The workhouse was a central feature of Britain's New Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, and discipline and punishment for transgressions were essential to the workhouse regime. Nassau Senior, a member of the Royal Commission whose report resulted in the act, wanted relief to the poor to be given only within “the strict discipline of well-regulated workhouses.”Footnote 1 He saw maintaining discipline as an essential part of enforcing deterrence and efficiently administering a workhouse full of resentful inmates; yet discipline was more problematic than in asylums or prisons, as workhouse populations were constantly changing.Footnote 2 Senior wished to introduce the “workhouse test” as a measure of true destitution and the only means whereby paupers could receive poor relief in a workhouse.Footnote 3 Moreover, workhouses were designed to deter the poor from applying for relief. This was achieved by their prison-like appearance, their location, often on the outskirts of provincial towns, and also by the separation of men, women, and children, the provision of hard work, and a highly regimented daily timetable.Footnote 4 Discipline was essential because of the low ratio of staff to inmates; in Norwich workhouse in 1881, for instance, there were 529 paupers to twenty staff members.Footnote 5

The new act set up the Poor Law Commission, based at Somerset House in London and composed of three men: Thomas Frankland Lewis, George Nicholls, and John George Shaw Lefevre. Although independent of Parliament, it “did not have the power many people assumed.”Footnote 6 Nevertheless, to their opponents, including some Tories, radical defenders of the rights of the poor and the working class, the Poor Law commissioners were the “Tyrants of Somerset House.”Footnote 7 The commission ordered the formation of Poor Law unions—confederations of parishes large enough to support a workhouse. Parishes were grouped into some six hundred unions, and while some of these unions adapted existing workhouses, by 1841 about 320 new buildings had been completed.Footnote 8 The new union workhouses were the most iconic expressions of the change in policy, deliberately imposing structures designed not only to cow those applying at the workhouse gate but also to surveil them once they became inmates.Footnote 9 The assistant Poor Law commissioner E. C. Tufnell commented that workhouses’ “prison-like appearance, and the notion that they are intended to torment the poor, inspires a salutary dread of them.”Footnote 10 Commonly referred to as “bastilles,”Footnote 11 they represented the principle and practice of the strict separation of paupers from the rest of society, as well as from each other.

Little work has been published, however, on the day-to-day attempts to maintain discipline in union workhouses, the many acts of defiance by paupers, and the punishment inflicted upon inmates by workhouse staff.Footnote 12 This internal misbehavior and insubordination of workhouse paupers is the subject of this article, which draws upon a range of union punishment books. Workhouse masters logged instances of breaches in discipline in pre-printed books that recorded the name of the pauper, the offense, the date committed, the punishment inflicted by the master or other official, the opinion of the guardians on this punishment, the punishment ordered by the guardians, date of that punishment, and any notes attached to the case (which might include referrals to local courts and their outcomes). In my research, set within the context of contemporary understandings of discipline and the appropriate response of authorities through punishment, I explored the types of recorded offenses against workhouse rules and the punishments meted out by workhouse masters and other officers and those ordered by the Board of Guardians and local magistrates. Tensions were inherent within the union workhouse, and I assessed the exercise of agency and authority by various residents of the workhouse, the paupers’ chafing at its rules, and the lived experience of all within its walls. Misbehavior by inmates and responses to it as evidenced in the punishment books provided a window into agency and authority.

While there have been studies of the worst behavior—workhouse riots—and the most severe punishment—committals to prisonFootnote 13—the only detailed study of pauper punishment is David Green's on London workhouses. Green draws primarily upon parliamentary returns, the London Times, and the West London Union Board of Guardians minutes,Footnote 14 a different set of sources than I used in my research. Green's study shows that “only a small number of breaches of discipline ended in a prosecution . . . the remainder were dealt with internally . . . [There was] a much larger problem of insubordination in the workhouse reflecting a wider variety of types of misbehavior than just those paraded before the courts.”Footnote 15 Green argues that, although the combined authority of the workhouse master, Board of Guardians, and Poor Law commissioners tried to create “docile bodies,” the “paupers themselves could be feisty” and misbehavior enabled them to challenge workhouse discipline. Inmates had individual as well as group agency; the workhouse was a site of resistance in which they negotiated with workhouse officials over the provision of poor relief.Footnote 16 Green contends that the union workhouse was a “deeply contested institution” and, further, that pauper misbehavior could challenge even “the legitimacy and authority of the poor law itself.”Footnote 17

The spectrum of misbehavior within workhouses is the focus here, in a variety of workhouse settings beyond London. I initially focus on the concept of discipline and its purposes within institutions, and I then turn to the analysis of workhouse offenses and punishment. While I found broad similarity across unions, I also found striking local difference—a high degree of regional disparity in recorded pauper offenses between workhouses and in workhouse punishment policy. In the final section, I consider whether localism was a consequence of welfare policies and practices at the county or the union level by examining two workhouses in each of the counties of Lincolnshire and Norfolk.

Discipline in the Workhouse

Discipline within the workhouse may be understood in two overlapping ways: conceptually and through the definitions of contemporaries. M. A. Crowther has argued that “most obviously, the workhouse was not Victorian at all,” as there is ample evidence of continuity between the old and the new poor laws—in workhouse provision, the internal management of inmates and officials, and the understanding of discipline within the institutions.Footnote 18 Old poor law workhouses established under the Workhouse Test Act of 1723 were also designed to discipline inmates, and this legislation thus “anticipated the new poor law by over 100 years.”Footnote 19 Discipline had been necessary to the good running of old poor law workhouses, and misbehavior was punished with a range of measures, from being reported to the master or the workhouse committee to a pardon or reprimand, the restriction of leave or diet, or discharge to short spells of incarceration in houses of correction.Footnote 20 There were 3,327 workhouses in Britain by the start of the nineteenth century;Footnote 21 the New Poor Law did not necessarily entail an increase in the numbers of people accommodated in workhouses in regions of the country that had previously possessed them.Footnote 22 Nevertheless, with the new union workhouses, the numbers accommodated almost doubled—from an average of 123,004 indoor paupers in 1850 to 215,377 in 1900.Footnote 23 Discipline was an organizing principal of the New Poor Law project. From the late eighteenth century, significant shifts in conceptions of discipline had been increasingly defined by institutions, surveillance, and restriction of liberty, reflecting a change in the wider ethos of criminal justice and punishment.Footnote 24 Between the 1780s and the 1830s, argues V. A. C. Gatrell, “disciplinary responses to the poor and workshy accelerated markedly.”Footnote 25

Discipline, despite its centrality in policy, was not articulated in relation to punishment in the Poor Law Report of 1834. Instead, somewhat surprisingly, it was associated with a “well-regulated workhouse” and the classification of the indoor poor and the provision of work to prevent the “mischief [that] arises more from the bad example of the few, than from the many.”Footnote 26 The commissioners were critical of the general mixed workhouses under the old poor law but praised those like that at Southwell (one of the workhouses in the study) that categorized their poor according to an “Anti-Pauper System” set up in 1824.Footnote 27 One of its instigators, the Rev. John T. Becher, stated, “The whole System is conducted upon the Principles of salutary Restraint and strict Discipline,” based upon the classification and separation of paupers.Footnote 28 This concept greatly influenced the authors of the Poor Law Report. Its appendices indicated that “a strict system of discipline” for the young and able-bodied must be combined with “hard work, low diet, and restricted liberty.”Footnote 29

The resulting Poor Law Amendment Act stated “Parties wilfully neglecting or disobeying [workhouse] Rules, Orders, or Regulations” were “liable to such Penalties and Punishments.”Footnote 30 The term regulation was used primarily to refer, again, to the provision of irksome work for the adult able-bodied, classification between the deserving and the indolent, and restrictions on alcohol and tobacco that, it was claimed, were “intolerable to the indolent and disorderly.” The “regularity and discipline” provided in the workhouse would, somewhat paradoxically, “render the workhouse a place of comparable comfort . . . to the aged, the feeble and other proper objects of relief,” who also had to be appropriately accommodated.Footnote 31 A well-regulated workhouse classified and separated the indoor poor as an essential aspect of discipline.

