Background and objectives

Over decades, the functional purpose of home care in Canadian policy has shifted from social wellbeing and wellness promotion towards medicalization, maintenance, and diverting people from institutions (Ceci & Purkis, Reference Ceci and Purkis2011; Funk, Reference Funk2013; Marier, Reference Marier2021). To the extent that restorative or ‘reablement’ opportunities in home care are considered or studied, the focus is typically on specific clinical or primary care interventions (i.e., Bødker et al., Reference Bødker, Christensen and Langstrup2019; Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2009). Meanwhile, home care programs across Canada have tended to prioritize ‘quick fix’ approaches and ‘substitution’ for institutional care, with increasing restrictions on the availability of and access to publicly funded home care supports for chronic and long-term conditions (e.g., Penning et al., Reference Penning, Brackley and Allan2006).

This situation can disadvantage older adults with chronic long-term needs, as well as their family carers (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Thompson, Berkowitz, Young and Ward2011; Chen & Berkowitz, Reference Chen and Berkowitz2012). Advocates and researchers argue for the vital importance of home care service for well-being and social inclusion (Grenier & Guberman, Reference Grenier and Guberman2009; Spring et al., Reference Spring, Funk, Kuryk, Warner, Macdonald, Burke and Keefe2024). Complicating discussions about the value of different goals and approaches to supports at home, however, is that definitions of home care are frequently unclear in research and practice, with benefits being difficult to track (Contandriopolous et al., Reference Contandriopoulos, Stajduhar, Sanders, Carrier, Bitschy and Funk2022; Ceci & Purkis, Reference Ceci and Purkis2011).

Longitudinal quantitative studies have generated knowledge about the value and benefits of home care for persons with long-term chronic conditions, who often need to access appropriate supports at critical points (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2017; Gaugler et al., Reference Gaugler, Kane, Kane and Newcomer2005). Research has further described how informal and formal care trajectories intersect in later life, highlighting variation related to levels of needs and function, social integration, and family contact, as well as living arrangements, age, income, and other structural factors (e.g., Kjær & Siren, Reference Kjær and Siren2020; Li, Reference Li2005; Penning et al., Reference Penning, Cloutier, Nuernberger, MacDonald and Taylor2018). Overall, such research tends towards decontextualized descriptions of population-level service use, and limitations in datasets and variables can lead to a focus on medical measures and administratively classified outcomes. Explaining and contextualizing quantitatively identified changes and outcomes can also pose a challenge.

Longitudinal qualitative inquiry can produce nuanced and contextualized knowledge of the complex changes experienced by people supported by home care. Scott and Funk (Reference Scott and Funk2023) analysed how families experienced cumulative, structurally generated disempowerment across a temporal period spanning not only home care but transitions into residential care. Further, Ayalon et al. (Reference Ayalon, Nevedal and Briller2018) engaged life course theory to explore historical, relational, and temporal sources of change and stability for those aging in continuing care retirement communities. Decades earlier, Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Griffiths and Lyne2004) highlighted how unexpected contingencies, human responses, and relational processes shape complex and problematic trajectories of health and social care for adults recovering from stroke. Their findings, along with those of other scholars (e.g., Ceci et al., Reference Ceci, Purkis and Björnsdóttir2013), call for policies and services that accommodate this complexity. Although qualitative research has explored care setting transitions (e.g., hospital to home, home to residential care), as well as aging over the life course, there is relatively less examination of how aging and home care supports intersect over time.

To further longitudinal qualitative research on home care trajectories, we explored how changes in services and wellbeing are experienced by older adults receiving publicly funded home care for chronic conditions. With the goal of understanding how multiple types of changes unfold and are experienced in daily life, and though broadly guided by conceptual lenses of social gerontology, health promotion, and social inclusion/exclusion (as detailed further below), the approach was inductive. Our team had additional opportunity to examine how the COVID-19 context shaped services and wellbeing.

Research design and methods

Setting and research design. This project was a subcomponent of a larger mixed-methods study into how home care approaches shape older adults’ trajectories in two Canadian jurisdictions: Health Service Region A (for the purposes of this paper) is a mid-sized urban area in central Canada, and Health Service Region B includes urban and rural areas of one Eastern Canadian province (Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Funk, Knight, Lobchuk, Macdonald, Mitchell, Rempel, Warner and Stevens2020). While home care in both provinces is publicly funded, Region B, like most Canadian jurisdictions, delivers it through contracted private (for profit or not for profit) home care agencies, whereas Region A has public service delivery. In the early response to COVID-19, Region B’s home care program sanctioned blanket pauses to non-essential home care services for about 3 months, whereas Region A’s pauses rolled out on a case basis, albeit with strong emphasis on limiting service to that deemed most essential and for prioritized clients. Region A’s most acute service disruptions also continued for several more months than Region B, in the context of staffing shortages.

