Introduction

The health and health behaviours of women and men prior to pregnancy are key determinants of a successful pregnancy and the health of women, men and their offspring in the short- and long-term. Reference Fleming, Watkins and Velazquez1,Reference Stephenson, Heslehurst and Hall2 There is now ample evidence from developmental biology and epidemiological studies that improving preconception health represents an opportunity to reduce maternal and infant mortality and morbidity, prevent non-communicable disease in parents themselves and their offspring and improve the overall health of at least two generations. The importance of optimal preconception health has been recognised in many national and international guidelines, position statements and policy reports. These provide clinical guidance on providing preconception care (PCC) to individuals planning pregnancy, 3-9 outline how primary care, maternity and community services may integrate PCC into existing services 5,6,9-12 and call for continued efforts to improve the health of the population more broadly. 4-6,9,10,12,13

While there has to date been little progress on widespread implementation of PCC and preconception health programmes and interventions, advocacy for preconception health initiatives is increasing internationally. Examples include a focus on the health of girls and women during the adolescent and reproductive years in the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 14 and in the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescent’s Health 2016–2030. 15 As a result, interventions that increase awareness of the importance of preconception health and that promote pregnancy planning and preparation are likely to be developed to meet the goals set out in these global strategies. National and local programmes and interventions are emerging 10,Reference Jacob, Newell and Hanson16,17 and already being tested and implemented in some countries such as the USA, China, Belgium and the Netherlands. Reference Ebrahim, Lo, Zhuo, Han, Delvoye and Zhu18-Reference Walani, Moley, Shawe, Steegers and Verbiest20 To inform and evaluate such initiatives and to track progress made towards optimising preconception health, there is a need for guidance on the assessment and monitoring of population-level indicators that measure the state of preconception health.

In the UK, the Preconception Partnership was established in 2018 as a multi-disciplinary advocacy coalition with the aim to improve preconception health. The Partnership has set out a conceptual framework for reporting and monitoring of preconception indicators in England based on a set of routinely collected data sets, or ‘core metrics’. Reference Stephenson, Vogel and Hall21 We define preconception indicators as medical, behavioural and social risk factors or exposures as well as wider determinants of health that may impact potential future pregnancies among all women and men of reproductive age. 10,17 National data on these indicators would facilitate characterisation of the nation’s preconception health, monitoring of trends and identification of inequalities, to incite action from local and national governments and organisations to deliver resources for effective and appropriate interventions. Internationally, there is currently no comprehensive and recognised set of preconception indicators that could fulfil these functions using data sources available at a national level in countries such as England.

To inform the reporting of population-level preconception health in England, we aimed to conduct a review of relevant guideline and policy documents to identify a comprehensive set of indicators and to map these against national data sources currently available. Moreover, we provide perspectives from (healthcare) professionals to illustrate how findings from population-level surveillance of preconception health may be used to inform the development of interventions and campaigns and improve patient care in primary care and community settings.

Methods

Review of preconception guidelines, recommendations and policy reports

Search strategy

An electronic search was carried out in Google and Google Scholar in March 2021 by DS, and relevant guideline repositories and websites of professional organisations/associations and ministries of health were searched, to identify publicly available preconception guidelines, recommendations, position statements and policy reports in England and internationally. The following search terms were used: Preconception; Preconceptual; Pre-pregnancy; Before pregnancy; Pregnancy planning; Preparing for pregnancy AND Guidelines; Recommendations; Policy.

Eligibility criteria

Guidelines, statements and policy documents aimed at the public or patients, healthcare professionals and governments reporting on preconception indicators that could be assessed in individuals (i.e. not for example at health service or household level) were considered relevant. In addition, preconception recommendations published in English by other countries were included to identify additional preconception indicators reported internationally but not included in documents relevant to England. International documents were not included if no additional preconception indicators were identified beyond those already reported in documents relevant to England. Electronically available information considered relevant for identifying preconception indicators included documents and other online information sources from government organisations, national healthcare organisations, professional bodies and societies and charitable organisations.

