Introduction

Community-based data collection allows translational researchers to observe participant behaviors in their own environment and under real-world circumstances, reducing threats to contextual validity [Reference Phillips, Müller-Clemm, Ysselstein and Sachs1]. However, logistics of collecting such data are challenging. This is particularly true when the sample is low-literacy, low-numeracy, non-English speaking, and living in low-income conditions.

Accurate, complete, and culturally sensitive data collection practices are important for rigorous study of hard-to-reach populations. Lay health workers (LHWs; a broad term we mean to encompass, for example, community health workers (CHWs), consejeras, promotoras) are known to be successful in recruiting participants to clinical and translational research studies [Reference Varma, Strelnick, Bennett, Piechowski, Aguilar-Gaxiola and Cottler2]. Yet, even as their role expands [Reference Hohl, Thompson and Krok-Schoen3] to include research [Reference Taylor, Mathers and Parry4] LHW research training, supervision, and data collection skills are not well described and little is known about LHW perspectives about their role in research [Reference Varma, Samuels and Piatt5].

The data that do exist suggest that LHWs may have the potential to successfully contribute to data collection for research studies. For example, one study compared LHWs to health professionals in calculating an absolute cardiovascular disease risk score with a simple, non-invasive screening indicator [Reference Gaziano, Abrahams-Gessel and Denman6]. Of 42 LHW trainees in 4 LMICs, 42 were deemed qualified to do fieldwork. Across 4049 screenings, the mean level of agreement between these CHWs and health professionals was 96.8%. However, in a different study, n = 348 government-employed LHWs in Brazil completed a 20-item, multiple-choice quiz measuring reading, comprehension, and problem-solving for epidemiological research on people with disabilities [Reference Musse Jde, Marques, Lopes, Monteiro and dos Santos7]. Participants answered only 65% of questions correctly, but the training for these LHWs was not described. Another study from the same group compared data collected by LHWs who had received 10 hours of training to data collected by researchers [Reference Lopes, Monteiro and Figueiredo8]. It showed good level of agreement across 28 variables, but LHWs substantially underestimated the rate of disability. The authors suggest that moderating factors, specifically the level of burden of their clinical workflow, may effect LHW performance in research projects.

Thus, there is a need to understand LHW roles, skills, training, and supervision related to research activities [Reference Allen, Brownstein, Cole, Hirsch, Williamson and Rosenthal9]. We have become increasingly interested in developing the research skills of LHWs. We call LHWs trained in these methods lay health worker research personnel (LHR). Most academic research centers do not employ LHR, necessitating partnerships between the researcher and a community-based organization (CBO). The nature of these partnerships may also effect LHR performance and satisfaction.

The purpose of this paper is to describe two randomized trials involving researchers based in academia and LHR based at CBOs. For each study, we employed different methods to explore LHR in their research roles. The first study was called Community Health Workers Assisting Latinos Manage Stress and Diabetes (CALMS-D), a randomized trial of a group stress management intervention for Latinos with type 2 diabetes. For the LHRs working in CALMS-D, we (1) describe LHR training and supervision, (2) present independent observer reports of LHR fidelity to protocols, and, (3) report LHR perspectives on their roles as provided in qualitative, in-depth interviews. The second study, Diabetes Risk Reduction through Eat, Walk, Sleep, and Medication Management (DREAM), was a randomized trial that compared interventions to reduce diabetes risk among Cambodian American refugees with depression. For the LHRs working in the DREAM study we (1) describe LHR training and supervision, and, (2) report rates of missing data for behavioral measures and sensitive psychosocial self-reports along with supervisor subjective impressions of LHR cultural consonance. We conclude with a discussion of the unique value LHR bring to clinical and translational research and challenges to be considered in this work.

