We nowadays consider nostalgia as an emotion. The meaning of this term, however, has experienced significant changes throughout its history, since it was first coined in the seventeenth century in medical science. Originally, nostalgia was an illness resulting from an uncured longing to return home, and it was therefore closer to what we nowadays refer to as homesickness. It was with a thesis on the subject that medical doctoral student Johannes Hofer coined the term and thus gave a scientific status to what had previously been described in French as the mal du pays, or the suffering caused by the distance to one’s homeland. Hofer’s thesis was defended in the Swiss city of Basel; this is no coincidental fact, for some of the first and most determining theories of nostalgia (Diderot or Rousseau, for instance), linked this pathology to the Swiss landscape. The connotations of the term nostalgia were significantly altered throughout the nineteenth century, leaving behind its medical associations to enter the sentimental vocabulary of writers and musicians. As a result, nostalgia increasingly catered to the urban audiences who, from the city, reminisced about the countryside, its hills, creeks, and pastoral atmosphere (see Figures 1 and 2). A large metropolis and cultural hub of its time, Paris emerged as an eminently nostalgic capital, where many of its inhabitants dreamed of an escape. This desire meant both returning to the countryside or to an older version of the city. This article explores the polarity between countryside and urban environment by offering the first detailed study of musical pieces explicitly entitled nostalgia of the French nineteenth-century repertoire.

Figure 1. Illustration by Alexandre David on the cover page of La Nostalgie, ou le Mal du Pays, music by Paul Henrion, lyrics by Pierre-Jean de Béranger (Paris: J. Meissonnier, 1841).

Figure 2. Illustration by Pierre-Joseph Challamel on the cover page of La Nostalgie (Mal du Pays), music by Charles-Henri Plantade, lyrics by Mr. Justin (Paris: A. Romaguesi, 1837).

In Paris alone, nearly three dozen compositions titled Nostalgie were published between the 1830s and the First World War.Footnote 1 This number may not seem like much among the several thousands of pieces published during that period. But these pieces offer a range of sonorous and thematic ideas that provide a more comprehensive understanding of how musicians, increasingly conscious of the artistic value of nostalgia, dealt with it as a deliberate idea over the course of several generations.Footnote 2 This repertoire also reveals the position that the city itself, along with its symbols and clichés, played in expressions of longing. These compositions reflect changing sensibilities toward what and where home is, and what longing to return home means. They reveal musings on distance, absence, space and nature. A close examination of this repertoire – which is defined by its shared terminology rather than by musical style or genre – sheds a different light on the story that scholars have uncovered about the origins of nostalgia and its conceptual shift in the nineteenth century.Footnote 3

Hofer’s newly diagnosed illness put a name to an experience that has defined the relationship between people and the spaces they inhabit since time immemorial. This experience is that of wanting to reconnect with the spaces inhabited in the past and with what the past life felt like. In Milan Kundera’s words, Homer’s Odyssey is the ‘founding epic of nostalgia’.Footnote 4 Likewise, the history of European art and music had been marked by moments of retrospection before the term nostalgia was coined, and before it was applied to musical works. We may think for instance of the longing for the pastoral, already prominent during the Renaissance and still fashionable in the 1800s (as famously heard in Beethoven and Berlioz, for instance), or of notions of the Romantic melancholy, spleen, and reverie. This means that nostalgia is often a posthumously ascribed label.Footnote 5 This article takes a novel approach in the field of nostalgia studies, and of musical nostalgia in particular, by analysing musical works explicitly titled as nostalgia. This implies a reflection about this concept on the part of the composers and thus illuminates the existing, and growing, scholarship on nostalgia through the study of how this emotion is conveyed musically. Musically evoked nostalgia in the nineteenth century contributed to the demedicalization of the term and thus has its own, distinct, intellectual and philosophical history that this article helps to better understand.Footnote 6 The first half of this article discusses the earliest examples of compositions entitled nostalgia: vocal works that support literary narratives about displacement and in which Paris is characterized as the trigger of nostalgia. Secondly, the article shows how composers of the following generations (from the 1850s to the early 1900s) began to construct a musical vocabulary of nostalgia, leaving aside the transmission of nostalgic feelings through literary associations. While mid-century examples of instrumental works denoted nostalgia within the structure of the music, by the turn of the twentieth century some musicians were trying to identify specific sounds that could signify nostalgia. By then, the emotion not only became a musical object, but a material one as well: longing turned into a commodity that could be purchased, and that could be experienced as a form of popular entertainment. As the article shows, the way Paris projected different urban desires evolved throughout the course of the nineteenth century. It went from being characterized as the antagonist to any nostalgic emotion, which initially resided in longing for a lost country, to becoming a privileged marketplace of musical nostalgia, where composers capitalized on the appeal of commodified emotions.

Mal du pays and Parisian Longing for Nature

The period during which nostalgia first entered the musical lexicon overlaps with what Thomas Dodman has referred to as ‘a short-lived “golden age” for clinical nostalgia and its self-professed experts, French military doctors’.Footnote 7 In the 1820s and 1830s, nostalgia was known as a pathological ailment that was triggered by geographical displacement, as if one would interpret homesickness literally: it is the illness caused by the absence of home.Footnote 8 The issue was so prevalent that medical dissertations on nostalgia appeared yearly in France in the 1820s and 1830s, including at the universities of Paris, Montpellier, and Strasbourg.Footnote 9 In Europe, soldiers and military physicians formed the largest group of people who confronted what several scholars have called an ‘epidemic’ of nostalgia, which had severely affected the Napoleonic armies, for instance, as reported in letters and medical records of the time.Footnote 10

