MATTERS OF LIFE AND DEATH

As Agamben (Reference Agamben1998) and others have noted, how death and the dead come to be organized is a fundamentally ethical consideration (see also Elias, Reference Elias1985). While discussions about organizational ethics tend to gravitate towards life and the living, recent global events including an ongoing climate emergency, the COVID pandemic, and emerging and ongoing wars, famine, and recession, coupled with social movements responding to racial, sexual, and homophobic violence, have contributed to a growing awareness of the many ethical challenges attached to how dead and dying people are treated (Oxfam, 2022; Skeggs, Reference Skeggs2021). In various ways, these events and the considerations they give rise to have starkly brought to the fore how some bodies come to “matter” more than others (Butler, Reference Butler1993, Reference Butler2022), and what this means both in life and in death. As a potentially reflexive moment (Parker, Reference Parker and Parker2020), the current era arguably has the capacity to be marked by the compulsion not to “look away” (Courpasson, Reference Courpasson2016), requiring us instead, to critically and reflexively consider what our response to this “moment” and the challenges it presents might tell us about who and what is recognized as being of value, in life and beyond.Footnote 2

While there is a growing interest in death in the field of management and organization studies (Ashley, Reference Ashley2016; Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2008; Jagannathan & Rai, Reference Jagannathan and Rai2022; Le Theule, Lambert, & Morales, Reference Le Theule, Lambert and Morales2020; Reedy & Learmonth, Reference Reedy and Learmonth2011; Smith, Reference Smith2006), academic research tends to reflect a wider social discomfort with death and “our common aversion to close proximity to it” (Byers, Reference Byers2022: 9). Yet encounters with death and the dying are for many, everyday work experiences, including for those who undertake the “necessary yet undesirable work” of organizing and handling dead bodies (Jordan, Ward, & McMurray, Reference Jordan, Ward and McMurray2018; Ward & McMurray, Reference Ward and McMurray2017). Mahalingam, Jagannathan, and Selvaraj’s (Reference Mahalingam, Jagannathan and Selvaraj2019: 213) study of the Dalit people who cleaned the streets and toilets in the Indian city of Chennai in the aftermath of floods in 2015 shows how “handling” death can involve working in “appalling and unsafe conditions.” Like Jagannathan and Rai (Reference Jagannathan and Rai2022), their account shows how the shame and stigma attached to working with dead bodies, including those of humans and animals, intersects with class inequalities and caste-based injustices. Research also shows how others, such as policymakers, politicians, and administrators, “handle” bodies in more mediated ways—for example, by contributing to decisions that have life or death consequences (Le Theule et al., Reference Le Theule, Lambert and Morales2020: 523). The responses to these kinds of mundane and extreme circumstances are grounded in normative expectations shaping perceptions of value attributed, for instance, to ideals such as independence and self-sufficiency. They involve complex and fundamental questions about who and what “counts” as a liveable life, and how dead bodies should be handled in ways that recognize and respect their dignity.

In order to consider these issues, and to subject norms underpinning the organization of life “beyond death” to critical scrutiny, we examine death—or more specifically, the treatment of dead people and/as bodies—as an organizational and organized phenomenon by comparing the aesthetics, poetics, and ethico-politics (Linstead, Reference Linstead2018) of two distinct island cemeteries: San Michele in Venice, Italy, and Hart Island, located off the coast of New York City. We selected these two cemeteries for their intriguing mix of similarities and differences. Both situated on islands, they respond to the need to separate living beings from the dead while efficiently utilizing increasingly limited space. However, they diverge significantly in terms of their occupants, visitors, organization, architecture, and atmospheres. The former is a renowned and aesthetically pleasing tourist destination, while the latter is a neglected site characterized by a series of anonymous mass graves. Comparing these two distinct settings enables us to examine how death is organized, and dead bodies are “handled” very differently in both settings.

Our aim, in examining these two cases, is to think critically and reflexively about how dead bodies come to be subject to organizational processes and practices in distinct settings, and to examine what we can learn from this. We do so through the lens of a recognition-based ethics and politics of relationality, one that is of increasing interest to scholars in management and organization studies, and which foregrounds the idea that collective solidarity, accountability, and relationality (Painter-Morland, Reference Painter-Morland2007) can only emerge from mutual recognition of our most basic inter-connectedness (Antoni, Reinecke, & Fotaki, Reference Antoni, Reinecke and Fotaki2020; Fotaki, Islam, & Antoni, Reference Fotaki, Islam and Antoni2020; Mandalaki & Pérezts, Reference Mandalaki and Pérezts2023; Shymko, Quental, & Navarro Mena, Reference Shymko, Quental and Navarro Mena2022), forcing us to cease “looking away” (Courpasson, Reference Courpasson2016) from phenomena we find difficult or confronting, including death and dead bodies.Footnote 3

Drawing from this emerging stream of thought in management and organization studies, we use the term “ethics” here and throughout the paper to refer to both a way of relating to ourselves, others, and things (including the environment in which we live and die) based on recognition of our mutual inter-dependency and vulnerability (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]; Reference Derrida1999), and to a reflexive awareness of how that vulnerability is differentially situated (Butler, Reference Butler2022). In other words, we adopt a recognition-based view of ethics,Footnote 4 and of ethical relations, as grounded in a belief that while we are all mutually inter-dependent and vulnerable in an existential sense, we are by no means not equally so, at least not sociologically speaking (Butler, Reference Butler, Butler, Gambetti and Sabsay2016, Reference Butler2022).

Adopting this approach, and bringing it into dialogue with insights from scholarship on grieving and mourning, we begin from the premise that an ethical life and death requires us to commit to a critical, reflexive, and hopeful reconsideration of how we might create alternative conditions of possibility for relational modes of organizing that affirm, and enact, affective bonds of solidarity (Vachhani & Pullen, Reference Vachhani and Pullen2019), in life and in death. In this sense, the paper contributes to conversations currently exploring the possibilities that might support more dialogic, affirmative modes and relations of organizing, drawing from, and contributing to a growing interest in the ethical and political potential attached to a relational ontology (Bell & Vachhani, Reference Bell and Vachhani2020) and to affective bonds of solidarity (Johansson & Jones, Reference Johansson, Jones, Harding, Helin and Pullen2020; Mandalaki, Reference Mandalaki, Fotaki and Pullen2019; Pullen & Vachhani, Reference Pullen and Vachhani2020; Smolović Jones, Winchester, & Clarke, Reference Smolović Jones, Winchester and Clarke2021). This recognition-based approach to ethics, drawing on the works of Butler and Derrida, provides an alternative to the modern, rational, and autonomous self-centred approach that has tended to dominate business ethics discussions to date (Gustafson, Reference Gustafson2000; Loacker & Muhr, Reference Loacker and Muhr2009), offering rich insights into how “we act ethically in relation” (Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann2022: 565). In particular, we respond to the idea that organizational processes and practices “beyond death” need to be opened up to further critical scrutiny, in order to engage with the ethical possibilities that doing so might lead to, including understanding—and organizing—the handling of dead bodies in more socially, environmentally, and ethically responsible ways.

Thinking about embodied life, and death, in this way, and in this context, reminds us of just how mutually inter-dependent we are. In sum, a recognition-based approach to ethics (Butler, Reference Butler2022; Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]) highlights that social relations and solidarity can only emerge from a mutual recognition of our embodied relationality and shared inter-corporeal vulnerability. In this paper, we aim to show how our vulnerabilityFootnote 5 when and after we die is a poignant illustration of this, one that opens up new possibilities for re-imagining more ethical and sustainable modes of organizing, including of organizing our bodies when and after we die, in the future.

Working from these starting points, we explore the two island cemeteries considered here as providing insight into the ethical question of whose lives are understood to be of value (worthy of recognition), and of why certain lives are valued more so than others. We examine what this means for how our lives, and our desire for recognition, come to be organized in life and in death. By shedding light on the ethics of life and death implicit within human efforts at organizing, we hope to contribute to the evolution of ideas leading to more socially, environmentally, and ethically responsible ways of organizing, and interring, dead bodies in the future. With this in mind, we set out to address two related questions: First, what can we learn about organizational ethics from studying cemeteries as organizational/organized manifestations of our mutual, embodied vulnerability? Second, how does, and how should, the ethico-political imperative of death and the deceased materialize in the cemeterial space?

