Introduction

The agricultural sector holds a significant role in developing countries and Nigeria is no exception. According to data from the World Bank, agriculture is the largest employer of labor in Nigeria. Employment in agriculture (percent of total employment) in Nigeria was reported at 36.38 percent in 2019. The sector is also the largest income-generating activity, with contributions to the gross domestic product (GDP) of about 24–30 percent. Unfortunately, the agricultural sector is particularly vulnerable to violent conflict.Footnote 1 In particular, through killings, injuries, maiming of individuals, threats, fear, migration, and displacement, violent conflict affects directly the labor supply and demand of agricultural households.

Over the last few years, studies examining the impact of violent conflict on agricultural outcomes using micro-level data have increased. Many of these articles provide evidence of the adverse effect of conflict on agricultural production through different pathways, including reduced access to credit and decline in labor supply (see Verpoorten Reference Verpoorten2009; Blattman and Miguel Reference Blattman and Miguel2010; Verwimp, Justino, and Brück Reference Verwimp, Justino and Brück2018; Brück, d'Errico, and Pietrelli Reference Brück, d'Errico and Pietrelli2019). With respect to Nigeria, research on the impact of conflict on agriculture-related outcomes has increased. However, there is still room for more knowledge on the impact of conflict in Nigeria on certain agricultural outcomes.Footnote 2 In particular, while Adelaja and George (Reference Adelaja and George2019a) examined the effects of Boko Haram insurgency on output and input demand including the demand for hired labor and supply of family labor, the impact of conflict on the labor supply of a household head, spouse, and children was not examined separately. Given the possibility of a heterogeneous impact of conflict on labor supply, a more robust investigation is useful and is one of the motivations for our research.

The main motivation for our research is the current gap in the conflict literature on Nigeria. In particular, the recent past literature on the conflict in Nigeria focused primarily on the impact of the Boko Haram insurgency on different health, economic, and labor market outcomes. This focus on Boko Haram political violence could be limiting in perspective, given Nigeria's past history of violent conflict in different locations, at different times, driven by different actors and perpetrators. The reality is that armed conflict has plagued Nigeria long before the onset of the Boko Haram crises. Currently, in Nigeria, violence erupting from the farmer–herdsmen conflict, bandit attacks, and Fulani militia has increased precipitously and has led to a significant number of fatalities. Therefore, a research focus on Boko Haram cannot provide perspective for the current growing crises as the states, local government, towns, and villages that have had direct exposure to this growing violent conflict are different from the communities that have been significantly affected by Boko Haram attacks and abductions. The changes in violence hotspots in Nigeria over time are evidence of the proliferation and widespread nature of conflict in Nigeria. Moreover, the changes that have occurred in the profile of perpetrators and in location are a reminder of the heterogeneity in conflict exposure across communities. Given that violent conflict in Nigeria goes beyond Boko Haram or the farmer–herdsman current conflict, and with recent results on Nigeria by Odozi and Oyelere (Reference Odozi and Oyelere2019) suggesting negative welfare effects of violent conflict in general, then, examining the effect of violent conflict generally on labor supply, one of the potential channels that could explain their finding, is a fruitful exercise that promises to valuable insights. This is the goal of our article.

In this article, we focus on two related questions as we attempt to bridge the gap in the existing literature on the effect of conflict on farm labor supply. First, does recent exposure to violent conflict affect total family labor hours and is there heterogeneity in effect on the number of hours worked by the household head, spouse, children, and relatives? Second, does long-term accumulated exposure to conflict (direct or indirect) affect total family labor hours supplied and is there heterogeneity in effect on the number of hours worked by the household head, spouse, children, and relatives? For both questions, we focus on small holder farm households.Footnote 3 We attempt to answer these questions using household survey panel data for Nigeria in combination with data from The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) by Raleigh et al. (Reference Raleigh, Linke, Hegre and Karlsen2010).

To examine both the short-term and long-term effects of conflict exposure on labor supply, we construct two measures of conflict exposure based on conflict-related fatalities. We refer to our first measure as recent exposure to conflict and the second measure as long-term accumulated exposure to conflict.Footnote 4 To estimate the effect of conflict on farm labor supply, we initially use a Heckman selection model that can attenuate self-selection bias. However, given the limitations of the Heckman model, we consider it simply as our baseline model.Footnote 5 To derive consistent estimates, we subsequently use a fixed effects approach exploiting the panel nature of our data. The fixed effects approach is our preferred method for our analysis because this approach uses within household variation over time, thereby attenuating potential biases in estimated effects. In particular, it eliminates biases linked with unobserved time-invariant differences across households that affect labor supply and are also correlated to conflict exposure.Footnote 6

Our results provide evidence of the significant negative effect of both recent exposure to conflict and accumulated exposure to conflict on total family farm labor supply. When we consider the different sources of farm labor, we find that the significant effect of conflict is driven by a decline in the labor supply of household heads. We do not find any significant effect on the farm labor of children or spouse. Our results using the Heckman selection model corroborate our fixed effect results.

Our article contributes to the literature by providing the first analysis in Nigeria on the overall average effect of exposure to violent conflict between 1999 and 2015 on the farm labor supply of agricultural households. While we are not the first to examine the effect of specific conflicts in Nigeria on agricultural outcomes such as productivity or the number of hours worked, our article provides a broad perspective that is value adding and fills a gap in the literature. Adelaja and George (Reference Adelaja and George2019a) focusing solely on the effects of Boko Haram did not find any impact of that particular conflict on total family labor supply. In contrast, our results suggest that violent conflict in Nigeria on average negatively affects total family labor supply, and within households, the farm labor supply of household heads is significantly reduced.

Another contribution of our article is that our results suggest significant lingering negative effects of armed conflict on labor supply, which has relevant policy implications. As mentioned above, the agricultural sector in Nigeria is a major employer of labor and contributes significantly to the GDP. Farm households are both users and suppliers of labor for upstream primary agricultural production activities, whether planting, rearing, weeding, nurturing, and harvesting. The link of farm household activities with downstream agricultural activities raises the policy importance of farm labor supply as a channel of poverty reduction and national food security. Hence, shocks that negatively affect labor supply have downstream effects that ultimately could affect welfare negatively, leading to increases in poverty incidence and severity. Odozi and Oyelere (Reference Odozi and Oyelere2019) provide evidence that exposure to violent conflict significantly reduces income and increases incidence, depth, and severity of poverty in Nigeria. However, the pathways through which conflict decreases income or increases poverty have not been investigated. The results in our article also contribute to the literature by providing evidence of one possible pathway through which conflict could have increased poverty. In particular, violent conflict reduces the hours of labor supplied by farm households. This reduction in labor supply decreases production and earnings and increases the vulnerability of farm households to falling under the poverty line or sinking deeper into poverty.

