5.1 Introduction

Historically, the German public administration enjoyed a high reputation for its rigor and effectiveness. Yet, its nested structures and growing responsibilities have turned it into an administrative freighter that is unwieldy and difficult to steer. Over the past decades, the number of policies has drastically increased (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019) while implementation capacities are a contested good. Renegotiations over budgets and potential reallocation of capacity frequently lead to politico-administrative conflict and incur political costs. Consequently, consistent policy prioritization, even when required by limited resources, is often avoided by political and administrative leaders. This begs the question of how much of a task load the German administrative “freighter” can carry. Has it already reached its capacity? And if so, has it been forced into policy triage, discarding tasks to stay afloat?

In Germany, clear instances of administrative failure, such as the tragedy of the Duisburg Love Parade, are rare and often treated as isolated incidents (Seibel, Reference Seibel2022; Seibel et al., Reference Seibel, Klamann and Treis2017). However, such visible administrative failures are often just the tip of the iceberg. Most administrative actions and organizational decisions that determine administrative resilience take place “beneath the surface.” This chapter examines Germany’s implementation bodies within the environmental and social policy administration and shows varying structural risks and hidden policy triage activities in the different bodies. Therefore, this chapter examines the vulnerability of key implementation bodies to becoming overwhelmed, potentially requiring them to prioritize and triage their policy activity.

We demonstrate that, while most core tasks are still effectively managed by environmental and social administrators, persistent and accumulating problems – particularly at the local level – along with exhausted compensatory mechanisms and neglected forward planning, have made policy triage increasingly evident. However, significant variation between implementation bodies exists across both sectors and levels of government.

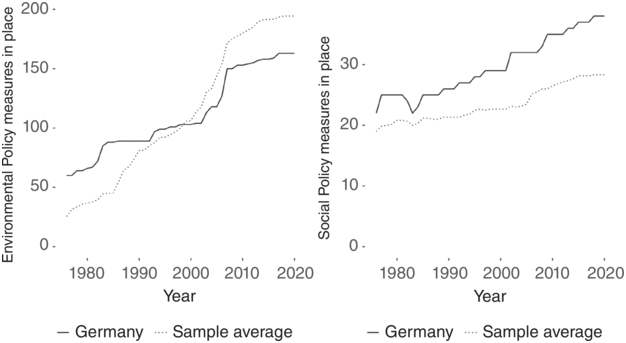

In Germany, the evidence suggests moderate levels of policy triage overall. However, distinct patterns emerge when comparing the environmental and social sectors. In the environmental sector, differences are primarily observed across administrative levels. Higher level authorities, such as the State Ministries for the Environment (Staatsministerien für Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz; StMUV) and the State Offices for the Environment (Landesämter für Umwelt; LfU), appear less affected by triage pressures. In contrast, local-level bodies such as the Water Management Offices (Wasserwirtschaftsämter; WWAs) and District Offices face moderate declines in implementation quality and delays in interventions. In the social policy sector, the moderate triage level results from variation between and within agencies. Some organizations, such as the Federal Employment Agency (Bundesagentur für Arbeit; BA), demonstrate minimal evidence of policy triage. Conversely, other entities – including Jobcentres, the Federal Pension Insurance (Deutsche Rentenversicherung; DRV), and state-level social welfare agencies (Zentrum Bayern Familie und Soziales; ZBFS) – exhibit higher levels of triage and substantial variation in vulnerability to overload. Across these organizations, compensatory mechanisms, such as flexible management practices and staff motivation, play a critical role in mitigating overload and preserving operational functionality. Yet, in most organizations under study, policy triage is becoming more frequent and severe. Overall, our findings highlight growing pressures that, if left unaddressed, could result in increasingly severe triage decisions in the future.

In the following sections, we start with an outline of German public administration and its core characteristics determining expectations on policy implementation (Section 5.2). In Section 5.3, we analyze how the determinants of policy triage appear in the different implementing organizations under examination. The section begins by assessing the overload vulnerability of individual environmental and social implementation authorities (Section 5.3.1). In doing so, we look at blame-shifting limitations that hinder central policymakers to deflect blame for poor administration as well as at implementation bodies’ capacities to affect task load and available implementation resources via external resource mobilization. Furthermore, we scrutinize the internal means individual authorities can rely on to compensate for potential workload peaks (Section 5.3.2). Finally, Section 5.4 elaborates on the consequences, that is, to what extent organizations feel compelled to engage in policy triage due to their workload situations. Special attention will be paid to future developments that are already on the horizon. The final Section 5.5 concludes.

5.2 Structural Overview: Environmental and Social Policy Implementation in Germany

Public policy implementation in Germany exhibits several distinctive features that shape the broader context in which the responsible bodies operate. The German system is characterized by a federal structure with a pronounced decentralization of the institutional setting and high degree of autonomy at lower government levels (T. Bach & Veit, Reference Bach, Veit, Veit, Reichard and Wewer2019; Kuhlmann & Wollmann, Reference Kuhlmann and Wollmann2013). The German Basic Law (Grundgesetz; GG) defines the responsibilities, with most legislative powers being (de facto) located at the national level. The Länder – as the main administrative tier – hold some legislative competencies and have the right of co-decision via the Bundesrat, which is considered one of the strongest second chambers worldwide and embodies a strong subnational political voice (Hueglin & Fenna, Reference Hueglin and Fenna2015; Wehling, Reference Wehling1989). In Germany, the local level is constituted by municipalities (Gemeinden), district-free cities (kreisfreie Städte), and districts (Kreise). In contrast to the federal level, the Länder can entrust districts and municipalities with implementation tasks (Scherf, Reference Scherf, Kost and Wehling2010) despite the “general competence clause” of local self-government (Kuhlmann & Wollmann, Reference Kuhlmann and Wollmann2019).

As the third largest economy in the world (as of 2024, IMF, 2024) and the paragon for a rigid Weberian bureaucracy, the German administrative system raises expectations in managing workload and performing implementation tasks effectively. First, resource-wise, Germany’s government sector accounts for just over half of its gross domestic product (GDP; OECD, 2020c). Administrative expenditure has also risen steadily over the past decades while the German debt ratio, indicating fiscal sustainability, is well below the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average (OECD, 2021a). Second, it reflects the characteristics of a Weberian bureaucracy, adhering to the principles of legality, official hierarchy, rule-based management, and functional specialization (Classen, Reference Classen, Sommermann, Krzywoń and Fraenkel-Haeberle2025). Together with the high professionalism of civil servants and a deeply rooted culture of bureaucratic socialization (T. Bach & Veit, Reference Bach, Veit, Veit, Reichard and Wewer2019; Jann, Reference Jann, Ellwein and Holtmann1999; Kuhlmann, Reference Kuhlmann, Veit, Reichard and Wewer2019; Seibel, Reference Seibel2016), these features have enabled Germany to achieve comparatively high levels of government effectiveness for the most part of its recent history (World Bank, 2023). Finally, Germany’s design as cooperative federalism further supports administrative performance in line with the comparative advantages of consensual systems in terms of “government effectiveness, inflation containment, coherence of policy design and sustainable policy performance” (Freiburghaus et al., Reference Freiburghaus, Vatter and Stadelmann-Steffen2023: 1107; see also: Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). Local implementation is crucial for maintaining the quality of public service delivery and bolstering public acceptance of the administrative system (Ruge & Ritgen, Reference Ruge, Ritgen, Kuhlmann, Proeller, Schimanke and Ziekow2021; Sommermann, Reference Sommermann, Kuhlmann, Proeller, Schimanke and Ziekow2021). This decentralized approach is reinforced by advanced communication and coordination tools, as well as strong capacities for preparing and monitoring legislation that enable effective cooperation across governmental levels.

Yet, there are several problems intrinsic to the German system that dampen the positive expectations for Germany’s administrative performance. The first challenge is based on the complexity of administrative structures. The fragmentation and overlap of tasks and responsibilities among federal, state, and local authorities – along with the growing influence of the European Union (EU) especially in the environmental sector – create both political and administrative interdependencies (Politikverflechtung) (Bogumil & Kuhlmann, Reference Bogumil and Kuhlmann2022; Scharpf et al., Reference Scharpf, Reissert and Schnabel1976). While interdependencies can enable standardization and stability while maintaining flexibility and organizational autonomy, blame-shifting and control deficits are potential negative consequences blurring accountability for administrative outcomes. At the same time, excessive coordination and standardization bear the risk of negating the advantages of decentralized task fulfillment (Bogumil & Kuhlmann, Reference Bogumil and Kuhlmann2022; Kuhlmann & Franzke, Reference Kuhlmann and Franzke2022).

