Introduction

Nowadays citizens contributing to the provision of public services and goods have become a marked trend in Western states (e.g., Bailey Reference Bailey2012; Healey Reference Healey2015). They take matters into their own hands by tackling wicked issues, such as urban revitalization, well-being, and sustainability. With their initiatives, citizens often have the ambition to form a durable cooperation and they have a hands-on approach (Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk Reference Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk2016). These initiatives are named in different ways in the literature, such as social enterprises (Cheng Reference Cheng2015; Teasdale Reference Teasdale2012), self-organization (Anttila and Stern Reference Anttila and Stern2005; Van Meerkerk et al. Reference Van Meerkerk, Boonstra and Edelenbos2013), and grassroots initiatives (Ornetzeder and Rohracher Reference Ornetzeder and Rohracher2013).

In this research, we refer to their activities with the concept of citizen initiatives, which is a form of self-organization in which citizens mobilize energy and resources to collectively define and carry out projects aimed at providing public goods or services for their community. Citizens control the aims, means, and actual implementation of their activities, but they often link to governments and other formal institutions, as their work field contains public domain and they, therefore, find themselves in institutionalized settings (Bakker and Denters Reference Bakker and Denters2012; Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk Reference Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk2016; Healey Reference Healey2015). They often arise as self-reliance responses to the failure of the state and market to provide public goods (Teasdale Reference Teasdale2012) and fill the gap caused by receding governments.

It is especially the changing role of the state that has increased the current attention for citizen initiatives (cf. Brandsen Reference Brandsen, Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk2016). Although in Western Europe the government is still the primary provider of public goods, some governments increasingly aim to shift this responsibility to the community. In some countries, like the Netherlands and the UK, economic and political uncertainties have led to public retrenchments and receding governments, which at the same time have embraced a political ideology that sees community self-strength as answer for societal problems (e.g., Brandsen et al. Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017; Eriksson Reference Eriksson2012; Healey Reference Healey2015).

In the literature, we see that citizen initiatives are often approached as a specific form of citizen participation (Arnstein Reference Arnstein1969) and co-creation (Voorberg et al. Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2015). In Arnstein’s famous ladder of citizen participation (Reference Arnstein1969), citizen initiatives can normatively be placed at the highest level of citizen power, citizen control, meaning citizens being in full charge of a specific program or institution. As such, citizen initiatives differ from the politically oriented, more passive, ballot initiatives, which include public voting or forcing legislative bodies to consider subjects of the initiatives. Citizen initiatives also differ from regular coproduction, because citizens take the lead as initiators, and government acts as follower or facilitator instead of citizens being involved in the production process under (strict) conditions and frameworks set by governments (Brandsen and Honingh Reference Brandsen and Honingh2016; McLennon Reference McLennan2018; Voorberg et al. Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2015).

Although the self-organizing role of citizens has gained a significant societal relevance, less systematic attention has been paid to this phenomenon in administrative sciences, which is dominated by a focus on mainstream participation processes and coproduction (Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk Reference Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk2016; Voorberg et al. Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2015). However, citizen initiatives take an important part in the world of politics and public administration; as in modern society, citizens not only have more capacities and resources (knowledge, time, etc.) to bring public services and deal with public issues, but they also have given more room from governments to organize such services themselves. Their initiatives become alternatives to governmental public service delivery. We therefore need to know more about what citizen initiatives actually are (main characteristics), what they actually perform/bring about and what factors determine their outcomes (cf. Denters Reference Denters, Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk2016).

Regarding these topics, the current literature falls short in demonstrating the evidence-based knowledge on outcomes of citizen initiatives and on the factors impacting these outcomes. Although different case studies of citizen initiatives and their potential outcomes have been performed in various disciplines, (e.g., Aladuwaka and Momsen Reference Aladuwaka and Momsen2010; Newman Reference Newman2007), to our knowledge, there is not any literature that compares these studies in order to generate systematic and coherent overview.

Based on the above limitations in current research and societal relevance of citizen initiatives, we aim to present a systematic overview of what is known about citizen initiatives in existing studies, by focusing on the following research question:

What do we know about the characteristics, theoretical approaches, outcomes, and factors influencing the outcomes of citizen initiatives?

We conducted a systematic literature review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA). The systematic literature reviews have proven to be valuable in other (related) fields of research (see for example: Garkisch et al. Reference Garkisch, Heidingsfelder and Beckmann2017; Laurett and Ferreira Reference Laurett and Ferreira2018; Voorberg et al. Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2015). In this review, we draw on studies from the social sciences and in particular from administrative sciences and sociology records to define and understand citizen initiatives from a multidisciplinary perspective.

Methodology

The PRISMA reporting standard is the most commonly used set of guidelines for reporting the literature reviews and meta-analyses (Fink Reference Fink2014). A systematic literature review enables us to identify, evaluate, and synthesize the existing body of completed records in a transparent way.