Work remained central to the disciplining and reforming of laboring bodies, reflecting considerable continuity in policy from the Elizabethan poor laws and punishment for the poor idle and disorderly in houses of correction.Footnote 32 The amount of work required of workhouse inmates was designed to be less than that required of prisoners. However, paupers objected to undertaking the same labor; oakum picking, for example, was viewed as “felons’ work.”Footnote 33 As in the prison and the wider the philanthropic culture, the notion of discipline shifted, now understood as a means of correcting and reforming behavior. Under the new system of union workhouses and the new prisons, the working classes would become “accustomed to hard work, instead of idleness.”Footnote 34 In the union workhouses, deterrence and discipline were ensured by classification and segregation, thereby separating husbands, wives, and their children, and by the provision of a monotonous diet, a daily routine punctuated by bells for rising, eating, working, bedtime, and religious instruction. From the 1830s, the tone of the regulation and control of daily life within workhouses—and thus its discipline—took on a more moral, religious flavor.Footnote 35

Specific workhouse rules around discipline and related punishment were set out in detail in the First Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners of 1835.Footnote 36 These rules still allowed for considerable autonomy by the local Board of Guardians, and so the Poor Law Commission attempted in 1841 to impose a uniform policy.Footnote 37 Offenses could be classified as “disorderly” or “refractory.” Disorderly behavior included relatively trivial offenses such as swearing, making a noise, playing card games, disobeying orders, or refusing to work; punishment was a reduced diet, such as just bread or potatoes, and the withholding of “luxuries” like butter or tea. Refractory conduct included any disorderly offense repeated within a week, as well as more serious behaviors, such as reviling a workhouse staff member, damage to workhouse property, spoiling provisions, drunkenness, and assault. Such acts were punishable with confinement for up to twenty-four hours and alteration of diet. Serious and persistent offenders could be prosecuted, and magistrates could sentence paupers to up to twenty-one days’ hard labor.Footnote 38

The law specified that the regulations were to be publicized widely and that they were to be enforced by inspections.Footnote 39 It is clear from the correspondence of Sir John Walsham, an assistant Poor Law commissioner, that the rules had to be displayed in the workhouse: when he visited Mitford and Launditch workhouse (another of the workhouses in the study) in Norfolk on 14 June 1847 he commented, “The Commission are concerned that the regulations for pauper punishment are not displayed in the appropriate places in the workhouse.”Footnote 40 Masters, matrons, and guardians had considerable power to punish inmates but only within the terms of their authority within the rules; indeed, the 1834 act anticipated the risk of abuse and so specified restrictions to their power.Footnote 41 Workhouse scandals reveal instances when officials overreached their authority and when they were upbraided by the Poor Law Commission or Poor Law Board, assistant commissioners, or visiting committees.Footnote 42 At times, the press scrutinized poor practices or abuses.Footnote 43 Moreover, magistrates might sympathize with the poor and could undermine workhouse officials by giving lenient sentences or discharging cases.Footnote 44

Michel Foucault's Discipline and Punish offers a powerful conceptual critique of the role of discipline, punishment, and institutions in modernity. Workhouses in some respects resemble the prisons of Foucault's study. They shared many aspects of the design of Bentham's “Panopticon” prison; activities were scheduled, and work was intended to make the body ready for utility. The classification of paupers was arranged spatially, and authorities sought uniformity of punishment for infractions of workhouse rules.Footnote 45 Paupers certainly recognized the “bastille” quality of the buildings: “The very vastness of [the workhouse] chilled us,” Charles Shaw recalled in his autobiography. His description evokes the prison: “Doors were unlocked by keys belonging to bunches, and the sound of keys and locks and bars, and doors banging, froze the blood within us.” So, too, does James Reynolds Withers's poem in a letter to his sister: “I sometimes look at the bit of blue sky / High over my head, with a tear in my eye, / Surrounded by walls that are too high to climb, / Confin'd like a felon without any crime.”Footnote 46 Workhouse punishment, like that in prisons, was no longer corporal (except for schoolboys) but based on incarceration, surveillance, and reform.Footnote 47 Moreover, some workhouse inmates found themselves propelled for their behavior from the workhouse to prison.

However, while the architects of the New Poor Law might have designed the workhouse as a “carceral system” to “neutralise . . . anti-social instincts,” such a view does not take account of the power of resistance of those submitted to regimes of discipline.Footnote 48 The historian must also seek to recover individual agency and the “semi-autonomous culture of the poor.”Footnote 49 Poor behavior in workhouses can be understood as “weapons of the weak,” powerfully disruptive actions that frustrated discourses of discipline.Footnote 50 The understandings of repression and resistance put forward by James C. Scott, in terms such as “exchange of small arms fire” and “a small skirmish,” provide a model within which to contextualize social relations in the workhouse.Footnote 51 The interactions between workhouse officials and inmates also offer a window into what Michel de Certeau characterizes as the “strategies and tactics” of “the practice everyday life.”Footnote 52 The punishment books certainly suggest that workhouse inmates took advantages of “opportunities” and “cracks” in the “surveillance of the proprietary powers.”Footnote 53 Inmates not only expressed their agency by their actions within the house but also projected their complaints outside it. Steven King argues that under the New Poor Law, inmates were never “merely subject to the regimes of the workhouse”: “Individually and collectively, inmates protested when they or their friends and peers experienced medical neglect, when diet or clothing was inadequate, when people were disciplined unjustly and where relief decisions were taken or not taken by staff and workhouse masters and mistresses.”Footnote 54 This dissent was over and above the anti-New Poor Law movement and local protests.Footnote 55 Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker have recently gone further than has de Certeau: “It is the character of tactics, despite the frequent absence of an explicit collective voice, that turns individual actions . . . into a collective, at times even strategic, engagement with the social system.”Footnote 56 The argument here is that, even though power was far from equally distributed within workhouse walls, paupers displayed agency by employing “blow by blow” tactics that could be strategic.

Offenses and Punishment in the Workhouse

I studied evidence from eleven English workhouses over a wide range of locations to reflect the broad range of experience of provincial workhouse life.Footnote 57 Together, these workhouses cover the northwest (Cockermouth, Cumberland), the northeast (Patrington, East Riding of Yorkshire), the Midlands (Ampthill, Bedfordshire, Foleshill, Warwickshire, Sleaford and Spalding, Lincolnshire, and Southwell, Nottinghamshire), East Anglia (Mitford and Launditch and Norwich, Norfolk), the south (Petworth, Sussex), and the southwest (Beaminster, Dorset). The smallest workhouse was that of Petworth, with just twenty-five inmates in 1881, and the largest was Norwich, with a population of 529 at one time. (Table 1 provides a comparative profile of the eleven workhouses.) I chose two workhouses in each of Lincolnshire and Norfolk to allow comparison both within counties and between them. I supplement this largely statistical evidence with “voices from the workhouse”—accounts from those who were once inmates and workhouse staff.Footnote 58

Table 1 Profiles of Eleven Workhouses

The keeping of punishment books, separate from reporting punishments to the Board of Guardians, was not compulsory, perhaps explaining their poor survival.Footnote 59 Not only do relatively few survive, but they must be used with caution. Where such books were kept, workhouse masters were supposed to enter into them all workhouse offenses. Yet the diary of Benjamin Woodcock, master of the Barnet Workhouse, reveals that this was not always done. Woodcock merely “talked” to some workhouse boys who destroyed a garden hedge, and when Thomas Bourne returned late from church worse for drink, this “being his first—offence since his admission,” and considering that he “Acknowledged his Transgression [and] went quiet & orderly to Bed,” Woodcock chose not to punish him.Footnote 60 Instances of informal punishment likely also went unrecorded, such as the “pulling or ‘clipping’ of [children's] ears,” which, argues Lesley Hulonce, “survived long into the twentieth century.”Footnote 61 Moreover, workhouse scandals make it clear that not all punishments meted out were recorded and some were explicitly against workhouse rules.Footnote 62 Thus, these books document only recorded offenses, not necessarily the sum total of offenses.

