Introduction

Mortality risk is significantly higher in individuals with bipolar disorder than in individuals in the general population [Reference Pan, Yeh, Chan and Chang1–Reference Pan, Yeh, Chan and Chang3]. A study in Taiwan [Reference Pan, Yeh, Chan and Chang1] reported that the life expectancies at birth for patients with bipolar disorder were all significantly lower than the national norms; specifically, the results revealed 14.71 years and 12.69 years of life lost for men and women with bipolar disorder, respectively. Suicide is a major public health concern globally, with 700,000 suicides occurring annually [4]. Relative to other psychiatric disorders, bipolar disorder is associated with a notably high prevalence of suicide attempts and completed suicides [Reference Osby, Brandt, Correia, Ekbom and Sparén5, Reference Tsai, Kuo, Chen and Lee6]. Globally, the risk of suicide is 15–30 times higher in patients with bipolar disorder than in individuals in the general population [Reference Pan, Yeh, Chan and Chang3, Reference Osby, Brandt, Correia, Ekbom and Sparén5, Reference Hoye, Nesvag, Reichborn-Kjennerud and Jacobsen7, Reference Høyer, Mortensen and Olesen8]. The average onset age of bipolar affective disorder is between 20 and 30 years. The risk of suicide is higher in the first few years after the onset of bipolar disorder; however, the risk could remain higher in patients with bipolar disorder, even among older patients, than in the general population [Reference Pan, Yeh, Chan and Chang3, Reference Osby, Brandt, Correia, Ekbom and Sparén5].

Studies [Reference Chen, Tsai, Pan, Chen, Chang and Su2, Reference Tsai, Kuo, Chen and Lee6, Reference Miller and Black9] have revealed several risk factors for suicide in patients with bipolar disorder, including sex, marital status, age, unemployment, previous suicide attempts, a family history of suicide, rapid cycling pattern, comorbid psychosis, genetic predisposition, alcohol or drug use disorder, and a history of childhood abuse. Bipolar disorder entails fluctuating symptoms throughout the lifespan, affecting interpersonal relationships and occupational functioning. Psychological and social conditions with varying stressors at different ages may influence the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder. However, an investigation into how the risk factors for bipolar disorder vary across different age groups is lacking.

The risk factors leading to suicide mortality shortly before suicide mortality are mainly investigated through psychological autopsy studies, in which the circumstances before suicide are reconstructed [Reference Conwell, Duberstein, Cox, Herrmann, Forbes and Caine10, Reference Cheng11]. Big data databases provide large samples for investigating the risk factors for suicide, offering an opportunity for conducting age-stratified analyses of the risk factors. For examining the age-stratified risk profiles of suicide mortality across the lifespan of patients with bipolar disorder, sufficient suicide cases in each age stratum are required.

In this study, to obtain data on a sufficient number of suicide cases, the data of patients with bipolar disorder were linked with the national mortality database in Taiwan. Thus, this study enrolled a large-scale cohort of patients with bipolar disorder. With an age-stratified nested case–control study design with a clear temporal relationship in bipolar patients with various age groups, this study investigated the risk profiles and risk factors (demographic characteristics, health-care utilization, and comorbidities) of these individuals prior to their death by suicide. The findings aid in the formulation of age-specific suicide prevention measures in this population.

Methods

Data sources

Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) contains the medical claims data of the entire Taiwanese population. Various high-impact epidemiological and clinical studies have utilized this validated database [Reference Chen, Tsai, Pan, Chen, Chang and Su2, Reference Chen, Tsai, Chen, Pan, Su and Chen12, Reference Tsai, Cheng, Chang, Bai, Hsu and Huang13]. In the present study, patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (ICD-9-CM codes 296.0–296.16, 296.4–296.81, 296.89, and 296.9; ICD-10-CM codes F30.x and F31.x) at any time between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2021, were identified from the database (n = 45,211). The date of the first diagnosis of bipolar disorder served as the index date. This study was approved by the Taipei City Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Approval No. TCHIRB-10911013), which waived the requirement of informed consent due to the anonymized and retrospective nature of the data.

Identification of suicide mortality cases

To determine the mortality status of each patient, the data of patients with bipolar disorder were linked to the national mortality database for the period spanning from January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2021. In the bipolar disorder group, a total of 11,246 patients were recorded as being deceased throughout the study period. Moreover, the cause of death was determined using ICD-9-CM codes until December 31, 2014, and ICD-10-CM codes from January 1, 2015, onward from the National Cause of Death Registry. Suicide cases were identified using particular codes (ICD-9-CM codes E950–E959 and ICD-10-CM codes X60–X84 and Y87.0), with 1370 patients documented as having died by suicide.

Definition of cases and controls

Individuals with bipolar disorder who died by suicide formed the case group. In this nested case–control study, these individuals were subdivided into five age groups: <30, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years. The date of the suicide death was designated as the index date. Using risk set sampling, controls were selected from living patients with bipolar disorder. In addition, 1 case was matched with up to 10 controls with the same sex and within a year of age (±1) on the index date and within the same year of initial diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The index date of their respective case was defined as the index date for controls. Cases identified later in the follow-up period were considered to be controls for preceding cases. This study’s sample comprised 1,370 cases and 13,700 controls.

