints raised by residents or family members and regulatory visits to nursing homes by state surveyors and ombudsmen were completely suspended.Footnote 1

Conceptualising relational autonomy using the capability approach

To conceptualise relational autonomy for this study, we use the capability approach. Catriona Mackenzie (Reference Mackenzie, Mackenzie, Rogers and Dodds2013) argues that this provides the strongest foundation for conceptualising relational autonomy. The capability approach is a normative framework of social justice originally developed by Sen (Reference Sen1974, Reference Sen1979a, Reference Sen1979b). It frames autonomy in terms of people having sufficient meaningful opportunities (capabilities) to do and be what they value (functionings), while taking account of the personal, relational, social and environmental factors (conversion factors) that restrict or support such capabilities (Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2005; Robeyns and Morten-Fibieger, Reference Robeyns, Morten-Fibieger, Zalta and Nodelman2023). These conversion factors are especially important to consider for potentially vulnerable populations who, without relational, social and other support, may be unable to achieve important functionings at all (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2003). Mackenzie draws also upon Elizabeth Anderson's capability-based theory of democratic equality (Anderson, Reference Anderson1999) to argue that systematic inequalities in capabilities fundamentally impact people's participation as citizens, thus emphasising the importance of a rights-based understanding of autonomy.

Aims and objectives

In this study, adopting a human rights-based perspective, we address the following research questions:

• How did family carers of care home residents in England experience care home visiting restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic?

• How was resident autonomy (conceived of relationally, in terms of capabilities and from the perspective of family carers) impacted by care home visiting restrictions?

• How can the autonomy of care home residents and family care-givers be supported, including in challenging circumstances such as those of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methods

Research design and conceptual framework

We conducted qualitative research based on in-depth interviews with 27 family carers of people living in a care home, predominantly with dementia, in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviews with family carers were conducted online since the circumstances of the pandemic mitigated against in-person interviews. While data from residents would have been helpful, this was not feasible to collect because of the impact of pandemic-related restrictions and challenges of method given the high prevalence of dementia amongst care home residents. We used a relational autonomy lens, conceptualised using the capability approach. This informed our research questions, data collection and analysis, with the aim of facilitating, ‘well-nuanced distinctions’ between phenomena, actions and measures ‘that support and that undermine autonomy’ (Entwistle et al., Reference Entwistle, Carter, Cribb and McCaffery2010: 741). Following Corbin and Strauss (Reference Corbin and Strauss2008), our ontological position is relativist and our epistemological position pragmatic.

The study formed part of a larger study, which also involved in-depth research with care home managers. We were advised by a well-appointed advisory group comprising care home managers, providers of health services to care home residents, and representatives of care home providers and dementia and service-user charities. We were also advised by an experts-by-experience group comprised of four family carers with a close relative living in a care home during the pandemic, who were supported by the study's involvement manager.

Sampling and recruitment

We recruited a purposive sample of 27 family carers through multiple routes. These included Care England (a national membership organisation of care home providers); 120 care homes participating in associated research (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023); the study's involvement manager and experts-by-experience group; multiple large care home groups; a range of representative organisations and charitable groups; and a public call-out on X (formerly known as Twitter), which was retweeted by partners over 70 times. In the absence of a sampling frame, multiple sources for recruitment help to ensure range and diversity. Those expressing interest in participation (N = 46) were screened in relation to criteria against which we sought maximum variation, including gender, relationship to resident, geographical area, type and size of care home, ethnicity and LGBTQI+ status. We also recorded resident's dementia status, length of residency and whether alive or deceased at the time of the interview. Using methods informed by interpretive grounded theory, recruitment was undertaken iteratively, alongside data collection and analysis. Those meeting criteria were provided an information sheet, invited to ask questions and, if willing, an online interview was scheduled. Ethical approval was provided by the HRA Social Research Ethics Committee.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted online between August 2022 and February 2023, mostly with two researchers (one leading), to allow shadowing and facilitate rapid reflections. Interviews ranged between 54 and 80 minutes and were audio-recorded with permission. A topic guide was developed with input and advice from the experts-by-experience group. This was used to ensure coverage but employed flexibly to allow participants to discuss issues of salience in ways that made sense to them, and to permit in-depth and responsive probing. For the full topic guide, see the Appendix. The period of interest covered March 2020 up until January 2022. Interviewers were trained and experienced in conducting sensitive and potentially distressing interviews, including online (Thunberg and Arnell, Reference Thunberg and Arnell2022).

Data analysis

Interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically using NVivo software and methods informed by interpretive grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008). While relevant concepts (e.g. dimensions of relational autonomy discussed in the literature) informed initial coding, these prior categories and concepts did not determine or restrict coding or analysis, which was primarily inductive. We employed ‘open’ coding, with data coded descriptively at a high level of granularity, and then various levels of ‘axial’ coding, grouping open codes in ways that illuminated relationships between them. Axial coding was undertaken using strategies suggested by Corbin and Strauss, including asking what, why and how questions, and identifying phrases or concepts that stood out as significant (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008). Both researchers coded data. Analytical notes were generated within NVivo and frequent meetings were used to resolve and develop the coding structure and associated conceptual ideas. Using a process of constant comparison, new data were used to develop the analysis, with codes generated or adjusted as necessary. A codebook was produced and regularly updated. While this iterative ‘grounded’ approach allowed for ongoing adjustments to sampling and interview strategies, the strategy of sampling for maximum variation was maintained throughout and the flexible and in-depth nature of the interviews meant that no specific adjustments to the interview strategy were necessary. The constant comparative method adopted, however, did enable the researchers to approach later interviews with a rich and evolving understanding of emerging themes and with increased theoretical and analytic sensitivity. Analysis and interpretation of the data were also discussed in a meeting with the study's advisory group and experts-by-experience group.