Punishment books include the date of the recorded offense, the name of the inmate, the nature of the offense, the punishment inflicted by the master or other officer or that ordered by the Board of Guardians, the opinion of the guardians, and any observations. If paupers were sent before local magistrates and sentenced to prison, this, too, was entered. Many punishment books show more offenses than cases, as an entry in the book may record more than one offense; the eleven books record 3,987 cases reflecting 5,214 offenses (an average of 1.3 offenses per case). This was also the situation for punishments (numbering 4,390); due to repeat offenders, there were many more offenses than there were offenders. Across all eleven workhouses studied and all dates, I found the average was 1.5 cases per offender, but in Cockermouth, for instance, the name of Elizabeth Fawcett was listed twenty-eight times.

Recorded offenders were disproportionately male: I found that at least 60 percent of offenses were committed by boys and men; in some places, the figure was 81 percent (table 1). The perception of offending was undoubtedly gendered, and male misbehavior, seen as more threatening, appears more frequently in the punishments books. The masculinization of recorded offenses was the case for all the workhouses except Cockermouth (where only 22 percent of cases were committed by males, yet 55 percent of inmates were male in 1881), and in Patrington (where males were responsible for 43 percent of offenses but were 54 percent of inmates in 1881).Footnote 63 Historians of crime have shown that men were far more likely to be prosecuted and imprisoned.Footnote 64 Men reacted to the undermining of their domestic authority and social standing with flared tempers or worse.

As several scholars have found, offending fell into a clear seasonal pattern: January showed more than double the number of recorded offenses of those in June, reflecting increasing resort to the workhouse in the winter months.Footnote 65 This seasonal pattern was not evident in London, where employment did not wax and wane according to the time of year.Footnote 66 In analyzing the punishment books of the workhouses in my study, I found that the number of cases per year fluctuated between twenty and fifty, with the occasional peaks of 177 cases in Cockermouth in 1865 and 193 in Norwich in both 1862 and 1874. I also found that after the late 1870s, the number of recorded cases across all workhouses fell to the end of the Victorian period.

I analyzed the offenses that appear in the selected punishment books according to the 1841 classification, although they did not always fit neatly into them. I found that 62 percent of all recorded offenses across the workhouses were disorderly, and 22 percent were refractory. The remaining 16 percent were not accommodated by these schema. A wide range of other acts were neither specifically disorderly nor refractory, including cruelty to children or desertion of family members, theft, tobacco-related offenses, and truancy. Thus, almost two-thirds of bad behavior incidents were not serious or not repeated within a week. However, the consequences of refractory actions could be far more severe: in 9.7 percent of cases, paupers were imprisoned. Unlike at the national level, workhouse officers did not resort increasingly to the courts; such recourse fluctuated between no cases in a given year (1856) and forty-three (1848), with no upward trend.Footnote 67 (Of course, 1848 was a year dominated with concerns with public order, embodied in the Chartist petition, and revolutions in Europe.Footnote 68) In my analysis of the eleven workhouses, I found that magistrates ordered spells in prison of up to twenty-one days in most cases: seven days (13 percent), fourteen days (19 percent) and twenty-one days (28 percent), but, in a significant minority of cases, they actually sentenced beyond the twenty-one days given in the regulations, with 20 percent imprisoned for one month and one-fifth up to three months. Imprisonment with hard labor was specified for two-fifths of paupers. In rare instances, the outcome was far more severe: for instance, in December 1845, William Mills was transported from Beaminster union workhouse for seven years for “robbing in the school room & desertion with clothing.”Footnote 69

The workhouse punishment books reveal simmering underlying tensions, with different motives, perceptions, and expectations between and within each of the groups in the hierarchy of authority: inmates, workhouse staff (master and matron, chaplain, schoolmaster and schoolmistress, medical officer, taskmaster, and any domestic staff), Board of Guardians, Poor Law inspectors, magistrates, and the Poor Law Commission (later the Poor Law Board).

The working classes found the separation of husbands, wives, and children particularly cruel. Indeed, there were protests against it in Spalding Union in 1836.Footnote 70 Charles Shaw recalled that upon entering Chell workhouse (near Stoke-on-Trent) as a child, his family was “parted amid bitter cries, the young ones being taken one way and the parents (separated too) taken as well to different regions” of the building.Footnote 71 Megan Doolittle argues that the workhouse “had particularly devastating impacts on masculine identities,” since the splitting-up of families deprived men of “their position as the head of their household and their standing in the world as providers and protectors.”Footnote 72 Families were reunited briefly on Sunday afternoons, and children recalled the heavy emotional toll of these reunions. Charlie Chaplin recollected, “How well I remember the poignant sadness of that first visiting day: the shock of seeing Mother enter the visiting-room garbed in workhouse clothes. How forlorn and embarrassed she looked! In one week she had aged and grown thin, but her face lit up when she saw us.”Footnote 73 The fracturing of familial relationships according to the classification scheme of the commissioners was no doubt a motivating factor in misbehaviors.

In contrast, masters found themselves caught between surly resentful paupers and the local ratepayers sitting as guardians, who, in turn, were directed by the commissioners. Charles Shaw cannily recognized in hindsight that the master had to play a part in order to keep discipline: “[W]hen the New Poor Laws meant making a workhouse a dread and a horror to be avoided, he was perhaps only acting the part he felt to be due to his office.”Footnote 74 While this “governor” could be “the Bastile (sic) in its most repulsive embodiment,” Benjamin Woodcock, master at Barnet, was far from the bullying stereotype of Mr. Bumble of Oliver Twist.Footnote 75 There might also be strain between the master and guardians, as shown when the master of Poplar workhouse attempted to bar Will Crooks, the first working-class guardian in the union (who had been in the workhouse as a child) from entering the premises.Footnote 76 Chaplains could be pompous and boring but might also bring consolation to inmates, and such acts of kindness would not be evident in the punishment books.Footnote 77 It might have been a thankless job for the taskmaster to extract work from the able-bodied, but taskmasters, too, might have behaved badly. Inmates in Stepney workhouse in 1850, for instance, wrote to the Poor Law Board to report the drunkenness, brutality, and bad language of the taskmaster, who called them “old buggers” and “old sods.”Footnote 78 Bentham recognized that the custodians of the institution also needed watching.Footnote 79 Thus, keeping the peace in the workhouse was fraught, particularly given that children and the elderly made up large sections of workhouse populations and officials had to provide appropriate care for these groups alongside discipline for the able-bodied. Workhouses, as Susannah Ottaway argues, “featured a complex mix of caring and disciplinary imperatives.”Footnote 80

