1. Introduction

Some of the most fundamental questions about turbulent fluid flows concern space- and time-averaged quantities, such as mean dissipation or transport, and how these quantities scale with control parameters. At parameter values that are accessible to laboratory experiments or direct numerical simulations, mean quantities can be estimated by averaging over a finite-time flow. A different and complementary approach is to mathematically derive upper or lower bounds on infinite-time averages directly from the governing equations. Most bounds of this type have been derived using the so-called background method, which was first applied to the Navier–Stokes equations by Doering & Constantin (Reference Doering and Constantin1992). For an overview of the method, see Chernyshenko (Reference Chernyshenko2022) and Fantuzzi, Arslan & Wynn (Reference Fantuzzi, Arslan and Wynn2022).

The background method lets the time-dependent governing equations be replaced by variational problems, in which integrals are maximised or minimised over time-independent velocity fields. For instance, upper bounds on infinite-time-averaged dissipation at fixed parameter values can be formulated, roughly speaking, as

where

![]() $\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w};\zeta ]$

is a spatial integral whose integrand depends quadratically on an incompressible velocity field

$\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w};\zeta ]$

is a spatial integral whose integrand depends quadratically on an incompressible velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

and linearly on a ‘background profile’

$\boldsymbol{w}$

and linearly on a ‘background profile’

![]() $\zeta$

. In the case of lower bounds, the inner problem is a minimisation over

$\zeta$

. In the case of lower bounds, the inner problem is a minimisation over

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

, while the outer one is a maximisation over

$\boldsymbol{w}$

, while the outer one is a maximisation over

![]() $\zeta$

. A precise version of (1.1) for planar shear flows is derived in § 2.1.

$\zeta$

. A precise version of (1.1) for planar shear flows is derived in § 2.1.

The inner maximum in (1.1) is an upper bound on dissipation for any admissible choice of

![]() $\zeta$

. For some

$\zeta$

. For some

![]() $\zeta$

, this bound is infinity, but for other

$\zeta$

, this bound is infinity, but for other

![]() $\zeta$

, it is finite. The outer minimisation over bounds in (1.1) gives the optimal bound within the background method framework. Optimal bounds generally cannot be found analytically, but they have been computed numerically for a few fluid systems (Plasting & Kerswell Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003; Fantuzzi et al. Reference Fantuzzi, Wynn, Goulart and Papachristodoulou2017b

, Reference Fantuzzi, Pershin and Wynn2018, Reference Fantuzzi, Arslan and Wynn2022). As with direct numerical simulation of fluids, computation of optimal bounds is possible when parameters are fixed to values that are not too extreme, so that the required spatial resolution is not too fine. Most applications of the background method have instead derived suboptimal bounds analytically, which can give bounds applying at all parameter values, including with explicit parameter dependence. Such analytical results are derived by choosing relatively simple

$\zeta$

, it is finite. The outer minimisation over bounds in (1.1) gives the optimal bound within the background method framework. Optimal bounds generally cannot be found analytically, but they have been computed numerically for a few fluid systems (Plasting & Kerswell Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003; Fantuzzi et al. Reference Fantuzzi, Wynn, Goulart and Papachristodoulou2017b

, Reference Fantuzzi, Pershin and Wynn2018, Reference Fantuzzi, Arslan and Wynn2022). As with direct numerical simulation of fluids, computation of optimal bounds is possible when parameters are fixed to values that are not too extreme, so that the required spatial resolution is not too fine. Most applications of the background method have instead derived suboptimal bounds analytically, which can give bounds applying at all parameter values, including with explicit parameter dependence. Such analytical results are derived by choosing relatively simple

![]() $\zeta$

that are suboptimal, then upper-bounding the maximum over

$\zeta$

that are suboptimal, then upper-bounding the maximum over

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

rather than computing it exactly.

$\boldsymbol{w}$

rather than computing it exactly.

For bounds like (1.1) to hold for three-dimensional (3-D) flows, the inner maximisation generally must be over 3-D incompressible velocity fields. Maximising over a smaller class of

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

can make the maximum smaller and thus is not guaranteed to give an upper bound for 3-D flows. A crucial exception occurs when one can show mathematically that a maximum over 3-D velocity fields coincides with a maximum over a class of lower-dimensional velocity fields, in which case, the maximum in (1.1) need only be taken over the smaller class. This dimension reduction is significant for numerical computations of optimal bounds, which become much easier, and it may also improve analytical bounds. The present work concerns how to solve the min–max problem (1.1) over lower-dimensional velocity fields and then show a posteriori that the inner maximum would be the same over 3-D fields, thus avoiding 3-D computations.

$\boldsymbol{w}$

can make the maximum smaller and thus is not guaranteed to give an upper bound for 3-D flows. A crucial exception occurs when one can show mathematically that a maximum over 3-D velocity fields coincides with a maximum over a class of lower-dimensional velocity fields, in which case, the maximum in (1.1) need only be taken over the smaller class. This dimension reduction is significant for numerical computations of optimal bounds, which become much easier, and it may also improve analytical bounds. The present work concerns how to solve the min–max problem (1.1) over lower-dimensional velocity fields and then show a posteriori that the inner maximum would be the same over 3-D fields, thus avoiding 3-D computations.

Here, we consider planar shear flows that are bounded by two parallel walls and are periodic in the other two directions. Such flows may be sustained by boundary conditions, body forcing or both, and we assume that the governing model admits a laminar flow in a single direction. The laminar flow’s direction is called the streamwise direction, the other periodic direction is called spanwise and the bounded direction is called wall-normal. Our particular focus is on models whose governing equations are symmetric under

![]() $180^\circ$

rotation around a spanwise axis. The most prominent models in this family are plane Couette flow and any wall-bounded Kolmogorov flows with forcing profiles that are odd about the mid-plane, including the half-period sinusoidal forcing sometimes called Waleffe flow (Waleffe Reference Waleffe1997). Our main theoretical result is a criterion that applies only to shear flow models with such symmetry. In addition to fully 3-D velocity fields, we will consider fields in only the wall-normal and streamwise directions, meaning there is neither flow nor variation in the spanwise direction; these will be called two-dimensional (2-D). Fields that may be non-zero in all three components but do not vary in the streamwise direction will be called streamwise-invariant (2.5-D). Several past authors have assumed that a maximum over 2.5-D fields in (1.1) coincides with a maximum over 3-D fields. Our aim is to confirm such statements in specific cases without computing any extrema over 3-D fields.

$180^\circ$

rotation around a spanwise axis. The most prominent models in this family are plane Couette flow and any wall-bounded Kolmogorov flows with forcing profiles that are odd about the mid-plane, including the half-period sinusoidal forcing sometimes called Waleffe flow (Waleffe Reference Waleffe1997). Our main theoretical result is a criterion that applies only to shear flow models with such symmetry. In addition to fully 3-D velocity fields, we will consider fields in only the wall-normal and streamwise directions, meaning there is neither flow nor variation in the spanwise direction; these will be called two-dimensional (2-D). Fields that may be non-zero in all three components but do not vary in the streamwise direction will be called streamwise-invariant (2.5-D). Several past authors have assumed that a maximum over 2.5-D fields in (1.1) coincides with a maximum over 3-D fields. Our aim is to confirm such statements in specific cases without computing any extrema over 3-D fields.

Plane Couette flow, which is driven by parallel relative motion of the walls, has been the most-studied application of the background method to the Navier–Stokes equations. This was the first model considered by Doering & Constantin (Reference Doering and Constantin1992, Reference Doering and Constantin1994), who derived an upper bound on dissipation. Normalising the dissipation by its laminar value and by

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

gives a friction factor

$ \textit{Re}$

gives a friction factor

![]() $\varepsilon$

, for which the upper bounds become

$\varepsilon$

, for which the upper bounds become

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

-independent at large

$ \textit{Re}$

-independent at large

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

. The bound

$ \textit{Re}$

. The bound

![]() $\varepsilon \leqslant 2^{-7/2}\approx 0.0884$

of Doering & Constantin (Reference Doering and Constantin1992) is derived by choosing a simple suboptimal background profile

$\varepsilon \leqslant 2^{-7/2}\approx 0.0884$

of Doering & Constantin (Reference Doering and Constantin1992) is derived by choosing a simple suboptimal background profile

![]() $\zeta$

that depends on

$\zeta$

that depends on

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

, then using functional inequalities to upper-bound the maximum in (1.1) over 3-D

$ \textit{Re}$

, then using functional inequalities to upper-bound the maximum in (1.1) over 3-D

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

fields. Slightly improved analytical bounds were then derived by constructing closer-to-optimal

$\boldsymbol{w}$

fields. Slightly improved analytical bounds were then derived by constructing closer-to-optimal

![]() $\zeta$

and upper-bounding the maximum over

$\zeta$

and upper-bounding the maximum over

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

as sharply as possible (Gebhardt et al. Reference Gebhardt, Grossmann, Holthaus and Löhden1995). Still smaller bounds were found at various fixed

$\boldsymbol{w}$

as sharply as possible (Gebhardt et al. Reference Gebhardt, Grossmann, Holthaus and Löhden1995). Still smaller bounds were found at various fixed

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

by numerically computing the inner maxima in (1.1) and implementing the outer minimisation over a restricted class of

$ \textit{Re}$

by numerically computing the inner maxima in (1.1) and implementing the outer minimisation over a restricted class of

![]() $\zeta$

(Nicodemus, Grossmann & Holthaus Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus1997, Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus1998a