The rest of our article proceeds as follows. In the next section, we provide a background of conflict in Nigeria. In the section estimation results, we review the past literature. Conceptual framework: labor supply and conflict is a synopsis of our conceptual framework. Empirical strategy focuses on our empirical strategy for answering our questions of interest. In data and descriptive analysis, we present our data and descriptive analysis. In results, we present our results. We conclude in the last section.

Background: conflict in Nigeria

Violent conflict is a significant part of Nigeria's history and is still an ongoing reality for many Nigerians today. While the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic has claimed many lives and is dominating government and different stakeholder conversations, violent conflict that has been escalating in Nigeria has not gotten as much attention.Footnote 7 The challenge that lies with this inadequate attention is the neglect of the significant impact that violent conflict is having on groups, particularly farming communities. It is worth noting that between 2020 and 2021, violent conflict has led to higher fatalities than even COVID-19-related deaths.Footnote 8

Nigeria's episodes of violent conflict are not just a recent occurrence of the twenty-first century. Violent conflict in Nigeria is somewhat eclectic and may be defined as low intensity. What appears to be changing with respect to conflict in Nigeria is the players or perpetrators and the intensity of fatalities and frequency of events that have escalated over the last 15 years. Odozi and Oyelere (Reference Odozi and Oyelere2019) provide a detailed summary of the history and nature of conflict in Nigeria. They note that in the 1960s the violent conflict events in Nigeria were linked with political challenges instigated by state creations (Tiv Riots), political unrest, military coups, and attempts of a region of Nigeria to secede. The Biafran Civil War of 1967–1970 was the end product of some of the crises that characterized this decade. While political conflict as a source of violence in Nigeria continues to persist, other dimensions of conflict have emerged that have led to significant fatalities and new hotspots. In the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s violent conflict in Nigeria was also common place. The conflicts were heterogeneous with respect to location and perpetrator. Some known examples are the Bakolori Massacre, Odi massacre, and the 1980 Kano riot. One reoccurring type of conflict is religious conflict, usually between Christians and Muslims. Religious and ethnoreligious conflict events became quite a common place in Nigeria in the 1980s and 1990s especially in the northern part of the country.

Another major source of conflict since the early 90s is the Niger Delta conflict. The conflict in this region has been driven by the struggle among local communities, multinational oil companies, and the Nigerian state for control over the resource-rich territory and oil revenues. The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) emerged and had became violent since 2006 (Courson Reference Courson2009). Their violent activities were characterized by oil worker abductions, attacks of government forces, and oil installation sabotages.

Since 2000, violent conflict in Nigeria has increased precipitously. According to estimates from Nigeria's National Commission for Refugees between 2003 and 2008, there were an estimated 3.2 million Internal Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Nigeria resulting from conflict. Within communal conflict, there has also been a significant increase in both ethnoreligious and farmer–herder conflict, but farmer–herder conflict increases are more common. Recent data suggest that between 2010 and 2019, nearly 19,000 people had died as a result of conflict of this type.Footnote 9 The last five to six years have been characterized by a significant increase in massacres by herdsmen, and while most of these attacks were localized within Benue and Plateau state, there has been a proliferation of killings linked with herdsmen in multiple locations across Nigeria.Footnote 10 In fact, the farmer–herder conflict has evolved into armed banditry involving cattle rustling, destruction or theft of farm crops, kidnaping, and armed robbery. As noted in Olaniyi (Reference Olaniyi2015), unlike the sedentary Fulani, the Bororo Fulani herders are considered very aggressive and always fully armed with AK-47 s, charms, and cutlasses and attack farmers and communities with lethal weapons.

Another major kind of perpetrator of conflict in Nigeria emerged in 2009 and has gotten the most attention internationally. Since 2009, the rise of Boko Haram has added to the already significant sources of conflict in Nigeria. This terrorist group has been oppressing communities in Northern Nigeria and causing havoc on education and health facilities, attacks on markets and farms, closure of cattle markets, and restricted access to lands. Using data from 2000 to 2020, ICON reports that Boko Haram has killed more than 43,000 Nigerians, and the vast majority of these deaths were women and children.

While there is a lot of attention on Boko Haram and growing attention on farmer–herder conflict, it is important to mention that that Boko Haram conflict has expanded beyond terrorism to banditry particularly in the North West. Different groups are also emerging and asking for the right to self-determination. The year 2020 led to a rise of militia groups that target communities in certain states, especially, southern Kaduna state. This new campaign of violence targeting communities has been linked with Fulani militia and may be viewed as an ethnoreligious conflict given the religious and ethnic links.

The heterogeneous conflict in Nigeria and the proliferation of hot spots over time and across regions are our motivation for looking at the impact of conflict in Nigeria holistically. We do not focus on one conflict type but all violent conflict types. However, it is important to note that while most parts of Nigeria have had some exposure to violent conflict since 1960, the intensity of violent conflict exposure varies across regions. The three zones with the highest prevalence rates of conflict over the last few decades are the North East, North Central, and South South regions of Nigeria. It is also worth highlighting that these regions have a significant share of their population working in agriculture.

