Introduction

Taxation is viewed as the basis for stable social contracts between states and citizens, but there remains little understanding of how weak states initially expand their tax bases. The need to build stronger tax infrastructure is especially acute in sub-Saharan Africa, where states have generally relied on customs and excise taxes, foreign aid, and mineral rents. These revenue sources are more volatile than direct taxes, such as income and property tax, and they do not trigger the state-society bargaining around tax that is presumed to generate democratic accountability (De la Cuesta et al. Reference De la Cuesta2022; Paler Reference Paler2013; Ross Reference Ross2012). Growing recognition of the importance of direct taxation has generated new research in low-income countries in recent years, examining the drivers of compliance with consumption and value-added tax (VAT) (Eissa et al. Reference Eissa2014; Naritomi Reference Naritomi2019; Pomeranz Reference Pomeranz2015), property tax (Ali, Fjeldstad, and Sjursen Reference Ali, Fjeldstad and Sjursen2014; Collin et al. Reference Collin2021; Jibao and Prichard Reference Jibao and Prichard2016), and business formalization (Benhassine et al. Reference Benhassine2018; Bruhn and McKenzie Reference Bruhn and McKenzie2014; De Mel, McKenzie, and Woodruff Reference De Mel, McKenzie and Woodruff2013; Maloney Reference Maloney2004). Like the classic work on taxation (Bates and Lien Reference Bates and Lien1985; Levi Reference Levi1989), newer work is rooted in the logic of fiscal exchange, in which the state exchanges positive or negative goods (public services or enforcement) for tax compliance by citizens.

In settings of low state capacity, however, fiscal exchange’s assumption of unmediated state-citizen contact is often violated. Informal institutions and political brokers often mediate individuals’ contact with the state, shaping citizens’ expectations of the state in different ways (Lemarchand Reference Lemarchand1972; Lund Reference Lund2006; Lust Reference Lust2022). Non-state actors are particularly consequential in settings of low state capacity, as in sub-Saharan Africa and low-income countries in other regions, where they often play vital roles in the provision of public goods (see, for instance, Baldwin Reference Baldwin2016; Brass Reference Brass2016; Cammett Reference Cammett2014; Cammett and MacLean Reference Cammett and MacLean2014; Post, Bronsoler, and Salman Reference Post, Bronsoler and Salman2017). Formal tax compliance in these contexts is often very low, yet informal taxation – the collection of fees and rents by non-state actors – is often ubiquitous (Joshi and Ayee Reference Joshi, Ayee, Brautigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008; Olken and Singhal Reference Olken and Singhal2011). Informal taxation, which Lust and Rakner Reference Lust and Rakner2018 term ‘social extraction’, is often how communities fund health care, education, and other public goods where state services provision is weak. Particularly important for service delivery and informal tax extraction are organizations and authorities that we term ‘social intermediaries’. Though these actors may collaborate with state actors on particular tasks, they are organizationally autonomous from the state and have sources of legitimacy that are not linked to their relationship with the state. These actors may provide governance in the absence of the state, but they may also mediate interactions between states and citizens, as when they bargain with the state on behalf of their constituencies or serve as clientelistic brokers.

How do social intermediaries affect state efforts to build a social contract around tax? Existing research gives rise to contradictory expectations about the impact of these institutions. One perspective suggests that states and social institutions effectively compete with one another: where non-state institutions possess more authority and legitimacy, individuals may view the state as a site of extraction rather than a legitimate, service-providing entity to which they should pay tax (Ekeh Reference Ekeh1975). A mechanism of this kind is often asserted as underlying the relationship between ethnic diversity, clientelism, and lower levels of public goods provision (for an overview, see Hicken and Nathan Reference Hicken and Nathan2020). Second, non-state provision of public goods may crowd out demand for state-provided public goods, lowering tax morale (Bodea and LeBas Reference Bodea and LeBas2016; Castañeda, Doyle, and Schwartz Reference Castañeda, Doyle and Schwartz2020). Third, some evidence suggests that citizens may find informal taxes to be more fair than formal taxation, fueling resistance to state tax collection or feelings that formal tax collection amounts to ‘double taxation’ (Van den Boogaard, Prichard, and Jibao Reference Van den Boogaard, Prichard and Jibao2019).

But there are also reasons to believe that the actors we term ‘social intermediaries’ could be powerful partners in tax collection and other state-building efforts, especially in settings where state institutions are weak. Intermediaries often benefit from trust and affective loyalty that formal state actors do not possess. This greater credibility among citizens may stem from the provision of services or protection to their community members, from their informational and enforcement advantages over those of bureaucrats, or from non-material sources of legitimacy. As a result, non-state actors have sometimes served as effective state partners in tax collection and state-building (Balan et al. Reference Balan2022; Goodfellow Reference Goodfellow2015; Joshi and Ayee Reference Joshi, Ayee, Brautigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008; Prichard and Van den Boogaard Reference Prichard and Van den Boogaard2017).

Should we view strong social intermediaries as potential complements in state-building, or are they better viewed through a lens of displacement or substitution? If the former, are there conditions under which non-state actors are more effective in promoting formalization and tax compliance? To examine this, we implemented a field experiment in 112 marketplaces in Lagos, Nigeria, where the state is looking to build its fiscal capacity and where marketplace associations serve as a strong social intermediary. The randomly assigned intervention consisted of individual visits to over one thousand vendors to encourage them to register for an electronic tax clearance card (e-TCC), which is the centrepiece of Lagos State Government formalization efforts. Registration for the e-TCC required payment of the annual ‘presumptive tax’, a flat income tax that is standard for all informal sector workers.

Our experiment varied the identity of the agent delivering this tax appeal, so that vendors would either be approached by a representative of the Lagos Internal Revenue Service (LIRS) or the marketplace association. It also varied the nature of the appeal, emphasizing either the public goods benefits of tax payment or the costs of potential punishment for evasion. In this context, marketplace associations are generally governed at the market level by an iyaloja or ‘market mother’, and are then coordinated at the state level by the Lagos Market Women and Men Association (LMWMA), itself headed by the Iyaloja-General of Lagos. In addition to its active roles in market governance and state-society bargaining, the Yoruba-dominated institution plays a key role in mobilizing votes for the ruling party.

Our starting expectation was that the social intermediary would serve as an effective agent of the state, leading to higher levels of tax registration among those who received the intermediary-delivered tax appeal. We expected tax appeals to be particularly effective when delivered by organizationally effective and well-trusted agents, and we expected members of the dominant ethnic group – who are closer to the state and are advantaged in terms of services and clientelistic distribution – to be more responsive to appeals.

Our findings ran contrary to these expectations in two important ways. First, we found no evidence that intermediary-delivered appeals were effective in boosting formalization and tax compliance among any sub-group. Further, among those who trusted these social intermediaries more than they did the state, tax appeals delivered by state agents actually lowered formalization and tax compliance. One potential interpretation of these findings is that there is a substitutive relationship between marketplace associations and the state rather than the complementarity we expected. Second, positive treatment effects of tax appeals were found only in the state messenger arm and were driven by outgroup members. Since ethnically defined ingroup members hold most elected political offices and civil service jobs in Lagos, as in other clientelistic contexts, we had expected ingroup members to be more receptive to tax appeals. This finding was also surprising to our state intervention partner, LIRS, as they viewed markets with more minority vendors as hostile to their tax collection efforts.

These findings make an important contribution to our understanding of why formalization and tax campaigns often fail. Such campaigns have become more prevalent as international financial institutions, donors, and state governments have all embraced the expansion of internally generated revenue as an important policy goal. An increasing number of policy interventions in low-income countries have focused on the informal sector, where a lack of formal business registration and tax non-compliance can harm businesses’ access to capital and impede their growth. Yet formalization campaigns have often produced weak or non-durable effects, even when informal sector businesses are provided with immediate benefits in exchange for registration or tax compliance (Bruhn and McKenzie Reference Bruhn and McKenzie2014; De Mel, McKenzie, and Woodruff Reference De Mel, McKenzie and Woodruff2013; Galiani, Melendez, and Ahumada Reference Galiani, Melendez and Ahumada2017; Maloney Reference Maloney2004). Formalization efforts have typically adopted a state-centred framework, neglecting both pre-existing social institutions and the credibility challenges that state actors face in these contexts.