Second, the combination of nested structures and multiple veto players inhibit central leadership (T. Bach & Veit, Reference Bach, Veit, Veit, Reichard and Wewer2019; Kuhlmann & Wollmann, Reference Kuhlmann and Wollmann2013) and reduce Germany’s reform capacity (Lindvall, Reference Lindvall2010; Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2000). Despite repeated attempts to simplify the administrative system (Röber, Reference Röber, Veit, Reichard and Wewer2019), including support from the European Commission and the OECD for better regulation, progress has been limited. The establishment of the National Regulatory Control Council (Normenkontrollrat) in 2006 aimed to reduce bureaucracy and improve legislation. Yet, reforms often fail due to resistance from veto players or become entangled in compromises and conflicting responsibilities (T. Bach & Veit, Reference Bach, Veit, Veit, Reichard and Wewer2019; Jantz & Veit, Reference Jantz, Veit, Veit, Reichard and Wewer2019).

Finally, the strong focus on legalism and formalism significantly hampers the efficiency and adaptability of Germany’s administrative system. Tight staffing levels – well below the OECD average (OECD, 2021b) – further exacerbate these challenges. External pressures, such as technological advancements and Europeanization, demand administrative reforms, but legalism delays these changes, consumes limited personnel resources, and creates ambiguities as “correct” implementation becomes increasingly case-specific (Döhler, Reference Döhler, Veit, Reichard and Wewer2019). A clear symptom of these issues is the increasingly high volume of administrative court cases (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2022), where not only citizens but also public authorities seek clarity amid growing complexity and perceived arbitrariness. For the administration, turning to courts helps manage uncertainty, avoid lawsuits, and establish procedural standards to ease operational burdens (Döhler, Reference Döhler, Veit, Reichard and Wewer2019; Sommermann, Reference Sommermann, Kuhlmann, Proeller, Schimanke and Ziekow2021).

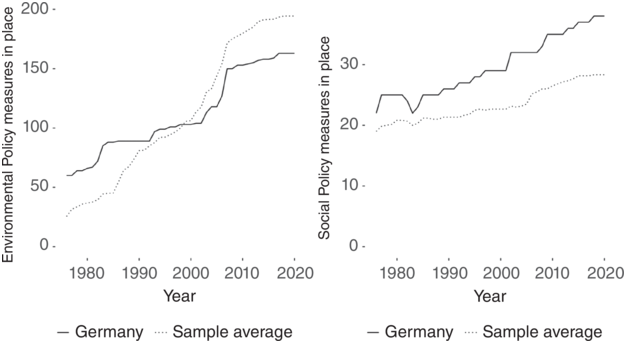

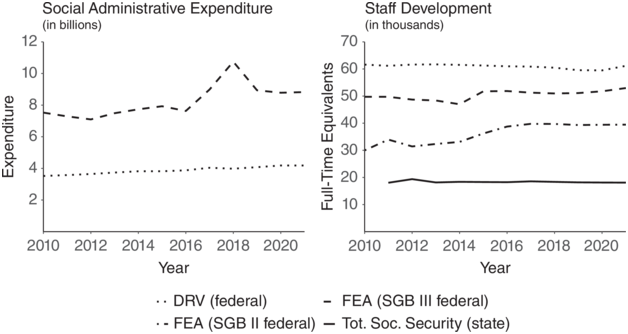

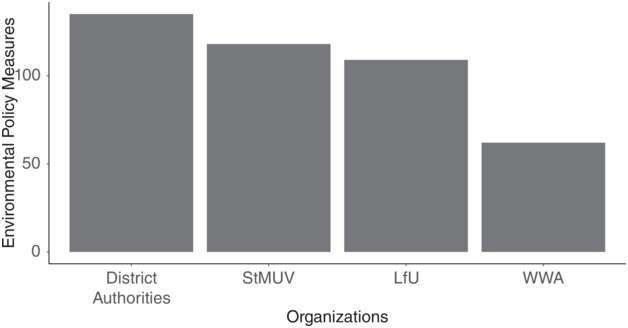

Turning to the two policy fields under study, the social and environmental policy sectors present good cases of comparison, as the environmental policy administration is strongly shaped by federal structures, while the social sector is shaped by self-administered central agencies with regional branches and local offices. In both sectors, implementation and administrative performance are shaped by the complex framework conditions described earlier, which are further challenged by the substantial growth of both environmental and social policies, as illustrated in Figure 5.1. This policy growth translates into increased implementation burdens that must be managed by the sectoral implementation bodies. In the environmental sector, Germany, once a leader in expanding its policy portfolio, began to lose this position in the late 1990s, with the pace of growth slowing further around 2010. Nevertheless, the volume of tasks in this area remains substantial. In contrast, social policy has experienced both a higher growth rate and a larger portfolio size, surpassing the average across the country sample.

Figure 5.1 Environmental and social policy measures in Germany.

In the following, we will examine the competence and burden allocation of how the increasing implementation demands resulting from policy expansion are distributed across the implementation bodies in the two sectors under analysis. To do so, we discuss how the implementation burden has developed in each policy field and how competences and burdens are allocated between the implementation organizations under study.

5.2.1 Competence and Burden Allocation in Environmental Policy

In environmental policy, the main legislator is the federal level: Most environmental policy is subject to the concurrent legislative powers (Art. 72 and 74 GG). The Länder may only deviate from federal laws with respect to nature protection, landscape, and parts of water resource management (Art. 72 paragraph 3 GG). The central role of the federal level remains evident, even when considering the growing legislative activity of the EU as a major driver of environmental policy (Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher & Zink, Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2024): The federal level in Germany is obliged to transpose European acts into national law.

In terms of substance, Germany’s environmental policy landscape has evolved significantly in recent years. Protection measures have intensified, accompanied by extensive reporting obligations that place considerable burdens on environmental implementation bodies. Regulatory details have proliferated, with laws such as the Federal Emission Control Act being revised more frequently and in greater detail, so that even minor changes now require extensive implementation efforts (Bardt, Reference Bardt, Gadatsch, Ihne, Monhemius and Schreiber2018; Böcher & Töller, Reference Böcher and Töller2012; von Lüpke & Wietschel, Reference von Lüpke, Wietschel, Böttger, Jopp, Abels and Roth2021). Technological advancements, which affect both policy measures and implementation infrastructure, combined with increasing regulatory complexity, have stretched the capabilities of existing staff, making it challenging for traditional personnel to keep up with evolving demands. Additionally, EU initiatives, such as the Habitats Directive and the Water Framework Directive, have significantly increased the workload for national and subnational authorities, challenging existing implementation structures and regulatory approaches, particularly when institutional fit is low (Brendler & Thomann, Reference Brendler and Thomann2024; Knill & Lenschow, Reference Knill and Lenschow1998).

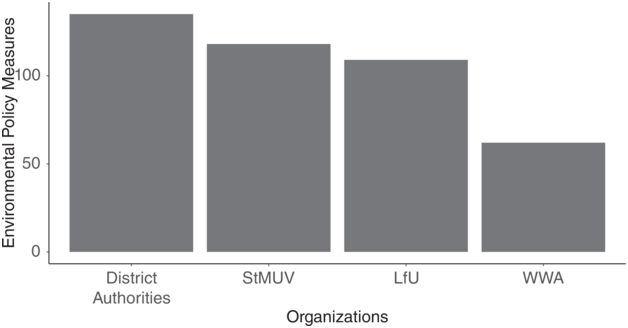

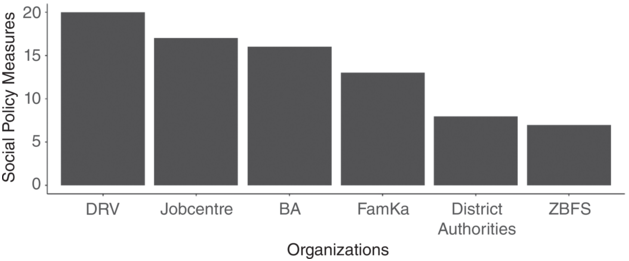

While most legislative competencies lie at the national (and supranational) level, it is the Länder, along with their regional and local authorities, that are responsible for policy implementation (GEA, 2019). As shown in Figure 5.2, environmental implementation tasks are mainly assigned to subnational authorities. Bavarian authorities are used as cases for this investigation. The selection of Bavaria, a relatively capacity-rich and large Land, serves as a least likely case for observing policy triage, considering the general implementation structures in Germany, thereby enhancing the robustness and significance of our findings. Meanwhile, the focus on local authorities within the Upper Franconia region ensures representativeness, as it closely aligns with the German average in terms of GDP per capita, population density, and unemployment rate during the observation period (Gerring, Reference Gerring2017).