Structure wise, we begin the paper by positioning it in related bodies of literature on death, dying, and burial, drawing from research in management and organization studies, and on grieving and the work of mourning in social theory and philosophy. We bring these literatures together to study “resting places” as organizational settings that materialize differential value, developing an ethical critique of what this involves. The methodological approach that we took to analyse the two cases is then outlined, followed by a presentation of the case-study material, based on the San Michele cemetery, Venice and Hart Island, New York. These two examples are compared in order to develop an ethical critique of San Michele as a place of reified, highly individualized recognition and of Hart Island as a site of negation. In the final part of the paper, we draw from current discussions on recognition and relationality in light of the case-study analysis to map out the relevance of the paper’s empirical and theoretical contributions to evolving concerns with the ethics and politics of grievability (Butler, Reference Butler2004, Reference Butler2022) as a process through which our desire for recognition in life—and in death—comes to be organized. We conclude by summarizing our contribution to existing scholarship on organizational ethics and outlining potential avenues for future research.

CEMETERIES AS ETHICALLY SIGNIFICANT ORGANIZATIONAL SETTINGS

Sociological research has highlighted how modern rationalism has changed our relationship with death in at least two fundamental ways. With the diffusion of scientific discourse and a secularization of values, death has come to be regarded as an increasingly private, individual matter (Mellor & Shilling, Reference Mellor and Shilling1993). At the same time, the “disappearance” of death from the public sphere has required an increased effort to organize it, to make it “manageable.” Thus, encounters with death are increasingly mediated, sanitized, and institutionalized (Reedy & Learmonth, Reference Reedy and Learmonth2011; Smith, Reference Smith2006). Death has been “sequestrated” (Giddens, Reference Giddens1991) by professions, organizations, and practices whose aim it is to “manage” death and dead bodies, giving rise to a complex, and profitable, death industry. Insights to be gleaned from this research include an understanding of how the organization of death involves a combination of economic, political, cultural, spiritual, and theological, as well as ecological and ethical considerations (Pava, Reference Pava1998), foregrounding the gendered, class, and racial conditioning of the struggle for recognition and dignity in death and in work involving the handling and processing of dead bodies. Such research has also highlighted the necropolitical contours of capitalism and colonialism (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2008) shaping the contemporary death industry, and the “force of separation” (Mbembe, Reference Mbembe2019: 1) as an organizing principle governing the treatment of those whose lives and bodies are deemed dispensable.

While this research has reflected on how proximity to death and to dead bodies can prompt a sense of vulnerability, reminding us of our inter-dependence with others (Butler, Reference Butler2022; Yu, Reference Yu2021), how these differential proximities and vulnerabilities come to be organized and situated in distinct settings has yet to be fully explored within the field of management and organization studies. Cemeteries, and the rites and rituals they involve, are places that, often in highly organized ways, guide us through some of the existential, and ethical, challenges that death presents us with. In this sense, cemeteries are ethically significant organizational settings that materialize recognition—or its absence. They do not simply offer a practical solution to the disposal of dead bodies but are settings where a sense of our entwined, mutually vulnerable social existence can be signified, and where an affective sense of ourselves and others as “mattering” is played out. In this respect, individually marked graves are widely regarded as important signs of recognition, providing points of connection and continuity in the face of loss that act as signifiers of the value attributed to us and those we care for. As settings where bodies and memories meet, cemeteries are, therefore, highly organized places that materialize the differential attribution of value to people in life and in death (Ashley, Reference Ashley2016), acting as possible points of recognition, commemoration, and connection (Cutcher, Dale, Hancock, & Tyler, Reference Cutcher, Dale, Hancock and Tyler2016; Francis, Reference Francis2003). This means, conversely, that the absence of such signifiers can silently but poignantly speak of the opposite. Commemorative markers and practices, and the social relations they signify can therefore help to maintain individual identities (and, e.g., in the case of war memorials, their affiliations), and affirm their continued social existence, organized through the demarcation of burial spaces (e.g., via a grid-based layout) where grave plots are located, delineated, and identified by named markers. Francis, Kellaher, and Neophytou (Reference Francis, Kellaher and Neophytou2005) also show how this takes place on a more collective level, with, for example, different communities potentially reinforcing boundaries and/or recreating diasporic evocations of “home.” They note how cemeteries, in this sense, are settings where intensely meaningful and socially significant landscapes of memory are shaped over time, ritual, artefact, and place.

Meeting the need for individually marked graves is a growing practical concern, however, particularly in densely populated urban environments, yet burial continues to be the preference of the majority of the world’s population. This combination of a lack of space and enduring beliefs is coupled with the often-prohibitive costs of burial, reminding us that for many, access to a “good death” is widely precluded by enduring social inequalities shaped by “historic systems of oppression, exploitation and marginalisation” (Byers, Reference Byers2022: 2).

Broadly speaking, the management of the dead in urban environments has always posed practical and ethical problems for the living, particularly for a city’s poorest people. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, rapid population growth in global cities intensified pre-existing concerns around space, sanitation, and changing sensibilities towards the management and visibility of death (Foucault, Reference Foucault and Faubion1998 [1967]; Ross, Reference Ross2020). In major Western centres such as London, Paris, and New York, this led to the closure of many inner-city burial spaces and the establishment of cemeteries further afield, including many so-called garden cemeteries.

The two island cemeteries considered here are examples of the practical and ethical issues raised by the long-term problem of where to situate relatively large numbers of dead bodies in urban settings in which space is limited (i.e., Venice, Italy and Manhattan, NYC), in which “burial cultures” and related beliefs predominate, and in which the need to separate burial spaces from inhabited areas, while making the former accessible, is a significant and ongoing logistical challenge raising questions about how dead bodies are interred now and in the future in ways that are sustainable, affordable, and ethically defensible.

AN ETHICS OF GRIEVABILITY AND THE GIFT OF RECOGNITION

To reflect on and respond to some of these challenges, we turn to Butler’s theory of grievability (Reference Butler2004, Reference Butler2022) and Derrida’s ethico-politics of survivance (Reference Derrida2006 [1993], Reference Derrida1999) in order to consider how and why death poses ethical questions and how the ethico-political imperative of death and the deceased materializes in spaces like cemeteries.

Building upon Heidegger’s philosophical reflections on death, time, and existence, Derrida (Reference Derrida2006 [1993]) argues that the ethical imperative, “how ought I to live?” can only be answered through an encounter with death and the other. The lessons of life cannot be solely taught through personal experience, but rather are learned through the death of others, as it is through others’ deaths that we come to understand the meaning and significance of our own existence (Derrida, Reference Derrida1999). Death, in this sense, is never truly “our own,” for it is an experience that cannot be experienced. It follows that mourning the loss of others is more fundamental and essential to our existence than mourning our own death, and that death is ethically significant in the way it defines our relationship with others (Derrida, Reference Derrida, Brault and Naas2001). Death represents the most “ex-propriating” possibility and reveals alterity while simultaneously constituting the most powerful event of singularization, the utmost individual possibility, as nobody can take the inevitability of one’s death away (Derrida, Reference Derrida1999).

Derrida introduces the concept of “survivance” to deconstruct the life-death binary and explain the implications of death’s aporethic character (Derrida, Reference Derrida1993). The suffix “-ance,” as for other terms forged by Derrida, here refers to a suspended status that undermines oppositions, namely the opposition between death and life. As survivors, we are indeed called to testify and bear witness to the ethico-political imperative of caring for the life-death of others, honouring their memory, and interpreting the traces that the dead leave behind (Derrida, Reference Derrida, Brault and Naas2001). Survivance becomes a “politics of memory, inheritance, and generations” (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]: xviii), urging us to undertake a process—the work—of mourning and remembrance.

Understood through the lens of survivance, mourning becomes a complex and ongoing process of being inhabited by the dead who “defy semantics as much as ontology” (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]: 5). Yet, the work of mourning consists of an inscription process that involves language and forms of representation that “write” our experience of mourning, which is culturally and socially mediated, and is always open and dynamic (Derrida, Reference Derrida, Brault and Naas2001). Thus, the imperative of the dead is both individual and ethico-political (Derrida, Reference Derrida1999).

For Derrida (Reference Derrida2006 [1993]), death teaches us not simply how to live but also how to live more justly. Ethics and justice are ultimately about being responsible towards others beyond the living present. As Derrida (Reference Derrida2006 [1993]) puts it, “no justice … seems possible or thinkable without the principle of some responsibility, beyond all living present, within that which disjoins the living present, before the ghosts of those who are not yet born or who are already dead” (xviii, emphasis added). Justice, for Derrida, is not about calculable or distributive justice, about restitution and punishment, or the law but about “the incalculability of the gift,” wherein the gift of death consists of giving to the other what properly belongs to them, giving them “presence” (Derrida, Reference Derrida1999). Hence, mourning takes the form of a social and cultural practice that emerges in the ways we organize our rituals and spaces of dying and death to “donate” or gift presence to the deceased.

