Climate change is a significant threat to human health. 1 It is affecting emergency medicine practice through the increase in climate-related disease patterns and shifts in epidemiology for conditions diagnosed and treated in emergency departments (EDs), such as an increase in vector-borne and zoonotic diseases, heat-related illness, and exacerbations of chronic respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.Reference Sorensen, Salas and Rublee 2

Studies have shown that extreme heat events correlate with increased ED attendancesReference Paganini, Valente and Conti 3 from heat-related disorders and exacerbations of chronic conditions such as asthma and congestive cardiac failure,Reference Patel, Conlon and Sorensen 4 , Reference Mason, King and Peden 5 and higher in-ED and in-hospital mortality rates.Reference Paganini, Valente and Conti 3

Studies also showed that most health care workers believe that climate change has already adversely impacted patient health,Reference Kircher, Doheny, Raab, Onello, Gingerich and Potter 6 with the aging population being a contributing factor.Reference Herrmann and Sauerborn 7 Health care workers feel more training on recognition and management of heat emergencies is required as they feel underprepared,Reference Khan, Ahmed and Naeem 8 and systems-level preparation ranging from public education, primary care, and infrastructure upgrades are required.Reference Khan, Ahmed and Naeem 8

Singapore is ranked 187/192 on the World Risk Index based on the 2022 World Risk Report. 9 This country has thus far been fortunate to be spared from disasters triggered by natural hazards such as earthquakes, typhoons, and volcanic eruptions. 10 There has been occasional flooding during heavy rain, without any reported impact on transport systems or infrastructures.

However, temperatures are steadily rising. According to the Meteorological Service Singapore (MSS) past climate trends report, 11 continuous temperature records since 1948 show that the island has warmed, with mean surface air temperature rising by an average of 0.25°C per decade between 1948 and 2023. 11 In 2023, the annual mean temperature was 28.2°C compared to 26.6°C in 1948. 11

Based on the Third National Climate Change Study V3 12 conducted by the MSS, the country is expected to become warmer, with annual mean temperatures rising between 0.6 and 5 °C by the end of the century. Exceedingly hot days, defined as exceeding the 99th percentile of daily maximum temperature over the 30-year period (1991-2020), 12 will also become more frequent: in the last 40 years, daily maximum temperatures exceeded 35 °C on 21.4 days per year on average, but 41 to 351 hot days per year are estimated by the end of the century. Warm nights, defined as temperatures exceeding the 90th percentile of daily minimum temperature over the 30-year period (1991-2020), 12 are also expected to rise from a yearly average of 76 in the last 40 years to most nights by the end of the century. 12

Currently, there are no published studies on the impact of heatwaves on the emergency health care system of Singapore, or on exploring the knowledge and perceptions of health care workers on the impact of heatwaves on EDs.

This study aims to fill this gap, also exploring potential strategies and solutions to improve the knowledge and readiness towards heatwaves and its impact on ED health care in this country.

Methods

Research Design

This study employed a qualitative methodology. Data collection was performed from August-November 2023 using semi-structured interviews. A qualitative methodology was adopted as qualitative methods are particularly useful to thoroughly explore the perceptions and attitudes of individuals.Reference Mays and Pope 13

Study setting

The study was conducted in Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH), a 795-bed general and acute care hospital, serving more than 550 000 people living in the northern sector of Singapore.

Research team and reflexivity

The study was conducted by a multidisciplinary team of researchers (MYWY, MP, LR, and MV) working in the field of emergency medicine, disaster medicine, global health, and humanitarian aid with previous experience in qualitative research. The lead author (MYWY) has limited experience with qualitative research and was coached by the other authors (MP, LR, MV) who have extensive experience in qualitative research. Researchers are aware of the influence their identities have in collecting, interpreting, and reporting the findings of the present study.

