Non-technical Summary

Researchers describe a new microfossil species from middle Cambrian rocks of the Georgina Basin in Queensland, Australia. This fossil, named Blastulospongia bouliaensis, shows unique features that confirm that its genus is part of a group of simple marine animals called sponges. It was found alongside fossils of four other ancient microscopic organisms known as radiolarians. One of these, Parechidnina aspinosa, was studied using advanced three-dimensional imaging, revealing how its tiny skeleton was built. These findings help scientists better understand the early evolution of these marine creatures and provide useful markers for dating rocks from this time period, approximately 500 million years ago.

Introduction

Middle Cambrian limestones of the Inca Formation, Beetle Creek Formation, and Devoncourt Limestone within the Georgina Basin in far northwestern Queensland contain the earliest known specular radiolarians (Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999). The exceptional preservation of these forms provides a unique opportunity for in-depth micro-computed tomographic (MCT) analysis, aimed at resolving enduring taxonomic questions surrounding these ancestral radiolarians. Given the known presence of well-preserved Guzhangian Blastulospongia spp. in the nearby Mungerebar Limestone (Bengtson, Reference Bengston1986), along with reported but undescribed specimens of Blastulospongia Pickett and Jell, Reference Pickett and Jell1983 in the Devoncourt Limestone (Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999), this study presents an opportunity to critically assess the taxonomic assignment of this enigmatic form for which radiolarian affinity has previously been considered (Bengtson, Reference Bengston1986; White, Reference White1986). Samples from outcrops of the Devoncourt Limestone along Rogers Ridge in the Burke River Structural Belt at the southeastern edge of the Georgina Basin were examined to collect new material and investigate early radiolarian evolution. Blastulospongia was first recovered from the middle Cambrian First Discovery Limestone, 13 km south of the old ‘Gnalta’ homestead in far western New South Wales, Australia. The authors visited and recollected this locality in 2019, however, no new material of sufficient quality for detailed examination was recovered.