Cemeteries, as discursive-socio-material assemblages of inscriptions and marks, materialize the work of mourning and offer a form of bearing witness in response to the ethico-political imperative of the deceased’s death. Through Derrida’s lens, cemeterial spaces appear as sites of inscription, commemoration, and meaning-making that materialize the work of mourning in its attempt “to ontologize remains, to make them present, in the first place by identifying the bodily remains and by localizing the dead” (Reference Derrida2006 [1993]: 9). Epitaphs allow the deceased to speak “beyond the grave,” break the silence, and return to us.

Resonating with Derrida’s ethico-politics of survivance, Butler’s theory of grievability begins with the ethical question, “What kind of world is this?” (Butler, Reference Butler2022). This inquiry invites us to scrutinize the ethical issue of how to recognize and honour the vulnerability and relationality we share with the deceased. In dialogue with Derrida’s concept of survivance, Butler argues that we must examine how we “account” for the deaths of others and the ways in which we produce (mis)recognition as we do so. In other words, for Butler, the “gift of death” has to do with its capacity to force us to recognize, reflexively, the differential distribution of value attributed to others.

In their essay “Grievability for the Living,” Butler (Reference Butler2022: 93 and 94) set out an ethical premise that connects to Derrida’s understanding of justice, namely that “it is not possible to understand social inequality without understanding how grievability is unequally distributed.” On this premise, Butler frames grievability as a loss that is “publicly marked and acknowledged” as opposed to one that is melancholic, whereby the latter “passes without a trace, with no, or little, acknowledgement” (Butler, Reference Butler2022: 89). To put it simply, to be grievable means “counting as a life … being a body that matters” (Butler, Reference Butler2022: 102). In contrast, living with an embodied sense of dispensability:

is the feeling that one could die and pass … leaving no mark and without acknowledgement. It is a lived conviction that one’s own life does not matter to others or, rather, that the world is organized … so that the lives of some will be safeguarded and the lives of others will not (Butler, Reference Butler2022: 92–93).

Thus, “to live as someone with a sense of being ungrievable is to understand that one belongs to that class of the dispensable and to feel abandonment as basic institutions of care either pass one by … or are withdrawn.” In these circumstances, “one is oneself the loss that cannot be mourned” (Butler, Reference Butler2022: 93). The melancholia induced is that of a circumstance, not simply, as Butler puts it, of foreclosed futurity “that goes along with having perpetually fallen through a safety network” in a sociological sense, but also of mis- or non-recognition in a more fundamental, ethical, and ontological respect.

Explored through the lenses of survivance and grievability, cemeterial spaces appear as crucial sites of recognition because they embody the materialization of recognition, or its absence, acting as (organizational) sites for the (ethical) work of mourning, or otherwise. They can produce “knowledge” that reinforces existing power relations, but they can also be transformative and offer radical possibilities through the traces they leave. Drawing on this idea, which combines Derrida’s ethico-politics of survivance and Butler’s recognition-based critique of the social relations of grievability, we investigate how the work of mourning materializes in two cemeterial spaces: San Michele cemetery in Venice and Hart Island, New York.

RESEARCHING RESTING PLACES FROM “ABOVE GROUND”

Our methodological approach was informed and inspired by Cutcher, Hardy, Riach, and Thomas’s (Reference Cutcher, Hardy, Riach and Thomas2020) invocation to think critically and reflexively about different ways of undertaking academic research that are more intersubjective and dialogical. Hence, we devised an approach that involved processes of collating, interrogating, sharing, discussing, reflecting, and reworking, each of us responding to our own and each other’s thoughts but also our emotional and affective responses to the two cases and the other materials we drew on (e.g., other writers’ accounts of death, dying, and dead bodies in organizational life, and of the two case study settings in particular). Our research began with the realization that we shared a fascination with burial places, both of us being taken (independently) with the landscaped beauty of San Michele and being moved by our quite different affective responses to Hart Island and what it seemingly represents.

As a result, the methodology we worked with was deliberately “holey,” with our approach being shaped largely by the generation of rhetorical questions that formed the basis of an ongoing, critical dialogue between us. Examples of the kinds of questions we asked include: What is this? How and why does this happen? Who was/is involved? In what ways is where this happened/happens relevant? How might this be different? What do we think about it, and how does it make us feel? How do our responses compare to those of others that are documented, and to which we have access? We repeatedly returned to, and adapted these questions, to guide our method of collating and analysing material on the two cases. Throughout each stage, we sought to be reflexive and mindful of the ways in which we were thinking and writing about life experiences and circumstances very different from our own. We took inspiration from Cutcher et al.’s (Reference Cutcher, Hardy, Riach and Thomas2020: 15) call for more reflexive research that strives to interweave “different discursive practices in ways that open conversations up to a wider range of voices, where respect and generosity are evident and where forms of knowledge emerge in dialogue.” On this basis, we worked to produce accounts of the two cases that would contribute to critical, reflexive dialogue on the ethics and politics of resting places, including by opening up space for what Cutcher et al. (Reference Cutcher, Hardy, Riach and Thomas2020: 15) call “productive moments of possibility” through which alternative ways of organizing might emerge.

Drawing on previous literature on organizational ethics and Butler’s and Derrida’s work, our analysis involved a comparative case study approach that drew together visual, textual, and video archival materials that are available in the public domain. The two cases were chosen because of their comparative and affective qualities. First, both are island cemeteries: separated physically from the communities they serve by water, they are both accessible only by boat. This physical separation reflects a combined ecological necessity: the logistical problem of what to do with an infinite volume of bodies in a relatively small amount of space, and a theological one—both cemeteries are situated in, and serve, societies in which the religious beliefs and cultural practices that predominate foreground the importance of keeping the body intact after death (in other words, they are largely burial cultures). In cities like Venice and New York, in which space is at a premium, this makes the problem of where to bury a large number of people an ongoing one. Second, the two cases were selected because we were struck by the aesthetic qualities of these different spaces. San Michele is a beautiful, tranquil space and Hart Island, by comparison, a heart-wrenching place of abandonment, where those whose lives had already been precarious came to embody, seemingly forever, their status as part of the world’s “dispensable population” (Butler, Reference Butler2022). We found ourselves wanting to know, think and talk more about these different spaces, and what we can learn about ethical life and death, and the social relations of recognition, by studying them.

Our “multifaceted magpie” method (Levitt, Reference Levitt2004)Footnote 6 involved collecting and collating the research materials we drew on by undertaking multiple digital searches using the names of the two islands, and by following up secondary links from these primary searches. This led us to working through academic and journalistic reports, court documents, minutes of meetings (e.g., council and committee meetings, limited to those available in the public domain), social media accounts, and interview data available via websites (e.g., the Hart Island Project—see below) as well as online materials to understand what we might broadly call the ethnographic landscape of the two cases. We did not do this systematically, but opportunistically, following links and connections that seemed interesting and relevant, and which helped us to respond to the rhetorical questions noted above, as these evolved during the research process and as we felt drawn to (and often, simultaneously troubled by) emerging discourses, narratives, and insights.

As Raudon (Reference Raudon2022: 5) has noted when discussing what researching places like Hart Island and other burial sites involves, “they are difficult to talk about, information about them is often hidden, discovery may be haphazard or serendipitous, they are challenging to visit and what they represent is confronting.” With this in mind, we made efforts to ensure, as far as possible, that a range of different perspectives and differently situated ways of knowing, thinking, and writing about the two islands were included in our research materials in order to take as much account as we could of “different communities of interest with contested responsibilities and concerns” (Raudon, Reference Raudon2022: 87). This helped us to make sure that, as much as we could, the perspectives of otherwise marginalized or neglected stakeholders were included (see also Derry, Reference Derry2012).

Combining a variety of resources in this way allowed us to access commentaries, reflections, and discourses that enabled us to understand more about the two cases, and to get a sense of how, over time, they are experienced and perceived in different and evolving ways by those connected to them (e.g., people connected to those interred there, visitors and other researchers, policymakers, practitioners, and politicians, and those who work there). This process, one that in practice wove together data collation and analysis, took approximately five months and enabled reflexive conversations to take place between us about the two cases, so that, following Jagannathan and Rai (Reference Jagannathan and Rai2022: 431), our research materials combine “personal reflections [our own and others’], stories, intuition, imagination, cultural and political beliefs.”