Data extraction

Key features of the guidelines, statements and policy documentation (including the overall topic, the target audience(s) and country) and all preconception indicators mentioned in these sources were extracted by DS. The identified preconception indicators were grouped into overarching domains based on shared characteristics. Measures that describe the prevalence of the indicators were formulated based on the guidelines and recommendations reviewed.

Aligning preconception indicators with core data sources

Following identification of preconception indicators, population-based national data sources from which prevalence data on indicators could be extracted were identified through known UK websites providing information on national data sets, national data reports or surveillance of health indicators. Examples include websites from NHS Digital, 22 the UK Data Service, 23 Public Health Outcomes Framework 24 and Office for National Statistics. 25 Eligible data sources included national routine data sets, national surveys and national cohort studies. We excluded data sources if they did not include individual-level data for women and/or men of reproductive age (defined as aged 16–45 years 3 ), or if data were not directly available or accessible through online data reports or tools. For each data source, information was summarised on the representativeness of the population, the method and frequency of data collection, reporting of relevant preconception indicators and data access.

Preconception indicators were aligned with a data source where possible. If an indicator was not available but a comparable measure was reported in a data source, the comparable measure was included to reflect an approximation of the preconception indicator as specified in guideline and policy documents.

Results

Preconception indicators

The search for publicly available guidance on preconception health in England identified 15 clinical guidance or recommendation documents, three position statements, two policy reports, one e-Learning programme and online information from one charitable organisation (Supplementary Table S1). Guidance was aimed at healthcare professionals, commissioners and providers or the public and was relevant to the general population of reproductive-aged women and men, individuals planning pregnancy and/or populations with pre-existing medical conditions or at high risk of an adverse pregnancy or birth outcome. International guidance related to preconception health that reported additional indicators not described in documents relating to England included clinical preconception care recommendations from the USA and Canada, a position statement from Australia and a policy brief from the World Health Organization (WHO) (Supplementary Table S1). Examples of international documents that were identified but that did not report preconception indicators not already reported in documents relevant to England included the Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India (FOGSI) Good Clinical Practice Recommendation on Preconception Care, 26 a call to action for preconception health promotion and care by the Ontario Public Health Association 27 and a report commissioned by NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde on Preconception health, education and care in Scotland. 28

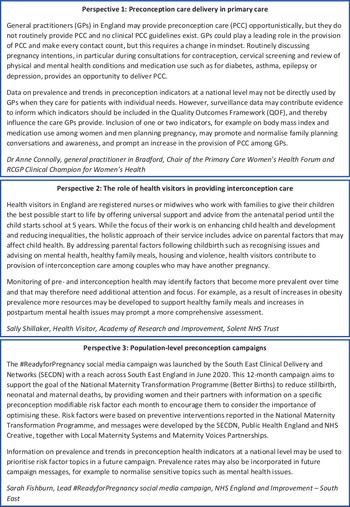

Preconception indicators were grouped into 12 domains containing a total of 66 indicators (Table 1). Detailed measures formulated based on guidelines and recommendations can be found in Supplementary Table S2. Several preconception indicators could be assessed using multiple measures, and separate measures were formulated for women and men, for high-risk groups and categorical indicators (such as body mass index classifications) based on clinical guidance. While guidance was mainly focused on preconception health of women, some clinical guidelines, 3,4,6,12,29,30 a Clinical Effectiveness Unit position statement 12 and Tommy’s charity 31 reported on preconception indicators relevant to men.