Material and methods

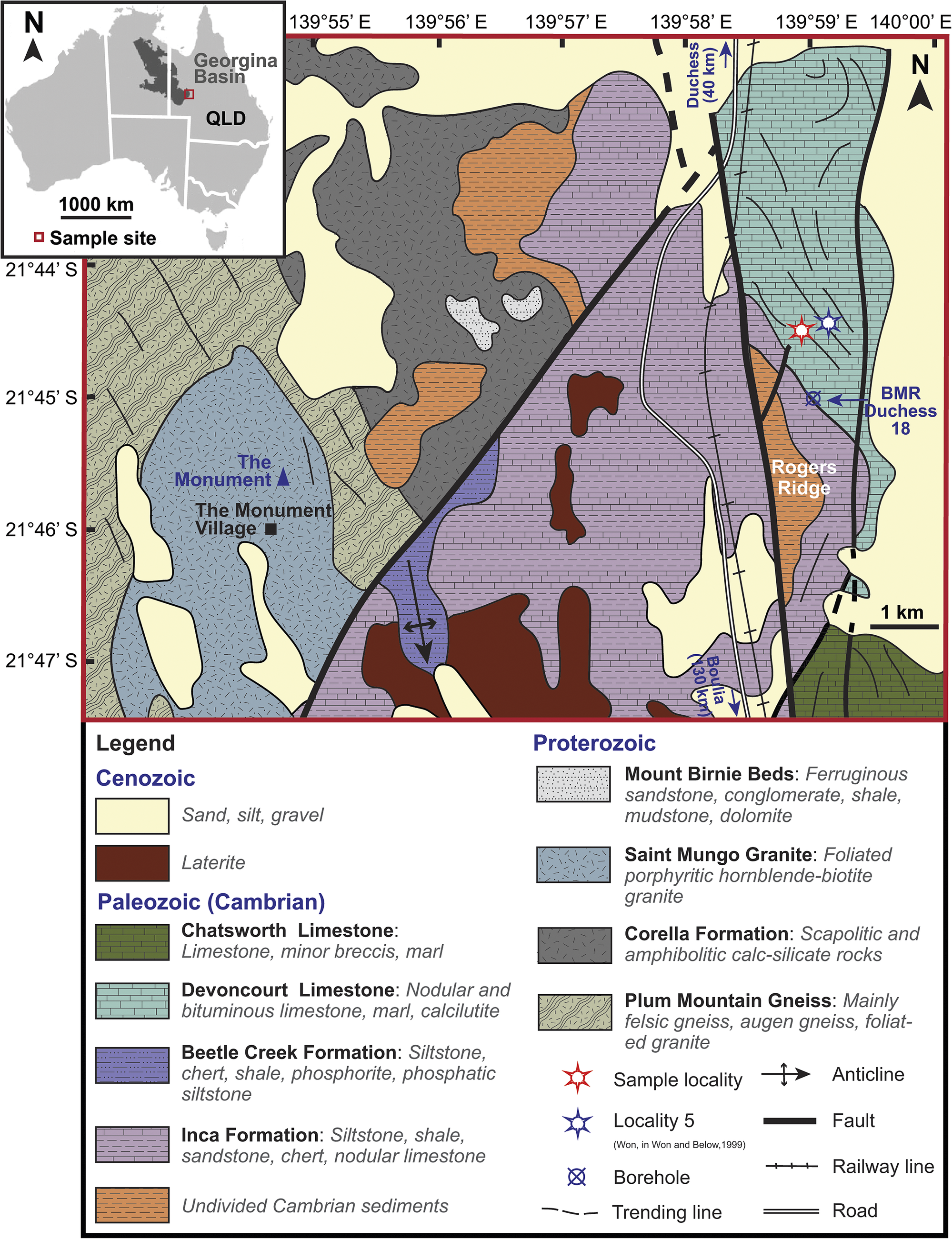

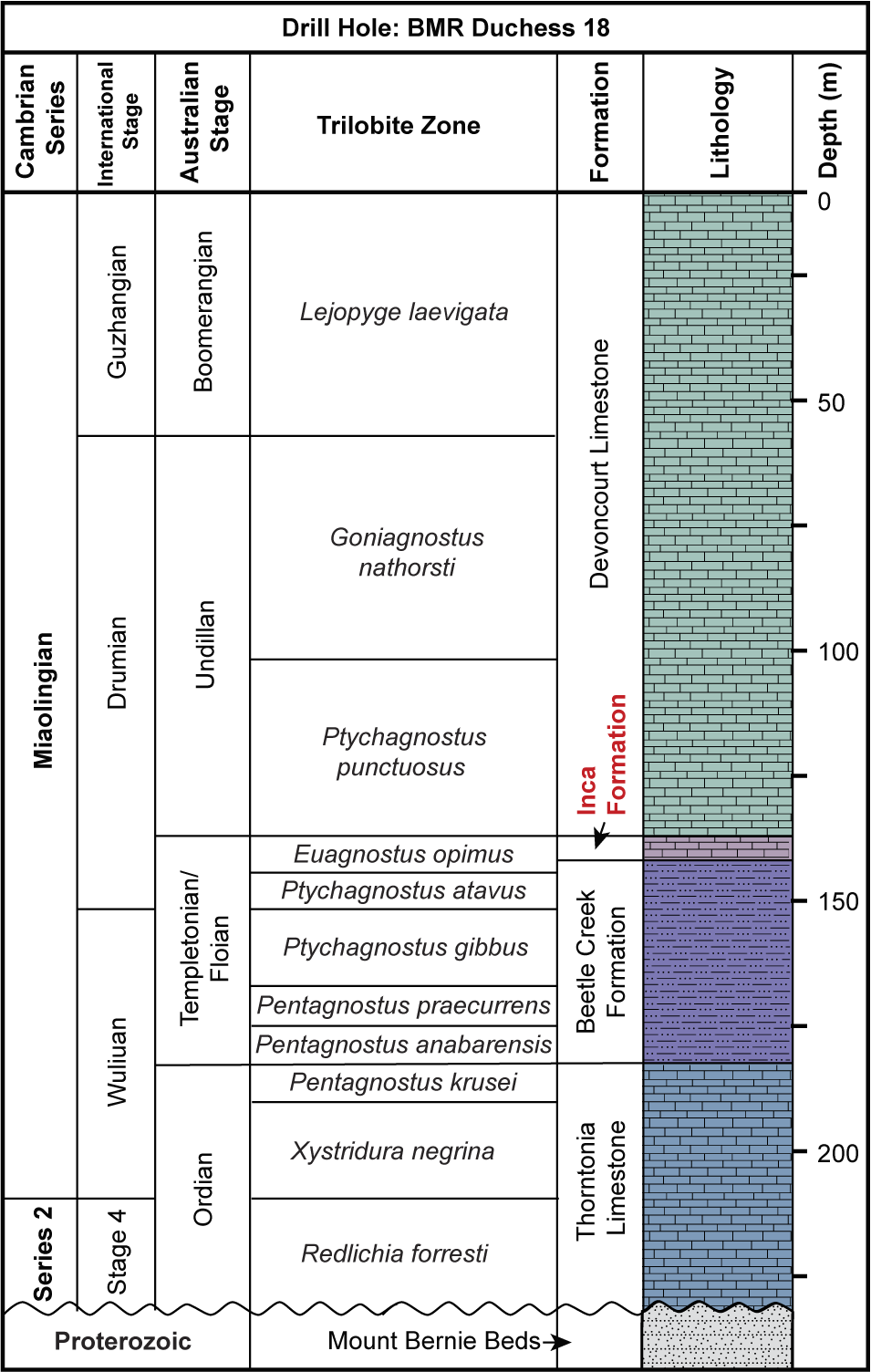

Rogers Ridge is located on the southeastern fringe of the Georgina Basin, ~130 km north of Boulia. Numerous limestone samples were collected from a 300 m section across the Devoncourt Limestone, along a gently sloping hill (Fig. 1). This site is proximal to Locality 5 (139°59’10.6”E, 21°44’2”S) referred to in the study of Won and Below (Reference Won and Below1999), from which eight species of radiolarians and Blastulospongia sp. indet. were identified. The samples used in their research were part of a 1986 collection conducted as part of a collaboration between the Australian Bureau of Mineral Resources (BMR), Canberra, and the University of Bonn, Germany, for the BMR Phosphate Research Project (Southgate et al., Reference Southgate, Laurie, Shergold and Armstrong1988; Walossek et al., Reference Walossek, Hinz-Schallreuter, Shergold and Müler1993). Extensive research on Cambrian trilobites has provided constraints on local stratigraphy (Whitehouse, Reference Whitehouse1936, Reference Whitehouse1939; Öpik, Reference Öpik1956, Reference Öpik1961, Reference Öpik1967; Shergold, Reference Shergold and de Keyser1968; Southgate et al., Reference Southgate, Laurie, Shergold and Armstrong1988). At Rogers Ridge, the Devoncourt Limestone conformably and gradationally overlies the Inca Formation and has a thickness of ~30 m, as seen in BMR Duchess 18 drill core 68 results (Fig. 2; Southgate et al., Reference Southgate, Laurie, Shergold and Armstrong1988). The fauna from the Devoncourt Limestone is dominated by agnostids of the Ptychagnostus punctuosus group (Southgate et al., Reference Southgate, Laurie, Shergold and Armstrong1988) that suggest Undillan to Boomerangian stages (Ptychagnostus punctuosus to Lejopyge laevigata biozones), correlating to the global upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian stages, Miaolingian Series (Öpik, Reference Öpik1961; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Druce, Radke and Draper1976, Reference Shergold, Jago, Cooper, Laurie, Shergold and Palmer1985; Southgate et al., Reference Southgate, Laurie, Shergold and Armstrong1988; Geyer, Reference Geyer2019; Jell, Reference Jell2021).

Figure 1. Geological map of the Devoncourt Limestone and sample site at the Rogers Ridge locality in the Georgina Basin, northern Queensland, Australia. Insert map at top left shows the extent of the Georgina Basin in relation to Australia, with red box indicating the Rogers Ridge locality where the study samples were collected (modified from Blake et al., Reference Blake, Bultitude, Donchak, Wyborn and Hone1984).

Figure 2. Lithological log at the BMR Drill Hole Duchess 18 in the vicinity of the sample site of this study, illustrating the stratigraphic sequence at the Rogers Ridge locality, the thickness of the Devoncourt Limestone, and the ages of the middle Cambrian limestone sequences, constrained by trilobite biostratigraphy (modified from Southgate et al., Reference Southgate, Laurie, Shergold and Armstrong1988).