We suggest that inattention to the role of strong non-state actors and, especially, social intermediaries like marketplace associations might be one reason for policy failure. Our article provides some evidence for why social intermediaries can ‘crowd out’ or dampen demand for tax bargains between states and citizens. First, our findings are consistent with potential substitution between state and non-state actors. Where individuals rely on non-state providers – especially where these organizations are trusted entities – they are both less likely to comply with state attempts to collect formal tax and less likely to form direct, unmediated relationships with the state. Second, we find no support for the idea that weak states might be able to ‘piggyback’ on the resources and reputations of strong societally-rooted actors to improve tax collection. Our findings thus contrast with recent evidence from the Democratic Republic of Congo that city chiefs can boost tax compliance when they deliver appeals on behalf of the state (Balan et al. Reference Balan2022). Though African chiefs are rarely fully autonomous from the state, they share many of the other qualities of social intermediaries. The divergence in findings may come from intermediaries’ different levels of autonomy from the state, differences in the legitimacy of actors, or differences in levels of state capacity across the two contexts. We return to this discussion of generalizability in the conclusion.

Tax Compliance in Weak States

Both classic and modern work on taxation is rooted in the logic of fiscal exchange between states and citizens. According to the logic of fiscal exchange, the individual costs and benefits of tax compliance drive citizen behaviour. The direct costs of registration, uncertainty about tax burden, and insufficient benefits from compliance are viewed as key obstacles to expanding the tax base (see the discussion in, for example, Benhassine et al. Reference Benhassine2018; Bruhn and McKenzie Reference Bruhn and McKenzie2014). The presumption is that individuals will only choose to comply with registration or tax appeals when the expected benefits of registration and tax compliance outweigh the costs of non-compliance. Convincing citizens that there are benefits to tax payment – or that there are costs to evasion – may be an especially difficult task in low-income countries. In countries like Nigeria, our research site, the majority of citizens do not pay income tax, and property taxes are often not assessed or collected in rural areas or in low-income areas within cities. Furthermore, the informal sector employs approximately eighty per cent of the labour force, and a history of state predation has resulted in populations that actively evade contact with the state. The prevalence of tax evasion and unregulated economic activity creates special obstacles for states attempting to alter citizen perceptions of the likelihood of penalties for non-compliance.

Weak state capacity facilitates the rise of non-state actors who provide services and bargain with the state on behalf of citizens. In the introduction, we pointed out that there is conflicting evidence about whether these social intermediaries can serve as effective tax agents. A set of recent studies in the Democratic Republic of Congo suggest that the informational advantages of chiefs make them effective state tax collectors (Balan et al. Reference Balan2022) and also that delegation of tax collection to these agents improves governance outcomes and increases the perceived legitimacy of these actors (Bergeron et al. Reference Bergeron2023). Other studies, however, have suggested that strong non-state institutions and non-state services provision can have positive, negative, or mixed results on formal tax collection and revenues (Bodea and LeBas Reference Bodea and LeBas2016; Castañeda, Doyle, and Schwartz Reference Castañeda, Doyle and Schwartz2020; Martin and Selm Reference Martin and Selm2022). Beyond taxation, a large body of research suggests a logic of complementarity, in which strong social intermediaries can improve the performance of state public health campaigns (Tsai, Morse, and Blair Reference Tsai, Morse and Blair2020; van der Windt and Voors Reference van der Windt and Voors2020), public goods delivery (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2019; Brass Reference Brass2016), and other aspects of governance (Tsai Reference Tsai2007). Other research suggests that the involvement of non-state actors in public goods provision can lessen citizen orientation to the state and even erode state capacity over time (Lund Reference Lund2006; MacLean Reference MacLean2017; Mann Reference Mann2015).

This article addresses the core question of complementarity versus substitution by directly testing the relative efficacy of state agents and social intermediaries as messengers of tax appeals. We recognize, however, that the effectiveness of these actors in prompting tax compliance may also vary depending on an individual’s past experience with these institutions and other factors, such as individual identity. Consistent with the literature on fiscal exchange and formalization, we posit that individuals will only comply with a tax appeal when it results in real changes to the perceived costs and benefits of tax compliance. Our experiment randomized the content of appeals to stress either increased public goods or increased enforcement, but we expected respondents’ beliefs about the trustworthiness and credibility of these messages to depend on past experiences that naturally varied within our sample. Put differently, the content of a message may be appealing or alarming, but its impact is blunted if it is dismissed as ‘cheap talk’.

Individuals are more likely to be influenced by a messenger that they deem as trustworthy or as credible, qualities that are shaped by the individual’s past experience with the agent delivering the message. Consistent with the literature on tax morale, we expect higher levels of trust in the agent to promote voluntary compliance since compliance is being requested by a trusted party. Where individuals trust the agent, they may have greater faith in the good intent of the actor or may be more positively disposed to policies the actor proposes. Second, we expect tax appeals to be more likely to shift perceived costs and benefits when promises of service delivery or enforcement are deemed credible. Credibility is likely to be higher when the individual has received benefits or services before from this agent and when the individual has past experience with the agent’s enforcement and monitoring activity. Given these likely heterogeneous effects on trust and credibility, we measured at baseline relative trust in the marketplace association vis-á-vis LIRS, as well as past contact with agents, attribution of responsibility for services provision, and experience and expectation of enforcement.

A final factor expected to shape individual response to tax appeals is political ingroup status. In Africa, where ethnic clientelism is prevalent, members of politically dominant ethnic groups are likely to have greater access to state resources and are likely to expect that tax-funded programmes will disproportionately benefit them over their ethnic outgroup peers. Research on tax argues that an expectation of privileged treatment can boost tax remittance among ingroup members (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2003). In our context, most individuals who are viewed as indigenous to the city are Yoruba, and Yoruba have long controlled both state and local politics.

The above theoretical discussion leads us to our main hypotheses, registered in our pre-analysis plan:Footnote 1

Hypothesis 1. Social intermediaries will be more effective at increasing compliance than state actors. In our context, this is due to (a) the marketplace association’s existing role in taxing vendors and (b) its role in resolving intra-market disputes and other service provisions. Footnote 2

Hypothesis 2. Tax appeals will be most effective when delivered by an agent who is trusted. Thus, messages delivered by agents with relatively higher levels of reported trust will be more effective in shifting tax registration and compliance. Footnote 3

Hypothesis 3. Tax appeals will be more effective when the content of the message is viewed as credible. Credibility will vary according to (a) individuals’ past experiences with service delivery and (b) enforcement action by the agent delivering the message. Footnote 4

Hypothesis 4. Vendors who are co-ethnics of the ruling party will be more likely to respond to tax appeals, since they may expect that they will be advantaged in terms of service delivery or differential enforcement. Footnote 5

Research Context

To study the relationship between taxation and social intermediaries in a weak-state setting, we collect data and conduct a field experiment in Lagos, Nigeria. Nigeria has among the largest informal sectors in the world, even by African standards, and its largest informal markets are situated in the country’s biggest city, Lagos. Lagos’s markets also have a widely recognized and socially embedded intermediary structure – composed of market-level associations or MPAs – that participate in all the aforementioned activities related to tax collection: MPAs collect taxes for the state, they collect informal taxes instead of the state, they provide services to markets, and they enter into negotiations with the state on behalf of market vendors. In Nigeria, state governments have little power to assess and collect most taxes and levies, and the focus of Lagos State Government (LSG) tax mobilization efforts has, therefore, been personal income tax, which is also the focus of our study. LSG has increased the amount of revenue collected from income tax by more than 400 per cent since 2006 and is increasingly devoting its attention to penetrating the informal sector. In 2006, the Lagos State Government created a centralized, independent revenue authority, the Lagos Internal Revenue Service, to improve fiscal capacity, reduce leakage of collected revenue, and insulate tax collection from political influence.Footnote 6