Figure 5.2 Environmental policy measures per organization.

The StMUV handles preparatory and advisory functions, while the LfU acts as a technical and scientific service center, supporting the StMUV with much of the groundwork. District Offices, by contrast, carry out the majority of “hands-on” implementation tasks. Their broad range of responsibilities includes tasks such as licensing and permitting industrial facilities with regard to their pollutant emissions or wastewater discharges. When enforcing air quality standards, District Offices largely operate independently, allowing them the discretion to engage additional private actors for expertise and measurement capabilities. For water management, District Offices receive support from WWAs, which are centrally coordinated technical authorities responsible for managing water bodies and their use within larger regional clusters of districts. Hence, while the StMUV and LfU have faced growing political attention and rising policy demands, it is particularly the local implementation bodies – District Offices and WWAs – that have experienced a significant increase in accumulating workload in recent decades.

5.2.2 Competence and Burden Allocation in Social Policy

Similar to environmental policy, social policy in Germany primarily falls under the framework of concurrent legislation (Arts. 72 and 74 GG). However, the federal government has taken a dominant role in this area, marked by extensive legislative activity and clear leadership. As a result, the Länders’ room for maneuver is significantly constrained. Their legislative scope is largely restricted to supplementary benefit or support programs, for example, in the field of family policy.

Sketching the evolution of social policy in the more recent past, a significant innovation in unemployment policy came with the Hartz Reforms between 2003 and 2006. The resulting Social Security Code II (Sozialgesetzbuch II; SGB II), which governs basic benefits for job seekers, is marked by its emphasis on individualized approaches to entitlements, contributing to substantial complexity and implementation burdens. Case-by-case approaches significantly contribute to the growing workloads in the social sector. This is also evident in pension policy, where lump sum payments have been largely replaced or supplemented by income-related benefits, necessitating individual assessments for each case. Adding to the complexity, the General Data Protection Regulation further hampers the efficiency of case management. As one interviewee described it, navigating the current social policy landscape under these conditions feels like “skating on sandpaper” (GER19; Brussig, Reference Brussig, Liebig, Matiaske and Rosenbohm2017; Reiter, Reference Reiter2017; Weise, Reference Weise2011; Zimmermann & Rice, Reference Zimmermann, Rice, 348Heidenreich and Rice2016).

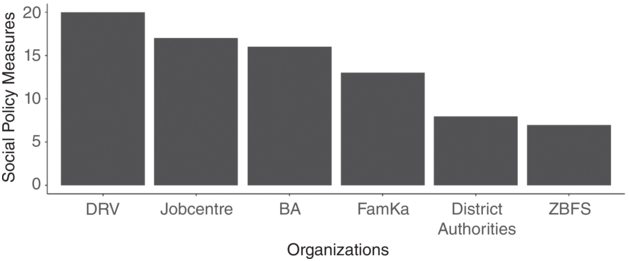

Unlike environmental policy implementation, which is largely managed by the Länder (and ultimately local) administrations, social policy implementation in Germany is dominated by central authorities and agencies. Within this framework, four key bodies play a central role, handling the majority of tasks in this domain, as illustrated in Figure 5.3. These include the DRV, the BA along with its FamKa, the Jobcentres, and, finally, the state-level social welfare agencies (ZBFS).

Figure 5.3 Social policy measures per organization.

In pension policy, the largely self-administered DRV forms part of Germany’s indirect federal administration and is responsible for implementing several key pension programs that were modified or introduced during the observation period. They include the Basic People’s Pension, Mütterrente I and II, the deduction-free old-age pension from age 63, the Flexirente, and the adjustment of East/West pensions. The German pension insurance system operates through a decentralized structure comprising sixteen independent regional institutions that collectively constitute the DRV.

In labor market policy, in contrast, the BA, a self-administered federal authority, and its local employment agencies implement means-tested benefits for unemployed individuals (ALG I scheme, SGB III). The BA is also responsible for unemployment prevention measures, including the German flagship policy “Kurzarbeitergeld” (short-time allowances). Joint facilities (Jobcentre), which combine the efforts of local authorities and local employment agencies, manage the provision of the Basic Unemployment Allowance (ALG II scheme, SGB II). They are also tasked with supporting long-term unemployed individuals through initiatives such as job accession programs and additional benefits, such as education vouchers.

With regard to family policy, the BA’s FamKa administers child benefits (Kindergeld) and functions as a tax authority in this domain. Finally, the state level plays a central role in implementing federal social assistance policies, particularly in the domain of parental benefits (Elterngeld and Elterngeld Plus). In Bavaria, for instance, the welfare agency ZBFS, with its seven regional offices, serves as the central authority for the implementation of parental benefits and related social assistance policies.

While environmental workloads are more unevenly distributed across different actors and levels, social policy administration sees a more consistent increase in workload and complexity across its various implementation bodies. For the DRV, the labor market administration, and the smaller actors in family policy administration, the rise in implementation burdens tends to be comparable, with the workload growing in a similar manner across these institutions.

5.3 Policy Implementation in Germany: Collapsing from Below?

While the implementation burden grows across all organizations under study, differences in their exact extent prevail. The following section examines organizations’ vulnerability to overload, which explains the differences in the allocation of implementation burden. The analysis focuses on blame-shifting opportunities for central policymakers and implementation authorities’ capacity to mobilize external resources, as theorized in Chapter 2. Subsequently, we then discuss implementation bodies’ capacities to manage and compensate overload, addressing the implications of rising task demands.

5.3.1 Overload Vulnerability in German Public Administration

The intricate structure of German cooperative federalism, as outlined earlier, tends to create rather than limit opportunities for central policymakers to shift blame. The pronounced decentralization of implementation as well as shared competencies allow national policymakers to deflect responsibility for poor administrative outcomes onto subnational or decentralized authorities. However, at least until 2021, these blame-shifting opportunities have been tempered by the notable stability and continuity of German governments. For instance, Angela Merkel’s four consecutive cabinets (2005–2021) included three grand coalitions with the Social Democrats (2005–2009; 2013–2021). When governments anticipate staying in office, they have stronger incentives to prioritize the long-term impact and implementation outcomes of their policies, as citizens are likely to hold them accountable for any shortcomings. Governments risk facing blame for deficient implementation in the long run. Nevertheless, it remains uncertain whether this trend will continue, particularly considering the rise of populist parties and the increasing fragmentation and diversification of government coalitions across Germany (Fernández-i-Marín et al., Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Hinterleitner, Knill and Steinebach2025b).

Overload vulnerability can also be mitigated by mobilizing external resources. When increases in implementation tasks are accompanied by proportional capacity expansions, overload can be effectively avoided. Such capacity expansions may be achieved through regular financing mechanisms and resource responsibility of policymakers or through a strong political voice by implementation bodies, which use their political influence to draw attention to capacity demands. At the macro level, Germany presents a mixed case. While the German “Konnexitätsprinzip” (i.e., the principle that the governmental level responsible for formulating a task must also provide the necessary resources for its execution, as per Article 104a GG) theoretically prevents overload by mandating parallel capacity expansions, its practical application often diverges (Knill et al., Reference Knill, Bauer and Benzing2007). Resource allocation in Germany typically follows complex procedures within the frameworks of ordinary budget planning, fiscal equalization, and tax revenue distribution. Furthermore, the political principle of maintaining “zero debt,” championed by both the Christian Democrats and Liberals, makes resource mobilization inflexible and even more contentious. Nevertheless, German implementation bodies have a relatively strong political voice in articulating capacity shortages. The influential Bundesrat safeguards the interests of the Länder as primary implementers, complemented by ministerial conferences and various implementer associations, such as the German District Association (Deutscher Landkreistag), which facilitate coordination and the exchange of implementation feedback (Hegele & Behnke, Reference Hegele and Behnke2017; Hueglin & Fenna, Reference Hueglin and Fenna2015; Wehling, Reference Wehling1989).