The general public, too, was developing a fascination with the subject. Before composers began to employ the term nostalgia, the feeling of longing for one’s country had been known in French as mal du pays (the pain of the country/home), and several artistic works echoed this sentiment, including Le Mal du pays ou la batelière de Brienz (December 1827), a tableau-vaudeville in one act by Eugène Scribe and Mélesville that presented all the usual attributes of the nostalgic ailment.Footnote 11 The work filled the desire of Parisians for a pastoral life, while it exploited the duality between rural and urban settings. Set on an idyllic lakeside scene in Switzerland, the play interlaced the stories of two homesick young men: one a Swiss soldier who deserts his Paris regiment to return home, the other a poet who longs for Paris after having been forced into exile because of the bawdy songs he performed in the city. The situation is happily resolved when the two homesick men agree to take each other’s place. Even though the text does not explicitly mention nostalgia, it shows the authors understood its main characteristics, including its military associations (familiar in France since the deadly outbreaks that decimated the Napoleonic armies) and its longstanding stereotypical associations with the Swiss countryside. Indeed, Switzerland had been the privileged place for discussions of nostalgia, going back well before the period discussed here and the upheavals of the French Revolution and of the Napoleonic Wars. Definitions of the concept of nostalgia present a striking set of stable ideas from the 1700s to the 1800s despite the major societal changes that occurred in France. For instance, most of the article on nostalgia in Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie theorizes on why the Swiss are particularly inclined to suffering from it.Footnote 12 Dictionaries in France echoed this idea until well into the twentieth century: the popular Larousse dictionary stated that ‘les Suisses sont très sujets à la nostalgie’ (‘the Swiss are very prone to nostalgia’).Footnote 13 While Le Mal du pays refers to these conventions, it also expands on them in its particular treatment of Paris as a locus of nostalgia as potent as the pastoral nature of the Alps. The longing of the Parisian poet for the city is illustrated without embellishment, as a sort of comical antithesis to the Swiss nature: it is because of its ‘awful roads’, the ‘dust on the Champs-Élysées’, and the absence of trees in the parks that he longs to return to Paris.Footnote 14 With Scribe, the longing to return home develops into a desire to either inhabit or escape from an urban place: the city, even when its numerous annoyances are ridiculed in vaudeville fashion, was an object of longing as valid as the natural lifestyle of the countryside. The plot of Scribe’s work relies entirely on this dynamic tension between the countryside and the city, signalling the increased circulation of people and ideas from one place to the other in the early 1800s, and its attractiveness to the Paris audience for whom the play was staged. This mockery of urban nostalgia could only be successful if the characters it portrayed were easily recognizable as stereotypes, as was often the case with Scribe.

The vaudeville included an overture and a series of eight interpolated songs and choruses composed by the young Adolphe Adam, who had previously collaborated with Scribe a handful of times. Although some of the numbers evoke the Swiss setting by exuding a folk character with the use of pedal points, arpeggiated melodies, and simple harmonic progressions, the composer did not display a marked stylistic contrast between Switzerland and Paris. The music itself did not attempt to reflect the mal du pays, but merely to underscore local colour when appropriate. For instance, the only critic that briefly mentioned Adolphe Adam suggested that – if the actors could sing – the trio would be a hit in Paris.Footnote 15 The trio (no. 3 in the published score) is the play’s most overt evocation of Swiss music: it is designated as a ‘tyrolienne’ in the libretto and is initially performed on the bagpipes (although the published vocal score indicates the ‘oboe’). As the only passage in the score that received any mention at all, we can imagine that it stood out for its exotic character rather than from eliciting nostalgia for the Alps. As Thomas Dodman writes: ‘The nostalgia enacted in [Scribe’s] play is a sanitized, pale copy of its medical progenitor, a sham nostalgia fit for popular consumption’.Footnote 16 In fact, as I will illustrate further below, Adam’s approach was typical of music composed to support literary or poetic narratives about the mal du pays in the first half of the century. In other words, it is not the mal that composers set to music, but the pays itself, regardless of its connections with longing.

Writers in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries thought that music could elicit nostalgia only under specific circumstances. The centrality of Switzerland in discussions of nostalgia meant that a Swiss genre of pastoral melody, called the ranz-des-vaches, became inextricably connected with nostalgia. Mentions of the ranz-des-vaches from that period exemplify conflicting interpretations of the causes of the illness. For some people, the ranz-des-vaches triggered nostalgia when a variation of it was heard outside of the listener’s native Switzerland. Helmut Illbruck, who published a detailed intellectual history of the ranz-des-vaches, wrote that nostalgia was triggered by ‘the difference between the ranz-des-vaches he hears, a displaced reproduction of another variety, and that which he truly longs to hear, for him the unique and inimitable original, painfully different and out of reach’.Footnote 17 This is what Illbruck refers to as ‘nostalgia for particularity’, or the longing for something distinct in the original sound, which is inextricable from its geographic origins. In Scribe’s play, this would have happened if the Swiss soldier had heard an imperfect rendition of a ranz-des-vaches in Paris, or if Adolphe Adam had parodied it in his score. The particularity of the ranz-des-vaches was not transferred to other types of music, however, and no-one really ventured to address what were its unique qualities – besides, of course, being performed by a people already marked as nostalgic. Therefore, other listeners regarded the particularity of a ranz-des-vaches as secondary, arguing that its sound merely served to recall memories in the listener. Decades before Scribe and Adam, this was already Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s opinion when he discussed the ranz-des-vaches in his Dictionnaire de musique of 1768:

On chercheroit en vain dans cet Air les accens énergiques capables de produire de si étonnans effets. Ces effets, qui n’ont aucun lieu sur les étrangers, ne viennent que de l’habitude, des souvenirs, de mille circonstances qui, retracées par cet Air à ceux qui l’entendent, & leur rappelant leur pays, leurs anciens plaisirs, leur jeunesse, & toutes leurs façons de vivre, excitent en eux une douleur amère d’avoir perdu tout cela. La Musique alors n’agit point précisément comme Musique, mais comme signe mémoratif.Footnote 18

We shall seek in vain to find in this air any energic accents capable of producing such astonishing effects. These effects, which are void in regard to strangers, come alone from custom, reflections [‘souvenirs’], and a thousand circumstances, which, retraced by those who hear them, and recalling the idea of their country, their former pleasures, their youth, and all their joys of life [‘toutes leurs façons de vivre’], excite in them a bitter sorrow for the loss of them. The music does not in this case act precisely as music, but as a memorative sign.