Although both qualitative and quantitative components of the larger study shared a common interest in analysing trajectories of service use and access over time, the administrative and qualitative interview data were not comparable, due to incompatible timeframes and samples. Qualitative data were thus analysed separately for this analysis. Qualitative interviewing faced some challenges during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 in Canada (requiring a shift to phone or Zoom interviews in many cases). However, this provided an opportunity to explore how the pandemic affected home care services and clients.

Longitudinal qualitative research (LQR) involves ‘the collection of two or more time points and the use of qualitative methods to capture and enhance understandings of time perspective and change over time’ (Ayalon et al., Reference Ayalon, Nevedal and Briller2018, p.753). Our LQR was guided by a case study approach (Flyvbjerg, Reference Flyvbjerg2006) to facilitate nuanced understanding of rich ambiguities, complexities, and closely intertwined contextual forces. The older adults’ trajectories were the focal point, which we learned about not only from them but also from consenting family carers, home care workers, case coordinators, and home care agency supervisors.

Recruitment and sampling. In both regions, public system home care coordinators conduct assessments and approve and allocate funding for services. Following institutional human research ethics and health authority research board approvals, these case or care coordinators (as they are referred to in each region, herein referred to as CCs) were recruited for participation by invitations via email or team meetings. Then, clients were recruited through project information provided by participating CCs, who were first asked to identify clients receiving home supports, with varying expected health and functional trajectories (decline, maintain, or improve). We selected from these lists for a mix of potential trajectories. Eligible, cognitively competent clients were receiving some form of publicly funded home support (not just home nursing) for chronic long-term conditions (i.e., not post-acute or short-term), for at least 1 month in their own homes (which could include seniors’ apartments but not institutional care or assisted living). Invitations were mailed until 12 clients were recruited and provided informed consent. We asked them whether there was a family member and home care worker that they would be comfortable with us approaching. Following this, we sought to recruit those individuals, if they consented. In Region B, the clients’ agency supervisors were also invited to interviews.

In total, 136 interviews were conducted with 53 distinct participants over three time points between July 2019 and July 2021. For 6 of the 12 cases, a family/friend caregiver participated. In Region A, 21 interviews were conducted at T1 with 19 people (as two of the CCs each served two distinct clients); 20 interviews were conducted at T2 with 18 people (the HCA for CC6 was no longer available); and 19 interviews were conducted at T3 with 17 people (two of which, Client5’s HCA and CC, were new to the study). In Region B (where supervisors were also participating), 27 interviews were conducted at T1 with 26 people (one CC served two clients), and 26 interviews were conducted at T2 with 25 people (4 of whom were new to the study – CCs for Client1 and Client5 [who also had a new HSW participating], and for Clients 4 and 6; at T2, there was no HSW interview for Client6). At T3 in this region, there were 23 interviews with 23 people, including two who were new to the study at T3 (HSWs for Client1 and for Client 4).

Interview process. Interviews were conducted at three time points using semi-structured interview guides. At Time 1, in-person interviews with all participants (conducted separately) asked about the number and types of services and support received by the clients, and their experience with the home care system, including suggestions or concerns. Time 1 data were retrospective. Time 2 and 3 interviews were conducted over telephone or Zoom (due to the onset of the pandemic) and sought to identify and describe changes experienced by clients – with their services, their health, and in their lives more generally. Four of this paper’s coauthors, as well as several trained research assistants, conducted interviews. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and proofed for accuracy.

Analysis. A broad social-ecological theoretical lens (Stokols, Reference Stokols1992) guided the analysis by directing attention to how client pathways shape and are shaped by interrelated events and forces not only at the individual or familial level but also more broadly (i.e., social environments, organizational systems, policy contexts). This broad theoretical approach was further enhanced with the use of the sensitizing concept of late-life social exclusion (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2016), which extends social-ecological thinking towards more targeted consideration of how organizational and policy-level forces can generate multidimensional barriers to older persons and their families’ ‘participation, in society, their access to resources, and their expressions of identity and personhood’ (Grenier & Guberman, Reference Grenier and Guberman2009; p.117).