Covariates

This study thoroughly reviewed the NHIRD claims data of all cases and controls, including their demographic characteristics, health-care utilization patterns, psychiatric comorbidities, physical comorbidities, and prescribed medications. The demographic and clinical variables encompassed sex, age at baseline, index date, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score, urbanization level of the hospital’s location, and employment status. CCI was employed to assess the severity of physical comorbidities, and the scores of 0, 1, and ≥2 were assigned based on ICD-9-CM codes for primary and secondary diagnoses in the NHIRD [Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie14, Reference Deyo, Cherkin and Ciol15]. As outlined by Liu et al. [Reference Liu, Hung, Chuang, Chen, Weng, Liu and Liang16], the urbanization of the regions of Taiwan was classified into five levels: highly urbanized: level 1, moderately urbanized: level 2, newly urbanized: level 3, township: level 4, and rural: level 5. Health-care utilization was evaluated by examining the proportion and frequency of subspecialty visits. Psychiatric and physical comorbidities were identified using ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 codes (e-Tables 1 and 2 in the Supplementary Material).

Statistical analysis

The suicide mortality rate was computed by dividing the number of total new cases by the person-years contributed by each participant in the cohort. The cohort was classified into distinct age groups. Following a previously described methodology [Reference Chen, Tsai, Pan, Chen, Chang and Su2], the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) in this study was computed by comparing the observed mortality within the bipolar disorder group to the expected deaths in the general population of Taiwan from February 1, 2001, to December 31, 2021. The number of expected suicide mortality cases in the bipolar disorder group was calculated using sex-specific average mortality rates from the corresponding years in the general Taiwanese population. These rates were then multiplied by the person-years contributed by individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder during the at-risk period.

In the nested case–control study design, univariable conditional logistic regression analysis was performed for each age group. In this analysis, factors such as demographic variables, health-care utilization, psychiatric and physical comorbidities in the 3 months leading up to suicide mortality were compared between cases and controls. Subsequently, the backward variable selection method was employed for multivariable analysis, and the models included psychiatric and physical comorbidities. Only variables exhibiting a significant association were retained in the final multivariable model (P < 0.01). Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), with significance set at P < 0.01.

Results

Incidence and SMR stratified by age

In the study cohort of 45,211 patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder, 1,370 individuals with bipolar disorder died by suicide during the follow-up period (e-Figure 1 in the Supplementary Material). The crude suicide rates (e-Table 3 in the Supplementary Material) were 165.2, 264.9, 253.0, 209.6, 151.0, and 85.2 per 100,000 person-years for individuals with bipolar disorder who were aged <30, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years, respectively. The SMR for suicide in the bipolar disorder group was 20.9 (95% CI, 19.8–14.9; P < 0.001). This finding indicates a significant disparity in suicide rates between individuals with bipolar disorder and the general population (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Incidence and standardized mortality ratio (SMR) of patients with bipolar disorder by age and sex. Error bars show 95% CI of incidence and SMR.

Age-stratified analyses revealed that all age groups had SMRs >1.00; SMRs progressively decreased with age. The highest SMR was observed in individuals with bipolar disorder aged <30 years (47.0; 95% CI, 42.1–52.2; P < 0.001), followed by those aged 30–39 years (23.8; 95% CI, 21.3–26.4; P < 0.001). Lower SMRs were found in older age groups. Additionally, in analyses stratified by age and sex, female patients aged <30 years had the highest SMR (76.8; 95% CI, 66.1–88.7; e-Table 3 in the Supplementary Material).

