CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

A novel program was implemented to enhance the care provided by paramedics to patients with palliative goals of care.

What did this study ask?

This study asked about patient experience with the program and the comfort and confidence of paramedics to deliver this care.

What did this study find?

Patients praised the compassion of paramedics and staying home, and paramedics strongly agreed palliative care should be in their practice.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Knowledge of this program will support similar initiatives and increase access to care and death outside of the hospital setting.

INTRODUCTION

While desired by many, the provision of palliative and end-of-life care at home is not without challenges.Reference Agar, Currow, Shelby-James, Plummer, Sanderson and Abernethy1 Crises can occur for physical, emotional, and existential reasons, and often involve patient and family/caregiver.Reference Schrijvers and van Fraeyenhove2 Common concerns include fearReference Smith, Fisher and Schonberg3 and managing sudden uncontrolled symptoms.Reference Osse, Vernooij-Dassen, Schadé and Grol4, Reference Munck, Fridlund and Martensson5 Despite an expressed preference for care at home, acute medical events and uncontrolled symptoms are the top reasons why this may not occur, resulting in transport to the emergency department (ED),Reference Smith, Fisher and Schonberg3 hospital, or hospice facilities.Reference Evans, Cutson, Steinhauser and Tulsky6 Paramedics facilitate over half of ED visits for patients receiving palliative care,Reference Lawson, Burge, Mcintyre, Field and Maxwell7 many of which are avoidableReference Wallace, Cooney, Walsh, Conroy and Twomey8, Reference Barbera, Taylor and Dudgeon9 and for symptoms that paramedics are skilled in managing.

During crises, patients/caregivers often call for paramedics, particularly during times of limited support, such as nights and holidays, in the absence of healthcare providers, and when there is a sudden increase in need (e.g., the patient unexpectedly worsens).Reference Carron, Dami, Diawara, Hurst and Hugli10, Reference Pettifer and Bronnert11 Patients are commonly seeking symptom management or comfort care rather than traditional paramedic interventions of resuscitation and transport to the hospital.Reference Lord, Récoché, O'Connor, Yates and Service12 Responding to palliative crises can be challenging for paramedics, because goals of care are often not congruent with paramedic training and protocols.Reference Lord, Récoché, O'Connor, Yates and Service12–Reference Wiese, Bartels and Ruppert14 Indeed, paramedics themselves recognize the challenges of palliative care, citing conflicting/unclear goals of care, family dynamics, legal issues, and fear of working outside of standard guidelines.Reference Lord, Récoché, O'Connor, Yates and Service12, Reference Wiese, Bartels and Ruppert14–Reference Stone, Abbott, McClung, Colwell, Eckstein and Lowenstein16

There is growing recognition of the potential role of paramedics in better supporting symptom crises in palliative care patients, without the ED.Reference Lawson, Burge, Mcintyre, Field and Maxwell7, Reference Lamba, Schmidt and Chan17 Paramedic practice in Canada is experiencing significant growth in areas that shift away from acute trauma/emergency management.Reference Tavares, Bowles and Donelon18 The study team led the implementation of an innovative program, Paramedics Providing Palliative Care at Home, in two provincial emergency medical services (EMS) systems, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. The program includes a clinical practice guideline (CPG) specific to palliative care, adding new medications and care in the home without transport to the ED. The study team worked with Pallium Canada to develop and deliver education (LEAP Mini for Paramedics, Pallium Canada) to all paramedics in these two provinces. Further, we expanded and upgraded a database that housed individualized care plans, including goals of care (the Special Patient Program in Nova Scotia and Integrated Palliative Care Program in Prince Edward Island) to make them accessible to paramedics responding to a call.

The primary objectives of this study were to determine the impact of the program in two parts: Part A examined patient and family/caregiver satisfaction, and Part B measured paramedic comfort and confidence with the delivery of palliative care support.

METHODS

Setting

The Nova Scotia ground ambulance service covers a population of 1 million, with over 160,000 requests for service annually. The Prince Edward Island system supports close to 150,000 people and over 17,000 calls per year.

Ethics

The Nova Scotia Health Authority (File #1021421 for Part A: Patient/family, and #100296 for Part B: Paramedic) and Prince Edward Island (not numbered) approved this study.

PART A: PATIENT/FAMILY

Design

A mixed-methods approach using a mailed survey and telephone interviews gathered patient (family/caregiver if patient was unable to respond) perspectives.