Working in this way enabled us to get a sense of what Jagannathan and Rai (Reference Jagannathan and Rai2022: 431) describe, with reference to their own methodology, as “an opportunity to unravel the temporal unfolding of human lives” and to understand how a phenomenon as fundamental as death is situated “at the intersection of the personal and political.” This approach also enabled us to bring together our own and others’ perspectives with wider social and political discourses (e.g., by reading personal stories multiple times in different reports such as newspaper articles). The data we draw on are not “representative” in any conventional sense; we selected some of the insights we draw from and the stories we refer to because they affected us in significant ways—for example, some of the stories on the Hart Island Project (HIP) webpage literally stopped us in our tracks in the way that Milroy, Cutcher, and Tyler (Reference Milroy, Cutcher and Tyler2019) describe, so that we could not “look away” (Courpasson, Reference Courpasson2016) but found ourselves needing to think, know, and talk more about them.

To do this, and inspired by Jagannathan and Rai’s (Reference Jagannathan and Rai2022) approach to their research, we analysed our data on the two cases by writing long notes for each other (approx. 10,000 words each) to help us to understand as much as we could about the two sites. These notes enabled us to discern the analytical frames that we used to make comparative sense of important similarities and differences, including in relation to the islands’ histories, geographies, and possible futures. The analytical frame we worked with drew from Linstead’s (Reference Linstead2018) categories or “moments” in the research process focusing on aesthetics, poetics, ethics, and politics.

For Linstead (Reference Linstead2018), the aesthetic moment occurs when we become forgetful of ourselves as we are fully immersed in our sensations and feelings, gaining sensory knowledge through our exposure to that which is most difficult to convey through language or text (Gagliardi, Reference Gagliardi, Clegg, Hardy and Nord1999). In our own analysis, we each became aware of a very affective sense of the places we found ourselves drawn to, being directly or indirectly moved by the two spaces and the combined sense of fear and fascination they engendered in us. Through poetic moments, as noted above, we found ourselves “held,” contemplating the materials we engaged with, particularly the most poignant images and film footage, and the deeply personal accounts we encountered (notably the HIP ticking clocks, discussed below). Our experiences resonated with the expressive language of videos and poems about the two places, and we were “arrested” by these resonances, finding ourselves deeply affected by them.

These aesthetic and poetic moments, in turn, stimulated a reflexive dialogue between us as we began to question how we found ourselves thinking about and relating to those buried on the two islands, reflecting on what their deaths and interments could tell us about the nature of the world we live in (Butler, Reference Butler2022). Derrida’s concept of survivance and Butler’s ideas around the mattering of bodies, and the ethics and politics of grievability and/as recognition appeared especially relevant to us at this stage wherein the last two of Linstead’s (Reference Linstead2018) “moments”—that is, the political and ethical—seemed to us at least, to conflate. Drawing from Butler’s and Derrida’s work, as well as the organizational ethics literature on relationality (Bell & Vachhani, Reference Bell and Vachhani2020; Fotaki et al., Reference Fotaki, Islam and Antoni2020; Pullen & Vachhani, Reference Pullen and Vachhani2020; Smolović Jones et al., Reference Smolović Jones, Winchester and Clarke2021), we came to draw from an understanding of ethics as situated within power relations and, therefore, as always also political.

In the sections below, we present accounts of the two islands, based on the research process described above. We make no attempt to generalize on the basis of these accounts, but aim to provide insight, based on these two case studies, into the different ways in which recognition and the attribution of value come to be organized in the handling of death, dead bodies, and in scope for grieving. As we sought to understand connections between different themes emerging in our writing, reading, and discussion of the notes we both made on the two cemeteries during the “moments” outlined above, we began to discern distinct themes that the data started to coalesce around, and which helped us to convey our informed understanding of how people experience these two burial sites. We turn to these themes in our discussion of what this comparative analysis foregrounded in response to the research questions outlined earlier.

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF TWO “RESTING PLACES”

Venice’s San Michele Cemetery

The Isola di San Michele (in English: Island of San Michele) is situated in the Venetian lagoon in North Italy. In 1804, when Venice was under French occupation, Napoleon Bonaparte chose the neighbouring island of San Cristoforo to host the city’s cemetery when it was decreed that burial on the mainland (or on the main Venetian islands) was unsanitary (Franceschi, Reference Franceschi1992). The cemetery was completed in the spring of 1813 and entrusted to the care of the Augustinian friars who inhabited San Cristoforo. However, in a short time, the space designated for burials was exhausted. In 1810, the Camaldolese monastery that stood on the nearby island of San Michele was suppressed and the island became the property of the state, which in turn sold it to the Municipality in order to join it to San Cristoforo. From 1835 to 1839, works were executed that involved filling in the canal between them, uniting the two islands into a single burial area (Franceschi, Reference Franceschi1992). Since then, the island became known as Venice’s “Island of the Dead.”

In 1858, a contest was held that was won by the architect Annibale Forcellini whose project design for enlarging the two islands was chosen. A cemetery was planned with a typology that responds to the classical Mediterranean type, that is, as a Monumental Cemetery, conceived as a miniature city that imitated, to a certain extent, the development patterns of the city of the living. In 1998, another international competition for the expansion of the San Michele cemetery was announced. The winning design was that of the architecture studio of David Chipperfield, with the first phase finishing in 2008.

Today, San Michele cemetery is a highly stylized place, consisting of carefully landscaped gardens and monuments consisting largely of commissioned artworks (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A Detail of a Commissioned Artwork in San Michele

Note. Photo by Luigi Maria Sicca.

A high wall goes around the cemetery island, whose area is, in total, about 18 hectares. The cemetery has a simple structure, with a Greek cross plan, a perimeter of solid red bricks, in turn circumscribed by Istrian stone. Chipperfield (Reference Chipperfield2022) explains how the cemetery space has been designed to convey “a sense of intimacy and enclosure” and how this is obtained through a careful design of boundaries and courtyards.

Also, materials such as marble and stones materialize a feeling of long-lasting harmony. Texts from the Gospels offer guidance to visitors signalling the sacred nature of the place. In combination, the design, aesthetics, materials, and markers that make up the island of San Michele give a feeling of tranquillity, harmony, continuity, and connection. Everything is designed to seek balance and symmetry (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A Portico in San Michele

Note. Photo by Luigi Maria Sicca.

As Semerani (Reference Semerani and Ferrari2004: 11, cited in Monestiroli, Reference Monestiroli2021) notes, the island’s aesthetic qualities derive largely from its uniformity, “from having … the right measure, the right number of courses of bricks or stones, the right size of the marble slabs, and therefore the right kiln or the right quarry, the right firing or the right vein, the exact profile of the beam, the best projection to use the shadow as a residual mobile moulding.”

Each redesign of San Michele has aimed at crafting a sense of perfection, balance, and beauty. The latter is reflected in the many accounts of the people who have visited the cemetery, which in turn resonates with our own recollections and experiences of the place. The selection of the materials, the shapes of the enclosures, the latter’s relation to the water that surrounds it, all evoke a calming experience of this peaceful and beautiful setting, associating it with tranquillity and artistry. The use of long-lasting, natural materials and design motifs resonant with a classic era combine to produce a feeling of longevity and connection, solidity and significance (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A Pathway in San Michele

Note. Photo by Luigi Maria Sicca.

As Linstead (Reference Linstead2018) notes, encounters with beauty often take our breath away. While San Michele appears solemn and majestic on the horizon as it is approached from the water, or as it is seen from Venice itself, the island’s artistic beauty is striking in a way that is somehow “beyond language” (Gagliardi, Reference Gagliardi, Clegg, Hardy and Nord1999). It would be easy to approach or go past the island by boat and not realize it was a cemetery, but to assume it is a beautifully landscaped and well-maintained park, palatial private residence, or hotel complex. Unsurprisingly, over the centuries, fascination with the island has mostly been articulated through literary works and poetic language as not only San Michele, but also the city of Venice became associated with death—for example, through Thomas Mann’s masterpiece Death in Venice. The city’s association with death arguably emerged but continued well beyond the Romantic period, and San Michele Island became a desirable and popular “resting place” among poets and artists (Perocco, Reference Perocco, Brusegan, Eleuteri and Fiaccadori2012).

In addition to stimulating us aesthetically and poetically (Linstead, Reference Linstead2018), the San Michele cemetery also interrogates us ethically. Wandering in the cemeterial space is an opportunity for encountering the many people who are buried there. Visitors are able to access the island by boat and are invited to read names and biographical details of those buried there. In contrast to Hart Island (see below) there are detailed accounts of people’s identities and lives; the organization in charge of San Michele cemetery keeps an account of the famous people who are interred there (see Table 1), with a detailed visitors’ map indicating where to find their graves.