Characteristics of cases and controls

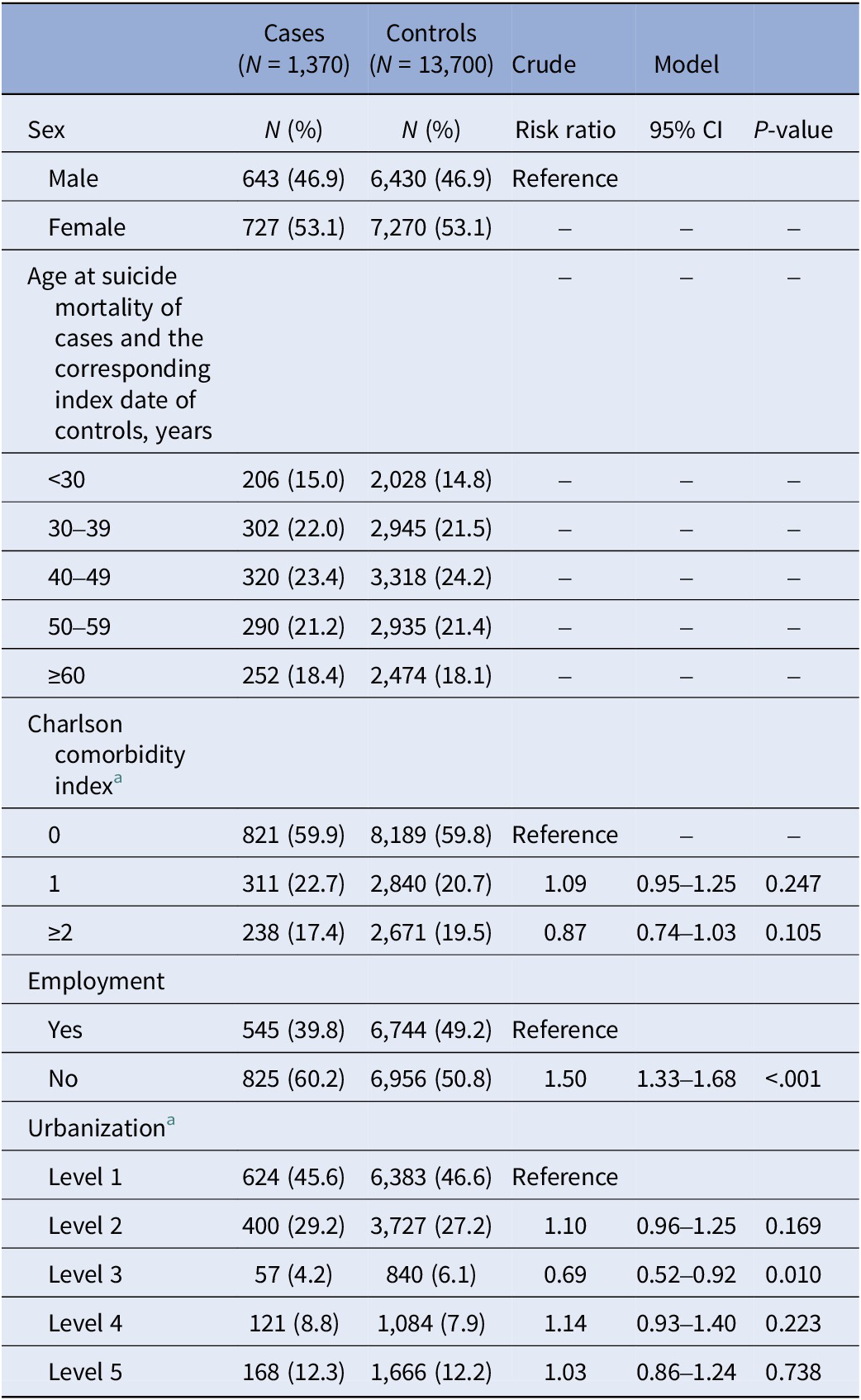

Table 1 outlines the characteristics of patients who died by suicide and their controls. Most individuals who died by suicide were women (53.1%), and the proportion of suicide cases in each age group (i.e., <30, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥ 60 years) ranged from 15.0 to 23.4%. Regarding urbanization levels, we observed that high proportions of both cases and controls resided in areas with level 1 urbanization (highly urbanized areas; 45.2% versus 47.6%) and level 2 urbanization (moderately urbanized areas; 28.6% versus 26.0%). Cases were more likely to be unemployed on the index date than controls (risk ratio = 1.50, P < 0.001).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of cases and controls in a nested case–control study of a bipolar disorder cohort (ratio = 1:10; 1,370 cases and 13,700 controls)

a Level 1: highly urbanized, level 2: moderately urbanized, level 3, newly urbanized, level 4: township, level 5: rural.

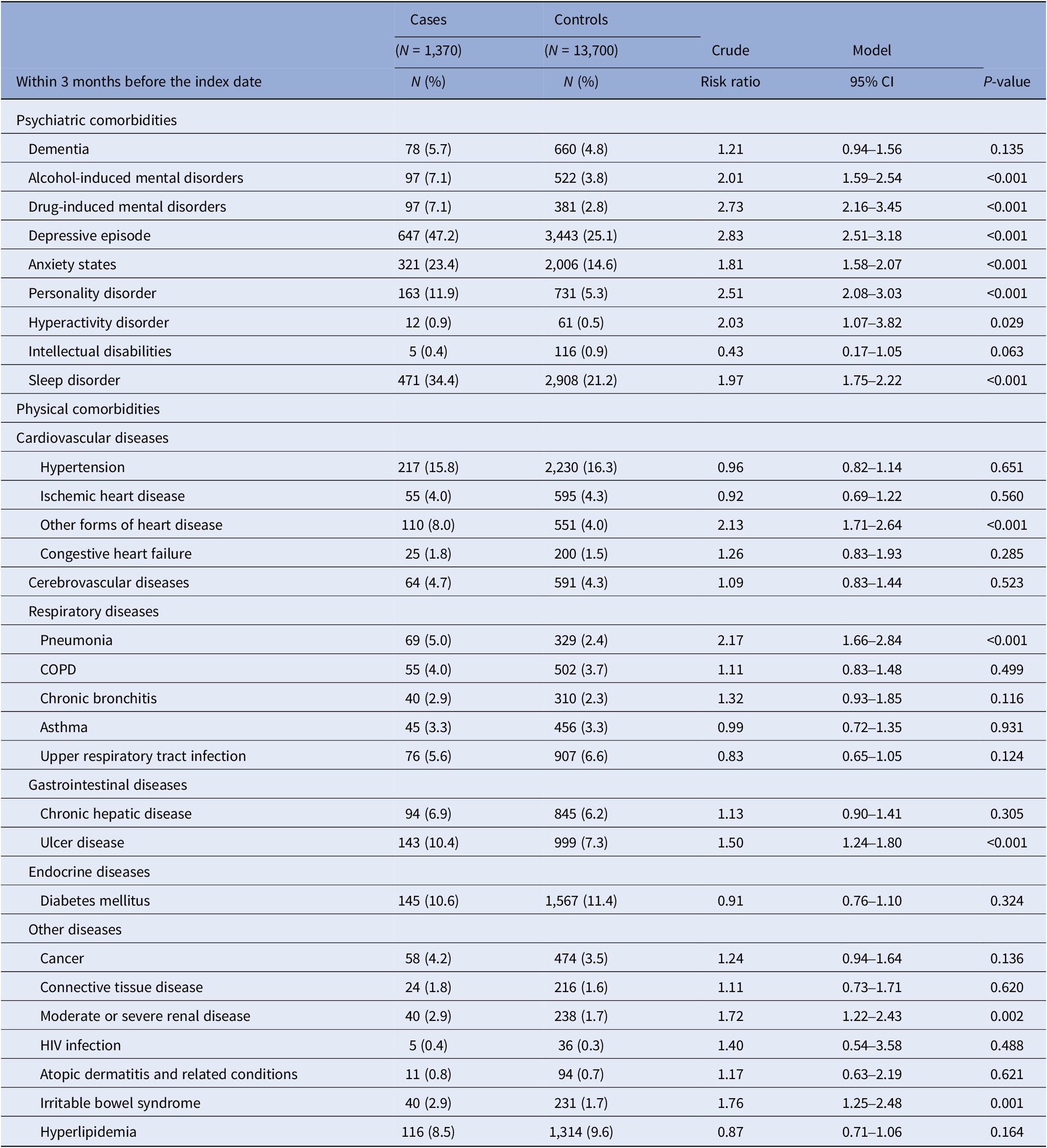

The univariable regression results (Table 2) revealed that suicide was associated with several psychiatric disorders, including alcohol-induced mental disorders, drug-induced mental disorders, depressive episodes, anxiety states, personality disorders, and sleep disorders. Regarding physical comorbidities, other forms of heart disease, pneumonia, ulcer disease, and irritable bowel syndrome were associated with a high risk of suicide mortality.

