Introduction

Over the last 20 years, Composer-Performer Collaboration (CPC) has become a distinct research field,Footnote 1 but in spite of the volume of published work, it remains an emergent field, since we are still working with a small and arguably skewed dataset. Most of the published CPC scholarship draws on one-off projects, documented, at least in part, for the purpose of providing source material for academic publication, or on groups of projects pursued for postgraduate research, mostly over three to four years.Footnote 2 My experience, however, is that discovery often occurs when it is least anticipated and that fruitful collaborative relationships can extend over decades. Performers doing doctoral research into the making of new work have been the most assiduous group developing the new field, although a significant proportion of this research focuses on CPC not as a primary subject but as a method for revealing other aspects of the making of new music. In a themed session and round table presented by the RMA Composer-Performer Collaboration Study Group at the Royal Musical Association’s 60th Annual Conference in London on 11 September 2024, the relative dearth of CPC documentation from the past was lamented.

The personal and ethical dimensions of documenting and sharing working processes are potentially fraught but are not, I feel, the central challenge of the field. Projects set up explicitly for the purpose of documentation may offer useful control cases, although this targeted approach seems an inefficient way to generate or identify material that might be useful for others. Perhaps the field’s central challenge lies in balancing the essential requirement of documentation with the need to establish thresholds for significance. This article focuses on a personal letter from Justin Connolly that explores in great detail issues arising from a newly completed, shortly-to-be-premiered piece, Collana, on which we had been working together. Its significance stems from the quality and detail of the content and the light it sheds on the thinking of a significant composer.

The letter predates the emergence of CPC; it exists because Connolly thought it would be useful to our work and our relationship. This is also significant. In 1962 Martin Orne set out the notion of ‘demand characteristics’:Footnote 3 ‘the totality of cues and mutual role expectations that inhere in a social context (e.g. a psychological experiment or therapy situation), which serve to influence the behavior and/or self-reported experiences of the research participant or patient’.Footnote 4 In principle, the idea that demand characteristics have shaped the CPC literature is no cause for concern, but it is useful to interrogate work undertaken under different conditions and expectations; for example, work from the twentieth century and earlier that resembles some of today’s artistic research can offer valuable models.

One tendency within the CPC literature is worth identifying. Because documenting collaboration is now often academically beneficial for the participants, the working process may be treated with undue significance, and the most ‘valuable’ elements promoted, at the expense of more complicated or less desirable ones. There is often an implicit value judgement that shared work is more interesting, better or more complete than work in isolation. The study of process for its own sake is a viable academic discipline, but for the wider community it is the relationship to and significance of the artistic work itself that is centrally important. In short, the danger is that a research ‘subset’ of the potential musical audience shapes understanding of collaborative processes according to essentially unmusical demand characteristics. A ‘time capsule’ can help raise awareness of the issues, and this seems a good moment to open it: Collana is in print for the first time, and a recording has just been released.

Context for the Letter

Collana (the Italian for necklace) is a 10-minute solo cello piece that Justin Connolly wrote for me in 1995.Footnote 5 We were colleagues at the Royal Academy of Music, where I had recently started teaching, and the piece was a response to a concert I had given earlier that year to which Connolly had reacted very enthusiastically. The piece emerged on A4 sheets of paper in small sections, which he described as ‘beads’ and ‘strings’. We workshopped these over several weeks at the Academy around our teaching schedules. Those A4 manuscript pages are now lost – embarrassingly – and none of the workshopping was captured; today, I would automatically expect to keep the drafts and capture the workshops. That I lost the manuscript pages in the 1990s reveals how natural it was then to focus on outcomes rather than process; nevertheless, that material would have been valuable for resolving editorial queries Nicolas Hodges and I had when preparing Collana for publication after Connolly’s death. Keeping no record of that material suggests that I assumed its primary value was for him rather than me.

Thirty years later I can’t remember any detail from our workshops, only a feeling that we worked hard and had fun. Connolly was intensely serious and focused, yet also curiously playful and challenging. This could have been a disconcerting combination of attributes but I enjoyed every aspect of working with him; nevertheless, I always felt I needed to be on my ‘A’ game. Indeed, collaboration with composers is often explicitly challenging in ways analogous to play in sport, but this dynamic dimension of collaboration is largely absent from CPC scholarship, possibly because of demand characteristics.

Yet although the literal workshop data for our collaboration is lost, we have something more valuable. After he had ‘assembled’ the piece on large A3 sheets, Connolly went to Scotland, examining for the Associated Board, so we weren’t able to work together again before the premiere.Footnote 6 Instead, he wrote a nearly 5000-word letter, the main body of which works through the piece in detail – line by line, as one might in rehearsal – offering elucidatory comments, pragmatic questions and suggestions. That commentary is framed by an overview of the structure and more general comments about choreography (at the instrument) and notions of theatre. A 5000-word letter on a 10-minute piece might suggest a certain kind of control freakery, but the writing itself sends a very different message.

Before exploring the letter’s content, some context for Connolly’s work and our relationship is necessary. I always sensed that he was an idealist, with unshakeable faith in music’s power to communicate, but he was also a pragmatist, intimately engaged with the physical dimensions of music-making. These different characteristics run through the letter and transcend its specific focus on the piece and our relationship.