Study #1 Methods – CALMS-D

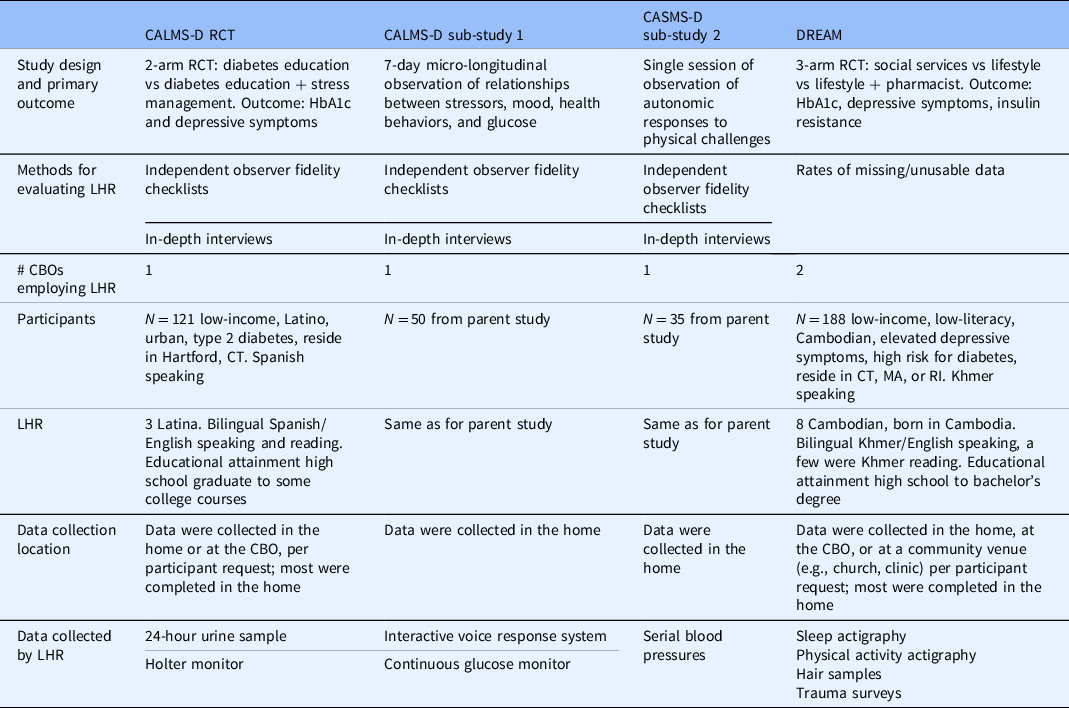

For CALMS-D (NCT01578096), two universities (Yale School of Public Health and UConn Health) were the lead organizations providing scientific direction, fiscal oversight, and reporting to the sponsor (NIH; Table 1). Recruitment occurred through an urban outpatient clinic associated with Hartford Hospital. LHR were employees of a non-profit CBO, the Hispanic Health Council. The position posting can be seen in the Supplemental Material #1. Two LHR were existing employees, and one was hired specifically for this study as an interventionist (who only conducted in-session data collection). The study coordinator was a bilingual, bicultural post-doctoral fellow who was employed by UConn Health and assisted in virtually all aspects of the study.

Table 1. Overview of CALMS-D and DREAM studies

CALMS-D = community health workers assisting latinos manage stress and diabetes; CBO = community-based organization; CT, MA, RI = Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island; DREAM = diabetes risk reduction through eat, walk, sleep, and medication therapy management; LHR = lay health research personnel; RCT = randomized clinical trial.

All CALMS-D procedures were approved by the UConn Health Institutional Review Board (IRB; #15-164-S) and there was an IRB reliance agreement between the IRBs of UConn Health, Yale University, Hartford Hospital, and the Hispanic Health Council. One of the Principal Investigators (RPE) had collaborated with the Hispanic Health Council and Hartford Hospital for decades, an important relationship for effective community-engaged research.

CALMS-D was a two-armed randomized trial among Latinos with type 2 diabetes comparing diabetes education vs diabetes education plus 8 sessions of group stress management psychoeducation [Reference Wagner, Bermudez-Millan and Damio10]. A sub-study [Reference Wagner, Armeli and Tennen11] of the parent trial used a 7-day micro-longitudinal design to observe the temporal unfolding of distress, diabetes self-care behaviors, glucose, and autonomic function. Another sub-study [Reference Bermudez-Millan, Feinn, Perez-Escamilla, Segura-Perez and Wagner12] used experimental physiological tasks (sit-to-stand, handgrip) to observe autonomic nervous system reactivity.

LHR Training

See Table 2 for LHR training details. Due to the relatively low educational attainment of LHR, their training followed guidelines of clear communications for teaching low-literacy learners [13,14]. For active skills, our principles included break up complex tasks into smaller steps; make sessions interactive and activity-based; encourage hands-on practice for supplies and equipment; use multimodal learning (written text, pictures, videos, slide shows, live practice); encourage questions; work in teams; take breaks; provide time for live practice in-session and in-between sessions; allow plenty of time to avoid a sense of time pressure; provide booster sessions; create a supportive, non-judgmental atmosphere where it is “safe to make mistakes”; and, positively reinforce participation in learning.

Table 2. LHR training in the CALMS-D and DREAM studies

For written training materials, principles included use text written at or below a 6th-grade level; use bulleted lists; use short sentences that are written in the active voice; chunk materials; give context before detailed information; use sized 10–14 font; keep the right margin jagged and not justified; place illustrations next to the related ideas in the text; use visuals (flow charts, diagrams) rather than paragraphs for complex ideas; use icons to summarize and communicate complex ideas quickly and easily; and, read aloud when possible.

In addition to the details in Table 2, we also spent time delineating specific roles, responsibilities, and expectations of the LHR as recommended [15]. For example, only one LHR, who was primarily an interventionist, collected data regarding perceived stress levels before and after intervention sessions. To help minimize confusion and avoid potential conflict, we also clarified the role and expectations for the LHR for other team members.