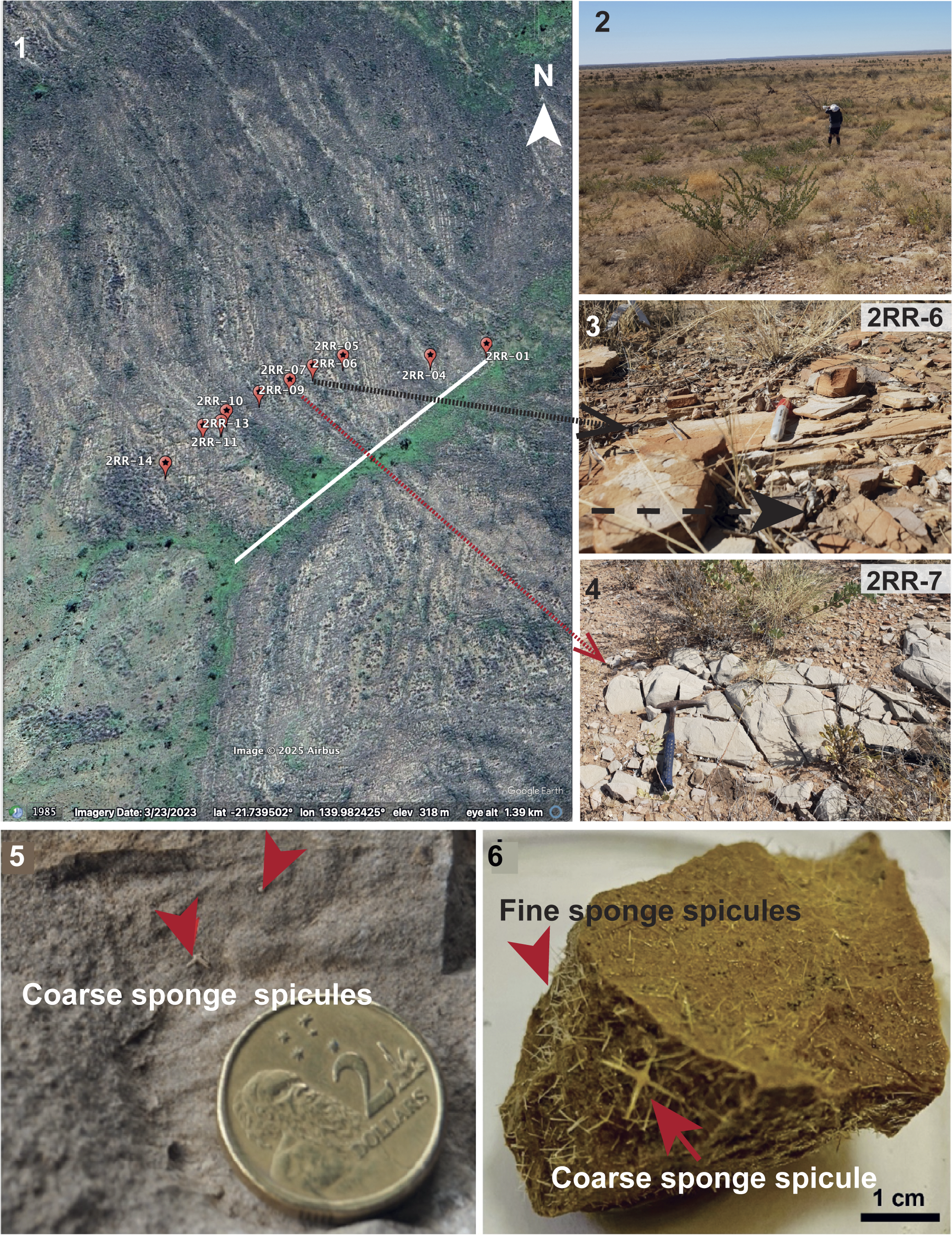

Rodgers Ridge is a relatively prominent feature in an area of generally subdued relief. It lies just over 2 km east of the Duchess to Cloncurry Road and the parallel railway line that leads south to the Phosphate Hill mine (Fig. 1). At the studied locality, finely laminated silty limestone beds alternate with massive limestones (Fig. 3). striking NNW-SSE with a gentle northeastern dip. Fourteen samples were collected: three limestone concretions from the base of the slope, 10 limestone samples at ~25 m intervals across the slope, specifically targeting locations where sponge spicules were exposed on weathered rock surfaces, and a further large limestone concretion fragment (sample 2RR-14) from the top of the hill. The stratigraphically lowest sample 2RR-14 yielded well-preserved radiolarians and a new species of Blastulospongia.

Figure 3. Google Earth image of the sampled section and field photos at the Rogers Ridge locality. (1) Sampled section of Devoncourt Limestone over a gently sloping hill where beds strike NW-SE and dip gently to the north. GPS positions of each sample were recorded during sample collection. (2) Field photo taken from the hilltop showing the nature of the gentle hillslopes and type of vegetation present. (3) Field photo of thinly laminated limestone beds from site of sample 2RR-6 (red-capped marker for scale). (4) Field photo of massive limestone bed at site of sample 2RR-7 (geological hammer for scale). (5, 6) Photos of a typical limestone sample from which radiolarians were recovered before and after acetic-acid digestion: (5) predigestion image showing a naturally weathered surface with visible sponge spicules (coin diameter 20.50 mm); (6) postacid etching, in which an abundance of fine sponge spicules becomes apparent, serving as a promising indicator for successful radiolarian recovery. Scale bars = 275 m (1).

MCT analysis of radiolarian specimens

The methodology for extracting radiolarians using acetic acid, scanning electron microscopic (SEM) imaging, MCT scanning with an Xradia Versa 500 scanner, and digital skeletal analysis using Avizo® software, follows procedures outlined by Sheng et al. (Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020). The specimen was scanned for 4 h with the current of the X-ray source set at 77 μA and a beam voltage of 50 kV. A stack of 970 images with 0.7 μm voxel size was reconstructed. The most labor-intensive aspect of this process is the acid digestion of substantial quantities of limestone, which entails meticulous washing, sieving, and picking, which can take several months before successful extraction of radiolarians. This presents a unique challenge when studying middle Cambrian radiolarians in limestones, because they are less abundant compared with those in younger strata. Unlike chert samples in the field, in which radiolarian ghosts can be identified on wetted surfaces of samples using a hand lens, these Cambrian limestone samples demand a different approach. To locate potential radiolarian-bearing samples, fine-grained limestone with evidence of sponge spicules on weathered surfaces was the preferred lithology. Unfortunately, the fossil yield following this approach remains low, leading to collection of larger quantities of limestones and a time-consuming fossil recovery process.

Previous experience with recovering radiolarians from the Inca Formation (Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020) indicated a positive correlation between the abundance of fine sponge spicules and the presence of radiolarians. To efficiently identify productive limestone samples from > 100 kg of materials, all samples in this study were initially immersed in 20% acetic acid for three weeks. This accelerated surface etching aided identification of fragments with layers of densely packed fine sponge spicules (Fig. 3.6). Promising samples were then subjected to a milder treatment with 5% acetic acid, a step crucial for preserving the delicate skeletal details while recovering radiolarians.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Specimens examined during this study are deposited in the Micropaleontology Collection of the School of the Environment, The University of Queensland, Australia (SEES). SEES/2RR-14_BBO01 refers to the sample number, with the three characters and two digits after the back slash being the section and sample identification number. The last five characters correspond to the specimen identification number. Other repositories mentioned include the paleontological collections of the National Museum of Victoria (NMV), Melbourne, Australia; the University of New England, New South Wales, Australia (UNEF); the National Type Collection of lnvertebrate and Plant Fossils, Geological Survey of Canada (GSC); Pusan National University, Busan, South Korea (PNU); and the National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., USA (USNM).

