INTRODUCTION

It has long been argued that one of tort law’s key functions is to deter potential tortfeasors from acting without due care. Yet, tort law’s ability to deter presents a challenge. If the incentives are too strong, individuals might avoid taking actions, even when such actions will not result in a wrong, as they will be over-deterred. In contrast, if the incentives are too weak, individuals might act without taking due care, thus increasing the likelihood that their actions will result in wrongdoing, as they will be under-deterred. A prime example of this challenge arises in the context of combatant activities. Legislatures, courts, and scholars have asserted that if combatants are not afforded complete immunity from tort liability for losses they inflict during warfare, then they will refrain from engaging in combat or from doing all that they can to achieve their military goals (Koohi v. United States 1992, 1330–31; Jamal Kasam Bani Uda v. Israel 2002, 5; Estate of Hardan v. Israel 2003, 14; Saleh v. Titan Corp. 2009, 18; Jacob Reference Jacob2003, 129–30). A “combatant activities exception” to tort liability is, therefore, justified, as it prevents combatants and states from being over-deterred.Footnote 1 In this article, I challenge these accounts and justifications, using a novel empirical examination of tort liability’s ability to deter state actors from engaging in warfare. The findings indicate that impositions of liability under-deterred state actors from conducting hostilities, yet prompted a regulatory side effect: the expansion of the combatant activities exception to halt what some actors viewed as the continuation of warfare through civilian means.

The combatant activities exception can be found in many common law jurisdictions,Footnote 2 and it stands against a general trend that began in the mid-twentieth century of eliminating states’ and public officials’ immunities (Bradley and Bell 1991, 15; Harlow Reference Harlow2004, 23; Kerr, Olivo, and Kurtz Reference Kerr, Olivo and Kurtz2014, 75). The fear of over-deterring combatants is based on the notion that public officials and public bodies might bear the risks of their activities, but they generally do not gain the benefits of their activities in the same way that private individuals do. This incentive scheme raises the concern that public officials and public bodies might be more prone to risk-averse behavior, causing them to act overcautiously and to fall short of fulfilling their public functions properly (Schuck Reference Schuck1983, 68; Fairgrieve Reference Fairgrieve, Fairgrieve, Mads and Bell2002, 483; Surma Reference Surma, Fairgrieve and Andenas2002, 390). However, thus far, no empirical evidence has been offered in support of the argument that tort liability will over-deter public officials, and a theoretical analysis of deterrence points to the opposite conclusion.

In this article, I empirically examine the assertion that tort liability for losses that are inflicted during warfare will result in over-deterrence. Through this examination, I offer substantial insights about the implications of imposing tort liability on public officials and public bodies for military actions. I demonstrate that the common instrumental justification for the combatant activities exception does not align with the theoretical underpinnings of deterrence, and that there are indications that, in this context, tort liability will not result in over-deterrence. I also offer an innovative legal history analysis of the causes of and motivations for the development of Israel’s immunity from tort liability for losses it inflicts during warfare, relying on data from 1951 to 2021. This analysis indicates that the motivations of state actors developed, at least in part, in response to and alongside changes in the character and intensity of the conflict between Israel and Palestine. As military forces were being used to perform policing and counterterrorism activities in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, state actors began viewing the Palestinian civilian population as an enemy and tort claims as a means of continuing warfare through civil litigation. Israel’s immunity from liability was expanded not because of a fear of deterring combatants from engaging in battle, but to support this form of “combat.”

In doing so, this study sheds new light on two factors that are currently misconceptualized: the identity of relevant state actors and their incentives for action or inaction in relation to engagement in battle. Courts and scholars’ theoretical concern with over-deterrence focuses either on the effects of an imposition of tort liability on the state, as if it were an autonomous actor, or on its combatants. Furthermore, the theoretical concern with over-deterrence seems to assume that the risks associated with liability are deemed to be at least as important as the security interests of the state and its agents. Yet, theorizing deterrence in this way disregards the fact that states can only act through their public officials. It also overlooks the possibility that public officials, who are not combatants but can influence whether and how to engage in combat, could be over-deterred. Additionally, the assumption that the risk of tort liability is as important as security risks seems to be counterintuitive. Rather, security interests are likely to take precedence over other liability-related considerations, and so the liability-related considerations should have little to no effect on the decision to engage in combatant activities. In this sense, this study not only creates a dataset of tort liability’s effects on state actors in relation to combatant activities but also adds to the theoretical discourse on the role and scope of tort liability’s deterrent effects on public actors.

To achieve these objectives, I offer an exploratory research example using both quantitative and qualitative methods and focusing on Israel as a test case. My analysis is composed of an original empirical survey of 320 Israeli combatants; thirteen in-depth, semi-structured interviews with members of the Knesset (the Parliament of Israel), high-ranking officers, legal advisors to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and the Ministry of Defense (MoD), and state and district attorneys;Footnote 3 an evaluation of the explanatory notes and protocols regarding the legislative amendments to the exception by the Israeli legislature; and additional secondary sources in relation to state actors’ incentives to engage in combat or expand the combatant activities exception.

Israel provides a rich legislative history regarding the combatant activities exception that cannot be found in other jurisdictions. In Canada and the United States, for example, the rationale for enacting the exception is nonexistent, and while in Australia and the United Kingdom the exception is a creation of the common law, the courts have not provided a fully fleshed out justification for it (Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates 1953, 3332; Shaw Savill & Albion Co. v. Commonwealth 1940, 361–63; Johnson v. United States 1948, 769; Mulcahy v. Minister of Defence 1996, 748–49; Ibrahim v. Titan Corp. 2005, 18; Saleh v. Titan Corp. 2009, 120). In contrast, Israel offers an abundance of materials. When Israel was established in 1948, it barred all tort claims against the state and its officials for two reasons. First, it feared that its public officials were not experienced enough and were therefore likely to bring about a significant number of injuries (Protocol of the 185 Session of the Second Knesset 1952, 2112). Second, it assumed that individuals were likely to sue the state for the actions of its inexperienced officials, which would result in mass debt that the state could not repay (2112). However, in 1952 it enacted the Civil Wrongs (Liability of the State) Act, which both enables the state to be held tortiously liable and immunizes it against any tortious liability for losses related to combatant activities. Unlike other jurisdictions, the Israeli legislature amended the scope of the exception three times, providing some insight in relation to the motives for the exception through the Bills’ explanatory notes and protocols from the Israeli Parliament’s Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee in which the amendments were discussed.

Furthermore, Israeli courts interpreted the applicability, scope, and rationale of the exception in over 290 casesFootnote 4 —more than the Australian, Canadian, UK, and US analyses of the topic combined—and have continuously broadened the interpretation of its scope. Plaintiffs in these cases are civilians, and on rare occasions corporations, that sustained a loss due to the operations of Israel’s security forces, and the defendant is the state. The vast majority of plaintiffs are nonnational Palestinians, although Israeli and other foreign nationals have also occasionally brought tort claims in this context. Causes of action are mostly concerned with negligence and trespass to person and property that arise from a range of activities, either within Israel or in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. These activities include, inter alia, counterterrorism warfare, operation of checkpoints and policing activities by the military, and even traffic accidents involving combatants on duty.

