Introduction

Emotions play an important role in day-to-day politics (N. Manning & Holmes, Reference Manning and Holmes2014; Osnabrügge et al., Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021; Rheault et al., Reference Rheault, Beelen, Cochrane and Hirst2016; Valentim & Widmann, Reference Valentim and Widmann2023), manifesting in the communication of political choices and actions among decision-makers and information processors, from voters to elected officials (Brader, Reference Brader2020). Yet, despite widespread recognition in neighbouring fields, emotional displays and the use of emotive rhetoric by politicians in decision-making processes were largely neglected in empirical research on legislative behaviour until recent decades, partly due to the assumed opposition between reason and emotion (McDermott, Reference McDermott2004; Sanchez Salgado, Reference Sanchez Salgado2021). We now know from a large body of work that emotions are not in stark contrast with reason and strategic behaviour (Marcus, Reference Marcus2000; Wagner & Morisi, Reference Wagner and Morisi2019). In fact, as McDermott (Reference McDermott2004, p. 699) succinctly put it, ‘emotion is, inescapably, an essential component of rationality’. In support of this view, a growing strand of research reminds us that political elites are often not simply victims of their own uncontrolled emotions; instead, they often strategically employ emotional expressions and rhetoric (Brader, Reference Brader2020; Maier & Nai, Reference Maier and Nai2020; Osnabrügge et al., Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021; Ridout & Searles, Reference Ridout and Searles2011).

This study makes three empirical contributions. First, while existing research provides an excellent account of how political elites strategically use emotive displays in their political rhetoric and action, it largely focuses on aggregate-level variation across time and space, often at the party level (e.g., Kosmidis et al., Reference Kosmidis, Hobolt, Molloy and Whitefield2019; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Jacobs, Hibbing and Smith2018; Rheault et al., Reference Rheault, Beelen, Cochrane and Hirst2016; Valentim & Widmann, Reference Valentim and Widmann2023). By doing so, recent scholarship tends to treat politicians as a homogeneous unit behaving predictably in line with their parties when it comes to the use of emotive rhetoric. I depart from this approach by examining both individual- and party-level correlates of emotive content in parliament. Second, while previous research has primarily concentrated on anger and fear, particularly in the context of populist appeals, this study broadens the scope by exploring a wider range of emotions used in political rhetoric. Third, with a few notable exceptions, the strategic use of emotions by politicians outside campaign periods is relatively underexplored, and this study seeks to address this gap by examining emotive rhetoric during both campaign and non-campaign periods.

I argue that political competition profoundly influences how politicians employ emotional displays to enhance their political standing and effectiveness. Both inter-party and intra-party competition encourage legislators to differentiate themselves from other political actors (Bowler, Reference Bowler2010; Däubler et al., Reference Däubler, Christensen and Linek2018; Louwerse & Van Vonno, Reference Louwerse and Van Vonno2022; Put & Coffe, Reference Put and Coffe2024; Papp, Reference Papp2019; Searing, Reference Searing1994; Yildirim et al., Reference Yildirim, Kocapınar and Ecevit2019), who often use emotive displays to signal commitment and sincerity to persuade colleagues and the public and to influence media coverage. In explaining the use of emotive rhetoric among legislators, I focus on three theoretically important factors that are central to power and politics in legislatures: parliamentary seniority, electoral vulnerability and party status. These factors provide a detailed lens through which to examine how political elites navigate the complex interplay of personal career trajectories, party dynamics and electoral contexts to influence both legislative proceedings and public sentiment. Focusing on nearly 520,000 parliamentary speeches delivered in the UK House of Commons from 2001 to 2015, I rely on a fine-tuned large language model to estimate emotional rhetoric within speeches along six dimensions, anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness and surprise. Drawing on recent scholarship (Osnabrügge et al., Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021; Kosmidis et al., Reference Kosmidis, Hobolt, Molloy and Whitefield2019; Valentim & Widmann, Reference Valentim and Widmann2023; Røed et al., Reference Røed, Bäck and Carroll2023), I argue that politicians make strategic use of emotive rhetoric during deliberative processes. My empirical findings show that electorally vulnerable MPs, junior MPs and MPs from opposition parties use emotive rhetoric – especially negative emotions – in their legislative speeches at higher rates compared to electorally safe MPs, senior MPs and MPs from the governing party. These findings contribute to our understanding of elites' communication styles in parliament in general, and the use of emotive rhetoric in particular.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

While there is no dearth of research on the consequences of emotional appeals in electoral processes and the use of such appeals among high-profile politicians during election campaigns (e.g., Brader, Reference Brader2005; Crabtree et al., Reference Crabtree, Golder, Gschwend and Indriđason2020; Jones, Reference Jones2003; Marcus, Reference Marcus2000; Widmann, Reference Widmann2021), empirical research on how members of parliament make strategic use of emotive rhetoric during legislative debates remains fairly scant. Existing research on emotive content in politicians' day-to-day work in legislatures has largely focused on the role and implications of negative emotions and attack behaviour among political actors during campaign periods (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Sigelman and Rovner2007; Nai & Maier, Reference Nai and Maier2020; Poljak, Reference Poljak2022; Walter & Vliegenthart, Reference Walter and Vliegenthart2010). Recent research suggests that politicians are strongly motivated to capitalize on negative emotions and fear appeals: such emotive displays and negativity are more likely to be picked up by media outlets (Haselmayer et al., Reference Haselmayer, Meyer and Wagner2019; Maier & Nai, Reference Maier and Nai2020).