The centrepiece of tax registration and collection efforts in Lagos is the electronic tax clearance card (e-TCC), which electronically records all payments made by the individual to the state government. To receive the e-TCC, the individual must register as a taxpayer and pay one year’s income tax liability in advance. Increasingly, LSG requests citizens to produce the e-TCC to prove tax compliance when they try to access state services, such as courts or state-funded secondary schools. The cost of producing the e-TCC exceeds the presumptive annual income tax set for informal sector workers (N4,500 or USD 12.86 at the time of our intervention), but LIRS views the e-TCC as a way of getting informal sector workers and, especially, market vendors ‘into the tax net’. By 2018, LIRS had established 40 ‘mini tax stations’ to directly target the informal sector and issue e-TCCs, several of which are situated in or near Lagos’s largest markets. Alongside the expansion of tax collection infrastructure, LSG has also improved service provision, including in the low-income neighbourhoods where informal sector workers and vendors live. Reformist governors have made the ‘taxes for services’ link central to their political campaigns, and LSG agencies have also encouraged income tax payment via bulletin boards and radio jingles.

Taxation and the Role of Social Intermediaries in Lagos

LIRS and LSG are in some degree of competition with alternative governance structures that provide services to their members, extract payments for those services, and attract the affective loyalty of some individuals. Individual markets in Lagos are characterized by a complex institutional landscape including MPAs that commonly link together all vendors in the market, sectoral unions, and even building or ‘plaza’-level associations. Most MPAs are headed by a ‘market mother’, an iyaloja in Yoruba, though some markets may also have a babaloja (‘market father’), a chairperson, or other leader. Most of Lagos’s MPAs are affiliates of the Lagos Market Woman and Men Association (LMWMA), which is headed by the Iyaloja-General of Lagos. The Iyaloja-General occasionally intervenes in markets to settle associational disputes and also plays a role in market-level leadership selection. Iyalojas are best viewed as equivalent to other traditional chieftaincy and sub-chieftaincy structures. For instance, the Iyaloja-General is crowned by the Oba (king) of Lagos and cannot be removed by subordinate iyalojas, and, though market-level MPAs are autonomous in some respects, market-level iyalojas generally follow the political endorsements and overall direction of the Iyaloja-General.

Marketplace associations often stand in for state institutions that are viewed as corrupt, inefficient, or even predatory.Footnote 7 Some MPAs are very active in solving conflicts between vendors, facilitating access to goods and services, collecting fees, and negotiating with the government, while others are relatively weak (Grossman Reference Grossman2020; Nwankwo Reference Nwankwo2019).Footnote 8 Many MPAs also seek to control state access to their vendors, refusing to provide the state with the precise number of vendors within a market or even barring or monitoring LIRS staff who attempt to enter. MPAs extract payment for their own services and collect fees used to pay for third-party services such as garbage and security. Forty-seven per cent of vendors in our sample report that they cannot avoid paying fees to their MPA.

In recognition of the associations’ power and presence in the markets, the Lagos State Government and local governments within Lagos have entered in the past into arrangements that might be termed ‘tax farming’, or the use of non-state actors to collect tax on behalf of the state (De Gramont Reference De Gramont2015; LeBas Reference LeBas2013). Past LIRS informal sector registration drives relied on MPAs and sectoral unions, even issuing individual tax clearance cards that designated the vendor’s associational membership. For many years, LIRS had an established procedure by which it would issue individual tax receipts for income tax revenues collected and remitted to LIRS via MPAs. In exchange, MPAs and their peak association lobby the Lagos State Government for market infrastructure and other state benefits, often using promises of tax compliance as a bargaining chip. Even though state funds may pay for new lighting or upgrading of roads near markets, MPAs often claim credit for these improvements and for expanding their members’ access to government contracts and subsidized loans. The interest of the overarching LMWMA has been to preserve the mediated nature of contact between the state and its vendors. As evidence, the Iyaloja-General said that she supported our research in hopes that it would prove LIRS should collect taxes via the MPA-controlled pathway.Footnote 9

But LIRS official policy increasingly seeks to circumvent the marketplace associations. Tax officials are concerned that continued reliance on social intermediaries results in higher levels of evasion and also prevents movement from a flat rate income tax regime to one based on individual assessment on the basis of income. Recent LIRS proposals have included investments in the mapping of marketplaces and enumeration of individual vendor stalls,Footnote 10 as well as the deployment of an LIRS task force to individual markets to directly observe vendor volume and profit.Footnote 11 Despite these new initiatives, LIRS staff still often rely on the cooperation and public support of MPA leaders. Therefore, changes in formal policy would not be visible to most vendors, and vendors would not view it as unusual for an MPA to deliver a tax appeal on behalf of the state. In sum, vendors in Lagos have fiscal experiences with both social intermediaries and formal state officials, which shape assessments of these agents’ ability to detect and punish evasion and their trustworthiness when it comes to delivering in the future.

Identifying Political In-Groups and Out-Groups

In addition to differences in the trust and credibility accorded to state officials and MPAs, individuals’ responses to tax appeals may be affected by their political ingroup or outgroup status. Even though Lagos politicians do not use overt ethnic appeals, ethnicity is politically salient in Lagos. The ruling party relies on members of the Yoruba majority ethnic group for electoral support, while opposition parties draw support from ethnic minorities.Footnote 12 It is estimated that about a quarter of the city’s population is non-Yoruba, and about half of the traders in our sample are non-Yoruba, primarily Igbo.

Ethnic minorities are disadvantaged by clientelistic politics since they are presumed to be opposition voters.Footnote 13 Areas of Lagos dominated by ethnic minorities have generally lagged behind in terms of land regularization and service provision (Oduwaye Reference Oduwaye2008, 135). Formal interviews and informal discussions during our fieldwork suggest that ethnic minorities may be differentially targeted for extraction and enforcement by state officials and local authorities. An interview with an Igbo vendor in a Yoruba-dominated market remarked that ‘it was only those they can threaten, like the Igbos, that paid … no Yoruba person paid that tax’.Footnote 14 An Igbo vendor in another market explained that the Yoruba-dominated MPA led meetings in Yoruba, discouraging minority vendors from participating and limiting access to information.Footnote 15 This accords with evidence of ethnic discrimination in shop rent in our quantitative data, whereby non-Yoruba vendors pay on average more than twice as much in shop rent compared to Yoruba vendors with equivalent shop sizes. Consequently, ethnic minorities may assess the likelihood of public goods receipt or enforcement differently than Yoruba market vendors.

Research Design

To test our hypotheses, we randomly vary exposure to tax appeals delivered by either a social intermediary (MPA) or the state (LIRS) and framed either around the costs of evasion (Enforcement) or the benefits of compliance (Public Goods) among a sample of informal sector vendors selected from marketplaces all over Lagos. Our experimental design circumvents some of the inference problems that characterize observational research. If we rely solely on observational data, assigning causality to any correlate of tax compliance is problematic because the types of people or groups who regularly comply differ from those who do not on a number of dimensions.

We conducted a baseline survey that collected basic information about the character of the random sample of markets and assessed baseline attitudes about taxation and perceptions of different actors. Three months later, we implemented an NGO-delivered Formalization Intervention, provided to all participants in this study sample (N = 1,277), to provide basic information about income tax liability and how to formalize. About three months after that, we implemented the treatment for this study, the Tax Appeal Intervention. Finally, we conducted an in-person endline survey with a median time of four months between treatment and measurement. The fieldwork was conducted between March 2018 and March 2019 (see timeline in Appendix 1).