,

Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthausb

). Finally, Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003) numerically carried out both the inner maximisation and the outer minimisation over the full class of

$\zeta$

(Nicodemus, Grossmann & Holthaus Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus1997, Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus1998a

,

Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthausb

). Finally, Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003) numerically carried out both the inner maximisation and the outer minimisation over the full class of

![]() $\zeta$

needed, constituting the first optimal bounds of the background method for any fluid flow. Their computed bounds on

$\zeta$

needed, constituting the first optimal bounds of the background method for any fluid flow. Their computed bounds on

![]() $\varepsilon$

approach a constant near 0.008553 as

$\varepsilon$

approach a constant near 0.008553 as

![]() $ \textit{Re}\to \infty$

, which remains the best known bound on dissipation for plane Couette flow. However, the analyses of Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003) and Nicodemus et al. (Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus1998a

,Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus

b

) are not quite complete. In their computations, inner maximisation in (1.1) was generally carried out only over 2.5-D

$ \textit{Re}\to \infty$

, which remains the best known bound on dissipation for plane Couette flow. However, the analyses of Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003) and Nicodemus et al. (Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus1998a

,Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus

b

) are not quite complete. In their computations, inner maximisation in (1.1) was generally carried out only over 2.5-D

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

fields. If this maximum is smaller than the maximum over 3-D

$\boldsymbol{w}$

fields. If this maximum is smaller than the maximum over 3-D

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

, then it need not be a bound for 3-D flows. (A bound for 2.5-D flows alone is not needed since all 2.5-D flows decay to the laminar state, as follows from energy stability analysis using only streamwise and wall-normal velocity components.) These authors maximised only over 2.5-D

$\boldsymbol{w}$

, then it need not be a bound for 3-D flows. (A bound for 2.5-D flows alone is not needed since all 2.5-D flows decay to the laminar state, as follows from energy stability analysis using only streamwise and wall-normal velocity components.) These authors maximised only over 2.5-D

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

because they conjectured that the maximum over fully 3-D

$\boldsymbol{w}$

because they conjectured that the maximum over fully 3-D

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

would give the same value. Plasting & Kerswell (personal communication) and Nicodemus et al. (Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus1997) confirmed this conjecture at a few modest parameter values by carrying out 3-D computations, but they did not show it to be true in general.

$\boldsymbol{w}$

would give the same value. Plasting & Kerswell (personal communication) and Nicodemus et al. (Reference Nicodemus, Grossmann and Holthaus1997) confirmed this conjecture at a few modest parameter values by carrying out 3-D computations, but they did not show it to be true in general.

We derive a criterion for shear flow models that, when it holds, implies coincidence of maxima in (1.1) over 2.5-D fields and over 3-D fields, and likewise for minima in the case of lower bounds. This criterion applies if the governing model has

![]() $180^\circ$

rotational symmetry, but the flow need not be symmetric. We rely on a theorem of Busse (Reference Busse1972) for energy stability of models with the rotational symmetry. Checking our criterion does not require extremising over 3-D fields. Instead, at fixed parameters, one must find the extremum of

$180^\circ$

rotational symmetry, but the flow need not be symmetric. We rely on a theorem of Busse (Reference Busse1972) for energy stability of models with the rotational symmetry. Checking our criterion does not require extremising over 3-D fields. Instead, at fixed parameters, one must find the extremum of

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

and a related functional over 2.5-D fields, extremise another related functional over 2-D fields and then check whether a ratio involving these three extrema is less than unity. In computational examples, the ratio asymptotes to a constant as

$\mathcal{Q}$

and a related functional over 2.5-D fields, extremise another related functional over 2-D fields and then check whether a ratio involving these three extrema is less than unity. In computational examples, the ratio asymptotes to a constant as

![]() $ \textit{Re}\to \infty$

. If the asymptote is less than unity, this gives strong evidence that the coincidence of 2.5-D and 3-D extrema can be ‘extrapolated’ to all

$ \textit{Re}\to \infty$

. If the asymptote is less than unity, this gives strong evidence that the coincidence of 2.5-D and 3-D extrema can be ‘extrapolated’ to all

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

.

$ \textit{Re}$

.

When our criterion is not useful because it is either false or inapplicable, one can instead check directly that maximisers in (1.1) are 2.5-D. As explained later, the min–max problem (1.1) can be rewritten as a minimisation subject to a so-called spectral constraint, which requires all eigenvalues of a certain linear eigenproblem to be non-negative. This eigenproblem depends on the background profile

![]() $\zeta$

and can be solved independently for each pair of the streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers. After solving (1.1) over 2.5-D

$\zeta$

and can be solved independently for each pair of the streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers. After solving (1.1) over 2.5-D

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

and finding the optimal

$\boldsymbol{w}$

and finding the optimal

![]() $\zeta$

, one can check a posteriori that no 3-D fields violate the spectral constraint – that is, one can check the eigenvalues for non-zero streamwise wavenumbers.

$\zeta$

, one can check a posteriori that no 3-D fields violate the spectral constraint – that is, one can check the eigenvalues for non-zero streamwise wavenumbers.

Here, we compute optimal background method bounds on dissipation for both Waleffe flow and Couette flow. In Waleffe flow, dissipation is maximised by the laminar state, so only lower bounds must be computed. In Couette flow, the situation is reversed and only upper bounds must be computed. For both flows, we fix streamwise and spanwise periods of the domain and solve (1.1) computationally up to moderate

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

values over 2.5-D fields, then we verify that the maxima over 3-D fields would coincide. In the case of Waleffe flow, the ratio used in our criterion asymptotes to a value well below unity, suggesting that (1.1) will coincide for 2.5-D and 3-D fields at all

$ \textit{Re}$

values over 2.5-D fields, then we verify that the maxima over 3-D fields would coincide. In the case of Waleffe flow, the ratio used in our criterion asymptotes to a value well below unity, suggesting that (1.1) will coincide for 2.5-D and 3-D fields at all

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

values. In the case of Couette flow, our computations roughly reproduce those of Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003), but up to smaller

$ \textit{Re}$

values. In the case of Couette flow, our computations roughly reproduce those of Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003), but up to smaller

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

and with the spatial periods fixed. The ratio used in our criterion exceeds unity if

$ \textit{Re}$

and with the spatial periods fixed. The ratio used in our criterion exceeds unity if

![]() $ \textit{Re}\gtrsim 254$

, so it cannot validate the assumption of Plasting & Kerswell that maximisers are 2.5-D at all

$ \textit{Re}\gtrsim 254$

, so it cannot validate the assumption of Plasting & Kerswell that maximisers are 2.5-D at all

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

. Instead, we directly check that the spectral constraint holds for 3-D fields over our modest

$ \textit{Re}$

. Instead, we directly check that the spectral constraint holds for 3-D fields over our modest

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

range, which it does. To the extent that this spectrum can be extrapolated, it is consistent with the assumption of Plasting & Kerswell. Additionally, we repeat the bounding computations for Couette flow with further constraints on

$ \textit{Re}$

range, which it does. To the extent that this spectrum can be extrapolated, it is consistent with the assumption of Plasting & Kerswell. Additionally, we repeat the bounding computations for Couette flow with further constraints on

![]() $\zeta$

that guarantee our criterion will be satisfied, giving bounds for 3-D flows that extrapolate to large

$\zeta$

that guarantee our criterion will be satisfied, giving bounds for 3-D flows that extrapolate to large

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

with a prefactor slightly worse than that of Plasting & Kerswell.

$ \textit{Re}$

with a prefactor slightly worse than that of Plasting & Kerswell.

This article is organised as follows. Section 2 formulates the background method for planar parallel shear flows, including three equivalent reformulations with the spectral constraint. Section 3 derives our criterion for extrema over 2.5-D and 3-D fields to coincide in models with

![]() $180^\circ$

rotational symmetry. Section 4 presents our computational applications to Waleffe flow and Couette flow, followed by conclusions in § 5. Appendices A–C provide details of certain arguments and computations, as well as an exposition of the proof of Busse (Reference Busse1972) that underlies our own criterion.

$180^\circ$

rotational symmetry. Section 4 presents our computational applications to Waleffe flow and Couette flow, followed by conclusions in § 5. Appendices A–C provide details of certain arguments and computations, as well as an exposition of the proof of Busse (Reference Busse1972) that underlies our own criterion.