Prior to the ‘Unforgetting Justin Connolly’ event at the Royal Academy of Music on 23 February 2024, Michael Finnissy wrote to me of Connolly’s idealistic belief in the power of musical material:

I [will] concentrate on how ‘uncompromising’ (would you say that is the right word?) and significant his work was (to me), and still is, representing a breadth and a seriousness of (one might say ‘philosophical’?) engagement that is still too rare in Music – and EXTRAORDINARILY achieved with PITCHES and RHYTHMS … [A] work-out for the ears, brain and sensibilities. Quite right too – no cheap tricks, just plenty of intelligence and skill and no playing “to the gallery”.Footnote 7

Connolly’s pragmatism can be illustrated by his editorial interventions in Cinquepaces (1965), written for the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble.Footnote 8 Donna McDonald has written that the ensemble ‘hated’ the piece, ‘urged on the group’ by the percussionist Gary Kettel who wanted to get contemporary music into their repertoire instead of the ‘safe pieces which had been played hitherto’.Footnote 9 Philip Jones himself described the piece as ‘like a mountain we couldn’t climb’.Footnote 10

When Connolly heard the premiere at the Cheltenham Festival, he was not much happier than the ensemble. He did not like what he had written. The BBC had recorded the premiere and the first broadcast went out sounding like the performance. The repeat broadcast should have been the same: it was not. Connolly turned to his friend, the composer and music producer, Martin Dalby, and the two of them slipped into a studio. With an editor’s razor blade, Martin deftly removed the offending passages and Cinquepaces, Mark II, was born. […]

Connolly took the score away and rewrote it, maintaining the excisions which had been made in the studio and rephrasing other sections. When the quintet saw Cinquepace, Mark III, they found it much easier. For once, it was not a case of a score seeming less difficult because its problems had been conquered: it actually was less difficult!Footnote 11

Connolly’s preoccupation with the physical dimension of music-making is captured in an interview from the early 1970s with Keith Potter and Chris Villars. Asked about the twentieth-century music that influenced him, Connolly focused on the performance dimension:

Elliott Carter has been particularly influential. I’ve always been absolutely fascinated by his idea of the connection between performance by the players and the kind of thing that is invented to play. For example, consider Webern’s music. Nobody could claim that it is really the music of performance. It doesn’t react upon the player in that kind of way. Carter’s music, although it’s very complex, has a great sense of the drama of actually playing instruments. This is a very important thing to me ….

I think this is a prime thing, this involvement with the notion of performance. I’m fairly active as a conductor and am very fascinated by the particular difficulty players have in coming to terms with what I’ve written. Also, I’m sure what I’ve written is itself suggested by what I imagine takes place when somebody does something on an instrument. Ever since I first started writing music, I’ve been very keenly concerned with what it was like to play.Footnote 12

When we worked together in 1995, Connolly was in his early sixties and I was in my late twenties; we were colleagues but a generation apart. I was working on a doctorate on Debussy’s three sonatas, with a focus on the notion of rhetoric, and had made a catalogue of the detailed verbal material Debussy used in his music from 1912 until his death in 1918. Connolly and I talked about this often. I too was fascinated by Carter’s music in performance; his 1948 cello and piano sonata was a repertoire staple for me and the Arditti Quartet’s performances of Carter’s quartets (the first two in particular) formed an important core of my understanding of what it is to be a musician. Interest in the physicality of performance and the ways in which language can shape musical understanding were thus shared ‘drivers’ in my work with Connolly. So although the letter is written from his perspective, its context is shared. It is clear that he is empathising with and acting out my performance perspective on the challenges the piece presents, as well as helping me understand his compositional perspective. Michael Boyle describes this as ‘empathetic embodiment’ and suggests that its ‘cognitive load’ is distributed through many different dimensions of collaborative activity.Footnote 13 The letter is a striking example of Connolly’s awareness of how that distribution can operate.

Here I have selected elements of the letter that I feel will help readers – not only those working specifically in CPC but also other performers of his music – understand Connolly’s musical vision. As in a workshop, the detailed explication of both ideas and gestures/drama in this document reveals Connolly’s musical approach in ways that are impossible in a musical score or its realisation, but Connolly’s letter has the advantage over a live workshop of additional time for organisation and consideration, and greater freedom of perspective. In preparing performance notes for the 2023 publication of Collana, I removed the Heyde–Connolly-specific aspects of the letter’s observations and retained only its most generalisable elements of performance advice and gestural language; tension between score language (quasi-universal) and workshop language (local, possibly for an audience of one) is a rich area for CPC research.Footnote 14

Aspects of the Letter In Detail

The letter starts broadly and gradually focuses, from general observations about the music’s flow and structure to discussion of presence, projection, rhetoric and the player. Connolly closes his introductory section with a detailed explanation of his understanding of the status of the notation, important because I had only then encountered a finished version of the piece. Connolly’s text is presented in his complete paragraphs (indented), with my comments interpolated.

… As you know already, the piece actually looks a lot healthier on large pages than it did on ditsy little pieces of paper: I think you will recognise a flow which is provided in the first instance by the dynamic tension between the ‘passive’, ‘colouristic’ A–H and the ‘active’, ‘colourful’, I–VII so that energy accumulated during a passive phase gets discharged in an active one.Footnote 15