Participants’ recruitment

Researcher MYWY is an emergency physician working in KTPH ED. A convenience sampling method was used to recruit participants from researcher MYWY’s department. Participants needed to be either physicians or registered nurses with work experience in the ED. Specialist training was not required for both physicians and nurses. Staff were approached in-person and information on study aim, methodology and ethical implications were shared. Our sample size was not fixed in advance, as we intended to capture a wide range of clinical experience and specialist training for both physicians and nurses.Reference Sandelowski 14 Although we recognize that data collection is not an exhaustive processReference Dey 15 and conducting more interviews may have revealed additional information, our research team determined that data saturation was reached after 12 interviews due to a high level of repetition of important topics and themes, and we could not detect new themes.Reference Vasileiou, Barnett and Thorpe 16 A total of 14 participants were approached with 2 who declined to participate and no dropouts.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in English language by researcher MYWY in a private area of the ED office. The development of the interview guide (Appendix A) for this study was guided by the research objectives, comprising questions belonging to the following main domains: work experience and position of the participant, knowledge on Singapore disaster risk profile, perception of the impact of extreme weather events and heatwaves on emergency health care, current strategies implemented to counteract the impact of heatwaves on emergency health care, and recommendations to enhance emergency care preparedness. Inputs from the literature review of qualitative studies were considered in the development of the interview guide. Results of this study are reported in accordance with the COREQ guidelines.Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig 17 Interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim in Microsoft Word, allowing the researchers to familiarize with the data and detect saturation.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was performed following Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis method.Reference Braun and Clarke 18 Using constant comparison, we inductively identified themes closely following the 6 phases of thematic analysis to (1) re-read and write memos to familiarize oneself with the data, (2) generate a list of initial open codes, (3) search for themes by developing the initial codes into themes, (4) review themes by re-examining the data, (5) define and name themes, and (6) produce a framework by linking the relationships between the defined themes.

The process started with the researchers familiarizing themselves with the data to understand its breadth and depth. This enabled the identification of concise and meaningful sets of data which led to the formation of initial codes. These codes were then used to identify potential themes, which were then reviewed and refined to accurately reflect the data set and remained distinct yet cohesive this was followed by a deeper analysis where our researchers clarified the specifics of each theme and refined their definitions and names to ensure each theme was clearly expressed and supported by data. Finally, the themes were explored, and conclusions were drawn, providing a detailed account of the data.

Ethics approval

Research ethical approval was obtained from the National Healthcare Group (NHG) Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB) Singapore prior to the conduct of the study (DRSB Reference 2023/00626). The research team obtained signed written informed consent in English from all participants prior to the interviews. Every participant was given a unique study ID, and the participant’s anonymity was maintained. Data confidentiality was assured as all data was stored in a locker and only accessible to the study team. Once the interview recording was transcribed, the soft copy was stored in a password-protected folder and only accessible to the lead investigators. Before starting the interviews, the participants were reminded of information about the aim of the study and the interview process, as well as their right to withdraw from the study at any time without repercussion or penalty.