Literature review

Economic literature focusing on the microeconomic consequences of conflict across African countries has increased in the last two decades.Footnote 11 More recently, there has also been an increase in articles focused on trying to explain the rise in certain types of conflicts within Africa.Footnote 12

Given the pivotal role of agriculture in many developing economies, the effects of idiosyncratic shocks on labor market outcomes have also been examined. For example, there is an established literature on shock events such as bad weather, price, and unemployment shocks, and their effects on off-farm labor supply (Kochar Reference Kochar1999; Rose Reference Rose2001; Cameron and Worswick Reference Cameron and Worswick2003; Lamb Reference Lamb2003; Mueller and Quisumbing Reference Mueller and Quisumbing2010; Cunguara, Langyintuo, and Darhofer Reference Cunguara, Langyintuo and Darhofer2011; Mathengea and Tschirley Reference Mathengea and Tschirley2015). This strand of literature suggests that farmers increase the supply of off-farm labor under unfavorable conditions in order to maintain consumption levels, which reduces farm work time.Footnote 13 More recently, there is an increasing focus on how conflict as a specific shock affects agricultural-related outcomes (Adelaja and George Reference Adelaja and George2019a; George, Adelaja and Weatherspoon Reference George, Adelaja and Weatherspoon2020).

With respect to Nigeria, there is a growing literature on the effects of conflict on different economic- and welfare-related outcomes. For example, Nwokolo (Reference Nwokolo2015) used the Nigerian demographic data and ACLED data to examine the effect of Boko Haram Insurgency (BHI) on child health. Child health was also considered by Ekhator-Mobayode and Asfaw (Reference Ekhator-Mobayode and Asfaw2019). Their study examined the effect of BHI on measures of children's health. Bertoni et al. (Reference Bertoni, Di Maio, Molini and Nistico2018) examined the impact of civil conflict (specifically Boko Haram) on school attendance and attainment. They found an increase in the number of fatalities to which a child is exposed and a decrease in the number of completed years of education for the cohort exposed to conflict during primary school compared with the non-exposed cohort.

There is also a growing literature on the impact of conflict on food- and agriculture-related outcomes in Nigeria. The effect of conflict on food insecurity was explored by George, Adelaja, and Weatherspoon (Reference George, Adelaja and Weatherspoon2020). They examined the effect of armed conflicts on food insecurity using the General Household Survey (GHS) panel data for Nigeria and Boko Haram terrorist incidence data. They found that an increase in conflict intensity, measured by the number of fatalities, increase in the number of days where the household consumed foods that were less preferred. In addition, they found negative effects on the variety of foods a household consumed and the portion size of the meals. In a related article that focused on food insecurity, using the GHS panel data complemented with a 2017 phone survey, Kaila and Azad (Reference Kaila and Azad2019) explored the effect of conflict victimization on consumption and food security noting heterogeneity in the effects of conflict. In particular, they found that conflicts involving Boko Haram had more severe negative effects on consumption and food security than conflicts involving the Fulani herdsmen or militant groups in the Niger Delta.

With respect to agricultural-related outcomes, Sidney, Zummo, and Kwajafa (Reference Sidney, Zummo and Kwajafa2017) examined the effect of Boko Haram on peasant farmers’ productivity in selected localities in Adamawa state (an area that has been directly affected by Boko Haram activities) finding significant negative effects. Adelaja and George (Reference Adelaja and George2019b) estimated the causal effects of exposure to attacks on plot ownership, cultivated land, rented land, land values, and cropping patterns. They provided results suggesting that an increase in the intensity of terrorist attacks results in increases in the percentage of land left fallow and increases in the average distance between plots farmed and the homestead, and increases in attacks discourage mono cropping and encourages mixed cropping. They also find that farmers expectations about the values of their lands decreased with increased exposure to violent conflict.

In yet another article, Adelaja and George (Reference Adelaja and George2019a) examined the effects of the Boko Haram insurgency on farm output and the demand for farm inputs including the demand for hired labor for harvest operations. Using the same data, their results suggest that violent conflict reduces the hours of hired labor but does not affect the use of family labor, also suggesting that conflict mainly affects hired labor and not family labor.Footnote 14 Mitchell (Reference Mitchell2019) also used the same data set as Adelaja to estimate the effect of conflict events on household input use, cattle holdings, and cropping decisions. The article differs from the Adelaja and George's article in some of the outcomes considered and the methodology employed to estimate the effect of conflict. Mitchell (Reference Mitchell2019) also differentiated between the Boko Haram conflict and the Fulani herdsmen conflict. Using an events study framework, he found evidence of negative effects of the Fulani herdsmen conflict on a household's cattle holding in the following season. The author did not find significant effects of the Boko Haram conflict on most of the outcomes considered using the events studies method.

Our article makes use of the same GHS panel data set used by Adelaja and George (Reference Adelaja and George2019a and Reference Adelaja and George2019b) and other aforementioned articles. Like these papers, we look at the effect of conflict at an area level (LGA or EA). However, our research differs from most of the articles discussed because these studies either focus on the effect of the Boko Haram insurgency or compare the effects of that insurgency with those of the Fulani herdsmen conflict. In contrast, we take a more generalized approach. We believe that this approach is justified given the prolonged exposure to violent conflict in different parts of Nigeria and the potential value of exploring the average treatment of conflict in Nigeria on the labor supply of agricultural households. Moreover, we focus on the overall effect of violent conflict in Nigeria, both recent and accumulated. To the best of our knowledge, our article is the first that has attempted to explore both the long-term and short-term effects of conflict in Nigeria on labor supply. Furthermore, another unique aspect of our article is that we complement the covariate conflict exposure measure with household-level idiosyncratic shocks. Controlling for households’ idiosyncratic shocks attenuates bias in estimated effects and differentiates our article from the aforementioned articles that assigned conflict at the community level or LGA and did not control for other idiosyncratic shocks.Footnote 15

Conceptual framework: labor supply and conflict

Labor—described as human effort—is about the most easily available resource used by households in rural settings whether for on-farm activities, participation in off-farm labor activities, or the allocation of labor across various livelihood activities. Interactions between individuals and groups can lead to conflict and such conflict can be violent with “dramatic consequences on human well-being” (Hsiang, Burke, and Miguel Reference Hsiang, Burke and Miguel2013). Through direct and indirect channels, violent conflict can impact the labor supply outcomes of households and individuals exposed to violence. First, violent conflict leads to fatalities and injuries. This exogenous shock directly affects a household's labor stock and households can experience labor shortage because certain household members are no longer participating in the labor force due to fatality or injury from conflict. The labor shortage could also be reflected in the total decrease in hours worked by the household. In particular, injury can reduce the time available to work as individuals may be temporarily disabled or need to take time to recover, which directly translates to loss of labor hours on the farm.