2. Four formulations of the background method for planar shear flows

We consider an incompressible fluid flow bounded by two planar walls located at dimensionless coordinates

![]() $z=-1/2$

and

$z=-1/2$

and

![]() $z=1/2$

, where lengths have been scaled by the distance

$z=1/2$

, where lengths have been scaled by the distance

![]() $d$

between the walls. Body forcing of the fluid and/or relative motion of the boundaries is assumed to point in only the

$d$

between the walls. Body forcing of the fluid and/or relative motion of the boundaries is assumed to point in only the

![]() $x$

direction, so that there exists a laminar flow in that direction. In the nomenclature of shear flows, the

$x$

direction, so that there exists a laminar flow in that direction. In the nomenclature of shear flows, the

![]() $x$

direction is streamwise,

$x$

direction is streamwise,

![]() $y$

is spanwise and

$y$

is spanwise and

![]() $z$

is wall-normal. We assume the flow is periodic in the streamwise and spanwise directions with dimensionless periods of

$z$

is wall-normal. We assume the flow is periodic in the streamwise and spanwise directions with dimensionless periods of

![]() $\varGamma _x$

and

$\varGamma _x$

and

![]() $\varGamma _y$

, respectively, so we let

$\varGamma _y$

, respectively, so we let

![]() $-\varGamma _x/2\leqslant x\leqslant \varGamma _x/2$

and

$-\varGamma _x/2\leqslant x\leqslant \varGamma _x/2$

and

![]() $-\varGamma _y/2\leqslant y\leqslant \varGamma _y/2$

. The Navier–Stokes equations governing the dimensionless velocity vector

$-\varGamma _y/2\leqslant y\leqslant \varGamma _y/2$

. The Navier–Stokes equations governing the dimensionless velocity vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

and pressure

$\boldsymbol{u}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

and pressure

![]() $p(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

are

$p(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

are

where

![]() $ \textit{Re}={d}\mathsf{U}/\nu$

is the Reynolds number,

$ \textit{Re}={d}\mathsf{U}/\nu$

is the Reynolds number,

![]() $\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity,

$\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity,

![]() $\mathsf{U}$

is a dimensional velocity defined either using the boundary conditions or body forcing and time has been scaled by

$\mathsf{U}$

is a dimensional velocity defined either using the boundary conditions or body forcing and time has been scaled by

![]() $d^2/\nu$

. If there is body forcing, it is in the streamwise direction

$d^2/\nu$

. If there is body forcing, it is in the streamwise direction

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

and varies only in the wall-normal direction, so it takes the form

$\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

and varies only in the wall-normal direction, so it takes the form

![]() $f(z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

. The walls are impenetrable, meaning the wall-normal velocity

$f(z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

. The walls are impenetrable, meaning the wall-normal velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol{z}}$

vanishes, and remaining boundary conditions fix the tangential components of either the velocity vector

$\boldsymbol{u}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {\boldsymbol{z}}$

vanishes, and remaining boundary conditions fix the tangential components of either the velocity vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

or the stresses

$\boldsymbol{u}$

or the stresses

![]() $\partial _z\boldsymbol{u}$

. In the fixed-velocity case, the boundary conditions are

$\partial _z\boldsymbol{u}$

. In the fixed-velocity case, the boundary conditions are

and in the fixed-stress case, they are

where

![]() $C$

can be any constant (including zero) and can be different at each boundary.

$C$

can be any constant (including zero) and can be different at each boundary.

The configurations described previously admit a laminar solution

![]() $U(z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

to the governing equations (2.1). Most derivations here are done in terms of the deviation

$U(z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

to the governing equations (2.1). Most derivations here are done in terms of the deviation

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

from the laminar state, which is defined by

$\boldsymbol{v}$

from the laminar state, which is defined by

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}(\boldsymbol{x},t)=U(z)\boldsymbol{\hat {x}}+\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

. Denoting the components of the deviation by

$\boldsymbol{u}(\boldsymbol{x},t)=U(z)\boldsymbol{\hat {x}}+\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

. Denoting the components of the deviation by

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}=(v_1,v_2,v_3)$

, the evolution of

$\boldsymbol{v}=(v_1,v_2,v_3)$

, the evolution of

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

implied by (2.1) is

$\boldsymbol{v}$

implied by (2.1) is

where primes denote ordinary derivatives in

![]() $z$

. Boundary conditions on the deviation

$z$

. Boundary conditions on the deviation

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

are homogeneous. At a boundary where

$\boldsymbol{v}$

are homogeneous. At a boundary where

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

satisfies the fixed-velocity condition (2.2), the

$\boldsymbol{u}$

satisfies the fixed-velocity condition (2.2), the

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

condition is no-slip,

$\boldsymbol{v}$

condition is no-slip,

At a boundary where

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

satisfies the fixed-stress condition (2.3), the

$\boldsymbol{u}$

satisfies the fixed-stress condition (2.3), the

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

condition is stress-free,

$\boldsymbol{v}$

condition is stress-free,

Formulations of the background method in the present section assume that (2.5) or (2.6) holds at each boundary, but the two boundaries need not be the same. Results in § 3 require the same condition at both boundaries.

2.1. Background method formulation in terms of auxiliary functionals

For shear flows governed by (2.1), the quantity that has most often been bounded using the background method is the mean dissipation. We let angle brackets denote an average over the spatial domain

![]() $\varOmega$

and let an overbar denote an infinite-time average, so the dimensionless dissipation averaged over the volume and infinite time is

$\varOmega$

and let an overbar denote an infinite-time average, so the dimensionless dissipation averaged over the volume and infinite time is

where

![]() $\varGamma _x\varGamma _y$

is the volume of the dimensionless domain and, if the infinite-time limit is not well defined, one can take the limit supremum. The dimensionless quantity (2.7) is the same one used in previous works such as that of Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003). For physical interpretation in § 4, we examine this dissipation’s ratio to its laminar value since this ratio does not depend on the chosen non-dimensionalisation. The average dissipation is related a priori to the average rate of energy input by body and boundary forces, as explained for the examples of Wallefe flow and Couette flow in § 4.

$\varGamma _x\varGamma _y$

is the volume of the dimensionless domain and, if the infinite-time limit is not well defined, one can take the limit supremum. The dimensionless quantity (2.7) is the same one used in previous works such as that of Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003). For physical interpretation in § 4, we examine this dissipation’s ratio to its laminar value since this ratio does not depend on the chosen non-dimensionalisation. The average dissipation is related a priori to the average rate of energy input by body and boundary forces, as explained for the examples of Wallefe flow and Couette flow in § 4.

Whether one seeks upper or lower bounds depends on the model. Often, it is easy to show that the dissipation among all flows is bounded below or above by the laminar dissipation, in which case, it remains only to find upper or lower bounds, respectively. For concreteness, our exposition in this section considers upper bounds on mean dissipation. Section 2.4 summarises what changes in the case of lower bounds. The background method can bound averages of other linear or quadratic integrals also, such as kinetic energy, by straightforward modifications to the formulations given here.

Our goal is to derive bounds on (2.7) that apply to all solutions of the governing equations (2.1) subject to boundary conditions, regardless of the initial conditions. We give the derivation in terms of a so-called auxiliary functional

![]() $V$

. Such functionals have not been explicitly used in the background method literature until recently, but they are implicit in all such arguments, as explained by Chernyshenko (Reference Chernyshenko2022) and Fantuzzi et al. (Reference Fantuzzi, Arslan and Wynn2022). An auxiliary functional

$V$

. Such functionals have not been explicitly used in the background method literature until recently, but they are implicit in all such arguments, as explained by Chernyshenko (Reference Chernyshenko2022) and Fantuzzi et al. (Reference Fantuzzi, Arslan and Wynn2022). An auxiliary functional

![]() $V[\boldsymbol{w}]$

maps a divergence-free, time-independent vector field

$V[\boldsymbol{w}]$

maps a divergence-free, time-independent vector field

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x})$

to a real number. All past applications of the background method to planar shear flows are equivalent to choosing

$\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x})$

to a real number. All past applications of the background method to planar shear flows are equivalent to choosing

![]() $V[\boldsymbol{w}]$

that is a quadratic spatial integral of the form

$V[\boldsymbol{w}]$

that is a quadratic spatial integral of the form

where the functional is defined by choosing the ‘balance parameter’

![]() $a$

and the ‘background field’

$a$

and the ‘background field’

![]() $\zeta (z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

. The quantity

$\zeta (z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

. The quantity

![]() $({1}/{a})\zeta$

is called the background field in the notation of most prior works (cf. Chernyshenko Reference Chernyshenko2022), but it is useful for what follows to define notation for

$({1}/{a})\zeta$

is called the background field in the notation of most prior works (cf. Chernyshenko Reference Chernyshenko2022), but it is useful for what follows to define notation for

![]() $\zeta$

rather than for

$\zeta$

rather than for

![]() $({1}/{a})\zeta$

because then,

$({1}/{a})\zeta$

because then,

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

appear linearly in

$\zeta$

appear linearly in

![]() $V$

. Generalisations of (2.8) that go beyond quadratic integrals have the potential to give stronger results, as they do for the Kuramoto–Sivashinsky equation (Goluskin & Fantuzzi Reference Goluskin and Fantuzzi2019), but the present work concerns the background method and thus only

$V$

. Generalisations of (2.8) that go beyond quadratic integrals have the potential to give stronger results, as they do for the Kuramoto–Sivashinsky equation (Goluskin & Fantuzzi Reference Goluskin and Fantuzzi2019), but the present work concerns the background method and thus only

![]() $V$

of the form (2.8). There is no advantage to considering a background field of more general form than

$V$

of the form (2.8). There is no advantage to considering a background field of more general form than

![]() $\zeta (z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

, as proved in Appendix A.1 using symmetry arguments. To enable integration by parts later, the background field is admissible only if it is continuous and piecewise smooth, and if it satisfies the same boundary conditions as

$\zeta (z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

, as proved in Appendix A.1 using symmetry arguments. To enable integration by parts later, the background field is admissible only if it is continuous and piecewise smooth, and if it satisfies the same boundary conditions as

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

.

$\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

.