Results

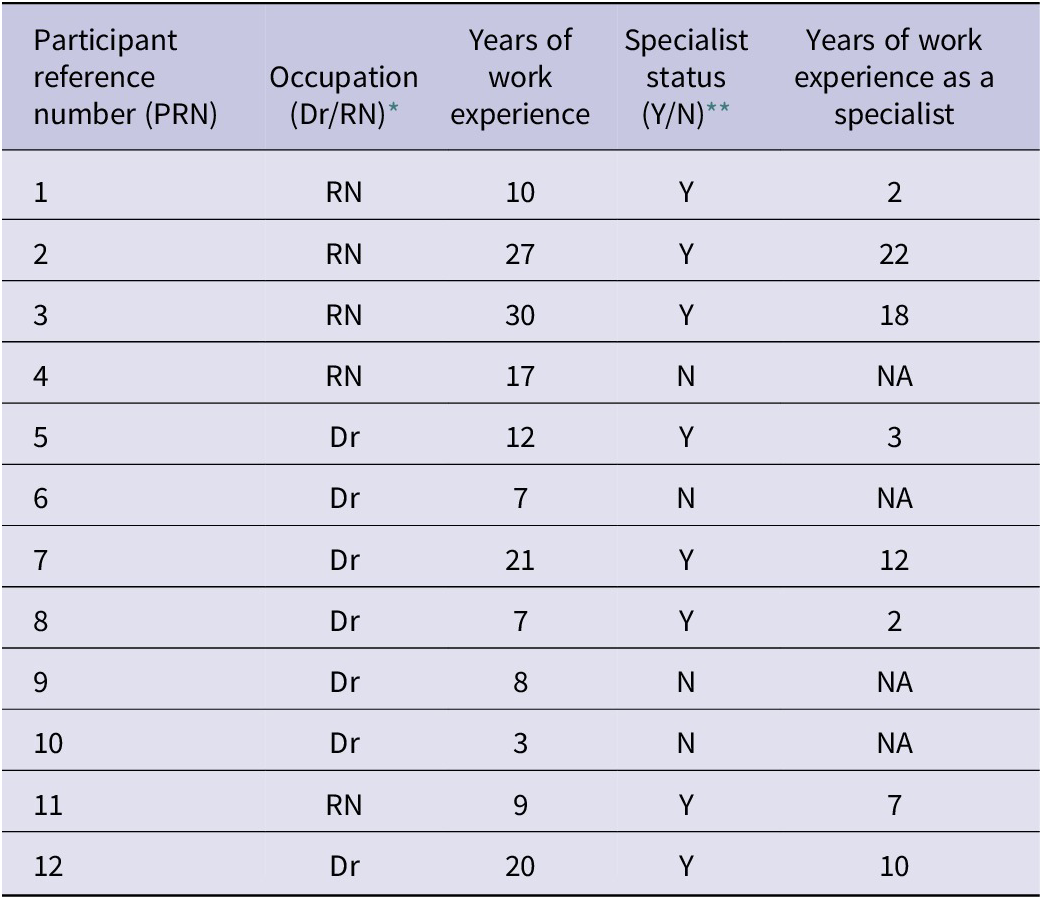

Twelve semi-structured interviews lasting between 30 and 45 minutes were conducted on 5 registered nurses and 7 doctors, with work experience ranging from 3-30 years. The characteristics of the participants (renamed PRN 1-12 for anonymity) are detailed in Table 1. All participants were general staff of the ED and able to work in all areas, from triage to resuscitation zones.

Table 1. Demographics and characteristics of participants

* RN: Registered Nurse, Dr: Doctor

** Y: Yes, N: No

Knowledge and Understanding of Extreme Weather Events

The US Department of Agriculture defines extreme weather as occurrences of unusually severe weather or climate conditions that can cause devastating impacts on communities and agricultural and natural ecosystems. 19 After performing a self-assessment, all participants admitted having limited knowledge of extreme weather events and being unfamiliar with any definitions, and were only able to describe between 2-5 examples, such as flooding, hurricanes, and tsunami. Specific to Singapore, all participants listed heatwaves as the most likely extreme weather event to occur. As other possibilities, 5 participants listed floodings and 1 mentioned tsunami.

Knowledge and risk awareness of heatwaves

Five participants rated their knowledge as below average, 6 as average, and 1 as above average.

None of the participants were aware of any official definitions for heatwaves, such as those by the World Meteorological Organization or MSS. However, 10 participants were able to describe the 2 main characteristics of a heatwave, which are markedly elevated temperatures and the extended duration.

“My understanding is that a heatwave is likely a significant elevation in the temperature of the day itself, over a period of time but I am not sure what the stipulated period of time is” (PRN 6).

Almost all the participants were aware of the adverse effects of heatwaves on health.

“An extreme increase in temperature causing more people to experience symptoms, due to this change in the weather” (PRN 5).

“A heatwave can be a temperature above normal for that area. It could be foreseen or unforeseen, which causes certain amounts of illnesses and effects to the human population that’s not used to that kind of heat” (PRN 7).

Ten participants acknowledged that Singapore is already experiencing the effects of climate change, but with the impression that there is no concrete impact on ED total patient attendances or diagnosis type.

“Not really. I don’t see high numbers of heat-related diagnosis, only a few which is not beyond the norm” (PRN 2).

“Not really. We are facing climate change but I can’t say for sure in terms of patient attendance as I have not seen a lot of heat-related illness” (PRN 1).

The remaining 2 participants felt that there is an impact, but it is gradual and not obvious.

“If it’s already happening, I think we’re lucky enough that it’s gradually happening” (PRN 7).

Impressions of increased vulnerability to heatwaves

All participants shared that those who work outdoors - such as construction workers or soldiers-in-training - and those at the extremes of age would be most vulnerable to the adverse effects of heatwaves. Only 3 participants identified having a single significant or multiple medical conditions as a vulnerability factor.