Despite growing scholarly interest in communication styles in parliament, relatively little attention has been paid to the use of emotive rhetoric beyond a few specific types of negative emotions and outside of campaign periods (for two exceptions, see Kosmidis et al., Reference Kosmidis, Hobolt, Molloy and Whitefield2019; Osnabrügge et al., Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021). These are theoretically important gaps in the literature on the role of emotions in legislative behaviour for several important reasons. Firstly, much of legislators' strategic behaviour aimed at enhancing their image in the eyes of party leadership, the media and the public occurs in parliament well before elections, outside of campaign periods (Bowler, Reference Bowler2010; Searing, Reference Searing1994; Yildirim et al., Reference Yildirim, Thesen, Jennings and Vries2023). Secondly, since personality traits are shown to correlate with an individual's tendency to use negative emotions such as fear and anger in speeches (Maier et al., Reference Maier, Dian and Oschatz2022; Nai et al., Reference Nai, Tresch and Maier2022), some MPs might strategically use other types of emotions (e.g., positive emotions) that better align with their personality characteristics. Therefore, an exclusive focus on one type of emotion at the expense of others would miss the opportunity to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the use of emotive rhetoric among parliamentarians.

Studies from rather distinct fields of research highlight the importance of recognizing the distinct origins and consequences of emotions (Ridout & Searles, Reference Ridout and Searles2011; Wagner & Morisi, Reference Wagner and Morisi2019). According to the affective intelligence theory, positive and negative emotions tend to have distinct sources and trigger different cognitive mechanisms to process societal signals from the surrounding environment (Marcus, Reference Marcus2000). More specifically, while emotions such as anxiety lead to increased attention to societal cues during decision-making processes (i.e., triggering the surveillance system), positive emotions like enthusiasm reinforce habitual thinking and action (i.e., triggering the dispositional system). Similarly, Valentino et al. (Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011) maintain that different types of emotions have a distinctive influence on political participation, with anger having the greatest effect on mobilizing masses. Not only do different types of emotions have distinct effects on political behaviour, but the motives behind them also differ (Ridout & Searles, Reference Ridout and Searles2011; Valentim & Widmann, Reference Valentim and Widmann2023). It is, therefore, imperative to go beyond negativity in parliamentary rhetoric and examine a wider range of emotions during both routine and election periods.

In the literature on elite behaviour, there have been indications of a shift from focusing solely on particular types of negative emotions to adopting more holistic approaches for examining the strategic use of emotional language in political debates (e.g., Osnabrügge et al., Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021). In a recent paper, Gennaro and Ash (Reference Gennaro and Ash2022) examine the effect of televised broadcasts of floor debates on emotive rhetoric adopted by US Congress members and find that the introduction of C-SPAN broadcasts led to a growing use of emotional appeals in the House, relative to the Senate, where televised debates were introduced at the time. The authors also show that legislators from districts with higher C-SPAN viewership were more likely to adopt emotive rhetoric compared to other legislators. Other recent studies present empirical evidence in support of the strategic use of emotive language by politicians. Analysing high-profile political texts in the United Kingdom and the United States such as party manifestos, party leaders' speeches and American presidents' State of the Union addresses, Kosmidis et al. (Reference Kosmidis, Hobolt, Molloy and Whitefield2019) show that political parties make strategic decisions about when to use positive affect to communicate their policy proposals. Their results suggest that parties are incentivized to use emotive rhetoric more frequently when they are ideologically close to one another. Osnabrügge et al. (Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021) argue that the use of emotive language differs across types of debates, with high-profile debates such as Prime Minister Questions being home to intensified emotive rhetoric, relative to lower profile debates.

Past scholarship acknowledged the role emotive displays can play in fostering politicians' public visibility (Maier & Nai, Reference Maier and Nai2020). For example, research has shown that politicians strategically use emotive rhetoric, particularly during high-profile parliamentary activities, in the hope that their rhetoric will attract media attention (Osnabrügge et al., Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021). However, it is natural to expect that the motivation to adopt emotive rhetoric might differ among MPs based on their background characteristics. We know from the literature on elite behaviour that MPs from marginal seats are more attentive to the parliamentary tools at their disposal that enhance their visibility and maximize their career prospects (André et al., Reference André, Depauw and Martin2015; Bowler, Reference Bowler2010; Berz & Kroeber, Reference Berz and Kroeber2023). Due to the greater newsworthiness associated with emotive and sensational displays in parliament, I argue that electorally vulnerable MPs have a stronger incentive to make use of emotive rhetoric in debates compared to MPs with safer seats. MPs elected by a small vote margin are under pressure to deliver sensational performances in parliament to attract public and media visibility, thereby increasing name recognition. Based on this, my first hypothesis is as follows:

1 Hypothesis

MPs who are electorally vulnerable use more emotive rhetoric in their parliamentary speeches than those with safer electoral positions.

