How is an African continental elite of presidents, diplomats, and bureaucrats making room for war? In the everyday sense, ‘making room for something’ usually relates to furniture, for example. To make room for the new table, the old one needs to be removed. Can the same phrase relate to politics around African-led military deployment for the Sahel? Do the actors take out others to move in? Do they replace one with another? Not quite. It seems obvious that rearranging a room relates to a problem of space, yet actors negotiating military deployment appear far removed from this paradigm. This understanding of ‘making room (for (x))’ rests on an everyday conception of a physical three-dimensional space, a contained space in which objects are situated. Yet in this book I draw on a radically different notion of space – space as relational and changing – and rethink military deployments and geopolitical narratives from this angle. Thinking space relationally remains a challenge, as our everyday thinking and experience is dominated by standard notions of space. ‘Making room for’, from a relational perspective of (social) space, thus means to reshape and alter the relations between actors in such a way that a space is (re-)created. It is not a change in space, but a change of space. This book follows actors as they ‘make room for war’, reshaping relational space in such a way as to make military deployment possible and, at the same time, re-positioning themselves against others.

The use of ‘war’ here is deliberate. It too evokes tension. I came to understand ‘war’ in relation to African-led military deployment during an interview in Bamako in February 2017 about the joint mission deployment to Mali by the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). My interlocutor remembered the period of deployment as the time, ‘when ECOWAS was at war’.Footnote 1 He was referring to the 2013 combat between troops from ECOWAS member states and armed groups in Mali. He spoke plainly, not of ‘interventions’, ‘conflict management’, or ‘stabilization’ as is the norm in the field of African peace and security. The word ‘war’ irritated me. It seemed brutish, unnuanced, and somewhat old-fashioned.Footnote 2 We were talking about a complex multilateral deployment, the first ever ECOWAS-African Union (ECOWAS-AU) mission, the African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA) that was guided by advanced principles for such Peace Support Operations. Yet the terminology obscures armed violence, combat, and military action.Footnote 3 Moreover, the technical-managerial jargon used by professionals in the field of African peace and security camouflages the military dimension and to a greater extent the politics at its core. People draw on common-sense references to space when negotiating who is or is not an adequate intervener. This book exposes the very politics that surround African-led military deployments.

African Military Politics in the Sahel presents an in-depth study of the negotiations taking place around African-led military deployments in Mali and the Sahel since 2012. This is an empirically challenging task, as the intervention landscape in the Sahel has been, and is, in constant flux, at times radically, within a matter of days. Therefore, the focus will be to analyze the more durable dynamics that give power to taken-for-granted notions of space that underpin narratives about the credibility and legitimacy of different interveners. The book analyzes the context-specific constellation of actors that form an interconnected network of elites that shape African military politics. These include presidents, high-level diplomats, and representatives of the commissions of the African Union, ECOWAS, the European Union, and United Nations, as well as bureaucrats and mid-level staff within these organizations. I argue that African military politics are essentially spatial by analyzing what I call spatial semantics to understand how African continental elites legitimize military deployment and (re)negotiated relations among them. The book approaches international politics from a transdisciplinary Global Studies perspective that emphasizes the importance of actors, transregional connections, entanglements, narratives, and context-specific historicity.Footnote 4

The Introduction is in five sections, four of which lay out the themes for this book – military deployment, politics, and space. Section I.1, Le Mali est notre Afghanistan, reveals the blatant ignorance of African-led military deployments for Mali and the Sahel considering an overemphasis on French military deployment and interveners, such as the European Union, United Nations, or United States, and how this disregards the agency of African actors. Section I.2, Studying African Military Politics, introduces the discussions on African-led military deployments that have until now focused on technical aspects and assessments whereas I propose to approach them as part of African military politics. Section I.3, Many Interveners, Many Sahels, draws on abundant references to space that accompany interventions in the Sahel by highlighting different understandings of the area it covers that various actors use to include or exclude others. Section I.4, Rethinking Space: From Fixed Containers to Dynamic Relations, proposes perspectives from critical geography to locate the politics of African-led military deployments in the Sahel and argues for the value of analyzing what I call spatial semantics. The final section of the Introduction, Section I.5, provides a road map to the book.

I.1 ‘Le Mali est notre Afghanistan’

On the developments in Mali, an article title in Le Monde announces ‘Le Mali est notre Afghanistan’.Footnote 5 This suggests that the French military engagement against armed groups in Mali is of a similar ilk to that of the United States in Afghanistan. It implies a strong and singular relationship that not only objectifies the country that is intervened in but also obscures the multitude of other actors engaged in conflict responses by reinforcing the image of a white Western intervener. Whereas my aforementioned interlocutor remembered early 2013 as the time ‘when ECOWAS was at war’, another completely denied that was the case. When I requested a meeting with a French national in 2017 to talk about the 2013 ECOWAS-AU deployment, the blunt response was that there was ‘no African intervention to speak of’ and thus no need for a meeting.Footnote 6 This ignorance of the African intervention experience in Mali is longstanding and continuous. Already, at the time of the deployment of AFISMA in January 2013, the media coverage’s focus lay with the Franco-Chadian Operation Serval.Footnote 7 Violence had escalated in the north of Mali since 2011.Footnote 8 A coup d’état followed by an attempted secession in spring 2012 and a subsequent advance of armed groupsFootnote 9 southwards triggered the involvement of ECOWAS, the African Union, and eventually the United Nations and more international non-African interveners – most notably France. While the French-led intervention was covered extensively, the African troops were only mentioned in passing or at the end of news items and even then, mostly with reference to the Chadians that deployed within Serval. The image of France as the ‘intervention champion’ in Africa was once again reinforced and extensively discussed in the literature.Footnote 10 Whether lauded as a success story of ‘hunting jihadists’ or condemned as ‘a form of neo-imperialism’, discussions over Operation Serval eclipsed the African-led military deployment.Footnote 11 This neglect deepened after the (mainly West) African troops deployed under AFISMA were officially re-hatted under the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) on 1 July 2013. Eventually the conflict interventions in Mali were mainly narrated in terms of two successive French deployments (Operations Serval and Barkhane), the United Nations mission MINUSMA, and two European Union training missions as well as an ever-expanding landscape of further non-African development and security interventions. This stopped after successive military takeovers of power in 2021, the invitation of Russian mercenaries by the military leadership and subsequent withdrawal of French troops. The last French soldiers left Mali in August 2022 amid a resurgence of jihadist armed groups.