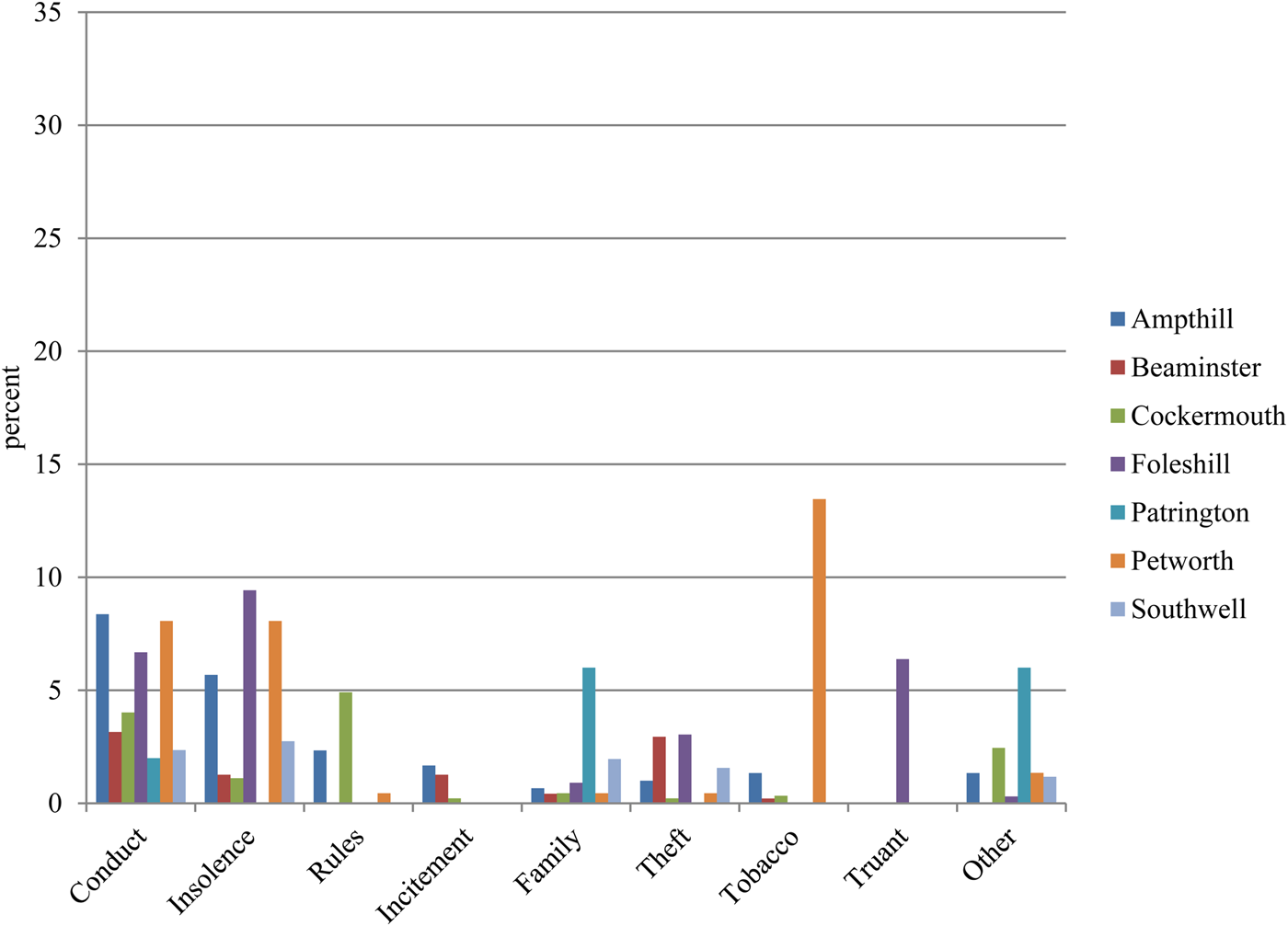

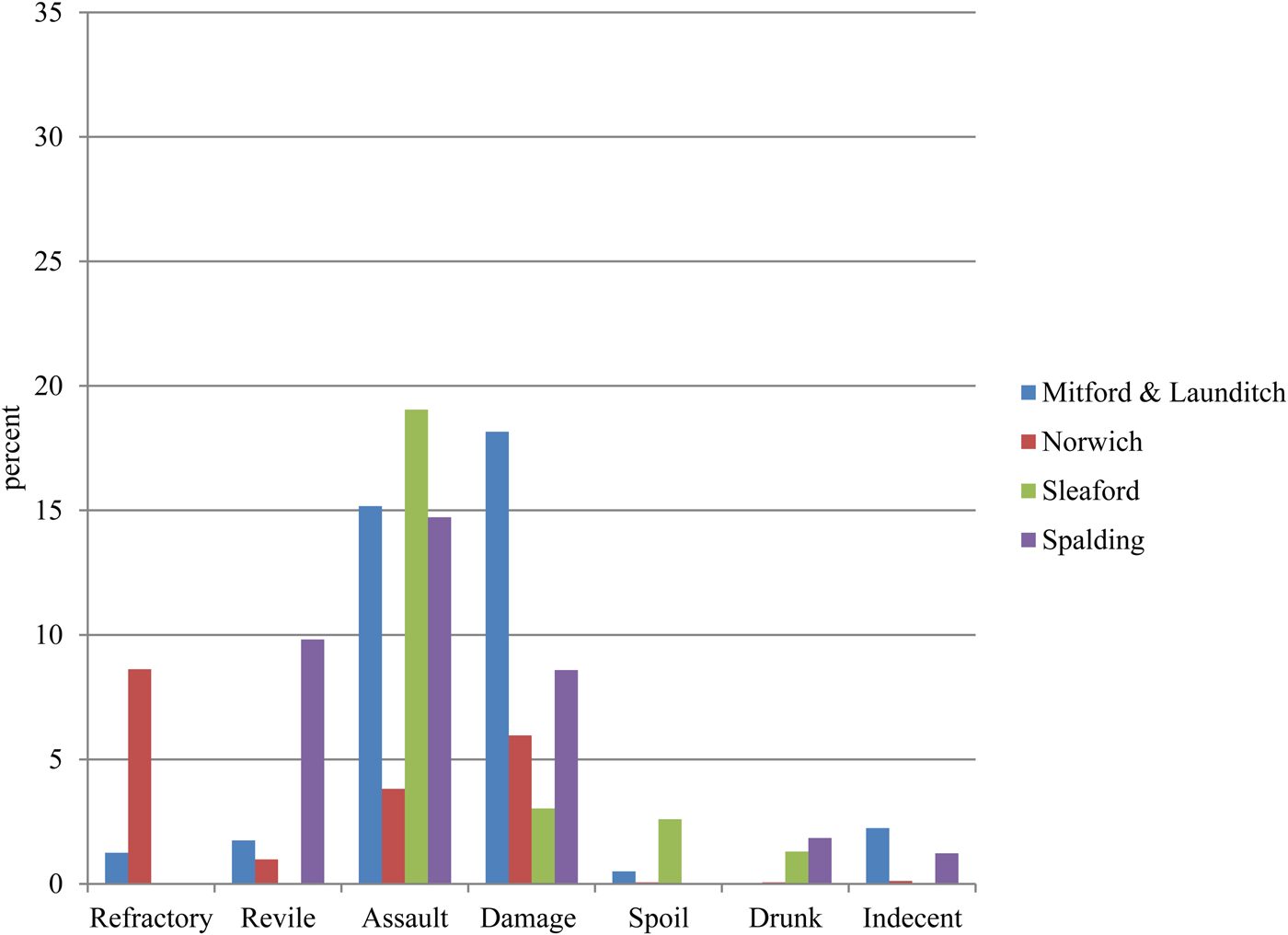

The recorded offenses of indoor paupers varied greatly from workhouse to workhouse and reveal a repertoire of “tactics” amounting to local cultures of resistance (see below figures 1–3 and 6–8). Paupers chafed against the restrictions of indoor life. They resented, for instance, the regulation to keep silent at mealtimes, so at variance with working-class custom. Benjamin Mackharness was recorded as “making a noise in the dining hall when silence was ordered to be kept,”Footnote 81 while James Webb had been “disturbing the quiet of the house by singing songs in the day room.”Footnote 82 Webb also sought to turn individual into collective action since he was “endeavouring to excite the other inmates to acts of insubordination.”Footnote 83 Other restrictions of workhouse life included strictures on smoking and drinking, which were fundamental to working-class male sociability. Men rebelled in Petworth, in particular, with 13.5 percent of offenses being tobacco-related. James Reynolds Withers bemoaned the lack of alcohol in the workhouse in his verse: “I'll drink your health with a tin of cold water: / Of course, we've no wine, no porter nor beer, / So you see that we all are teetotallers here.”Footnote 84 Men made the most of any temporary leaves of absence from the workhouse to drink, with a further 9 percent of offenses in Petworth being for drunkenness. On 7 June 1862, Robert Mallett, an inmate of Beaminster workhouse, “Had leave from the Board for One day Left the House on Saturday morning & did not return until Sunday morning and then in a Beastly state of Drunkenness.”Footnote 85 Religion might also be a flashpoint. In Cockermouth, for instance, women in particular objected to the imposition of compulsory prayers; such disturbances accounted for one-fifth of all offenses, with 86.1 percent of offenders being female. Church attendance in Cumberland was very low across all denominations and was some of the lowest in England.Footnote 86 Even if workhouse routine was designed as a “temporal means of discipline,”Footnote 87 paupers exploited available “cracks” to protest against it.Footnote 88

Figure 1 Disorderly Offenses, Seven Workhouses

Figure 2 Refractory Offenses, Seven Workhouses

Figure 3 Other Offenses, Seven Workhouses

Figure 4 Graffiti game on wall, Southwell workhouse yard. Photo © Samantha Williams.

Figure 5 Punishments, Seven Workhouses

Figure 6 Disorderly Offenses, Four Workhouses

Figure 7 Refractory Offenses, Four Workhouses

Figure 8 Other Offenses, Four Workhouses

Figure 9 Punishments, Four Workhouses

Workhouse staff faced a battery of abuse from inmates. Outbursts of “obscene or profane language” were the easiest form of resistance and regularly upset workhouse life.Footnote 89 John Pearson, aged forty, swore at Ampthill's porter, and two days later was using bad language to the barber.Footnote 90 Bad language was three times more common in Ampthill (15.1 percent) than in Patrington (4 percent), and in Spalding it was even lower (2.8 percent). Assault was the most serious refractory offense; inmates assaulted masters, matrons, schoolmasters, porters, and caretakers. Henry Jarvis was punished for “assaulting the lab[or] master & throwing an iron scraper at him,”Footnote 91 while Mary Scarborough violently assaulted the Sleaford workhouse matron and tore off her cap.Footnote 92 Such wrongdoing made up a significant proportion of offenses in some workhouses: assault accounted for almost one-fifth of offenses in Southwell and Sleaford and more than 15 percent in Patrington and in Mitford and Launditch. That paupers felt able to resort to assault points to the limits of the disciplinary regime of the workhouse and, at times, their very real agency within it.

Frustration at institutional life was expressed in damaging workhouse doors and smashing windows, breaking kitchen utensils and cupboards, or tearing union clothes. In Beaminster, such damage accounted for almost 11 percent of cases. Breaking windows was a particular favorite of refractory paupers (one-third of all damage offenses), since it was an easy and visible way to protest; Elizabath Thursby of Cockermouth broke “23 panes of glass in the receiving ward.”Footnote 93 Digby suggests that vagrants in Norfolk purposely broke windows in an attempt to be sent to prison where, she argues, there was a “superior diet . . . light labour and a more spacious environment.”Footnote 94 William