Another channel that can lead to labor supply shortages for farm households is the destruction of farms. The destruction of farm lands (e.g., through burning or theft of crops, looting of cattle, etc.) and other productive assets can discourage households from supplying more hours of labor to agriculture activity, given the unpredictability in return linked with unexpected violent attacks and looting. Furthermore, violent conflict can precipitate fear in individuals exposed to it. In this scenario, farmers are afraid to leave their homes and to cultivate more isolated farm plots. Violent conflict also leads to displacement. Displacement can be long term or short term. In either cases, farmer households’ labor supply is disrupted as families are forced to migrate and total hours dedicated to farm activity declines.Footnote 16

The aforementioned pathways are likely to induce drops in agricultural production or output. We hypothesize that this decline in agricultural output will consequently force households to seek employment outside of agriculture in order to smooth consumption or income. Similar to the discouraged worker effect of unemployment shocks, small holder farmers could decrease their labor force participation in response to agricultural losses or decrease the hours dedicated to farm work. However, the overall effect on a household's labor supply is an empirical question. The overall effect on labor participation of agricultural households will depend on farmers’ prevailing conditions. If farmers are less able to migrate and more credit constrained and workers supply labor less elastically, then the overall labor supply response might turn out to be negative. However, if there is ample opportunity for off-farm employment or labor markets are not closed or are not too dangerous to travel to, then this will give rise to a positive labor supply response. Fernández, Ibáñez, and Peña (Reference Fernández, Ibáñez and Peña2014) noted that if labor markets were available, then the occurrence of a violent shock would render on-farm work less profitable and market work more attractive. However, we are of the opinion that since violent conflict often affects several markets, including the off-farm labor market, we hypothesize an overall negative labor supply response of violent conflict exposure.Footnote 17

Intrahousehold substitution effect can also arise from a violent conflict shock. The “added worker effect” hypothesis in the labor economics literature predicts that the labor force participation rate among women is expected to increase as women have to enter the labor force to substitute for the labor of men who were killed, injured, and migrated or displaced as a result of exposure to violent conflict. As noted in Justino and Shemyakina (Reference Justino and Shemyakina2012), the death of working age household head may lead to changes in the household reallocation of labor, for example, women and children replacing lost workers. In this article, we will check for evidence of intrahousehold labor reallocation. We focus on testing for changes in the hours of labor supplied of a household head, spouse, children, and relatives separately.

Empirical strategy

To answer both questions of interest, we estimate the impact of armed conflict on hours of labor supplied on the farm. We make use of two estimation strategies. First, we explore a Heckman selection model given the potential of self-selection bias. We consider this as the baseline model. Our second and preferred estimation strategy is a fixed effects (FE) approach exploiting the panel nature of our data. The Heckman selection model includes two separate equations. The first is the sample selection equation, focused on selection into labor force participation. For this equation, our dependent variable is a dummy variable and it takes the value of 1 if a household head participates in the labor force and 0 otherwise. The second equation is the main equation linking the covariate of interest—violent conflict to the outcome variable—hours of farm labor supply. We estimate the Heckman model multiple times changing our measure of hours of farm labor. First, we consider the total family farm labor supply and then we consider separately farm labor supply by household head, spouse, children, and finally relatives.Footnote 18

For our first question, our main independent variable and our measure of the intensity of exposure to conflict are based on recent violent deaths in a household's LGA. We refer to this as recent conflict exposure.Footnote 19 For our second question, we focus on accumulated exposure to conflict from 1997 to the year of the survey.Footnote 20 We refer to this conflict measure as long-term/accumulated conflict exposure.

In both equations, we include a series of control variables. In particular, based on past literature that established a relationship between weather/climate variables and rural labor markets (Jessoe, Manning, and Taylor Reference Jessoe, Manning and Taylor2018), we control for plot characteristics, the nutrient availability of the soil, annual mean temperature, and annual rainfall. We also control for community characteristics that vary at the local government area level used to control for the demand-side factors regarding the availability of off-farm work. These variables include distances to major roads, population centers, market, and border and administrative centers. In addition, we control for household characteristics to account for household preferences, in particular, we include age and age squared, the level of education of the household head, gender, and household size. Given the importance of health and labor supply, we control for health using two variables. The first captures if an individual has had any illness or injury during the past 4 weeks preceding the survey. The second variable tries to get at the severity of past illness that could have a more significant effect on labor supply. The variable captures if an individual has been hospitalized in the last 12 months. We also control for exposure to idiosyncratic shocks. Following Kochar (Reference Kochar1999) and Rose (Reference Rose2001), we also control for market wage. Other variables included to control for household wealth are the value of land (self-reported by farmers) and the use of land size and agricultural wage as controls for aggregate consumption. We also include state fixed effects and interaction between zone and time fixed effects.

For a more robust identification, the selection equation should have at least one variable that is not in the outcome equation. This imposes the exclusion restriction. In an ideal case, the variable has a non trivial impact on the probability of labor force participation. For our analysis, we use the total number of conflict events in a LGA from 1997 until the year of the survey. Our argument is that these accumulated events provide institutional history and a rough measure of the stability of the LGA which could affect if an individual participates in the labor force. However, we do not expect that history would directly affect the hours an individual will choose to work currently (hence its non inclusion in the outcome equation).

While the Heckman selection model can attenuate issues of self-selection bias, its limitations in addressing potential endogeneity issues and the difficulty in making the case that our exclusion restriction is valid lead us to our preferred estimation strategy, the fixed effects (FE) approach.Footnote 21 The FE model can be specified as follows:

H ijt is the total family hours of labor worked in household i in LGA j and year t. ConflictEXPjt is a measure of violent conflict in LGA j and year t. xij is a vector of individual and household variable regressors that affect the number of hours worked and cij represents time-varying local government area characteristics such as the rainfall levels, population density, nutrient availability in plots, and temperature. δ are time-invariant household-specific effects that could be correlated with the observed covariates and also include state fixed effects; γ t are year fixed effects; ψ zt are interactions of zone and year dummies to control for time-varying zone effects; ε ijt is the idiosyncratic error term. β1 is the parameter of interest to be estimated and captures the effect that exposure to conflict has on labor supply.Footnote 22

Using panel data and a fixed effect strategy attenuates biases in coefficients and increases the likelihood that estimated effects are consistent. The fixed effect approach accounts for time-invariant characteristics of households that could be correlated with conflict and also correlated with our variable of interest—hours worked on farm. Hence, biases emanating from household heterogeneity are attenuated with this method. While the fixed effect strategy cannot remove biases stemming from unobserved time-varying household characteristics, we can attenuate this kind of bias by including as many time-varying controls as possible in our analysis.Footnote 23

It is useful to mention that reverse causality and simultaneity can hinder deriving consistent estimates even when a fixed effects strategy is used for estimating the effect of conflict. In the case of the question we are interested in, we do not worry as much about reverse causality, even though we cannot rule it out. In particular, in both the questions, we consider, we are looking at the effect of past conflict on current farm labor supply. It is harder to argue that an individual's current farm labor supply is causing a change or driving their past accumulated conflict exposure.