The character of the music did not matter: any music that was intimately familiar to the listener could act as a memorative sign, given the proper circumstances. But geographical distance and familiarity with the music played an essential role. Hence, in theory, a new composition could not possibly trigger nostalgia unless it imitated music known to its audience, or it derived from such music. The nostalgic effect on the listener did not, therefore, depend as much on the music of choice but rather on the idiosyncratic relationship that the listener establishes to that music and how it relates to their life narrative.

These historical, medical, theoretical, and musical considerations might explain why composers did not attempt to represent nostalgia explicitly through original music until the 1830s. As we will now see, using nostalgia as the topic of a musical composition was a consequential choice. It denotes the appropriation for creative purposes of what was then primarily defined as an illness and was primarily rooted in memory. It marks a step in the gradual adoption of a demedicalized form of nostalgia that acted as a metaphor for the pain of displacement, and which would eventually eclipse other expressions like mal du pays.

Urban Desires of Hortense de Beauharnais from her Swiss Exile

The first original musical composition to mention nostalgia explicitly in its title was Hortense de Beauharnais’s La Nostalgie, published in 1833.Footnote 19 HortenseFootnote 20 was a rather unlikely resident of Switzerland, a member of the disempowered political elite that was forced into exile at the fall of the Napoleonic regime. Daughter of Joséphine de Beauharnais, who married Napoléon Bonaparte in her second marriage, Hortense herself married Napoléon’s brother, Louis Bonaparte, becoming Queen of Holland from 1806 to 1810 and mother of the future Emperor Napoléon III. After Napoléon Bonaparte’s abdication in 1815, Hortense settled at the castle of Arenenberg, in Switzerland, where she died in 1837, at the age of 54.

Considering her exile from the defunct empire that had seen her grow into an accomplished woman, it is no surprise to find expressions of homesickness in several of Hortense’s romances, of which she wrote around 150 over three decades. Her Lay de l’exil (marked con dolore) expresses the pain of dying away from France, and in her patriotic romance Les Charmes de la patrie she longingly promises to come back and die in her native land. By the time of Hortense’s exile in Switzerland, nostalgia had long been rooted there, in medical as well as musical discussions. This makes her engagement with it far from accidental, and rather emblematic of her time, place, and personal situation. But we need not forget that Hortense was an aristocrat, from a privileged class whose experience of longing was unlike anything experienced by the soldiers, surgeons, and lower classes who had been the first sufferers of the illness.Footnote 21

Accounts of Hortense’s exile describe the busy and lavish lifestyle that the ex-queen enjoyed at her residence in Arenenberg, ‘as if the First Empire never came to an end for her’.Footnote 22 The décor of her salon recalled the one at Malmaison, her last residence in France, which ‘the Queen wanted to reproduce here, to always have before her eyes a corner of France’.Footnote 23 It was here that Hortense regularly hosted the intellectual elite of France – Chateaubriand, Alexandre Dumas, and others – for whom she occasionally composed and performed her romances. Such romances were a musical bridge to her past, an expression of her desire to repossess a space that was no longer.

Romances are short strophic songs that rose in popularity in the second half of the 1700s. They are characterized by melodic simplicity and a straightforward accompaniment that an amateur singer could play on the harp, lyre, or pianoforte while singing. The success of a romance depended largely on the quality of its text and of the declamation by the singer, while the accompaniment needed to support the poetry without drawing attention to itself. The romance reflected the social and professional life of the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy, including their customs and values.Footnote 24 With time the romance was phased out in favour of the more sophisticated art songs eventually known as mélodies. By the mid-1810s, the genre was already becoming associated with the pre-Revolutionary era.Footnote 25 Hortense’s choice of the romance could be interpreted as a sign of her exile, her distance from the Parisian salons and their ever-changing musical forms, and as a testimony of her musical childhood.

The published score of Hortense’s romance La Nostalgie (Figures 2 and 3) only indicates the name of the work’s lyricist, Pierre-Jean de Béranger, a prolific songwriter who remained faithful to the legacy of Napoléon and whose lyrics Hortense had previously set to music.Footnote 26 La Nostalgie tells the story of a villager who is assured to find gold, care, knowledge, and entertainment in Paris. But as soon as he arrives, he begins to long to return to his village, to see the mountains where he was born and to hear its songs. Each of the six verses depicts a celebrated feature of Paris (the Opéra, the Louvre, etc.) that fails to cure the villager’s nostalgia. This only happens in the final verse, when he returns to his village (implicitly understood to be the Swiss countryside). The lyrics include references to the physiological pain caused by clinical nostalgia, such as ‘La fièvre court triste et froide en mes veines’ (‘a fever runs coldly and sadly through my veins’), and ‘J’y meurs, hélas! j’ai le mal du pays’ (‘I’m dying there, alas, I am homesick’). These phrases should probably not be taken literally. They likely act as metaphors for the villager’s distress, or what Thomas Dodman calls ‘illness as metaphor’.Footnote 27 But at the same time, we cannot ignore that Hortense lived at a time when doctors diagnosed dying patients with nostalgia. Béranger’s words are not just expressions of the pastoral; they actually reflect the anxiety and fear of migration. They also partly reveal that a sanitized version of nostalgia was becoming available, one with which composers like Hortense de Beauharnais could engage. This exemplifies how nostalgia became an emotion that appealed to the upper classes, one they could experience from the comfort of their salon without becoming ill.