The article proceeds as follows. In the second section, I examine whether an imposition of tort liability will result in over-deterrence from a theoretical standpoint. I identify three relevant groups of state actors who participate in the decision-making process regarding whether and how to engage in combat and who could be deterred from an imposition of tortious liability: politicians, combatants, and government attorneys. I conclude that over-deterrence of these actors seems improbable, as the necessary elements for deterrence (ability to choose course of action, information on risks and costs, and internalization of liability costs) are absent or nonoperative in relation to combat. In the third section, I test this conclusion using quantitative and qualitative methods, assessing state actors’ deterrence from hypothetical impositions of liability, and the legal history of the establishment and expansion of the combatant activities exception in Israel. An analysis of the collected data suggests that an imposition of liability for losses that are inflicted during battle under-deters the relevant state actors from engaging in belligerent activities. Yet, tort litigation and liability has a secondary side effect on politicians and government attorneys, as it prompted them to initiate and adopt legal amendments that greatly restrict potential plaintiffs’ access to effective remedies. The fourth section concludes by suggesting that the beliefs that ground the justifications of the combatant activities exception should be revisited. The findings of this study indicate that the minimization of tort liability was driven primarily by a desire to limit courts’ ability to hold that the state inflicted a wrongful loss, rather than a fear of over-deterring combatants or a concern that tort suits would prove too costly for the state to bear. Additionally, while tort liability and litigation did not deter state actors from engaging in wrongful combatant activities, they did have an important regulatory side effect in that tort liability and litigation seem to have prompted state actors to expand the scope of the immunity from liability. Given these findings, it is difficult to defend the combatant activities exception through the concept of over-deterrence.

OVER-DETERRENCE OF COMBATANT ACTIVITIES: A THEORETICAL ASSESSMENT

The existence of the combatant activities exception is often justified on the grounds that liability would over-deter states and combatants, causing them either to refrain from engaging in belligerent activities altogether or to avoid using all the means at their disposal.Footnote 5 For instance, in the Koohi case, which to date provides the most exhaustive analysis of the exception’s rationales given by a court, Judge Reinhardt held that

Tort law is based in part on the theory that the prospect of liability makes the actor more careful … Congress certainly did not want our military personnel to exercise great caution at a time when bold and imaginative measures might be necessary to overcome enemy forces; nor did it want our soldiers, sailors, or airmen to be concerned about the possibility of tort liability when making life or death decisions in the midst of combat. (Koohi v. United States, 1330–31)Footnote 6

Judge Reinhardt’s argument illustrates an additional point that is evident in both judicial opinions and scholarship on this topic: they often consider the deterring effects of tort liability either on the state as a single entity or on combatants as the only relevant state actors. Yet, the state is comprised of various groups of actors, each of which might have different considerations and incentives. In the context of belligerent activities, there are three relevant groups of state actors who play an active part in the decision on whether and how to engage in battle: politicians, government attorneys, and combatants.Footnote 7 Both politicians and combatants are decision-making actors in relation to engagement in or refraining from battle. In this sense, an imposition of liability, either directly on them or vicariously on the state, might, in theory, deter them from engaging in certain activities. In addition, government attorneys are relevant actors both because they advise politicians and combatants about the possible legal ramifications of their conduct and because they can be an integral part of the legislative processes that determine who is liable in tort.Footnote 8 The key question is, therefore, whether these three groups of actors could be over-deterred from engaging in combatant activities for which tortious liability could be imposed.

To this end, it is essential to understand what I refer to as “the spectrum of deterrence.” Deterrence is commonly understood as the potential of tort liability to influence an actor’s decision whether to engage in a potentially injurious activity or how to conduct it considering the pecuniary costs and benefits that are associated with the various choices she has. Under-deterrence is at one end of the spectrum, and it occurs when tort liability does not incentivize individuals to take due care. Over-deterrence is at the other end of the spectrum, and it occurs when tort liability provides incentives so strong that individuals might avoid taking action even when it will not result in a wrong for which they will be held liable. Somewhere in between lies the optimal level of deterrence, which prompts individuals to act with an adequate degree of care.Footnote 9

This understanding of deterrence is premised on three assumptions. First, that individuals have a choice whether to participate in or refrain from an activity and whether to take precautions in relation to that activity (Jacob Reference Jacob2003, 127). Otherwise, tort liability is not likely to influence their behavior to a significant extent, as they must act, or refrain from acting, in the particular way that is prescribed to them. Second, it is assumed that individuals have accurate information about the costs and benefits that are associated with action and inaction and an opportunity to engage in a rational analysis of this information.Footnote 10 Partial information and lack of expertise in analyzing its meaning result in erroneous determinations, which in turn could provide misguided ex ante incentives to individuals (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2003, 552). Third, it is also assumed that an imposition of liability will, generally, change individuals’ balance of reasons, thus incentivizing them to act more carefully, and that without this incentive individuals will not act with due care (Sugerman Reference Sugerman1989, 12–18). In the context of belligerent activities, none these preconditions seem to be met in relation to the three relevant actors during warfare.

Take the fact that the ability to choose freely between courses of action is somewhat limited in combat, for example. When politicians are in the position of directing the military’s activities, they are free to choose whether the military will engage in combat. Indeed, they can opt for a completely pacifistic approach to any threat their country and constituents face. Yet, it is equally possible that politicians will prefer to incur the financial costs that arise from engaging in battle over the political or financial costs of inaction, even if the former are greater than the latter.Footnote 11 Politicians’ discretion, in this regard, is wide. That said, politicians might not have the knowledge or willingness to choose the exact course of action and so might defer on this issue to high-ranking combatants.

Combatants’ discretion is significantly more limited. Once politicians have ordered them to engage in a belligerent activity or refrain from it, they have little choice over the matter. High-ranking combatants might have the ability to choose how and when to engage in the belligerent activity, but this potential choice is more limited, by and large, when it comes to lower-ranking combatants. Most commands are given to lower-ranking combatants with a high degree of specificity and a low degree of discretion. Furthermore, when faced with risk to themselves or others, combatants might feel obligated to act in self-defense (Benbenisty, Ben-Shalom, and Ronel Reference Benbenisty, Ben-Shalom and Ronel2010, 42), lack the time to make cost-benefit considerations, or be forced to act inadvertently.Footnote 12 In either case, it is hard to see how liability could have any deterrent effect as freedom of choice is very limited (Englard Reference Englard1993, 43–44; Jacob Reference Jacob2003, 128). Additionally, while they can refuse to participate in belligerent activities, and perhaps to enlist altogether, in doing so they are accepting the possibility that they could be held criminally or administratively liable.

Likewise, government attorneys’ discretion is limited. They can advise politicians and combatants on the legal nature and implications that certain acts or omissions might have. In doing so, they cannot offer legal advice that is beyond the scope of their role, and they are generally not in a position to order that a combatant activity be conducted or not. Rather, they advise the individuals who will decide whether to engage in combatant activities.

As for information about the various costs and benefits of combatant activities, it seems that all three groups of actors are unlikely to have a full and accurate account. War has been aptly described as “the realm of uncertainty” (Clausewitz 1832, 101). Any analysis could not be made with certainty, or even a high degree of plausibility, and it is unclear whether the lack of information will result in over- or under-deterrence. The degree of deterrence that an imposition of liability would add in this calculation hinges on the level of risk-aversiveness of each group of actors, the weight they assign to tort liability considerations, and their ability to freely choose their course of action. Furthermore, while politicians, government attorneys and high-ranking combatants might have access to more information regarding the various costs and benefits of each particular activity, lower-ranking combatants are less likely to have such information. Lower-ranking combatants might be informed about what costs and benefits their mission generally entails once it has been decided, but they will not be informed of various alternatives to their mission.

Lastly, all three groups of actors are unlikely to bear any of the costs personally for three main reasons. First, potential plaintiffs are discouraged from filing claims due to high litigation costs, low potential compensation, and procedural hurdles (Bachar Reference Bachar2017, 849–51). With fewer plaintiffs standing on their rights, neither individual state agents nor the state fully internalizes the costs of the losses the state inflicts (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2002, 1071). Second, in those instances where plaintiffs do decide to sue, it is the state and not any particular agent of it that is sued. This could be because the identity of the combatant who actually inflicted the loss is unknown, because the state has deep pockets from which plaintiffs can recover their costs (Jacob Reference Jacob1992, 455; Crootof Reference Crootof2016, 1390), or because of a legal hurdle to holding a public official liable.Footnote 13 Third, even if individual agents were sued, the state could not only be held directly or vicariously liable, but also might pay the cost of compensation in its agents’ stead.Footnote 14 The combination of these three factors results in little to no internalization of costs by individual state agents from any of the three relevant groups. Moreover, the state is likely to be indifferent to the costs of tort liability, as such liability is unlikely to have a significant budgetary consequence.