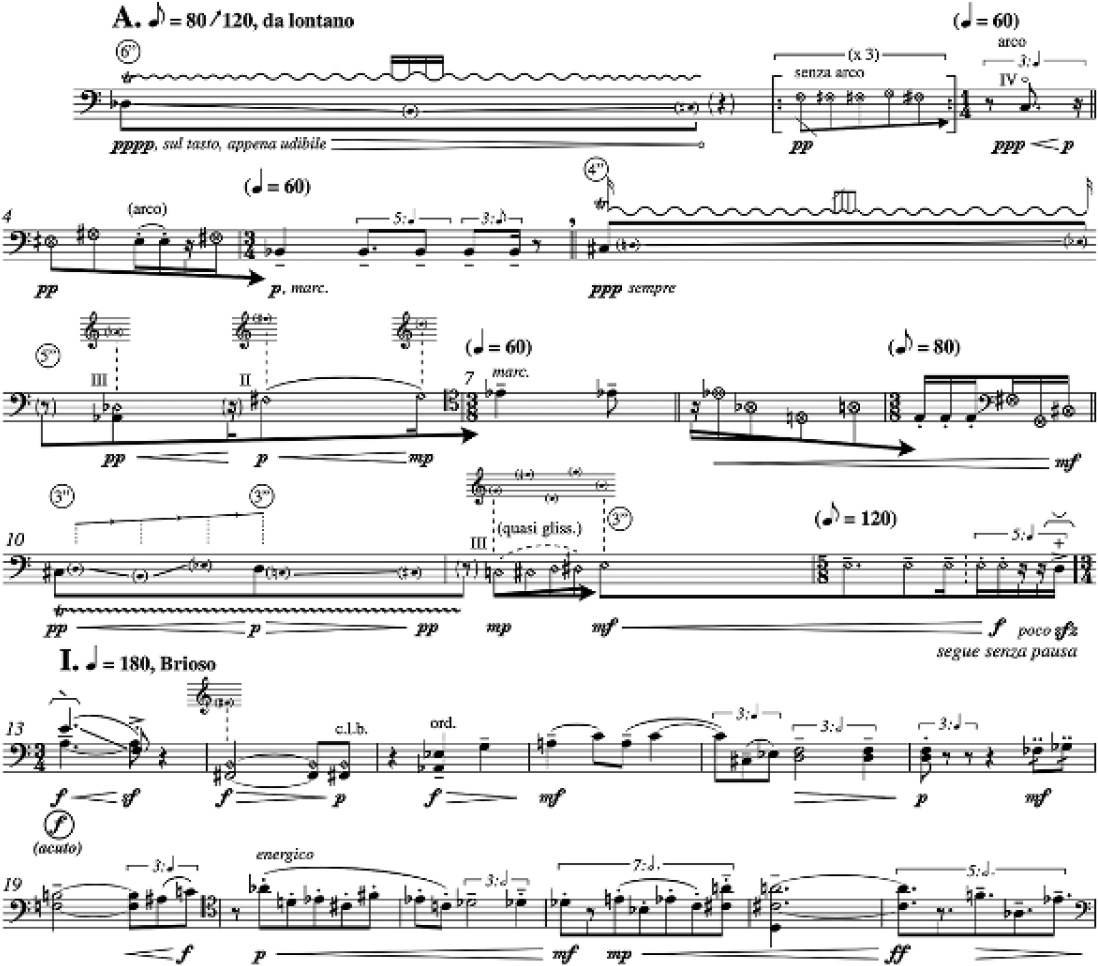

The notion of energy ‘accumulation’ and ‘discharge’ proved very useful when recording Collana in July 2024: I found it expressively helpful not to resist the inherent physical tension in ‘holding’ the material in the A–H sections. Unreleased physical tension is something that performers want to avoid wherever possible, but expressive tension is useful. Knowing that the tension will be discharged/released in the rhythmic and colourful I–VII sections (see Example 1) is reassuring, and I resolved to use the rhythmic frameworks of those sections as ‘ground’ on which to release tension.Footnote 16

The A–H sections are thus more difficult for the player to project: a kind of motionless movement is required which, given the natural presence of an instrument like the cello, is essential dramatic as much as musical. Accordingly, A–H have a rhetoric of their own: a very quiet rhetoric, to be sure, but one of inwardness and concentration.

To that extent the response of the player is crucial: these are in a sense rather more than single classes of sounds in juxtaposition, and the task is to sense (1) an underlying connectedness (2) a projection of the sounds as sounds, (to this extent at least there is a perhaps surprisingly Cagean aspect to such gestures), and this is where the theatrical aspect of holding the audience to some expectation, of drawing them on, is involved.

Having seen you play, I know that you do this naturally, as part of what you are as a player, so I at least am not worried as to how or whether you can establish that connection with the audience. The problem, such as it is, looks very different from your perspective, since you will necessarily be unsure as to how automatic that link-up will be, given the starkness of the material.Footnote 17

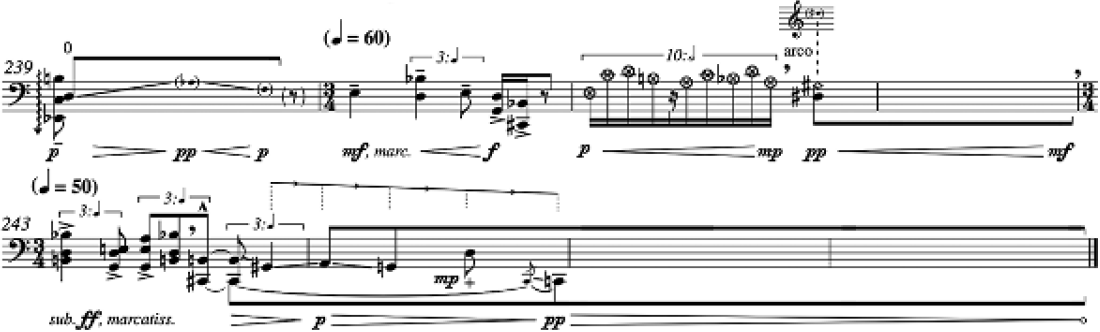

Example 1: Justin Connolly, Collana (1995), bars 1–24.

‘Projection’ and ‘presence’ are important words for me in conceptualising performance. The notion of an inward, concentrated, rhetoric may have come from our conversations about Debussy, but Connolly’s connection between the notion of projection and Collana’s ‘passive/colouristic’ material proved challenging and fruitful. He explicitly empathises with the challenge of this unusual kind of projection, taking it as read that the audience will see the physical action of realising the music (although presence and projection are equally, if differently, relevant for recording).