CALMS-D LHR were trained in research methods, human subjects protection, and data collection protocols. See Table 2 for details of training. LHR training was spread across several weeks with homework and practice between training sessions. Training included a manual loosely based on the interviewer training manual for the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [16] and the Puerto Rican Elderly Health Conditions project at the University of Puerto Rico [17]. (The CALMS-D manual can be requested from the author or found at https://health.uconn.edu/diabetes-research/community-based-research/). Training materials also included several online tutorials and interactive training sessions by the investigators. LHR were given checklists to follow for each measure, and, when participants needed to comply with instructions to complete the measure, LHR were given a simplified participant handout to review and leave with participants. The bilingual study coordinator (ABM) was centrally involved in all trainings. LHR also participated in role-play of data collection, including how to handle challenging cases.

Supervision

The lead investigator based at the community-based organization (SSP) oversaw the fieldwork and provided supportive supervision to LHR throughout the study. As recommended [15], supervision included frequent check-ins with LHR to discuss activities and workload; there was daily quality assurance monitoring of research activities, daily communication with LHR about their workday, and weekly planning of research activities and assignment of LHR staff to conduct activities. There was regular review of documentation and data; provision of feedback on progress and performance; identification of training and resource needs; discussion of issues or challenges, such as burnout; and, commending LHR for accomplishments. Depending upon the nature of the supervision topic, supervision included real-time problem-solving between the supervisor and LHR, or scheduled one-on-one meetings, group LHR meetings, site-specific meetings, and meetings of the whole study team. The group meetings allowed for peer support and exchange of ideas among LHRs and between LHR and supervisors as well as constructive feedback and problem-solving.

Systems and equipment used by CALMS-D LHR to collect measures are in Table 3. They included Remote Electronic Data Capture (REDCAP [Reference Harris, Taylor, Thielke, Payne, Gonzalez and Conde18]), an interactive voice response (IVR) telephonic survey system, a continuous glucose monitor, 24-hour urine samples, and a Holter monitor. LHR also obtained serial blood pressures during experimental challenges (sit-to-stand and handgrip challenges) as per Low 1993 [Reference Low19]. Investigators and their staff trained LHR (ABM, CB, JW) or oversaw the training (RL, RPE) and provided supportive supervision during the fieldwork (SSP).

Table 3. Details of home-based measures

CALMS-D = community health workers assisting latinos manage stress and diabetes; CGM = continuous glucose monitor; DREAM = diabetes risk reduction through eat, walk, sleep, and medication therapy management; IVR = interactive voice response; LHR = lay health research personnel; REDCap = Remote electronic data capture.

For example: “on a 3-point scale (1= “not at all” to 3 = “a lot”) did you …have pain, numbness, or tingling in your hands, legs or feet?.” Participants who did not own their own phone were provided study phones. All were provided headsets to facilitate hands-free keypad responding. Participants were provided with a “cheat sheet” of response options. IVR reporting windows were set for 8-10 AM and 8-10 PM. The IVR system called participants at random times during these 2-hour windows. If the call was unanswered, the system continued calling regularly within the time window. Participants could use a keypad response to indicate that they should be called back in 15 minutes. Postponed calls were permitted until the end of the reporting window after which the report was coded as missing.

To examine LHR fidelity to data collection procedures, an independent, bilingual observer completed protocol compliance checklists while observing LHRs who were instructing a subset of 7 CALMS-D participants (3 women & 4 men, 53–75 years old, Spanish speaking, low income, low literacy). Percent compliance with the checklists was used to ascertain degree of fidelity with each checklist which ranged from 29 items for IVR to 48 items for CGM (see supplemental material #2). Field notes of subjective observations were also reviewed.

To examine LHR perspectives, the same independent observer conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with LHRs. LHR interviews each lasting from 1.3h to 2h. Content analysis was used to analyze qualitative data [Reference Hsieh and Shannon20]. The Hispanic Health Council IRB approved the LHR observations and interviews.

Study #1 Results

CALMS-D Trial Participants

The n = 121 CALMS-D trial participants were 73% women, mean age = 60 (SD = 12) years old; most identified as Puerto Rican (71%), and nearly all preferred Spanish (93 %); 42 % reported eighth-grade education or less and 52% indicated their reading was “fair,” “poor,” or “cannot read at all.” The majority (58%) were unemployed due to disability. The sample is described in detail elsewhere [Reference Wagner, Bermudez-Millan and Damio21].

CALMS-D LHR

Among the n = 3 LHRs, age ranged from 38 to 61 years, they were all bilingual and bicultural (2 Puerto Rican, 1 Peruvian). All were high school graduates; one had some college, another was taking college courses, and the other was a certified nursing assistant. One was a certified Community Health Worker. They were all extensively trained and provided with mentoring supervision throughout the CALMS-D trial.