Findings

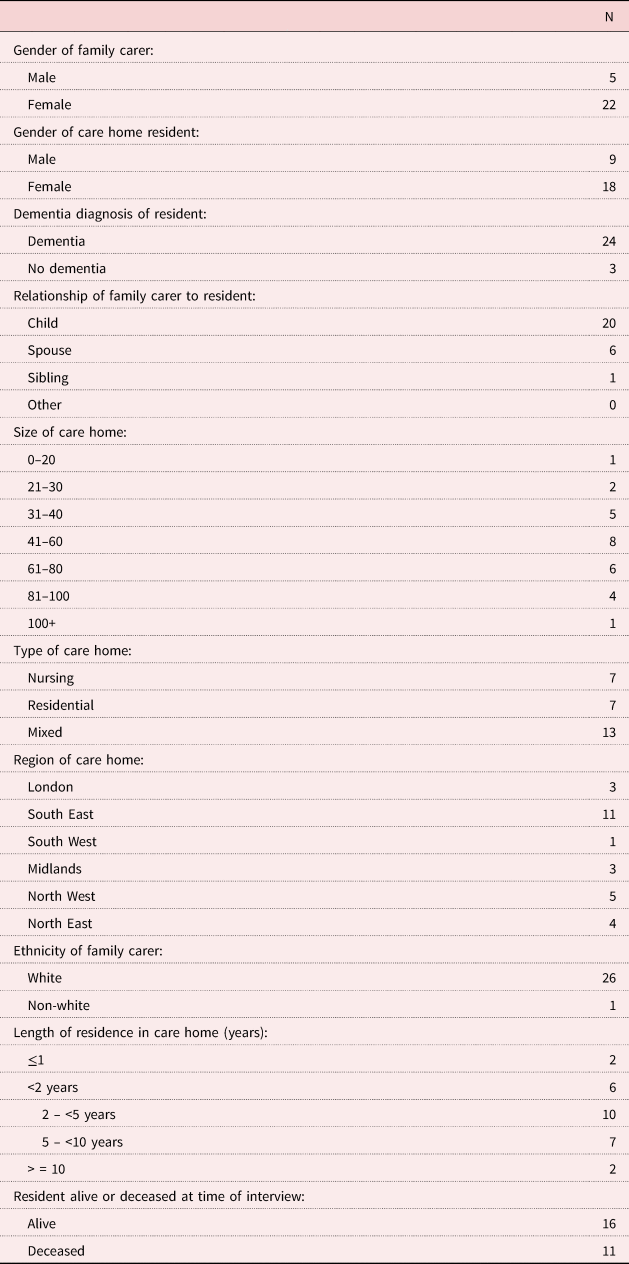

The achieved sample (see Table 1) reflected considerable diversity across many of the sampling criteria, including size, type and location of care home. However, despite targeted calls and outreach to relevant organisations, we were able to recruit only one non-White family carer and no LGBTQI+ participants. Most participants were female and children of residents, and most of the care home residents they cared for had dementia.

Table 1. Achieved sample

Note: N = 27.

Family carers identified a range of fundamental capabilities that they wanted their relative, and often other residents, to be able to maintain during the pandemic. These included:

• Good physical health, wellbeing and function.

• Emotional wellbeing.

• A sense of connection with family.

• Having material needs and wants met.

Family carers saw themselves and care home staff as having separate and over-lapping roles in supporting these capabilities. These are discussed in more depth and in context in the following sections. In summary, however, family carers’ contributions included emotional connection and being an important and constitutive part of their relative's life; relationships with staff were generally not considered a substitute for residents’ relationships with their own spouses, children and other close persons. Many family carers augmented the day-to-day care and support provided by staff, sometimes noting that, even outside the pandemic, care homes are constrained in the level of care they can provide by financial, regulatory, organisational and staffing pressures. Because of their relationship and personal knowledge of their relative, family carers also saw themselves as best placed to provide emotional reassurance to their relative, and help staff identify emotional and physical needs and develop tailored care strategies. They also commonly saw themselves as having an important role in monitoring care standards, promoting their relative's best interests and acting as their advocate. Family carers described a range of exemplary care from care home staff, and commonly recognised the challenging conditions in which they worked. However, they also often expressed wide-ranging concerns about whether their relative's fundamental capabilities were, or could be, sufficiently supported during the pandemic without their visits.

We identified four factors that were important for family carers in their role as care supporters for their relative during the pandemic. These were:

• Clarity, a sense of shared purpose, clear accountability and confidence in visiting restrictions.

• Family carers having access to regular, personalised updates about their relative using a range of digital communication tools.

• Allowing choice about visiting arrangements where possible, and ensuring visits are appropriate for residents with dementia.

• Feeling welcomed, included and enabled to resume in-person visits at the earliest opportunity.

We first discuss the capabilities that family carers wanted for their relative, focusing on how these were made more vulnerable by the pandemic and the associated visiting restrictions. We then discuss factors that influenced, positively or negatively, whether family carers were able to feel reassured that their relative's capabilities were, or could be, sufficiently supported.

Capabilities

Good physical health, wellbeing and function

Due to visiting restrictions, family carers had less opportunity to monitor their relative's physical wellbeing or become involved in day-to-day health-care decisions. They were also less able to assist with routinised, daily support. Nutrition was a common concern in dementia, and family carers who had previously done so were unable to bring in special food items, take their relative out to eat or support them at mealtimes. Some residents were thought to have lost weight as a result:

There weren't enough carers when everybody's in individual rooms to help feed them, so mum wasn't getting fed, and the food wasn't appetising. I used to take her out for lunch to get food down her which obviously I couldn't do. (Participant 1)

With exceptions, organised physical activities for residents had ceased or been reduced, limiting opportunities for exercise. Family carers also described adapted visits (e.g. behind Perspex barriers) that presented health and safety risks:

That was probably the most terrifying because someone brought Mum into the room and left. Mum stood up, wandered, tripped over the microphone wire. They very quickly, after that, someone came and stayed in the room. (Participant 2)

Family carers were also less able to monitor and address poor standards of physical care. When limited in-person visits were possible, family carers reported examples of finding their relative being left in bed or sat in a wheelchair for long periods, decline in food standards, poor grooming and hygiene, and residents not having their own clothes.