The definition of

![]() $V$

does not involve time, but one obtains a scalar-valued function of time by considering

$V$

does not involve time, but one obtains a scalar-valued function of time by considering

![]() $V[\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)]$

, where

$V[\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)]$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

solves (2.4). For choices of

$\boldsymbol{v}$

solves (2.4). For choices of

![]() $V$

that lead to finite bounds on mean dissipation, it can be shown that

$V$

that lead to finite bounds on mean dissipation, it can be shown that

![]() $V[\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)]$

remains bounded as

$V[\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)]$

remains bounded as

![]() $t\to \infty$

for any admissible initial condition

$t\to \infty$

for any admissible initial condition

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},0)$

(Doering & Constantin Reference Doering and Constantin1994). All such

$\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},0)$

(Doering & Constantin Reference Doering and Constantin1994). All such

![]() $V$

satisfy the identity

$V$

satisfy the identity

so the time-averaged dissipation

![]() $\overline {\langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\rangle }$

that we want to bound is equal to

$\overline {\langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\rangle }$

that we want to bound is equal to

![]() $\overline {\langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\rangle +({\mathrm{d}}/{{\mathrm{d}}t})V}$

. Moreover, one can find an expression equal to

$\overline {\langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\rangle +({\mathrm{d}}/{{\mathrm{d}}t})V}$

. Moreover, one can find an expression equal to

![]() $({\mathrm{d}}/{{\mathrm{d}}t})V[\boldsymbol{v}]$

without explicit time-dependence:

$({\mathrm{d}}/{{\mathrm{d}}t})V[\boldsymbol{v}]$

without explicit time-dependence:

Equation (2.10) is derived by moving the time derivative inside the volume integral, and (2.11) replaces

![]() $\partial _t\boldsymbol{v}$

according to (2.4). Equation (2.12) follows from integration by parts, recalling that we require

$\partial _t\boldsymbol{v}$

according to (2.4). Equation (2.12) follows from integration by parts, recalling that we require

![]() $\zeta (z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

to satisfy the same boundary conditions as

$\zeta (z)\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}$

to satisfy the same boundary conditions as

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

, which may be stress-free or no-slip at each boundary. Finally, we find a useful expression with the same time average as the dissipation:

$\boldsymbol{v}$

, which may be stress-free or no-slip at each boundary. Finally, we find a useful expression with the same time average as the dissipation:

where the functional

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

is defined as

$\mathcal{Q}$

is defined as

for any time-independent, divergence-free vector field

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}=(w_1,w_2,w_3)$

that obeys the same boundary conditions as

$\boldsymbol{w}=(w_1,w_2,w_3)$

that obeys the same boundary conditions as

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

. The equality (2.13) follows from substituting

$\boldsymbol{v}$

. The equality (2.13) follows from substituting

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}=U\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}+\boldsymbol{v}$

, the next equality uses (2.9), and then applying (2.12) gives the expression for

$\boldsymbol{u}=U\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}+\boldsymbol{v}$

, the next equality uses (2.9), and then applying (2.12) gives the expression for

![]() $\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

.

$\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

.

Since the time average

![]() $\overline {\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{v}]}$

is bounded above by the maximum of

$\overline {\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{v}]}$

is bounded above by the maximum of

![]() $\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

over all possible

$\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

over all possible

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

, (2.15) implies

$\boldsymbol{w}$

, (2.15) implies

for any

![]() $a$

and any admissible

$a$

and any admissible

![]() $\zeta$

, where

$\zeta$

, where

![]() $\mathcal{H}_{3D}$

is the class of 3-D divergence-free vector fields

$\mathcal{H}_{3D}$

is the class of 3-D divergence-free vector fields

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x})$

that satisfy the same boundary conditions (2.5) or (2.6) as

$\boldsymbol{w}(\boldsymbol{x})$

that satisfy the same boundary conditions (2.5) or (2.6) as

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

does. The right-hand maximum in (2.17) can be finite or infinite, depending on

$\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

does. The right-hand maximum in (2.17) can be finite or infinite, depending on

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

. When the maximum is finite, it can be computed numerically or bounded above analytically. One naturally wants to choose

$\zeta$

. When the maximum is finite, it can be computed numerically or bounded above analytically. One naturally wants to choose

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

to make the resulting upper bound as small as possible. At each fixed

$\zeta$

to make the resulting upper bound as small as possible. At each fixed

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

, the upper bound on dissipation that is optimal within the framework of the background method is the solution to a min–max problem,

$ \textit{Re}$

, the upper bound on dissipation that is optimal within the framework of the background method is the solution to a min–max problem,

where the function class over which

![]() $\zeta$

is minimised is such that

$\zeta$

is minimised is such that

![]() $\zeta \hat {\boldsymbol{x}}\in \mathcal{H}_{3\text{D}}$

. In §§ 2.2 and 2.3, we give three more formulations that are equivalent to (2.18) and are useful for different purposes.

$\zeta \hat {\boldsymbol{x}}\in \mathcal{H}_{3\text{D}}$

. In §§ 2.2 and 2.3, we give three more formulations that are equivalent to (2.18) and are useful for different purposes.

The optimal background method formulation (2.18) is a more precise version of (1.1) for the case of planar shear flows. Since the inner maximisation gives an infinite value for some

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

, strictly speaking, the minimum and maximum should be called an infimum and supremum, respectively, but we use the notation

$\zeta$

, strictly speaking, the minimum and maximum should be called an infimum and supremum, respectively, but we use the notation

![]() $\min$

and

$\min$

and

![]() $\max$

throughout. Provided these values are finite, we assume that all maxima and minima are attained, meaning that there exist

$\max$

throughout. Provided these values are finite, we assume that all maxima and minima are attained, meaning that there exist

![]() $a$

,

$a$

,

![]() $\zeta$

and

$\zeta$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

for which

$\boldsymbol{w}$

for which

![]() $\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

is equal to its min–max in (2.18). Such attainment relies on optimising

$\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

is equal to its min–max in (2.18). Such attainment relies on optimising

![]() $\zeta$

and

$\zeta$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

over sufficiently large function spaces (Evans Reference Evans2022), but the exact choice of these spaces is beyond our scope.

$\boldsymbol{w}$

over sufficiently large function spaces (Evans Reference Evans2022), but the exact choice of these spaces is beyond our scope.

2.2.

Mean and mean-free decomposition of

$\mathcal{Q}$

$\mathcal{Q}$

The maximisation over

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

in (2.17) can be decoupled into maximisations over the planar mean of

$\boldsymbol{w}$

in (2.17) can be decoupled into maximisations over the planar mean of

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

and over its remaining mean-free part. This decoupling leads to a variational problem familiar from energy stability analysis, eventually allowing us to apply the theorem of Busse (Reference Busse1972). It also reveals that finite values of the upper bound (2.17) depend on

$\boldsymbol{w}$

and over its remaining mean-free part. This decoupling leads to a variational problem familiar from energy stability analysis, eventually allowing us to apply the theorem of Busse (Reference Busse1972). It also reveals that finite values of the upper bound (2.17) depend on

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

, but not on

$\zeta$

, but not on

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

, even though the functional

$ \textit{Re}$

, even though the functional

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

being maximised depends also on

$\mathcal{Q}$

being maximised depends also on

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

. For fixed

$ \textit{Re}$

. For fixed

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

, the maximum will assume a constant value at sufficiently small

$\zeta$

, the maximum will assume a constant value at sufficiently small

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

, and for larger

$ \textit{Re}$

, and for larger

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

, the right-hand side of (2.17) will be infinite.

$ \textit{Re}$

, the right-hand side of (2.17) will be infinite.

We decompose the divergence-free vector field

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

as

$\boldsymbol{w}$

as

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}$

is the mean of

$\boldsymbol{F}$

is the mean of

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

over the periodic

$\boldsymbol{w}$

over the periodic

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

directions, and

$y$

directions, and

![]() $\dot {\boldsymbol{w}}$

is the remaining mean-free part. We denote the components of the mean as

$\dot {\boldsymbol{w}}$

is the remaining mean-free part. We denote the components of the mean as

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}=(F_1,F_2,0)$

, where the zero wall-normal component follows from impenetrability of the walls and incompressibility. With

$\boldsymbol{F}=(F_1,F_2,0)$

, where the zero wall-normal component follows from impenetrability of the walls and incompressibility. With

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

so decomposed, the

$\boldsymbol{w}$

so decomposed, the

![]() $\mathcal{Q}$

functional defined by (2.16) decouples into functionals of

$\mathcal{Q}$

functional defined by (2.16) decouples into functionals of

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}$

and of

$\boldsymbol{F}$

and of

![]() $\dot {\boldsymbol{w}}$

,

$\dot {\boldsymbol{w}}$

,

where

To find the maximum of

![]() $\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

, we can separately maximise

$\mathcal{Q}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

, we can separately maximise

![]() $\mathcal{F}[\boldsymbol{F}]$

and

$\mathcal{F}[\boldsymbol{F}]$

and

![]() $\mathcal{E}[\dot {\boldsymbol{w}}]$

.

$\mathcal{E}[\dot {\boldsymbol{w}}]$

.