Those willing to see African agency in multilateral interventions for Mali and the Sahel have discussed the deployment of AFISMA and its implications for the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), the African Union’s flagship policy programme to foster stability, security, and peace on the continent.Footnote 12 Still, AFISMA was discussed primarily in terms of its flaws. As Kasaija P. Apuuli reflects: ‘The Malian crisis more than any other, exposed serious shortcomings in the APSA.’Footnote 13 This sentiment of a failed African engagement in Mali, while the French-led Operation Serval was hailed for its quick military successes, triggered strong responses in 2013 – the year that the African Union celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of an independent continental organization.Footnote 14 While the cumbersome process to develop AFISMA had already created tension between ECOWAS, the African Union, and the United Nations, the aftermath of the deployment triggered a competition among African leaders over who was best suited to lead military deployment in the Sahel – and could claim leadership in maintaining security on the continent. The African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crises (ACIRC) was introduced by the African Union Commission (AUC, or commission) chairperson Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma and lobbied for by then South African president Jacob Zuma. The Nouakchott Process Intervention Force in northern Mali was proposed by the commission and representatives from eleven member states in the Sahelo-Saharan region facilitated by the Algiers-based African Union African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism (ACSRT/CAERT). Eventually, the presidents of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger proposed, as members of the newly established regional organization G5 Sahel, a Joint Force to be deployed against ongoing violence by armed groups in the Sahel.

Far from being a nullity or minor glitch in international relations – as the aforementioned French interlocutor implied – the ECOWAS-AU mission in 2013 is an African intervention experience with far-reaching consequences for international politics on the continent. The African Union and ECOWAS were sidelined in the quest to find lasting peace in Mali and the Sahel once the United Nations took over their mission and more non-African interveners entered the fray. Denying the history of this ECOWAS-AU mission, AFISMA, echoes white supremacist attitudes and European paternalism. It is an obstacle to a sustainable European–African partnership in conflict resolution and ironically fuels anti-Western and anti-French sentiments in the region. Foregrounding African-led interventions is by no means meant as an idealization of African interveners. Interventions by ECOWAS and the African Union have their own pitfalls and are perceived in complex ways by local populations.Footnote 15 Still, sustainable international support to the conflict areas in the Sahel can only be developed if the full intervention picture is acknowledged. This book is a step in that direction. It is essential ‘to speak of’ these (AFISMA and others) African interventions and not simply accept their existence. The interventions teach us how Mali and the Sahel were spaces claimed by African actors as part of their foreign policies and geopolitical ambitions. This is a highly political terrain fought over with weapons and words within African military politics.

I.2 Studying African Military Politics

The prism of African military politics captures the multitude of negotiations by an African cosmopolitan elite before, during, and after military deployment at the level of continental African politics – with its embeddedness in the international system. The actors involved include inter alia heads of state, ministers, diplomats, and bureaucrats from regional organizations. These negotiations take place in civilian and diplomatic settings, yet their objective is military action. Moreover, the actors involved often have either some background in military training or come from a political national environment that is co-constituted by the military dimension. In most West African countries, for example, the military continues to play an immense role in shaping politics even in civilian-led countries and as the recent wave of military coup d’états in Mali, Guinea, and Burkina Faso show, the military is still very much at the forefront of governing these societies. This impacts the tone and shaping of policies at the level of international organizations, such as the African Union. Research on militarism has studied civil–military relations at the national level, dynamics behind military coup d’états, and the phenomenon of rebel governments.Footnote 16 This book contributes to these lines of inquiry by showing how military action and reasoning is pursued in international organizations by actors in suits rather than uniforms.

Literature on African-led military deployments has focused on African Union Peace Support Operations, but recently also on ad hoc military deployments. These debates have been largely empirical and often shy away from embedding these deployments in wider continental international relations. In the following, I want to highlight two implicit biases that continue to shape debates about African-led military deployment in academic and policy circles. The first bias is an overreliance on single-case studies and methodological nationalism inherited from the analytical frames of political science and international relations. The second bias finds expression in a narrow interest in outcomes, successes or failures stemming from managerial logics in the security-development field. In contrast, I propose to approach these deployments as embedded in African military politics and to draw attention to the actors involved in their establishment, that they are part of political projects driven by national and continental elites to further their own ambitions, and that they form part of a larger process of shifting paradigms for military intervention.

Scholarly interest in African Union Peace Support Operations has grown in parallel to the number of deployments since the early 2000s.Footnote 17 Earlier missions in the ComorosFootnote 18 and along the Ethiopian–Eritrean border areaFootnote 19 received scant attention, while later missions have sparked significant interest. The 2003 African Union Mission in Burundi was later handed over to the United Nations which started discussions about the different roles of the two organizations as intervening actors.Footnote 20 Also, during the intervention in Sudan, from 2004 onwards, the African Union had to align its actions with the United Nations, and also the regional organization Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD).Footnote 21 The African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) 2007–2022 has been studied in detail in particular, regarding different intervening actors or the interests of different troop contributing countries that deployed and neighbouring countries.Footnote 22 As in Mali, in the Central African Republic (CAR), the African Union had to coordinate its response with the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the responsible regional body, as well as the United Nations and French troops (here under Operation Sangaris).Footnote 23 The discussions around AFISMA, the ECOWAS-AU deployment in Mali, acknowledged the months-long struggle to find a mandate and assessed the logistical problems.Footnote 24 While ACIRC was addressed in heated terms,Footnote 25 the other response to the ECOWAS-AU intervention experience in Mali, the Nouakchott Process, received little attention.Footnote 26 Moreover, military deployments such as the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF)Footnote 27 and the G5 Sahel Joint Force,Footnote 28 while first introduced as ad hoc mechanisms, were later also seen as part of APSA.