Needless to say, a score cannot include all the layers of instruction and counter-instructions which must be involved in a realisation: the very first note is an example of how, because one must say something one sometimes has to say nothing. I don’t, for example, tell you how to start the note, except negatively. What is meant, of course, is something simple and obvious, like your pretending to be busy playing it well before anyone can hear anything. This immediately puts the onus on the audience to pay attention. I suggest quite a noticeable (but silent) LH finger movement in the trill for some seconds before the bow is really engaged – ‘air-playing’ – and that when it is, there is some doubt on their part as to what they are hearing. The small pitch change can be a little exaggerated if you feel it that way, a descent below B is perfectly possible, and probably a hint of cresc./dim. when the semiquaver speed is reached, but only a hint. This is the kind of interpretation I meant when I said my instructions were negative; you have to take steps which may seem quite contradictory in order to project the imagined reality. I could have written a small cresc./dim. myself, but you would only have executed it, a very different kind of action to this tension between my instruction and your, as it were, counter-instruction.

I mention this not because you would not think of it for yourself but to legitimise your freedom to take certain steps. The score is the recipe, for which the performance is the cake, so there are a lot of things you do for which the recipe, quite rightly, provides little or no direct authority.

All these notes of mine are intended as suggestions or, indeed, analogies which may prompt you not to obey them but to create realities of your own, a parallel universe of discourse, so to speak …Footnote 18

Connolly wants to ensure that I don’t feel limited by the notation. He is authorising a certain kind of freedom (‘legitimising’, as he puts it), but the examples he offers make it clear that freedom is bounded. More importantly, however, I read this as a sporting challenge: if you only do what is written you will have failed.

What follows are some remarks about the gestures, modes of playing, modes of interpretation as seen by me. They are not prescriptive so much as mildly elucidatory, I hope …Footnote 19

The closing paragraph of his introduction picks up the notion of ‘elucidation’, which I think we had discussed in the context of Debussy’s use of language in his late music. There, as here, some words that could be read as ‘instructions’ are more powerfully understood as explications, affording space for the performer to conjure a parallel universe. The line-by-line discussion that follows offers an enormous range of language and suggestions that open possibilities for me to invent this parallel space.

The almost one-to-one mapping of letter to piece prohibits complete discussion of its detail. Instead I have selected a few passages under headings designed to connect the observations to the wider CPC literature, including Connolly’s full text to give a sense of the multiple dimensions in play and the ways in which his ideas are woven together.