The functional

![]() $\mathcal{F}[\boldsymbol{F}]$

has a finite maximum only if

$\mathcal{F}[\boldsymbol{F}]$

has a finite maximum only if

![]() $a\gt 1$

, so we assume this hereafter. Since the

$a\gt 1$

, so we assume this hereafter. Since the

![]() $F_2$

term in (2.21) is non-positive and independent of other terms, the maximiser

$F_2$

term in (2.21) is non-positive and independent of other terms, the maximiser

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}^*$

that attains the maximum of

$\boldsymbol{F}^*$

that attains the maximum of

![]() $\mathcal{F}$

must have

$\mathcal{F}$

must have

![]() $F_{2}^{\prime*}=0$

. With no-slip boundaries, this implies

$F_{2}^{\prime*}=0$

. With no-slip boundaries, this implies

![]() $F^*_2=0$

and with stress-free boundaries, we let

$F^*_2=0$

and with stress-free boundaries, we let

![]() $F^*_2=0$

to fix the reference frame. The Euler–Lagrange equation for

$F^*_2=0$

to fix the reference frame. The Euler–Lagrange equation for

![]() $F_1$

then gives

$F_1$

then gives

![]() $F_1^*=(2U+\zeta)/[2(a-1)]$

. Thus,

$F_1^*=(2U+\zeta)/[2(a-1)]$

. Thus,

where

![]() $\dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}$

is the mean-free subspace of

$\dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}$

is the mean-free subspace of

![]() $\mathcal{H}_{3\text{D}}$

. Henceforth, we do not write

$\mathcal{H}_{3\text{D}}$

. Henceforth, we do not write

![]() $\dot {\boldsymbol{w}}$

; fields denoted by

$\dot {\boldsymbol{w}}$

; fields denoted by

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

may be mean-free or not, depending on their function spaces.

$\boldsymbol{w}$

may be mean-free or not, depending on their function spaces.

The maximum in (2.23) is finite – thus giving an upper bound on dissipation – if and only if the

![]() $\mathcal{E}$

functional is non-positive for all mean-free fields. If

$\mathcal{E}$

functional is non-positive for all mean-free fields. If

![]() $\mathcal{E}$

is non-positive, its maximum of zero is attained by

$\mathcal{E}$

is non-positive, its maximum of zero is attained by

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}=\boldsymbol 0$

. Otherwise, its maximum is infinity since all terms in

$\boldsymbol{w}=\boldsymbol 0$

. Otherwise, its maximum is infinity since all terms in

![]() $\mathcal{E}$

are quadratic; any

$\mathcal{E}$

are quadratic; any

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

for which

$\boldsymbol{w}$

for which

![]() $\mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]\gt 0$

can be scaled to make

$\mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]\gt 0$

can be scaled to make

![]() $\mathcal{E}$

arbitrarily large. With this observation, minimising (2.23) over

$\mathcal{E}$

arbitrarily large. With this observation, minimising (2.23) over

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

gives our second formulation of the optimal background method bound,

$\zeta$

gives our second formulation of the optimal background method bound,

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\leqslant \min _{\substack {a\gt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]\leqslant 0 \quad \forall \,\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\leqslant \min _{\substack {a\gt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]\leqslant 0 \quad \forall \,\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}. \end{align}

The constrained minimisation in the second formulation (2.24) is equivalent to the unconstrained min–max in the first formulation (2.18). The

![]() $\mathcal{E}\leqslant 0$

constraint in (2.24) is called the spectral constraint because, as shown in the next subsection, it can be formulated in terms of the spectrum of a linear eigenproblem.

$\mathcal{E}\leqslant 0$

constraint in (2.24) is called the spectral constraint because, as shown in the next subsection, it can be formulated in terms of the spectrum of a linear eigenproblem.

2.3. Spectral constraint

We now derive two more ways to formulate the spectral constraint in (2.24), thus giving a third and fourth formulation of the optimal background method problem. Both reformulations are familiar from energy stability analysis of shear flows. To see the connection to energy stability, note that non-positivity of the

![]() $\mathcal{E}$

functional defined by (2.22) is equivalent to

$\mathcal{E}$

functional defined by (2.22) is equivalent to

where we have divided by the positive quantity

![]() $a-1$

and let

$a-1$

and let

The condition (2.25) is precisely the energy stability condition for a laminar flow whose derivative is

![]() $h(z)$

rather than

$h(z)$

rather than

![]() $U^{\prime}(z)$

. For such a flow, the time derivative of the perturbation energy

$U^{\prime}(z)$

. For such a flow, the time derivative of the perturbation energy

![]() $\langle |\boldsymbol{v}|^2\rangle$

is non-positive for all admissible

$\langle |\boldsymbol{v}|^2\rangle$

is non-positive for all admissible

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

if and only if (2.25) holds. In other words, the spectral constraint of the background method for a flow with laminar shear

$\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

if and only if (2.25) holds. In other words, the spectral constraint of the background method for a flow with laminar shear

![]() $U^{\prime}$

is exactly the energy stability constraint for a flow with laminar shear

$U^{\prime}$

is exactly the energy stability constraint for a flow with laminar shear

![]() $h$

. Just as laminar flows are energy stable only below a certain

$h$

. Just as laminar flows are energy stable only below a certain

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

value that depends on

$ \textit{Re}$

value that depends on

![]() $U$

, the spectral constraint is satisfied only below a certain

$U$

, the spectral constraint is satisfied only below a certain

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

that depends on

$ \textit{Re}$

that depends on

![]() $U$

,

$U$

,

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

.

$\zeta$

.

One way to reformulate the spectral constraint is to rearrange (2.25) as an inequality for

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

. Note that the first term of (2.25) is negative definite, while the second is sign-indefinite. In fact, for any field

$ \textit{Re}$

. Note that the first term of (2.25) is negative definite, while the second is sign-indefinite. In fact, for any field

![]() $[w_1,w_2,w_3](x,y,z)$

giving certain values for first and second terms in (2.25), the field

$[w_1,w_2,w_3](x,y,z)$

giving certain values for first and second terms in (2.25), the field

![]() $[-w_1,w_2,w_3](-x,y,z)$

gives the same first term but negates the second. Therefore, taking the absolute value of the second term in (2.25) gives an equivalent condition,

$[-w_1,w_2,w_3](-x,y,z)$

gives the same first term but negates the second. Therefore, taking the absolute value of the second term in (2.25) gives an equivalent condition,

In turn, this is equivalent to

where

Expressing the spectral constraint in (2.24) using

![]() $\mathcal{R}$

gives our third formulation of the optimal background method,

$\mathcal{R}$

gives our third formulation of the optimal background method,

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\leqslant \min _{\substack {a\gt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \textit{Re}\leqslant \min _{\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}}\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]. \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\leqslant \min _{\substack {a\gt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \textit{Re}\leqslant \min _{\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}}\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]. \end{align}

For fixed

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

, the background method gives the right-hand integral in (2.24) as an upper bound if

$\zeta$

, the background method gives the right-hand integral in (2.24) as an upper bound if

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

satisfies (2.28) and it gives no finite bound at larger

$ \textit{Re}$

satisfies (2.28) and it gives no finite bound at larger

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

. The energy stability criterion is commonly expressed as (2.28) for a flow with laminar shear profile

$ \textit{Re}$

. The energy stability criterion is commonly expressed as (2.28) for a flow with laminar shear profile

![]() $h$

. This is the formulation of energy stability used throughout the analysis of Busse (Reference Busse1972), which underlies our criterion derived in § 3. We thus express the spectral constraint as (2.28) throughout § 3.

$h$

. This is the formulation of energy stability used throughout the analysis of Busse (Reference Busse1972), which underlies our criterion derived in § 3. We thus express the spectral constraint as (2.28) throughout § 3.

Another reformulation of the spectral constraint is in terms of the spectrum of a linear eigenproblem. Since

![]() $\mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]\leqslant 0$

holds if and only if it holds when

$\mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]\leqslant 0$

holds if and only if it holds when

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

is scaled to satisfy

$\boldsymbol{w}$

is scaled to satisfy

![]() $\langle |\boldsymbol{w}|^2\rangle =1$

, the spectral constraint is equivalent to

$\langle |\boldsymbol{w}|^2\rangle =1$

, the spectral constraint is equivalent to

We have negated

![]() $\mathcal{E}$

to obtain a non-negativity condition for consistency with prior works. The normalisation constraint on

$\mathcal{E}$

to obtain a non-negativity condition for consistency with prior works. The normalisation constraint on

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

has been added so that the left-hand minimum is negative but still finite when the spectral constraint is violated. Then, whether or not the spectral constraint holds, the variational problem (2.31) has mean-free minimisers that satisfy its Euler–Lagrange equations,

$\boldsymbol{w}$

has been added so that the left-hand minimum is negative but still finite when the spectral constraint is violated. Then, whether or not the spectral constraint holds, the variational problem (2.31) has mean-free minimisers that satisfy its Euler–Lagrange equations,

where

![]() $2p(\boldsymbol{x})$

is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing incompressibility and

$2p(\boldsymbol{x})$

is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing incompressibility and

![]() $\lambda$

is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing

$\lambda$

is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing

![]() $\langle |\boldsymbol{w}|^2\rangle =1$

that acts as an eigenvalue in (2.32). The spectral constraint is equivalent to all eigenvalues of (2.32) being non-negative – that is, to this linear eigenproblem having a non-negative spectrum.

$\langle |\boldsymbol{w}|^2\rangle =1$

that acts as an eigenvalue in (2.32). The spectral constraint is equivalent to all eigenvalues of (2.32) being non-negative – that is, to this linear eigenproblem having a non-negative spectrum.