Because our interventions could theoretically expose study participants to greater tax enforcement, we took seriously the ethical implications and likelihood of such an outcome.Footnote 16 While vendors would have full information about the short-term costs of formalizing, the state could subsequently raise tax rates and thereby alter costs. It is theoretically possible that participation in our study could increase subjects’ visibility to the state. We took steps to mitigate these concerns, both by sending LIRS staff to markets outside the catchment areas of the tax stations where they were typically based, providing these staff with no names or contact details of vendors, and securing an explicit guarantee from LIRS that study participants would not be disadvantaged. The risk of future enforcement is also low given the weak administrative capacity, which renders income tax compliance largely voluntary in Lagos. Further, some of the greatest financial risks that vendors face are discrimination and vulnerability to informal tax extraction, which formalizing could mitigate.

Sample

To improve the generalizability of our findings, we sought to create a representative sample of informal market vendors in Lagos. This was challenging because of the lack of a reliable sampling frame of Lagosian markets and their characteristics. However, we collected, size-graded, and geo-coded 599 unique markets from several existing sources.Footnote 17 Once a market was selected for the sample using stratified randomization, the number of respondents to be interviewed within the market was determined by the market size category. Individuals were sampled using a random walk with a large sampling gap (twenty vendors) to mitigate potential spillovers. Vendors without a fixed stall and those who sold only low-value foodstuffs were excluded from selection since they were unlikely to benefit from formalization and were also least likely to be targeted for collection by LIRS.

Interventions

All individuals for whom we report data first received the NGO-delivered Formalization Intervention, which was designed to reduce the human capital cost of obtaining an e-TCC, reduce uncertainty about the tax burden of formalization, and provide information about the individual benefits of formalization. Tax Appeal interventions consisted of visits to individual vendors by messengers who delivered a short verbal script and a longer video on a tablet computer. Messengers identified themselves either as state officials or as representatives of the marketplace associations’ umbrella bodies. Appeals primed the possible costs of tax evasion or the potential public goods benefits that may accrue from payment and included videos that reinforced both the messenger and the framing. Specifics about each of the distinct Tax Appeal arms are described below; the full text of the intervention scripts is available at https://tinyurl.com/lagostaxappealsonline. An appeal consisted of one of two frames and one of two messengers.

Public Goods Frame: This variant of the tax appeal’s message highlighted the idea that income tax revenue is used to pay for public goods and services. The video includes an interview with former Governor Fashola linking tax payment to service delivery and testimonials from vendors, including beneficiaries of improved infrastructure and the Lagos State Employment Trust Fund subsidized loan programme.

Enforcement Frame: This variant of the tax appeal’s message focuses on the legality of tax compliance and the consequences for noncompliance such as fines. The video features television coverage of former Governor Fashola elucidating the need for voluntary tax payment and filmed testimonials of vendors including those from Computer Village, a large market that was temporarily shut for non-payment of personal income tax.

LIRS Messenger: The tax appeal was delivered by staff of the Lagos Internal Revenue Service seconded to our project, made possible by a close relationship between the research team and LIRS. The LIRS agents wore office uniforms and hats. The videos included speeches by the LIRS Director of the Informal Sector & Special Duties, the most senior official tasked with the informal sector.

Marketplace Association (MPA) Messenger: The tax appeal was delivered by local consultants on behalf of the Lagos-wide marketplace association umbrella body with the explicit agreement and endorsement of the Iyaloja-General of Lagos. These staff wore t-shirts bearing the market organization’s logo and brought a letter of endorsement from Mrs Folashade Tinubu-Ojo, the Iyaloja-General of Lagos. We reinforced the MPA agent treatment by including in our video statement from an Iyaloja, or ‘market mother’, from an out-of-sample market.

Individuals were assigned to the Formalization Intervention only or to Formalization plus each tax appeal message type and each tax appeal messenger type with a one-in-three probability.Footnote 18 The 2 × 2 factorial design and assignment probabilities are summarized in Fig. 1. Eighty-five per cent of respondents assigned to treatment complied; most non-compliers were unreachable or unfindable and only a handful declined treatment.Footnote 19

Figure 1. Research design and assignment probabilities.

To further increase precision in the assessment of [conditional] treatment effects, we blocked assignment on several key characteristics that we expected to moderate the effects of treatment. We blocked on marketplace size, expected to be associated with variation in associations and other unobserved heterogeneity. Larger markets have also been prioritized for extraction by LIRS. We blocked on shop rent, a proxy for vendor wealth since firm size has been shown to be a major predictor of the success of formalization interventions. We also blocked on perceived trustworthiness of the MPA relative to LIRS and prior contact with LIRS, which may moderate perceptions of one agent delivering tax appeals; pro-sociability, here the number of clubs or associations to which the respondent belongs, since higher levels of social capital may be associated with orientation toward MPAs and other non-state actors; and whether the respondent has friends in the market, as this might increase the possibility of treatment spilling over into the control group. Lastly, we blocked on a binary indicator of whether the vendor is Yoruba, given our expectation of preferential access to and treatment by the state.

Estimation

To Analyze treatment effects on outcome

![]() $Y$

, we calculate the intent-to-treat (ITT) estimate

$Y$

, we calculate the intent-to-treat (ITT) estimate

![]() ${\beta _1}$

of assignment to

${\beta _1}$

of assignment to

![]() ${\rm{Treatmen}}{{\rm{t}}_i}$

by evaluating the following model using OLS with robust standard errors (Judkins and Porter Reference Judkins and Porter2016):

${\rm{Treatmen}}{{\rm{t}}_i}$

by evaluating the following model using OLS with robust standard errors (Judkins and Porter Reference Judkins and Porter2016):

where

![]() ${X_i}$

is a vector of controls for blocking variables.

${X_i}$

is a vector of controls for blocking variables.

![]() ${\rm{Treatmen}}{{\rm{t}}_i}$

is a vector representing either the Messenger Treatment (Informal Agent vs. State Agent vs. Control) or the Message Treatment (Public Goods vs. Enforcement vs. Control). Due to power considerations that we discussed in our pre-analysis plan, none of our analyses test the joint effect of messenger and message treatments in our fully factorial design.

${\rm{Treatmen}}{{\rm{t}}_i}$

is a vector representing either the Messenger Treatment (Informal Agent vs. State Agent vs. Control) or the Message Treatment (Public Goods vs. Enforcement vs. Control). Due to power considerations that we discussed in our pre-analysis plan, none of our analyses test the joint effect of messenger and message treatments in our fully factorial design.

When we assess heterogeneous treatment effects or test a conditional hypothesis, we use the interaction equation:

where

![]() ${M_i}$

is the moderator of interest.

${M_i}$

is the moderator of interest.

Before presenting the results, we want to flag one potential concern about the credibility of the MPA treatment, since the MPA representative who delivered the message was not personally known to the vendor. The impersonal nature of the visit was intended to reduce the heterogeneity of treatment and ensure intervention fidelity in light of the complexity of the associational landscape in markets, which could lead individuals to have multiple attachments within the larger market structure. There is a trade-off, however, in that the character of our intervention could have reduced our ability to prime the vendor’s link to a more proximate social intermediary. To address this concern, we conducted qualitative interviews with thirty-six out-of-sample vendors from nine markets, in which we duplicated the MPA-delivered intervention and then asked vendors about their reactions. Most responses suggested that the MPA-delivered appeal effectively primed vendors to think of their relationship with their own marketplace association and its past actions (see Appendix 7 for specific evidence). These interviews also confirmed that most vendors viewed the Iyaloja-General as linked to their own marketplace leadership, and many viewed this relationship as directive. This suggests that the intervention largely functioned as intended, that is, it primed the relationship between the individual and their own market leadership.