Consequently, it seems that politicians, combatants, and government attorneys are unlikely to be deterred by a potential imposition of tort liability. While politicians have relatively more freedom to choose their course of action, combatants and government attorneys are more restricted in what they can and cannot do, especially while belligerent activities are being conducted. Information for all groups is partial, and lower-ranking combatants are generally likely to have the least amount of information regarding the costs and benefits that are associated with various forms of action and inaction available to them. Individuals from all groups of actors will not internalize the costs of losses they impose, and the state’s budget will not be affected in any significant way by an imposition of tort liability. Given that none of the groups of state actors meets all three preconditions, it is hard to maintain that tort liability in this context will have an over-deterring effect;Footnote 15 deterrence in this context seems theoretically unlikely.

TESTING THE THEORY

The purpose of this empirical study is to test the theoretical conclusion I reached above, namely that politicians, combatants, and government attorneys are not likely to be over-deterred by the notion of an imposition of tortious liability for losses that are inflicted during battle. This hypothesis is based on two assumptions. First, many actors do not possess information about the potential risk that is associated with an imposition of tort liability, and so the idea of liability could not deter them. Second, even those actors who do have the required information to potentially be deterred would nevertheless be risk-neutral in relation to tort liability, either because liability considerations would have little to no weight in comparison to security considerations, or because those actors would not have a choice regarding whether or how to engage in belligerent activities.

That said, it is important to note that as an exploratory study, this article’s findings are suggestive of the possible deterrence effects of tort law on state actors in relation to combatant activities. However, the study was not designed to prove causality in the local Israeli test case or universally, and other factors might also influence state actors’ decision to engage in or refrain from belligerent activities.Footnote 16

Data and Methods

Survey

I conducted an online survey aimed at assessing whether combatants could be deterred from engaging in belligerent activities due to tort litigation and liability. The survey was made available on May 7, 2018, to individuals who identified as Israeli combatants on active or reserve duty, and was open until July 2, 2018.Footnote 17 The survey had three parts, and the questions were primarily closed-ended. There were two versions of the survey to control for question order bias. In one version, respondents were first presented with three vignettes, then in the second part they were asked additional questions, and in the third part demographic information was solicited. In the second version, the order of the first and second parts was reversed, and the order of the questions in the second part was altered.

I distributed the survey through social media, sharing a link to the survey through Facebook, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and Telegram, in my public profile, and in groups dedicated to mutual assistance or military service. The link was subsequently shared by followers and other users. I also directly contacted individuals on Instagram whom I identified as combatants through their tags.Footnote 18 I chose this method of distribution because of the lack of a viable alternative for this specific study. There is no survey service that can slice the population according to the type of military service, and collaborating with the IDF was ruled out as the results of such collaboration would not be allowed to be made public.

I solicited demographic information in the third part of the survey. The sample includes 320 individuals in total, of which some chose to disclose their demographic information. One hundred ninety-two identified as male and fourteen identified as female, all between the ages of eighteen and forty-five. Eighty-eight respondents identified as serving in active duty, while 114 identified as serving in reserve duty. Ranks varied from Private to Major. Eighty-six identified as single, sixty identified as being in a relationship, and fifty-eight identified as having children. One hundred and six identified as having participated in combatant activities in the past, and ninety-seven indicated that they had not. Finally, seventy-one individuals identified as left-wing (response on scale of 0–100 ≤ 50) and 112 as right-wing (response on scale of 0–100 ≥ 51). The demographics indicate that the survey was distributed to a diverse audience along some axes, such as age, active or reserve service, and political view, thus reducing the risk of sample bias. Still, some risks remain as the demographic indicators are self-reported and there is a lack of diversity along some of the axes. Given these limitations, as well as the aim of this article to offer an initial, yet rich and insightful, exploration of combatants’ attitudes toward tort liability, it is important to note that I am not claiming that the sample is representative or that the results uncover an objective “truth.”

The three vignettes presented the respondents with hypothetical scenarios in which they had to decide whether to engage in potentially tortious behavior with a backdrop of particular legal rules or conditions. This method was chosen as the existing immunity from liability makes it difficult to get an accurate assessment of the levels of deterrence that liability could generate without relying on an analysis of hypothetical scenarios. In each of the three vignettes respondents were informed that if civilians were hurt or killed while engaging in a combatant activity, an Israeli court would declare that they would be compensated. The first vignette did not specify the amount of compensation, the second vignette specified the amount to be 500 ILS, and the third vignette specified the amount to be 5 million ILS (equivalent to roughly 150 and 1.5 million USD, respectively). Furthermore, the respondents were informed that the risk faced from the target of the combatant activity is low. They were then asked to indicate how likely they would be to attempt to avoid engaging in the combatant activity in four alternatives:

1) The court would instruct the state to compensate its own civilians

2) The court would instruct the state to compensate enemy civilians

3) The court would instruct them to compensate fellow civilians

4) The court would instruct them to compensate enemy civilians

The likelihood was measured on a sliding scale, anchored at the low end (0) by “I will not attempt to avoid engaging in the combatant activity at all,” and at the high end (100) by “I will do everything in my power to avoid engaging in the combatant activity.”

In the second part of the survey, respondents were asked seven short questions. Two questions were aimed at gauging the degree to which combatants believe they have the ability to choose their course of action freely: one where they were instructed during a briefing to strike a target, and the other where such instruction was given in the theater of operations. They were asked to choose between three options:

1. They have the ability to choose whether to engage in a combatant activity or refrain from doing so.

2. They do what their commanders order them to do.

3. They do what other combatants do.

Respondents were also asked to indicate whether the statement that the state can be held liable where civilians are injured during belligerent activities is true or false, and whether such a statement is true or false in regard to the possibility that they would be held liable under such circumstances. Lastly, respondents were asked to indicate, using a five-point Likert scale (anchored at the low end (1) by “I completely disagree with the statement,” and at the high end (5) by “I completely agree with the statement”), if they would prefer to avoid participating in a combatant activity if:

1. They would have to testify about the activity in an Israeli court;

2. Other people would claim that their actions were immoral or illegal; or

3. Participating in the combatant activity would result in their inability to travel to various countries.

Semi-Structured Interviews and Secondary Sources

I conducted interviews with thirteen individuals in total: high-ranking officers, politicians, legal counsels, and district and state attorneys. The interviews were conducted in Hebrew in January and February 2019, both online and in person, lasting between thirty minutes and two hours. All but two interviewees consented for the interviews to be recorded and transcribed, and for detailed notes to be taken. Six interviewees asked to remain anonymous. These include members of the legal community who are involved in tort litigation against the MoD, which is small and close-knit. Hence, I will refer to district and state attorneys, as well as Ministry of Justice legal advisors, as “government attorneys” (GA) to maintain confidentiality. In addition, interviewees who are high-ranking officers in the IDF and wished to remain anonymous will be referred to by rank and “IDF.” All other interviewees have agreed to be identified. I transcribed the interviews manually and translated them into English.

To identify possible relevant interviewees, I began by examining the legislative history of the combatant activities exception. There are sixteen protocols in total that are relevant for the legislative process of the combatant activities exception, from its initial enactment to its most recent amendment. However, in only eleven of these protocols is there meaningful discussion that could be used to evaluate how actors perceive the notion of an imposition of tort liability for combatant activities. Ten of the relevant protocols are from the Knesset Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee, and one is from the Knesset Plenum. Also, there are explanatory notes attached to the four relevant Bills introducing the exception or its amendments. A total of 171 individuals took part in the deliberations, of which fifty were politicians, fifteen were military personnel, forty-two were government attorneys, and sixty-four had other affiliations. I then reviewed these results to locate key stakeholders through the office they held and the number of times their names appeared in the secondary sources. The resulting list included twenty-four politicians, eleven military personnel, and seventeen government attorneys. Interviews were secured first by contacting individuals that belonged to the three relevant groups of state actors when their contact information was publicly available from Google and the Israel Bar Lawyers Database (N = 25). The response rate was 24 percent. Subsequent interviews with key stakeholders, who have expertise and intimate knowledge on the factors that influence the relevant state actors in deciding whether and how to engage in warfare or on the amendments to the combatant activities exception, were secured through a snowball process.