Figure 3. Hortense de Beauharnais (music) and Pierre-Jean de Béranger (lyrics), La Nostalgie (n.p., 1833). Digital document available on Gallica: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1504958x.

One of the most powerful drives of nostalgia is the impossibility of the return. Less than a year before composing La Nostalgie, Hortense had written a volume where she narrated a trip to France in 1831. Here, her undying love for her country is mixed with the pain caused by her incapacity to return. Reacting to the law that renewed her expulsion following the ascension of Louis Philippe in 1830, she wrote:

Je ne comptais pas aller à Paris; loin de là, je m’arrangeais pour mon voyage d’Italie. Mais la vue de cette loi qui nous expulse à jamais de cette France qu’on aime tant, où l’on espérait encore aller mourir, est venue renouveler toutes mes douleurs.Footnote 28

I did not intend to go to Paris; far from it, I was planning my trip to Italy. But the sight of this law that expels us forever from this France that we love so much, where we had still been hoping to die, renewed all my pain.

So why would she choose to compose a romance that pretends otherwise? Nostalgia is not only about the real places one might return to, but about every possible alternative to them. Hortense was perhaps mourning the demise of France and Paris as she once knew them, places she would never be able to return to even if she physically came back, as the cultural and political context had been radically transformed since the end of the Empire. Hortense may be compared to the poet in Scribe’s vaudeville: her romance La Nostalgie longed for the very things that are perceived as the source of affliction.

La Nostalgie followed the conventions of the genre by retaining melodic and harmonic simplicity, and by affording the piano only a brief ritournelle.Footnote 29 Symbolically, this romance acts as an ideal genre to parallel the villager’s rejection of Paris, as it avoids any clever modulation or sophisticated texture that could be interpreted as refined, highbrow, or even just characteristic of the contemporary musical culture of Parisian salons in the 1830s. The strophic nature of the romance also provides a recurring return home, textually, melodically, and harmonically. For instance, the two-line refrain is written as a 16-bar period that cadences in the tonic of G major, which provides stability and contrast after the stanza’s three 8-bar phrases that all cadenced on the dominant. The melody, especially at the refrain, evokes a folk-like simplicity even though it bears no obvious resemblance to the features of the Swiss ranz-des-vaches, such as their natural intervals and quick repeated chordal patterns. Even if Hortense might not have done so consciously, her romance supports the lyrics’ narrative while allowing an expression of longing that does not rely on the specific attributes that previously defined musical nostalgia, such as relying on a melody’s familiarity as a ‘memorative sign’ or drawing from explicit local styles like the ranz-des-vaches, the bagpipes, or the ‘tyrolienne’. As a result, she contributed to freeing nostalgia from its medical and geographic origins and made it more appealing to an audience that was not necessarily experiencing nostalgia first-hand.

Urban audiences were the main consumers of musical nostalgia, to whom romances like the one by Hortense de Beauharnais were marketed. In the decade following the publication of La Nostalgie, a handful of other romances were published in Paris that sung the same opposition between the city and the countryside in an atmosphere of pastoral lyricism.Footnote 30 Even pieces not explicitly about nostalgia occasionally engaged with this duality, such as Auguste Panseron’s Paris et le Tyrol (1834). But unlike the rather austere presentation of La Nostalgie, these romances all featured illustrated cover pages featuring countryside scenery (see Figures 1 and 2 above). These publications show how a change of paradigm had operated in relationship to how nostalgia was treated as a musical subject. There had been a growth of interest for these pieces: for example adverts for Paul Henrion’s La Nostalgie had appeared in music journals such as Le Ménestrel and the Revue et gazette musicale de Paris. Leaving behind its medical context and its association with the military, nostalgia was by the mid-nineteenth century part of the emotional vocabulary of composers, and a resource used to articulate conflicting ideas about home, belonging, the return, nature and urban space.

Interpreting Nostalgia in Mid-Century Paris

With the rise in popularity of instrumental pieces modelled after dance music (to the detriment of vocal compositions such as the romance) the tandem of music and nostalgia entered a new chapter. As a consequence, the works entitled nostalgia of the third quarter of the century were written for solo piano, which posed new challenges for the transmission of nostalgia without the aid of literary poems and lyrics.Footnote 31 The main difference between pieces of this generation and those of the previous one is that Switzerland no longer acts as the prime locus of nostalgia. The core definition of nostalgia had not changed significantly – it was still felt as an intense sense of attachment to a distant place, an intense longing to return home – but it now more broadly conveyed the desire to be elsewhere. An anonymous author transformed in 1861 the mal du pays of earlier nostalgia into a mal de Paris to lament the rural exodus, the pace of modern urban development and industrialization, while retaining the classical medical terminology of nostalgia:

Ce mal qui te possède est une nostalgie;

J’en fus atteint moi-même avec trop d’énergie

Pour ne point m’opposer à sa contagion:

C’est le Mal de Paris, funeste attraction,

Qui dépeuple nos champs et rouille les charrues,

Pour grossir la poussière et le limon des rues,

Mal terrible, anxieux, brûlant comme un cancer,

Importé, suscité – par les chemins de fer.Footnote 32

This affliction which possesses you is nostalgia.

I myself was struck by it with too much energy

So as not to oppose its contagion:

It is the Mal de Paris, a fatal attraction,

Which depopulates our fields and makes the ploughs rust,

To increase the dust and the silt of the streets,

A terrible, nervous sickness that burns like a cancer,

Introduced, provoked – by the railways.