Environmental Administration: Challenges Cascade from Top to Bottom

In the environmental sector, the federal policymakers are only moderately confronted with the potential political costs of unsuccessful policy implementation. While the federal level sets policies, the Länder, along with their regional and local authorities, are responsible for implementation. Apart from the WWAs, the implementation of environmental line policy falls under the remit of the general administration. This system of environmental federalism, characterized by a complex interplay of responsibilities, provides significant opportunities for blame-shifting between policymakers and implementing organizations. As one ministerial official notes, there are not only “gaps in knowledge that exist at the federal level” but also a tendency for federal officials to remain disengaged from state-level administrative challenges: “a federal environment minister, for example, is generally uninterested in whether state administrations have sufficient staff – unless it becomes a political issue” (GER38).

Blame-shifting, however, is not one-sided. Federal policymakers often criticize local implementing authorities for inadequate enforcement of environmental standards, while state and municipal officials argue that insufficient federal support or overly ambitious EU regulations hinder effective policy execution:

I support self-criticism, but public administration is often used as a scapegoat because it’s convenient. You don’t address a specific person, but you blame a large institution for all sorts of things and then you’re off the hook.

Furthermore, considering the substantial influence of international and EU environmental policies, national governments frequently externalize blame for unpopular decisions or policy failures to supranational institutions (GER13).

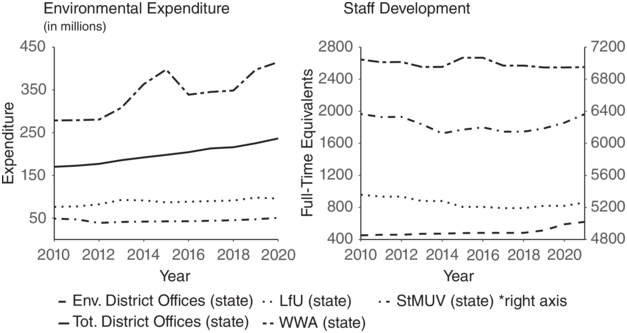

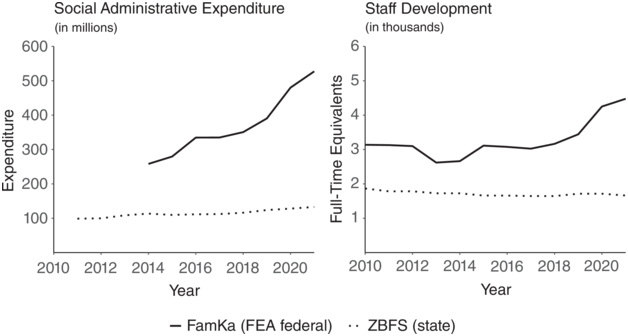

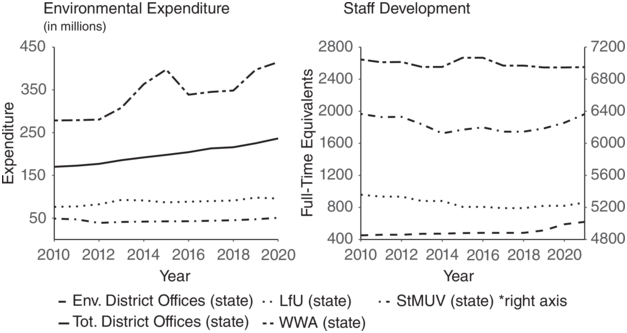

Since blame-shifting opportunities in Germany have been mitigated in the past by the country’s high levels of government stability, organizations in the environmental sector are more vulnerable to overload in the context of resource mobilization. Environmental expenditure is predominantly incurred at the local level (IMF, 2009; see also Figure 5.4), but is funded through a complex mixture of taxation, equalization, and fees, whose financing involves the federal, state, and municipal level (GEA, 2019). Occasionally, the complex procedure leads to funding conflicts or misunderstandings between the different levels of government, further complicating effective resource allocation (e.g., BayORH, 2018).

Figure 5.4 Development of expenditure and staff within environmental policy implementation at the state level (Bavaria).

When competing for budgetary resources, environmental administration is often perceived as disadvantaged compared to more established areas of state activity. Budget and personnel decisions are complex multilevel negotiations (GER32; GER17; GER13), ultimately decided by the State Finance Ministry and political leadership (GER32). Figure 5.4 reflects trends in environmental expenditure and staffing, consistent with implementers’ concerns.

Notably, resource mobilization differs significantly across implementation organizations, with higher level authorities generally being better off than the local authorities. First, the StMUV and LfU are better positioned to secure sector-specific monetary resources, as they have more direct access to decision-making and a stronger political voice (GER32; GER17). Additionally, their larger organizational size allows them to convert funds into personnel through project positions. However, these positions, while helpful, are a second-best solution, as they are temporary, project-specific, and often result in periodic expertise losses and reduced flexibility for ongoing operations (GER25; GER13; GER17; GER23).

Second, for the higher level authorities, task increases sometimes lead to additional regular staff (GER22; GER32; GER25) when attracting political attention or when counting as “politically well-sellable” (GER24). For instance, when expanding the groundwater monitoring network under the Water Framework Directive and Fertilizer Ordinance, new positions were created, but only ten out of fifty requested were approved: “We asked for 50 posts, and so far, we’ve received approval for ten. That’s a ratio of 1:5, and the 50 posts were not exaggerated, we really need them” (GER32). In addition, many tasks must already be fulfilled before the promised additional personnel and budget materialize (GER38; GER17; GER22).

Finally, the StMUV, and to a lesser extent also the LfU, benefit from their closer proximity to the political level, making it easier to pass on feedback, particularly on technical assessments related to task design (GER21; GER22; GER23; GER28; GER32; GER16; GER13). Yet, with increasing distance between the administrative and the political level (e.g., vis-à-vis the EU), the more likely practical know-how will be ignored (GER17; GER13; GER38; GER22), and administrative efforts to influence decision-making can take decades before the political level responds (GER17). As one interviewee notes, “there are tensions between what appears important politically and what the experts say. What is important to experts, is often not very ‘sexy’ politically” (GER13).

Shifting the focus to the local level, bigger challenges with regard to resource mobilization become apparent. First, higher level authorities often pass on capacity pressures to local authorities (GER28; GER33; GER32), including the environmental sections in District Offices and the WWAs, leaving them at a distinct disadvantage in resource allocation. Further constraints for local authorities arise as there are no general obligations for the state to fully staff the state functions that are to be carried out by the District Offices with state personnel (StMI, 2020). Additionally, the staff resources provided by the state are determined by a standardized calculation model, usually based on population size rather than local needs. This poses a significant problem in the environmental sector, where task loads are heavily influenced by local factors such as the density of industrial and agricultural activity (GER35; StMI, 2020).

Second, local environmental policy implementation directly competes with other areas of local government for resources. Administrative costs not covered by the state must be financed by the districts themselves (Art. 53, Paragraph 2 of the District Code of Ordinances). The head of the district authority, who holds both political and administrative leadership roles, is responsible for allocating staff and resources. As a result, the ability of local authorities to carry out environmental tasks assigned by the state, federal government, and EU largely depends on decisions made by local leaders (GER35; GER16). Yet, with respect to their political voice, local authorities often feel neglected and unheard (GER36; GER29; GER33; GER37; GER35). Apart from a few successful interventions (Bayerischer Landkreistag, 2018; GER36), problems are either ignored or addressed too slowly. For example, the director of one of the WWAs shared their frustration with implementing water pollution prevention measures:

I never miss an opportunity to tell the ‘high lords’ that the outcomes they expect […] will, for various reasons, fall short of their hopes. […] All I can say is: ‘I’ve been telling you this from the beginning, and it won’t change until we have better policy’ […] I constantly try to communicate to the government and the ministry to make it clear that this is not the fault of my employees.

Third, local implementers’ influence is further hindered by the lack of vertical coordination from the LfU and StMUV (GER38; GER28). The absence of hierarchical support and mediation is acutely felt by WWAs and District Offices, especially since they cannot compensate for it by forming horizontal alliances. The necessary horizontal coordination – bringing together diverse actors such as citizens’ initiatives, trade, industry, agriculture, and landscape conservation associations – exceeds already limited capacities. This results in deteriorating relationships between implementers and regulatees (GER35; GER16; GER33; GER32; GER28; GER36), which not only weakens local authorities’ political influence and their ability to mobilize resources but also adds to their burdens. Consequently, local authorities face more disputes and lawsuits, further straining the environmental line administration (GER16; GER21).