Table 2. Psychiatric and physical comorbidities of cases and controls in a nested case–control study of a bipolar disorder cohort (ratio = 1:10; 3,848 cases and 13,700 controls)

Demographic characteristics of cases and control groups and age subgroups

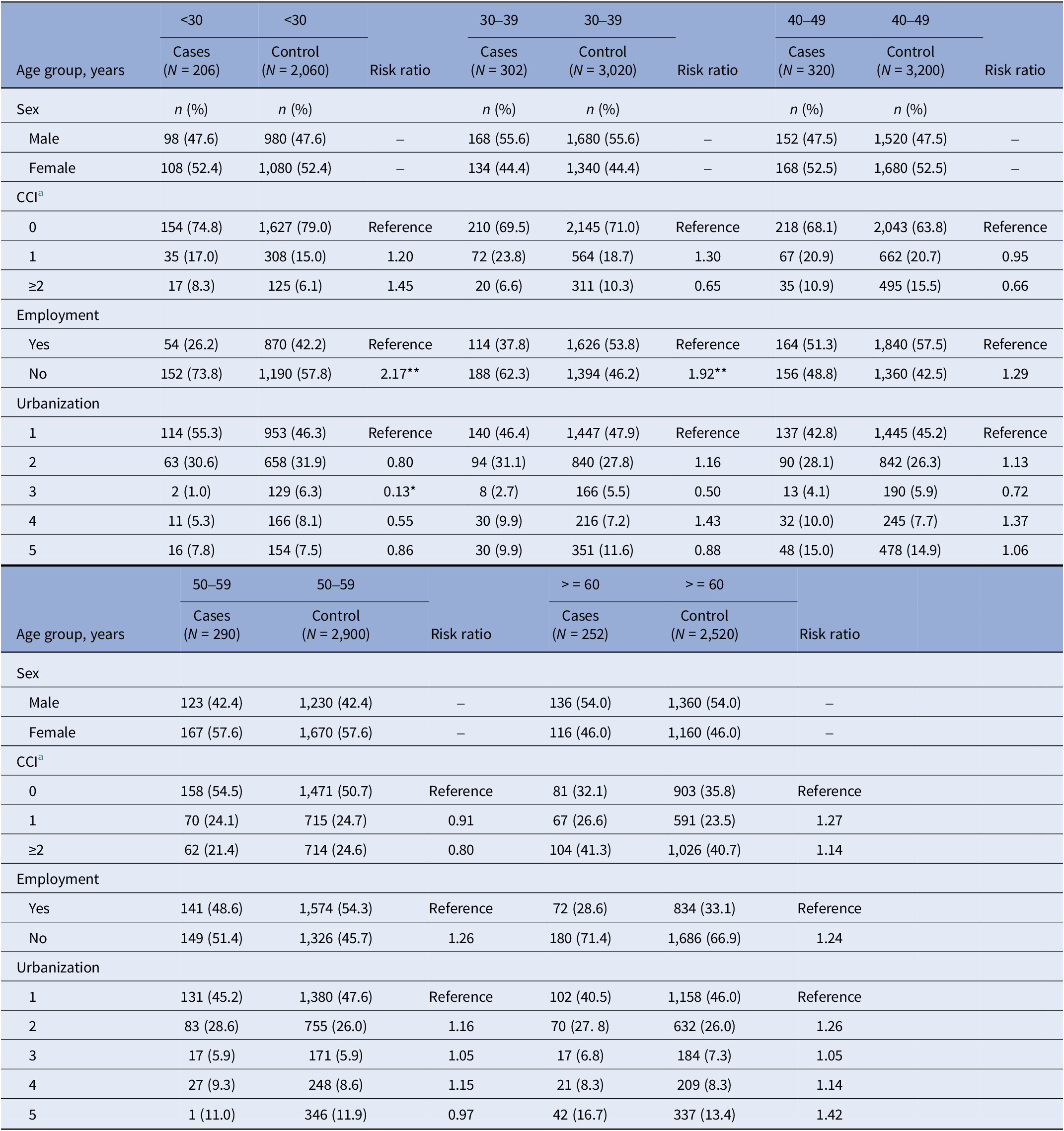

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of the demographic characteristics of the case and control groups and their five age subgroups. Notably, women were overrepresented in terms of suicide mortality in the age groups of <30, 40–49, and 50–59 years. CCI scores were not significantly associated with suicide in each age group.

Table 3. Demographics of cases and controls in a nested case–control study stratified by age groups

a Charlson comorbidity index.

*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001.

Moreover, higher unemployment rates were found among cases than among controls in the <40 years age group, but not in the >40 years age group.