Data collection

A prospective, cross-sectional survey (Online Appendix, Figure 1) was mailed with a postage-paid envelope to patients registering in the Special Patient Program or Integrated Palliative Care Program between August and November 2016. The survey included questions about why the patient/family was interested in the program and anticipated benefits. Completing and returning the survey served as implied consent.

Figure 1. Paramedic comfort and confidence delivering palliative care (Part B).

One study team member (MH) conducted telephone interviews concurrent with the survey, between June and September 2016 and post-paramedic encounters in January to February 2016 by enrollees of the provincial registries. The lag between the encounter and interview allowed time for grieving. The interviews were conducted with consecutive respondents using a previously validated semi-structured interview guide, modified for use in the EMS context, including closed and open-ended questionsReference Teno, Clarridge, Casey, Welch, Wetle, Shield and Mor19 (Online Appendix, Figure 2). Eligible participants who were called with no response were called a second time. Participants provided verbal consent prior to the interview commencement. The interviewer took detailed notes.

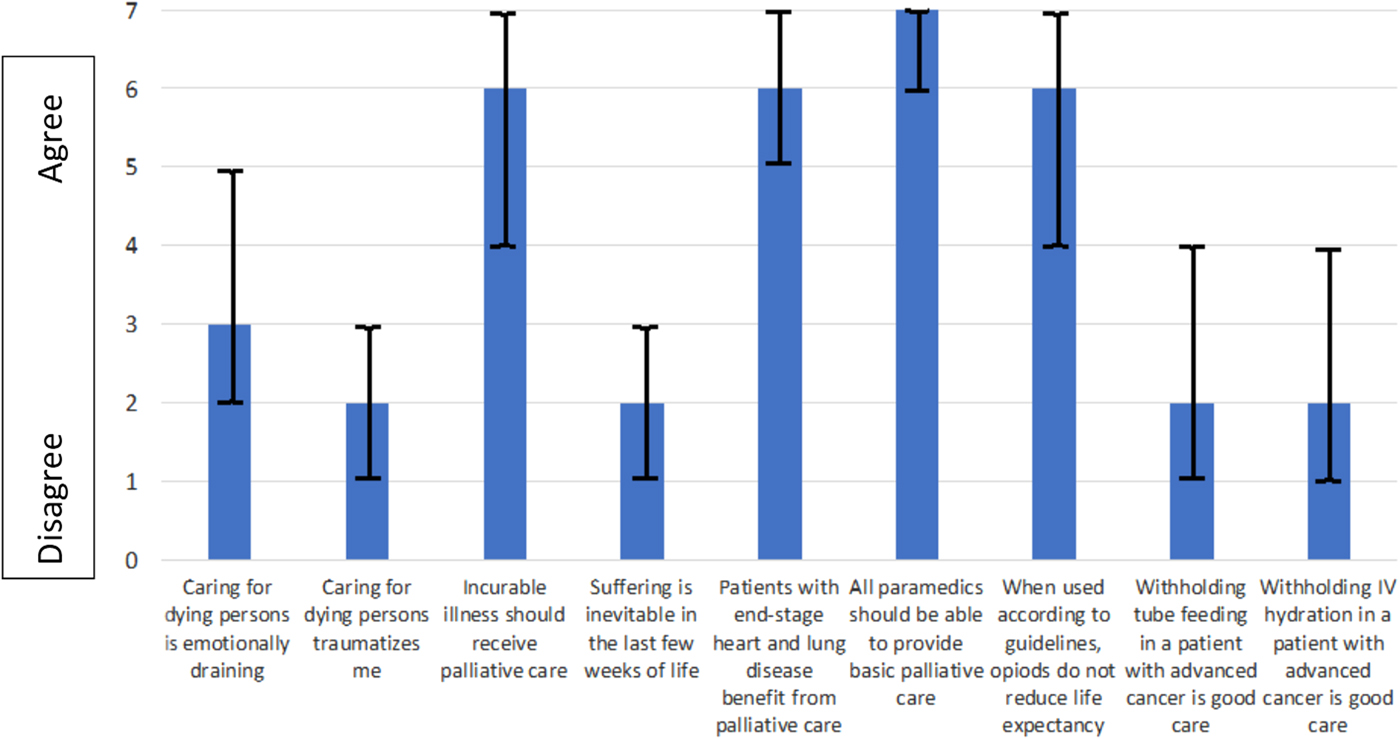

Figure 2. Paramedic attitudes (Part B) toward palliative and end-of-life care (median and IQR)

Data analysis

Respondent characteristics were collected as continuous variables and reported descriptively. Open-ended questions were analysed by a thematic content analysis. One author (MH) did open coding using QSR NVivo 11 to form a code structure, which was reviewed by a second author (AC). Codes were combined and sorted into categories and, ultimately, themes.