Emotional wellbeing

Where care homes provided good quality care and plentiful opportunities to socialise, residents with dementia were not necessarily distressed and some remained apparently unaware of the pandemic:

I didn't honestly see any difference in her at all, she was pretty much exactly the same as she was when she'd gone in. It was like the whole thing had never happened. (Participant 3)

However, other family carers reported that their relative experienced distress. The most discussed source of emotional distress for residents with dementia involved physically distanced visits (e.g. gardens, gazebos, window visits, Perspex screens) and visits involving masks and other PPE:

He [resident's spouse] was two metres behind the screen at one side and she [the resident] was two metres at the other and the staff just popped her in, left her and walked off, and she just cried the whole time. (Participant 4)

This was compounded if residents experienced perceptual difficulties, poor hearing and/or short-sightedness:

He [registered blind resident] wasn't allowed to touch me and I wasn't allowed to touch him. I shall probably cry now – he'd sometimes put his hand out to touch me and they'd pull, you know, the care assistant, not nastily, they'd just move it away. (Participant 5)

Others reported that their relatives were distressed, because of family separation, self-isolation following transfer into a care home or a hospital visit, or because of mental health or behavioural issues:

All I could offer her [wife with psychological and behavioural symptoms of dementia] was some form of empathy and sympathy and encouragement and support, and I didn't feel that the physical environment [during distanced visit] helped me do that in any way, shape or form. (Participant 6)

In these varied situations, family carers were especially concerned at being aware of, or witnessing, their relative's distress while, at the same time, being unable to offer them any direct emotional support and comfort.

A sense of connection with family

Family carers were often concerned about losing a sense of connection with their relative, their relative feeling abandoned or forgetting them, or the loss of time together, especially given many residents’ limited life expectancy. Some found separation from a spouse, in particular, hard to accept:

The care staff can go and see her, but I can't go and see her. Emotionally, it's not easy. It's a pining sort of thing because you're kept apart. (Participant 7)

However, some were less concerned about visiting regularly. These included those in situations where their relative with dementia seemed content:

There were still people there, you know, with the staff, making them busy and doing things. It didn't really matter so much who it was. (Participant 3)

It also included those with poor relationships and, for some, a reduced pattern of visits continued even when restrictions had eased. Others welcomed time-limited visits as they found these less pressured:

It kind of gives me that excuse not to stay for too long because she gets tired and finds it hard to speak. (Participant 8)

Nonetheless, family carers commonly described wanting to feel they were part of their relative's life, could protect them from harm and influence their life positively:

I still wanted to have an impact on [name's] life, you know, I made sure that he had plenty of nice clothes, he had treats, you know. We decorated his room and tried to make things nice, even though I'm sure it didn't have much impact upon him. (Participant 9)

For most, being with their relative at the end of life was especially important, to offer comfort but also as a fundamental relational value. Family carers commonly described supportive arrangements for end-of-life visiting:

I said, ‘I'm not going home now, I'm staying’, and she said, ‘You can't’, and I said, ‘I'm staying, and my daughter's staying’, and they accepted it. We had mattresses in his room and we stayed with him till he died, and the staff on the two days before he died were absolutely brilliant. (Participant 10)

However, they also described a lack of advance clarity about what visits would be permitted, who could attend, what was and was not allowed during a visit, and how their relative's end of life would be managed.

Having material needs and wants met

The capability of residents being able to have their material needs and wants met was not a significant theme but did feature in some family carer accounts. Some described taking food and personal items to the care home although, because they could not deliver the items to their relative directly, occasionally wondered if these had reached their relative. Sometimes their relative's clothes and possessions wore out without their realising, and purchasing and fitting new items was challenging:

It's a horrid feeling because you can't see the condition of their clothing, so to get a phone call to say, ‘can you try and get your mum new slippers because she's put a hole in the toe?’ because I wouldn't never let it get to that point. (Participant 11)

There were also examples of non-standard forms of spending to meet residents’ material needs. For example, family carers sometimes bought technology for the home (e.g. a tablet, telephone extension) using their own personal money, and in one case, care home staff had purchased toiletries for residents using their own personal money without seeking or expecting reimbursement from residents, families or the care home.

Other residents and families being able to have the same capabilities

While, exceptionally, family carers described supportive relationships with other families through the pandemic, generally they saw less of other residents and their families during this time. Nonetheless, family carers often expressed concern that other residents and families have similar capabilities to those they wished for themselves and their relative. For example, some said they avoided calling so staff could concentrate on providing care to other residents:

You knew they were under pressure and it's taking time away from looking after people to have to answer the phone and take the phone to mum. (Participant 12)

Family carers also sometimes expressed support for measures to protect other residents or sympathised with residents in more challenging situations.

Factors influencing whether family carers felt their relative's capabilities were, or could be, sufficiently supported

Clarity, a sense of shared purpose, clear accountability and confidence in visiting restrictions

Family carers were initially reassured by government guidance being followed and trusted that visiting restrictions were ‘for the best’. There was also wide acceptance of the need for ongoing precautions to limit transmission. However, over time, a lack of clarity and shared purpose, unclear accountability, and declining confidence in the effectiveness and proportionality of restrictions caused concern and often distress, and placed strain on relationships with care homes.