“Extremes of ages, elderly and the young, who are unable to care for themselves in the event of these severe weather changes. Certain populations who are also pre-disposed to the effects of heat, especially in Singapore’s context, would be our migrant workers who work mainly outdoors, and our conscripted personnel in the armed forces, due to prolonged exposure in the sun due to the nature of their activities and work, creating an increased risk of heat related illness” (PRN 6).

“Yes, those who are bedbound and those who need more assistance in activities of daily living, those who can’t articulate that they are feeling hot or who don’t have easy access to water to drink” (PRN 2).

All participants felt that dehydration or an inability to adequately self-hydrate is a risk factor for developing heat-related illness.

“Everyone will be affected, but elderly who are frail and weak are at higher risk. Anyone who must do work outdoors. Young ages who are unable to express themselves and communicate” (PRN 3).

One participant described a lack of heat acclimatization and wearing inappropriate heat retaining clothing as a risk factor for heat-related illness.

“…lack of acclimatization to heat and high temperatures, what the person wears and whether it is appropriate clothing or excessive clothing…” (PRN 10).

One participant described socioeconomic status and access to resources as a risk factor.

“Certain social economic statuses may not have the education to know what needs to be done to protect themselves… and even if they have the education, they may not have the access to resources to apply the knowledge” (PRN 7).

Preventive measures for acute heat related illness

Hydration and shelter. All participants listed adequate hydration, easy access to drinking water supply and sheltered areas, and access to cool areas such as air-conditioned environments as protective measures against developing heat-related illness.

Education and early recognition. Half listed education for the public on personal protective measures to prevent heat illness and how to recognize early symptoms.

Sheltered breaks and work-rest cycle. Three participants mentioned having adequate breaks during outdoor work or proper work-rest cycles.

“…Take a break, especially if working outdoors. There should be a limit in duration of exposure to heat” (PRN 12).

“Regular breaks from being out in the sun. Knowing how to recognize the signs of heat exhaustion and seeking help earlier” (PRN 5).

“Easier access for public to drinking water and shelter or air-conditioned areas… identify locations of higher risk of heat-related illness” (PRN 8).

Systems and policies. Only 1 participant mentioned the value of having established polices to allow preventive and protective measures at a systemic level.

“Institutional policies will be important as well as guidelines to prevent heat-related illness and measures to recognize individuals who exhibit signs of heat-related illness” (PRN 7).

Heatwave impact on the emergency department

Patient volume. All participants believed that a heatwave would cause rises in total ED patient attendances, and this would be attributed mainly to patients suffering from heat illness.

Expanded differentials for diagnosis of patient symptoms: Two participants specified that heat could be a contributing factor and not the main cause of ED admission.

“Patients may come with symptoms masquerading as other conditions, but they are caused by the heat. For example, a patient with vomiting and diarrhea may be diagnosed as having gastroenteritis but may be suffering from heat-related illness” (PRN 7).

“I think there will be patients who come for pure heat-related illness such as high temperature. But there could be other manifestations of heat-related illness. Such as giddiness, headaches. Increase in falls in the elderly. This may all also present due to exposure to heatwave” (PRN 9).

One participant was concerned by potential ED presentation delays caused by heat, discouraging people to leave their homes.

“…patients would be concerned of moving around and therefore delay their presentation to the hospital if acutely unwell” (PRN 6).

No participant mentioned exacerbation of existing chronic disease as a potential cause of admission during a heatwave.

Capacity of medical care. All participants expressed concern there would be ED staff shortage in all professions during a heatwave. Reasons include higher patient to staff ratio, low staff morale, increased medical leave or family care leave, and fatigue. However, most staff expressed confidence in the ability of the department to cope with staff shortages as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hospital resources. All participants felt that at current state, there is insufficient specialized cooling equipment (such as cooling vests or blankets) to manage heat-related illness with a high volume of patients. However, most highlighted the hospital’s ability to rapidly recruit resources to face a sudden surge of patients. All participants had confidence that electricity supply would remain uninterrupted, and logistics and infrastructure support would be adequate.

Potential strategies and solutions

All participants perceived a scarcity of staff training and education on heatwaves heat stroke management. One participant identified complacency as a factor contributing to the lack of planned education.

“Nurses have had training for pandemic and also for civil emergency, but we have not yet had training for heatwave” (PRN 4).