Direct Observation

In direct observation of LHR with actual participants, fidelity to protocols was > 95% for each measure (see supplemental material). The observer notes stated that LHRs were all clear, empathetic, and displayed a high degree of technical skill, self-confidence, and patience. LHR were also observed to be skilled listeners, able to establish a trusting relationship of mutual respect, and display an effective use of time and effective implementation of protocols during home visits.

In-Depth Interviews with LHR

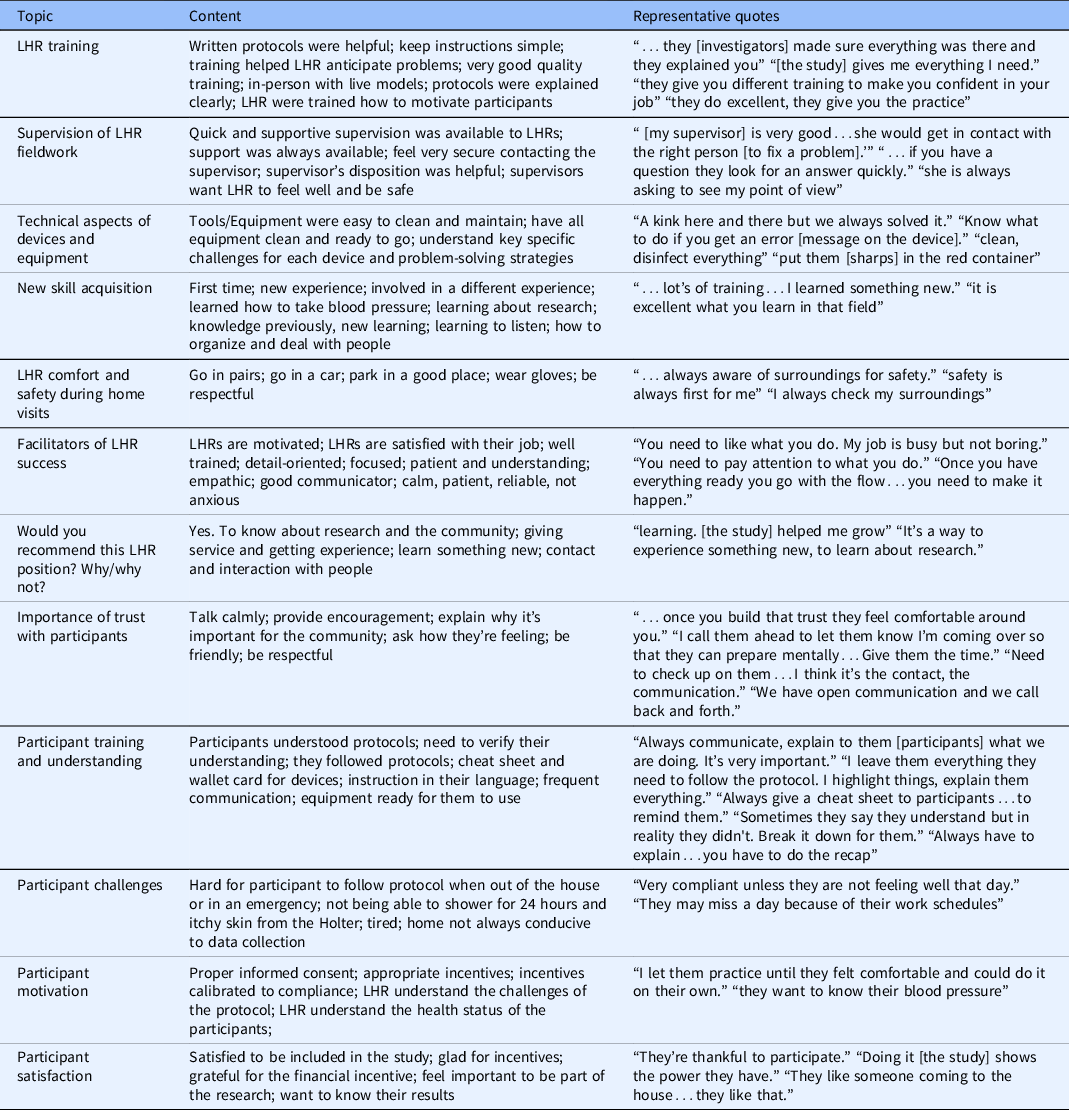

In interviews, LHR reported varying levels of challenge with each assessment but reported that the CALMS-D protocols, training, and supervision had been highly supportive and empowering. See Table 4 for topics, content, and representative quotes. LHR reported becoming very knowledgeable of the study protocols and successful at applying them: “A kink here and there but we always solved it.” They reported and feeling empowered to conduct their work: “it is excellent what you learn in that field” “they give you different training to make you confident in your job.” They reported feeling well trained: “…lot’s of training…I learned something new..” They appreciated supportive supervision “…if you have a question they look for an answer quickly.” “she is always asking to see my point of view.” Facilitators of LHR success included being highly motivated and satisfied with their job, being detail-oriented, well-focused, patient, empathic, safety conscious, and a good communicator.