Many of the studies on these deployments focus on technical, logistical, planning, and implementation issues, yet some emerging literature focuses on the international politics surrounding the deployments as well as interpersonal aspects that are often only accessible through more anthropological or sociological approaches.Footnote 29 Thomas Kwasi Tieku began to highlight the impact of commonplace aspects like per diems in shaping the outcome of peace talks that are supposed to be supported by such deployments.Footnote 30 He developed this work on informality in African international relations into a coherent study of informal international practices.Footnote 31 The political dimension of these interventions has been discussed regarding the agency of troop contributing countriesFootnote 32 and the entanglements with their foreign policy, in particular as part of regional coalition-making, as well as the local politics in response to them.Footnote 33

The study of African-led interventions, APSA, and the field of African peace and security, is seeking better ways to understand this social phenomenon and establish greater scholarly independence by defining more theoretical and conceptual interests.Footnote 34 Nevertheless, some biases in the way these topics are discussed linger. In this field of study, approaches and interests for research are in close contact with debates among decision-makers, practitioners, and consultants, mediated through think tanks and government-affiliated research institutes. This means interaction between scholars and a range of actors that are involved in these missions – though not all, as local populations remain largely disconnected.Footnote 35 Against this background, I want to consider two interrelated biases that shape the ways of approaching these deployments.

The first point of caution regards the tendency to study these deployments with a mere interest in assessing their success or failure, often hinged on questions regarding mandate fulfilment, number of casualties, deployment speed, airlift capacities, logistics, and other technicalities. While relevant, it obstructs reflection on the larger implications of such interventions, like who benefits and what order they are trying to uphold, as Marta Iñiguez de Heredia has cautioned by tracing colonial patterns in contemporary stabilization missions in Africa.Footnote 36 Deployments are not studied as phenomena in their own right, but with a particular interest and normative direction. This is connected to a problem-solution logic. These thought patterns need to be seen in a context in which professionalism often collapses into neoliberal managerialism affecting both the military and the development field that impact African peace and security. Managerial logics have permeated the military realm in the United States and other Western armies at least since the Vietnam War, but the imperative to ‘measure progress’ has intensified since the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in the 2000s.Footnote 37 As many African national and multilateral forces receive training from these nations, and according to these ‘international’ or ‘Western’ standards, such logics enter the military community there too. These same logics are also rampant in the development sector with project management cycles and external evaluators as well as regarding United Nations peacekeeping missions. The cynicism of a managerialism that has extended beyond the realm of private enterprises in a near totalitarian fashion is most visible in the idea of conflict management.Footnote 38 Regarding African peace and security, the largely donor-funded policy community wants to know whether the ‘problem’ can be fixed, and how and what would fix it faster. This direction of inquiry isolates deployments from their political context and studies them as isolated occurrences, but studies them only according to a limited interest and not as part of historical processes or as expressions of contemporary politics. Such inquiry obscures the politics and, as such, those that form them ignore a wide array of actors and their agency in shaping these deployments.

Related to this is the second point of caution, the overreliance on ‘case’ studies, either as isolated single cases or in rigid comparison of multiple cases, an analytical frame of mind stemming from political science. This tradition of thought developed alongside the formation of a historically contingent model of a nation state in Europe and North America and attempts to efficiently govern these societies. The subfield of international relations has in particular in its US-dominated traditions borrowed a lot from this, including methodological nationalism, positivist approaches, a disregard for concrete actors (people), or if it includes them, then in simplistic rational-choice frames. This had methodological implications. (Natural) Science imitating approaches have led to a labification, as if aspects could be isolated and analyzed under ‘sterile’ conditions. This anxiety around the messy conditions of the social finds expression in single-case and multi-case studies. Single-case studies mostly fall prey to methodological nationalism and isolate these deployments from their inter- and transnational political contexts. Multi-case studies often conceptually isolate different deployments comparing them according to different factors with the different case selected according to their differences or similarities (for example, in Most Similar Systems Design or Most Different Systems Design).

These two points of caution are interconnected. The techno-managerial mindset that sees neither politics nor socio-historical specific context begs for epistemologies that follow this and deliver. The political science traditions have had a great impact on the reasoning underpinning many studies. A Global Studies perspective, that is decidedly transdisciplinary, breaks open such dead-end reasoning by drawing inter alia on history, anthropology, and cultural studies and bringing the study of international politics into the domain of humanities and interpretative inquiry and looks for better understanding of meaning rather than exploring assumed causal mechanisms as in a science-envy social science tradition. Instead, scholarly focus is on (historical) processes, the study of political projects of concrete actors, and in tracing entanglements and transfers.Footnote 39

Here, African Military Politics in the Sahel enriches the debate on African-led military interventions and African peace and security by contributing an in-depth study of the interplay among different actor groups shaping these deployments.Footnote 40 In so doing, such military interventions are situated within African international relations,Footnote 41 specifically the negotiations of relations between member states, the African Union, and regional organizations. In this context, the role of bureaucratic actors of regional organizations in shaping international politics is important, like the bureaucrats and diplomats at commissions or country (liaison) offices.Footnote 42 The role of African presidents is undisputed in negotiating for and carrying out military deployments, and their considerations in sending troops has been discussed.Footnote 43 Nevertheless, their influence is met by the actions of bureaucrats at the international organizations they have to engage with to deploy troops. The emphasis on actors and their (inter)relations allows us to understand African-led military deployment as an experience in an ongoing process of the formation of political relations and intervention paradigms.

Building on studies on the history of African-led military action,Footnote 44 this book incorporates historicity by tracing the becoming of these norms and practices for military intervention in a particular conflict context over the decade since 2012. It provides, however, a more short-term perspective against a longer historical process of the development of independent African military capacities. Drawing on Global Studies approaches on transnational history, cultural transfers, and entanglements – rather than on a political science–style comparison – I relate different deployments by tracing the entanglements among them as different experiences that shaped the actors involved and impacted decisions on other deployments. Accordingly, particular attention is paid to seemingly ‘unsuccessful’ proposals that were never deployed (for example, MICEMA, ACIRC, and the Nouakchott Process Intervention Force), as they allow a better understanding of the negotiations involved.