Notation

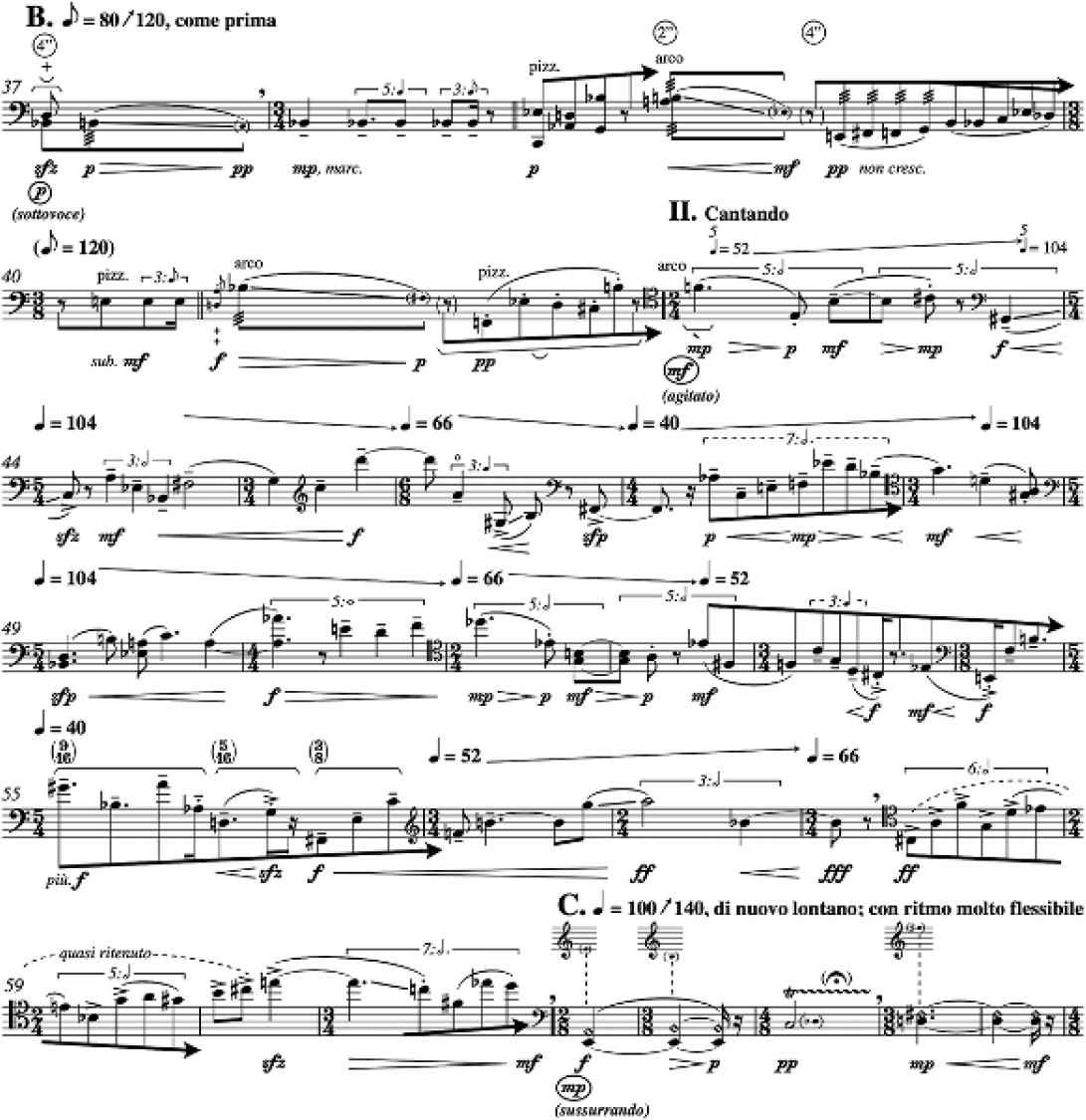

[Bars 37–40] The use of a circled dynamic governing a section … helps define a degree of projection: thus [circled] ff is ‘extrovert’, [circled] pp ‘inward’, and so on. I have also indicated by means of an underlined word, in this case sotto voce[,] a climate for the section B. Of course it also refines the notion of what is to be the mf of the situation, but this is not intended to be too literal. The tremolo quite long: 4 slow seconds. The B-flat, somewhat dry, a quasi tamburo sort of sound. Is it possible to make the accent by a flick or drop on the string (or with finger percussion) followed by a non-vibrato continuation? But some slightly ‘unmusical’ sound interruptive as before. The pizzicato non-arpeggiated, in pairs and rhythmic unison. The gliss. is more important than the open string which must never obtrude over it (same for all similar contexts elsewhere in the piece). Try slowing the tremolo down to meet the semiquavers; but only do it if it is easy: the semiquavers speed up, of course, as do the trem. notes.

[Bars 40–41] The pizzicato measured, dry. A natural gap then the (now altered) tremolo. If you want to get the tremolo on to the D (as opposed to the G) the A could still be open, the D being on the G string. Is a LH pizz. possible on stopped notes? – I suppose it depends on the context leaving fingers free to carry it out – otherwise you could just do the trem. on the G. I intend all these to sound simultaneously: my notation doesn’t convey that properly; following pizzicato leisurely, as if looking for somewhere to go, but not worried where.

[Cantando II] The very first bar shows us where: it may need to be slightly louder than mp. The upbeat slur before the 5/4 interrupts, or punctuates the song, as does the later one in the 6/8 bar. [46] The septuplets and after (up to [bar 49]) are a ‘middle section’, but one which contains the material of later unfoldings. After the fff a formal coda which is a yet further development and continuation of the faster moving material. The ‘quasi-ritenuto’ means that ![]() ${\require{mathtools}\overbracket{6}} \rightarrow{\require{mathtools}\overbracket{5}}\rightarrow{\require{mathtools}\overbracket{4}}$ are to be smoothly integrated into each other.Footnote 20

${\require{mathtools}\overbracket{6}} \rightarrow{\require{mathtools}\overbracket{5}}\rightarrow{\require{mathtools}\overbracket{4}}$ are to be smoothly integrated into each other.Footnote 20

There is a lot here, but perhaps most important is the connection between dynamics and projection. The prefatory note in the score is less explicit about this: ‘the style of playing assumes, in terms of amplitude, a basic dynamic, within which specific and local indications are to operate.’Footnote 21 Despite the detail of the notation, he expects the performer to inflect the dynamics in relation to notions of arrival and interruption, and to modify the rhythmic values in relation to larger shapes (smoothing the 6:5:4 tuplets, for example). The pragmatic discussion of the tremolo/pizz. in bar 41 (see Example 2) is typical of Connolly’s openness to a range of alternative technical ‘solutions’. He is aware that the notation doesn’t convey the conceptual simultaneous sounding of the two ‘events’ properly but is also juggling the physical difficulty of getting everything to happen together. In fact the pizz. has to be slightly early, and there are no simple solutions to the challenges.Footnote 22 His manuscript notation places the ♭ sign for the B before the grace-note pizz., which pulls the events closer together on the page but is not good notation practice. (The ♭ sign should be before the note it alters, as it is in the printed score.)

Example 2: Justin Connolly, Collana, bars 37–66.