Results

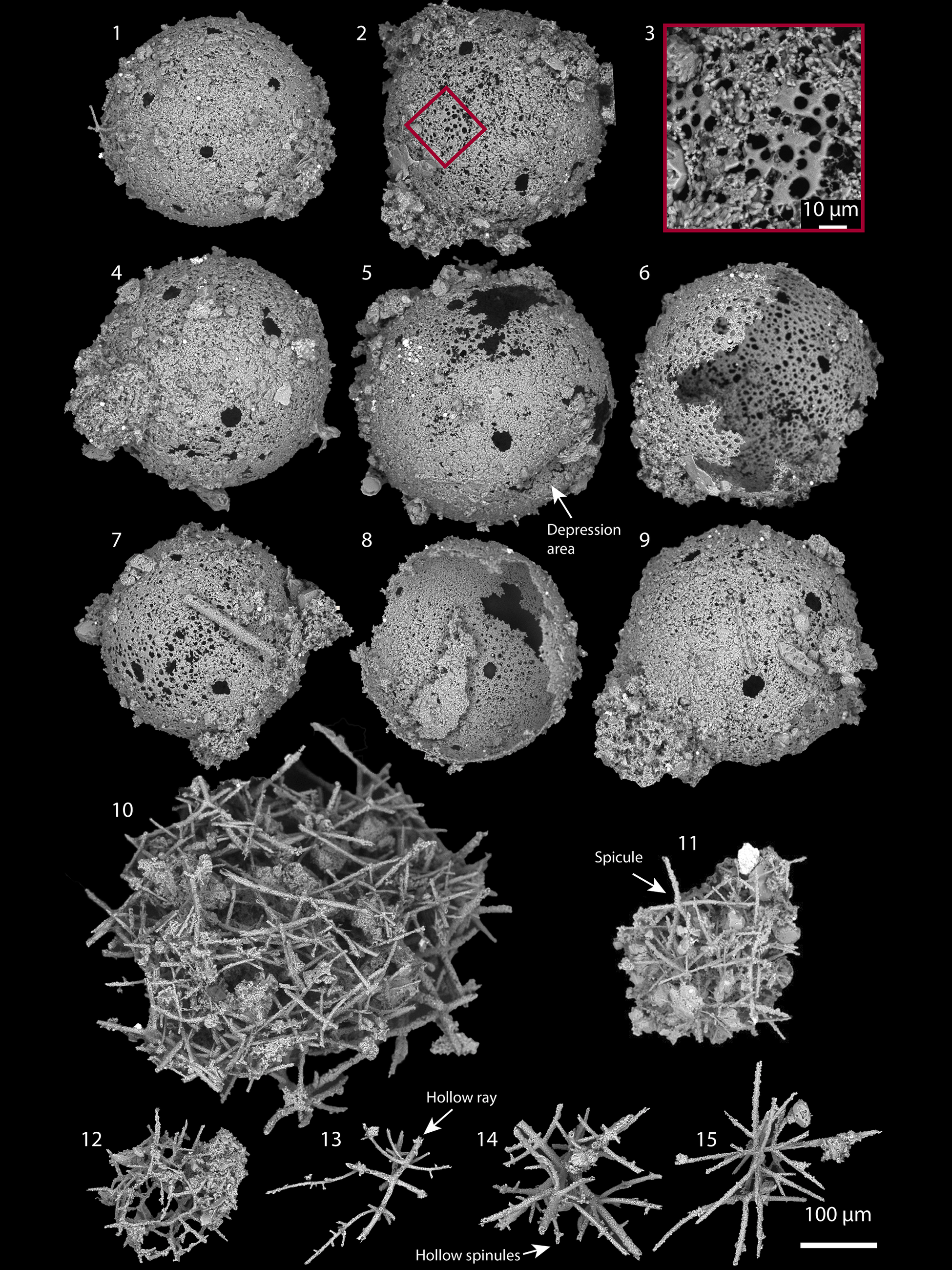

Sample 2RR-14 yielded a well-preserved radiolarian assemblage of relatively low diversity and low abundance, along with abundant sphinctozoans. Numerous specimens of Blastulospongia with diameters of ~300 μm were recovered. The structural simplicity of Blastulospongia, with its singular layer of spherical shells and distinct pore distribution, facilitates rapid identification. Specimens exhibit perfectly round pores, 20–30 μm in diameter, each spaced ~100 μm from the nearest adjacent pores (Fig. 4.1–4.9), on a spherical shell covered with smaller, circular to subcircular pores 2–5 μm in diameter (Fig. 4.3). A depressed area (Fig. 4.5), similar to that observed in specimens of four other species of Blastulospongia, is present on one specimen. The unique perforation patterns on shells with two sizes of pores differs from all other known species of Blastulospongia, warranting designation of a new species.

Figure 4. SEM images of microfossils recovered from sample 2RR14: (1–9) Blastulospongia bouliaensis n. sp. (SEES/2RR-14_BBO01–BBO09, respectively): (2) holotype (SEES/2RR-14_BBO02); (3) patch of enlarged shell showing small pores on specimen (2). (10, 11) Echidnina irregularis Won in Won and Iams, Reference Won and Iams2002 (SEES/2RR-14_EIR01, EIR02). (12) Parechidnina aspinosa (Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999) (SEES/2RR-14_PAS01). (13, 14) Palaeospiculum devoncourtensis Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999 (SEES/2RR-14_PAD01, PAD02). (15) Palaeospiculum reedae Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999 (SEES/2RR-14_PRE01).

The accompanying radiolarian assemblage includes: Echidnina irregularis Won in Won and Iams, Reference Won and Iams2002, Parechidnina aspinosa Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, Palaeospiculum devoncourtensis Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, and Palaeospiculum reedae Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999 (Fig. 4.10–4.15). Compared to the assemblage from three productive samples at Locality 5 in the study by Won and Below (Reference Won and Below1999), this assemblage shares Parechidnina aspinosa, Palaeospiculum reedae, and Palaeospiculum devoncourtensis, and contains one additional species (E. irregularis) that was not previously reported because this genus was not then regarded as a radiolarian (Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999). Five species identified in the 1999 study but absent here include: Archeoentactinia sp. 1 cf. Archeoentactinia incaensis Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, revised Sheng, Kachovich, and Aitchison, Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020, Palaeospiculum arcussimile Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, Palaeospiculum dendroeides Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, Palaeospiculum parvum Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, and Spongomassa nannosphaera Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, which were noted as ‘less common’ or ‘extremely rare.’ When comparing the microfossil assemblage to that of the underlying Inca Formation, our observations align with those of Won and Below (Reference Won and Below1999), with Palaeospiculum devoncourtensis and Blastulospongia bouliaensis new species being characteristic of the Devoncourt Limestone. Thus, both of these taxa emerge as promising accessory species for the Drumian and Guzhuangian stages of the Miaolingian Series, underscoring their potential in stratigraphic correlation.

MCT analysis of Parechidnina aspinosa revealed details of its skeletal construction through the fusion of unirayed spicules, a mechanism identical to that observed in archeoentactinids. This suggests a close phylogenetic relationship between Archeoentactinia Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, revised Sheng, Kachovich, and Aitchison, Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020, and Parechidnina Kozur, Mostler, and Repetski, Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996, sensu Won, Iams, and Reed, Reference Won, Iams and Reed2005, marking a first step toward the understanding relationships among the Archaeospicularia.

Discussion

Phylogenetic affinity of Blastulospongia

Being among the oldest organisms that utilized biominerals for skeletogenesis, the affinity of Blastulospongia has attracted much discussion. Based on the structure, composition, and size ranges of reported specimens, several suggestions have been made. Pickett and Jell (Reference Pickett and Jell1983) proposed that Blastulospongia might be among the earliest sphinctozoans that are single chambered before the development of branching or multichambered forms. The possibility of radiolarian affinity for Blastulospongia was later explored by Bengtson (Reference Bengston1986), suggesting that B. monothalamos Pickett and Jell, Reference Pickett and Jell1983 might be an ancestral radiolarian that was sessile and B. mindyallica Bengtson, 1986 might be the planktic descendant of this genus (Petrushevskaya, Reference Petrushevskaya1977). Depressions found on B. polytreta Conway Morris and Chen, Reference Conway Morris and Chen1990 that are interpreted as primary features led Conway Morris and Chen (Reference Conway Morris and Chen1990) to suggest that it is a radiolarian, whereas Chang et al. (Reference Chang, Feng and Zhang2018) placed it in open nomenclature. Affinity to sphinctozoans was deemed questionable based on the lack of pore-size variations on the specimens, which is a distinct feature for sponges (Conway Morris and Chen, Reference Conway Morris and Chen1990). Kouchinsky et al. (Reference Kouchinsky, Bengtson, Landing, Steiner, Vendrasco and Ziegler2017) interpreted them as possibly representing unilocular tests of benthic or semibenthic foraminiferans. Luzhnaya et al. (Reference Luzhnaya, Zhegallo, Zaitseva and Ragozina2023) placed them among other problematic Cambrian spheromorphic forms with debatable affinities.