I focus on the many actors involved in developing these deployments, from presidents and diplomats to commission bureaucrats and consultants, the negotiations involved in shaping them and their entanglements with other deployments in a larger process casting paradigms for military engagement. By concentrating on actors, politics, entanglements, and processes, these deployments need to be approached as part of African military politics. This allows comprehensive recognition of their significance in Africa’s international relations,Footnote 45 in shifting military paradigms on the continent, and in the changing relations between actors from member states, regional organizations, and the donor and partner community.Footnote 46

The different actors, relations, negotiations, and processes are in this way part of the politics that these African-led military deployments are embedded in. African Military Politics in the Sahel uses the prism of African military politics to deepen the appreciation for this. While this prism may seem placative, it helps highlight the military dimension in African Union and continental politics. The African Union’s peace and security policies have become too reliant on the military dimension. Throughout its development, the police and civilian component of the ASF have been neglected in favour of the military component.Footnote 47 Linnéa Gelot questioned if the African Union’s decisions ought to be seen as part of a militarization, while Toni Haastrup has exposed some of them to be part of martial politics.Footnote 48 Rita Abrahamsen asked if we have seen a ‘return of the generals’ in African peace and security policies.Footnote 49 As this book will argue, military engagements are used to shape relations among member states as well as with non-African actors. While unity in the continental military realm has been advocated since independence, as in Nkrumah’s proposal for the African High Command, this was always complemented by nationalist ambitions for a favourable repositioning on the continental political landscape. With increasing involvement of African troops in peacekeeping, this has had implications for relations on a global level, for instance in late Idriss Déby’s use of contributions to peacekeeping to boost his international reputation and tone down criticism for his authoritarian rule in Chad. The Ugandan engagement in AMISOM under Yoweri Museveni should be framed similarly. Yet even less controversial military engagement is geared towards showing international stamina as in the competition for a non-permanent seat at the United Nations Security Council – or a permanent seat if this should be established through reform of the Council. Similar dynamics have played out on the regional level. Here, the difficult negotiations in forming the regional forces for the ASF come to mind, especially those in East and North, which resulted in tensions. The notion of African military politics as I use it rests on a relational understanding, constituted by interactions between – in a rough simplistic dichotomy of identity – African and non-African actors. This is of course notwithstanding a relational and dynamic understanding of identities. This notion attempts to move beyond the chasm between essentialist (a-temporal) designations of ‘African politics’ linked to accusations of neo-patrimonialism and failed states debates or universalizing (and thus often Westernizing) misconceptions of a mere ‘politics in Africa’. Nevertheless, the latter introduces the nuance of a specific context. The answers to what African military politics are can only be empirical, can only be contextual, in a historical political specificity, rather than being defined they can be located. While they include different aspects, this book reconstructs a particular set of moments that reveal them in the negotiations and debates around African-led military deployments for the Sahel since 2012.

I.3 Many Interveners, Many Sahels

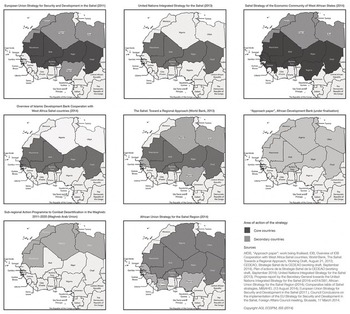

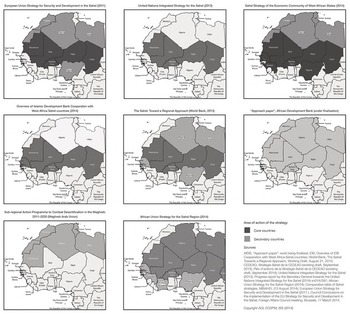

After April 2012, when ECOWAS began to respond to armed violence in Mali, and after the re-hatting of the ECOWAS-AU mission to the United Nations mission in July 2013, Mali and neighbouring countries saw an influx of international (non-African) actors seeking to intervene. Each organization, each intervener entered the area with their own understanding of where the Sahel is. Concepts about where the Sahel is, its extent, its problems, and how best to address them have often been expressed by way of ‘Sahel strategies’. The Institute for Security Studies (ISS) and the European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM) took stock of these strategies in 2015, counting at least eleven.Footnote 50 The image here indicates the variety of different ideas of where the Sahel is:

Figure I.1 alludes to the variety in ‘Sahels’ that different organizations brought to the intervention landscape, yet these representations are from the larger interveners and date back to 2011. In the years since, initiatives and actors have multiplied. The Sahel Alliance was formed in 2017, spearheaded by France and Germany.Footnote 51 During the August 2019 G7 Summit, these two countries launched the Partnership for Security and Stability in the Sahel (P3S), and in January 2020, fresh impetus was given through the International Coalition for the Sahel by the presidents of the G5 Sahel and France. These are the most prominent frames introduced by two powerful external actors in the region. Yet all of this shapes and produces the ‘West African region’ as well as the ‘Sahel’.Footnote 52

Figure I.1 Sahel strategies as compiled by the ISS and ECDPM, 2015.