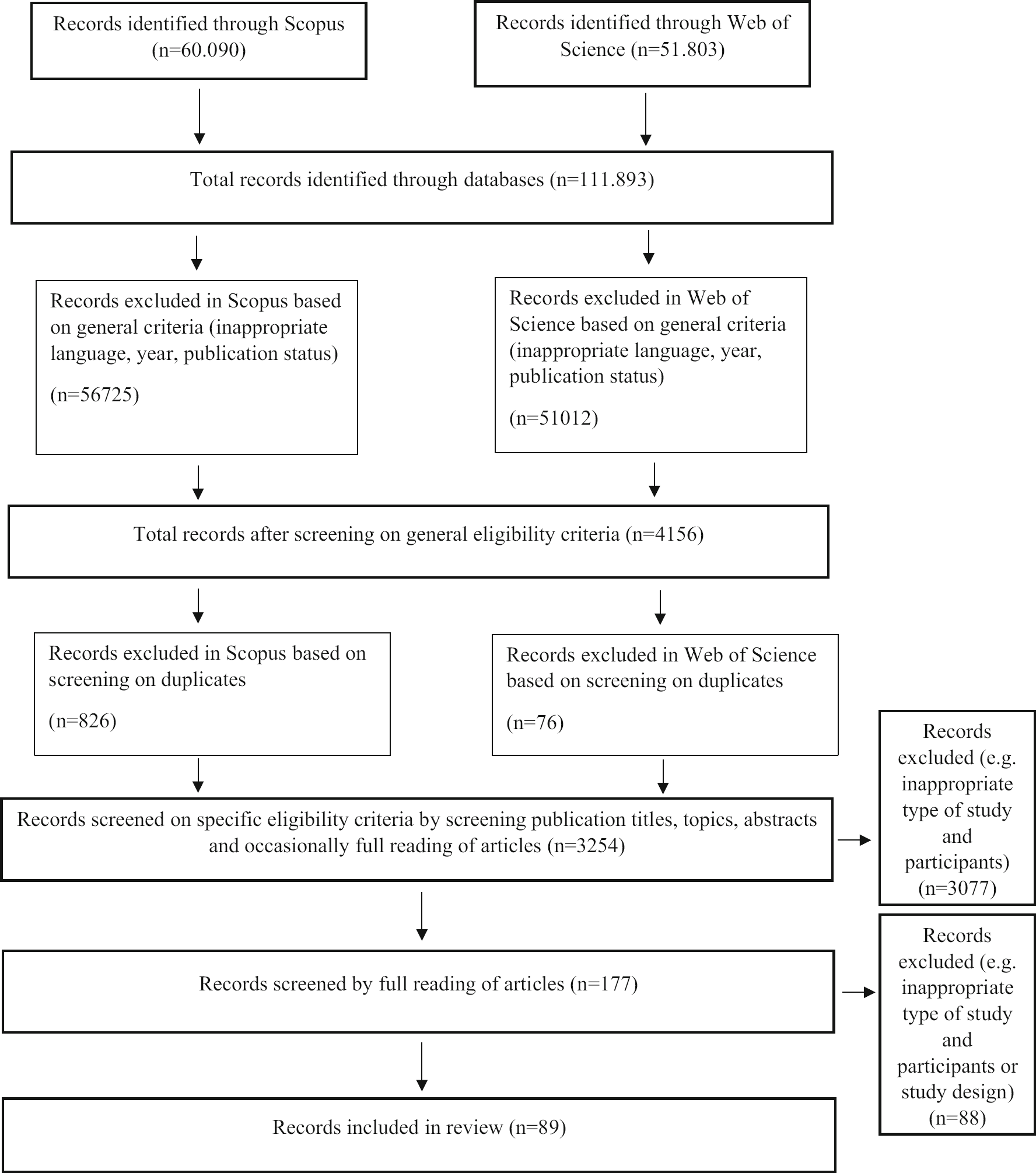

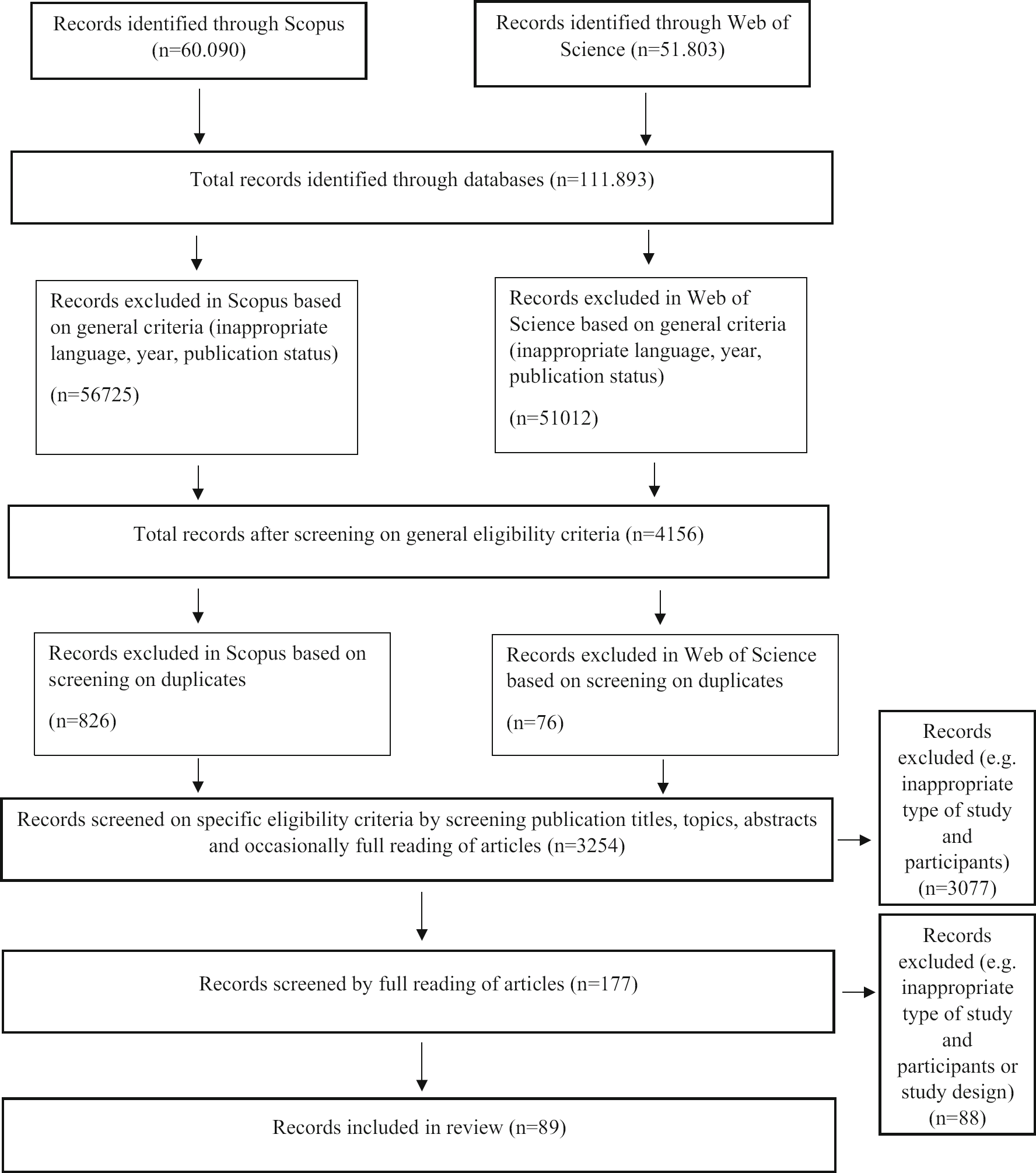

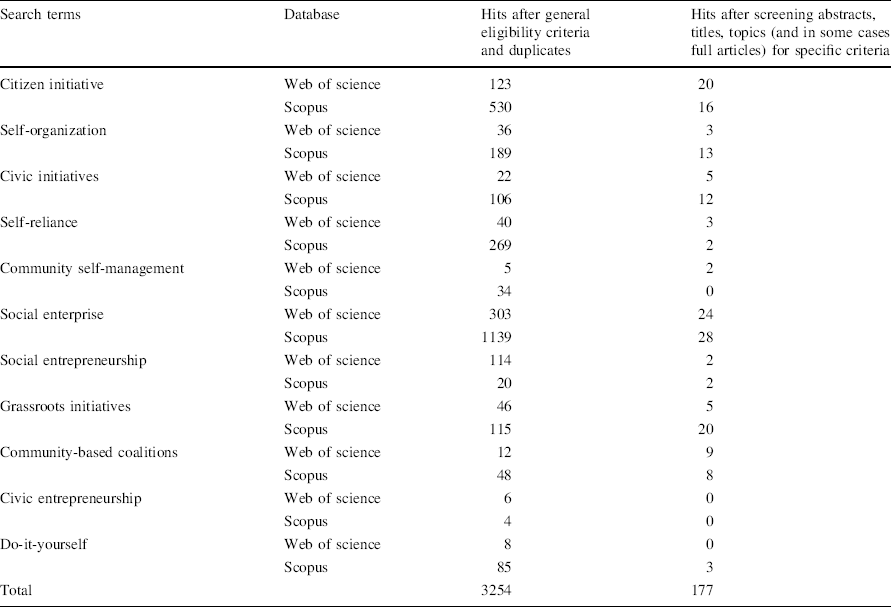

We performed the review with an electronic database search of two databases: Scopus and Web of Science. This strategy covered over 110.000 records, thereby strengthening the range of studies identified and screened in the review (see Fig. 1 for the flow diagram). We started the review broad by using multiple terms during the electronic search (see Table 1), taking into account the variety of terms used to describe citizen initiatives. In this diversity of citizen initiatives, we looked for patterns in outcomes and factors. Because the broad strategy resulted in a very high number of hits, we did not include other search strategies, for instance the inclusion of books, as sometimes is done in systematic reviews with only one or two target concepts (cf. Voorberg et al. Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2015). However, we acknowledge that this choice may have caused a bias in the selection of publications.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram for identifying, screening, and including records

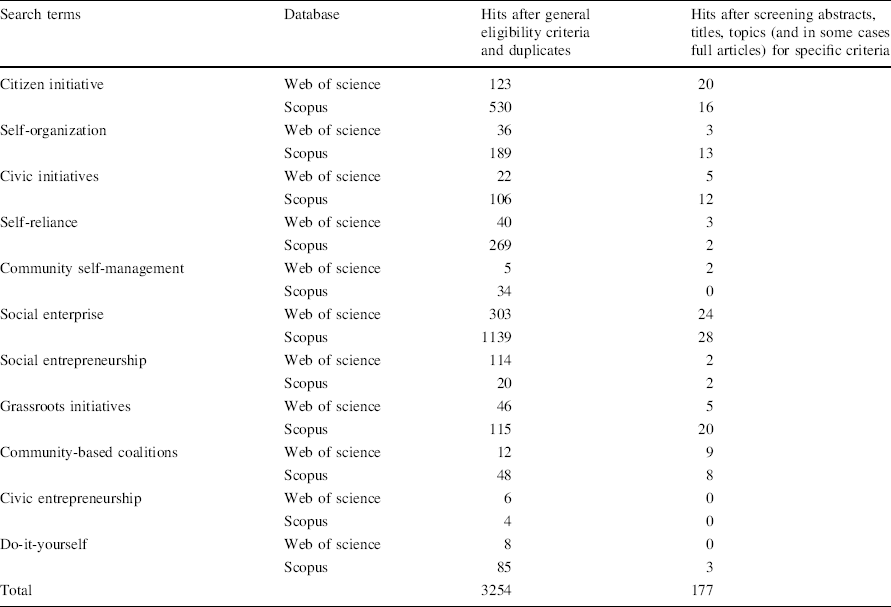

Table 1 Hits by search terms

Search terms |

Database |

Hits after general eligibility criteria and duplicates |

Hits after screening abstracts, titles, topics (and in some cases full articles) for specific criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

Citizen initiative |

Web of science |

123 |

20 |

Scopus |

530 |

16 |

|

Self-organization |

Web of science |

36 |

3 |

Scopus |

189 |

13 |

|

Civic initiatives |

Web of science |

22 |

5 |

Scopus |

106 |

12 |

|

Self-reliance |

Web of science |

40 |

3 |

Scopus |

269 |

2 |

|

Community self-management |

Web of science |

5 |

2 |

Scopus |

34 |

0 |

|

Social enterprise |

Web of science |

303 |

24 |

Scopus |

1139 |

28 |

|

Social entrepreneurship |

Web of science |

114 |

2 |

Scopus |

20 |

2 |

|

Grassroots initiatives |

Web of science |

46 |

5 |

Scopus |

115 |

20 |

|

Community-based coalitions |

Web of science |

12 |

9 |

Scopus |

48 |

8 |

|

Civic entrepreneurship |

Web of science |

6 |

0 |

Scopus |

4 |

0 |

|

Do-it-yourself |

Web of science |

8 |

0 |

Scopus |

85 |

3 |

|

Total |

3254 |

177 |

Eligibility Criteria

Records identified in our searches were included if they met all of the following eligibility criteria:

Topic of citizen initiatives: records should contain the words ‘‘citizen initiatives’’ or the following related concepts: ‘‘civic initiatives’’ or ‘‘self-reliance’’ or ‘‘social enterprises’’ or ‘‘social entrepreneurship’’ or ‘‘self-organization’’ or ‘‘community self-management’’ or ‘‘civic entrepreneurship’’ or ‘‘grassroots initiatives’’ or community-based coalitions’’ or ‘‘do-it-yourself.’’

General Eligibility Criteria

Language: only studies published in English were included.

Publication status: only international peer-reviewed journal articles in the field of social sciences (e.g., public administration, urban studies, and sociology) were included in the review.

Study design: only empirical records were included in the review, as we are interested in the outcomes of citizen initiatives and in the effects of stimulating or hampering factors. All kind of research designs were eligible (e.g., case studies, survey research, and ethnographic studies).

Year of publication: we selected records published in the period between 1990 and January 4, 2016 (date of last search). The year of 1990 was chosen because it marked the beginning of a changing relationship between citizens and their governments as a result of an increase in non-institutionalized participation of citizens (Klingemann and Fuchs Reference Klingemann and Fuchs1995). Furthermore, the now frequently used concept of social enterprise emerged around 1990 as an analytical concept for a wide variety of organizational forms, such as cooperatives and community enterprises, in the USA and mainland Europe, also addressing initiatives of citizens aimed at self-organizing public goods or services for their community (Defourny and Nyssens Reference Defourny and Nyssens2010; Teasdale Reference Teasdale2012).

Specific Eligibility Criteria

Type of study and participants: studies should deal with non-profit, bottom-up, and voluntary activities of citizens aimed at self-organizing public goods or services for their community. Whether or not formally organized, citizens (and not governmental or private organizations) are the participants and therefore organize these activities themselves, but they are likely to link to various public and private organizations. If formalized, the initiatives can differ in their organizational structure (e.g., being a cooperative or community enterprise), as well as in their workforce (having only volunteers or a combination of volunteers and paid staff). However, all initiatives should have the same theoretical characteristics of being a (formal/informal) form of self-organization, providing public services or goods to a community, being in control of internal decision-making and not focused on private profitmaking nor working solely with paid staff (e.g., Bailey Reference Bailey2012; Llano-Arias Reference Llano-Arias2015; Ornetzeder and Rohracher Reference Ornetzeder and Rohracher2013). These characteristics set citizen initiatives apart from activities of professionalized non-profit organizations in the traditional third sector with paid workers and no link to voluntary citizen participation (cf. Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk Reference Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk2016).

After screening the records on general eligibility criteria, and duplicates, 3254 articles were remaining (see Fig. 1). One researcher screened each record, checking whether it met the (specific) eligibility criteria, in order to determine the list of records for full reading. This process contained an intensive and accurate screening of title, topic, abstract, and if needed full articles. There were three main reasons for the significant decline in records. The first reason concerns the articles related to the term ‘‘social enterprise.’’ The number of hits for social enterprise was 1442, which takes a share of 44% of the total of 3254 records, and after screening on eligibility criteria, 52 records remained (see also Table 1), resulting in a decline of 96% for this search term. The reason for this decline is that, even though we performed the search with parenthesis, the databases included a high number of records that referred to ‘‘social’’ and ‘‘enterprise’’ as independent terms. Therefore, many studies did not meet our criterion about the type of study and participants, because they focused for instance on for-profit enterprises or social topics without any link to citizen initiatives (e.g., market reforms and gender inequality). The second main reason for excluding articles is that there were records included that did not entirely match our focus. For instance, articles in which citizens did not have a leading role after all, but the abstracts and titles suggested otherwise. For example, government-led initiatives in which citizens participated with little or no control on internal decision-making. Records that did not meet the general eligibility criteria after all caused the third and final main reason for exclusion. Some articles had a theoretical orientation without empirical data, and other records were not peer reviewed, but for instance, book reviews and others turned out to be duplicates.

Finally, all researchers participated in full reading and used an inductive coding approach (with back-and-forth coding) to identify factors, outcomes, definitions, and theories (see “Appendix 1” for more information about this coding process and our checks on reliability and validity).

Table 1 shows the number of hits for each search term we used in the review (see also “Appendix 1” for more information about these terms).

Results of Systematic Review

Descriptive Characteristics of the Studies

Before answering our research question, we present some important descriptive results.

Journals

The studies are published in 59 different journals presenting not only public administration journals (e.g., Public Administration, Public Administration Review, Public Policy and Administration), but also a broad range of other social sciences journals (e.g., VOLUNTAS, American Journal of Community Psychology and International Journal of Urban and Regional Research), showing a multidisciplinary approach of the topic. Many studies were found in Community Development Journal (n = 6; 6.7%), Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly (n = 5; 5.6%), Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy (n = 4; 4.5%), and Urban Studies (n = 4; 4.5%).