Blastulospongia bouliaensis n. sp. displays striking similarity to sphinctozoan sponge chambers with ostia (Fig. 5; Senowbari-Daryan and Rigby, Reference Senobari-Daryan and Rigby2011). The perforations on B. bouliaensis n. sp. exhibit two distinct size variations (Fig. 4.2, 4.3), comparable to larger ostia and smaller exopores in sponge chambers of sphinctozoans. Sponge chambers can have one or both types of these pores co-existing. Both ostia and exopores serve as part of the inhalant canal system (Conway Morris and Chen, Reference Conway Morris and Chen1990; Senowbari-Daryan and Rigby, Reference Senobari-Daryan and Rigby2011). Perforated cylindrical microfossils recovered from the Inca Formation underlying Devoncourt Limestone strongly resemble the spongocoel of chambered sponges. (Specimens shown by Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020, Fig. 5.2 were recovered from sample SEES/TH12 but were not reported at that time.) Spongocoels with osculum and endospores are part of the internal exhalant canal system. The size ratio between spongocoels in the Inca Formation and Cambrian species of Blastulospongia suggests their compatibility as skeletal components of chambered sponges (Fig. 5). Endopores observed in the spongocoels of the Inca Formation range in size from 2−15 μm. Because the endopore sizes can match those of the exopores (Senowbari-Daryan and Rigby, Reference Senobari-Daryan and Rigby2011) the smaller endopores shown in Figure 5.2 lend credence to the similarly minute-sized exopores on B. bouliaensis n. sp. (Fig. 4.2, 4.3). The resemblance of the other four species of Blastulospongia (Fig. 6) to sponge chambers with exopores of the Porate group (Fig. 5.4) is striking. All five species of Blastulospongia have specimens with dimpled areas, resembling the concave walls of the chambers as these skeletal components stacked upon one another (Fig. 5.3, 5.6). Notably, all five members of the genus exhibit intact spherical shapes without traces of the spongocoels, indicating a likely moniliform growth form, where asiphonate chambers are stacked one above another (Fig. 5.6). Specimens with multiple dimpled areas (e.g., species of Blastulospongia from the Medvezhya Formation by Kouchinsky et al., Reference Kouchinsky, Bengtson, Landing, Steiner, Vendrasco and Ziegler2017) could represent chambers of polyglomerate, uviform, or polyplatyform sphinctozoans, in which numerous deformed chambers form aggregates (Senowbari-Daryan and García-Bellido, Reference Senowbari-Daryan, García-Bellido, Hooper, Van Soest and Willenz2002). Specimens without signs of attachment sites could represent single-chambered forms (Senowbari-Daryan and Rigby, Reference Senobari-Daryan and Rigby2011). It is worth noting that even the smaller chambered sponges described thus far are generally of millimeter scale. However, it is not unexpected that submillimeter forms are found in radiolarian studies, because researchers are accustomed to working within this size range when identifying fossils. Observations made during this investigation allow us to address a long-standing debate regarding the higher-level classification of this genus, supporting sphinctozoan rather than radiolarian affinity (Pickett and Jell, Reference Pickett and Jell1983; Bengtson, Reference Bengston1986; Conway Morris and Chen, Reference Conway Morris and Chen1990).

Figure 5. Comparison of spongocoels of Blastulospongia, from the Inca Formation to the morphologies of multichambered sponges as depicted in diagrams from Senowbari-Daryan and Rigby (Reference Senobari-Daryan and Rigby2011). (1) Blastulospongia bouliaensis n. sp. from the Devoncourt Limestone. (2) Spongocoels from the Inca Formation (from sample SEES/TH12 of Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020), Georgina Basin.. (3) Blastulospongia polytreta as illustrated by Conway Morris and Chen (Reference Conway Morris and Chen1990; reproduced with permission, Cambridge University Press License 6067341135436). (4) Diagram illustrating morphologies of Aporate and Porate groups of chambered sponges. (5) Reconstruction of Paleozoic multichambered sponge Girtyocoelia beedei Girty, Reference Girty1908 with the spongocoel showing strong similarities to those recovered from the Inca Formation. (6) Diagram illustrating the moniliform form of multichambered sponges.

Figure 6. Age ranges of five species of Blastulospongia across three Cambrian Series.

Taxonomic assignment of early radiolarians and their evolution

The recovery of Cambrian spheroidal fossils, including Blastulospongia, and their classification as radiolarians by some studies (White, Reference White1986; Braun et al., Reference Braun, Chen, Waloszek and Maas2007; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Feng, Feng and Ling2014; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Feng and Zhang2018; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Feng, Cao, Zhang, Ye and Gu2019; Zhang and Feng, Reference Zhang and Feng2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Feng, Nakamura and Suzuki2021; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Ma, Dong, Xu and Yi2025), has initiated an alternative hypothesis of early radiolarian evolution, challenging the view of a spicular origin. This hypothesis disputes the notion that spicular radiolarians gave rise to later forms, e.g., Entactinaria, Albaillellaria, and Spumellaria (Kozur et al., Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996; Dumitrica et al., Reference Dumitrica and De Wever2000; De Wever et al., Reference De Wever, Dumitrica, Caulet and Caridroit2001) and instead proposes an early diversification of radiolarians in the lower Cambrian, with Spumellaria and Archaeospicularia representing two separate lineages (e.g., Cao et al., Reference Cao, Feng, Feng and Ling2014; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Feng, Cao, Zhang, Ye and Gu2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Feng, Nakamura and Suzuki2021). Blastulospongia resembles spumellarian radiolarians in having similar-sized spherical shells without spicular components. However, it exhibits subtle morphological differences because typical spumellarian tests are latticed, reticular or spongy, and multispherical, whereas Blastulospongia has smooth shells with circular holes and is single layered.

Some lower Cambrian (Cambrian Series 2) sphaeroids from South China display stronger shell morphological resemblances with typical spumellarians (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Feng, Cao, Zhang, Ye and Gu2019; Zhang and Feng, Reference Zhang and Feng2019). However, whereas Paraantygopora Ma and Feng in Ma et al., Reference Ma, Feng, Cao, Zhang, Ye and Gu2019 and Braunosphaera have well-preserved external morphologies, their internal structures, which are critical for higher-level classification, are yet to be well-illustrated (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Chen, Waloszek and Maas2007; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Feng, Feng and Ling2014; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Feng and Zhang2018; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Feng, Cao, Zhang, Ye and Gu2019; Zhang and Feng, Reference Zhang and Feng2019). Although MCT scanning was later conducted, the images illustrated are of low resolution and ambiguous, failing to clarify the internal structures of these specimens (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Feng, Cao, Zhang, Ye and Gu2019; Zhang and Feng, Reference Zhang and Feng2019). Forms with appearances typical of radiolarians were observed in thin sections of the lowermost Cambrian (Fortunian) Liuchapo Formation by Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Feng, Nakamura and Suzuki2021), and those authors proposed that they might be the oldest radiolarians ever recovered. They were classified as spumellarians based on the absence of internal spicules. However, based on our MCT work experience with radiolarians viewed in x-ray slices, identifying spicular systems from thin sections alone is problematic, because they would simply appear as bars and dots when cut into slices. Future MCT studies could provide the three-dimensional (3D) data necessary to resolve this issue. Other spheromorphic microfossils, e.g., Archaeooides Qian, Reference Qian1977 and Aetholicopalla Conway Morris in Bengtson et al., Reference Bengston, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990 from the lower Cambrian have problematic higher-level placement but share morphological similarities with radiolarians, although their preservation is not ideal (Qian, Reference Qian1977; Bengtson et al., Reference Bengston, Conway Morris, Cooper, Jell and Runnegar1990). They share with lower Cambrian ‘spumellarians’ the same challenges for interpretation caused by limited preservation of structures and significant taphonomic alteration. Hypotheses regarding their systematic placement range from cysts and embryos to protozoans, algae, or multicellular animals (Luzhnaya et al., Reference Luzhnaya, Zhegallo, Zaitseva and Ragozina2023).