“I would say it is because Singapore has never experienced a heat wave resulting in large numbers of patients with heat-related illness. This could be a sense of complacency, or possibly naivety that a heat wave may never happen” (PRN 6).

All participants felt that the lack of training and education is the main barrier hindering the department’s preparation towards the impact and consequences of a heatwave. All advocated for formalized lectures or asynchronous learning, followed by a simple practical exercise, including training on the use of specialized cooling equipment. One participant also highlighted the need to focus on less common knowledge, such as atypical presentations of heat illness. A few also asked for workflows or reference guides to be uploaded on the hospital intranet system.

“I think education and knowledge base is what would hinder us the most. If we have education as our prepared weapon, then we shouldn’t have any issues with taking care of patients that are here for heat-related illness” (PRN 7).

“… education, especially to inform on the less common presentations of heat-related illness such as altered mental state, which if missed, may lead to a high mortality” (PRN 7).

Most participants felt that more could be done to educate the public on self-care during hot weather, how to recognize symptoms and signs of heat-related illness, and when to appropriately seek care at the ED.

“The main barrier is still lack of education to both staff and public. The public may perform prevention measures to protect themselves against heat-related illness and avoid needing to come to hospital” (PRN 5).

“Public education or public awareness campaigns are important, but they must also be in languages that all can understand, especially the elderly” (PRN 6).

Discussion

The findings of this study highlight a knowledge gap on how heatwaves are associated with significant health morbidity and mortality. Retrospective analyses have consistently confirmed an increase in ED attendances during heatwaves across different countries, ranging from 2%-Reference Sun, Sun and Yang 2019%Reference Oray, Oray and Aksay 21 for total attendances. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted showed that a 1 °C increase in temperature was associated with a 2.1% increase in cardiovascular disease-related mortality, a 0.5% increase in cardiovascular disease-related morbidity,Reference Liu, Varghese and Hansen 22 a 2.2% increase in mental health-related mortality including completed suicide, and a 0.9% increase in mental health-related morbidity.Reference Liu, Varghese and Hansen 23 Participants also had limited understanding of how heatwaves add further burden to health care systems and its components, such as ambulance services. In a heatwave, demand for emergency ambulance services will increase, up to 4% based on time-series analysis from ChinaReference Sun, Sun and Yang 20 and up to a 50.6% based on a systematic review of Australian health service demand during heatwaves.Reference Mason, King and Peden 5 When investigating the perceived impact of heatwave on EDs, most participants believed only heat-related illness will increase in a heatwave. None were aware that there could also be a rise in morbidity and mortality for chronic disease.

Almost all the interviewed described their own self-assessed knowledge and understanding of heatwaves as below average or average at best. This is consistent with a qualitative assessment on ED health care workers performed in Pakistan,Reference Khan, Ahmed and Naeem 8 where participants were aware of a few risk factors for heat-related illness, such as extremes of age, inability to self-care, having pre-existing medical conditions, and exposure to environmental heat. However, very few participants were aware of other risk factors, such as socioeconomic factors, education level, and heat acclimatization.Reference Adnan, Dewan, Botje, Shahid and Hassan 24 They were also unaware of geographical location factors, such as living in proximity to hospitals or urban environments, or concurrent environmental factors, such as air quality.Reference Rahman, McConnell and Schlaerth 25 A full understanding of all risk factors is required to adequately prepare and mitigate risks during high heat periods. 26

We found that participants had a correct understanding that total ED attendances will tend to increase during a heatwave. However, their perception of the rise in attendance is mainly due to heat related illness, whereas it is all-cause attendances that are known to increase.Reference Sun, Sun and Yang 20 , Reference Oray, Oray and Aksay 21 This is important as the exacerbation of chronic diseases during heatwaves causes a rise in morbidity and mortality.Reference Arsad, Hod and Ahmad 27 An accurate understanding of the pattern of increased ED attendances could better prepare EDs to manage the higher volume. Staff may be properly educated to avoid bias towards pure heat related illness diagnosis, and equipment and resources can be prepared to face both exacerbation of chronic diseases and heat-related illness.