Geographic Location

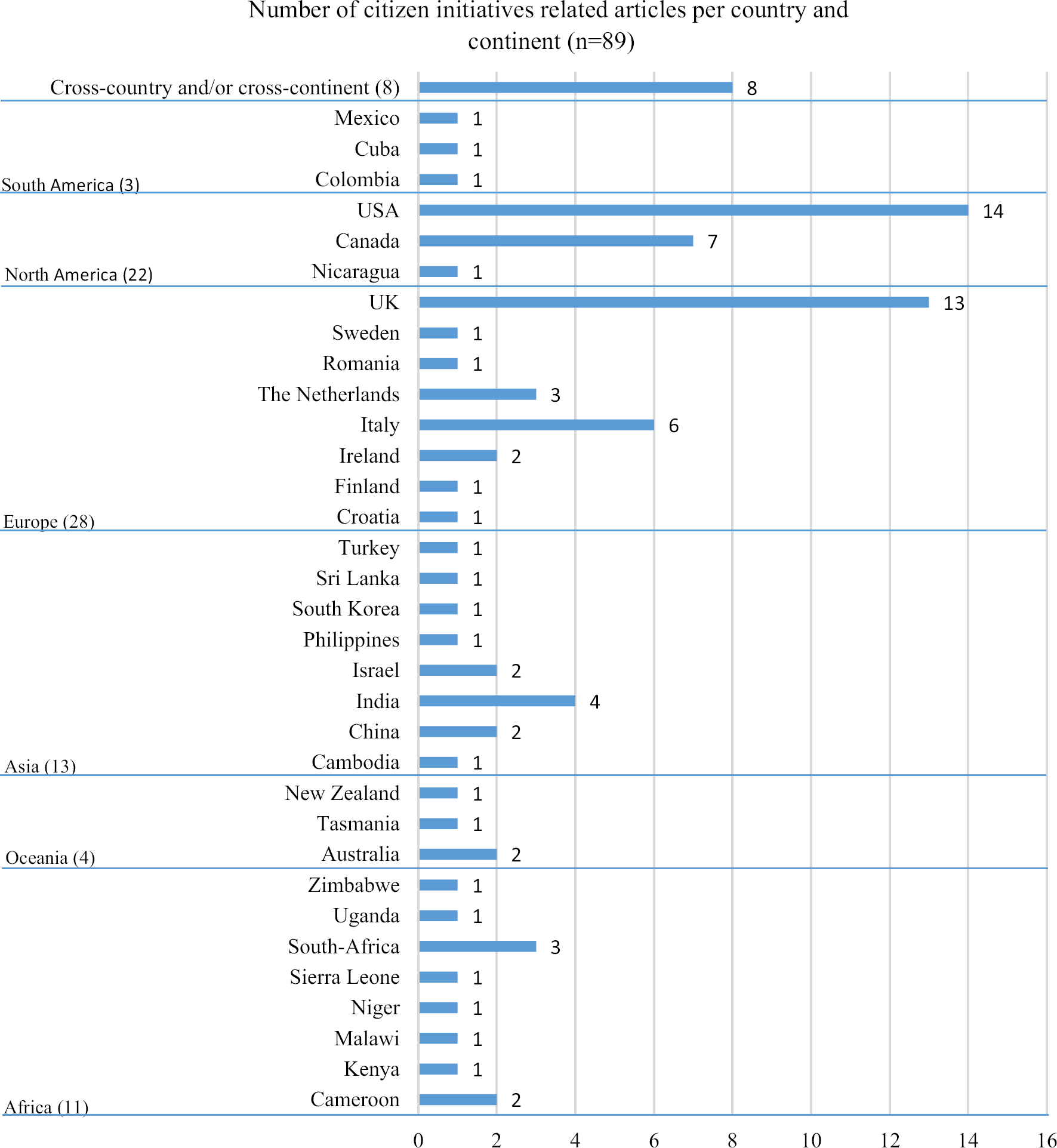

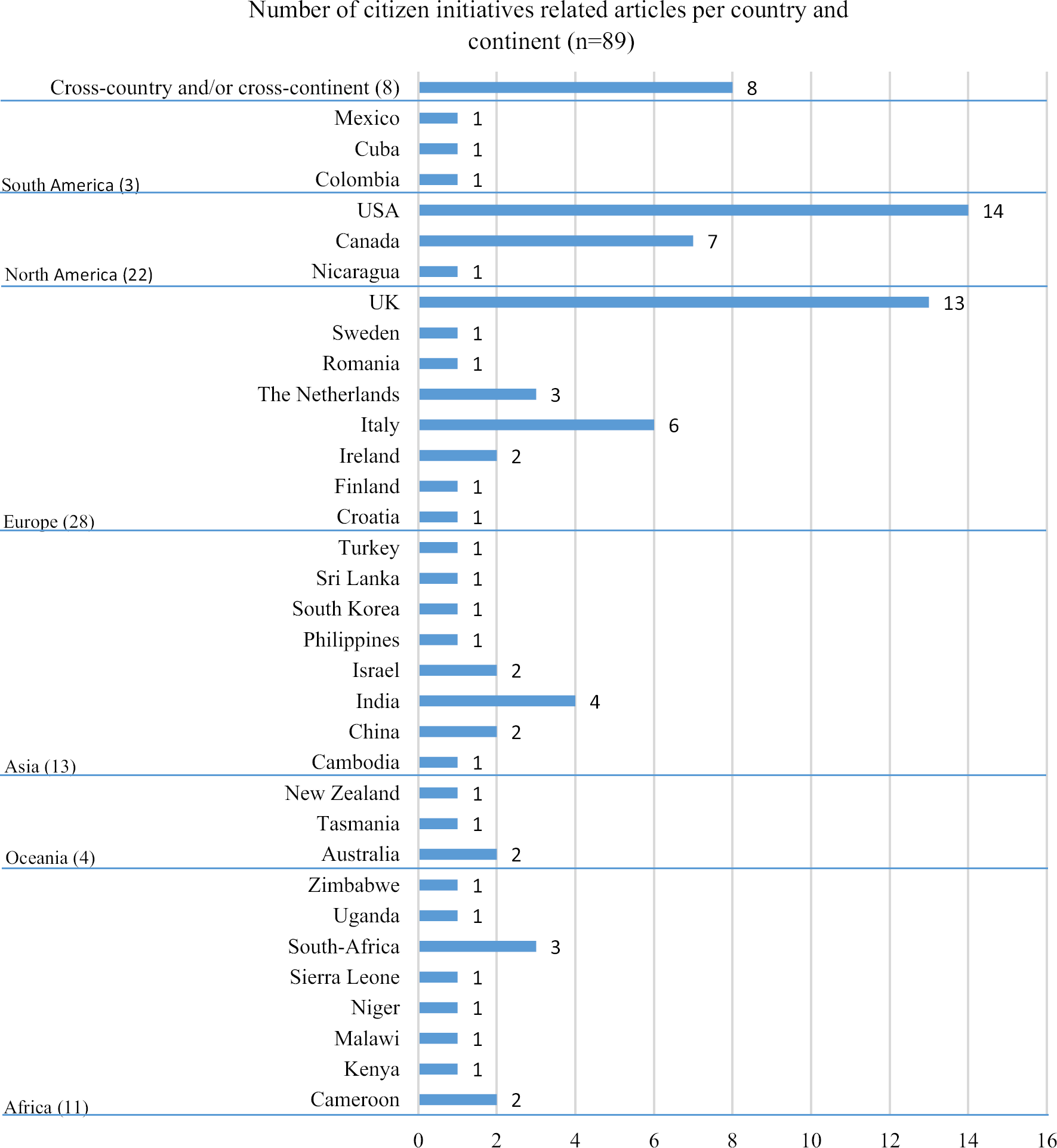

As Fig. 2 shows, a more Western perspective is central when studying citizen initiatives, though citizen initiatives are also studied in Africa, Asia (including the Middle East), and South-America.

Fig. 2 Number of citizen initiatives-related articles per country and continent (n = 89)

Another finding in Fig. 2 is that 91 percent of the articles (n = 81) was conducted in a single country, indicating a lack of cross-country and cross-continent comparisons.

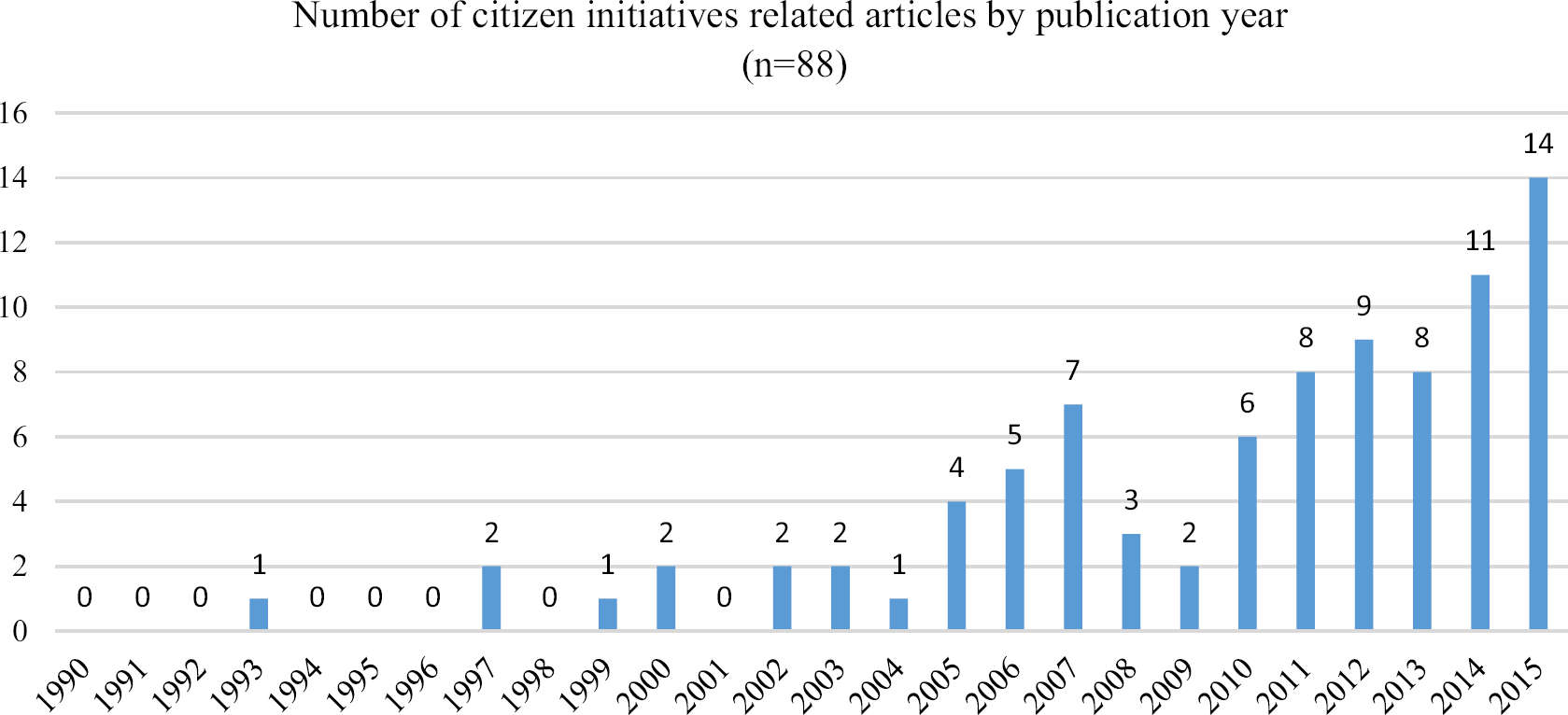

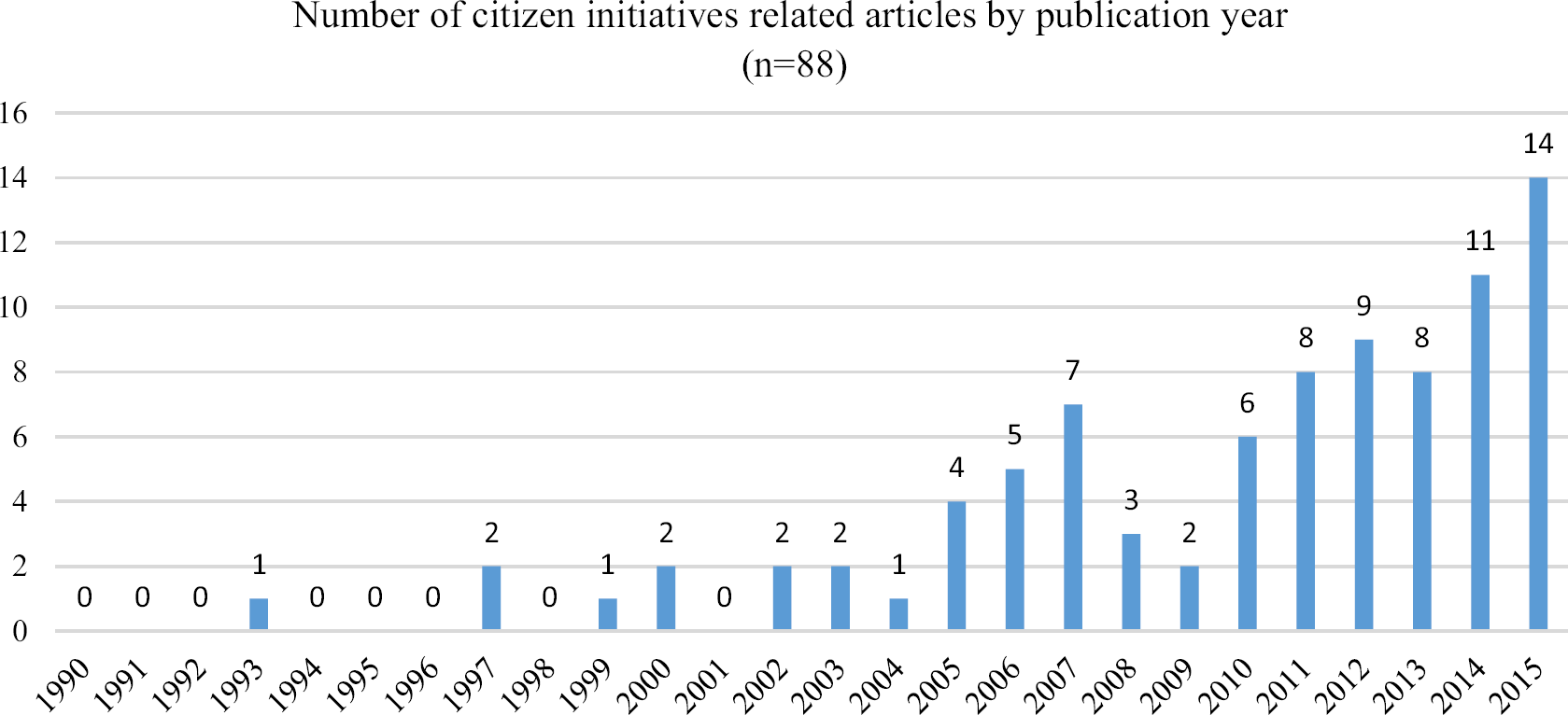

Publication Years

Figure 3 presents the number of articles for the selected period between 1990 and January 2016. As expected, the figure shows a net increase in the number of articles during this period, especially during the last decade (from 2010 onwards). Societal developments, such as government retrenchment and citizen activation policies, like UK’s Localism Act of 2011, probably contributed to this recent growth in academic attention for citizen initiatives (cf. Brandsen et al. Reference Brandsen, Trommel and Verschuere2017; Eriksson Reference Eriksson2012).