Cummings, also of Cockermouth, set fire to the straw loft and John Castlehow burned the outhouse,Footnote 95 while Thomas Bone willfully broke the Mitford and Laundich workhouse doorbell.Footnote 96 In 1876, William Roberts, in Sleaford workhouse, was accused of damaging workhouse property: he broke open the field gate and made away with the lock and chain, he broke open the door of the work cell, and scaled the wall of the yard, with the local policeman returning him.Footnote 97 Other paupers targeted their sleeping quarters; George You smashed up his chamber,Footnote 98 while Emily Rix threw her bedclothes out of the Norwich workhouse window.Footnote 99 No less than sixteen naughty schoolboys damaged the workhouse garden when returning from school to Mitford and Launditch workhouse,Footnote 100 and in Spalding workhouse, Alfred Stanger (aged twelve) and Frederick Thompson (aged fifteen), were recorded as “climbing over the roof of the schoolroom, going to the town & buying a pennyworth of gunpowder and a half pennyworth of lucifer matches, and on going to bed setting fire to the gunpowder on the landing adjoining their bedroom.”Footnote 101 Despite a “good flogging,” two weeks later, Alfred was again “climbing over the roof of the schoolroom and going into the womens day drying ground without permission,” this time with William Bannister (aged thirteen).Footnote 102

Defiance manifested in damage to workhouse clothing accounted for 55 percent of offenses of damage. John Cousins, in Beaminster workhouse, was accused of “wilfully destroying a shirt and trowsers this being a very frequent offence.”Footnote 103 Richmond has recently shown that “workhouse dress” was rarely an actual uniform but that the economies of scale in provision of these items meant that in practice it amounted to one. Those entering the house were clothed from the stock of available clothing, which meant that it rarely fitted.Footnote 104 In Norfolk, male inmates were dressed in a Duffield jacket, drabbett trousers, a waistcoat, cotton shirt, and neckerchief; women wore stays, a flannel or linsey petticoat, striped serge or grosgrain or union chambrey gown, hessian apron, checked neckerchief, camlet jacket or shawl, grey stockings, and a white calico or cambric hat; children were dressed in striped or checked gowns, with aprons for the girls and jackets, and trousers of a coarse cloth with a spotted neckerchief for the boys. Men and children might have their hair roughly cut.Footnote 105 John Castle recalled workhouse clothing as “the regimentals of the Union.”Footnote 106 Charles Shaw wrote that when he entered the workhouse at age ten he was “roughly disrobed, roughly and coldly washed, and roughly attired in rough clothes.”Footnote 107 At Kent workhouse, clothing for boys was badly torn and stained, and such poor attire must have resonated negatively with the working classes who expressed the unacceptability of their poverty in pauper letters through the motif of the ragged child.Footnote 108 Paupers were expected to wear such clothing even when leaving the workhouse on an errand or to attend church or school.Footnote 109 One female workhouse visitor commented that children's uniforms had “brought real misery.”Footnote 110 When paupers absconded, they were of course wearing workhouse clothing and thereby compounded one offense with another one; correspondence with the Poor Law Commission suggests that some contemporaries argued a specific punishment for this should be devised.Footnote 111 When John Osborn, Edward Southeron, and William Warren were give three months in Ipswich prison for absconding with workhouse clothing, a petition for clemency was made due to their youth and a fear that severe punishment might have a bad effect.Footnote 112

Vagrants were not clothed in workhouse attire, but tore their own clothes nonetheless. The punishment books inconsistently register whether paupers were vagrants, but tramping men and women had another motive to tear their own clothes. Seth Koven argues that vagrants’ “‘tearing’ or ‘breaking’ up their clothes was at once a pathetic gesture of defiance and a practical response to their situation,” since it “allowed inmates to vent outrage over their treatment and forced officials to provide them with a new and valuable suit of clothes.”Footnote 113 Workhouse masters sought to prevent this abuse by issuing poor-quality clothing to tramps.Footnote 114 This is one instance where the tactics of vagrants could be seen as strategic.