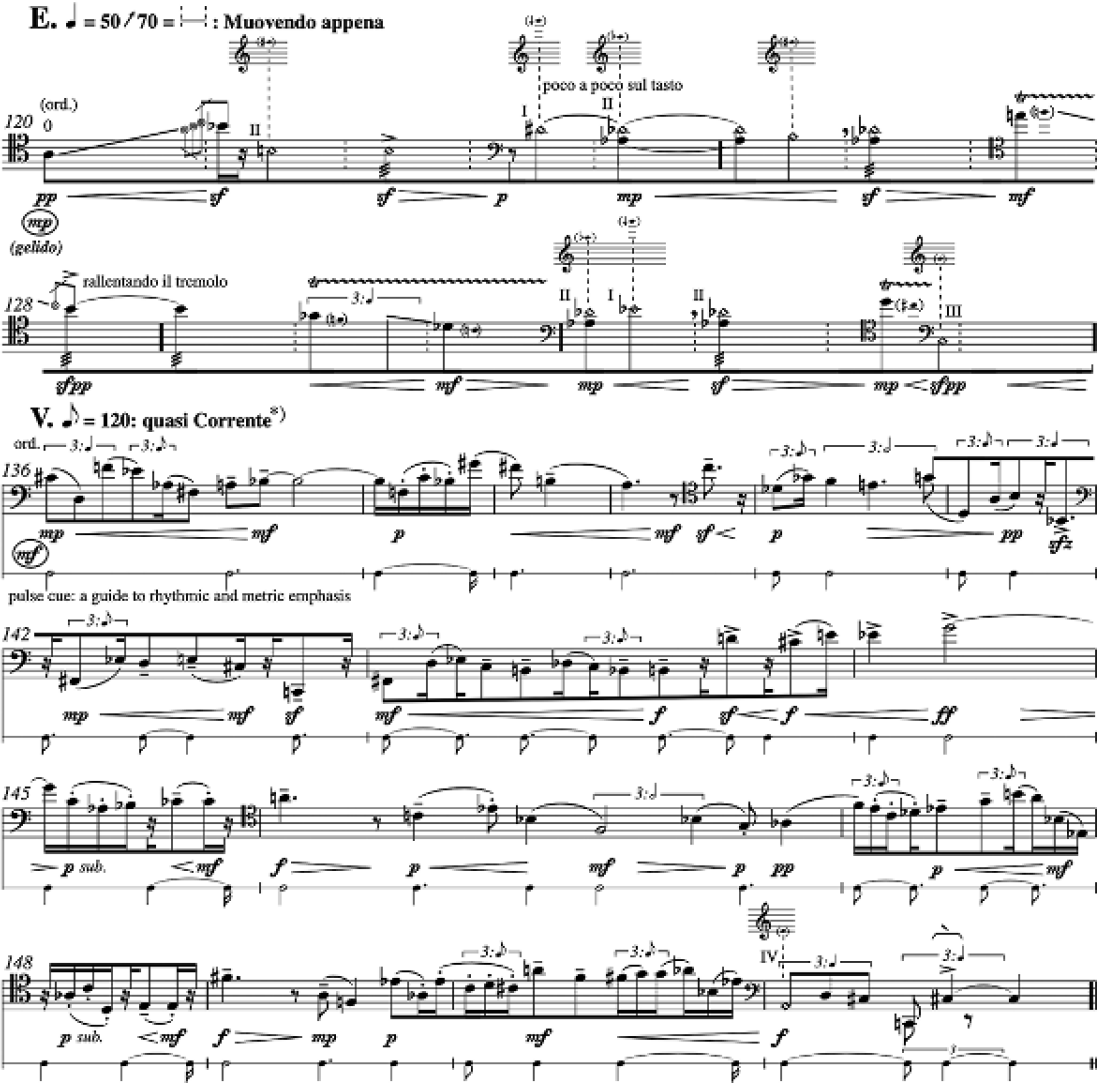

[E] An eerie whistle: one might even try starting on the 2 octave harmonic as a grace-note to the gliss. upwards. (Just a thought.) The percussive notes as we have agreed. The motionless quality of the whole section should suggest an icy world of sounds which change focus in obedience to a mysterious order, but yet form a line as far as possible. The idea is that the pulse between dotted lines is to be variable (50–70), but on top of that the events must appear as they are shown – early, middle late – in a mysterious sequence which sounds ordered however arbitrary it looks on paper. Expressed in ‘real’ rhythm it would have looked wrong. You have to find your own rightness for timing it. Exaggerate by all means: you have a free hand under the terms of the notation after all.

[quasi Corrente V] the opening notes of the corrente follow pretty straight upon the end of E; the first 3 are at the tempo of I (crotchet 180) But here too the notation, now somewhat ‘exact’ is only a guide. I believe the large copy shows the form better. It shows how for example … [bars 137–139, 145–146 and 148–149] are connected, and the rhyme between [bars 147 and 150]. The idea is akin to the way a sculpture can be viewed from different angles, yielding a new perspective in each. The decorative 2:1 groupings [quaver:semiquaver] must swing but not jerk, they are notes inégales, all right, but not so stylised. They can be different lengths even.Footnote 23

The balancing of the sense of a line with the ‘motionless’ quality (ordered but mysterious) is expressed more clearly in the letter than in the notation. The idea of sculptural perspective in the ‘rhyming/connected’ bars of V has proved invaluable as a tool for rehearsal and practice strategies in many other places, encouraging working paradigmatically to enhance awareness of the connections. Getting V to feel ‘natural’ and swinging rather than jerky or restricted (or too ‘stylised’) took me a lot of practice. His pulse cue proved very helpful, an idea that probably came from his conducting experience (see Example 3).

Example 3: Justin Connolly, Collana, bars 120–151.

[Bars 165–167] This marks the emergence of the robotic, drumlike sound as a genuine musical gesture in its own right; one which becomes increasingly important in G and H, and which is, in fact, never quite the same twice, except that before F it had no ‘harmony’, and now will explore that possibility. The pizzicato, like the earlier one, not arpeggiated but clipped and quite rhythmic – it is a bar of 7/8, rather faster than the 3/4 – and again the music dies out in mouse-like scratchings. Take really good time over this: (I think I have made it too short!) In any place where there is a question of going on longer: GO ON LONGER. Obviously, getting everything with only one turn over means some compression and this sometimes spoils the spatial picture. The end of F [bar 167] must be at least equal to a couple of bars of the Volante section which follows. You will have noticed the deliberately different styles of linkage between sections. Here is a new variant, the use of similar processes, tremolo, in quite different musical contexts.Footnote 24

Structural questions seem most important to Connolly here, specifically the evolving gestural character of the ‘robotic’ material of bar 165 (which leads to the conclusion) and the ways in which sections are interlinked (see Example 4). However, the observation that the spatial dimension of the notation may be compromised by the pragmatic need for a single turn is also important, and I think I may have needed to work harder to realise this in performance: the spatial distribution on the page is highly suggestive and hard to ignore. I have, however, kept his exhortation to ‘go on longer’ at the front of my mind often in the decades since this letter. I generally dislike performances that linger unnecessarily, but identifying where music has to breathe or to ‘listen to itself’ is critical. I’m not sure Connolly’s observation is in quite the right place in relation to this piece; the capitalisation and emphasis (a double line in the margin) suggest it is a more general aside.

Example 4: Justin Connolly, Collana, bars 163–170.