Recovery of well-preserved specimens and careful examination are required to discern taxonomic affinity and provide crucial answers regarding the earliest radiolarians. In the case of Blastulospongia, this genus ranges from middle to upper Cambrian and the evidence presented supports affinity as a sphinctozoan, not a spumellarian. A ~45 Myr gap exists between these early Cambrian genera putatively classified under Spumellaria, and the more widely accepted Spumellaria of the Antygoporidae known from the uppermost Lower Ordovician (Floian 3) (Maletz and Bruton, Reference Maletz and Bruton2007; Kachovich and Aitchison, Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020). Such a significant gap in the fossil record indicates that caution is necessary when considering the early evolution of spumellarians.

Detailed structural analysis of the radiolarian genus Parechidnina is important for resolving the ongoing debate surrounding its family- and order-level classifications, as well as for investigating any possible evolutionary connection between primitive spicular radiolarians and multispherical forms with radial spines (Kozur et al., Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996; Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999; Won and Iams, Reference Won and Iams2002; Won, et al., Reference Won, Iams and Reed2005; Maletz and Bruton, Reference Maletz and Bruton2007; Noble, et al., Reference Noble, Aitchison, Danelian, Dumitrica, Maletz, Suzuki, Cuvelier, Caridroit and O’Dogherty2017; Sheng, et al., Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020). Recovery of well-preserved specimens of Parechidnina aspinosa from the Devoncourt Limestone provides an opportunity to examine their skeletal architecture using MCT imaging techniques. Scrutiny of two specimens of Parechidnina aspinosa reveals that they are exclusively composed of straight and curved rods of varying lengths and thicknesses. This contrasts with the suggestion of Kozur et al. (Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996) that parechidninids are constructed by fusion of various spicule types, including heptactine, hexactine, pentactine, and tetractine spicules. Won’s modified diagnosis of the genus, describing it as a meshwork of the three-dimensionally interwoven shell (Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999), only captures its superficial meshy appearance. Under SEM examination, a rod-constructed shell can superficially resemble a meshwork-based structure but is fundamentally different. In the rod-constructed shells, all rods can be individually traced and digitally separated, with the distinctiveness of each rod evident where they intersect with short or long protrusions (Fig. 7.2). In contrast, meshwork-based structures are continuous wholes, in which the skeletal elements can only be arbitrarily dissected because the beginning or end of each element cannot be distinguished. The diagrams in Figure 7.4 and 7.5 provide simplified illustrations of these two structures, which are fundamentally different in their modes of skeletal genesis.

Figure 7. MCT 3D model of Parechidnina aspinosa (Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999) (SEES/2RR-14_PAS01) and diagrams illustrating rod- and meshwork-constructed skeletal structures: (1) complete 3D model with an inserted digital sphere for clearer visual discrimination of the structure; (2) completely digitally dissected 3D model, with largest spicules false-colored red, medium-sized spicules false-colored yellow, small spicules above the basal layer false-colored blue, and radially arranged spicules false-colored green; (3) 3D models with radially arranged spicules (primitive spines) false-colored green. (4, 5) Simplified diagrams illustrating rod- and meshwork-constructed structures.

A diagnosis for Echidninidae was presented by Kozur et al. (Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996) defining the family as comprising globular, spongy test formed by interlocked or fused point-centered spicules of tetractine, pentactine, hexactine and heptactine type, surrounding an inner cavity. This diagnosis specifically limits the spicule types to those that are ‘point-centered.’ However, the exclusion of unirayed spicules in this initial diagnosis could be because such simple-formed spicules were not observed until later studies, e.g., in ?Echidnina monactina Won in Won and Iams, Reference Won and Iams2002 and in the current study. Won tentatively assigned E. monactina to Echidnina Bengston, Reference Bengston1986, sensu Won and Iams, Reference Won and Iams2002, because, although it exhibits the shell construction characteristic of echidninids, it only possesses ‘unirayed spicules’ rather than point-centered spicules. With the identification of unirayed spicules in Parechidnina, it is appropriate to recognize that that in addition to point-centered spicules, unirayed spicules also exist among Paleozoic radiolarians. The diverse monaxon (single-rayed) spicules of poriferids, a lineage unrelated to radiolarians but sharing a variety of spicule shapes, offers additional support for the inclusion of unirayed spicules into the classification of radiolarian spicule types (Łukowiak et al., Reference Łukowiak, Van Soest, Klautau, Pérez, Pisera and Tabachnick2022). The diagnosis of Echidninidae is amended to include all spicule types, allowing Parechidnina to be reassigned from Aspiculidae to Echidninidae within the order Archaeospicularia.

MCT analysis offers valuable insight into phylogenetic relationships among various groups of Archaeospicularians. Despite the distinct appearances of parechidninids and archeoentactinids, this study reveals their close relationship. MCT penetrates intricate structures and can be used to recognize their identical skeletal construction mode: parechidninids utilize fusion of unirayed spicules, whereas archeoentactinids employ point-centered spicules (Fig. 7; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020). Both groups exhibit a basal layer constructed of robust spicules, with progressively smaller spicules layered on top, resulting in a thick 3D shell wall. Additionally, both groups possess radially positioned spicules that form primitive spines. This discovery marks an initial step toward comprehending the phylogeny of the Archaeospicularids. This order is characterized by its ‘spicule- constructed’ nature, with its families distinguished by the presence of one or multiple centers of skeletal genesis, exemplified by the Palaeospiculidae and Echidninidae, respectively. Within Echidninidae, individual genera differ based on the position of centers of skeletal genesis. For instance, Echidnina features skeletal genesis centers on the same spherical surface, whereas Archeoentactinia and Parechidnina exhibit multilayered skeletal genesis, a mechanism that can give rise to multispherical species, as observed in younger forms.

Systematic paleontology

Phylum Porifera Grant, Reference Grant and Todd1836

Class Demospongea Sollas, Reference Sollas1875

Order Agelasida Verrill, Reference Verrill1907

Family Sebargasiidae de Laubenfels, Reference de Laubenfels and Moore1955

Genus Blastulospongia Pickett and Jell, Reference Pickett and Jell1983

Type species

Blastulospongia monothalamos Pickett and Jell, Reference Pickett and Jell1983 (NMV P75150) from the Middle Cambrian First Discovery Limestone Member of the Coonigan Formation near Mootwingee, western New South Wales, Australia.

Diagnosis

Single-chambered, asiphonate, porate sphinctozoans, without internal structures (Pickett and Jell, Reference Pickett and Jell1983).

Occurrence

Blastulospongia has been recognized in Australia, China, and Russia since Pickett and Jell (Reference Pickett and Jell1983) first established the genus based on B. monothalamos, a species characterized by perforated, spherical, thin-walled, hollow siliceous shells with diameters of 1–1.9 mm. Subsequent discoveries include three species with a size range of 280–800 μm including: B. mindyallica from the Mungerebar Limestone in the Georgina Basin of far northwest Queensland (Bengtson, 1986), B. polytreta from the Shuijingtuo Formation in Hubei, China (Conway Morris and Chen, Reference Conway Morris and Chen1990), and a species described in open nomenclature from the Medvezhya Formation in Siberian Russia (Kouchinsky et al., Reference Kouchinsky, Bengtson, Landing, Steiner, Vendrasco and Ziegler2017), spanning from the lower to upper Cambrian. In addition to these four species, other specimens with similar affinity have been documented in open nomenclature and classified as radiolarians or problematic fossils (White, Reference White1986; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Feng and Zhang2018). Won and Below (Reference Won and Below1999) reported the occurrence of a species of Blastulospongia in the Devoncourt Limestone, but it was neither figured nor described.