It is not only the location for intervention that is constructed via spatial semantics but also the suitable frame for intervention that is justified through spatial semantics. Who is deemed the appropriate intervener and who is included or excluded in a deployment is also negotiated through references to space (see Table I.1). Initially, AFISMA (Chapter 2) began as a regional mission composed by ECOWAS as MICEMA, but was eventually transferred to a joint ECOWAS-AU mission with many discussions over who, where, and why fought on the basis of different interpretations of the principle of subsidiarity. By contrast, ACIRC (Chapter 3) was designed as non-regional, without reference to any of the pre-existing regions under APSA and the ASF. Instead, it was based on framework nations, a group of like-minded and willing and able member states. Borrowing much of its terminology and reasoning from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), it was a first indicator of a trend towards military coalition, becoming much clearer later during the deployment of the G5 Sahel Joint Force. The proposal for the Nouakchott Process Intervention Force (Chapter 4) by contrast was supposed to deploy within a transregional frame; planning and troop sourcing would have been established by the Nouakchott Process in the form of the Sahelo-Saharan region that spans north, west, and central Africa. It bridges three existing regions under the ASF geography. The G5 Sahel Joint Force (Chapter 5) deployed in a newly established regional frame that disregarded the pre-existing security regions in the area, most notably ECOWAS and ECCAS, and was deployed by the five member states of the G5 Sahel based on the members’ understanding of where the Sahel was and who was part of it.

| Proposed deployment | Spatial semantics | Intervention paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA) | Subsidiarity, Joint Mission, ‘saving neighbours’ | Regional deployment, Continental deployment |

| African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crises (ACIRC) | Framework nations, coalition of the willing, lead-nation | Non-regional deployment |

| Nouakchott Process Intervention Force | Sahelo-Saharan, Transregional, Bridging ASF regions | TransregionalFootnote a deployment |

| G5 Sahel Joint Force | Sahel, regional coalition | Re-regional deployment |

a This is different from the term ‘transboundary deployment’ as discussed in Latham et al., “Introduction.”

References to space have been a powerful resource in justifying the preferred choice for military action by different actors. The ‘problem’ and the ‘solution’ are narrated in terms of space. Both conflict and conflict intervention are communicated in the form of spatial semantics with consequences for the intervention that follows. In Section I.4, I will expand on this by introducing a theoretical shift in the way we conceptualize space that allows us to analyze the politics at play around African-led military deployments and to understand how they are essentially spatial.

I.4 Rethinking Space: From Fixed Containers to Dynamic Relations

Rethinking space as relational is vital to understanding the role of space in politics, which is crucial under the global condition.Footnote 53 It allows better comprehension of how courses of action are negotiated, how alliances are formed, and how animosities are conveyed through the production of distance, proximity, locality, regionality, globality, or other spatial relations. In recent years, the core premise of the so-called spatial turn in the humanities, that space is an essential dimension to understanding social phenomena, has slowly been adopted by scholars of African peace and security.Footnote 54 In this book I argue that African military politics are essentially spatial and need to be studied as such. Consequentially, I insist on a rethinking of our everyday conceptions of space from one of representational space or the imagination of space as fixed containers to one of relational space. Drawing on critical geographer Doreen Massey, I introduce the study of spatial semantics as a valuable approach to understanding the concrete co-constitution of space and politics. In Massey’s For Space, she introduces her understanding of relational space by way of three propositions.

The first proposition encourages us to think of ‘space as a product of interrelations’ and to guard against essentialist readings of space.Footnote 55 This allows us to understand the significance of places like the AUC as constituted by the myriad of relations between actors that come into contact there. This resonates with the analysis of portals of globalization as developed in Global Studies, which allows the analysis of places in terms of the interactions and contact that they allow among actors.Footnote 56 Ulf Engel has studied with great success the AUC as a portal of globalization highlighting how it allows for the making and un-making of interrelations.Footnote 57 Emphasizing the interrelations that produce space and arguing against essentialist readings of place and space does not mean neglecting specificities or context. This profound relational understanding also underpins my use of ‘African’ in African military politics that highlights that we can talk about something specific in the way military deployments are negotiated on the continental level, while renouncing that this is something ‘native’, atemporal, or unchanging. Rather it is in each moment of observation something specific to this space and the relations as produced by a particular group of actors. African elites have often been denied this role in space making, an issue that Chapter 6 discusses in more detail by arguing to reposition this group of actors within critical geopolitics.

The second proposition highlights ‘the existence of multiplicity’, of difference and heterogeneity.Footnote 58 Massey urges us to ‘recognise the simultaneous coexistence of other histories with characteristics that are distinct (which does not imply unconnected)’.Footnote 59 Conceptualizing space as the realm of multiplicity that allows for a simultaneous and immediate plurality grants the analysis of the 2013 ECOWAS-AU mission in Mali as a distinct intervention experience. This distinct experience is not isolated from other such deployments – most obviously the French-led operation. The intervention presents a (hi)story that was fully experienced and is remembered by those involved – for example, ECOWAS and African Union staff and representatives. When considering the disregard for this African intervention experience, the importance and strength of appreciating multiplicity becomes apparent. Chapter 2 digs deeper into the intervention experience around the deployment of AFISMA.

The third proposition is a reminder to imagine space as ‘always in process’, as always becoming.Footnote 60 Conceptualizing space as becoming (in an open process) allows us to analyze the three different proposals to African-led military deployments that were introduced after the ECOWAS-AU intervention experience in Mali as part of an ongoing process, the becoming of paradigms for military intervention. New relations are formed, some relations are consciously avoided, and others discontinued. The proposal for ACIRC, for example, omits the connection to regional organizationsFootnote 61 and directly relates member states with the ability and will to deploy militarily under the African Union Peace and Security Council. The Nouakchott Process, however, maintains the importance of regional organizations under APSA and for the African Standby Force, but repositioned Algerian-led institutions as a pivotal point in relation to security in the Sahel – and Mali. The G5 Sahel neglected Algeria instead, but also ECOWAS and the African Union (at least in the beginning) and focused on strengthening the relations between the five member states as well as with France and, their great supporter, the European Union. How actors shape this process through spatial semantics will be investigated in Chapters 3, 4, and 5.