Health-care utilization of cases and controls stratified by age

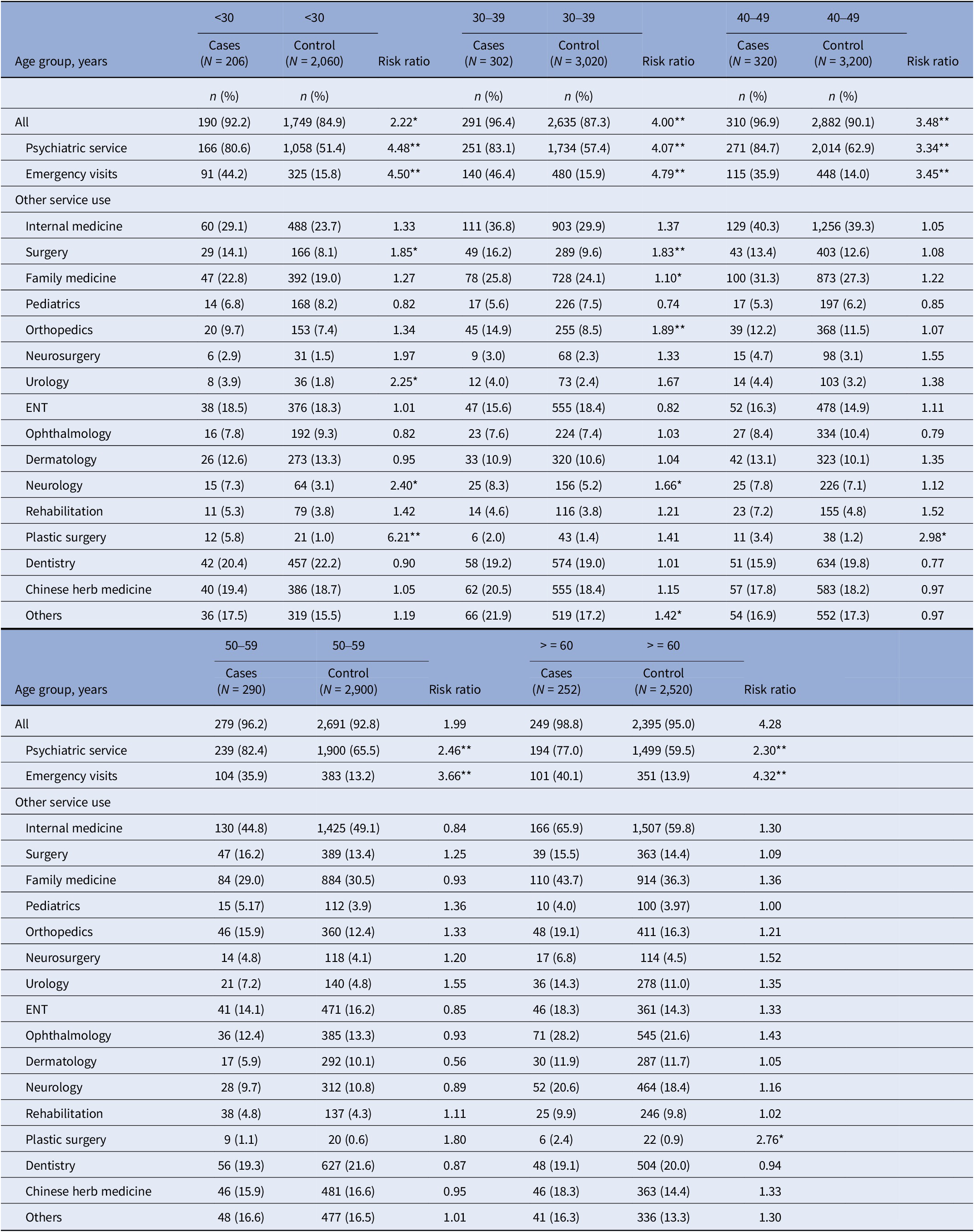

Table 4 presents findings on health-care utilization patterns in the 3 months preceding suicide in cases and controls across the age groups. Across all age groups, the majority of suicide cases had at least one outpatient visit, which was significantly more than that in living controls. Significantly higher risk ratios were found for subspecialty visits to psychiatry and emergency departments in cases than in controls across all age groups.

Table 4. Medical utilization within 3 months before suicide mortality for cases and controls in a nested case–control study stratified by age

*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001.