A large body of research has considered the role of seniority as a potential factor that shapes incentive structures facing elected officials (Claveria & Verge, Reference Claveria and Verge2015; Hix, Reference Hix2004; Heitshusen et al., Reference Heitshusen, Young and Wood2005; Muriaas & Stavenes, Reference Muriaas and Stavenes2023; Shomer, Reference Shomer2009). Seniority increases legislators' institutional capacity, political experience, and networks, which collectively influence their parliamentary behaviour (Cox & Magar, Reference Cox and Magar1999; Zittel & Nyhuis, Reference Zittel and Nyhuis2021, p. 323). Earlier research found that senior legislators spend less time doing constituency work (Cover, Reference Cover1980; Fenno, Reference Fenno1978). In particular, Cover (Reference Cover1980, p. 131) notes that after being ‘well-acquainted with constituency opinion’ as a result of accumulation of political experience, senior MPs may have fewer incentives to preserve their strong connections with the regional constituency. In other words, the strategic behaviour aimed at maximizing electoral and reputational benefits might diminish among senior representatives. Shomer (Reference Shomer2009) argues exactly this, where the author shows that junior politicians initiate more legislation than do senior politicians to increase their name recognition. Similarly, Yildirim (Reference Yildirim2020) shows that junior MPs respond much more strongly to the presence of legislative cameras in parliament compared to senior MPs and adjust their parliamentary behaviour accordingly. Various other studies considered the role of seniority in shaping vote- and reputation-seeking incentives, although using it only as a control variable in their models (Däubler et al., Reference Däubler, Bräuninger and Brunner2016; Sieberer & Müller, Reference Sieberer and Müller2017; Zittel et al., Reference Zittel, Nyhuis and Baumann2019). Based on this discussion, I argue that junior MPs are likely to find greater value in engaging in emotional displays during their speech time.

2 Hypothesis

Junior MPs use more emotive rhetoric in their parliamentary speeches than senior MPs.

Rheault et al. (Reference Rheault, Beelen, Cochrane and Hirst2016) posit that incumbent parties have been generally more positive than opposition parties in the United Kingdom over the past decades. Crabtree et al. (Reference Crabtree, Golder, Gschwend and Indriđason2020) argue that because incumbent parties seek to prime positivity among voters, they use more positive sentiments in campaign messages compared to opposition parties. Extending this body of work, Müller (Reference Müller2022) shows that incumbent parties express more positive emotions than opposition parties only when discussing the past and present, but not when addressing the future. Gennaro and Ash (Reference Gennaro and Ash2022) argue that politicians make use of greater emotive rhetoric when they are in the minority party. Similar to these studies, I contend that opposition party MPs have a greater incentive to use emotive rhetoric to put pressure on the incumbent, hoping their emotional displays will be picked up by the media and the public. Moreover, given the nature of parliamentary debates, government MPs are more likely to resort to technical rhetoric with relatively limited emotive language, often building on statistics and reports to defend the government's policy positions.

3 Hypothesis

Opposition MPs use more emotive rhetoric in their parliamentary speeches than government MPs.

Data and estimation

My empirical analysis focuses on legislative speeches given in the UK House of Commons. I rely on data from the ParlSpeech Dataset (Rauh & Schwalbach, Reference Rauh and Schwalbach2020), which includes every speech given in the UK House of Commons between 1989 and 2019. The ParlSpeech dataset includes the full text of each speech, as well as metadata about the speech, including the speaker, the party of the speaker, the date of the speech and the topic of the speech. The length of speeches varies from 1 to 200 words (and from 1 to 27 sentences). Because the dataset also includes brief interjections and quick remarks that cannot be considered as a legislative speech, I restrict my analysis to speeches longer than a sentence.Footnote 1

I additionally supplement the dataset with two measures made at the level of each individual speech. First, I measure the emotions expressed in each speech using a pre-trained large language model (LLM) developed to detect emotions in text. Based on the RobERTa transformers architecture (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ott, Goyal, Du, Joshi, Chen, Levy, Lewis, Zettlemoyer and Stoyanov2019), the LLM was fine-tuned to classify English text into one of the six basic emotions identified by Ekman (Reference Ekman1992). These emotions include anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness and surprise. An emotion score is assigned to each individual speech during classification. In the case that a speech corresponds particularly highly with a specific emotion, the model reflects such certainty and assigns a greater probability score for the emotion. Examples of legislative speeches, as well as pairwise correlation coefficients for the six emotion categories, can be found in the online Appendix, Table B1.Footnote 2

My second measure includes the primary political issue addressed in the text. For this task, I follow the classification scheme defined by the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP) (Bevan & Jennings, Reference Bevan, Jennings, Baumgartner, Breunig and Grossman2019; CAP, Reference CAP2023). CAP includes 21 political issues that are intended to cover all domains of political agendas. In order to classify each speech into one of these issues, I rely on a fine-tuned BERT model (Devlin et al., Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee and Toutanova2018) to classify each speech into one of the 21 issues. The model was trained on a multilingual corpus of political texts, including speeches from the UK House of Commons, the US House of Representatives, the German Bundestag, and other political documents from media and parliamentary activities. One advantage of using this model is that it was validated on English political text and achieves an F1 score of 0.85 on a held-out test set. I use the model to classify each speech into one of the 21 issues, providing a measure of the political issue addressed in each speech at the level of the individual speech.

I combine this dataset with publicly available data on MP background characteristics for the period of 2001–2015 (Thesen & De Vries, Reference Thesen and De Vries2024; Thesen & Yildirim, Reference Thesen and Yildirim2023), which covers three electoral cycles. This leaves us with nearly 520,000 legislative speeches made by 1073 unique MPs who served in the parliament between June 2001 and January 2015. The dataset includes information on MPs, speeches and period characteristics to allow for a fine-grained analysis.