Changes in transportation infrastructure – such as the erection of several major railway stations in the late 1840s – broke the previous isolation of remote rural communities from Paris.Footnote 33 The city grew as a modern attraction for all social classes. Nostalgia as a longing to be in Paris often eclipsed the appeal of more practical considerations for artists, like the potential for greater financial gain or artistic opportunities. Musicians were not spared: several accounts by music critics from those years claim that ‘nostalgia for Paris’ was prevalent among Parisian composers. It is credited as the reason for Adolphe Adam’s declining of a position in Russia, and for Ferdinand Hérold’s daydreaming of the Parisian arcades during a visit to Venice.Footnote 34 In this context, Parisian nostalgia evolved into a kind of idealization of urban longing that replaced nostalgia’s roots as a pathology. The nostalgic songs about Paris of the second half of the century – Paris s’en va (Paris is going away, 1860) by Charles Colmance and Les Ruines de Paris (The Ruins of Paris, 1871) by Gustave Nadaud, for example – evoked rather a temporal form of longing, which contrasts with the spatial concerns of earlier times.Footnote 35 No doubt the fundamental transformation of the city under Baron Haussmann gave way to a wave of nostalgia for the loss of Old Paris which was also felt in reactions to the urban soundscape.Footnote 36 The Parisian urban desires expressed in these songs acquired an archaeological dimension by digging through the new face of the city to give a voice to the city that once was.

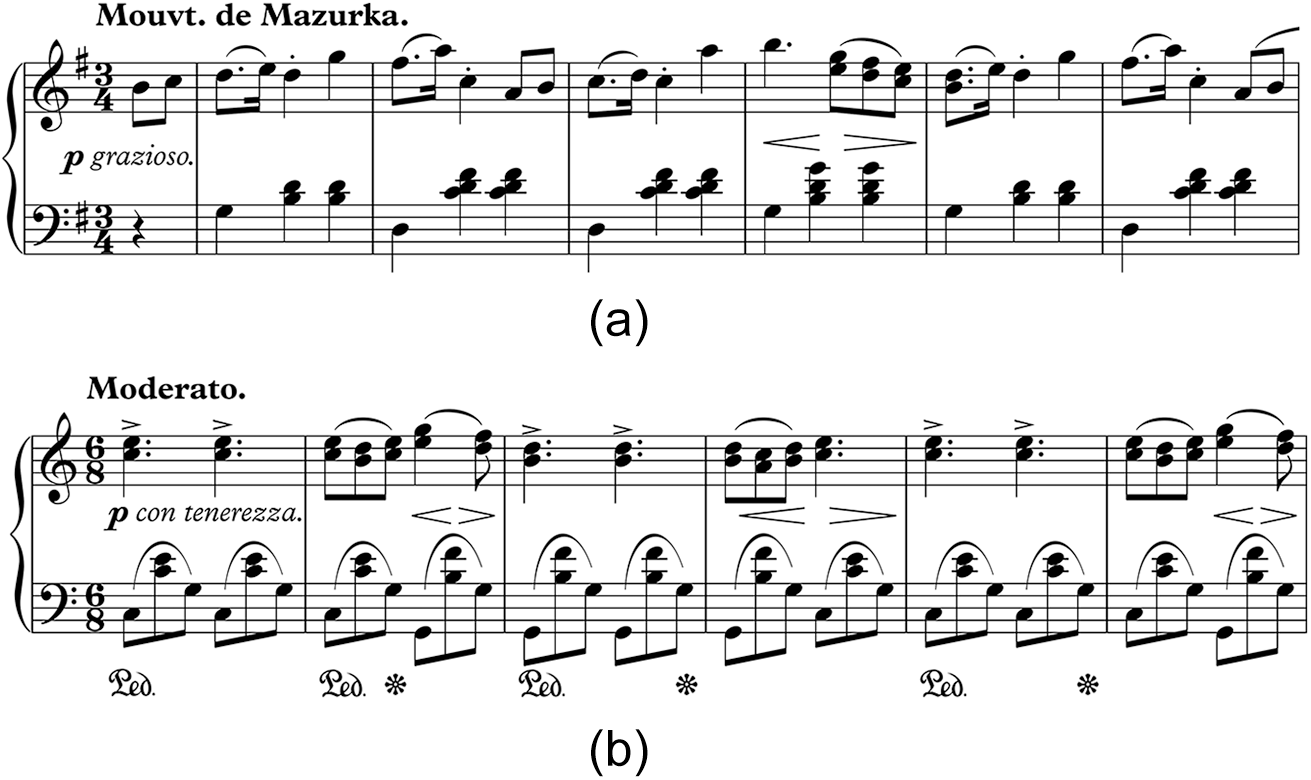

Example 1. Adrien Deshayes, La Nostalgie: Polka-Mazurka pour piano (Paris: Étienne Challiot, 1858), (a) bars 8–12 and (b) bars 33–38.

Composers of this period used contrasting sections to express geographical distance in instrumental pieces whose titles referred to ‘nostalgia’. Hence, the middle section of a ternary form could represent a space of longing. This is the case of La Nostalgie, a polka-mazurka by Adrien Deshaye (1858) where the main section starts with a bright allegretto grazioso (Example 1a), while the more relaxed trio section, in the key of the subdominant, is marked tristamente, avec abandon (Example 1b).

In a piano fantasy by Maurice Lee (Op. 14) published in Paris in 1860, a mazurka is again marked grazioso and includes other expressive terms like elegante and lusingando (flattering) (Example 2a). But this time it is the preceding section (again in the key of the subdominant) that exhibits a contrasting – and stylistically foreign – character with a quiet barcarolle marked con tenerezza (with tenderness) that eventually becomes con duolo (with sorrow) over a Neapolitan chord (Example 2b).

Example 2. Maurice Lee, La Nostalgie: Fantaisie pour piano. Op. 14 (Paris: Jules Heinz, 1860), (a) bars 54–59 and (b) bars 13–18.