Audit trails and reflections, including interview notes, methodological decisions, data analysis, and group reflections, were maintained to assure study rigor. Credibility was facilitated through regular debriefing by team members as data were collected and coded, and as themes emerged. Direct quotations (edited for grammar) ensure that the perspectives of the participants were clearly represented.

PART B: PARAMEDICS

Design

We used a prospective pre- versus post-intervention design. All ground ambulance paramedics in the two provinces were invited to participate in the voluntary surveys at two time points: pre-launch, and post-launch (12 months on Prince Edward Island and 18 months in Nova Scotia).

Data collection and management

After registering for LEAP Paramedic, paramedics received an email from Pallium Canada to participate in the pre-course survey. Although the original intent was to link the pre- and post-surveys using a unique identifier, respondents reported challenges with the Portal and the post-course survey used Opinio (©Object Planet, Norway).

Measures

Questions included Pallium Canada's standard pre- and post-course reflections, including attitudes to a palliative care approach; additional items related to comfort and confidence were added by the study team.

Comfort and confidence were measured on a 4-point Likert scale, used previously by our team.Reference Walker, Jensen, Leroux, McVey and Carter20 Paramedics described their comfort/confidence in providing palliative or end-of-life care with or without transport to the hospital, and provided free text feedback. Attitudes were evaluated using a modified version of the LEAP Attitudes to Palliative and End-of-Life Care Survey on a 7-point Likert scale (pre-implementation only).

Analysis

Demographic variables were collected as continuous or categorical variables and reported by the mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range [IQR]). Likert data were treated as continuous variables. Pre- and post-scores were compared in R (version 3.2.5), using a Wilcoxon-ranked sum test.

Sample size

A sample size of 242 was required to detect a 0.5 change in confidence on a 4-point scale, assuming alpha is set at 0.05 and beta at 0.8. The team attempted to oversample, with expectations of a response rate closer to 50% (n = 500).

RESULTS

Part A: Patient and family experience

Enrolment survey

A total of 225 enrolment surveys were distributed in both provinces; 67 (30%) were returned. Of these, 49 (73%) were completed by the family. Demographics are summarized in the Online Appendix, Table 1. Three themes emerged, as described in the following sections.

Table 1. Patient/family experience of paramedic care (Part A)

Fulfilling care wishes

The most common theme (approximately half of the respondents) was that registration in the program helped families feel more confident fulfilling wishes for a preferred location of care. For those with a preference for care at home, they described hospital avoidance, particularly the ED, as an anticipated benefit. As described by one patient:

I have terminal cancer and wish to spend as much of my remaining time at home. This program will help me to remain in my home while enjoying the highest quality of life possible, for as long as possible.

Family/caregiver peace of mind

Peace of mind was described in terms of the knowledge that paramedics would respect care wishes and that the program was available to support caregivers at home if an unexpected need arises.

It is a great source of comfort to know that help is available without transporting the patient to the hospital. Medical assistance, advice, comfort, crisis intervention. This increases my sense of general well-being.

Feeling prepared for emergencies

Families discussed the 24/7 availability of the service, and that it could be relied upon. As put by one family member, “the care you need, when you need it.” Having their situation and goals of care known ahead of time was a relief to families as they feel more prepared for emergencies.

Being enrolled in the program will help my mother because the EMS team has better knowledge of her needs and wishes. It will also relieve the extra stress on me, just knowing this is all set up ahead of time.

Post-paramedic encounter interview

Patients/families with a paramedic encounter were phoned: 8 declined, 22 had disconnected telephones, and 32 were unanswered calls after two attempts; 18 completed the interview. Demographics are summarized in the Online Appendix, Table 2 and descriptive responses in Table 1. Quality of care was rated as “excellent” by 14/18 families, and all indicated that symptoms were improved. Four themes emerged and thematic saturation was reached with little divergence of comments.

Table 2. Paramedic survey (Part B) demographics

Professionalism and compassion of paramedics

A theme highlighted by a majority of respondents was the high level of professionalism and compassion of the responding paramedics. Many families described the paramedics as going “above and beyond.” Respondents commented on the paramedics’ skills in listening, understanding/assessing the situation, providing clear explanations about what was going on, and providing helpful treatments/interventions. Many described this professional care extending not just to the patient, but to family/friends present.