The findings also show that the staff of the investigated ED do not feel prepared to face the health impacts of a heatwave or a large influx of patients with heat related illness. The current state of education on heatwaves is reported as inadequate, consistently with qualitative studies performed on health care workers in the UKReference Brooks, Landeg and Kovats 28 and Pakistan.Reference Khan, Ahmed and Naeem 8 Training should immediately be planned and incorporated into routine staff education curriculum to address the gaps in staff education and knowledge and, in turn, raise the ED preparedness level. This may be in the form of lectures, asynchronous learning using e-learning platforms, and practical drills with simulation exercises. At an undergraduate and postgraduate level, medical education could be adjusted to improve foundational knowledge of health care professionals and address existing gaps in the current curriculum. More emphasis should be made to enhance the education on climate change and its related impacts,Reference Maxwell and Blashki 29 , Reference Finkel 30 disaster medicine, and response.Reference Algaali, Djalali and Della Corte 31

Recommendations

An extreme heat-specific mass casualty incident response plan should also be developed in Singapore. This is in-line with the recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) 32 and the United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) 33 to reduce vulnerability and human impact of extreme heat events. This will also enhance the level of preparedness, reduce response time, and improve morbidity and mortality for patients. 34

A comprehensive heat response plan for Singapore should be a multidisciplinary effort, requiring cooperation from clinical and non-clinical departments.Reference Bernard and McGeehin 35 The plan should include the following steps: (a) identification of all relevant parties with a chosen lead; (b) use of a consistent, standardized warning system activated and deactivated according to forecasted or prevailing weather conditions; (c) use of communication and education to all staff; (d) implementation of response activities targeting high-risk populations; (e) collection and evaluation of information; and (f) revision of the plan.Reference Bernard and McGeehin 35 Heatwave awareness campaigns and alerts are also critical elements to a heat response plan. Raising community awareness and public education on heat-related illness and prevention will contribute to reducing mortality.Reference Ebi, Teisberg and Kalkstein 36 , Reference Paganini, Lamine and Della Corte 37 The 4 main languages in Singapore are English, Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil.Reference Dixon 38 By using these main languages, outreach educational initiatives through targeted programming on radio and television, social media campaigns, advertising in housing estates, and grassroot community engagement would likely have greater coverage and be most effective in educating the population.Reference Cowper-Smith 39

Criteria to initiate response plans are varied, including threshold temperature; heat index, which incorporates heat and humidity; and a synoptic air mass method.Reference Sheridan and Kalkstein 40 -Reference Steadman 42 We recommend the use of Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) readings, which is internationally recognized and is a widely used heat stress indicator that takes into account air temperature, relative humidity, wind and solar radiation that could contribute to heat stress. 43 The National Environmental Agency of Singapore uses WBGT readings to guide recommendations on outdoor activities, and real-time readings are readily available at all times. 44

Limitations and Strengths

Given its qualitative nature, the study did not use formal power analysis to calculate the sample size. This potential limitation was mitigated by conducting interviews with sufficient duration and depth to comprehensively answer the research question and help ensure data saturation. Furthermore, current qualitative methodology suggests that twelve is the minimum number to achieve.Reference Sim, Saunders and Waterfield 45 Also, the sample represents different professionals working in the ED, with a wide range of years of experience and specialization status, enriching the results with a plurality of viewpoints.

Being a single-center, single-country study, the findings lack generalizability and may not be valid for other health care systems. However, as a pilot study, it is meant to quickly capture the current situation and guide further education, preparation, and research, which will include all the country’s hospitals as the next step, to generate country-wide recommendations and policies.

Conclusion

This qualitative study provides the first insights into the impact of heatwaves on EDs in Singapore. There is basic foundational knowledge, but much more can be done in terms of education and training of staff, especially in targeting the knowledge gaps identified in this study. There is also a need to increase awareness of heatwaves and their impacts on health and develop comprehensive heatwave response plans.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is the result of a study conducted in the framework of the Advanced Master of Science in Disaster Medicine (EMDM - European Master in Disaster Medicine), jointly organized by CRIMEDIM - Center for Research and Training in Disaster Medicine, Humanitarian Aid and Global Health of the Università del Piemonte Orientale (UPO), and REGEDIM - Research Group on Emergency and Disaster Medicine of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

Author contribution

MYWY, MP, MV: Conceived study idea and development of interview guide; MYWY: Performed interviews; MYYW, MP, MV: Data analysis and generation of themes.

All: Discussion of results and final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix A: (Interview Guide)