To be sure, there is nothing exceptional about this type of contrasts in the ternary forms of mid-century instrumental music. But given the subject of these pieces, these contrasting passages could be heard as representing the moments of nostalgic longing for another place. Other noticeable contrasts between disjunct and conjunct melodies, between loud and soft dynamics, between staccato and legato phrasing, could together be heard as reflecting an opposition between two distinct musical environments, one of outward and playful grace, and one of inward reflexion. Based on the conceptions of nostalgia that circulated at the time, I would suggest that these passages offer a moment of relief from the elegant or ‘gracious’ atmosphere of the bourgeois salon to an undefined place of relative innocence. This interpretation urges us to rethink the symbolism of the mazurka here not as a marker of national nostalgia for the homeland (as scholars have argued in regard to Chopin’s mazurkas, for example) but rather as a marker of the social environment of the salon, from which the compositions frame their momentary departure, however subtle it may be.Footnote 37 Already in 1852, Henri Cramer’s mazurka Das Heimweh, Op. 133, issued in French as La Nostalgie, provided a clear example of such musical narrative. This fine mazurka features a trio section in which bells are heard ringing sforzando at the beginning of each bar against a delicate pianissimo countermelody (Example 3). The sounds of bells, as Alain Corbin established, acted as powerful symbols of rural identity in the nineteenth century, and here can therefore serve to provide a direct memory of the countryside as the contrasting middle section in a salon piece that could accordingly be heard as displaying an ‘urban’ character.Footnote 38

Example 3. Henri Cramer, La Nostalgie (Das Heimweh): Pensée musicale. Op. 133 (Mainz: B. Schott, 1852), bars 46–50.

This sample of mid-century compositions illustrates a new way of thinking about nostalgia musically. It was no longer simply used to accompany a poetic narrative; composers now attempted to incorporate longing within the musical structure itself, doing so by relying on a simple notion of polarity between two distinct and antithetical places. Yet, we cannot convincingly argue that there are clear and specific musical traits that can be interpreted as expressing nostalgia musically in these works. It is because of structural difference that nostalgia operates, and not as an abstract musical characteristic that can be isolated. The sophisticated art of the salon, exemplified in these pieces by the mazurka, offers a symbolic contrast to the dear, distant, or sorrowful passages. Would any of these pieces still evoke nostalgia if it were not for their titles? Could it be that the titles were added as an afterthought, either by the composers or by their publishers? The real issue here is that because of their titles (regardless of whether they were justified musically by the composers) these pieces invited Parisian listeners to pay attention to and reflect on the musical character of nostalgia – until recently considered an illness – in new ways. These were not narrative or intellectual discourses about nostalgia, but musical ones. They announce the coming growth of nostalgia as a popular, yet increasingly imprecise signifier, one that started to occasionally be used as a mere synonym to melancholia (tristamente, con duolo), and that would gradually lose most of its remaining associations with specific geographic locations over the following decades.

Thinking About Nostalgia in Musical Terms

It is in the late nineteenth century that a more explicit association between nostalgia and specific musical attributes began to spread in musical works and music criticism. Instead of constructing nostalgia as the result of geographical, emotional, or structural contrasts (urban/rural, here/there, vibrant/pensive, loud/soft, and so forth), musicians now more frequently attempted to represent it directly through expressive means. This new direction in thinking about nostalgia musically reflects the development of psychological explanations of longing that were no longer tied to geographical displacement. After a two-decade hiatus during which the term, although increasingly used in music journalism, had seemingly disappeared from music publications, it resurfaced in a piece titled Nostalgie by Léon Moreau published in 1896.

Departing from the previous compositions about nostalgia, Moreau abandoned the use of contrasting sections to anchor the moment of longing or of local colour to evoke a distant place. Instead, he created a relatively unbroken and unchanging texture that unfolds in persistently soft dynamics and at a slow tempo throughout (Example 4). Even though the piece uses a simple ABA form, the brief passage between the two iterations of the A section does not act as an autonomous middle section, but as an extension of the same melodic and rhythmic contour with slightly more dissonant and unpredictable chromatic harmonies. The piece presents a uniform character that prevents associating any specific moment with the idea of nostalgia. The composer wanted to evoke nostalgia as a distinct musical character rather than as a representation of displacement. Moreau signifies longing mostly with the overwhelming use of sustained, accented passing tones stressed on the downbeat of almost every bar, perhaps as reminiscences of sigh figures. The modal ambiguity and chromatically altered chords add to the constant wavering of tension and resolution. In this piece, the object of longing is undefined (nostalgia for what, one might ask), but the nostalgic feeling, achieved solely through musical means, is easily recognizable even over a century later. The music seems to directly justify the title, which speaks to a radical shift in thinking about nostalgia in musical terms around 1900 in ways that still feel familiar to this day, but which were then unprecedented.

Example 4. Léon Moreau, Nostalgie (Paris: Paul Dupont, 1896), bars 1–6.

This shift is also evident in music criticism, where writers progressively referred to nostalgia to characterize entire works as well as distinct passages or musical traits, even though the original definition of nostalgia as homesickness persisted well into the next century. That compositions were declared ‘nostalgic’ by critics amplified the understanding that nostalgia was not so much about the return to a concrete, physical home, but a longing for an irretrievable past. This meaning of the term, which had been at the periphery of its connotations since at least the 1860s, became an increasingly common interpretation after the 1890s. For instance, French music critic Amédée Boutarel often employed the term nostalgia in his concert reviews and articles for Le Ménestrel. A survey of his writings shows not just how the term evolved in its meaning throughout Boutarel’s career but also illuminates the many nuances that the concept of nostalgia had under just one pen. Boutarel commented on the nostalgia for antiquity in Beethoven’s Third Symphony, and considered that Fauré’s Ballade conveyed nostalgia for Chopin and Grieg.Footnote 39 In 1914, this critic wrote that nostalgia should be expressed by ‘a melody of contained emotion’ and without affectation.Footnote 40 Within weeks, he also identified the minor third as a nostalgic interval in the lullaby from Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death, and the oboe’s timbre in a Bach cantata as carrier of the affect.Footnote 41 Together, these reviews show how a vocabulary for nostalgia was starting to emerge in French music criticism, even if there was not a consensus over its specific attributes. Raymond Bouyer, another prolific chronicler for the same publication,Footnote 42 wrote – rather unexpectedly – that the energetic Molto vivace of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is ‘nostalgic for the outdoors’ while he also described as nostalgic the slow and quiet beginning of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique.Footnote 43 These statements, published in one of the main music journals of France, presented readers with new ways of imagining nostalgia in and of itself, detached from the pastoral fantasies that were no longer of interest to the contemporary urban population.