Occasionally, family carers described there being clear accountability, with their relative's care home distinguishing between national guidance and their own care home-specific response:

We were getting emails saying this is the latest government guidance, this is what we think about it, do we agree, do we not agree, you know, and why we're doing this. (Participant 13)

More commonly, however, family carers were uncertain about how much discretion care homes had, were confused by frequent changes, or described inconsistencies between care home policies and the national guidance or government announcements. There were also local inconsistencies. A family carer of a blind and deaf resident reported that local regulators advised that she should have special visiting arrangements, while the care home manager reportedly insisted, ‘no, it's nothing to do with them, it's what the government say. You can't see your dad any more than anybody else’. In other cases, care homes appeared internally inconsistent or unsupportive of their own rules:

Whatever carer told you was the rules, whoever you spoke to on the phone, none of them really knew, they were just guessing. (Participant 14)

[The care home] were happy I'd challenged it because they didn't agree with the policy themselves, saying it's the Health Authority. (Participant 1)

Family carers commonly questioned the prioritisation of infection control over other potential risks and harms, especially as the pandemic progressed:

Who decided that level of risk assessment, that COVID went above everything else? (Participant 2)

This could cause family carers concern about whether other aspects of their relative's wellbeing were being fully considered. For example, one family carer received a letter saying residents would no longer mingle and, given that most residents had dementia, she worried that her mother would be locked in her room. Some noted that many residents had very limited life expectancy, leading one respondent to ask, ‘“keep safe”, for what?’ Family carers also increasingly doubted whether restrictions on family visiting were effective at limiting transmission. Many thought risks of transmission from staff were under-estimated and insufficiently discussed:

It was all about the safety of the other residents, but all the carers were in Marks and Spencer's or wherever they went shopping, so you kind of thought, they haven't assessed the level of risk. (Participant 7)

Similarly, they thought risks from visitors were over-estimated, with some arguing that they personally presented a low risk or noting not all residents had regular visitors anyway. Commonly, policies were also increasingly thought disproportionate following the introduction of testing and vaccinations and as restrictions in the wider community eased:

It was ridiculous you know people were going to the cinema and theatres and everything and we still weren't able to just go and visit my mum. So, I think that was when we became less accepting of what was going on. (Participant 4)

Only in one case did a family carer feel that restrictions had possibly become too relaxed, with insufficient infection control measures in place within the home to ensure that she felt protected from catching COVID-19 while visiting.

Personalised and meaningful updates about their relative's wellbeing

Family carers were not always given regular updates about their relative, leaving them having to contact the care home. Some said, when they called, they were told only that their relative was ‘okay’, ‘fine’, ‘comfortable’ or ‘the same’, leaving them wondering, ‘what does that mean?’ Sometimes this was because staff answering the phone were not directly providing care to their relative or were agency staff:

When they really had the COVID epidemic in the home, that half of them died, there were carers who were agency, who didn't know her, but they were trying to tell me bits and pieces, which really they couldn't. (Participant 15)

Family carers particularly valued speaking with the staff who were directly providing care to their relative. One, for example, chatted using video-conferencing software to a staff member, with her mother in the background. She appreciated the personalised information and seeing her mother, apparently content, without the stress of trying to interact with her online. Another similarly commented that she thought speaking to someone caring for her relative would be preferable to the unhelpful and distressing virtual visits she had attempted:

I wished they would say, ‘Well, what we'll do is I'll phone you once a week. Forget trying to talk to Mum. I'll phone you, and just talk to you about how her week's been.’ (Participant 16)

Being able to see day-to-day life in the home was also especially welcomed. One family carer described a staff member walking around the care home looking for her mother while video conferencing on a tablet. This reproduced a sense of an in-person visit, giving her a wider view of the home:

You could see the progress down the corridor, and she was just sitting in her armchair having a cup of tea, and she seemed fine … then it would pan around and you could see one or two of the other residents, so you got a bit of background. (Participant 3)

Another accessed an online ‘Resident Gateway’ portal, with daily photographs and information about her relative. This worked well and limited her need to call the home:

I can log in every day and just see how she is and it's all her care records are on there, what she's done in the day, what she's eaten, her blood sugar levels, everything. That was really helpful during COVID. (Participant 8)

Family carers also described personalised updates about their relative's wellbeing being sent, sometimes informally, by individual care staff using, for example, text message or WhatsApp.

Flexibility and choice over visiting arrangements

Visiting arrangements were commonly undifferentiated, with approaches determined by guidance and policies at different points during the pandemic rather than individual needs. The needs of people with dementia were also thought not to have been well-considered. Some participants viewed having adapted or distanced visits as ‘better than nothing’. They valued seeing their relative and gaining visual reassurance about their wellbeing:

Mum looked quite well. I could see what she was wearing. You know, her hair had been washed. She looked lovely, just that, you know. (Participant 13)

However, as already discussed, residents with dementia sometimes found these visits distressing or disorientating, and occasionally they presented health and safety hazards. Others simply gained little value from them:

Before the pandemic, all I would do was sit and hold his hand, stroke his face and he would fall asleep, so, there was nothing we could talk about. (Participant 9)

Sometimes practical arrangements for visits were inadequate. This included technology failures such as poorly performing microphones. In another case, a visiting room was used for two visits simultaneously, separated by a thin screen, causing a resident with dementia to become confused about who was talking. Staff support for visits was not always available but could help residents with dementia engage with their family carer online and, for in-person visits, help keep the resident focused, encourage them back if they left or, if necessary, provide comfort:

He was really good at keeping her focused on the screen and we would end up having a sort of three-way conversation, and he would be prompting her so she got something out of it. (Participant 3)

Flexibilities around PPE use and physical distancing were wanted for residents who did not recognise them wearing a mask or who primarily communicated through touch:

For goodness’ sake, we had gloves. They can smother her in gel if that's what they need to do. Touch, sometimes it's all people have left. That should've been thought about. (Participant 14)

These were, however, sometimes allowed informally:

We're supposed to wear masks, but in his room, I'm allowed to take it off, but if the manager comes along, I put it back on. When I take the mask off, he recognises me sometimes. (Participant 5)

Family carers sometimes wanted more choice about where visits took place. Where they could directly access their relative's room (e.g. fire escape, garden entrance), they thought it better to meet there rather than in an uncomfortable visiting room used by other families. Sometimes they were not allowed to use the garden, even if preferred and thought safer, and at other times, only allowed in the garden, even though some residents preferred not, or refused, to go outside.