Bad behavior was not solely directed at officials, and staff frequently found themselves keeping the peace between inmates in ways unanticipated by the Poor Law Commission. The oppressive workhouse environment divided paupers as much as it united them and fractured the efficacy of their agency. In Norwich, the workhouse master recorded that William Philo was “persisting in disturbing the quiet of the wards by swearing, shouting & making use of filthy & disgusting language, refusing to obey the warder or keeping his proper room.”Footnote 115 Sarah Godson drove workhouse inmates mad by “singing songs nearly the whole of the day,”Footnote 116 and Mary Moss and Mary Jane Graham in CockermouthFootnote 117 and James Platten, Richard Leeds, and Robert Buckenham in NorwichFootnote 118 were all punished for singing filthy songs. The line between resistance to authority and disturbing other inmates was a thin one: the workhouse master of Norwich believed that some inmates’ bad behavior was much to the annoyance of others and regularly recorded it as such (9 percent of cases), as when Hannah Harvey, Martha Chatten, and Esther Betts were “persisting in being disorderly and annoying the other inmates. Also making use of very foul language.”Footnote 119 Authorities might also have to intervene in cases of theft, as when Rebecca Cason was recorded as “stealing cake & oranges from Emma Saw,”Footnote 120 or abuse to children or parents. In her poem about the workhouse, Ann Candler described fellow inmates as “the dregs of human kind” whose “rude behaviour gives offence.”Footnote 121

It is no surprise, then, that fighting broke out between paupers. Age did not prevent Edward Thompson, seventy-seven years old, and Jeremiah Cross, aged sixty-eight, from assaulting one another in Spalding workhouse.Footnote 122 Women also struck one another; Margaret Topley and Jane McCartney were found “fighting on women's landing (Sunday)” in Cockermouth workhouse.Footnote 123 Those least able to defend themselves might also be targeted: George Greaves was accused of “striking Geo Adcock an idiot aged 55 blacking his eye and cutting his cheek,”Footnote 124 while Susan Gulliver was accused of “striking an idiot (Ht Tyson) in a cruel manner, her eye and face discoloured very much.”Footnote 125 Such examples highlight the real problems faced by workhouse staff in combining the caring and disciplinary features of the workhouse.

Being set to work put the “work” in “workhouse.” Paupers in union workhouses pumped water, ground corn at a hand-mill, broke stone, grew cereals or vegetables in the workhouse garden, performed household tasks, picked oakum, crushed bone, did tailoring and sewing, and managed the boiler house.Footnote 126 My calculations reveal that refusal to work was one of the most common recorded offenses, particularly so in Ampthill (34 percent) and Beaminster (30 percent), while it accounted for more than one-tenth of offenses in Cockermouth, Petworth, Mitford and Launditch, Norwich, Sleaford, and Spalding. William Everitt committed the offense of “not picking 3lbs of oakum a day which is the quantity ordered by the board for each ablebodied man” in Spalding workhouse in September 1862.Footnote 127 Susan Gilliver, at Ampthill, was recorded as “refusing to do any kind of work and screaming murder the whole morning, threatening to smash the windows and after throwing two stone[s] through the kitchen windows got over the wall and absconded with the House clothing.”Footnote 128 The master at Beaminister workhouse had a particular problem with “idleness,” a word I found used in 12 percent of offenses. Samuel Dunn's name appeared seventeen times in the pauper offense book, mostly for being idle, refusing to work, or leaving his work. In order to resist the imposition of workhouse work, some paupers destroyed material or equipment. Ruth Dickinson was punished for “destroying oakum.”Footnote 129 Ingeniously, Henry Howes, George Homes, Richard Howard, and Michael Creed of Norwich workhouse broke open the door of the pump and took off the gear wheels so that they could not be set to work on the pump.Footnote 130

The setting of the poor to such tasks went against the cultural notions of the right of the poor to fair work and fair pay. John Rutherford's recollection of Poplar Union workhouse in 1885 provides an insight into the ways in which the poor might subvert the expectations of the authorities. Set to work stripping hemp from telegraph wires, he noted, “There was no hurry over the job—very much the contrary—but plenty of chatter and larking when the taskmaster was out of sight.” When transferred to that staple of workhouse work, oakum picking, Rutherford observed that “only a few” ever completed their allocation, and that “no young man that ever I saw completed his four pounds.”Footnote 131 Decisions to deliberately work slowly highlight pauper agency, showing that work was not so exhausting that it prevented transgressions, and that inmates could turn it into a time of camaraderie.Footnote 132 However, workhouse officials had ways of subverting such subversion. Richard Ellis, master of Abingdon Union workhouse, told the Poor Law Board that labor in the workhouse garden was too good for able-bodied men: “I make it a matter of favour to employ them there; and for those who do not work well while there, some sort of employment within the house is found.” Instead, he let the old men and boys occasionally work in the garden, “which makes them cheerful and keeps them in good health.”Footnote 133

Workhouse walls were far more porous than the ideal of separating paupers from one another and the outside world by the “spatial means of discipline” outlined by Foucault: sectioned-off staircases, day rooms, dormitories, and high surrounding walls.Footnote 134 Many inmates avoided the due process of asking the master for permission to leave and collecting one's own clothes, instead absconding beyond the boundaries of the workhouse; this accounted for 32 percent of offenses in Patrington and 16.9 percent in Beaminster, but just 0.7 percent of offenses in Cockermouth. In Southwell, almost 17 percent of offenses related to absconding, despite the institution's infamous and influential design. George Nicholls, a retired officer of the East India Company's merchant marine and Poor Law Commissioner, when overseer of Southwell workhouse, had ordered in 1821 that the workhouse be “enclosed by walls sufficiently high to prevent persons entering or leaving the promises without permission.”Footnote 135 No doubt some, following an altercation, impetuously shinnied over the external wall; however, refusal to engage with the proper discharge procedure was a powerful rejection of the Poor Law Commission's rules.

While officials frequently could not keep their inmates inside the workhouse, paupers rarely got into one another's ward or yard (“boundary”), with the highest proportion of offenses at just 2.6 in Sleaford. Samuel Dunn was punished (yet again) for “thrusting himself through the bannisters of the mens stairs to get into the mens bed rooms during the working hours” and for “leaving his work and getting on the top of the infirmary wall and talking to a boy an inmate in the infirmary.”Footnote 136 The Norfolk Mercury recorded a case in early 1847 in Shipmeadow workhouse, in which “male married Paupers (about 70 of them) forced their way into the Female Quarters: then Lock[ed] themselves in Dormitories upstairs, refusing to Surrender.” The police arrived, battered the door in, and arrested the three ringleaders.Footnote 137 The Poor Law Commissioners also sought to restrict sexual relations between men and women through the separation of the sexes, yet at North Bierley, West Yorkshire, segregation was breached and a female inmate became pregnant in the workhouse.Footnote 138 Workhouse officials were not just trying to keep inmates in their wards or yards or within the workhouse walls; they were also attempting to prevent “persons who are not inmates trying to enter the workhouse perhaps aiming to enter the able-bodied women's yard.”Footnote 139

Some forms of bad behavior envisaged by the Poor Law Commissioners were not realized and there were few offenses of pretending sickness, playing at cards or other games of chance, and lapses in cleanliness; however, able-bodied men in Southwell scratched a “graffiti” game upon the wall of their yard in the only corner that could not be observed by the master from his office (figure 4). There were also few cases of wasting or spoiling provisions, although George Hill was “refusing to eat his gruel for breakfast stating that it was not good and thick.”Footnote 140 Inmates did not spoil their provisions because, like Oliver Twist, they were hungry. Indeed, Samuel Allen was found “Stealing Potatoes from the Potato Store and Boiling them in the Mens Day Room” on 6 April 1863.Footnote 141 While diets might have been more generous in quantity than were those of the independent laborer and his family outside, workhouse diets were frequently monotonous and deficient in fat, vitamins, and minerals; the calorific intake was insufficient by 25 percent.Footnote 142 At times, locals outside the workhouse protested the workhouse fare; in Alford Union, Lincolnshire, complaints were made about the poor quality of workhouse bread.Footnote 143