To simplify implementation of the eigenproblem (2.32), one can Fourier transform in the periodic directions. This gives an eigenproblem that is an ordinary differential equation in

![]() $z$

for each fixed wavevector

$z$

for each fixed wavevector

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}=(j,k)$

, where

$\boldsymbol{k}=(j,k)$

, where

![]() $j$

and

$j$

and

![]() $k$

are the streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers, respectively. For each

$k$

are the streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers, respectively. For each

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}$

,

$\boldsymbol{k}$

,

\begin{align} \begin{split} -(a-1)\left (\frac {\mathrm{d}^2}{{\mathrm{d}}z^2}-j^2-k^2\right ) \hat {w}_1+\frac 12 \textit{Re} (aU+\zeta )^{\prime} \hat {w}_3+ij\hat {p}&=\lambda \hat {w}_1, \\ -(a-1)\left (\frac {\mathrm{d}^2}{{\mathrm{d}}z^2}-j^2-k^2\right ) \hat {w}_2+ik\hat {p}&=\lambda \hat {w}_2, \\ -(a-1)\left (\frac {\mathrm{d}^2}{{\mathrm{d}}z^2}-j^2-k^2\right ) \hat {w}_3+\frac 12 \textit{Re} (aU+\zeta )^{\prime}\hat w_1+\frac {\mathrm{d} }{{\mathrm{d}}z}\hat {p}&=\lambda \hat {w}_3, \\ ij\hat {w}_1+ik\hat {w}_2+\frac {\mathrm{d}}{{\mathrm{d}}z}\hat {w}_3&=0, \end{split} \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{split} -(a-1)\left (\frac {\mathrm{d}^2}{{\mathrm{d}}z^2}-j^2-k^2\right ) \hat {w}_1+\frac 12 \textit{Re} (aU+\zeta )^{\prime} \hat {w}_3+ij\hat {p}&=\lambda \hat {w}_1, \\ -(a-1)\left (\frac {\mathrm{d}^2}{{\mathrm{d}}z^2}-j^2-k^2\right ) \hat {w}_2+ik\hat {p}&=\lambda \hat {w}_2, \\ -(a-1)\left (\frac {\mathrm{d}^2}{{\mathrm{d}}z^2}-j^2-k^2\right ) \hat {w}_3+\frac 12 \textit{Re} (aU+\zeta )^{\prime}\hat w_1+\frac {\mathrm{d} }{{\mathrm{d}}z}\hat {p}&=\lambda \hat {w}_3, \\ ij\hat {w}_1+ik\hat {w}_2+\frac {\mathrm{d}}{{\mathrm{d}}z}\hat {w}_3&=0, \end{split} \end{align}

where

![]() $i$

is the imaginary unit, the Fourier transforms

$i$

is the imaginary unit, the Fourier transforms

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{w}}(z)$

and

$\hat {\boldsymbol{w}}(z)$

and

![]() $\hat {p}(z)$

are complex in general, all

$\hat {p}(z)$

are complex in general, all

![]() $\lambda$

are real, and

$\lambda$

are real, and

![]() $({\mathrm{d}}/{{\mathrm{d}}z})$

is the ordinary

$({\mathrm{d}}/{{\mathrm{d}}z})$

is the ordinary

![]() $z$

-derivative operator. The spectral constraint is equivalent to (2.33) having a non-negative spectrum of admissible

$z$

-derivative operator. The spectral constraint is equivalent to (2.33) having a non-negative spectrum of admissible

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}$

. This gives our fourth formulation of the optimal background method,

$\boldsymbol{k}$

. This gives our fourth formulation of the optimal background method,

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\leqslant \min _{\substack {a\gt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \lambda \geqslant 0 \text{ in (2.33)}\quad \forall \,\boldsymbol{k}\in K, \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\leqslant \min _{\substack {a\gt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \lambda \geqslant 0 \text{ in (2.33)}\quad \forall \,\boldsymbol{k}\in K, \end{align}

where

![]() $K$

is the set of admissible wavevectors

$K$

is the set of admissible wavevectors

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}=(j,k)$

. It suffices for

$\boldsymbol{k}=(j,k)$

. It suffices for

![]() $K$

to include only non-negative

$K$

to include only non-negative

![]() $j$

and

$j$

and

![]() $k$

; adding constraints for

$k$

; adding constraints for

![]() $(-j,k)$

,

$(-j,k)$

,

![]() $(j,-k)$

or

$(j,-k)$

or

![]() $(-j,-k)$

would be redundant. The velocity is mean-free in

$(-j,-k)$

would be redundant. The velocity is mean-free in

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

, so

$y$

, so

![]() $(0,0)\notin K$

. For bounds to apply for all possible periods

$(0,0)\notin K$

. For bounds to apply for all possible periods

![]() $\varGamma _x$

and

$\varGamma _x$

and

![]() $\varGamma _y$

, the spectrum of (2.34) must be non-negative for all other non-negative pairs

$\varGamma _y$

, the spectrum of (2.34) must be non-negative for all other non-negative pairs

![]() $(j,k)$

. For bounds to apply to flows with fixed

$(j,k)$

. For bounds to apply to flows with fixed

![]() $\varGamma _x$

and

$\varGamma _x$

and

![]() $\varGamma _y$

, the spectrum of (2.34) must be non-negative only for

$\varGamma _y$

, the spectrum of (2.34) must be non-negative only for

![]() $j$

and

$j$

and

![]() $k$

that are integer multiples of

$k$

that are integer multiples of

![]() $2\pi /\varGamma _x$

and

$2\pi /\varGamma _x$

and

![]() $2\pi /\varGamma _y$

. Enforcing the spectral constraint for only 2.5-D fields amounts to including only

$2\pi /\varGamma _y$

. Enforcing the spectral constraint for only 2.5-D fields amounts to including only

![]() $(0,k)\in K$

; this is what Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003) did when computing optimal bounds for Couette flow.

$(0,k)\in K$

; this is what Plasting & Kerswell (Reference Plasting and Kerswell2003) did when computing optimal bounds for Couette flow.

The main question of our present work – whether bounds computed over 2.5-D and 3-D fields coincide – will have the same answer for all four equivalent formulations of the optimal background method in (2.18), (2.24), (2.30) and (2.34). The same is true for suboptimal bounds found by maximising over

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

at fixed

$\boldsymbol{w}$

at fixed

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

. Our computations in § 4 implement the fourth formulation (2.34) to find the optimal

$\zeta$

. Our computations in § 4 implement the fourth formulation (2.34) to find the optimal

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $\zeta$

under the assumption of 2.5-D optimisers, meaning all wavevectors in

$\zeta$

under the assumption of 2.5-D optimisers, meaning all wavevectors in

![]() $K$

have the form

$K$

have the form

![]() $(0,k)$

. One can confirm a posteriori that these bounds apply to 3-D flows by directly checking that the spectral constraint in (2.34) holds also for

$(0,k)$

. One can confirm a posteriori that these bounds apply to 3-D flows by directly checking that the spectral constraint in (2.34) holds also for

![]() $(j,k)$

with

$(j,k)$

with

![]() $j\neq 0$

. In some cases, however, direct checking of the 3-D spectral constraint can be avoided by using the criterion derived in § 3.

$j\neq 0$

. In some cases, however, direct checking of the 3-D spectral constraint can be avoided by using the criterion derived in § 3.

2.4. Lower bounds

The four formulations of the background method derived in §§ 2.1 to 2.3 require only slight modification to give lower bounds on dissipation rather that upper bounds. In the first formulation (2.18), we simply switch the role of minimisation and maximisation to find

Decomposition of

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

into its mean and mean-free parts as in § 2.2 leads to the lower bound version of the second formulation

$\boldsymbol{w}$

into its mean and mean-free parts as in § 2.2 leads to the lower bound version of the second formulation

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\geqslant \max _{\substack {a\lt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]\geqslant 0 \quad \forall \,\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\geqslant \max _{\substack {a\lt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]\geqslant 0 \quad \forall \,\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}. \end{align}

This differs from its analogue (2.24) for upper bounds only in that

![]() $\mathcal{E}$

must have the opposite sign, and finite bounds require

$\mathcal{E}$

must have the opposite sign, and finite bounds require

![]() $a\lt 1$

rather than

$a\lt 1$

rather than

![]() $a\gt 1$

. Dividing the expression (2.22) for

$a\gt 1$

. Dividing the expression (2.22) for

![]() $\mathcal{E}$

by the positive quantity

$\mathcal{E}$

by the positive quantity

![]() $1-a$

, as opposed to

$1-a$

, as opposed to

![]() $a-1$

in the upper bound case, and giving the second term its worst-case sign as in § 2.3, we find that non-negativity of

$a-1$

in the upper bound case, and giving the second term its worst-case sign as in § 2.3, we find that non-negativity of

![]() $\mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

is equivalent to

$\mathcal{E}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

is equivalent to

where

![]() $h(z)$

is defined by (2.26) as for upper bounds. Rearranging (2.37) as an upper bound on

$h(z)$

is defined by (2.26) as for upper bounds. Rearranging (2.37) as an upper bound on

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

, we find that the spectral constraint is identical in the upper and lower bound cases, so the lower bound version of the third formulation is

$ \textit{Re}$

, we find that the spectral constraint is identical in the upper and lower bound cases, so the lower bound version of the third formulation is

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\geqslant \max _{\substack {a\lt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \textit{Re}\leqslant \min _{\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}}\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]. \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline {\left \langle |\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{u}|^2\right \rangle }\geqslant \max _{\substack {a\lt 1 \\ \zeta (z)}} \,\frac {1}{a-1}\left \langle a{U}^{\prime2}+U^{\prime}\zeta^{\prime}+\frac 14{\zeta}^{\prime2}\right \rangle \quad \text{such that}\quad \textit{Re}\leqslant \min _{\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}}\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]. \end{align}

The fourth formulation is the same as (2.38), except the spectral constraint takes its eigenvalue form as in (2.34). In § 3, theoretical results apply to both upper and lower bounds because the spectral constraint takes the same form in both cases.