It should be noted that interviewees’ accounts are susceptible to a variety of factors, such as selective recollection of past events, a concern with confidentiality, self-interest, and self-aggrandization. My analysis proceeded with these factors in mind, contrasting and comparing the accounts of my various interviewees with each other, as well as with recorded evidence of past events in the secondary sources I examined. In this sense, I do not perceive my interviewees’ accounts as representations of truth per se, nor are they treated as a source from which an objective representation of reality or intention can be derived. Rather, attention is given to the language, perspectives, and narratives that arise from their accounts of the law and its development (Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998, 29; Geva Reference Geva2019, 707).

Furthermore, I assessed additional secondary sources and relied on the findings of an empirical study of 1,486 combatants that was conducted by the IDF in 2009 after operation “Cast Lead” and was aimed at identifying what factors motivate soldiers to engage in combat (Benbenisty, Ben-Shalom, and Ronel Reference Benbenisty, Ben-Shalom and Ronel2010, 42). 869 combatants were in active duty, 569 were in reserve duty, and twenty-one did not specify the type of their service.

Using qualitative content analysis, I coded and analyzed the interviews’ transcripts and secondary sources, taking an inductive and contextual interpretive approach. This process enabled me to identify three themes in the motivations of the three relevant groups of actors for enacting and amending the combatant activities exception and for engaging in warfare. First, protecting security interests initially prompted politicians to enact the exception to avoid deterring combatants from doing all that needs to be done to achieve military aims. However, tort law–related considerations were entirely abandoned in decision-making processes soon thereafter. The second theme was promoting legal coherence and capabilities, which views the conditions of warfare as intrinsically incompatible with the underlying character of tort law. The third motivation was entrenching a political stand that the enemy population should not have access to remedies that indicate that Israel acted wrongfully.

Security Interests Are a Cardinal Consideration

When Israel was established in 1948, the state enjoyed blanket immunity from tortious liability for its actions, following an Ordinance from the British Mandate that remained in force. However, in 1951 deliberations regarding the abolishment of this blanket immunity regime began. These deliberations provide some insights into politicians’ initial motivations for enacting the combatant activities exception. One such motivation was the fear that the potential for tort liability for losses inflicted during battle would over-deter combatants from doing all that needs to be done to attain military goals. For instance, Member of the Knesset (MK) Jacob Shapira stated:

The State’s security interests necessitate that during belligerent activities combatants’ hands shall not be tied by potential compensation that will be required, but that their thoughts would be solely focused on those actions that are essential for the protection of the state. (Protocol 49, 1952)

Similarly, MK Ami Assaf stated that:

If the definition of combatant activity will have nuances it can lead to a limitless burden … In this matter we cannot be too meticulous, as due to my conscientious deliberations the military’s necessary freedom of operation could be harmed. (Protocol 49, 1952)

It is therefore no surprise that when the Bill which abolished Israel’s blanket tort immunity passed in 1952, it included a combatant activities exception. Section 5 of the Civil Wrongs (Liability of the State) Act stated that Israel is not “liable in tort for a combatant activity committed by the Israel Defense Forces.” However, apart from this mention of tort liability as a possible deterrent to warfare during the deliberations that resulted in the 1952 Act, no such consideration was expressed in any other secondary source or interview.

In fact, the concern for security interests seems to outweigh considerations of tort liability in relation to decisions on whether and how to engage in belligerent activities. Many interviewees emphasized that greater value is placed on achieving military goals and eliminating security risks than on financial considerations, both generally and in relation to potential tort liability in particular. For instance, Colonel Prof. Gabi Siboni, who served as a fighter, commander, and the chief of staff of the Golani Brigade, stated:

Considerations of compensation do not influence the decision to go on a mission. But maybe that is too strong of a statement. On the political level the need to compensate is accounted for. We do not take over the Gaza Strip because that will cost a lot of money. But that is not accounted for on the operational level. (Interview with Colonel Gabi Siboni, February 2019)

Similarly, MK Deputy Commissioner David Tsur, who was a member of the Knesset, Head of Israel’s Counter-Terrorism Unit, Head of Israel Border Police (a body that is composed of both police and military forces and operates in the occupied Palestinian territory), and participated in numerous cabinet deliberations in which police and military operations were discussed, commented:

In Cabinet meetings the security consideration is always very important … and it is a decisive factor … [Damage to] infrastructure and other things of the sort are not considered as much when fighting terrorism as [these types] of losses are restorable … The main value that is being contemplated is human life, and the lives of the combatants and civilians … THE consideration is neutralizing the threat … the financial consideration is less concerning at the operational level. (Interview with MK Deputy Commissioner David Tsur, February 2019)

Even more explicitly, when asked whether politicians consider the costs of tort liability when they determine whether to order an engagement in combat, MK Major General IDF2 replied that “in my time it was not a consideration. There are many heavy considerations, and this is not one of them!”Footnote 19 (Interview with MK Major General IDF2, January 2019). Likewise, Major General IDF3 stated: “No one thinks in these terms in the military, and rightly so” (Interview with Major General IDF3, January 2019).

Put differently, when state actors were concerned about the possibility of an imposition of tort liability, they thought about liability as a security risk, hindering combatants from properly engaging in warfare. However, tort liability no longer seems to be a concern for state actors in this sense, nor does it appear to be a factor that is accounted for when deciding whether and how to conduct belligerent activities.

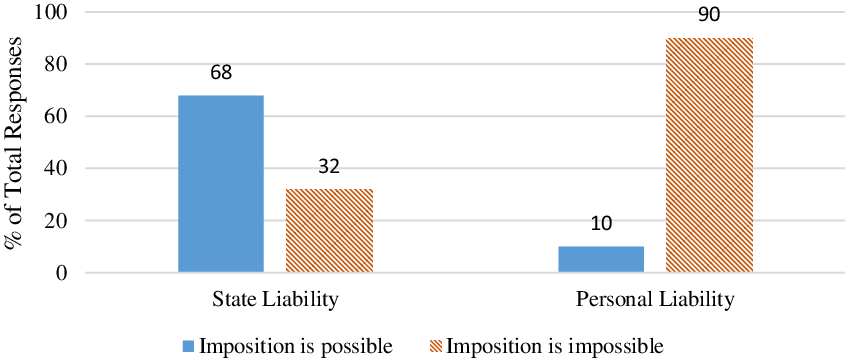

In fact, financial considerations seem to play little to no part in these decisions, and combatants appear to have little knowledge about potential tort liability risks that can be imposed on them or the state due to their conduct. Accurate knowledge of the possibility of incurring costs due to tort liability would mean that combatants believe that neither the state nor combatants can be held liable. Footnote 20 Yet, the results of the survey I conducted indicate that most combatants’ knowledge of potential tort liability is not entirely accurate (see Figure 1). Sixty-eight percent of combatants held the erroneous belief that the state might be held liable, and 10 percent of combatants incorrectly believed that they might be liable. These findings support the assertion made by government attorney GA2, who noted that “nonlawyers do not know the case law. It is not their job. Only in exceptional cases, like Elor Azaria [a combatant who committed an extra-judicial killing of a neutralized terrorist], [do] officers know court rulings” (Interview with GA2, February 2019).

Figure 1. Combatants’ Estimation of the Possibility to Impose Tort Liability. Note: N = 277.