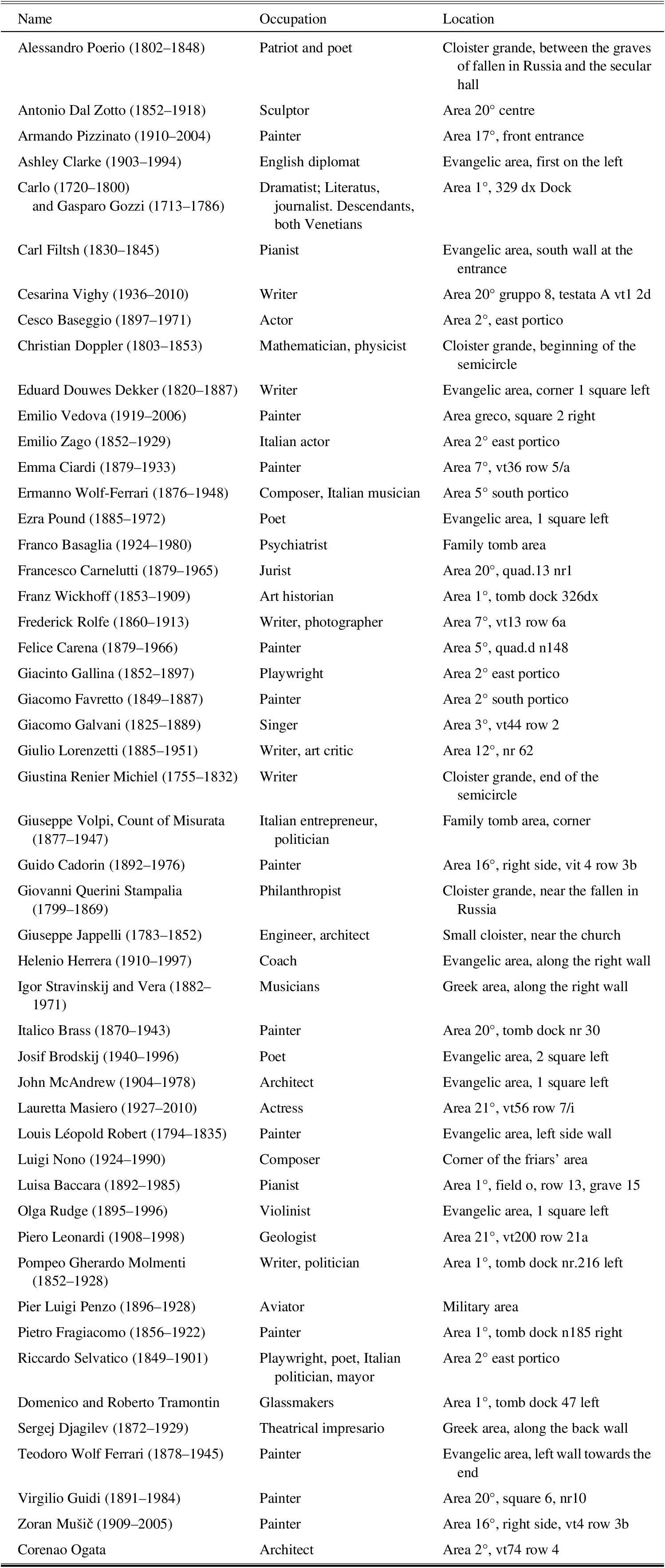

Table 1: List of Illustrious Deceased Buried in the San Michele’s Cemetery

Note. Source: Venice municipality website.

These forms of “inscriptions” testify to the importance of preserving the memories of these lives, signifying their ongoing value beyond death (Derrida, Reference Derrida, Brault and Naas2001), materializing recognition in the accounts and artefacts that signify value through the act of producing memories and assembling (designing, maintaining etc.) San Michele as a meaningful place. And this has been the case throughout its history—records of epitaphs and tombstones date as far back as 1663 (Perocco, Reference Perocco, Brusegan, Eleuteri and Fiaccadori2012). Keeping and updating these inscriptions over time is a practice that involves, and testifies to, distinguishing lives that “matter” from those that don’t. Those interred on San Michele do not appear as an anonymous list of names. Significantly, the tombstones are marked with Roman numerals before being assigned to someone. In the moment in which someone then inhabits their allotted space, these numerals are “translated” into the names and life stories that make up San Michele’s burial records. Furthermore, these accounts are shared with the public, and with visitors to the Island, so that they become part of its collective memory.

In this respect, the San Michele cemetery is an example of how the “Western culture … established … the cult of the dead” (Foucault, Reference Foucault and Faubion1998 [1967]: 5). This cult emerged in conjunction with a change in the management of dead bodies, including the organization of cemeteries, as noted earlier. The Church was no longer the only institution in charge of organizing death. The cemetery, like the school and the post office, became a sign of the presence of the State and a space for making explicit and affirming its civic ethos. Reflecting this, San Michele cemetery is a burial ground for people who have distinguished themselves, predominantly in the artistic field. Poets, musicians, architects, psychiatrists, and philanthropists are given recognition with monuments of artistic and historical significance. Both the public/political and private life of these personalities find recognition in the cemetery where they are buried with their loved ones, as it is the case for Stravinsky, who is buried next to his wife, the artist Vera de Bosset. Overall, there exists a certain normativity in the organization of this space as graves are also there to signal “role models” and “lives” that are revered as worthy of aspiration and imitation. These deaths are there to inspire us, to teach us a way of life, acting as individual as well as ethical markers.

In this sense, the “famous” individuals buried in San Michele are like “spectres” haunting us with their example and request for “survivance” (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]). Those interred there seem to inhabit a liminal space, as they do not belong to the world of the living (since their physical body is dead) but neither do they belong to the world of the dead (since their life as an example, their endeavour, survives the death of the physical bodies). These graves appear more as a contemporary version of the apotheosis of Roman emperors, a wax imago that is worshipped as if these bodies can never actually die (Agamben, Reference Agamben1998). There is an “excess” inherent in these sacred lives, the corpus morale et politicum, that survives the death of the physical body and is passed to others, to be revered and shared. The tombstones in San Michele are thus highly individualized and serve as a reminder of our role as witnesses and survivors. By acknowledging the uniqueness of each person and their passing, we are able to differentiate and bear witness to each death in its own way. However, this individualized recognition is accorded only to those who were privileged, revered, and/or well-known enough to be buried there, and who are, as a result, memorialized accordingly.

As a publicly managed cemetery, San Michele abides by regulations requiring citizens to be buried in their nearest cemetery. Consequently, the administration must allocate burial capacity for Venetian citizens. However, San Michele often receives numerous requests for burial exceptions from “famous” individuals who are not Venetian citizens but who wish to be buried in Venice. These requests are carefully evaluated by both the mortuary police and the municipality, with decisions made to either approve or reject them. Given the cemetery’s status as a tourist attraction, the municipality frequently opts to approve these exceptional requests, recognizing their potential benefits. Simultaneously, this poses further challenges regarding the maintenance and preservation of the artistic and monumental essence of the site, as well as the meticulous management of burial capacity. Essentially, the administration must navigate a delicate balance between its obligations to ordinary citizens and the preservation of San Michele’s allure as a tourist destination. In this respect, it is important to notice that whereas the “famous” dead can rest undisturbed in perpetuity in their graves, recently more and more other “common” bodies are instead subject to exhumation after a fixed period of time, a practice introduced in San Michele in the 1950s to deal with the scarcity of burial space. Exhumation, typically aimed at relocating or cremating the deceased, underscores a significant evolution in legal norms regarding the treatment of the dead. Moving from perpetual burial to shorter intervals (exhumation in San Michele occurs after 10, 15, or 99 years, depending on the location), this shift signals an emerging necroeconomics (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2008; Skeggs, Reference Skeggs2021), as a paradigm shift prioritizing organizational practices that pragmatically address economic needs, such as efficient burial space management and revenue generation from concession sales.

The cultivation of memory, including that of revered individuals, requires social rituals and ceremonies that convey recognition. Recognition is part of how dead bodies are organized on San Michele, practised through how encounters with those interred there are organized. The “cult” status of those buried there involves public and communal worshiping, and the accessibility of the place and the visitors’ guide noted above reflect this. On the island itself, signs help visitors navigate the space and find the sections of the Island they wish to visit. San Michele is a tourist destination and, as such, it is highly accessible and pleasant to visit. Historically, once a year, during the week of the Commemoration of the Dead, the Island had become accessible through a bridge of boats connecting the Fondamenta Nove with San Michele Island. Beginning in 1950, this tradition allows visitors to arrive directly at the monumental portal that once served as the main entrance to the cemetery. The bridge connecting Fondamenta Nove with the island of San Michele during the week of the Commemoration of the Dead, as well as the numerous boats that transport visitors to the cemetery daily, materialize the return of the dead in our lives in a way that “repeats itself, again and again” (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]). Through these materializations, we are reminded of the importance of repeatedly recognizing and commemorating loss, and of the ongoing presence of the dead—or rather, those whose deaths and hence lives are recognized as being of value.