My empirical strategy is twofold, for which I utilize two sets of dependent variables. The first part of my empirical analysis distinguishes between negative and non-negative emotions, whereas the second part examines correlates of individual emotion categories. To create my dependent variables, I first assigned scores to individual emotions – anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness and surprise – and then summed up these emotion scores to create a single emotive rhetoric measure. For the first part of my analysis, I created two additional dependent variables: negative (anger, disgust, fear, sadness) and non-negative emotions (joy, surprise). All three variables – negative, non-negative and combined emotive rhetoric – are continuous, ranging from 0 to 1. The distributional characteristics of these three dependent variables are provided in the online Appendix B. In the same appendix, I also illustrate the means of emotive rhetoric and negative emotions (anger, disgust, fear, and sadness) across policy categories to provide a clearer overview of these emotion categories (see Figure B2 in the online Appendix).

In the previous sections, I argued that focusing exclusively on one type of emotion while neglecting others would be a missed opportunity to present a detailed picture of how parliamentarians use emotive rhetoric, as legislators may express different types of emotions for various reasons. To fill this gap, the second part of my empirical analysis complements the first by turning to individual emotion categories, in which I estimate six regression models using the same set of independent variables. The distributional characteristics of individual emotion categories are illustrated in Figure B3 in the online Appendix.

My modelling strategy primarily relies on multilevel Poisson regressions with robust standard errors, where speeches are nested within individual MPs. My decision to use multilevel Poisson regression is driven by the skewed distribution of my dependent variables as well as the hierarchical structure of my data. Due to its relative advantage in handling non-negative skewed outcomes compared to log-linearized models and generalized linear models, the use of Poisson regressions with robust standard errors has become increasingly common in analyses dealing with non-count data (see W. G. Manning & Mullahy, Reference Manning and Mullahy2001; Santos Silva & Tenreyro, Reference Santos Silva and Tenreyro2006; Silva & Tenreyro, Reference Silva and Tenreyro2011; Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2010, Ch. 18). My results remain strikingly similar when using various other modelling strategies including fractional response models instead of multilevel Poisson models.

My main independent variables of interest are electoral vulnerability (i.e., marginality), parliamentary experience and position in government (opposition or government party). The variable Electoral Safety indicates the victory margins (i.e., percentage vote margins) in each constituency in the previous general election, ranging from 0.003 per cent to 74 per cent. The Parliamentary Experience variable measures the number of years since the MP was first elected, and ranges from 0 to 56, with a mean of 10.85. The binary Opposition MP variable measures whether the MP was affiliated with an opposition party at the time of delivering the speech.

Past research has considered district-level characteristics such as constituency size, voter turnout and the remoteness of the constituency as factors that have the potential to influence legislators' strategic calculus in parliamentary life (Bowen, Reference Bowen2022; Gay, Reference Gay2007; Karol, Reference Karol2007; Thesen & Yildirim, Reference Thesen and Yildirim2023; Willumsen, Reference Willumsen2019). Factors associated with constituency characteristics may directly or indirectly influence legislators' emotive rhetoric in parliament. For instance, past research has shown that MPs representing geographically remote districts appear less frequently in the news compared to MPs representing central districts (Thesen & Yildirim, Reference Thesen and Yildirim2023). This discrepancy may prompt representatives from remote districts to engage in emotional displays more often than others. Legislators may also alter their communication strategies based on the size of their constituency and voter turnout. Legislators from constituencies with very low voter turnout may face relatively more pressure to engage in sensational displays to mobilize voters. For these reasons, I control for geographical distance to the capital, constituency size (i.e., population) and voter turnout in the regional constituency.

Studies also suggest that ideology and partisan affiliation may be associated with emotional displays among politicians (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Oxley, Hibbing, Alford and Hibbing2011; Valentim & Widmann, Reference Valentim and Widmann2023; Widmann, Reference Widmann2021) as well as gender (Hargrave & Blumenau, Reference Hargrave and Blumenau2022). As Gennaro and Ash (Reference Gennaro and Ash2022) argue, ideologically extreme legislators may engage in emotional displays more frequently than others. Past research also documents that female MPs are more likely to use emotional language than their male counterparts, although gender differences have diminished in recent years (Hargrave & Blumenau, Reference Hargrave and Blumenau2022). While the role of age in emotional displays in parliament is underexplored, studies indicate that age may affect legislative and representational behaviour in various ways (Curry & Haydon, Reference Curry and Haydon2018). Based on these studies, I control for left-right ideological placement (using data from the Chapel Hill expert survey; see Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022), gender and age. I also control for the party's seat share and election periods. The election period variable takes the value of 1 for the month of the general election and the month preceding it. Finally, the models include issue fixed effects (i.e., individual policy areas based on the CAP). The descriptive statistics are reported in the online Appendix A.

Results

Recall that I present my empirical analyses in two parts. The first part focuses on combined emotive scores and utilizes three dependent variables: negative emotions, non-negative emotions and a variable that combines both negative and non-negative emotions (i.e., ‘emotive rhetoric'). This approach allows me to document overall patterns in engagement with emotive displays while ensuring that my findings are not driven primarily by either negative or non-negative emotion categories.Footnote 3 The second part of my empirical analysis delves deeper into the correlates of emotive displays by presenting six separate regressions for each of the emotion categories. This strategy provides a more nuanced understanding of the rationale behind emotive rhetoric.