This is not to say that financial considerations have no influence whatsoever. The state’s “deep pockets” simply mean that these considerations can always be accounted for and that their potential impact can be circumvented. Consequently, it seems that there will never be a situation in which the military will not be able to engage in belligerent activities due to an imposition of tort liability. Brigadier General Dr. Sasson Hadad, who served as the Financial Advisor to the IDF Chief of Staff and was Head of the Budget Division of the Ministry of Defense, shed light on this very point:

Our goal as financial advisors is to have the IDF units conduct themselves in an optimal fashion … There was never a case that a unit was incapacitated by liability … The economic approach is aimed at assisting, not paralyzing the operational level. (Interview with Brigadier General Sasson Hadad, February 2019)

Advocate Ahaz Ben Ari, who served as the Chief Legal Advisor to the MoD, Assistant Military Advocate General on International Law, and the Legal Advisor to the Gaza Strip and West Bank, voiced a similar position:

In the MoD, every year in preparation for the fiscal year, a survey is made for [the] accounting [department] of all of the pending cases and the financial risk they entail so we can put the required funds aside … There is no situation in which there will be a ruling against us and accounting will say “but we don’t have a way of paying it” because there will always, somehow, be a way of paying it … I don’t remember an instance in which I told the military “don’t do this or that because it already costed us once” … The budgetary issue should not raise any concerns. The budget line that is set aside for tort cases is acting like autopilot … If a survey says that this year is going to be very difficult with enormous sums, we think where we’ll bring the funds from in advance so that there wouldn’t be a problem later. (Interview with Advocate Ahaz Ben Ari, February 2019)

The costs of tort liability, therefore, seem to be an integral part of the costs of engaging in military operations. Tort liability is not an unexpected expenditure, nor is it an impediment to the state’s actions. In this sense, some of the force of an imposition of tort liability as an incentive to act more carefully is diluted, as pecuniary costs do not require the state or its actors to review their actions for fear of inability to conduct similar activities in the future. Nor is any particular imposition of liability an extraordinary occurrence that requires attention. Rather, tort liability is considered part of the ordinary operations.

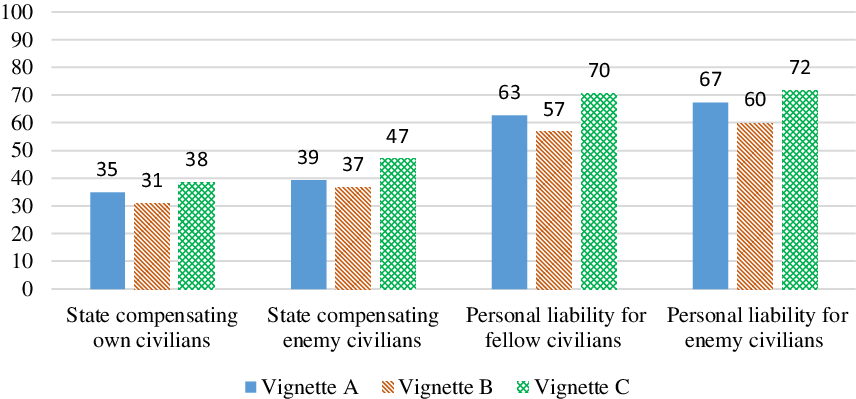

At this stage, it could be argued that these findings mostly reflect the current legal reality, in which both the state and its combatants are immune from liability. To assess whether the fears politicians expressed in 1952 of tort liability deterring combatants from engaging in warfare could play a role in practice, I presented survey participants with three hypothetical scenarios. As is illustrated in Figure 2, combatants’ level of deterrence varied according to the different hypothetical factual scenarios presented to them. When the state was said to be held liable for its own civilians, combatants’ reported level of deterrence was less than 40 percent. However, when the state was said to be liable for enemy civilians, combatants’ reported level of deterrence was less than 48 percent. In contrast, when liability was said to be borne by the combatants themselves, reported deterrence level was less than 72 percent whether liability was to their fellow civilians or to enemy civilians.

Figure 2. Average Level of Deterrence in the Three Vignettes. Note: NA = 287; NB = 233; NC = 217. Level of deterrence measured on a scale of 0–100.

At first glance, these results seem puzzling and counterintuitive. The theoretical analysis of deterrence suggests that combatants should be entirely indifferent to an imposition of liability on the state, as they do not internalize its costs. The theoretical analysis also suggests that combatants should be entirely deterred when liability could be imposed on them. Yet, the survey responses did not align with this analysis. Instead, respondents were somewhat deterred by an imposition of liability on the state and somewhat more deterred when liability could be imposed on them.

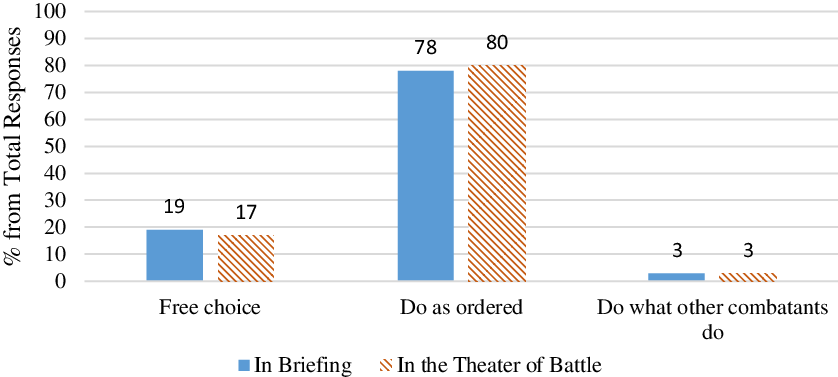

This puzzling result is, perhaps, clarified when two factors are considered. First is the degree of care for and identification with the state that combatants have. I will return to this point later in my analysis. Second is combatants’ ability to choose whether and how to engage in belligerent activities. In the survey, most respondents replied that they do not believe they are free to choose their course of action. As indicated in Figure 3, they either do what their commanders order them to do or they follow what their fellow combatants are doing. Only 19 percent of combatants indicated that they have freedom of choice whether to engage in or refrain from a combatant activity during a pre-operation briefing, and in the battlefield this number was reduced to 17 percent.

Figure 3. Freedom of Choice before and during Battle. Note: N = 277.

These results are supported by an analysis of the interviews I conducted. For example, Colonel Prof. Siboni explains: “In the military there is a command. There is no choice whether to execute … Assuming the command is legal there are no subsequent degrees of freedom. At the end of the day a command must be performed” (Interview with Colonel Gabi Siboni, February 2019). MK Deputy Commissioner Tsur offers a more nuanced account:

On the strategic level there is complete freedom in the Cabinet. The political ranks decide on the “what,” but on the tactical level … the degree to which the political ranks weigh in depends on the people … The tactical ranks decide on the “how” … Lower-ranking combatants have the ability to weigh in [on the “how”] in certain cases, depending on the type of the unit and whether their input is relevant. During combatant activities there is freedom to act within set guidelines. (Interview with MK Deputy Commissioner David Tsur, February 2019)

Lacking the ability to choose whether and how to engage in belligerent activities means that combatants’ personal considerations regarding tort liability play little role in how they will behave on the battlefield. The hypothetical presented to combatants asked them to indicate their level of deterrence in relation to each scenario on a sliding scale, anchored at the high end by “I will do everything in my power to avoid engaging in the combatant activity.” It may very well be that in the context of a hierarchal command structure, lack of choice means that even though combatants might be deterred from engaging in belligerent activities in theory, they do not have the power to avoid participating in them. Alternatively, it may be that on the balance of reasons, the level of deterrence from tort liability is not enough to incentivize combatants to act in a particular way or to refrain from acting altogether.