Table 1. Summary overview of identified preconception indicators and their recording in national data sources

Abbreviations: ALAS, Active Lives Adult Survey; BCS70, 1970 British Cohort Study; CPRD, Clinical Practice Research Datalink; CSDS, Community Services Dataset; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics; HFEA, Human Fertilisation Embryology Authority; HSE, Health Survey for England; MCS, Millennium Cohort Study; MSDS, Maternity Services Dataset; Natsal, British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles; NCARDRS, National Congenital Anomaly and Rare Disease Registration Service; NCSRAS, National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service; NDA, National Diabetes Audit; NDNS, National Diet and Nutrition Survey; NHSDS, NHS Dental Statistics; ONS, Office for National Statistics; RCGP, Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Centre database; SRHAD, Sexual and Reproductive Health Activity Dataset.

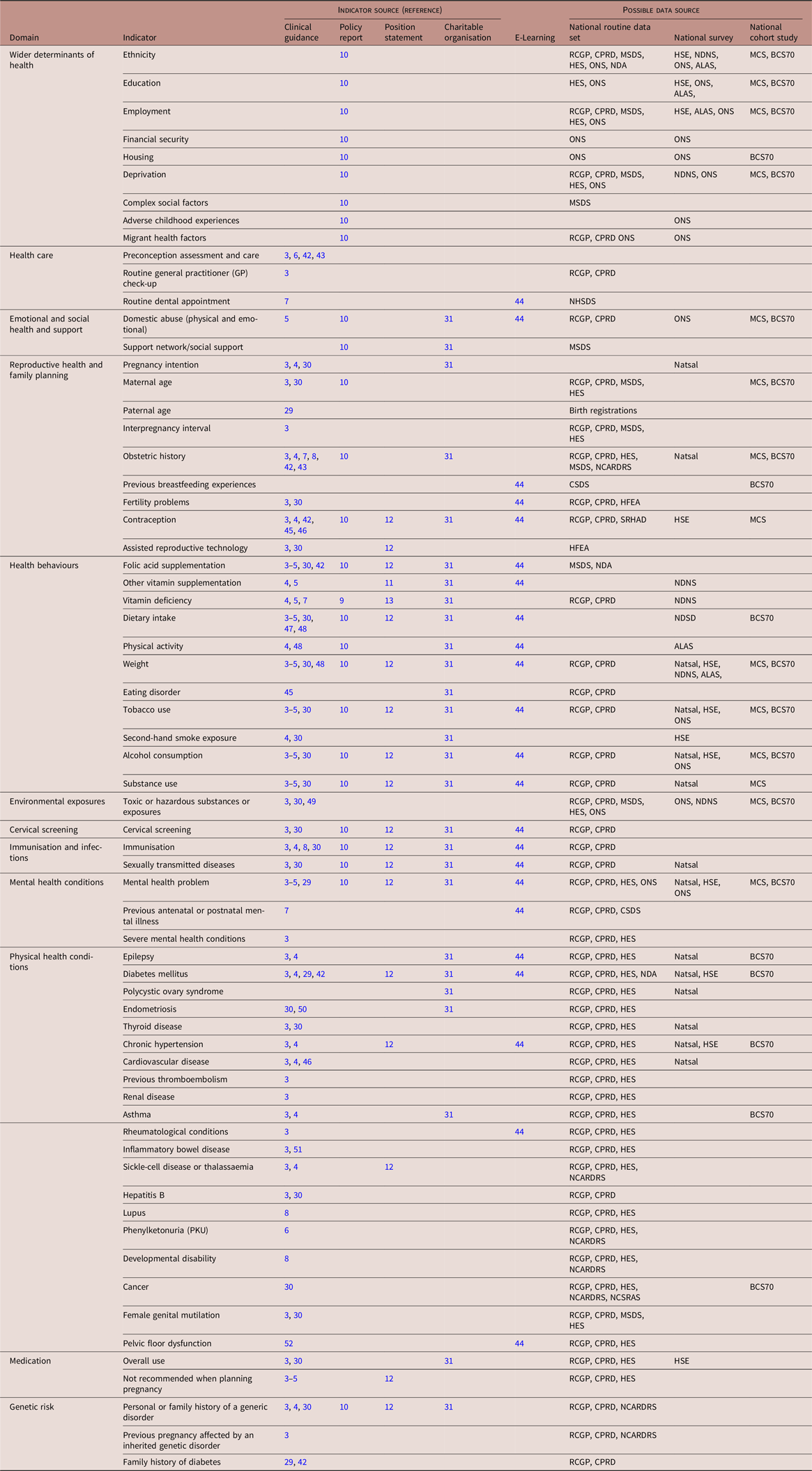

Core data sources

National data sources with relevant information on preconception health included 13 routine health data sets, five surveys and two cohort studies (Table 2). Routine health data sets cover data reported in primary care, hospital, maternity, community and specialist health services, disease registries and the census. National surveys are repeated cross-sectional surveys among a random representative sample, and national cohort studies include longitudinal population-based studies following the lives of people born in a specific week or year from birth onwards at 2–10 year intervals. Data for surveys and cohort studies are collected through questionnaires, face-to-face interviews, physical examinations and biological samples. Anonymised annual data for individuals across their reproductive years are available to policymakers and researchers for the majority of data sources following protocol approval through NHS Digital or the UK Data Service (Table 2). Key statistics from most routine data sets and surveys are published online at least annually. These reports do not cover all indicators measured in each data source and are generally not aggregated specifically for women and men of reproductive age.

Table 2. Core data sources for the reporting and monitoring of preconception indicators in England

GP, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service.

Data sources that were identified, but not considered relevant include the General Practice Quality Outcomes Framework (includes practice-level but not individual-patient-level data on relevant preconception indicators), the Mental Health Services Data Set (includes data on care provided to people using mental health services, but no individual-level data on diagnosis of mental health conditions) and the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Registry (IBDR) (no individual-patient-level data available for research or accessible online).