Table 4. Topics, examples, and quotes from in-depth interviews with LHR in the CALMS-D study

Study #2 Methods – DREAM

For the DREAM study (see Table 1), UConn Health was the lead institution providing scientific direction, fiscal oversight, and reporting to the sponsor (NIH). Recruitment was through two non-profit CBOs, Khmer Health Advocates and the Center for Southeast Asians. The Principal Investigator (JW) had a longstanding, trusting relationship with Khmer Health Advocates which facilitated DREAM, again, an important relationship for effective community-engaged research. LHR were employees of one of these two CBOs. Some LHR were existing employees and others were hired specifically for this study. The position posting can be seen in the Supplemental materials. LHR conducted home visits for data collection. The study coordinator was a bilingual, bicultural employee of Khmer Health Advocates who assisted in many aspects of the study. All DREAM procedures were approved by the UConn Health Institutional Review Board (IRB; #11-065-6). The CBOs did not have their own IRBs and relied on UConn Health.

DREAM was a randomized trial comparing three interventions for reducing diabetes risk among Cambodian Americans with depression (NCT02502929). The three interventions were all delivered by lay health workers: social services vs group lifestyle sessions vs group lifestyle sessions plus sessions with a pharmacist. This population came to the US as refugees who had survived trauma, torture, and forced starvation during the genocidal Pol Pot regime.

LHR Training

DREAM LHR were trained in research methods, human subjects protection, and study-specific data collection procedures. See Table 2 for details of training. LHR training followed the same principles for low-literacy learners as described above for CALMS-D. LHR training was spread across several weeks with homework and practice between training sessions. Training included a manual designed for this study based on the CALMS-D manual. (The DREAM manual can be requested from the author or found at https://health.uconn.edu/diabetes-research/community-based-research/). Training also included several online tutorials such as an online video that demonstrated proper technique for hair sampling. LHRs learned directly from the investigators in their respective field of expertise. For example, a sleep researcher (OB) trained them in sleep actigraphy. The bilingual study coordinator (SK) was critical to all trainings. LHR observed and role-played data collection. For each measure, LHR were provided a clear rationale for the measure and its relevance to the community’s health. LHRs conducted a minimum of 10 supervised assessments with structured feedback and were judged to be competent by the study coordinator prior to working independently. Supervisor field notes of these assessments were captured for qualitative impressions of the interviews. Investigators (MS, SK, TK) supervised the fieldwork and were available to LHR throughout the study. LHR were awarded paper certificates in recognition of their completion of this training.

A psychologist (JW) trained LHR in administering sensitive surveys. This included topics such as understanding the nature and content of each question, interviewing the correct participant, reading questions as written, voice personality, establishing rapport, being non-judgmental, pacing an interview, probing techniques, knowing when to take a break, responding to participant distress, and participant self-harm safety protocol. Difficult situations and challenging cases were presented. LHR were also taught to work efficiently, record the response correctly, and properly document data. Importantly, because LHR may have personally experienced some of the sensitive situations they were assessing in others, time was spent allowing LHR to discuss their personal reactions to the questions and their comfort level asking them and recording responses.

Supervision

Supervision included on-demand phone calls between the supervisor and an LHR experiencing problems in the field. Regularly scheduled supervision included occasional one-on-one meetings, monthly site-specific group meetings, and meetings of the whole study team. Cross-site group meetings were facilitated by videoconferencing, but at least twice per year CHWs from across the tri-state area met in-person. These meetings, which included refreshments, were an opportunity for the LHR to discuss challenges, successes, provide peer support, socialize, and boost camaraderie. As in CALMS-D, supervision meetings were a time to discuss activities and workload; review documentation and data; provide feedback; identify needs, discuss challenges, and commend progress and accomplishments.

In DREAM, we shifted our focus to the proportion of missing/refused/declined/unusable data from the baseline assessments conducted by LHR. We calculated these outcomes for key behavioral and biological assessments as well as sensitive survey questions that might have a greater likelihood of missing data.

Behavioral data included physical activity actigraphy that entailed wearing a monitor on a strap around the waist, like a belt, as well as a watch-like sleep actigraphy device on the wrist for 7 days [Reference Wagner, Bermudez-Millan and Berthold22]. Validity criteria for sleep and physical activity methods have been detailed elsewhere [Reference Master, Nye and Lee23]. For our purposes, three 24-hour periods of actigraphy data were considered acceptable for analyses; any fewer were considered missing. Participant burden with wearing devices can yield high rates of missing data. Finally, participants provided a hair sample, approximately the diameter of a pencil lead, from the back of the head for assessment of cortisol, a biomarker of chronic stress [Reference Wagner, Bermudez-Millan and Buckley24]. Participant concern about esthetics can result in high refusal rate for the procedure or inadequate hair samples for assay.