While tort liability seems to have little to no impact on decisions regarding whether and how to engage in warfare, the laws of war seem to be a relevant factor that is accounted for by state actors in this context. These laws prescribe which instances of use of force are legitimate and which are prohibited. Any command that violates the laws of war is illegal, and its execution should be refused. Every soldier receives basic training and guidance on the laws of war, and military lawyers advise commanders on the legality of combatant activities. MK Deputy Commissioner Tsur stated:

The State Attorney can say that something doesn’t work with the rules of international humanitarian law and so we don’t go ahead with a combatant activity … compliance with international law is the most important thing in this regard … There are legal advisors in almost all operational decisions … but they inform on how to do things that will “pass” legally, and they rarely hinder them. (Interview with MK Deputy Commissioner David Tsur, February 2019)

These observations align with findings that indicate that from the second Palestinian uprising (Intifada) in the early 2000s, military attorneys began viewing their role as facilitators of use of armed force rather than technicians of the laws of war or impediments to abuse of force (Geva Reference Geva2019, 708–16). As one senior official in the International Law Department of the Military Advocate General Corps stated: “Our goal is not to tie down the military, but to give it the tools to win in a way that is legal” (Blau and Feldman Reference Blau and Yotam2009). This point was also made by Colonel Pnina Sharvit-Baruch, former head of the International Law Department: “I am there to find legal ways to achieve the goals of the army… I am not there only to say what they can’t do. I am also there to say what they can do and how to do what they want to do in a legal way. This does not mean that I will tell them how to do something unlawful” (Craig Reference Craig2013, 185).

This shift in perspective coincided with a change in the way military lawyers understood the character of the functions the military was carrying out in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. They no longer thought about these activities as policing, but as actual combat that is short of full war (Geva Reference Geva2019, 715–16). Additionally, such factors as knowledge of the law, battlefield experience, and cultural background can influence the way in which the laws of war are understood, interpreted, and applied (Statman et al. Reference Statman, Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Mandel, Skerker and De Wijze2020, 450–51).

That said, the ability of government attorneys to influence whether and how combatant activities are pursued is somewhat limited. They can inform politicians and combatants about the degree to which particular belligerent activities would adhere to or breach international humanitarian law and the possible tort liability that might follow. Yet, government attorneys do not have the power to order that a particular combatant activity be pursued or stayed, and tort liability is not a factor that is presented to politicians and combatants when contemplating these matters.

We can see that the laws of war are a consideration taken into account by the relevant state actors, but that security interests influence the way in which they are interpreted and applied. Furthermore, tort liability was considered a factor that might influence the decision on whether and how to engage in combat only briefly in the history of the State of Israel and is no longer viewed as a relevant factor in this context. As such, security interests seem to have greater weight than other considerations that were mentioned in the interviews and secondary sources.

Legal Coherence and Viability

The 1952 iteration of the combatant activities exception simply stated that Israel is not “liable in tort for a combatant activity committed by the Israel Defense Forces.” This definition of the exception did not specify what amounts to a “combatant activity,” and consequently two approaches emerged in courts’ rulings: one interpreting the exception narrowly and the other interpreting it broadly.

According to the narrow approach, a combatant activity is one that is only conducted during warfare and that bears “familiar signs of combat, or … is one that is ordinarily performed in the midst of war” (Mifal Takhanot Hatraktorim Ltd. v. Hayat 1960, 1613). Similarly, in the 1986 Supreme Court case of Levi, Justice Shamgar held that only “actual combatant activities in their narrow and simple sense … are the ones to which the language of section 5 relates to” (Levi v. Israel 1986, 479). In another key case, the Jerusalem Magistrate Court held that one of the characteristics of a combatant activity is that it is rare and abnormal. Hence, actions in which a military force encounters violent protesters, which became routine during the First Intifada from 1987 to 1993, should not be understood as combatant activities but rather as policing activities (Abu Jabar v. Israel 1994, 19).

In contrast, the broad interpretation applied the exception to negligent activities even when there was no objective and immediate risk to combatants (Atallah v. Israel 1997, 554), and most significantly to policing activities in the Occupied Territories—deeming them combatant activities (Abu Shamisa v. Judea and Sameriya Military Commander 1994, 9). It is this latter aspect that was the key point on which the two interpretive approaches disagreed.

At the end of the 1990s, government attorneys began working on legislative amendments to expand the scope of the exception. The main purpose of Amendment 4 was to include policing activities in the Occupied Territories under the definition of “combatant activities” (Draft Bill 2645 for the Treatment of Claims against the Security Forces 1997; Protocol 405 2001).

However, these attempts did not bear fruit until the first in-depth analysis of the combatant activities exception, and its applicability in situations involving policing activities, by the Supreme Court of Israel in the 2002 Bani Uda case.Footnote 21 In this case, Justice Barak held that ordinary tort law is not suited to deal with the special risks involved in warfare (Jamal Kasam Bani Uda v. Israel 2002, 7).Footnote 22 Adopting the narrow approach, Justice Barak held that determining the applicability of the exception requires examining the specific injurious action, rather than the overall operations, bringing under the exception’s scope only actual belligerent activities in their simple and narrow sense.Footnote 23

The legislature was quick to embrace Justice Barak’s reasoning to push the amendment of the Act forward, successfully passing it only five months after the Bani Uda decision was issued. Yet, while Justice Barak’s rationale of the inapplicability of tort liability to warfare was adopted, the narrow approach to the exception was forsaken in favor of a broad approach, including more activities that are not strictly “combatant” as falling under the combatant activities exception. Since then, government attorneys initiated two additional amendments—Amendment 7 in 2005 and Amendment 8 in 2012—with a similar aim of expanding the exception. These amendments extended immunity for counterterrorism activities in circumstances that would fall outside what would be deemed “combatant activities” according to the Bani Uda precedent.

All amendments seem to have been prompted by the fact that the state was dealing with thousands of tort cases against it due to the operations of its security forces in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank following the first and second Palestinian uprisings. One government attorney said during an interview I conducted that “until 2013 there were thousands of open cases, and today there are a few dozens a year—if any. Dealing with these cases was very difficult … The ability to locate evidence and witnesses was extremely problematic” (Interview with GA1, February 2019).Footnote 24 Another noted that “there was a flood of hundreds and thousands of cases a year, and that was a part of the incentive to expand the combatant activities [exception]” (Interview with GA2, February 2019). A third stated that

What led to the amendments—the crazy flooding [of cases] and the disengagement [from the Gaza Strip] … Before [the amendments], every operation … resulted in a flood of lawsuits … We’re talking about a lot of cases, a lot of state attorneys, a lot of meetings, a lot of procedures, for not a lot of compensation. It is a lot of noise … that has a burdening effect that jams the system. (Interview with GA3, February 2019)

Yet, it was not simply the “noise” these tort cases were producing that spurred government attorneys into action. Rather, it was also the fact that they were losing cases. The culprit was identified in the Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee deliberations regarding the various amendments of the Act as evidentiary difficulties government attorneys faced when they argued that the exception should be applied in courts. Ascertaining whether the plaintiff was hurt by Israeli forces, and the extent of the injuries, was a challenging task given that, by and large, the plaintiffs reside in hostile territories (Protocol 66 2009). Furthermore, even when information regarding the nature of the operation was obtainable, the government attorneys still maintained that there was an evidentiary difficulty as this information was often confidential. In these situations, the state faced one of two scenarios. Either it had to expose confidential information or it had to settle in order to keep the information out of the public eye. District Attorney Irit Kalman describes this very dilemma:

A taxi was driving towards a roadblock with a suicide terrorist who carried a bomb. Intelligence was received regarding the taxi and the imminent terror attack … Without the use of targeted killing on the taxi the terror attack would have been executed. The taxi owner filed a claim … We came to the courts with affidavits from Brigadier Generals with all the information we could divulge … The court wanted to know who we got the information from, maybe it is wrong, maybe we were misled … In this case we were not misled but we cannot bring the evidence to court. (Protocol 489 2005)

Government attorneys’ problem with the evidentiary difficulties they faced in this context was more than merely frustration at lacking all the resources they needed to properly defend their position. Rather, they believed that by expanding the scope of the exception, and hence reducing or eliminating Israel’s tort liability for losses its security forces inflict, they were codifying a principle. Advocate Tamar Kalhoora, the representative of the Counseling and Legislation Department of the Ministry of Justice,Footnote 25 stated that “the purpose of this Bill is … to ground the idea that in war or armed conflict … every side needs to shoulder its own losses” (Protocol 81 2009; Protocol 502 2005). Likewise, government attorney GA2 said that:

The choice to call it the combatant activities exception—in my view it is not an exception … Violent conflicts or actual combat activities … don’t have a solution in the realm of tort cases because the situation is less under control for all the parties involved—the heat of battle and all that. All of the relationships we are used to talking about between wrongdoer and injured individual, and all the elements of negligence … they probably don’t exist. (Interview with GA2, February 2019)

Advocate Ahaz Ben Ari also noted in this context that government attorneys were simply trying to adapt the exception to the changing nature of warfare:

We expanded the definition of combatant activity to include counterterrorism activities … so that courts will have no doubts on this matter, because sometimes there was uncertainty regarding whether an action should be classified as “policing” or “combat.” In this sense, the state has total immunity. (Interview with Advocate Ahaz Ben Ari, February 2019)

When asked why it was the government attorneys who initiated the amendments, rather than combatants or politicians, interviewees replied that it was due to the fact that the government attorneys have the accumulated knowledge that is required to identify the difficulties that they believe require legislative reforms. As advocate Ben Ari described it: “the legal departments of government offices become an information gathering hub, that allows them to see all sorts of phenomena that occur through tort cases” (Interview with Advocate Ahaz Ben Ari, February 2019).

Yet, it is important to note that interviewees have indicated that while every case is tracked, there is no formal institutional mechanism of review through which the results of each case are studied. In government attorney GA1’s words: “the system is not built to review cases, and there is a big workload that doesn’t allow such processes to occur” (Interview with GA1, February 2019). Rather, there are informal social information networks, which can be broadly classified into three categories. First, there is a Tort Law Forum, in which representatives from the district and state attorneys’ offices (and sometimes legal counsels from ministries as well) gather every few months to discuss cases that the state is a party to and broader issues arising from them (Interview with GA1, February 2019; Interview with GA2, February 2019; Interview with GA3, February 2019). Second, there are state-wide and district-specific email chains for the state and district attorneys to report on, and ask questions regarding, their cases (Interview with GA2, February 2019). Third, knowledge is transmitted through what government attorney GA2 referred to as “war stories,” but could also be aptly described as hallway chatter (Interview with GA2, February 2019).

Limiting “the Enemy’s” Access to Court

The efforts to amend the combatant activities exception so that it would better reflect what government attorneys believed to be a more accurate reality of contemporary warfare and tort law were not motivated merely by a concern with theoretical purity and coherence. Nor were the amendments driven solely by the procedural difficulties the state faced when defending itself from tort claims. Rather, the identity of the individuals bringing tort claims and their perceived motives for doing so played a key role.

Between 1988 and 2014, Israel paid approximately 305 million ILS (equivalent to roughly 94 million USD) in compensation for losses inflicted through its security forces on the Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, either as the result of courts holding the state liable or due to settlement agreements (Lev Reference Lev2015). For some, the fact that these payments were made justified expanding the exception. It seems that many of the relevant state actors began to perceive potential plaintiffs as enemies and asserted that as such they should not benefit from Israel in any way. They did not care that the state might incur costs. Rather, they cared that state funds might reach those they believed to be its foes, as Minister of Justice Meir Shitrit argued in one of the Committee’s meetings regarding Amendment 4:

The Bill that was tabled is meant to prevent false claims against Israel. There is almost no country in the world that pays compensation during armed conflicts, or even opens the door to those people who might be injured in such a conflict to file a claim against it … the 260 million ILS that were paid were deducted from the Ministry of Defense’s budget … The purpose is to prevent the state from paying those who tried to kill its combatants. (Protocol 405 2001)

In a later session, he was even more explicit:

There is no country in the world, only a foolish country, that provides its enemies with the option of suing it and getting compensation. We are the only foolish country that allows such a thing. (Protocol 493 2002)

MK Dov Hanin, who participated in the deliberations regarding the amendments, argued that discussions about the amendments should not be understood as being about who should bear the financial costs of warfare from an objective economic perspective. Rather, according to Hanin, these discussions were about grounding a political standpoint that is rooted in the dynamics of the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine:

The perception [of those who supported the amendment to the exception] is political. They don’t want a situation in which Palestinians can vindicate their rights generally … The financial story there had no real meaning. It is not the type of financial deliberations that take place in the Knesset … You have to be from another planet to think that there were financial arguments here … This story didn’t arise because someone wanted to cut a certain line in the budget. No one looked at the budget and said “Hey, we have a problem here, let’s save Israel some money.” What bothered them more was the possibility that an Israeli court would say the state acted wrongly. They didn’t want that option. (Interview with MK Dov Hanin, February 2019)

MK Hanin’s view is supported by the attitudes that combatants expressed toward non-Israelis’ tort claims during the Committee’s deliberations. These combatants believed that Palestinian civilians were bringing tort claims against Israel for the losses they sustained as a tactic to weaken Israel. Put differently, tort claims were perceived as a continuation of warfare through civilian means, with plaintiffs as enemy combatants and tort claims as the weapon. For example, Lieutenant Colonel Mosheh Fisher maintained that:

Now we see their intentions. They say: let’s use the civilian population to strike … This is a very generous Jewish offer in our view to turn the other cheek, let them strike us economically as well, that hundreds of millions of ILS will not go to our poor. (Protocol 502 2005)

Likewise, Colonel Yilon Farhi stated:

In recent years, we are encountering a growing phenomenon of Palestinian claims. When I asked myself why this is happening two possibilities come to mind. One, we might be getting more barbaric, and I have to say that … this does not add up … Today’s Israeli society … is very moral … The other option is that somebody is using a legal loophole as a weapon against us … My personal estimation is that the Palestinians, encouraged by the lawyers who earn a living from them, take advantage of our morality as a weapon against us. (Protocol 511 2005)

This perception of Palestinians’ tort claims as part of warfare is also shared by some government attorneys as is evident from similar views that were voiced in the deliberations of the Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee and by some of my interviewees. For instance, government attorney GA3 said that “you don’t want outside forces to dictate the national priorities and budget, and in this case it was hostile outside forces who don’t have Israel’s best interest at heart ” (Interview with GA3, February 2019). Likewise, Advocate Kalhoora stated that:

We are not asking: the state is poor, it cannot deal with these cases, help, save us money, and so on … The result of the inability to deal with these claims in court is that the state of Israel will lose these cases, and will have to bear the costs of the other side to the conflict. (Protocol 489 2005)

In a study conducted by Gilat Bachar, a government attorney described the expansion of the combatant activities exception as follows:

Our determination in the war against these cases paid off … The insight was that if we would be determined and fight with full force—without paying anything—at some point the other side will realize that it doesn’t pay off to bring these cases. (2017, 858)

Bachar also notes that in her interviews, government attorneys often used military-related phrases such as “joining forces,” “platoon,” and “war of attrition” in order to depict what they perceived to be their part in the “battle” against claims for losses inflicted by the IDF in what the government attorneys viewed as combatant activities (2017, 856). It seems that government attorneys view themselves as acting in a way that complements, and perhaps is even a part of, the military’s belligerent activities.

I will refer to this treatment of tort claims and their regulation as means of warfare as “tortfare,” which has two complementary elements. First is the identification of or belief in tort litigation as a form of combat. Government attorneys are not merely reacting to something that happened on the battlefield, they see themselves in an active theater of operations. The courtrooms are the battlefield, plaintiffs and lawyers are the combatants, and the weapon being used is the law. Second, tort law and its regulation are re-designed and deployed to facilitate or support actual military goals. Such use could be found in Israel, when its courts imposed punitive damages on the Palestinian National Authority for losses incurred by Jewish Israeli nationals in terrorist activities (Estate of Mantin v. Palestinian Authority 2017; Estate of Ben Shalom v. Palestinian Authority 2017). The United States has also enacted laws that enabled it to act in a similar way against Syria, Iran, and Afghanistan, for example (28 U.S.C. § 1605A 2010; Abraham Reference Abraham2019b).