Paupers were allowed to leave the workhouse with permission, to attend church services, run errands, or visit the local fair, and for children to attend school. Many, however, returned late and were therefore “absent” (17 percent in Foleshill, 14.7 percent in Sleaford). John Vine was sent to the Petworth Board of Guardians with the workhouse book, but while he was out, he got drunk and neglected to bring the book back to the workhouse.Footnote 144 Given the prohibition on drink inside, it is not surprising that men made the most of this opportunity. Drinking alcohol compounded offending behavior with the refractory offense of drunkenness. However, absenteeism and drunkenness undermined the capability of the master to keep order and must have been exasperating. Benjamin Woodcock thought such paupers “very troublesome.”Footnote 145

Trips out offered paupers opportunities beyond popping to the local public house.Footnote 146 Quite what Jane Welbourne got up to is not given in Spalding's punishment book, but she was accused of “[w]ilfully neglecting to attend a place of worship after leaving the workhouse for that purpose.”Footnote 147 Given the strictures of workhouse rules, inmates used outings as smuggling opportunities. In Shipmeadow workhouse, Suffolk, Elizabeth Stannard returned from her Sunday outing and when she was searched, “the following articles were found upon her person: three quarters of a pint of rum, two pounds of pork, half a pound of sausages, six eggs, some apples, some bread, half a pound of cheese, three packets of sweetmeats, two bunches of keys, £1 9s. 0d. in silver, 7¾d. in copper, and in her box £5 10s. 0d. in gold and many articles of clothing.”Footnote 148 This was clearly an exceptional amount of contraband to smuggle into the workhouse. In February 1870, William Stamp and John Vaise, Petworth workhouse, asked boys going out to school to smuggle them in tobacco; a few months later John Pennicard asked “Wm Brooks, who is weak minded, to buy him ½oz tobacco, when returning from church on Sunday morning.”Footnote 149 In Beaminster, Thomas Fraupton was caught with “3 salt fishes concealed upon his person”—no doubt betrayed by the smell.Footnote 150

The evidence presented here refutes King's claim that letter writing by inmates gave then an “actuality of agency” such that “the full range of punishments available to masters against refractory paupers was almost never used.”Footnote 151 The full range of punishments were used and more besides. Moreover, although the disciplinary procedures within workhouses remained relatively static, there were significant variations in punishments by location (figure 5; see also figure 9). I found that alterations of diet dwarfed most other punishments and accounted for more than half in Cockermouth (85.2 percent), Petworth (69.5 percent), Sleaford (61 percent), Beaminster (52.4 percent), and Spalding (52 percent), with workhouse masters stopping a meal or replacing a set number of meals with potatoes, rice, or bread and water. Workhouse masters might withhold meat, cheese, or butter. I found that Cockermouth usually reduced dinner to a pound of boiled rice, while both Mitford and Launditch and Norwich gave inmates bread and water. However, while these five workhouses routinely changed the diets of their paupers, I found that Patrington did so in only 9.1 percent of punishments, highlighting once again strong local policies with regard to punishment by workhouse masters and Board of Guardians.

Confinement in another ward, the refractory ward, or the lockup was common in Ampthill at one-fifth of punishments, while it accounted for around one-tenth of punishments in Beaminster, Cockermouth, and Foleshill. It was sometimes accompanied by an alteration in diet. Cockermouth's almost total resort to just two punishments, alteration of diet (85.2 percent) and confinement (10.7 percent) (a total of 95.9 percent), is extraordinary. All the other workhouses used a greater variety of punishments. Foleshill and Patrington used the widest range of punishments.

Reporting misbehavior to the Board of Guardians was one way that workhouse officials could reclaim authority over inmates. Instead of facing just one or two workhouse officials, the offender would be brought before the board for a more public dressing-down. The books describe this process variously as being “admonished,” “cautioned,” “censured,” “chastised,” “reprimanded,” “reproved,” “warned,” or even “threatened.” Ampthill admonished 19 percent of its paupers, while the figure was higher at 23 percent in Foleshill and 24.2 percent in Patrington. If “reported” and “admonished” are combined, Southwell used these methods in 34.7 percent of punishments and Patrington in 39.4 percent. It would seem that workhouse officials viewed the more lenient punishment of a good telling off as preferable in many cases to confinement or a reduced diet.

Nevertheless, workhouse masters also took cases before the courts, and local magistrates sentenced miscreants to prison: this was specified in around two-fifths to a quarter of recorded punishments in Petworth, Patrington, Beaminster, and Mitford and Launditch. Imprisonment was a serious outcome, as it might mean being locked up for months with hard labor. Having been expected to work in the workhouse, these men and women were now set to hard labor in prison. But resorting to the courts was one way of getting rid of troublesome paupers and reveals the very real power of the Poor Law and judicial machinery. The actions of William Henry Barson and Lewis Coleman at Foleshill workhouse were disastrous for everyone involved. In May 1879, the men damaged the greenhouses along with other property worth £20. They attacked the master, assaulting him with lengths of wood on the head and body, rendering him insensible, and chased the governess uttering threats of murder. The police were called, and the pair were committed to Warwick prison for trial on charge of attempted murder of the master. Brought two months later before Lord Justice Thesiger, they were sentenced to five years of penal servitude.Footnote 152 Nevertheless, the highly regionalized nature of workhouse punishments is again evident in that Cockermouth, Sleaford, and Spalding resorted to the courts and the higher authority of magistrates in far fewer instances (2.7 percent, 2.1 percent, and 2.2 percent respectively). Green's evidence allowed him to calculate an annual rate of committals to prison per hundred indoor paupers in the period 1836–1842; his findings also reveal differential rates by workhouse irrespective of the size of the workhouse, from 0.2 percent in Bermondsey to 3.9 percent in West London.Footnote 153 He notes that prosecutions of paupers were expensive, “time consuming and risky.”Footnote 154

Analysis of the eleven workhouses reveals a high degree of regional disparity both in types of offenses and in policy decisions on appropriate punishment. For this study, I chose two workhouses in Lincolnshire and two in Norfolk to allow comparison of workhouses within the same county in order to explore whether the localism identified so far was a consequence of welfare policies and practices at the county or at the union level (figures 6–9). The comparison reveals that both could be true; disparities between the Norfolk workhouses in offending behavior and in policies of punishment suggest localism at the level of the workhouse, but, in contrast, Sleaford and Spalding workhouses were very similar, raising the possibility that there was shared knowledge in Lincolnshire.Footnote 155 Of course, the New Poor Law sought to create uniformity of practice through central direction from the Poor Law Commission and later the Poor Law Board, with orders, inspections, and the auditing of accounts; yet diversity persisted.Footnote 156 Samantha Shave has shown how Boards of Guardians, assistant Poor Law commissioners, and the Poor Law Commission transferred locally derived knowledge in “knowledge networks” through correspondence, visits, and publications.Footnote 157 This was evidently not the case in Norfolk, however, where Mitford and Launditch and Norwich operated very differently.