Others wanted flexibility regarding young visitors. For example, one family carer had a daughter with special needs who could not accompany her because she was slightly under the age limit. Appointment systems varied. Some had a ‘first come, first served’ approach and, in one home, there were no weekend appointments, making it difficult for working family carers to visit while, in other homes, staff ensured that family carers could book appointments to fit their circumstances. While family carers understood that some choices may not be possible, e.g. because staff needed to supervise or because of perceived equity, they wanted more personalised approaches:

I just wish they'd sort of looked at all their residents, like they do in a care plan, and said, ‘how do we, for this individual person’, not just a kind of banging out, ‘oh we've got this new app’. (Participant 16)

Rather than 50 emails, one phone call would have been, ‘let's talk about [resident's name], let's talk about what's best for her’, and there was a bit of that. (Participant 13)

Finally, some thought that, in larger homes, it could have been possible to group residents according to the level of precautions they and families preferred, reflecting the discretion that people in the wider community were able to exercise.

Feeling welcome and included by staff

Many family carers thought they should have the same access as staff. One care home initially discussed involving family carers as volunteers but did not take this forward. When the essential care-giver role was introduced, no family carer in our sample was informed and those who applied were often initially refused:

I couldn't understand the logic when they wouldn't allow me essential care-giver status because one of the things that was said, ‘if we give it to you, everybody will want it’. But that was the whole point. (Participant 14)

While many said they felt that care homes wanted to keep them from coming into the home, others said that they thought this was because care homes needed more support and resources to implement the role safely.

How communications were managed also influenced whether family carers felt welcome. For example, family carers sometimes described communications as ‘defensive’, ‘formal’, ‘legalistic’ and ‘corporate’:

All of the corporate stuff about how wonderful we are, our processes worked, it wasn't our fault, all that. I was like, ‘yeah, I don't really care, I want to know how my mum is’. (Participant 17)

Detailed information about restrictions and visiting arrangements was sometimes thought clear and informative, if voluminous. In other cases, family carers found communication about practical arrangements lacking or disorganised, and had to call to enquire about current rules. Some also thought there were more communications about increasing rather than easing restrictions, around which communication appeared more ad hoc:

I was a bit upset that there wasn't an announcement that we could visit. It was you only heard because I was keeping in contact with other relatives. (Participant 18)

Others felt staff viewed them negatively. One family carer described staff ‘eye-rolling’ at the mention of families. Another reported receiving an email warning families not to be verbally abusive or threatening, rather than beginning with the assumption that most family carers would think that unacceptable. Others felt they were seen as a nuisance if they advocated for their relative or raised issues of concern:

That generation, they don't like to make a fuss, so she won't press her alarm but she'll tell me. Then I feel like I'm a nuisance because I've got to go and tell the nurse. (Participant 8)

When family carers raised concerns, follow-up action was not always taken and in one case, a manager told a family carer that she and her relative could choose another home if she was unhappy. However, many said that care home staff responded constructively when issues were raised:

Nobody was every nasty with me or even short with me, you know they would try and speak to you about what you were concerned about. (Participant 9)

Some thought that staff preferred not having family carers around, perhaps because they were so busy, but others worried it could be so that relatives would not complain about declining care standards:

I think it got to the point where they enjoyed not having family members around noticing what they weren't doing. (Participant 1)

However, family carers commonly recognised that staff were working under pressure and sometimes commented that families’ expectations about what was possible were ‘not necessarily rational’.

There were also various examples of family carers feeling actively included. For example, some said that staff always contacted them if there was a problem or to discuss their relative's care, and felt welcomed back into the home as soon as it became possible to visit in person:

Obviously COVID has been an extreme example, but the relatives are always supported and included at all times. You know, when we couldn't be there in person we were still involved virtually and by speaking to the staff. (Participant 3)

In one case, a family carer described being unexpectedly invited to attend a local outdoor trip with her father. Another said that a staff member told her that it was ‘great seeing relatives come back in because it's a little bit of normality coming back’. Even where family carers experienced difficulties with the care home and had concerns about their relative's care, they sometimes formed good informal relationships with individual staff members and reciprocated through friendliness, shows of gratitude and gifts.

Discussion

This study examines family carers’ experiences of visiting restrictions in care homes in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adopting a relational autonomy lens, conceptualised using the capability approach, we aimed to identify how family carers perceived their relatives’ capabilities to have been impacted by visiting restrictions and how relational support for their relative's capabilities could be strengthened. Data were collected using in-depth interviews with 27 family carers in England whose relatives, predominantly with dementia, were living, and in some cases died, in care homes during the pandemic. Data were analysed thematically using NVivo software and methods informed by interpretive grounded theory.

The impacts of visiting restrictions on residents’ capabilities

During the COVID-19 pandemic, family carers’ concerns focused on their relative's fundamental capabilities: physical health, emotional wellbeing, connection with family and, to some degree, material needs. These correspond broadly to Nussbaum's ‘central capabilities’, which form the foundation for all other capabilities and include capabilities such as life, bodily health, emotion, affiliation and control over one's immediate environment (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2003). Occasionally, family carers felt confident that these capabilities were, or would be, fully supported despite restrictions. More commonly, however, they reported a range of capability failures and deprivations.

Family carers believed that residents’ ability to maintain their physical health was negatively affected by them not being able to monitor their relative's physical wellbeing, participate in day-to-day health decisions or provide usual support for nutrition and mobility. Some residents experienced physical decline, including loss of weight and function, potentially as a consequence. Falls risks were also thought to have increased because of changed routines and environments, and reduced supervision. Some participants also commented on declining standards of physical care covering hygiene, grooming and clothing.

The ability of residents (and family carers) to have emotional wellbeing was affected by family separation and by family carers not being able to offer in-person support and comfort to their relative. Emotional distress was most commonly discussed in the context of ‘adapted’ types of visit (e.g. screens, gazebos). These were frequently difficult or distressing for those with dementia, with insufficient apparent scope for care homes to adapt arrangements in response to these experiences (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023). Not all such visits, however, were distressing. Some family carers were relieved to see their relative, described ‘adapted visits’ as ‘better than nothing’ and valued being able to evaluate their relative's wellbeing first-hand.