But how are these relations changing? Taking an actor-centred approach, I look at how actors shape these relations by analyzing spatial semantics. Spatial semantics as patterns of meaning-making are employed by actors in numerous ways to pursue their political ambitions, goals, and interests – at times without them being aware of it. The value of analyzing spatial semantics lies in the ability to highlight the spatiality of social relations.Footnote 62 A consequence of the techno-managerial environment (as pointed out in Section I.2) surrounding African-led military deployments is a highly specialized technical language used by professionals in the field of African peace and security. This technical realm seemingly void of politics has established orders; this technical apolitical language is one way of maintaining them. The practice of decision-making, consulting the medical expert community without parliamentary negotiations during the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, are expressions of formal politics that take an apolitical managerial form. Far removed from those affected by the decisions, this mode of decision-making depends on a political elite and a community of experts.Footnote 63 Despite lacking an electoral mandate, financial or military assets, experts wield significant power, derived from defining, envisioning, and narrating reality. The community of experts, bureaucrats, and decision-makers surrounding African-led military deployments communicates based on a shared technical language. The objectives of individual actors are negotiated through this jargon and by using a depoliticized idea of (representational) space – as unchanging, given, obvious, and common sense. Tracing expressions of this and analyzing them as spatial semantics allows the moment to be identified where space is invoked, maintained, and reproduced to further the aims of individual actors. Analyzing spatial semantics allows the tapping into the obvious, non-negotiable, accepted underlying assumptions about space that are harnessed – consciously or unconsciously, but with strategic intuition – to pursue the re-negotiation of relations among actors, while debating seemingly technical aspects for mission planning. Thus, spatial semantics distances the technical professional jargon and uncovers the political dimension within international bureaucracies.Footnote 64

I.5 Road Map to the Book

The book contends that African military politics are essentially spatial. As African-led military deployments in the Sahel are negotiated in and through social space, actors ‘make room for war’ when they negotiate who is ‘close’ or ‘distant’ to a security concern, who is a legitimate intervener, and who is included or excluded in a common military response. They do so by invoking seemingly neutral assumptions and naturalized narratives about space. African Military Politics in the Sahel exposes and analyzes these subtle references as ‘spatial semantics’ and offers a critical reading of their use in the politics surrounding African-led military deployments. Spatial semantics enable actors to bypass open confrontation by using ‘merely geographical’ arguments in pursuit of their political projects and objectives. Through this, actors negotiate both the military deployment and the relations with one another. Yet the use of spatial semantics is not necessarily conscious, but rather an intuitive strategy. Thus, a socio-spatial perspective reveals competing or complementary political projects, but also grants an understanding of how policies and ideas about space co-constitute each other.

The book studies the negotiations that took place around African-led military deployments in Mali and the Sahel since 2012. It analyzes taken-for-granted notions of space in narratives about the credibility and legitimacy of different interveners. Furthermore, the book considers the context-specific constellation of actors that form an interconnected network of elites which shape African military politics. These elites include presidents, high-level diplomats, and representatives of the commissions of the African Union, ECOWAS, the European Union, and United Nations, as well as bureaucrats and mid-level staff within these organizations.

The book exposes how these continental African elites draw on spatial semantics to legitimize military deployment and how relations between different actors are (re)negotiated in the process. As references to space abound, analyzing them as spatial semantics allows an understanding of how they are used by actors intuitively and strategically to make truth-claims about space that enable them to communicate, but also (de-)legitimize specific political projects. Spatial semantics are the particles or phrases that charge an expression with space-related meaning. The book analyzes the significance of prevalent spatial semantics such as ‘Sahelistan’, ‘territorial integrity’, ‘West Africa’, ‘Sahel’, or ‘Sahelo-Saharan region’ in the lobbying for different African-led military deployments.

The analysis focuses on AFISMA, the joint mission by ECOWAS and the African Union in Mali (Chapter 2), the proposal for military deployment through ACIRC (Chapter 3), the Nouakchott Process Intervention Force (Chapter 4), and the G5 Sahel Joint Force (Chapter 5). The chapters highlight the respective actors driving these military initiatives and the spatial semantics employed in negotiating the deployments as well as the relations among actors.

Both proposals for military action that were only discussed at a certain point in time, as well as those that ended up being deployed, are included in the analysis. In contrast to studies with a bias towards projects that were implemented, this explicit inclusion of initiatives that were not deployed enables a comprehensive analysis of the processual character of negotiations for military deployment and thus to fully appreciate the extent, and limits, of spatial semantics in African military politics.

The empirically grounded book presents an interpretative qualitative analysis based on 2,054 documents and 143 narrative interviews collected during repeated research stays in Addis Ababa, Abuja, Bamako, Berlin, Brussels, New York, Ouagadougou, Stockholm, and Washington from 2016 to 2020 (see Appendix for details on material and sources). The 143 interviews were conducted alongside several more informal and off-the-record conversations with staff, representatives, and diplomats at the commissions and secretariats of the different organizations, at liaison and country offices, at national ministries and embassies as well as with researchers at think tanks. The interviews were largely narrative with a topical focus on specific technical or political issues. Some were conducted in a semi-structured manner, when the informants preferred a conversation guided by a set of questions. In addition, a research journal was kept to collect observations from participatory encounters.

The textual material that the book is based on consists of archival material from ECOWAS and African Union archives and libraries, based in Abuja and Addis Ababa respectively; on official documents published in open online repositories of ECOWAS, the African Union, European Union, and United Nations; on speeches and communiqués published by national governments; on social media pronouncements (for example, Twitter); and media sources accessed through AllAfrica.com (a website publishing aggregated news from African newspapers) and the Europe Media Monitor. From these sources, visual material was also collected including press photos, icons, images, maps, and organigrams that were analyzed with an interest in the imaginations about, and representations of, space that they transport.