Fig. 3 Records by publication year (n = 88). Note: Although the timeframe for the review contains the period between 1990 and January 4, 2016, we excluded 2016 due to the short period in 2016, which does not provide a good representation of that year (i.e., one article was published in 2016)

Research Designs of the Studies

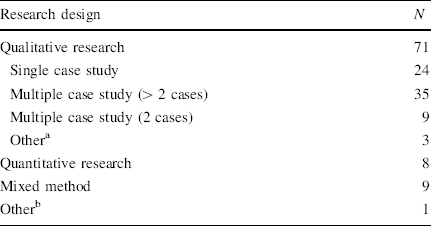

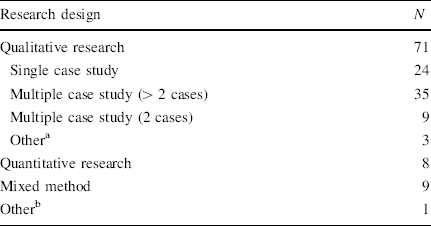

Table 2 shows that the field of citizen initiatives is dominated by a qualitative research strategy (n = 71; 79.8%). The (qualitative) studies particularly used interviews, document analysis, and observations as methods for data collection.

Table 2 Research designs of the studies (n = 89)

Research design |

N |

|---|---|

Qualitative research |

71 |

Single case study |

24 |

Multiple case study (> 2 cases) |

35 |

Multiple case study (2 cases) |

9 |

Othera |

3 |

Quantitative research |

8 |

Mixed method |

9 |

Otherb |

1 |

aOther qualitative research designs use desk research

bOne study used Q methodology, which we coded as other

A quantitative research strategy was used in eight studies (9%). Remarkably, the studies on citizen initiatives did not use experimental designs. Furthermore, few studies (n = 9; 10.1%) used both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection, such as surveys, interviews, observations, and focus group discussions.

Findings on Citizen Initiatives: What Do We Know?

In the following sections, we present and discuss the results of our systematic review concerning the characteristics of citizen initiatives, the theoretical approaches, the outcomes, the factors, and relationships between factors and outcomes.

Characteristics of Citizen Initiatives

Sectors of the Citizen Initiatives

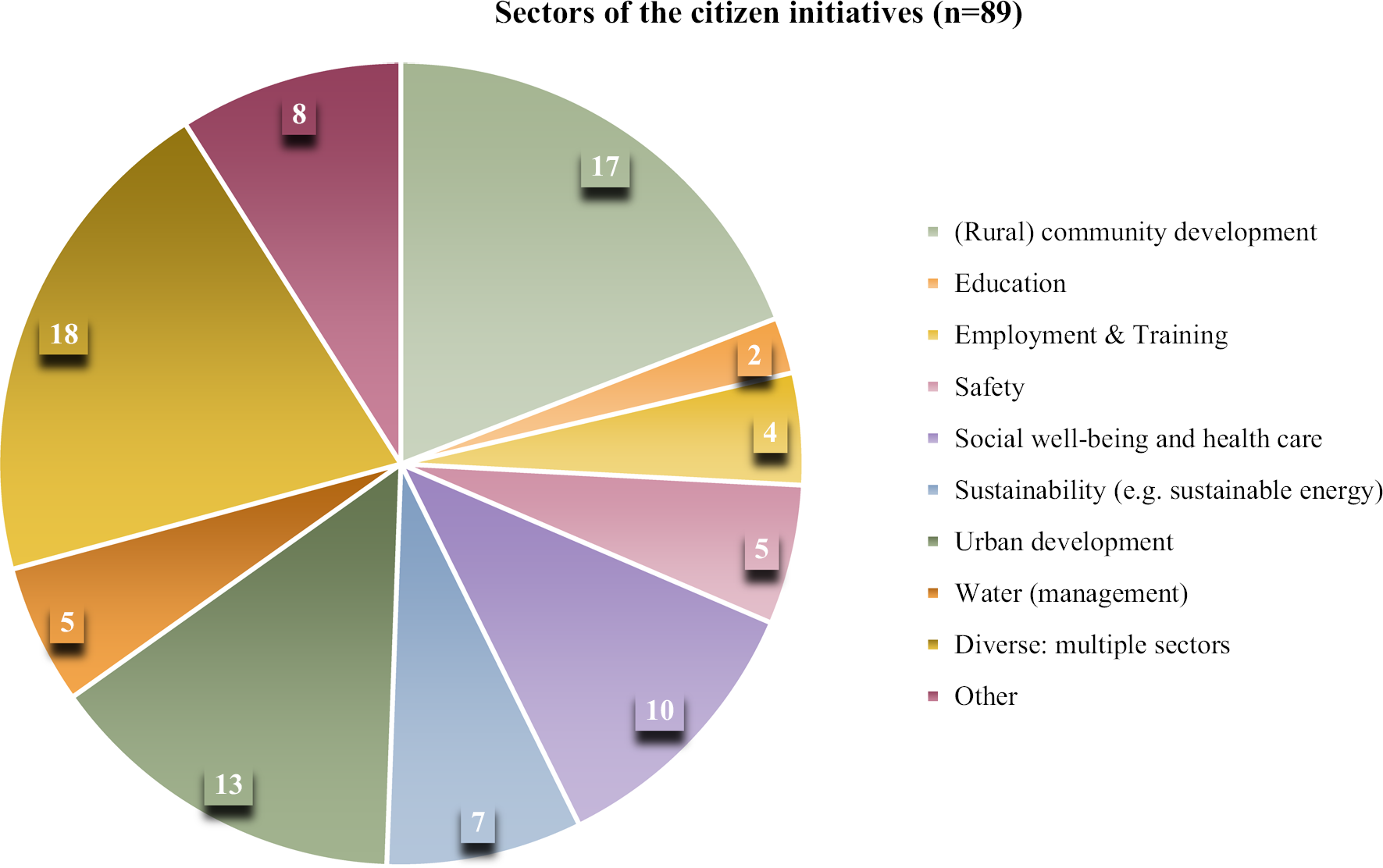

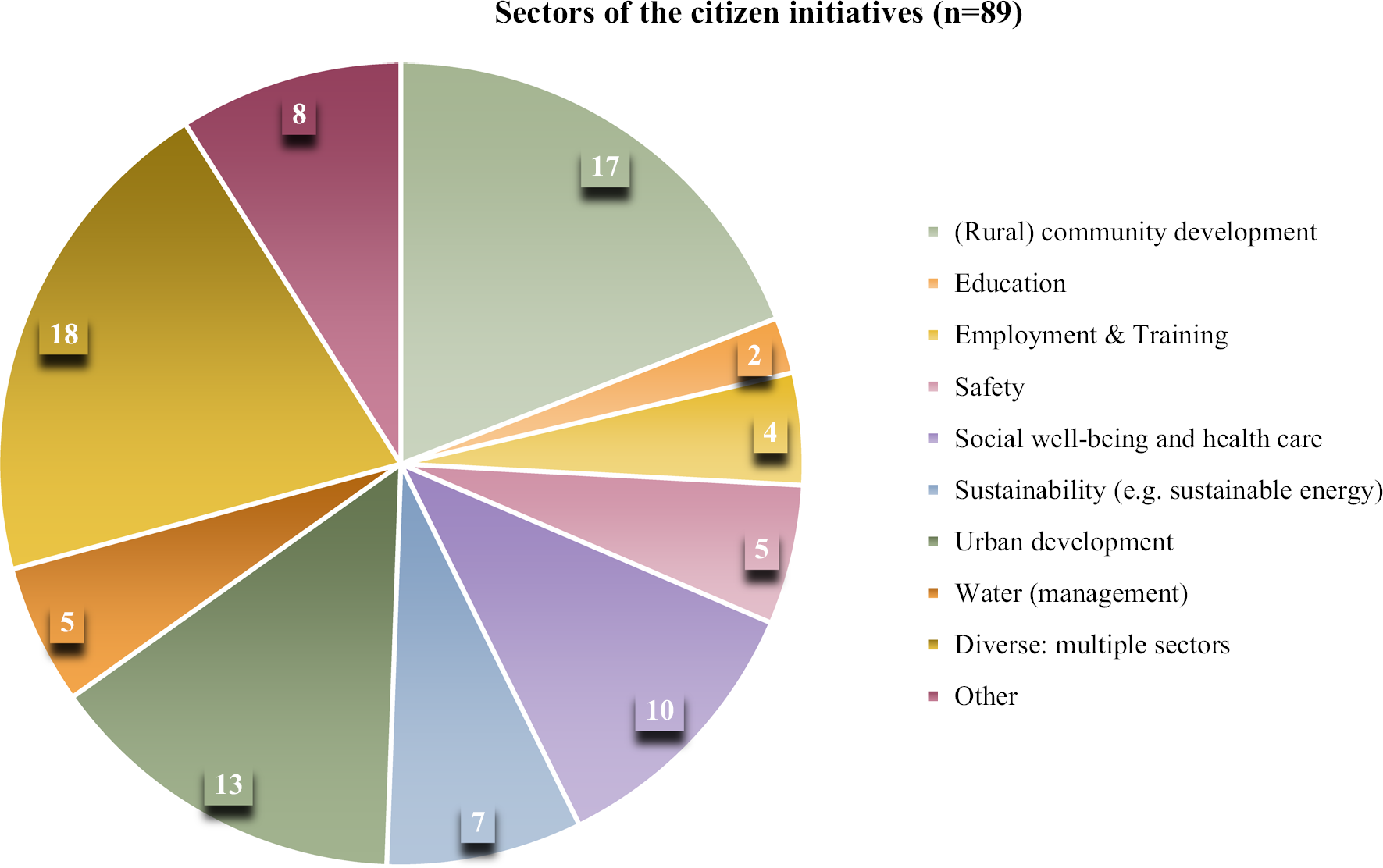

Figure 4 presents the sectors in which the citizen initiatives operate. Most records studied initiatives operating in one sector (79.8%). The figure also shows diversity among the sectors, yet three are frequently used: community development about community building, community conservation, and living conditions in the neighborhood (n = 17; 19.1%), urban development about urban spaces, urban planning, and urban regeneration (n = 13; 14.6%), and social well-being and health care (n = 10; 11.2%). A further observation is that although many records study citizen initiatives from multiple sectors (n = 18; 20.2%), most studies did not compare the sectors. They used the cases for illustrative purposes, indicating a lack of cross-sector research.

Fig. 4 Sectors of the citizen initiatives (n = 89)

Definitions

For our review, we used different related terms, which makes it interesting to compare their use across countries and could provide valuable insights for future comparative research.

Our first observation is that enterprise related concepts are mostly used in Anglo-Saxon countries (e.g., for social enterprise: 65.4%). One explanation is that Anglo-Saxon countries have from their (neo) liberal tradition a more business and market orientation and therefore approach citizen initiatives as (social) enterprises. Furthermore, citizen initiatives in South-America and Africa use predominantly community-related concepts, like community initiatives, community aqueduct associations, and community groups. In North America (Canada and the USA) and Europe (especially the UK), community terms are also present, as the second most used concept. For the term grassroots, half of the studies come from Anglo-Saxon countries (four of the eight studies found). The other half consists of African citizen initiatives (two studies) and cross-continental studies. In Asia, various concepts are used, ranging from community terms such as community-based initiative in India to voluntary specific terms, like non-profit organizations in China. Finally, in non-Anglo-Saxon parts of Europe, we can see different concepts as well, but it seems that social cooperatives are common in Italy and citizen initiative and self-organization are used in the Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland.

Next, we looked at the definitions used to describe the many concepts. A first observation is that the topic of citizen initiatives involves a search for a clear definition. Some studies (29 percent; n = 23) did not specify their concepts. One possible explanation might be the cultural familiarity with self-organization in countries as the USA, resulting in self-evidence when it comes to conceptualizing. The other 55 articles (70.5%) did define and discuss their central concepts. Based on the extensive definitions, we provide the following five central characteristics of citizen initiatives (e.g., Bailey Reference Bailey2012; Llano-Arias Reference Llano-Arias2015; Ornetzeder and Rohracher Reference Ornetzeder and Rohracher2013; Thomas Reference Thomas2004):

1. Citizen initiatives are community-based and often locally oriented, which means that

a. local residents, often collectives of residents, are the (current) driving force behind the initiatives;

b. they mobilize volunteers from within the community, and

c. they focus on community needs.