Identity is a significant factor in this context. As is indicated in Figure 2 and Table 1, the identity of the bearer of liability has a statistically significant effect on the level of deterrence indicated by respondents, as does the nationality of the individuals to whom compensation is owed. Respondents reported higher levels of deterrence in the hypothetical scenarios in which liability could be imposed on them as opposed to on the state, as well as when liability was to be owed to enemy civilians rather than to their fellow citizens.

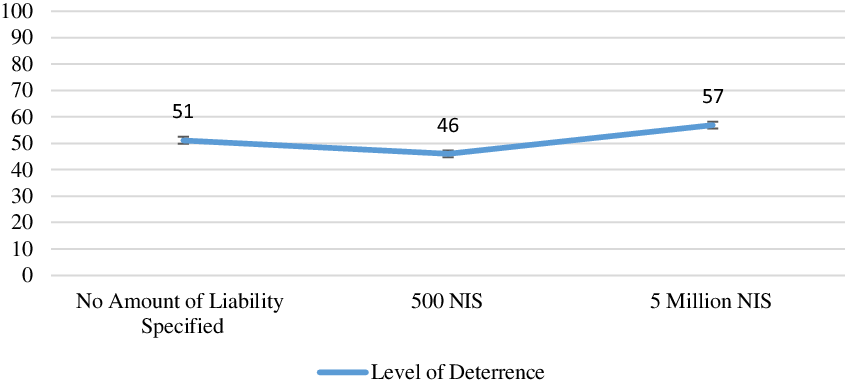

Additionally, there are also indications in the survey that the amount of compensation owed to the injured party is statistically significant, as illustrated by Figure 4.Footnote 26 Respondents’ level of deterrence was higher when the hypothetical scenario presented to them suggested that liability would be for the amount of five million ILS, and lower when it was for 500 ILS (equivalent to roughly 1.5 million USD and 150 USD, respectively). This result seems intuitive. The higher the risk, the greater effect it should have.

Figure 4. Level of Deterrence vis-à-vis Amount of Liability. Note: Level of deterrence measured on a scale of 0–100.

Table 1. Paired-Sample t-tests of Level of Deterrence

Note: Level of deterrence measured on a scale of 0–100.

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001Footnote 27

Still, the significance of the actual pecuniary costs of an imposition of tort liability is not in the effect pecuniary costs have on the state’s ability to engage in combatant activities. In fact, state actors seem to be somewhat indifferent to pecuniary costs in this sense. As government attorney GA2 argued: “the MoD is a body with a budget of billions [of ILS]. These cases [tort cases that arise from combatant activities] are peanuts” (Interview with GA2, February 2019). Furthermore, all three groups of actors have indicated that tort liability is not accounted for when deciding whether and how to engage in warfare.

Rather, what seems to matter is what an imposition of tort liability symbolizes. A positive court ruling for a plaintiff in any tort claim means that the defendant has committed a wrong against the plaintiff. In the context of tort liability for losses that were inflicted during warfare, such a finding would mean that Israel, through the operation of its security forces, wronged an individual—most commonly a Palestinian individual.

Some state actors might take these rulings personally, despite not being defendants or personally shouldering the costs of liability. Government attorney GA1 expressed that “in cases against the state, especially on sensitive subjects like the Intifada, you feel the state’s loss … It is not just a sense of personal success that drives you, it is a sense of justice towards the state … It is a sense of the state is me, like Louis XIV” (Interview with GA1, February 2019).

Other state actors might view such instances of impositions of liability as a sign that something in the law should be amended to better reflect what they believe to be the right result in similar future cases. As government attorney GA3 stated: “You know that there is a problem when you deal with a topic too much, or you pay too much, or that the courts criticize you, or that you spot something illogical and problematic, either in a single major case or over a series of many similar cases” (Interview with GA3, February 2019). Put differently, a single high-profile case or a series of similar low-profile cases could motivate actors to amend the law, but this result depends on whether an issue caught an actor’s attention. As the data above indicate, the attention of multiple state actors was caught when multiple tort claims were filed and won by Palestinian plaintiffs in relation to the operations of the state’s security forces.

LESS LIABILITY DOES NOT MEAN ACTING WITH GREATER CARE

The above data suggest that tort liability for belligerent activities under-deters. Politicians, combatants, and government attorneys indicated that when it comes to warfare, an imposition of tort liability and the pecuniary costs of liability are irrelevant factors in the decision-making process. Even though they did seem to care about what an imposition of liability for wrongs that were inflicted during battle represented to them, it did not affect their consideration as to whether to engage in belligerent activities and how to conduct them. Put differently, the study demonstrates that tort liability did not prompt the relevant state actors to act more carefully when engaging in combat.

Rather, state actors cared about other considerations, such as promoting security interests by achieving military goals, or eliminating the possibility that a court would find that the state or its combatants had committed a wrong against the enemy’s civilian population. In this respect, tort liability under-deterred the various actors, and hence the state, in deciding whether to engage in combat and how to conduct belligerent activities.

Moreover, the three preconditions for deterrence—choice, information, and internalization of costs—are lacking to various degrees during warfare. While politicians believe that they have complete freedom to choose whether to engage in combat, they do not necessarily have the knowledge to determine how to do so. Instead, they defer to high-ranking combatants, who decide how and when to act; lower-ranking combatants sometimes maintain some degree of choice as well. Still, once a legitimate order has been given, either by politicians to high-ranking combatants or by high-ranking combatants to lower-ranking combatants, there is no choice regarding whether to engage in a combatant activity. Furthermore, while government attorneys advise both politicians and combatants on the legality of their activities, they do not decide whether certain activities will be engaged in or refrained from, and their advice generally supports rather than hinders combat.

As for the information precondition, government attorneys seem to be the best informed of the three groups of state actors in relation to the risks of tort liability. They are an information hub, but their ability to spot patterns, analyze cases, and offer feedback to politicians and combatants is limited due to structural and budgetary deficits. Information is mostly gathered by individual attorneys and conveyed on an ad hoc basis, which makes retention, examination, and transfer of knowledge difficult. Even when such knowledge exists, none of the three groups of actors conceive of potential tort liability as a relevant consideration in relation to whether and how to conduct belligerent activities, and so it is not passed on.

However, it is the third precondition for deterrence—the internalization of the costs of wrongdoing—that is most clearly unmet. No individual of any group of state actors bears the costs of wrongdoing, mainly as it is the state that is sued rather than individual public officials, and due to the general immunities that public officials enjoy. Even in instances in which an individual official is sued and she is not immune, the state will subrogate or indemnify her. In addition, the costs of liability do not affect the operation of any group of actors. Instead, either they are budgeted for in advance or funds for them are procured from the Ministry of Finance, and neither instance has a negative effect on the budget of any of the groups of actors or their ability to operate. In this sense, it seems that the state’s deep pockets make the pecuniary costs financially unremarkable, even though their aggregated amount is in the hundreds of millions of USD.

Nevertheless, the imposition of tort liability had a noteworthy side effect in the particular context of warfare. As the study reveals, tort litigation and liability prompted politicians and government attorneys to pursue three initiatives. First, they have considerably expanded the scope of the combatant activities exception to such a degree that its constitutionality is questionable. The exception now applies to policing-related losses, which are not necessarily of a combatant nature. Furthermore, immunity is granted against claims of civilians who are nationals or residents of an enemy state regardless of the circumstances in which a loss was inflicted on them.Footnote 28 Second, government attorneys pushed for procedural requirements that make the filing of claims against the state very difficult, and hence limit the number of tort cases that reach the courts.Footnote 29 Third, Israel made it very challenging for Palestinian plaintiffs and their witnesses to obtain entry permits to testify, and so their ability to support their claims is partially, and at times entirely, frustrated.Footnote 30