Chapter 1 provides the theoretical framework of the book and introduces the analytical category spatial semantics weaving in empirical illustrations to ground abstract discussions. The chapter first introduces the policies that underpin multilateral African-led military deployment, specifically APSA with its ASF and African Union Peace Support Operations. It illustrates that these are ripe with references to space, like the idea of an ‘architecture’; the idea of a hierarchical division of labour among different regional and international organizations as formulated in the principle of ‘subsidiarity’; or the idea of a division of the ASF into five regional forces on the continent (each for ‘north’, ‘east’, ‘south’, ‘centre’, ‘west’). However, these implicit references to space reveal a representational understanding of space – that is, of space as fixed, two-dimensional, and static. This is most apparent in organigrams used for visualizing, planning, and implementing different policies and institutions. They manifest imaginations about relations among actors and the spatial organization of security on the continent. To expose the political dimension in this, space needs to be studied as relational and changeable. Reconceptualizing space as relational, open and up for negotiation or fluid, folding, and topological raises the question of who is (re-)shaping space, why, and how. Critical geopolitics has advanced the analysis of geopolitical narratives and studied how political and intellectual elites (re-)produce ideas about space. Regarding African-led military deployment, these elites include inter alia presidents, government representatives, military personnel, diplomats, and bureaucrats at international organizations, and actors from the donor and partner organizations as well as the policy community. Drawing on the study of narratives and their transnational entanglements in Global History, as well as the history of ideas and conceptual history as associated with Reinhart Koselleck, I introduce the analytical concept ‘spatial semantics’. Spatial semantics are words, particles, or phrases that charge an expression with meaning and imaginations linked to space. They are prevalent in communicating ‘common-sense’ ideas about space or ‘merely geographical’ arguments that allows disguising of political ambitions in including or excluding actors, in (de-)legitimizing actors and actions, or in producing proximity or distance. As the meanings and arrangements for African-led military deployments are negotiated within socio-spatial relations, political relations between different actors are re-negotiated during and after intervention experiences. Spatial semantics are the vehicle for that. While actors may not necessarily use these references to space consciously or deliberately, they do so intuitively and often skilfully. Only when moving ‘beyond the architecture’ in studying APSA, by analyzing the spatial semantics that surround African-led military deployment, is it possible to expose the politics involved.

Chapter 2 discusses the first of four African-led military deployments, AFISMA, the struggle for its mandate, and the role of spatial semantics throughout. Despite the disagreements over the right frame for deployment, there was a shared understanding of the security concerns in Mali. These included the coup d’état and secessionist attempts in early 2012. Prominent spatial semantics involved in characterizing the situation were the concern for Mali’s ‘territorial integrity’, which was amplified by narratives about ‘ungoverned spaces’ and consequentially ‘save havens’ linked to transnational organized crime and terrorist activities and eventually a diffuse fear of a potential ‘Sahelistan’ in the making by jihadist armed groups. Despite a shared understanding of the security concerns in Mali, different understandings on the best way forward were expressed from within ECOWAS, the African Union, and the United Nations Security Council. Discrepancies centred on who was best suited to lead an intervention. Chapter 2 analyzes how the initial proposal for a deployment of the ECOWAS Standby Force, later that for the Mission de la CEDEAO au Mali (MICEMA), and eventually for AFISMA, was lobbied or refuted, by whom, and with which references to space. Special attention is paid to the principle of ‘subsidiarity’ that is supposed to order the relations and legitimacy among ECOWAS, the African Union, and the United Nations and the dispute over the regional limits of a response by ECOWAS that had to address Mali’s non-ECOWAS neighbours, Mauritania and Algeria. In analyzing the deployment of AFISMA and debates around the re-hatting to MINUSMA, a story about the marginalization of certain actors is brought to the fore that reveals how different actors repositioned themselves towards one another and security concerns in Mali. While Nigeria led the initial deployment of AFISMA and staffed the position of troop commander, it was former Burundian president Pierre Buyoya who took the post as Head of Mission of AFISMA despite the initial lack of Burundian troops in the mission. Instead of a West African ‘neighbour’, an ex-president from outside the ‘region’ became the representative of this African-led military deployment. Later, he became the African Union Commission’s candidate for heading MINUSMA, yet Albert Gerard (Bert) Koenders of the Netherlands took up the post instead. This experience for (West) African decision-makers having their Malian ‘neighbours’ saved by ‘strangers’ has impacted subsequent debates on who is responsible for security in the Sahel, who is seen as legitimate intervener, and who is best equipped to take military action. The chapter ends by situating the African intervention experience in Mali amidst discussions of a delayed – or even failed – deployment of AFISMA that exposed shortcomings within APSA and provided fertile ground for introducing alternative frames for African-led military deployment, which are discussed in later chapters.

Chapter 3 uncovers how a South African political and military elite around President Jacob Zuma took the opportunity to lobby for the establishment of ACIRC. In early 2013, this momentum was created when debates about delays and shortcomings of the joint ECOWAS-AU deployment in Mali surfaced alongside widespread praise for the French intervention in Mali – just ahead of celebrations marking the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity, the African Union’s predecessor. Yet, within the AUC, Zuma was able to rely on technical and procedural support from the Chairperson of the AUC, the South African Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, as well as on the Commissioners for Peace and Security, the Algerians Ramtane Lamamra and his successor Smaїl Chergui. The proposal for ACIRC presented a direct challenge to the spatial division of the African Standby Force into five regions, bypassing the regional cornerstones for multilateral African-led military deployment, that is, ECOWAS and other regional organizations. Member states would be able to negotiate military coalitions among themselves and in direct coordination with the AUC, giving individual states more control. In that way ACIRC created a different relational space in which ‘near’ and ‘far’ are not constructed based on a geographically contiguous region, but on the self-image of being truly committed to joint independent African military action. In African military politics, ACIRC was an attempt by President Jacob Zuma to position South Africa and himself as a continental military leader who is willing and capable to guide interventions. When ACIRC was discussed as potentially providing the military response to the violence committed by Boko Haram, political tensions between Nigerian representatives (who were not committed to ACIRC) and South African and Tanzanian representatives surfaced. It provoked tensions that Tanzanian and South African troops from ‘far away’, Southern and Eastern Africa, would even be proposed for deployment in Nigeria’s ‘backyard’. This suggests that while the spatial semantics underpinning ACIRC resembled a network of volunteering nations, spatial semantics regarding regional spatial divisions remained important. The quest to establish this new framework for African-led military deployment ended in January 2019 when the African Union Peace and Security Council integrated ACIRC into the ASF. This decision was taken with little opposition from South Africa, where Cyril Ramaphosa had succeeded Zuma as president in February 2018, a reminder of the significance of individuals in driving political projects through spatial semantics.