Data

Our key outcome of interest – individual tax registration and compliance – is measured using the endline survey we conducted from December 2018 to March 2019. Our initial design and pre-registration anticipated using administrative data to measure this outcome, but, for the reasons we discuss below, we are limited to using the survey measure. Participants in the endline sample were directly asked if they had an e-TCC and to show proof of their registration; 20 per cent reported having one. It is possible that some of these participants dissembled, inflating the response rate due to social desirability bias. To increase confidence in our measure of tax registration, we thus use a second survey item. Self-reported e-TCC holders were asked to provide the issuance date. Of these, 40 per cent refused, 17 per cent provided the date, and 43 per cent said they were willing to provide it the date but did not have the card with them at the time. We consider the ninety-seven individuals who refused to provide the issuance date as those most likely to have falsely reported having an e-TCC. Our binary measure of e-TCC Registration thus codes as a 1 participants who report having an e-TCC and were willing to provide the issuance date. This reduces the overall rate of registration to 13 per cent in our sample, which is closer to LIRS’s own estimate.

A substantial portion of these e-TCC holders are likely to have registered prior to treatment. While we only have confirmed issuance dates for a small number of observations, 75 per cent of these were registered prior to treatment. Because the pre-treatment registration status of these individuals shrinks the pool of individuals available for persuasion, this will make it harder to detect treatment effects. It should not induce any bias, however, if pre-treatment registration is balanced across treatment, as we would expect under random assignment. We do find that pre-treatment registration is balanced across treatments.

In our initial design, we anticipated using administrative records to evaluate tax registration and payment outcomes. Unfortunately, the records we were able to retrieve through matching participant names, phone numbers, and partial addresses proved too unreliable. Instead, we use these administrative data to further mitigate concerns about social desirability bias in the survey data (see Appendix 11).

Key moderating variables were measured in the pre-treatment baseline survey. To test H2, we measure trust in the MPA and LIRS separately on a four-point scale. The mean trust in LIRS is 1.94 and the mean trust in the MPA is 2.20. Because they are highly correlated, we operationalize the moderator of interest as a binary Relative Trust variable, that is whether the respondent trusts LIRS weakly more (equally or more) (70 per cent), or their marketplace association strictly more (30 per cent). There is no statistical difference in relative trust by Yoruba ethnicity.

To test H3, we measure the perceived credibility of the Enforcement and Public Goods messages with an index access to services. The Access to Services Index is constructed from a battery measuring access at baseline to residential public goods and services, such as paved roads and street lights. To test H4, we use an indicator variable of whether the respondent self-reported their ethnic group as Yoruba.

Results

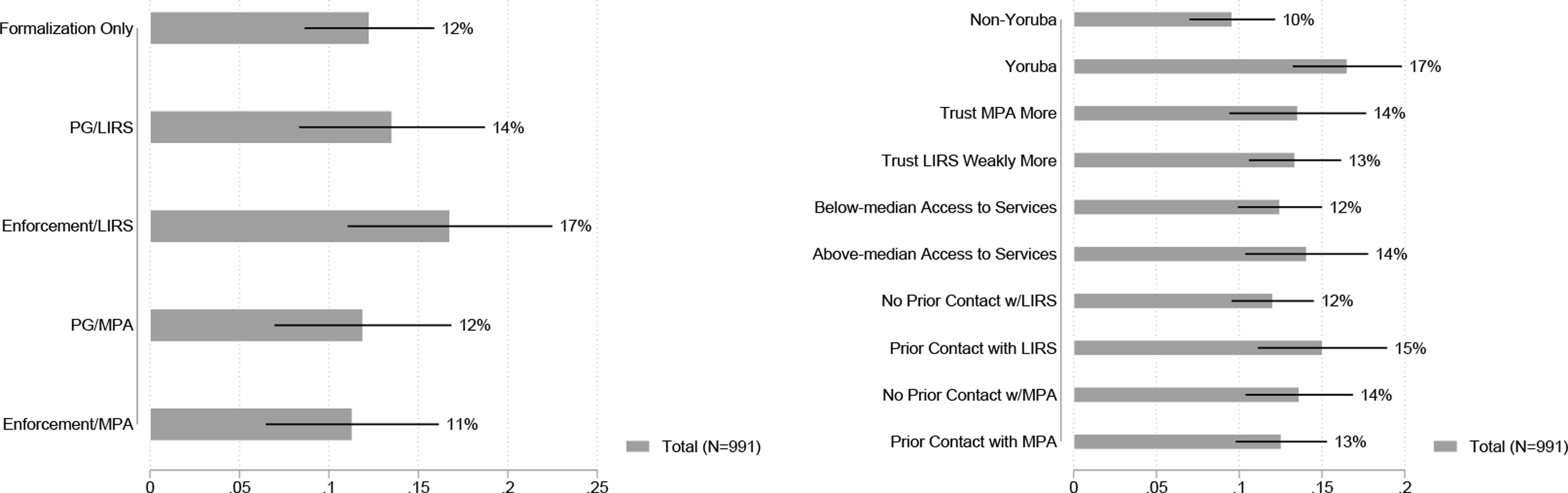

In this section, we use data from our baseline and endline surveys to evaluate the main hypotheses described above. The moderators and control variables are measured pre-treatment at baseline. The key outcome variable, measured at endline, is formalization and initial tax compliance measured by e-TCC registration, as discussed above. Before presenting the results, we plot the means and confidence intervals of our main outcome variable, e-TCC registration, across each unique treatment combination in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. The proportion of respondents reporting an e-TCC by condition and by moderator (with 95 per cent CIs).

To test Hypothesis 1, which predicted that the MPA agents would be more effective than the LIRS agents at inducing vendors to formalize, we estimate Equation 1 using the Messenger treatment vector as the key independent variable. Not only do we fail to find support for our hypothesis, but the relationship goes in the opposite direction. If anything, the LIRS agent is more effective at inducing e-TCC registration relative to the MPA agent (p = 0.17).

Moderating Effects of Trust in the Messenger

To test heterogeneous treatment effects in the next three subsections, we estimate Equation 2 using pre-specified moderating variables. In each case, a binary moderator is fully interacted with the categorical treatment variable (Messenger or Message treatment). For ease of interpretation, we plot the marginal effects of each treatment arm by the moderating variable separately, but these effects are estimated in a single regression. All regression results illustrated in the figures are reported in Appendix Table 1.