The ability to feel connected to family is constitutive of autonomy since people value connectedness with significant others and not just ‘mere survival as independent autonomous persons’ (Voo et al., Reference Voo, Lederman and Kaur2020). Prolonged separation and loss of time together, especially with spouses and where life expectancy was limited, was consequently distressing for many. Family carers were also concerned about their relative feeling abandoned, with research showing care home residents already vulnerable to loneliness (Gardiner et al., Reference Gardiner, Laud, Heaton and Gott2020). Family separation, however, was notably less concerning for family carers with relatives with dementia living in care homes with adequate staffing, a strong ethos of person- and relationship-centred care, high levels of continuing within-home socialisation and consistent, albeit remote, family involvement in residents’ care (Keady et al., Reference Keady, Seddon and Woods2007). These positive experiences serve to highlight the importance of optimised relational support. End-of-life visits were also of fundamental relational importance. These were largely facilitated in caring and supportive ways, but commonly within a context of uncertainty about how end of life would be managed and what visits would be allowed, contrary to good palliative care principles (Kaasalainen et al., Reference Kaasalainen, McCleary, Vellani and Pereira2021; Sleeman et al., Reference Sleeman, Bradshaw, Ostler, Tunnard, Bone, Goodman, Barclay, Higginson, Ellis-Smith and Evans2022). Supportive arrangements also appeared to sometimes rely on the discretion of individual staff members rather than policy, potentially reflecting a lack of clarity in government guidance around what constituted, or was permissible in, end-of-life visits (Hanna et al., Reference Hanna, Cannon, Gabbay, Marlow, Mason, Rajagopal, Shenton, Tetlow and Giebel2022; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023).

Finally, material needs (e.g. renewing clothing) occasionally went unmet or were inappropriately paid for by families (e.g. technology) or staff (e.g. residents’ toiletries).

While there were positive experiences, our findings align broadly with earlier studies conducted in the UK, Netherlands, Italy and Canada, which identified family carers’ feelings of frustration and distress (Chirico et al., Reference Chirico, Pappadà, Giebel, Ottoboni, Valente, Gabbay and Chattat2023; Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Hanna, Cannon, Marlow, Tetlow, Mason, Shenton, Rajagopal and Gabbay2023) and negative impacts on trust between care homes and families (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Yee and Stamatopoulos2022, Reference Chu, Yee and Stamatopoulos2023). The importance of family involvement in long-term care settings, particularly in dementia, is widely recognised, both in research (Keady et al., Reference Keady, Seddon and Woods2007; Harding, Reference Harding2017; Hoek et al., Reference Hoek, Verbeek, Van Haastregt, De Vries, Backhaus and Hamers2018; Boumans et al., Reference Boumans, van Boekel, Verbiest, Baan and Luijkx2022; van der Weide et al., Reference van der Weide, Lovink, Luijkx and Gerritsen2023) and policy (Carers Trust, 2016; Care Quality Commission, 2022). It is notable, therefore, that our findings suggest the role of families in providing relational support for care home residents, particularly those with dementia, appears poorly considered, in government guidance and in care home policies and communications (Cousins et al., Reference Cousins, de Vries and Dening2021; Chu et al., Reference Chu, Yee and Stamatopoulos2023; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023).

Strengthening relational support for residents’ autonomy (capabilities)

Given the potential vulnerability of care home residents, ensuring adequate relational support for their autonomy, rights and wellbeing is a critical focus for policy. It is especially important in the context of a public health emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where autonomy and rights are widely restricted and usual forms of relational support for care home residents may be less available (Jeffrey, Reference Jeffrey2020). This is highlighted by our research, showing family carers with significant concerns for their relatives’ fundamental capabilities. However, translating concepts such as relational autonomy into practical strategies is challenging (Butchard and Kinderman, Reference Butchard and Kinderman2019). Our study, drawing upon the perspectives of family carers, uniquely identifies four factors for optimising relational support for care home residents’ autonomy, rights and wellbeing in the context of a public health crisis. These cover (a) ensuring clarity, a sense of shared purpose, clear accountability and confidence in visiting restrictions; (b) family carers having access to regular, personalised updates about their relative using a range of digital communication tools; (c) allowing choice about visiting arrangements where possible, and ensuring visits are appropriate for residents with dementia; and (d) ensuring that family carers feel welcomed, involved and enabled to resume in-person visits at the earliest opportunity. Each of these emphasises the importance of communication and co-operation between care homes and family carers in a context involving fewer regular face-to-face interactions. These are, consequently, likely to also be of relevance outside a public health emergency.

Ensuring clarity, a sense of shared purpose, clear accountability and confidence in visiting restrictions

Family carers were commonly unclear about how much discretion care homes had and were confused by frequent changes and apparent inconsistencies, e.g. between care home policies and government guidance or announcements, or advice from local regulators. Family carers sometimes also reported inconsistent information given by different staff in the same care home. These findings concerning clarity and accountability reflect those in earlier research with care home managers (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023). Family carers also described how care home communications tended to focus disproportionately on compliance with restrictions rather than on how their relative would be supported. This could cause concern and distress and place strain on family carers’ relationships with care homes (UK Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, 2021; Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, de Boer, Gabbay, Marlow, Stoop, Gerritsen and Verbeek2022).