In sum, San Michele is an artistically and historically significant burial setting. Architect designed, carefully landscaped, and meticulously maintained, it is not only accessible to the public, but is a coveted tourist destination. Visitors are encouraged and welcomed there. It reflects the modern conviction that mortal remains have an ethical significance beyond death, and individual burial plots and grave markers signify this. Not only do carefully kept burial records and visitors’ guides indicate the recognition and reverence accorded to those buried there, the detailed life histories which are shared with members of the public contribute to collective memory-making, and to the constitution of San Michele as a meaningful location where those who “matter” are buried.

New York’s Hart Island

In contrast to the artistic integrity, idyllic setting, and manicured tranquillity of Venice’s San Michele cemetery, Hart Island is a desolate, isolated place. Situated just off the east coast of Manhattan in the Bronx Sound, Hart Island is reportedly the largest publicly funded cemetery in the world (Raudon, Reference Raudon2022), yet it is practically invisible.

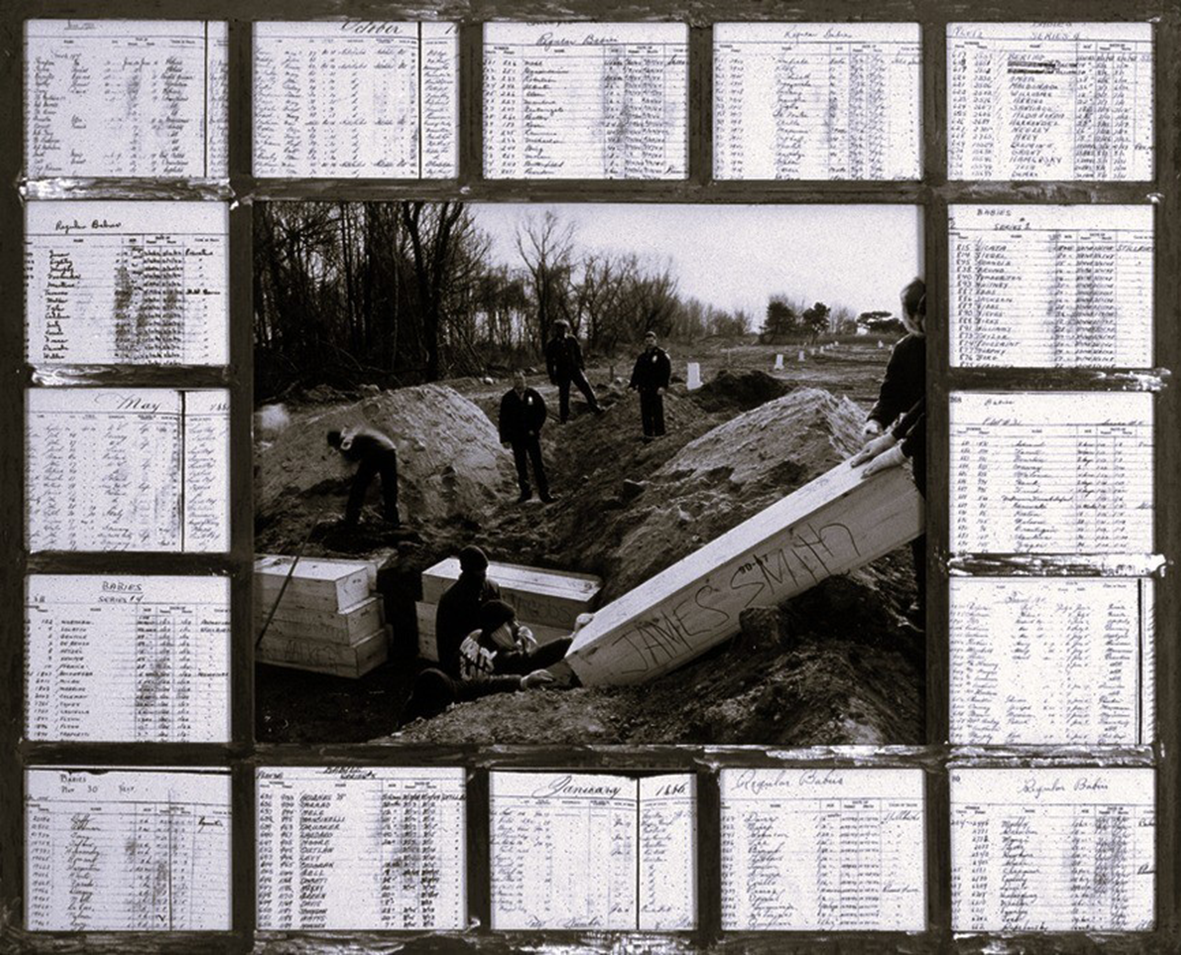

Hidden in plain sight, Hart Island does not feature on public transport maps, or architectural representations of the city of New York and is largely inaccessible to all but those who work there. That access is “severely limited and strictly regulated” exacerbates the Island’s long-established reputation “of separation and otherness” (Byers, Reference Byers2022: 9).Footnote 7 As Rees (Reference Rees2020: 8) puts it, its location is part of what makes Hart Island “such a tragic place”; it is “literally and metaphorically disconnected from humanity.” Described as the City’s “dark shadow,” it is the final resting place of approximately one million of New York’s “unwanted, … lonely, … forgotten and … marginalised” (Byers, Reference Byers2022: 1); it is a cemetery “for the nameless and the homeless’ (Bowring, Reference Bowring2011: 251). Until 2020, its massed, anonymous graves were dug and filled by prisoners from nearby Rikers Island, in a workforce scenario that bordered on DickensianFootnote 8 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Prison Inmates Digging Graves on Hart Island, and Examples of Burial Records

Note. Photo by Melinda Hunt (The Hart Island Project).

Raudon (Reference Raudon2022: 84) notes that the dead are largely interred on Hart Island in deep plots, each holding approximately 150 adults or 1,000 babies. While the island is commonly referred to as a mass grave, this term is misleading, as it suggests a pit in which bodies are piled. Rather, the Island is better understood as consisting of a series of massed graves, where the dead are communally, if predominantly anonymously, interred in individual coffins. Accounts (e.g., of precise locations) are often vague or contradictory, but official records suggest that details of burials are kept so that graves can be identified, and bodies can be disinterred when necessary. In short, Hart Island is a mass burial site that is widely regarded by those who know of it as a poignant, barren “hellscape” (Byers, Reference Byers2022: 6). Aesthetically and poetically, it would be hard to imagine a burial site more different from San Michele.

Believed to be the world’s largest potter’s fieldFootnote 9 Hart Island has, for over 150 years, been a mass burial ground, largely for New York City’s indigent and unclaimed dead. From its earliest use in the 1860s, it was an extension of the places where the city’s most marginalized residents were contained or cast out.Footnote 10 These were spaces where the outsiders the City sought to expel but could not entirely rid itself of, were sent to be unseen, and unheard, condemned to reside in an “elsewhere” (Kristeva, Reference Kristeva1982: 5), of which Hart Island is a notable example. Reflecting this history over a century later, Hart Island was widely used during the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and again, during the COVID pandemic in the early 2020s.Footnote 11 It was only during the latter that media coverage of Hart Island began to shine a critical spotlight on the island’s history. As Raudon (Reference Raudon2022: 84) notes in her account of this:

When drone footage emerged of New York City’s COVID-19 casualties being buried by inmates in trenches on Hart Island, the images became a key symbol for the pandemic: the suddenly soaring death toll, authorities’ struggle to deal with overwhelming mortality and widespread fear of anonymous, isolated death.

Records indicate that approximately a million people are buried there, predominantly those who, largely because of race, immigration status, poverty, and disease, have been buried in obscurity, with many ending up, because of the circumstances of their life and/or death, being condemned “to oblivion’s relegation” (Brouwer & Morris, Reference Brouwer and Morris2021: 160) in almost entirely “unmarked and unmemorialized” (Raudon, Reference Raudon2022: 84) massed graves.Footnote 12 In the words of a New York City council worker: “the city has always wanted to forget about Hart Island. The city has wanted to forget about the people who are buried there. It’s wanted to forget about the fact that there is a potter’s field, that there is a place where difficult stories are hidden” (Brouwer & Morris, Reference Brouwer and Morris2021: 164).