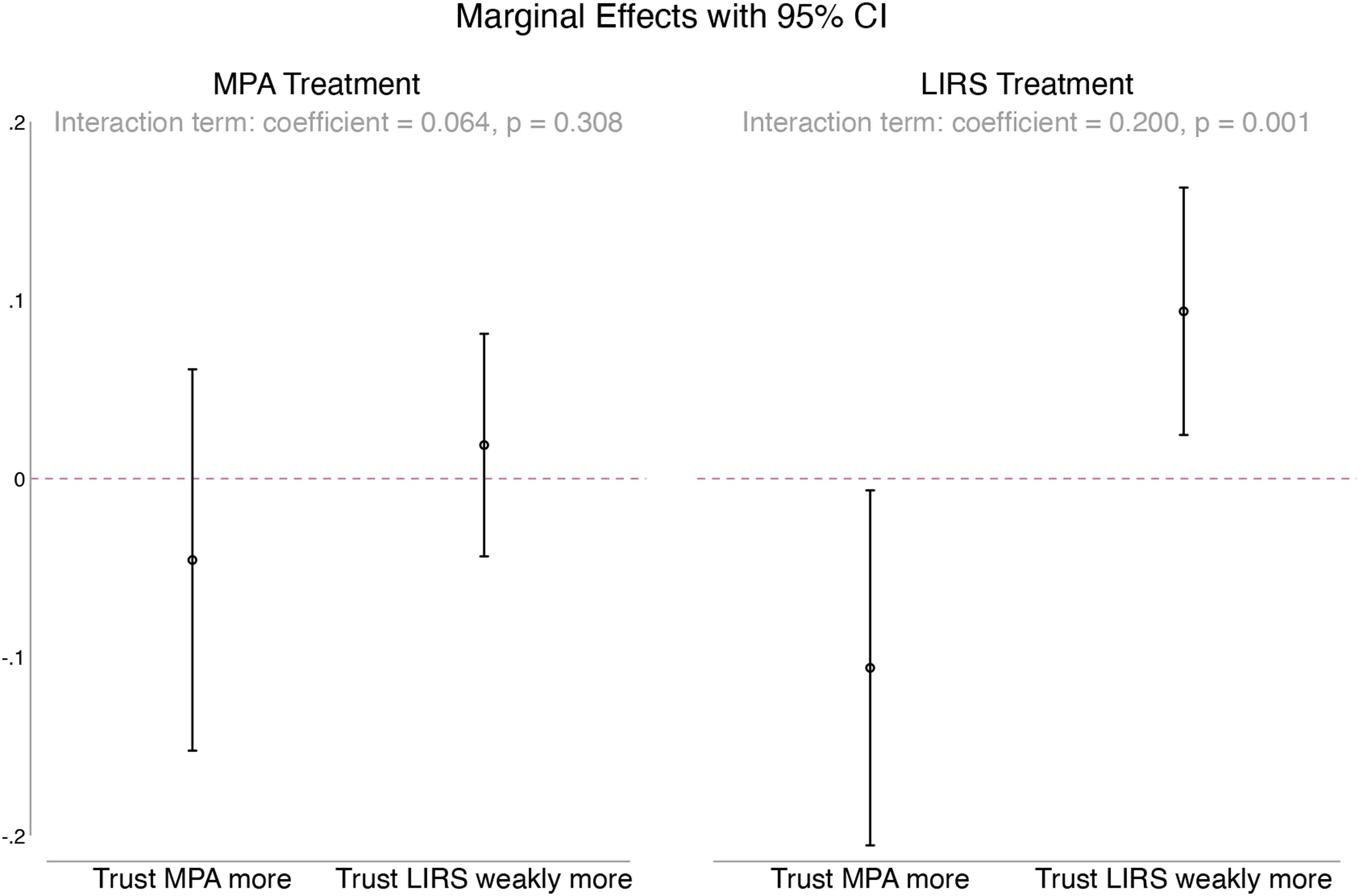

To test Hypothesis 2, which states that trust in the messenger is an important moderator of the effectiveness of treatment, we use an indicator for relative trust as the moderating variable interacted with the Messenger treatment variable. As depicted in Fig. 3, we find that state-delivered appeals have a positive effect on e-TCC registration but only among individuals who trust the LIRS weakly more than their MPA. There is never an effect when the tax appeal is instead delivered by the MPA. Unexpectedly, we also find that among those with greater trust in the marketplace association than in LIRS, the visit from the state agent has a negative effect on the likelihood of e-TCC registration. This finding does not appear to be an artefact of simply weaker trust in the state rather than greater trust in the MPA, since we also find similar heterogeneity of effects when we instead use the moderator of whether a respondent relies on the MPA to solve problems (see Appendix Fig. 9s).

Figure 3. Differential effects of tax appeals by relative trust in messenger.

The regression results reported in Appendix Table 1 show that relative trust does not moderate the effect of the MPA treatment but does moderate the effect of the LIRS treatment. This is indicated by the fact that the coefficient on the interaction term is not different from zero for the MPA treatment, but it is positive and statistically significant for the LIRS treatment. Put simply, those with greater trust in the MPA are no more likely to respond to the MPA-delivered treatment than others.

Moderating Effects of Credibility of the Message

Hypothesis 3 expects past experiences with (a) service delivery and (b) enforcement action by the agent delivering the message to boost appeal credibility and thereby serve as an important moderator of the effectiveness of treatment. Following our pre-analysis plan, we evaluate the moderating effect of both (a) services delivery and (b) enforcement action with respect to the Message treatment. We only expected (a) to moderate the effect of the Public Goods Message and (b) to moderate the effect of the Enforcement message, but we present both here for completeness.

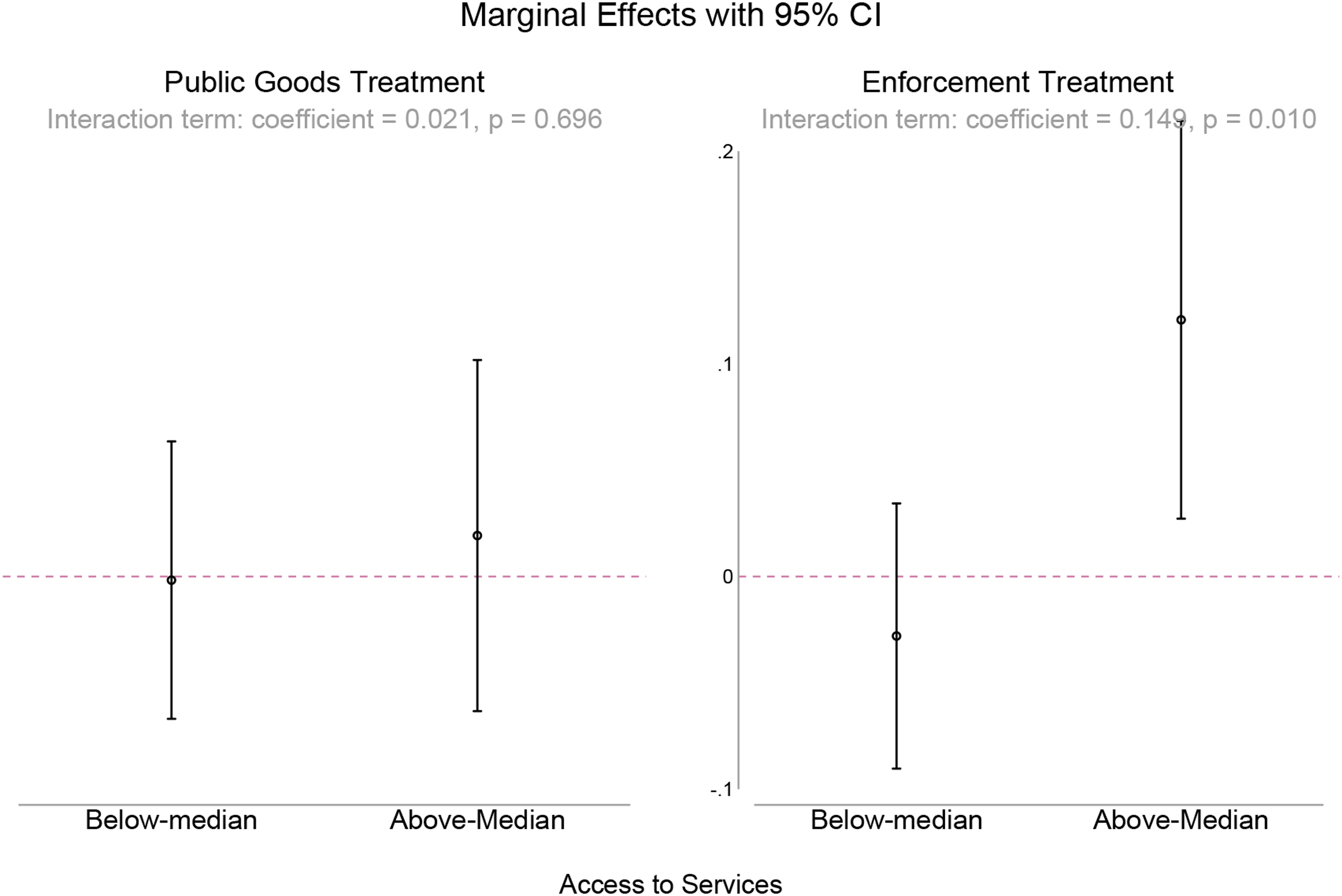

To test H3a, we use the Access to Services Index as the moderating variable for the effect of the Enforcement and Public Goods treatments. For clarity, we create a binary indicator for the moderating variable expressing whether the respondent’s baseline access to services is above or below the median. Figure 4 depicts partial evidence to support H3: greater receipt of public goods moderates the effect of the Enforcement message but not the Public Goods appeal.Footnote 20 This is equally true whether the Enforcement message is delivered by the MPA or LIRS agent. But, as noted above, we expected prior access to public service delivery to moderate the Public Goods Appeal rather than the Enforcement Appeal.