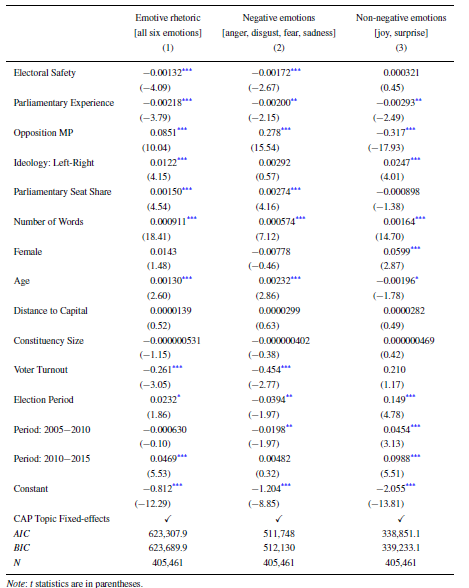

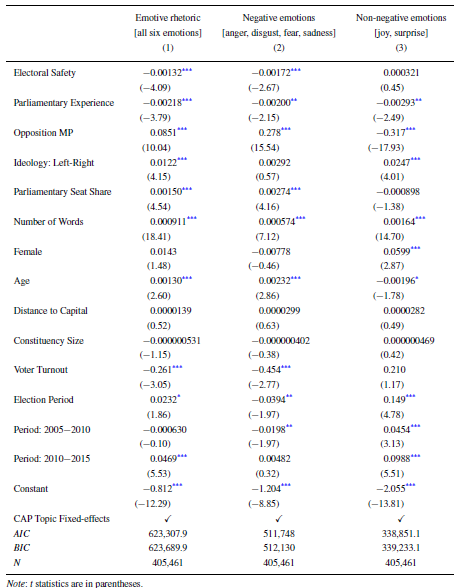

I begin by presenting the analysis based on combined emotive scores. The results from a series of multilevel Poisson regressions are reported in Table 1. Model 1 presents the combined emotive rhetoric model (all six emotions combined), whereas Models 2 and 3 show the correlates of negative (anger, disgust, fear, sadness) and non-negative emotions (joy, surprise), respectively. As seen in the table, the coefficient on the Electoral Safety variable is negative and statistically significant at

![]() $p<0.01$ in the first two models (combined emotions and negative emotions), but not in the third. The coefficient on Parliamentary Experience (the number of years since first elected) is negative and statistically significant at

$p<0.01$ in the first two models (combined emotions and negative emotions), but not in the third. The coefficient on Parliamentary Experience (the number of years since first elected) is negative and statistically significant at

![]() $p<0.01$ and

$p<0.01$ and

![]() $p<0.05$ in all three models. Taken together, these findings indicate that electorally safer and senior MPs use emotive rhetoric, both negative and non-negative, less frequently than their electorally unsafe and junior counterparts. This pattern holds except in the case of electorally safer MPs within the context of non-negative emotions. The variable Opposition Party is positive in the emotive rhetoric and negative emotions models, but negative in the non-negative emotions model (

$p<0.05$ in all three models. Taken together, these findings indicate that electorally safer and senior MPs use emotive rhetoric, both negative and non-negative, less frequently than their electorally unsafe and junior counterparts. This pattern holds except in the case of electorally safer MPs within the context of non-negative emotions. The variable Opposition Party is positive in the emotive rhetoric and negative emotions models, but negative in the non-negative emotions model (

![]() $p<0.01$), suggesting that speeches from opposition party MPs, on average, tend to feature more negative emotions and fewer non-negative emotions compared to government MPs.

$p<0.01$), suggesting that speeches from opposition party MPs, on average, tend to feature more negative emotions and fewer non-negative emotions compared to government MPs.

Table 1. Correlates of emotive rhetoric in legislative debates – Multilevel Poisson regressions with robust standard errors

Note: t statistics are in parentheses.

Abbreviations: AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion; CAP, Comparative Agendas Project.

*p ![]() $<$0.1, **p

$<$0.1, **p ![]() $ <$0.05, ***p

$ <$0.05, ***p ![]() $ <$0.01.

$ <$0.01.

The table also suggests that several other factors are associated with emotional displays in speeches. Legislative speeches made during election periods contained more non-negative (joy and surprise) and less negative emotional content compared to speeches made during non-election periods (![]() $p<0.01$ and

$p<0.01$ and ![]() $p<0.05$, respectively). Although speeches by right-leaning parties contained more emotive rhetoric compared to those by left-leaning parties, this is mainly driven by non-negative emotions. This finding provides only partial support for studies documenting a link between right-wing ideology and emotional reactions to external stimuli (Inbar et al., Reference Inbar, Pizarro and Bloom2009; Salmela & Von Scheve, Reference Salmela and Von Scheve2017).Footnote 4 The table also shows that speeches by female MPs contained more non-negative emotions compared to those by male MPs. Additionally, age is positively associated with emotive rhetoric in general and with negative emotions in particular, which may be due to various unobserved factors, such as cultural or generational influences on communication styles. District-level variables appear to have little to no relevance, except for voter turnout, which is negatively associated with the use of (mostly negative) emotive rhetoric. Finally, during the Cameron–Clegg government (2010–2015), legislative debates featured significantly more emotive rhetoric than in previous terms, driven mainly by non-negative emotions.