For Keene (Reference Keene2019: 65), the common denominator for all who are interred on Hart Island is “mass anonymity, total detachment, and a dark loneliness.”Footnote 13 The stigma that surrounds burial sites like Hart Island reflects more than anonymity and marginalization, however. Potter’s fields are places that materialize both changing attitudes to death and enduring moral judgements about those who come to be buried there and in places like it. For Byers, the “trauma tourism” that Hart Island has attracted since the COVID pandemic is simply a contemporary manifestation of this, with the moral outrage engendered by growing awareness of the indignities suffered by many of those interred and required to work there, simply inverting the indifference or fear engendered by burials during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. The relative anonymity of a burial on Hart Island has particular poignancy given “the normative Anglo-American expectation of an individual named grave” (Raudon, Reference Raudon2022: 91), as discussed above, one that “makes the unknown dead a moral rebuke,” and which contrasts markedly with the reverence and meticulous process of memorializing those who are interred on San Michele, Venice. As Raudon (Reference Raudon2022: 91) puts it:

Massed graves challenge … [the] normalisation of individualised human remains, and effectively mute social connections. To be buried promiscuously, in the sense of indiscriminately mixed, is a lonely burial, separated from family, faith community or other groups. Because Hart Island is difficult to visit, rituals celebrating the continuing bonds between the living and the dead are not easily performed publicly or privately. The lack of headstones and names means there is no legible public display of these social links.

Founded in 1994 by activist and artist, Melinda Hunt, the Hart Island Project (HIP) has worked to destigmatize the island and to find the names and locate the burial places of those known or believed to be interred there. The HIP’s work both highlights the racialized and class-based politics of misrecognition that Hart Island represents and draws critical attention to the “memory impoverishment” (Brouwer & Morris, Reference Brouwer and Morris2021: 161) that places like it materialize. The HIP has focused on how, especially during the 1980s AIDS epidemic, “a collective ‘recoil’ characterized administrative logics and labour practices” (Brouwer & Morris, Reference Brouwer and Morris2021: 166) governing how the bodies of those who had died were treated. Buried in lead coffins in quarantined plots, those known to have died from AIDS-related causes suffered “a double indignity”—“to die from such a stigmatized disease and then be buried in anonymity” as Elsie Soto, one of the featured storytellers in the HIP AIDS Initiative web series describes it. And to this double negation, we might add a third, namely that the enduring public perception that a Hart Island burial “inevitably means a deeply shameful and degrading end to an unfulfilled, unhappy life” arguably limits the ways in which Hart Island’s possible futures might be reimagined (Byers, Reference Byers2022: 2). For those who are aware of its history, Hart Island will most likely, always be a place populated by those who have suffered the multiple indignities of “disposals of last resort” (Raudon, Reference Raudon2022: 84).

For nearly three decades, the HIP has challenged Hart Island’s memory constraints—awareness, accessibility, prejudice, and carceral stewardship. Through legal intervention and public memory work that includes the collation of stories, photographs, art works, music, and film footage, the HIP has pursued commemorative transformation through archival facilitation, by making public records and institutional history more transparent, and by generating remembrance through its Traveling Cloud Museum, documentary films, and web series. As Brouwer and Morris (Reference Brouwer and Morris2021: 164) sum it up:

A key motive of the Hart Island Project is to destigmatize the site, transforming it into a reachable and respectable public cemetery and national monument, via the breakthroughs of rhetorical claimings and tellings. The vision is liberatory but the labour daunting, owing to the deep discursive sedimentation constituting the ignoble status of Hart Island’s dead and the forbidding nature of the destination.

HIP’s work to find, name, and curate the life stories of people buried there is designed, in part, to provide points of identification and reconnection, to commemorate, and to problematize the whitewashing of AIDS remembering, in order to interrogate who counts as a grievable subject, and to critically question the politics and practices of remembering in and through spaces such as Hart Island. As Raudon (Reference Raudon2022: 85) puts it, “in most societies, mass graves indicate a bad death, because individual burial crucially affirms personhood by signalling who is ‘grieveable’: some lives are recognised as worth celebrating, while others are deemed less than human and disposed of anonymously … These burials materially illustrate a nexus between inequality and symbolic violence.” It is worth noting in this respect that until public condemnation put an end to the policy in 2015, bodies due for burial on Hart Island were automatically made available for unconsented dissection (Keene, Reference Keene2019). As Raudon (Reference Raudon2022: 92) puts it, this practice was significant as it was not only an ethical violation but it “clearly signalled the deceased’s value to the City, classifying them as a physical resource rather than a person.”

In November 2018, HIP released an activist documentary, Loneliness in a Beautiful Place, and uploaded it to the Project’s AIDS Initiative website. As noted above, the film features aerial footage that aims to render Hart Island more accessible, and subject to scrutiny. Recognizing growing critique of the uses of drone technology for state and corporate surveillance and violence, Brouwer and Morris (Reference Brouwer and Morris2021: 167–68) view the film as illustrative of how drone technology’s oppositional uses for activists and social movements can help in the assertion of counterhegemonic rhetorical possibilities, highlighting how, under what were (at the time) conditions of restricted access to the island, the film performed a kind of “queer reconnaissance … a rare way of getting there that facilitated the ability for wider publics to see and experience the AIDS dead.” Providing unrestricted aerial “access” to the island for the first time and illustrating its proximity to mainland Manhattan with a commentary that highlights its history and topography, the film implicitly poses the question of why somewhere so close could be so out of reach and in doing so, “performs a critique of limited access.” In this sense, as part of the wider activist project, the film shows how “the variegated ‘unclaimed’ AIDS dead on Hart Island struggle to achieve standing as grieveable subjects on a national scale, [arguing] … for a reconsideration of the indigent or ‘unclaimed,’ including the abundance of those with Latinx surnames, as grieveable national AIDS subjects” (Brouwer & Morris, Reference Brouwer and Morris2021: 169). In doing so, the film and the wider project undertake the work necessary to both highlight the negation of those deemed unworthy of recognition at the time of their burial, and to begin the process of recognizing and remembering them. Arguably, this is a process necessary to the realization of cemeteries like Hart Island as part of ethical life and death.

As another of HIP’s activist practices, the AIDS Burials on the Hart Island Web series features storytelling interviews, ranging between ten and nineteen minutes in length. Launched in April 2020, the series introduces us to friends and family of the deceased, interspersing home encounters with family artefacts, street scenes, HIP video footage, and photographs. Across these interviews, the contributors share different perspectives on what it means to be buried there, and to visit Hart Island as a grieving friend or relative. Referring to Hart Island as “beautiful,” “calming,” and even as “relaxing,” some of the short films support HIP’s project to destigmatize the island and to reimagine what it means to be associated with it; others, however, refer to family members’ desire to exhume bodies and have them reinterred in marked graves (e.g., in their home towns), although the cost-prohibitive nature of this is also noted.

As noted earlier, a third element of the HIP project is that of the “ticking clock” that features on its Travelling Cloud Museum (TCM) webpage.Footnote 14 This feature counts the time difference between the date of a person’s burial on Hart Island, as recorded in the New York City official record, and the precise time when a living person confirms that they are known, recognized, and “claimed.”

Most of the clocks are still ticking in real time, attesting to the number of people who no-one has “claimed.” Brouwer and Morris (Reference Brouwer and Morris2021: 172–73) note how, as one element of the TCM, the ticking clocks function as an “affect generator,” heightening a sense of urgency to recognize and reconnect. Crucially, (from our own experience) encountering not just one but so many ticking clocks on the TCM produces a strong affective response marked by the “quiet, haunting persistence” of each unclaimed person, highlighting the dynamics of vulnerability and recognition that constitute cemeteries as sites on which a recognition-based “ethics of claiming” (Brouwer & Morris, Reference Brouwer and Morris2021: 174) is played out. At those “moments” in the research when we encountered these clocks, we felt the aesthetics and poetics, and politics, of San Michele and Hart Island particularly acutely.

The HIP aims to bring dignity and accessibility to those interred there, to help relatives and kin connected to people known or believed to be buried there to access their records and resting places, and to tell their stories, as well as to rehabilitate Hart Island as an affordable, sustainable alternative to cremation. At the time of writing, the HIP is also working towards designating the island as a National Monument to recognize those who are buried there. Through its COVID-19 Initiative, the HIP aims to support people in locating gravesites of people who died during the pandemic and who were given a city burial on Hart Island. This project evolved from the longer-standing AIDS Initiative discussed above, and underpins the HIP’s aim, through identification, connection, and storytelling, to make Hart Island an inclusive, accessible rather than shameful, isolated resting place, and in doing so, “to enlarge the meaning of this landscape” (hartisland.net). In October 2022, the Hart Island Touchstone Coalition (HITC) organized the first in a planned series of bereavement walks to honour the memory of those interred on Hart Island as a result of pandemic illnesses, including AIDS and COVID.