From the total number of 66 identified preconception indicators, 65 were reported in at least one data source (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). Collectively, national routine data sets include data for all domains and nearly all indicators except measures on adverse childhood experiences, preconception assessment and care, pregnancy intention, dietary intake and physical activity. Data on indicators related to health behaviours including diet and physical activity are collected in detail and through validated methods in surveys and cohort studies. A measure of preconception health assessment and care was not identified in any current national data source.

Discussion

This review is the first critical step in the process of developing a national surveillance system for preconception health in England. Based on national and international guidelines and policy documents, we identified a comprehensive set of preconception indicators that can be used to characterise and monitor the health, health behaviours and their wider determinants among women and men of reproductive age using available national population-based data sources. A national picture of preconception health can improve our understanding of the population’s preconception needs, inform the development and evaluation of new campaigns and interventions, and thereby facilitate translation of evidence into actions to improve preconception health.

Existing public health surveillance systems in England, such as those managed by Public Health England 24 and the Office for National Statistics, 25 produce and publish regularly updated population-level data on a large number of indicators across a broad range of topics. These include wider determinants of health and indicators relevant to preconception health such as obesity and smoking prevalence. We present an extension to these existing surveillance efforts based on indicators that are relevant to people of reproductive age and that are recommended as indicators of optimal preconception health and care based on clinical guidance and policy reports. Our review identified a set of 66 preconception indicators across 12 domains covering wider determinants of health and medical, behavioural, social and environmental risk factors. Measures that describe the prevalence of each indicator were formulated based on guidelines and recommendations reviewed and are specific to women or men and high-risk groups where relevant.

Although not all indicators identified in our review are currently recorded in a data source representative of the English population of women and men of reproductive age, 65 of the 66 indicators are assessed and can already be described and monitored at a national level. A measure of preconception health assessment and care is not currently captured in any national data source, and pregnancy intention is not recorded in a routine data set or annual survey. These measures should be considered for inclusion in routine data sets or annual surveys in the future to allow for comprehensive and timely monitoring and evaluation.