Chapter 4 analyzes how bureaucrats of the AUC introduced the Nouakchott Process, a new framework for security and intelligence cooperation communicated via the spatial semantics ‘Sahelo-Saharan Region’ from which another proposal for African-led military deployment emerged. Cooperation within this frame allowed the commission, but also Algerian representatives to become more involved with the unfolding conflict dynamics and responses in Mali and the Sahel. Actors who had felt sidelined by the French Operation Serval were able to reposition themselves as a result. In March 2013, the first meeting of the Nouakchott Process brought together eleven member states of the ‘Sahelo-Saharan Region’, from Senegal to Chad and Libya to Nigeria. African interveners shared an understanding of the conflict dynamics as transregional and pressed for closer collaboration between decision-makers in the region, for the moving on from lingering distrust. The spatial semantics that shaped the Nouakchott Process were more inclusive towards existing ASF regions and promoted a bridging of the three Regional Standby Forces (North, West, Central) to cover the transregional conflict dynamics across ‘this Sahel’. Like ACIRC, the establishment of the Nouakchott Process revealed dissatisfaction with the existing regional division of the ASF regions. Instead of overcoming its spatial division completely, however, the Process sought to enhance the operationalization of the three Regional Standby Forces and promote interoperability. Given that the African Union was sidelined by the NATO intervention in Libya and, to a lesser extent, by the Franco-Chadian intervention in Mali, it is significant that the spatial semantic ‘Sahel-Saharan’ gives expression to the interconnectedness of these conflicts. It even includes the security concern over Boko Haram and the military deployment within the Multinational Joint Task Force of the Lake Chad Basin Commission. By bringing together the different member states, as well as representatives from the United Nations, the African Union, and the existing regions, like ECOWAS, the Nouakchott Process softened the regional and hierarchical division of responsibility, allowing for dialogue while re-centring the African Union as the primary organization responsible for security. In close collaboration with its Algiers-based African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism (ACSRT), the Nouakchott Process allowed the AUC to reinvigorate the operationalizing of several pre-existing initiatives. Most of the activities were conducted by, or through, the ACSRT, underlining the close entanglement of Algerian representatives with the drafting of security policies at the level of the African Union. During the First Summit of the Nouakchott Process in December 2014, the establishment of an Intervention Force for northern Mali was decided. It came amidst a deteriorating security situation in Mali and the continued dissatisfaction by West African policymakers with the – in their view – too passive course of action by MINUSMA. Yet the Intervention Force never moved beyond the planning stages.

Chapter 5 examines the genesis of the regional organization G5 Sahel and its Joint Force composed of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger. It looks at a small group of actors that initially did not extend far beyond the circles of the five involved presidents who set up the organization with particular support from the French and other European partners like Germany and European Union bureaucrats. Following up on the discussion on the entanglement of spatial semantics with the issue of distrust and suspicion in politics from Chapter 4, this chapter begins with an analysis of the different narratives about the ‘origin’ of the G5 Sahel among bureaucrats of the African Union, European Union, and ECOWAS that inter alia brought about French, Malian, Chadian, or Mauritanian agency. By way of a critical reading of the spatial semantics underpinning these narratives on the ‘origin’, the underlying assumptions and attitudes are analyzed. The spatial semantics used to delineate the G5 Sahel were built around an idea of ‘core countries’ in the Sahel, which mapped onto the five member states. This paralleled the understanding of ‘Sahel’ in the European Union’s Sahel Strategy – a more exclusive frame than that of the African Union’s Sahel Strategy that mapped onto the Nouakchott Process’ understanding of a ‘Sahelo-Saharan Region’, which is most significant in its exclusion of Algeria. Remarkably, the understanding of ‘Sahel’ in the European Union’s Sahel Strategy is based on assumptions about the area of activity of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb at that time. Moreover, this is mirrored by the territorial extent of the G5 Sahel Joint Force, formally launched in July 2017, which maps onto the area of operation of the French Operation Barkhane, which had been active across the five Sahelian countries since August 2014. Its activities are surrounded by debates about a French ‘exit strategy’ and doubts about the ‘ownership’ of this initiative for African-led military deployment. Furthermore, the deployment of the Joint Force renewed impetus to discussions about the orientation and future direction of APSA, its African Standby Force, and Peace Support Operation. Discussions about the significance of such African military coalitions also surrounded the deployment of the Multinational Joint Task Force against Boko Haram. Both forces, as well as MINUSMA, drew on Chadian troops, allowing Chadian president Idriss Déby Itno to gain international recognition as a regional peacekeeper, diverting attention from criticism about considerable human rights violations under his government. In this context the establishment of the G5 Sahel should be understood against Déby’s earlier attempts to revive the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), which had been driven by Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi until his death, and against the appointment of Moussa Faki Mahamat, previously Minister of Foreign Affairs under Déby, as AUC chairperson in January 2017. Considering this, the omission of Algeria and Nigeria from the G5 Sahel highlight the competitive dimension of African military politics that surround negotiations for African-led military deployment.

Chapter 6 broadens the scope beyond a mere conclusion calling more broadly for a serious appreciation of African politics in the study of Critical Geopolitics as well as vice versa for studying African politics with a sensitivity to space-related narratives. So far Critical Geopolitics has largely omitted African experiences. African actors are often discussed as solely being affected by geopolitical ambitions of others such as China, the United States, or France, rather than being considered as having active agency in shaping international politics. Moreover, it situates political projects within a context of different ambitions for regional integration as well as competing continentalisms by diplomats and politicians from inter alia Nigeria, Algeria, Chad, and South Africa, as well as from within the commissions of ECOWAS and the African Union. African Military Politics in the Sahel finds that the use of spatial semantics in the negotiations for African-led military deployment is tied to more general competing continentalisms promoted by representatives from different member states. Specifically, the policy ambitions of inter alia President Jacob Zuma of South Africa, President Idriss Déby Itno of Chad, and the Algerian Commissioners for Peace and Security at the AUC have found their expression in the different proposals for military deployment that they lobbied for in the Sahel. Based on the findings of the study, Chapter 6 calls for an expansive understanding of politics in Africa under the consideration of space, arguing that it is time to acknowledge more the importance of spatial semantics in African military politics, especially given the current re-emergence of geopolitical narratives about the continent and on the continent.