2. Citizen initiatives provide and maintain an alternative form of traditional governmental public services, facilities, and/or goods themselves, such as water distribution, education and training, and residential care;

3. Citizen initiatives strive for autonomy, ownership, and control regarding internal decision-making;

4. Citizen initiatives are often linked to formal institutions, such as local authority, governmental agencies, and NGOs, especially for facilitation and public funding;

5. Citizen initiatives often develop their own business model to increase financial stability, which helps them continue their activities, but they are not focused on private profitmaking (i.e., profits are invested back into the local community).

Theoretical Approaches

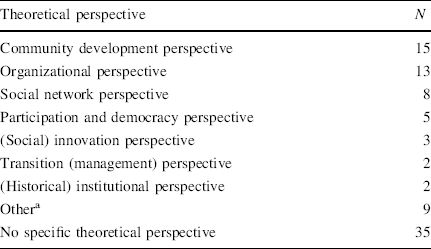

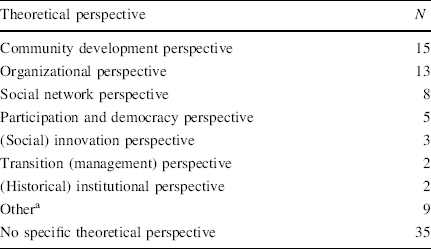

Following an inductive approach, as described in the appendix, we looked at the theoretical framework of the studies and categorized them into theoretical approaches (see Table 3). Our first observation is that some studies use a combination of different bodies of the literature (n = 35; 38%). This was especially the case in qualitative studies with inductive approaches or explorative purposes (e.g., Anguelovski Reference Anguelovski2015). The other studies applied concepts relating to one of the four central approaches we have identified.

Table 3 Theoretical perspectives in the studies

Theoretical perspective |

N |

|---|---|

Community development perspective |

15 |

Organizational perspective |

13 |

Social network perspective |

8 |

Participation and democracy perspective |

5 |

(Social) innovation perspective |

3 |

Transition (management) perspective |

2 |

(Historical) institutional perspective |

2 |

Othera |

9 |

No specific theoretical perspective |

35 |

aOther: for example, neo-liberalism and symbolic convergence theory. N = 92 (100%)—one study falls in two and one study in three categories

The studies that applied a community development approach, elaborated citizen initiatives in terms of capacity development, leadership, empowerment, and supporting institutions (e.g., Fonchingong and Ngwa Reference Fonchingong and Ngwa2005). For instance, Kelly and Caputo (Reference Kelly and Caputo2006) defined community capacity as ‘‘characteristics of communities that affect their ability to identify, mobilize, and address social and public health problems’’ (Poole as quoted in Kelly and Caputo Reference Kelly and Caputo2006: 235). The authors examined community capacity building as an important factor for community development.

Additionally, the organization perspective describes the literature on organizational capacity including topics such as resources, organizational form, and professionalization (e.g., Bess et al. Reference Bess, Perkins, Cooper and Jones2011). As an illustration, Herranz et al. (Reference Herranz, Council and Mckay2011) build on and extend Moore’s three-part framework (as quoted in Herranz et al. Reference Herranz, Council and Mckay2011) that identifies values-based differences in sources of revenue among for-profit, non-profit, and governmental organizations.

In addition, the social network approach covers theories on social capital, social cohesion, and social interactions to examine how successful outcomes of citizen initiatives come into being. The studies often used Putnam’s definition of social capital and the distinction between bonding, bridging, and linking social capital (e.g., Newman Reference Newman2007; Smets Reference Smets2011). Smets for instance discusses the difference between social cohesion and social capital, with the latter being less holistic and general and more focused on the individual and group level.

Furthermore, the fourth perspective discusses self-organization in light of participation and democracy, discussing new ways of citizen participation, the consequences for (representational) democracy and democratic aspects of citizen initiatives, such as representation and legitimacy issues. Authors such as Hirshman, Lowndes, and Pitkin were discussed and used in the analyses (e.g., Llano-Arias Reference Llano-Arias2015). For instance, Guo and Zhang (Reference Guo and Zhang2013) applied the five-dimensional representational framework, a measure for democratic legitimacy of Guo and Musso (as quoted in Guo and Zhang Reference Guo and Zhang2013), which has its point of departure in classic works, such as Pitkin’s Concept of Representation, and consists of formal representation, descriptive representation, participatory representation, substantive representation, and symbolic representation.

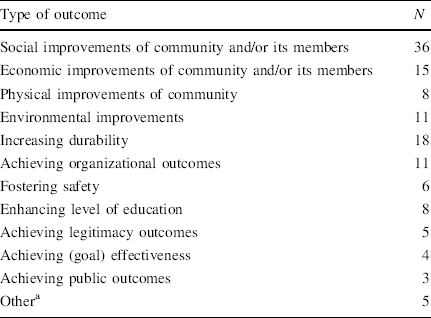

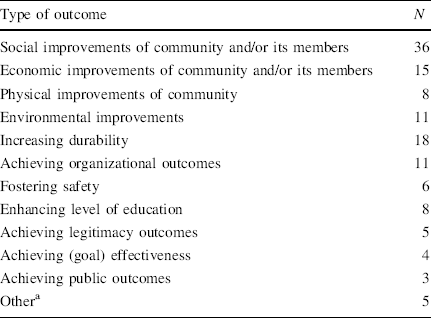

Outcomes of Citizen Initiatives

With outcomes, we refer to the results or achievements of citizen initiatives. A majority of the studies report specific outcomes of citizen initiatives (n = 63; 70.8%). Table 4 presents an overview of the types of outcomes identified in the studies.

Table 4 Outcomes of citizen initiatives

Type of outcome |

N |

|---|---|

Social improvements of community and/or its members |

36 |

Economic improvements of community and/or its members |

15 |

Physical improvements of community |

8 |

Environmental improvements |

11 |

Increasing durability |

18 |

Achieving organizational outcomes |

11 |

Fostering safety |

6 |

Enhancing level of education |

8 |

Achieving legitimacy outcomes |

5 |

Achieving (goal) effectiveness |

4 |

Achieving public outcomes |

3 |

Othera |

5 |

Total: N = 130 (100%)—most studies identified more than one outcome

aOther: for example, health improvements (Aladuwaka and Momsen Reference Aladuwaka and Momsen2010)

First, most studies described social improvements of the community and/or its members as an outcome of citizen initiatives (27.7%). This outcome includes fostering relational aspects in communities or among community actors, and/or empowering certain groups. Examples of citizen initiatives that create social outcomes are ‘‘Mohalla Committees’’ restoring peace among conflicting groups in India (Nilesh Reference Nilesh2011) and ‘‘Vishaka Women’s Society’’ aimed at fostering women’s ability to organize and bring change in Sri Lanka (Aladuwaka and Momsen Reference Aladuwaka and Momsen2010).

The second most described outcome (13.8%) is the durability or long-term viability of citizen initiatives (e.g., Fonchingong Reference Fonchingong2005; Ornetzeder and Rohracher Reference Ornetzeder and Rohracher2013). Since citizen initiatives become an alternative for governmental public services, durability becomes an important outcome to ensure the availability of these services for citizens.

Next, economic improvements of the community (members) are the third most studied outcome (11.5%) and describe especially one of these three economic indicators: creation of new jobs, reducing poverty, and organizing income-generating activities for community members (e.g., Hill et al. Reference Hill, Nel and Illgner2007), created by initiatives like ‘‘Ganados del Valle,’’ a sustainable, community-based micro-enterprise in the USA (Vargas Reference Vargas2000).

The other identified outcomes in Table 4 are:

• Environmental outcomes, especially about initiatives focused on improving environmental quality and livability, such as community enterprises aimed at regeneration of the neighborhood in the UK (Bailey Reference Bailey2012);

• Organizational outcomes, mainly about financial results of the initiatives, including indicators for efficiency and production costs (e.g., Liu et al. Reference Liu, Takeda and Ko2014);

• Physical improvements of the community about initiatives aimed at community conservation and area development, such as citizen-led snowmobile associations establishing snowmobile trails in Sweden (e.g., Anttila and Stern Reference Anttila and Stern2005);

• Safety outcomes about decreasing different kinds of danger, such as fire hazard and crime (e.g., Everett and Fuller Reference Everett and Fuller2011);

• Enhancing educational levels of community members by providing education and training for especially children, women, and youth, such as providing educational services to refugee children in Uganda by a refugee-initiated community-based organization (Dryden-Peterson Reference Dryden-Peterson2006);

• Legitimacy outcomes, especially about the degree of compliance with norms and laws, and about being recognized as important by the community (e.g., Bagnoli and Megali Reference Bagnoli and Megali2011);

• Public outcomes, about the achievement of public institutions-related outcomes, such as improving trust among the police and residents (e.g., Nilesh Reference Nilesh2011);

• Increasing effectiveness, especially about achieving defined objectives (e.g., Ramirez Reference Ramirez2005).

The findings show that citizen initiatives in their provision of public services are concerned with both achieving organizational performance and creating public value. Therefore, in our process of coding, we categorized the outcomes based on two levels of analysis: external and internal levels. The external level refers to outcomes or results of citizen initiatives that are observable outside the initiative, produced for external actors such as community members, target groups, and public institutions. In other words, external outcomes concern the contribution of citizen initiatives to the common good (social, economic, physical, environmental, safety, educational, and public outcomes). The internal level refers to outcomes that citizen initiatives realize as organizations (durability, legitimacy outcomes, and organizational outcomes). Specifically, internal outcomes concern the capacity of initiatives to facilitate their activities, showing outcomes regarding the creation, management, and viability of citizen initiatives. In this categorical distinction, effectivity overlaps with external outcomes.

Factors Influencing Outcomes of Citizen Initiatives

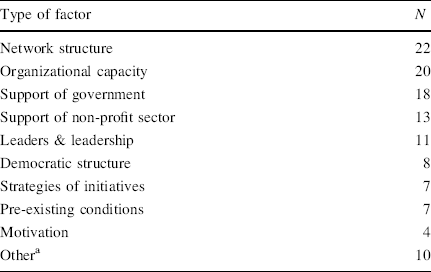

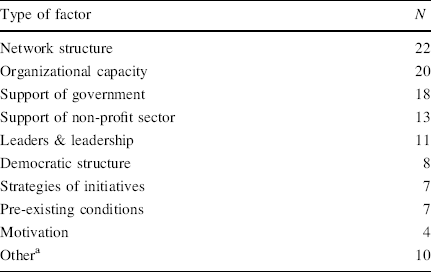

Besides the outcomes, we looked at factors that strengthen or hamper these outcomes. More than half of the 89 studies mentioned factors (n = 51; 57.3%), which means that 81 percent of the studies that identified outcomes (n = 63) distinguished explanatory factors as well. The factors were mentioned across different studies as important to achieve good outcomes. We can therefore present a valuable overview of antecedents of citizen initiatives’ outcomes (see Table 5).

Table 5 Factors influencing outcomes of citizen initiatives

Type of factor |

N |

|---|---|

Network structure |

22 |

Organizational capacity |

20 |

Support of government |

18 |

Support of non-profit sector |

13 |

Leaders & leadership |

11 |

Democratic structure |

8 |

Strategies of initiatives |

7 |

Pre-existing conditions |

7 |

Motivation |

4 |

Othera |

10 |

Total: N = 120 (100%)—most studies identified more than one factor

aTwo examples are skills development and customer satisfaction (Cheng Reference Cheng2015; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Takeda and Ko2014)

The three most mentioned factors are: network structure about the importance for a self-organization to have a diverse network (e.g., Newman et al. Reference Newman, Waldron, Dale and Carriere2008); organizational capacity referring to matters of the internal infrastructure and financial health of citizen initiatives (e.g., Bess et al. Reference Bess, Perkins, Cooper and Jones2011) and support of government about the ways in which governments (e.g., about the institutional context and attitudes of public representatives) can contribute to or impede the outcomes of citizen initiatives (e.g., Korosec and Berman Reference Korosec and Berman2006).