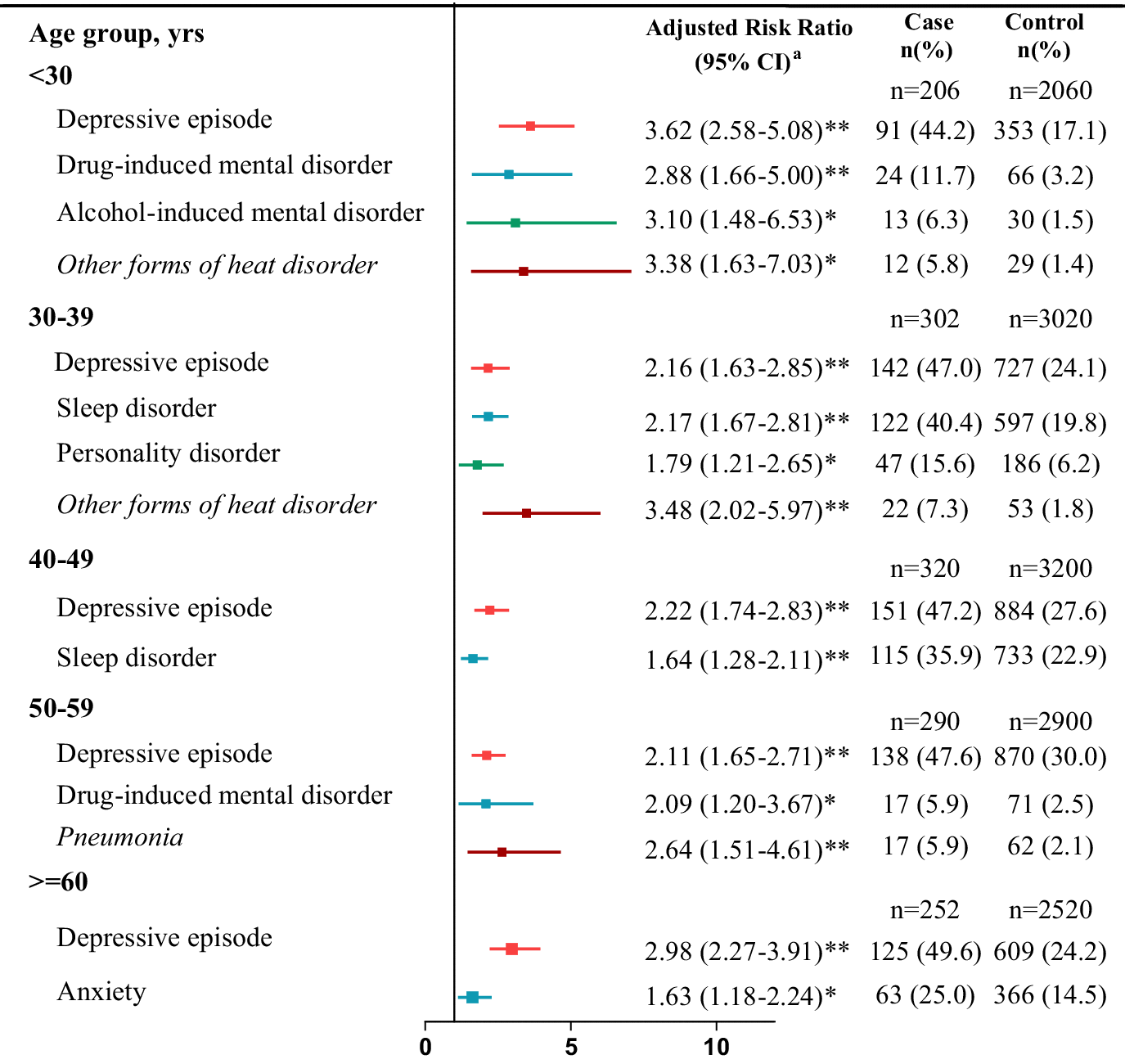

Multivariable analysis

The distribution of psychiatric and physical comorbidities and the results of univariable regression analyses are presented in e-Table 4 in the Supplementary Material. The results of the multivariable analysis are presented in Figure 2 and e-Table 5 in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 2. Multivariable conditional logistic regression of adjusted risk ratios of psychiatric and physical comorbidities in a nested case–control study stratified by age. Variables from e-Table 4 in the Supplementary Material remained in the multivariable conditional logistic regression model with P < 0.01 after stepwise selection. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

Regarding psychiatric comorbidities, the prevalence of depressive episodes was significantly higher among cases than among controls across all age groups. Moreover, increased risks of drug-induced and alcohol-induced mental disorders were prevalent in the <30 years age group for suicide cases, and drug-induced mental disorder was prevalent in the 50–59 years age group. Sleep disorders were associated with suicide mortality in the 30–49 years age group, and personality disorder was associated with suicide in the 30–39 years age group. Anxiety disorder was associated with suicide in the ≥60 years age group.

Regarding physical comorbidities, other forms of heart disease were associated with suicide in the age group of <40 years. Pneumonia was associated with a high risk of suicide in the 50–59 years age group.

Discussion

Major findings

To the best of our knowledge, this population-based cohort study is the first to examine age-specific risk profiles for suicide mortality throughout the lifespan of patients with bipolar disorder. The SMRs ranged from 9.5 to 47.0 across the age groups. Moreover, young female patients with bipolar disorder who were aged <30 years had the highest SMR (76.8).

Incidence and SMR

This study found that young patients with bipolar disorder who were aged <30 years had the highest SMR, which accords with the findings of previous studies [Reference Pan, Yeh, Chan and Chang3, Reference Osby, Brandt, Correia, Ekbom and Sparén5]. Young patients with early-onset bipolar disorder often experience a prolonged and severe disease course, with persistent symptoms and infrequent remission. Compared with adults, young patients with bipolar disorder experience significantly more mixed and cycling episodes and frequent mood polarity shifts per year [Reference Baskaran, Cha, Powell, Jalil and McIntyre17]. Additionally, they are more vulnerable to the compounded effects of stressors, including difficulties in interpersonal relationships, academic challenges, and unfavorable job conditions, which may increase their risk of suicide mortality [Reference Baskaran, Cha, Powell, Jalil and McIntyre17].

Globally, men have higher suicide rates than women, with approximately three of four deaths by suicide occurring among men [4]. In the general population of Taiwan, a significantly higher incidence of suicide mortality was found in male patients than in female patients [Reference Pan, Yeh, Chan and Chang1]. The present study observed that young female patients aged <30 years had the highest SMR. Moreover, this study revealed that the incidence of suicide mortality was higher in female patients aged <30 years than in their male counterparts. This finding suggests that young female patients with bipolar disorder have an increased risk of suicide; hence, careful attention should be paid to these patients. Further research should be conducted to reveal the potential reasons for these findings. Women with bipolar disorder may be more vulnerable to psychosocial stressors than men with bipolar disorder [Reference Chen, Tsai, Pan, Chen, Chang and Su2]. Although our study focused on young female patients (<30 years) because of the exceptionally high SMR (76.8) found in this age group, the data reveal that women in other age groups also exhibit increased suicide mortality rates compared with men. This broader age group of female patients affected by suicide risk suggests that gender-related vulnerabilities in bipolar disorder extend beyond early adulthood. Studies have suggested that biologically, women with bipolar disorder are more susceptible to inflammatory and metabolic disruptions than their male counterparts [Reference Baskaran, Cha, Powell, Jalil and McIntyre17]. These disruptions may in turn increase their risks of psychiatric and physical comorbidities [Reference Crump, Sundquist, Winkleby and Sundquist18], potentially increasing their suicide risk.