In summary, local authorities in Germany’s environmental administration are increasingly overburdened due to a lack of resources and limited capacity to change something about it. Staffing shortages represent a major issue across the environmental line administration, making it difficult to meet all mandated tasks. At the same time, financial resources are insufficient to address these gaps. While outsourcing is often seen as a solution, it frequently results in a loss of expertise and control, jeopardizing other critical tasks and requiring delegation and monitoring capacities that many implementation authorities lack (GER32; GER17; GER33; GER29; GER36). While higher level authorities are aware of the problems at WWAs and District Offices, they are themselves too overstretched to provide proper support and shoulder their responsibilities toward subordinate authorities. As a result, challenges cascade from top to bottom, making the German environmental administration, and particularly the local authorities, increasingly vulnerable to overload.

Social Administration: Resilience in One, Vulnerability in Many

While environmental policy administration in Germany is heavily shaped by federal structures, facilitating blame-shifting, social policy administration, in contrast, is characterized by self-administered central agencies – such as the BA and DRV – with regional branches and local offices. While this structure generally increases the federal government’s risks to face the political costs for implementation failures, key differences exist between implementation bodies.

Within the DRV, the federal umbrella organization (DRV Bund) is supervised by the Federal Social Insurance Authority, while regional pension insurance institutions fall under the legal supervision of their respective state social ministries (Eichenhofer et al., Reference Eichenhofer, Rische and Schmähl2012). This structure allows the federal level to deflect some responsibility. In contrast, the BA is more directly connected to the federal government, with the Federal Ministry for Social Affairs being in charge of its legal supervision and partially monitoring implementation success and resource allocation (Boeckh et al., Reference Boeckh, Benz, Huster and Schütte2015; Brussig, Reference Brussig, Liebig, Matiaske and Rosenbohm2017; Trampusch, Reference Trampusch2002; Weise, Reference Weise2011). Interviewees acknowledge support from the ministry and note that blame is rather rarely assigned, as higher level authorities are generally aware of the complexities involved in implementation (GER05; GER14).

However, when federal structures introduce shared responsibilities, blame-shifting opportunities for federal policymakers increase significantly. First, in Jobcentres, local authorities and local employment agencies jointly manage benefits under the basic social security scheme (SGB II), resulting in overlapping supervisory responsibilities between state and federal levels. Second, in areas such as child and family benefits, the Länder manage federal social assistance policies (e.g., parental benefits) and provide advisory services. Implementation often overlaps with state-level initiatives, such as Bavaria’s family allowance, which is also administered by the ZBFS.

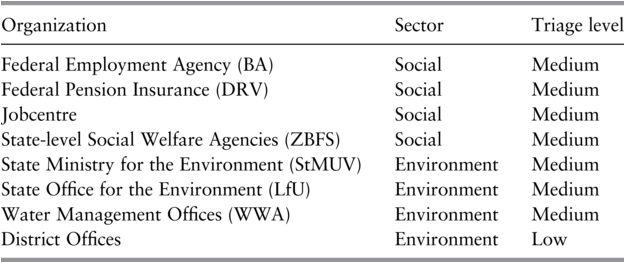

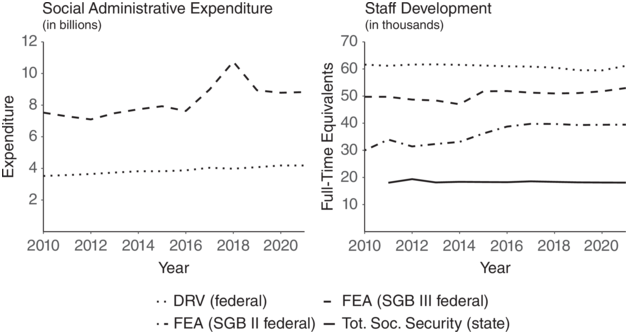

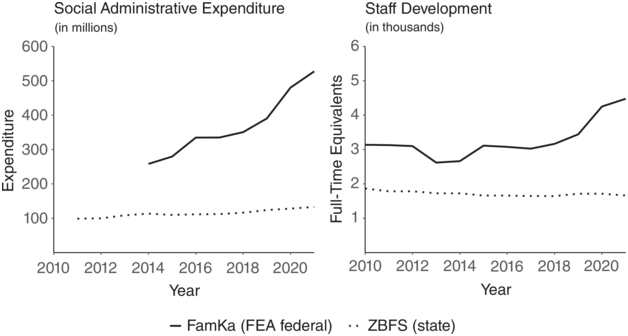

Organizational differences in vulnerability to overload become particularly evident when assessing the ability of implementation bodies to mobilize external resources. The BA stands out as a success story, demonstrating assertiveness and leadership, while other implementation bodies face greater challenges in resource mobilization. Figure 5.5a and 5.5b illustrates the development of staff and administrative expenditures across implementation bodies, underscoring these disparities.

Figure 5.5a Development of social administrative expenditure (without policy costs) and staff at the FEA, DRV, and total social security staff (Bavaria).

Figure 5.5b Development of social administrative expenditure (without policy costs) and staff at the FamKa and ZBFS.

The BA is primarily funded through employer and employee contributions to unemployment insurance (SGB III) and (mostly) federal tax revenues for basic social security for jobseekers (SGB II). Additionally, the federal government reimburses the BA for extra tasks, such as managing child benefits through FamKa. In practice, this means policy costs are rarely a concern for the BA: “If necessary, the federal government will just have to come up with some special funds” (GER03).

Politically, the BA is well positioned. It enjoys strong ties with the government (GER05; GER02; GER14; GER03) and maintains effective internal communication, enabling it to design appropriate budgets and ensure high-quality implementation (GER06; GER05; GER04; GER03; GER14). Staffing resources are also relatively secure, with few complaints from BA divisions: “I do get asked beforehand: how much do you estimate you need? That is taken into account […] We have not been limited in recent years. We are relatively generously endowed as far as the inclusion budget is concerned” (GER03). Also in the field of employment promotion (SGB III), the regional directorate can respond “flexibly […] both in terms of staff allocation and with regard to the allocation of funds” (GER02).

As a result, the BA, with its strong focus on efficiency and profitability, has built considerable resilience to overload. This capacity has been repeatedly demonstrated during extraordinary challenges, such as the refugee crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, which the BA managed effectively (GER02; GER14; GER03). These successes have further solidified the BA’s relationship with the political level, described by one interviewee as a “close alliance” (GER03).

Jobcentres, the joint facilities of the BA’s local employment agencies and district administrations, are more vulnerable to overload. Although the federal level covers 84.8 percent of administrative costs (§ 46 SGB II), resource constraints remain a persistent challenge: “At the Jobcentre, resources are an issue. They do not grow with the tasks. We never know what financial resources we’ll have available next year” (GER10). While Jobcentre executives have significant discretion over budget use, they still require approval from a local board composed of representatives from the employment agency and district administration (GER03; GER11). In urgent situations, however, boards usually provide support, as seen during the refugee crisis or the implementation of the Participation Opportunity Act (Teilhabechancengesetz) (GER18; GER11; GER04). These ongoing challenges – stemming from “systemic pressure” and “too limited budgets” (GER05) – are further amplified by the Jobcentres’ high visibility and significant societal impact (GER05; GER11).

The remaining social policy implementation bodies, the DRV and ZBFS, are even more notably vulnerable to overload. While coordination within the DRV generally functions well (GER20), it operates under a rigid and predetermined financial framework. Although primarily funded by contributions, federal grants account for a significant 30 percent of statutory pension insurance expenditures (DRV, 2024). However, the growing volume, complexity, and density of tasks far exceed resource growth (GER19; GER30). As highlighted by Adam (2024), German policymakers enacted twenty-one laws between 2011 and 2019 that impacted the operations of the Retirement Insurance. These legislative changes resulted in additional implementation burdens for the Retirement Insurance, costing between approximately 13.3 million EUR (under the most conservative estimation) and 59 million EUR (under the least conservative estimation) in administrative work. This workload is equivalent to employing between 261 and 1,157 full-time employees, based on average labor costs of around 51,000 EUR per employee during this period. Despite creating work that required more personnel, the Retirement Insurance actually experienced a reduction of 1,356 full-time equivalent administrative positions between 2013 and 2019, representing about 3 percent of its total 2013 workforce in full-time equivalents. As a result, the DRV faces both budget and task pressures without sufficient political leverage to advocate effectively for its needs (GER30). The situation is further complicated by the divergent interests of the sixteen regional pension insurance institutions and the challenges local pension administrators face when collaborating with other authorities. Even when the DRV unites behind a common goal, political success is uncertain. For example, despite collectively lobbying for additional resources to implement the newly introduced basic pension (Grundrente) – described by interviewees as an “administrative monster” (GER19; GER20) – the DRV only achieved to secure a few temporary positions for its implementation.