$p<0.05$, respectively). Although speeches by right-leaning parties contained more emotive rhetoric compared to those by left-leaning parties, this is mainly driven by non-negative emotions. This finding provides only partial support for studies documenting a link between right-wing ideology and emotional reactions to external stimuli (Inbar et al., Reference Inbar, Pizarro and Bloom2009; Salmela & Von Scheve, Reference Salmela and Von Scheve2017).Footnote 4 The table also shows that speeches by female MPs contained more non-negative emotions compared to those by male MPs. Additionally, age is positively associated with emotive rhetoric in general and with negative emotions in particular, which may be due to various unobserved factors, such as cultural or generational influences on communication styles. District-level variables appear to have little to no relevance, except for voter turnout, which is negatively associated with the use of (mostly negative) emotive rhetoric. Finally, during the Cameron–Clegg government (2010–2015), legislative debates featured significantly more emotive rhetoric than in previous terms, driven mainly by non-negative emotions.

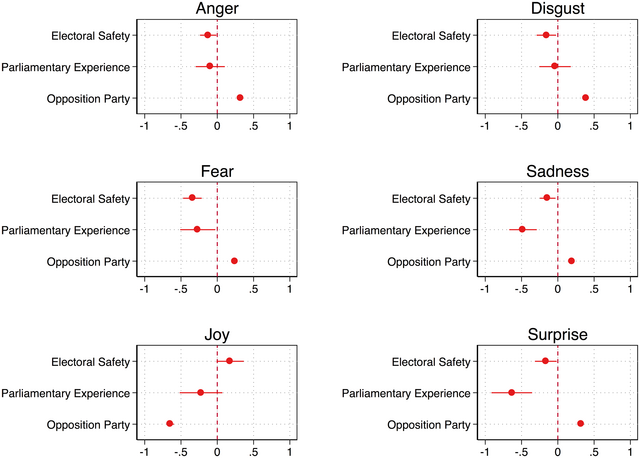

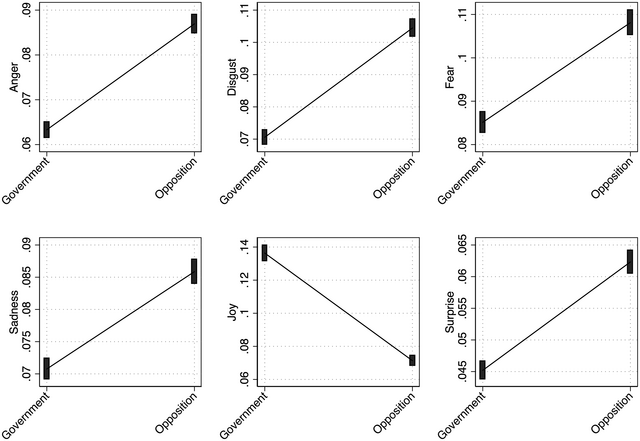

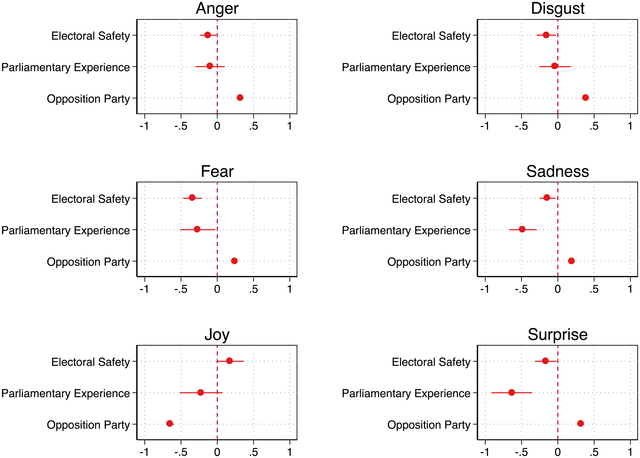

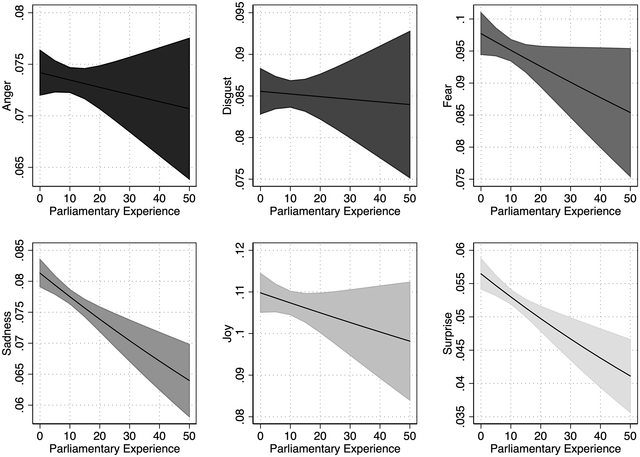

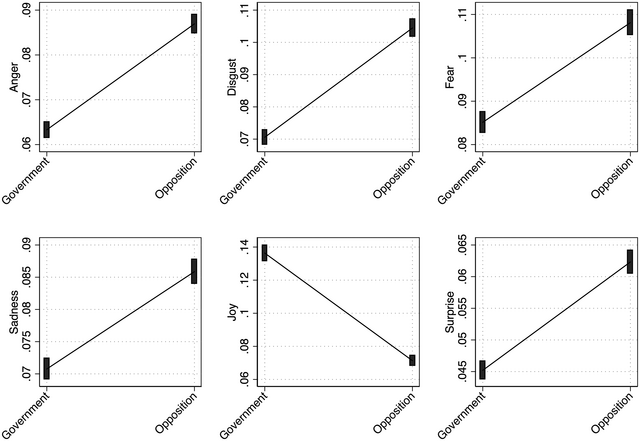

The results based on separate emotion categories are presented in Figure 1.Footnote 5 The Electoral Safety variable is negative and statistically significant in all models except for Joy, while Parliamentary Experience is negative in all six models, reaching statistical significance only in the Fear, Sadness, and Surprise models. The figure also shows that speeches by opposition party MPs feature significantly more anger, disgust, fear, sadness and surprise, but less joy, compared to government party MPs. While these results do not contradict the findings presented in Table 1, they indicate that the rationale behind employing emotive rhetoric is highly nuanced. That is, while electorally vulnerable and junior MPs tend to use more emotive rhetoric than their electorally safe and senior counterparts, they