Iteratively with data collection, interdisciplinary teams met regularly to review incoming data. Team members prepared descriptive summaries for each interview at each time point and for each complete case. We sought not to decontextualize or reduce data through discrete coding but to understand cases holistically over time. Broad thematic categories of forces shaping client trajectories (policies and formal supports; family/friend capacities; housing and social environments; income and individual characteristics) were identified as an analytic exercise to push our thinking further. The descriptive summaries guided analytic discussion about processes shaping clients’ trajectories. Cross-sectional analyses (of data at each time point across the sample) were followed by temporal analyses in which we explored what happened within and across cases over time (Audulv et al., Reference Audulv, Westergren, Ludvigsen, Pedersen, Fegran, Hall, Aagaard, Robstad and Kneck2023; Thomson & Holland, Reference Thomson and Holland2003). We were further guided by Ayalon et al. (Reference Ayalon, Nevedal and Briller2018), who highlight the complexity of ascertaining change or stability through LQR. We discussed and frequently checked various kinds of changes that participants described, including the pace, frequency, and timeframe of change. This primary analytic attention to the details of reported change was paired with a more supplementary, interpretive (social constructivist) analysis (Cresswell, Reference Cresswell2013) of how various participants spoke about and understood the meanings and impacts of changes.

Results

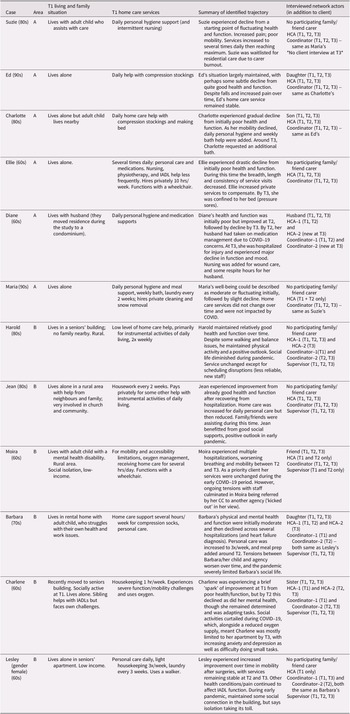

Below, we present our analysis of how changes in services and wellbeing were experienced by participants, starting with everyday experiences of disruptive, imposed changes in services and workers, which were amplified during the early onset of the pandemic. We then explore the complex changes in client wellbeing over the study, illustrating how changes sometimes resisted neat classification. Changes in social, emotional, or relational aspects of clients’ lives were less obvious to CCs in both regions, despite their relevance for longer-term trajectories and outcomes. Table 1 provides a general overview of clients’ life circumstances; pseudonyms were used throughout.

Table 1. Overview of clients’ circumstances

Change as everyday disruption in services. Clients’ longer-term wellbeing was shaped, in part and often indirectly, by their experiences of micro-temporal or daily changes – specifically by disruptions to service schedules and workers, even if the level or type of service appeared largely unchanged. Most older adults and families described their services as infused with disruptive changes in schedules, workers, and routines over which they had no control (including cancelled visits). At the same time, some expressed how difficult it was to make any agentic changes they wanted or needed (e.g., to shift a visit so they could dine out with others). This lack of control is a form of social exclusion and oppression (Grenier & Guberman, Reference Grenier and Guberman2009).

System inflexibility offered few options for participant-initiated and desired change, although there were exceptions. For instance, prior to the pandemic, Barbara prompted her agency to change her worker when she expressed her strong preference for female workers. The same agency also changed staffing when Barbara reported a worker had been rude to her. Moreover, in Region B, clients appeared to be called by service agencies the night before a visit to arrange a suitable time, suggesting more programmatic flexibility or communication may be built into delivery in that region.

Imposed schedules and worker changes created work for clients and families to coordinate and communicate with their CCs, replacement workers, and other family, where available, to get needed support. This added time and energy demands. For instance, Lesley expressed concern and about the challenges of explaining her care routine to new workers, a problem exacerbated by staffing shortages during the early pandemic. Other clients and families were limited in their ability to schedule other activities into their daily lives (affecting social inclusion). Some experienced distress when they were previously unaware of visit cancellations or replacement workers. As described by Diane:

I wish they’d be more prompt on [letting me know] if they can’t come, or they’re going to substitute someone. You could have gone out for the afternoon and suddenly, it looks like a no-go because there’s a home care worker at your door…it definitely disrupts my activities.

Disruptions were also more problematic for clients without family nearby, and whose care needs were more urgent or extensive. In this regard, Ellie’s comment below was a narrative rejoinder to institutionalized reliance on family involvement (Funk et al., Reference Funk, Kuryk, Spring and Keefe2024):

I was told, and I knew that home care is not a guaranteed service, don’t count on it. The trouble with that is it assumes you’ve got back-ups. And myself, because I am alone here without family support, I don’t have the kind of backups that people with family have. And so, I think the service needs somehow to be able to accommodate people like me …who need it, absolutely need it and have to count on it.