Employment status

In this study, the employment rate in the control group (patients with bipolar disorder without suicide mortality) ranged from 33.1% (aged >60 years) to 54.3% (50–59 years). This finding is consistent with that of previous studies, which have found employment rates of 40–60% in patients with bipolar disorder [Reference Marwaha, Durrani and Singh19] and only 10–30% in patients with schizophrenia [Reference Haro, Novick, Bertsch, Karagianis, Dossenbach and Jones20].

A major finding of the present study is the significant association between unemployment and suicide risk only in patients younger than 40 years. Holm et al. [Reference Holm, Taipale, Tanskanen, Tiihonen and Mitterdorfer-Rutz21] observed an employment rate of approximately 45% in the 3 years before the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and a decline in this employment rate after 1 year from the diagnosis. Thus, monitoring the employment status of patients is crucial, and vocational rehabilitation must be provided during the first few years after bipolar disorder onset.

Young patients with bipolar disorder who are unemployed may struggle with financial difficulties and low self-esteem, making them vulnerable to depression; depression development can increase the risk of suicide among these patients [Reference Chen, Tsai, Pan, Chen, Chang and Su2, Reference Rajewska-Rager, Sibilski and Lepczyńska22]. Patients with bipolar disorder aged >40 years, although unemployed, may have become accustomed to their condition or are receiving social welfare assistance, which may lead to a decreased risk of suicide.

Health-care utilization

A previous study reported that individuals who died by suicide had higher rates of health-care utilization across all ages. Moreover, before suicide, a high relative risk and a high absolute health-care utilization rate (43.8%) for emergency room services were found [Reference Ahmedani, Westphal, Autio, Elsiss, Peterson and Beck23]. In this study, we reported that in each age group, patients with bipolar disorder tended to exhibit increased visits to the emergency department and increased utilization of psychiatric services separately within 3 months before suicide mortality. This study revealed that most cases and controls resided in areas with high or moderate urbanization levels. Urban stressors, such as high living costs, crowded living conditions, and fast-paced lifestyles, may negatively affect mental health and increase suicide risk in patients with bipolar disorder, potentially leading to their increased health-care utilization [Reference Montanari, Wang, Birenboim and Chaix24, Reference Cyr, Etchin, Guthrie and Benneyan25]. Our findings suggest that patients living in urban areas have greater access to psychiatric services and emergency departments than do their counterparts residing in rural areas; this is possibly due to the greater availability of specialized care in urban areas, which results in differences in health-seeking behaviors between urban and rural populations. These observations underscore the importance of reducing barriers to health care in order to improve healthcare accessibility.

Patients with bipolar disorder who died by suicide may have had unstable mental states (such as depressive episodes) before their death; thus, they are more likely to seek psychiatric care or to visit the emergency department. A previous suicide attempt is widely recognized as one of the most significant predictors of suicide death across all populations [4]. Studies [Reference Tsai, Kuo, Chen and Lee6, Reference Simon, Hunkeler, Fireman, Lee and Savarino26] have also revealed that a previous suicide attempt is a significant predictor of death by suicide in patients with bipolar disorder. Those who have attempted suicide may require visits to the emergency department for psychiatric crisis intervention and injury care.

In summary, increased use of psychiatric and emergency services before suicide may reflect underlying psychiatric and physical comorbidities, so targeted interventions are needed for prevention.

Psychiatric comorbidities

Intriguingly, one of the major findings in this study showed that psychiatric comorbidity contributes to suicide mortality more than physical comorbidity. Several psychiatric comorbidities were identified to be significantly associated with suicide in various age subgroups.

This study observed that in each age group, a depressive episode of bipolar disorder was associated with suicide. Additionally, suicide attempts lead to more lethal consequences in individuals with bipolar disorder than in those with other psychiatric conditions [Reference Dennehy, Marangell, Allen, Chessick, Wisniewski and Thase27]. The attempt-to-completion ratio is 3:1 in patients with bipolar disorder compared with 35:1 in the general population [Reference Plans, Barrot, Nieto, Rios, Schulze and Papiol28]. This observation highlights the high burden of depression in patients with bipolar disorder and the increased lethality of suicide attempts, which contribute to increased suicide rates [Reference Miller and Black9]. Considering this association, early identification of and targeted intervention for depressive episodes are critical for reducing the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.

This study determined that drug- and alcohol-induced mental disorders were linked to suicide mortality in individuals with bipolar disorder aged <30 years. Additionally, drug-induced disorders were a risk factor for those aged 50–59 years. Therefore, drug-induced mental disorders were associated with increased suicide risk in both individuals aged <30 years and those aged 50–59 years. In the younger group, drug-induced mental disorders were linked to the use of illicit drugs, and in the older group, these disorders may be associated with prescribed medications, such as benzodiazepines.

A previous study revealed a higher prevalence of substance use, particularly the use of highly addictive and hallucinogenic substances such as cocaine, amphetamines, opioids, cannabis, and hallucinogens, in individuals with bipolar disorder than in those with schizophrenia [Reference Maremmani, Bacciardi, Gehring, Cambioli, Schütz and Jang29]. Ernst et al. [Reference Ernst and Goldberg30] observed that 46% of patients had bipolar disorder onset before the age of 19 years and that early onset before the age of 19 years was associated with comorbid substance abuse. Young patients with bipolar disorder tend to exhibit impulsive behaviors, and this impulsivity is closely associated with the prevalence of substance use disorders, both of which are indicators of suicide risk [Reference Grant, Stinson, Dawson, Chou, Dufour and Compton31–Reference Swann, Dougherty, Pazzaglia, Pham and Moeller33].