The service was phenomenal. The paramedics explained everything. I can't speak highly enough about the care they gave her. They explained what they were doing and why, so I knew what to expect and what was going to happen. The care, it was excellent, off the chart. I can't praise this service enough.

24/7 Availability

A predominant theme was the comfort families felt knowing that the program was available 7 days a week, night or day, even for multiple visits. Some families described general worries about what “might” happen over the course of the illness; knowing that paramedics would come to support them relieved some distress.

This was my only comfort, knowing I could call paramedics. They made it very clear to us that if we weren't comfortable, we could call them, doesn't matter if it was once or five times. They said ‘we will be here.’ It's a lot of comfort.

Relief of symptoms

Some family members highlighted the ability of paramedics to manage uncontrolled symptoms and provide psychosocial supports.

When he can stay home, it helps a lot. We made the initial call, thinking he would have to go to the hospital, but they relieved his symptoms to the point that he could stay home.

They were here within 15 minutes. They came … but she was dead. They kept me company until the others arrived.

A plea for program continuation

Families commented on the large impact that the program had and expressed a desire to see the program continue, for themselves and others.

My family, they were like ‘wow’ – we were all 100% happy with it. Just keep this going the way it is, and don't ever take this program away.

What would you have done without the program?

In the absence of the program, seven families said they would have been in the ED and highlighted the challenges such as bad weather or equipment (e.g., wheelchairs), as well as concerns about moving the person.

I would have had to help him out of bed and try to get him to the hospital. One time, it was during a blizzard so that would have been impossible, but they were able to come to us. I couldn't get him to the ED but paramedics came – just their presence was amazing.

Part B: Paramedic comfort and confidence

Table 2 summarizes respondent demographics. Sex and level of certification are reflective of the overall paramedic population. Response rate for pre-launch survey was 235/1255 (18.7%) and post-implementation 267/1255 (21.3%).

Figure 1 summarizes the change in comfort and confidence pre- versus post-implementation. An overall shift in the positive or rightward direction can be seen for many of the questions. Specifically, comfort in providing palliative care improved after the intervention; responses of “very comfortable” increased from 26% to 47%. Responses of “very comfortable in providing palliative care without transport” increased from 22% to 44%. Feeling confident that they have tools to provide palliative care increased from 41% “somewhat” and 7% “very confident” (48% positive), to 52% “somewhat” and 23% “very confident” (85% positive responses). Confidence to do this without transport increased from 33% “somewhat” and 6% “very confident” (39% positive), to 47% “somewhat” and 24% “very confident” (71% positive). Testing differences in median and range of scores is another way of comparing pre and post. Where 4 = very confident, improvements were reported in confidence in having the tools to deliver palliative care with (median [IQR] pre = 2 [2,3], post = 3 [3,3], p = < 0.001) and without transport to the hospital (median [IQR] pre = 2 [2,3], post = 3 [2,3], p = < 0.001).

Responses to attitudes questions, scored on a Likert scale with 7 being “strongly agree,” are shown in Figure 2. Respondents strongly agreed that all paramedics should be able to provide basic palliative care (median = 7 [IQR 6, 7]) and that a patient with an incurable illness should receive palliative care (median = 6 [IQR 4, 7]).

Thematic analysis of open-ended questions revealed that paramedics describe palliative care as rewarding. Additional experiential training was recommended, as well as a continued expansion of the primary care paramedic (PCP) role. Three themes emerged and are summarized in Table 3 with illustrative quotes.

Table 3. Paramedic survey (Part B) emerging themes and supporting quotes

DISCUSSION

This novel program was a purposeful modification of system design in response to a recognition that paramedics respond to palliative symptom crises and traditional protocols and training do not support them to meet this need.Reference Lord, Récoché, O'Connor, Yates and Service12–Reference Wiese, Bartels and Ruppert14, Reference Carter, Earle, Gregoire, MacConnell and Frager21 The ultimate goal was to improve the patient/family's experience of care by equipping the emergency service that they rely on with adequate resources. Many patients/families are well connected to primary care, specialists, and/or formal palliative care teams; however, they still call 9-1-1 for a variety of reasons such as the need for a rapid response, the variable availability of their usual care team, and, occasionally, they report just panicking. Paramedic services are designed to be available 24/7 in all urban, rural, and remote areas, and were already being called to provide support to these patients/families. This program sought to enhance the service that paramedics could offer as part of the broader healthcare team.