Data and descriptive analysis

The socioeconomic data used in this study are the Nigeria General Household Survey (GHS). As noted on the World Bank's Central Microdata Catalog website, “The GHS is implemented in collaboration with the World Bank Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) team as part of the Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (ISA) program and was revised in 2010 to include a panel component (GHS-Panel)”.Footnote 24 The survey was undertaken by the National Bureau of Statistics in partnership with the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD), the National Food Reserve Agency (NFRA), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), and the World Bank (WB).

All sampled households were administered a multitopic household questionnaire. The questionnaire geo-references the dwelling's location and collects individual-disaggregated information on demographics, education, health, employment, anthropometrics, various income sources, housing, food and nonfood consumption and expenditures, and asset ownership. There is also an agricultural questionnaire module with observations on geo-referenced plot locations and Global Positioning System (GPS)-based plot areas, plot-level information on input use, cultivation, and production (the household members who manage and/or own each plot and individual-disaggregated labor input at the plot level. The survey information is provided for postplanting/preharvest and the postharvest outcomes. The GHS Panel is a nationally representative survey of approximately 5,000 households, which is also representative of the geopolitical zones in Nigeria at both the urban and rural levels. There are four waves currently of the panel (2010, 2012, 2015, and 2018) and we used the labor file questions in the agricultural and household modules. The labor file in the agricultural module that we used for the analysis of labor supply in terms of hours worked provides information on the total hours of work supplied to farm work during the harvest season. The file is disaggregated across hours of labor work for the household head, the spouse, the children, and the relatives. To arrive at total hours of work supplied by farm families, we added hours of work supplied by each household member including the relatives. While the labor file in the agricultural module focused on the hours of labor supplied by farm families at the plot level and disaggregated across household members, the labor file in the household module focused on the different employment status of households without a clear demarcation of the hours worked across wage employment, farm employment, and off-farm employment particularly for Waves 1 and 2. We used the labor file in the agricultural module in analyzing the hours of labor supplied by agricultural households while we used the labor file in the household module in analyzing the labor participation of agricultural households.

Despite the availability of the four waves, we made use of the first three waves in our analysis because of an observed significant inconsistency in the labor file for wave 4 compared with the earlier waves of the survey. For example, in wave 4, the labor time is not disaggregated by household head, spouse, children, and relative, which was available in the first three waves and is of interest to us. In addition, wave 4 does not provide information on labor time in weeks. In waves 1, 2, and 3, the labor file has information on the number of weeks, days, and hours of work, disaggregated by household head, spouse, children, and relatives. These shortcomings in how the data were collected in wave 4 make it impossible to construct labor supply for household heads, spouse, children, and relatives in similar ways we were able to do so in the first three waves.

For our analysis, we derived the total hours worked by household heads by combining the hours worked on each plot. The hours worked on each plot is derived using information from the harvest survey. Information is collected on the number of hours worked on the plot, the number of days worked on the plot, and the number of weeks worked in the season on the plot. The data set also includes a number of specific household and individual characteristics that we include as controls.Footnote 25

To measure conflict exposure, we turn to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) by Raleigh, Hegre, and Carlson (Reference Raleigh, Linke, Hegre and Karlsen2010). This database focuses on a range of violent and nonviolent actions by governments, rebels, militias, communal groups, political parties, rioters, protesters, and civilians. It records event date, event type, location, and conflict fatalities and covers the period from 1997 to 2021 for all countries including Nigeria.Footnote 26 Following Odozi and Oyelere (Reference Odozi and Oyelere2019), we use these data to construct two measures of conflict exposure using fatalities at the local government area level. We also create a conflict event measure using the ACLED data. This measure captures all the conflict events in a LGA. Figure 1 provides a map of accumulated conflict events in LGA in Nigeria from 1997 to 2018. We present these data visually in Figure 1 to provide readers with a visual representation of the intensity and widespread nature of conflict events in Nigeria. Notice that most parts of Nigeria have experienced violent conflict events, and a fewer number of locations have had a very high number of conflict events over time.

Fig. 1. Conflict Events in Nigeria between 1997 and 2018.

Figure 2 shows conflict events in different periods of time over 10 years. This evolution-style map of conflict events shows that the number of conflict events has been increasing in different communities in Nigeria and the location of these events exhibits significant heterogeneity over time.Footnote 27

Fig. 2. Evolution of Conflict Event in Nigeria 1997–2018.

While conflict events have been frequently used by many past researchers to proxy for conflict exposure, we do not follow this approach. We are interested in the intensity of impact, which we argue is better captured by violence-related fatalities. Hence for measuring recent exposure in our analysis, we consider the total number of conflict-related fatalities in the local government in the year of the survey plus the two years preceding it. We choose to construct our recent measure as noted above because households’ responses to shocks such as violence related fatalities are not knee jerk and are too often delayed.Footnote 28 To capture these potential nuances in how violent conflict exposure directly or indirectly can alter decision making, we use conflict deaths over a wider range of time to measure recent intensity of exposure. For the long-term measure of conflict, we consider the total number of conflict related fatalities in the local government area in the year of the survey plus all other preceding years of available data (1997 to the year of the survey). We normalize these two measures using projected population figures for the local government for the respective survey years to better capture the intensity of exposure in a community. For example, 10 conflict related fatalities in a low-population LGA is clearly going to have more impact than 10 fatalities in a high-population LGA.Footnote 29

Figure 3 provides a mapping of total violent fatalities in Nigeria from 1997 to 2018. This map provides extra support as to why we take the approach of estimating the average effect of violent conflict in Nigeria. Notice that a significant part of the country has been exposed to violent conflict as captured by fatalities in different parts of the country. Figure 3 also highlights that the zones with the most intense conflict exposure in Nigeria are the North East, the South South and the North Central parts of Nigeria. Figure 4 shows four maps of Nigeria designed to capture how conflict fatality has evolved over the 2008–2018 period. Notice over time that not only has the locations experiencing fatalities increased, the areas with the most intense conflict exposure in terms of fatalities have changed.