3. A criterion for streamwise invariance of optimisers

This section presents our main theoretical result: a criterion for confirming that optima over 2.5-D fields and over 3-D fields coincide in the background method for shear flow models with a certain symmetry. This symmetry is defined in § 3.1, then § 3.2 explains how our criterion follows from a criterion of Busse concerning energy stability eigenproblems. Section 3.3 summarises a computational procedure where optimal bounds are computed over 2.5-D fields, some additional easier computations are carried out and then our criterion is used to verify that the bounds hold for 3-D flows. Section 3.4 describes a different approach, where our criterion is included as a constraint in the original 2.5-D bounding computations.

3.1. Assumed symmetry of the governing equations

Throughout § 3, we assume that the governing model is invariant under

![]() $180^\circ$

rotation about a spanwise axis,

$180^\circ$

rotation about a spanwise axis,

That is, we assume that the left-hand side of (3.1) satisfies the governing equation (2.1) and boundary conditions if and only if the right-hand side satisfies them. This requires that any body forcing

![]() $f(z)$

must be odd about the

$f(z)$

must be odd about the

![]() $z=0$

midplane. It also requires the boundary conditions to be odd, meaning that if

$z=0$

midplane. It also requires the boundary conditions to be odd, meaning that if

![]() $u_1$

values are fixed at

$u_1$

values are fixed at

![]() $z=\pm 1/2$

, then they must be negations of each other and likewise, if

$z=\pm 1/2$

, then they must be negations of each other and likewise, if

![]() $\partial _zu_1$

values are fixed. The flow itself need not be invariant under (3.1).

$\partial _zu_1$

values are fixed. The flow itself need not be invariant under (3.1).

For all shear flow models invariant under (3.1), the laminar flow profile

![]() $U(z)$

is odd about the midplane, and (2.4) and the boundary conditions governing perturbations

$U(z)$

is odd about the midplane, and (2.4) and the boundary conditions governing perturbations

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

are also invariant under (3.1). For shear flows with this symmetry, we always restrict to background profiles

$\boldsymbol{v}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

are also invariant under (3.1). For shear flows with this symmetry, we always restrict to background profiles

![]() $\zeta (z)$

that are odd because this cannot worsen the eventual upper bound, as shown in Appendix A.2.

$\zeta (z)$

that are odd because this cannot worsen the eventual upper bound, as shown in Appendix A.2.

3.2. Busse’s criterion

For our present purpose, we consider the third formulation of the optimal background method bound, where the spectral constraint requires that

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

is no larger than the minimum of

$ \textit{Re}$

is no larger than the minimum of

![]() $\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

. This constraint is identical in the upper and lower bounding formulations of (2.30) and (2.38). If this minimum is the same over 2.5-D and 3-D fields for given

$\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

. This constraint is identical in the upper and lower bounding formulations of (2.30) and (2.38). If this minimum is the same over 2.5-D and 3-D fields for given

![]() $\zeta$

and

$\zeta$

and

![]() $a$

, then in any formulation of the background method, it suffices to consider 2.5-D fields. In particular, we aim to compute the optimal

$a$

, then in any formulation of the background method, it suffices to consider 2.5-D fields. In particular, we aim to compute the optimal

![]() $\zeta$

and

$\zeta$

and

![]() $a$

using 2.5-D fields and then verify that the resulting bounds are valid also for 3-D fields.

$a$

using 2.5-D fields and then verify that the resulting bounds are valid also for 3-D fields.

The minimum of

![]() $\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

in (2.30) is exactly the critical

$\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

in (2.30) is exactly the critical

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

value of energy stability for a flow whose laminar profile is

$ \textit{Re}$

value of energy stability for a flow whose laminar profile is

![]() $(aU+\zeta)/(a-1)$

rather than

$(aU+\zeta)/(a-1)$

rather than

![]() $U$

. This follows from the relationship between the spectral constraint and energy stability that is described in the first paragraph of § 2.3. Thus, our present question about the background method amounts to asking whether the critical

$U$

. This follows from the relationship between the spectral constraint and energy stability that is described in the first paragraph of § 2.3. Thus, our present question about the background method amounts to asking whether the critical

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

of energy stability for the laminar profile

$ \textit{Re}$

of energy stability for the laminar profile

![]() $(aU+\zeta)/(a-1)$

is the minimum of

$(aU+\zeta)/(a-1)$

is the minimum of

![]() $\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

over 2.5-D fields or whether 3-D fields would give a smaller minimum. Busse (Reference Busse1972) derived a criterion for drawing exactly this conclusion about the energy stability problem for models with the symmetry (3.1). That criterion is directly applicable here since we are interested in energy stability of the laminar profile

$\mathcal{R}[\boldsymbol{w}]$

over 2.5-D fields or whether 3-D fields would give a smaller minimum. Busse (Reference Busse1972) derived a criterion for drawing exactly this conclusion about the energy stability problem for models with the symmetry (3.1). That criterion is directly applicable here since we are interested in energy stability of the laminar profile

![]() $(aU+\zeta)/(a-1)$

, which has the required symmetry. In particular, this profile is odd and its derivative

$(aU+\zeta)/(a-1)$

, which has the required symmetry. In particular, this profile is odd and its derivative

![]() $h$

is even, because the symmetry (3.1) ensures that

$h$

is even, because the symmetry (3.1) ensures that

![]() $U$

is odd and lets us restrict to odd

$U$

is odd and lets us restrict to odd

![]() $\zeta$

.

$\zeta$

.

The criterion of Busse is most naturally stated using poloidal–toroidal variables, on which its derivation relies. Any divergence-free and mean-free

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}$

in the present geometry can be represented as

$\boldsymbol{w}\in \dot {\mathcal{H}}_{3\text{D}}$

in the present geometry can be represented as

where

![]() $\varphi (\boldsymbol{x})$

and

$\varphi (\boldsymbol{x})$

and

![]() $\psi (\boldsymbol{x})$

are the poloidal and toroidal potentials, respectively. These potentials are uniquely determined by

$\psi (\boldsymbol{x})$

are the poloidal and toroidal potentials, respectively. These potentials are uniquely determined by

![]() $\boldsymbol{w}$

, up to arbitrary additive constants. See Schmitt & Von Wahl (Reference Schmitt and Von Wahl1992) for a proof that this decomposition is always possible with the present geometry and boundary conditions. In these variables, no-slip conditions (2.5) at both boundaries are

$\boldsymbol{w}$

, up to arbitrary additive constants. See Schmitt & Von Wahl (Reference Schmitt and Von Wahl1992) for a proof that this decomposition is always possible with the present geometry and boundary conditions. In these variables, no-slip conditions (2.5) at both boundaries are