Figure 4. Differential effects of tax messages on e-TCC registration by access to services.

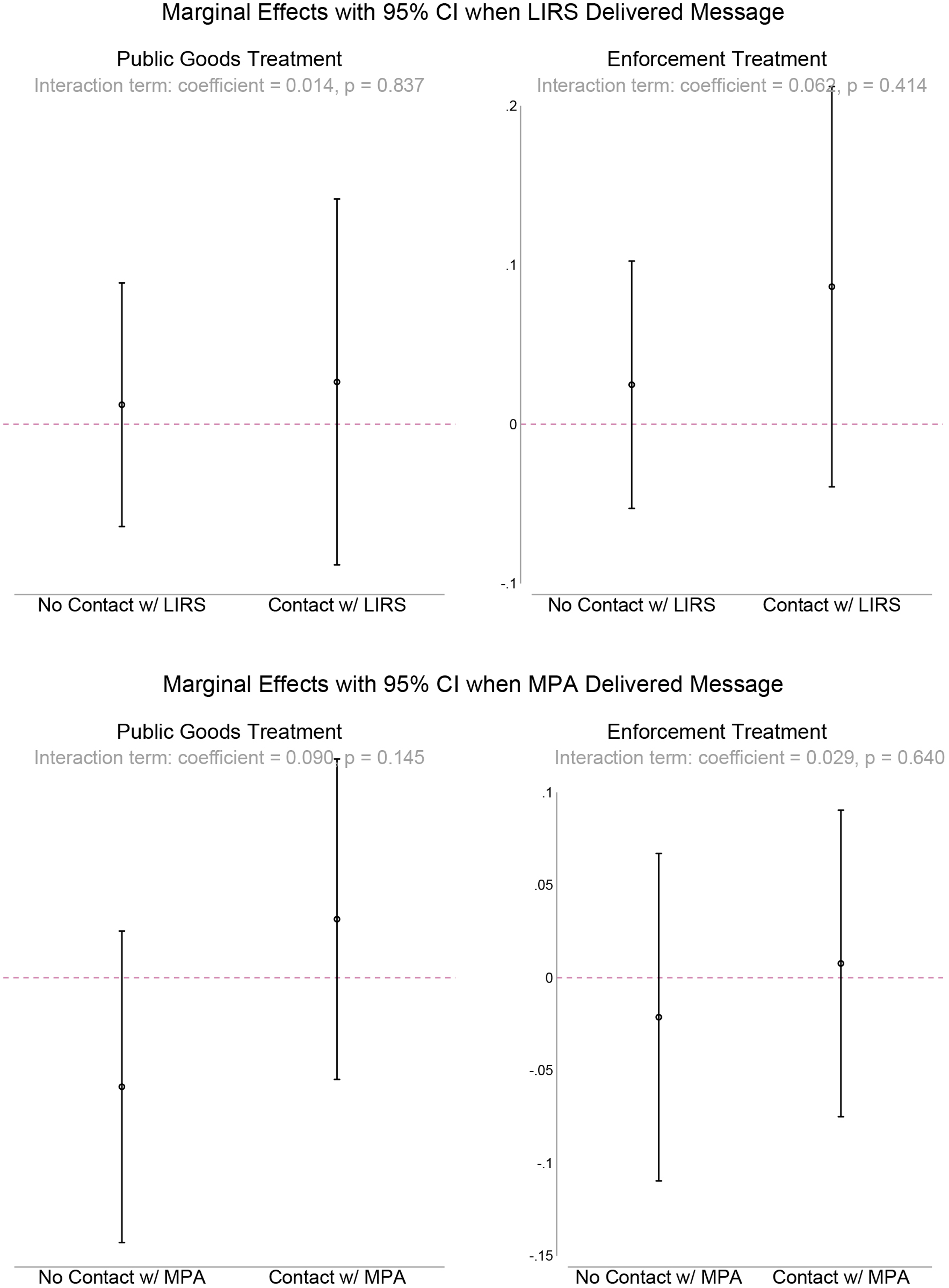

To test H3b, we construct the moderating variable of past experience with enforcement action separately for each messenger as specified in our pre-analysis plan. For the marketplace association, we create an indicator that takes a value of 1 if the respondent reports any past collection of tax by the MPA or reliance on the association to adjudicate disputes. For LIRS, we create an indicator that takes a value of 1 if the respondent reports any past visit or collection of tax by the LIRS. Figure 5 plots the marginal effect of each Message treatment by prior contact with LIRS (in the upper panel) and prior contact with the MPA (in the lower panel). For the moderating effect of prior contact with a particular messenger to make sense, the upper panel excludes the MPA-delivered treatment arm while the lower panel excludes the LIRS-delivered treatment arm from the analysis.

Figure 5. Differential effects of tax messages on e-TCC registration, by prior contact.

To test H3b, we construct the moderating variable of past experience with enforcement action in two ways – both specified in our pre-analysis plan (H2f2). We consider past collection of tax by each agent as one measure of enforcement. A second measure of enforcement differs by actor: for the state agent, we create a binary variable of whether the respondent was visited in the past by an LIRS agent; for the informal agent, we create a binary variable of whether the respondent says they go to the marketplace association to adjudicate disputes. Figure 5 plots predicted probabilities of e-TCC registration by Messenger treatment condition and by each value of the binary moderating variables.Footnote 21

We find no evidence for Hypothesis 3b. Prior contact with the actor delivering the message does not seem to increase Enforcement message credibility, as there is no effect on registration. There is suggestive evidence that prior contact with the MPA increases the credibility of the Public Goods message and thereby increases registration, but this is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

Ethnicity As a Moderator of Tax Appeals

To test H4, we interact both the Message and Messenger treatment variables (in separate models) with an indicator of whether the respondent belongs to the majority Yoruba ethnic group.Footnote 22 We expected that Yoruba respondents would be more responsive to tax appeals. Results illustrated in Fig. 6 not only disconfirm the hypothesis but provide evidence in the opposite direction.Footnote 23 We found that non-Yoruba vendors were the only group to respond positively to appeals. The coefficient on the interaction term with the Public Goods message is statistically significant at 10 per cent.

Figure 6. Differential effects of tax appeals by ethnicity.

Discussion

Overall, we find no evidence in support of our primary pre-registered hypothesis: appeals delivered by social intermediaries do not have a positive effect on formalization and tax compliance among market vendors in Lagos. However, we find partial evidence that tax appeals work conditionally, though in unexpected ways. We find that more trusted agents are more likely to induce compliance, but trust increases responsiveness to tax appeals only for the LIRS agents.Footnote 24 We find that more credible messages are more likely to induce compliance, but only prior access to public services seems to increase credibility. Further, access to public services moderates the effect of the Enforcement message, whereas we expected this conditional effect to be apparent for the Public Goods message.

Our data also generated two clearly unexpected findings. First, while we expected membership in the ethnic majority to moderate treatment in H4, the direction of the estimated effect was contrary to our expectations. Consistent with the political science literature on clientelism and forbearance, we expected members of the political ingroup to view the state and MPAs as favouring Yorubas, to expect preferential access to public goods, and to view enforcement as more likely to target the outgroup. We expected this to increase the effectiveness of appeals via greater messenger trust and message credibility. We found the opposite pattern in our data. LIRS agents (delivering the Public Goods appeal) significantly increased compliance among ethnic minority vendors, with no effect among the Yoruba for any tax appeal, regardless of message framing. Second, we anticipated that those who trusted the agent delivering the message relatively more would respond more positively to treatment. But we did not anticipate the converse relationship we see in Fig. 3. There, those who trust the MPA relatively more than the LIRS were less likely to register for an e-TCC after receiving a tax appeal from an LIRS agent.