As the pandemic progressed, family carers also increasingly considered the measures disproportionate and questioned their effectiveness, citing the cumulative negative effects on residents’ wellbeing, the introduction of testing and vaccination, and the easing of restrictions in the wider community, including for care home staff. Public health considerations can justify limiting rights, including adapting how care is provided in the context of over-stretched services, but such restrictions should be time-limited and proportionate (Hepple et al., Reference Hepple, Smith, Brownsword, Calman, Harding, Harper, Harries, Hill, Holm, Kaletsky, Knight, Krebs, Lipton, Murdoch, Parry, Perry, Plant and Rose2007; Spadaro, Reference Spadaro2020). Lack of resources alone is insufficient defence for limiting rights. Determining whether restrictions are proportionate requires a clear understanding of the likely impacts of restrictions and the ethical dilemmas involved, with an onus on government to communicate clearly how these considerations will be balanced (Phua, Reference Phua2013; Spadaro, Reference Spadaro2020; Nihlén Fahlquist, Reference Nihlén Fahlquist2021). Those whose rights are most affected should also be consulted (Chetty et al., Reference Chetty, Dalrymple and Simmons2012). Our research suggests that these deliberations were lacking or insufficiently communicated (UK Parliament Joint Committee on Human Rights, 2021; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023). When developing and implementing infection control measures, the impact on residents and families should always be explicitly considered and care homes and representatives of families and care home residents should be directly involved in national or other assessments of their feasibility and acceptability (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023). Importantly, Nihlén Fahlquist (Reference Nihlén Fahlquist2021) argues that better conceptualisation of how relational autonomy can be supported in the specific context of infectious disease, where there are competing ethical demands and complex interdependencies, will also be helpful in informing discussions about proportionate measures.

Family carers having access to regular, personalised updates about their relative using a range of digital communication tools

We found that access for family carers to regular and personalised updates about their relative was commonly lacking. This could leave family carers anxious and having to call the care home for sometimes limited information. While pressures on staff time are likely to have contributed to this, responding reactively to individual phone calls did not appear more efficient and family carers were worried about drawing staff away from providing direct care to residents. Video-conferencing with relatives with dementia was particularly challenging and sometimes distressing for family carers, particularly when residents were left unattended, e.g. with a propped-up iPad, by staff. Our data, however, also included good practice examples. These included family carers video-conferencing with staff directly caring for their relatives, video-conferencing calls providing a wider view of life in the care home, and relative's online portals providing on-demand up-to-date information, including photographs and care notes, about individual residents.Footnote 2 Research should explore the challenges and opportunities for implementing measures such as these more routinely, as well as to prepare for future public health emergencies. The use of digital care records and associated family portals, in particular, is likely to be supported by the national introduction of shared care records (NHS England, 2022; Brown, Reference Brown2023) and development of a national minimum dataset for care homes (Towers et al., Reference Towers, Gordon, Wolters, Allan, Rand, Webster, Crellin, Brine, De Corte, Akdur, Irvine, Burton, Hanratty, Killett, Meyer, Jones and Goodman2023).

Allowing choice about visiting arrangements where possible, and ensuring visits are appropriate for residents with dementia

Visiting arrangements were largely undifferentiated, rather than personalised and reflective of individual needs, most notably the specific needs of people with dementia. This may have reflected inflexibility in national guidance and from local regulators, a lack of focus in national guidance on the needs of residents with dementia and staffing pressures (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023). Research for understanding opportunities and how challenges can be best managed would be helpful. Digital tools such as appointment booking systems may have an important role to play.

Ensuring that family carers feel welcomed, involved and enabled to resume in-person visits at the earliest opportunity

Earlier research found that some care home managers saw benefit in involving volunteers and essential care-givers at an early stage but did not necessarily feel sufficiently supported to do so (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023). The UK Parliament's Joint Committee on Human Rights (2021) also questioned whether such roles should have been enabled earlier, given pressures on staff and the risk anyway of staff transmission. Evidence from our study strongly supports this view as well as evolving proposals to give health and care service users the right to a care supporter at all times.Footnote 3 However, understanding the support that care homes need to manage care supporters and volunteers safely in the context of a public health emergency will be important, particularly in light of the significant pressures we know that care home managers experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023).Footnote 4

The tone of care home communications was also important to families. This includes avoiding overly legalistic and defensive communications, as well as giving greater emphasis to how family carers could remain involved, remotely or in person, rather than focusing primarily or exclusively on how access would be restricted. Other research suggests that defensive communications probably reflected stresses experienced as a result of limitations in national guidance and local regulation, staff pressures and pre-existing structural weaknesses in social care systems (Curry et al., Reference Curry, Oung, Hemmings, Comas-Herrera and Byrd2023; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Lorenz-Dant, Stubbs, Harrison-Denning, Mostaghim and Casson2023). Notably, the involvement of family carers was often facilitated through the discretionary efforts of individual care staff. A relational autonomy approach also draws attention to the challenges involved in current models of congregate living for older people and raises questions about the quality of care in the absence of family scrutiny for people living with dementia (Wikström and Emilsson, Reference Wikström and Emilsson2014; Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Cyhlarova, Comas-Herrera and Lorenz-Dant2021).

Strengths and limitations

This study's strengths include in-depth, conceptually informed analysis with data drawn from interviews with family carers with a wide range of different characteristics and whose relatives resided in homes of different sizes and types across England. However, we achieved limited ethnic minority and no LGBTQI+ representation. Targeted research with these groups into experiences of care home infection control measures is merited. A further limitation is that the perspectives of residents or staff are not represented in our findings. Interviews took place some months after restrictions were significantly relaxed in early 2022. This may have affected recall, but interviews were flexibly conducted to focus on issues of most salience, and therefore likely to be most memorable, to participants. Speaking to family carers after restrictions were relaxed also minimised potential ethical issues associated with conducting research while significant restrictions were in place and gave family carers the opportunity to better reflect on their experiences and, for some, manage experiences of subsequent bereavement.