Few studies have explored whether sleep disorders are a risk factor for suicide across different age groups of patients with bipolar disorder. A study revealed a correlation between nightmares and suicide in patients with bipolar disorder in the 6–15 years age group [Reference Stanley, Hom, Luby, Joshi, Wagner and Emslie34]. The present study demonstrated that sleep disorders were associated with suicide risk in the 30–49 years age group, but not in the <30 age group. This may be because individuals with bipolar disorder aged 30 to 49 years are in their working years, and sleep disorders during this period exert additive effects with stress responses, thereby increasing their risk of suicide. However, further research is required to verify this hypothesis.

A study demonstrated that anxiety disorders increase the risk of suicide [Reference Khan, Leventhal, Khan and Brown35]. Individuals with bipolar disorder are more likely to have anxiety disorders than the general population, and approximately 45% of these patients exhibit comorbid anxiety disorders [Reference Pavlova, Perlis, Alda and Uher36]. In this study, we identified that anxiety was associated with suicide only in older patients with bipolar disorder. We deduced that anxiety disorders are the most common mental disorder in later life [Reference Andreas, Schulz, Volkert, Dehoust, Sehner and Suling37]. Moreover, older patients with bipolar disorder have a higher likelihood of suicide than younger individuals [Reference Voshaar, van der Veen, Kapur, Hunt, Williams and Pachana38].

Univariable analysis (e-Table 4 in the Supplementary Material) revealed a significant association between anxiety and suicide in individuals aged <30 years. However, in multivariable analysis, the association between anxiety and suicide did not remain significant in the model, as factors such as depressive episodes, drug-induced disorders, and alcohol-induced disorders outweighed the suicide risk.

Physical comorbidities

Patients with bipolar disorder have a higher rate of comorbidities than the general population or individuals with schizophrenia [Reference Chen, Tsai, Pan, Chen, Su and Chen39, Reference Chen, Chen, Pan, Chen, Su and Tsai40]. However, in this study, we found that physical comorbidities had lower effects on suicide, and only other forms of heart disease in the <40 years age group and pneumonia in the 50–59 years age group were associated with an increased risk of suicide.

Bipolar disorder is strongly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases (e.g., other forms of heart disease and ischemic heart disease) [Reference Chen, Tsai, Pan, Chen, Su and Chen39], which comprise a major cause of death in patients with bipolar disorder [Reference Chen, Tsai, Chen, Pan, Su and Chen12]. Patients with cardiovascular diseases have a lower quality of life or have comorbid depression, increasing their risk of suicide.

A large-scale Denmark study [Reference Lund-Sorensen, Benros, Madsen, Sorensen, Eaton and Postolache41] revealed that patients who had been hospitalized with an infection had a 40% increased risk of suicide. For patients with seven or more infections, the risk of suicide increased by nearly 300%, indicating a dose–response relationship. This finding reinforces the causal relationship of infections with suicide. These findings suggest that inflammation may play a relevant role in the pathological mechanisms underlying suicidal behavior. However, in this study, pneumonia was associated with an increased risk of suicide only in the 50–59 years age group. The underlying reason remains to be investigated.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, including the use of a nationwide cohort of bipolar disorder patients and a sufficient number of suicide cases. Furthermore, we employed a nested case–control study design, which reflects the circumstances leading to suicide, facilitating the investigation of age-stratified short-term risk profiles before the event.

However, this study has several limitations. First, this study did not examine certain variables that were potentially associated with suicide, such as lifestyle factors or previous suicide attempts. Second, competing risks may occur. Some patients with bipolar disorder could have died from causes other than suicide, which would have excluded them from being at risk of subsequent suicide mortality during the study period. Third, we included only patients with bipolar disorder who had been hospitalized, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the entire population of patients with bipolar disorder.

Finally, this study offers valuable insights into suicide risk in patients with bipolar disorder. However, further research is required on this topic. Given the limitations of the age-stratified nested case–control study design, this study examined comorbidities within the 3 months preceding suicide mortality rather than identifying temporal trends. Future larger longitudinal studies should be conducted to explore the progression of mental health conditions and their association with suicide risk. Additional studies should explore how substance use contributes to suicide mortality; these insights may aid in the development of targeted strategies for suicide prevention in patients with bipolar disorder.

Implications

This study found increased suicide risks across all age groups of patients with bipolar disorder, especially among younger individuals. Vocational rehabilitation is crucial for suicide prevention among those aged <40 years. Various risk factors for suicide were identified across different age groups. Based on these insights, enhanced health-care intervention strategies should be developed for preventing suicide in patients with bipolar disorder in different life stages.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.2451.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as the national registry raw data is not accessible due to privacy protection regulations.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the BEST center at Taipei City Psychiatric Center, Taipei, Taiwan. This manuscript was edited by Wallace Academic Editing.

Author contribution

Drs. Lin, WY Chen, and Kuo conceived and designed the study. Dr. Kuo acquired the data. Mr. Su performed statistical analyses. Drs. Pan, Tsai, and CC Chen provided administrative and material support. Drs. Lin and Kuo drafted the manuscript. Drs. WY Chen made critical revisions to the manuscript for important intellectual content. Drs. Tsai and CC Chen supervised the study.

Financial support

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 110-2314-B-532-003-MY3; NSTC 113-2314-B-532-002) and Taipei City Hospital (11201-62-002, 11301-62-001, and 11401-62-001). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.