The Commodification of Nostalgia as Entertainment

The growing popularity of nostalgia in Paris in the early 1900s is manifest in the sheer number of compositions explicitly inspired by it, which amount to over two dozen works published between 1900 and the onset of the First World War. Through the combined efforts of music journalism and sheet music marketing, this period emerges as the true beginning of the commodification of musical nostalgia, which rapidly turned it into a popular object of consumption. No longer reserved for an intellectual elite or for the privileged bourgeoisie of the salon, the concept of nostalgia had reached the lower classes as well: there were cabaret songs that mocked or questioned it (Jean Daubas’s lyrics for La Nostalgie, to music by César Fantapié, told that the cure to nostalgia was to let loose and have a good laugh), and there were several dance suites arranged for small orchestra that were likely intended for social dancing rather than attentive listening. This was nostalgia transformed into musical entertainment, not just to make people think or feel, but also to make them laugh and move. It was a concept that was both relatable and marketable, and that attracted audiences. The variety of purposes of this music means that, just like in music criticism, several competing ideas of nostalgia circulated.

About a third of all ‘nostalgia’ compositions from this period were waltzes (ranging from the mildly inspired to the dully generic), but the topic also inspired a march and even a cakewalk whose colourful cover refashioned the dichotomy between the urban city and the primitive nature to suggest the longing of Black people for the lost ancestral land. Among the most notable French composers who contributed to this rebranding of nostalgia were Florent Schmitt (Op. 39 and 42, 1903–12), André Caplet (1918?),Footnote 44 and Louis Vierne (Op. 36, 1921), but the most remarkable piece is arguably Les Nostalgies (Op. 19, 1913), a cycle of six piano works composed by the unjustly neglected composer Marc Delmas, winner of the Prix de Rome in 1919. A direct consequence of the proliferation of nostalgia among various musical contexts in Paris at the turn of the twentieth century is the diversity of musical interpretations attached to it. Most of these pieces do not explicitly reveal the object of their nostalgia, thus often reducing the term to a hollow expression that simply implies a form of sentimentality akin to an objectless melancholia devoid of specific spatiotemporal connotations. Delmas’s six pieces range from a mostly diatonic and delicate opening movement (no. 1) to a highly chromatic (and rather virtuosic) movement marked ‘avec intensité’ (no. 5), and from a light and soft waltz inspired by a famous verse of Baudelaire, ‘Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige’ (no. 2), to an energetic ‘Valse folle’ marked Presto, with a central section Alla burlesca, closing the cycle with a boisterous C major chord played ffff over six octaves (no. 6). Each movement thus projects a different musical response to nostalgia, whose meaning, although guided by the movements’ titles and brief poetic epigraphs, remains mostly open to personal interpretation.

Example 5. Gabriel Fervan, Nostalgie: Valse poème (Paris: Costallat & Cie, 1907), (a) bars 1–8 and (b) bars 49–56.

In this context, specific references to urbanity or to geographical displacement were uncommon among musical articulations of nostalgia. But one such example is a ‘valse poème’ for piano composed by Gabriel Fervan in 1907, which offers an interesting affective reinterpretation of the urban versus rural binary of traditional nostalgia that we have already heard in mid-century mazurkas. The score’s epigraph is taken from a poem by Anna de Noailles in which she reminisces about her youth in the hills but admits her lack of strength to return to the quieter fields, now that she lives in the city.Footnote 45 Fervan’s piece pits an exotic melody marked ‘à la manière tzigane’ (Example 5a) against an affectionate waltz (‘Très tendrement’) whose lack of marked exotic features neutralizes it as ‘French’ in character (Example 5b). The piece thus replicates the polarity between two contrasting environments but replaces the rural–urban binary by an exotic–national one, in which the ‘affectionate’ waltz emerges as a quiet reminiscence of the city, symbolically opposed to the country’s cosmopolitanism, signified by a ‘gypsy’ waltz. It is remarkable that in her poem, Anna de Noailles did not intent to return to the countryside: her nostalgia was benign, it no longer required her to act on its premises. Interestingly, Fervan paralleled this attitude by ending his brief waltz without the customary da capo heard in this genre. Conventions would make us expect a return to the ‘gypsy’ part that is never realized. There is actually no ‘return’. As this piece suggests, at the turn of the century, one could indulge in nostalgia for its own sake. Whereas nostalgia was originally conceived as an illness, and therefore a hopefully temporary state that can be cured, nostalgia in the early twentieth century had already become the emotion that we nowadays understand it to be, a pleasant way to think about the past and about escaping somewhere else. The composer undoubtedly understood this attitude to longing, because rather than citing Anna de Noailles’s longing for the countryside as his epigraph, he chose one of her poem’s more introspectively sentimental lines: ‘Le passé vient et fait comme un baiser dans l’âme’ (‘The past comes and kisses the soul’), which effectively restages his cosmopolitan waltz as a form of sentimental yearning for a dear romantic past.