The ZBFS, the Bavarian social welfare agency, represents the most severe case of overload vulnerability, particularly in its capacity to mobilize external resources. Since its establishment in 2005, the agency has faced significant downsizing (BayORH, 2013), with only a modest increase in staff in 2019. This downward trend persists despite a growing workload driven by federal initiatives (e.g., Elterngeld Plus, a parenting benefit) and state programs (e.g., Bayerisches Familiengeld, a family benefit). At the federal level, the ZBFS, along with other state welfare agencies, struggle to effectively advocate for its needs (GER26). For instance, despite lobbying efforts through the Bundesrat to secure federal funding for the administrative costs associated with Elterngeld Plus, these attempts have been unsuccessful (Deutscher Bundestag, 2014).

In summary, the vulnerability of implementation authorities to overload differs significantly between the social policy and the environmental administration. In the environmental sector, disparities are primarily hierarchical: Higher level authorities (StMUV and LfU) are significantly better equipped to mobilize resources and prevent overload compared to local authorities (WWA and District Offices). In social policy, however, these differences cut across administrative levels. The BA stands out as a success story, in contrast to the Jobcentres, DRV, and state-level social welfare agencies. The BA’s effective combination of centralization, political oversight, and New Public Management principles (Brussig, Reference Brussig, Liebig, Matiaske and Rosenbohm2017; Weise, Reference Weise2011) have enabled the BA to navigate implementation challenges more effectively, while the other agencies seem comparatively neglected and more vulnerable to overload.

5.3.2 Overload Compensation in German Public Administration

As outlined earlier, implementation organizations often face structural disadvantages in competing for limited resources. Without sufficient political clout to assert their needs, they are prone to chronic underfunding and vulnerable to overload. While many organizations struggle with resources to meet their mandates, “soft” resources – such as high levels of policy ownership or an impact-oriented organizational culture – may help them to compensate for the mismatch between resources and tasks.

Environmental Administration: When Motivation Turns Into Frustration

In the environmental sector, higher level implementation authorities, the StMUV and the LfU, exhibit relatively high levels of policy ownership and an impact-oriented organizational culture. Many officials bring personal commitment to their work, often sitting on environmental committees and engaging in private environmental protection efforts. Their professional backgrounds, primarily in fields such as biology or hydrology, further reinforce a shared esprit de corps. As one interviewee notes: “The environmental engineers are a very tight-knit bunch. They all have somehow completed their additional training together. Some of them have known each other for thirty years. There’s a community spirit there. In the legal field, not so much” (GER37). Both organizations also work to enhance policy effectiveness by exploiting digitalization, restructuring, and flexibilization (GER21; GER23; GER24; GER13; GER17; GER25). Internal digital networks have been created to pool expertise across institutions (GER24), and a strong sense of professionalism supports high levels of motivation. This commitment often translates into overtime work: “There have even been night shifts. The colleagues working on the Habitats Directive, in particular, are accustomed to a high level of pressure. There were times when weekend work was regularly required to get everything up and running on time, despite its complexity” (GER25). Overall, these efforts illustrate how the StMUV and LfU leverage their organizational culture to manage overload and sustain effectiveness as much as possible.

At the local level, however, overload compensation is less effective as policy ownership is substantially less pronounced. While many employees are deeply committed to environmental protection, this very dedication makes them vulnerable to exploitation: “Many employees identify very strongly with the task. It’s easy to exploit people like them” (GER32). At the same time, and unlike their higher level counterparts, local authorities lack the capacity to improve efficiency. Tasks are often too specialized to allow for flexible personnel deployment or expedient outsourcing (GER35; GER36; GER33) beyond activities such as emission measurements and issuing expert opinions (GER36; GER34). Moreover, outsourcing would deprive local administrations of essential expertise and reduce their ability to respond effectively to local problems (GER29; GER33). Finally, digitalization is often perceived as an additional burden rather than a driver of efficiency. Expectations for digital implementation frequently do not align with local realities:

It sounds tempting: I have a probe somewhere that transmits the values remotely to a computer. […] The idea is that all the data is available at the push of a button. But that’s not the reality. It starts, for example, with […] the mobile network not working properly. […] Everybody thinks programming a new application is a universal solution, but then it crashes or freezes….

Social Administration: Diverging Capacities for Overload Compensation

In the social policy sector, differences in overload vulnerability extend to the ability of various organizations to compensate for workload peaks. The BA and its different units fare far better than the DRV or the ZBFS. This divergence is not necessarily linked to differences in employee motivation but rather to institutional structures and their capacity to channel employee aspirations into meaningful compensation mechanisms.

The BA exemplifies strong policy ownership and a results-driven organizational culture. Employees across all levels consistently prioritize their mission of helping those in need, emphasizing efficiency and simplification of legislation (GER03; GER05; GER14; GER11; GER09; GER10). “There are quite a few points where we say, ‘Gee, this could be made even simpler’. We could save resources, and it would be more understandable to the citizens” (GER03). While the BA occasionally faces workload peaks, particularly driven by economic developments and crises, its internal mechanisms enable flexible responses. Digital tools, highly accepted across the organization, facilitate adaptive workflows and flexible staff deployment through a “cascading procedure” (GER04) in which employment agencies assist one another based on local needs (GER04; GER03). This routine of staff rotation based on local needs is largely regarded as effective (GER04; GER03; GER06; GER07; GER14). Finally, the organization benefits from well-regarded training measures and a supportive hierarchical structure, where upper levels take responsibility and protect and support the lower levels (GER04; GER15; GER10; GER05; GER14). These BA practices further strengthen staff motivation and commitment, encouraging them to push their limits when necessary (GER05; GER14).

The Jobcentres also profit from their affiliation with the BA. Positive trickle-down effects extend to Jobcentres’ implementation structures, IT infrastructure, and leadership culture (GER10) increasing their ability for overload compensation. At the same time, Jobcentres remain more constrained in their compensatory capacity due to high staff turnover, rigid budgets, and challenging cooperation dynamics with municipalities and District Offices (GER05; GER10; GER11; GER05). As one interviewee describes it, their operations often follow the logic of “robbing Peter to pay Paul” (GER05), resulting in decreased motivation and lower levels of perceived discretion.

In contrast, the DRV and the ZBFS face much greater challenges in compensating for overload. However, this is not because their employees do not feel attached to the policy purposes or are not motivated. In fact, the opposite is true (GER30; GER19; GER20; GER26; GER27; GER31). Instead, these organizations lack the necessary fallback options to manage overload. As for the DRV, rigid structures and a lack of flexibility prevent even minimal adjustments to respond to fluctuations in local workloads. Team sizes have been reduced to the point where even a single absence – such as a holiday or sick day – becomes unmanageable (GER30). Furthermore, employees are confined to narrowly defined roles within their teams, with little capacity to support colleagues:

For procedural reasons, you are only approved for one team. For example, I work on Day 10 [an internal system for assigning responsibilities]. If there is a crisis in the team of Day 9, I cannot step in, even if I wanted to. […] I do not really understand this because we all took an oath, and we’re all part of the same organization, even the same unit.

In addition, the DRV faces similar challenges to those experienced by local authorities in the environmental sector: The DRV lacks the capacity to create additional capacity, especially with respect to digitalization (GER19; GER20). Consequently, the organizational culture is negatively affected, with reforms and rule growth gradually reducing employees’ confidence in the “good” purpose of their jobs: “We do have a high administrative burden, but in fact almost nothing comes out of it for the pensioners” (GER30). Some employees also experience a “guilty conscience” (GER19) toward pensioners or, given the high level of administrative complexity, are afraid of making mistakes that could harm them. To cope, strategies, such as overtime, have become routine, as increasingly “thinner-skinned” (GER30) and “frustrated” employees push “endless overtime and vacation days” (GER19).