and stress-free conditions (2.6) at both boundaries are

In terms of

![]() $\varphi$

and

$\varphi$

and

![]() $\psi$

, the

$\psi$

, the

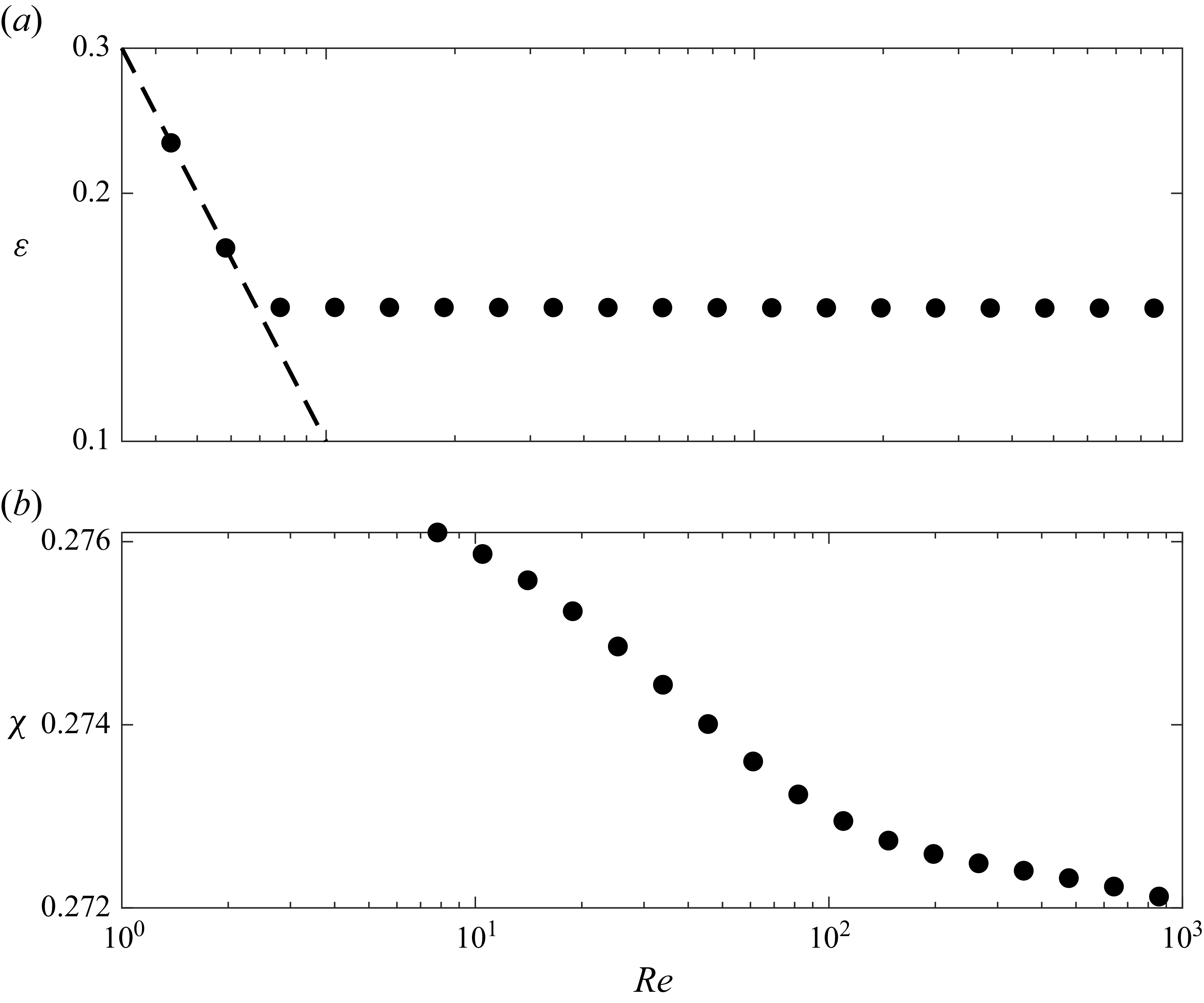

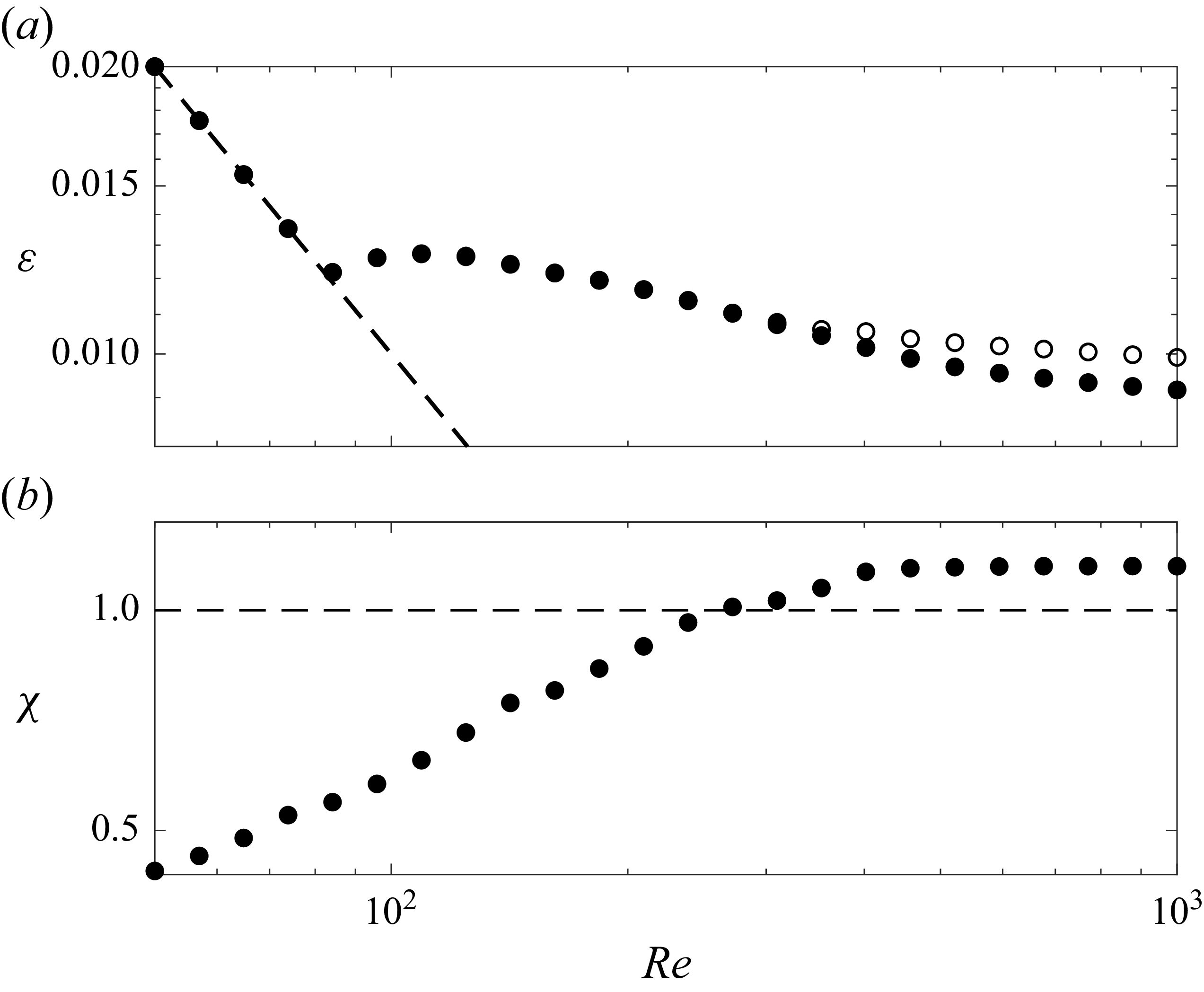

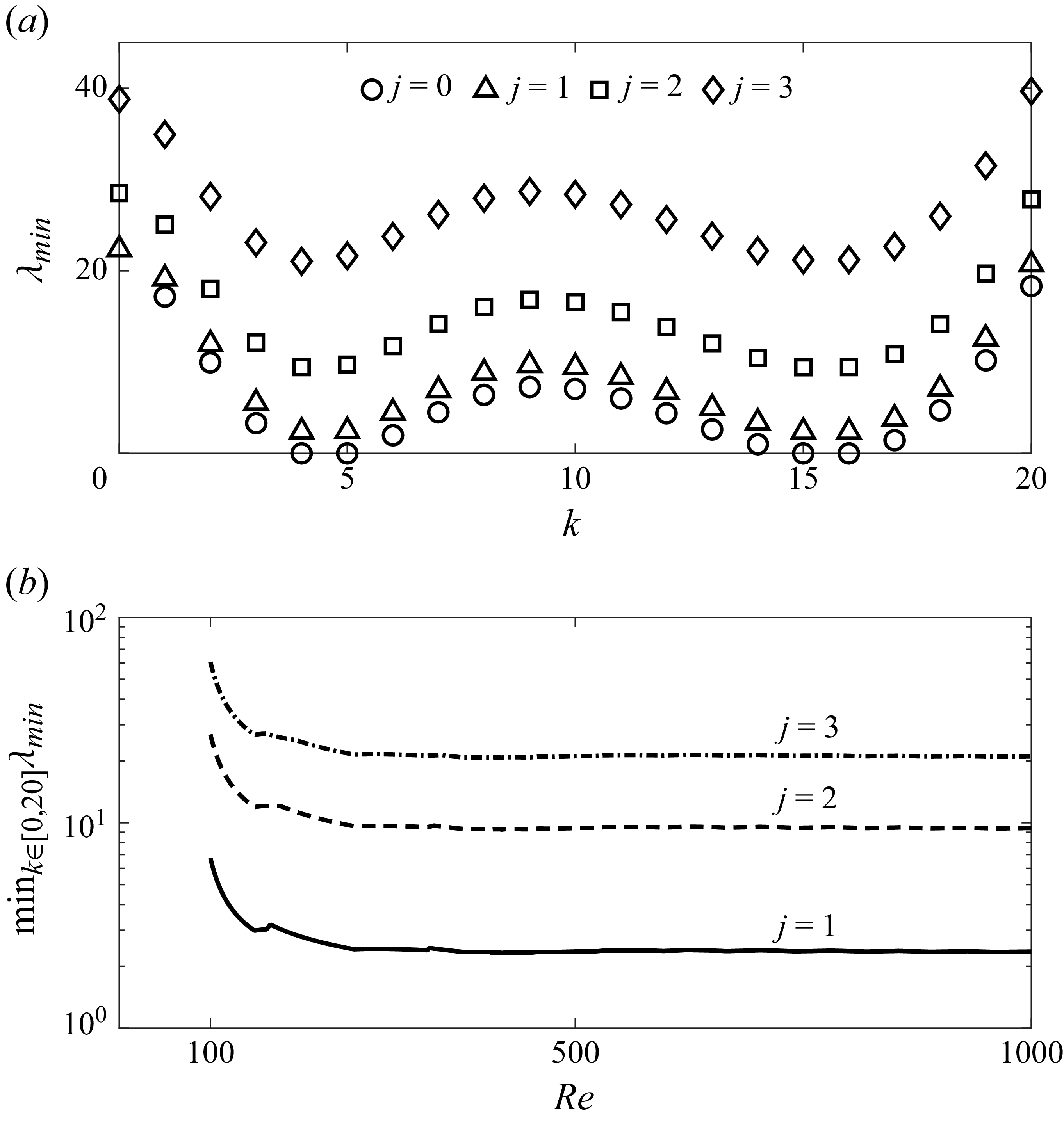

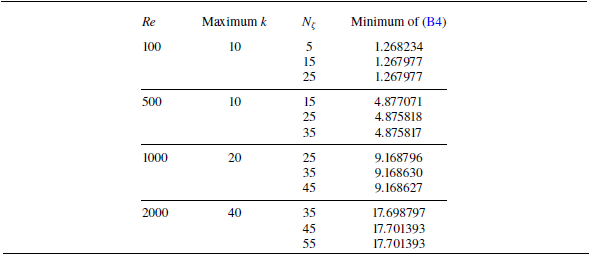

![]() $\mathcal{R}$