Fig. 3. Conflict Fatalities in Nigeria between 1997 and 2018.

Fig. 4. Evolution of Conflict Fatalities in Nigeria 1997–2018.

Figures 1–4 provide further support for our approach. We focus on estimating the overall effect of conflict in Nigeria given its widespread prevalence rather than focus solely on the effect of particular conflicts on households exposed to it. Apart from the ACLED data, we also made use of information on rainfall and population density in our analysis. We obtained rainfall data from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) annual statistics for 2016. Information on land surface area and population for each state was sourced from the National Population Commission.

Results

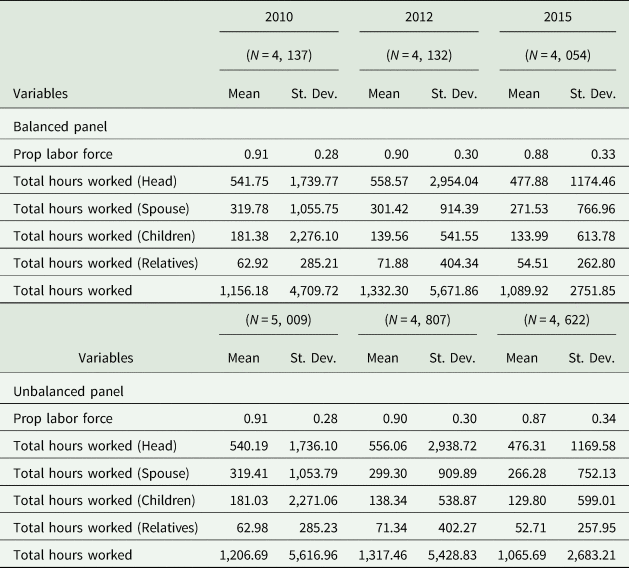

Tables 1 and 2 present summary statistics of the variables used in the regression analyses. In Table 2, we present summary statistics of some of our key dependent variables for the balanced and unbalanced panel data. Table 2 shows that 91 percent of farm household heads supplied labor in 2010, but this figure declined slightly in 2012 and 2015, respectively, to 90 percent and 87 percent. Total labor hours supplied by household heads to harvest season farm work were on average 540.19 h in 2010. This share increased in 2012 to 556.06 h but declined to 476.31 h in 2015. We find a substantial decline in total hours of work for spouses and children across years. While spouses supplied 319.41 h of labor in 2010, hours declined, respectively, to 299.30 h and 266.28 h in 2012 and 2015.

Table 1. Summary statistics

Table 2. Summary statistics additional variables

Table 1 also shows that on average, conflict exposure increased from 2010 to 2015. An interesting observation from Table 1 is the percentage of households that are exposed to idiosyncratic shocks in the past year. This share increased between 2010 and 2012 but decreased to its 2010 levels by 2015.

The results of our baseline model (Heckman selection) can be found in Tables A1 and A2 of the appendix of the article. In Table A1, we focus on the effect of the recent violent conflict exposure on the hours worked for farm households, while in Table A2, we summarize the results focused on the effects on labor supply of accumulated long-term conflict exposure. Part A of these tables presents results for select variables from the participation equation and part B summarizes select results for the main outcome equation. In columns (1) of both tables, we present the result for the household head. In columns (2), we present the results for spouse hours, column (3) children, column (4) relatives. In column (5), the result for the total hours worked for the entire household is presented.Footnote 30

As we noted in our empirical section, we include accumulated conflict events in an LGA from 1997 to the survey year in our participation equation, but we exclude it from our outcome equation. We worry about the estimated effects from this model because the excluded variable, though negative, is not statistically significant in our selection equation in both Tables A1 and A2. This finding casts a doubt on the validity of this exclusion restriction since the variable should have a nontrivial impact on the probability of selection. Furthermore, the Wald test of the independence of equations suggests that using a Heckman selection model may not be necessary as we fail to reject the hypothesis that ρ = 0 in all but one subsample (relatives). Hence, the hypothesis that the two equations are independent cannot be rejected. Given the aforementioned limitations, we review the Heckman results with caution as these estimates could be biased and not consistent.

The results from the outcome equation in Tables A1 and A2 part B column (5) suggest that an increase in exposure to conflict is negatively correlated with hours of farm family labor supplied. To get at the potential heterogeneity within the household in this effect, we focus on the results summarized in columns (1)–(4). These results suggest that an increase in exposure to conflict is correlated with a statistically significant decline in the hours the household head worked on the farm. We do not note any significant effects for the hours worked by spouse, children, and relatives.