Highly sensitive psychosocial surveys included personal history of starvation during the Pol Pot genocide and current symptoms of trauma [Reference Wagner, Bermudez-Millan and Berthold22]. We also asked survey questions about Khmer culture-bound symptoms including baksbat, which uses folk idioms to describe a condition similar to post-traumatic stress disorder and kmoach sanghkat, a sleep disturbance related to trauma that describes sleep paralysis. LHR also assessed food insecurity [Reference Bermudez-Millan, Feinn and Hanh25], the discussion of which can be distressing to participants, particularly those with a history of starvation [Reference Wagner, Bermudez-Millan and Berthold26].

Study #2 Results

DREAM Trial Participants

In the DREAM study, the n = 188 participants were 78% female, average age of 55 years, nearly 50% had a household income below $20,000, most (64%) were not working, and the average educational attainment was 7 years. All spoke Khmer; only 54% were proficient in reading and 43% in writing in Khmer. They were on average 16 years old in 1979 at the end of the 4-year Pol Pot regime and n = 120 reported being emaciated during Pol Pot. At baseline, over half (54%) had elevated depressive symptoms and about one-third were taking antidepressant medication. The sample has been described in detail elsewhere [Reference Wagner, Bermudez-Millan and Buckley24].

DREAM LHR

The seven LHRs were all born in Cambodia and were bilingual/bicultural. They included a man in his 60s with one year of college who was a pastor at an Asian church; a woman in her 30s with a high school diploma who was a certified nursing assistant; a man in his 40s who had previously been a Buddhist monk; a woman in her 50s with a high school diploma who worked as a medical assistant; a woman in her 30s with a certificate in human service assistance, a woman in her 50s with a bachelor’s degree who was an insurance agent; and a woman in her 60s with high school education who was the only certified Community Health Worker. All were active and trusted in their communities and were recruited through informal networks across Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island.

Data Quality

Missing data for sensitive survey questions are as follows: household food insecurity 2.7%; symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder 1.5%, baksbat 1.5%, khmaoch sangkhat 1.5%, and starvation during Pol Pot 11.6%. The percentage of participants with < 3 days of valid sleep actigraphy (i.e., coded as missing) was 3.7%, physical activity actigraphy 8.5%, and the percent with < 3 days both sleep and physical activity was 8.5%. Hair samples for assessment of cortisol were missing or insufficient for 7.5%.

Qualitative impressions from supervisors showed that DREAM LHR demonstrated a high degree of cultural consonance including respect for elders, using kinship terms, and use of cultural idioms. They also followed culturally dictated interpersonal etiquette such as rules for bowing, greetings, touch, removing shoes before entering the home, using both hands to pass an object to an elder, and avoiding head and feet. They conveyed respect for traditional medicine and healers and responded skillfully to participant fear of disclosure, mistrust of authority, and distress regarding trauma history.

Discussion

In these 2 trials, the work of LHR was highly successful. CALMS-D documented that fidelity to assessment protocols was high and that LHR found the work to be rewarding and empowering. DREAM showed acceptable levels of missing data for biological, behavioral, and highly sensitive psychosocial data (1.5%–11%). This compares favorably with a median of 9% missing outcome data in a recent review of RCTs in top medical journals [Reference Bell, Fiero, Horton and Hsu27]. Although we do not have data in this regard, it was our observation that missing data were more likely on the few occasions when LHR did not have access to REDCap and collected data using paper and pencil. Clear training, written protocols were deemed as helpful. LHR reported that clear training and written protocols were helpful for their task and that clear communication and trust with participants lead to high participant motivation and satisfaction. To achieve these successful outcomes, the research team provided extensive training and supportive supervision and strived to create a culture of collaboration. Due to the relatively small literature on LHR specifically, in our discussion we rely on the broader literature on LHW, i.e., including those in non-research roles.

Training and Skill Acquisition

Overall, LHR enjoyed learning research skills, consistent with other reports [Reference Klein, Tucker and Ateyah28]. Opportunities for training are considered crucial for LHW career development [Reference Smithwick, Nance, Covington-Kolb, Rodriguez and Young29]. There are few studies of LHR, but qualitative data from LHW in clinical work show that, in addition to higher wages, a primary factor considered for LHW career advancement should be participation in additional training opportunities [Reference Smithwick, Nance, Covington-Kolb, Rodriguez and Young29].