In Region A, ongoing service changes exacerbated already existing uncertainty related to significant health service transformation over several years prior to the study. Some clients expressed uncertainty related to the risk of possible future home care service changes in this context (i.e., tied to system transformation). Ed’s home care worker further expressed that many of his clients were worried about the (then) upcoming election:

Most of them, they worry about this one, ‘Oh they are going to change it, the health system?’ Just imagine, those clients they have different health problems and they worry, on top of that they worry about their personal care…If this one is changing, ‘oh they are going to lose all this?’ ‘How we can survive without home care?’ ‘How we can do everything by ourselves?’

In both regions daily disruptive changes not only added time and energy demands for clients and carers and limited daily lives, but contributed to feelings of loss of control, frustration, anxiety, and distress. In the next section, we illustrate how additional precarity and service disruption were introduced by the pandemic, compounding these patterns. We also see how these disruptions negatively affected clients and families’ relationships with workers and use of and access to service, with these effects being differentially distributed.

Change and the COVID-19 pandemic. After the onset of the pandemic, new and exacerbated service-related disruptions and their impact became prominent in client and carer narratives, particularly in Region A, which had a more extended service ‘pause’ and subsequent challenges related in part to staffing crises (COVID-19 hit long-term residential care more severely in this region).

At T1, Ellie had a busy lifestyle and was a vocal self-advocate for her needs and services. She received the maximum allocated service hours for her complex chronic health issue and had no family nearby. At T2, most of her services appeared to be either shortened or cancelled; Ellie hired private agency help out-of-pocket to fill the gaps, leading to financial strain. Because of the visit reductions, Ellie experienced health decline. By T3, she had significant skin breakdown due to pressure sores and was almost entirely unable to leave her bed for 2 months. She could no longer leave home for social activities.

Although few other clients appeared to experience such direct and prolonged service precarity due to the pandemic, many were affected by the pandemic’s other more indirect impacts on home care services, especially as scheduling, staffing, and cancellation challenges manifested more intensely in the sector (assessments were also impacted, as discussed in the next section). Everyday service disruptions ranged from small but meaningful changes to clients’ daily routines to more significant changes and some that represented de facto service reductions. For instance, this included visits rescheduled to inappropriate times; visit times shortened (e.g., Diane’s tub bath was switched to a sponge bath); service cancellations; new, unfamiliar workers sent more often; and fewer supplies. After the onset of the pandemic, Barbara, who received help with compression stockings for managing edema, expressed that re-scheduled timing of workers’ arrivals sometimes defeated the purpose of their visit (conveying frustration):

I’ve seen them call me on a Thursday to tell me they didn’t have anybody in the morning for Friday. The earliest they could get somebody would be 2 o’clock in the afternoon….it means that 3:30 they’re putting my stockings on. The day’s gone. It’s too late. You know, [the stockings] are not going to do anything at that point.

Moira expressed her frustrated feelings around being rushed, after describing scheduling changes:

…getting my breakfast at 10:00 and they scheduled lunch for 11:00. Don’t make any sense….[as well as] giving me supper at 5:00, and my tuck-in at 7:00. It takes me at least a half an hour to eat…then I have to let my food settle before I take my last pills.

Worry was also evident in some clients’ narratives, exacerbated by the larger context of pandemic-related uncertainty. Charlotte was particularly worried about scheduling inconsistencies, as she did not want to appear to be violating COVID-19 policies at the time (i.e., having too many people in her home). She was afraid that home care workers might arrive when her family or hairdresser were present, which caused significant distress.

At T3, Harold described his increasing uncertainty about home care worker arrival times, which departed from previous practice, when he was typically notified the day before. He expressed some ambivalence about this:

At first, I didn’t like it very much, I thought it was going to be an all-day affair that I would have to wait. I didn’t like that but then they told me that they would be here sometime in the morning.

Harold sometimes had to call about revised arrival times, adding, ‘it’s kind of a nuisance – but overall, it’s not bad’. Depicted by staff as ‘compliant’ and ‘a sweetheart’, Harold’s apparent ambivalence may be attributed to his easy-going disposition.

For some clients, COVID-19 protocols, alongside pandemic-related strain on families and workers alike, appeared to further disrupt already fragile relationships with services/workers. Like Ellie, Moira started the study with high care needs and could be described as empowered or outspoken. Her co-resident family member experienced mental health challenges. Moira’s home support worker said Moira’s services were not paused because she was considered a priority client. By T3, however, Moira had a conflict with the new agency manager and disagreed with a policy related to her equipment that was introduced due to the pandemic. The situation escalated, and Moira believes she was ‘kicked out’ of the agency because of her criticisms about her care and her extensive needs. Her prior conflicts with workers likely also played a role. The CC helped Moira find alternative care arrangements.