Some of the most pressing yet seemingly insurmountable issues facing Hart Island at the time of writing include the need for a new infrastructure to make the site safe, workable flood barriers and mechanisms to deal with the problem of shore erosion, and better transport links for public access. Byers notes how inadequately interred bodies sometimes wash up on neighbouring shores after floods there. For Rees (Reference Rees2020: 9), memorialization is crucial to combatting the “double death” of those interred on Hart Island and places like it, and the work of the Hart Island Project discussed above is clearly vital in this respect, doing the ethical work of reinstating those interred there as grievable lives and therefore beginning to undo “some of the social death that made it possible for human life to be discarded in a mass grave in the first place” (Rees, Reference Rees2020: 13, see also Guenther, Reference Guenther2013). Serving to reconnect those interred there with wider society and social networks and, thus, resuscitate them socially is ongoing work, but as it stands, the majority of those interred on Hart Island remain “unreachable, unknown, unclaimed and [in many cases] unidentified” (Rees, Reference Rees2020: 14).

DISCUSSION: GRIEVABILITY AND SURVIVANCE AS GRAVE MATTERS

Cemeteries, and the rites and rituals they involve, are places that, often in highly organized ways, guide us through some of the ethical imperatives that death and the dead present us with (Francis, Reference Francis2003; Francis et al., Reference Francis, Kellaher and Neophytou2005). Our aim has been to explore what we can learn about organizational ethics from a comparison of two distinct cemeteries, San Michele in Venice and Hart Island.

We propose that an ethics of grievability (e.g., of mourning and, by implication, living) can only emerge from mutual recognition of our most basic inter-connectedness. Growing interest in organization studies (Antoni et al., Reference Antoni, Reinecke and Fotaki2020; Fotaki et al., Reference Fotaki, Islam and Antoni2020; Mandalaki & Pérezts, Reference Mandalaki and Pérezts2023; Painter-Morland, Reference Painter-Morland2007; Shymko et al., Reference Shymko, Quental and Navarro Mena2022) and business ethics literature (Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann2022; Loacker & Muhr, Reference Loacker and Muhr2009) in a relational, ethico-politics of recognition provides a vital theoretical framework for understanding grievability as a “gift of recognition,” and to develop what this means, we have turned to insights from Butler and Derrida. Drawing on ideas derived from their writing on death, grievability and mourning in our accounts of the two cemeteries, we have reflected on how cemeteries can provide a space for organizing the “work of mourning” and for offering—or reclaiming—recognition. The notion of gifting recognition involves bearing witness to the traces left by the dead, as it is through recognizing the dead that we learn how to live justly (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]). On this basis, we have suggested that spaces of negation, such as Hart Island, are unjust, not simply because of how the dead are treated there but in terms of what this means for the living, with our most basic relational connectivity being severed. Understood as situated within capitalist and colonial relations perpetuating class, gender, sexual, and racial injustices, we can see how this severance causes a necropolitical, forceable separation (Mbembe, Reference Mbembe2019).

Using these theoretical and conceptual lenses to reflect on the two cases, we have proposed that cemeteries provide a material representation of the extent to which we value the other (Butler, Reference Butler1993, Reference Butler2004), determining who is memorialized and who is negated (see Francis, Reference Francis2003). In our comparative analysis of Hart Island and San Michele, we have highlighted how both settings materialize how ethical relations come to be organized in ways that perpetuate inequalities around who counts as fully human, worthy of recognition and remembrance, in life and in death, and the corresponding organizational problem of how to inter dead bodies in ways that are ethically defensible.

Aligned with Rees (Reference Rees2020: 13), our analysis foregrounds three essential components necessary for the “work of mourning” and the responsibility of inheriting (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]; Reference Derrida, Brault and Naas2001): accessibility, inscriptions (i.e., naming), and commemoration rituals that respond to the research questions we posed earlier. Firstly, access is an important ethical issue, as without it, not only do the bereaved suffer from being unable to attend burials, they are, as Raudon (Reference Raudon2022: 87) describes it, “prohibited from memorialising, performing rituals or visiting the grave as they wish and carrying the affective burden of [providing] for their deceased.” Thus, different forms of accessibility can have ethical implications for the ability to mourn and recognize the dead, and accessibility is very differently organized in the two cemeteries we consider here.

Second, gifting recognition involves producing “knowledge” by ontologizing remains through inscriptions (naming being one of these), that is, traces of traces (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]). Ethically speaking, unnamed and unmarked mass graves produce an “inauthentic” relation to death by evading its ethical imperative. The absence of inscriptions erases the traces left behind by the dead and fosters a collective forgetfulness that disavows our fundamental relationality. As a place devoid of recognition, Hart Island negates our most basic relationality in ways that contrast markedly with a place like Venice’s San Michele cemetery, which arguably does something similar but in reverse, that is, by hyper-individualizing recognition of those buried there, “fixing” their existence in their achievements and social standing, and in doing so, also reifying social relations. In this sense, San Michele can be understood as a place of reified, highly individualized recognition and Hart Island as a site of negation, both materializing how our desire for recognition in life—and in death—comes to be organized in ways that reify or disavow relationality as the ethical basis of social relations.

Third, the gift of recognition also involves performing rituals of commemoration, which challenges our linear understanding of time and deconstructs the binary of life and death. Mourning involves repetition, as the dead are always a revenant, constantly returning (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]). Thus, the ontologization of remains through cemeterial space serves the purpose of creating a time and space for collectively recognizing and commemorating loss, as well as keeping memories alive in the long term. In this sense, the Hart Island Project is ethically significant, especially its “ticking clock” that materializes the urgency of repetition as a “haunting” of both memory and translation (Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993]). The ticking of the clock serves as a reminder of time for commemoration that has been “lost,” serving as a tangible reminder of the need to (re)connect. Again, while San Michele arguably reifies this relationship, Hart Island negates it, precluding rites and rituals that accord recognition.

Derrida’s (Reference Derrida2006 [1993], 1999) concept of “survivance” emphasizes that mourning is not something that happens only when someone else dies; rather, it is something that is always present as we leave traces throughout our lives. This notion is consistent with Butler’s (Reference Butler2022) argument that the lives of some are more grievable than others. Building on their earlier work (Butler, Reference Butler2009) and writing with reference to the pandemic, Butler (Reference Butler2022: 86) refers to the notion of a “metric of grievability” that marks out “whose life, if lost, would count as a loss, enter into the registers of loss, even broach the status of an incalculable loss. And whose death can be quietly calculated without ever being named as such.” In such instances, they argue, “social inequality works together with necropolitical violence” (Butler, Reference Butler2022: 89) to value some lives, not just as opposed to, but arguably at the expense of others (see also Islam, Reference Islam2022).

In stark contrast to those interred on San Michele, even relatively temporarily, those buried on Hart Island have never been mourned; their traces have never been kept and inherited, they are “unknown.” These individuals have experienced ungrievable deaths and have repeatedly died unnoticed. The idea that the work of mourning is an ongoing process (Derrida, Reference Derrida, Brault and Naas2001), rather than a reaction to a specific event, highlights the importance of recognizing and honouring those who are “lost” in this way.

Overall, through our analysis, we have revealed the variegated landscape of recognition that materializes in the two cemeterial spaces we have considered. There are differences between and within the two places in terms of signifying something/one of importance, and in terms of the socio-material forms they take. Not least, these are two places where bodies, living and dead, are treated very differently, and—we have suggested—these differences can be understood with reference to the ethics and politics of survivance and grievability (Butler, Reference Butler2022; Derrida, Reference Derrida2006 [1993], Reference Derrida1999). The two cemeterial spaces indeed provide poignant illustrations of the differential attribution of grievability as an organizational, or organizing, process of gifting recognition.

Understanding relationality as the premise of an ethical life and death requires us to commit to a critical, reflexive, and hopeful reconsideration of how we might create and reimagine alternative conditions of possibility for recognition-based, relational modes of organizing that affirm, and enact, affective bonds of solidarity (Vachhani & Pullen, Reference Vachhani and Pullen2019) in life and in death. And this ethical premise allows us to open up organizational processes and practices “beyond death” to further critical scrutiny, and to engage with the ethical possibilities that doing so might lead to. With reference to our discussion of the two cemeteries we have considered here, we would suggest that this kind of ethico-political critique could lead to understanding—and organizing—the handling and interring of dead bodies in more socially, environmentally, and ethically responsible ways in the future. Thus, we drew from recent recognition-based accounts of the conditions governing a liveable, and by implication grievable life, in order to examine how an ethics of relationality might be materialized in the context of resting places in the future, in ways that recognize our mutual vulnerability and inter-connection and organize death and dead bodies accordingly.