Methods for training in CALMS-D and DREAM were varied but in both instances they were rigorous and systematic. In addition to the specific data collection protocols, time was spent on education regarding the research enterprise more generally and how it differs from more traditional LHW tasks such as patient navigation and medical translation. As has been discussed by others [Reference Terpstra, Coleman, Simon and Nebeker30], both trials offered LHR training in the principles of research ethics, i.e., respect for persons, beneficence, and justice as well as protection of human subjects and informed consent taking into account the required time for personnel naïve to research. In-person practice with live feedback from supervisors was critical. Understanding the rationale behind each measure, not simply the technique to collect it, was important to LHR.

LHWs are best motivated by work that provides opportunities for personal growth and professional development, irrespective of the direct remuneration and technical skills obtained [Reference Colvin, Hodgins and Perry31]. One systematic review found that LHWs were empowered by access to privileged medical knowledge, by linking LHWs to the formal health system, and by providing them an opportunity to do meaningful and impactful work [Reference Kane, Kok and Ormel32]. However, these empowering influences were frustrated by lack of control over one’s work environment and feelings of being unsupported, unappreciated, and undervalued. We believe that our success was from pairing the empowering factors – knowledge, linkage to a formal system, and meaningful work – with appropriate remuneration and supportive training and supervision, all of which demonstrated appreciation and valuing of LHR.

Notwithstanding their broad set of skills, there were some data collection procedures that LHR did not conduct. We experienced that LHR were comfortable shipping material samples, including hair samples and actigraphy supplies. However, whereas they were comfortable collecting electronic data (i.e., from Holter monitor, CGM), they were not comfortable transferring the electronic data to the university over the Internet. Based on their understandable discomfort with the technological complexity of data transfer and potential for loss of confidentiality, we had supervisors transfer electronic data.

Collaboration

Working relationships between LHWs, health professionals, and community members strongly shape LHW motivation [Reference Colvin, Hodgins and Perry31]. We aimed for a collaborative relationship shown to be key in previous studies. In Uganda, 8 LHWs in two tuberculosis clinics formed a community of practice [Reference Hennein, Ggita and Turimumahoro33]. In qualitative interviews, LHWs identified activities as core to improving the quality of their work: (1) individual review of performance, (2) collaborative improvement meetings, (3) real-time communications among members, (4) didactic education sessions, and (5) clinic-wide staff meetings. LHWs reported that these activities allowed them to share challenges, exchange knowledge, engage in group problem-solving, and benefit from social support. They felt a shared sense of ownership of the work, which motivated them to propose and carry out innovations. The model community strengthened their social and professional identities within and outside the group and improved their self-efficacy. Whereas neither CALMS-D nor DREAM created a formal community of practice, our meetings were mostly successful in including the key elements including collaborative improvement, feedback, real-time communication, education, and study-wide meetings.

A concrete example of collaboration was the number of ways LHR brought real-life experience to develop acceptable methods. They pilot-tested all the measures, both biological and surveys, and provided feedback about challenges and potential solutions. For example, LHR helped us calibrate incentives that were motivating but not coercive for community members. They suggested bringing coloring books and crayons to home visits to keep children in the household occupied. They suggested that we provide headsets for answering the IVR telephone calls, and recommended coolers for urine storage because participants were not comfortable storing it in the refrigerator. They informed the handouts that we gave to participants for each measure. Another example of collaboration is the co-creation of tracking documents that were designed by LHR with ease of use in mind and by researchers with data elements in mind. Our bilingual, bicultural study coordinators were extremely helpful in facilitating these types of LHR input.

Although LHRs were involved in data collection, recruitment, and intervention delivery in CALMS-D and in DREAM studies, they did not collaborate on research design per se. Nevertheless, it should be noted that both studies were community-based, participatory research studies and the academic and CBO personnel worked together as “equal partners” to identify the problem, develop a research question, and design and conduct the study.

To recruit and retain LHR, human resource policies of the hiring institution must be considered [Reference Hill, Bone and Butz34]. It was our experience that LHR being employed by the CBO, rather than the university, was ideal. Participants associated LHR with the CBO, an organization known trusted and located in the community, rather than with the university. Their direct supervisors at the CBO managed their scheduling, which can be complicated when some LHR are paid part-time on the study and part-time in service delivery programs. Recruiting, interviewing, hiring and firing LHR, and internal communications are facilitated by the CBO. Also, a CBO may be more likely than a university to have a position available once the grant funding ends, so a CBO can offer LHW more job security.

Supervision

Availability of prompt and helpful support for fieldwork was reported as helpful and necessary, consistent with prior literature. In one study, a group supervision intervention was implemented in 4 African low- to middle-income countries (LMICs [Reference Kok, Vallières and Tulloch35]) and then 153 in-depth interviews with LHWs, their supervisors, and managers. In addition, questionnaires assessing perceived supervision and motivation were administered to a total of 278 LHWs pre- and post-intervention, and again after 1 year. Although questionnaires showed no quantitative changes, qualitative findings showed perceived value in the process of supervision, the problem-solving focus, the sense of joint responsibilities and teamwork, cross-learning and skill sharing, as well as the facilitating and coaching role of the supervisor. The empowerment and participation of supervisees in decision-making also emerged as important.