The other identified factors in Table 5 are:

• Support of non-profit institutions outside governments and commercial businesses; NGOs are a prime example. Studies mention financial and non-financial support, namely funding, technical assistance, advisory services, and training, as types of support non-profit institutions (can) give so that citizen initiatives can conduct their work. This factor especially increases the durability of citizen initiatives (e.g., Hill et al. Reference Hill, Nel and Illgner2007);

• Leaders and leadership, about the characteristics, qualities, and activities of individuals who form and/or manage the citizen initiatives (e.g., Van Meerkerk et al. Reference Van Meerkerk, Boonstra and Edelenbos2013);

• Democratic structure, about the nature of representation, the source of legitimacy, and transparency within the initiatives. Examples are the use of participatory decision-making processes for member participation and representation, the consultation of residents, and sharing of information (e.g., Torri and Martinez Reference Torri and Martinez2011);

• Strategies of initiatives, about activities and strategies used to mobilize people and resources, and to interact with external actors. Examples of strategies mentioned are coalition development by connecting and mobilizing civil society organizations, and the adaptation of an entrepreneurial strategic orientation, for example, by having a focused idea for a product or service with market potential (e.g., Anguelovski Reference Anguelovski2015);

• Pre-existing conditions, about structural elements that produce regular and predictable patterns in behavior and cannot be directly influenced by local actors, such as national traditions, and existing socio-economic institutions like the caste system (e.g., Ornetzeder and Rohracher Reference Ornetzeder and Rohracher2013);

• Motivation stresses the commitment of leaders and other involved individuals to hard work and volunteering (e.g., Healey Reference Healey2015).

Building on What We Know: A Conceptual Framework Explaining Outcomes of Citizen Initiatives

After identifying factors and outcomes of citizen initiatives, we were interested in the question how these outcomes are affected by the factors. An important first observation is that the studies fall short in this respect. Many studies do not go beyond mentioning and briefly describing the relations, lacking (theory-based) operationalization of both factors (15 of 51 articles (29.4%) presented both conceptualizing definitions and operationalizing indicators) and outcomes (15 of 63 (23.8%) provided both conceptualization and operationalization), as well as mechanisms that actually explain the relationships found in the data. A possible cause is the descriptive and inductive nature of many of the qualitative (case) studies in the literature review.

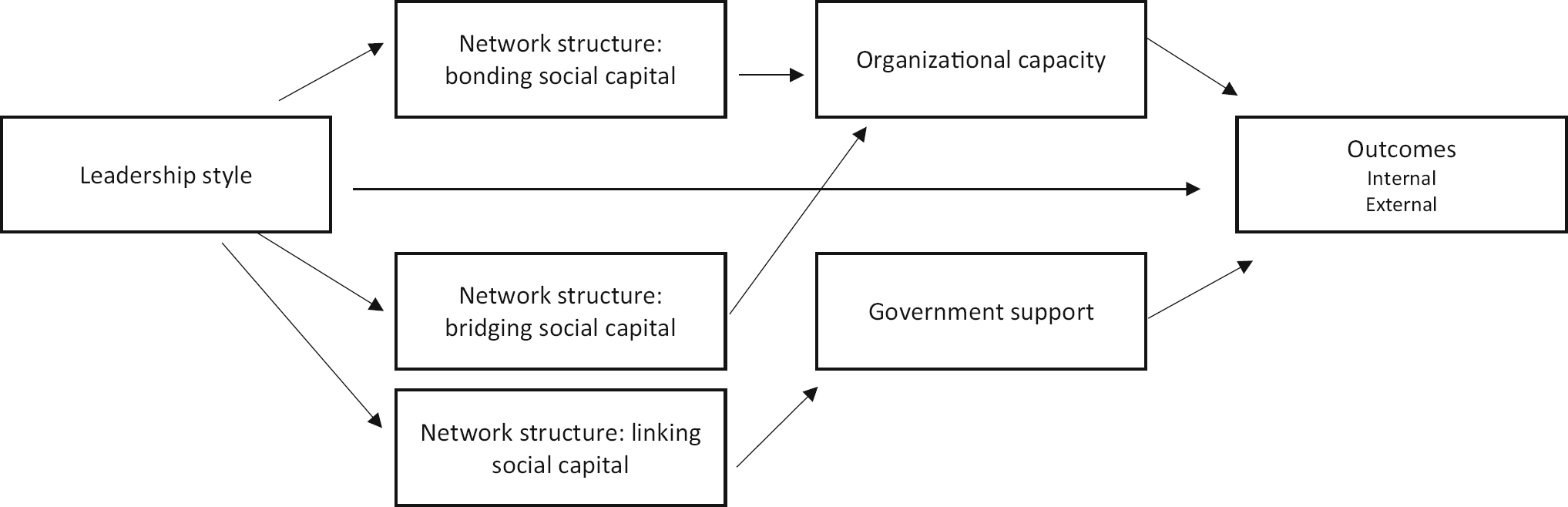

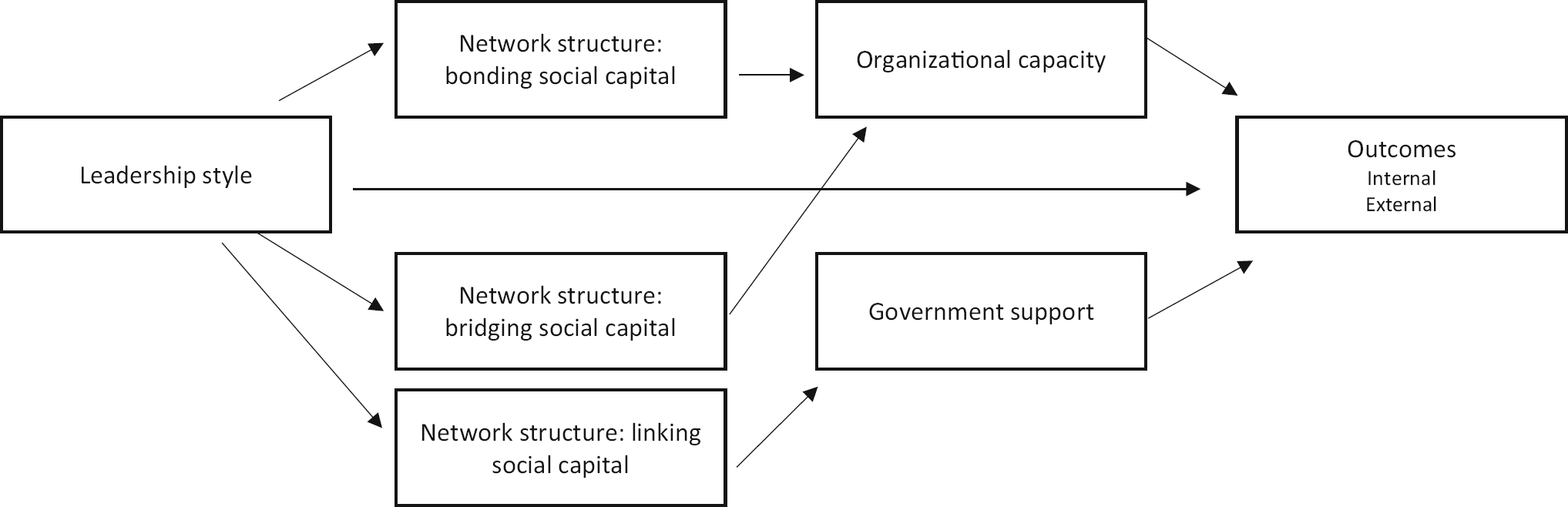

Despite these limitations, the studies do present valuable theory-based empirical insights for the relationships between outcomes and four factors: network structure, government support, organizational capacity, and leadership. Our review reveals that the identified factors are often depicted as independent variables, whereas one would expect more interrelationships between the factors to better reflect the reality of citizen initiatives. We therefore propose a more complex model to conceptualize relationships between outcomes and relevant antecedents (see Fig. 5) by building on the studies in this review and, in the case of leadership, by using the wider literature to enhance our understanding of this factor and of the relationships with the other factors. Figure 5 displays direct relationships, but we want to emphasize that we do not assume causality beforehand, as that should be tested in future empirical research. Moreover, Fig. 5 is the result of the systematic review, on how the records view relationships with factors and outcomes of citizen initiatives. We argue that our integrated model can enhance sophisticated analyses with a greater focus on mechanisms that explain why outcomes are hampered or strengthened by the identified factors.

Fig. 5 A conceptual framework explaining the outcomes of citizen initiatives

Our research framework as depicted in Fig. 5 presents a direct relationship between organizational capacity and the outcomes of citizen initiatives. One of the studies that analyzed this relationship is that of Han et al. (Reference Han, Choi and Chung2015), which demonstrated positive relationships between characteristics of organizational capacity (mission, human resources management, infrastructure, and management capacity) and outcomes. The mechanisms behind these relationships were based on organizational theory of social enterprises, which assumes that by building organizational capacity, social enterprises can develop ‘‘successful programs on a larger scale and thereby maximize their impact on social development (Han et al. Reference Han, Choi and Chung2015:71).’’ Related to the aspect of human resources, the size of the staff is an important aspect of the organizational capacity for citizen initiatives. Initiatives often operate on a voluntary basis (cf. Bailey Reference Bailey2012; Healey Reference Healey2015), so having sufficient committed volunteers is important to be up and running and to create outcomes for the community. Furthermore, it can be hard for an organization to function without sufficient financial resources, even for non-profit organizations. Citizen initiatives can struggle to obtain adequate revenue sources for their operational costs (Bailey Reference Bailey2012), which might endanger internal outcomes, such as durability, or might impede possibilities for up-scaling. Overall, the studies show that building organizational capacity can enhance outcomes of citizen initiatives (cf. Ornetzeder and Rohracher Reference Ornetzeder and Rohracher2013).

A second direct relationship with outcomes is constituted by government support. This support takes various forms and has mainly positive effects on outcomes. The following types of support were mentioned (e.g., Fonchingong Reference Fonchingong2005; Korosec and Berman Reference Korosec and Berman2006; Llano-Arias Reference Llano-Arias2015):

• Enhancing a facilitative policy and political institutional environment;

• Providing a facilitative legal framework or adjusting legal restrictions, obstacles, and regulations;

• Provide advisory (and technical) services;

• Supporting through financial means, such as subsidies;

• Facilitation to help with coordination and implementation efforts;

• Playing an active role by cooperating on for instance the realization of shared goals.

The studies show that these forms of support positively affect outcomes. The overall (implicit) mechanism for these relations seems to be that governmental support helps in acquiring resources, which in turn improve outcomes, such as durability due to increasing opportunities for consolidation and growth (e.g., Fonchingong Reference Fonchingong2005). However, negative effects of governmental support were also mentioned due to different gradations of support. If support includes an active and open attitude or strategy toward citizen self-organization, ranging from facilitation to cooperation, positive effects are reported. Even less active, but still supporting attitudes by tolerating and encouraging citizen initiatives (e.g., in case a government lacks resources), could be helpful (e.g., Aladuwaka and Momsen Reference Aladuwaka and Momsen2010; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Nel and Illgner2007; Johnson and Young Reference Johnson and Young1997). Negative effects arise if governments become overactive, demanding ‘‘their own programs or services rather than working collaboratively with cooperatives’’ (Gonzales Reference Gonzales2010). Furthermore, support of local government in the form of funding can negatively influence outcomes, because of ‘‘misaligned output timeframes, administration demands, and local competition’’ (Creamer Reference Creamer2015). Thus, government support seems to come with a price tag, with red tape and exhaustion being examples of negative side-effects that can impede the occurrence of positive outcomes. Therefore, a first important question that needs further examination is how does government support influence outcomes of citizen initiatives? Two other important questions are: how do different types of government support influence outcomes of citizen initiatives, and what is the role of possible negative consequences of receiving government support?

Next to government support, Fig. 5 shows a mediating role for the factor network structure. The studies make a distinction in bonding, bridging, and linking social capital and mention that it is important for initiatives to invest in all three forms in order to achieve good outcomes (e.g., Newman Reference Newman2007; Bertotti et al. Reference Bertotti, Harden, Renton and Sheridan2012). To begin with bonding social capital, the studies discuss the importance of having a core group of members within the initiative. These members all know each other and are connected through strong trusting and frequently maintained relationships (cf. Newman Reference Newman2007). Such a core group is important to build and maintain organizational capacity, because it functions as the back-office of an initiative, committed to organize activities, and mobilize volunteers and other relevant resources that help in achieving organizational and community outcomes. Overdependence on one leader has shown to be a common pitfall of engaged community leaders, and a core group helps to prevent an unwanted collapse of the self-organization when leaders decide to leave the initiative (e.g., Torri and Martinez Reference Torri and Martinez2011).

In addition to relationships within the initiative, the studies show the importance of ties that connect the initiative with outside actors. As Newman (Reference Newman2007: 270) argues, citizen initiatives ‘‘often have an abundance of bonding ties, but critical to enabling social capital are the bridging ties…’’. These ties reflect the embeddedness of citizen initiatives in the community; they form links between different groups in the community (cf. Smets Reference Smets2011), for instance, ties with other resident organizations, and target groups in the community. Bridging ties can help enhance the organizational capacity of initiatives, because these ties open up potential doors to new volunteers, and other resources, such as tacit knowledge, material, and financial contributions, which enhance realization of outcomes (cf. Bailey Reference Bailey2012; Newman et al. Reference Newman, Waldron, Dale and Carriere2008).