The lives of clients in better health at T1 were relatively less impacted by home care service disruption. Having higher incomes, available and capacitated family support, and community connections also appeared to help mitigate emotional and material impacts of care gaps and changes. This occurred primarily through access to backup supports but also through how these resources enhanced mood and mitigated emotional impacts of disruption. Such advantages also tended to be associated with a more positive mood or life outlook, and these participants were also often held in high regard by their care workers. Such participants (e.g., Harold, Jean) appeared to be buffered from impacts of the social upheaval associated with COVID-19 on their lives.

Alternatively, clients with more precarious health, relational tensions with staff, and limited social supports were more vulnerable to negative impacts during the early pandemic, especially in terms of their own (and their carers) social, mental, and/or emotional wellbeing. For instance, Barbara said her health went ‘downhill’ and her social life was sharply curtailed. By T3 her adult child had taken stress leave from work and raised with Barbara the idea of her moving into long-term residential care. This situation was compounded by conflicts with the agency arising from workers’ perceptions of hoarding and that Barbara’s child was inappropriately using or personally benefitting from Barbara’s service. As further evidence of this tension, when asked if her own needs had been assessed by the case coordinator, Barbara’s daughter replied:

No. In fact, during the meeting, um, one of the people made the comment that my mother had an able-bodied person here, and she didn’t get to say anything more because I was laughing my head off. I was going, ‘I’m not able-bodied’.

As a further example, Charlene, who was living with a low income at T1, had recently moved to a seniors’ apartment complex. This move, along with a new scooter, sparked renewed purpose and belonging in Charlene and an increase in mood, physical activity, and interaction, although her function and mobility were quite limited, and she required home oxygen. Visit and gathering restrictions during the early pandemic period, alongside reduced funding for Charlene’s portable oxygen supply and unreliable accessible transportation scheduling, generated considerable distress and worry for Charlene. She tearfully attributed a deterioration in her mental and physical health to these restrictions but insisted that she was ‘not going to sit in a chair and give up’. Due to her own health issues, Charlene’s sibling became less able to help with groceries and similar tasks over this time. By T3 Charlene said her own health had gone further ‘downhill’ and was depressed. She was using oxygen ‘twenty-four-seven’, rarely left her home and was too exhausted for many simple activities.

Overall, clients’ experiences highlighted how COVID-19-related service change and disruption could lead to worsened mood and distress (frustration, uncertainty, fear, loss of control), strained family – worker relationships, and for some, unmet needs. The emotional, relational, and social impacts, compounded by the broader impacts of the pandemic on participants’ lives and agency, appeared amplified for those in more disadvantaged circumstances. In turn, these appeared to impact physical health and function, though such impacts were more readily discernable in some cases than others over the period of data collection. Delineating change and impacts in qualitative data, however, is complicated by the complexity of qualitative change over time, as detailed below.

Change in wellbeing as subtle, complex, and multifaceted. Changes in client wellbeing were not straightforward or easily categorized, in part reflecting the multifaceted nature of wellbeing that generate the potential for different aspects of wellbeing to change in divergent directions (i.e., branching, where one dimension increases and another dimension decreases simultaneously). Fluctuation over time in the gradient of a particular dimension (i.e., improving then decreasing or vice versa) was also evident. Moreover, a change in one aspect of wellbeing might be subjectively experienced by a person as more difficult to manage or impactful in the context of their lives and resources, thus impacting their overall wellbeing more extensively than other changes.

Illustrating a ‘branching’ trajectory, Lesley experienced some improvement during a period where other challenges persisted – her mobility improved following knee surgery (e.g., by T3 she no longer required her cane indoors and Lesley self-reported improvement), yet due to arthritis, pain, and other health conditions, standing tolerance continued to be a problem, affecting meal preparation and grocery shopping. Illustrating a ‘fluctuating’ trajectory (e.g., improvement followed by decline) was also possible. At T1, Suzie’s CC identified her as someone with a lot of ‘peaks and valleys’ in managing her needs and health, with variation in her function, mood/resilience, and support needs (her co-resident family carer’s capacity/availability also fluctuated). Initially Suzie’s surgery prompted home care service, following which her mobility improved somewhat, leading to service reduction. Then, a policy change by her transportation provider (requiring her to independently get down three steps with her walker) increased her anxiety and limited her community social interactions – another example of social exclusion. Suzie had been depending heavily on her co-resident adult child for meals, housekeeping, and now increasingly, for transportation. Then, a fault in her walker led to Suzie sustaining injuries, and short-term nursing services were put in. By Time 3, her worsening incontinence and declines in health and mood had increased her child’s feelings of burnout (despite some service increase) and resulted in Suzie’s move to long-term residential care. Suzie’s CC for instance indicated: ‘we could have [increased services], but the fact is that the son didn’t really want her to come back home anymore and he was burnt out, but he didn’t really want to say that’. Ultimately, Suzie’s daughter appeared to have intervened to make the decision, on behalf of her brother, about Suzie’s move into long-term residential care.