A study in Uganda [Reference Ludwick, Turyakira, Kyomuhangi, Manalili, Robinson and Brenner36] conducted focus groups with four high/medium-performing CHW teams and four low-performing LHW teams. Variances in scores between "high"-/"medium"- and "low"-performing LHW teams were largest for "supportive supervision" and "good relationships with other healthcare workers." LHW team performance was related to the quality of supervision and relationships with other healthcare workers. Key supervisor issues included absentee supervisors and lack of engagement/respect.

In Zimbabwe, n = 342 government-employed LHWs were tasked with identifying and referring pregnant women for early antenatal care [Reference Kambarami, Mbuya, Pelletier, Fundira, Tavengwa and Stoltzfus37]. Factors associated with performance of one task were not the same as those associated with performance of another task, but both tasks depended on type and quality of supervision.

We submit that providing ongoing, supportive supervision to LHWs is critical. We found that tools such as checklists were helpful for LHR task completion and that simple spreadsheets were key for tracking progress with, for example, study assessment visits. We encouraged LHR to co-create these tools so that they would be of maximal benefit to the team. According to the Rural Health Information Hub [15], a supportive LHW supervisor is regularly available, provides supportive and trauma-informed supervision, prioritizes safety, and offers monitoring and coaching to LHWs. It is also essential that the supervisor dedicates sufficient time for LHWs, especially those working in new roles.

Limitations and Conclusions

Several limitations should be considered. First, the sample of LHRs was small and limited to only two racial/ethnic communities in the New England region of the U.S. Second, in this article we used different methods to examine LHR performance across these two studies, mainly fidelity in CALMS-D and missing data rates in DREAM, so we cannot compare them directly. However, evidence previously published shows that CALMS-D LHR collected high-quality data with few missing values [Reference Wagner, Bermudez-Millan and Damio21] and DREAM LHR were also able to successfully perform clinical measurements [Reference Wagner, Bermudez-Millan and Buckley24]. Although the researcher conducting the LHR qualitative interviews was an independent third party, the study coordinators giving subjective impressions were not, and researcher bias and demand characteristics cannot be ruled out.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this work confirms our previous work on LHR and data collection in type 2 diabetes self-management interventions including DIALBEST [Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Damio and Chhabra38]. Similar lessons regarding training, supervision, acceptability, motivation, and support from the broader team have been described regarding CHW providing service delivery [Reference Pallas, Minhas, Pérez-Escamilla, Taylor, Curry and Bradley39]. The role of the bilingual, bicultural study coordinators in working with LHR on each aspect of the study was crucial. It should be underscored that CALMS-D and DREAM were not just facilitated by LHR, but were in fact completely dependent upon them [Reference Lu, D'Angelo, Kuoch and Scully40]. LHR helped the academic researchers develop data collection protocols that would have the greatest likelihood of acceptability to participants and LHR also helped investigators anticipate and avoid potential mistakes, inefficiencies, and cultural misunderstandings. LHR feedback about problems with data collection procedures and potential solutions were vital. Further, this relationship of mutual respect may mitigate LHRs acting as gatekeepers to research, i.e., acting to “protect” patient populations from experiencing trauma by engagement in research [Reference Killough, Madaras and Phillips41].

LHR possess a unique skill set that makes them indispensable members of the research team, rather than mere “helpers” that facilitate task shifting downwards [Reference Berthold, Kong and Kuoch42]. Home-based data collection of this nature would be difficult or impossible by a typical academic researcher embedded in an academic research setting.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2023.647.

Funding statement

This work was supported by American Diabetes Association (7-13-TS-31), National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (DK103663), and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (MD005879), The Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (DK092949) and the Dean’s Office of the Biological Sciences Division of the University of Chicago. OMB is in part supported by the Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NCATS UL1 TR002014). The participation of RP-E in this study was made possible through the support of the Yale Griffin Prevention Research Center Cooperative Agreement Number 5 U48DP006380-02-00 funded by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (PI: RP-E).

Competing interests

Outside of the current work, Dr Orfeu M. Buxton discloses that he received subcontract grants to Penn State from Proactive Life (formerly Mobile Sleep Technologies), doing business as SleepSpace (National Science Foundation grant #1622766 and NIH/National Institute on Aging Small Business Innovation Research Program R43AG056250, R44 AG056250), received honoraria/travel support for lectures from Boston University, Boston College, Tufts School of Dental Medicine, New York University, University of Miami, University of South Florida, University of Utah, University of Arizona, Harvard Chan School of Public Health, Eric H. Angle Society of Orthodontists, and Allstate, consulting fees for SleepNumber, and received an honorarium from the National Sleep Foundation for his role as the Editor in Chief of the journal Sleep Health. All other authors have no competing interests to declare.