During this period of surge of popular nostalgia compositions in Paris, the few pieces that still reflected the preoccupations of earlier decades now seemed strangely outdated. Expressions of medical nostalgia were rare. Its most striking example is found in La Nostalgie: Naïveté Militaire, a satirical song from 1905 (lyrics by Félix Clemmenz, music by Octave Lamart), that depicts the scene of a military medical exam. The singer addresses the audience while wondering what his sickness might be, until the major-doctor responds: ‘it’s nostalgia!’ Surprised, the soldier spends the following three verses panicking about a disease he knows nothing about. The hypochondriac soldier mocks ‘nostalgia’ as if it were a newly trending phenomenon: ‘la noc’, j’en ai jamais goûté!’ (‘I never had a taste of nos[talgia]’), which plays with the meaning of ‘noce’ in French, meaning marriage. Anxious, he doubts he will be able to get married if the illness makes him ‘impotent’. At the end of the song, the soldier still does not know what nostalgia is, calling it a ‘mystery’, perhaps as a parody of the vagueness of the term in popular discourses of the day.

A different example of the persistence of century-old understandings of nostalgia is heard in the song N’va pas à Paris (Don’t go to Paris; lyrics by Lucien Guyot, music by Eugène Deshaye) from 1910, which quaintly echoed Béranger’s lyrics that Hortense de Beauharnais had set to music almost a century earlier. It recommended its listeners to stay away in their village, where the air is clean and there is space, even if they were tempted to come to Paris. Ironically, the song was published in Paris, and it is unclear whether it would have circulated much outside the city. Furthermore, rather than attempting to musicalize its longing for the countryside, N’va pas à Paris is written in the style of the popular songs of the day – plus, it is mediocre and banal. The song is distinctly about ‘nostalgia’ as expressed in the first half of the nineteenth century as a duality between ‘the village’ and ‘the city’, but by now its clichéd lyrics feel outdated, and pay no attention at all to the changes in urban lifestyle or to the modern feeling of longing in and for the city. Like many other songs overtly nostalgic for the countryside, the city is defined here as an abstract antagonist (its only characteristic is that its ‘sky is grey’), and the anxiety toward the city is directed more broadly at industrial life. The final lines of the second and third verses shift the narration away from longing to a blessing for those who work the land:

Le travailleur est un homm’ libre

Mais l’atelier, c’est la prison.

[…] On peut être fier de sa tâche

Quand on nourrit l’Humanité!

The worker is a free man,

But the workshop is a prison.

[…] One can be proud of one’s duty

When it feeds Humanity!

In the context of ongoing rural exodus, here nostalgia takes the shape of socialist propaganda addressed at a Parisian crowd.

Conclusion: The Domestication of Musical Nostalgia

The sample of compositions surveyed in this article spans a hundred years during which French musicians from all social backgrounds – from the aristocracy to the working classes – attempted to set to music their understanding of nostalgia as an emotion. While this may seem quite ordinary for us today, as musical nostalgia is widely accepted and omnipresent in our lives, it is only gradually that musicians reflected on this emotion in musical terms. If nostalgia is intimately tied to a lost place or lost time – and even characterized as an illness, as it was in the early 1800s – how does one create new music to evoke this abstract sense of spatiotemporal distance? In the early nineteenth century, when nostalgia was still tied to its medical origins and to the physiological pain of geographical displacement, music marked an important step in its demedicalization. By mid-century, the metaphor of the return home was expressed in instrumental music by means of structural and affective strategies. Nostalgia had acquired its full independence from intellectual discourses and could be felt, or at least imagined, from the comfort of a salon. During that time, European cities such as Paris were marked by unprecedented urban transformations that triggered ever-changing perspectives on the duality between the city and the countryside. Not solely aimed at an idyllic pastoral life, nostalgia was also felt for the city itself, its past and present, as echoed in the music of this time. By the turn of the twentieth century, it is apparent – as was the case with the music criticism surveyed above – that musicians faced an increasingly ambiguous definition of the nostalgic self. The broader appeal of nostalgia had the consequence of expanding its definition and diluting its meaning, paradoxically at a time when more musicians than ever were interested in investing it with specific musical gestures. The changing meaning of the term until nostalgia became an expression synonymous to a sentimental longing devoid of specific spatiotemporal connotations is characteristic of most pieces of the Belle Époque. In contrast, the conflicted relation between the city and the country, which had largely defined the experience of nostalgia in previous generations, was no longer a priority for musicians drawn to it, even though some variations of it exceptionally survived into the new century. There is no doubt that musicians were conscious of its appeal as a popular, evocative, and poetic term, and of its generic suitability to certain types of light music such as the waltz. In return, their efforts to describe specific objects of nostalgic longing were limited. At first glance, it would thus seem that the handling by musicians of nostalgia as an affective term or as a musical subject was shallow, that they did not convincingly seek to produce a strong sense of personal or communal identity in their interpretations of the concept. In fact, one could easily find hundreds of pieces of similar musical character and structure published around the same time under various titles. But the issue is not to depreciate the ordinariness of these pieces, but to question why composers drawn to nostalgia as a concept were attracted to certain types of musical and formal models over other ones, and what these choices reveal about their understanding of nostalgia, its purpose, and its sound. These compositions signal the beginning in Paris of a mainstream nostalgia that turned longing into a commodity, a fashionable product that could be purchased in the city’s music stores or experienced first-hand in its entertainment venues, tailored to the needs and desires of an urban population who no longer dreamt of returning to the pastoral nature that Adolphe Adam or Hortense de Beauharnais had first set to music when political or social exile was far more common. By the onset of the Great War, nostalgia had been fully domesticated. And this is perhaps where it reveals itself most clearly as an ‘urban desire’.

Tristan Paré-Morin is an adjunct professor of musicology. After having completed his PhD at the University of Pennsylvania and taught at the University of Ottawa, he now works at the Orchestre Métropolitain as Head of Programming for Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Dr Paré-Morin’s research centres on nostalgia in musical works and listening practices of nineteenth- and twentieth-century France and North America. His dissertation on nostalgia in post-World War I Paris was funded by a Chateaubriand Fellowship. He has also written about the music of John Williams. His work is published in book chapters and journal articles in English and French.