Diane also appeared to have some initial improvement after T1 followed by a mental health decline that was not easily addressed in assessments or through formal supports. At T1, Diane was experiencing mental health challenges complicated by her husband’s lengthy hospital stay due to surgery complications. Following this, the couple moved to an accessible apartment; Diane’s mood improved in part due to the move and to her husband’s health improvement. She took on more tasks and showed renewed interest in hobbies. However, by T3, a fall impacted Diane’s mobility and function, with implications for her mental health. Diane’s home care supports themselves were largely unchanged or decreased somewhat as her husband’s physical function improved (his own home care supports also ended), and intermittent wound care nursing was added after Diane’s fall. At T3, Diane’s husband requested and received three respite hours, as he was feeling burnt out. His own mood tracked a similar path of improvement followed by increasing deterioration, partly due to social isolation and to caregiving. He stated:

[CC] got me the respite, for me. Because I sort of explained, I just didn’t want to leave [Diane]. You know, every time I went out, I would be [out] for like 10 minutes, I’m afraid if she fell, and I wasn’t here to help her. And at least [respite] takes that load off. And it’s only 3 hours I get, but then I can plan my route out and do everything in advance, I can do it in 3 hours. So, I’m okay with the 3 hours. And I appreciate the 3 hours that they’ve given me, so. But it would be nice if I could get away from here (laughs) and do nothing.

Various supports and connections including but extending beyond home care (informal and community supports, housing) intersect with access to private resources to shape clients’ trajectories in complex ways over this time. Such supports and resources often mitigated the impact of home care service disruptions experienced by some clients and their families. Ultimately, given the complexity of change processes and intersecting factors shaping wellbeing, changes were not always apparent to or assessable by CCs, as described below.

System awareness of and responsiveness to change in wellbeing. Although most (but not all) client participants experienced some decline in an aspect of wellbeing, for some this was gradual and subtle (especially in social and emotional wellbeing), and for others more drastic and/or steep (often in physical health or due to a fall or injury). Gradual or subtle changes were not always formally assessed or known to the CC (or agency supervisor, in Region B). Most often, these were brought to the interviewer’s and/or CC/supervisor’s attention by the client, their family member or a home support worker.

Home care systems appeared most directly responsive to clear changes in clients’ physical health and function and needs (e.g., precipitated by discrete events like injuries, hospital discharge, and acute medical complications) or in response to expressions of need or requests by the client or carer. For instance, Jean’s services were increased to daily personal care for about 1 month post hospitalization and then reduced as she healed. Increased supports were implemented as respite for Diane and Suzie’s carers, and an extra hour of personal care was added weekly to support Barbara’s carer, at families’ request.

Other changes in clients’ wellbeing and needs for help at home appeared to have been less visible to CCs when they involved potential precursors or non-physical dimensions of client wellbeing, in contrast to physical condition or function. This included, for instance, changes in mental health and social wellbeing, or shifts in living arrangements, housing, and family.

Moreover, when workers and CCs were asked about clients’ likely future trajectories, their responses tended to convey a belief that clients are likely to decline because that is what happens to most older adults. For instance, although Harold’s overall health had maintained over the project, his care aide said he would ‘probably decline’; likewise, Jean’s CC at T2 said that although Jean was doing well, given her age she eventually would decline. Not only did these comments not anticipate how changes in social circumstances (such as housing) could improve clients’ wellbeing, but they may represent a limiting expectation based on ageist, biomedical, or reductionist assumptions of physical decline.

Complicating things further, re-assessments by CCs were impacted by the changing status of the pandemic and home support client priority levels. Especially during lockdowns (more extensive in Region A), CCs were more likely to conduct informal ‘check-ins’ than formal assessments and to conduct these by phone rather than in-person at the home. Heavy workloads were also a factor: for instance, CCs for Ed (T2), Lesley (T3), and Jean (T2) all said these clients were due or overdue for a reassessment but that this was unlikely to happen soon due to staffing shortages and heavy workloads (leading to higher-needs clients being prioritized for reassessments). For Diane and Harold, CC turnover also contributed to delayed assessments: the new CCs had not yet connected with them at T2.