Paramedics’ role as members of a broader healthcare team is evolving.Reference Tavares, Bowles and Donelon18 As such novel roles emerge for paramedics, it is crucial to monitor comfort and confidence with such practices, and to seek paramedic opinion. In this case, paramedics reported a moderate level of comfort with the concept of palliative care pre-launch, but lower confidence in having the necessary resources to provide such care, with or without transport to the hospital. Shifts post-launch into the “very comfortable” and “very confident” categories are seen in Figure 1. Importantly, paramedic attitudes toward palliative care are very favourable. Agreement that patients with an incurable illness should receive palliative care was very high, suggesting that paramedics believe in the concept of palliation. Further, paramedics not only support the concept, but also they believe it should be part of the scope of practice of paramedics. There are a few cautions with interpreting these data; surveys were optional, which may have generated a selection/response bias. At 18 months post-launch, the database was not fully functional, which may have limited comfort and confidence, as would low call volumes. This represents the comfort and confidence of two provinces only, one of which (Nova Scotia) already has an established suite of nontraditional, non-transport programs, which may increase the baseline comfort. Importantly, however, gathering the perspective of the paramedics and choosing the elements of the multi-faceted intervention was critical; providing tools, skills, practice, and adequate knowledge of care wishes and system-level support is essential to enabling this new role.

From a patient and family perspective, the results suggest that the program has been successful in reducing family stress and enabling them to fulfill care wishes. The act of registering in the program and the knowledge that paramedics will be available 24/7 provide comfort and relief for families in times of stress. For families/caregivers, common concerns include fearReference Phillips and Reed22 and managing sudden uncontrolled symptoms.Reference Osse, Vernooij-Dassen, Schadé and Grol4, Reference Munck, Fridlund and Martensson5 However, timely support and a prompt response provide reassurance, increases caregiver confidence to cope, and provides a sense of not being alone.Reference Stajduhar, Martin, Barwich and Fyles23 The fear of the unknown is powerful, and some certainty that you have resources at your disposition, 24/7, is comforting. It would be valuable to confirm what was informally stated, that registering, with no call for assistance ever made, may have increased the possibility of staying at home for end of life.

After an encounter, families report high satisfaction with the care provided. The 24/7 availability of the service, regardless of geography, was again noted, and the relief that knowing prompt assistance was available. Importantly, virtually all respondents highlighted the psycho-social impact of the professionalism and compassion of the paramedics. Finally, it is a powerful statement that the public understood that this was an externally funded project, and were afraid that it might end when the funding drew to a close. They pleaded for continuation of the program and described that they would not have been able to stay home and that their distress would have been much greater in the absence of the program.

There are certain limitations with our data collection. Despite this being a small sample across two provinces, thematic saturation was achieved early with little divergence. Another limitation is the time lapse between paramedic encounter and interview; however, initial attempts to interview closer encounter revealed it was often close to the death, and too soon to discuss the events. This time lapse may also have contributed to the high proportion of disconnected phone numbers. The overall response rate to the enrolment survey is low-moderate, and it is possible that those who declined to respond would voice a different opinion. However, the tone and themes of the findings correlate well with informal and audit feedback. We do not know the perspective of families who have a care experience without registering in this program, or those who registered but never used the service.

Future research will evaluate paramedic/palliative care provider perception of the program and system level impact of implementation, including death/end-of-life care in the preferred location.

CONCLUSION

After the implementation of the multi-faceted Paramedics Providing Palliative Care at Home Program, including a palliative care CPG, new formulary, access to goals of care, and a training program, paramedic comfort and confidence with palliative and end-of-life care improved. Paramedics describe palliative care as an important and rewarding part of their work. The program resulted in high patient/family satisfaction and a positive experience of care. Families particularly note the compassion and professionalism of paramedics. The addition of paramedics to a broader palliative care approach improves the paramedic, patient, and family experience of palliative and end-of-life care.

Competing interests

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer for funding this work and to Pallium Canada for the development of LEAP-Paramedic. We would like to thank the Advisory Group and the paramedics of Nova Scotia and PEI. This work has been presented as a research abstract at NAEMSP 2018 in San Diego, California.

Special thanks to Dr. Lori Teeple, Dr. Erin O'Connor, Dr. Lisa Fisher, Sandee Crooks, ACP; Mark Walker, ACP; Katherine Houde, ACP; Janel Swain, ACP; Louis Staple, ACP; Darcy Clinton, ACP; Shawn Westbury, ACP; and Dr. Jolene Cook for their work in developing LEAP-Paramedic.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2018.497.