Tempo

[Bars 1–3 (see Example 1)] The ‘seconds’ are as slow as the acoustic ambience suggests they might be. Plenty of time for all gestures. LH senza arco figures might start quicker, slow down, speed up: as you like; they are as fast ‘as possible’ meaning only that they are not slow, but what is effective to produce a kind of muttering similar to the opening gesture but complementary to it. The octave harmonic like a snatched exhalation of breath.Footnote 25

[Bars 13ff (see Example 1)] This notation of [poetic feet: unstressed–stressed] is the classic upbeat-downbeat, or arsis-thesis, effect … The timing of this upbeat has to be fairly exact: too long and it is ugly; too short and it won’t work. On reflection I think the notation of the D shows only its position relative to what precedes it. This is legitimate; the downbeat follows after a unit of the new tempo crotchet 180. However, this is only a suggestion: find a speed you like which holds the events of I in proper focus with one another. As you say the Brioso is jaunty: a scherzino, abrupt, athletic, swinging. The dynamics may be fussy but they are functional rather than aesthetic, they help to organise the progress of the events. The ‘energico’ [bar 20] is perhaps not dotted but a vigorous detaché. And you will see I have added a D to the C♯ /A chord, but if it creates a problem, omit it.Footnote 26

Given the sophistication of the rhythmic notation, it is not surprising that Connolly feels the need to explicate priorities in many places, but the specific observations are perhaps surprising. Even the indicated ‘seconds’ (which one would usually expect to be literal) are to be understood contextually, and ‘as fast as possible’ is also not to be measured physically, but by quality of perception. This also holds true for the metronome indications, which I expect are more usefully understood in relation to one another (as he also indicates for the timing of the ‘upbeat’ d). In fact, crotchet = 180 is basically viable for B, and Connolly’s additional character indications are very helpful. The challenge to keep the events in focus with one another is usefully suggestive rather than prescriptive. (Note however that the dynamics here perform a different function to those described above.)

Gesture

The stock of personal language and metaphors in this letter were valuable references for the performing and recording involved in the recent double album of Connolly’s music.Footnote 27 The brief passages extracted below give a sense of the ways in which he connects gestural language to narrative and large-scale structure.

[Bars 4–6 (see Example 1)] More deliberate: the arco interpolation quite stiff, mechanistic. The E and B♭ define a space within which, or around which, events occur. The 3/4 bar somewhat robotic, exact, not very ‘musical’: as it speeds up it offers an upbeat to a brief silence, which is followed by the trill, distant in sound but again not expressive of anything except a sonic property. It should be mechanistic in having no nuance: it stays ppp throughout.

[Bars 6–9 (see Example 1)] The three harmonics are expressive, they attempt a tune, but their very tentative effort is interrupted by the 3/8 bar. Closure is followed by a new version of line 2, the E♮ is now part of a complex gesture, rather more urgent.

[Bars 10–12 (see Example 1)] The trill starts to come alive as a consequence; wider range, a small nuance: the harmonics too show more resource than before, but are called to order by the harmonic B which is now part of the measured robotic speeding: this is an accelerating accelerando, being a quicker pulse than before, and quickening internally too.Footnote 28

Connolly is at pains to show how the ‘robotic’ or unmusical elements relate to the expressive ones, and also how the robotic ‘speeding’ might generate structural momentum. By the end of the letter and the piece it has become clear that the expressive evolution of the ‘robotic’ material is in fact Collana’s central thread. Setting this up carefully at the outset is good rehearsal strategy. Tracing that evolution in full would be laborious, but the final version is presented in Example 7; the next extract from the letter refers to the penultimate section that sets it up (see Example 5):

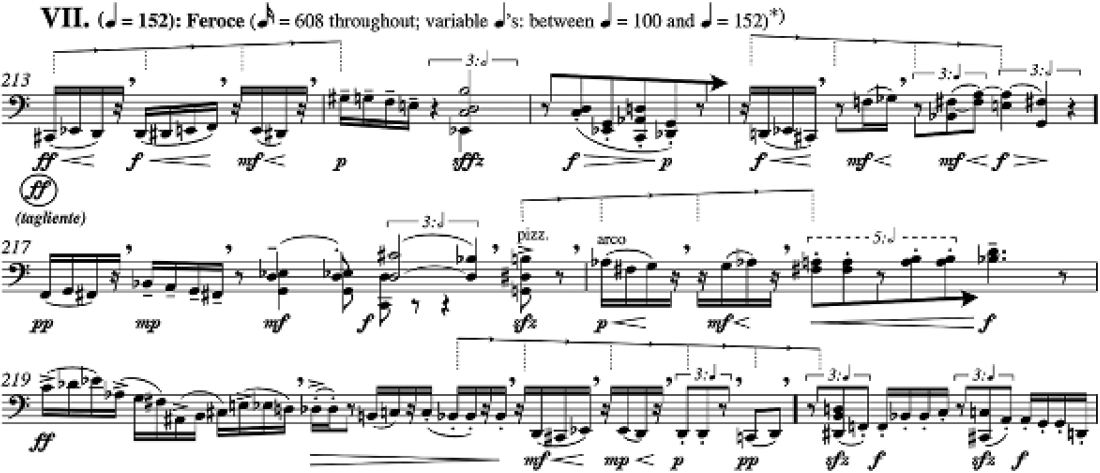

[VII] The qualifying instruction I wrote may not be quite readable: it is TAGLIENTE, meaning ‘cutting’, in the sense of digging-in. The whole of VII is somewhat drastic, even slightly brutal. In a way, this reflects the tension created by the previous music which has never been able to find a resolution. We have now tried almost everything, so there is something of a struggle going on towards the point where we might do so. Hence the chords are a bit like climbing to a rock before being swept away again. The third bar could be col legno, if you liked. The dynamic range everywhere very exaggerated, from a whisper to a roar.Footnote 29

Example 5: Justin Connolly, Collana, bars 213–220.

The density of gestural language here is striking and matches the tension created by the fast tempo as it and surges and retreats, which is further cut into by the commas. Whereas Connolly indicates early in his letter that tension is accumulated in the A–H sections and discharged in I–VII, that no longer seems to be the case. The image of climbing to a rock before being swept away again is explicitly and conventionally dramatic. The intensity is climactic, but the rhetoric is not.