Sleaford and Spalding workhouses were very similar in terms of size, types of offenses, and policies for punishment. Both drew upon impoverished agricultural districts, and at least half of adults in each had been employed in agriculture.Footnote 158 Both had comparable proportions of disorderly offenses (61.5 percent in Sleaford and 52.5 percent in Spalding). Assault and refusal to work made up the largest categories of offenses in both places: 19 percent (Sleaford) and 14.7 percent (Spalding) for assault, and 12.6 percent in both Sleaford and Spalding workhouses for refusal to work. Paupers in Lincolnshire objected to using the hand mill to grind wheat and barley.Footnote 159 Offenses of bad language were most common in Sleaford, while in Spalding paupers were more disobedient and reviled workhouse officers more frequently, but these differences were slight. In terms of punishment, both Sleaford and Spalding ordered alterations in diet (61 percent and 52 percent respectively), although Spalding called the police or took paupers to court in more instances. Nevertheless, the similarities in these two Lincolnshire workhouses suggest common punishment policies and shared knowledge.

In contrast, Norwich and Mitford and Launditch were very different in terms of size, offending behaviors, and punishments. Norwich, the largest workhouse in the study, was more than three times the size of Mitford and Launditch. Both were incorporated at the time of the 1834 act, but the latter dissolved its corporation in 1836.Footnote 160 Norwich remained incorporated until 1863, thus keeping “substantial protection from external interference by the Poor Law Commission,” and there was no workhouse test until the 1860s.Footnote 161 Continuing incorporation, along with the fact that Norwich was an urban union and the inmates had been employed in a far more diverse range of occupations, contributed to different cultures of resistance and responses to it by workhouse officials.Footnote 162 The Norwich workhouse master used the terms “disorderly” and “refractory” far more than did the master at Mitford and Launditch, obscuring the true nature of the offenses committed by inmates. Work-related offenses accounted for significant proportions in both workhouses, at 10.7 percent in Norwich and 15.4 percent in Mitford and Launditch. However, refractory behavior was a larger problem in Mitford and Launditch. Although paupers were more disobedient in Norwich's large workhouse (16.3 percent; compare Mitford and Launditch's 5 percent), the latter had proportionally far more of the serious offenses of assault and damage. Punishment for disobedience in Norwich appears to have contained the more violent behavior of its inmates. Understandably, the officials in the urban union needed to keep such strict order, given its size, but it is surprising that they managed to accomplish it.

Norwich workhouse officials punished paupers primarily through confinement (43.5 percent) and alteration of diet (43.1 percent), but Mitford and Laundich chose corporal punishment (30.3 percent, for boys), diet (28.9 percent), and imprisonment (26.9 percent). Although only boys were allowed to be corporally punished, in thirteen cases across all the workhouses in the study, girls were caned or slapped: Letitia Sharman's punishment in Ampthill was recorded, presumably by the workhouse master, as “slap'd her with my hand (twice).”Footnote 163 In Norwich on 16 July 1867, five girls were recorded as “absconding from the school on the morning of 16th inst. and remaining absent till brought back by the master the same evening”; the next day another four girls committed “misbehaviour in school.” The first group of girls was punished with “3 meals bread & water & 3 days oakum picking & privately punished by matron,” while the second group had “one meal bread & water & privately punished by matron.”Footnote 164 “Private punishment” was likely to have been caning—which was against regulations, as the punishment book recognized: “On enquiry it appeared that the ‘private punishment’ here reported was a slight corporal punishment inflicted before the matron by the laundress & in the presence of the superintendent of female labour. It was pointed [out to] the matron that this punishment was against the order No 126 and the matron was desired under no circumstances to punish a female child in this way again.”Footnote 165 As Green points out, “regulations acted not just to restrain paupers but also to curb the actions of staff” in an attempt to prevent abuse.Footnote 166

Conclusion

Workhouses were sites of resistance. Paupers behaved badly as a response to stifling rules and regulations that dictated every aspect of their day-to-day existence; in challenging those in authority, they questioned the very legitimacy of the workhouse.Footnote 167 A symbol of state authority, it was implemented from the center as well as at the local level, yet, as in London workhouses, maintaining discipline for workhouse officials was a constant struggle.Footnote 168 Workhouses were disagreeable institutions deliberately designed to be deterrent and disciplinary, yet pauper inmates undermined poor law policy at every turn. While the true power of the Panopticon was supposed to be its internalization by its inmates, the evidence from the punishment books suggest that paupers failed to interiorize the all-seeing eye of the workhouse master.

The most contentious aspect of workhouse life was the expectation of work. Inmates resisted picking their allocation of oakum, breaking stones, working in the garden, or cleaning the workhouse. The Poor Law commissioners were astute in their assessment that work would play a central role in the policy of deterrence, but, although they foresaw in the General Workhouse Regulations potential problems in extracting work from the poor, they could not have predicted the level of resistance to these tasks, suggesting, in turn, that paupers’ actions were not just tactical but strategic. It is also doubtful that the commissioners expected quite so many inmates to abscond over workhouse walls and fences and hedges. The ideal of the strict separation of paupers from society and from one another might have bred dread in the working classes, but it was not so easily enforced in reality. Damage to the fabric of the workhouse, particularly the breaking of windows, also demonstrated paupers’ refusal to accept spatial segregation and the prison-like buildings from which they could not come and go as they pleased. Equally, though, the difficulty of running a workhouse where paupers did in fact come in and out fairly regularly, usually for a short time, and with others circumventing the proper discharge procedure, must be recognized. Indeed, John Cole, workhouse master in Rochdale in the 1840s, described in his journal how inmates “think they can disobey, insult, or abuse us with impunity.”Footnote 169

Paupers’ frustration at workhouse life manifested in outbursts of bad language to staff—the easiest and perhaps most understandable form of protest, and one resorted to by roughly equal numbers of men and women. Unsurprisingly, it was men whose tempers flared further and who committed assault, largely upon other inmates, sometimes workhouse staff and, at times, the most vulnerable. This was the ugly side of working-class masculinity as men sought to control their immediate environment in a situation in which their social status had been reduced and they were no longer “providers and protectors” of wives and children.Footnote 170

Analysis of workhouse punishment books reveals distinct local cultures of offending; work-related offenses dominated in Ampthill and Beaminster, for example, but were minor in Foleshill, the workhouse that displayed the greatest variation in offending behaviors. Workhouse masters had a particular problem with tobacco in Petworth and in Cockermouth with disruption of prayers. While historians have long acknowledged that, despite the desire of the Poor Law commissioners to enforce uniformity from the center, local cultures of poor relief policy persisted; what has not been evident before is the strong localism in workhouse misbehavior.

Workhouse officials and magistrates used the full range of powers and punishments available to them, albeit again with local variation. Alteration of diet was the most common punishment and, since workhouse food was neither plentiful nor appealing, additional restrictions on meals would have been unwelcome to disorderly and refractory inmates. Masters and matrons were also authorized to confine and isolate inmates in refractory cells. In this way men and women could be successfully separated from society and other inmates for the period of their incarceration (incarcerated within a “carceral” building). Unruly boys were controlled with the birch. Above and beyond the regulations, workhouse officials also sought to bolster their authority and reassert workhouse discipline by asking their Board of Guardians to admonish inmates. As in London, only a small proportion of offenses ended in court; workhouse punishment books reflect the much wider pattern and full range of breaches of workhouse discipline.Footnote 171 However, it must be remembered that the analysis of workhouse punishment books reveals as much about workhouse management as it does about pauper indiscipline.

That paupers behaved badly reveals significant agency in the face of considerable power from above, highlights their attempts to negotiate relief, and shows that they were not mere subjects in workhouse regimes.Footnote 172 Such behavior also demonstrates that discipline was an endemic problem in all workhouses.Footnote 173 The agency of paupers should not be overstated, however: the power balance between workhouse officials and inmates was extremely unequal and the disciplinary apparatus of staff and magistrates was decidedly inmates. Despite the misbehavior of the poor men, women, and children, the English workhouse was, both in design and everyday experience, a deterrent institution.