Lastly, linking social capital connects citizen initiatives with formal institutions, as this type of social capital is about relationships between ‘‘people who are interacting across explicit, formal or institutionalized power … in society’’ (Szreter and Woolcock as quoted in Smets Reference Smets2011: 18). Once created and maintained, these ties can help citizen initiatives in gaining access to different forms of government support that will contribute ‘‘to ‘scale up’ the efforts’’ of the initiatives to solve societal problems with their services (Bertotti et al. Reference Bertotti, Harden, Renton and Sheridan2012: 172).

Moving on to the final factor in the model, the figure shows direct and indirect relationships between leadership and outcomes. Leadership has been discussed as a general concept in most studies, in the sense that no specific leadership styles or characteristics are analyzed. There are a few exceptions though. For instance, studies mention the importance of local, dynamic, and entrepreneurial leaders for positive results (e.g., Johnson and Young Reference Johnson and Young1997; Torri and Martinez Reference Torri and Martinez2011). In addition, an autocratic style of leadership was negatively related to outcomes (Torri and Martinez Reference Torri and Martinez2011). On the contrary, boundary spanning leadership is a style that positively influences outcomes and describes the ability of individuals to make connections between for example different groups or spheres (Van Meerkerk et al. Reference Van Meerkerk, Boonstra and Edelenbos2013). These results show in the first place that leadership has a direct influence on outcomes. To further illustrate this relationship, Nilesh (Reference Nilesh2011: 617–618) describes how women community leaders act as facilitators with their leadership activities to increase outcomes of their initiatives. These facilitators are highly engaged in their efforts to achieve external outcomes relevant for the community, encourage participation among members, share ideas, and make efforts to reach out the community at large (Nilesh Reference Nilesh2011: 617–618). These characteristics and activities resemble a specific leadership style distinguished in the literature on leadership, namely transformational leadership, which can be particularly useful in non-profit organizations (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Moynihan and Pandey2012). This style highlights the importance of organizational values, missions, and outcomes and is based on directing and inspiring followers (e.g., Bass et al. Reference Bass, Avolio, Jung and Berson2003; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Moynihan and Pandey2012).

Furthermore, indirect relationships with outcomes are also possible, as well as relationships with other factors, though these have been given less attention in the studies. Regarding the former, transformational leadership can help in strengthening relationships among the core group of the citizen initiative; strengthening bonding social capital. Transformational leaders encourage members in realizing the same goals, which can strengthen bonding ties. People get inspired to work toward the same goal and feel more connected with each other.

Regarding relationships between leadership and other factors, Van Meerkerk et al. (Reference Van Meerkerk, Boonstra and Edelenbos2013) show the importance of boundary spanning leadership for citizen initiatives to create relations with governmental institutions, in other words to create linking social capital. Examples of boundary spanning activities are devoting time to maintain contact with actors outside the initiative, having knowledge of what is important for actors outside the initiative, and connecting relevant external developments to the initiative (cf. Tushman and Scanlan Reference Tushman and Scanlan1981). These activities help citizen initiatives in connecting the initiative’s goals with policy, needs, and agendas of governmental organizations, which helps in creating and maintaining strong relationships. Boundary spanning leadership can also help in creating links with actors in the community; the bridging ties. Though not conceptualized as boundary spanning activities, Nilesh (Reference Nilesh2011) shows how the women facilitators try to bridge two conflicting ethnic groups, for instance, by continuously encouraging inter-ethnic communication, and by their local knowledge and understanding of local issues. Thus, boundary spanning leadership can help initiatives in creating social capital, which, as explained above, enhances organizational capacity and government support that contribute both directly to outcomes.

Discussion and Future Research Directions

In this section, we discuss the results of the review and suggest future research directions. First, we want to emphasize that our study is not without restrictions. One limitation concerns the disregard of books in our selection. We opted for a broad range of concepts used in journal articles. We selected the articles in the first place by looking for the search terms in the abstract and/or title. Therefore, we may have overlooked studies that did cover the search terms but did not mention them in the abstract and/or title. Nevertheless, we have included a broad range of studies (e.g., in terms of disciplines and search terms) that enabled us to get a good overview on citizen initiatives.

A first conclusion of our review is that the range of attention for citizen initiatives is not limited to Western countries. Indeed, from the studies performed within one continent about 32 percent was conducted in non-Western countries in Africa, Asia, and South-America, showing that citizen initiatives are being studied all over the world. Furthermore, it is interesting to see that, even though the studies represent different contexts and use different concepts, such as grassroots initiatives, self-organizations, and civic initiatives, they show similarities in how they conceptualize citizen initiatives. Interestingly, the factors and outcomes bridge institutional and contextual settings as well, meaning that we found the same factors having similar affects in articles studying initiatives in different countries and continents. However, although we found recurring aspects in what citizen initiatives mean, realize, and how their outcomes could be enhanced, an important limitation in current studies is that few go in-depth on these subjects. For instance, we know from this review that leadership is an important factor to enhance outcomes, but we know less about the question what leadership styles are important, and this could differ for different contexts. Furthermore, if we look at the characteristics of the retrieved records, we observe that single-country studies are dominant and that comparisons of citizen initiatives from different sectors are lacking. Hence, we can make two future research suggestions based on these findings. The first is that the systematic knowledge on characteristics, factors, and outcomes of citizen initiatives in this review is in need of in-depth examination and specification in future research. The conceptual model we have constructed in Fig. 5 provides a starting-point. Second, the field of citizen initiatives could use more comparative research (e.g., in different countries, continents, and among sectors), which can further enhance the significance of the review’s findings.

A second conclusion is about a future research strategy. We observed that quantitative research designs and combined qualitative–quantitative designs are used less frequent in the field of citizen initiatives. A mixed-method evaluation of citizen initiatives will require more effort of researchers, as it is usually time-consuming, expensive and researchers will need unprecedented access to information, which the citizens involved, might not always agree upon. However, such a mixed-methods strategy provides a better understanding of research problems than either method by itself (cf. Jick Reference Jick1979). Therefore, possible directions for a future research strategy are the use of surveys and experiments to test how the identified factors relate to outcomes of citizen initiatives, combined with qualitative methods to zoom-in on important relationships and examine underlying mechanisms. The conceptual model in Fig. 5 and discussion of the relationships between factors and outcomes might be helpful in this endeavor.

Moving on to the outcomes of citizen initiatives, this review shows that by self-organizing public services, citizens have the potential to achieve positive outcomes that touch upon a broad range of public values. The identified external outcomes of citizen initiatives are diverse, with citizens taking up roles of crime fighters, trainers, job creators, environmental workers, peace restorers, area developers, trust builders, and many more. Although the studies presented valuable insights about the achievements of citizen initiatives, many studies do not go beyond naming and/or briefly describing the outcomes, lacking a clear conceptualization and operationalization. This finding shows that our knowledge of the actual outcomes of citizen initiatives is still limited. Future research should further examine under which conditions and to what extent citizen initiatives have the capacity to really meet expectations and deliver the type and amount of services they intended to provide. More insight in this is also relevant for governments in monitoring, assisting, and facilitating citizen initiatives to become and remain effective.

Therefore, an important direction for future research is to improve the measurement of the realized outcomes, for example by using clear indicators based on the outcomes identified in this review. A number of studies (n = 15; 23.8%) provide clear conceptualization and operationalization for measuring outcomes. For instance, Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Takeda and Ko2014) conducted a survey among social enterprises and adapted theory-based scales to operationalize performance as achieving organizational (i.e., financial indicators) and social outcomes (i.e., impact on beneficiaries). In addition, Ohmer et al. (Reference Ohmer, Meadowcroft, Freed and Lewis2009) conducted a mixed-method research in which interviews and a survey were used to question respondents about the impact (i.e., physical and environmental outcomes) of community gardens. Using such actual theory-based indicators to measure outcomes strengthens reliability and validity of findings. Furthermore, combining qualitative and quantitative data increases our understanding of what community initiatives actually bring about. Both studies provide examples of how to analyze outcomes in a systematic way, though there is room for more studies with methodological and analytical rigor in measuring outcomes.

Related to this, our fourth conclusion is that, based on this review, we know what factors are important to influence outcomes of citizen initiatives, but we know less on the exact (significant) relationships. The review shows an important explanation for this conclusion, namely the general lack of conceptualization and operationalization of the factors. As an illustration, even though leadership as a factor is part of one of the theoretical perspectives used in the studies, it has been theoretically less conceptualized using concepts that seem to have validity in the context of citizen initiatives, such as transformational leadership and boundary spanning leadership. The current state in the literature tends to be unsystematic, explorative, and descriptive, possibly caused by the dominance of qualitative studies, analyzing effects of factors in a narrative, unstructured way. Perhaps, describing the phenomenon of citizen initiatives in itself has gained more attention than explaining the mechanisms at work. This is not odd given the growing social, political, and policy attention for this topic, and given the shift from traditional governmental public service delivery, to the non-profit sector, to nowadays, self-organization of citizens (cf. Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk Reference Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk2016; Eriksson Reference Eriksson2012; Healey Reference Healey2015).

Nonetheless, it is important to strengthen the explanatory focus in researching citizen initiatives. In this regard, an important future research question is how influencing factors hamper or strengthen outcomes of citizen initiatives. Our systematic review may help to examine this research question in three ways. First, we identified nine frequently mentioned factors that influence outcomes of citizen initiatives and analyzed what is known about their mechanisms. This provides an overview of relevant factors, theoretical expectations, and further research questions. Second, we identified two different main categories of outcomes (i.e., internal and external outcomes) that can be included and further operationalized in future research. Finally, we provided a conceptual model (Fig. 5) in which we theorized how four important factors, government support, leadership, social capital, and organizational capacity, are related to each other and to outcomes of citizen initiatives. Based on this model, we discussed theoretical gaps and research questions to consider, offering important avenues for future research in this field.

Finally, we want to conclude our discussion with a reflection on the democratic values of citizen initiatives and a recommendation to develop a critical approach regarding citizen initiatives, their outcomes, and factors. First, we want to acknowledge that these aspects did not gain much attention in our review, but they, as our results show for at least the democratic perspective, are important topics in the field of citizen initiatives and need further study. Regarding the democratic aspect of citizen initiatives, we can conclude that citizen self-organization seem to have consequences for democracy. One of the factors we identified, concerned a democratic structure, which is about the nature of representation, the source of legitimacy, and transparency of citizen initiatives. This factor shows that citizen self-organization might go hand in hand with the promotion and stimulation of democratic values. The records showed that citizens invested in decision-making processes that include participation and consultation of residents, as well as sharing of information, and transparency regarding internal matters and decision-making (e.g., Torri and Martinez Reference Torri and Martinez2011).

As our findings show, there seems to be a dominant positive discourse around outcomes and factors of citizen initiatives, which makes us wonder what the other side of the coin looks like. What do we actually know about the dark side of citizen initiatives? Some authors mention social inequality as a danger of using self-organization as a political instrument by governments to allocate resources among communities (e.g., Soares da Silva et al. Reference Soares da Silva, Horlings and Figueiredo2018). Communities in which citizens cannot develop a strong network structure could be disadvantaged, as network building seems to be positively related to gaining government resources.

Furthermore, citizen initiatives have political meaning, in the sense that they relate to achieving democratic values and public impact. Moreover, citizen initiatives are about self-control over internal decision-making, but often they have to cooperate with governmental and political institutions as well to get government support for their initiative. Our systematic review informs that government support often comes with a price tag, for example political and bureaucratic interference and related policy goals and administrative burden. What does this mean for the very existence of citizen initiatives? As we did not cover this political aspect of citizen initiatives, future research should invest more into these political dimensions and potential dark sides of citizen initiatives.

Funding

This study was funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) (Grant Number: 406.16.520).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1: Further Information on Coding Process

Selection Process

We started the review with the term citizen initiatives, a common concept in the Dutch literature on citizen self-organization (Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk Reference Edelenbos and Van Meerkerk2016). Because the literature is fragmented across different disciplines with various terms for citizen initiatives, we needed to broaden our scope of search terms. Within an expert group of peers, we discussed which other relevant terms we should include. Eventually, we came up with 16 search terms related to our definition of citizen initiatives (right to the city, shared-reliance, energetic society, self-strength, self-guidance, participatory governments, self-reliance, social enterprise, social entrepreneurship, civic initiatives, self-organization, community self-management, civic entrepreneurship, grassroots initiatives, community-based coalitions, and do-it-yourself). Afterward, we conducted test searches to decide which search terms we would include in our review. Based on the searches, we excluded six terms (right to the city, shared-reliance, energetic society, self-strength, self-guidance, and participatory governments), mainly because of the inappropriateness of the retrieved records (e.g., records about women empowerment without any link to our focus or records about citizens who merely participate in government’s policy initiatives).