Harold’s new CC believed Harold was ‘doing well’ because of what they read in his agency’s progress reports. When in-person assessments were less regular, CCs may need to rely more heavily on input from clients, families, or workers (and in Region B, agencies) to contact them with any issues with services or changes in care needs. They may also rely more on generalized assumptions, as in the following example from one agency supervisor:

[Charlene] moved into my area about a year ago. Her services just kind of tick a long quite well. So, with those clients that are adequately provided with care – and not a lot of health changes – then they just kind of tick a long quite well, and we don’t really hear from them.

Although home support workers see, communicate and interact most regularly with clients, one worker expressed concern (at T3) that their own observations and suggestions regarding changes in clients’ needs were often not acknowledged by CCs:

P: Sometimes I have to phone quite a few times to get an answer. And it gets, you know, we don’t always get taken seriously.

I: Oh. Aren’t you supposed to be kind of the eyes and ears to let them know?

P: Well, that is the slogan, but that’s not always what happens!

As such, some clients may go without additional services, jeopardizing safety or wellbeing, especially if they were more reluctant to ask for help, whether due to mistrust, pride, or not wanting to ask too much of workers.

Finally, clients’ socio-emotional wellbeing and energy can delimit their access to home care services, especially in a system that might on the surface be responsive, but not in a way that meets the person’s needs. This was the case for Charlene, who stopped meal preparation services because she said it was too stressful to find someone to help her get groceries before the worker arrived. At T3, Charlene also expressed she could not summon the energy to prepare for care aides’ arrival (e.g., preparing garbage to go out).

Discussion and conclusions

We engaged LQR to analyse and understand qualitative changes in home care services and client wellbeing, both in an everyday sense and over a data collection period spanning prior to and during the early years of the onset of the pandemic. Our in-depth exploration of qualitatively experienced changes in services and wellbeing among a small number of clients triangulated information between different home care actors. The results enhance our understanding of the complex social processes and mechanisms shaping clients’ trajectories, while also illuminating less obvious or less formally documented changes.

This study adds to our understanding of how service-related disruptions in home care, prior to and then amplified during COVID-19, can add work for clients and carers, constrain their daily lives, and contribute to feelings of disempowerment, frustration, anxiety, uncertainty and distress. Indeed, there is a growing body of knowledge about how clients and families experience poor scheduling reliability, cancellations, and worker inconsistency, including but not limited to the pandemic period (Funk et al., Reference Funk, Irwin, Kuryk, Lobchuk, Rempel and Keefe2022; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Maclagan, Schumacher, Wang, Jaakkimainen, Guan, Swartz and Bronskill2021; Martin-Matthews et al., Reference Martin-Matthews, Sims-Gould and Tong2013; Martin-Matthews & Sims-Gould, Reference Martin-Matthews and Sims-Gould2008; Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, Nesto, Hiebert, Warner, Luciano, Ledoux and Donelle2021). Service disruptions can affect client trajectories not only through their emotional, mental and social impacts, but by straining family/friend care as well as clients and families’ relationships with home care workers; and (for some clients) generating unmet needs and/or clients’ mistrust and refusal of services (Funk et al., Reference Funk, Stajduhar and Cloutier-Fisher2011; Reckrey et al., Reference Reckrey, Russell, Fong, Burgdorf, Franzosa, Travers and Ornstein2024; Sims-Gould & Martin-Matthews, Reference Sims-Gould and Martin-Matthews2010; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Kim, Yee, Zhang, Reckrey, Lubetsky, Zhao, Ornstein and Franzosa2023). As well as shaping trajectories, such disruptions fundamentally compound older adults’ social exclusion (Grenier & Guberman, Reference Grenier and Guberman2009).

The impacts of service-related disruptions in this study appeared compounded by the broader impacts of the pandemic on participants’ lives and agency. The impacts also seemed to be more acutely experienced by those in more disadvantaged circumstances (low-income, poorer health, and with less family or community support). Supports and connections beyond home care (informal and community supports, housing) intersect with access to private resources to either exacerbate or mitigate the negative impacts of home care service disruptions on clients and their families. Other research has also documented the need for support infrastructure external to home care programs, such as community-based social services and affordable housing; however, these sectors can struggle with funding and capacity (Leviten-Reid & Lake, Reference Leviten-Reid and Lake2016; Tong et al., Reference Tong, Sims-Gould, Lusina-Furst and McKay2021).