The motivation for our project was an expectation that social intermediaries, because of their relatively higher trust and credibility among the population, could be effective partners in state-building in this context. Our data suggest otherwise. Admittedly, the pool of vendors who trusted the MPA more than the state was smaller than we expected. Almost half of the sample reported the same trust level in the LIRS and MPA; only 25 per cent reported a higher level of trust in the MPA, while 13 per cent reported more trust in LIRS. However, as Fig. 4 shows, the tax appeals were still counterproductive among those who trusted the MPA more.

Might the ineffectiveness of intermediary-delivered tax appeals be because taxation is seen as beyond the natural remit of these agents? Lust, for instance, suggests that social institutions are more effective for tasks related to those they performed in the past or those tasks that have a greater organic connection to their existing authority (Lust Reference Lust2022, 26–28). By this metric of ‘domain congruence’, marketplace associations are well-situated to collect tax on behalf of the state. Not only do they engage in informal taxation of their members, but many have collected formal tax and state levies on behalf of local government authorities and LIRS. However, even though marketplace associations have cooperated with state authorities in the past, they have never been viewed as administrative adjutants of the state or as the primary agents of state tax collection. We view the autonomy of the intermediary coupled with domain congruence as advantages that would strengthen these actors’ social influence, rendering our null results more surprising. One explanation could be that individuals did not view tax registration appeals delivered by the MPA on behalf of the state as plausible. As evidence that these appeals were viewed as plausible, even though they did not shift behaviour, we show in Appendix Fig. 8 that vendors receiving the MPA-delivered message expressed increased expectations of punishment for not paying tax.

Might our surprising findings be due to variations in the quality of marketplace associations? Might higher-quality MPAs still make good partners in state-building? To test this, we construct a Marketplace Association Quality Index that comprises whether the respondent believes the MPA is the biggest problem facing the market, is helpful in solving crimes, represents all vendors equally, collects fees vendors can’t avoid paying, and whether the respondent is active in the MPA or would go to the MPA if they had a problem. These items are positively correlated except for the first one, for which we use the inverse. Appendix Fig. 7 rejects the idea that the MPA Appeal works better for respondents who report higher-quality MPAs (this test was not pre-specified).

The responsiveness of ethnic minorities to the LIRS-delivered treatment was also surprising, as we expected that Yorubas’ political control of the state would make invitations to fiscal exchange less attractive to ethnic minorities, perhaps especially when delivered by state agents. Why then do ethnic minorities respond to state-delivered appeals that have no effect on members of the dominant ethnic group? There are several possibilities that might be investigated in future research. First, it may be that ethnic minorities respond to the state treatment out of fear that they would be harshly punished for non-compliance, fears that are not shared by Yoruba vendors. This seems possible, but both Yoruba and non-Yoruba vendors report similar, very low expectations of punishment for tax evasion at baseline. If fear of enforcement motivated minority compliance, we would also expect to see a response to the MPA-delivered treatment, since these institutions have a track record of ‘taxing’ and otherwise treating minority vendors more harshly.

Alternatively, ethnic minorities may view a stronger unmediated relationship with state institutions as potential protection against social institutions that discriminate on the basis of ethnicity. This explanation is consistent with Juul Reference Juul2006, who finds that Fulani pastoralists in Senegal viewed payment of tax as a means to substantiate their citizenship claims and ‘block attempts by local elites to deny them their civil rights’ (839). We find this explanation most compelling and consistent with qualitative evidence gathered as part of this project. For example, in our study context, ethnic minority vendors pay more shop rent, report that they are more heavily ‘taxed’ by MPAs, and complain about other forms of differential treatment by iyalojas and other market leaders. They may be more likely to respond to the LIRS treatment precisely because they see the state agent as a rival to extortionary social institutions or as the lesser of two evils. Minority vendors may, therefore, view the documentation offered by the LIRS agent as relatively more valuable, or they may discount the risk associated with entering into fiscal exchange with the state relative to their counterparts in the majority ethnic group.

Conclusion

The findings presented in this article are relevant to an important new debate about how states and pre-existing social institutions affect one another during state-building. In contrast to recent work that suggests productive complementarity between social institutions and states, we do not find evidence that social intermediaries can be credible partners in state-building, at least when it comes to the central state task of raising revenue. We find that the delivery of tax appeals by trusted social intermediaries on behalf of the state had no impact on citizens’ compliance. This suggests that low-capacity states cannot necessarily ‘piggyback’ on more deeply rooted institutions when attempting to establish fiscal exchange with citizens. Instead, their efforts may be best directed at enhancing citizen trust in state institutions or attempting to displace trust in social intermediaries, since we found that tax appeals were most effective when delivered by the state to those who trusted the state relatively more than they do social intermediaries. Collaboration with non-state actors when it comes to public goods delivery, a focus of much recent work, could work against this aim.

Second, this article presents evidence that past access to services mediates individual responses to tax appeals, though not through the mechanism that is usually stressed in the literature on fiscal exchange. We find that individuals with better access to state-provided services are more likely to respond to tax appeals, but this effect is driven by enforcement messages. We interpret this to suggest that individuals with service access have greater contact with the state and thereby view threats of punishment for tax evasion as more credible than do their less-serviced peers. Finally, we present evidence that individual response to tax appeals is shaped powerfully by that individual’s social position. Our article’s findings about the responsiveness of ethnic out-groups to state-delivered appeals run counter to the conventional wisdom and are suggestive of unexpected constituencies for formal state-building in the Global South.

Overall, our work highlights that theories of fiscal exchange in weak states should consider the role of social intermediaries and other social institutions, including ethnicity. These actors and institutions may impact efforts to establish a fiscal exchange between states and citizens precisely because of the unevenness of their effects across issue areas and citizens. For instance, social intermediaries may be productive state partners in public goods provision, as suggested in past work, but unproductive when it comes to enforcement and extraction.

There are some important considerations that affect the interpretation and generalizability of our findings. Our study was conducted in an urban context where both service provision and the power of social institutions are uneven. Our marketplace associations do not benefit from the very high levels of trust and infrastructural power that are possessed by some rural chiefs, religious authorities, and other social institutions in more homogeneous settings. This improves the generalizability of our findings to urban contexts in the Global South, which are often characterized by social fragmentation and trust deficits, but implications for other contexts should be investigated further. Second, our study’s actors include a relatively capable state and a relatively autonomous social intermediary. In settings where the state is so ineffective as to be non-credible as a service provider or where social institutions are co-opted by the state, we may not expect the same pattern of results to obtain. Finally, though our study finds differential responsiveness to treatment based on ethnic group membership, we think the implications of this finding are broader. In settings where clientelism is common, access to public goods and state institutions is often determined by political or social group belonging, and individuals may engage or distance themselves from important social networks in different ways. We believe greater attention to how social positionality affects tax behaviour is a productive direction for future research on taxation and fiscal exchange.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000255.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/W19IUO.

Acknowledgements

In Lagos, we are grateful for the support and partnership of the Lagos Internal Revenue Service, the Lagos Market Women and Men Association, and the Centre for Public Policy Alternatives. We thank project managers Abiola Oyebanjo and Oluchi Nwachukwu for leading the implementation team. For helpful comments on earlier versions of this article, the authors are grateful to Sachet Bangia, Dan Berliner, Rasmus Broms, Jangai Jap, Austin Jang, David Laitin, René Livas, Vivian Chenxue Lu, Ellen Lust, Nonso Obikili, Laura Paler, Lise Rakner, Kartik Srivastava and to audiences at multiple conferences and at the George Washington University Comparative Politics seminar, the London School of Economics African Political Economy seminar, the Stanford University Political Science seminar, and at Duke University, the University of Gothenburg, and the World Bank.

Financial support

This research was funded under the EGAP Metaketa II on Taxation with support from the UK Department for International Development. We thank the Metaketa leadership and other research teams for their support and feedback.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standard

The project was approved by IRBs at American University (protocols 2018-8, 2018-206, and 2019- 34) and at Texas A&M University (protocol 2018-053). Further details are provided in Appendix 3 of the online supplementary material for the article.