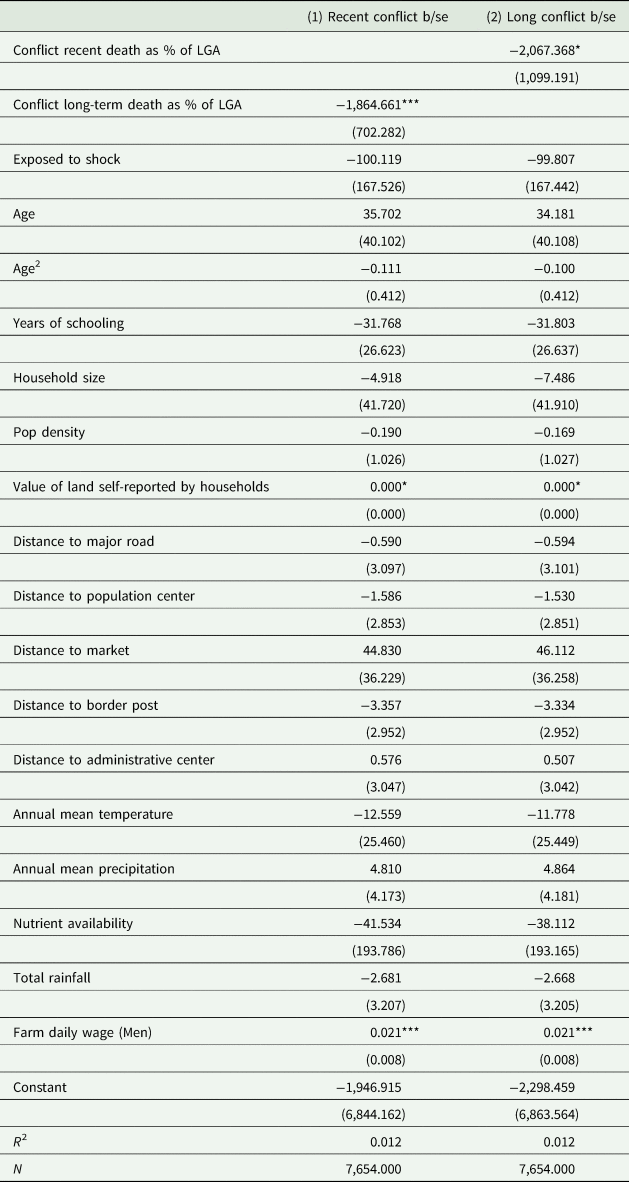

In Tables 3 and 4, we present the labor supply estimates using our fixed effects (FE) model, which is our preferred empirical strategy. As noted in the empirical section of the article, the FE model controls for time invariant unobservable household-level characteristics, which attenuates bias in the estimated effects of conflict on labor supply (hours worked). To further reduce the potential bias linked with time-varying unobservables correlated with our conflict measure and farm labor supply, we include several controls. In particular, we include in our analysis several time varying controls such as idiosyncratic shocks, health-related variables, controls for time-varying social characteristics of the LGA, precipitation, average farm wages, and population density. We also include year and zone fixed effects and zone and year interactions.

Table 3. The effect of violent conflict on a family total labor supply during harvest season

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. For a description of the variables, see Table 1. The following variable estimates are not shown:time fixed effect, zone fixed effect, and zone and time interaction variables. Also, the health variables are not shown (suffered from illness/injury, admitted in hospital or health facility).

In Table 3, we present the results for total hours worked for the entire family on plots in the harvest season. In column (1) of Table 3, we present the results using the recent conflict measure, and in column (2), we present the results using the long-term measure of conflict. The results suggest a significant negative effect of conflict exposure on the total hours of labor on the farm for a family. The results of the test for heterogeneity across family members are summarized in Table 4. In Column (1) of Table 4, we present the results for the model with the number of hours worked by the household head as the dependent variable. In column (2), the dependent variable is the number of hours worked by spouse. In column (3), the dependent variable is hours worked by children and in column (4), the dependent variable is the hours worked by relatives. In Panel A, we present the relevant estimates using the recent exposure to conflict measure, and in Panel B, we present the estimates using the long-term accumulated exposure to conflict measure. The results summarized in Table 4 suggest that exposure to conflict (recent or over a long time), reduces the hours worked significantly for household heads. We do not find any significant effect on labor of spouse, children or relatives. Given this finding, it is reasonable to infer that the noted decline in the total farm labor supply of households is driven by a decline in the labor supply of household heads.

Table 4. The effect of violent conflict on the total hours of labor supply during the harvest season

se: statistics in parentheses.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Note: For a description of the variables, see Table 1. The following variable estimates are not shown:time fixed effect, zone fixed effect, and zone and time interaction variables, distance to major road, distance to pop center, distance to market, distance to border post, distance to administrative center, annual mean temperature, annual precipitation, nutrient availability, total rainfall, and population density. Also, the health variables are not shown (suffered from illness/injury, admitted in hospital or health facility).

Comparing our preferred estimates with our baseline model (Heckman), we notice that the estimates using the Heckman model are mostly consistent in inference with the results from our preferred model (fixed effects). In particular, for families’ total labor supply, our fixed effects model suggests significant negative effects of both recent and long-term conflict exposure. In contrast with the Heckman model, we only find significant negative effects on total family labor supply using the long term measure. For household heads, both model estimates suggest that exposure to conflict (recent or over a long time) reduces hours supplied on the farm significantly. For hours worked by children and spouse, both methods do not find evidence of significant negative effects of recent or longer term exposure to conflict. For hours supplied on farm by relatives, we also note no significant effects using our preferred method. However, the estimates using the baseline model suggest a significant negative correlation with the longer-term exposure measure but not using the recent exposure measure.

It is worth noting that our results are in contrast with Adelaja and George (Reference Adelaja and George2019a) who do not find a significant effect of the Boko Haram conflict on the total family hours supplied. In contrast, we find significant negative effects of both recent and longer-term violent conflict exposure on the total family hours supplied using our preferred estimation method. It is important to note that the aforementioned article focused solely on the Boko Haram conflict, while we focus on any violent conflict in Nigeria from 1997 to 2015. This could explain the differences in our findings. Also, Adelaja and George (Reference Adelaja and George2019a) measure conflict exposure using conflict events that we do not use. Our argument for not using conflict event counts as a measure of conflict exposure is that they may not be as effective for capturing the intensity of exposure. A conflict event in an LGA where there is violence or riots but no deaths is different in terms of impact from a conflict event in an LGA that leads to multiple fatalities. This is why we measure conflict exposure using deaths via armed conflict, and to capture the intensity, we normalized fatalities with the LGA population.

How can we interpret the results in Tables 3 and 4? For total family labor supply, our results summarized in Table 3 suggest that a 0.01 percentage point increase in recent conflict exposure leads to a decrease of approximately 20.7 h of the total family farm labor supply. While the accumulated impact of past conflict exposure is approximately 18.6 h of decrease. These are significant impacts of conflict. Moreover, some states in the north eastern part of Nigeria and the north central parts of Nigeria have experienced conflict increases far greater than this. For example, between 2012 and 2015, the mean recent conflict exposure increase in the North Eastern part of Nigeria was 0.043. This significant increase was linked primarily with the Boko Haram insurgence. If we calculate what such an increase in conflict will lead to using our FE model estimates, we find that a 0.043 percentage point increase in recent exposure suggests an approximately 88.9 h decline in the total family farm labor supply. A decline of such magnitude in labor supply for farm households is substantial.