Lastly, the ZBFS is arguably the least equipped to compensate overload. Structural deficiencies and only volatile support from political and administrative leadership at the federal and state level have left local divisions to manage on their own (GER27; GER26; GER31). Disregard or misunderstanding for operational realities and superficial responses to personnel shortages have fostered dissatisfaction and insecurity. As one executive states:

Every time there has been a change in the federal government, the new Family Ministry has thought it had to reinvent the wheel. There has always been something new. To put it bluntly, people are fed up, they’ve had enough.

Instances of temporal but severe personnel shortages, for example, were ignored and addressed only with superficial coaching measures. One local executive even offered his resignation to underscore the untenability of his position (GER27). Although the ZBFS offers little in terms of overload compensation through flexible management or efficiency gains, local divisions make concerted efforts to support one another at the team level, driven by a shared commitment to the underlying policy goals (GER31; GER27).

5.4 Treading in Deep Water: Policy Triage in Germany

The analysis of organizational capacities to reduce and compensate for implementation bodies’ vulnerability to overload presents a nuanced picture of German public administration. While overload is a recurring and significant theme in the interviews, the frequency and severity of policy triage vary across levels of government and policy sectors as demonstrated in the following sections. Yet, clear signs of escalation suggest that this phenomenon could intensify in the future due to legal and bureaucratic challenges.

5.4.1 Environmental Administration: Cross-Level Dynamics of Policy Triage

In the environmental sector, Section 5.3.1.1 highlighted that vulnerability to overload is primarily characterized by variation between higher and lower administrative levels. The decentralized structure of environmental administration fosters significant blame-shifting: Federal policymakers often deflect responsibility to Länder and local authorities, while state and municipal officials redirect blame to federal bodies or EU regulations. Higher level authorities, such as the StMUV and LfU, are better positioned to secure resources due to their political influence, yet their reliance on temporary, project-based funding constrains long-term capacity building. In contrast, local authorities, including WWAs and District Offices, face persistent resource shortages driven by rigid funding formulas and competition with other local government functions. While higher level bodies employ digitalization and restructuring to manage overload, they continue to rely heavily on overtime. Local authorities, with insufficient staffing, limited flexibility, and poor coordination mechanisms, face even greater challenges in addressing growing demands effectively.

This variation in overload vulnerabilities is mirrored in policy triage, with significant differences between higher and lower levels of government. While policy triage is evident, it remains moderate overall: The frequency of triage is moderate, and its severity relatively low, as mandatory tasks – particularly those tied to immediate political or legal consequences – are generally fulfilled. However, a reactive logic appears to guide resource allocation decisions at the political level: Once potential penalties – such as electoral losses or EU infringement procedures – become imminent, resources are released, and positions are filled. Conversely, discretionary tasks, which are equally critical for achieving national environmental policy goals, are more frequently neglected or abandoned. For instance, the LfU discontinued its in-house emissions measurement activities in favor of emission trading tasks, which were deemed more politically urgent (GER23). This difficulty in addressing crucial but nonmandatory tasks is also highlighted in an independent study by Germany’s federal environmental protection agency, which surveyed enforcement authorities across all sixteen German Länder (Ziekow et al., Reference Ziekow, Bauer, Keimeyer, Steffens, Herrmann and Willwacher2018).

A closer examination of different administrative levels highlights fewer pressures for policy triage for the StMUV and LfU, the higher level authorities. While triage activities become more frequent, their immediate severity remains comparably low, since they are mainly directed at tasks of long-term planning, legal coordination, or nonmandatory tasks. For example, implementation guidelines are issued too late to be useful for enforcement authorities (GER37), or inconsistencies in laws and regulations are sometimes left unaddressed (GER16; GER21). The regular postponement of duties without strict deadlines represents another notable instance of moderate policy triage. This de-prioritization affects not only routine tasks but also the authorities’ own projects, which are known to boost employee motivation and morale (GER25; GER34; GER17; GER32; GER25; GER13). As a result, the higher level authorities risk devolving into reactive institutions, consumed by administrative missteps and neglecting broader environmental objectives (GER21; GER24; GER17). Also, the regular deferral of internal priorities diminishes the coordinating, moderating, and guiding roles of the StMUV and LfU, especially in relation to their subordinate authorities, further weakening the overall coherence and effectiveness of environmental governance (GER13; GER38).

With regard to the local level authorities, in contrast, policy triage decisions driven by task overload are more concrete and their consequences more tangible: District Offices and WWAs have increasingly neglected certain regular tasks. While the extent of such triage decisions varies depending on local staffing situations and specific problem configurations, a consistent pattern emerges: Supervisory and monitoring tasks are increasingly falling behind, especially when they are politically unpopular or involve extensive follow-up obligations and potential disputes (GER32; GER13). Follow-up monitoring of granted permits and ancillary provisions (GER35) are also subject to triage decisions. Additionally, the threshold for intervention in routine control activities has shifted. Local authorities often postpone action until external triggers – such as police reports – generate sufficient pressure to justify administrative involvement (GER29). Beyond delays, the scope and quality of implementation activities have also been compromised due to persistent overload. Implementation requirements are frequently unmet, and the depth of investigations has declined (GER32). In some cases, local offices adopt a “quick and dirty” approach: “Here [at the WWA], it’s more along the lines of ‘put the lid on’ and get rid of it” (GER29). This decline in standards is further exacerbated by the growing complexity and detail of regulations (GER33), often criticized as unreadable, incomprehensible, and impractical (GER29; GER33; GER36; GER37; GER35). The resulting strain is reflected in heightened frustration, higher turnover rates, and rising burnout among employees (GER32; GER13).

Finally, discretionary yet essential tasks are also increasingly neglected at the local level, with far-reaching consequences. For example, local authorities find it increasingly difficult to engage in constructive dialogue and offer advisory support to private stakeholders and municipalities (GER13; GER33; GER29). These functions are critical in environmental policy, where effective implementation relies on collaboration among multiple actors. However, these coordinative efforts often encounter resistance, as they are perceived as intrusive – particularly in cases involving property rights or other sensitive issues. Thus, at the local level, we observe a medium frequency of triage decisions, but with higher severity due to the more critical nature of the tasks affected. The outcome is a notable decline in the scope, quality, and collaborative effectiveness of local environmental governance.

5.4.2 Social Administration: Diverging Patterns of Policy Triage

In the social sector, the Section 5.3.1.2 highlighted that vulnerability to overload is primarily characterized by variations across agencies. The BA is well-resourced, with strong oversight, flexible staffing, and effective digital tools, making it highly resilient. Jobcentres benefit from BA support but face resource shortages, high staff turnover, and blame-shifting due to shared responsibilities. The DRV struggles with rigid structures, insufficient resources, and employee frustration, while the ZBFS faces the most severe challenges, including downsizing, weak political support, and limited capacity to compensate for overload.

As a result, policy triage reflects the heterogeneity across agencies, with its frequency and severity varying significantly between organizations and departments. These variations align with the previously identified differences in overload vulnerability and compensatory capacities. Although most authorities assert that they can still manage their core tasks, the scope and intensity of the challenges they face differ considerably.

Due to its low overload vulnerability and high compensation capacity, the BA’s administrative and implementation apparatus experiences no structural policy triage beyond routine prioritization activities. Even amid the pressures of multiple crises, the organization remains on track: “We no longer have these times where we had to follow the ‘mass instead of class’ principle. […] Fortunately, we have moved away from it” (GER04). Employees and executives consistently report that they can manage their workload effectively, crediting the BA’s present management and leadership culture as a key factor in maintaining operational resilience. Thus, in the case of the BA, policy triage is effectively absent, with a very low frequency and low severity of task neglect.

While the BA demonstrates low levels of policy triage, the situation is more varied for other social policy authorities. Within the Jobcentres, in some departments – such as the employment services – policy triage is largely absent, with tasks being managed effectively and without significant neglect. However, other departments, particularly those responsible for providing basic security, are increasingly resorting to policy triage albeit at moderate levels: Time-consuming tasks and judicially critical cases, such as refund claims (GER11), are regularly de-prioritized; trade-offs in data quality and documentation commonly occur as part of these decisions (GER10; GER05). Furthermore, the Jobcentres’ departments for benefit provision face growing challenges and are calling for administrative simplification: “The concern is that we simply cannot handle the workload anymore. […] And if we do, I’ll burn my employees. […] Everyone is willing to work harder, but that’s not the point at all. It always has to be manageable” (GER10). Although overload vulnerability is high, Jobcentres are still widely able to cope due to their considerable compensation capacity. As a result, the frequency and severity of triage remain overall low to moderate in Jobcentres.