For the first time, we describe indicators relevant to men’s preconception health and indicators that can be measured at a national level rather than a local or state level. Indicators were aligned with a range of national data sources, including routine data sets, surveys and cohort studies. The majority of indicators were recorded in at least one routine health data set commissioned by the National Health Service (NHS), which is a government-sponsored universal healthcare system and provider of the majority of care in England. The advantage of monitoring preconception indicators through a combination of these data sources from primary care, hospital, maternity, community and specialist health services is the wide population coverage with information on nearly all residents of England. National surveys and cohort studies complement routine data with indicators on health behaviours such as diet and physical activity comprehensively assessed among large nationally representative samples of the population.

Population-level surveillance indicators for preconception health and care have also been identified in the US by the National Preconception Health and Health Care (PCHHC) Initiative. Reference Broussard, Sappenfield, Fussman, Kroelinger and Grigorescu32 The indicator selection process by the PCHHC Initiative involved a consensus-based selection of 11 broad priority areas (domains), a review of state-based data systems and identification of available measures relevant to each domain. Compared with the domains defined in our review, the PCHHC Initiative did not select environmental exposures, cervical screening, medication and genetic risk as priority areas, but identified self-rated general health status as an additional priority area and separated the health behaviours domain into tobacco, alcohol and substance use and nutrition and physical activity. A total of 96 measures were identified by the PCHHC Initiative, and these were reduced to 45 measures based on evaluation of each measure against predetermined criteria (such as data quality and availability of comparable indicators across states), followed by a Delphi process among representatives from seven participating states to retain or exclude measures. Reference Broussard, Sappenfield, Fussman, Kroelinger and Grigorescu32 The 45 measures have more recently also been evaluated and condensed to ten preconception health indicators Reference Robbins, D’Angelo and Zapata33 and 30 preconception care indicators. 34 This comprehensive consensus building process may explain why the measures identified by the PCHHC Initiative were more restricted compared to our overall set of identified indicators. For example, the PCHHC Initiative indicators were relevant to women only, did not include medication use, immunisation, genetic factors and environmental exposures and captured a limited number of measures to describe wider determinant of health and physical (chronic) health conditions. In line with our review, the PCHHC Initiative also identified preconception assessment and care (preconception counselling) as a relevant indicator. This is not currently reported in national data sources in England, but recorded in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, which is a US state-based survey conducted between two and nine months postpartum among women with a live birth. Reference Broussard, Sappenfield, Fussman, Kroelinger and Grigorescu32

There are some limitations and challenges to our review process and identified set of indicators. First, this is a scoping review and academic/scientific databases were not searched. We aimed to identify indicators based on grey literature including guidelines, recommendations, policy reports and other non-scientific documents from government organisations, national healthcare organisations, professional bodies and societies and charitable organisations. These documents were of interest as they are intended for the public or patients, healthcare professionals and governments, who may directly act on recommendations. These recommendations may thereby result in changes in preconception health that can be measured as part of surveillance. While the comprehensive list of indicators may not be exhaustive, it provides a strong foundation for the development of a preconception health surveillance system in England. Moreover, as evidence and awareness on the benefits of improved preconception health and care continues to grow, it is likely that indicators and measures will expand and be refined over time. Our identified set of indicators will therefore need regular review and updating. Furthermore, the aim of this review was to inform surveillance of indicators that can be assessed at the individual-level and indicators or measures at health service, practice, school, household or family-level were therefore beyond the scope of this review.