Our findings suggest heterogeneity in effect across household members with significant effects solely for household heads. For household heads, the results in Table 4 suggest that a 0.01 percentage point increase in recent exposure to conflict leads to an approximate decrease of 7.3 h worked in the harvest season. Similarly, a 0.01 percent increase in accumulated long-term exposure to conflict leads to an approximately 7 h of decrease in labor supplied in the harvest season by the household head. These are also significant impacts of conflict. Again if we consider the mean change in conflict exposure in the north eastern zone between 2012 and 2015 and do similar calculations, a 0.043 percentage point increase in recent conflict exposure reduces farm hours by the household head by 31.3. This decline in labor supply is also significant.Footnote 31

Summary and conclusion

In this article, we examine the average impact of conflict in Nigeria on farm labor supply of agricultural households. We focus on two related questions: first, does recent exposure to violent conflict affect the total family labor hours and is there heterogeneity in effect on the number of hours worked by the household head, spouse, children, and relatives? Second, is there evidence that long-term accumulated exposure to conflict affects the total family labor hours supplied and is there heterogeneity in effect on the number of hours worked by the household head, spouse, children, and relatives? We attempt to answer these questions combining household survey panel data for Nigeria with ACLED data, exploiting a fixed effect estimation strategy.

Our results suggest that conflict negatively affects the total farm labor supply of a family. We also note heterogeneity in this effect across household members. In particular, we find that violent conflict leads to a decline in the farm labor supply of the household head, but we do not find any significant negative effects on the labor supply of children, spouse, and relatives. Simple back-of-the-envelope calculations based on our estimates suggest that the impact on farm household labor supply could be severe in magnitude in areas with sudden spikes in violent conflict, for example, the Boko Haram crises in the north eastern region of Nigeria, the farmers–herdsmen conflict in the north central region of Nigeria, and the current crises in southern Kaduna. Finding significant negative effects of conflict on total family labor supply is new, given that Adelaja and George (Reference Adelaja and George2019a) do not find significant effects of the Boko Haram conflict on family labor supply. While both articles use similar methodology, our analysis differs from theirs in many ways. First, we look at the effect of any recent conflict in Nigeria (focused on exposure to conflict in the last three years), while they consider only one year. In addition, we focus on the average treatment effect of any type of violent conflict, while they focus on the effect of Boko Haram. Finally, we measure exposure to conflict using fatalities normalized with population in LGA, while they focus on the count of conflict events.

Odozi and Oyelere (Reference Odozi and Oyelere2019) provide evidence of the negative impact of violent conflict on income, incidence, severity, and depth of poverty in Nigeria. The results in our article provide one possible pathway for their findings. In particular, if agricultural households affected by violent conflict are forced to decrease their total labor hours worked, then assuming no substitution to other activities, their incomes will decline, and the probability of their slipping into poverty will increase.

It is important to mention one caveat when using ACLED fatality data. In particular, the collectors of the ACLED dataset are very careful in attributing any death to being linked to armed conflict. Many deaths that could have been caused by armed conflict may not have been included in the data if there was uncertainty and lack of clear information on whether the deaths were caused by armed conflict or other factors. This limitation in the reporting of deaths by armed conflict in ACLED data can create a potential downward bias in the estimated effects. Hence, the actual effect on the hours worked could be greater.

While our article provides answers to the question we focused on, there are still so many unanswered questions related to conflict in Nigeria that are relevant but we are unable to address in our article for a number of reasons, including data limitation and article scope. We hope to explore some of these questions in future work. In particular, the question whether small holder farmers are making labor substitution from agriculture to some other labor market activities or whether they are simply reducing the overall hours of labor. We hypothesize the latter based on Odozi and Uwaifo Oyelere (Reference Odozi and Oyelere2019) who suggest a decline in welfare on average linked to conflict. However, concrete analysis to confirm this hypothesis is one area of potential future work. Also, exploring the pathways through which conflict affects labor supply is important. We discuss potential pathways in our article, but we are not able to identify which pathway is at work in our survey period. While we can hypothesize the more important pathways using prima facie evidence, the limitations of the LSMS data make it impossible to provide concrete answers to the exact channels or pathways. Another potential extension to our article is to test for heterogeneity in the effect of conflict on labor supply based on the type of conflict.

Finally, it is worth noting that while the FE model mitigates biases in estimated effects, it does not deal with possible time-varying unobservables that could be correlated with our measures of conflict, and also correlated with our dependent variable. Such variables if they exist can confound estimated causal effects. We attenuate this possible source of bias by including as many time-varying controls in our regression analysis as are available in our data. Two important control groups we include are controls for idiosyncratic shocks and controls for economic, weather, and social conditions in an LGA. However, despite these aforementioned controls and others that we include, we do not claim that we completely eliminate the potential for this source of bias.

As stated at the beginning of this article, a good portion of Nigeria's labor force is employed in agriculture and it still remains the largest sector of the Nigerian economy. The agricultural sector is particularly vulnerable to violent conflict and, therefore, investigating the impact of conflict in this sector is necessary. Given the significant lingering negative effect of conflict on agricultural labor supply noted in our article, there is a need for Nigeria's leadership to do more to curb the growth of violent conflict in Nigeria. This is a social justice issue as rural vulnerable agricultural households disproportionately bear the welfare and labor supply effects of violent conflict.

Designing policies in Nigeria aimed at alleviating both the short- and longer-term micro and macro effects of reductions in labor supply in agriculture is paramount. As policy design can be challenging, partnerships between academics and policy makers aimed at creating policy alternatives and testing their effectiveness is one potential strategy the Nigerian governments may consider to facilitate effective targeted policy initiatives.

Data availability statement

Data analyzed in this study were a reanalysis of existing data, which are openly available at locations cited in the reference section of the article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. We also appreciate the feedback we received from conference participants at the 2020 ASSA Annual Meetings.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Appendix A.

Table A1. The Effect of Recent Violent Conflict on the Total Hours of Labor Supply During the Harvest Season (Heckman Model)

Table A2. The Effect of Long Violent Conflict on the Total Hours of Labor Supply During the Harvest Season (Heckman Model)