do not uniformly use all types of emotions at greater rates. The use of emotions by opposition party MPs shows relatively little variation across models (except for joy). A few other interesting observations are available from Table C1 in the online Appendix. Compared to male MPs, female MPs express more fear and joy, and less anger and disgust. Joy is more and fear is less commonly used during election periods, compared to non-election periods. Finally, MPs from right-leaning parties use joy and surprise much more frequently than MPs from other parties.

Figure 1. Correlates of individual emotion categories in legislative debates – the role of electoral safety, parliamentary experience and party status.

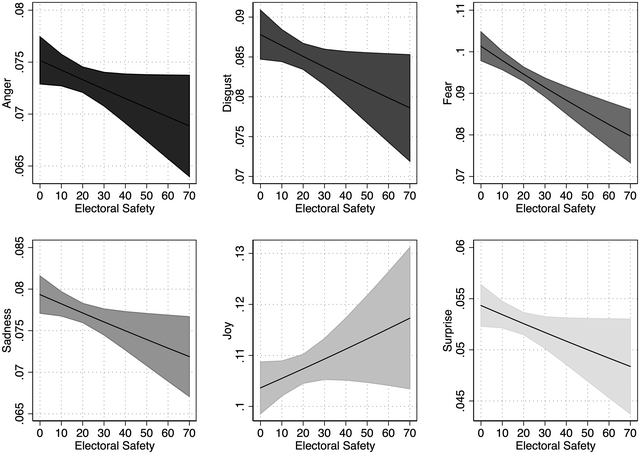

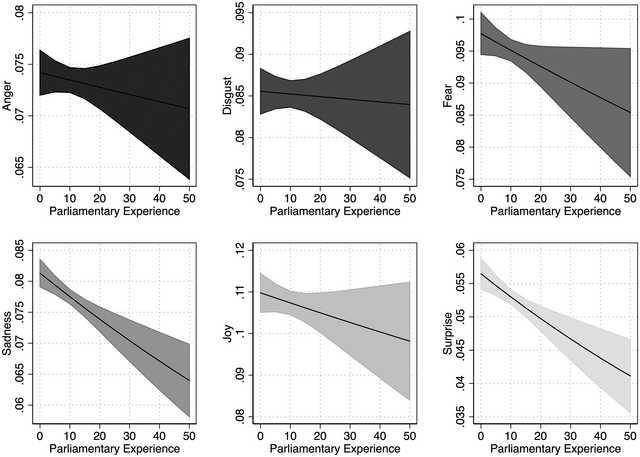

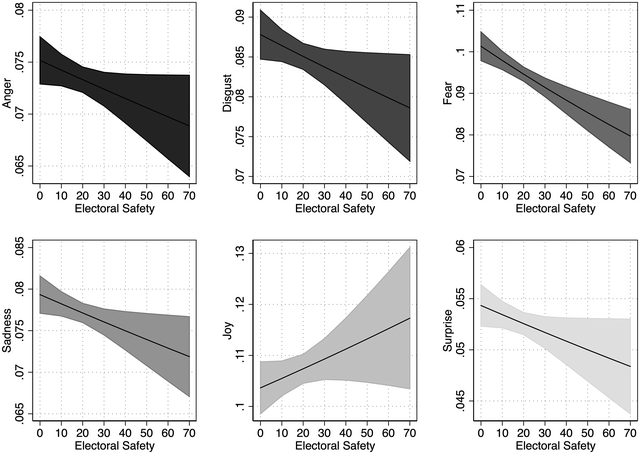

Since coefficients from Poisson models are difficult to interpret, I illustrate the average marginal effects obtained from the individual emotion models in Figures 2–4. Figure 2 demonstrates that a switch from the minimum to the maximum levels of electoral safety roughly corresponds to 10–20 per cent decreases in the intensity of individual emotion scores, except for joy. A similar trend, albeit weaker, holds for the role of parliamentary experience in emotional displays. As seen in Figure 3, the effect of parliamentary experience is more pronounced for fear, sadness and surprise and negligible for anger and disgust. Hypothetical changes in parliamentary experience from minimum to maximum correspond to roughly 10–20 per cent increases in the intensity of individual emotion scores. Finally, as seen in Figure 4, switching from government to opposition party MPs leads to approximately 20–40 per cent increases in individual emotion scores, except for joy. Overall, these figures indicate that the effect sizes are relatively modest, especially for the role of parliamentary experience.

Figure 2. The substantive impact of electoral safety on emotive rhetoric.

Figure 3. The substantive impact of parliamentary experience on emotive rhetoric.

Figure 4. The substantive impact of party status (government vs. opposition) on emotive rhetoric.