Thereafter, we performed the review with the 11 remaining search terms (see Table 1).

The remaining concepts are used as alternatives for citizen initiatives in many studies on the topic, but they are not always comparable. For example, with social enterprise, scholars can mention community self-organizing to solve local problems by using market-based approaches, which falls in our scope. Nevertheless, social enterprises do not necessarily mean citizen involvement in some fields of research, where the focus may lie on profit-making enterprises with social goals. In order to prevent issues with internal validity, we used a specific eligibility criterion during the selection process that captures the essence of our topic (see aforementioned specific eligibility criterion).

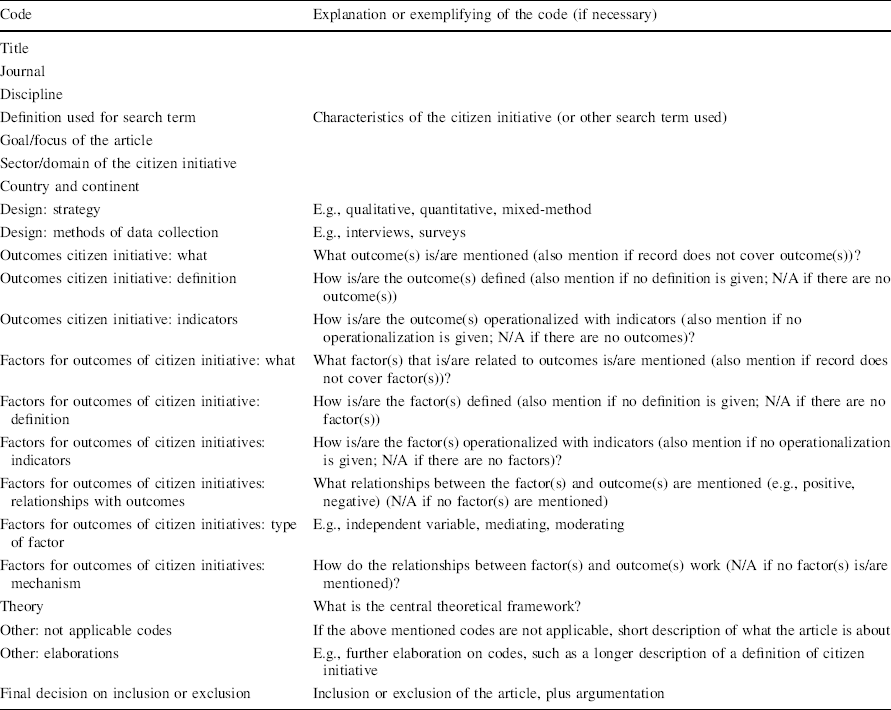

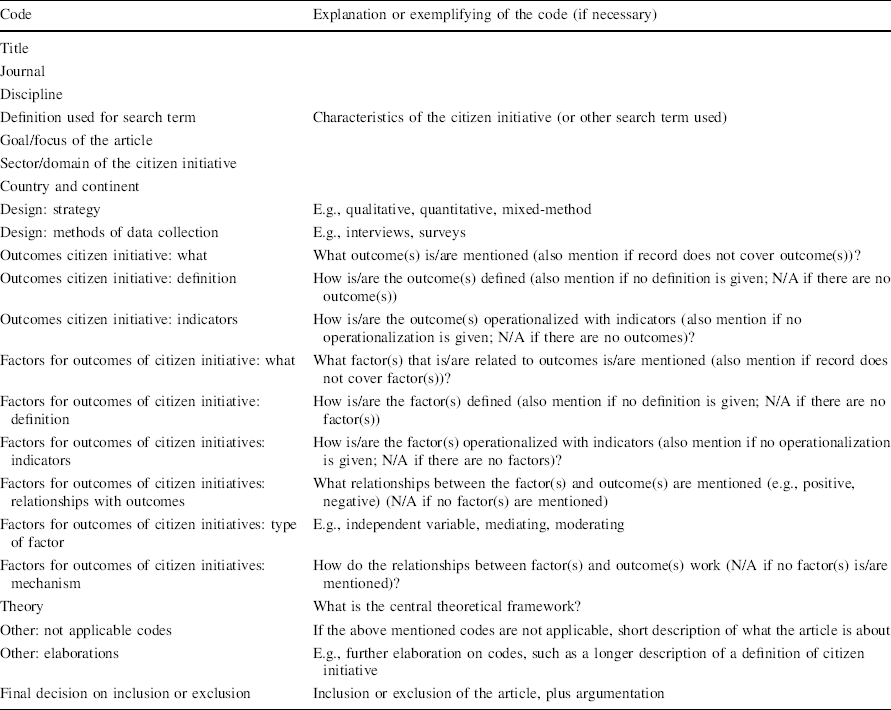

Coding Procedure

The eligible records were divided among the authors for a full reading. For this reading, we developed a coding scheme to analyze and summarize each study, including codes on research designs used (e.g., research strategy and methods), definitions used, factors mentioned, outcomes identified, and theories applied. In case a study did not meet our eligibility criteria after full reading, an explanation was given and discussed during one of our meetings (see below).

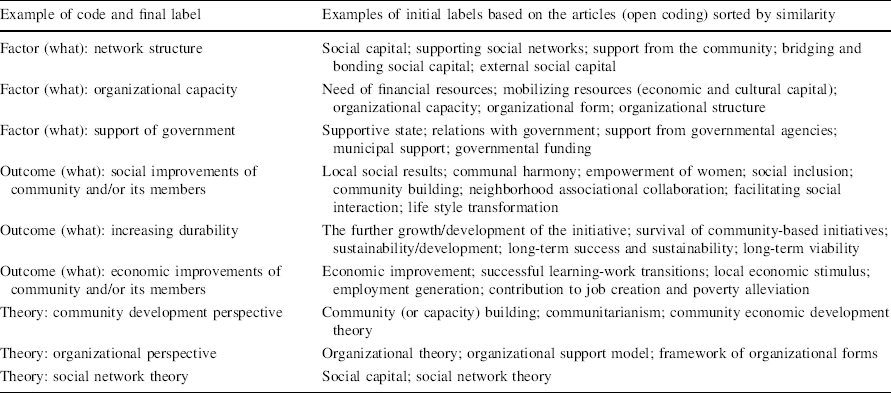

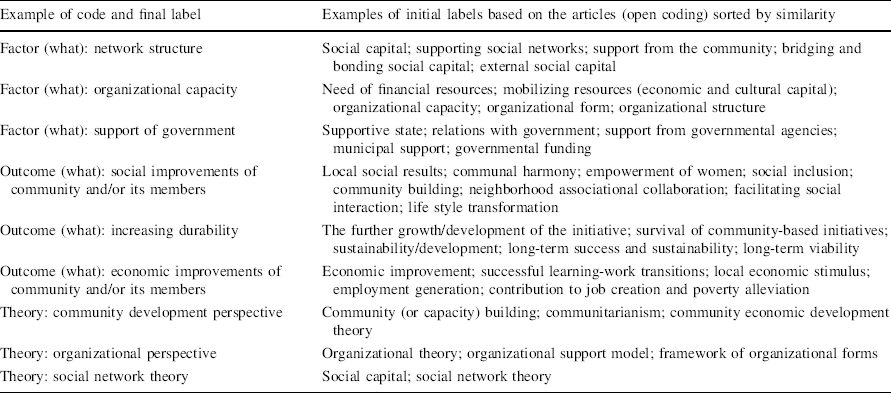

We used an inductive coding approach to identify the factors, outcomes, definitions, and theories used in the study of citizen initiatives (see Table 6 for the full coding book). Then, we discussed the first labels within each of these codes and sorted the studies by these labels to identify similar categorical labels. For instance, after different rounds of full reading, we discussed the final set of labels we inductively found for the factors. During subsequent meetings, we recoded similar labels (e.g., social capital, supporting social networks) into overarching categories (e.g., network structure) and applied this new coding scheme for all (eligible) studies. We repeated this process of back-and-forth coding until all factors were represented by a manageable and clear set of factors (see Table 7 for more examples of the development of coding labels).

Table 6 Final coding book for full reading of articles

Code |

Explanation or exemplifying of the code (if necessary) |

|---|---|

Title |

|

Journal |

|

Discipline |

|

Definition used for search term |

Characteristics of the citizen initiative (or other search term used) |

Goal/focus of the article |

|

Sector/domain of the citizen initiative |

|

Country and continent |

|

Design: strategy |

E.g., qualitative, quantitative, mixed-method |

Design: methods of data collection |

E.g., interviews, surveys |

Outcomes citizen initiative: what |

What outcome(s) is/are mentioned (also mention if record does not cover outcome(s))? |

Outcomes citizen initiative: definition |

How is/are the outcome(s) defined (also mention if no definition is given; N/A if there are no outcome(s)) |

Outcomes citizen initiative: indicators |

How is/are the outcome(s) operationalized with indicators (also mention if no operationalization is given; N/A if there are no outcomes)? |

Factors for outcomes of citizen initiative: what |

What factor(s) that is/are related to outcomes is/are mentioned (also mention if record does not cover factor(s))? |

Factors for outcomes of citizen initiative: definition |

How is/are the factor(s) defined (also mention if no definition is given; N/A if there are no factor(s)) |

Factors for outcomes of citizen initiatives: indicators |

How is/are the factor(s) operationalized with indicators (also mention if no operationalization is given; N/A if there are no factors)? |

Factors for outcomes of citizen initiatives: relationships with outcomes |

What relationships between the factor(s) and outcome(s) are mentioned (e.g., positive, negative) (N/A if no factor(s) are mentioned) |

Factors for outcomes of citizen initiatives: type of factor |

E.g., independent variable, mediating, moderating |

Factors for outcomes of citizen initiatives: mechanism |

How do the relationships between factor(s) and outcome(s) work (N/A if no factor(s) is/are mentioned)? |

Theory |

What is the central theoretical framework? |

Other: not applicable codes |

If the above mentioned codes are not applicable, short description of what the article is about |

Other: elaborations |

E.g., further elaboration on codes, such as a longer description of a definition of citizen initiative |

Final decision on inclusion or exclusion |

Inclusion or exclusion of the article, plus argumentation |

Table 7 Examples of development of coding labels using an inductive coding approach

Example of code and final label |

Examples of initial labels based on the articles (open coding) sorted by similarity |

|---|---|

Factor (what): network structure |

Social capital; supporting social networks; support from the community; bridging and bonding social capital; external social capital |

Factor (what): organizational capacity |

Need of financial resources; mobilizing resources (economic and cultural capital); organizational capacity; organizational form; organizational structure |

Factor (what): support of government |

Supportive state; relations with government; support from governmental agencies; municipal support; governmental funding |

Outcome (what): social improvements of community and/or its members |

Local social results; communal harmony; empowerment of women; social inclusion; community building; neighborhood associational collaboration; facilitating social interaction; life style transformation |

Outcome (what): increasing durability |

The further growth/development of the initiative; survival of community-based initiatives; sustainability/development; long-term success and sustainability; long-term viability |

Outcome (what): economic improvements of community and/or its members |

Economic improvement; successful learning-work transitions; local economic stimulus; employment generation; contribution to job creation and poverty alleviation |

Theory: community development perspective |

Community (or capacity) building; communitarianism; community economic development theory |

Theory: organizational perspective |

Organizational theory; organizational support model; framework of organizational forms |

Theory: social network theory |

Social capital; social network theory |

Checks on Reliability and Validity

After the authors agreed on the criteria and first coding categories, all researchers tried out the actual reviewing process for five articles of one search term. In this way, we pilot tested our review strategy (cf. Fink Reference Fink2014). We discussed the findings and processes of coding and adjusted our coding methods in order to make sure we included or excluded articles for the same reasons. The most important adjustment is that we maintained our definition of self-organizing activities in a stricter way, because sometimes records were included in which, for instance, citizens did not have a leading role after all. This stricter use of the eligibility criteria resulted in a review with more focus and an increased validity.

After this pilot test, the selecting process based on abstracts was carried out for the remaining search terms by one of the researchers. In the stage of full reading, all researchers performed the screening and coding. In order to enhance inter-coder reliability, various intensive meetings between the researchers took place to discuss preliminary results, to recode categorical labels, to identify patterns, and to discuss the question whether to include or exclude some difficult to judge records during the stage of full reading.

Finally, one researcher managed the coding process by continuously going through all codes in an excel spreadsheet (and in addition, in some cases, scan the studies again as a check) to look for inconsistencies, such as blank and incomplete cells (e.g., the type of factor was missing while indicators were mentioned). These findings were then discussed with all researchers face-to-face and/or by e-mail. This intensive process eventually led to a set of articles that was subjected to a consistent and systematic review.