Remarks

In the studies reporting Blastulospongia, each stratigraphic horizon yields an abundance of a single species making them useful age markers for the Cambrian (Fig. 6). The oldest, an unnamed species from the Medvezhya Formation in Siberia, is assigned to the boundary of the Fortunian and Cambrian Stage 2 in the lowermost Terreneuvian (Kouchinsky et al., Reference Kouchinsky, Bengtson, Landing, Steiner, Vendrasco and Ziegler2017). Blastulospongia polytreta from the Shuijingtuo Formation in Hubei, China is correlated globally to the international upper Stage 3 of Cambrian Series 2 (Conway Morris and Chen, Reference Conway Morris and Chen1990; Geyer, Reference Geyer2019). Blastulospongia monothalamos from the First Discovery Limestone can be assigned to the Australian upper Ordian Stage, correlating globally to the lower Wuliuan Stage of the lowermost Miaolingian Series (Runnegar and Jell, Reference Runnegar and Jell1976; Pickett and Jell, Reference Pickett and Jell1983; Geyer, Reference Geyer2019). Blastulospongia bouliaensis n. sp. from the Devoncourt Limestone reported herein is assigned to the Australian Undillan and lower Boomerangian stages, correlating globally to the upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian in the middle Miaolingian (Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999; Geyer, Reference Geyer2019). Finally, B. mindyallica from the Mungerebar Limestone is assigned to the Australian Mindyallan, which correlates globally to the upper Guzhangian (Bengtson, 1986; Geyer, Reference Geyer2019).

Blastulospongia bouliaensis new species

Holotype

Specimen SEES/2RR-14_BBO02 illustrated in Figure 4.2, known from upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian limestone of the Devoncourt Limestone, Georgina Basin, Australia.

Diagnosis

Spherical sponge chamber of ~300 μm diameter. Ostia 20–30 μm in diameter, each spaced ~100 μm from nearest adjacent ostium and evenly distributed across the thin shell. Smaller, spherical to subspherical exopores ranging from 2–5 μm adorn the entire chamber. A depressed area can also be present.

Occurrence

Upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian (middle Cambrian) Devoncourt Limestone, Rogers Ridge, Georgina Basin, Australia

Description

Specimens have an average diameter of ~300 μm (Fig. 4.1–4.9). They exhibit circular pores 20–30 μm in diameter, spaced ~100 μm from the closest adjacent pore, on a thin spherical shell covered with smaller, spherical to subspherical pores ranging from 2–5 μm (Fig. 4.3). A depressed area was observed on one specimen (Fig. 4.5).

Etymology

Named after Boulia, a township close to the sample locality at Rogers Ridge.

Materials

More than 100 specimens recovered from sample 2RR-14 from the upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian Devoncourt Limestone, Rogers Ridge, Georgina Basin, Australia.

Remarks

Intact spherical shapes of Blastulospongia bouliaensis n. sp. coupled with the presence of a depressed area, suggest a likely moniliform growth form in multichambered sponges, with asiphonate chambers stacked above one another. Future studies utilizing thin-section analysis or nondestructive MCT techniques could help recover chambers that remain intact together, providing additional evidence for their taxonomic assignment.

Phylum Radiozoa Cavalier-Smith, Reference Cavalier-Smith1987

Class Polycystina Ehrenberg, Reference Ehrenberg1838, emend. Riedel, Reference Riedel1967

Order Archaeospicularia Dumitrica, Caridroit, and De Wever, Reference Dumitrica and De Wever2000

Family Echidninidae Kozur, Mostler, and Repetski, Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996

Diagnosis

“Isolated, but interlocked or fused, primary point-centered tetractine, pentactine, hexactine and heptactine spicules form a subglobular, loose, spongy, hollow shell” (Kozur et al., Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996, p. 248).

Revised diagnosis

Isolated, but interlocked or fused, point-centered or unirayed spicules forming a subglobular, loose, spongy, hollow shell.

Genus Echidnina Bengston, Reference Bengston1986, sensu Won and Iams, Reference Won and Iams2002

Type species

Echidnina runnegari Bengston, Reference Bengston1986 (UNEF 16424) from the upper Cambrian Mungerebar Limestone of Queensland, Australia.

Echidnina irregularis Won in Won and Iams, Reference Won and Iams2002

Reference Won and Iams2002 Echidnina irregularis Won in Won and Iams, p. 25, fig. 5.5–5.12.

Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020 Echidnina irregularis; Sheng et al., p. 68, fig. 4.19, 4.20.

Holotype

Specimen GSC-121964(MP2-2) from bed 26 of Martin Point section 2 (James), Franconian, (upper Cambrian), Cow Head Group, western Newfoundland.

Diagnosis

“Skeleton consisting of several to numerous large, individual interlocked spicules that form a hollow, irregular to subspherical shell. Spicule consisting of two vertical rays and five, six, seven, or eight whorled rays” (Won and Iams, Reference Won and Iams2002, p. 25).

Occurrence

Middle Cambrian (Miaolingian Series) of the Inca Formation from the Georgina Basin, Australia. Late Cambrian (Furongian Series) units in the Cow Head Group, Newfoundland, Canada. Upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian (middle Cambrian) Devoncourt Limestone, Rogers Ridge, Georgina Basin, Australia.

Description

Both specimens of Echidnina irregularis consist of numerous interlocked multi- rayed spicules of various sizes. No ray modification or fusion was observed. Both specimens are infilled, and details of their internal construction are obscured.

Materials

Two specimens recovered from sample 2RR-14 from the upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian Devoncourt Limestone, Rogers Ridge, Georgina Basin, Australia.

Remarks

The specimen shown in Figure 4.10 is considerably larger with a diameter of 450 μm.

Genus Parechidnina Kozur, Mostler, and Repetski, Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996, sensu Won et al., Reference Won, Iams and Reed2005

Type species

Parechidnina nevadensis Kozur, Mostler, and Repetski, Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996. The specimen on pl. 1, fig. 5; holder-no. 23-6-96/III-1-4; USNM 494.846 from the Lower Tremadocian Windfall Formation, Antelope Range, Eureka County, Nevada, USA.

Diagnosis

“Heptactine, hexactine, pentactine and tetractine spicules are fused to a loose, hollow, irregular latticed shell with large, triangular to rectangular or rhombohedral pores and numerous needle-like outward-directed spines. Connecting bars between these spines and further fused spicules above the shell form an imperfect, loose spongy shell. In the largest part of the test both shells are united to a single, loose spongy shell” (Kozur et al., Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996).

Revised diagnosis

A hollow, spherical to subspherical test constructed from an indefinite number of interlocked and fused unirayed spicules. Basal framework constructed of straight and curved robust spicules of various lengths, with smaller spicules arranged at different orientations upon it. More or less radially arranged spicules forming primitive to well-developed spines.

Remarks

Upon gaining familiarity with this genus through observation of digital 3D models of Parechidnina aspinosa, further examination of SEM images of Parechidnina nevadensis specimens depicted by Kozur et al. (Reference Kozur, Mostler and Repetski1996) led to the determination that Parechidnina nevadensis is likewise constructed by the fusion of unirayed spicules. Consequently, the diagnosis is amended herein, based on the type species Parechidnina nevadensis and the oldest species assigned to this genus, Parechidnina aspinosa.