Conclusion

In his book, Drew Westen (2008, p. xv) convincingly argued that ‘The political brain is an emotional brain. It is not a dispassionate calculating machine, objectively searching for the right facts, figures, and policies to make a reasoned decision’. With growing recognition of the role of emotions in electoral politics, scholars have turned their attention to the conditions under which political actors engage in emotional displays in their rhetoric. A recent body of work has made significant contributions to our understanding of the strategic use of emotive rhetoric among political actors as well as its implications for party politics (Kosmidis et al., Reference Kosmidis, Hobolt, Molloy and Whitefield2019; Osnabrügge et al., Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021; Rheault et al., Reference Rheault, Beelen, Cochrane and Hirst2016; Valentim & Widmann, Reference Valentim and Widmann2023). However, three important areas are underexplored in this strand of research. With a few notable exceptions, this body of research has focused almost exclusively on variations in emotive rhetoric across political parties or electoral cycles. Additionally, there is little empirical work on the extent to which legislators use different types of emotions in their parliamentary work, with most scholarly attention focused on negativity in general, anger and fear in particular. Qualitative work that has considered a relatively wider range of emotions has primarily examined elite discourses during campaign periods. In this study, I sought to fill these gaps by considering the role of individual-, party-, and district-level factors underpinning politicians’ tendency to engage in emotional displays during legislative debates. My empirical analysis revealed that MPs find strategic value in adopting emotive rhetoric during legislative debates, with electorally vulnerable, junior and opposition party MPs engaging in emotional displays more frequently than their electorally safer, senior and government party counterparts.

My analysis also reveals a nuanced picture of engagement in emotive displays. The finding that the correlates of the six emotion categories differ considerably highlights the complexity of emotional dynamics in legislative settings. The results imply that the choice of emotions – whether anger, fear, disgust, sadness, surprise or joy – is not arbitrary but rather a strategic decision aimed at achieving specific objectives. As an example, opposition party MPs express joy much less frequently than government party MPs, potentially as a strategy to foster negativity regarding government policies. Another noteworthy observation concerns parliamentary experience, which is statistically associated with expressions of fear, sadness and surprise, but not with expressions of anger, disgust or joy. This suggests that junior MPs rely more heavily on certain negative emotions than others.

These results underscore the need for greater scholarly attention to the communication styles of representatives in legislatures. Advocating a shift in empirical research from the question of ‘what’ to ‘how’, recent studies have emphasized the importance of moving beyond merely examining the content of elite communication to focusing more on how elite messages are constructed and delivered (Crabtree et al., Reference Crabtree, Golder, Gschwend and Indriđason2020; Osnabrügge et al., Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021). Given the relative effectiveness of elite cues that contain highly emotive content (Westen, Reference Westen2008), legislators wishing to maximize their influence in electoral politics may pay careful attention to emotional displays that can help broaden the reach of their messages. While this suggests that ‘show horses’ may have an advantage over ‘workhorses’ in parliamentary politics, whether this is beneficial for a healthy representative democracy remains open to debate and requires further research. On the one hand, legislators who are fully aware of the power of emotive content in day-to-day politics may shift their focus from constituency service or written parliamentary activities to theatrical emotional displays during floor debates. On the other hand, MPs who increasingly adopt emotive rhetorical styles may be better equipped to convey their messages to their constituencies and the media, potentially increasing their effectiveness as representatives.

One obvious limitation of the present study is its inability to account for the role of personality traits and role orientations in shaping emotive rhetoric. Existing research shows that politicians' personality traits play a key role in determining whether they adopt a negative style in their communications (Nai & Maier, Reference Nai and Maier2020; Nai et al., Reference Nai, Tresch and Maier2022). As a direct consequence of these personality characteristics, some legislators may be more likely than others to adopt emotive rhetoric during floor debates. Similarly, certain MPs may be naturally drawn to delivering debate performances in parliament. In the House of Commons, what Searing (Reference Searing1994) referred to as ‘Club Men’ are those who enjoy watching and participating in legislative debates and are generally enthusiastic about parliamentary sessions. Those with strong oratory skills and a participatory impulse may find it valuable to engage in emotional displays during debates. However, in the absence of data on personality traits and role orientations, I am not prepared to explore these possibilities in this study.

I am also unable to examine the extent to which the ideological extremism of individual legislators influences their emotive rhetoric. Previous scholarship found that ideologically extreme legislators use emotive rhetoric at higher rates than others (Gennaro & Ash, Reference Gennaro and Ash2022). It would be particularly interesting to explore how individual-level ideology interacts with electoral vulnerability and seniority to shape emotional displays in parliament. Future research that takes these potential factors into account, ideally in different electoral settings (e.g., under varying electoral rules), could prove useful in advancing our understanding of the role of emotions in elite communications in parliament.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Zach Dickson for his assistance with data collection and his feedback on earlier versions of the paper. I also thank the participants of the panels at the Eighth Conference of the ECPR Standing Group on Parliaments (2023) and the Norwegian National Political Science Conference for their valuable comments.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8UBBKC.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table B1: Pairwise Correlations among Emotion Categories

Figure B1: The Distribution of Emotive Rhetoric in Legislative Speeches

Figure B2: Mean of Emotive Rhetoric and Negative Emotions (anger, disgust, fear, and sadness) across CAP Policy Categories

Figure B3: The Distribution of Individual Emotion Categories

Figure B4: Mean of Emotive Rhetoric and Negative Emotions across Time

Table C1: Correlates of Individual Emotion Categories in Legislative Debates - Multilevel Poisson Regressions with Robust Standard Errors