A number of indicators identified in our review are not relevant to all women of reproductive age, but are specific to women planning to become pregnant in the near future. Examples include taking a daily folic acid supplement, avoiding vitamin A (containing) supplements and adjusting medication that is not recommended in pregnancy. National routine data sources in England do not currently assess pregnancy intention, although there are moves to include such a measure in the national maternity services data set. Reference Stephenson, Vogel and Hall21 While the National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal) includes a measure of pregnancy intention, this survey is only conducted every 10 years and includes a limited number of other preconception indicators that could be described and monitored among women with planned pregnancies. Until routine data sources include a measure of pregnancy intention, a comprehensive set of preconception indicators cannot be described and monitored separately in women intending to become pregnant. Although data on contraceptive use may provide an estimation of women ‘at risk’ of pregnancy, a better measure to assess pregnancy intention routinely is needed and research is underway to validate such a measure in the UK. Reference Rocca, Ralph, Wilson, Gould and Foster35 Meanwhile, GPs or other primary care professionals can simply ask women “…and are you thinking of having a(nother) baby in the next year or so?”, which can be incorporated as part of routine consultations to identify couples intending to become pregnant. Reference Stephenson, Schoenaker and Hinton36 Since the majority of indicators are relevant to the health and well-being of all people of reproductive age, optimising risk factors may improve pregnancy and birth outcomes if an intended or unintended pregnancy occurs, as well as a woman’s health regardless of a future pregnancy.

In addition to the current lack of data on one indictor, national data sets may be subject to data quality issues. Incomplete data are a common problem, and depending on the amount and reason of missing data, this may result in biased prevalence estimates. Data quality is generally high in, for example, primary care and maternity data sets due to financial incentives to practices and service providers for achieving set targets. However, data from multiple sources may need to be combined to obtain more accurate estimates for some indicators, such as contraceptive use information from primary care, hospital and sexual and reproductive health services data sets. Assessment of indicators may change over time, for example, as a result of changes in quality indicators for primary care, data structures and content requirements for health services, or survey questions. This may impact the accuracy of monitoring of changes in preconception health and care over time.

While acknowledging these potential limitations, surveillance of preconception indicators can be used to provide a snapshot of the health and health behaviours of women and men of reproductive age. When these indicators are stratified by wider determinants of health, they provide an understanding of needs and disparities in health and health care among subpopulations. Researchers may use the overview of indicators to identify outcomes to be targeted and assessed in intervention studies that aim to improve preconception health. Moreover, routine reporting on population-level indicators that benchmark the health of reproductive-aged people can be used to enhance accountability from governments and other relevant agencies for delivering interventions that remove barriers and support all women and men to improve their health. Reference Stephenson, Vogel and Hall21 The importance and utility of preconception health surveillance is further highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, when the prevalence of many indicators identified in this review is likely affected as a result of the stay-at-home advice and changes in access to health care services. 37 Investment in efficient routine data collection and monitoring of population, maternal and child health is recommended to determine the immediate and longer-term effects of COVID-19 and the additional needs of people of reproductive age. Reference Jacob, Briana and Di Renzo38,Reference Roseboom, Ozanne and Godfrey39