Choreography (at the instrument)

Whereas there is little need to provide choreographic instructions to support the intensity of VII, Connolly often devotes considerable attention to the less active parts of the piece (see Example 6). These are more challenging to choreograph as there is more freedom (fewer notes, less rhythmic drive) and, as Connolly notes below in his playful description of ‘dull’ places, perhaps more potential to fail dramatically.

[Calmo IV] …[D] … can be felt as a long upbeat to IV, which is the still centre of the whole piece. Not too many actions; a regal calm, perhaps rather like (or not!) the second music of the Fauré Élegie, which it hardly seems to resemble physically, but has some spiritual kinship with. Floating in fact: firm but non agitato, even in ff. Actually a moment of the spirit.

[Bars 110–113] The descending triad very cool and measured; the whole line gently subsiding at the last minute.

[Bars 114–119] Again a rhythm compression, subsidence, and the final bars: rather stern, rigorous, unsentimental. Everything stops, and you must pray that they don’t start clapping. Turn over very slowly; it doesn’t matter about the gap too much – anything is better than a furtive grab at the music – and if you can suggest continuity in the way you stage manage it, so much the better.Footnote 30

Example 6: Justin Connolly, Collana, bars 105–119.

The reference to Faure’s Élegie doesn’t feel quite right to me, as I think he anticipated, but it does suggest the kind of stillness I imagine he wanted. ‘Firm but floating’ is a typical Connolly balancing act and the idea of Fauré’s music centres it, which is after all the expressive goal suggested by the ‘still centre’ (a nod to Eliot’s Burnt Norton). We discussed the page turn a lot. Although I think he’s being playful here about ‘praying’ the audience doesn’t clap, the page turn feels to me to have an important dramatic function in the piece. After the stillness of IV the piece enters a new phase of exploration with the glissando that opens Example 3, which seems to mirror the page turn in some way (no matter how slowly it is done),Footnote 31 and I now wish I had included the noise of the turn in the recording.

[A–H in general]Footnote 32 I hesitate to mention this, but it may help with such ‘dull’ places to imagine yourself playing an instrument you don’t know, which may or may not contain a repertoire of possible sounds which you successively and patiently extract by trial and error, so to speak. This whole domain of a kind of Beckett-like emptiness which one populates with speculations, attempts at discourse, failures too, is highly interesting as part of the psychology of performance. My score (in A–H) is definitely a scenario of buildups, come-ons, retreats, interruptions, overlaps, all of which in their twitchy, unsatisfactory way should lead the ear to demand ‘a tune’, such tunes being in I–VII, with F somewhere at the intersection between the styles.Footnote 33

Although he precedes this playful, beautiful and challenging proposition with an expression of hesitation, it is emphasised by a double vertical line in the margin. There is enormous dramatic performative power in ‘not knowing’ (or at least not giving away that one knows), which is all too rarely present in carefully rehearsed performances.

Conclusion

Connolly’s letter ends:

The final gesture as compelling as you can make it: it is the resolution of everything – ‘the stone which the builders forgot is become the head of the corner’Footnote 34 – and the final cadence shows us the perspective in which it has its being [see Example 7]. Hold on good and long, of course …

This stuff may be absolutely useless as a help, and it’s perfectly possible that one’s reluctance to explain the unexplainable really means that everything I say should be distrusted, if not actually disbelieved! Having said that, I am not of course the person who has to decide whether or not it is useful: I’m merely expressing my own feeling, with a certain embarrassment at so often stating the obvious. But to a player of a new piece, however willing and au fait with the aesthetic position it represents, such an idea of the obvious may in itself be quite different.

The chief difficulty of the music is the rapid creation and dissolution of differing kinds of tension: it is only one thing, but seen like a statue, from 15 different viewpoints. And of course it isn’t variation which is involved (I–VII [the beads] are too different to be variations, A–H [the string] too much the same).

For me, the drama of the piece is that the search for these realisations leads deliberately in a certain direction – through I–VII [–] while the resolution stealthily creeps up from a totally unimportant-seeming detail [the ‘robotic’ repeated notes], not even expressively shaped: in fact, deliberately so, and which gradually acquires significance till in the final line it blocks out all the previous attempts at resolution. Homespun philosophy, perhaps, to discover that the string is more important than the beads! But of course, the piece is not ‘about’ that, so much as the drama implicit in the tension generated by opposites: as here, opposites of sound production, argument, relatedness, articulation and bowing. In the end, it is about itself, as we both know.

I’m looking forward immensely to hearing it, and thank you in advance for being so willing to participate: that willingness, even though it be found in so few, is one of the chief reasons for writing music at all.Footnote 35

Example 7: Justin Connolly, Collana, pp. 239–246.

The premiere went smoothly and Connolly seemed happy, but in a performance the following year at the Conway Hall I felt I really caught the essence of what we had been trying to achieve. Immediately afterwards, Connolly said something that resonated powerfully with my sense of what I am trying to achieve as a performer. Written down, it may seem bathetic, so I assume the big smile with which it was said probably helped its impact: ‘I just sat there thinking, did I really write this wonderful music?’ My delight had nothing to do with ‘ownership’ (often discussed in CPC literature)Footnote 36 but was simple pleasure in knowing that I had returned the piece to him (in the sporting sense) having risen to its challenges with sufficient invention and freshness.

I hope that opening this time capsule reveals something about the nature and potential of the field. Because the letter prefigures more recent writing, we know the issues are real, rather than invented for the CPC research context; I hope it will be seen that there is also a different kind of rigour to his imagination of our missing workshop. That’s as much a question of audience as anything else, and surely CPC should be directed primarily at those who make music. I’ve attempted to capture the essence of the letter in the performance notes for Collana’s recent publication, but I think it can be argued that the close mapping of the letter and the piece means that they deserve to be appreciated in tandem. What would we give for more data of this detail and insight from major figures of the past, and how best can we share real work for our future colleagues?