A more concerning picture emerges in pension policy administration, where both the frequency and severity of the DRV’s triage pattern are comparatively higher. Although benefit provision tasks are consistently maintained, other legally mandated activities, such as account clarifications, are systematically neglected, resulting in significant backlogs: “All pension institutions have enormous backlogs” (GER19; GER30). Interviewees report widespread delays and quality losses: “No matter how much employees work, they always have backlogs, they always have a guilty conscience” (GER19). Despite these operational struggles, management appears to prioritize cross-sectional missions, such as data protection, which exacerbates the complexity of tasks and adds further pressure to the system (GER20). This focus on peripheral activities diverts resources from core responsibilities and highlights the DRV’s leadership challenges and limited capacity to absorb additional workload: “It must not continue the way it has developed over the last 10 to 15 years, either in scope or in complexity, unless we have a corresponding increase on the personnel side […] Right now, from my perspective, there’s no absolute danger yet, but we’re well on our way toward that deadline” (GER19). While the frequency of the triage is high and the overload pattern signals systemic strain, the affected tasks primarily fall in noncritical areas, resulting in a low to moderate level of triage severity.

The ZBFS experiences a relatively high frequency and severity of triage across its operations compared to the other organizations in the social sector. Overload vulnerability and limited compensation capacity sometimes leave the administration “completely on edge,” resulting in backlogs in regular business (GER27). Some employees express concerns for administrative failure in the future, while others describe the situation somewhat more optimistically as manageable “with efforts” (GER26). In response, executives and staff at times resort to stretching legal frameworks to enable pragmatic decisions (GER27), while others adopt a reactive approach, “proceeding according to what was received first…” (GER26). This pervasive overload creates “bow waves” of unmet tasks that persist despite attempts to minimize them (GER26). A particularly candid quote from an ZBFS executive highlights the pressures faced by the agency:

Thank God, it’s clear to everyone […] that the operating times at our site are gradually falling through the floor. […] If pressure were to build up as well, then I would no longer have any solution. […] And I’m actually glad that the numbers are hitting rock-bottom. I’m not allowed to say it out loud, and maybe it’s sarcastic, but I’m actually a bit glad when someone sends me a certificate of incapacity. Then it finally becomes clear that the conditions simply can’t go on like this in the long run.

Hence, for the ZBFS, the combination of high triage frequency and moderate severity reflects a challenging situation. While the agency continues to function, systemic overload poses risks to its long-term operational stability.

As a result, policy triage in the social sector can be assessed as moderate, with significant variation across agencies. While organizations like the Federal Employment Agency (BA) maintain low triage levels due to robust resources and adaptability, others, such as the DRV and ZBFS, face higher frequency and severity of triage, reflecting systemic strain and growing backlogs. Despite core tasks being largely upheld, the increasing demands cast uncertainty on the long-term stability of operations.

5.4.3 Outlook

The underlying patterns of prioritization and neglect point to a gradually intensifying challenge. Implementation authorities in both environmental and social policy are increasingly struggling to balance expanding workloads with static or insufficient resources. This imbalance poses risks to the long-term functionality of German public administration and democratic governance. As one interviewee observed:

We have lost the ability to tackle and consistently push through those things that have been identified as the right things to do. Instead, we are willing to engage in endless compromise to please everyone. […] Things have become so complex that one has to question whether there is still equality of arms between the executive and those who are governed.

While imbalances have already led to instances of policy triage – mostly minor but occasionally substantial, particularly for tasks considered less politically or legally critical – legal and bureaucratic challenges are compounding these issues. One interviewee describes the problem of individual case justice: “Someone thinks that he is treated unfairly and files a lawsuit. The judge says, ‘Yes, sir. The legislature or the administration did not regulate this properly,’ triggering an outrageous amount of bureaucracy” (GER03) and further burdening the system. As another consequence, implementers’ dependence on detailed regulations becomes excessive, as a street-level bureaucrat noted: “Over the years, implementers […] have been trained in such a way that clear guidelines are now necessary. […] When there is less regulation, there is a lot of uncertainty about decision-making” (GER10). Balancing rules and capacities turn into a vicious circle.

Overall, while patterns of policy triage remain moderate (see Table 5.1), clear signs of escalation suggest that this phenomenon could intensify in the future. “Typically German, we make life too difficult in some areas. We always want to prove and analyze everything down to the last detail” (GER33) – a mindset that may need to shift if implementation authorities are to manage these growing pressures.

| Organization | Sector | Triage level |

|---|---|---|

| Federal Employment Agency (BA) | Social | Medium |

| Federal Pension Insurance (DRV) | Social | Medium |

| Jobcentre | Social | Medium |

| State-level Social Welfare Agencies (ZBFS) | Social | Medium |

| State Ministry for the Environment (StMUV) | Environment | Medium |

| State Office for the Environment (LfU) | Environment | Medium |

| Water Management Offices (WWA) | Environment | Medium |

| District Offices | Environment | Low |

5.5 Conclusion

This chapter highlights the varied vulnerabilities to overload across Germany’s environmental and social policy administration, emphasizing both sectoral and organizational differences. While a healthy degree of prioritization is part of the business, especially from an economic and budgetary perspective, policy triage decisions become a more frequent problem across Germany’s implementation bodies. In nearly all the organizations studied and across levels of government, essential planning, coordination, and conceptual duties are increasingly disregarded due to the growing superposition with other tasks. Furthermore, the gap between policy formulation and actual implementation appears to be widening, resulting in frustrated and overworked public employees – factors that further exacerbate staffing challenges within the administration.

Regarding implementation bodies’ vulnerability to overload, the intricacies of the German federal system and its structural provisions for administrative authorities amplify the potential for blame-shifting. Variations in organizations’ levels, internal structures, and relationships with other actors result in differing capacities to mobilize external resources. These dynamics create significant differences in overload vulnerability across implementation bodies and levels. In the environmental sector, hierarchical disparities are particularly pronounced: Higher level authorities, such as the StMUV and LfU, are relatively better equipped to mobilize resources and maintain functionality, while the local authorities, WWAs and District Offices, face persistent resource constraints and increasing implementation burdens. These challenges are further exacerbated by their difficulty of sustainably managing and responding to overload, making local-level implementation particularly susceptible to policy triage. In contrast, the social policy sector shows significant variation across organizations, albeit consistently. The BA stands out as a unique success story, demonstrating both strong resilience to overload and an effective toolkit for managing implementation burdens. Meanwhile, the Jobcentres, DRV, and ZBFS illustrate the challenges of navigating complex administrative structures with limited resources and dim political leverage.

These systemic vulnerabilities are closely linked to variations in policy triage across different implementation bodies in both policy sectors. The frequency and severity of policy triage differ significantly among organizations. In the environmental sector, differences are primarily observed across administrative levels. For instance, the StMUV and the LfU exhibit medium-frequency policy triage with generally low severity. In contrast, District Offices and WWAs experience medium-frequency triage but with higher severity, which has led to a marked decline in the quality and collaborative effectiveness of local environmental governance. Variations in policy triage are less influenced by hierarchical distinctions between higher and lower administrative levels and more pronounced across agencies as both the frequency and severity of policy triage vary significantly across organizations and departments. The BA shows no structural reliance on policy triage. Similarly, in job centers, some departments avoid policy triage, while others are increasingly resorting to moderate levels. Notably, the ZBFS demonstrates a high frequency of policy triage, albeit with medium severity.

Overall, the findings suggest that while implementation bodies can still manage their core tasks, growing workloads, resource constraints, and limited compensatory mechanisms threaten to undermine administrative resilience. These pressures are particularly acute at the local level and in agencies with weaker institutional support. Addressing these challenges will require targeted reforms, including more efficient resource allocation, intensified intergovernmental coordination, and greater flexibility to adapt to evolving demands. Without such measures, the risks of systemic overload and more frequent policy triage decisions will likely escalate, jeopardizing the capacity of Germany’s administrative system to maintain its high standards of public service delivery.