Finally, we documented how home care systems can be challenged to recognize and respond to changes in holistic client well-being, whether through assessments, referrals, or service adjustments. Home care systems appeared most directly responsive to clear changes in clients’ physical health and function and needs. System actors can fall back upon a narrowing focus on physical rather than social risk factors, alongside ageist and otherwise limiting institutionalized assumptions about clients and families, in an organizational (and pandemic) context which structurally incentivizes these patterns. Our findings add to others’ calls for a shift in home care towards person-centred approaches (Giosa et al., Reference Giosa, Holyoke and Stolee2019; Sanerma et al., Reference Sanerma, Miettinen, Paavilainen and Åstedt-Kurki2020) oriented to clients’ and carers’ emotional, social, and relational wellbeing and holistic life circumstances (Beech et al., Reference Beech, Ong, Jones and Edwards2017; Saari et al., Reference Saari, Giosa, Holyoke, Heckman and Hirdes2024). These aspects are often seen as ‘softer’ concerns and deprioritized within poorly resourced and task-oriented, medicalized systems. Home care coordinators also need to be structurally supported in providing case management (Contandriopoulos et al., Reference Contandriopoulos, Stajduhar, Sanders, Carrier, Bitschy and Funk2022), including connecting clients/families to external resources and supports. Moreover, well-resourced services would allocate and protect time for home care workers, and promote continuity (Contandriopoulos et al., Reference Contandriopoulos, Stajduhar, Sanders, Carrier, Bitschy and Funk2022). Such system changes could help ensure that, at very least, services are delivered in ways that promote long-term wellbeing and do not perpetuate social exclusion.

There are important equity-related concerns in terms of who can age ‘in place’ well, and for how long (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Watt, Mayhew, Sinn, Schumacher, Costa and Jones2024; Wyndham-West & Dunn, Reference Wyndham-West and Dunn2024). Without fully recognizing the myriad forces that shape wellbeing (within and outside of formal home care services), we risk obscuring the disproportionate impact of home care disruptions for low-income older adults, those without capacitated families or developed social networks, and those struggling with mental health challenges (Grenier et al., Reference Grenier, Burke, Currie, Watson and Ward2022; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Bacsu, Abeykoon, McIntosh, Jeffery and Novik2018; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Dansereau, FitzGerald, Lee and Williams2023). As home care programs narrow in scope, there is greater reliance on other community programs and resources, family/friend carers, and private purchase of services, all of which will continue to exacerbate inequities in aging in place. These issues can be addressed through robust funding that supports equity considerations in home care policy and planning. Examples include decoupling allocation decisions from assumptions about family or recognizing the health-promoting and equity-related significance of supportive services such as housekeeping. Democratic, participatory engagement of citizens and communities in program design can also promote equity and social inclusion in the sector (Lukindo et al., Reference Lukindo, Hamilton-Hinch, Dryden and Aubrecht2021; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Carroll, O’Shea and O’Donovan2024). Other recommendations stemming from this study’s findings include implementing clear processes for responding to concerns raised by workers; collaborating with clients/families around scheduling processes and care planning decision-making; and shifting from task-based to time-based care delivery models.

Qualitative research does not isolate independent effects of factors or variables; rather, qualitative ontologies typically view causal forces as inextricably intertwined, context-dependent, and multi-layered. One limitation of this study is that the time frame could not address longer term trajectories (i.e., beyond 2–3 years) in wellbeing or home care service use. Moreover, we did not, for privacy reasons, access clients’ charts or administrative data, which would have allowed us to compare and juxtapose our qualitative insights with these more limited forms of institutionally tracked information. That we were unable to identify strong differences in findings between the clients’ trajectories in the two regions despite differing forms of delivery was noteworthy and may suggest there are similar underlying processes shaping trajectories; however, conclusive determinations of provincial differences should employ larger samples and statistical controls.

Qualitative research departs from a more static, decontextualized, or compartmentalized approach to understanding the dynamic factors shaping people’s experiences. With LQR, our study represents an important contribution that illuminates the social and temporal contexts of home care clients’ (and their families’) lives. Findings contribute to more nuanced understanding and theorizing of trajectories among older adults receiving home care and suggest the need to integrate equity considerations in policy and practice.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number 155950). We appreciate the contributions of Pamela Fancey, Michelle Lobchuk, Pamela Irwin, and Lucy Knight to the project; the participants of the care constellations who gave of their time; and our partners the Winnipeg Health Regional Authority and Nova Scotia Health.