Conclusion

In a public health emergency, care home residents may be more vulnerable to the primary threat, in this case, the COVID-19 virus. In England, managing this vulnerability was prioritised in government guidance and actions. However, public health measures to manage transmission and protect vital services, such as visiting restrictions, may also impact residents’ other capabilities, including the ability to sustain physical health, emotional wellbeing and connection with significant others. The concept of relational autonomy draws attention to how these capabilities depend significantly on relational support, from care staff, families and others. Supporting the network of relationships around the resident can therefore help limit capability deprivations. We identified four specific measures to enhance relational autonomy in the context of a public health emergency: (a) ensuring clarity, a sense of shared purpose, clear accountability and confidence in visiting restrictions; (b) family carers having access to regular, personalised updates about their relative using a range of digital communication tools; (c) allowing choice about visiting arrangements where possible, and ensuring visits are appropriate for residents with dementia; and (d) ensuring that family carers feel welcomed, involved and enabled to resume in-person visits at the earliest opportunity. Limitations to residents’ usual rights should be proportionate and take account of their greater vulnerability to capability failures and deprivations. Infection control measures should be developed and implemented in consultation with care homes, families and residents, and the competing ethical considerations involved should be clearly communicated and regularly reviewed. Workforce and digital readiness should be prioritised.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to all of the family carers who gave their time to participate in an interview. We are also hugely grateful to our advisors, chaired by Sir David Behan (Chair, Health Education England) and comprising Paul Callaghan (Healthwatch England), Karen Harrison Dening (Dementia UK), Cathrina Moore (Dementia Resource Community), Sarah Mitchell (University of Leeds), Sara Livadeas (Social Care Work, previously The Freemantle Trust), Morgan Griffiths-David (Alzheimer's Society), Jenni Burton (University of Glasgow), Daniel Casson and his colleagues at Care England, and Margaret Dangoor (Involvement Manager, London School of Economics and Political Science). We are also exceptionally grateful to our experts-by-experience group of family carers who each had a relative living in a care home during the pandemic (Jane Payne, Susan Ogden, Sumita Biswas and Julia Fountain). Special thanks are also due to our transcription team and to Anji Mehta for project support.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme (reference NIHR202482). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was provided by the HRA Social Research Ethics Committee (reference 21/LO/0564).

Appendix: Topic guide

This topic guide provides an overview of key topic areas that the Visit-id study aims to investigate in interviews with family carers of people living in residential care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is designed to be used flexibly. Interviews will cover the key topic areas outlined in this guide but the depth in which the different areas will be discussed, the order in which they are covered, and the range of follow-up questions will vary between interviews.

The aim of interviews is to understand family members’ views and experiences of care home visiting policies with an emphasis on relevant ethical values, including support for residents’ wellbeing and capabilities and concepts of autonomy and relational autonomy, and exploring trade-offs and prioritisation of different values and concerns.

Thank participant for sharing their signed consent form and check whether they have any further questions about the study.

Ask permission to record the conversation.

Recap briefly that participation is voluntary and they can choose not to answer particular questions or withdraw at any time, that the information they provide will be treated confidentially and that no one other than the research team will listen to or see their data, and that they will not be identified in any report.

Introduction

• Can you tell me about your relative living/who lived in a care home (i.e. relationship to you, health condition, etc.)?

• Can you tell me about the care home your relative lives/lived in (e.g. type of home – nursing, residential, dementia specialist)?

• How long has your relative lived/did your relative live in the care home?

• How comfortable in the care home was your relative prior to the pandemic?

• What was your relationship with the care home like prior to the pandemic?

• What was the frequency of visiting/type of visit prior to the pandemic (e.g. giving care, keeping company, etc.) (e.g. distance travelled to visit, constraints, typical times, frequency, intensity, activities undertaken and meaning e.g. how far physical visiting viewed as an essential part of a commitment, as a family, to care for one another)

• Were you aware of a visiting policy at that time (written or otherwise, or even unspoken or informal rules)? What was it, as far you were aware?

Communication of policies

• During the pandemic, how were you informed about the care home's visiting policy (or policies)? What was good and bad about how this was done?

• How were you kept updated about changes to the visiting policy? What was good and bad about how this was done?

• Were you provided with, or did you see, a written visiting policy, or was it communicated verbally or in some other way?

• Who [position] communicated with you? Was it the same person throughout the pandemic or different people?

• With regard to communication of the visiting policy, what do you think has worked well and less well?

• Do you know who you would (have) contact(ed) about the visiting policy if you (had) wanted to ask questions or discuss it?

• Did you seek information, advice or support from anywhere?

Reflections on visiting policy

• Did you find the visiting policy (or policies) during the pandemic easy to understand, fair and proportionate? Please say why.

• Did families feel that the correct aspects of their relative's care were prioritised? How, if at all, did this change over time?

• As far as you are aware, was a blanket approach taken or were individual circumstances taken into consideration in the visiting policy?

• Were there any other points that you think the care home should have thought about when writing its visiting policy?

• How did you stay in touch with your relative, if at all? Were you given alternatives to in-person visits to keep in touch with your relative? Were these effective? How were you informed about these?

Factors that influenced the visiting policy

• What factors do you think influenced the care home's decisions about their visiting policy?

• Are you aware of any constraints or limitations that the care home has experienced with regard to their decisions about their visiting policy?

• How, if at all, do you think the care home could have improved its visiting policy?

• What trade-offs did they perceive there to be? How did their relative's care home make these trade-offs? What did they think of this?

Consideration of views of residents and families in developing the visiting policy

• Were the thoughts and views of residents, you and other families considered when the care home wrote its visiting policy (or policies), as far as you are aware?

• If yes, how was this done? What went well and less well? If no, how would you have liked to be involved in the development of the policy?

• How, if at all, do you think residents and their families helped to influence/shape the visiting policy?

Implementing the policy

• Do you think that the care home has implemented their visiting policy consistently, appropriately and fairly?

• As part of implementing the visiting policy, were you offered testing? How quickly was this enabled? Did/does your vaccination status play a role in visiting?

• How many people are currently visiting your relative? What is the frequency of visits?

Your relative's views

• Was, as far as you know, your relative consulted about the visiting policy?

• From conversations you may have had with your relative, what were/are their views on the care home's visiting policy, to the degree that you know (e.g. did they think it was easy to understand, fair and proportionate, and why)?

• Did they, as far as you are aware, think the care home implemented the visiting policy consistently, appropriately and fairly?

Closing

• What would you say your relationship with the care home and with the staff is like now?

• What do you think should happen to visiting if the UK infection situation deteriorates further and/or in event of another pandemic infection?

• If you could give advice to other families facing a similar situation in future, what would that be?

Thank participant for sharing their views and experiences.