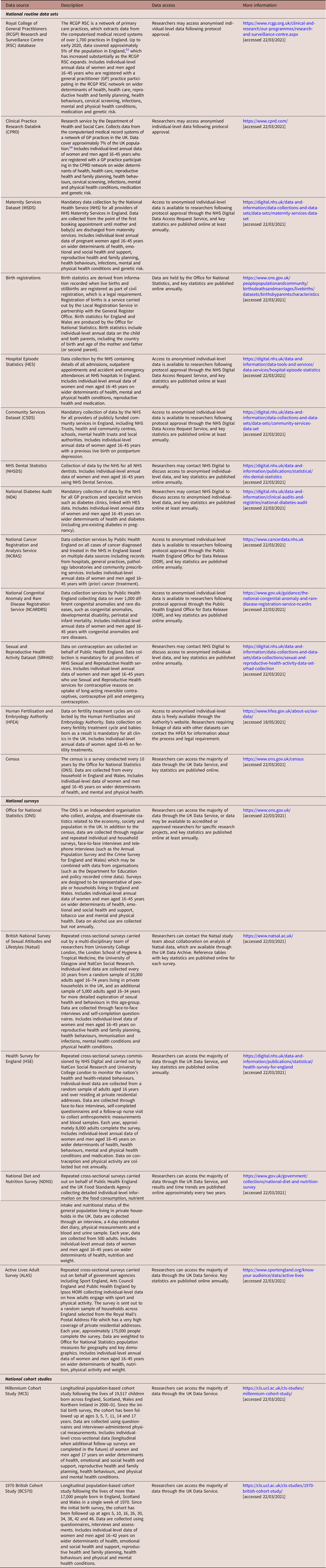

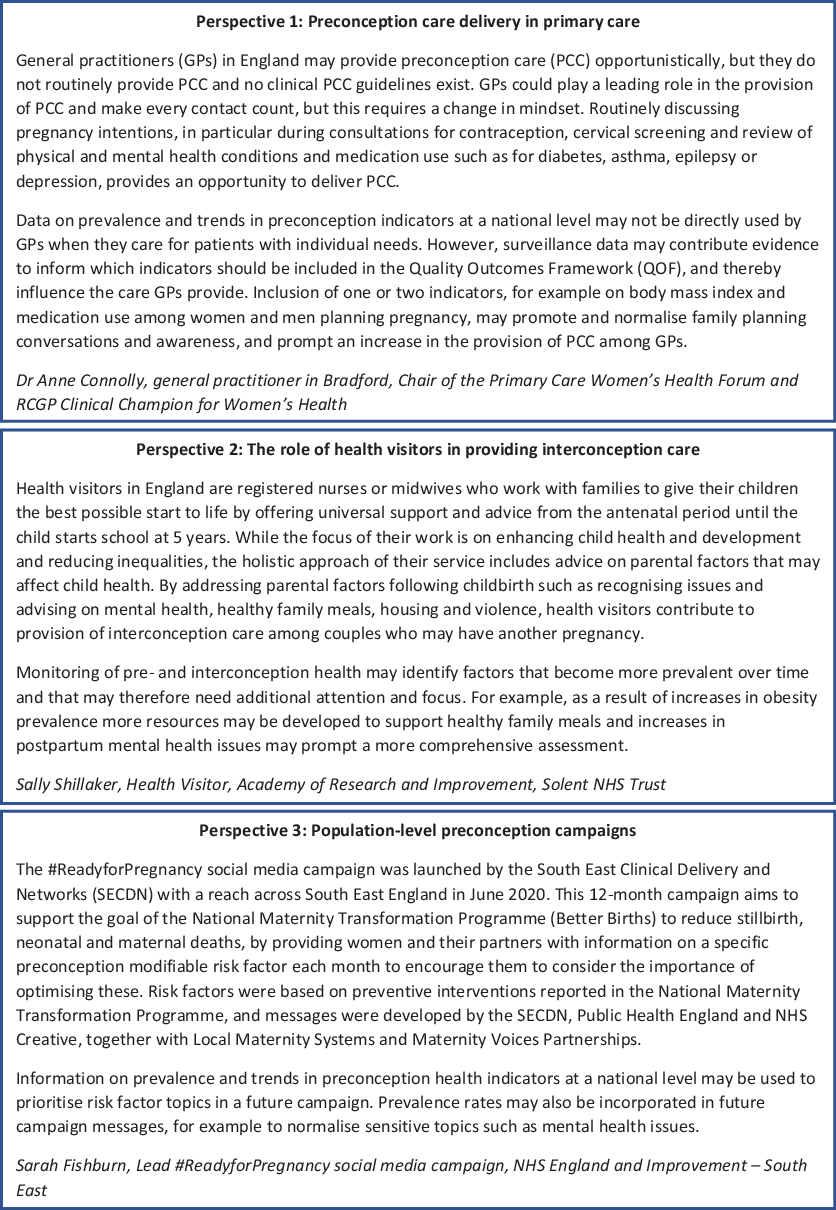

The implications of preconception surveillance extend beyond research and policy advocacy, to directly and indirectly improve patient care and inform the development and evaluation of education and awareness campaigns. Discussions with relevant stakeholders (Fig. 1) revealed that, for example, in primary care, surveillance data may indirectly influence patient care through the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF). 40 This is a voluntary annual reward and financial incentive programme for general practitioner (GP) services in England, in which practices can score points based on achievements against a set of indicators. The QOF does not currently include preconception indicators, but high prevalence or increasing trends may inform the inclusion of specific indicators, and thereby contribute to improved provision of preconception care among GPs. Reference Ma, Cecil, Bottle, French and Saxena41 Moreover, health visitors in England contribute to the provision of interconception care to mothers with infants and young children and their partners. Prevalence and trend data on pre- and interconception indicators may inform risk assessments performed by health visitors and indicate the need to develop resources to address issues that are (increasingly) common and may affect the next pregnancy. In addition to patient care, surveillance of preconception indicators may be used to inform campaign development and evaluation by identifying common indicators that could be targeted and would be relevant to a large proportion of the population. Prevalence rates of indicators may also be communicated to the target population for education purposes and to normalise sensitive topics such as mental health issues.

Fig. 1. Professional perspectives illustrating the value of population-level surveillance of preconception indicators.

The identification of a comprehensive list of preconception indicators and determining their availability in national data sources are a first step towards national surveillance of preconception health in England. Analyses of routine health data sets are currently underway to obtain national prevalence estimates of preconception indicators. Further planned work includes linkage of these data sets to allow analyses of associations between preconception indicators and maternal and child health outcomes to provide evidence on the potential impact of improved preconception health. Our findings on the prevalence of indicators and strength of associations with relevant outcomes – together with considerations of data quality, modifiability and input from stakeholder and public consultations – will inform the prioritisation of a reduced set of key indicators for ongoing surveillance of preconception health in England. A dashboard bringing indicators from