Parechidnina aspinosa (Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999)

Figures 4.12, 7, Supplementary Dataset file SDS1

Reference Won and Below1999 Aitchisonellum aspinosus Won in Won and Below, p. 352, pl. 8, figs. 1–5; pl. 10, figs. 9, 10.

Reference Won and Iams2002 Parechidnina aspinosa s.1.; Won in Won and Iams, p. 31, figs. 11.1, 11.2, 11.15, 1.16, 12.1.

Reference Won, Iams and Reed2005 Parechidnina aspinosa Morphotype 2; Won in Won et al., p. 443, fig. 6.2, 6.4, 6.8, possiby 6.9 and 6.13.

Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020 Parechidnina aspinosa Won; Sheng et al., p. 68, fig. 3.21.

Holotype

Specimen PNU 7309W-00242 in sample 7309 collected from the Inca Formation, locality 3 north of Rogers Ridge (139°58’36.6”E, 21°44’50.4”S), far North Queensland, Australia (Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, p. 356, pl. 8.1).

Diagnosis

Hollow, subspherical test composed of indefinite number of fused unirayed spicules. Basal framework consisting of straight and curved robust spicules fused in an irregular crisscross pattern. Smaller spicules, arranged at various orientations, formed upon it, resulting in 3D shell wall. Short, primitive spines formed by more or less radially arranged spicules (emended from Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999).

Occurrence

Middle Cambrian (Miaolingian Series) Inca Formation from the Georgina Basin, Australia. Late Cambrian (Furongian Series) and earliest Ordovician (Tremadocian Stage) units in the Cow Head Group, Newfoundland, Canada. Upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian (middle Cambrian) Devoncourt Limestone, Rogers Ridge, Georgina Basin, Australia.

Description

A hollow, subspherical, ~250 μm diameter shell, with ~20 short primitive and ~70 μm long spines (Fig. 7). Shell framework constructed of long, robust, unirayed spicules. ≤ 240 μm long, 10 μm thick (Fig. 7.2, red). Shorter unirayed spicules, ≤ 100 μm long, occur on top of the framework with some on the same spherical surface, and others lying tangentially (Fig. 7.2, yellow). Even shorter unirayed spicules, < 100 μm long, 5 μm thick, lying at ~30° to the spherical surface (Fig. 7.2, blue). Unirayed spicules ~70 μm long more or less orthogonal to spherical surface, forming primitive spines (Fig. 7.2, 7.3, green).

Materials

Three specimens from the upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian Devoncourt Limestone, Rogers Ridge, Georgina Basin, Australia.

Remarks

The monospecific genus Aitchisonellum Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999 was introduced by Won (in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999). It was later recognized as a junior synonym of Parechidnina by Won et al. (Reference Won, Iams and Reed2005) who later provided an expansion of the diagnosis (Won et al., Reference Won, Iams and Reed2005). MicroCT specimen examination during this study provided further insight into the skeletal framework of this taxon and suggests that a further minor emendment to the diagnosis is appropriate. The examined specimen exhibits a complete basal layer, but smaller spicules (Fig. 7.2, blue) appear less developed. This can be attributed either to preservation factors or ontogeny. The nonuniformity in the length and curvature of the unirayed spicules, which comprise the framework of the shell, contributes to the subspherical shape observed in this species. This characteristic is also seen in Archeoentactinia incaensis and Archeoentactinia tetractinia Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, revised Sheng, Kachovich, and Aitchison, Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020, investigated by Sheng et al. (Reference Sheng, Kachovich and Aitchison2020). The basal layers of these taxa also consist of point-centered spicules of various sizes. Differences in the timing of skeletal genesis of each spicule could be the controlling factor for sphericity among these early radiolarians.

Family Palaeospiculidae Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999

Reference Won and Below1999 Palaeospiculumidae Won in Won and Below, p. 338.

Reference Maletz2011 Palaeospiculidae; Maletz, p. 130 (spelling corrected under ICZN, 1999, Art. 29).

Genus Palaeospiculum Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999

Type species

Palaeospiculum burkensis Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999 from limestone concretions of the Inca Formation, Georgina Basin, Australia (Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999).

Palaeospiculum devoncourtensis Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999

Reference Won and Below1999 Palaeospiculum devoncourtensis Won in Won and Below, p. 341, pl. 4, figs. 10–13, 18–20.

Holotype

Specimen PNU 7405E-1742 from sample 7405 collected the Devoncourt Limestone, north of Rogers Ridge (139°59’10.6”E, 21°44’26.5”S), far North Queensland, Australia (Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999).

Diagnosis

Point-centered spicular skeleton constructed by a crossing of three curved rods; orthogonally arranged six-rayed hollow spicular skeleton with curved spinules on each ray; apical and basal ray lengths variable, but basal rays longer than apical rays; well-developed spinules close to juncture of rays; spinules distally diminished into thorns; longer spinules on longer rays; longest spinules on longest rays.

Description

Both specimens exhibit the prominent characteristics of hollow skeletal elements, observable on both rays and spinules.

Materials

Two specimens recovered from sample 2RR-14 from the upper Drumian Miaolingian–lower Guzhangian Devoncourt Limestone, Rogers Ridge, Georgina Basin, Australia.

Remarks

The readily discernible characteristics of both the curved spinules and hollow skeletons of Palaeospiculum devoncourtensis contribute to its potential as a promising candidate for an accessory fossil for the upper Drumian–lower Guzhangian.

Palaeospiculum reedae Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999

Reference Won and Below1999 Palaeospiculum reedae Won in Won and Below, p. 350, pl. 4, figs. 14–16.

Holotype

Specimen PNU 7306J-1437 from sample 7306J collected the Devoncourt Limestone, north of Rogers Ridge (139°58’36.6”E, 21°44’50.4”S), far North Queensland, Australia (Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999).

Diagnosis

“A point-centered spicular skeleton consisting of six rays, apical rays shorter than basal rays, but both of variable length, one group of straight spinules arising at one point and radially arranged on each ray” (Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999).

Description

The structure of the specimen is consistent with the diagnosis, however the differences between lengths of apical and basal rays are not significant.

Materials

One specimen recovered from sample 2RR-14 from the upper Drumian Miaolingian middle Cambrian Devoncourt Limestone, Rogers Ridge, Georgina Basin, Australia.

Remarks

Palaeospiculum reedae closely resembles Palaeospiculum devoncourtensis but is readily distinguished by its straight, rather than curved, spinules. The species is rare in the present material, represented by a single specimen, a scarcity that parallels its rarity in the assemblages documented by Won and Below (Reference Won and Below1999).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Botting, together with reviewers S. Kershaw and P. Noble for their helpful reviews of this manuscript. We also thank L. Deer, M. Elmes, and S. Perera at the School of the Environment, University of Queensland for their assistance with sample collection from the Georgina Basin. We thank C. Evans at the University of Queensland Julius Kruttschnitt Mineral Research Centre (Brisbane, Australia) for her willing assistance with Xradia Versa 500 MCT imaging. Financial support toward investigation of early Paleozoic radiolarians was provided by the Australian Research Council (ARC DP 1501013325 to J.C. Aitchison).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Data availability statement

Supplementary Data Set 1.— A surface file of Parechidnina aspinosa Won in Won and Below, Reference Won and Below1999, analyzed using MCT in this study, is exported as a .stl file that can be used to generate interactive 3D models. It is available at the Zenodo Digital Repository (http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15694809). The file can be downloaded and viewed interactively on open-source 3D software sites, e.g., FreeCAD [https://www.freecad.org] and Sketchfab [https://sketchfab.com/feed]. Readers can rotate and enlarge the 3D models to examine them from all angles.”