multiple sources together through an interactive online platform will make findings readily available to health care providers, policy makers, the public and relevant stakeholders. Informed by the list of preconception indicators presented in this review and by the PCHHC Initiative, we recommend other countries follow a similar process to develop a surveillance system for preconception health based on available regional or national data sets.

Conclusion

Several national and international guideline and policy documents emphasise the need to optimise preconception health to prevent adverse outcomes in the next generation and improve the overall health and well-being of women and men of reproductive age irrespective of any pregnancies they may have. Nearly all preconception indicators identified from these documents can be described and monitored using national data sources in England. Measures of preconception health assessment and care and pregnancy intention are not currently annually recorded in any national data source and should be considered for inclusion in routine data sets or annual surveys in the future. Monitoring of a comprehensive set of preconception indicators may contribute to informing patient care, developing and evaluating public awareness campaigns and strengthening advocacy efforts for government resources and action. This work informs the next steps towards developing a national surveillance system and to improve preconception health in England.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S2040174421000258

Acknowledgements

The UK Preconception Partnership is a coalition of groups representing different aspects of preconception health in women and their partners, including the Royal College of General Practitioners, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, Public Health England, Tommy’s charity and academics in reproductive and sexual health, obstetrics and gynaecology, population health and epidemiology, nutritional sciences and behavioural sciences and education in schools.

Financial support

DS is supported by the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre (IS-BRC-1215-20004). KG is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12011/4), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR Senior Investigator (NF-SI-0515-10042), NIHR Southampton 1000DaysPlus Global Nutrition Research Group (17/63/154), NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre (IS-BRC-1215-20004), the European Union (Erasmus+ Programme ImpENSA) and the British Heart Foundation (RG/15/17/3174).

Conflicts of interest

KG has received reimbursement for speaking at conferences sponsored by companies selling nutritional products, and is part of an academic consortium that has received research funding from Abbott Nutrition, Nestec, BenevolentAI Bio Ltd. and Danone. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.